Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Shake Flask Cultivation

2.2. Dry Weight Determination

2.3. Bioreactor Cultivation

2.4. Three-Step Fermentation

2.5. Ammonia, Trehalose, Glycerol, Acetic Acid Determination

2.6. Amino Acid Analysis

2.7. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution and Screening

2.8. Total Peptide Determination

2.9. Specific Growth Rate, Ammonia Yield, and Nitrogen Consumption Ratio

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

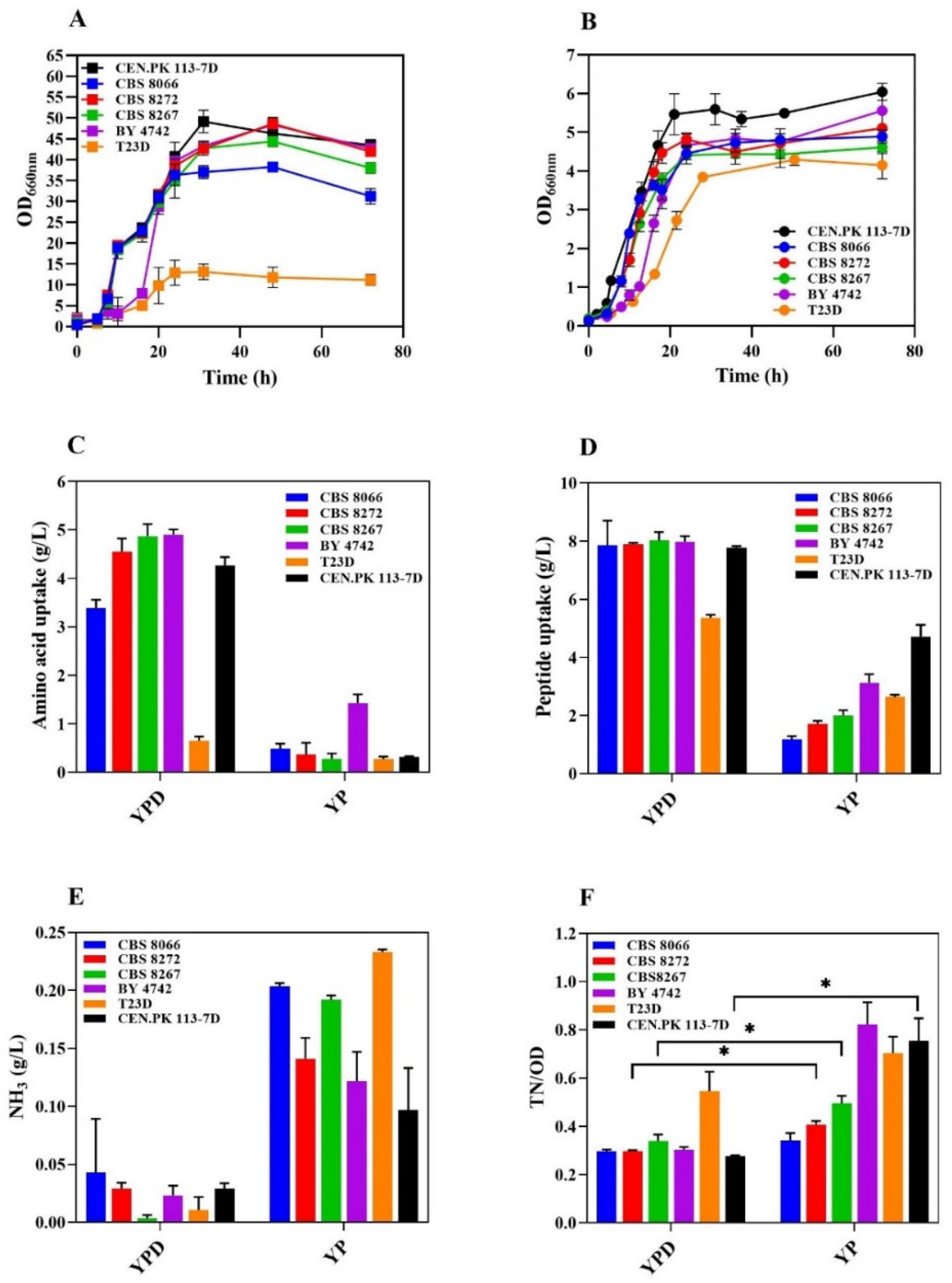

3.1. Growth on Carbon/Nitrogen Unbalanced Sources Enhances Ammonia Release in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

3.2. Increased Amino Acid Catabolism Correlates with High Ammonia Secretion

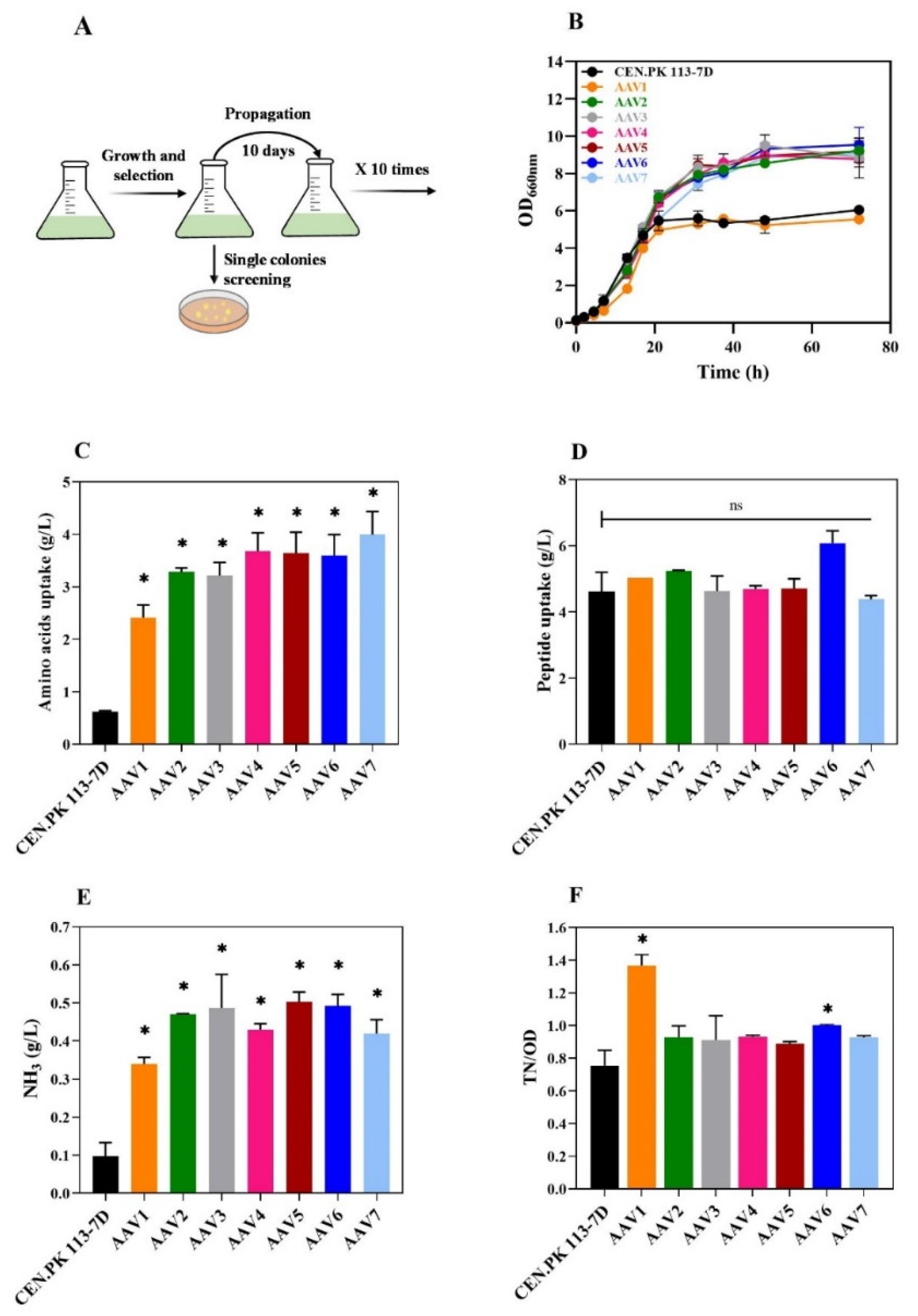

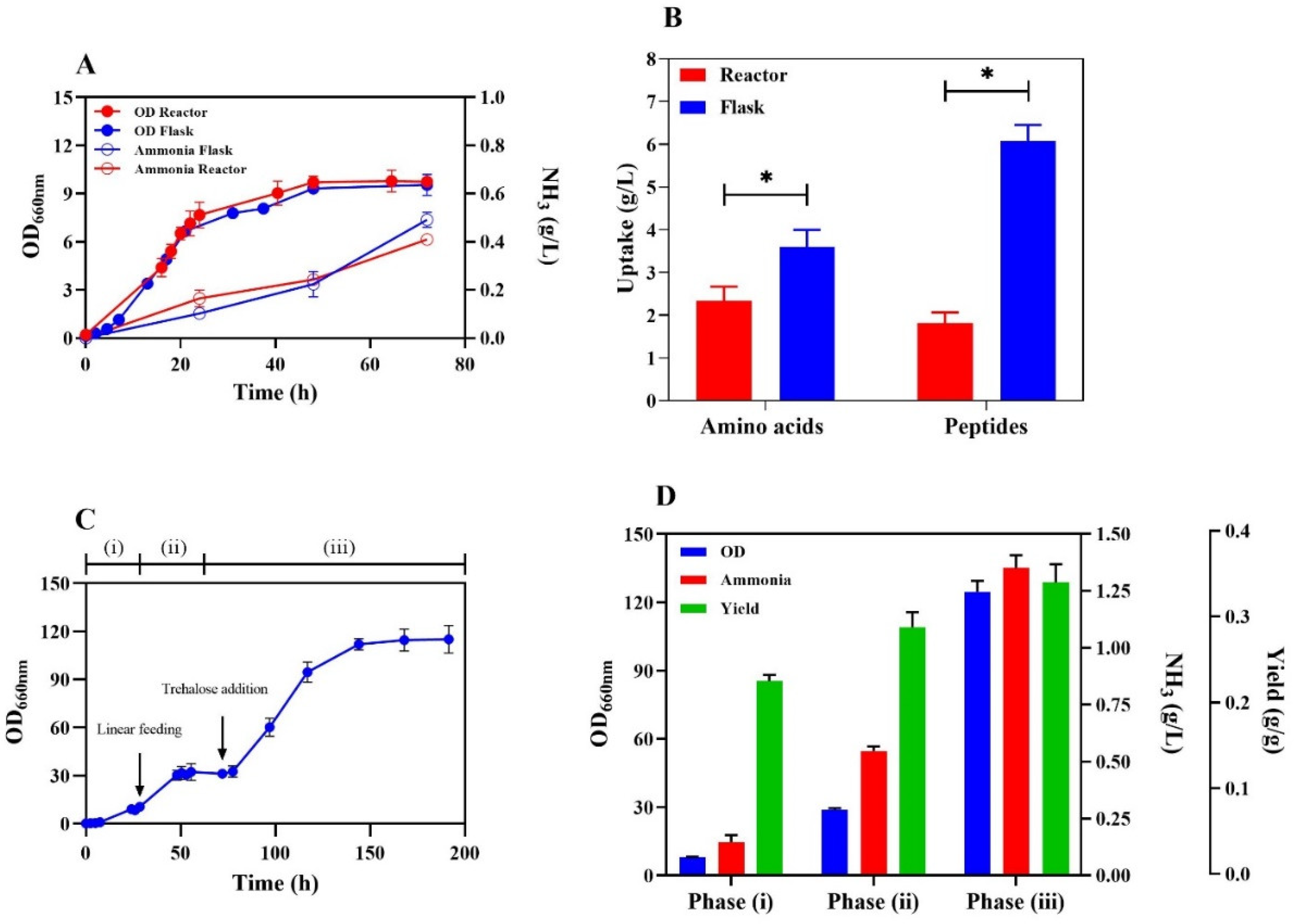

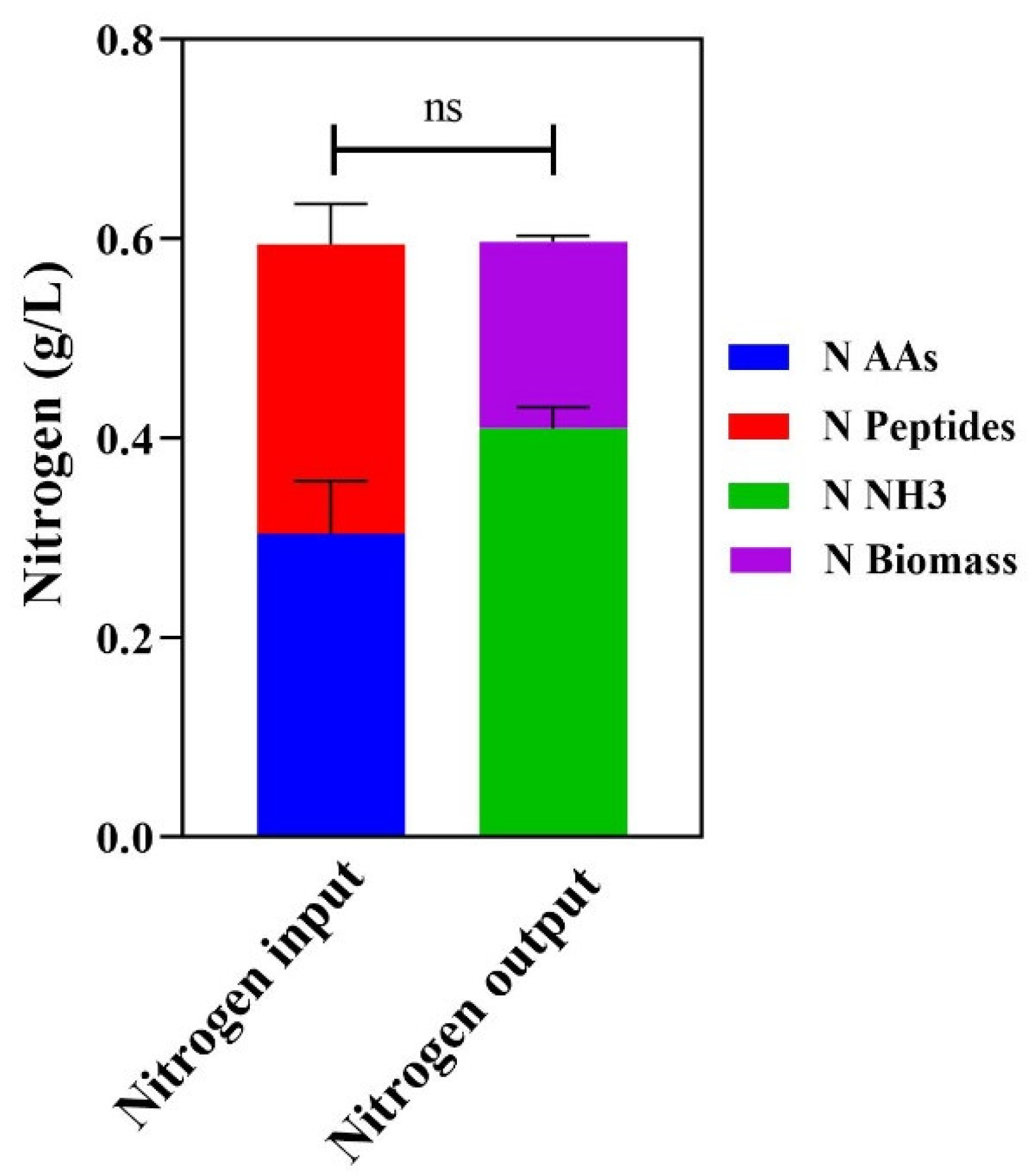

3.3. Improved Amino Acid Uptake Yields Significant Ammonia Production

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghavam, S.; Vahdati, M.; Wilson, I.A.G.; Styring, P. Sustainable Ammonia Production Processes. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amhamed, A.I.; Shuibul Qarnain, S.; Hewlett, S.; Sodiq, A.; Abdellatif, Y.; Isaifan, R.J.; Alrebei, O.F. Ammonia Production Plants—A Review. Fuels 2022, 3, 408–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.S.; Silva, V.; Rocha, R.C.; Hall, M.J.; Costa, M.; Eusébio, D. Ammonia as an Energy Vector: Current and Future Prospects for Low-Carbon Fuel Applications in Internal Combustion Engines. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Sustainable Biological Ammonia Production towards a Carbon-Free Society. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Perathoner, S.; Ampelli, C.; Centi, G. Electrochemical Dinitrogen Activation: To Find a Sustainable Way to Produce Ammonia. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2019, 178, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, V.; Garagounis, I.; Vourros, A.; Vasileiou, E.; Stoukides, M. An Electrochemical Haber-Bosch Process. Joule 2020, 4, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Elgowainy, A.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Energy Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Ammonia Production from Renewable Resources and Industrial By-Products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5751–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mus, F.; Khokhani, D.; MacIntyre, A.M.; Rugoli, E.; Dixon, R.; Ané, J.M.; Peters, J.W. Genetic Determinants of Ammonium Excretion in nifL Mutants of Azotobacter Vinelandii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.X.; Cho, K.M.; Rivera, J.G.L.; Monte, E.; Shen, C.R.; Yan, Y.; Liao, J.C. Conversion of Proteins into Biofuels by Engineering Nitrogen Flux. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Wernick, D.G.; Tat, C.A.; Liao, J.C. Consolidated Conversion of Protein Waste into Biofuels and Ammonia Using Bacillus Subtilis. Metab. Eng. 2014, 23, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatemichi, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Nakahara, T.; Ueda, M. Efficient Ammonia Production from Food By-Products by Engineered Escherichia Coli. AMB Express 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Ammonia Production Using Bacteria and Yeast toward a Sustainable Society. Bioeng. 2023 Vol 10 Page 82 2023, 10, 82–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Tatemichi, Y.; Nakahara, T.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Construction of Engineered Yeast Producing Ammonia from Glutamine and Soybean Residues (Okara). AMB Express 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Bello, I.; Mukaila, T.; Sarker, N.C.; Hammed, A. Trends in Biological Ammonia Production. BioTech 2023, 12, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijken, J.P.V.; Bauer, J.; Brambilla, L.; Duboc, P.; Francois, J.M.; Gancedo, C.; Giuseppin, M.L.F.; Heijnen, J.J.; Hoare, M.; Lange, H.C.; et al. An Interlaboratory Comparison of Physiological and Genetic Properties of Four Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, T.J.; Van Den Berg, M.A.; Visser, W.; Van Den Berg, J.A.; Steensma, H.Y. Characterization of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Mutants Lacking the E1α Subunit of the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992, 209, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachmann, C.B.; Davies, A.; Cost, G.J.; Caputo, E.; Li, J.; Hieter, P.; Boeke, J.D. Designer Deletion Strains Derived from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae S288C: A Useful Set of Strains and Plasmids for PCR-Mediated Gene Disruption and Other Applications. Yeast 1998, 14, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Divitiis, M.; Ami, D.; Pessina, A.; Palmioli, A.; Sciandrone, B.; Airoldi, C.; Regonesi, M.E.; Brambilla, L.; Lotti, M.; Natalello, A.; et al. Cheese-Whey Permeate Improves the Fitness of Escherichia Coli Cells during Recombinant Protein Production. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, C.; Postma, E.; Scheffers, W.A.; Dijken, J.P.V. Physiology of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in Anaerobic Glucose-Limited Chemostat Cultures. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1990, 136, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.B. (David B. Factors for Converting Percentages of Nitrogen in Foods and Feeds into Percentages of Proteins. US Dep. Agric. Circ. Ser. 1931, 183, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, T.R.; Cotta, M.A. Isolation and Identification of Hyper-Ammonia Producing Bacteria from Swine Manure Storage Pits. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 48, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, Y.; Yoneda, H.; Tatsukami, Y.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Ammonia Production from Amino Acid-Based Biomass-like Sources by Engineered Escherichia Coli. AMB Express 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palková, Z.; Forstová, J. Yeast Colonies Synchronise Their Growth and Development. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113 (Pt 11), 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkova, Z.; Janderova, B.; Gabriel, J.; Zikanova, B.; Pospisek, M.; Forstova, J. Ammonia Mediates Communication between Yeast Colonies. Nature 1997, 390, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapragasam, M.; Wilfred, C.D.; Jaganathan, J.R.; Krishnan, S.; Ghani, W.A.W.A.W.K. Choline-Based Ionic Liquids as Media for the Growth of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Process. 2019 Vol 7 Page 471 2019, 7, 471–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, G.J.; §, L.D.R.; Ahmed, A. Carbon Catabolite Repression Regulates Amino Acid Permeases in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae via the TOR Signaling Pathway *. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 5546–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothersall, J.S.; Ahmed, A. Metabolic Fate of the Increased Yeast Amino Acid Uptake Subsequent to Catabolite Derepression. J. Amino Acids 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto-Rojas, H.F.; Seifar, R.M.; ten Pierick, A.; van Helmond, W.; Pieterse, M.M.; Heijnen, J.J.; Wahl, S.A. In Vivo Analysis of NH4+ Transport and Central Nitrogen Metabolism in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae during Aerobic Nitrogen-Limited Growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6831–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, S.J.; van ’t Klooster, J.S.; Bianchi, F.; Poolman, B. Growth Inhibition by Amino Acids in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishina, K. New Ammonia Demand: Ammonia Fuel as a Decarbonization Tool and a New Source of Reactive Nitrogen. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 21003–21003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.C.; Lu, W.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Botstein, D. Ammonium Toxicity and Potassium Limitation in Yeast. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Sousa, M.J.; Leão, C. Ammonium Is Toxic for Aging Yeast Cells, Inducing Death and Shortening of the Chronological Lifespan. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca-mesa, H.; Sendra, S.; Mas, A.; Beltran, G.; Torija, M.J. Nitrogen Preferences during Alcoholic Fermentation of Different Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts of Oenological Interest. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaitakis, A.; Kalef-Ezra, E.; Kotzamani, D.; Zaganas, I.; Spanaki, C. The Glutamate Dehydrogenase Pathway and Its Roles in Cell and Tissue Biology in Health and Disease. Biology 2017, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberghina, L.; Mavelli, G.; Drovandi, G.; Palumbo, P.; Pessina, S.; Tripodi, F.; Coccetti, P.; Vanoni, M. Cell Growth and Cell Cycle in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Basic Regulatory Design and Protein-Protein Interaction Network. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, C.L.; Gancedo, C. Construction and Characterization of a Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strain Able to Grow on Glucosamine as Sole Carbon and Nitrogen Source. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Campbell, K.; Pereira, R.; Björkeroth, J.; Qi, Q.; Vorontsov, E.; Sihlbom, C.; Nielsen, J. Nitrogen Limitation Reveals Large Reserves in Metabolic and Translational Capacities of Yeast. Nat. Commun. 2020 111 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CEN.PK 113-7D | MATa MAL2-8c SUC2 | [15] |

| CBS 8066 | MATa/α HO/ho | [15] |

| CBS 8272 | MATa/α, prototrophic | [15] |

| CBS 8267 | MATa/α, prototrophic | [15] |

| T23D | Meiotic progeny of CBS 8066 | [16] |

| BY4742 | MATα; his3Δ1; leu2Δ0; lys2Δ0; ura3Δ0 | [17] |

| AAV1-7 | CEN.PK 113-7D mutants selected by ALE | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).