1. Introduction

Despite the increase in the number of women involved in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) recorded in recent years, men continue to significantly outnumber women in these fields. This phenomenon, known as gender horizontal segregation, refers to the unequal distribution of men and women across different educational sectors and occupations: while men are largely over-represented in STEM fields, areas such as humanities, education, health and welfare, often corresponding to fewer career opportunities and economic prospects, are female dominated.

In 2021, women accounted for only 32.5% of all tertiary graduates in STEM fields in OECD countries (OECD, 2023). In some fields – such as physics, engineering, and computer science – the enrollment gap between the two groups is even larger, with female students being less than 25% in over two-thirds of the OECD countries (UNESCO, 2020). The number of women in STEM fields among academic professionals is equally small. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, in 2019, less than 30% of the world’s researchers were women, and this percentage further decreases at higher decision-making levels (UNESCO, 2019). The Artificial Intelligence (AI) and big data domain is unequivocally the fastest growing technological sector, with four times increase in the labour-market participation between 2016 and 2022. However, the percentage of the women AI workforce increased only 4 points in the same period (Global Gender Gap Report, 2023). The underrepresentation of women in such a strategically important area risks amplifying gender inequalities, sexism and discrimination, as AI and big data are rapidly growing not only in the labor market, but also in shaping relationships and communication between institutions and citizens. For this reason, the increase of women participating in AI development - as either researchers, programmers, or users - is one of the key objectives of the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 (Gender Equality Strategy 2020).

Over the last decades, horizontal gender segregation has attracted increasing attention at all levels. An extensive body of literature aims at understanding the mechanisms that contribute to the gender gap in STEM fields to reduce the discrepancy. Remarkable efforts have been devoted to gender in science education by developing intervention programs for engaging female students in these fields. These actions are especially targeted at primary and secondary students, considered the most critical educational stages for addressing the problem (McGuire et al., 2020).

Several papers provide overviews of relevant studies, along with categorizations of the different approaches and interventions developed, which may help orient practitioners within this landscape. For instance, Brotman and Moore (2008) reviewed studies published between 1995 and 2006 related to science education and classified them into four key themes: equity and access, curriculum and pedagogy, nature and culture of science, and identity. Studies within the first theme - equity and access - examine bias and inequities in the science classroom to improve girls access to STEM by providing them with equitable science opportunities (e.g. Jovanovic & Steinbach King, 1998), while those in the second theme - curriculum and pedagogy - analyze gender differences in learning styles in order to develop gender-inclusive science curricula (e.g. Haussler & Hoffman, 2002). Papers in the nature and culture of science theme aim at reconstructing the culture of science according to a feminist perspective, often adopting an intersectional approach (e.g. Kleinman, 1998). Finally, the theme of identity includes studies exploring the role of identity in students’ engagement with and learning in science, special attention being devoted to disciplinary and scientific identity (e.g. Hughes, 2001).

Similarly, Liben and Coyle (2014) classified interventions aimed at addressing the STEM gender gap exploiting mechanisms identified by gender development theories, namely essentialist, environmental, and constructivist. Accordingly, they proposed a taxonomy grounded in the main goals of the intervention, consisting of five types: remediate, revise, refocus, recategorize, and resist. The first three types of interventions focus on enhancing girls’ skills in STEM (remediate), revising STEM educational programs to better align with qualities traditionally associated with females (revise), and emphasizing feminine qualities that are compatible with STEM (refocus). These types fall, to some extent, within the first two themes proposed by Brotman and Moore (2008). The others better align with the nature and culture of science theme, as the core assumption is that girls do not have innate ‘feminine’ qualities. Interventions within the recategorize type aim at reappraising beliefs about incompatibilities between women and STEM by replacing the mutually-exclusive dichotomy STEM vs. FEMININE with multiple possible classifications, while resist interventions’ goal is to raise awareness on cultural gender stereotypes and provide strategies to counter or challenge them. Liben and Coyle (2014) pointed out that such a categorization only serves as an orientation, since interventions often pursue multiple goals simultaneously.

More recently, drawing upon Liben and Coyle’s (2014) taxonomy, Prieto-Rodriguez et al. (2020) have examined and classified a wider range of papers including more recent interventions. Goos et al. (2020), Sáinz et al. (2022), and Beroíza-Valenzuela and Salas-Guzmán (2024) have further contributed to such a classification objective, yet their reviews start from differents grounding theories or are guided by different criteria, starting from differents grounding theories or taking into account the influence of factors at the individual, family, institutional, and societal levels. Additionally, Casad et al. (2018) put the focus on specific interventions addressing psychological processes that inhibit gender equality in STEM education, also considering the variable of race.

Apart from the specific categories proposed, what emerges from these overviews is a variety of diverse strategies and interventions to address the critical barriers involved in women’s under-representation in STEM fields, which is clear evidence of the complexity of the phenomenon. Additionally, it seems that compulsory education does not provide students with the tools to view their personal experiences and interpersonal relationships at school, family and peer level through a gender perspective, and little attention is given to gender differences in the organizational structure.

In this paper, we present The Gender of Science (GoS) project, an intervention aimed at secondary school students and developed by researchers in physics with direct experience of horizontal segregation mechanisms within their scientific field. The project was implemented in several schools across urban and suburban areas of Naples, Southern Italy, a particularly critical area as regards school performance in STEM disciplines. For instance, in national mathematics tests for lower secondary schools (INVALSI 2023), students of this region recorded the lowest scores nationwide, falling 10.3 points below the national average. Furthermore, girls consistently scored lower than boys. The overall picture that emerges provides relevant indications on the persistent educational delay accumulated in the field of STEM disciplines especially by women and in some geographical areas, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions like the one presented here.

The GoS project aims to raise awareness of sociocultural gender stereotypes and roles among both male and female students and to guide them in recognizing the influence that gender plays in their educational choices and professional projections. Ultimately, this awareness may encourage more informed and conscious decision-making when students choose their bachelor’s degrees in Higher Education, helping to remove barriers to girls’ and women’s participation and success in STEM fields.

Although STEM disciplines are not explicitly included in the projects’ contents, students are introduced to a scientific approach to successfully analyze gender gaps and stereotypes within their own context and develop a Gender Report of their school. This is a key aspect of the project, as it encourages students to recognize the importance of gathering accurate data, critically evaluating sources, and interpreting information thoughtfully. As a result, students discover that science is not just theoretical, but also a practical tool for understanding real-life dynamics. Moreover, as it will be further illustrated, the project emphasizes students’ involvement through a cooperative and participatory approach, which makes the experience flexible and suitable to be adapted and modified depending on the specific participants’ needs and context.

After five years of carrying out the project in nine different schools, we wish to share our experience with the broader scientific community, with the hope that this may help identify areas for improvement in future implementations, wider dissemination, and the adaptation to earlier stages of the educational path. Therefore, in

Section 2, we provide a detailed description of the GoS project. To offer an initial evaluation of its impact,

Section 3 presents a qualitative analysis of the students’ Gender Reports, looking at how the experience has changed their perceptions; we also report a few examples of cumulative data.

Section 4 emphasizes the key aspects of the project and how it aligns with previous interventions. Some general conclusions and future perspectives are drawn in

Section 5.

2. The Gender of Science Project

The GoS intervention is designed for classrooms of students attending the three final years of secondary school, aged 15-19. We focused on this population because students in this age range begin to reflect on their educational and professional future, either as academic paths for tertiary education or considering their future placement in the labor market. As a result, they are in need of making conscious choices.

The GoS project is carried out with one classroom, with a number of students typically ranging from 20 to 30 (Active Group, from now on), and it has the objective of developing a Gender Report of their school by collecting and analyzing statistics of the school and responses to surveys administered to the entire student body (Peer Group, from now on). More details on the project structure may be found in

Section 2.2.

The intervention was developed and implemented by two authors (A.G. and A.L) of this paper, who are researchers in physics in Naples (the facilitators, from now on). It was carried out within the PCTO framework (Percorsi per le Competenze Trasversali e l’Orientamento - Pathways for Transversal Skills and Orientation), established by the Ministry of Education (Article 1, paragraph 785, Law of 30 December 2018). The third author (A.P.) is a researcher in applied linguistics and education, and collaborated in defining and designing the pedagogical approach of the intervention and analyzing students’ reports.

Between 2018 and 2023, the project was delivered in 9 mixed schools in the urban and suburban area of Naples, in Southern Italy, offering different types of curricula and located in diverse socioeconomic areas. To preserve confidentiality, each of the nine schools that took part in the project is identified with the code reported in

Table 1, along with the offered curricula, the number of students of the Active Group, and the number of survey’s respondents, namely the Peer Group. The total number of students in the Active Group was 196, including 79 females and 117 males. The Peer Group accounted for a total of 6913 students, with 3189 self-identifying as male, 3592 as female, and 132 as other.

2.1. Pedagogical approach

In designing the intervention, we relied upon a socio-constructivist approach, where students are required to take an active role in their learning process, and collaborate towards the co-construction of knowledge (Vygotsky, 1978). In accordance with student-centered principles, the teachers - or, in our case, the facilitators - take the role of guides, providing students with the tools and resources to carry out the tasks autonomously.

Specifically, the intervention takes the form of a project-based learning (PBL) experience, introduced by a gamification tool, that is, the LaleoLab board game. Broadly, PBL consists in working cooperatively to tackle a complex, interdisciplinary issue. PBL has been extensively proved to be an effective approach with learners of all ages, as they have the opportunity to engage creatively and reflectively in the learning process and develop practical, non-academic skills along with disciplinary knowledge (Kolmos et al., 2009). Such an approach supports students in shifting from dependent to self-directed learners (Grow, 1991).

In our intervention, students, in groups, are required to carry out a research project, quantitatively investigating gender roles and stereotypes within their school, family and peer contexts. The PBL experience, then, allows students to acquire and develop interdisciplinary and transversal skills, such as data collection and analysis, time management, data presentation, and report development and editing, among others. Such competences may prove useful for students’ future personal and professional life, as they may be applied in a variety of contexts both inside and outside the academic one.

The LaleoLab board game is a crucial component of the project. As a matter of fact, drawing from gamification techniques (Zainuddin et al., 2020), it plays the role of stimulating interest and motivation towards the topic among participants, enhancing scaffolding, and consequently boosting their engagement in the project. Moreover, such a tool fosters cooperative and collaborative learning further (Pujolàs, 2009). Therefore, the game activates students’ cognitive abilities and attitudes, alongside their interpersonal and behavioral skills, within a high involvement context. Also, when possible, game teams - as well as groups for the project - were formed mixing male and female students.

Finally, the project’s facilitators act as potential real-life positive role models - especially for female students (Isaacson et al., 2020) -, while also offering the opportunity to enrich the learning process with first-hand experience. Moreover, during the whole length of the project, the facilitators foster a positive atmosphere, showing flexibility, providing regular feedback at the different stages of the project, and slightly adapting contents and delivery to the target group.

2.2. Project structure

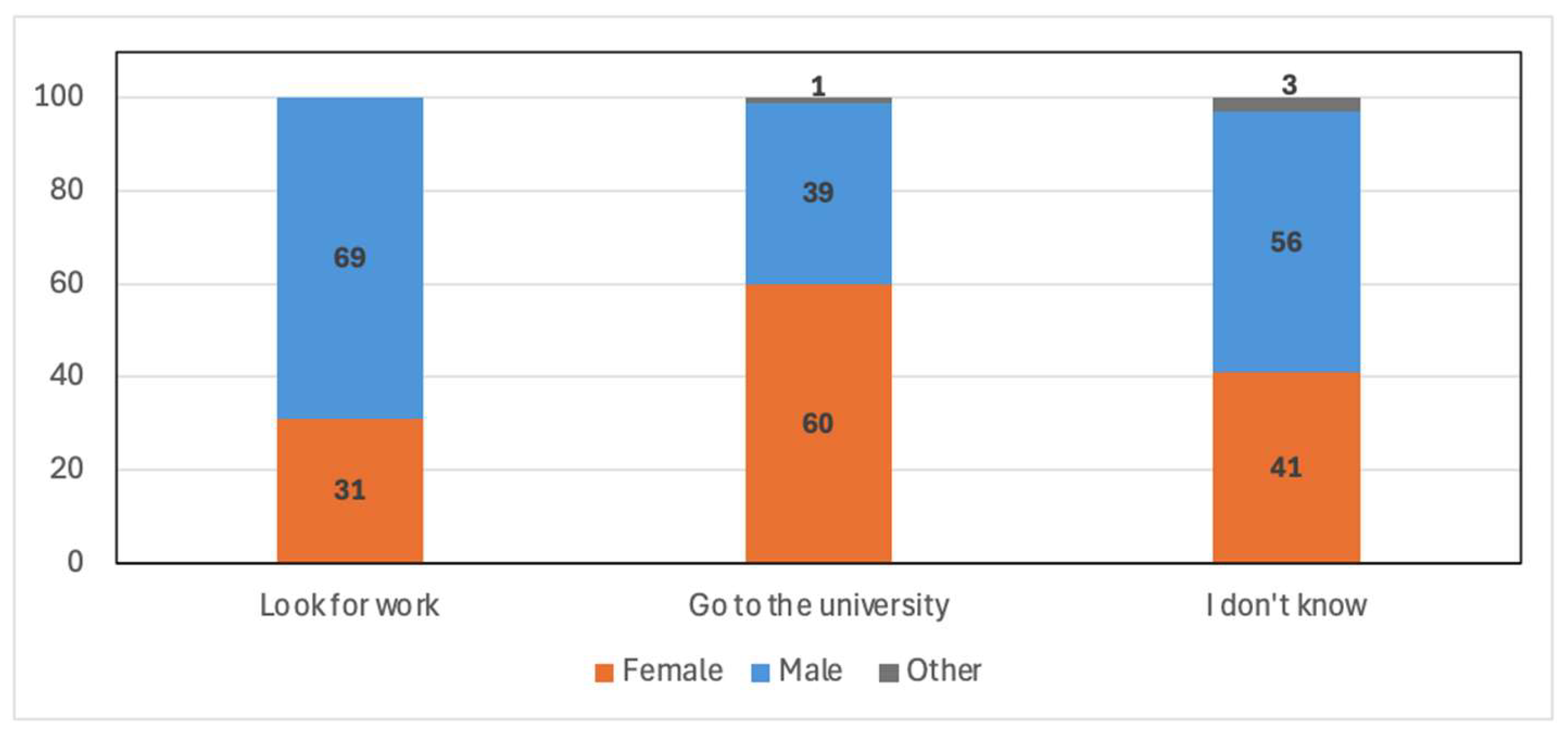

The GoS project is structured in several phases, distributed over a period of approximately eight weeks. Along with six 3-hour sessions led by the facilitators, students are also required to conduct autonomous work between each session, for a total workload of 30 hours. The phases are summarized in

Figure 1 and will be described in detail in the next sections. This structure is flexible, and can be slightly adapted according to students’ needs, requested support, and data availability. Activities take place on the school premises. Facilitators assist students during all the phases of the project, whether online or in person. Additionally, each classroom has one or more school teachers responsible for the project supervision.

2.2.1 First session: The LALEOLAB game

The first session is entirely dedicated to playing a board game, the LaleoLab game, specifically designed to encourage students to reflect on stereotypes, roles and prejudices in contemporary society. As mentioned, gamification boosts participants' direct involvement and motivation, serving as an effective brainstorming introductory activity. A photo taken during a play session is shown in

Figure 2.

The LaleoLab game is a modified version of the classic Taboo (Hasbro, 1989). In teams, players must make their teammates guess a word without naming the so-called taboos - terms typically associated with that word. The taboo words were chosen to purposefully elicit multiple meanings and connotations, particularly those based on the most gender-biased perceptions. Students are then challenged to think outside of the box and find new, creative ways to explain a concept without relying on its stereotypical connotations. Therefore, the game stimulates participants’ reflection on the value of words, the multiplicity of their meanings, and how their use in everyday situations often relates to gender stereotypes and biases.

The game also includes four types of “special cards”, thanks to which participants are introduced to the stories of famous role models, including stories of individuals from a variety of fields (i.e scientific/artistic/cultural/social/political) whose (gender) identity did not fit within social norms. The special cards thus encourage thinking on role models, their place in the society, and the impact they have on identity construction. These issues are further explored during the post-game discussion, where facilitators debrief and guide participants through the themes and difficulties encountered while playing.

Although the LaleoLab game was initially developed for the pedagogical intervention presented here, it now stands on its own. In fact, it has been presented and adopted at festivals and schools across Italy and was granted a patent in 2023 (Patent No. 2022/02593). Furthermore, the production of the game has been included in the Gender Equality Plan 2022-2024 of the University of Napoli Federico II. More details about the LaleoLab will be provided in an upcoming publication.

Figure 2.

High school students playing the LaleoLab board game.

Figure 2.

High school students playing the LaleoLab board game.

2.2.2. Development of the school’s Gender Report

During the second face-to-face session, the Active Group is introduced to the analytical and methodological tools to successfully carry out the analysis of their own context and develop the final Gender Report. First, the facilitators explain the relevance of gender issues, providing students with correct terminology and basic concepts on the topic. Definitions of key phenomena - such as gender gap, horizontal and vertical segregation - are provided and illustrated with examples from various domains, particularly from STEM fields.

In the second part of the session, students are familiarized with the indicators for each type of phenomenon they will have to analyze (e.g. glass ceiling index, femininity ratio, scissor diagrams, etc.), along with their generation and calculation methods. In this way, students get acquainted with basic mathematical and statistical concepts - e.g. mean, median, mode, and correlations - and learn how to work with Excel spreadsheets, analyzing data with pivot tables and generating different types of charts - e.g. color-scale graphs, histograms, and pie charts. The last part of the session is devoted to presenting examples of the data that the group should collect for the Report, including potential sources to retrieve data, and the structure of the survey to be administered to the Peer Group. The session also serves as an initial opportunity for students to reflect on their school environment, in order to adapt the data collection instruments and subsequent analysis to the specific characteristics of the context if needed.

Subsequently, the Active Group is divided into subgroups, each responsible for a specific task. Each subgroup works autonomously, while maintaining communication with the others by sharing information, exchanging suggestions, and providing the material resulting from their tasks. This structure promotes better work division and effective contributions from all participants. The Gender Report is, thus, a result of the collaborative effort of all the subgroups.

The tasks of each subgroup are the following ones:

-

A.

Collecting and Analyzing Statistics on School Students, Staff, and Teachers.

This subgroup gathers data from the school office, ministerial websites, or other sources needed to calculate specific gender equality indicators. In particular, the focus is on three aspects:

Gender composition of each school component (student, staff, teachers)

Horizontal segregation among students, teachers, and administrative staff (e.g. distribution of students across different fields of study and school subjects; distribution of teachers across different school subjects; distributions of administrative staff across different areas of activity)

Vertical segregation within each group (e.g. male/female ratios in school councils for parents, pupils, teachers and staff; analysis of the school's governance)

The collected data should be presented as graphs and tables and accompanied by interpretation.

-

B.

Administering and Analyzing Results from Anonymous Surveys on Gender Stereotypes.

This subgroup administers a survey to the entire student body of their school, the above-mentioned Peer Group. The aim of the survey is to explore the peers’ family context and the perceptions and awareness of boys and girls regarding gender issues. The survey is formed by 33 items. The first 3 questions collect data on the respondent's age, curriculum, and gender. The following 20 questions (1 open-ended and 19 multiple-choice) aim to explore the following areas:

Family environment and roles.

Cultural, sporting, and professional aspirations.

The influence of gender in their daily lives, both at home and at school.

Knowledge of role models in science.

The remaining 10 questions focus explicitly on gender stereotypes, reporting statements to which respondents must indicate their level of agreement (i.e. Likert-type items).

The subgroup is responsible for managing Google Forms, analyzing data with excel sheets and pivot tables, as well as elaborating figures, tables, and comments for the interpretation of the collected data.

-

C.

Editing the Gender Report document.

This subgroup drafts the school Gender Report by selecting materials, tables, and figures among those generated by the subgroups in charge of the two previous tasks. They also edit the document to ensure a cohesive presentation and develop the introduction and conclusion sections, incorporating feedback from the other two subgroups. Through this process, students learn how to write a scientific report, including how to present main findings, interpret data, justify results, and outline future perspectives.

Subsequently, all students revise the final version of the Report and present it to the rest of the school (i.e. sixth session) and at public events. The second, third, fourth, and fifth sessions, led by the facilitators, guide students throughout the whole process, supporting them in analyzing statistical data and surveys, editing the Report, and preparing the final presentation, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Analysis of students’ reports

Examining the Reports written by the students, we can clearly see their increasing awareness on gender issues. Through the data, students begin to recognize how gender mechanisms operate within their environments, shaping their behaviors and interactions. To illustrate this process, we present a selection of excerpts from the students’ work organized along three main themes: (1) the school context, (2) peers’ educational choices, and (3) the family context. Additionally, we include some general observations made by the students in their reports, along with some reflections. The codes used to identify schools, which are reported alongside each excerpt, are those already listed in

Table 1.

3.1. Awareness in the school context

In this section, we summarize students’ findings as concerns their schools’ gender composition (teaching staff, technical-administrative staff, and student component) resulting from the analysis of data extracted from the school’s official documents, sometimes supported by national Ministry’s statistics. Even though the participating schools differ in several aspects, such as the offered curricula and the number of female/male enrolled students, all Gender Reports present a similar picture regarding the percentages of women and men among teachers, as well as their distribution across the disciplines.

Students recognize that the school staff - both teaching and non-teaching- is primarily composed of women, as exemplified in the following two excerpts:

E1: “Out of a total of 117 teachers, the prevailing presence is the female one. The same trend is observed for the curriculum and special projects’ coordinators.” (S3)

E2: “The presence of women (among teachers) has been prevalent for years, and women have become the majority in recent years also in the case of managerial roles and responsibilities.” (S6)

Nevertheless, students also note that some “instrumental” tasks - including organizational, planning and coordination duties, which often correspond to better remuneration (Pirola, 2015) - are primarily attributed to men:

E3: “Among staff in charge of Instrumental Functions, a larger male component is found.” (S7)

Interestingly, participants connect the high presence of women among teachers to broader assumptions about the traditional role of women as caretakers of the home and the family:

E4: “Observing the data collected on the school body, as concerns the component of who work at school, shows that [...] school teaching, in the last decades, has been considered as one of the more suitable jobs for women, ‘allowing’ them to pursue a professional career while maintaining their traditional roles and tasks of taking care of the home and family.” (S6)

Students also recognize the mechanisms of horizontal segregation among the teaching staff, noting the high concentrations of female teachers in artistic and literary subjects and male teachers in technical and laboratory areas:

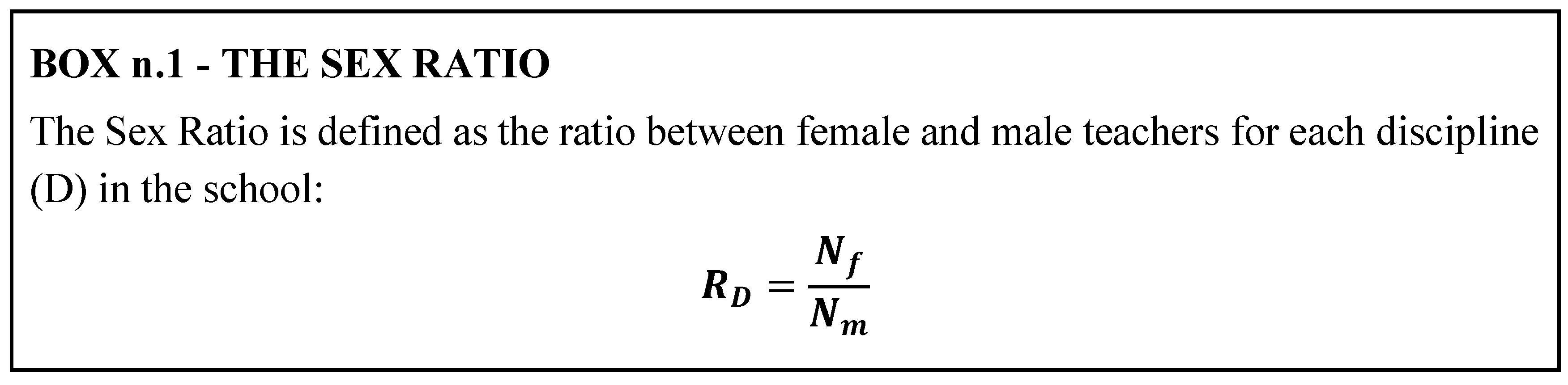

E5: “In foreign languages there are only women teachers, indeed the sex ratio [see Box n.1] results in infinity. Also in other subjects, female teachers are predominant, except for chemistry and biology, where there is parity between the two genders. Lastly, religion, technology and informatics show a prevalence of male teachers.” (S3)

In their reports, students also highlight the mechanisms of horizontal segregation within the student body of their school. Similar to what observed for teachers, they note that the percentage of male students choosing scientific curricula is more than double than that of female students. For instance, students state:

E6: "The most common choice among male students is the scientific curriculum, while for female students is primarily the linguistic one, followed by the humanities curriculum [...] in technical and professional institutes, as usual, there are more boys than girls." (S3)

E7: "We can notice a radical difference, especially for the sportive and applied sciences curricula, where there is a male prevalence." (S9)

A group of participants attempt a possible - albeit somewhat simplistic - explanation of this phenomenon:

E8: "[...] ascribable to the fact that men have always been considered more inclined towards scientific subjects, as they often aspire to jobs requiring skills in fields, such as engineering." (S3)

To explore vertical segregation within the student body, the roles of class and school representatives were examined. In all schools, students indicate that the apical school representative role is typically attributed to male students, regardless of whether females make up the majority of the school body or not. The school representatives are members of the School Board, which is responsible for the policy and management of economical and organizational aspects. However, this role is interpreted in terms of personality traits that are stereotypically associated with men, as well as women’s tendency to seek environments where they feel “at home”:

E9: “From the graph (see Fig. 3), it can be observed that, despite the school’s female majority, the school representative roles are clearly male-dominated. One possible interpretation of this is that male students are more likely to apply for these roles and tend to be more daring in promoting their election campaign. In contrast, female students tend to be more shy, consequently exposing themselves less in broader environments such as the school board, while they feel more at home in settings such as that of their own classroom.” (S4)

Figure 3.

Scissors graph showing the gender distribution within student representative roles (figure adapted from the Gender Report of S4).

Figure 3.

Scissors graph showing the gender distribution within student representative roles (figure adapted from the Gender Report of S4).

3.2. Peers’ educational choices

This section reports a selection of comments related to the analysis of the surveys administered by the Active Groups to the Peer Groups. In particular, here we focus on those items tapping into students’ educational preferences and professional aspirations.

As concerns students’ favorite school subjects, all participants report that male students feel they

E10: “...have an aptitude for sport, informatics, and applied sciences”, while the “female majority prefers literary and humanities subjects, foreign languages, as well as artistic and music disciplines.” (S5)

Informatics is identified as a particularly critical area, and it is interpreted as a manifestation of the common assumption that individuals show different skills depending on their sex:

E11: “Interesting is the picture regarding informatics, revealing a remarkable gender asymmetry, with the presence of only 4 out of the 528 school’s female students. The reason for such an imbalance is due to the deeply rooted belief that there are feminine subjects and masculine subjects, a belief that finds its origin in gender stereotypes.” (S7)

Moreover, favorite subjects, as well as those in which students feel they have an aptitude, appear to play a key role in shaping their professional aspirations. In fact, participants report that:

E12: “Girls are more inclined to choose a job in the humanities field and, as a second option, in the medical one. On the contrary, the majority of boys are more likely to choose a profession in the scientific field.” (S7)

These findings are not surprising, as they align with previous observations regarding horizontal gender segregation among teachers, and thus suggesting a similar pattern in the near future. Students themselves critically reflect on this phenomenon and its potential consequences, questioning the extent to which prevailing gender stereotypes inhibit their conscious and unrestricted choices for future careers:

E13: “As a consequence, when choosing their undergraduate degree and, thus, their professional career, male students will be more likely to consider STEM disciplines. It is worth questioning to what extent the clear male predominance may have an influence in the choices of those female students who would be interested in these fields, but are drawn back by the preconceptions circulating in the university environment and the job market. If these female students were to choose a scientific degree anyway, would they run the risk of being penalized compared to their male classmates?” (S3)

Meanwhile, participants also observe that, despite horizontal segregation, a larger number of young women aspire to enroll in higher education compared to young men, as exemplified by the following extract:

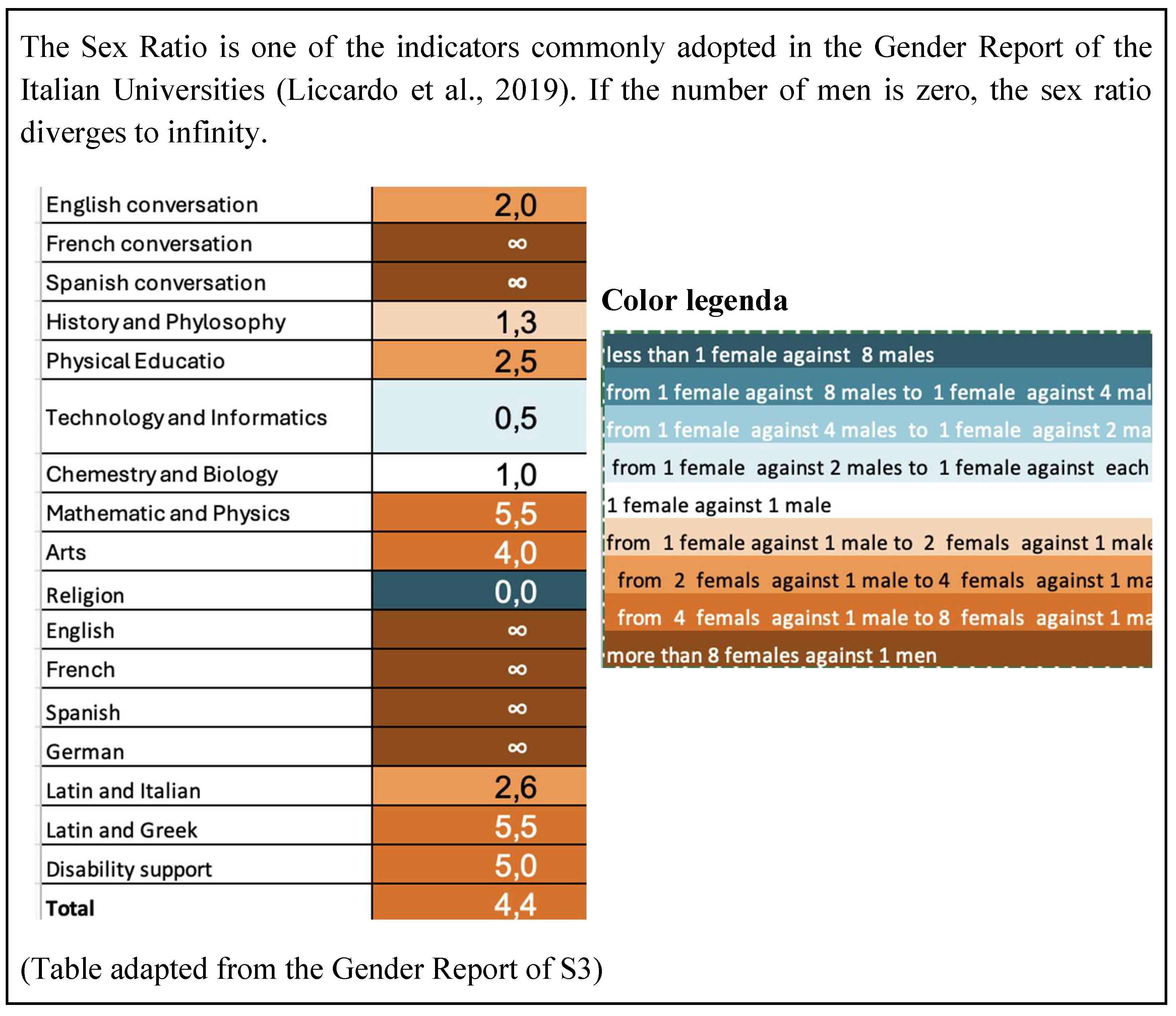

E14: “Regarding the question of what professional path students wish to pursue after secondary school, the figure (see Fig. 4) shows that the majority of male students feel insecure about their future or choose to look for work straight away, while a large percentage of female students plan to continue their studies.” (S7)

Figure 4.

Students’ aspirations after high school by gender (figure adapted from Gender Report of S7).

Figure 4.

Students’ aspirations after high school by gender (figure adapted from Gender Report of S7).

Actually, these results do not indicate a temporary, context-dependent aspiration of women; rather, they are corroborated by the growing gap between men and women in university completion. Eurostat (1992-2023) reports that the percentage of women with tertiary education is 48%, significantly higher to the 37% reported for men.

3.3. Awareness in the family context

In this section, we report the findings from students’ analysis of the surveys regarding gender roles and stereotypes in the family context. Once again, the data enable students to identify gender-stereotyped behaviors that confirm the typical roles assigned to female and male individuals by the society.

All reports indicate that domestic work and interactions with schools are still predominantly the responsibility of mothers in all students’ families, as exemplified by the comments:

E15: "The roles of women and men in the family organization are well defined: it is evident, in fact, that the woman is primarily in charge of domestic care, while the economic aspect is managed by both parents or by the man, and more rarely it is an exclusively female task." (S4)

E16: “In the Class Council, there is a high prevalence of women representing parents. As it has been said before, our society is still tied to a patriarchal reality, which is why women are the ones taking care of children and their education." (S3)

The analysis of the surveys also makes evident that the family environment strongly influences students’ beliefs. In fact, a significant percentage of both male and female students - though the latter to a lesser extent - have internalized the role models of their families:

E17: “Almost 70% of the male students agree (completely or somewhat) with the idea that men should provide financial support to the family.” (S7)

E18: "It should be noted, however, that the percentage of women who still believe that they should take care of domestic work more than men is far from negligible (31.9%)." (S3)

Some students attempt a possible explanation for the different perception of women and men with respect to their role in the family organization:

E19: “It is particularly evident how strong the stereotypes are concerning the role of men as ‘economic support’ and of women as ‘angels of the home. Such stereotypes are, however, much more widespread among boys than among girls, which we interpret as a sign of their desire to free themselves from such limiting preconceptions.” (S4)

The contribution of students to housework mirrors their parents’ tasks, with girls contributing to cleaning and tidying up at a larger percentage. Interestingly, boys tend to participate more in cooking tasks:

E20: "There is a greater participation of women, especially with regard to house duties (general cleaning, clearing the table and washing dishes, tidying up the room). A peculiarity is that, although men’s participation in the survey is lower, there is a slight majority contributing to cooking tasks." (S5)

3.4. Students’ general observations

Overall, the acquisition of data and their analysis in preparing the report provide students with the opportunity to observe first-hand that gender segregation is already present at secondary school level, well reflected in the horizontal segregation among teachers and the uneven distribution of students across different curricula. Furthermore, students start exploring how gender norms influence their Peer Groups:

E21: “The administration of questionnaires turned out to be an excellent opportunity to get in touch with a very large peer community and understand how the patriarchal legacy is still ingrained in society.” (S7)

However, some of the findings are quite unexpected for participants. In fact, during in-class discussions prior to data collecting, most students claimed that no substantial differences exist between female and male roles and behaviors in contemporary times. These inconsistencies between students’ assumptions and the surrounding reality are also highlighted in the final reports:

E22: "We, students of the [class], have come across sometimes unexpected numbers, that have certainly overturned our expectations and that already mark a great progress in the collective perception. From most of the questions, however, emerged a reality that is decisively inconsistent with the great revolutionary spirit of an entire generation, which is increasingly concerned with social problems like this." (S5)

After the initial surprise, discovering that stereotypes still exist among their peers stimulated participants’ critical thinking skills. Indeed, throughout the text, they raise relevant questions about their own choices and those of their peers, as well as about the social influences at play:

E23: "Deepening the crucial aspects of gender issues, by means of data that confirmed them, made us more aware of the work that still needs to be done, especially among the new generations. Awareness on this issue must necessarily be raised in primary and lower secondary schools, with the aim of stimulating students to have a more neutral attitude, without being influenced by stereotypes." (S3)

E24: “The data collected show us an interesting picture of students' perception on gender discrimination. What emerges, therefore, is a context in which, on the one hand, stereotypes related to sex still exist among young people, and on the other hand, there is a lack of interventions aimed at counteracting these prejudices. Intervening on us, young people, means fostering a cultural change and fighting stereotypes and prejudices related to gender, before they are transmitted unknowingly.” (S4)

In summary, through data analysis, students recognize that young people often do not examine reality through a gender lens, resulting in the unconscious absorption of stereotypes. In this context, they emphasize the need for specific interventions addressing gender roles and stereotypes and highlighting the crucial role that schools play in this process.

3.5. A snapshot from cumulative data

In this section, we present some cumulative descriptive results emerging from the surveys administered to the entire school by the students in the nine classrooms involved in the GoS project. This dataset includes approximately 7000 students, aged 13-19, from different curricula and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Our aim is to provide an overview of students’ responses through a few examples, in order to contextualize the reports’ extracts presented in previous sections in a broader framework and identify general tendencies. It should be noted that the cumulative data from all the nine schools align with the findings from each school individually, presenting a consistent picture regardless of students' curricula and socioeconomic background. Specifically, we focus on three multiple-choice survey items, which we believe are key aspects in addressing the gender gap: the first two pertaining to the family context and the third to the peer context. The remaining items of the survey will be analyzed in future publications.

Table 2 and

Table 3 report the responses to two questions tapping into gender tasks in students’ families, respectively, “Who takes care of the financial care, household matters, and the relationships with school in your family” and “What are your tasks in the household management?”.

As shown in

Table 2, 5000 respondents (72% of the total) reported that, in their family, domestic care (i.e. household matters) is mainly a mother’s duty, while only 1.8% selected ‘father’ as the answer. As concerns relationships with the school, fewer respondents, but still the majority (54%), indicated that this is a female responsibility. On the other hand, half of the respondents reported financial care to be a duty shared by both parents, while only 8.8% indicated that only the mother takes care of money.

Cumulative data on areas in which respondents contribute to domestic duties mirror these findings to some extent. Specifically, the percentage of female students responsible for the general house cleaning is double that of male students (29.3% vs. 13.8%). Marginal gender differences are observed in tasks such as clearing the table and tidying up their own room. However, surprisingly, as noted earlier, the percentage of male students reporting involvement in cooking is higher than that of female students (12.1% vs. 9.6%).

These data show that traditional gender roles within the family environment continue to prevail in the vast majority of cases, with a significantly larger involvement of women in household and caregiving responsibilities, although their contribution to financial care has increased through the years.

Table 4 summarizes students’ professional aspirations - the responses to the question “In which field would you like to work?” - split by self-reported gender. Again, a clear gender bias emerges, as only 31% of students planning to enter STEM fields are female, a percentage that is only slightly smaller than the proportion of tertiary graduated women in these fields. Female students tend to see their professional future in health and care fields (27.6%), while male students predominantly envision themselves in STEM-related careers (27.9%).

4. Discussion

The GoS project belongs to the educational interventions aiming at reducing the gender gap, in particular in the STEM area. What makes the project innovative is the fact that here STEM disciplines are not the direct focus or explicit content of the project but are instead the method proposed to students to analyze their context from a gender perspective.

Due to its strong focus on gender stereotypes and roles, the GoS project, as for its animating principle, aligns with Brotman and Moore’s (2008) nature and culture of science theme and Liben and Coyle’s (2014) resist type. However, the project is not exhausted in the mere transmission of main concepts, terminology and basic information on these issues. On the contrary, the crucial aspect of our intervention is that students are prompted in conducting a first-hand investigation on the gender stereotypes and roles that regulate their own life, in the family, school, and peer contexts.

Direct data gathering and analysis emerges as a critical step to raise deep awareness among students. Indeed, an interesting aspect is that, in almost all the schools involved in the GoS project, students were initially skeptical about national and international statistics on gender roles and stereotypes in family, workplace, and education. By opposing official data with their personal experience, students naturally gave more weight to their own experience than to statistics, which they see as distant and not representative of their reality. Only after having personally analyzed the data of their context and uncovered the same gender roles and stereotypes, students appreciated the objectivity of data and acknowledged the existence of gender issues. Such a scientific, quantitative approach, then, provides students with those critical thinking skills needed for disclosing and interpreting the gender mechanisms rooted in society.

Therefore, even though STEM disciplines provide the analytical method rather than the content of the project, students have the opportunity to view the scientific approach as a powerful tool of investigation, regardless of the specific discipline or the gender typically associated with it. In our opinion, this feature emphasizes the transversality of science, challenging the dichotomy STEM and FEMININE as mutually exclusive categories. As such, our intervention can also be classified within the Recategorizing type of Liben and Coyle’s (2008) framework.

There are two additional aspects of the GoS project that we think are worth pointing out, linked to key concepts in educational interventions: role models and disciplinary identity.

One of the strategies adopted to encourage girls to pursue STEM education is to expose them to role models of female scientists (Adedokun et al., 2012; Farland-Smith, 2009; Stoddard, 2009), precisely to endorse that being a member of the female category does not preclude being a member of the scientist category. However, literature is controversial regarding the efficacy of role-model interventions (De Gioannis et al., 2023). Some studies point out that this approach does not alter girls' projection in STEM careers, but only their appreciation to women scientists as smart and creative (Bamberger, 2014). Exposure to role models, especially if occasional and perceived as distant from oneself, may even be counterproductive (Betz & Sekaquaptewa, 2012). Nevertheless, research shows that the most influential factor in improving girls’ motivation and self-efficacy in STEM fields is becoming familiar with women scientists working in STEM through formal and informal long-term interactions, along with encouragement and support from parents and teachers (Kelly, 2016). For instance, in a survey conducted by “Girls who code” and “Logitech” (Logitech, 2022), when asked who had the greatest influence on their decision to pursue a career in tech, 60% of adult females responded a family member, a friend, or a teacher.

While the GoS intervention does not explicitly focus on role models, the facilitators, interacting with students during more than two months, may serve as potential positive role models. They not only provide an opportunity for students to meet real-life examples of women in science, but also enrich the learning experience by sharing personal insights and first-hand knowledge from their own professional journeys.

Furthermore, role models enter into the project through the Laleolab game. Indeed, there are some cards that tell the stories of women who significantly contributed to a scientific field but whose contribution has often not been recognized, drawing attention to gender marginalization. Additionally, other cards encourage reflection on role models in a more general perspective by showcasing a variety of famous individuals - such as scientists, artists, and researchers - who challenge stereotypical ideas about gender and other social norms. These examples highlight how significant figures in history, whether men or women, often defied conventional role expectations by possessing traits that do not align with socially assigned roles. The goal is to help students deconstruct the widespread stereotypes commonly associated with these roles.

In this connection, the construct of disciplinary identity is crucial, as it refers to the ability of an individual to identify with a specific discipline and to have career aspirations within that field. As mentioned in the Introduction, the role of identity in students’ engagement with learning in science is one of the themes proposed by Brotman and Moore (2008) to classify gender interventions in science education, and recently investigated by Galano et al. (2023) focusing on the effects of gender stereotypes on scientific identity.

This idea implicitly emerges from the Gender Reports, for instance in E13, where students reflect to what extent the ‘sense of belonging’ within a field - a key aspect of disciplinary identity - can affect their educational choices (Hazari et al., 2010; Hazari et al., 2020). Therefore, the GoS project explicitly encourages reflection on this issue, as students quantitatively explore differences in favorite school subjects and potential career fields according to gender. Collecting and analyzing these data, students develop awareness that gender stereotypes are the primary cause of the deeply ingrained belief that there are ‘feminine’ subjects and ‘masculine’ ones (see, for instance, E10 and E11). Consequently, they may also be prompted to reframe their disciplinary identity and move towards more conscious future choices based on their own aspirations and attitudes rather than on generalized stereotypes.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented the Gender of Science project, a pedagogical intervention targeted at secondary school students with the aim of raising awareness on gender roles and stereotypes in their school and personal life. We have also shown the impact of the project through a qualitative analysis of the students’ Gender Reports.

One of the strongest points of our intervention is that it triggers continuous exchange of information and collaboration among the various actors involved at different levels. In order to prepare the Report, interactions are required among both students within one sub-group and the sub-groups themselves, as well as between students and facilitators. The Active Group is also required to engage with the other students of the school when administering the questionnaires or presenting their findings, as well as with various institutional components such as administrative and management staff, and teachers when collecting data. Furthermore, throughout the project, students acquire and put into practice multiple competencies and skills needed for identifying, analyzing, and contextualizing the phenomenon under investigation, accurately structuring and editing a research report, and preparing a coherent and well-argued presentation – both written and oral – of the collected material. As a result, students not only develop greater attention and critical thinking towards gender issues but, using a scientific approach, they also recognize the importance of working interdisciplinary and cooperatively. Additionally, this entire process is fundamental for facilitators in their own learning journey.

Nevertheless, the project is certainly susceptible to improvement. First, it is more effective when the school teachers responsible for the project demonstrate a high level of engagement, providing consistent support to students throughout all phases. Therefore, conducting prior training sessions with teachers could be beneficial. Second, we have learned that the survey should be revised, carefully reviewing the response options given for some items and reformulating some questions to clarify whether they ask for the respondent’s personal opinion or for their observations about societal behaviors. Looking at the future, we plan to conduct an in-depth cumulative analysis of all the data collected in the various schools, as well as of the long-term impact of the project on students’ awareness. To this purpose, in future implementations we will collect data from a control group to enhance the reliability of the analyses. Moreover, we are working to adapt the project to earlier stages of the educational path (i.e. primary and lower secondary schools) and translating the board-game into other languages.

Overall, data from the reports indicate that, when encouraged and guided, students are capable of reflecting on gender roles and stereotypes, and targeted interventions can enhance their awareness, at least in the short term. However, the cumulative findings also reveal that traditional roles and aspirations persist, highlighting that the journey toward closing the gender gap in education remains a long one. As such, we join the call for implementing specific interventions within compulsory education to address these challenges.

6. Patent

The LaleoLab board game was granted a patent in 2023 (Patent No. 2022/02593).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: A.L. A.G. A.P.; project administration: A.L., A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Authors are available to share the project data upon request.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank all the participating schools who made this project possible. We also thank Prof. Emilio Balzano and Prof. Italo Testa for their valuable feedback, Dr. Maria Rosaria Masullo and Coordinamento Napoletano Donne nella Scienza for supporting the implementation of the project, and Dr. Silvia Galano and Prof. Francesca Dovetto for their contribution to the Scientific Committee of the board game.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adedokun, O.A., Hetzel, K., Parker, L.C., Loizzo, J., Burgess, W.D., & Robinson, J.P. (2012). Using virtual field trips to connect students with university scientists: core elements and evaluation of zipTrips. J Sci Educ Technol, 21(5), 607–618. [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, Y.M. (2014). Encouraging Girls into Science and Technology with Feminine Role Model: Does This Work? J Sci Educ Technol, 23, 549–561. [CrossRef]

- Beroíza-Valenzuela, F., & Salas-Guzmán, N. (2024). STEM and gender gap: a systematic review in WoS, Scopus, and ERIC databases (2012–2022). Front. Educ., 9:1378640. [CrossRef]

- Betz, D.E., & Sekaquaptewa, D. (2012). My fair physicist? Feminine math and science role models demotivate young girls. Soc Psychol Personal Sci, 3(6), 738–746. [CrossRef]

- Brotman, J. S., & Moore, F. M. (2008). Girls and science: a review of four themes in the science education literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(9), 971–1002. [CrossRef]

- Casad, B.J., Oyler, D.L., Sullivan, E.T., McClellan, E.M., Tierney, D.N., Anderson, D.A., Greeley, P.A., Fague, M.A., & Flammang, B.J. (2018). Wise psychological interventions to improve gender and racial equality in STEM. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(5), 767–787. [CrossRef]

- De Gioannis, E., Pasin, G.L., & Squazzoni, F. (2023). Empowering women in STEM: a scoping review of interventions with role models. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 13(3), 261–275. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (1992-2023). Population by educational attainment level, sex and age (%) - main indicators. Accessed on 05.09.2024. [CrossRef]

- Farland-Smith, D. (2009). Exploring middle school girl’s science identities: examining attitudes and perceptions of scientists when working ‘‘side-by-side’’ with scientists. Sch Sci Math, 109(7): 415–427.

- Galano, S., Liccardo, A., Amodeo, A.L., Crispino, M., Tarallo, O., Testa, I. (2023). Endorsement of gender stereotypes affects high school students’ science identity. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res., 19. [CrossRef]

- Gender Equality Strategy (2020) A Union of Equality: Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0152.

- Global Gender Gap Report (2023). Retrieved from: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf.

- Goos, M., Ryan, V., Lane, C., Leahy, K., Walshe, G., O’Connell, T., O’Donoghue, J., & Nizar, A. (2020). Review of Literature to Identify a Set of Effective Interventions for Addressing Gender Balance in STEM in Early Years, Primary and Post-Primary Education Settings. STEM Education Team at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick.

- Grow, G.O. (1991). Teaching Learners to be Self-Directed. Adult Education Quarterly, 41(3), 125–149. [CrossRef]

- Haussler, P., & Hoffmann, L. (2002). An intervention study to enhance girls’ interest, self-concept, and achievement in physics classes. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39, 870–888.

- Hasbro (1989). Taboo [Board game]. Hasbro.

- Hazari, Z., Sonnert, G., Sadler, P.M., & Shanahan, M.C. (2010). Connecting high school physics experiences, outcome expectations, physics identity, and physics career choice: A gender study, J. Res. Sci. Teach., 47, 978 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Hazari, Z., Chari, D., Potvin, G., & Brewe, E. (2020). The context dependence of physics identity: Examining the role of performance/competence, recognition, interest, and sense of belonging for lower and upper female physics under- graduates. J. Res. Sci. Teach., 57, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. (2001). Exploring the availability of student scientist identities within curriculum discourse: An anti-essentialist approach to gender-inclusive science. Gender and Education, 13, 275–290. [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, S., Friedlandera, L., Megeda, C., Havivia, S., Cohen-Zadaa, A.L., Ronaya, I., Blumberga, D.G., & Mamanb, S. (2020). She Space: A multi-disciplinary, project-based learning program for high school girls. Acta Astronauta, 168, 155-163.

- INVALSI (2023). Retrieved from https://invalsi-areaprove.cineca.it/docs/2023/Rilevazioni_Nazionali/Rapporto/Rapporto%20Prove%20INVALSI%202023.pdf.

- Liben, L.S., & Coyle, E.F. (2014). Chapter three - Developmental Interventions to Address the STEM Gender Gap: Exploring Intended and Unintended Consequences. In L.S. Liben & R.S. Bigler, Advances in Child Development and Behavior, JAI, Volume 47, 77-115. [CrossRef]

- Liccardo, A., Borelli, S., Canali, C. D., Onghia, M., Damiani, M., Di Letizia, C., Gianecchini, M., Oppi, C., Pisanti, N., Rosselli, A., Siboni, B., Tomio, P. (2019). Linee guida per il Bilancio di Genere negli Atenei italiani Fondazione CRUI, Roma. ISBN 978 8896524305.

- Logitech (2022). “What (and Who) is Holding Women Back in Tech?”. logi-wwc-report.pdf.

- Kelly, A.M. (2016). Social cognitive perspective of gender disparities in undergraduate physics. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, S.S. (1998). Overview of feminist perspectives on the ideology of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 35, 837–844.

- Kolmos, A., De Graaff, E., & Du, X.Y. (2009). Diversity of PBL- PBL learning principles and models " In X.Y. Du, E. De Graaff & A. Kolmos (Eds.), Research on PBL Practice in Engineering Education. Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: Sense Publishers, 9-21.

- Jovanovic, J., & Steinbach King, S. (1998). Boys and girls in the performance-based science classroom: Who’s doing the performing? American Educational Research Journal, 35, 477–496.

- McGuire, L., Mulvey, K.L., Goff, E., Irvin, M.J., Winterbottom, M., Fields, G.E., Hartstone-Rose, A., & Rutland, A. (2020). STEM gender stereotypes from early childhood through adolescence at informal science centers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2023). OECD Dashboard on Gender Gaps. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/dashboards/gender-dashboard.html.

- Prieto-Rodriguez, E., Sincock, K., & Blackmore, K. (2020). STEM initiatives matter: Results from a systematic review of secondary school interventions for girls. International Journal of Science Education, 42(7), 1144–1161. [CrossRef]

- Pujolàs, P. (2009). Aprendizaje cooperativo y educación inclusiva: una forma práctica de aprender juntos alumnos diferentes. VI Jornadas de cooperación educativa con iberoamérica sobre educación especial e inclusión educativa: Guatemala.

- Sáinz, M., Fàbregues, S., Romano, M.J., & López, B.S. (2022). Interventions to increase young people's interest in STEM. A scoping review. Front. Psychol., 13. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J. (2009). Toward a virtual field trip model for the social studies. Contemp Issues Technol Teach Educ, 9(4), 412–438.

- UNESCO (2019). Fact Sheet No. 55 FS/2019/SCI/55. Retrieved from https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs55-women-in-science-2019-en.pdf.

- UNESCO (2020). Global Education Monitoring Report: Gender report, A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education. Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374514.

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S.K.W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C.J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).