Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The increasing use of large glass surfaces in modern architecture requires robust adhesive solutions that balance aesthetic appeal with structural resilience, particularly in timber-glass applications. This study examines the influence of primer treatments on the shear performance of timber-glass adhesive joints, employing a combination of experimental testing and simulation techniques. Double-lap shear tests with epoxy adhesives assess the impact of various surface treatments on joint stiffness, shear stress distribution, and deformation. Additionally, a finite element model is developed to simulate joint behavior, evaluate failure modes, and analyze displacement patterns. Results indicate that primer applications notably enhance structural integrity by reducing displacement and increasing joint stability, thereby supporting more durable timber-glass assemblies. These findings offer valuable insights for advancing adhesive technologies in architectural components, enabling a closer alignment between structural performance and design innovation in timber-glass systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

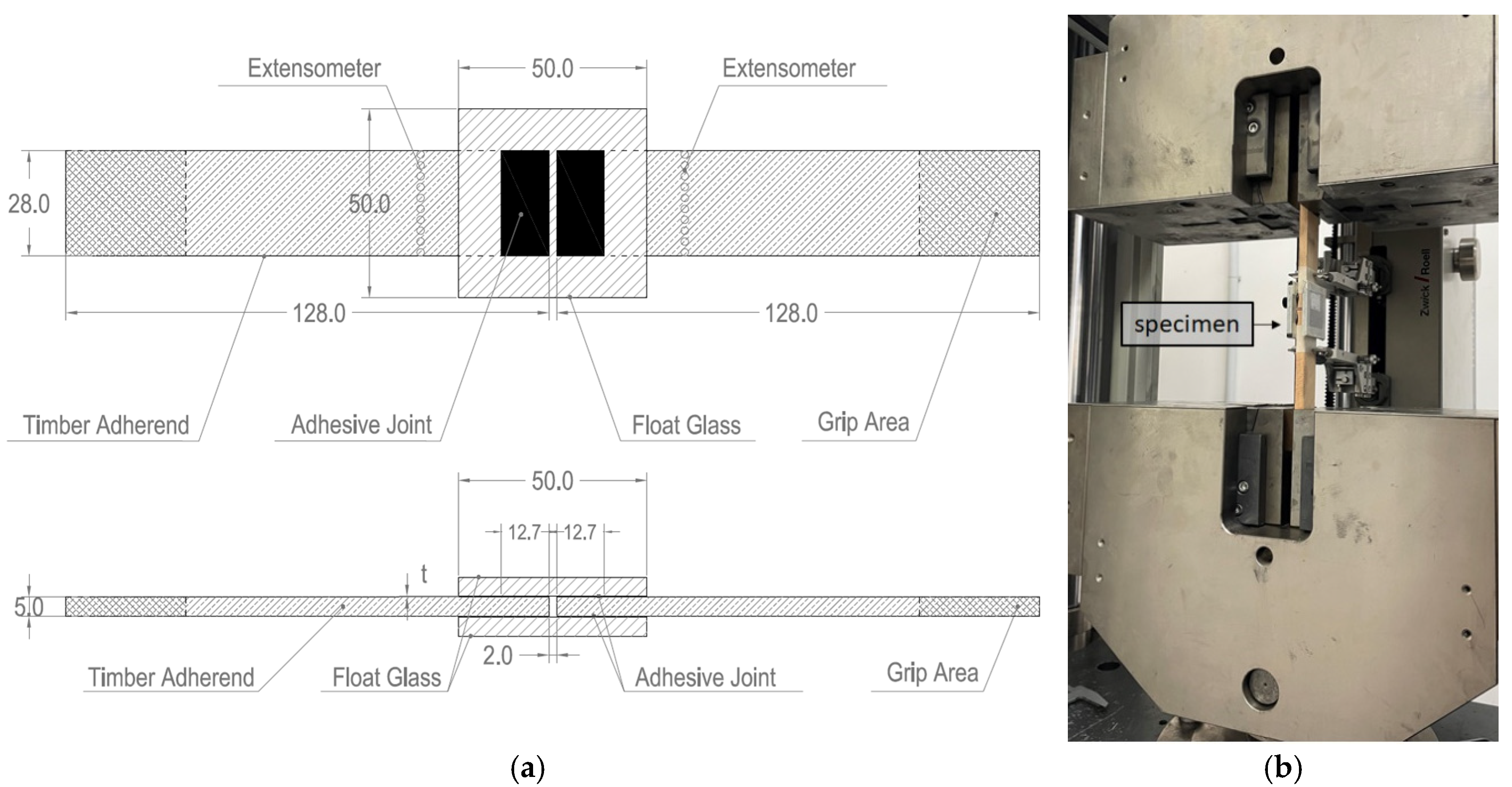

2. Materials and Methods

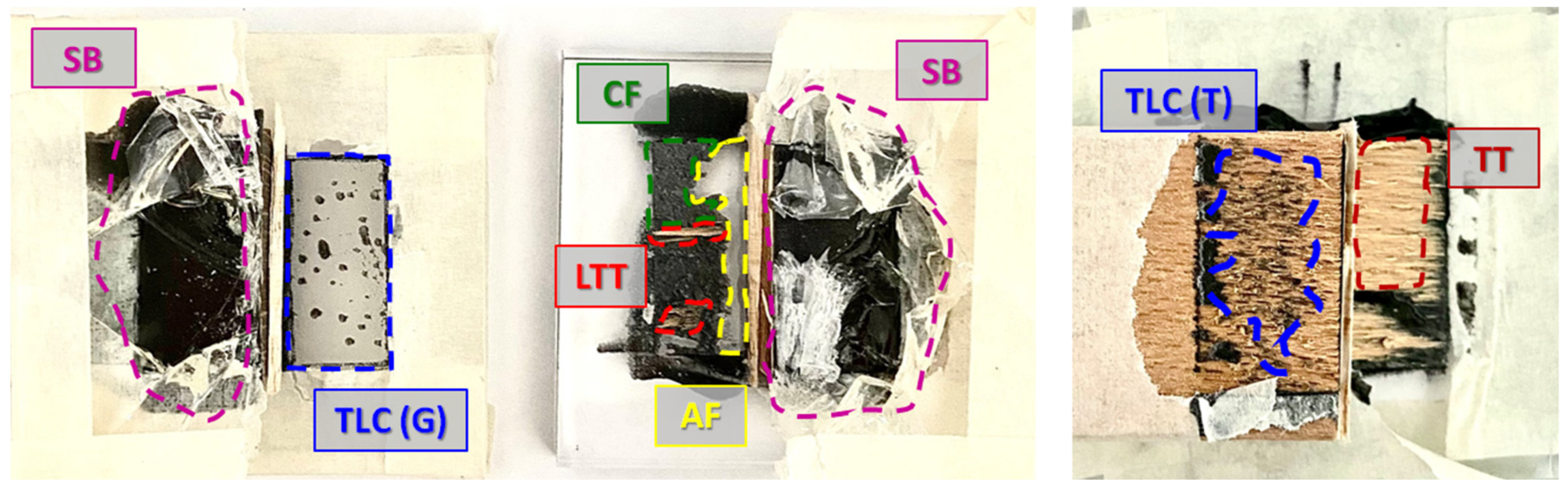

- Adhesive Failure (AF): occurs at the interface between the adhesive and the adherend when the resistance of the interface (adhesion strength) is less than that of the adherend.

- Cohesive Failure (CF): occurs within the adhesive, therefore the latter is present on both fracture surfaces.

- Thin-Layer Cohesive Failure (TLC): cohesive failure occurring very close to the adhesive-substrate interface, characterized by a “light dusting” of adhesive on one substrate surface and a thick layer of adhesive left on the other.

- Timber-Tear Failure (TT): failure occurring exclusively within the timber component, characterized by the presence of timber fibers on both ruptured surfaces.

- Light-Timber-Tear Failure (LTT): timber failure characterized by a thin layer of timber fibers visible on the adhesive.

- Stock-Break Failure (SB): break of the glass substrate outside the adhesively bonded-joint region, often occurring near it.

- Mixed Failure (MF): any combination of two or more of the previous classes of failure mode described.

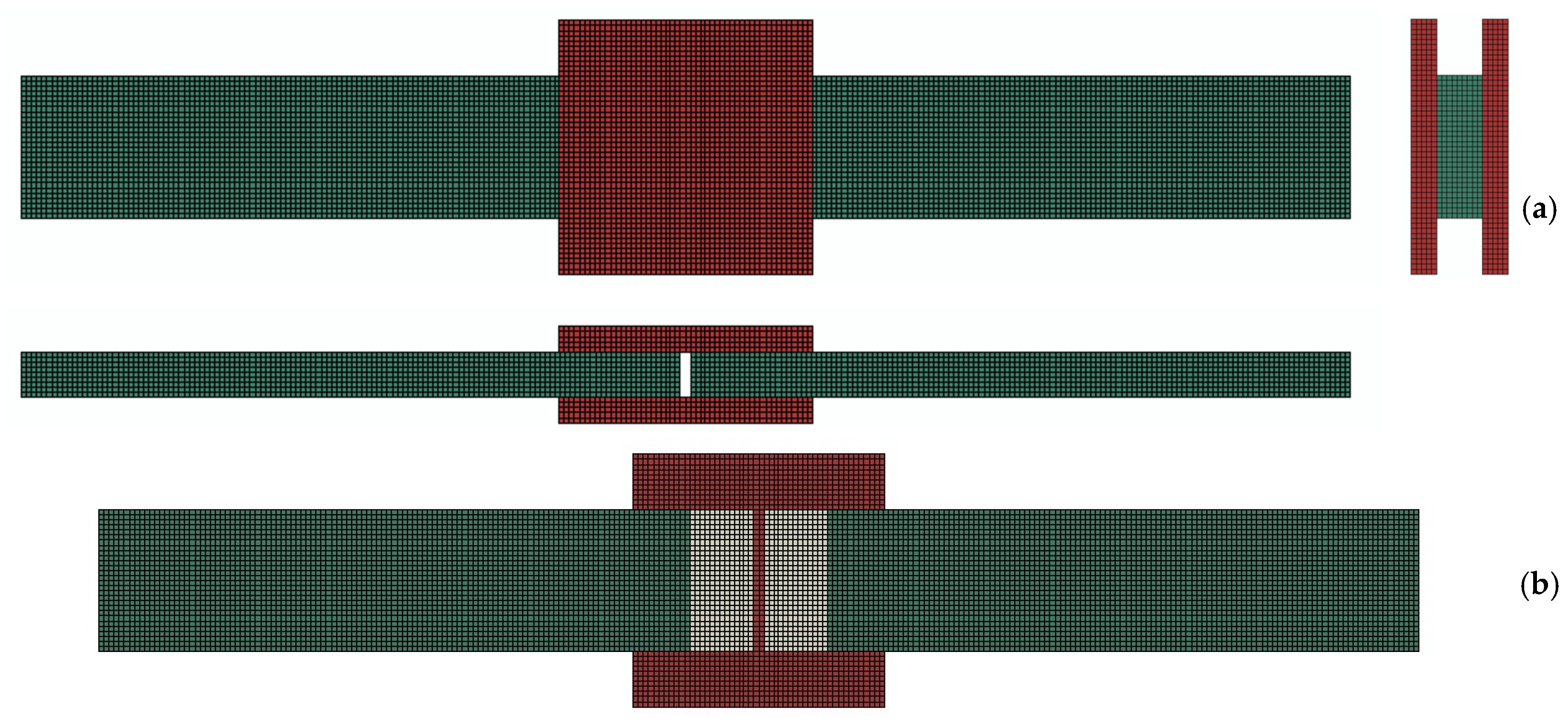

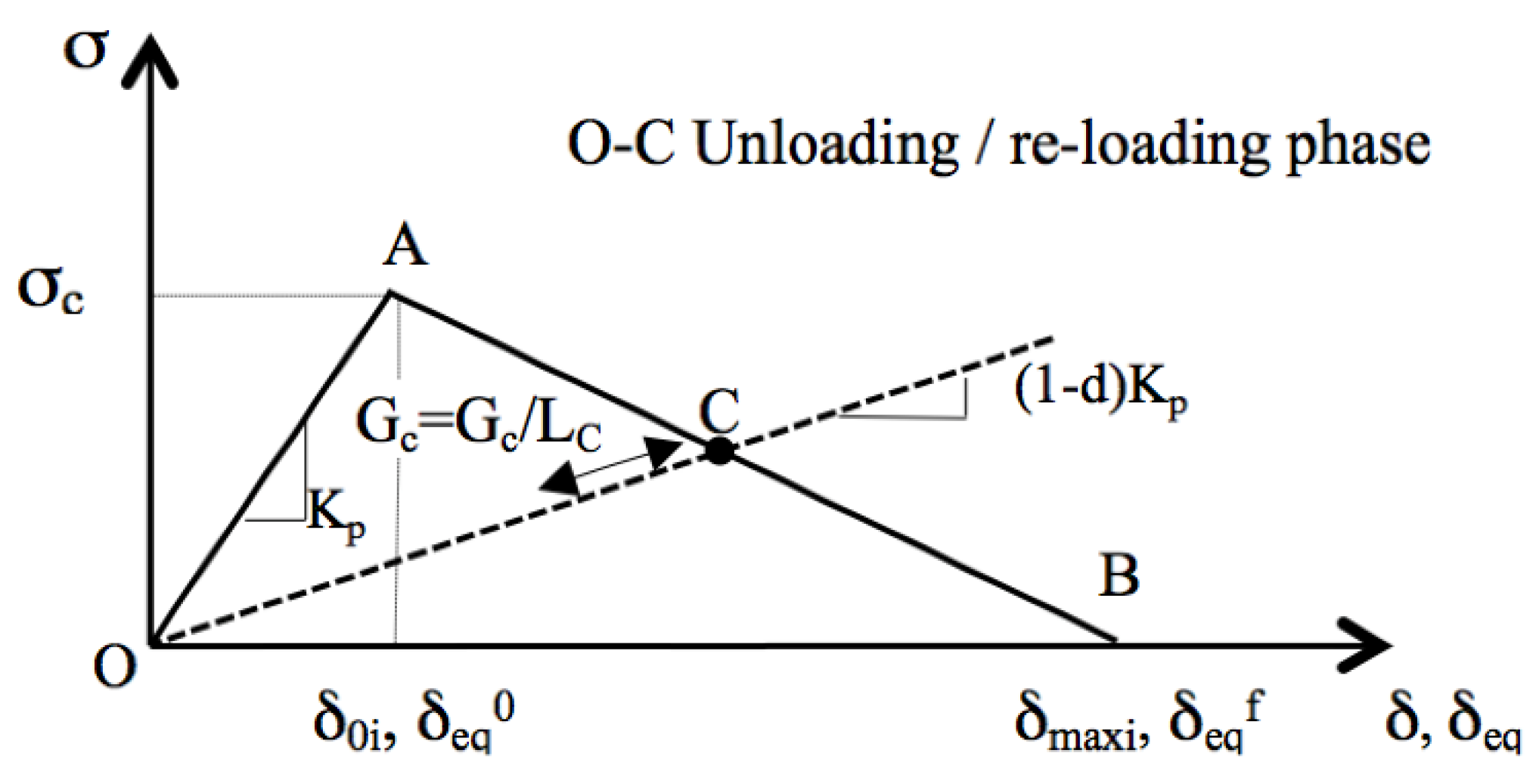

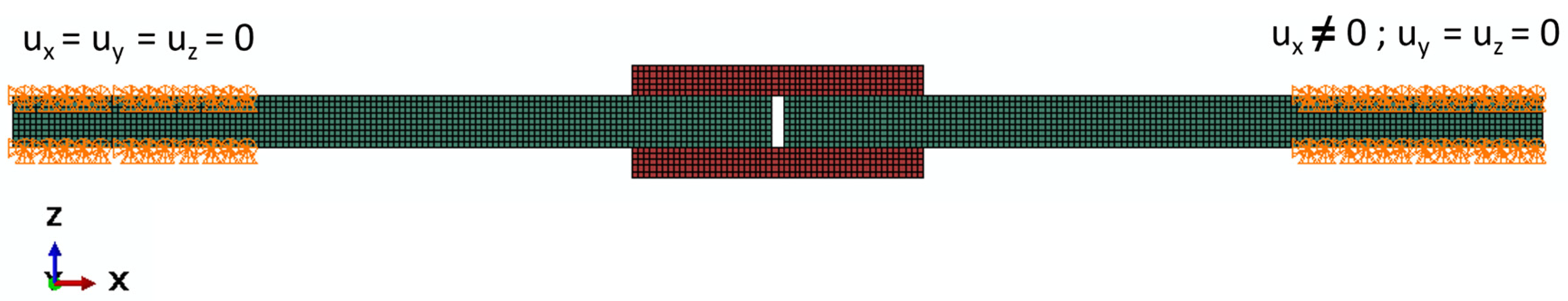

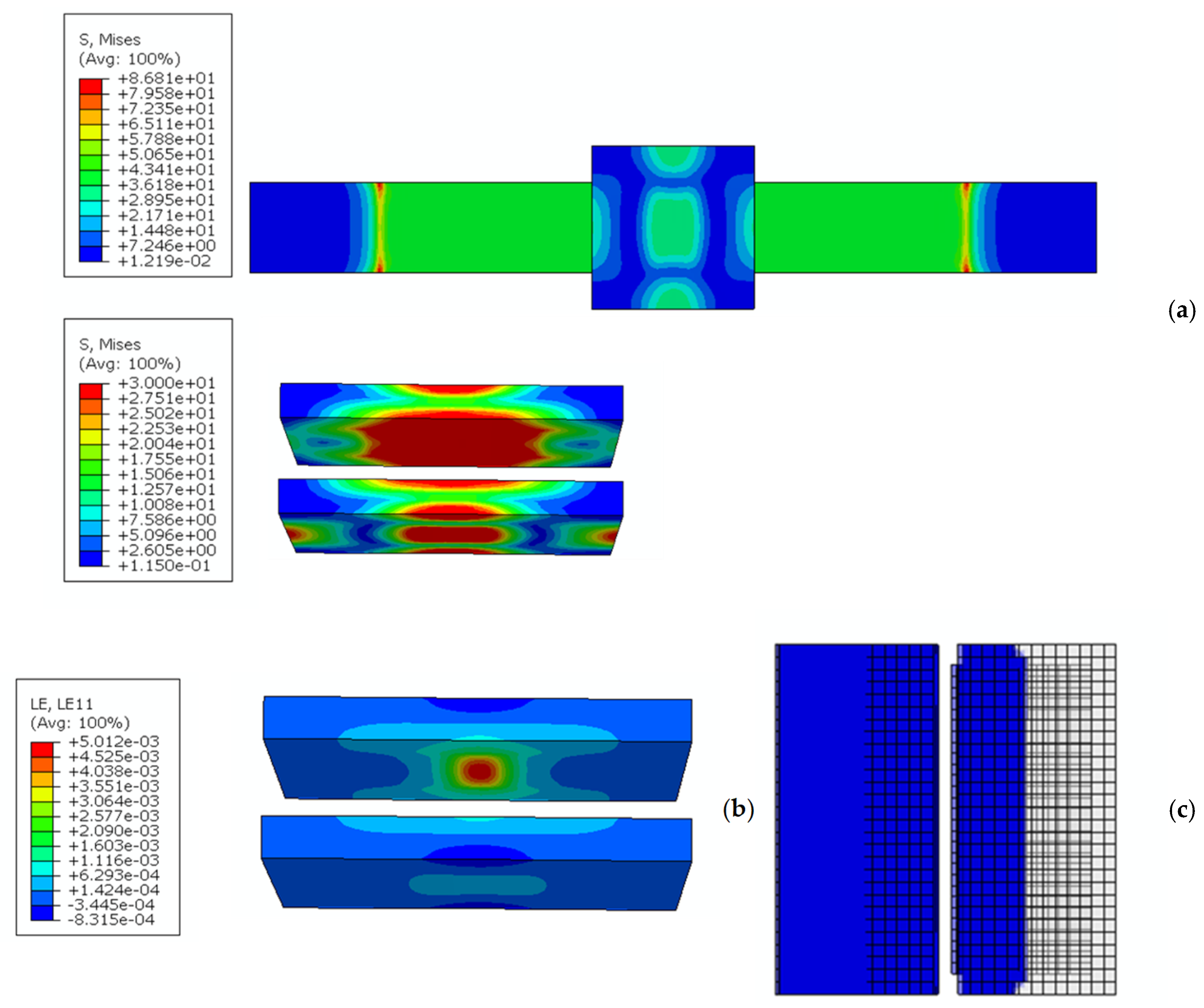

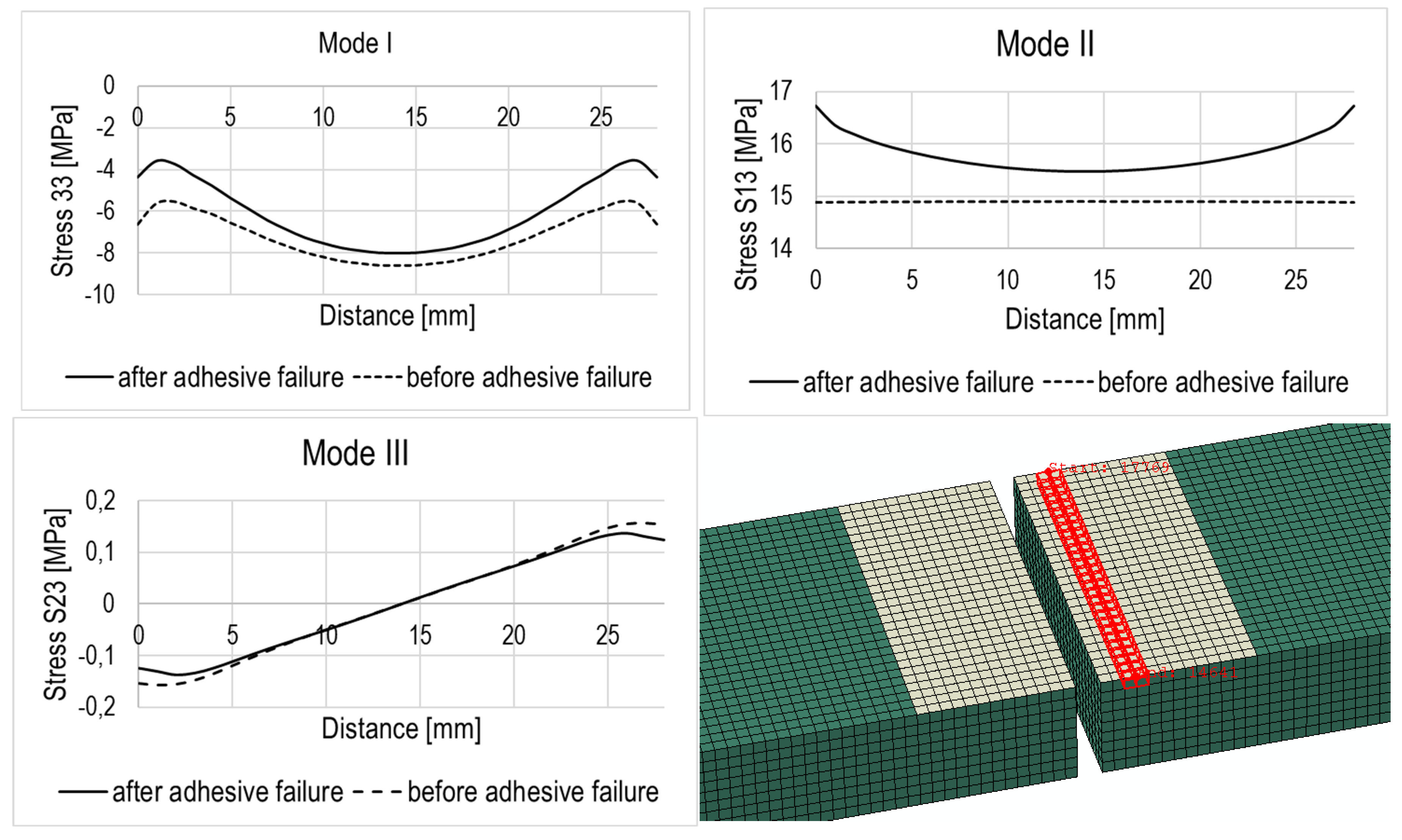

3. FE Model

4. Results and Discussion

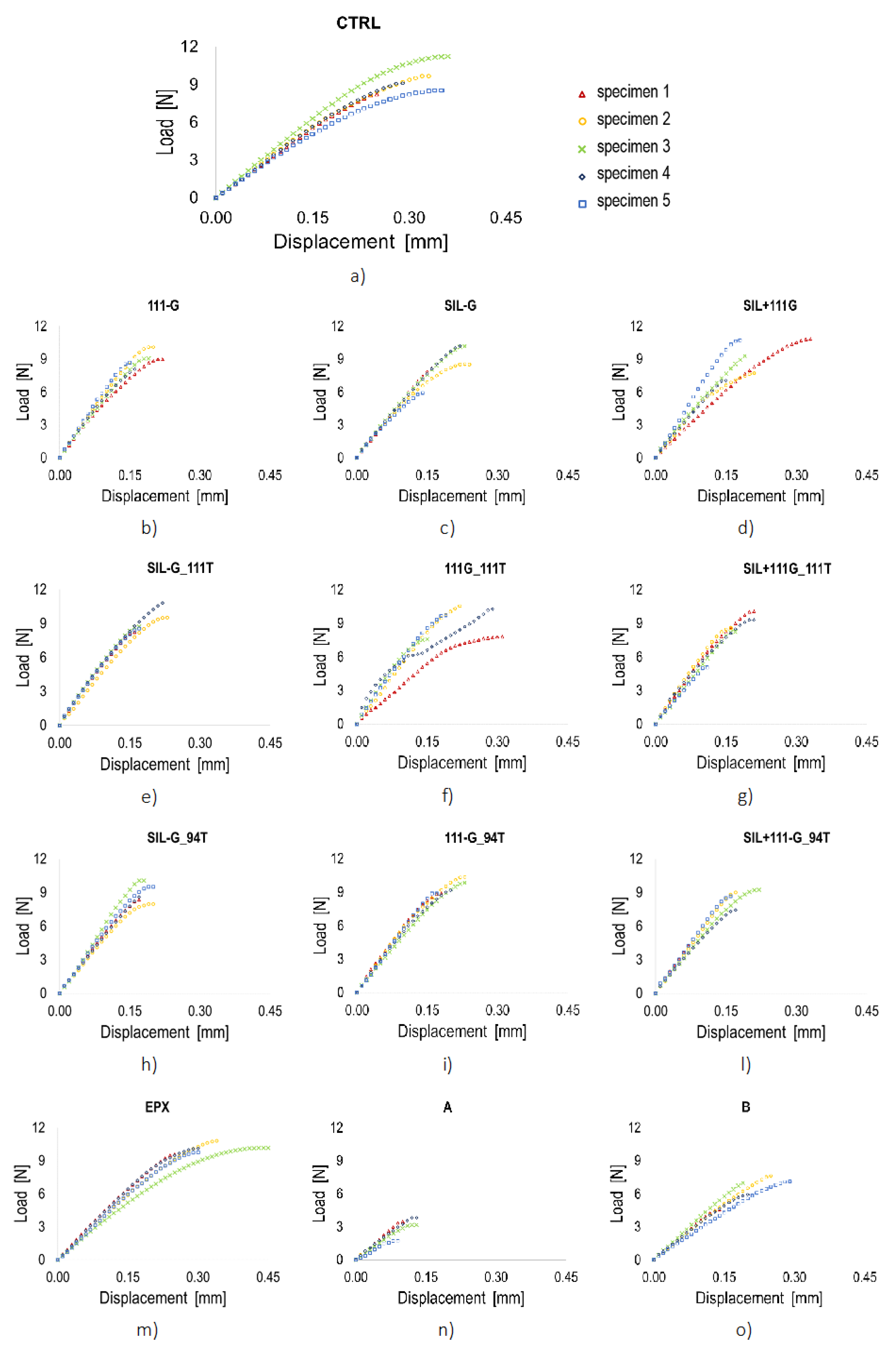

4.1. Experimental Results

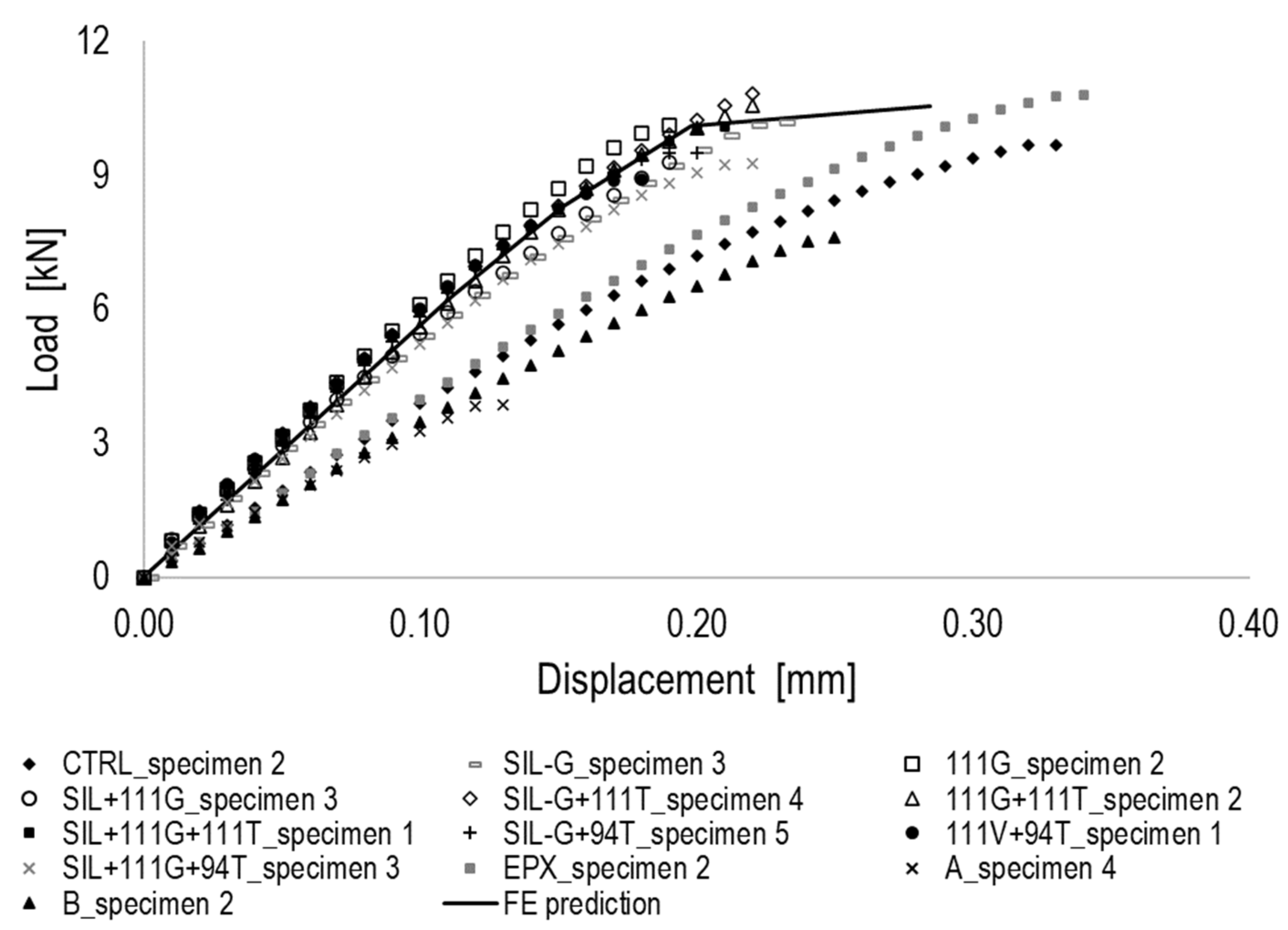

4.2. Numerical Results and Experimental Data Comparison

5. Conclusions

- 1)

- The pre-treatments on the glass and/or timber side of the bonded joint reduce the maximum displacement, shear stress and shear strain. They may also contribute to increase the maximum failure load of the joint, but this behaviour is not observed for all the tested series; in particular, adhesion promoters (111 and 94) seem to have a better effect than moisture-inhibitor (Silane) in this respect. As a consequence of the decrease of the ultimate displacement, all pre-treated series have higher stiffness than the untreated ones. These treatments, in fact, improve surface adhesion at the adherend-adhesive interface, which in turn enhances load transmission between the adherents up to the maximum permissible stress of the glass, before the adhesive failure (AF) occurs. This aspect of stiffness is relevant according to the different fields of application (i.e., depending on the displacements that the joint can bear, a combination is more or less suitable for a specific purpose).

- 2)

- The behaviour of the painted joint strongly depends on the type of paint used on the glass: a paint of the same nature of the adhesive (i.e., epoxy paint) can increase the ultimate load but has no significant effect on the remaining considered parameters (as summarized in Table 8), nor on the type of failure mechanisms. Conversely, the use of an acrylic paint causes a worsening of the overall mechanical behaviour and shifts the collapse mode from glass failure to interface failure.

- 3)

- According to the results of the numerical modelling, it can be concluded that the simulation appears to be more representative of all those series where adhesive promoters are used. This aspect can be addressed to the fact that the usage of adhesive promoters reduces the effects on the joint structural behaviour of the uncertainties affecting all specimens because of the manufacturing process, which cannot be easily included in the modelling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vallée, T.; Tannert, T.; Fecht, S. , “Adhesively bonded connections in the context of timber engineering–A Review,” Journal of Adhesion, vol. 93, no. 4. Taylor and Francis Inc., pp. 257–287, Mar. 21, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Martens, K.; Caspeele, R.; Belis, J. , “Development of composite glass beams - A review,” Engineering Structures, vol. 101. Elsevier Ltd., pp. 1–15, Oct. 05, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tannert, T.; Gerber, A.; Vallee, T., “Hybrid adhesively bonded timber-concrete-composite floors,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 97, no. November 2019, p. 102490, 2020. [CrossRef]

- MacHalická, K.; Horčičková, I.; Eliášová, M. , “Shear adhesive connections for glass structures,” IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng, vol. 96, no. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Freytag, B. , “Glass-concrete composite technology,” Structural Engineering International: Journal of the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering (IABSE), vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 111–117, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Speranzini, E.; Agnetti, S. , “Strengthening of glass beams with steel reinforced polymer (SRP),” Compos B Eng, vol. 67, pp. 280–289, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.; Werner, F. , “GLASS-PLASTIC HYBRID CONSTRUCTION,” 2006.

- Marchione, F. , “Stress distribution in double-lap adhesive joints: Effect of adherend reinforcement layer,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 105, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F. , “Effect of hollow adherends on stress peak reduction in single-lap adhesive joints: FE and analytical analysis,” Journal of Adhesion, vol. 98, no. 6, pp. 656–676, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.D.; Peppiatt, N.A. , “Stress analysis of adhesive-bonded lap joints,” Journal of strain analysis, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 158–196, 1974.

- Machalická, K.; Vokáč, M.; Eliášová, M. , “Influence of artificial aging on structural adhesive connections for façade applications,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 83, no. March, pp. 168–177, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jasiūnas, L.; Peck, G.; Bridžiuvienė, D.; Miknius, L. , “Mechanical, thermal properties and stability of high renewable content liquefied residual biomass derived bio-polyurethane wood adhesives,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 101, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, M.; Czech, Z.; Mozelewska, K.; Nowak, M. , “Influence of thermal reactive crosslinking agents on the tack, peel adhesion, and shear strength of acrylic pressure-sensitive adhesives,” Polym Test, vol. 90, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Banea, M.D.; Da Silva, L.F.M.; Campilho, R.D.S.G., “Effect of temperature on the shear strength of aluminium single lap bonded joints for high temperature applications,” J Adhes Sci Technol, vol. 28, no. 14–15, pp. 1367–1381, July 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pethrick, R.A. , “Design and ageing of adhesives for structural adhesive bonding – A review,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, vol. 229, no. 5, pp. 349–379, 2015.

- Jeevi, G.; Nayak, S.K.; Kader, M.A. , “Review on adhesive joints and their application in hybrid composite structures,” Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, vol. 33, no. 14. Taylor and Francis Ltd., pp. 1497–1520, Jul. 18, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pequeno, J.M.; Cruz, P.J.S. , “Structural Timber-Glass Linear System: Characterization & Architectural Potentialities,” Glass Performance Days 2009 - Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, pp. 344–348, 2009.

- Erik. Eriksson, J & Ludvigsson, M & Dorn, Michael & Enquist, Bertil & Serrano, “Load bearing timber glass composites – A WoodWisdom-Net project for innovative building system,” in COST Action TU0905 Mid-term Conference on Structural Glass, 2013, p. 269. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P.J.S.; Pequeno, J. , “Timber-Glass Composite Beams: Mechanical Behaviour & Architectural Solutions,” Challenging Glass, pp. 439–448, 2008.

- Vallee, T.; Grunwald, C.; Milchert, L.; Fecht, S. , “Design and dimensioning of a complex timber-glass hybrid structure: the IFAM pedestrian bridge,” Glass Structures & Engineering, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 3–18, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Blyberg, L.; et al. , “Glass, timber and adhesive joints – Innovative load bearing building components,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 55, pp. 470–478, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F.; Agliata, R.; Munafò, P. , “Application of adhesive technology to a new type of glazed panel for curtain walls with an integrated frame,” TEMA, vol. 8, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Blyberg, L.; Serrano, E.; Enquist, B.; Sterley, M. , “Adhesive joints for structural timber/glass applications: Experimental testing and evaluation methods,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 35, pp. 76–87, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Kadela, M.; Hulimka, J. , “Numerical Investigation of Structural Behaviour of Timber-Glass Composite Beams,” Procedia Eng, vol. 161, pp. 990–1000, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rudawska, A. , “Adhesive joint strength of hybrid assemblies: Titanium sheet-composites and aluminium sheet-compositesExperimental and numerical verification,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 574–582, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, B.; et al. , “Durability of adhesive glass-metal connections for structural applications,” Eng Struct, vol. 126, pp. 237–251, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.; Correia, J.R.; Firmo, J.P.; Cabral-Fonseca, S.; Gonilha, J. , “Effects of thermal cycles on adhesively bonded joints between pultruded GFRP adherends,” Compos Struct, vol. 202, no. February, pp. 518–529, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Beber, V.C.; Schweer, J.; Brede, M.; Mayer, B. , “An experimental investigation of the fatigue damage behaviour of adhesively bonded joints under the combined effect of variable amplitude stress and temperature variation,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 83, no. March, pp. 41–49, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Wan, H.; Carlson, B.E.; Lin, J.; Sun, C. , “Application of laser ablation in adhesive bonding of metallic materials: A review,” Opt Laser Technol, vol. 128, no. February, p. 106188, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Žigon, J.; et al. , “Enhancement of strength of adhesive bond between wood and metal using atmospheric plasma treatment,” Cellulose, vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 6411–6424, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Worpenberg, C.; Stiesch, M.; Eisenburger, M.; Breidenstein, B.; Busemann, S.; Greuling, A. , “The effect of surface treatments on the adhesive bond in all-ceramic dental crowns using four-point bending and dynamic loading tests,” J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, vol. 139, p. 105686, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. , “Effects of surface treatment and adhesive thickness on the shear strength of precision bonded joints,” Polym Test, vol. 94, p. 107063, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; et al. , “Laser surface treatment to enhance the adhesive bonding between steel and CFRP: Effect of laser spot overlapping and pulse fluence,” Opt Laser Technol, vol. 159, p. 109002, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), CNR-DT 210/2013 - Istruzioni per la Progettazione, l’Esecuzione ed il Controllo di Costruzioni con Elementi Strutturali di Vetro. Italy, 2013.

- INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO, 13061-6 Physical and mechanical properties of wood — Test methods for small clear wood specimens — Part 6: Determination of ultimate tensile stress parallel to grain. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO, 2014.

- Marchione, F.; Munafò, P. , “Influence of high temperature exposure on the mechanical performance of double-lap adhesive joints between glass and aluminium adherends,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 299, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F.; Chiappini, G.; Munafò, P. , “Effect of temperature and relative humidity on the shear performance of double-lap adhesive joints between steel and glass adherends,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 45, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F.; Munafò, P. , “Effect of thermal aging on the mechanical performance of timber-timber single-lap adhesive joints,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 108, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marchione, F.; Munafò, P. , “Experimental investigation on timber-glass double-lap adhesive joints reinforced with nylon fabric,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 275, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- 3MTM, “Scotch-WeldTMStructural Adhesive 7240 B/A FR Preliminary Product Data Sheet,” 2018.

- Marchione, F.; Munafò, P. , “Experimental investigation on timber-glass double-lap adhesive joints,” Int J Adhes Adhes, vol. 106, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM, D3528-96 Standard Test Method for Strength Properties of Double Lap Shear Adhesive Joints by Tension Loading. USA, 2016.

- ISO, 4587:2003 Adhesives — Determination of tensile lap-shear strength of rigid-to-rigid bonded assemblies. 2003.

- ASTM, D5573 Standard Practice for Classifying Failure Modes in Fiber-Reinforced-Plastic (FRP) Joints 1. USA, 1999.

- Lamanna, G.; Perrella, M.; Opran, C.G. , “Numerical and Experimental Investigation on the Influence of Tightening in a Hybrid Single Lap Joint” Macromolecular Symposia vol. 396(1), 2100010. 2021.

- Lamanna, G.; Opran, C.G. , “Numerical Characterization of Pretensioning of a Hybrid Joint Under Longitudinal Load, Macromolecular Symposia vol. 396(1), 2100009. 2021.

- Lamanna, G.; Ion, S.M.; Opran, C.G., “Flexural Effects Evaluation on Hybrid Joints Under Uniaxial Tensile Load” Macromolecular Symposia, 396(1), 2100007. Vol. 2021.

- Caputo, F.; Lamanna, G.; Soprano, A. , “Effects of tolerances on the structural behavior of a bolted hybrid joint”, Key Engineering Materials vol. 488-489, pp. 565–568. 2012.

- Abaqus/CAE User Manual v. 2021 - Dassault Systèmes.

- Caputo, F.; De Luca, A.; Lamanna, G.; Borrelli, R.; Mercurio, U. , “Numerical study for the structural analysis of composite laminates subjected to low velocity impact”, Composites: Part B vol. 67, 296–302. 2014.

| Glass [34] | Beechwood [35] | |||

| Thermal coeff. of expansion | Young Modulus | Tensile strength | Young Modulus | Tensile strength |

| α (°C-1) | E (GPa) | σR (MPa) | E (GPa) | σR (MPa) |

| 9 × 10-6 | 75 | 30 | 1.5 | 90 |

| Chemical nature | two-part | toughened epoxy base + modified amine accelerator | |

| Viscosity | - | thixotropic | |

| Work life | Wl | (min) | 45 |

| Application temperature | At | (°C) | 15÷30 |

| Glass transition temperature | Tg | (°C) | 66.87 |

| Service temperature | St | (°C) | -40÷80 |

| Shear strength | τ | (MPa) | 6.2 – 24.3* |

| Young Modulus in compression | Et | (MPa) | 3500-4000 |

| Use | - | semi-structural | |

| Epoxy-based | Acrylic-based - type A | Acrylic-based – type B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | silver | black | black |

| Type | 2-compounds pearlescent paint for glass | Bilayer 100% solvent-based high coverage | High Solids, solvent-based 2-component, satin finish |

| Composition | 1 part paint + 0.6 diluent* + 0.45 catalyst** | 1 part paint + 0.5 diluent*** | 1 part paint + 0.2 catalyst**** |

| Auxiliary components | * DT 810 Epoxy Thinner by Visa Colors ** AM 85 Glossy Hardener |

*** Disolvente acrìlico RU RAC medio | **** Catalizador DCP9156 high adherence by Racing colors (included with the paint) |

| Silane | 111 | 94 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main ingredient | (% by Weight) | isopropyl alcohol (80 – 95)* |

propan-2-ol (98 – 100) |

cyclohexane (30 – 60)* |

| Boiling point | (°C) | 82.2 | 82.4 | 76.7 |

| Flashpoint | (°C) | 11.7 | 11 | -17.2 |

| Density | (g/ml) | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| Vapor Pressure | (mmHg) | 43 (at 25 ºC) | 330 (at 20 ºC) | 68 (at 20 ºC) |

| Relative Vapor Density | 2.07 | 2.1 | no data available | |

| CTRL | Untreated |

| SIL-G | Silane on the glass side |

| 111G | Primer 111 on the glass side |

| SIL+111G | Silane + Primer 111 on the glass side |

| SIL-G_111T | Silane on the glass side and Primer 111 on the timber side |

| 111G_111T | Primer 111 on the glass side and Primer 111 on the timber side |

| SIL+111G_111T | Silane + Primer 111 on the glass side and Primer 111 on the timber side |

| SIL-G_94T | Silane on the glass side and Primer 94 on the timber side |

| 111G_94T | Primer 111 on the glass side and Primer 94 on the timber side |

| SIL+111G_94T | Silane + Primer 111 on the glass side and Primer 94 on the timber side |

| EPX | Glass treated with Epoxy paint |

| A | Glass treated with Acrylic paint – type A |

| B | Glass treated with Acrylic paint – type B |

| Longitudinal Young’s Modulus | En | [MPa] | 4000 |

| Transversal Young’s Moduli | Es=Et | [MPa] | 1350 |

| Nominal stress I mode | [MPa] | 42 | |

| Nominal stress II mode | [MPa] | 15 | |

| Nominal stress III mode | [MPa] | 15 | |

| Critical fracture energy, mode I | Jm-2 | 380 | |

| Critical fracture energy, mode II | Jm-2 | 190 | |

| Critical fracture energy, mode III | Jm-2 | 190 |

| Series | Specimen 1 | Specimen 2 | Specimen 3 | Specimen 4 | Specimen 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | SB + TLC (G) | SB | SB + AF (G) + CF + LTT | SB | SB + CF + LTT |

| SIL-G | SB | SB + TT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + TT | TT + LTT + TLC (T/G) |

| 111G | SB + TT + TLC (G) | SB + TLC (T/G) + LTT | SB + TT + TLC (G) | SB | SB + TT |

| SIL+111G | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB | SB | SB | SB + LTT + TLC (T) |

| SIL-G_111T | SB | SB + TLC (T) + LTT+ AF (G) | CF + LTT + TLC (T/G) | SB | SB + TT + LTT + TLC (T) |

| 111G_111T | SB + TT | AF (G) + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB | SB + TLC (T) + LTT |

| SIL+111G_111T | TT + LTT | SB + TT | SB + TT | LTT | SB + TLC (T) + LTT |

| SIL-G_94T | SB | TLC (T) + LTT | SB + TT + TLC (T) | SB | SB + TLC (T) + LTT |

| 111G_94T | TLC (G) + LTT | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + TT |

| SIL+111G_94T | SB + TLC (T) | SB + TT + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TT + TLC (T) | SB + TLC (T) + LTT | SB + LTT + TLC (T) |

| EPX | SB | SB | SB + CF + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) | SB + LTT + TLC (T) |

| A | AF (G) + TLC (G) | AF (G) + TLC (G) | AF (G) | AF (G) | AF (G) |

| B | TLC (G) + AF (G) | TLC (G) + SB + AF (G) | TLC (G) + AF (G) | TLC (G) + AF (G) | TLC (G) + AF (G) |

| Series | Load max | Displ max | τmax | γmax | k | Failure Modes* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kN) | (mm) | (MPa) | (-) | (kN/mm) | ||

| CTRL | 8.90 ± 0.64 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 7.26 ± 0.50 | 1.09 ± 0.16 | 30.39 ± 3.66 | 3 MF + 2 SB |

| SIL-G | 8.61 ± 1.06 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 6.67 ± 0.83 | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 44.62 ± 5.97 | 4 MF + 1 SB |

| 111G | 9.01 ± 0.73 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 6.98 ± 0.57 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 50.73 ± 5.97 | 4 MF + 1 SB |

| SIL+111G | 9.13 ± 1.47 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 7.07 ± 1.14 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 46.21 ± 10.89 | 3 SB + 2 MF |

| SIL-G_111T | 9.18 ± 1.04 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 7.11 ± 0.80 | 0.58 ± 0.09 | 49.88 ± 4.48 | 3 MF + 2 SB |

| 111G_111T | 9.20 ± 1.41 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 7.13 ± 1.09 | 0.66 ± 0.21 | 43.19 ± 11.77 | 4 MF + 1 SB |

| SIL+111G_111T | 9.06 ± 0.82 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 7.02 ± 0.64 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 50.27 ± 3.02 | 4 MF + 1 LTT |

| SIL-G_94T | 8.91 ± 0.87 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 6.90 ± 0.67 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 50.18 ± 6.09 | 3 MF + 2 SB |

| 111G_94T | 9.44 ± 0.65 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 7.32 ± 0.50 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 48.50 ± 4.85 | 5 MF |

| SIL+111G_94T | 8.59 ± 0.81 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 6.66 ± 0.63 | 0.63 ± 0.10 | 48.46 ± 6.14 | 5 MF |

| EPX | 10.10 ± 0.47 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 7.82 ± 0.36 | 1.17 ± 0.30 | 34.87 ± 3.20 | 3 MF + 2 SB |

| A | 2.72 ± 1.12 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 2.11 ± 0.87 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | 30.06 ± 6.21 | 3 AF (G) + 2 MF |

| B | 6.46 ± 0.72 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 5.01 ± 0.55 | 0.70 ± 0.16 | 31.45 ± 4.75 | 5 MF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).