Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the F3 Biparental Population

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mean, Ranks and Heritabilities of the F3 Population

3.2. Genetic and Phenotypic Correlations

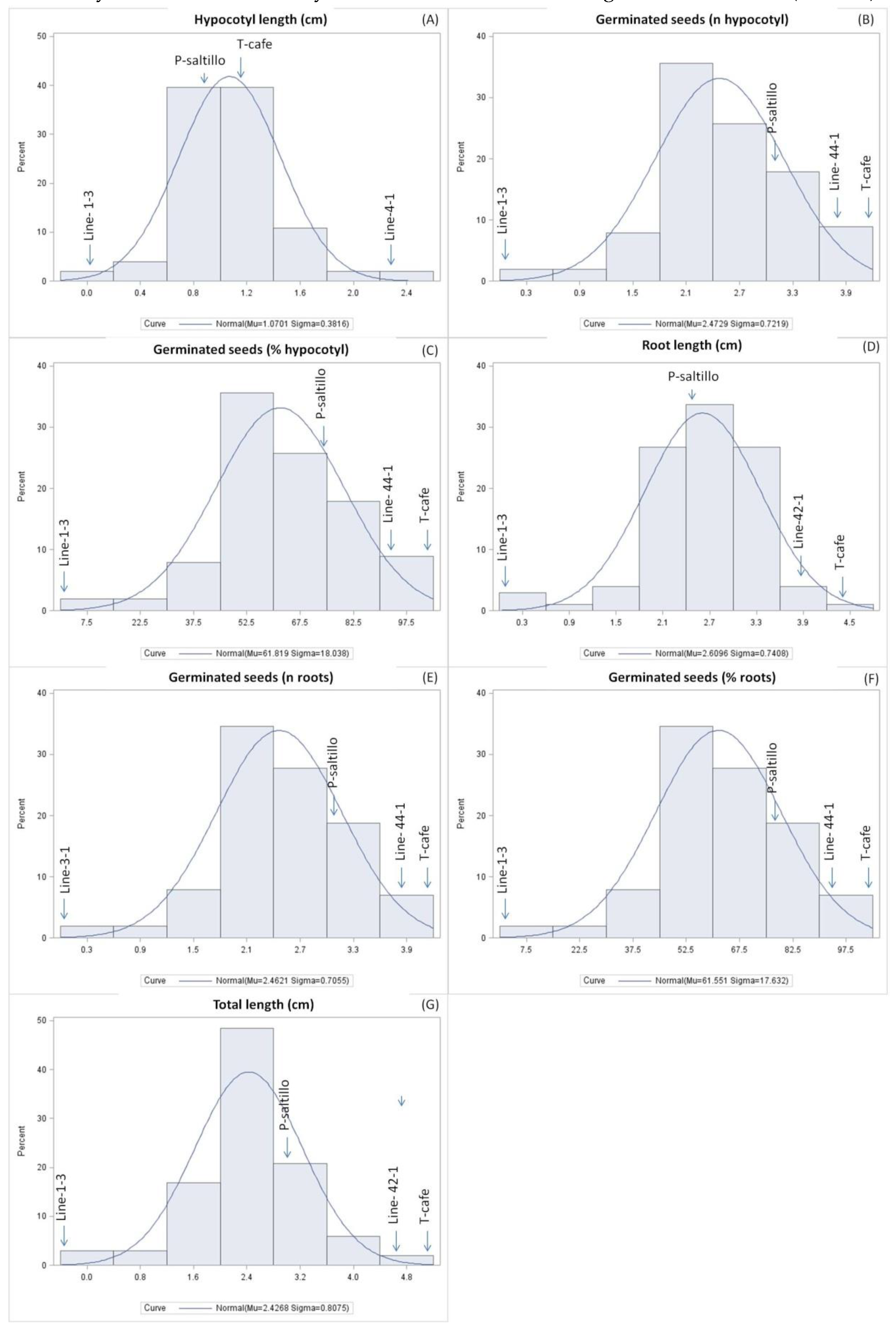

3.3. Distributions Analysis

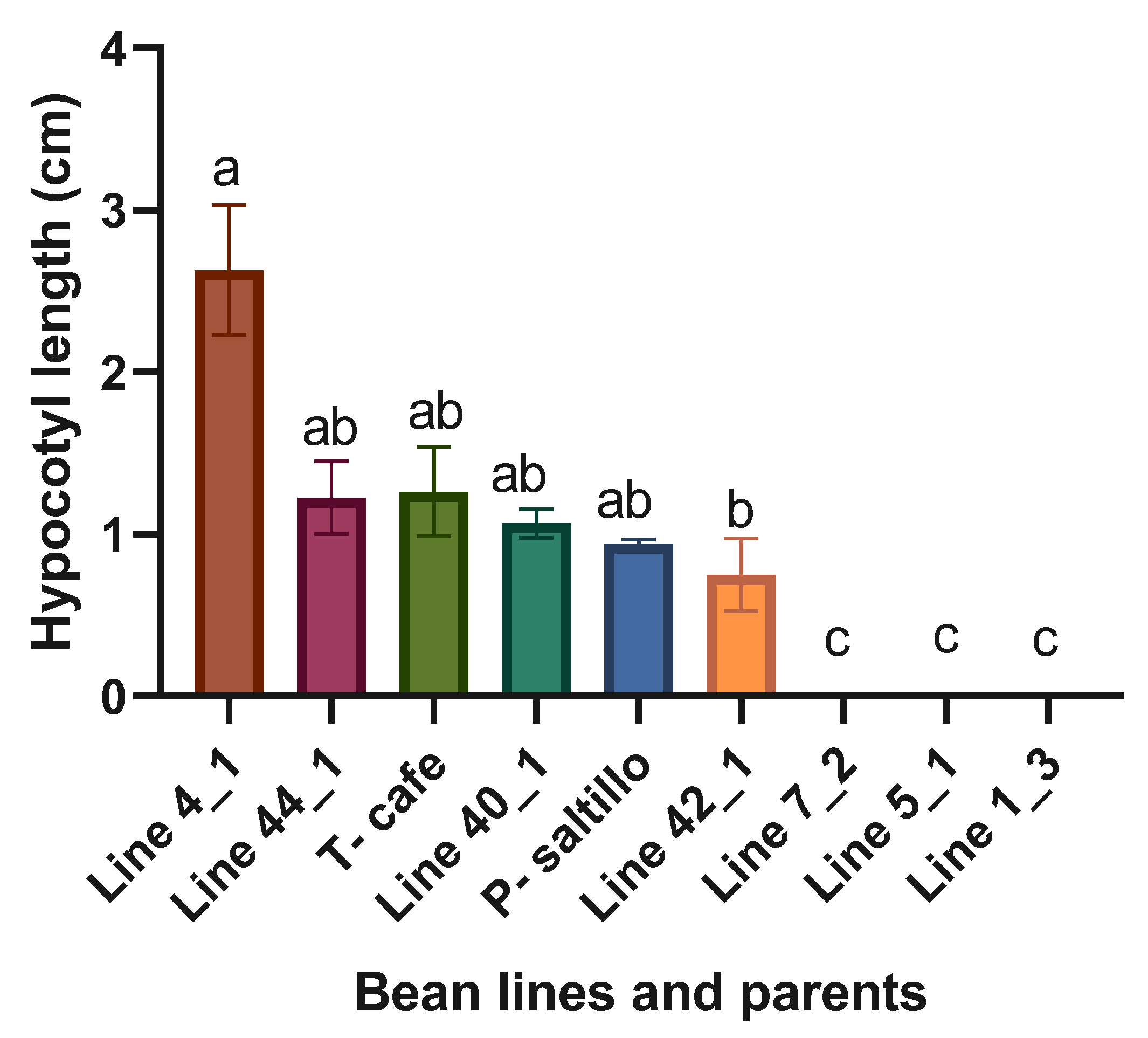

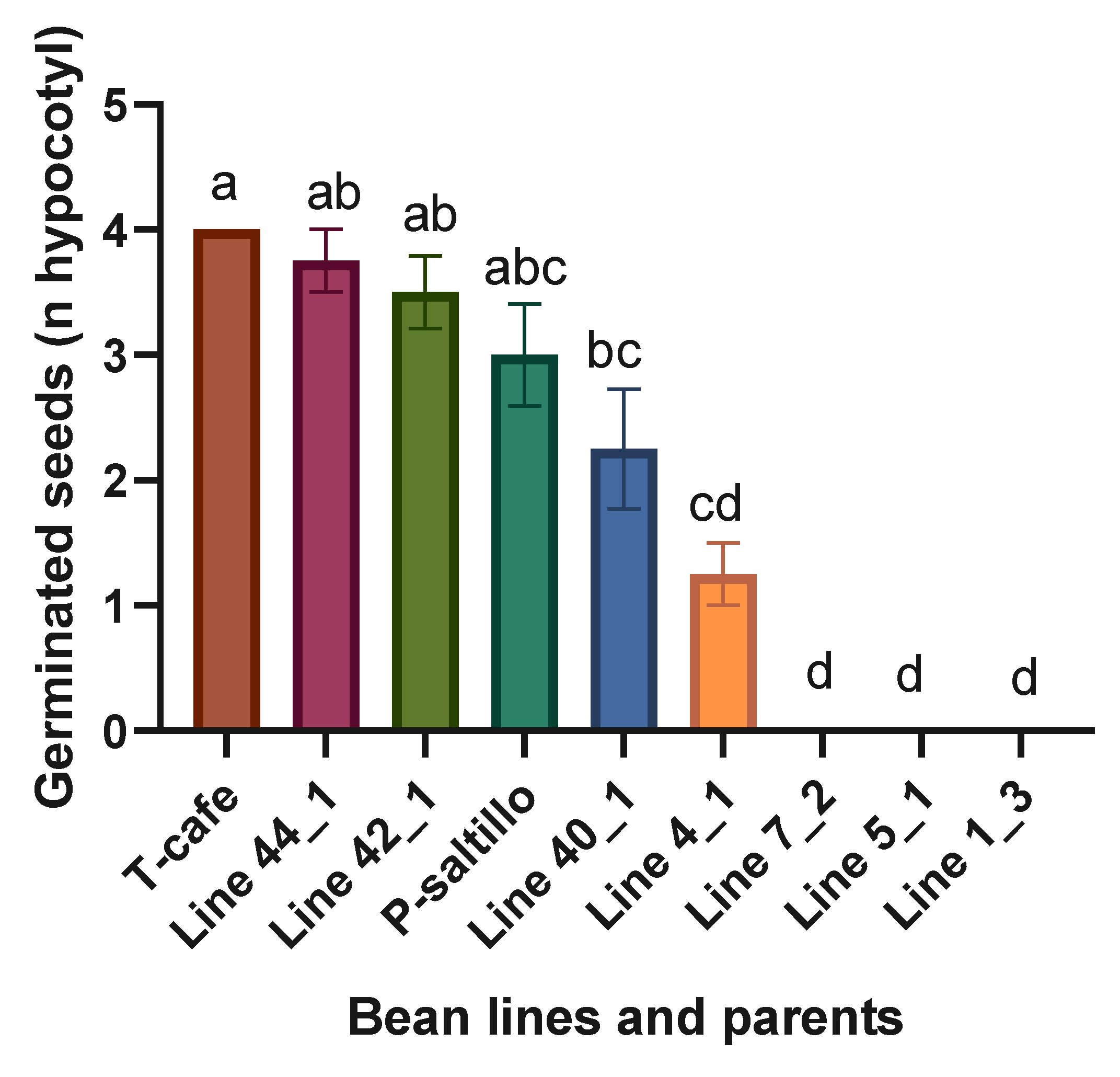

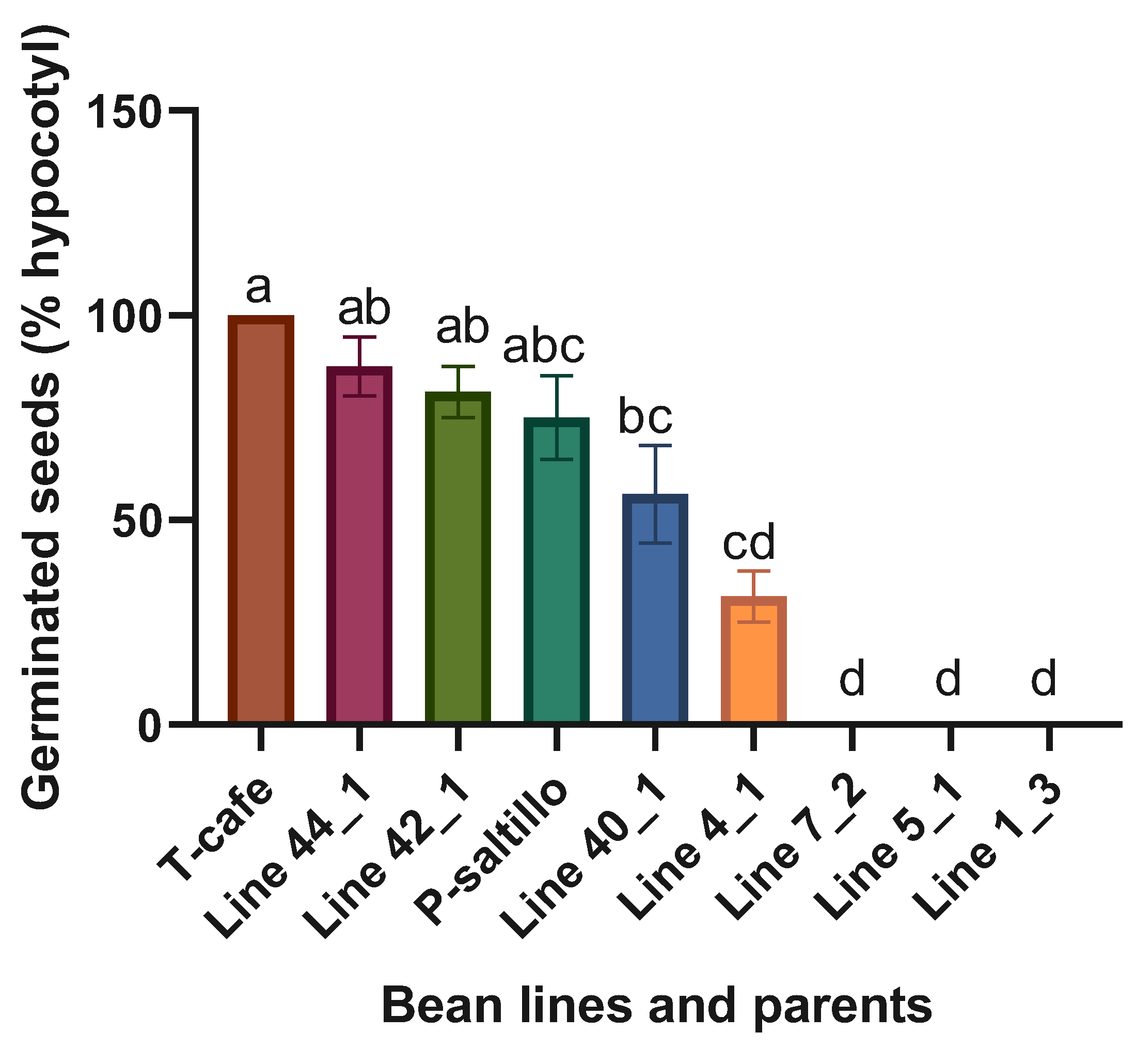

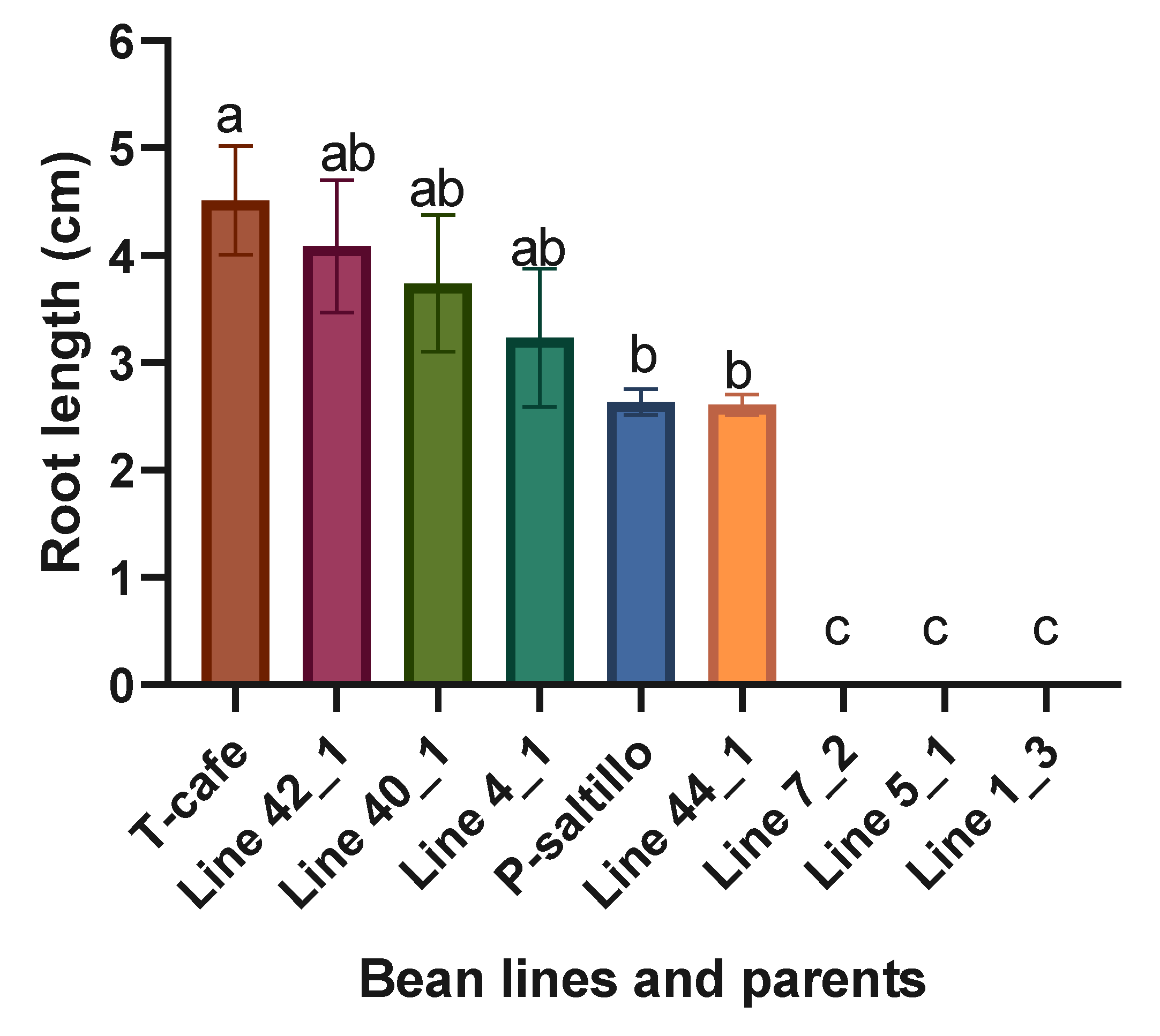

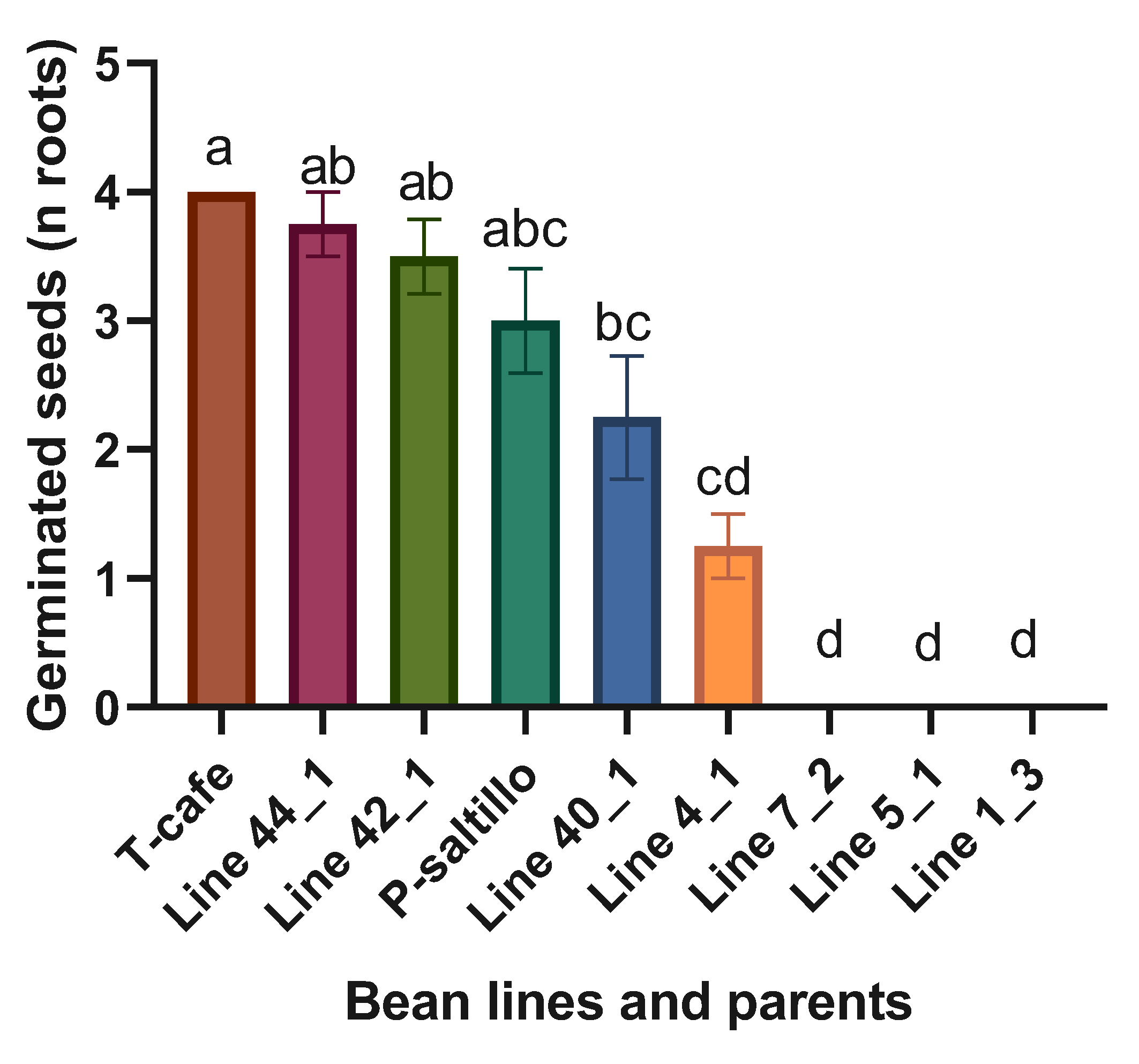

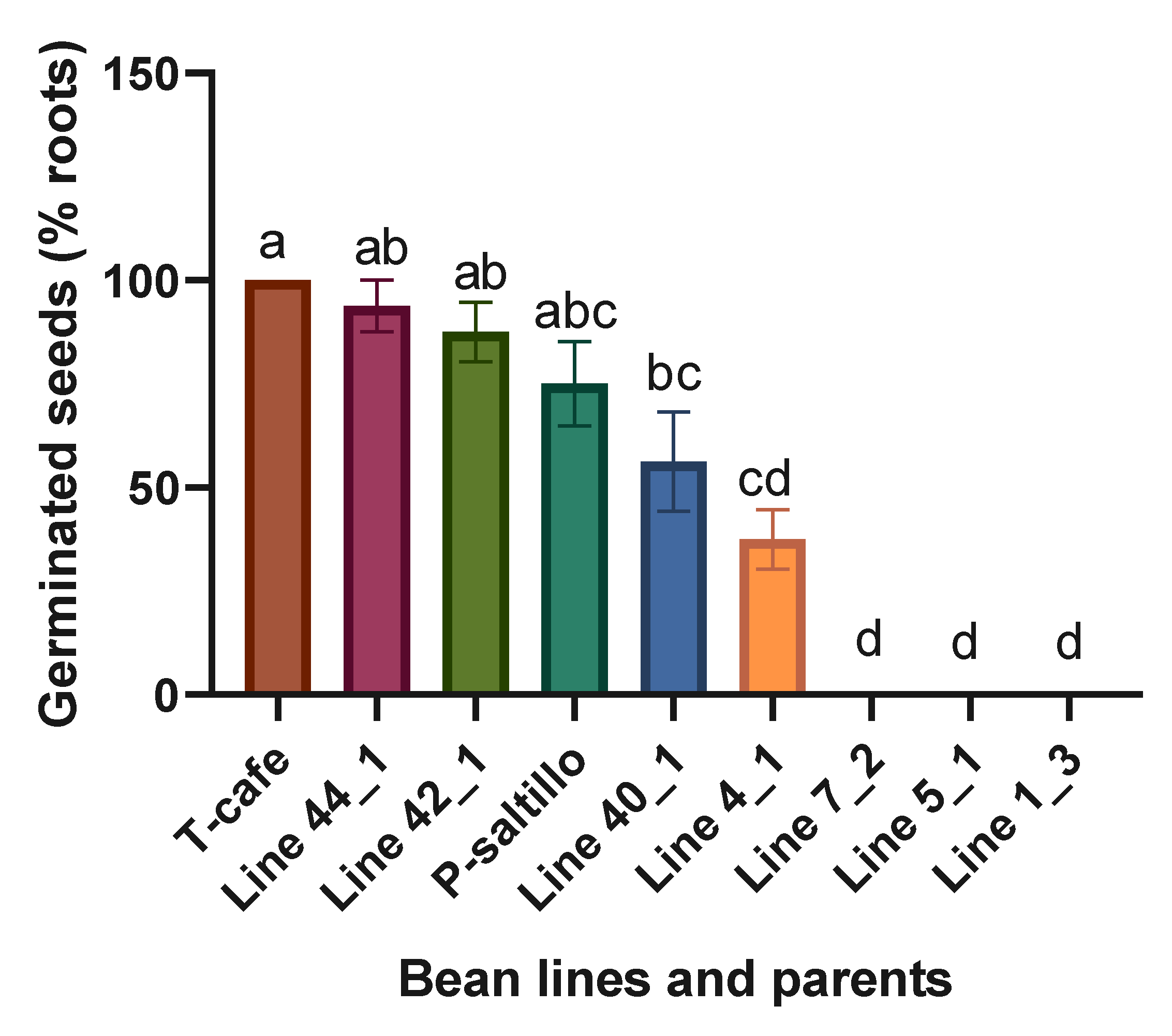

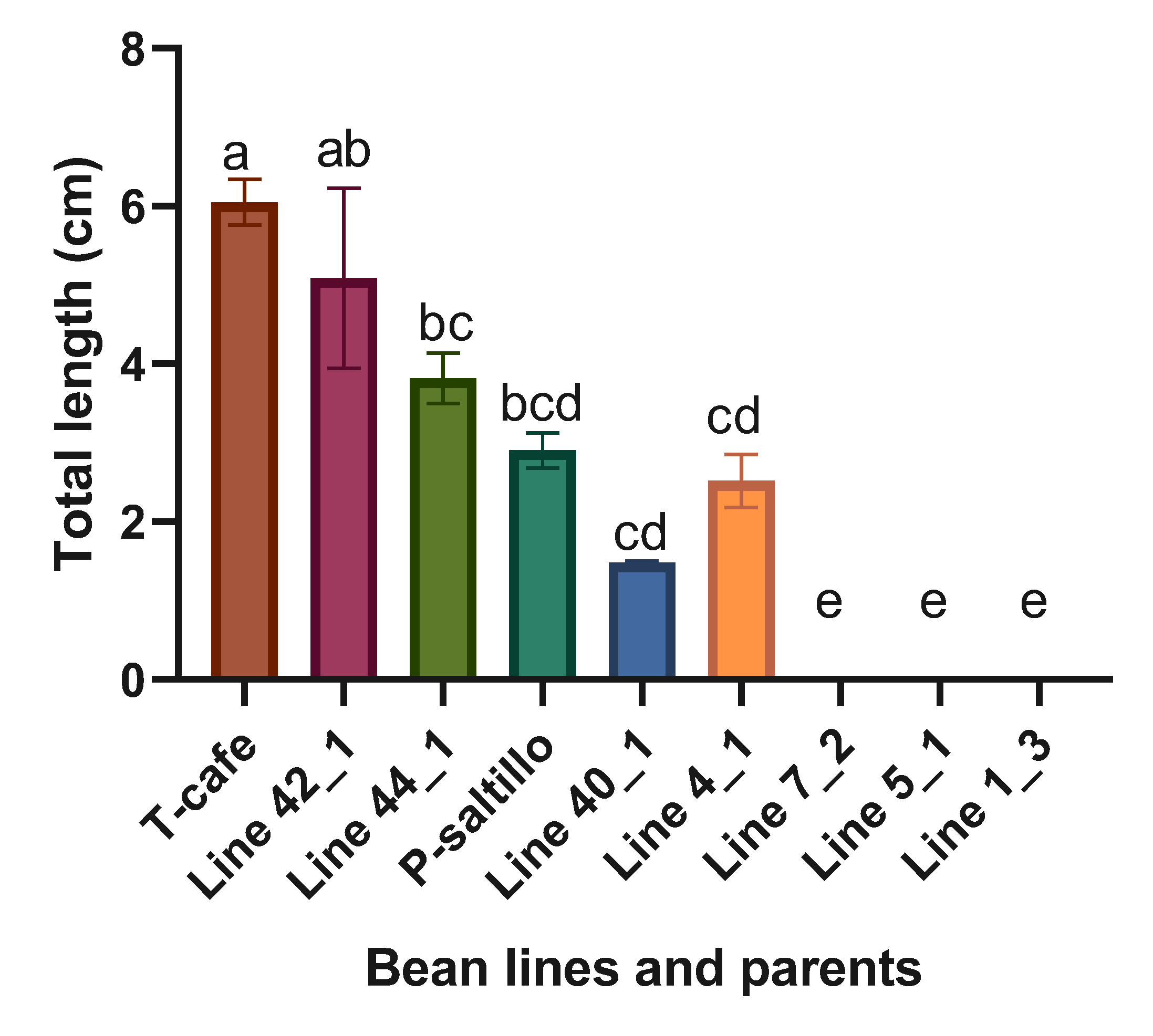

3.4. Mean Comparison of the 4 Tolerant, the 3 Susceptible F3 and 2 Parents for Drought Tolerance

4. Discussion

4.1. Mean, Ranks and Heritabilities of the F3 Population

4.2. Genetic and Phenotypic Correlations

4.3. Distributions Analysis

4.4. Mean Comparison of the 4 Tolerant, the 3 Susceptible F3 and 2 Parents for Drought Tolerance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, I. , et al., Can tepary bean be a model for improvement of drought resistance in common bean? African Crop Science Journal 2013, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Didinger, C. , et al., Nutrition and human health benefits of dry beans and other pulses. Dry Beans and pulses: Production, processing, and Nutrition 2022, 481-504.

- Vidak, M. , et al., New Age of Common Bean, in Production and Utilization of Legumes-Progress and Prospects. 2023, IntechOpen.

- Khatun, M. , et al., Drought stress in grain legumes: Effects, tolerance mechanisms and management. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z. , et al., Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Science China Life Sciences 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H., Y. Zhao, and J.-K. Zhu, Thriving under stress: how plants balance growth and the stress response. Developmental Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , et al., Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nature Reviews Genetics 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.N. , et al., Epigenetic regulation in plant abiotic stress responses. Journal of integrative plant biology 2020, 62, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán, H. and S.P. Singh, Comparison of sources and lines selected for drought resistance in common bean. Crop science 2002, 42, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Reinoso, A.D., G. A. Ligarreto-Moreno, and H. Restrepo-Díaz, Evaluation of drought indices to identify tolerant genotypes in common bean bush (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2020, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polania, J. , et al., Shoot and root traits contribute to drought resistance in recombinant inbred lines of MD 23–24× SEA 5 of common bean. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, A. and E. Van Volkenburgh, Sink strength maintenance underlies drought tolerance in common bean. Plants, 10 (3), 489. 2021.

- Sofi, P. , et al., Integrating root architecture and physiological approaches for improving drought tolerance in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Physiology Reports 2021, 26, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy Androcioli, L. , et al., Effect of water deficit on morphoagronomic and physiological traits of common bean genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. Water 2020, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, M. and S.P. Wani, Rhizobacterial-plant interactions: strategies ensuring plant growth promotion under drought and salinity stress. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2016, 231, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Patel Priyanka, J. , et al., Rhizospheric microflora: a natural alleviator of drought stress in agricultural crops. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management: Volume 1: Rhizobacteria in Abiotic Stress Management 2019, 103-115.

- Boyer, J.S. , Plant productivity and environment. Science 1982, 218, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comas, L.H. , et al., Root traits contributing to plant productivity under drought. Frontiers in plant science 2013, 4, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, H., X. Ma, and G. Yan, Screening wheat (Triticum spp.) genotypes for root length under contrasting water regimes: potential sources of variability for drought resistance breeding. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2015, 201, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A. , Screening and selection of tomato genotypes/cultivars for drought tolerance using multivariate analysis. Pak J of Bot 2014, 46, 1165–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Obidiegwu, J.E. , et al., Coping with drought: stress and adaptive responses in potato and perspectives for improvement. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.H. , et al., Genetics of drought tolerance at seedling and maturity stages in Zea mays L. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2016, 14, 0705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, L. , et al., A simple, fast and accurate screening method to estimate maize (Zea mays L) tolerance to drought at early stages. 2017.

- Foyer, C.H. , et al., Neglecting legumes has compromised human health and sustainable food production. Nature plants 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobler-Morales, C. and G. Bocco, Social and environmental dimensions of drought in Mexico: An integrative review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 55, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J., D. Katiyar, and A. Hemantaranjan, Drought mitigation strategies in pulses. Pharm. Innov. J 2019, 8, 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Porch, T.G. , et al., Release of tepary bean cultivar ‘USDA Fortuna’with improved disease and insect resistance, seed size, and culinary quality. Journal of Plant Registrations 2024, 18, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter, J.R. , et al., Successful introgression of abiotic stress tolerance from wild tepary bean to common bean. Crop Science 2017, 57, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Galindo, J.C. , et al., Inheritance and metabolomics of the resistance of two F 2 populations of Phaseolus spp. to Acanthoscelides obtectus. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2020, 14, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porch, T. , et al., Evaluation of common bean for drought tolerance in Juana Diaz, Puerto Rico. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2009, 195, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauser, R., H. U.R. Athar, and M. Ashraf, Chlorophyll fluorescence: a potential indicator for rapid assessment of water stress tolerance in canola (Brassica napus L.). Pakistan Journal of Botany 2006, 38, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar]

- Khodarahmpour, Z. , Effect of drought stress induced by polyethylene glycol (PEG) on germination indices in corn (Zea mays L.) hybrids. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 18222–18227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Galindo, J.C. , et al., Screening for Drought Tolerance in Tepary and Common Bean Based on Osmotic Potential Assays. Plant 2018, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, B.E. and M.R. Kaufmann, The osmotic potential of polyethylene glycol 6000. Plant physiology 1973, 51, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.B., W. E. Nyquist, and C.T. Cervantes-Martinez, Estimating and interpreting heritability for plant breeding: An update. Plant Breeding Reviews 2002, 22, 9–112. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.B. , Estimating genotypic correlations and their standard errors using multivariate restricted maximum likelihood estimation with SAS Proc MIXED. Crop Science 2006, 46, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.R. and D. Gothwal, Genetic variability for seedling characters in lentil under salinity stress. Electronic Journal of Plant Breeding 2018, 9, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. , et al., Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P. , Selection for water-stress tolerance in interracial populations of common bean. Crop Science 1995, 35, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briñez, B. , et al., Mapping QTLs for drought tolerance in a SEA 5 x AND 277 common bean cross with SSRs and SNP markers. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2017, 40, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Villegas, V., Q. Song, and J.D. Kelly, Genome-wide association analysis for drought tolerance and associated traits in common bean. The Plant Genome 2017, 10, plantgenome2015.12–0122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachiguma, N.A. , et al., Preliminary evaluation of genetic inheritance of root traits of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) for tolerance to low soil moisture. Journal of Agricultural and Crop Research 2021, 9, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.W. , et al., Inheritance of seed yield, maturity and seed weight of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) under semi-arid rainfed conditions. The Journal of Agricultural Science 1994, 122, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, M.M. , et al., Effect of PEG induced drought stress on germination and seedling traits of maize (Zea mays L.) lines. Türk Tarım ve Doğa Bilimleri Dergisi 2019, 6, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F. , et al., The difference of physiological and proteomic changes in maize leaves adaptation to drought, heat, and combined both stresses. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruta, N. , et al., Collocations of QTLs for seedling traits and yield components of tropical maize under water stress conditions. Crop science 2010, 50, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. and P.M. Neumann, Water-stressed maize, barley and rice seedlings show species diversity in mechanisms of leaf growth inhibition. Journal of Experimental Botany 1998, 49, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ortega, A. , et al., Osmotic stress tolerance in forage oat varieties (Avena Sativa L.) based on osmotic potential trials. 2023.

- Araújo, A.P., I. F. Antunes, and M.G. Teixeira, Inheritance of root traits and phosphorus uptake in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under limited soil phosphorus supply. Euphytica 2005, 145, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A., M. W. Blair, and P.C. Struik, Multienvironment quantitative trait loci analysis for photosynthate acquisition, accumulation, and remobilization traits in common bean under drought stress. G3: Genes| Genomes| Genetics 2012, 2, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, T. , et al., Genetic potential and inheritance pattern of phenological growth and drought tolerance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 705392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, I. , Soil-root-canopy interactions. Annals of Applied Biology 2001, 138, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, R.R. , et al., Integrated genomics, physiology and breeding approaches for improving drought tolerance in crops. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2012, 125, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terán, H. and S.P. Singh, Selection for drought resistance in early generations of common bean populations. Canadian journal of plant science 2002, 82, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Galindo, J.C. and J.A. Acosta Gallegos, Rendimiento de frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) y Tépari (Phaseolus acutifolius A. Gray) bajo el método riego-sequía en Chihuahua. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2013, 4, 599–610. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Galindo, J.C. and J.A. Acosta Gallegos, Caracterización de genotipos criollos de frijol Tepari (Phaseolus acutifolius A. Gray) y común (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) bajo temporal. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2012, 3, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A. , et al., Germination of different seed size of pinto bean cultivars as affected by salinity and drought stress. Journal of Food Agriculture & Environment 2009, 7, 555–558. [Google Scholar]

- Vadez, V. , et al., Transpiration efficiency: new insights into an old story. Journal of experimental botany 2014, 65, 6141–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide: Statistical Procedures. Version 9.4; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SIAP-SADER. 2023. Sistema de Información Agro Pecuaria de la Secretaria de Desarrollo Rural. Available online: https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

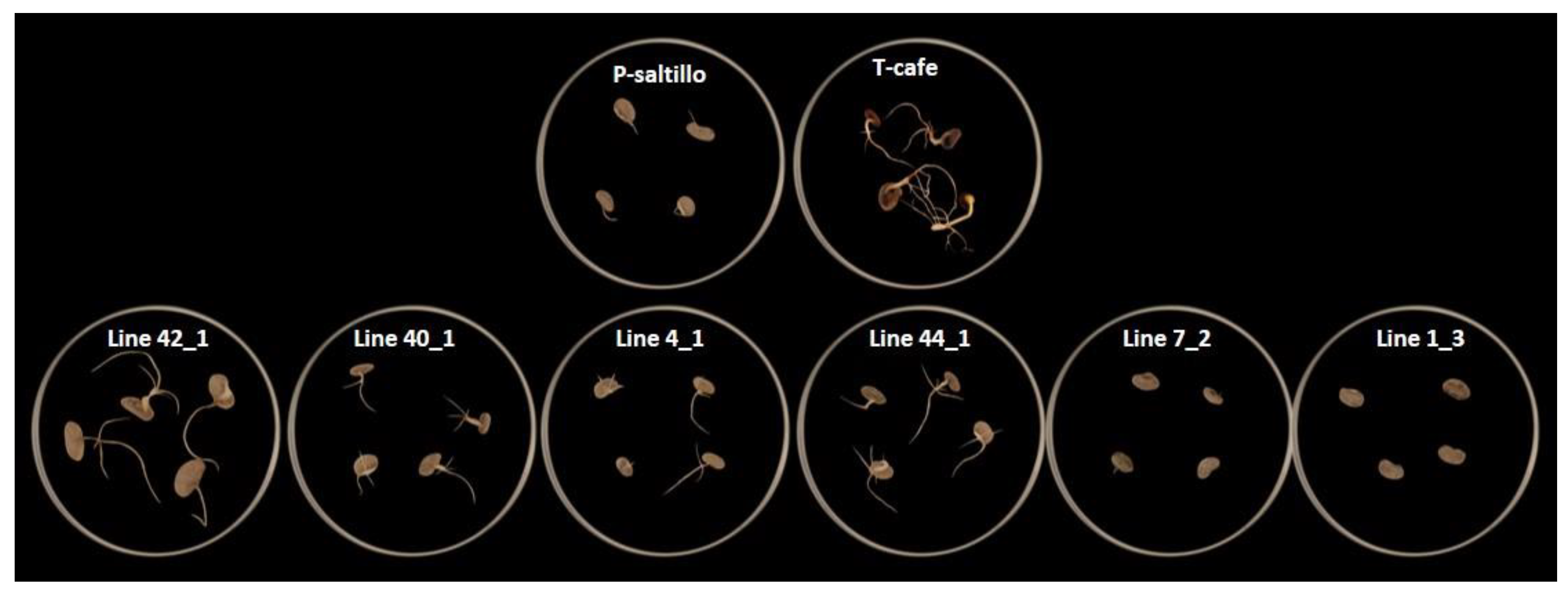

| Parental lines | Grain color | Race | Drought tolerant level |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-saltilloa | White-brown | Durango | Susceptibleb |

| T-cafea | Brown | Wild | Tolerantb |

| HL | GSNH | GSPH | RL | GSNR | GSPR | TL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F3 | ||||||||

| Mean | 1.06 | 2.45 | 61.42 | 2.62 | 2.44 | 61.11 | 2.39 | |

| Rank | 0-2.4 | 0.30-3.9 | 7.5-97.5 | 0.3-4.5 | 0.3-3.9 | 7.5-97.5 | 0.0-4.8 | |

| h2 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.20 | |

| Parents | ||||||||

| T-café | 1.18 a | 4.00 a | 100.00 a | 4.35 a | 4.00 a | 100.00 a | 5.88 a | |

| P-saltillo | 0.95 a | 3.00 b | 75.00 b | 2.67 b | 3.00 b | 75.00 b | 2.89 b | |

| LSD P > 0.05 | 4.09 | 75E-16 | 0.0 | 0.62 | 75E-16 | 0.0 | 1.14 | |

| HL | GSNH | GSPH | RL | GSNR | GSPR | TL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL | 0.48 | 0.34* | 0.80* | 0.53* | 0.38* | 0.41 | |

| GSNH | -0.04 | 1.0* | 1.0* | 1.0* | 0.99* | 0.99* | |

| GSPH | -0.04 | 1.0* | 1.0* | 0.99* | 1.0* | 0.99* | |

| RL | 0.27* | 0.17* | 0.17* | 1.0* | 1.0* | 1.0* | |

| GSNR | -0.02 | 0.98* | 0.97* | 0.18* | 1.0* | 0.97* | |

| GSPR | -0.02 | 0.97* | 0.98* | 0.18* | 1.0* | 0.97* | |

| TL | 0.07 | 0.73* | 0.73* | 0.63* | 0.75* | 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).