Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Location and Arrangement of the Experiment

2.2. Statistical Analysis

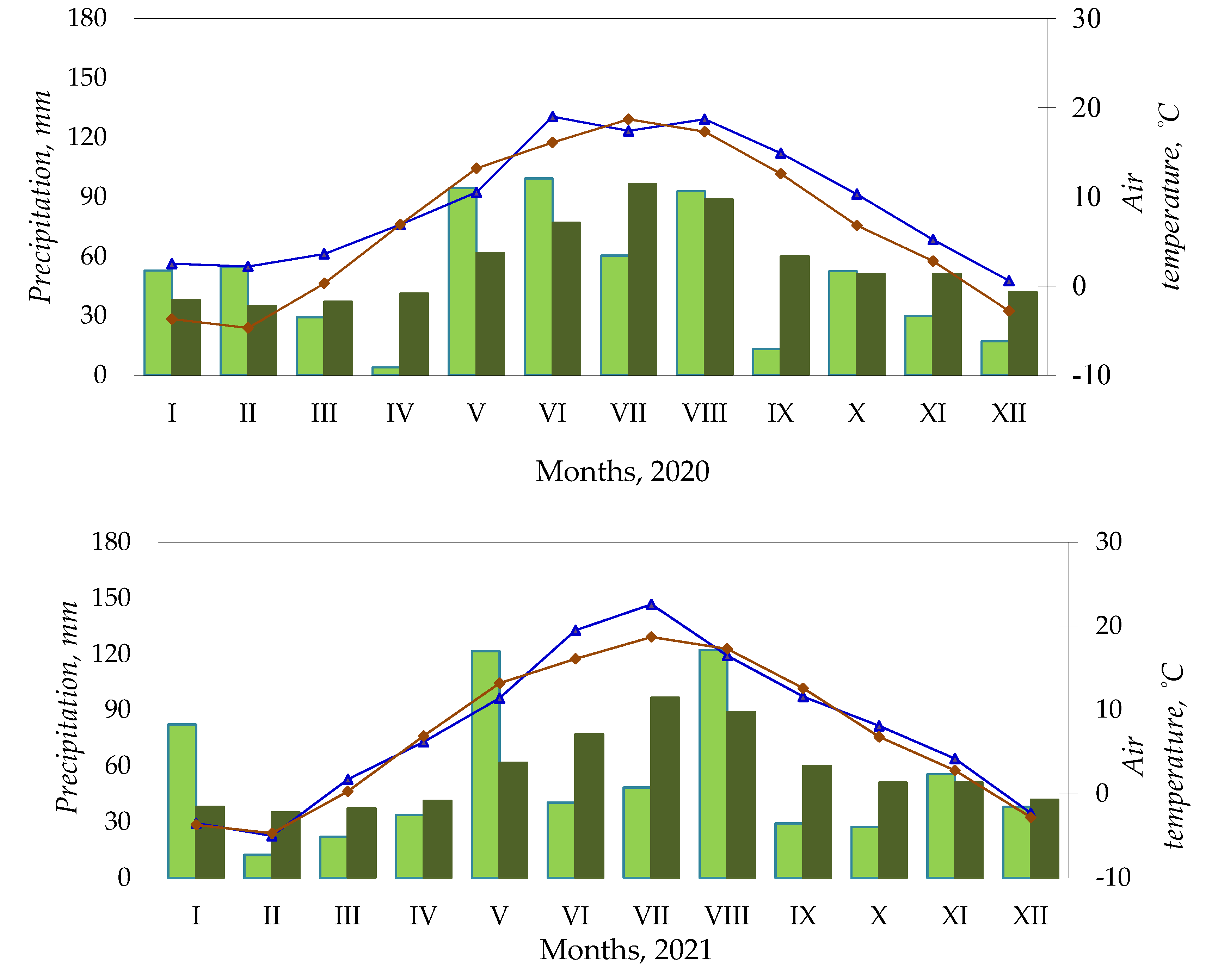

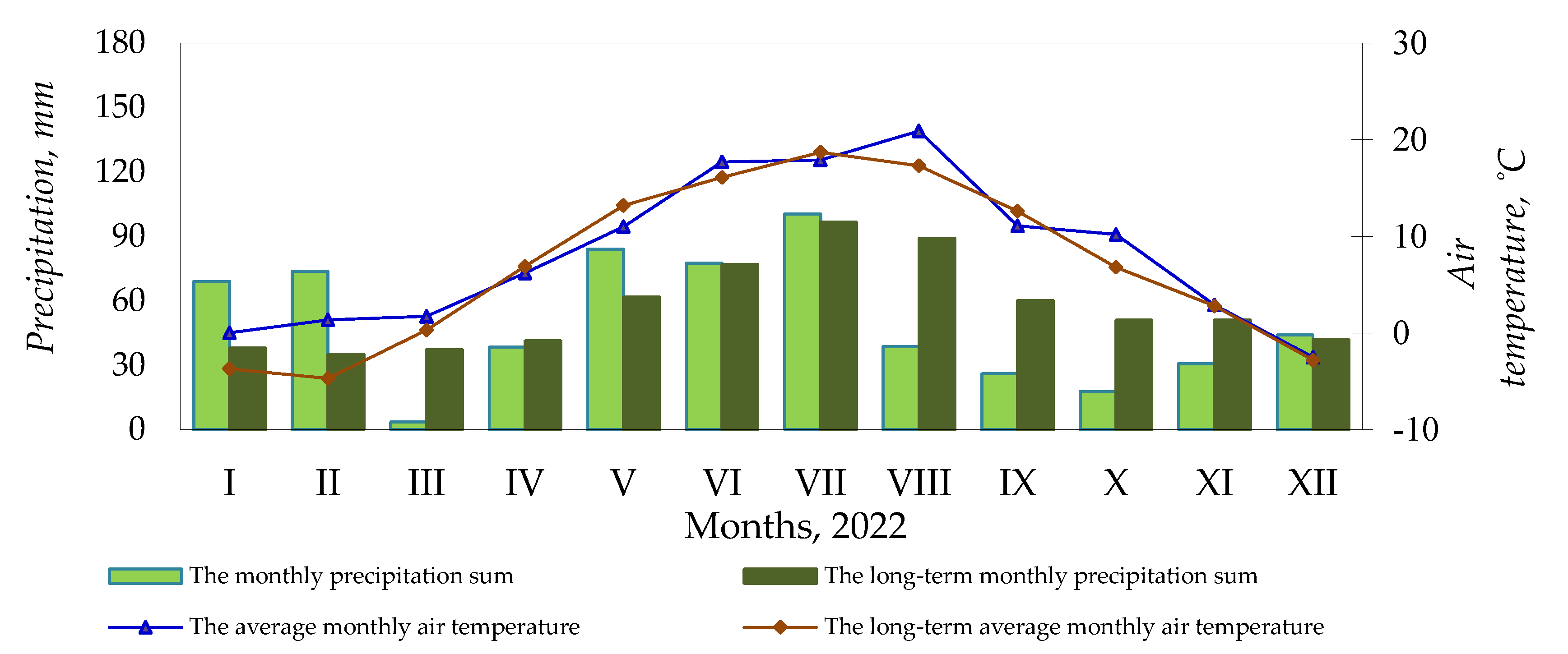

2.3. Weather Conditions

3. Results

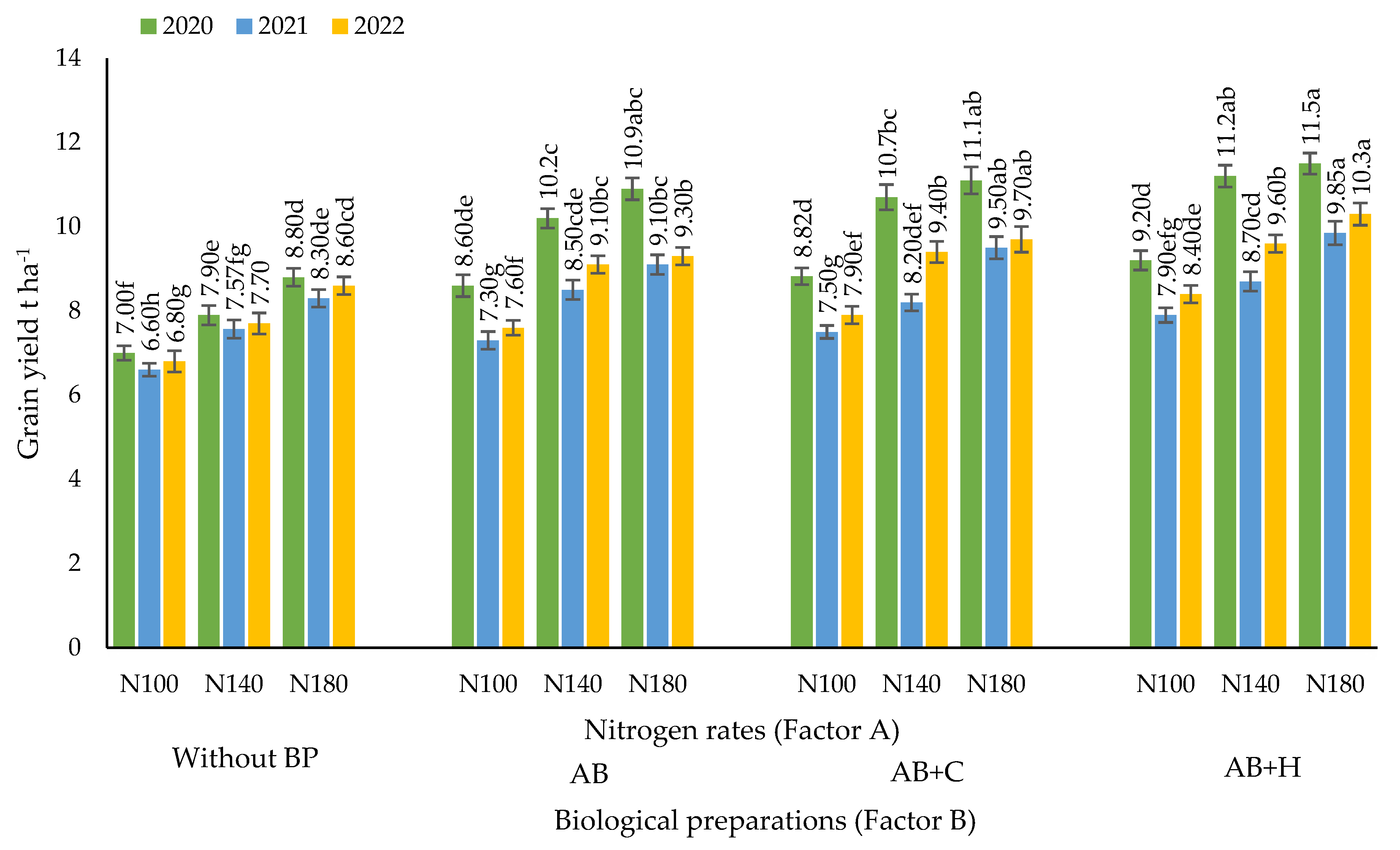

3.1. Effects of the Factors Studied on Maize Grain Yield

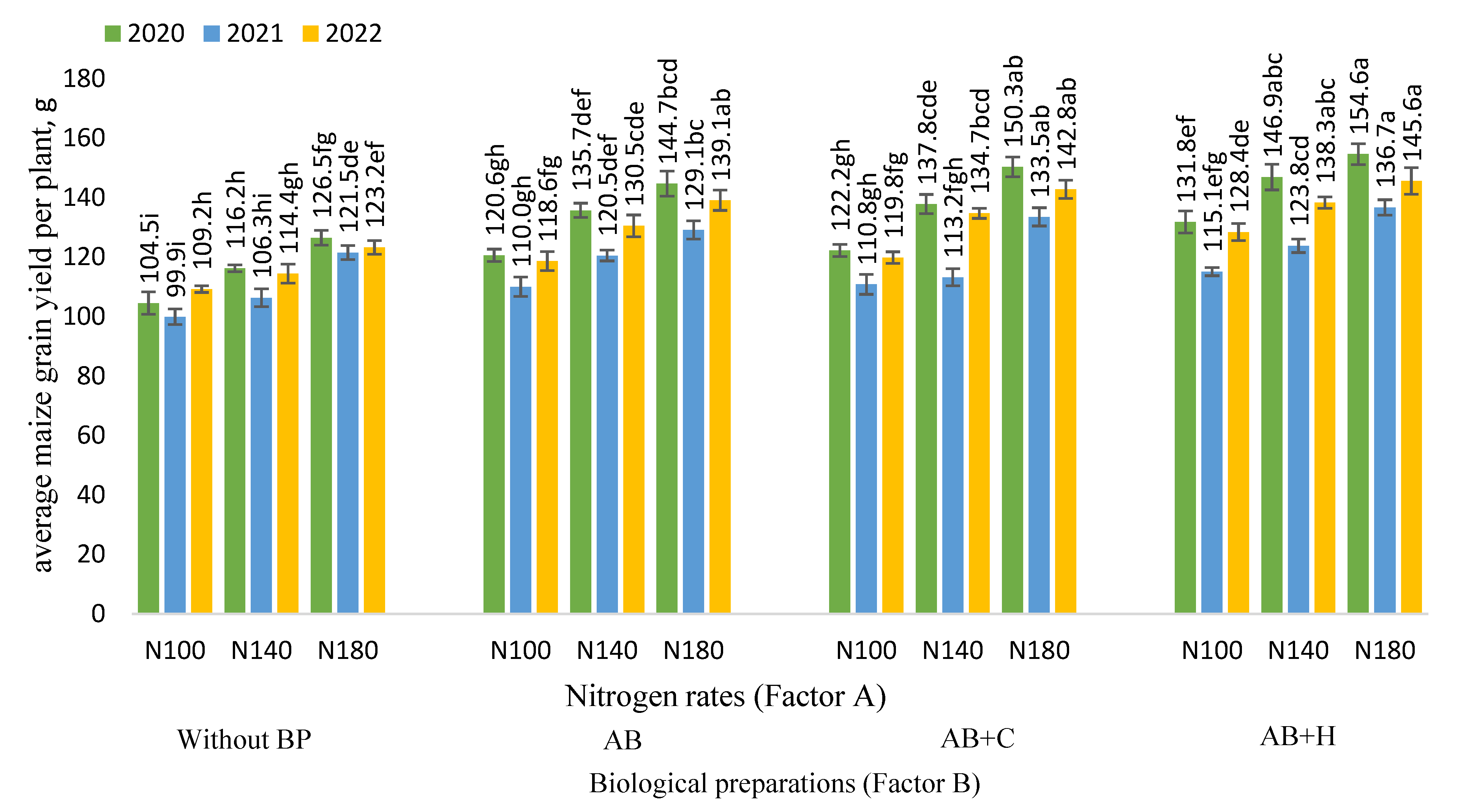

3.2. Effects of the Factors Studied on Maize Grain Yield per Plant

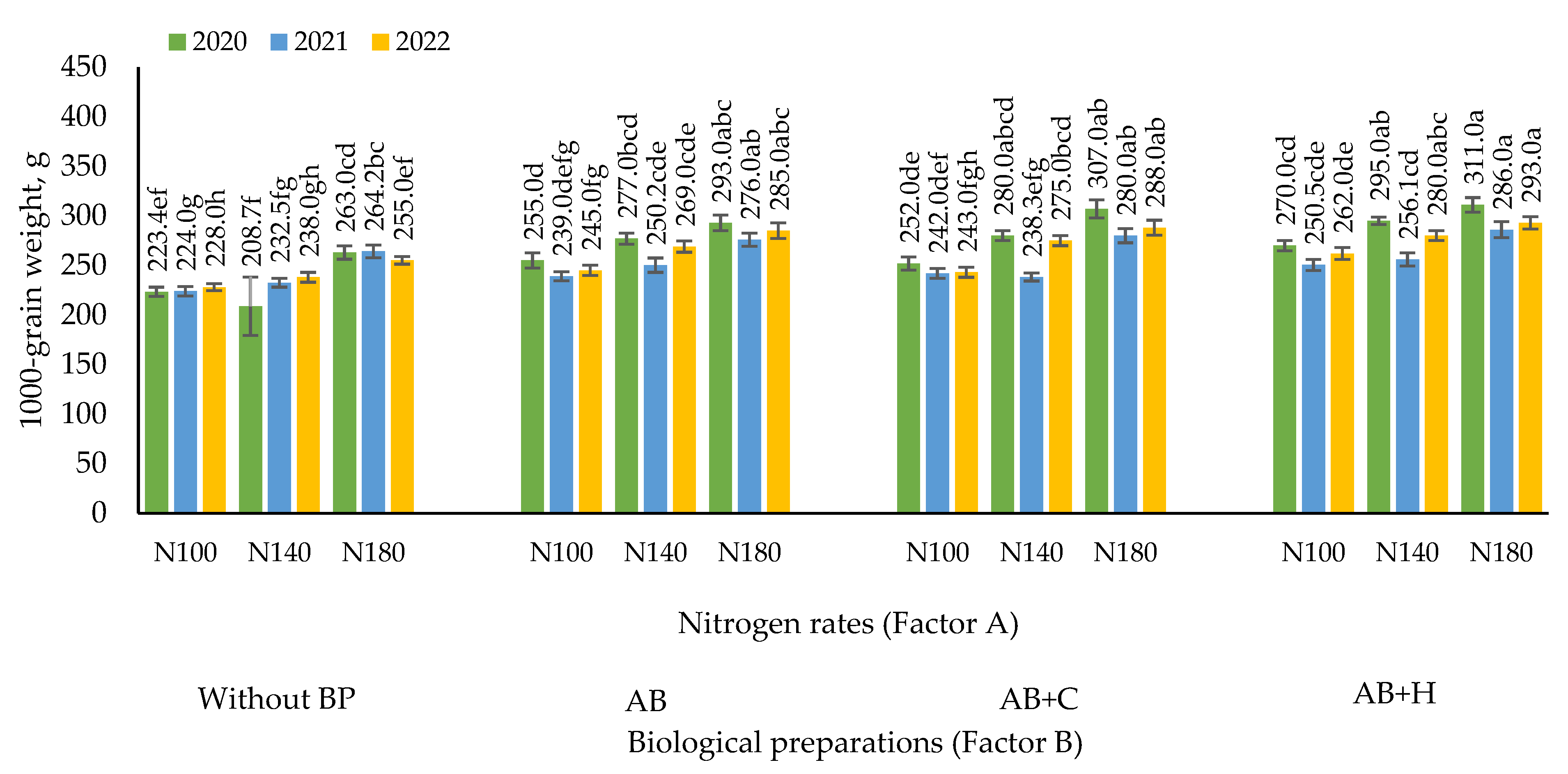

3.3. Effects of the Factors Studied on the 1000-grain Weight of Maize

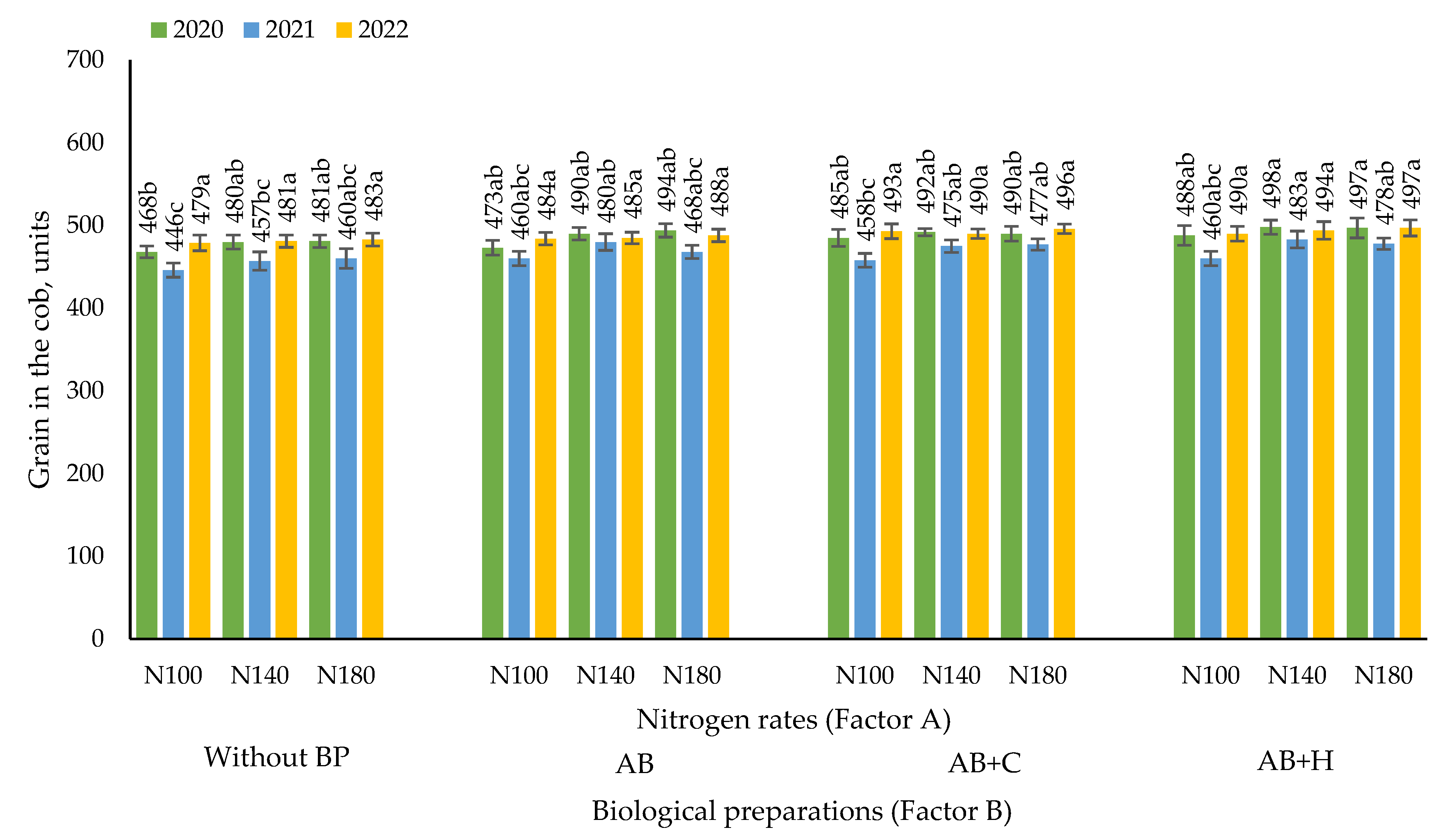

3.4. Effects of the Factors Studied on the Number of Maize Grains per Cob

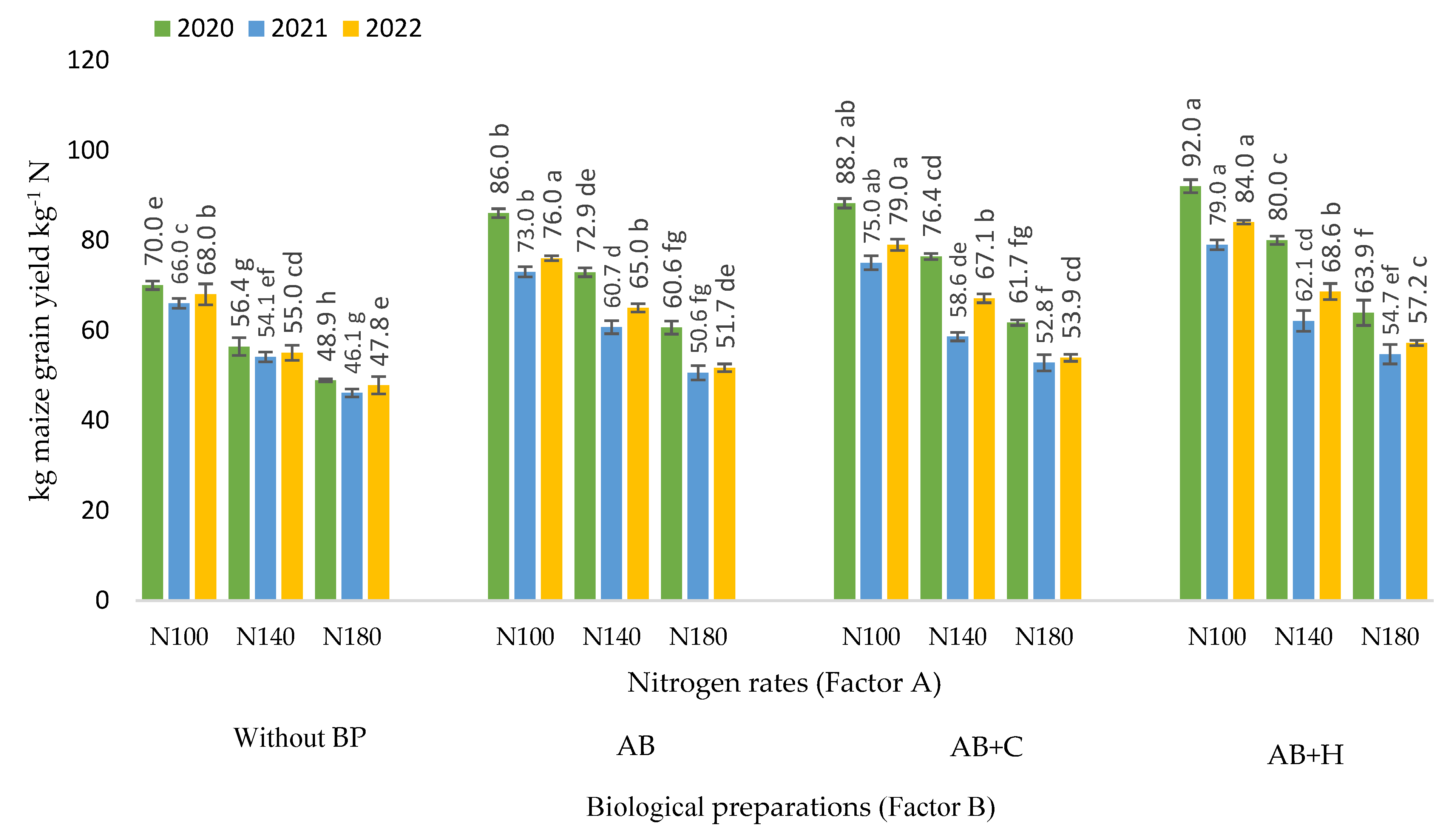

3.5. Effects of Factors Studied on Partial Factor Productivity of Nitrogen

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Gobal maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Széles, A.; Horváth, E.; Simon, K.; Zagyi, P.; Huzsvai, L. Maize production under drought stress: nutrient supply, yield prediction. Plants 2023, 12, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.A.A.; El-Magharby, S.S.; Ibrahim, N.S.; Kandil, E.E.; Abdelsalam, N.R. Productivity and quality variations in sugar beet induced by soil application of K-Humate and foliar application of biostimulants under salinity condition. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 872–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rácz, D.; Szőke, L.; Tóth, B.; Kovács, B.; Horváth, É.; Zagyi, P.; Duzs, L.; Széles, A. Examination of the productivity and physiological responses of maize (Zea mays L.) to nitrapyrin and foliar fertilizer treatments. Plants 2021, 10, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocwa, A.; Harsányi, E.; Széles, A.; Holb, J.; Szabó, S.; Rátonyi, T.; Mohammed, S. A bibliographic review of climate change and fertilization as the main drivers of maize yield: implications for food security. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.C. Biostimulants and agri-environment measures in order to increase the agricultural sustainability. Symposium on Advanced Engineering Technologies, 2019. 15–19.

- Ördög, V.; Stirk, W.A.; Takacs, G.; Pothe, P.; Illes, A.; Bojtor, C.; Szeles, A.; Toth, B.; Van Staden, J.; Nagy, J. Plant biostimulating effects of the cyanobacterium Nostoc piscinale on maize (Zea mays L.) in field experiments. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 140, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Muller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. The use of biostimulants for enhancing nutrient uptake. Adv. Agron. 2015, 130, 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanek, M.; Wilczewski, E. Maize response to soil-applied humic substances and foliar fertilization with potassium. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2016, 26, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Efthimiadou, A.; Katsenios, N.; Chanioti, S.; Giannoglou, M.; Djordjevic, N.; Katsaros, G. Effect of foliar and soil application of plant growth promoting bacteria on growth, physiology, yield and seed quality of maize under Mediterranean conditions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripaldi, C.; Novero, M.; Di Giovanni, S.; Chiarabaglio, P.M.; Lorenzoni, P.; Meo Zilio, D.; Palocci, G.; Balconi, C.; Aleandri, R. Impact of mycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere microorganisms on maize grain yield and chemical composition. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. vol. 2017, 54, 857–865. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, J.; Piotrowska-Długosz, A.; Kotwica, K.; Przybyszewska, E. Application of multi-component conditioner with clinoptilolite and ascophyllum nodosum extract for improving soil properties and Zea mays L. growth and yield. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Balmori, D.M.; Médici, L.O.; et al. A combination of humic substances and Herbaspirillum seropedicae inoculation enhances the growth of maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Soil 2013, 366, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torun, H.; Toprak, B. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and K-Humate combined as biostimulants: changes in antioxidant defense system and radical scavenging capacity in Elaeagnus angustifolia. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asibi, E.A.; Chai, Q.; Coulter, J.A. Mechanisms of Nitrogen Use in Maize. Agronomy 2019, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, O.; Hewedy, O.A.; Abdelmoteleb, A.; Mohammed, A.; Youssef, M.S.; Roumia, A.F.; Seymour, D.; Ze-Chun, Y. Nitrogen Journey in Plants: From Uptake to Metabolism, Stress Response, and Microbe Interaction. Biomolecules 2023, 25, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirel, B.; Tétu, T.; Lea, P.J.; Dubois, F. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in crops for sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1452–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichern, F.; Mayer, J.; Joergensen, R.G.; Müller, T. Release of C and N from roots of peas and oats and their availability to soil microorganisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2829–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talla, S.K.; Panigrahy, M.; Kappara, S.; Nirosha, P.; Neelamraju, S.; Ramanan, R. Cytokinin delays dark-induced senescence in rice by maintaining the chlorophyll cycle and photosynthetic complexes. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, G.; Alarcón, M.V.; Salguero, J. Cytokinin Inhibits Lateral Root Development at the Earliest Stages of Lateral Root Primordium Initiation in Maize Primary Root. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wybouw, B.; De Rybel, B. Cytokinin–a developing story. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janečková, H.; Husičková, A.; Lazár, D.; Ferretti, U.; Pospíšil, P.; Špundová, M. Exogenous application of cytokinin during dark senescence eliminates the acceleration of photosystem II impairment caused by chlorophyll b deficiency in barley. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 136, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, T.; Kiba, T.; Sakakibara, H. Metabolism and long-distance translocation of cytokinins. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaba, M.; Tanaka, A.; Tanaka, R. Stay-green plants: What do they tell us about the molecular mechanism of leaf senescence. Photosynth. Res. 2013, 117, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burr, C.A.; Sun, J.; Yamburenko, M.V.; Willoughby, A.; Hodgens, C.; Boeshore, S.L.; Elmore, A.; Atkinson, J.; Nimchuk, Z.L.; Bishopp, A. The HK5 and HK6 cytokinin receptors mediate diverse developmental pathways in rice. Development. 2020, 147, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E.; Street, I.H.; Kieber, J.J. Cytokinin and the cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drulis, P.; Kriaučiūnienė, Z.; Liakas, V. The Effect of combining N-fertilization with urease inhibitors and biological preparations on maize biological productivity. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drulis, P.; Kriaučiūnienė, Z.; Liakas, V. The influence of different nitrogen fertilizer rates, urease inhibitors, and biological preparations on maize grain yield and yield structure elements. Agronomy 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazid, M.; Khan, T.A. Future of Bio-fertilizers in Indian agriculture: An Overview. Int. J. Agric. Food Res. 2014, 3, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindersah, R.; Kamaluddin, N.N.; Samanta, S.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, S. Role and perspective of Azotobacter in crops production. STJSSA 2020, 21, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Hydrolytic enzymes of rhizospheric microbes in crop protection. MOJ Cell Sci. Rep. 2016, 3, 135–136. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Perdomo, F.; Abril, J.; Camelo, M.; Moreno-Galvįn, A.; Pastrana, I.; Rojas-Tapias, D.; Bonilla, R. Azotobacter chroococcum as a potentially useful bacterial biofertilizer for cotton (Gossypium hirsutum): Effect in reducing N fertilization. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2017, 49, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindersah, R.; Kalay, M.; Talahaturuson, A.; Lakburlawal, Y. Nitrogen fixing bacteria azotobacter as biofertilizer and biocontrol in long bean. Agric. 2018, 30, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, N.S.; Din, A.R.J.M.; Rosli, M.A.; Azam, Z.M.; Othman, N.Z.; Sarmidi, M.R. Paenibacillus polymyxa bioactive compounds for agricultural and biotechnological applications. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, A.; Li, X.; Ma, D.; Xin, X.; et al. Nitrate accumulation and leaching potential reduced by coupled water and nitrogen management in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fixen, P.; Brentrup, F.; Bruulsema, T.; Garcia, F.; Norton, R.; Zingore, S. Nutrient/fertilizer use efficiency; measurement, current situation and trends. In P. Drechsel, et al., (Eds.), Managing water and fertilizer for sustainable agricultural intensification. International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA), international Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), and International Potash Institute (IPI) 1st ed, Paris, France, 2014, pp. 8–38.

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. 4th edition. International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS), Vienna, Austria, 2022. Adetunji, A.

- Dobermann, A.R. Nitrogen use efficiency-state of the art. Agronomy--Faculty Publications 2005, 316, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tarakanovas, P.; Raudonius, S. Agronominių tyrimų duomenų statistinė analizė taikant kompiuterines programas ANOVA, STAT, SPLIT-PLOT iš paketo SELEKCIJA ir IRRISTAT. Akademija, 2003, pp. 56.

- Raudonius, S. Application of statistics in plant and crop research: important issues. Zemdirbystė 2017, 104, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.F.C.; Mendonça, E.S.; Machado, P.L.O.A. Influence of organic and mineral fertilisation on organic matter fractions of a Brazilian Acrisol under maize/common bean intercrop. Soil Res. 2007, 45, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Li, J.; Li, Q.X.; Chen, S.F. Paenibacillus beijingensis sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing species isolated from wheat rhizosphere soil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 104, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.; Eid, K.E.; Abbas, M.H.H.; Salem, A.A.; Ahmed, N.; Ali, M.; Shah, G.M.; Fang, C. Use of plant growth promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and mycorrhizae to improve the growth and nutrient utilization of common bean in a soil in fected with white rot fungi. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Bisht, N.; Ansari, M.M.; Mishra, S.K.; Chauhan, P.S. Paenibacillus lentimorbus alleviates nutrient deficiency-induced stress in Zea mays by modulating root system architecture, auxin signaling, and metabolic pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Yajnik, K.N.; Mogilicherla, K.; Singh, I.K. Deciphering the role of growth regulators in enhancing plant immunity against herbivory. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccin, D.; Di Piero, R.M. Extracts and fractions of humic substances reduce bacterial spot severity in tomato plants, improve primary metabolism and activate the plant defense system. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 121, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.; Olivares, F.L.; Peres, L.E.P.; Piccolo, A.; Canellas, L.P. Plant hormone crosstalk mediated by humic acids. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent variables y |

Factor B | Regression equation |

Correlation coefficient r |

Coefficient of determination r2 |

Probability level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

y(2020) – grain yield (t ha-1) |

Without BP | y = 4.75 + 0.02x | 0.93 | 0.86 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 5.88 + 0.03x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 6.22 + 0.03x | 0.87 | 0.76 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 6.61 + 0.03x | 0.87 | 0.76 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2021) – grain yield (t ha-1) |

Without BP | y = 4.52 + 0.02x | 0.93 | 0.86 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 5.15 + 0.02x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 4.90 + 0.03x | 0.93 | 0.86 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 5.40 + 0.02x | 0.92 | 0.85 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2022) – grain yield (t ha-1) |

Without BP | y = 4.55 + 0.02x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 5.69 + 0.02x | 0.86 | 0.74 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 5.85 + 0.02x | 0.85 | 0.72 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 6.11 + 0.02x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 |

| Dependent variables y |

Factor B | Regression equation | Correlation coefficient r |

Coefficient of determination r2 |

Probability level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

y(2020) – maize grain yield per plant (g) |

Without BP | y = 77.3 + 0.28x | 0.92 | 0.85 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 91.5 + 0.30x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 87.5 + 0.35x | 0.94 | 0.88 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 104.5 + 0.28x | 0.85 | 0.72 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2021) – maize grain yield per plant (g) |

Without BP | y = 71.4 + 0.27x | 0.90 | 0.81 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 86.4 + 0.24x | 0.89 | 0.79 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 79.4 + 0.28x | 0.84 | 0.71 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 87.5 + 0.27x | 0.94 | 0.88 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2022) – maize grain yield per plant (g) |

Without BP | y = 91.0 + 0.18x | 0.86 | 0.74 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 93.5 + 0.26x | 0.86 | 0.74 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 92.2 + 0.29x | 0.93 | 0.86 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 107.3 + 0.22x | 0.83 | 0.69 | P < 0.01 |

| Dependent variables y |

Factor B | Regression equation | Correlation coefficient r |

Coefficient of determination r2 |

Probability level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

y(2020) – 1000-grain weight of maize (g) |

Without BP | - | - | - | P > 0.05 |

| AB | y = 208.5 + 0.48x | 0.84 | 0.71 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 183.4 + 0.69x | 0.91 | 0.83 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 220.2 + 0.51x | 0.90 | 0.81 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2021) – 1000-grain weight of maize (g) |

Without BP | y = 169.9 + 0.50x | 0.87 | 0.76 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 190.3 + 0.46x | 0.85 | 0.72 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 186.9 + 0.48x | 0.76 | 0.58 | P < 0.05 | |

| AB+H | y = 202.1 + 0.44x | 0.79 | 0.62 | P < 0.05 | |

|

y(2022) – 1000-grain weight of maize (g) |

Without BP | y = 193.1 + 0.34x | 0.88 | 0.77 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 196.3 + 0.50x | 0.87 | 0.76 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 189.9 + 0.56x | 0.89 | 0.79 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 224.1 + 0.39x | 0.84 | 0.71 | P < 0.01 |

| Dependent variables y |

Factor B | Regression equation | Correlation coefficient r |

Coefficient of determination r2 |

Probability level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

y(2020) – kg maize grain kg-1 N |

Without BP | y = 95.4 – 0.26x | -0.96 | 0.92 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 117.6 – 0.32x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 121.8 – 0.33x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 127.8 – 0.35x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2021) – kg maize grain kg-1 N |

Without BP | y = 90.2 – 0.25x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 100.6 – 0.28x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 100.9 – 0.28x | -0.94 | 0.88 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 107.8 – 0.30x | -0.95 | 0.90 | P < 0.01 | |

|

y(2022) – kg maize grain kg-1 N |

Without BP | y = 92.3 – 0.25x | -0.94 | 0.88 | P < 0.01 |

| AB | y = 106.8 – 0.30x | -0.98 | 0.96 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+C | y = 110.6 – 0.31x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 | |

| AB+H | y = 116.8 – 0.34x | -0.97 | 0.94 | P < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).