Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Particularity of Knowledge-Implied EVE Data. Except for traditional big data characteristics [19], EVE big data imply underlying complex domain-specific mechanisms, e.g., the EV energy recovery during braking. General data-driven approaches, which often neglect the incorporation of inherent domain knowledge, face significant challenges in accurately modeling EVE status [8,12,20]. Consequently, developing a framework that facilitates the seamless embedding of subtle and domain-specific knowledge is of paramount importance for achieving precise EVEM.

- Constraints of Resource-Limited EVEM Systems. Networked EVEM systems comprising heterogeneous devices with varying computational and communication capabilities. Traditional edge- and cloud-based schemes, while widely adopted, are often constrained by computational limitations (e.g., on-site EV devices with restricted processing power and memory) or communication bottlenecks (e.g., limited V2X bandwidth under dynamic network conditions). These inherent constraints significantly hinder their ability to ensure prompt and reliable responses required for latency-sensitive applications [21]. Consequently, an efficient EVEM framework capable of operating within limited resources is indispensable for practical deployment.

- Deficiencies of Distributed EVEM Systems and Isolated EVE Data. To protect the privacy [22,23] of different EV stakeholders like manufacturers, vendors, and consumers, EVEM systems are physically distributed and networked, and EVE data are strictly isolated and unassociated [24]. The property critically affects the feasibility and efficiency of EVEM, particularly in scenarios where multi-party and multi-scale spatio-temporal joint analysis is essential for accurate big data analysis. Therefore, addressing these challenges within the framework design is crucial to ensure comprehensive and practical EVEM.

- 1)

- We conduct the first comprehensive investigation on intelligent EVEM. Particularly, we clarify essential EVEM applications at the driver-, enterprise-, and social-levels, effectively highlighting the practical significance of EVEM. Meanwhile, we systematically identify and extract the key challenges associated with designing and implementing a framework for intelligent EVEM, providing

- 2)

- We propose a novel big data framework, termed iEVEM, to address the challenges as mentioned above. Specifically, we construct a layered architecture of EVE data processing and analysis, starting from the physical layer, which manages heterogeneous and isolated EVE data for data collection. This is followed by the data layer and algorithm layer, which enable supporting the efficient design of knowledge-enhanced intelligent solutions, ultimately supporting diverse intelligent EVEM applications in the application layer. Additionally, an edge-cloud collaborative system architecture is introduced to facilitate practical application deployment while effectively addressing the resource constraints of distributed systems.

- 3)

- We conducted a proof-of-concept case study of iEVEM using real-world data to validate its effectiveness. For EV energy consumption outlier detection, the experimental results demonstrate that iEVEM achieves significant improvements in both detection accuracy, with gains of up to 47.48% higher, and response speed, being at least 3.07 × faster compared with state-of-the-art methods. Furthermore, we also highlight several important open issues and research directions for the further development and refinement of intelligent EVEM.

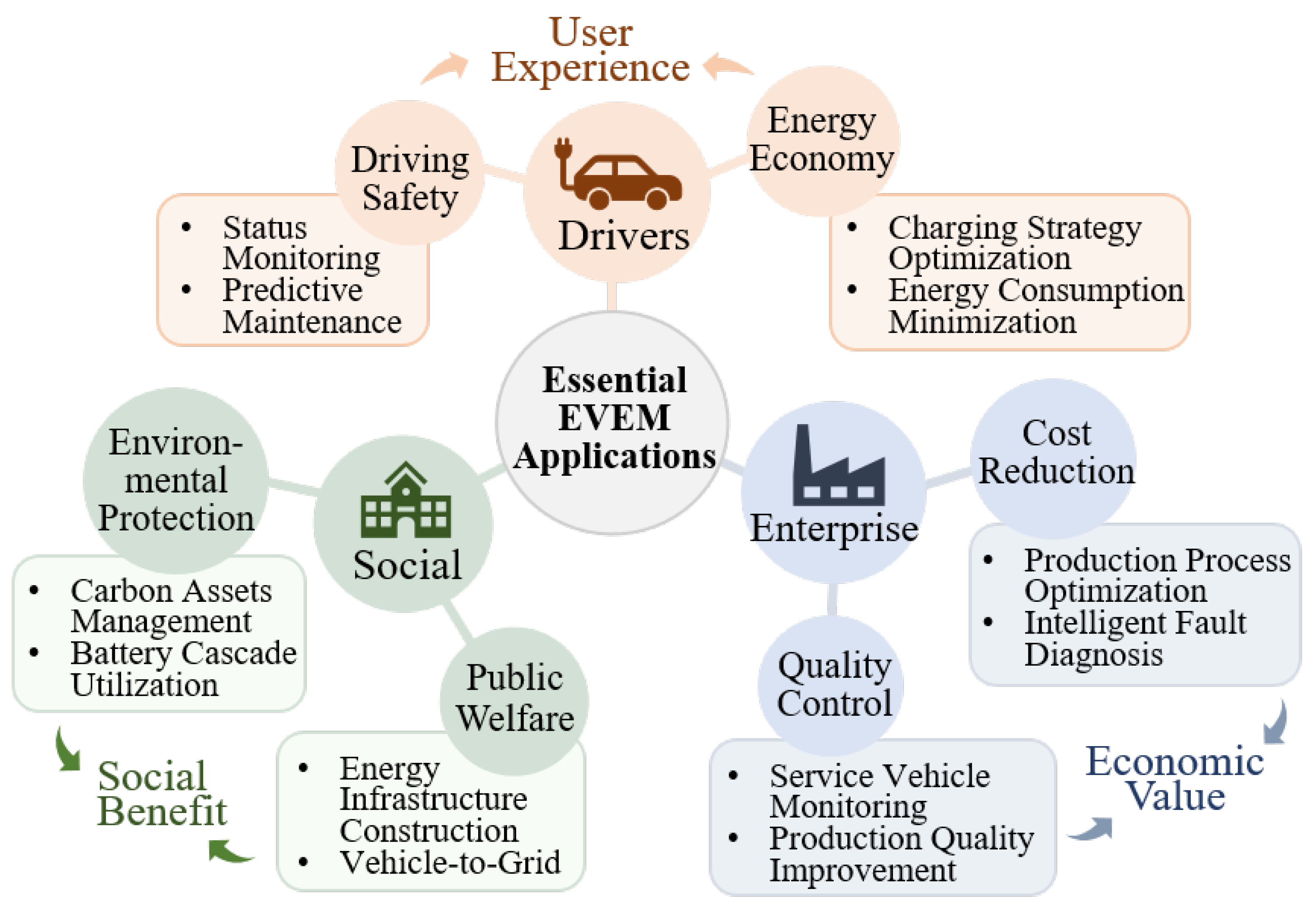

2. Essential EVEM Applications

2.1. Driver-Level Applications

2.1.1. Driving Safety

2.1.2. Energy Economy

2.2. Enterprise-Level Applications

2.2.1. Quality Control

2.2.2. Cost Reduction

2.3. Social-Level Applications

2.3.1. Environmental Protection

2.3.2. Public Welfare

3. Challenges to the EVEM Framework

3.1. Data Challenges

- ①

- It is difficult to accurately model EVE using general methods due to underlying complex knowledge. On one hand, given the inherent complexity, nonlinearity, and uncontrollability of energy reactions, EVE status is hard to model formally, which brings great challenges for existing mechanism-driven methods. On the other hand, lacking effective solutions to integrate inherent knowledge, pure data-driven methods struggle to model EVE accurately [8,12] and cannot support reliable EVEM.

- ②

- Unassociated fragmented EVE data pose challenges to multi-scale spatio-temporal correlation analysis. Since EVE status is impacted by a range of factors varying over space and time, multi-scale joint analysis is necessary for EVEM. However, EVE data are collected and possessed in distributed manners and isolated at different owners (e.g., drivers, enterprises, and government agencies) without a way to associate [36]. This seriously impedes the feasibility of joint analysis.

3.2. System Challenges

- ③

- Rapid response is difficult to satisfy by conventional schemes with limited system resources. In the naturally distributed EVEM systems, low end-to-end (E2E) latency is challenging with limited computing capabilities of edge nodes (e.g., vehicle-mounted devices) and communication resources between nodes (e.g., moving EVs) [21]. Specifically, predominating cloud-based methods requiring massive data uploading suffer from prolonged communication time. Local-based methods, processing data locally entirely, result in unacceptable computation time and cannot support efficient EVEM.

- ④

- Isolated EVEM systems pose challenges to multi-party joint analysis. Numerous EVEM applications inherently require multiple stakeholders (e.g., drivers, enterprises, and government agencies) to participate. However, with widespread and growing privacy concerns [22,37] of participants, all data are best kept locally to prevent privacy leakage. Hence, the strictly isolated systems severely hinder the feasibility of joint analysis across multiple parties.

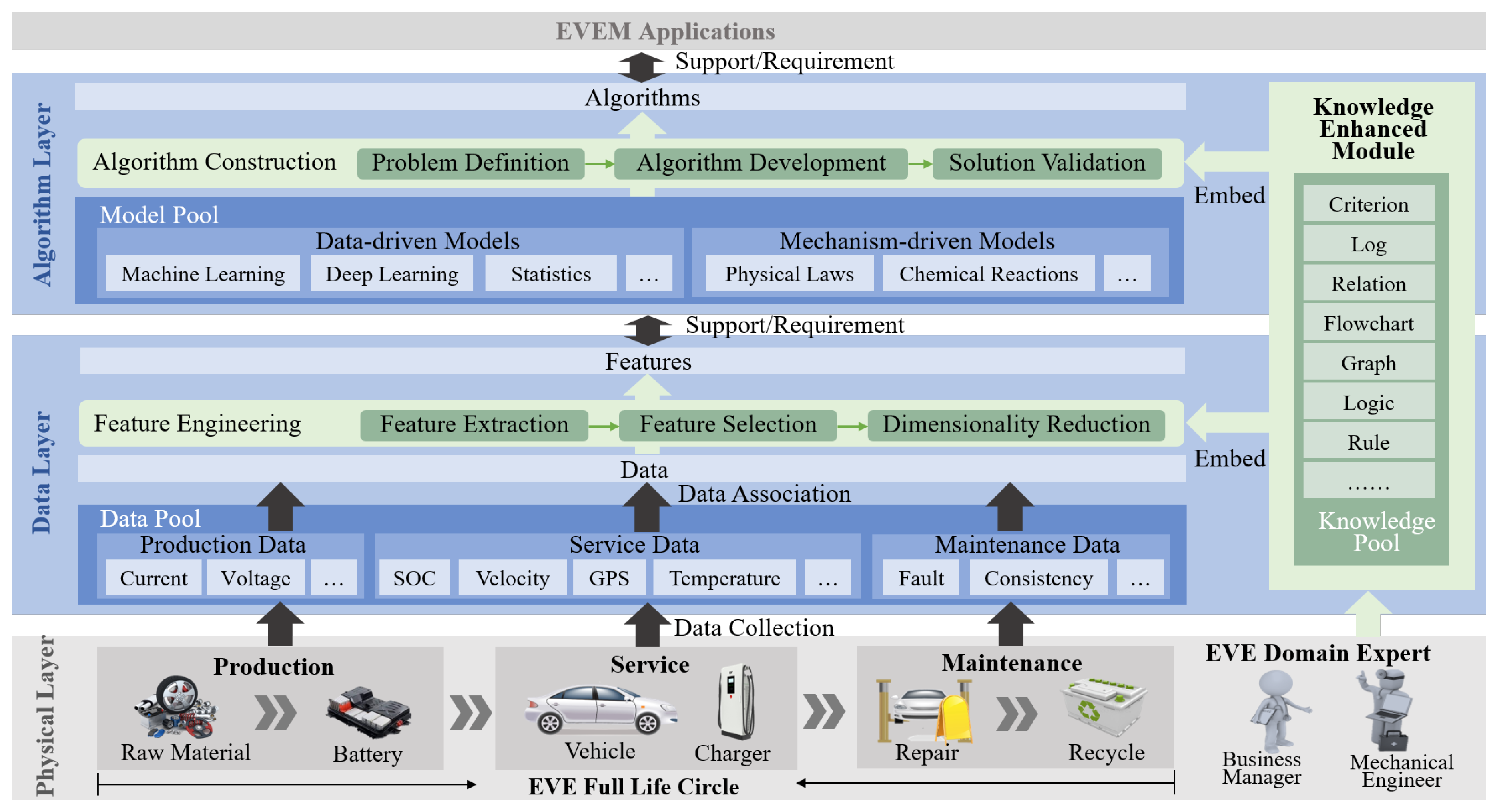

4. Data Intelligence Architecture of iEVEM

4.1. The Physical Layer

- Production Phase refers to the process from raw materials (e.g., electrolyte) to concrete power battery products (e.g., cell, module, and pack) [38]. Production data are collected by manufacturing equipment, mainly containing battery monitoring records (e.g., current, voltage, and resistance), which are generally structured in a predefined format like spreadsheets and acquired continuously near real-time following specific industrial standards (e.g., ISO 12405 in European Union).

- Service Phase indicates the usage of finished products like EVs and charging piles, where service data record their operating information. Particularly, EV service data are collected by on-board sensors [36] and mainly perceive the status of eic systems, i.e., the battery (e.g., temperature), motor (e.g., velocity), and controller (e.g., regenerative braking). Following the national standard (e.g., GB/T 32960 in China), service data are also collected in structured with a prescribed format and frequencies.

- Maintenance Phase indicates the status of out-of-service, including repairing and recycling. The maintenance data are collected by checkout equipment, which includes the testing information of productions, e.g., fault in repairing and RUL in recycling. Among them, repairing data are usually formatted in semi-structure and varied with enterprises, while recycling data tend to be structured in required testing procedures along with the increasingly published recycling standards (e.g., UL 1974 in America).

- Domain Expert refers to EVE-domain specialists, and the expert knowledge indicates the information converted by prior experience, which is evolved in aforementioned phases (e.g., working procedures in production, energy mechanisms in service, repairing logs in maintenance). Knowledge is usually formatted in semi-structured (e.g., worksheet) and unstructured data (e.g., text), and as an additional input for intelligent solution construction, knowledge representation and embedding are crucial.

4.2. The Data Layer

4.2.1. Data Association

4.2.2. Knowledge-Enhanced Feature Engineering

- Step 1: Feature Extraction transforms raw data into sets of features with underlying patterns. Traditional feature extraction, relying on straightforward mathematics properties (e.g., mean and variance), ignores physical meaning with potentially critical information unexplored (e.g., the peak of the incremental capacity curve is a decisive factor for capacity estimation [39]). Knowledge embedding effectively alleviates the issue by forming feature candidates for each data dimension in advance, which facilitates extracting meaningful features by the feat of expert experience.

- Step 2: Feature Selection intends to identify relevant features for given tasks from feature candidates, which is usually achieved by feature importance ranking. However, existing methods (e.g., decision tree) are prone to unstable ranking since they strongly rely on sample data. To enhance the reliability of task-oriented feature selection, expert knowledge is used to guide the identification of critical relevant features (e.g., expert knowledge can be utilized to assign feature weights in feature ranking) for given tasks.

- Step 3: Dimensionality Reduction refers to the process of reducing the quantity of features while preserving sufficient and necessary information, which significantly contributes to subsequent efficient data analysis and model performance. Traditional reduction methods (e.g., PCA and autoencoders) reduce features by changing feature spaces, where transformed dimensions lack clear physical meanings. Domain knowledge helps obtain refined features with practical meaning retained in original feature spaces (e.g., reduce redundant features according to physical correlations or integrate multiple features into one with practical meaning).

4.3. The Algorithm Layer

4.3.1. General Model

- Mechanism-driven Models are constructed based on the fundamental insights of underlying EVE mechanisms (e.g., physical laws and chemical reactions), which emphasize interpretability and physical fidelity, making them indispensable for EVEM. These models are mainly developed in formalized mathematical expressions for representing the intrinsic principles (e.g., the electrochemical and thermal dynamics of batteries, the operational characteristics of motors, and the energy flow in powertrain systems). For example, equivalent circuit models (ECMs) [7] are widely used to describe battery behavior, leveraging electrical circuit analogies to represent processes like charge transfer and diffusion. While mechanism-driven models exhibit strong interpretability, they often face challenges in terms of adaptability to complex, nonlinear, and uncontrollable energy reactions and systems. Nonetheless, these models remain a reserve and cornerstone for EVEM.

- Data-driven Models are constructed to uncover patterns, relationships, and decision-making rules directly from data, bypassing the need for explicit physical or mechanistic understanding. Such methods are primarily developed by statistics, machine learning, and deep learning. By virtue of learning patterns and relationships from massive historical data, the solution is built automatically based on mined rules. In the context of EVEM, supervised learning algorithms [29], such as decision trees in machine learning and neural networks in deep learning [20], are commonly used to predict battery degradation and RUL based on historical usage patterns. As another model basis of EVEM, the primary strength of data-driven models lies in their ability to automatically learn complex, nonlinear, and uncontrollable relationships from data without domain knowledge. However, these methods also exhibit notable drawbacks in their stability and reliability, suffering from their poor interpretability.

4.3.2. Knowledge-Enhanced Algorithm Construction

- Step 1: Problem Definition abstracts and models the target problem including task types (e.g., classification or regression) and requirements (e.g., optimization objectives and constraint conditions) from real scenarios, which should be expressed explicitly with the aid of domain experts. For instance, expert knowledge in text form can be transformed into optimization formulas through a large language model.

- Step 2: Algorithm Development indicates the design of specified intelligent solutions. Depending on the task type and requirements from the problem definition, practicable base models are selected from the model pool, whose characteristics have been elaborated in advance by experts. After that, the algorithm is designed (e.g., construct a novel one or modify general models) with further considering available data, application demands, and muttons with knowledge guidance (e.g., the optimum parameters are set by prior experience). Moreover, in a knowledge-enhanced way, in addition to expert-guided practicable general model selection and proper parameter setting, knowledge representation and embedding are utilized for algorithm design to further improve performance. For instance, the correlation of EVE components can be presented in the knowledge graph, where nodes represent components (e.g., battery, motor) and edges capture their dependencies (e.g., energy flow or thermal coupling). If a component fails, a graph neural network (GNN) operating on the knowledge graph can trace the connections to identify the root cause, such as linking abnormal motor performance to upstream issues like battery instability or inverter faults.

- Step 3: Solution Validation is the feasibility evaluation of constructed solutions before application launch. However, practical challenges arise for traditional methods (e.g., cross-validation) due to time and labor costs caused by the data availability (e.g., insufficient failure data make the verification of fault diagnosis difficult), label accessibility (e.g., limited labeled samples for cross-validation), and experiment producibility (e.g., battery degradation requiring years to manifest). Therefore, the validation design needs to rely on domain experts to fully consider actual situations (e.g., constructing a simulation environment by domain experts) to address this dilemma.

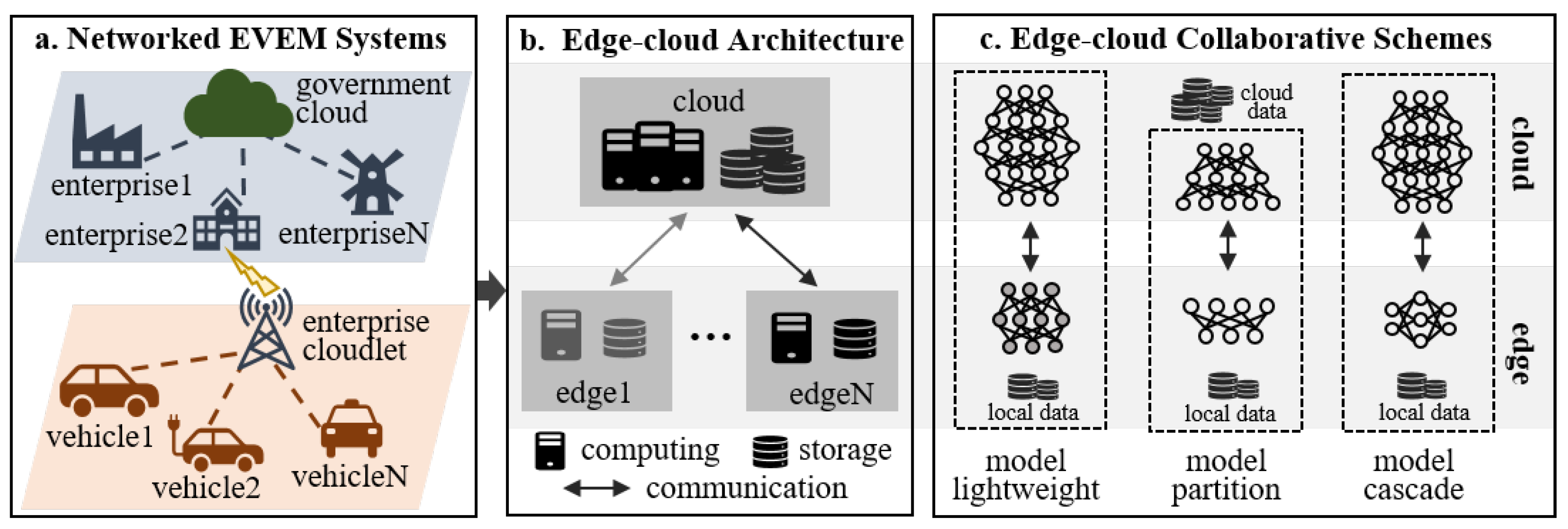

5. Edge-Cloud Collaborative System Architecture of iEVEM

5.1. EVEM Systems

5.2. Edge-Cloud Collaborative Solution

5.2.1. Edge-Cloud Collaborative Storage

5.2.2. Edge-Cloud Collaborative Computing

- Model Lightweight involves deploying an entire small and efficient model directly on edge devices. In such scenarios, edge devices can independently accomplish tasks without relying on cloud resources, ensuring prompt and robust responses even under poor communication conditions (e.g., vehicles performing in-situ energy-efficient route planning while traveling through a tunnel with limited connectivity). To achieve such lightweight models, techniques such as model distillation, pruning, and quantization merit further exploration, as they enable the reduction of model complexity while maintaining sufficient accuracy for real-time applications.

- Model Partition refers to the strategy of splitting parts of a large-scale model between the cloud and edge devices For example, energy component fault diagnosis using a GNN, the first few GNN layers are executed at vehicles for extracting shallow features (e.g., local anomalies in voltage or current). The extracted features are then sent to the cloud, where the remaining layers of GNN are carried out to perform deeper fault diagnosis, such as identifying root causes. Uploading features instead of massive raw data effectively reduces communication time thus response latency. The communication-efficient technologies like traffic compression (e.g., quantization and sampling) are crucial for further minimizing response latency.

- Model Cascade refers to synergy varisized functional models at the edge device and the cloud server in a staged manner. Take EV fault diagnosis as an example, EV can perform a quick self-check using a lightweight local model to detect potential anomalies and provide rapid alerts. If the local model identifies an ambiguous or complex fault, the cloud-based large model can be engaged for a more accurate and comprehensive diagnosis. Dynamic cascading (i.e., determining when to involve the cloud model based on task) is conducive to the trade-off between latency and accuracy, adapting to real-time requirements and system constraints effectively.

6. Case Study: Outlier Detection of EV Energy Consumption

6.1. Scenario

6.2. Experimental Setup

6.2.1. Dataset

6.2.2. Implementation

- For data intelligence implementation, domain knowledge was embedded in both feature engineering and algorithm construction to enhance accuracy and interpretability. First, 74 attributes were selected from the original 638 features based on expert experiences, with empirically irrelevant attributes to energy consumption (e.g., seat angle) being systematically eliminated. Besides, 49 additional features (e.g., acceleration derived from velocity and time) were constructed based on 74 attributes with essential physical and statistical laws. Then, referring to the business understanding, a two-step algorithm was constructed, comprising a rational energy consumption estimation sub-task with extreme gradient boosting and outlier detection sub-task with Gaussian distribution instead of conventional unsupervised one-step methods [41]. This structured approach ensures better alignment with the practical needs of energy consumption analysis and outlier detection.

- For system implementation, an edge-cloud collaborative prototype was constructed with a Jetson Nano serving as the edge device (representing the EV’s on-site computer) and an NVIDIA 2080 Ti acting as the cloud server (representing the enterprise cloudlet). The edge-cloud communication was configured with a 10Mbps bandwidth, adhering to the LTE standard [24], to simulate realistic network conditions. In this setup, model cascade was employed for efficient edge-cloud collaboration. Specifically, the rational energy consumption estimation task was deployed on the edge device to process local data and minimize the need for massive raw data uploads, thereby reducing bandwidth usage. The cloud server, in turn, aggregated the energy consumption deviations reported by multiple edge devices and performed centralized outlier detection using Flink CEP. This collaborative architecture ensures a balance between local processing efficiency and cloud-level computational scalability, meeting the requirements of real-time and large-scale EVEM.

6.2.3. Metrics

- For evaluating the general performance of iEVEM, the area under the curve (AUC) [41] is adopted as a primary indicator of reliability, which is a widely recognized metric to measure classification performance, particularly in scenarios involving an imbalance between positive and negative samples. Note that the closer the AUC to 1 indicates superior performance. Besides, the E2E latency is utilized as a critical metric for reflecting efficiency, where it denotes the response time from data generation to results obtained, representing the system’s ability to process and respond in a timely manner.

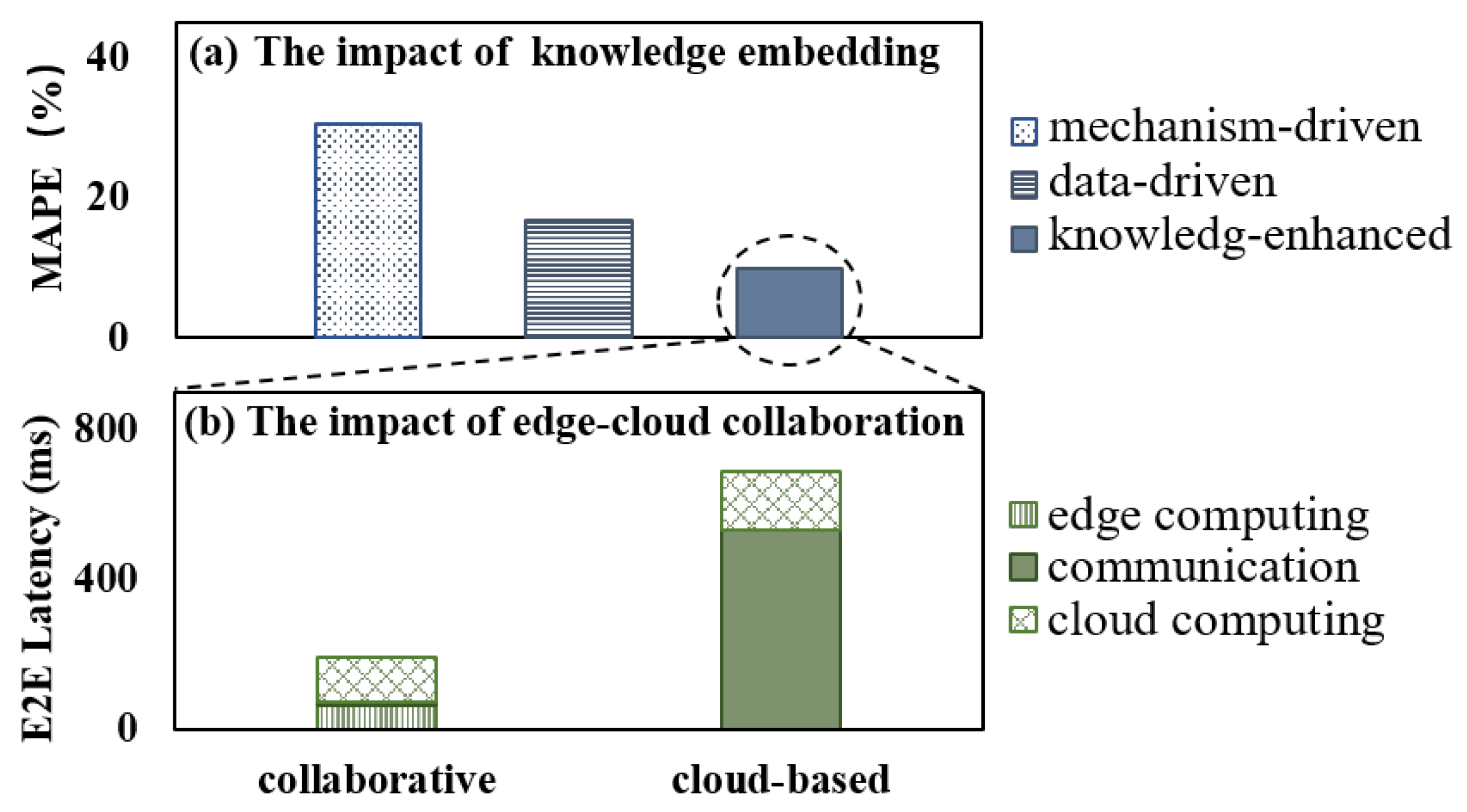

- For evaluating the effectiveness and necessity of iEVEM components, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) [42], indicating the energy consumption estimation precision, is used for reflecting reliability. A lower MAPE value reflects higher estimation accuracy, which is critical for ensuring dependable EVEM. Additionally, the E2E latency is also applied to compare the efficiency of different deployment schemes.

6.2.4. Comparatives

6.3. Main Results

6.3.1. The General Performance

6.3.2. Ablation Experiments

- The Impact of Knowledge-enhanced Approach. We evaluated the impact of data intelligence architecture by the MAPE of rational energy consumption estimation with different data processing and analysis, i.e., mechanism-driven and data-driven methods. The mechanism-driven method is built upon vehicle dynamics referring to [42], i.e., an analytical formulation of vehicle velocity and road grade. The data-driven method is constructed on the same model as iEVEM but without knowledge-enhanced feature engineering, i.e., all data dimensions are utilized. Results are shown in Figure 4a, iEVEM outperforms comparatives in terms of MAPE. Specifically, the knowledge-enhanced method achieves a MAPE of 9.9%, which is substantially lower than the mechanism-driven method’s 13% and the data-driven method’s 12%. It manifests that the knowledge-enhanced approach is conducive to more reliable EVEM.

- The Impact of Edge-cloud Collaborative Deployment. We evaluated the impact of edge-cloud collaborative system architecture on the E2E latency of outlier detection with conventional cloud computing. Shown in Figure 4b, the E2E latency of iEVEM is significantly lower where the identical two-step model is adopted. Specifically, the E2E latency of edge-cloud collaborative deployment is approximately 185ms, which is significantly lower compared to the 685ms observed in the cloud-based deployment. It is worth noting that the collaborative scheme reduces traffic more than compared to the cloud-based scheme. The reduction is attributed to the transformation of raw data into energy consumption values at the edge of proposed two-step model. Hence, the edge-cloud collaboration can effectively reduce the traffic and thus E2E latency, enabling achieving efficient EVEM.

7. Open Issues

- Multimodal Data Fusion for EVEM: In addition to the structured data discussed, incorporating broader and more diverse data modalities [25] should be considered to further enhance the effectiveness and accuracy of intelligent EVEM. For instance, integrating visual data and point-cloud data of the road environment can provide richer contextual information, facilitating more precise vehicle energy consumption modeling and prediction. Developing efficient approaches for subtle multimodal data fusion remains a critical challenge.

- Automatic EVEM Knowledge Embedding: A simple attempt at knowledge-enhanced modeling is proven to be effective in this article. However, automated knowledge embedding is essential for handling the vast, diverse, and ever-changing EVEM knowledge. For example, integrating new findings in battery materials or regularly revised energy management standards will require a systematic and automated approach. Nevertheless, achieving such a unified, automatic, and scalable knowledge embedding mechanism poses significant technical challenges and demands further investigation.

- Dynamic Resource Management of EVEM Systems: Given the dynamic and often unpredictable nature of EVEM system resources (e.g., vehicle-to-cloud communication may degrade significantly inside tunnels or during network congestion), developing an agile platform for dynamic resource and scheme management is critical. For example, such a platform could enable seamless switching from in-situ energy-efficient route planning to cloud-based solutions when exiting tunnels or encountering better network conditions. Addressing this issue effectively will require novel strategies to adapt EVEM operations to varying resource availability in real-time.

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heidrich, O.; Dissanayake, D.; Lambert, S.; Hector, G. How cities can drive the electric vehicle revolution. Nature Electronics 2022, 5, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, G. Benefits of electric vehicle adoption. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2023, 4, 432–432. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, M.; Nanni, M.; Pappalardo, L. Gross polluters and vehicle emissions reduction. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, I.; Ozpineci, B.; Islam, M.S.; Gurpinar, E.; Su, G.J.; Yu, W.; Chowdhury, S.; Xue, L.; Rahman, D.; Sahu, R. Electric drive technology trends, challenges, and opportunities for future electric vehicles. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberz, M.; Hahnel, U.J.; Brosch, T. Counteracting electric vehicle range concern with a scalable behavioural intervention. Nature Energy 2022, 7, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, Z.; Dorrell, D.G.; Li, W.; Sauer, D.U. Battery thermal runaway fault prognosis in electric vehicles based on abnormal heat generation and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2022, 37, 8513–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Battery Fault Diagnosis for Electric Vehicles Based on Voltage Abnormality by Combining the Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network and the Equivalent Circuit Model. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2021, 36, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shim, H.G.; Eo, J.S. A machine learning method for ev range prediction with updates on route information and traffic conditions. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022; Vol. 36, pp. 12545–12551. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P.; Parker, R.; Hoque, T.; Cruz, J.; Du, L.; Wang, S.; Bhunia, S. Addressing the range anxiety of battery electric vehicles with charging en route. scientific reports 2022, 12, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchỳ, M.; Vokřínek, J.; Jakob, M. Multi-Objective Electric Vehicle Route and Charging Planning with Contraction Hierarchies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling; 2024; Vol. 34, pp. 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg, S.; Dressler, F. Reducing waiting times at charging stations with adaptive electric vehicle route planning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2022, 8, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiari, J.; Olaverri-Monreal, C. Uncertainty-Aware Vehicle Energy Efficiency Prediction Using an Ensemble of Neural Networks. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2023, 15, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, W.; Xia, R.; Zhou, T.; Niu, P.; Peng, B.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Ma, Z.; Gu, X.; et al. Energy forecasting with robust, flexible, and explainable machine learning algorithms. AI Magazine 2023, 44, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, Z.; Chen, G. Edge intelligence for plug-in electrical vehicle charging service. IEEE Network 2021, 35, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turjman, F.; Altrjman, C. Enhanced Medium Access for Traffic Management in Smart-Cities’ Vehicular-Cloud. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2021, 13, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, D.; Wu, C. Distributed machine learning through heterogeneous edge systems. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; Vol. 34, pp. 7179–7186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Xu, C.; Chang, Z.; Mumtaz, S.; Rodriguez, J. BEGIN: Big data enabled energy-efficient vehicular edge computing. IEEE Communications Magazine 2018, 56, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.J.; Toril, M.; Oliver, P.; Luna-Ramirez, S.; Garcia, R. Big data analytics for automated QoE management in mobile networks. IEEE Communications Magazine 2019, 57, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Kisacikoglu, M.C.; Liu, C.; Singh, N.; Erol-Kantarci, M. Big data analytics for electric vehicle integration in green smart cities. IEEE Communications Magazine 2017, 55, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, D.; Oh, J.; Jeon, I.; Moon, J.; Lee, M.; Rho, S. BiGTA-Net: A Hybrid Deep Learning-Based Electrical Energy Forecasting Model for Building Energy Management Systems. Systems 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, K.; Mei, J.; Qian, Y. Ultra-reliable and low-latency communications for connected vehicles: Challenges and solutions. IEEE Network 2020, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdak, R.; Dorri, A.; Vilathgamuwa, M. A trusted and privacy-preserving internet of mobile energy. IEEE Communications Magazine 2021, 59, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamfroush, H. Resource-aware Federated Data Analytics in Edge-Enabled IoT Systems. In Proceedings of the AAAI Symposium Series; 2024; Vol. 3, pp. 305–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Rashid, M.M.; Barnes, S.; Hassanain, E. IoEV-Chain: A 5G-based secure inter-connected mobility framework for the Internet of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Network 2020, 34, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; You, Y.; Meng, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Stroe, D.I. Lithium-ion batteries SOH estimation with multimodal multilinear feature fusion. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2023, 38, 2959–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Chow, M.Y.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Luo, H.; Yin, S. A data-model interactive remaining useful life prediction approach of lithium-ion batteries based on PF-BiGRU-TSAM. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2023, 20, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; et al. Routing optimization of electric vehicles for charging with event-driven pricing strategy. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2021, 19, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; et al. Mobile Charging Services for the Internet of Electric Vehicles: Concepts, Scenarios, and Challenges. IEEE Vehicle Technology Magazine. 2023, 18, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Lee, C.F.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Wik, T. Predicting electric vehicle energy consumption from field data using machine learning. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, M.E.; Bruder, D.D.; Huemiller, E.D.; Rinker, T.J.; Bracey, J.T.; Sekol, R.C.; Abell, J.A. A review of research needs in nondestructive evaluation for quality verification in electric vehicle lithium-ion battery cell manufacturing. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 561, 232742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.; Li, L. Data-driven-aided strategies in battery lifecycle management: prediction, monitoring, and optimization. Energy Storage Materials 2023, 59, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Guan, D. Value chain carbon footprints of Chinese listed companies. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hao, Z.; Cai, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Study on the life cycle assessment of automotive power batteries considering multi-cycle utilization. Energies 2023, 16, 6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakanti, A.K.; Rao, S. Charging Station Planning for Electric Vehicles. Systems 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, H.; Lu, N.; Zhan, X.; Xu, E.; Yuan, Q. Lane Changing in a Vehicle-to-Everything Environment: Research on a Vehicle Lane-Changing Model in the Tunnel Area by Considering the Influence of Brightness and Noise Under a Vehicle-to-Everything Environment. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2023, 15, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Feng, C.; Xie, X.; Shi, B.; Lu, H.; Lv, Y.; Yang, M.; Niu, Z. Multi-Sensor Fusion and Cooperative Perception for Autonomous Driving: A Review. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2023, 15, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.; Munir, A.; Behzadan, V. Security and Privacy Issues in Intelligent Transportation Systems: Classification and Challenges. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2021, 13, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwade, A.; Haselrieder, W.; Leithoff, R.; Modlinger, A.; Dietrich, F.; Droeder, K. Current status and challenges for automotive battery production technologies. Nature Energy 2018, 3, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J. Prognostic health condition for lithium battery using the partial incremental capacity and Gaussian process regression. Journal of power sources 2019, 421, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; He, J.; Zhao, J.; Xie, J. A Federated Mixed Logit Model for Personal Mobility Service in Autonomous Transportation Systems. Systems 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Hu, X.; Huang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Y. Adbench: Anomaly detection benchmark. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 32142–32159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z. Energy consumption analysis and prediction of electric vehicles based on real-world driving data. Applied Energy 2020, 275, 115408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Real-world Data (R=1%,D=5) |

Deviation Degree (R=1%) | Injection Ratio (D=5) | E2E Latency (ms) | |||

| Hard (D=3) | Easy (D=7) | Hard (R=0.01%) | Easy (R=10%) | |||

| KNN | 0.8195 | 0.8181 | 0.8219 | 0.7851 | 0.8372 | 27560 |

| CBLOF | 0.7304 | 0.7147 | 0.7402 | 0.6353 | 0.7854 | 568 |

| IForest | 0.7185 | 0.6755 | 0.7447 | 0.6431 | 0.7865 | 694 |

| ECOD | 0.5303 | 0.5184 | 0.5484 | 0.5297 | 0.5389 | 9651 |

| DSVDD | 0.5000 | 0.4996 | 0.5000 | 0.4998 | 0.5000 | 675 |

| iEVEM | 0.9644 | 0.9467 | 0.9748 | 0.9591 | 0.9668 | 185 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).