1. Introduction

The global shift from traditional fossil fuels to renewable energy sources marks a pivotal step in order to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). In particular, toward sustainable transportation, the key component is the transition to the electric vehicles (EVs) as they offer a cleaner alternative to internal combustion engine vehicles [

1]. However, despite their growing adoption, several challenges prevent their widespread use, such as driving range, charging time, battery cost, and battery weight [

2].

Energy consumption plays a crucial role in the operation of electric vehicles, as it affects their efficiency, the planning of their routes, and the scheduling of refueling [

3]. Energy consumption in EVs is highly dynamic and its influenced by factors such as driving patterns, traffic conditions, weather, and vehicle-specific metrics. Hence, one of the most prominent challenges pertains to the inaccuracy in the prediction of energy consumption under varied driving conditions [

4]. Accurate energy consumption forecasts can help drivers better manage their vehicle’s performance, contributing to more efficient driving and energy usage [

5] and in general, to optimize of the overall use of electric vehicles. Hence, poor predictions of energy consumption result in inefficient charging infrastructure, higher range anxiety for the driver, and inefficient energy management strategies.

Several machine learning models have been employed to improve prediction accuracy, however, existing approaches often fail to capture the temporal dependencies and variability inherent in real-world scenarios [

6]. For instance, many models rely on static datasets that do not account for the fluctuating energy demands caused by stop-and-go traffic, elevation changes, or extreme weather conditions. This limitation not only reduces the reliability of predictions but also undermines user confidence in EVs, slowing their adoption.

Energy consumption forecasting, particularly for long-term predictions, is essential for effective infrastructure planning [

7]. Accurate forecasting is crucial for optimizing the placement of charging stations and managing energy distribution efficiently. As the EV market continues to expand, existing infrastructure will face increasing strain, necessitating the development of reliable energy consumption models [

8]. Addressing these challenges is fundamental to ensuring the long-term viability of electric vehicles and facilitating a seamless transition toward sustainable transportation.

In this article, a novel framework for EV energy consumption forecasting is proposed leveraging advanced machine learning models and innovative data preprocessing techniques containing statistical analysis. More specifically, the suggested approach using a publicly available dataset addresses the energy consumption forecasting problem by i)incorporating feature engineering to capture vehicle-specific metrics and environmental conditions, ensuring adaptability to diverse real-world scenarios, ii)leveraging statistical analysis of the extracted features, and iii)employing machine learning algorithms such as XGBoost, Random Forest, and regression-based models. The purpose of the current research is to deliver high-accuracy predictions that support sustainable transportation and efficient energy management.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides a review of related work, highlighting current advancements and limitations in EV energy consumption forecasting.

Section 3 details the methodology, including dataset preprocessing, feature engineering, and model implementation.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and discusses their implications. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future directions.

2. Related Work

In recent years, the rise of EVs has driven extensive research into optimizing their energy consumption. This has led to the development of machine learning models for predicting energy usage, along with applications designed to help users manage their vehicles more efficiently. In the following paragraphs representative research studies focusing on energy consumption forecasting are presented.

Huang et al. [

9] introduced a novel approach to understanding the factors influencing EV energy consumption. The study addresses a key limitation of previous research studies, which primarily examined statistical correlations without exploring causal relationships. By applying double/debiased ML combined with bootstrap-of-little-bags inference, the authors inferred how various factors affect energy consumption.

Petkevicius et al. [

10] tackled the growing challenge of EV energy consumption prediction, particularly in long-distance route planning. The authors proposed a two-tier architecture for forecasting both energy consumption and travel time. The first tier consists of a routing and travel-time prediction subsystem that generates a suggested route and predicts speed variations. The second tier predicts energy consumption based on speed profiles, weather conditions, and road slope.

Hua et al. [

11] proposed a method for accurately estimating EV energy consumption, emphasizing its importance for optimizing charging station deployment, promoting eco-friendly driving practices, and extending EV range. Their approach comprises three key components: segmentation-assisted trajectory granularity, knowledge transfer from internal combustion engine/hybrid electric vehicles to EVs, and time-series estimation using a bidirectional recurrent neural network.

Athanasakis et al. [

12] introduced a novel methodology for forecasting the State of Charge (SoC) in EVs. Their approach integrates lightweight regression-based models with feature engineering to enhance SoC prediction accuracy. To validate the effectiveness of their methodology, experiments were conducted on both a private dataset of automated EVs and a public EV dataset. The results demonstrated the efficiency of their lightweight approach and its superiority over more computationally intensive methods, such as deep learning (DL) models and gradient boosting algorithms.

Chen et al. [

13] addressed the challenges of energy consumption estimation in EVs, particularly in scenarios where certain features are unavailable. To account for uncertainties introduced by transient factors, the authors implemented an XGBoost prediction model, which outperformed other approaches in point-value energy consumption estimations.

Tang et al. [

14] presented a predictive energy management approach that optimizes energy consumption for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles using travel route data. Their methodology incorporates battery temperature as an optimization factor in the energy cost function and employs an extreme learning machine as a short-term speed predictor. By training the speed predictor on historical real-world speed data and integrating travel route information, the study achieved higher forecasting accuracy than traditional driving cycles.

Polymeni et al. [

15] developed a machine learning-based approach for energy consumption forecasting in fuel cell electric vehicles. Their methodology incorporated techniques from three distinct machine learning families—statistical-based models, ensemble methods, and deep learning. Using an artificial dataset of hydrogen vehicles generated through the Future Automotive Systems Technology Simulator [

16] and considering real-world booking records from an on-demand public transportation service in the Geneva Canton region, they achieved high forecasting accuracy, with errors remaining below 10%.

This work distinguishes itself from related studies that focus solely on forecasting energy consumption or State of Charge (SoC) by introducing a novel methodology that leverages machine learning models—including Random Forest, XGBoost, and regression-based techniques—applied across multiple time intervals (1-minute, 5-minute, and 10-minute) for energy consumption prediction. By capturing temporal dependencies at different time resolutions, the proposed approach enhances predictive model robustness. Additionally, the methodology employs diverse strategies for selecting input variables, incorporating historical energy consumption, external vehicle-related features, or a combination of both, representing a novel contribution to the field. Unlike previous studies, this approach systematically evaluates the impact of exogenous factors such as elevation, vehicle speed, acceleration, and air conditioning power on energy consumption, ensuring a more comprehensive analysis of EV energy dynamics. Furthermore, the statistical analysis of these contributing factors, as presented in this study, has not been previously explored in related research.

3. Dataset Description

Zhang et al. [

17] introduced the extended Vehicle Energy Dataset (eVED), an enhancement of the well-established Vehicle Energy Dataset [

18], designed to provide more accurate vehicle trip data for large-scale energy consumption analysis. The eVED dataset ensures data sufficiency for machine learning applications by incorporating precise GPS coordinates and enriched features. It includes a comprehensive set of variables that capture both internal vehicle dynamics and external environmental factors, essential for understanding vehicle behavior and traffic patterns. The dataset consists of multiple electric vehicles with diverse operational characteristics, and for this study, three EVs (vehicle 10, vehicle 455, and vehicle 541) were utilized. Structurally, eVED is formatted as a time series, representing vehicle routes and their corresponding data over time.

Compared to other datasets commonly used in energy consumption research, such as simulated datasets [

15] or aggregated trip-level records [

19,

20], eVED offers a higher temporal resolution by capturing real-world driving conditions at minute-level intervals. This fine granularity enables detailed temporal analysis and improves machine learning models’ ability to capture short-term fluctuations in energy usage. Key features influencing energy consumption predictions include vehicle speed, air-conditioning power, heater power, and smoothed elevation data. These variables provide insights into both vehicle performance and the external factors affecting energy consumption. As a result, the eVED dataset serves as a valuable and diverse resource for robust energy consumption modeling across various driving conditions and vehicle types.

3.1. Preprocessing and Data Preparation

To effectively utilize the dataset and ensure its compatibility with the selected predictive algorithms, several key preprocessing steps were applied, constituting one of the main novelties of this study. As previously mentioned, the dataset includes three EVs: vehicle_455, vehicle_10, and vehicle_541. Initially, a separation based on vehicle ID was performed to distinguish between the three electric vehicles. Additionally, the original timestamps, recorded in milliseconds, were aggregated into one-minute, five-minute, and ten-minute intervals, generating three distinct datasets for each vehicle to facilitate the calculation of energy consumption and acceleration.

Following the initial data filtering, a statistical analysis of fundamental metrics was conducted. This analysis, inspired by relevant literature [

21,

22], aimed to better capture variable distributions. By computing and recording various statistical measures—including mean, median, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation for each feature—the dataset’s structure and key characteristics were more thoroughly examined.

Standardizing the raw timestamps into consistent minute-based intervals ensured uniform time series data across all vehicles. Within these intervals, feature-specific metrics were recalculated, providing a more detailed and accurate temporal representation of the dataset. The described preprocessing approach is essential for maintaining consistency across the time series while also improving the accuracy and reliability of the energy consumption predictions. Table 1 shows the initial variables of the dataset and Table 2 depicts the dataset after the preprocessing procedure.

Table 1.

eVED Dataset Raw Data Variables.

Table 1.

eVED Dataset Raw Data Variables.

| Variable |

Type |

Description |

| DayNum |

Numeric |

Numerical representation of the day |

| VehId |

Numeric |

Unique vehicle identifier |

| Trip |

Numeric |

Identifier for each trip |

| Timestamp (ms) |

Numeric |

Time recorded in milliseconds |

| Latitude, Longitude |

Numeric |

Geographical coordinates |

| Vehicle Speed (km/h) |

Numeric |

Speed of the vehicle |

| OAT (°C) |

Numeric |

Outside ambient temperature |

| AC Power (W), Heater Power (W) |

Numeric |

Power usage of AC and heater |

| HV Battery Current (A) |

Numeric |

High-voltage battery current |

| HV Battery SOC (%) |

Numeric |

State of charge of the battery |

| HV Battery Voltage (V) |

Numeric |

Voltage of the battery |

| Elevation Raw/Smoothed (m) |

Numeric |

Raw and processed elevation values |

| Gradient |

Numeric |

Road slope gradient |

| Energy Consumption (kWh) |

Numeric |

Energy used per trip |

| Matched Latitude Longitude |

Numeric |

Matched GPS coordinates |

| Match Type |

Categorical |

Type of GPS match |

| Speed Limit (km/h) |

Numeric |

Road speed limit |

| Speed Limit (Direction) (km/h) |

Numeric |

Speed limit considering direction |

Table 2.

eVED Dataset Processed Data Variables.

Table 2.

eVED Dataset Processed Data Variables.

| Variable |

Type |

Description |

| 1min Interval |

Numeric |

Time interval in minutes |

| Energy Consumption (kWh) |

Numeric |

Total energy consumed in the interval |

| Acceleration (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Statistical measures of vehicle acceleration |

| Speed (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Statistical measures of vehicle speed |

| OAT (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Outside ambient temperature statistics |

| AC Power (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Air conditioning power usage statistics |

| Heater Power (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Heater power usage statistics |

| Elevation (Mean, Max, Min, Median, Std) |

Numeric |

Statistical measures of elevation |

4. Methodology

In this paper, an energy forecasting framework for EVs is presented, aiming to provide accurate predictions and insights about energy usage. Considering their particular high performance to different prediction problems [

5,

15,

23,

24,

25,

26], Random Forest [

27], XGBoost [

28] and regression-based algorithms [

29] were selected in the suggested methodology. The selection of ML algorithms from different families is in accordance with the literature [

15] for generalization purposes of the proposed methodology.

4.1. Machine Learning Models

As mentioned above, XGBoost, a Regression-based model, and a Random Forest model were implemented. Wang et al. [

30] highlighted the Random Forest algorithm as a promising tool for energy prediction, demonstrating stability, strong fitting capabilities, and the feasibility of homogeneous ensemble learning in energy forecasting. The Random Forest model, an ensemble learning method, was selected for its ability to reduce overfitting while maintaining accuracy through multiple decision trees. It was trained using preprocessed features such as vehicle speed, air-conditioning power, heater power, acceleration, and smoothed elevation, aggregated into one-minute, five-minute, and ten-minute intervals. This model effectively captured nonlinear relationships between these features and energy consumption, ensuring reliable predictions even with a high-dimensional feature space.

XGBoost, a gradient boosting algorithm, was also employed in this study due to its efficiency in handling large datasets and its iterative learning process, which enhances predictive performance. XGBoost includes built-in regularization to prevent overfitting, making it particularly suitable for datasets with diverse driving patterns. The model was trained using the same feature set and time intervals and underwent hyperparameter tuning, optimizing parameters such as learning rate, maximum tree depth, and the number of boosting rounds. Ma et al. [

31] demonstrated the superiority of XGBoost for wind power forecasting, showcasing its effectiveness in handling complex time-series data. Additionally, XGBoost efficiently optimizes hyperparameters using techniques like the Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) [

32], ensuring robust and precise results. With these advantages, XGBoost is well-suited for forecasting the energy consumption of electric vehicles in real-world applications.

A third model used in this study is Dynamic Linear Regression, a well-established technique known for its simplicity and interpretability. This regression model, widely employed in predictive analysis for time-series data [

4], integrates lagged features of both the target variable (energy consumption) and external factors such as acceleration, vehicle speed, and air-conditioning usage. By incorporating historical patterns through a lagged structure, the model captures temporal dependencies and the influence of exogenous factors on energy usage. The model’s simplicity allows for easy hyperparameter tuning and residual analysis, enabling the detection of temporal patterns or anomalies. As a result, Dynamic Linear Regression serves as a useful baseline for identifying and quantifying the dynamic factors affecting energy consumption in electric vehicles.

Additionally, an AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model was deployed. ARIMA has proven effective in handling complex datasets by capturing temporal dependencies within time-series data. As discussed by Moslemi et al. [

33], ARIMA primarily focuses on autoregressive and moving average components but can also handle non-stationary data through differencing, making it a suitable choice for energy consumption forecasting.

4.2. Different Input Space

As mentioned in the Introduction, three different approaches were followed regarding the input space. Specifically, to capture the temporal dependencies in energy consumption, three distinct feature sets were implemented:

- 1.

Energy Consumption Lags Only: This configuration relies solely on past values of energy consumption to predict future consumption, identifying auto-correlations within the dataset [

34].

- 2.

Feature Lags Only: his setup includes only lagged values of relevant features (e.g., vehicle speed, air-conditioning, and environmental factors), excluding past energy consumption values. This approach evaluates the influence of external factors on energy consumption over time [

35].

- 3.

Combined Lags: This configuration integrates both energy consumption lags and feature lags, providing a comprehensive analysis of the relationships between past consumption patterns and vehicle dynamics.

These configurations were designed to assess the predictive strength of different feature structures and identify the most effective approach for modeling temporal energy consumption patterns. For each model, three distinct versions were implemented to examine the relationship between the target variable (energy consumption at one-, five-, and ten-minute intervals) and additional features, as well as their impact on prediction accuracy.

For the XGBoost model, three distinct versions were developed: i) Learnable Edge Collaborative Filtering (LECF) [

36] that incorporates lags from both the target variable (energy consumption) and external vehicle features, ii) a version utilizing only historical values of energy consumption, and iii) a version considering only historical values of external features. A similar approach with XGBoost was followed for the Random Forest algorithm to implement these three different configurations. For the regression-based models, a Dynamic Regression model was implemented to i) capture historical values from both energy consumption and external features (representing the LECF version) ii) capture only exogenous features (analogous to the LF version). Finally, an ARIMA model was deployed to focus exclusively on historical energy consumption values, without incorporating exogenous variables.

4.3. Configurations

To optimize model performance using the eVED dataset, a grid search was employed to identify the most suitable hyperparameters for each model. Grid search [

37] is an exhaustive search technique that evaluates multiple combinations of hyperparameters, ensuring the selection of an optimal configuration to enhance predictive accuracy.

For the Random Forest model, 300 decision trees were selected to enhance robustness and reduce variance. The maximum tree depth was set to 20, balancing complexity and generalization, allowing the model to learn patterns without overfitting to the training data. Additionally, the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node was set to 2, ensuring trees grow to their full potential. To guarantee reproducibility, a fixed random seed was used.

For the XGBoost model, various hyperparameter combinations were tested, with the following configuration proving most effective. The maximum tree depth was set to 3 to prevent overfitting while capturing essential patterns. A learning rate of 0.2 was chosen to balance learning speed and error minimization without overfitting. The number of boosting rounds was set to 300, providing sufficient iterations while incorporating early stopping to prevent overfitting. The objective function was set to minimizing squared error, a common loss function for regression problems. A fixed random seed was used to ensure reproducibility.

For dynamic regression models, an extensive grid search was conducted to determine the optimal lag selection for both the target variable (energy consumption) and exogenous variables such as vehicle speed, acceleration, elevation, and air conditioning. The most effective configuration included up to four lagged values, allowing the model to capture temporal dependencies and the dynamic effects of external factors over time. This approach enabled the model to learn both short-term variations and long-term trends in energy consumption.

A similar hyperparameter tuning approach was applied to the ARIMA model to determine the most suitable configuration for the dataset. After an extensive grid search, an (3,0,1) order was found to be the most effective across different vehicles and datasets. The autoregressive (AR) component of 3 uses three lagged observations of energy consumption to predict future values, effectively capturing dependencies over longer intervals. The differencing order of 0 indicates no differencing was required to achieve stationarity, avoiding unnecessary complexity while maintaining predictive accuracy. The moving average (MA) component of 1 uses a single lagged forecast error to correct future predictions, smoothing short-term fluctuations in energy consumption. Additional hyperparameter tuning was performed to optimize the differencing order and enhance the model’s fit to the dataset’s unique temporal patterns. By focusing on autoregressive components and smoothing forecast errors, the ARIMA model effectively captures energy consumption variations while leveraging historical data. This makes it particularly useful for analyzing temporal patterns, even when external exogenous variables are not considered.

Beyond hyperparameter tuning, lag selection was optimized for each algorithm through an exhaustive search to determine the most suitable lag number for each sub-dataset. This process provided a comprehensive understanding of feature distributions and variability, ensuring each model was tailored to the specific characteristics of the dataset. Finally, the dataset was spitted into training, validation and testing set following a distribution of 60 : 20 : 20 split aligned with the literature [

24,

25]. All models were trained with different number of lags in order to identify the most effective lag number for every model. Lag observation differs from dataset to dataset as three different sub-datasets were utilized for every vehicle (one-minute, five-minute, and ten-minute intervals). The overall methodology is depicted in

Figure 1.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

In order to evaluate the model performance and monitor how they behave in different conditions and different vehicles, the following well-established evaluation metrics were used: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Median Absolute Error (MdAE), and RMSE, along with their normalized versions. The selection of the aforementioned metrics is aligned with the respective literature [

15,

38,

39]. The following formulas show how these metrics are calculated:

where

is the error between the actual and predicted energy consumption values, whereas n is the number of values.

expressing the median error, thus more robust and resilient against outliers compared to

the most stricter metric, as penalizes the big errors more due to the square power

where

y is the vector of the actual energy consumption values

5. Experimental Results

In this paper, we presented an Automated Refueling Service aimed at optimizing energy consumption management for Electric Vehicles (EVs) through predictive analytics and real-time monitoring. By leveraging machine learning algorithms and real-time data collected from vehicle diagnostics, our system successfully provides accurate energy consumption forecasts and refueling notifications, contributing to more efficient fuel usage and enhanced driver convenience.

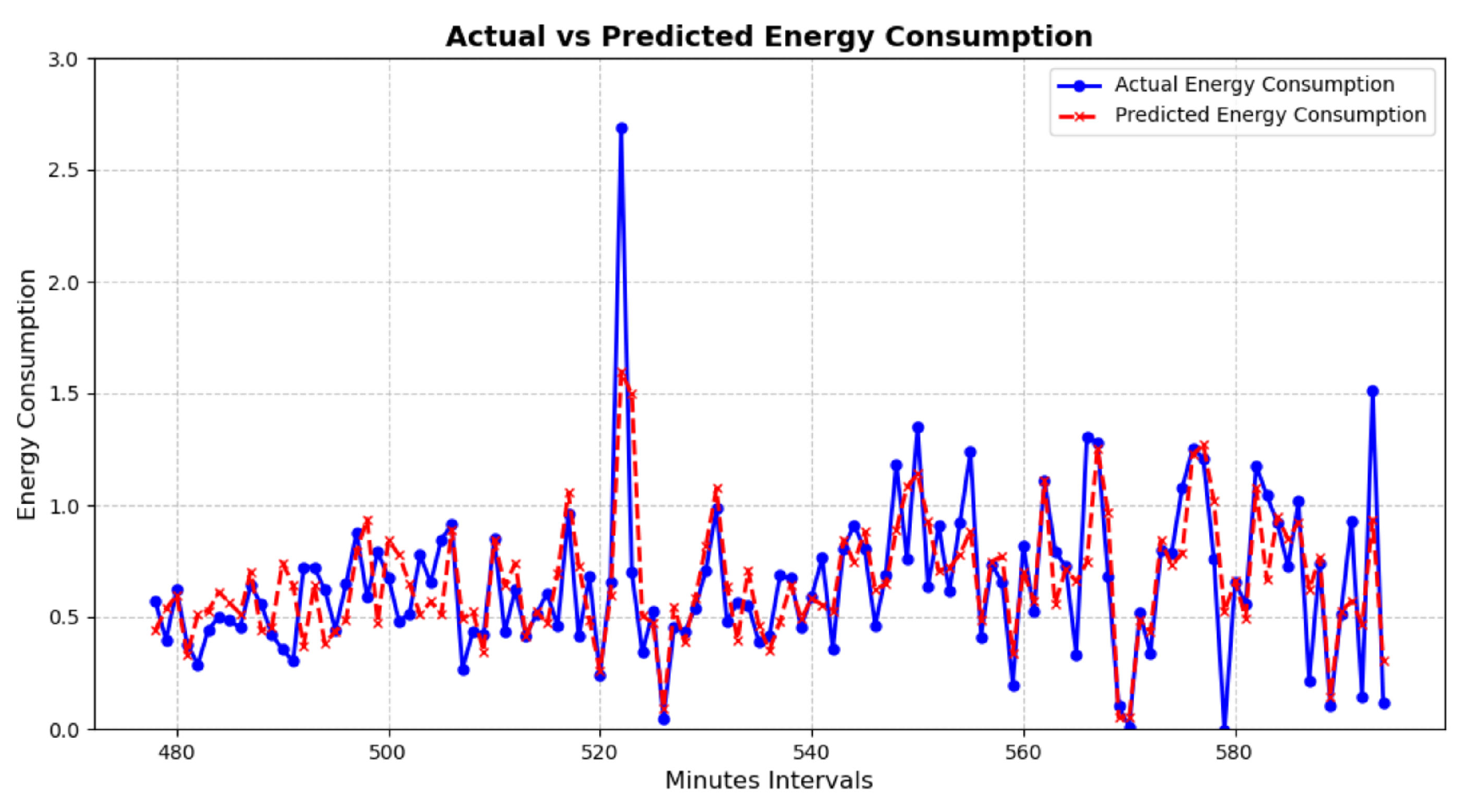

Figure 2.

XGBoost Model LECF, Vehicle 455, 5-minute intervals.

Figure 2.

XGBoost Model LECF, Vehicle 455, 5-minute intervals.

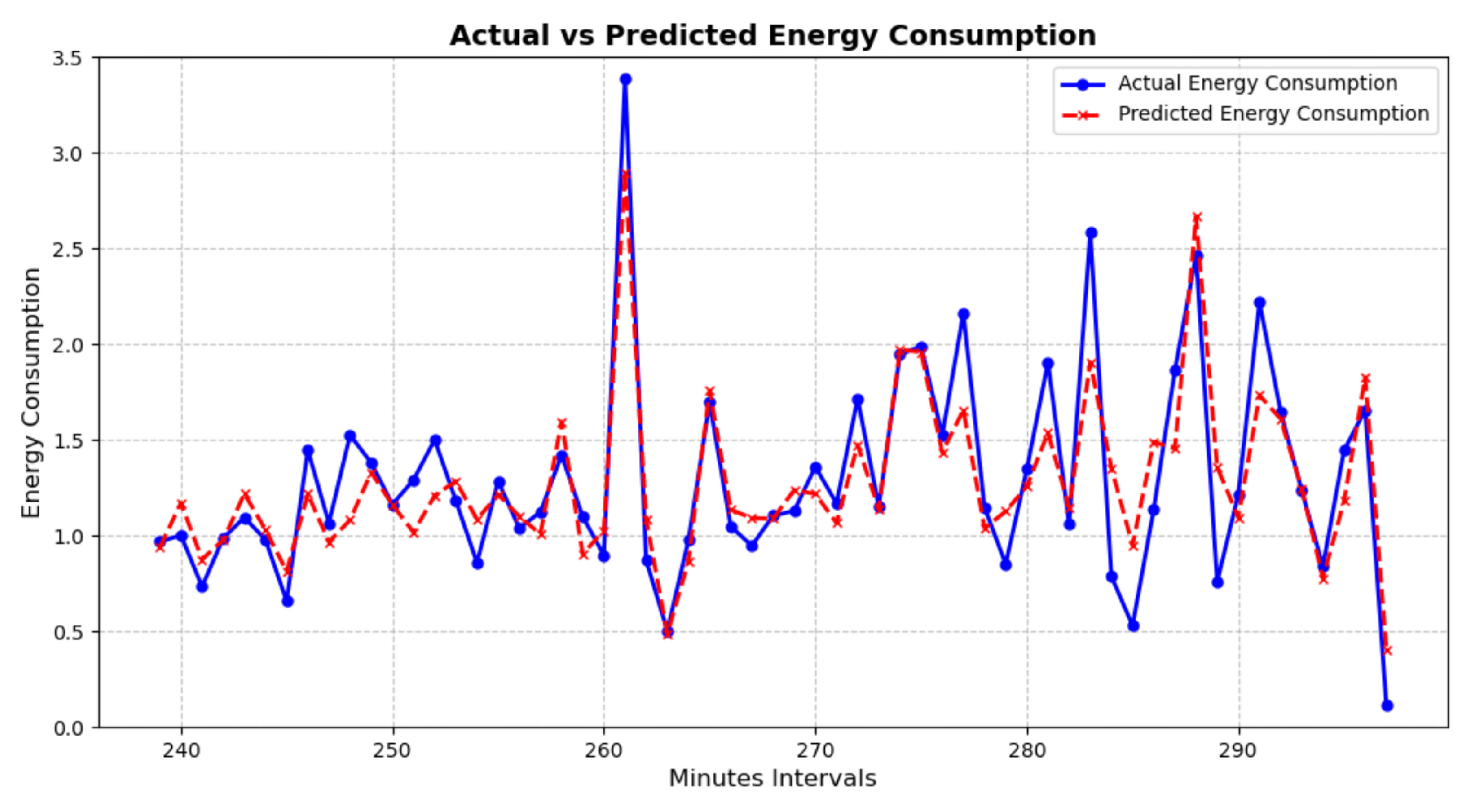

Figure 3.

XGBoost Model LECF, Vehicle 455, 10-minute intervals.

Figure 3.

XGBoost Model LECF, Vehicle 455, 10-minute intervals.

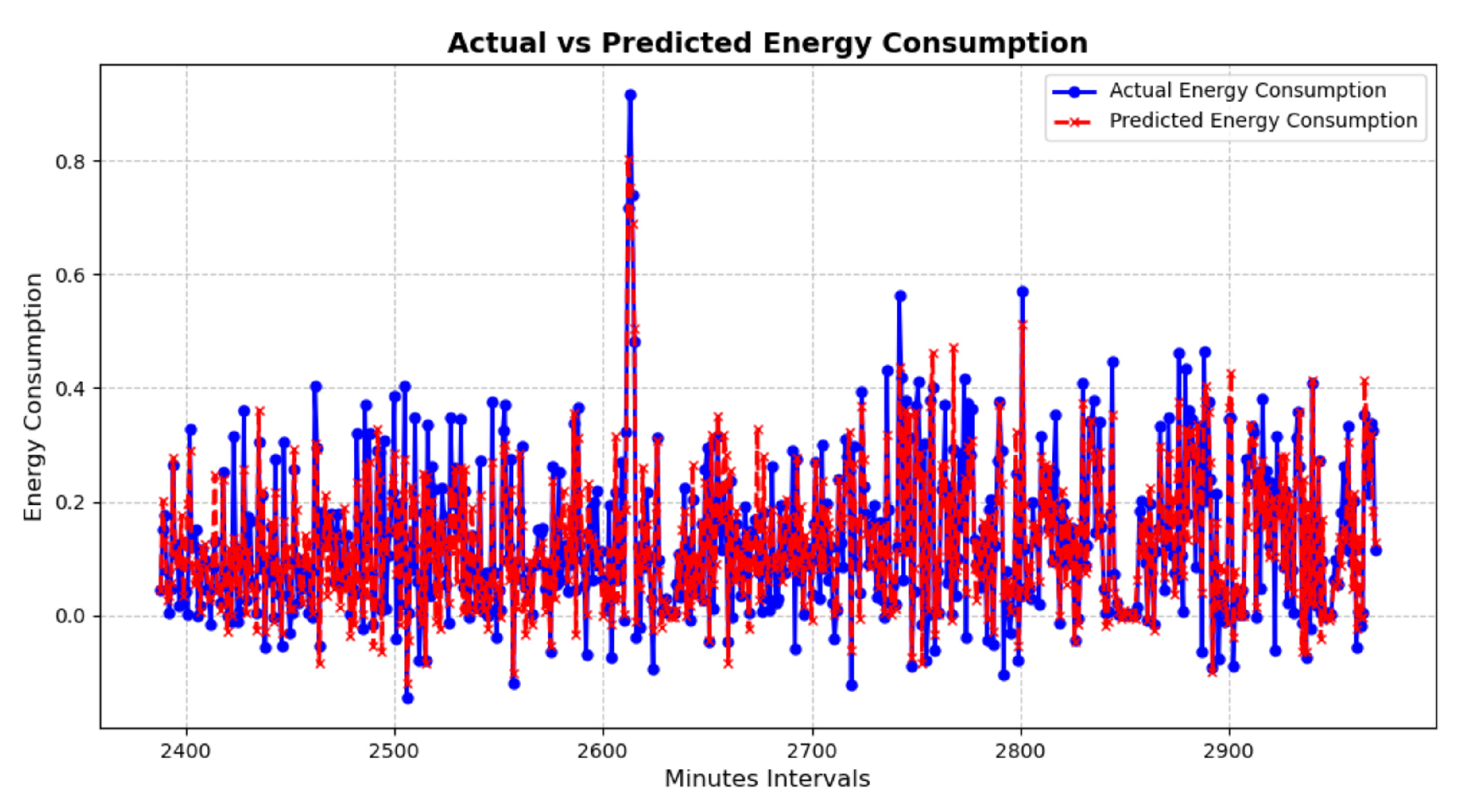

This section aims to provide extensive results of the experiments conducted using XGBoost model, Random Forest (RF) and Dynamic Regression (DR) as well as ARIMA, utilizing every electric vehicle from eVED dataset. As described above, three different sub-datasets for every vehicle were created (1-minute, 5-minute, and 10-minute).

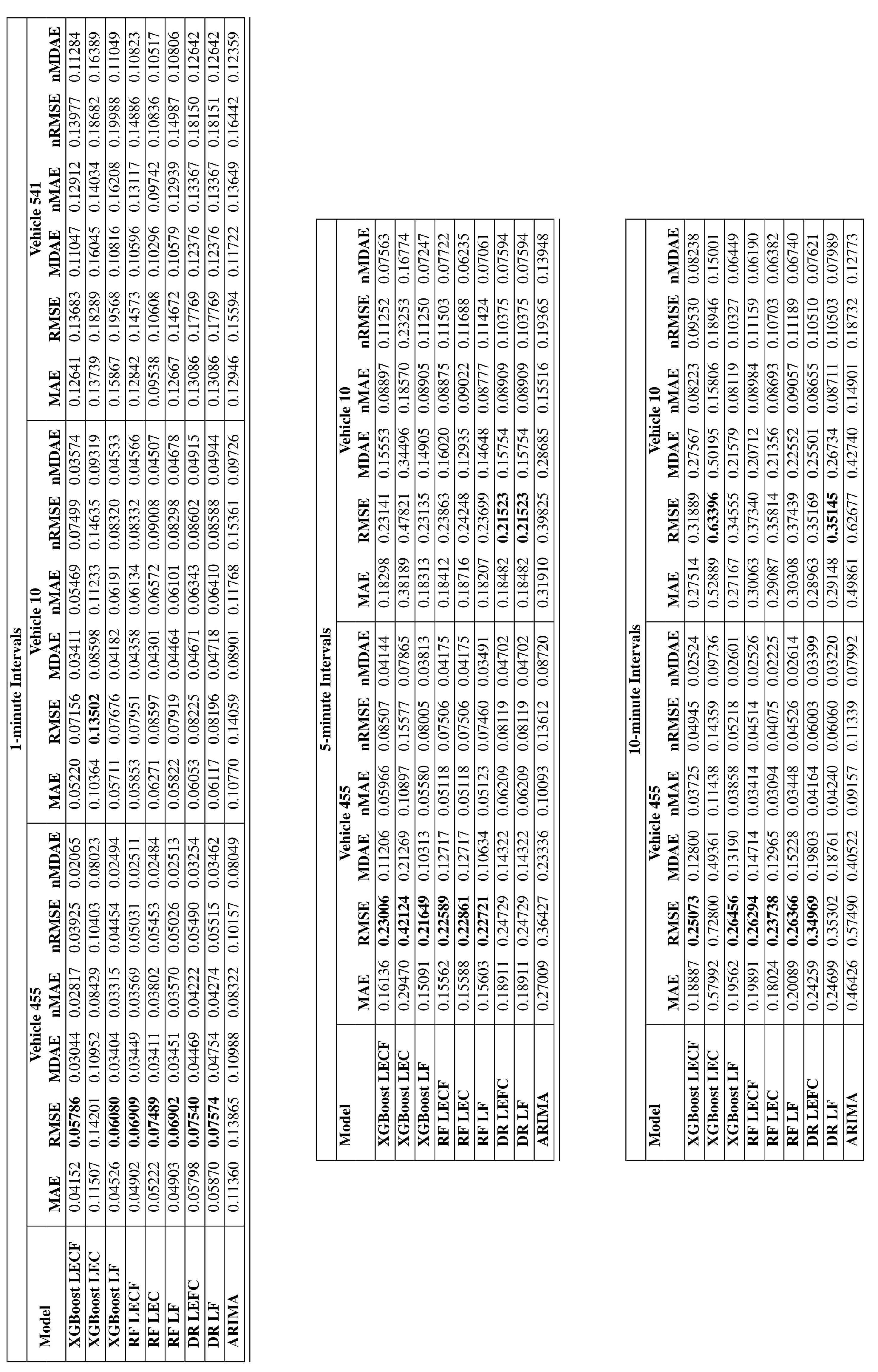

Table 3.

Model Metrics for Each Vehicle at 1-minute, 5-minute, and 10-minute Intervals.

Table 3.

Model Metrics for Each Vehicle at 1-minute, 5-minute, and 10-minute Intervals.

At the 1-minute interval, XGBoost consistently proved to be the best-performing algorithm across vehicles and configurations. For example, in the LECF configuration, XGBoost achieved a MAE of 0.04152, an RMSE of 0.05786, and an nRMSE of 0.03925 for Vehicle 455, demonstrating its capacity to accurately capture short-term variations in energy consumption. This trend was consistent across other vehicles, with Vehicle 10 achieving an RMSE of 0.07156 in the same configuration, significantly better than other models. Random Forest, while robust, exhibited slightly higher errors. For instance, Vehicle 455 under the Random Forest LECF (lags energy consumption and features) configuration recorded an RMSE of 0.06909, which was higher than XGBoost’s performance. Similarly, for Vehicle 10, Random Forest under the LECF configuration achieved an RMSE of 0.07951, reflecting its slightly weaker performance in capturing complex patterns at this short interval. Dynamic Regression (DR) models performed comparably well, particularly for Vehicle 455, where an RMSE of 0.07540 was recorded in the LECF configuration, and for Vehicle 10, an RMSE of 0.06053 was observed. However, DR models generally fell behind XGBoost in accuracy, as seen with Vehicle 541, where DR models recorded higher errors compared to XGBoost. ARIMA, on the other hand, showed mixed results. While it achieved reasonable accuracy for Vehicle 455 with an RMSE of 0.13865, its performance deteriorated for Vehicle 10, where an RMSE of 0.14059 was observed. This inconsistency highlighted ARIMA’s sensitivity to data variability.

At the 5-minute interval, data aggregation resulted in increased errors across all models, but XGBoost maintained its dominance. For instance, in the LF configuration, XGBoost recorded an RMSE of 0.21649 for Vehicle 455, the lowest among all models for this interval. For Vehicle 10, XGBoost LECF achieved an RMSE of 0.23141, showcasing its robustness even at this aggregated level. Random Forest continued to deliver respectable results, though it trailed behind XGBoost. For Vehicle 455, Random Forest LF recorded an RMSE of 0.22721, while for Vehicle 10, its performance was slightly less accurate, with an RMSE of 0.23699. Dynamic Regression models remained competitive but slightly inconsistent. For Vehicle 10, DR models recorded an RMSE of 0.21523 under both LF and LECF configurations, which were comparable to XGBoost but higher than Random Forest in some cases. However, for Vehicle 541, DR models produced higher errors, revealing limitations in handling data variability. ARIMA demonstrated greater variability in its performance, particularly as the interval length increased. While it achieved competitive results for Vehicle 455, with an nRMSE of 0.13612, its accuracy declined for other vehicles at longer intervals. For instance, Vehicle 10 under ARIMA recorded a significantly higher RMSE of 0.19365, highlighting the model’s increased errors and its inherent difficulty in handling aggregated data and extended prediction intervals.

At the 10-minute interval, the loss of granularity further increased the gap between the models. XGBoost continued to dominate, particularly in the LECF configuration, where it achieved an RMSE of 0.25073 for Vehicle 455. This result demonstrated its ability to maintain accuracy even in longer-term predictions. For Vehicle 10, XGBoost recorded an RMSE of 0.31889, highlighting its superior adaptability. Random Forest provided slightly less accurate predictions. For Vehicle 455, Random Forest with the LECF configuration recorded an RMSE of 0.26294, while for Vehicle 10, the RMSE reached 0.37340, indicating a slight decrease in performance at this interval compared to XGBoost. Dynamic Regression models exhibited moderate accuracy at this interval. For Vehicle 455, DR under the LECF configuration recorded an RMSE of 0.34969, while for Vehicle 10, it achieved 0.35169, demonstrating a stable but less competitive performance compared to XGBoost. ARIMA struggled significantly at the 10-minute interval. Its errors for Vehicle 10, for example, escalated to an RMSE of 0.62677, reflecting its difficulty in adapting to longer intervals with aggregated data. Even for Vehicle 455, where ARIMA typically performed better, its RMSE reached 0.57490, substantially higher than XGBoost.

Across all intervals, XGBoost consistently outperformed other models, making it the most reliable choice for energy consumption predictions. For shorter intervals, particularly the 1-minute interval, XGBoost in the LECF configuration demonstrated remarkable accuracy, leveraging both feature and energy consumption lags. For longer intervals, the LF configuration of XGBoost provided a good balance of simplicity and performance. Random Forest proved to be a dependable alternative, offering robust predictions but consistently trailing XGBoost. Its performance was particularly competitive at the 5-minute interval but weaker at the 10-minute interval. Dynamic Regression (DR) models offered strong competition, especially at shorter intervals, but lacked the consistency of XGBoost across different vehicles and intervals. ARIMA, while effective in specific cases, exhibited significant variability and struggled with aggregated data at longer intervals. Its performance was often surpassed by both XGBoost and Random Forest. These results highlight the robustness and adaptability of XGBoost, making it the most suitable model for energy consumption prediction across varying time intervals and vehicle data.

6. Conclusions

This research contributes to progress toward SDGs, particularly in sustainable transportation, by offering a robust and adaptive service for optimizing energy consumption in electric vehicles, thereby supporting decarbonization goals and the broader adoption of eco-friendly mobility solutions.

This research study proposed a novel methodology-framework for predicting energy consumption in electric vehicles, based on an advanced combination of machine learning models and state-of-the-art statistical data analysis techniques. The presented approach enabled the identification of temporal dependencies and facilitated more robust predictions by structuring the eVED dataset into multiresolution time intervals and applying lagged features.

Experimental results demonstrated that XGBoost, Random Forest, and regression-based models, with different configurations in lag structure, achieved high prediction accuracy. Additionally, the 1-minute intervals provided the most detailed insights, while 5-minute intervals offered a practical balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The findings indicate that integrating time-interval-based energy consumption modeling with machine learning enhances prediction accuracy across various driving scenarios and vehicle characteristics. This improvement supports better energy management strategies, contributing to eco-driving, refueling optimization, and range estimation.

Future work will integrate real-time data streams to enhance the applicability of the proposed methodology in dynamic environments. In particular, ML operations will be incorporated into the best-performing model, XGBoost, which utilizes both historical energy consumption and external features transforminf the methodology into a service. This service will be deployed in a real-life environment within the context of the SINNOGENES project.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe project SINNOGENES (Storage innovations for green energy systems), under Grant Agreement No. 101096992.

References

- Jose, P. S., A. Natarajan, S. Karthikeyan, and T. Bogaraj. Environmental and social impact of electric vehicles. In Advanced Technologies in Electric Vehicles. Elsevier, 2024, pp. 107–125.

- Sanguesa, J. A., V. Torres-Sanz, P. Garrido, F. J. Martinez, and J. M. Marquez-Barja. A review on electric vehicles: Technologies and challenges. Smart Cities, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2021, pp. 372–404. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., B. Zhang, H. Pourbabak, A. Kavousi-Fard, and W. Su. Optimal routing and charging of an electric vehicle fleet for high-efficiency dynamic transit systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2016, pp. 3563–3572. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F. Electric vehicles: benefits, challenges, and potential solutions for widespread adaptation. Applied Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 10, 2023, p. 6016. [CrossRef]

- Akshay, K., G. H. Grace, K. Gunasekaran, and R. Samikannu. Power consumption prediction for electric vehicle charging stations and forecasting income. Scientific Reports, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2024, p. 6497. [CrossRef]

- Longo, M., D. Zaninelli, F. Viola, P. Romano, and R. Miceli. How is the spread of the Electric Vehicles? In 2015 IEEE 1st International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Leveraging a better tomorrow (RTSI). IEEE, 2015, pp. 439–445.

- Klyuev, R. V., I. D. Morgoev, A. D. Morgoeva, O. A. Gavrina, N. V. Martyushev, E. A. Efremenkov, and Q. Mengxu. Methods of forecasting electric energy consumption: A literature review. Energies, Vol. 15, No. 23, 2022, p. 8919. [CrossRef]

- Chudy-Laskowska, K. and T. Pisula. An Analysis of the Use of Energy from Conventional Fossil Fuels and Green Renewable Energy in the Context of the European Union’s Planned Energy Transformation. Energies, Vol. 15, No. 19, 2022, p. 7369. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., B. Li, Y. Wang, Z. Zhang, and H. He. Analysis of factors influencing energy consumption of electric vehicles: Statistical, predictive, and causal perspectives. Applied Energy, Vol. 375, 2024, p. 124110. [CrossRef]

- Petkevicius, L., S. Saltenis, A. Civilis, and K. Torp. Probabilistic deep learning for electric-vehicle energy-use prediction. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Spatial and Temporal Databases. 2021, pp. 85–95.

- Hua, Y., M. Sevegnani, D. Yi, A. Birnie, and S. McAslan. Fine-grained RNN with transfer learning for energy consumption estimation on EVs. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, Vol. 18, No. 11, 2022, pp. 8182–8190. [CrossRef]

- Athanasakis, E., G. Spanos, A. Papadopoulos, A. Lalas, K. Votis, and D. Tzovaras. a Comprehensive Leakage-Free Forecasting Pipeline for Segmented Time Series: Application to Cross-Trip State-of-Charge Prediction in Automated Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Z. Lei, and S. V. Ukkusuri. Prediction of road-level energy consumption of battery electric vehicles. In 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 2550–2555.

- Tang, X., T. Jia, X. Hu, Y. Huang, Z. Deng, and H. Pu. Naturalistic data-driven predictive energy management for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2020, pp. 497–508. [CrossRef]

- Polymeni, S., V. Pitsiavas, G. Spanos, Q. Matthewson, A. Lalas, K. Votis, and D. Tzovaras. Toward sustainable mobility: AI-enabled automated refueling for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles. Energies, Vol. 17, No. 17, 2024, p. 4324. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, A., J. Gonder, L. Wang, E. Wood, S. Lopp, and L. Ramroth. FASTSim: A model to estimate vehicle efficiency, cost and performance. Tech. rep., SAE technical paper, 2015.

- Zhang, S., D. Fatih, F. Abdulqadir, T. Schwarz, and X. Ma. Extended vehicle energy dataset (eVED): an enhanced large-scale dataset for deep learning on vehicle trip energy consumption. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.08630.

[CrossRef]

- Oh, G., D. J. Leblanc, and H. Peng. Vehicle energy dataset (VED), a large-scale dataset for vehicle energy consumption research. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2020, pp. 3302–3312. [CrossRef]

- Mediouni, H., A. Ezzouhri, Z. Charouh, K. El Harouri, S. El Hani, and M. Ghogho. Energy consumption prediction and analysis for electric vehicles: A hybrid approach. energies, Vol. 15, No. 17, 2022, p. 6490. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., C. Zhuge, C. Shao, Y. Huang, J. H. C. G. Tang, M. Sun, P. Wang, and S. Wang. Characterizing mobility patterns of private electric vehicle users with trajectory data. Applied Energy, Vol. 321, 2022, p. 119417. [CrossRef]

- Spanos, G., K. M. Giannoutakis, K. Votis, and D. Tzovaras. Combining statistical and machine learning techniques in IoT anomaly detection for smart homes. In 2019 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Spanos, G., K. M. Giannoutakis, K. Votis, B. Viaño, J. Augusto-Gonzalez, G. Aivatoglou, and D. Tzovaras. A lightweight cyber-security defense framework for smart homes. In 2020 International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications (INISTA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Meire, M., M. Ballings, and D. Van den Poel. The added value of auxiliary data in sentiment analysis of Facebook posts. Decision Support Systems, Vol. 89, 2016, pp. 98–112. [CrossRef]

- Aivatoglou, G., M. Anastasiadis, G. Spanos, A. Voulgaridis, K. Votis, and D. Tzovaras. A tree-based machine learning methodology to automatically classify software vulnerabilities. In 2021 ieee international conference on cyber security and resilience (csr). IEEE, 2021, pp. 312–317.

- Aivatoglou, G., M. Anastasiadis, G. Spanos, A. Voulgaridis, K. Votis, D. Tzovaras, and L. Angelis. A RAkEL-based methodology to estimate software vulnerability characteristics & score-an application to EU project ECHO. Multimedia Tools and Applications, Vol. 81, No. 7, 2022, pp. 9459–9479. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, H., H. K. Meena, and P. Jain. Prediction of ev energy consumption using random forest and xgboost. In 2023 International Conference on Power Electronics and Energy (ICPEE). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning, Vol. 45, 2001, pp. 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. and C. Guestrin. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 2016, pp. 785–794.

- Pankratz, A. Forecasting with dynamic regression models. John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Wang, Z., Y. Wang, R. Zeng, R. S. Srinivasan, and S. Ahrentzen. Random Forest based hourly building energy prediction. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 171, 2018, pp. 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., H. Chang, Z. Sun, F. Liu, W. Li, D. Zhao, and C. Chen. Very short-term renewable energy power prediction using XGBoost optimized by TPE algorithm. In 2020 4th International Conference on HVDC (HVDC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1236–1241.

- Watanabe, S. Tree-structured parzen estimator: Understanding its algorithm components and their roles for better empirical performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11127.

- Moslemi, Z., L. Clark, S. Kernal, S. Rehome, S. Sprengel, A. Tamizifar, S. Tuli, V. Chokshi, M. Nomeli, E. Liang, et al. Comprehensive Forecasting of California’s Energy Consumption: A Multi-Source and Sectoral Analysis Using ARIMA and ARIMAX Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04432.

- Sun, Q., J. Liu, X. Rong, M. Zhang, X. Song, Z. Bie, and Z. Ni. Charging load forecasting of electric vehicle charging station based on support vector regression. In 2016 IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1777–1781.

- Saly, G., F. Szauter, and S. Kocsis Szürke. Comprehensive Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Energy Efficiency of Electric Vehicles and Methods to Reduce Consumption: A Review. Engineering Proceedings, Vol. 79, No. 1, 2024, p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S., Y. Shao, Y. Li, H. Yin, Y. Shen, and B. Cui. LECF: recommendation via learnable edge collaborative filtering. Science China Information Sciences, Vol. 65, No. 1, 2022, p. 112101. [CrossRef]

- Liashchynskyi, P. and P. Liashchynskyi. Grid search, random search, genetic algorithm: a big comparison for NAS. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.06059.

- Hyndman, R. J. and A. B. Koehler. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. International journal of forecasting, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2006, pp. 679–688. [CrossRef]

- Polymeni, S., G. Spanos, D. Tsiktsiris, E. Athanasakis, K. Votis, D. Tzovaras, and G. Kormentzas. everWeather: A Low-Cost and Self-Powered AIoT Weather Forecasting Station for Remote Areas. In Environmental Informatics. Springer, 2023, pp. 141–158.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).