Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contributions

- We present an innovative system layout, where EVs, owned by distinctive individuals, compete with one another to buy energy from different CSs that are deployed by different stakeholders.

- We summarize the data that are employed in an energy trading market. It is important to identify the sources of spatial and time data that are processed in the BI model.

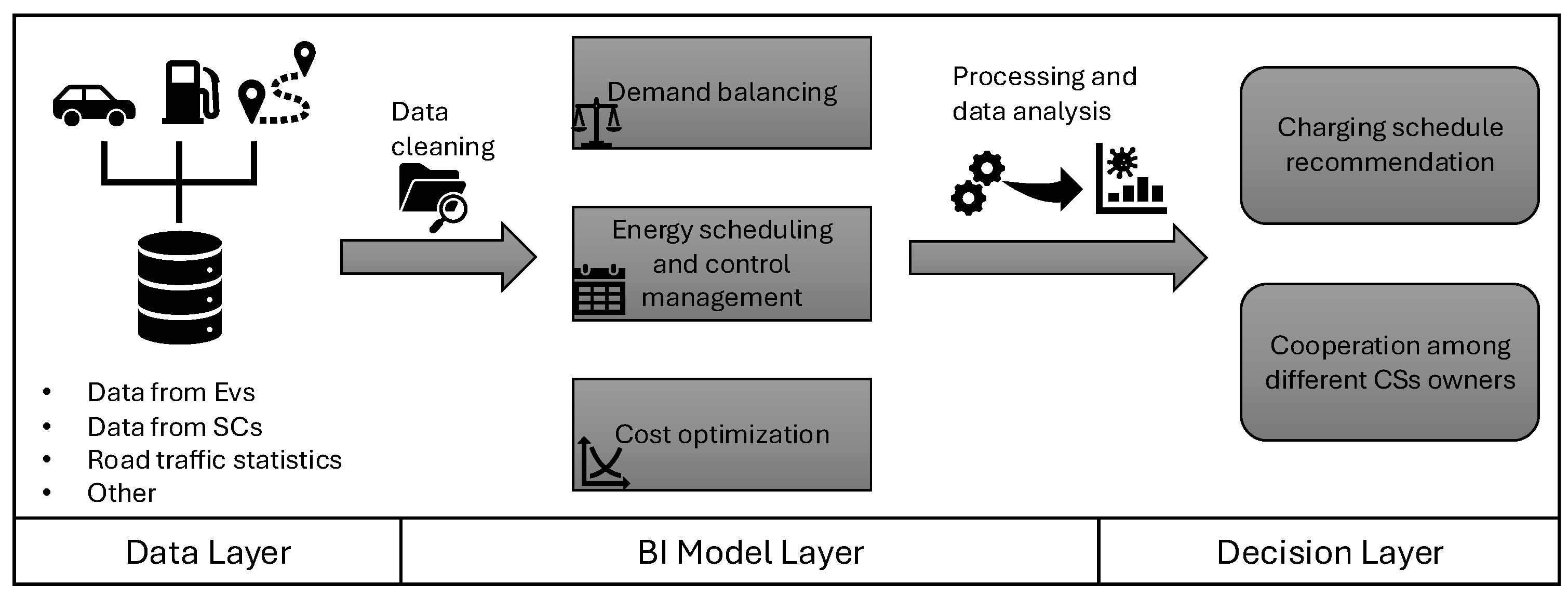

- We propose a business intelligence model. More specifically, we analyze the different layers that the BI is composed of, including the data layer, the BI layer and the decision layer.

- We present optimal solutions for addressing a number of energy charging problems, including the charging schedule recommendation, the cooperation among different CSs stakeholders and optimal infrastructure planning. Various strategies are investigated, including double auction strategies and iterative approaches.

2. Related Work

3. System Model

3.1. System Model and Operation

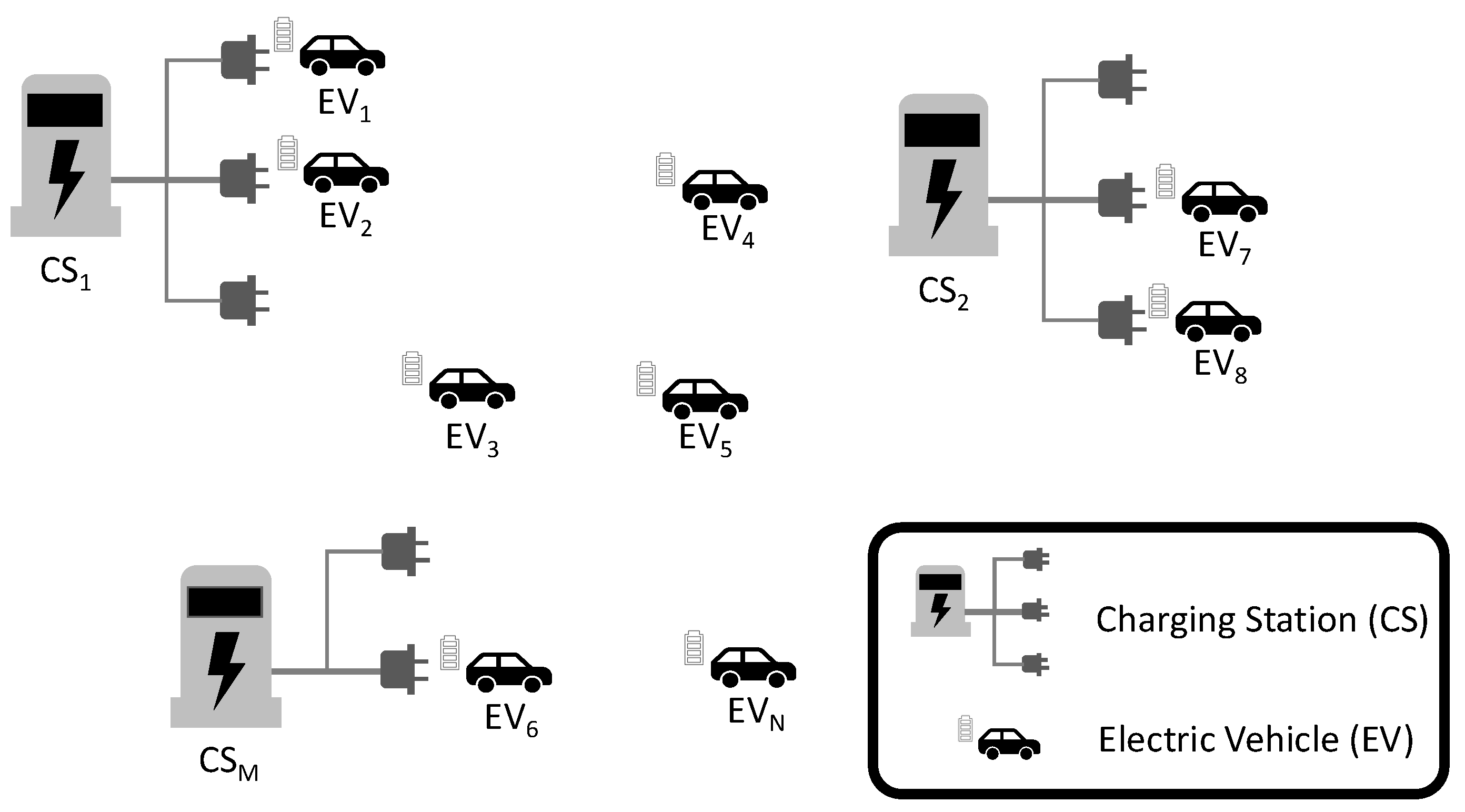

- EVs: We assume that there are N vehicles in the geographical area, denoted by , where . The EVs move around the area and are in search of CSs in order to charge their batteries. The vehicles are equipped with telematic systems and sensors to make their locations visible and provide useful data in the system.

- CSs: We assume that there is a set of M CSs, denoted by , where . Each CS acts as an aggregator in order to provide the ability to the EVs’ owners to communicate with the power grid. Additionally, fundamental data are provided to the system through the CSs, including locations, energy levels and availability in order to be exploited in the BI model.

3.2. Spatial Data

3.2.1. Location Data of Electric Vehicles

3.2.2. Selection of Charging Station Location

3.2.3. Charging Stations Density

3.3. Time Data

4. Business Intelligence Model

4.1. System Overview

4.2. Data Layer

- Data from EVs: The electric vehicles are often equipped with multiple sensors. The data that are gathered include the type of vehicle, the location of the EVs, the direction of the route, the levels of the battery health, the energy consumption, the urgency or not of the energy charging and the vehicle and the driver performance. Additionally, historical data are gathered, e.g., typical charging times, preferred charging locations, preferred routes or planned trips. As technology advances and AI is used, information about predicted routes based on the EVs behavior can be provided to help the BI model. The raw data need to be filtered, categorized in order to be easily accessed and employed.

- Data from CSs: Data are available from the CSs, as well. Important information include the type of CSs, the location of the CSs, the parking locations, their availability for charging, the real-time waiting queues, the potential use of renewable energy sources, the charging speed and the cost of the energy charging (e.g., flat rates, dynamic pricing). Information about the ownership can also be used since the management of CSs through third parties affects both pricing and accessibility. These data are crucial for the decision about charging schedule and infrastructure planning, if they are classified and integrated correctly.

- Data from Geographic Information Systems (GISs) and other applications: The GISs are hardware and software systems that collect, manage, analyze and visualize the geographical data. Both spatial and temporal data are available. The amount and the variety of data from GISs are enormous, nonetheless, we are interested in data that concern location of roads and railroads, traffic zones, buildings locations and even temperature. The analysis of the data provides valuable information about the mobility patterns of the EVs and infrastructure planning of the CSs.

- Other data: Other sources of data include surveys and questionnaires that are addressed to EVs’ owners and CSs’ stakeholders. Additionally, the use of applications by the involved users and parties could provide real-time information and statistics. Other information are gathered concerning the weather conditions, since they affect the energy demand, the traffic peak and off peak conditions and the renewable energy generation. Regulation and law constraints are also important. Based on the data, we are able to understand the the performance of our system and adjust its operation to the needs and demands of the EVs’ users and the CSs’ owners.

4.3. BI Model Layer

- Demand balancing: One crucial challenge in electric vehicles charging is the problem of balancing the charging load across the multiple charging stations that are scattered across the geographical area. Charging load balancing is connected to the peak demand management with upper goal to minimize the congestion to certain CSs and to divert charging demand away from peak hour of the day. Another objective is to exploit renewable energy resources. The most common approaches in the literature used to route the EVs individually in order to balance the demand. However, these solutions are not mature and the demand balancing has limited prospects. Another set of state-of-the-art works explore the load balancing demand from the perspective of EVs routing and choosing the most suitable parking lot for charging the vehicle [31]–[34]. Other works focus on the prediction of the EVs demand patterns and the analysis of energy demand fluctuations [35]–[38]. The proposition of a BI system enables the exploitation of the wide range of information that are available and from different resources in order to provide improved solutions. To begin with, BI employs the techniques of data analysis and mining in order to organize raw data, classifies them and finds the useful information. Using this data, charging patterns are identified and peak time demands and spacial congestion points are recognized. The time and spatial behavior of the EVs is then evaluated and effectively analyzed. The main objective of demand prediction is to be able to identify the high-demand time windows and anticipate the CSs use in order to avoid overcrowding. Moreover, understand charging preferences and habits motivates the recommendation of charging schedules based on the EVs behavior. The BI model are able to predict the charging demand in a specific urban region based on EV density and nearby charging stations. ARIMA and Long Short-Term Memory can be used for energy charging forecasting.

- Energy scheduling and control management: It is common that the owners of the electric vehicles choose the time that they charge their vehicles based on their work and duties schedule or based on the battery levels of their car. Therefore, there is no coordination between the EVs’ owners and the CSs to manage convenient charging. However, the uncoordinated charging has negative impact on the energy grid that feeds the CSs infrastructure (e.g., energy deficiencies and fluctuations) and on the satisfaction of the vehicles’ owners (e.g., long waiting times). A number of works in the literature deal with the charging scheduling problem. In the majority of the works, the problem is considered as an optimization problem, where a central controller manages the system and decides the optimal schedule for the CSs’ stakeholder [39]–[47]. Fewer works investigate the problem as a decentralized technique [48]–[52]. Concerning the objective goals, the time and load fluctuations are considered. Additionally, there in the need of balancing the energy charging so as to eliminate the peaks. Finally, the benefits of the CSs stakeholder are on focus. More specifically, the maximization of the utilization of CSs, the reduction of the queuing times and the distribution of the EVs efficiently are the main objectives of the CSs owners. From our point of view, there is a great need to take into account the demands and needs of all the involved parties (e.g., CSs owners, EVs owners, energy providers). Additionally, the demand patterns and the mobility of the vehicles could be exploited. Thus, a BI model considers the offered data at their best. Next, a holistic technique identifies the objectives that may be contradictive and tries to reach the optimal solution for everyone involved. Clustering models, linear regression and optimization tools can be used.

- Cost optimization: Following the aforementioned challenge, it is important to investigate the charging cost for both the EVs and CSs owners. Several works have addressed the specific challenge and proposed solutions whose focus was the charging cost [53]–[58]. It is important to use the BI tools to proposed strategies for dynamic pricing that will motivate the owners of the electric vehicles to cooperate and charge their vehicles at specific time periods so as not to create congestion and delays. Additionally, the research of optimal solutions is enabled through the use of a business intelligence model. Machine learning and data mining can be explored.

4.4. Decision Layer

-

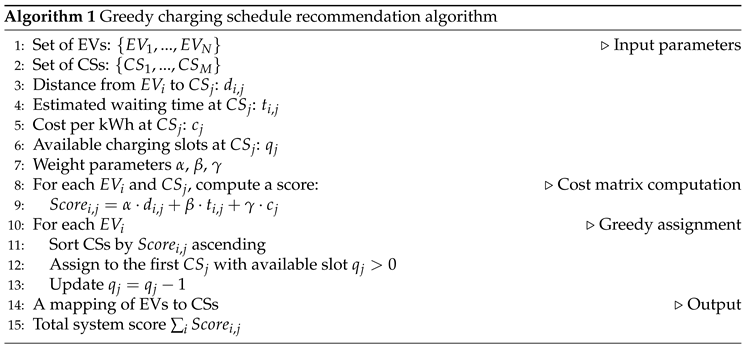

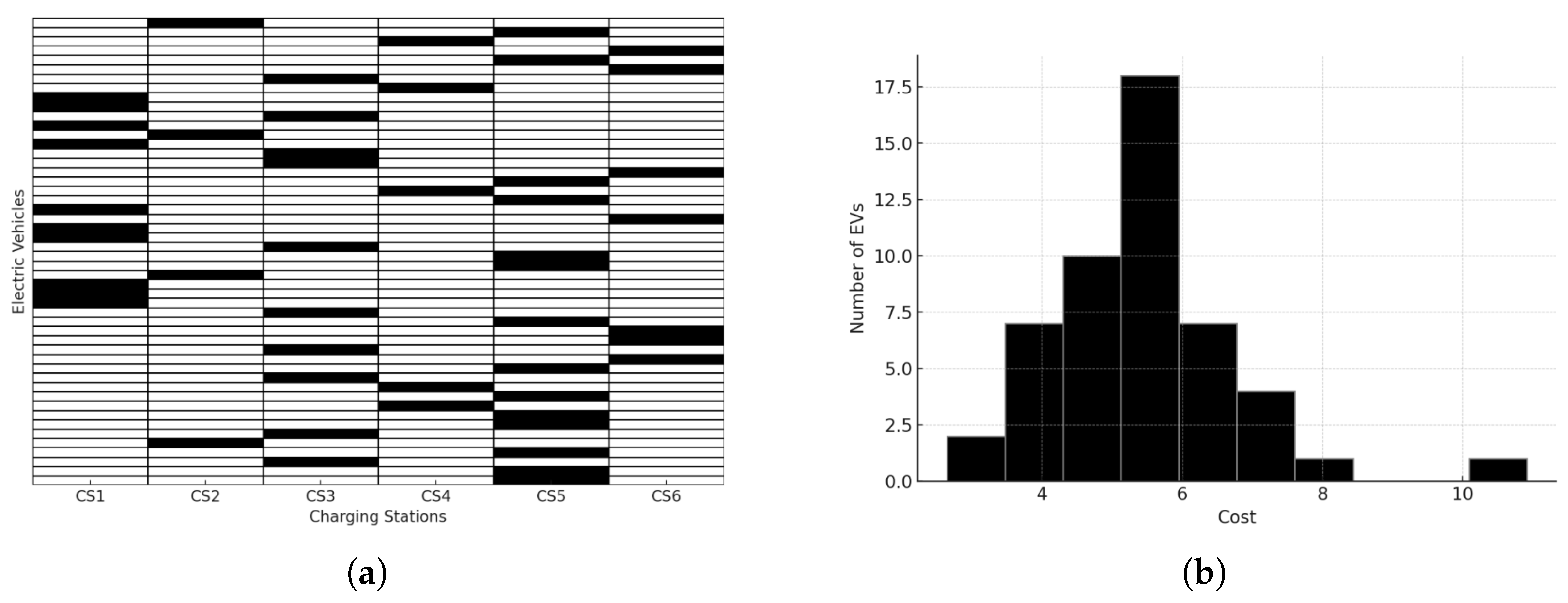

Charging schedule recommendation: Deciding the charging schedule is very important for the improvement of our system performance. More specifically, it is important for the EVs to decide dynamically when and where to charge and not deciding randomly simply based on their proximity to a CS and the battery level. Additionally, CSs can play a crucial role when they cooperate with each other and with the EVs. This is where a BI model is employed. A dynamic schedule using optimization tools can minimize the cost and waiting times of the involved counterparts while at the same time load balance is achieved across the CS by taking into account the proximity of the EVs and CS, the charging speed and the energy cost. An application can notify EVs’ owners for the optimal time and location of charging. The objectives of the optimization problem are among others: (a) the minimization of waiting time and the travel distance of the EVs, (b) the maximization of the CSs utilization and (c) the minimization of overloading the energy grid during peak hours. Linear programming, multi-agent simulations, game theory are employed. In our previous work, we proposed an innovative market formulation in which autonomous EVs and CSs are motivated to cooperate dynamically with changing roles. We adopted a multi-objective strategy that is repeated in steps [66]. Another formulation of the optimization problem considers the minimization of the cost of both EVs and CSs, as follows:where is the distance between and , is the estimated waiting time of at , and is the charging cost per energy unit at . The binary variable indicates the assignment of the at (the value 1 indicates the assignment, 0 is when is not assigned). The coefficients , and are weight parameters for distance, waiting time, and cost, respectively. The optimization problem is minimized under some constraints as follows:Each EV should be assigned to one CS,Each CS has a limited number of available charging slots, , for the EVs to charge,The total energy charged to the EVs at the CSs ( is the charged energy for at ) should not exceed the maximum grid energy level (namely P),The optimization problem mentioned above is a mixed integer linear programming approach and can be easily solved for medium-sized instances like 100 of EVs and CSs. However, solving the charging schedule recommendation problem becomes computationally difficult in large-scale and real-time scenarios. Thus, we adopt an efficient greedy weighted matching approach that approximates the optimal assignment with significantly lower computational complexity. The greedy approach, described in 1, we compute the cost for each EV-CS pair, based in the weighted sum of travel distance, expected waiting time and energy cost. Next, each EV is assigned to the a CS (the one with the lowest score), among those with available capacity. The algorithm is iterative for all EVs. The complexity of the algorithm is , making it suitable for real-time applications.

-

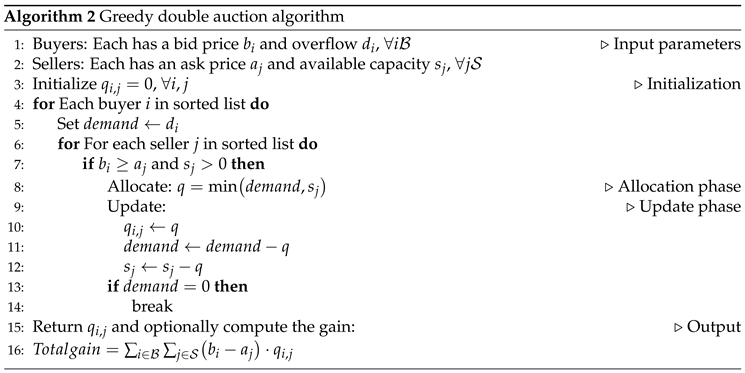

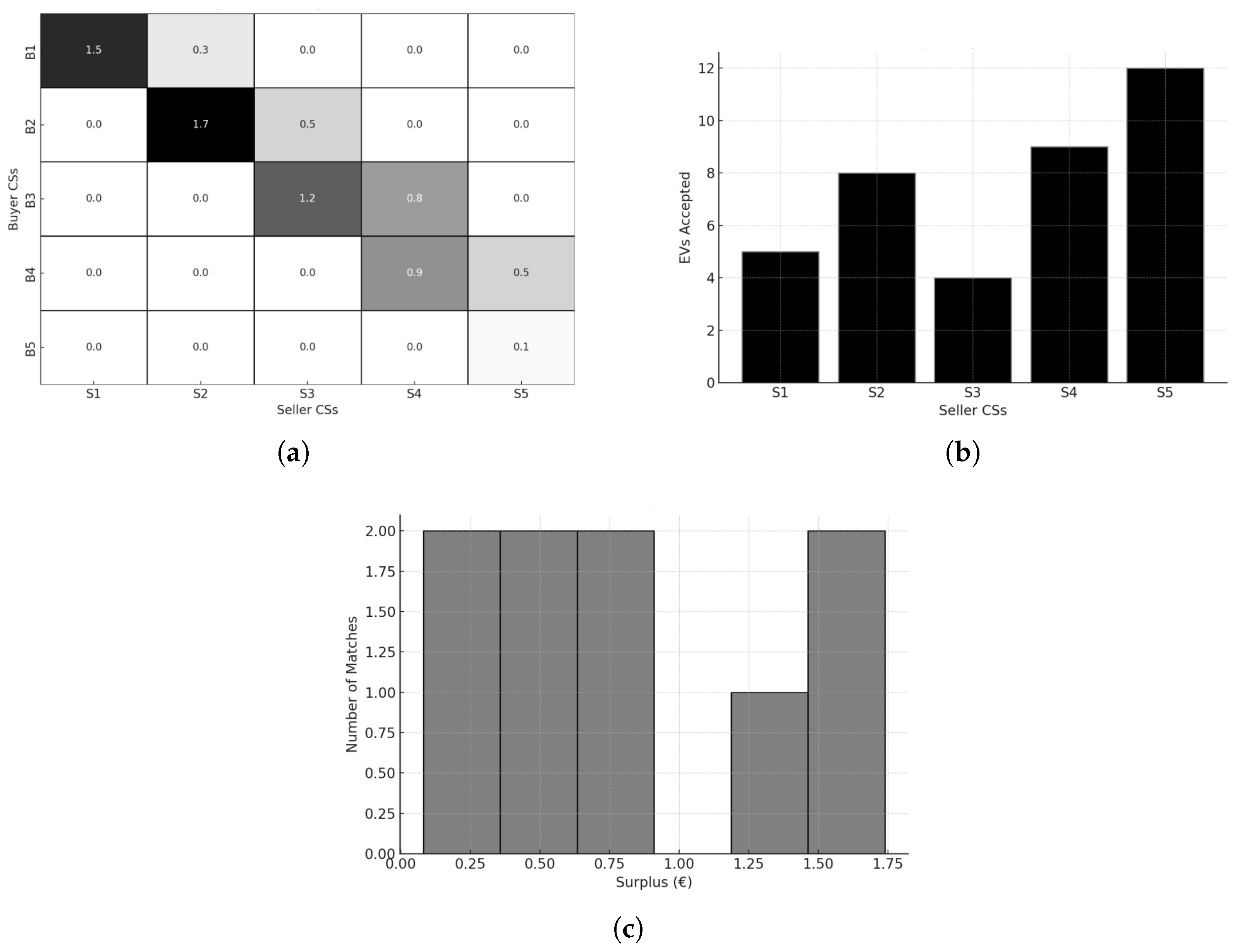

Cooperation among different CSs owners: The second direction of the BI model concerns the motivation for the cooperation of the CS owners in order to optimally utilize the resources and increase the satisfaction of the electric vehicles’ owners. It is evident that the stakeholders that are in charge of deploying the CSs have contraindicative interests. However, a cooperative scheme ensures a fair profit distribution among all the participants of the charging market. After collecting the required data from the EVs (e.g., battery level, charging needs, location, direction of traveling), the CSs (e.g., location, availability, pricing, energy source), the traffic patterns (e.g., peak hours, travel paths) and other sources (e.g., surveys, applications), the data are compiled and processed in order to provide centralized and decentralized solutions, dynamic pricing approaches, load balancing models and profit sharing mechanisms. More specifically, all the CSs’ owners, or at least their majority, are motivated to share some of their data in a common platform or application. Through data processing and the use of AI algorithms, dynamic charging schedules are recommended. These schedules prevent overloading or under-utilization. By using machine learning strategies, we predict peak charging times, and we adjust pricing and availability accordingly by taking into account waiting times, costs, and locations. The BI model decides the charging schedule and then divides the profits fairly among the CSs’ owners based on metrics and key indicators such as utilization and energy contribution. This scheme incentivizes the owners of the charging infrastructure to collaborate without losing their competitiveness. In a previous work, we proposed a double auction mechanism for a wireless network where network operators cooperate to share their traffic [67]. Similar solutions could be employed for the charging market.To facilitate the cooperation among independent CSs, we propose a BI-driven double auction mechanism that enables real-time, market-based coordination of charging demand. In this framework, CSs experiencing excess demand (i.e., overloaded stations) act as buyers (denoted by ), submitting bids, , to offload a portion of their incoming EV traffic. Let be the demand of buyer i, representing the number of EVs they wish to offload. Simultaneously, underutilized CSs act as sellers (denoted by ), offering to accept redirected EVs in exchange for compensation, defined by their ask prices, . We assume is the available capacity of seller j, which is the number of EVs they can accept. The BI system functions as a central auctioneer, matching bids and asks based on pricing compatibility and capacity availability. When a match is found, the participating CSs agree on a clearing price, typically the midpoint between the bid and ask, which ensures mutual benefit. This approach encourages load balancing, enhances overall infrastructure utilization, and creates economic incentives for collaboration, even in competitive environments. The model is scalable, incentive-compatible, and adaptable to both energy and service-based cooperation scenarios. The allocation problem is to determine the optimal solution that maximizes the distinctive objectives of the involved parties in the auction, subject to constraints. The decision variable decides whether a buyer i is matched with a seller j () or not (). We assume the number of EVs transferred from buyer i to seller j. The maximization problem, reflecting the gain from each matched trade, where is the net benefit and is the trade volume, is formulated as follows:s.t.Constraint 6a ensures that each buyer CS i (who wants to offload EVs) cannot offload more EVs than it has in overflow, meaning that the total number of EVs redirected to all sellers from CS i must not exceed demand . Constraint 6b ensures that each seller CS j (who is willing to accept redirected EVs) does not accept more than its remaining charging capacity. The total number of EVs received from all buyers must be less than or equal to the station’s available slots . With constraint 6c, a trade is disallowed between buyer i and seller j if the buyer’s bid is less than the seller’s ask. The constraint 6d links the binary match variable with the number of EVs transferred . If (no trade between i and j), then . If , then can be any value up to a large constant M. Constraint 6e is the binary decision variable and constraint 6f represents a non-negative integer representing the number of EVs traded. A greedy heuristic is a practical solution, which is at the same time fast, simple and effective, to solve the maximization problem in Eq. 5. The double auction approach is shown in Algorithm 2.

5. Case Studies Scenarios and Results

5.1. Charging Schedule Recommendation

5.2. Cooperation Among Different CSs Owners

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- Ehsani, M.; Singh, K. V.; Bansal, H. O.; Mehrjardi, R. T. State of the Art and Trends in Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicles. in Proceedings of the IEEE. 2021, 109, 6, 967–984. [CrossRef]

- Fesli, U.; Ozdemir, M. B.. Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Integration, Adoption, and Optimization IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 140908-140931. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Eichi, H.; Zeng, W.; Chow, M. Y. A Survey on the Electrification of Transportation in a Smart Grid Environment. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2012, 8, 1 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Strbac, G.; Kang, C. Decarbonising the GB Power System via Numerous Electric Vehicle Coordination. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 2024, 39, 4 5880–5894. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Starace, F.; Tricoire, J. P. Plectric Vehicles for Smarter Cities the Future of Energy and Mobility. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 2018.

- Ahmad, A.; Alam, M. S.; Chabaan, R. A Comprehensive Review of Wireless Charging Technologies for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification. 2018, 4, 1, 38–63. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, V.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Efficiency Enhancement of Wireless Charging System for the Electric Vehicles Applications. IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 46967–46994. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Wireless Charging Systems for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 43865–43881. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, Y.; et al. A Systematic Review of Dynamic Wireless Charging System for Electric Transportation. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 133617–133642. [CrossRef]

- Sagar, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of the Recent Development of Wireless Power Transfer Technologies for Electric Vehicle Charging Systems. IEEE Access. 2023, 11, 83703–83751. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S. A. Q.; Jung J. W. A Comprehensive State-of-the-Art Review of Wired/Wireless Charging Technologies for Battery Electric Vehicles: Classification/Common Topologies/Future Research Issues. IEEE Access. 2021, 9, 19572–19585. [CrossRef]

- Acharige, S. S. G.; Haque, M. E.; Arif, M. T.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Hasan, K. N.; Oo, A. M. T. Review of Electric Vehicle Charging Technologies, Standards, Architectures, and Converter Configurations. IEEE Access. 2023, 11, 41218–41255. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J. C.; Gupta, A. A Review of Charge Scheduling of Electric Vehicles in Smart Grid. IEEE Systems Journal. 2015, 9, 4 1541–1553. [CrossRef]

- Shuai, W.; Maillé, P.; Pelov, A. Charging Electric Vehicles in the Smart City: A Survey of Economy-Driven Approaches. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2016, 17, 8 2089–2106. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Kong, F. Smart Charging for Electric Vehicles: A Survey From the Algorithmic Perspective. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 2016, 18, 2 1500–1517. [CrossRef]

- Al-Alwash, H. M.; Borcoci, E; Vochin, M. C.; Balapuwaduge, I. A. M.; Li, F. Y. Optimization Schedule Schemes for Charging Electric Vehicles: Overview, Challenges, and Solutions. IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 32801–32818. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Tang, J.; Ghosh, P. Optimizing electric vehicle charging with energy storage in the electricity market. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2013, 4, 1, 311–320. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kang, L.; Liu, Y. Optimal scheduling for electric bus fleets based on dynamic programming approach by considering battery capacity fade. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2020, 130. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y; Wu, X. The multiobjective based large-scale electric vehicle charging behaviours analysis. Complexity. 2018.

- Savari, G. F.; Krishnasamy, V.; Sugavanam, V.; Vakesan, K. Optimal charging scheduling of electric vehicles in micro grids using priority algorithms and particle swarm optimization. Mobile Networks and Applications. 2019, 24, 6, 1835–1847. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.; Amaris, H.; Germain, J.; Galan, J. Optimal charging scheduling of electric vehicles in smart grids by heuristic algorithms. Energies. 2014, 7, 4, 2449–2475. [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, T.; Devabalaji, K. R.; Kumar, J. A.; Thanikanti, S. B.; Nwulu, N. I. A Comprehensive Review and Analysis of the Allocation of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Distribution Networks. IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 5404–5461. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, T. D.; Franco, J. F.; Lezama, F.; Soares, J.; Vale, Z. Joint optimal allocation of electric vehicle charging stations and renewable energy sources including CO2 emissions. Energy Information. 2021, 4, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M. F.; Mohamed, S.; Ismail, M.; Qaraqe, K. A.; Serpedin, E. Joint planning of smart EV charging stations and DGs in eco-friendly remote hybrid microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2019, 10, 5, 5819–5830. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Shen, S.; Liao, Y.; Wang, C.; Shahabi, L. Shunt capacitor allocation by considering electric vehicle charging stations and distributed generators based on optimization algorithm. Energy. 2022, 239, 5819–5830. [CrossRef]

- Golla, N. K.; Sudabattula, S. K.; Suresh, V. Optimal placement of electric vehicle charging station in distribution system using meta-heuristic techniques. Mathematical Modelling and Engineering Problems. 2022, 9, 1, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Alsaidan, I.; Alaraj, M.; Almasoudi, F. M.; Rizwan, M. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of grid-connected electric vehicle charging station using AI-based algorithm. Mathematics 2022, 10, 6, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Ashraf, I.; Iqbal, A.; Marzband, M.; Khan, I. A novel AI approach for optimal deployment of EV fast charging station and reliability analysis with solar based DGs in distribution network. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 11646–11660. [CrossRef]

- Eldjalil, C.D.A.; Lyes, K. Optimal priority-queuing for EV charging-discharging service based on cloud computing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Paris, France, 21–25 May 2017; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Masoum, M.A.S. A coordinated dynamic pricing model for electric vehicle charging stations. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification. 2019, 5, 226–238. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, W. Charging scheduling with minimal waiting in a network of electric vehicles and charging stations. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM international workshop on Vehicular inter-networking (VANET ’11). Association for Computing Machinery. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Häusler, F.; Crisostomi, E.; Schlote, A.; Radusch, I.; Shorten, R. Stochastically Balanced Parking and Charging for Fully Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE). 2012. [CrossRef]

- Klappenecker, A.; Lee, H.; Welch, J. L. Finding available parking spaces made easy. Ad Hoc Networks. 2014. 12. [CrossRef]

- Häusler, F.; Crisostomi, E.; Schlote, A.; Radusch, I.; Shorten, R. Stochastic Park-and-Charge Balancing for Fully Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2014. 15, 2. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Cai, T.; Duan, S.; Zhao, F. Stochastic Modeling and Forecasting of Load Demand for Electric Bus Battery-Swap Station. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery. 2014. 29, 4, 1909–1917. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chung, C. Y.; Nie, Y.; Yu, R. Modeling and optimization of electric vehicle charging load in a parking lot. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC). 2013, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, T. Energy-storage configuration for EV fast charging stations considering characteristics of charging load and wind-power fluctuation. Global Energy Interconnection. 2021, 4, 1, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, M. A.; Almutairi, A.; Alyami, S.; Dahoud, R.; Mansour, A. M.; Aldaoudeyeh, A.-M.; Hrayshat, E. S. Effect of electric vehicles charging loads on realistic residential distribution system in aqabajordan. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2021, 12, 4, 218. [CrossRef]

- Sortomme, E.; El-Sharkawi, M. A. Optimal charging strategies for unidirectional vehicle-to-grid. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2011, 2, 1, 131–138. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Han, S.; Sezaki, K. Development of an Optimal Vehicle-to-Grid Aggregator for Frequency Regulation. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2010, 1, 1, 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Sortomme, E.; El-Sharkawi, M. A. Optimal Scheduling of Vehicle-to-Grid Energy and Ancillary Services. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 1, 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Koufakis, A. M.; Rigas, E. S.; Bassiliades, N.; Ramchurn, S. D. Offline and Online Electric Vehicle Charging Scheduling With V2V Energy Transfer. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2020, 21, 5, 2128–2138. [CrossRef]

- Khodayar, M. E.; Wu, L.; Shahidehpour, M. Hourly Coordination of Electric Vehicle Operation and Volatile Wind Power Generation in SCUC. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 3, 1271–1279. [CrossRef]

- Sortomme, E.; Hindi, M. M.; MacPherson, S. D. J.; Venkata, S. S. Coordinated Charging of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles to Minimize Distribution System Losses. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2011, 2, 1, 198–205. [CrossRef]

- Sortomme, E.; El-Sharkawi, M. A. Optimal Combined Bidding of Vehicle-to-Grid Ancillary Services. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 1, 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Deilami, S.; Masoum, A. S.; Moses, P. S.; Masoum, M. A. S. Real-Time Coordination of Plug-In Electric Vehicle Charging in Smart Grids to Minimize Power Losses and Improve Voltage Profile. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2011, 2, 3, 456–467. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, W.; Han, Z.; Cao, Z. Charging Scheduling of Electric Vehicles With Local Renewable Energy Under Uncertain Electric Vehicle Arrival and Grid Power Price. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. 2014, 63, 6, 2600–2612. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Venkatesh, B.; Guan, L. Optimal Scheduling for Charging and Discharging of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 3, 1095–1105. [CrossRef]

- Wen, C. K.; Chen, J. C.; Teng, J. H; Ting, P. Decentralized Plug-in Electric Vehicle Charging Selection Algorithm in Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 4, 1779–1789. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z. A Distributed Demand Response Algorithm and Its Application to PHEV Charging in Smart Grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 3, 1280–1290. [CrossRef]

- Ota, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Nakajima, T.; Liyanage, K. M.; Baba, J.; Yokoyama, A. A Autonomous Distributed V2G (Vehicle-to-Grid) Satisfying Scheduled Charging. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012, 3, 1, 559–564. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; Luh, P. B. Decentralised online charging scheduling for large populations of electric vehicles: A cyber-physical system approach. International Journal of Parallel Emergent and Distributed Systems. 2013, 28, 1, 29–45. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Sarma, N. J.; Hyland, M. F.; Jayakrishnan, R. Dynamic modeling and real-time management of a system of EV fast-charging stations. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Ren, Y.; Pan, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Fair and Efficient Electric Vehicle Charging Scheduling Optimization Considering the Maximum Individual Waiting Time and Operating Cost. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. 2023, 72, 8, 9808–9820. [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Ge, L. A Simultaneous Multi-Round Auction Design for Scheduling Multiple Charges of Battery Electric Vehicles on Highways. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2022, 23, 7, 8024–8036. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; An, D.; Li, D.; Wu, Z. Multistep Multiagent Reinforcement Learning for Optimal Energy Schedule Strategy of Charging Stations in Smart Grid. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics. 2023, 53, 7, 4292–4305. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ye, Z.; Gao, H. O.; Yu, N. Lyapunov Optimization in Online Battery Energy Storage System Control for Commercial Buildings. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2023, 14, 1, 328–340. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Phung, Q. V. Smart Charging Strategy for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification. 2018, 4, 1, 76–88. [CrossRef]

- Lam, A. Y. S.; Leung, Y. W.; Chu, X. Electric vehicle charging station placement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm. 2013, 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Gatica, G.; Ahumada, G.; Escobar, J. W.; Linfati, R. SEfficient heuristic algorithms for location of charging stations in electric vehicle routing problems. Studies in Informatics and Control. 2018, 17, 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Lam, A. Y. S.; Leung, Y. W.; Chu, X. Electric vehicle charging station placement: formulation, complexity, and solutions. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2014, 5, 6, 2846–2856, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Wu, B.; Chiang, Y. Y.; Zhang, X. Efficient Deployment of Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: Simultaneous Optimization of Charging Station Placement and Charging Pile Assignment. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2021, 22, 10, 6654–6659. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, Z. Y.; Luo, F.; Meng, K.; Zhang, Y. Stochastic Collaborative Planning of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Power Distribution System. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2018, 14, 1, 321–331. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Gan, J.; An, B.; Miao, C.; Bazzan, A. L. C. Optimal Electric Vehicle Fast Charging Station Placement Based on Game Theoretical Framework. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2018, 19, 8, 2493–2504. [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Derakhshandeh, S. Y.; Ghiasian, A.; Masoum, M. A. S. Optimal Siting and Sizing of Wireless EV Charging Infrastructures Considering Traffic Network and Power Distribution System. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 117105–117117. [CrossRef]

- Bousia, A.; Daskalopulu, A.; Papageorgiou, E.I. An Auction Pricing Model for Energy Trading in Electric Vehicle Networks. Electronics. 2023, 12, 3068. [CrossRef]

- Bousia, A.; Daskalopulu, A.; Papageorgiou, E.I. Double Auction Offloading for Energy and Cost Efficient Wireless Networks. Mathematics. 2022, 10, 4231. [CrossRef]

| CS | Capacity | Location coordinates | Wait time (min) | Cost (€/kWh ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 5 | |||

| 8 | 12 | |||

| 12 | 10 | |||

| 5 | 15 | |||

| 15 | 8 | |||

| 7 | 20 |

| CS | Assigned EVs | Capacity | Utilization (%) | Average cost (€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 | |||

| 4 | 8 | |||

| 10 | 12 | |||

| 5 | 5 | |||

| 14 | 15 | |||

| 7 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).