1. Introduction

Diagnostics of growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is one of the major challenges in pediatric endocrinology, and the diagnosis should take into account the clinical probability of the disease and the assessment of growth hormone (GH) secretion in stimulation tests (GHST) [

1,

2]. As in the classification of pediatric endocrine diagnoses [

3], GHD as a synonymous of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) deficiency, Wit et al. [

2] have proposed to measure IGF-1 concentrations as a part of screening procedure while diagnosing GHD in children with short stature, together with thorough clinical assessment of the patients.

The incidence of GHD in pediatric population is relatively rare, the recent review of population-based studies [

4] gives the frequencies ranging from about 1:30,000 in the oldest of cited papers [

5,

6,

7] by 1:3480 in US study from 1990 [

8] to about 1:1000 (exactly 127:100,000 in boys, 93:100,000 in girls) in a large study based on Finnish registries from 1998-2017 [

9]. Even higher rate of GHD, e.g. 13.4/10,000 (that corresponds to 1:746) has been reported in a more recent study of Italian pediatric population [

10]. The assumption that the incidence of GHD is 1:5000 lead to the consideration that only approximately 1% of children with height SDS below -2.0 should have established this diagnosis [

2]. There are also reports indicating a high rate of false positive GHST results [

11,

12,

13]. Diagnostic controversy and the risk of overdiagnosis GHD concerns mainly the patients with idiopathic, isolated GHD, as in ones with anatomic abnormalities in the pituitary region, genetic defects related to impaired GH secretion and/or multiple pituitary hormone deficiency, the diagnosis seems undoubtful [

1,

12]. The problems with proper interpretation of the results of GHST and current knowledge on factors influencing these results have been widely described in a quite recent paper of Kamoun et al. [

14].

There is also more and more data indicating that isolated, idiopathic GHD, diagnosed in childhood is a disease of a fundamentally transitional nature, as in the majority of patients after completion of growth promoting therapy, GH secretion in the repeated GHST appears to be normal, even with respect to “pediatric” criteria [

15]. Moreover, there is also increasing evidence that such normalization of GH secretion is observed already in in mid-puberty [

16,

17]. This phenomenon, described as “transient GHD”, may be explained either by real improvement of previously decreased GH secretion or by the obtaining false positive results of GHST in childhood. Interestingly, similar problems were highlighted in 1990s by Cacciari et al. [

18].

In the majority of studies on GHD in children, the auxological parameters (height, body mass, BMI, height velocity) and IGF-1 concentrations are expressed as SDS values for sex and age (sometimes for pubertal stage) to enable direct comparisons in the population of developmental age. Bone age (BA) is usually presented as its difference from or proportion to chronological age (CA). This is undoubtedly justified by the adopted statistical analysis methodologies. Nevertheless, this way the raw data are lost from the analysis, that makes impossible comparisons depending on the height (not only height SDS), body mass or BMI (not only BMI SDS) or BA (not only in relation to CA), or finally IGF-1 (not only IGF-1 SDS).

Taking into account the need for assessment of pre-GHST clinical probability of GHD, it seems possible to use advanced computational methods of machine learning (commonly referred to as artificial intelligence) to create models predicting GHD, based on patient’s history, basic auxological data followed by assessment of BA and IGF-1 concentrations.

The aim of present study was to identify prognostic factors for the diagnosis of GHD in children with short stature depending on selected clinical parameters and IGF-1 concentration, using the raw data obtained from the patients.

2. Materials and Methods

The retrospective, non-interventionary study included 1592 children (985 boys, 607 girls), aged 10.3±3.4 years (mean±SD), with short stature, diagnosed in a single reference center of pediatric endocrinology in years 2003-2020, in whom standard diagnostics was performed, including height and weight measurements, two pharmacological GHST (after clonidine and glucagon), determination IGF-1 concentration and BA assessment.

Short stature was defined as patient’s height below 3rd centile for age and sex, according to Polish reference charts [

19]. Based on patients’ history, all children with any congenital malformations, genetic defects, multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (MPHD) chronic diseases and/or therapies that might disturb growth, as well as ones with acquired GHD or MPHD were excluded from the study Thus, differential diagnosis included GHD and idiopathic short stature.

In all the patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria, body mass index (BMI) was calculated for all the patients, as well as hSDS, BMI SDS and IGF-1 SDS, with respect to appropriate reference data for patient’s age and sex.

Height SDS was calculated according to the reference data of Palczewska and Niedźwiecka [

19], BMI-SDS with respect to the reference data of Kułaga et al. [

20,

21]. Bone age was assessed using Greulich-Pyle standards [

22], based on X-ray images of hand and wrist, obtained within 6 months before or after performing GHST, however, in the majority of patients – during the same hospitalization as GHST. The assumed time range was dictated by the limitations resulting from radiological protection, as well as the time intervals between subsequent standards in the used atlas [

22].

The diagnosis of GHD was based on GH peak below 10.0 µg/l in two stimulation tests: with clonidine 0.15 mg/m2, orally (GH concentrations measured every 30 minutes from 0 to 120 minute of the test) and with glucagon 0.03 mg/kg (not exceeding 1.0 mg), intramuscularly (GH concentrations measured in 0, 90, 120, 150 and 180 minute of the test). The concentrations of GH were measured by the two-site chemiluminescent enzyme immunometric assay (hGH IMMULITE, DPC) for the quantitative measurement of human GH, calibrated to WHO IRP 80/505 standard or to 98/574 standards in different years. We cannot guarantee full equivalence of the different laboratory kits used over the 18 year period, nevertheless – according to current standards - the cut-off of GH peak in GHST diagnostic for GHD is the same for different combinations of two tests and independent from the used method of determining GH concentrations [

1,

23].

There was no requirement to confirm IGF-1 deficiency to establish a diagnosis of GHD, nevertheless all the patients had assessed IGF-1 secretion at timepoint 0 of the first GHST. In the years 2003-2016, the concentrations of IGF-1 were measured with solid-phase, enzyme-labelled chemiluminescent immunometric assays (IMMULITE, DPC), calibrated to WHO NIBSC 1st IRR 87/518, while since 2017 with new IGF-1 assays, standardized to WHO 1st International Standard 02/254, with appropriate conversion of the obtained results, according to the equation provided in Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Customer Bulletin for IMMULITE® 2000 Immunoassay System [

24]. All IGF-1 values were expressed as IGF-1 SDS for age and sex [

25], according to appropriate reference data and following the formula proposed by Blum and Schweitzer [

26].

Statistical analysis started from the assessment of distributions of particular variables with Shapiro-Wilk test. As for almost all variables (except for BMI SDS in boys and in girls with GHD but not in ones with ISS), the assumption of normal distribution was not met, descriptive statistics were presented as median and interquartile range (25 centile; 75 centile). Accordingly, appropriate non-parametric tests for independent variables were used – Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between two groups, while Kruskal-Wallis test with appropriate multiple post-hoc comparisons for more than two groups. Statistical analysis was performed with Statistica 13.3.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Based on GH peak in the two GHST below 10.0 µg/l, GHD was diagnosed 604 patients (37.9%), including 378 out of 985 boys (38.4%) and 226 out of 607 girls (37.2%); the remaining patients were diagnosed with ISS. Detailed characteristic of the whole study group and of boys and girls is presented in

Table 1, with respect to diagnosis – in

Table 2.

Significant differences were observed between boys and girls in almost all the analyzed variables (see

Table 2), except for BMI SDS and GH peak in two GHST, thus, further analyses were performed separately for boys and for girls.

3.2. Analysis of Raw Data

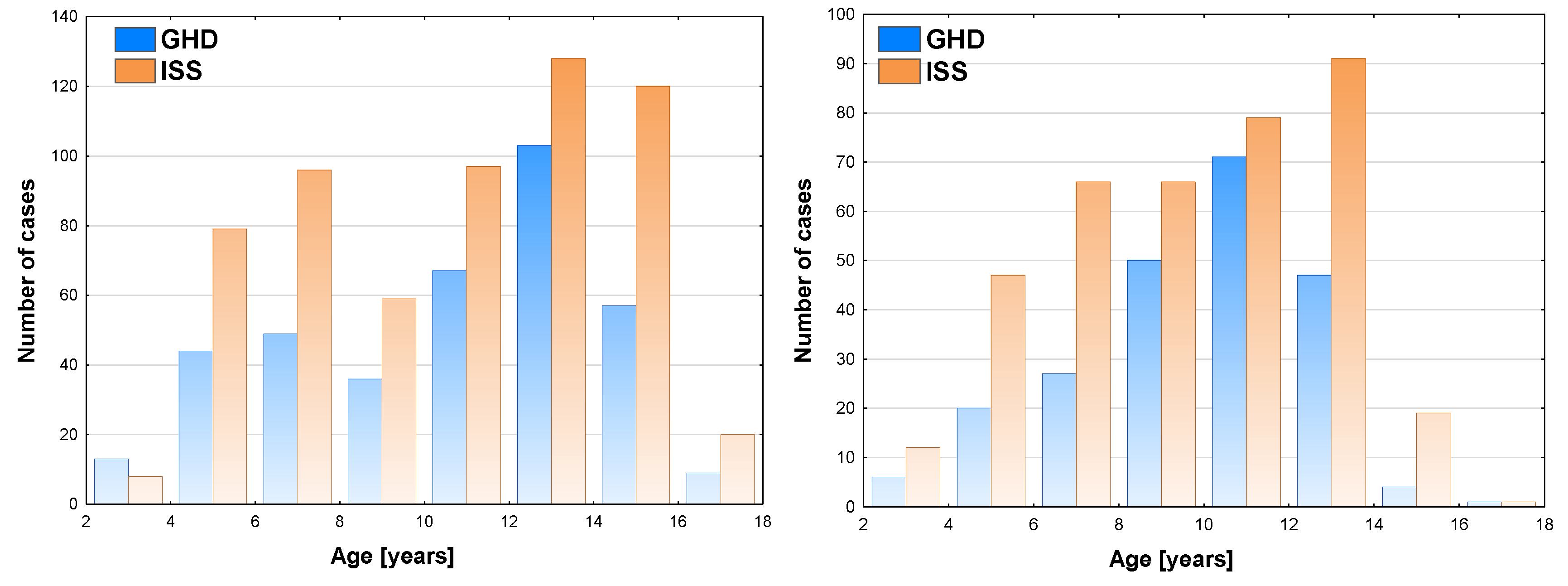

In the analysis of raw data of boys, the highest number of patients was diagnosed at the age of 12-14 years (103 cases), the incidence of GHD was the highest (44.6%) in the same age group (see

Figure 1a). In girls, the highest number of patients diagnosed with GHD was observed at the age of 10-12 years (71 cases), the incidence of GHD was the highest (47.3%) in the same age group (see

Figure 1b).

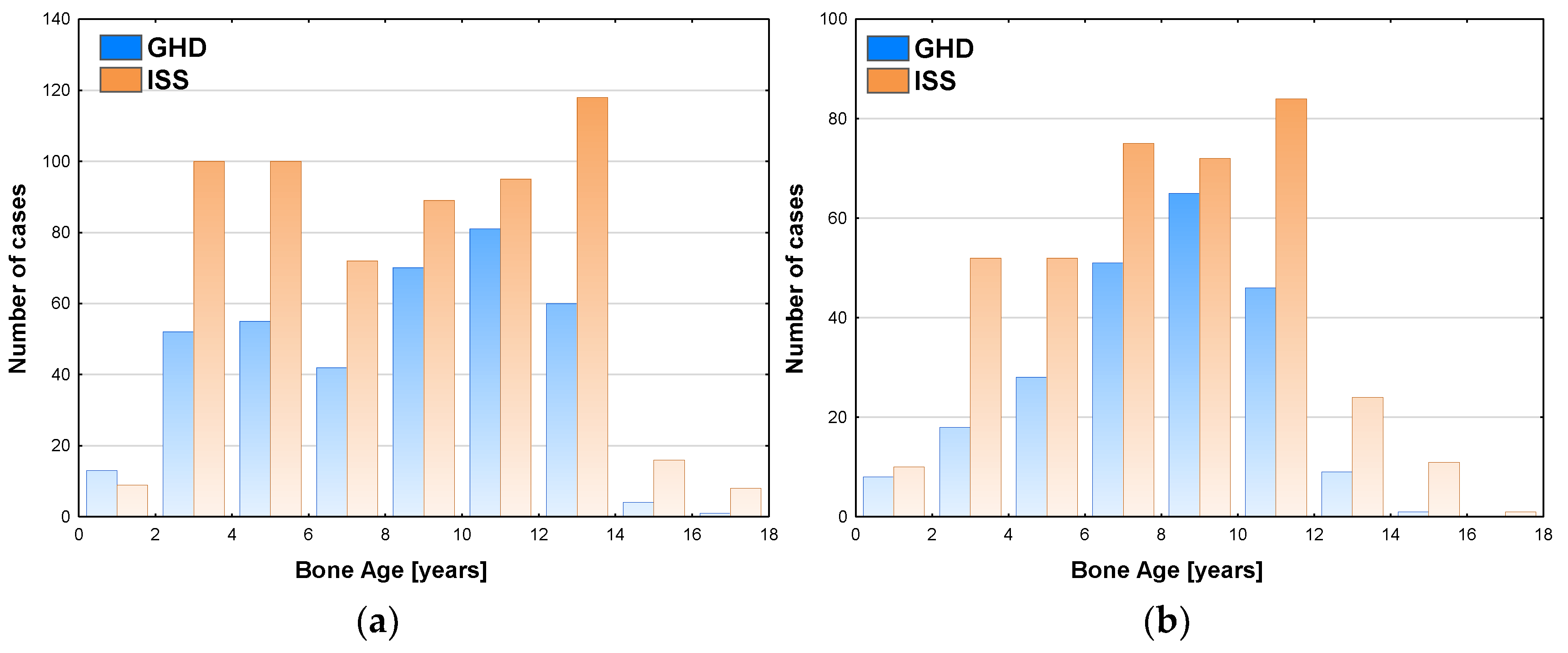

Similar analysis performed with respect to bone maturation (expressed as BA) and sex showed among boys the highest number of patients (81 cases) was diagnosed with GHD at BA 10-12 years, the highest incidence of GHD (46.0%) was observed in the same group and decreased in the groups with older BA; there should also be noted that a number of patients subjected to diagnostics with BA 12-14 years was higher than with BA 10-12 years (see

Figure 2a). Among girls, the highest number of patients (65 cases) was diagnosed with GHD at BA 8-10 years, the highest incidence of GHD (47.4%) was with observed in the same group and decreased in the groups with older BA; there should also be noted that a number of patients subjected to diagnostics with BA 10-12 years was higher than with BA 10-12 years (see

Figure 2b).

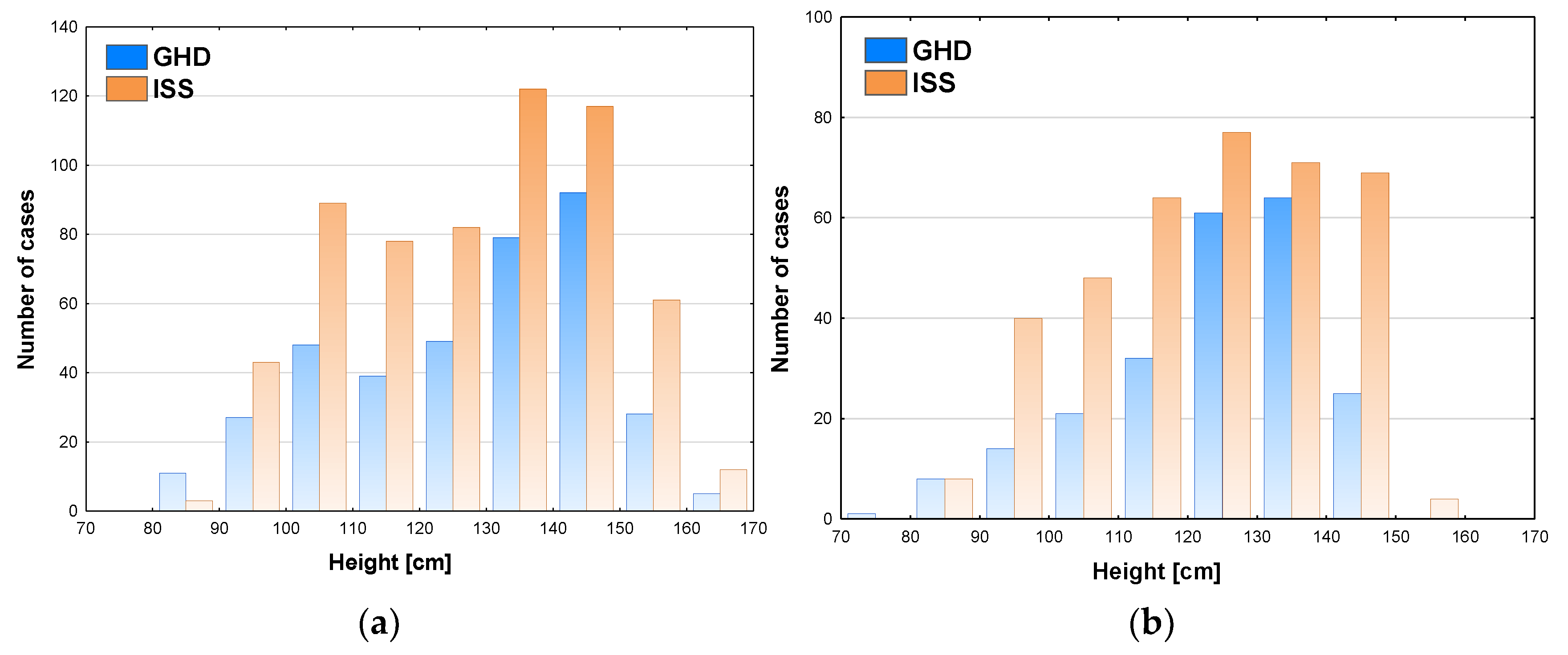

Some relationships were also observed between patients’ height and the incidence of GHD. In boys, the highest number of patients (92 cases) GHD was diagnosed at height 140-150 cm, in this group the incidence of GHD was also the highest (44.0%) and decreased rapidly (to 31.5%) at height 150-160 cm and over 160 cm (29.4%)the number of patients subjected to diagnostics was also lower in the latter groups (see

Figure 3a).In girls, the highest number of patients (64 cases) was diagnosed with GHD at height 130-140 cm and slightly less (61 cases) at height 120-130 cm, the incidence of GHD was the highest (47.4%) and height 130-140 cm and decreased rapidly (to 26.5%) at height 140-150 cm, despite similar number of girls subjected to diagnostics, while none of the girls was diagnosed with GHD at height over 150 cm (see

Figure 3b).

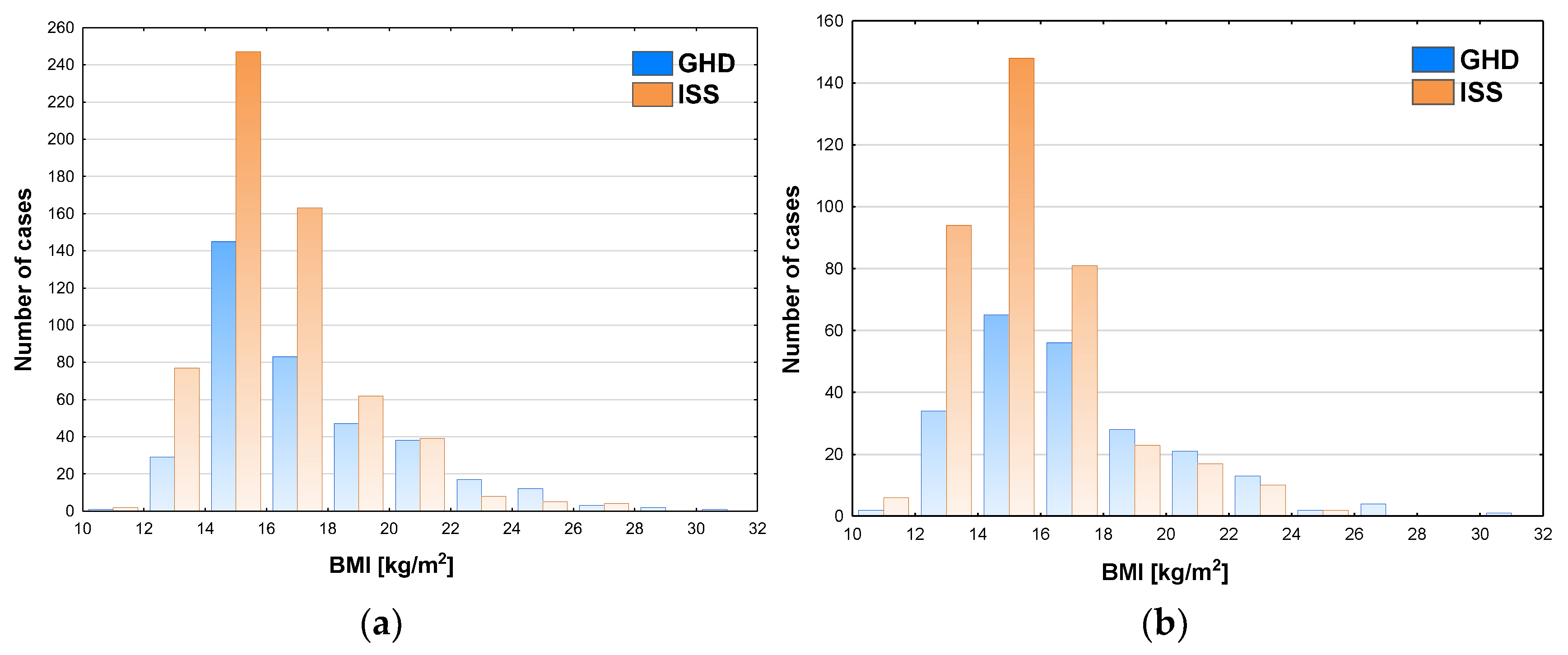

The incidence of GHD increased with BMI, both in boys and in girls; in boys it reached almost 50% (exactly 49.4%) at BMI 20-22 kg/m

2 and over 50% at higher values of BMI (see

Figure 4a), while in girls it exceeded 50% in the patients with BMI over 18 kg/m

2 (see

Figure 4b).

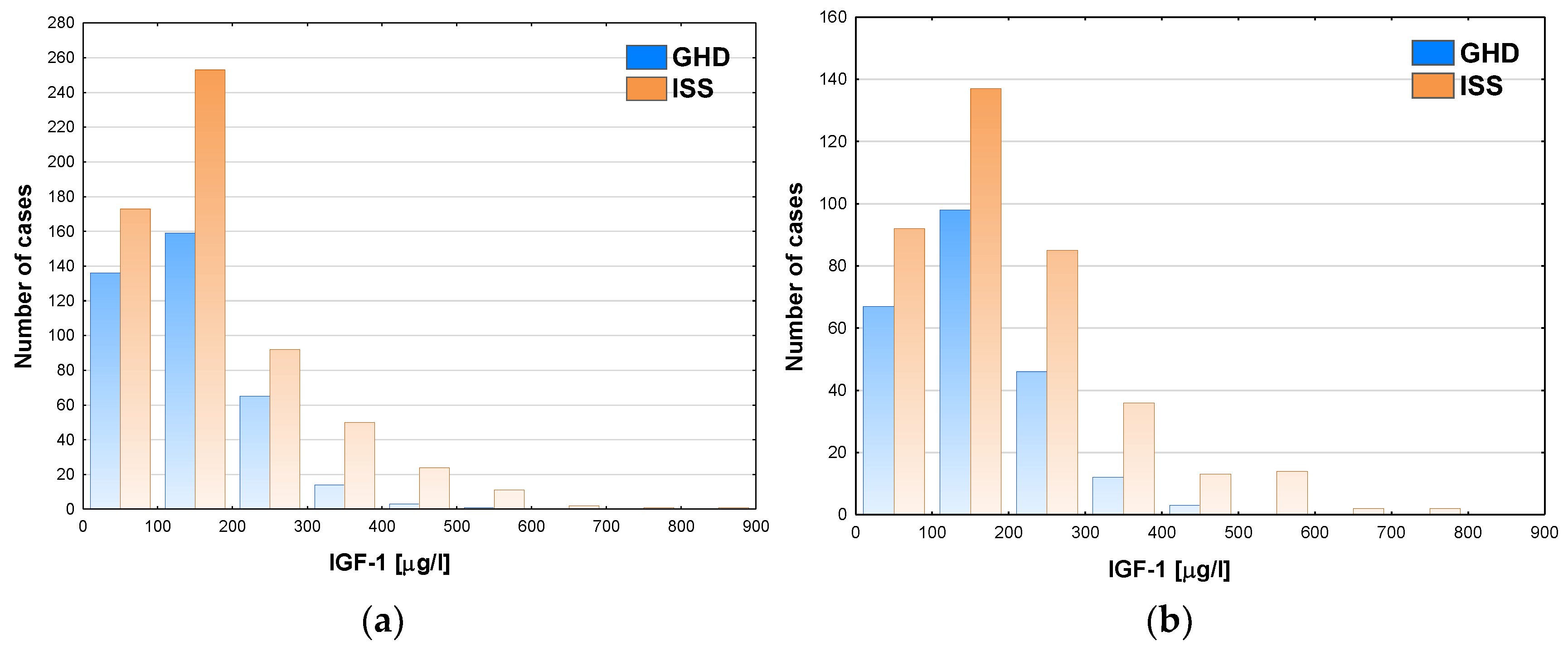

The incidence of GHD decreased with the increase of IGF-1, however even in the groups with the lowest IGF-1 concentrations it was below 50% (see

Figure 5a for boys and

Figure 5b for girls).

3.2. Relationships Between Nutritional Status and Results of the Tests of Somatotropic Axis

Second part of the analysis was devoted to assessment of relationships between nutritional status, the results of GHST and IGF-1 concentrations. As in children both BMI and IGF-1 concentrations are variables of known correlation with age, all BMI and IGF-1 values were expressed as SDS for age and sex.

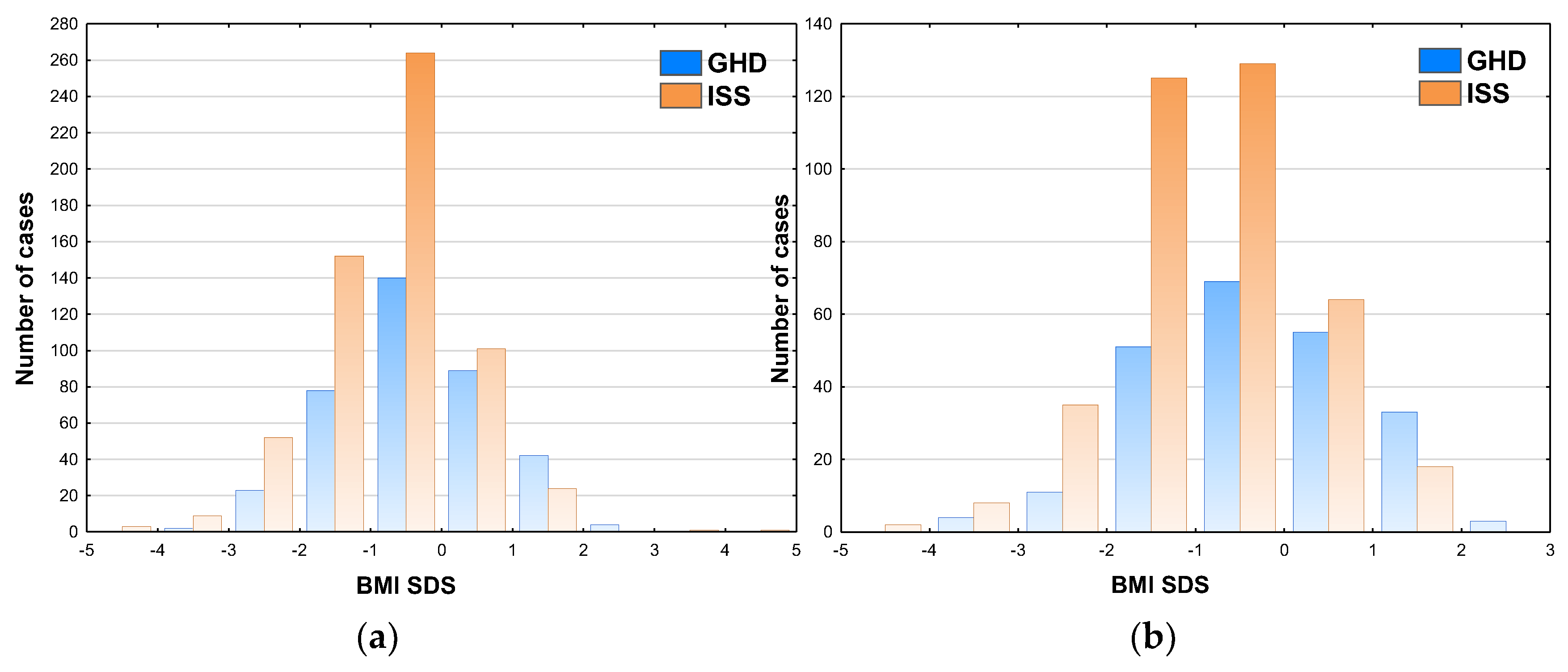

The relationships between BMI SDS and GH peak in GHST were similar to these between raw BMI values and GH peak, with the incidence of GHD even exceeding 50% at BMI SDS over 1.0 in both sexes (see

Figure 6a for boys and

Figure 6b for girls).

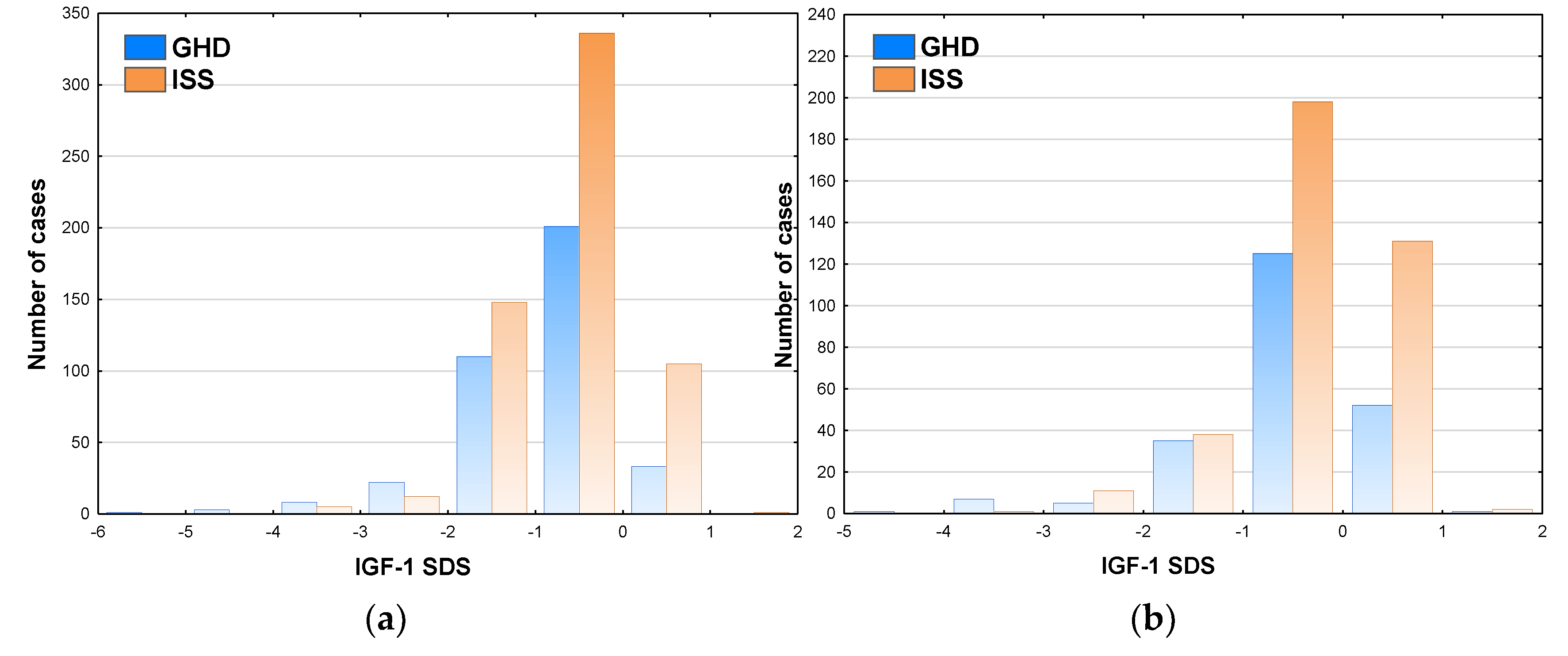

The incidence of GHD exceeded 50% only in the patients with IGF-1 SDS below -2.0 (see

Figure 7a for boys and

Figure 7b for girls). It should be noted that 23.9% of boys and 28.5% of girls with IGF-1 SDS over 0.0 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of GHD based on the results of GHST.

Next, the patients were classified according to nutritional status into the following Groups: Norm – normal weight, BMI SDS from -2.0 to 1.0; Under – underweight, BMI SDS below -2.0; Over – overweight, BMI SDS over 1.0 (see

Table 3). It should be noted that the patients with obesity, i.e. with BMI SDS over 2.0, were included into Over Group, due to relatively small number of such cases (four boys and three girls with GHD, and two boys with ISS). The incidence of undernutrition was 6.5% in GHD group and 10.9% in ISS Group. Conversely, the incidence of overnutrition (or obesity) was 13.4% in GHD group and only 4.4% in ISS group (for detailed raw data see

Table 3).

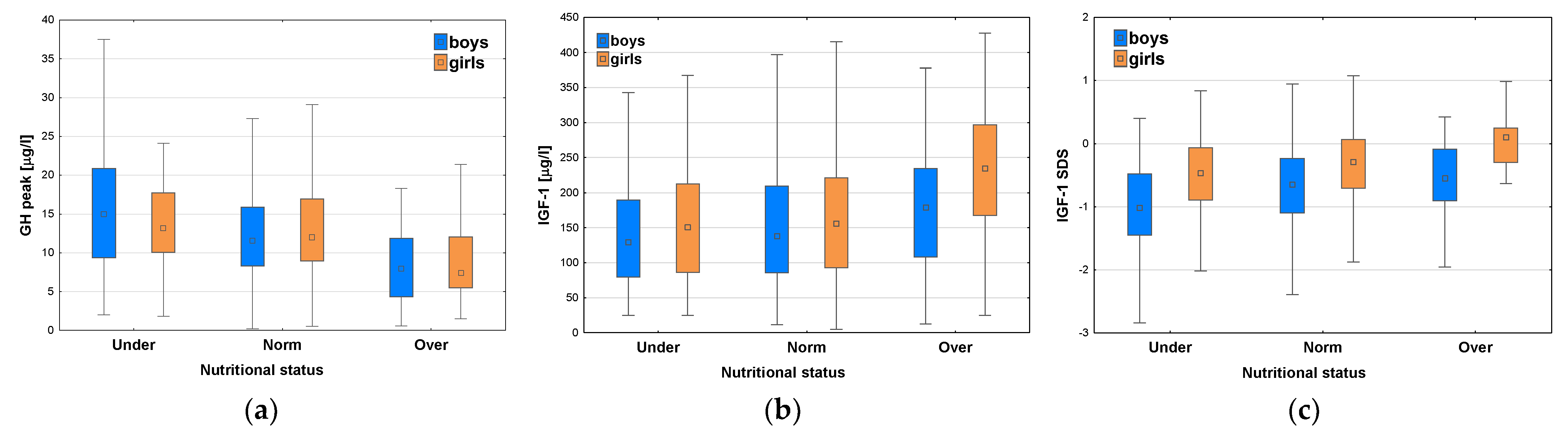

After classifying the patients with respect to nutritional status, significant differences were observed in GH peak for the whole group (p<0.001), as well as both for boys (p <0.001) and for girls (p<0.001); in post-hoc analysis all the differences between particular subgroups presented to be significant, except for this between Groups Norm and Under in girls (see

Table 4 and

Figure 8a).

Significant differences were also observed in IGF-1 concentrations with respect to nutritional status for the whole group (p<0.001), as well as both for boys (p = 0.02) and for girls (p<0.001); post hoc analysis showed that there was no significant difference in IGF-1 levels between Groups Norm and Under, while all the differences between Groups Over and Under were significant (p<0.001 for the whole group and for girls, p = 0.02 for boys) (see

Table 4 and

Figure 8b). Similarly, significant differences were observed in IGF-1 SDS among the groups with different nutritional status for the whole group (p<0.001), as well as both for boys (p <0.001) and for girls (p<0.001); in post-hoc analysis all the differences between particular subgroups presented to be significant, except for these between Norm and Over in boys, and between Norm and Under in girls (see

Table 4 and

Figure 8c). It should be stressed that median GH peak was lower, while median IGF-1 and median IGF-1 SDS were higher in Group Over than in Group Norm, whereas Group Under had the highest median GH peak together with the lowest median IGF-1 concentration and median IGF-1 SDS (see

Table 4 and

Figure 8a-c).

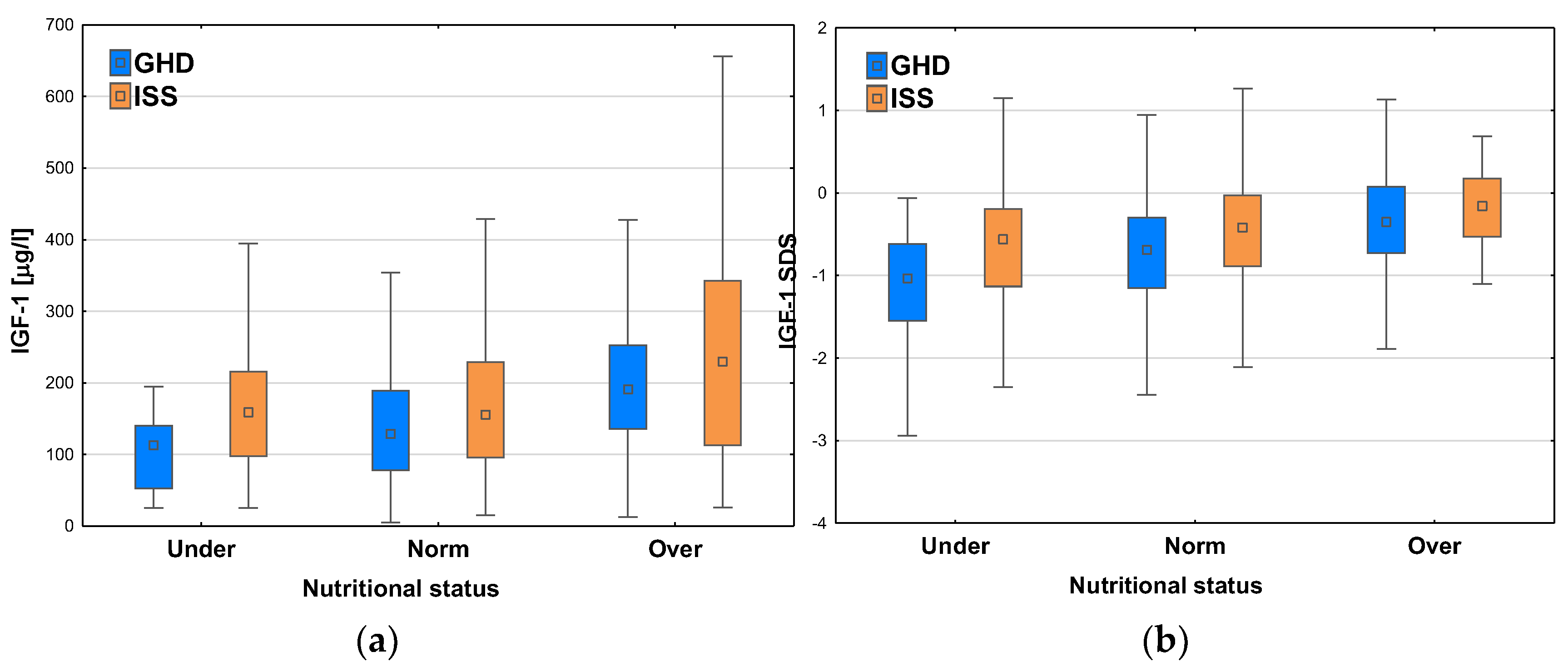

After dividing the patients with respect to the diagnosis, we observed the similar relationships between IGF-1 concentrations and nutritional status, i.e. higher values of median IGF-1 in Groups with higher BMI SDS. The patients with GHD had lower IGF-1 levels and lower IGF-1 SDS than ones with ISS in each category of nutritional status. Nevertheless, it should be noted that both median IGF-1 concentration and median IGF-1 SDS were higher in the patients diagnosed with GHD in Group Over than in ones diagnosed with ISS in Group Norm (see

Figure 9a-b).

4. Discussion

First important finding in our study was the decrease in the frequency of GHD after exceeding certain values of age, BA and height. Taking into account that this phenomenon was observed particularly after reaching BA 12 years in boys and 10 year in girls or height over 150 cm in boys and 140 cm in girls, it seems that it could be related to the physiological increase of GH secretion at mid-puberty rather than to real self-healing of the patients suffering from real GHD. It is well known from over 30 years that spontaneous GH secretion increases at puberty due to higher rate of GH release during secretory bursts [

27,

28]. In order to overcome this problem, it was proposed also 30 years ago to perform sex steroid priming before GHST in selected groups of prepubertal children [

29]. This approach has been confirmed in the Guidelines of Pediatric Endocrine Society from 2016 [

1], as a solution to avoid qualifying to recombinant human GH (rhGH) therapy children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP), however, with the comment that clinical practice was different in different countries. On the other hand, there are some concerns that the results of primed GHST may overestimate GH secretion and lead to false negative results of these tests [

30]. Problems related to optimal use of sex steroid priming in clinical practice have been discussed in a quite recent paper of Partenope et al. [

31]. It should be mentioned here that Poland, sex steroid priming before GHST was introduced at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, but later it has not been required in any group of children and thus was not performed in our patients. Another solution of the problem of overdiagnosis GHD in peripubertal children (especially ones with CDGP) could bring the studies on differentiation of cut-off limits of GH peak in GHST based on pubertal stage [

30]. The last but not least alternative proposed recently is reassessment of GH secretory status of rhGH-treated patients after entering puberty [

12,

32].

It should also be noted that we observed the increasing incidence of GHD with age boys aged up to 14 years and in girls aged up to 12 years (and similarly up to two years younger BA in both sexes) that could also be explained by physiological decrease of GH secretion in peripubertal period [

33]. However, a very recent paper of Chimatapu et al. [

34] brings the conception of evolving GHD as a disease that may occur in children with previously normal results of GHST. Despite different interpretation, the observations made in both studies seem quite consistent.

The results of our study confirmed known relationships between nutritional status and GH secretion [

1,

35], as higher incidence of GHD was observed in the groups of patients with higher values of BMI and, accordingly, overweight children had lower GH peaks in GHST than those with normal weight or underweight.

Despite the fact that GHD was defined as secondary IGF-1 deficiency in “The ESPE Classification of Paediatric Endocrine Disorders” over 20 years ago [

3], significance of IGF-1 assessment and interpretation of this test in diagnosing GHD is still a matter of discussion. In the previously quoted Guidelines from 2016 [

1], measurement of IGF-1 concentrations is recommended but mainly as a tool for monitoring the adherence to treatment and for lowering too high rhGH doses, however with no established optimal target levels of IGF-1 during treatment. In 2022, Wit et al. [

2] have proposed to measure IGF-1 during laboratory screening for GHD and interpreting the obtained results with respect to pubertal stage. The meta-analysis of diagnostic value of IGF-1 in GHD showed that IGF-1 SDS below -2.0 had quite good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis based on the results of GHST [

36]. Similarly, in our study the incidence of GHD exceeded 50% only in the patients with IGF-1 SDS below -2.0.

Data on the relationships of GH and IGF-1 secretion with nutritional status are not consistent. In the study of Stanley et al. [

35], BMI SDS correlated inversely with GH peak, while there was no association between GH peak and IGF-1. According to the review of Savastano et al. [

37], obesity led to the reduced GH response in GHST that might result in reduced IGF-1 levels. The inverse association between BMI SDS and GH peak in GHST has also been confirmed in a large group of patients by Thieme at al. [

38]. Based on results of meta-analysis, Abawi et al. [

39] have proposed weight- adjusted (lower) cut-offs of GH peak in GHST for children with overweight and obesity.

In a study including 9400 serum samples, Horenz et al. [

40] have stated that in obese children IGF-1 levels were higher, while in obese adults – lower than in appropriate reference groups with normal nutritional status. Conversely, very recently, Negrea et al. [

41]. have reported that IGF-1 concentrations depended on age, while not on weight status of children. In this context, somewhat surprising were the relationship between GH peak and IGF-1 concentrations observed in our study after stratifying the patients with respect to their nutritional status. Overweight children as a group had the lowest median GH peak with the highest values of IGF-1 (and IGF-1 SDS), while – conversely – underweight ones had the highest median GH peak and the lowest IGF-1 (and IGF-1 SDS). It should be stressed that both the median IGF-1 level and the median value of IGF-1 SDS were even slightly higher in overweight children diagnosed with GHD than in non-overweight children diagnosed with ISS. These findings stay in line with the observation that, in children with obesity, weight loss has been associated with the increase of GH secretion, but not unequivocally with an increase of IGF-1 [

42].

The postulated explanation of these findings might be the promoting effect of hepatic insulin on GH sensitivity, and through this on liver IGF-1 production [

43], however it was not a subject of our research. Additional support to this statement could be better growth response to rhGH therapy in children with children with higher BMI SDS [

44,

45].

It seems also important that – according to current knowledge – the diagnosis of GHD is considered unlikely in children with IGF-1 SDS over 0.0 [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, every fourth of our overweight patients (i.e. those with IGF-1 SDS over 0.0) had decreased GH peak in two GHST and fulfilled the assumed criteria of GHD.

It should be recalled here that in our study the cut-off value of GH peak in two GHST for the diagnosis of GHD was established at the level of 10.0 µg/l. Undoubtedly, using lower cut-offs for interpretation of GHST, as proposed in current guidelines [

1,

23], should decrease the number of children diagnosed with GHD and subjected to rhGH therapy. Nevertheless there is no recommendation to use different cut-offs for different age groups. There are some proposals of decreasing the threshold values of GH peak in GHST in overweight or obese patients, but such lower cut-offs have not been clearly recommended for children. There is the evidence that IGF-1 concentrations should be interpreted with respect to age, sex and pubertal stage. Taking into account the results of present study it seems that taking into account nutritional status of the patient might improve diagnostic accuracy of this test.

The most important limitations of our study are: missing pubertal assessment in some patients, the lack of exact data on height velocity of the patients (especially in some children with ISS who were lost to follow-up) and no reports on parental heights in some patients. In a retrospective study, covering a multi-year period, there was no possibility to complete this information in a reliable manner. This made impossible to include these potentially significant variables in the analysis.

5. Conclusions

The assumption of the same cut-off value of GH peak for all GHST, irrespectively of patient’s age (and related parameters as height and bone maturation) or nutritional status, led to the significant differences in the incidence of GHD (in fact – of fulfilling the established diagnostic criteria of this disease) among children with short stature, stratified with respect to these variables. It seems that this approach should be modified by personalizing the interpretation of the results of GHST. Further studies are necessary to fully explain the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the observed relationships between nutritional status, the results of GHST and IGF-1 concentrations, and to establish proper cut-offs not only for the results of GHST, but possibly also for IGF-1 levels.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, J.S. and R.S.; methodology, J.S; validation, M.H. and R.S.; investigation, J.S., M.H. and R.S.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital–Research Institute in Lodz, Poland.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Grimberg, A.; DiVall, S.A.; Polychronakos, C.; Allen, D.B.; Cohen, L.E.; Quintos, J.B.; Rossi, W.C.; Feudtner, C.; Murad, M.H. Guidelines for Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Treatment in Children and Adolescents: Growth Hormone Deficiency, Idiopathic Short Stature, and Primary Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Deficiency. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2016, 86, 361–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, J.M.; Bidlingmaier, M.; de Bruin, C.; Oostdijk. W. A Proposal for the Interpretation of Serum IGF-I Concentration as Part of Laboratory Screening in Children with Growth Failure. 2020, 12, 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Wit, J.M.; Ranke, M.B.; Kelnar, C.J.H. The ESPE classification of paediatric endocrine diagnoses. Horm. Res. 2007, 68, 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mameli, C.; Guadagni, L.; Orso, M.; Calcaterra, V.; Wasniewska, M.G.; Aversa, T.; Granato, S.; Bruschini, P.; d’Angela, D.; Spandonaro, F.; Poilstena, B.; Zuccotti, G. Epidemiology of growth hormone deficiency in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Endocrine 2024, 85, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, J.M. Incidence of growth hormone deficiency. Arch. Dis. Child. 1974, 49, 904–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhs, J.W.; Dhejne, C.; Magnusson, C.; Dal, H.; Lundin, A.; Arver, S.; Dalman, C.; Kosidou, K. Proportion of adults in the general population of Stockholm County who want gender-affirming medical treatment. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Massa, G.; Craen, M.; de Zegher, F.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Heinrichs, C.; De Schepper, J.; Du Caju, M.; Thiry-Counson, G.; Maes, M. Prevalence and demographic features of childhood growth hormone deficiency in Belgium during the period 1986-2001. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 151, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, R.; Feldkamp, M.; Harris, D.; Robertson, J.; Rallison, M. Utah Growth Study: growth standards and the prevalence of growth hormone deficiency. J. Pediatr. 1994, 125, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harju, S.; Saari, A.; Sund, R.; Sankilampi, U. Epidemiology of Disorders Associated with Short Stature in Childhood: A 20-Year Birth Cohort Study in Finland. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 14, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio, A.; Rotondi, D.; Da Cas, R.; Pricci, F.; Traversa, G. [Somatropin therapy in Italy during 2019-2022: prevalence and incidence rates estimated by data from the national register and regional health sources]. Recenti Prog. Med. 2024, 115, 511–516 [in Italian]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, G.M.; Morris, P.A.; Rosenfeld, R.G. When Is a Positive Test for Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency a True-Positive Test? Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 94, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D.B. Diagnosis of Growth Hormone Deficiency Remains a Judgment Call-and That Is Good. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 94, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.G.; Dattani, M.T.; Clayton, P.E. Controversies in the diagnosis and management of growth hormone deficiency in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamoun, C.; Hawkes, C.P.; Grimberg, A. Provocative growth hormone testing in children: how did we get here and where do we go now? J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 34, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyczyńska, J.; Hilczer, M.; Smyczyńska, U.; Lewiński, A.; Stawerska, R. Transient Isolated, Idiopathic Growth Hormone Deficiency—A Self-Limiting Pediatric Disease with Male Predominance or a Diagnosis Based on Uncertain Criteria? Lesson from 20 Years’ Real-World Experience with Retesting at One Center. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavarzere, P.; Gaudino, R.; Sandri, M.; Ramaroli, D.A.; Pietrobelli, A.; Zaffanello, M.; Guzzo, A.; Salvagno, G.L.; Piacentini, G.; Antoniazzi, F. Growth hormone retesting during puberty: a cohort study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 182, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penta, L.; Cofini, M.; Lucchetti, L.; Zenzeri, L.; Leonardi, A.; Lanciotti, L.; Galeazzi, D.; Verrotti, A.; Esposito, S. Growth hormone (GH) therapy during the transition period: Should we think about early retesting in patients with idiopathic and isolated GH deficiency? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciari, E.; Tassoni, P.; Parisi, G.; Pirazzoli, P.; Zucchini, S.; Mandini, M.; Cicognani, A.; Balsamo, A. Pitfalls in diagnosing impaired growth hormone (GH) secretion: retesting after replacement therapy of 63 patients defined as GH deficient. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 74, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palczewska, I.; Niedźwiecka, Z. Indices of somatic development of children and adolescents in Warsaw. Med. Wieku Rozwoj. 2001, Suppl S1, 17–118 [in Polish]. [Google Scholar]

- Kułaga, Z.; Litwin, M.; Tkaczyk, M.; Palczewska, I.; Zaja̧czkowska, M.; Zwolińska, D.; Krynicki, T.; Wasilewska, A.; Moczulska, A.; Morawiec-Knysak, A.; Barwicka, K.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Napieralska, E.; Pan, H. Polish 2010 growth references for school-aged children and adolescents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2011, 170, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułaga, Z.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Góźdź, M.; Wojtyło, M.; Świąder, A.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Litwin, M. Polish 2012 growth references for preschool children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greulich, W.W.; Pyle, S.I. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist; 2nd ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, 1993; ISBN 9780804703987.

- Collett-Solberg, P.F.; Ambler, G.; Backeljauw, P.F.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Biller, B.M.K.; Boguszewski, M.C.S.; Cheung, P.T.; Choong, C.S.Y.; Cohen, L.E.; Cohen, P.; Dauber, A.; Deal, C.L.; Gong, C.; Hasegawa, Y.; Hoffman, A.R.; Hofman, P.L.; Horikawa, R.; Jorge, A.A.L.; Juul, A. Kamenický, P.; Khadilkar, V.; Kopchick, J.J.; Kriström, B.; Lopes, M.L.A.; Luo, X.; Miller, B.S.; Misra, M.; Netchine, I.; Radovick, S.; Ranke, M.B.; Rogol, A.D.; Rosenfeld, R.G.; Saenger, P.; Wit, J.M.; Woelfle, J. Diagnosis, Genetics, and Therapy of Short Stature in Children: A Growth Hormone Research Society International Perspective. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2019, 92, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. Introducing the Restandardized Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (IGF-I) Assay. Cust. Bull. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Elmlinger, M.W.; Kühnel, W.; Weber, M.M.; Ranke, M.B. Reference ranges for two automated chemiluminescent assays for serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3). Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004, 42, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, W.F.; Schweizer, R. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins. In Diagnostics of Endocrine Function in Children and Adolescents; Ranke, M.B., Ed.; Karger, Basel, 2003; pp. 166–169.

- Martha, P.M.J.; Gorman, K.M.; Blizzard, R.M.; Rogol, A.D.; Veldhuis, J.D. Endogenous growth hormone secretion and clearance rates in normal boys, as determined by deconvolution analysis: relationship to age, pubertal status, and body mass. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 74, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.R.; Municchi, G.; Barnes, K.M.; Kamp, G.A.; Uriarte, M.M.; Ross, J.L.; Cassorla, F.; Cutler, G.B.J. Spontaneous growth hormone secretion increases during puberty in normal girls and boys. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991, 73, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.; Domené, H.M.; Barnes, K.M.; Blackwell, B.J.; Cassorla, F.G.; Cutler, G.B.J. The effects of estrogen priming and puberty on the growth hormone response to standardized treadmill exercise and arginine-insulin in normal girls and boys. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994, 79, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, M.; Rapaport, R. Growth Hormone Stimulation Testing: To Test or Not to Test? That Is One of the Questions. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 902364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partenope, C.; Galazzi, E.; Albanese, A.; Bellone, S.; Rabbone, I.; Persani, L. Sex steroid priming in short stature children unresponsive to GH stimulation tests: Why, who, when and how. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 1072271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettell, E.; Högler, W.; Woolley, R.; Cummins, C.; Mathers, J.; Oppong, R.; Roy, L.; Khan, A.; Hunt, C.; Dattani, M. The Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) Reversal Trial: effect on final height of discontinuation versus continuation of growth hormone treatment in pubertal children with isolated GHD—a non-inferiority Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT). Trials 2023, 24, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuralli, D.; Gonc, E.N.; Ozon, Z.A.; Alikasifoglu, A.; Kandemir, N. Clinical and laboratory parameters predicting a requirement for the reevaluation of growth hormone status during growth hormone treatment: Retesting early in the course of GH treatment. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2017, 34, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimatapu, S.N.; Sethuram, S.; Samuels, J.G.; Klomhaus, A.; Mintz, C.; Savage, M.O.; Rapaport, R. Evolving growth hormone deficiency: proof of concept. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2024, 15, 1398171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T.L.; Levitsky, L.L.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Misra, M. Effect of body mass index on peak growth hormone response to provocative testing in children with short stature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4875–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J. Diagnostic value of serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in growth hormone deficiency: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastano, S.; Di Somma, C.; Barrea, L.; Colao, A. The complex relationship between obesity and the somatropic axis: the long and winding road. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2014, 24, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieme, F.; Vogel, M.; Gausche, R.; Beger, C.; Vasilakis, I.A.; Kratzsch, J.; Körner, A.; Kiess, W.; Pfäffle, R.W. The Influence of Body Mass Index on the Growth Hormone Peak Response regarding Growth Hormone Stimulation Tests in Children. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 95, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawi, O.; Augustijn, D.; Hoeks, S.E.; de Rijke, Y.B.; van den Akker, E.L.T. Impact of body mass index on growth hormone stimulation tests in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 58, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horenz, C.; Vogel, M.; Wirkner, K.; Ceglarek, U.; Thiery, J.; Pfaffle, R.; Kiess, W.; Kratzsch, J. BMI and Contraceptives Affect New Age-, Sex-, and Puberty-adjusted IGF-I and IGFBP-3 Reference Ranges Across Life Span J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2991–e3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negera, M.O.; Neamtu, B.; Costea, R.; Teodoru, M.; Domnariu, C. IGF-1 Levels are Dependent on Age, but Not Weight Status in Children. Maedica (Bucur). 2023, 18, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, D.; Wei, C.; Holland-Fischer, P.; Kristensen, K.; Rittig, S.; Lange, A.; Hørlyck, A.; Solvig, J.; Grønbæk, H.; Birkebæk, N.H.; et al. Effects of lifestyle intervention on IGF-1, IGFBP-3, and insulin resistance in children with obesity with or without metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijenhuis-Noort, E.C.; Berk, K.A.; Neggers, S.J.C.M.M.; van der Lely, A.J. The Fascinating Interplay between Growth Hormone, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1, and Insulin. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2024, 39, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroszczuk, T.; Kapała, J.M.; Sitarz, A.; Kącka-Stańczak, A.; Charemska, D. Does excessive body mass affect the rhGH therapy outcomes in GHD children? Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes. Metab. 2024, 30, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budzulak, J.; Majewska, K.A.; Kędzia, A. BMI z-score as a prognostic factor for height velocity in children treated with recombinant human growth hormone due to idiopathic growth hormone deficiency. Endocrine 2024, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).