1. Introduction

Bone turnover markers represent the most common form of bone metabolism responses in osteoporosis. Biochemical markers of bone remodeling may be useful in the clinical investigation of bone turnover in children [

1].

There are planty of studies concerning bone mineralization in children born small for gestational age (SGA). Van de Lagemaat showed that six months post-term SGA preterms have lower bone accretion and in another work she proved decreased collagen type I synthesis in SGA children [

2,

3]. Longhi also confirmed that children born as SGA seem to have smaller and weaker bones [

4]. SGA children had lower BMD in mid-childhood compared to AGA in Nordman as well as in Maruyama study [

5,

6]. In Buttazzoni work we can read that preterm SGA individuals are at risk of reaching low adult bone mass, partly due to a deficit in the accrual of bone mineral during growth [

7]. Balasuriya confirmed that low birth weight groups displayed lower peak bone mass and higher frequency of osteopenia/ osteoporosis [

8]. Serum carboxyterminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PICP) and cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen ( ICTP) were similar in SGA and AGA group infants but lower BMC and osteocalcin were found in SGA children [

9]. In Rojo-Trejo study we also can read about lower BMC and BMD in SGA children than in AGA [

10]. Finaly Silvano proved that COLIA1 polimorphism could be useful predictor of osteopenia in SGA children [

11].

Therapy with growth hormone clearly increase bone formation and resorption markers [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Bone turnover markers can also be an important efficacy parameter in growth hormone therapy. Previous research has confirmed the beneficial effect of growth hormone on bone turnover markers. Administration of growth hormone improved growth velocity and final height, accelerated the process of bone growth, which is related to structural bone modelling, both in formation and resorption [

23,

24]. Rauch study conclusion were that bone markers and collagen metabolism give some early indication of therapeutic succes of GH therapy in children with GH deficiency, but the prediction of an individual marker is too imprecise [

25]. Factors underlying these processes are still unclear. Most studies were conducted in children with growth hormone deficiency (GHD), rare with idiopathic short staure (ISS) [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

25,

27].

The effect of growth hormone therapy (GHT) on bone turnover in children with small for gestational age has been assessed only in several studies [

24,

28,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. P1NP (N-terminal procollagen type 1), CTX (C-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I), P3NP (N-terminal procollagen type III) and NT-pro-CNP (amino-terminal C-type natriuretic peptide) seems very promising [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The study evaluated the capacity of these markers to predict early growth response to GHT in short stature children born with SGA. We also evaluated the Ca-P metabolism in these processes.

2. Study Population and Methods

2.1. Study Population

A total of 25 prepubertal small for gestational age (SGA) children participated in the study (age 7.6 years ±1.8). Children were born at 36.4 Hbd ±4.11 with body weight of 1776.5 g ±699 (-3.3SD) and body length of 449 cm±6.9 (-1.2SD). The pre-treatment height was 111.8 cm±10.3 (-2.7 SD), with weight of 16.6 kg ±3.4 (-3,34 SD) and BMI of 13.1±0.85 m2/kg (-2 SD) [

Table 1].

Inclusion criteria were: patients with SGA, growth deiciency < -2SD, with GH level (> 10 ng/mL) in two stimulation tests, prepubertal at the time of inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: children with GHD, AGA (appriopriate for gestational age), chromosomal abnormalities such as Silver-Russell syndrome, Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, etc.); thyroid and cortisol deficiency, diabetes, skeletal, urinary, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic defects; hepatic and renal failure, fractures in the last 6 months, immobilisation, pharmacotherapy, such as glucocorticoids.

2.2. Methods

All parents of our patients gave a written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (6/KBE/2016). SGA was defined as birth weight and/ or birth height < -2 SD for gestational age. Data on the history of pre- and perinatal period, as well as medical history, the curve of growth, growth velocity, parental height, and family medical history were collected. All investigations to assess short stature were done: two growth hormone stimulation tests with glucagon and arginine, IGF1, thyroid status, LFP, bHCG, transglutaminase antibody, prolactin, cortisol concentrations as well as blood karyotype in girls (all basic parameters: morfology, electrolytes, serum creatinine, urea, glucose, transaminases, GGTP, bilirubin levels). Bone age (BA), as well as head and pituitary MRI were done. GHT was conducted at the dose 0.035 mg/kg/day.

Before treatment (baseline-0), as well as at 6 and 12 months, all anthropometric measurements were done. Height was measured with the Harpenden stadiometer. BMI was expressed as weight in kg/height in m2. All measurements were calculated as z-score (ZS). BA, IGF1, as well as Ca, P, ALP, PTH, 25OHD3 levels, P1NP (procollagen I aminotherminal propeptide), Ctx (collagen type I cross-linked C-telopeptide), PIIINP (procollagen III amino-terminal propeptide), NTproCNP (amino-terminal C-type natriuretic peptide) were estimated at baseline, as well as at 6 and 12 months during treatment. BA was calculated by Greulich-Pyle'a method. IGF1 was measured by the automatic ECLIA method on Liaison. Ca-P, ALP, 25OHD3 levels were estimated using the automatic method in the IDS-iSYS closed immunodiagnostic system. 25-Hydroxy vitamin D and PTH were measured with the immunoradiometric assay (RIA).

P1NP and Ctx were estimated by automatic ECLIA method on the Elecsys apparatus. P1NP was measured by ECLIA on the Cobas e411 analyser using Roche Diagnostics' total P1NP assay. The total P1NP assay used monoclonal antibodies, recognised both the trimeric and monomeric forms of P1NP. The total assay time was 18 minutes. STable ruthenium complexes [(Ru(bpy)3)2+] and tripropylamine (TPA) were used in the chemiluminescence reaction of the Cobas e411 system. The results were read from the calibration curve prepared on the basis of a 2-point calibration (the standard curve contained in the reagent barcode). Measuring range: 5 - 1200 ng/mL; lower limit of detection: 5 ng/mL. Ctx measuring range: 0.010 - 6.00 ng/mL; lower limit of detection: 0.010 ng/mL.

P3NP assessment was done by radioimmunoassay (IRA) using the UniQ PIINP reagent kit by Aidian. The UniQ PIINP kit was based on a competitive radioimmunoassay technique.The concentration of PIIINP in the test samples was calculated from the standard curve. The radioactivity of the samples was measured on an Elmer Wizard gamma counter. Test measurement range: 1.0-50 μg/L, detection limit - 0.4 μg.

The serum level of NT-proCNP was measured by the ELISA method (Biomedica), by binding it with a coating antibody to form a Sandwich complex, followed by the addition of a substrate (TMB, tetramethylbenzidine). Colour intensity was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm (reference wavelength 630 nm) on a multifunctional Varioscan Flash reader using SkanIt Software 2.4.3. The standard curve was developed as recommended by the reagent kit manufacturer. Based on the measurements of the standards, the reader software calculates the concentration (pmol/L) of the control and test samples.Test measuring range: 0-128.0 pmol/L.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Data were analysed using Statistica PL, version 10. The results were presented as mean and standard deviation. Departure from the normality of the distribution of analysed variables was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pearson correlations were used to assess the association between variables. Adjustment was done with the linear regression model. Non-normally distributed variables were analysed after Box-Cox transformation. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

The median height of our patients before treatment was 111.8 cm (-2.7 SD), BMI was 13.1 (-2SD). At 6 months of GHT the mean height reached 115.82cm (-2.46 SD), (v1 - v2 p=0.000000) and after one year -119.93 cm (-2.19 SD), (v1- v3 p=0.000000) [

Table 2].

IGF1(ng/ml) level increased significantly at 6 and 12 months, respectively (141 vs 310 p=0.000) (141 vs 349 p=0.000) [

Table 2].

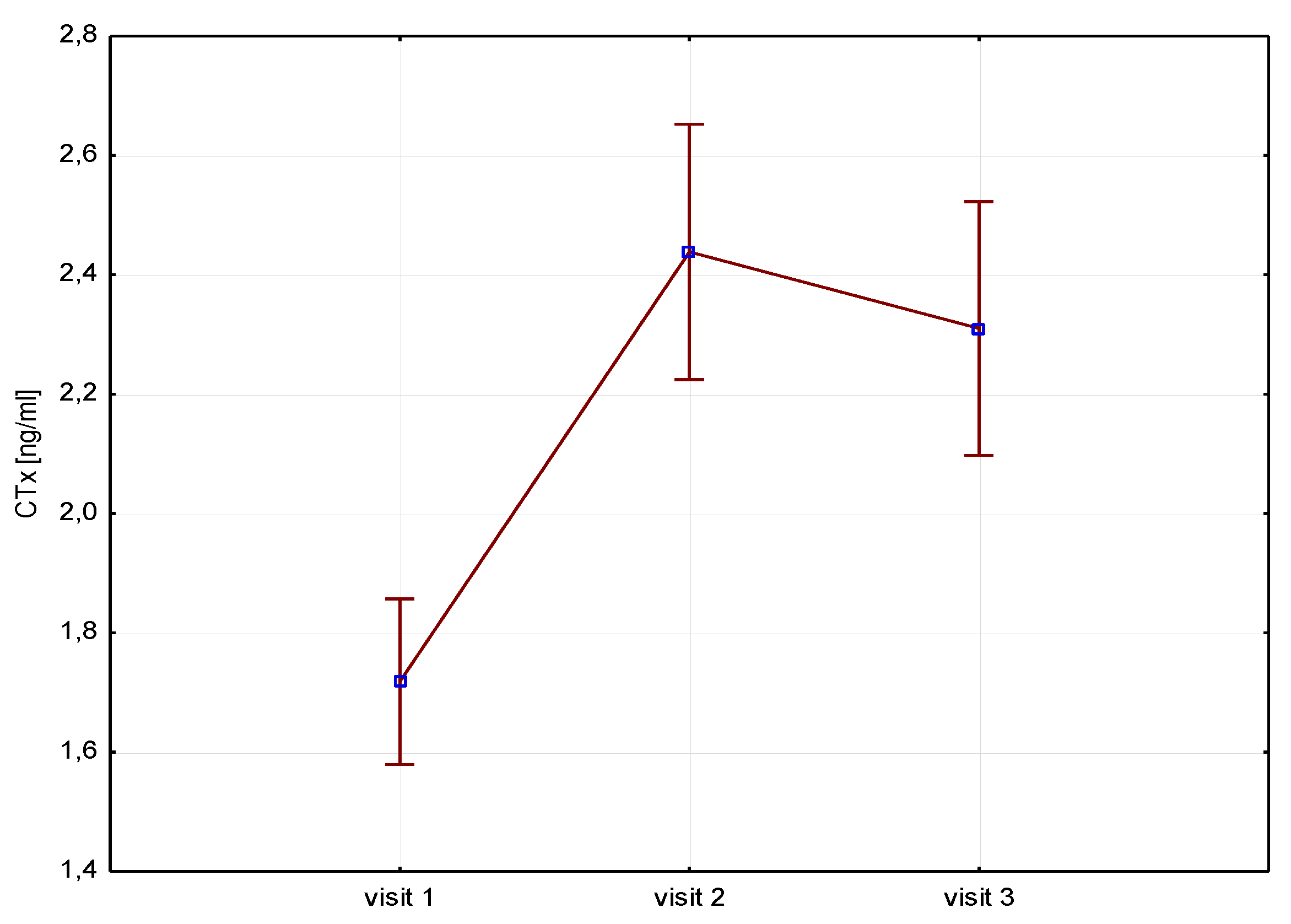

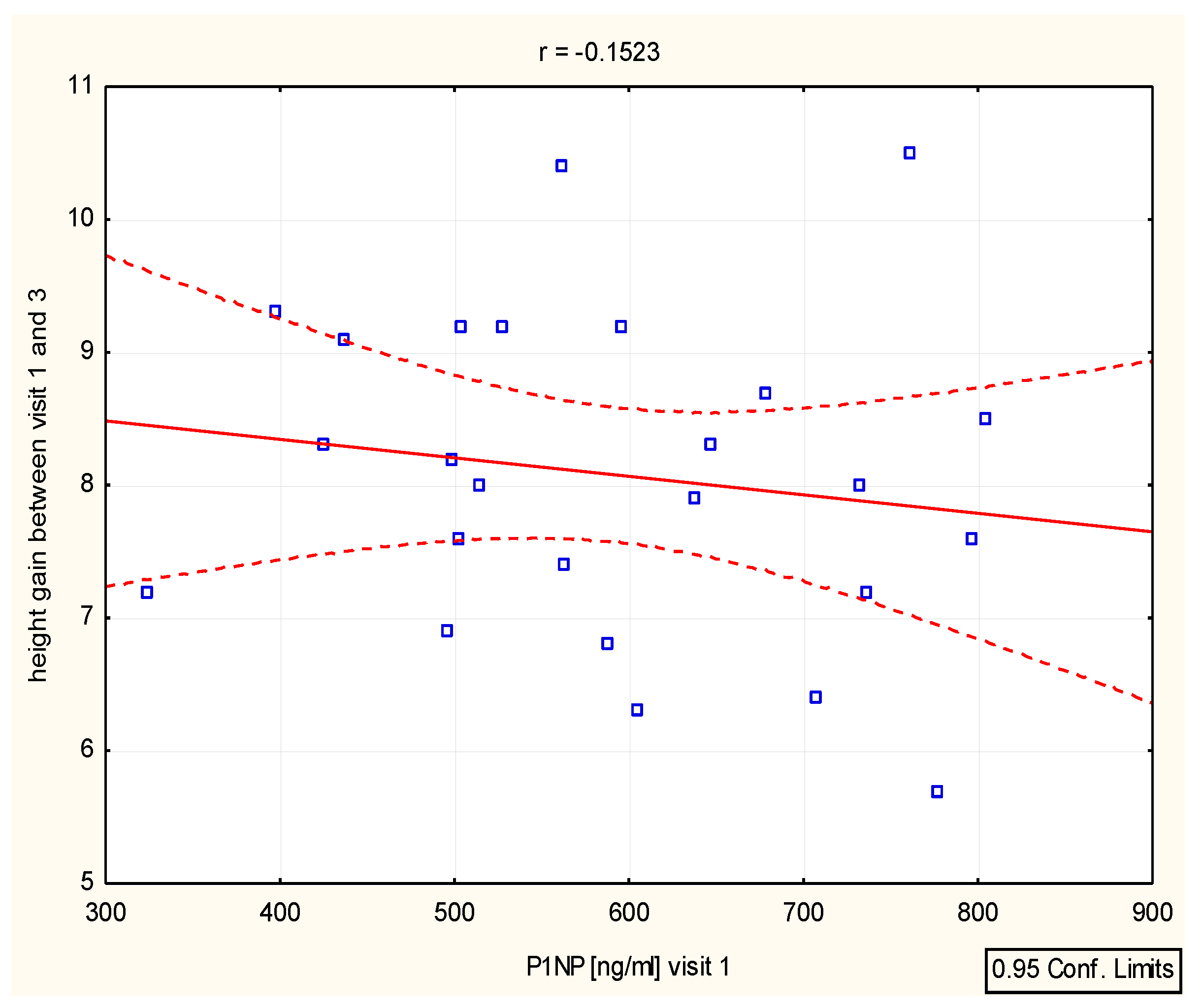

A significant increase of bone resorption markers Ctx (ng/ml) was found both at 6 months (1.7 vs 2.4 p=0.000) and 12 months (1.7 vs 2.3 p=0.000) [

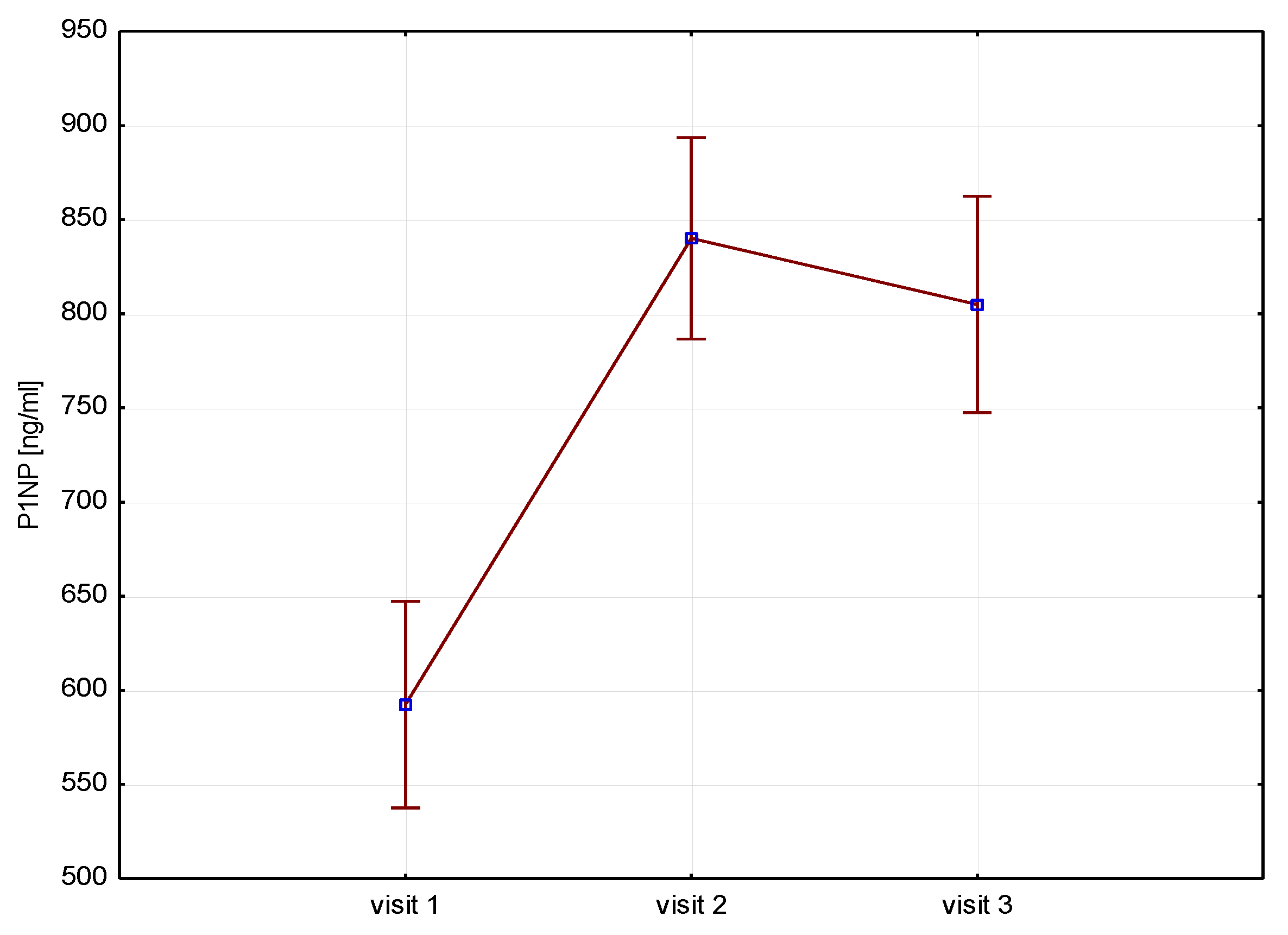

Figure 1]. P1NP (ng/ml) bone markers increased at 6 months (592 vs 840 p=0.000) and after 12 months of therapy (592 vs 804 p=0.000) [

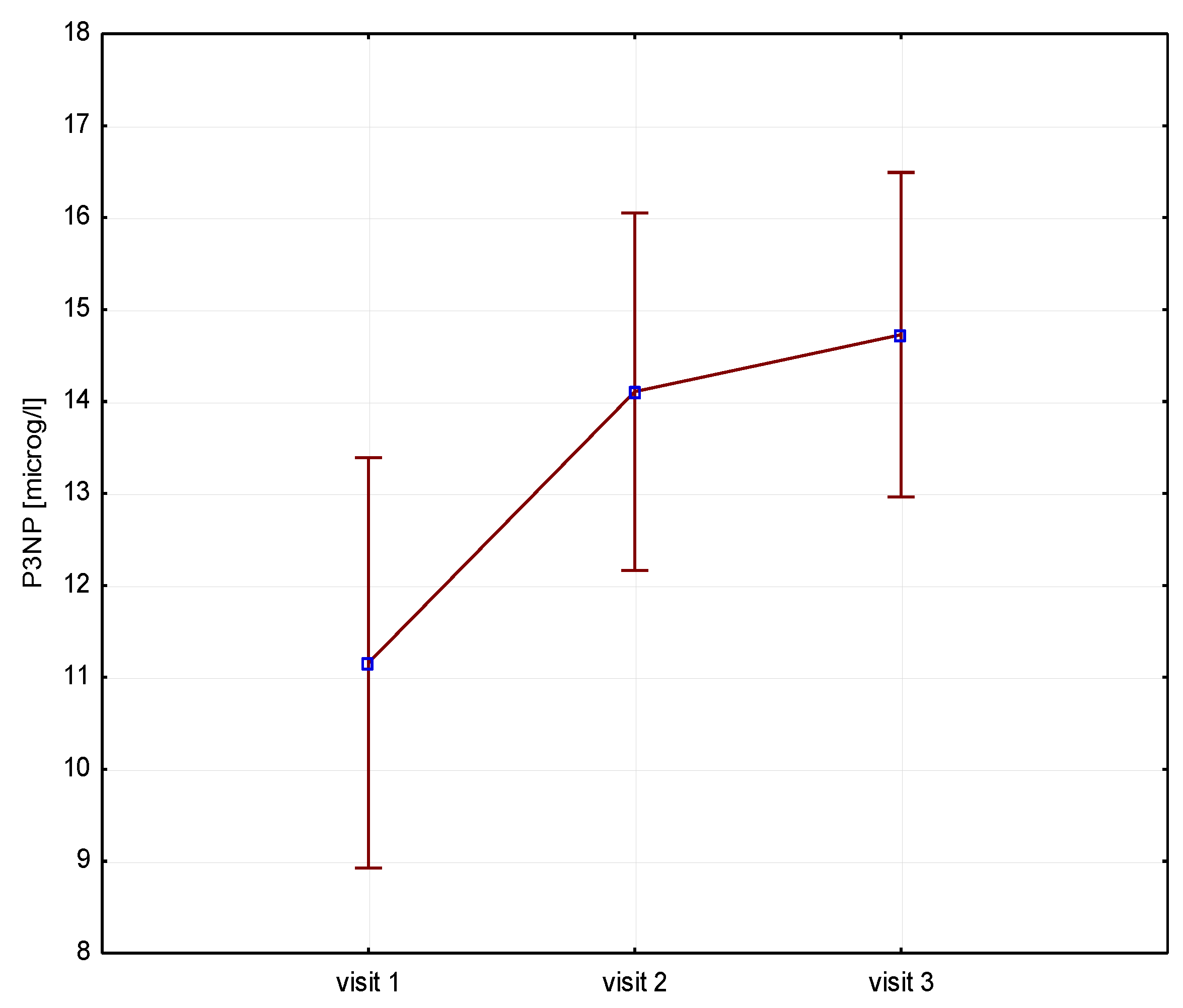

Figure 2]. The P3NP (ug/ml) marker of collagen synthesis also increased after 12 months of therapy (13 vs

In terms of Ca-P levels, we obtained significant phosphorus (ng/ml) levels increase at 6 and 12 months (1.4 vs 1.6 p = 0.000; 1.4 vs 1.6 p = 0.001), and similarly for ALP (ng/ml) levels (231 vs 277, p = 0.00013; 231vs 282 p=0.0012); the limit of 25OHD3 (ng/ml) level increased after 12 months (31 vs 35.1p=0.06). PTH (pg/ml) levels was elevated significantly after 6 and 12 months (22 vs 24.8) p=0.03) [

Table 3].

Figure 1.

Height (V1-V3) / CTx.

Figure 1.

Height (V1-V3) / CTx.

Figure 2.

Height (V1-V3)/ P1NP.

Figure 2.

Height (V1-V3)/ P1NP.

Figure 3.

Height (V1-V3)/P3NP.

Figure 3.

Height (V1-V3)/P3NP.

Correlations

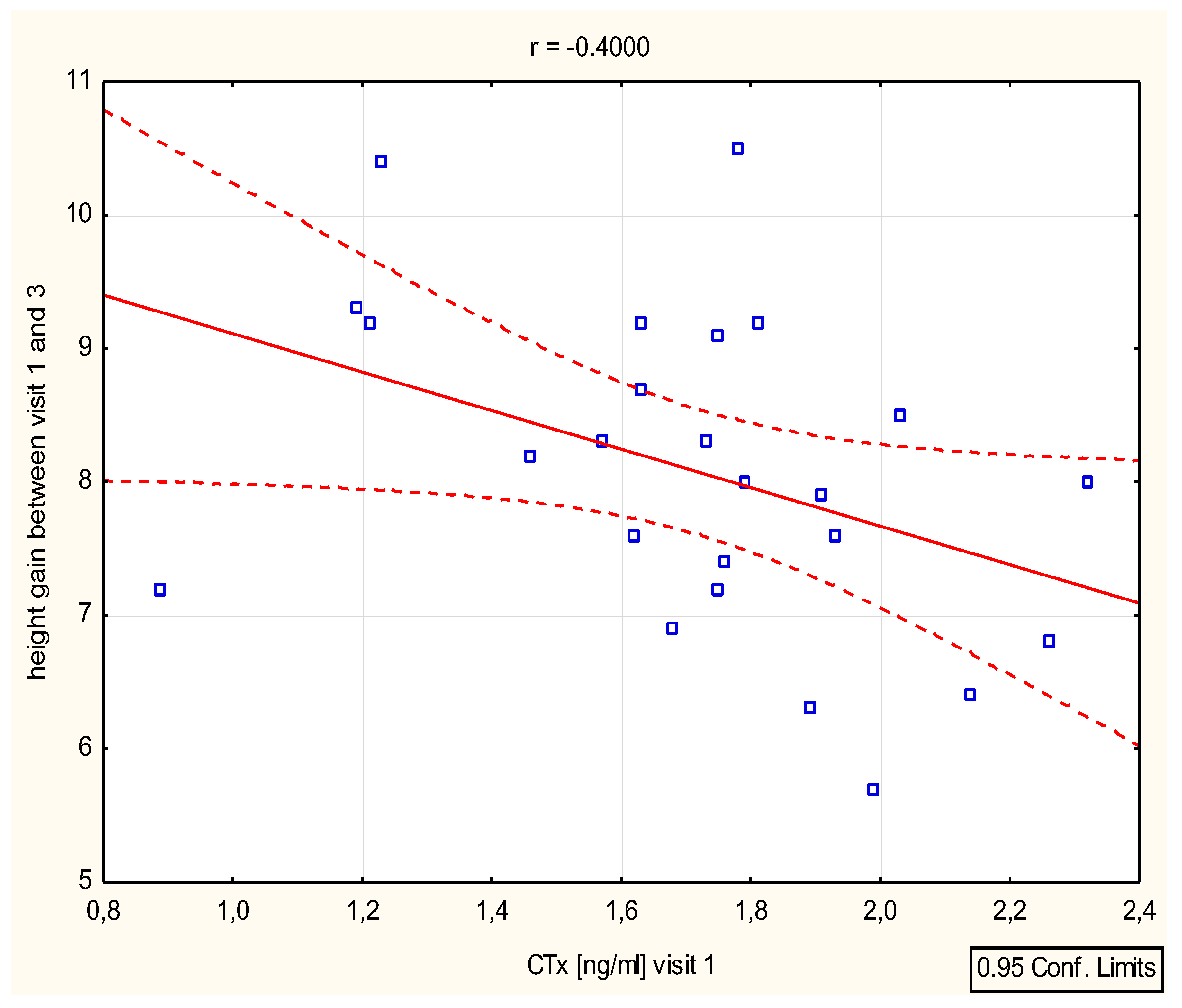

We have found a significant correlation between height (cm) and Ctx after 6 -12 months (r=0,39 p=0,046 and r=0.4, p=0.046), as well as height (SD)/Ctx : r=0.15, p=0.049 after 6 months [

Figure 4][

Table 4]. P1NP/height (SD) correlation was important after 12 months (r=0.44, p=0.025) [

Figure 5][

Table 4].

Calcium levels significantly correlated with height (SD) after 12 months (r=0.48, p=0.014) (d v1-v3 Ca/ height (SD)=0.45) [

Table 4].

4. Discussion

GH and IGF1 are anabolic peptides that increase not only growth but also muscle mass and bone development. GH has the capacity to affect body composition and bone metabolism. For many years the importance of GH on bone mass has been well documented. Bone turnover markers are markedly decreased in GHD, ISS children, whereas both osteoblast and osteoclast activity increase during GH replacement therapy [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Biochemical measurements of bone turnover may be helpful in monitoring growth process, especially during GHT. The use of bone turnover markers may be a non-invasive method in clinical practice. A lot of studies concerns GHD children. Kandemir at al found increased bone turnover markers (calcium, phosphate, ALP, osteocalcin and carboxyterminal propeptide of type 1 collagen -CPP-I) increased after 12 moths of GH therapy in 39 GHD children [

18]. Yun Li et al also has proved increased bone markers -carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 colagen (ICTP) after 6 months growth hormone therapy in 29 isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD) and partial growth hormone deficiency (PGHT) children [

19]. Baroncelli et al have estimated increased procollagen I carboxyterminal propeptide (PICP) and ICTP significantly after one year GHT in GHD prepubertal children, but after 12 months PICP declined, ICTP levels remained sTable [

20]. At Schweizer work we can find early bone remodeling in prepubertal GHD children treated by GH

A few studies estimate the improvement of bone strength during GH therapy in SGA children. Willemsen study showed that during long-term GH treatment in short SGA children bone mineral density increased.That was most prominent in children who started treatment at a younger age and in those whith greater height gain during GH treatment [

22]. The same concluison we can find in de Zegher study, the rate of bone maturation in short, pepubertal children born SGA treated with GH appeared to depend not only on the dose of GH but also on the age of the child [

23]. Lem proved that during GH treatment in SGA children bone mineral density (BMD) ncreased significantly [

31].The same conclusion had the Arends study, when GH treatment in short children born SGA increased proportionately to the height gain, bone maturation[

32].

In our study, we attempted to estimate the changes of bone markers levels during GHT and their usefulness in SGA patients treated by GH.

All patients achieved clinically significantly increased growth and IGF1 level, after one year of GHT. Our main finding shows an P1NP (bone formation marker) increase after 6 and 12 months of treatment. There is not much research on this issue in SGA children. Gascoin- Lachambre et al. in 2007 study evaluated thirty, 7-year old SGA children with height < -2 SD, put on GHT at the same dose of 0.033mg/kg/day. They also found increased P1NP, which was an early predictor of GH treatment, especially in ISS children, but also in SGA children after 6 months of therapy [

24]. Our study has also shown Ctx increase (the resorption markers) after half and one year of GHT in SGA children. The increase of bone resorption may result from a significant acceleration of bone metabolism after initiating growth hormone therapy and increasing the physiological distance between bone formation and bone resorption. Lanes et al. have suggested that PINP and Ctx were major effect of GHT in promoting bone formation [

25].

Kamp et al. assessed GH response relationship between GH and markers of bone turnover: P1CP, P3NP and ALP [

27], however the study did not include SGA children.

In Bajoria study, the authors found a positive association between IGF1 and P1CP and a negative correlation between IGF1 and ICTP in IUGR twins [

28]. In our study, we did not find any associations for P1NP, CTx and IGF1 level. We found a very strong correlation between CTx and P1NP markers and growth velocity.

In Shalender study, early serum P3NP changes were associated with GH administration and could be a useful early predictive biomarker of anabolic response to GH, but the study was not conducted in SGA children [

29]. In our study P3NP marker increased after one year of our GH therapy.

NT-proCNP was estimated as a strong marker correlated with growth velocity in children. Prickett in his study showed a direct association of NT-proCNP with the growth process. Plasma NT-proCNP was elevated at birth and fell progressively with age. The authors also emphasised the significant association between NT-proCNP and ALP level as well as Ctx [

30]. Unfortunately, we did not find any important increase in NT-proCNP or any correlation with growth velocity or IGF1.

As for the Ca-P metabolism, we found statistically significant elevation of phosphorus and ALP concentrations; Ca levels were positively correlated with growth after one year of treatment.

Bone markers are very poorly documented in children, especially in SGA patients. Even if GH and IGF1 are major factors influencing their levels, other factors are probably also involved.

5. Conclusions

A strong reaction of bone resorption and bone formation markers during growth hormone therapy may determine their selection as prediction of this treatment outcome in SGA children, However, the issue requires further research.

References

- Szulc P., Seeman E., Delmas PD. Biochemical measurements of bone turnover in children and adolescents. Osteoporos Int 2000, 11 , 281-294. [CrossRef]

- Van de Lagemaat M., Rotteveel J., van Weissenbruch. Small-for-gestational-age preterm-born infants already have lower bone mass during early infancy. Bone 2012, 51(3):441-446. [CrossRef]

- Van de Lagemaat M., van der Veer E., van Weissenbruch. Procollagen type I N -terminal peptide in preterm infants is associated with growth during the first six months post-term. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014,81 (4):551-558.

- Longhi S, Mercolini F.,Carloni L. Prematurity and low birth weight lead to altered bone geometry, strenght, and quality in children. J Endocrinol Invest 2015, 38(5): 563-568. [CrossRef]

- Nordman H.,Voutiainen R., Laitinen T. Birth size, body composition, and adrenal androgens as determinants of bone mineral density in mid-childhood. Pediatr Res 2018, 83( 5): 993-998. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama H, Amari S., Fujinaga H. Bone fracture in severe small-for-gestational-age, extremely low birth weight infants: A single- center analysis. Early Hum Dev 2017, 106-107:75-78. [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni C.,Rosengren B., Tveit M. Preterm children born small-for-gestational-age are et risk for low adult bone mass. Calcif Tissue Int 2016, 98(2): 105-113. [CrossRef]

- BalasuriyaC.,Evensen K., Mosti M. Peak bone mass and bone microarchitecture in adults born with low birth weight preterm or at term: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017: 102( 7): 2491-2500. [CrossRef]

- Namgung R.,Tsang R.,Sierra R. Normal serum indices of bone collagen biosyntesis and degradation in small for gestational age infants. J Peditar Gastroenterol Nutr 1996, 23(3): 224-228. [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Trejo M., Robles-Osorio M., Rangel B. Appendicular muscle mass index as the most important determinant of bone mineral content and density in small for gestational age children. Clin Pediatr 2024, Apr 6. [CrossRef]

- Silvano L., Miras M., Perez A. Comparative analysis of clinical, biochemical and genetic aspects associated with bone mineral density in small for-gestational age children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2011, 24(7-8): 511-517. [CrossRef]

- Lanes R. Growth velocity, final height and bone mineral metabolism of short children treated long term with growth hormone. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2000,1, 33-46. [CrossRef]

- Schönau E., Westermann F., Rauch F. et al. A new and acurate prediction model for growth response to growth hormone treatment in children with growth hormone deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol 2001, 144 (1), 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Cowell C.T., Woodhead H.J., Brody J. Bone markers and bone mineral density during growth hormone treatment in children with growth hormone deficiency. Horm Res 2000, 54, 44-51. [CrossRef]

- Hogler W., Shaw N. Childhood growth hormone deficiency, bone density, structures and fractures: scrutinizing the evidence. Clinical Endocrinology 2010, 72, 281-289. [CrossRef]

- Saggese G., Baroncelli G.I., Bertelloni S. et al. Effect of long term treatment with growth hormone on bone and mineral metabolismin children with growth hormone deficiency. J Pediatr 1993, 122, 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Ogle G.D., Rosemberg A.R., Calligerosd D. et al. Effects of growth hormone treatment for short stature on calcium homeostasis, bone mineralization and body composition. Horm Res 1994, 41, 16-20. [CrossRef]

- Kandemir N., Nazli Gonc E.,Yordam N. Responses of bone turnover markers and bone mineral density to growth hormone therapy in children with Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency and Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 15: 809-816. [CrossRef]

- Yun L., Li-qing Ch., Liang L.Effects of recombinant human growth hormone (GH) replacement therapy on bone metabolism in children with GH deficiency. 2005 ,34 (4), 312-5. [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli G., Bertelloni S., Ceccarelli C. Dynamics of bone turnover in children with GH deficiency treated with GH until final height. Eur J Endocrinol 2000, 142 (6); 549-56. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer R.,Martin D., Schwarze C. et al. Cortical bone density is normal in prepubertal children with growth hormone (GH) deficiency, but initialy decreases during GH replacement due to early bone remodeling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88 (11): 5266-72. [CrossRef]

- Willemsen R., Arends N, Bakker-van Waarde W. Long-term effects of growth hormon (GH) treatmenton body composition and bone mineral density in short children born small-for-gestational-age: six year follow up of randomized controlled GH trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007, 67(4): 485-492. [CrossRef]

- De Zegher F., Butenandt O., Chatelain P. Growth hormone treatment of short children born small for gestational age:reappraisal of the rate of bone maturation over 2 years and metanalysis of height gain over 4 years. Acta Paediatr Supp. 1997, Nov 423:207-212. [CrossRef]

- Gascoin-Lachambre G., Trivin C., Brauner R. et al. Serum procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide (P1NP) as an early predictor of the growth responsin she to growth hormone treatment: Comparison of intrauterine growth retardation and idiopathic short stature. Growth Horm 2007, 17, 194-200. [CrossRef]

- Lanes R., Gunczler P., Esaa S. et al. The effect of short- and long-term growth hormone treatment on bone mineral density and bone metabolism of prepubertal children with idiopathic short stature: a 3-year study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002 , 57, 725-30. [CrossRef]

- Rauch F., Georg M., Stabrey A. et al. Collagen markers deoxypyridinoline and hydroxylysine glycosides : pediatric reference data and use growth prediction in growth hormone -deficient children. Clinical Chemistry 2002, 48, 315-322. [CrossRef]

- Kamp G.A., Zwinderman A.H., Doorn J.V. Biochemical markers of growth hormone (GH) sensitivity in children with idiopathic short stature: individual capacity of IGF-I generation after high-dose GH treatment determines the growth response to GH. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002 , 57, 315-25. [CrossRef]

- Bajoria R., Sooranna SR., Chatterjee R. Type 1 collagen marker of bone turnover, insulin-like growth factor, and leptin in dichorionic twins with discordant birth weight.J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 4696-4701. [CrossRef]

- Shalender B., Jiaxiu He E., Miwa Kawakubo E. et al. N-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen as a biomarker of anabolic response to recombinant human GH and testosteron. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94 , 4224-4233. [CrossRef]

- Prickett T., Lynn A., Barrell G. et al. Amino-Terminal proCNP: A Putative Marker of Cartilage Activity in Postnatal Growth. Pediatric Research 2005, 58 , 334–340. [CrossRef]

- Lem A.J., Van der Kaay D.C., Hokken-Koelega A.C. Bone mineral density and body composition in short children born SGA during growth hormone and gonadotropin releasing hormone analog treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013 Jan, 98(1),77-86. [CrossRef]

- Arends N.J., Boonstra V.H., Mulder P.G. et al. GH treatment and its effect on bone mineral density, bone maturation and growth in short children born small for gestational age: 3-year results of a randomized, controlled GH trial. Clinical Endocrinology 2003, 59 , 779-787. [CrossRef]

- Gerwert U. Hoyle N. Application report P1NP. Elecsys 2010, Roche Diagnostics GmbH D-68298, Mannheim.

- Seibel M.J. Molecular markers of bone turnover: biochemical technical and analytical aspects. Osteoporos 2000, 11, S18-S29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).