1. Introduction

Cordyceps cicadae Shing (Chanhua) belongs to the genus

Cordyceps (family Clavicipitaceae, Ascomycotina).

C. cicadae, a rare traditional Chinese medicine, has been applied to treat childhood palpitation, epilepsy, convulsions, and several types of eye diseases [

1].

C. cicadae is rich in sphingolipids [

2], polysaccharides [

3], nucleosides [

4], mannitol[

5], ergosterol [

6], and other active substances. Modern medical research has demonstrated that

C. cicada possesses more potent immunoregulatory [

7] and renal functions [

8], as well as anti-diabetic[

9], anti-bacterial [

10], and anti-tumorigenic properties [

11]. Ergosterol, one of the chemical components from mycelial cells, is the predominant sterol found in most fungi[

12]. It can be divided into free ergosterol and esterified ergosterol [

13]. Ergosterol plays an important role in ensuring cell viability, membrane fluidity, membrane-binding enzyme activity, membrane integrity, and cell material transport. Meanwhile, ergosterol is a precursor of fat-soluble vitamin D

2 (VD2). When exposed to ultraviolet light, ergosterol is converted into VD

2. VD

2 is an important pharmaceutical and chemical ingredient used to prevent and treat rickets in children, osteomalacia in adults, and osteoporosis in the elderly [

14]. In addition, ergosterol has anti-cancer activities [

15], anti-tyrosinase [

16], and anti-inflammatory [

17], together with their applications in new drug formulations with antibiotics [

18]. Yajaira et al. have found that ergosterol exerts synergistic effects on cell proliferation [

19]. Slominski et al. have confirmed that ergosterol metabolites in vivo can inhibit the proliferation of skin cancer cells[

20].

Due to the limit of natural sources, liquid fermentation has become an alternative approach to obtain active components of medical fungi. In the liquid fermentation process, the nitrogen source is not only one of main the nutrient components but also a key substance regulating the metabolism of mycelium. The nitrogen source plays an important role in controlling the growth process of the

S. cerevisiae and

T. delbrueckii yeasts. The optimum nitrogen sources have three traits: a relatively shorter lag phase time, a higher maximum growth rate, and a higher maximum dissolved oxygen [

21] (Su et al., 2020). In a previous study, we have proved that urea is the most suitable nitrogen source for ergosterol synthesis by

C. cicadae [

22]. Furthermore, we have found that the expressions of many genes are changed after the

C. cicadae are cultured in the presence of CO(NH

2)

2, and the alteration of these genes plays an important role in promoting the ergosterol synthesis.

Metabonomics allows for the simultaneously qualitative analysis and quantitative measurement of all low-molecular-weight metabolites in an organism or cell in response to internal and external stimuli in an integrated biological system [

23]. Metabonomics has shown a broad application prospect in identification of biomarkers, diagnosis and prediction of disease, and elucidation of the dynamic responses of organisms to disease or environmental changes [24-30]. In recent years, the ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC-TOF/MS) technology has become a powerful tool for the separation and identification of active ingredients. UPLC-TOF/MS) technology has high chromatographic resolution, high sensitivity, high selectivity and rapid separation, and can measure the accurate mass numbers of parent and daughter ions. Therefore, UPLC-MS has been widely used in metabolomics to investigate subtle metabolite alterations in complex mixtures [31-34]. Meanwhile, multivariate statistical methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) are widely used in different types of metabolite identification. In the present study, UPLC-MS technology was applied in combination with PCA and OPLS-DA and automated processing software platform to systematically screened the intracellular and extracellular differential metabolites caused by urea response. The aims of this study is to explain the mechanism to increase of ergosterol yield in the process of

C. cicadae

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Culture Conditions

C. cicadae were gifted by the Key Laboratory of Food Science of Jiangnan University and maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) slant. The slants were incubated at 25 °C for 5 days and then stored at 4 °C. The seed medium was composed of (g/L) 20 wheat bran, 20 glucose, 10 corn flour, and 4 fish meal peptone. The control fermentation medium (CFM) was composed of (g/L) 36 wheat bran, 46 xylose, 28 fructose, 25 glycerol, 1.7 ZnSO4, and 1.8 KH2PO4. CFM+CO(NH2)2 was composed of CFM and 6.6 g/L CO(NH2)2

2.2. The Preparation of C. cicadae Samples

The biomass of

C. cicadae was prepared according to a method previously described with minor modifications [

22] (Su et al., 2021). Briefly, the slant

C. cicadae was aseptically inoculated into 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL seed culture solution. These flasks were incubated on a rotary shaker at 25 °C and 150 rpm for 72 h. The seed liquid was aseptically transferred into 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL CFM or CFM+CO(NH

2)

2 at an inoculation ratio of 10%. Subsequently, these flasks were incubated on a rotary shaker at 25 °C and 150 rpm for 94 h.

After incubation, the broth was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min. One part of the biomass (sediment) was washed with sterile water five times and stored at -80 oC for metabonomic analysis. The other part of the biomass was used to determine the intracellular ergosterol content. The supernatant was used to determine the content of extracellular ergosterol.

The biomass (100 mg) individually ground in liquid nitrogen was mixed with 2 mL 80% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid (FA) by vortexing, and the mixture was allowed to stand in the ice bath for 5 min. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 g, 4°C for 20 min. Next, 0.2 mL supernatant was diluted by the water of LC-MS grade to a solution containing 53% methanol. The samples were subsequently transferred to fresh Eppendorf tubes and then centrifuged at 15,000 g, 4 °C for 20 min. Finally, the supernatant was injected into the LC-MS/MS system.

The biomass cultured in the CFM or CFM+CO(NH2)2 was used as the control blank (CB) or the sample of urea response (NS), respectively.

2.3. The Qualitative and Quantitative Determination of Ergosterol

Briefly, 25 mL supernatant was dried to constant weight at 70 oC. The dried material was extracted by 25 mL 60% ethanol in a water bath at 75 °C for 4 h, followed by centrifugation at 12,000×g, 4 oC for 10 min. The supernatant was collected to determine the content of intracellular ergosterol.

The contents of extracellular and intracellular ergosterol were determined according to the vanillin method. Briefly, 1 mL of sample solution was mixed with 0.2 mL of 5% vanillin-glacial acetic acid solution and 0.8 mL of perchloric acid. The mixture was heated at 60 °C for 15 min, cooled to room temperature, and then reacted with 3 mL of glacial acetic acid. The absorbance was determined at a wavelength of 570 nm. Ergosterol was used as the standard.

2.4. UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis

The analytical UHPLC-MS/MS consisted of a Vanquish UHPLC system (ThermoFisher, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) as the detector and equipped with an electrospray source in both positive and negative ion modes. To acquire better signals of metabolites, the MS method was developed with a spray voltage of 3.2 kV, capillary temperature of 320°C, sheath gas flow rate of 40 arb, and aux gas flow rate of 10 arb. Samples were separated by a Hypesil Gold column (100×2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) using a 17-min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The developing agent for the positive polarity mode was composed of mobile phase A (0.1% FA in water) and mobile phase B (methanol). The developing agent for the negative polarity mode was composed of mobile phase A (5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0) and mobile phase B (methanol). The developing agent gradient was set as follows: 2% B, 1.5 min; 2-100% B, 12.0 min; 100% B, 14.0 min; 100-2% B, 14.1 min; 2% B, 17 min.

2.5. Data Processing and Metabolite Identification

The raw data files from UHPLC-MS/MS were processed by the Compound Discoverer 3.1 (CD3.1, Thermo Fisher) to perform peak alignment, peak picking, and quantitation for each metabolite. Some key parameters were set as follows: retention time tolerance, 0.2 min; actual mass tolerance, 5 ppm; signal intensity tolerance, 30%; signal/noise ratio, 3; and minimum intensity, 100,000. Subsequently, peak intensities were normalized to the total spectral intensity. The normalized data were used to predict the molecular formula based on additive ions, molecular ion peaks, and fragment ions. Then peaks were matched with the (

https://www.mzcloud.org/), mz vault, and mass listed at abase to obtain the accurate qualitative and relative quantitative results. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software R (R version R-3.4.3), Python (Python 2.7.6 version), and CentOS (CentOS release 6.6). When data were not normally distributed, normal transformations were attempted using the area normalization method.

For statistical analysis, PCA, OPLS-DA was applied to analyze the significant metabolites between CB and NS groups using the R package models. Together with Student's t-test (threshold value 0.05), significant-testing among metabolite data was evaluated using the variable importance in projection (VIP) score of the OPLS-DA model. Those with a p value of the t-test <0.05 and VIP ≥ 1 were considered differential metabolites between the two groups. Heat map clustering was drawn using the pheatmaps software package in the R language.

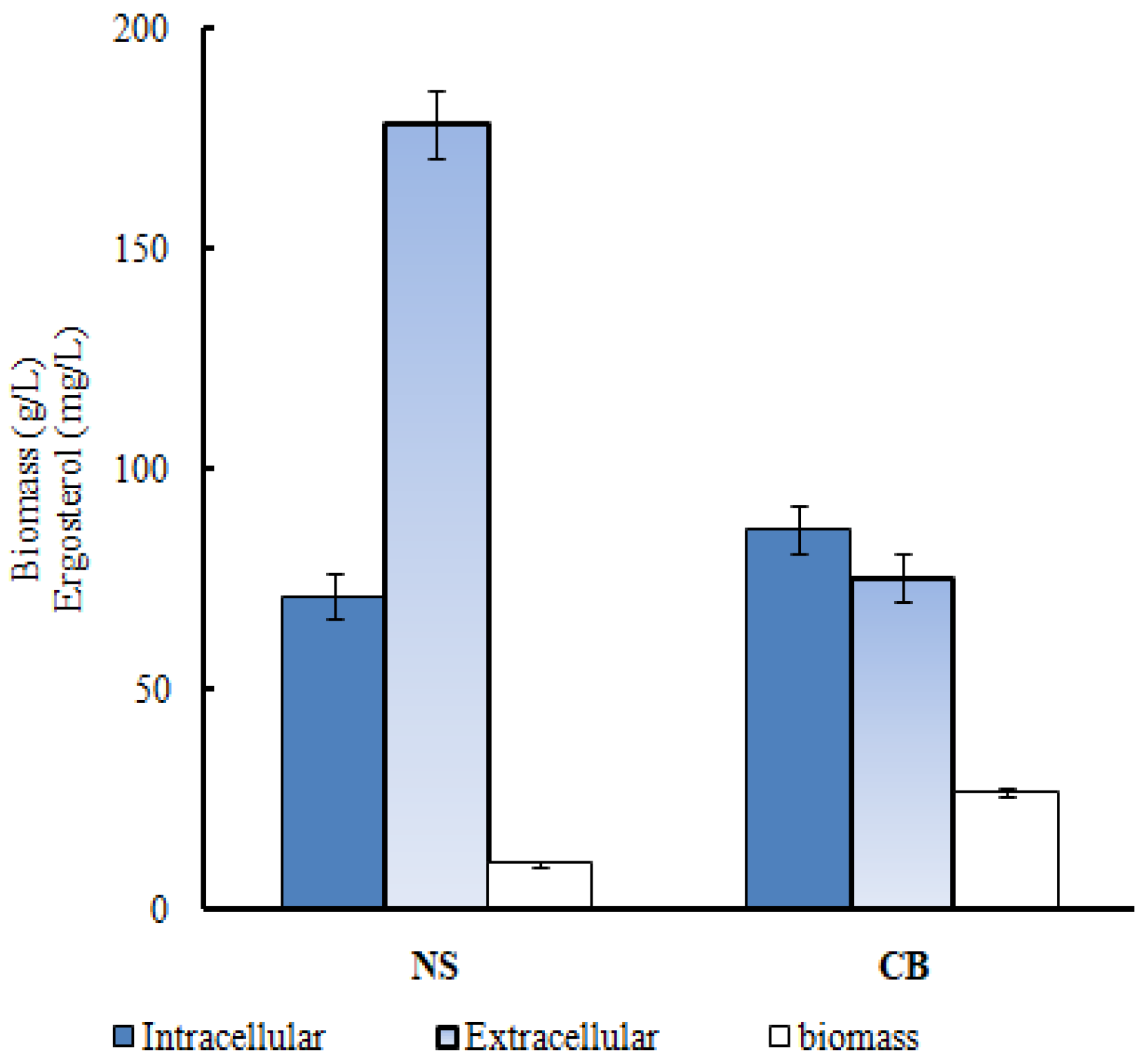

4. Discussion

In the fermentation process, the nitrogen sources must meet the requirement of biomass growth and product synthesis. The effects of different nitrogen sources on biomass and product synthesis depend on the type of nitrogen sources [

35]. Many nitrogen sources are involved in the synthesis of nitrogen-containing metabolites, such as amino-acid, nucleotides, and vitamins. These amino acids and nucleotides are not only the basics of biomass growth but also the precursors of some secondary metabolites [

36]. However, no information on the regulatory action of nitrogen source to ergosterol synthesis of

C.cicadae can be obtained. In the present study, after CO(NH

2)

2 was added, the concentration of intracellular ergosterol was significantly decreased, and the ergosterol content of per unit biomass was further significantly decreased, implying that the content of intracellular ergosterol and its induced inhibitory action were lowered. To disclose the regulatory mechanism of CO(NH

2)

2 on ergosterol synthesis, the UHPLC-MS/MS-based on metabonomic techniques was applied to analyze the

C. cicadae metabolic profile changes on urea response.

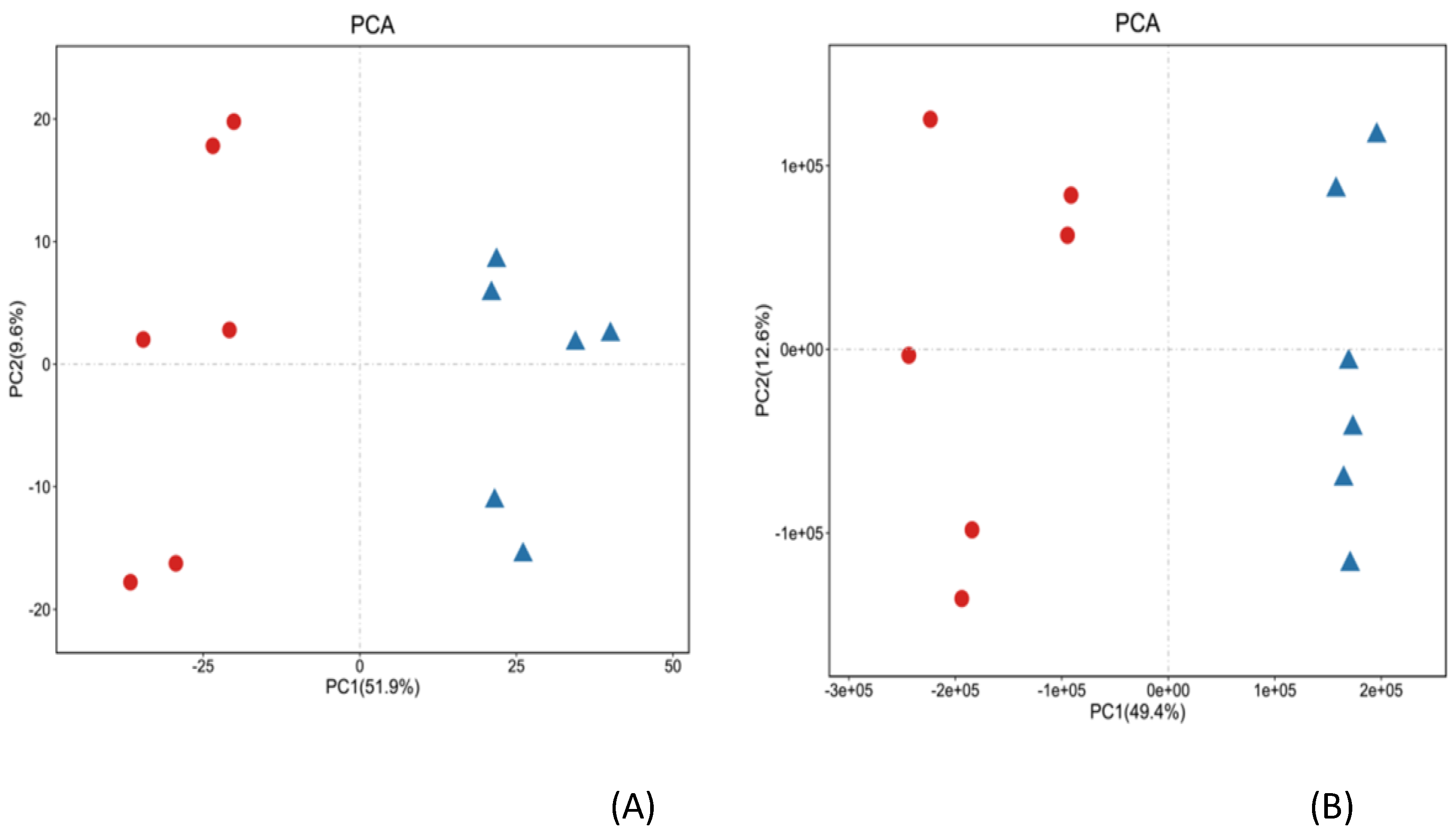

Compounds with the same retention time Rt value and m/z value in different samples were considered to be the same compound. Multivariate statistical analysis was performed to find potential differential biomarkers causing by urea response. In the process of analysis, PCA was first performed on the overall response sample status obtain an overview and classification, and to visualize the clustering trend of the CB and NS groups of samples. Then, OPLS-DA was conducted to obtain the variables with the largest intergroup differences. The S-plot of OPLS-DA visualizes the predictive. The similarity between samples can be determined based on the distance between samples. Where the farther the distance between samples, the larger the VIP value, and the stronger the difference. When the VIP value greater than 1.0, the variable is generally considered a potential biomarker difference between the two samples.

Figure 2 exhibited that the intracellular metabolites without added urea were mainly in the negative axis, and mainly in the positive axis with added urea, according to the first principal component; to the second principal component, the differences were not very significant. According to the first principal component, the CB groups was mainly concentrated in the negative axis, and the NS groups were mainly concentrated in the positive axis. We deduced that urea caused a great difference in metabolites of

C. cicadae.

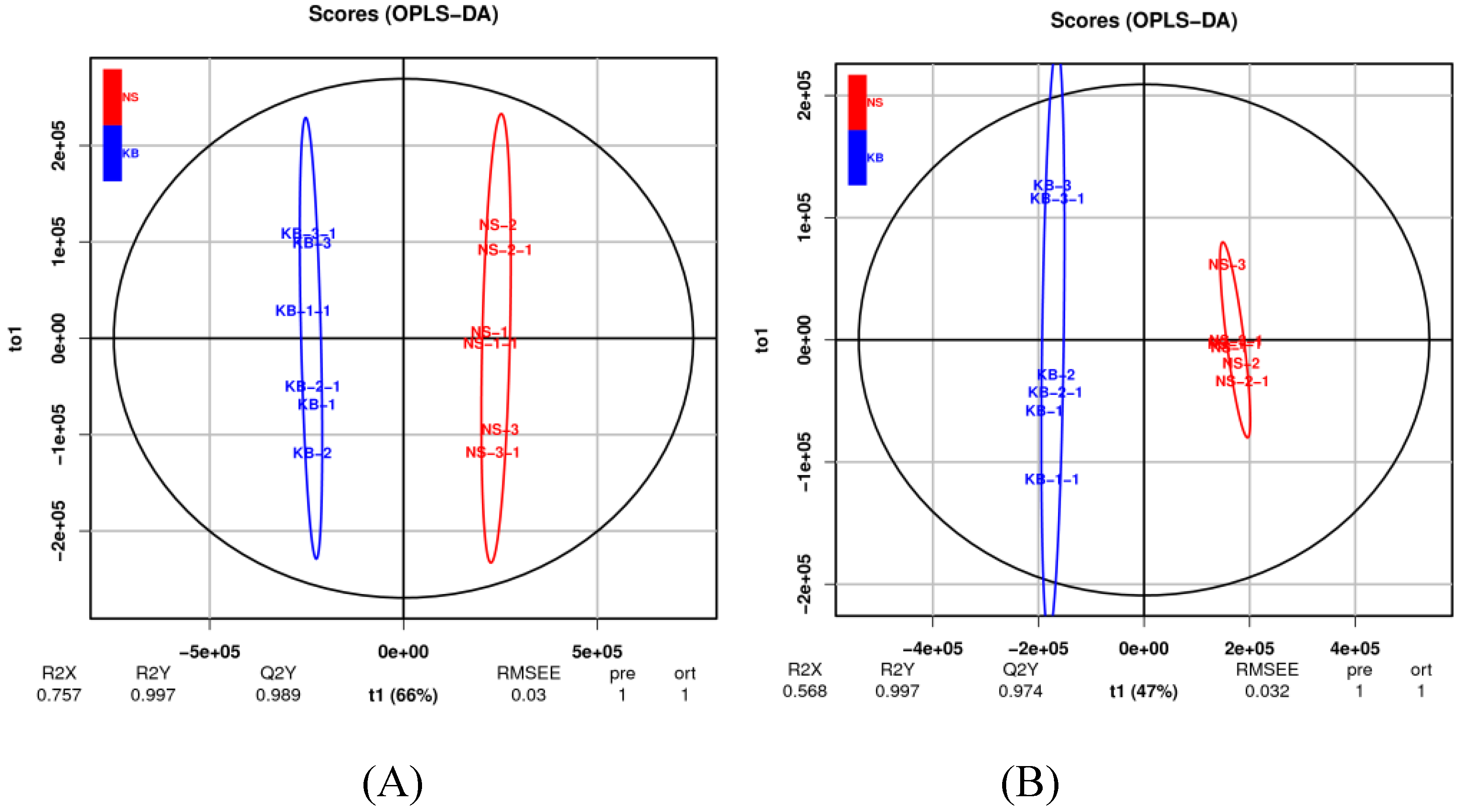

To find out the difference in metabolites caused by urea, the OPLS-DA was used to investigate the difference in metabolites between the CB and NS groups. OPLS-DA was applied in comparison groups using R package models (

http://www.r-project.org/). Although PCA is a reliable grouping method, PCA cannot provide a clear grouping if the intra-group differences in samples are greater compared with the inter-group differences. The OPLS-DA screens differential metabolites and maximizes isolation by removing systemic variants that are not associated with the grouping. After the data are statistically analyzed according to the nature of the group, the key variables that affect the grouping are obtained accurately. Based on the relative content of total ergosterol obtained from NS and CB, the OPLS-DA model was established.

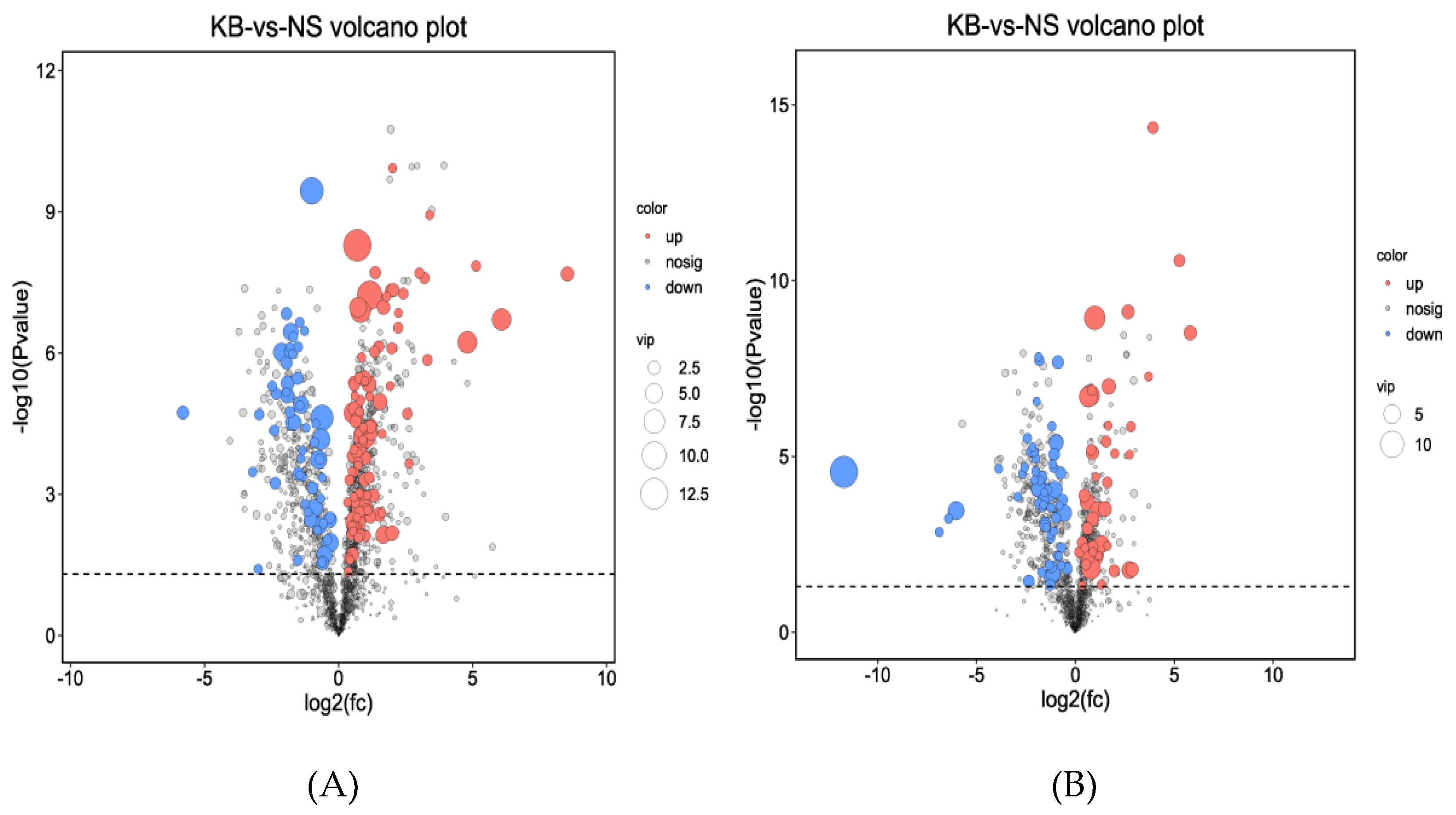

Figure 3A (the cation model) and

Figure 3B (the anion model) show that the OPLS-DA model clearly distinguished metabolites of the CB and NS groups, and the repeated samples were clustered together compactly, indicating the repeatability and reliability of the experiment. R

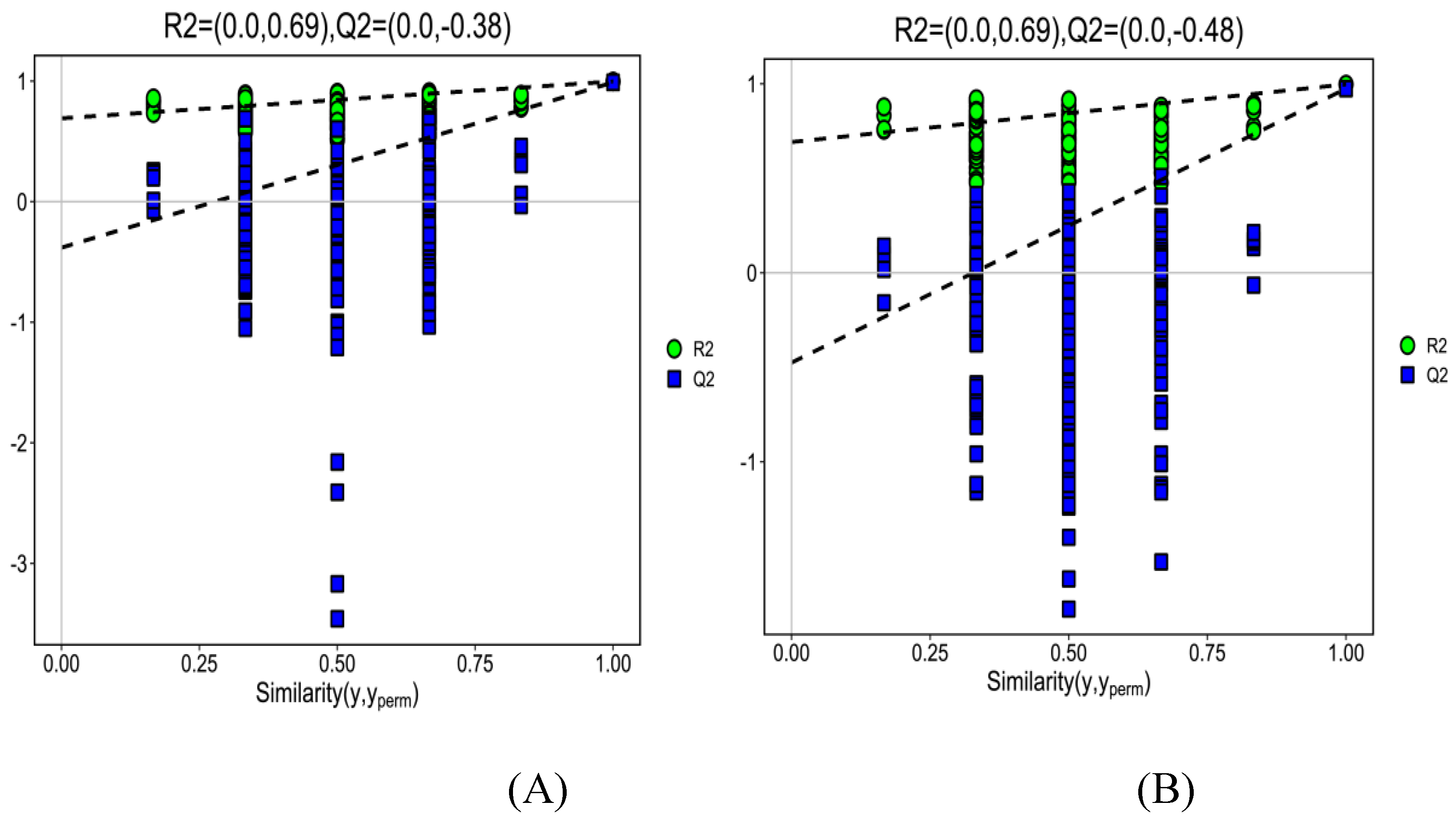

2 indicated the total variation in the data matrix explained by the model. The results were shown in

Figure 4. In the cation/anion model (

Figure 3A or

Figure 3B), Q

2, Rx

2, Ry

2 were all larger than 0.5, showing that the model had a good fit. According to the intercept of Ry

2 larger than the intercept of Q

2 (-0.38 and -0.48 in the cation and anion models, respectively) and the difference between R

2y and Q

2 less than 0.3 in

Figure 4, we inferred that the model had a better interpretation and prediction.

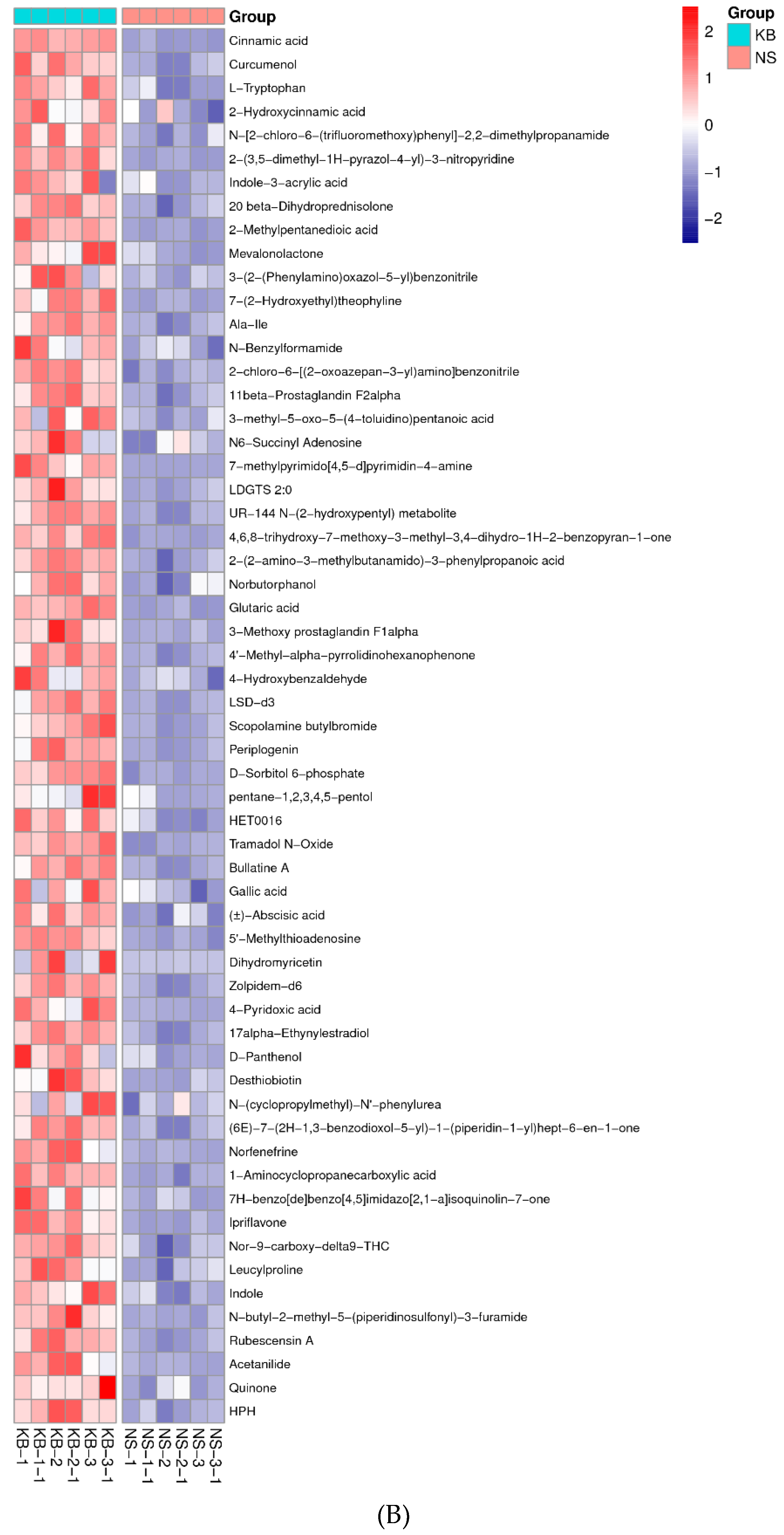

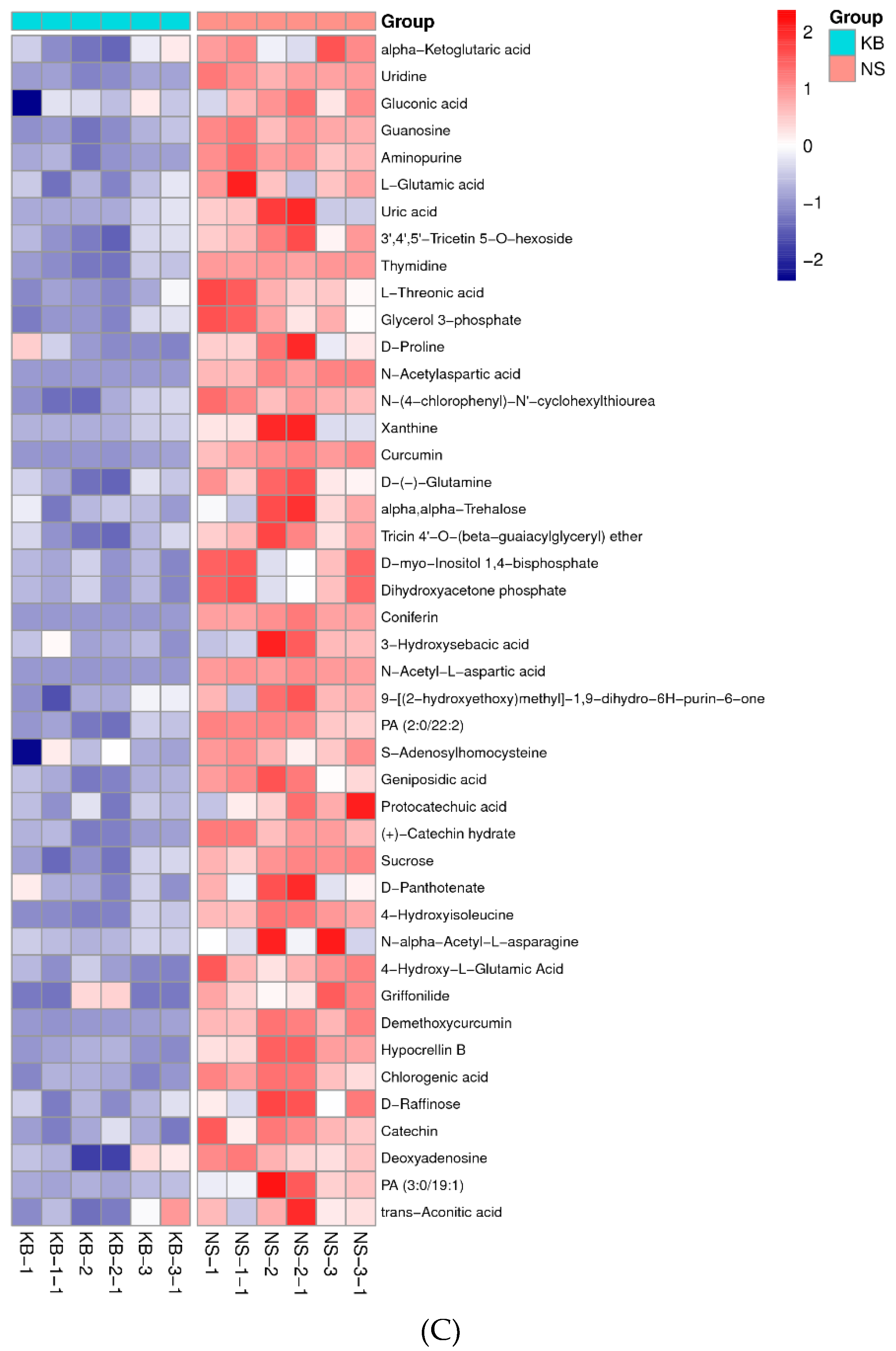

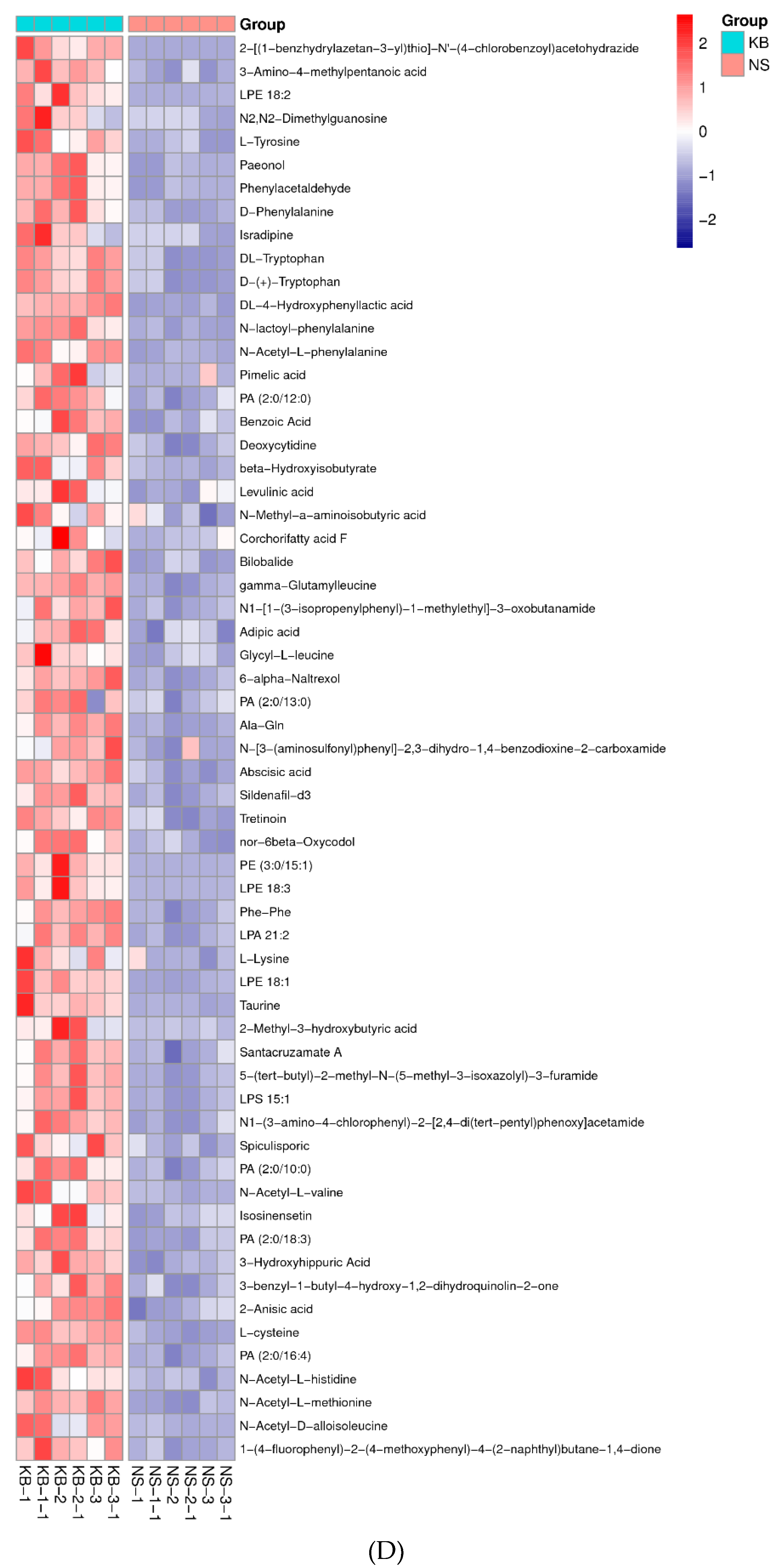

To gain insights into the metabolic mechanism in response to urea and to provide more accurate information of ergosterol synthesis, these changed metabolites obtained from the volcano map were made into a heatmap according to their VIP values (

Figure 6). They could be divided into seven groups as follows: carbohydrate, amino acid, lipid, nucleotides, vitamins, hormones, and other secondary metabolisms.

4.1. Carbohydrate

The proteins, nucleic acids, and fatty acids are the elementary components of the mycelium. The energy (ATP) is the hub in the syntheses of the three above-mentioned components. ATP is derived from the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) pathway. The

Figure 6A showed that the contents of glycerol 3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate were significantly increased after urea was added. According to KEGG metabolic pathway, glycerol can directly access the Embden-Meyerhof pathway and TCA pathway and synthesize NADH and ATP only when they are converted to α-phosphoglycerol and dihydroxyacetone phosphate under the action of glycerol kinase and α-phosphoglycerol dehydrogenase. The increase of glycerol 3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate caused by urea exhibited that the pyruvate for the synthesis of NADH and ATP was significantly increased. The significant increase of the isocitric acid and α-ketoglutaric acid hinted that the activity of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex was weakened in TCA cycle, and the amount of NADH and ATP decreased.

The glycerol 3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate were synthesized to glucose 6-phosphate by gluconeogenesis pathway, and then the glucose 6-phosphate was oxidized by glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase to produce gluconic acid 6-phosphate. Further, gluconic acid 6-phosphate was oxidized by 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase to form ribulose 5-phosphate, which entered into hexose monophosphate shunt (HMP), simultaneously synthesize nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). When the activity of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase was inhibited, the excess gluconic acid 6-phosphate was hydrolyzed into gluconic acid. Thus, the high level of gluconic acid could indicated that 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase in hexose monophosphate shunt (HMP) was inhibited [

37]. 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase is the limiting enzyme, which catalyzed the oxidative dehydrogenation of 6-phospho-D-gluconic acid to NADPH. NADPH is the main hydrogen donor. According to the general theory, if biomass is synthesized in large quantities, HMP is activated, and the NADPH is synthesized in large quantities. In the present study, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase was inhibited, the synthesis of NADPH was decreased, the ergosterol systhesis was decreased.

It has been reported that the main monosaccharides of

C. cicadae polysaccharides are glucose, mannose, and galactose [

38]. The insignificant increase of mannose and galactose in

Figure 6 indicated that there was no increase in the content of the mycelial polysaccharides. Trehalose is a disaccharide compound and exists in many fungi. It is both an energy substance and a signal molecule to adjust metabolic pathways [

39]. Meanwhile, trehalose can protect proteins and cellular membranes from inactivation or denaturation caused by urea. In

Figure 6, the level of trehalose was significantly increased after supplementation of urea, which might be attributed to urea stress.

4.2. Protein and Nucleic acid Metabolism

The premise of biomass growth is the excessive synthesis of proteins, nucleic acids, and fatty acids.

Figure 6 showed that four amino acids, including Pro, Arg, Gln, and Glu, were up-regulated, and five amino acids, including Try, Tyr, Met, Lys, and Cys, were down-regulated. It might be probably attributed to the effect of urea on nitrogen metabolism in vivo. Simultaneously, α-ketoglutaric acid is the presursor of Arg, Gln, and Glu synthesis. The increase of Arg, Gln, and Glu content hinted that the α-ketoglutaric acid dehydrogenase was inhibited. too. Asn is the main nitrogen storage and transport substance in the metabolic process of amide amino acids. Asn was up-regulated under the urea stress in the process of the biomass incubation, which could improve the tolerance of biomass to high concentrations of urea. Meanwhile, the transamination of Asn provided nitrogen sources for the syntheses of nucleic acids and other amino acids. The up-regulation of Asp synthesis was closely related to the up-regulation of Asn synthesis. Although Asp was a synthetic precursor of amino acids, such as Lys, Thr, and Met, as well as purine and pyrimidine bases in the cells. The up-regulation of Asp was helpful for the syntheses of these amino acids, as well as purine and pyrimidine. The higher levels of various free amino acids in the biomass are accompanied by increases in intracellular amino acid levels. Glutathione is a reducing agent and can help the biomass to better grow under oxidative stress [

40]. Up-regulated levels of Glu and Gln are related to glutathione metabolism, thereby improving the oxidative stress tolerance of the yeast. In the present study, on the contrary, because of a long incubation time, the levels of Lys and Met were down-regulated instead of being up-regulated, and the level of L-glutathione oxidized was up-regulated instead of the glutathione. The up-regulated L-glutathione oxidized level exhibited the decrease of the NADH and ATP synthesis.

Nucleic acids are divided into RNA and DNA. Nucleic acids are composed of nitrogen-containing bases (purines and pyrimidines), pentose, and phosphoric acid. In the present study, some bases (adenine, guanine, thymine, uridine, aminopurine, xanthine, deoxyadenosine, and 5-methylcytosine) were up-regulated in response to urea stress. Moreover, 5-methylcytosine is a type of epigenetic modification, and it can be found in a variety of locations. Besides, 5-methylcytosine can protect DNA from its methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes. Excessive synthesis of these bases indicates the enhanced synthesis of DNA and RNA. Deoxyadenosine is a characteristic compound of Cordyceps fungi. Deoxyadenosine can inhibit DNA replication, making it a potential anti-cancer and anti-viral drug.

4.3. Lipid Metabolism

Phospholipid metabolism, a linoleic acid metabolism, is involved in the process of urea response. Choline is the most abundant phospholipid in the cell membrane and an important metabolite of linoleic acid. The abnormal elevation of choline and linoleoyl ethanolamide (

Figure 6) showed that supplementation of urea enhanced the catabolism of linoleic acid. S-adenosylhomocysteine is a by-product of phosphatidylcholine. The increase of S-adenosylhomocysteine level indicated the increase of phosphatidylcholine synthesis. The synthesis level of glycerol 3-phosphate was increased due to the urea supplementation. The phosphatidylcholine and glycerol 3-phosphate were further converted into phospholipid. An increase in both phospholipid anabolism and catabolism suggested that urea supplementation triggered a disturbance in lipid metabolism.

The unsaturated fatty acid is a major component of lipids. Oxygenation of unsaturated fatty acid leads to the production of a large number of structurally similar oxidized fatty acids, collectively known as oxygen lipids. Fungal oxygen lipids are mainly derived from oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid. 9-Oxo-10(E),12(E)- octadecadienoic acid is an oxygen lipid, and its content was markedly increased with the urea supplementation.

After urea was supplied, the concentrations of carnitine, propionyl carnitine, acetyl-L-carnitine, and isocitric acid were increased. Because carnitine is a carrier when acetyl-CoA crosses the mitochondrial membrane [

41], we concluded that the amount of acetyl-CoA, a metabolite of the fatty acid β-oxidation, entering into the TCA cycle was increased. Then acetyl-CoA reacted with amino acids and other compounds to produce large amounts of acetyl-like compounds, such as laevulinic acid and acetyl-aspartic acid. The excess acetyl-CoA also activates gluconeogenesis, and trehalose is produced from pyruvic acid and stored in the mycelium [

42,

43]

Inositol is both a precursor of many chemical compounds and a key membrane structural molecule. It may balance the intracellular environment and protect the cell from cell damage by changing the lipid composition of cells. Inositol 1,4-bisphosphate is the product of the enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol. The addition of urea up-regulated the abundance of inositol 1,4-bisphosphate in C. cicadae, more inositol1,4-bisphosphate indicated that more lipids were hydrolyzed, and cell membrane damage caused by urea stresses was strengthened. The result was consistent with our previous findings 23. In a word, the urea supplementation led to the disorder of lipid metabolism, an increase of cell membrane permeability, and the elevation of ergosterol secretion and extracellular ergosterol concentration.

4.4. Hormones and Vitamins

Hormones are a class of trace organic molecules of living cells that regulate the metabolism or physiological function of target cells. After supplementation of urea, the levels of these hormones were dramatically changed, including metanephrine, normetanephrine, indole, and abscisic acid. One of the most basic functions of abscisic acid is to inhibit the syntheses of DNA and protein. In the present study, the level of abscisic acid was down-regulated, which was consistent with the increased synthesis of nucleic acid and protein described above. We deduced that the significant increase of biomass with added urea was related to the down-regulation of abscisic acid.

As a type of organic substance, the vitamin is necessary to maintain human life activity. It is also an important active substance to keep humans healthy. Vitamins are scarce in the body but essential. In the present study, the levels of many vitamins, including pantothenic acid, panthenol, nicotinamide, pyridoxine, pyridoxic acid, folinic acid, and tretinoin, were increased. Pantothenic acid is VB5. The pantothenic acid helps the energy production in the biomass and can increase the velocity, so that fat and sugar can be converted into energy. The increased pantothenic acid level proved that more fatty acids were oxidized and entered into the TCA cycle to produce energy. The nicotinamide is the precursor of the coenzyme I (dihydrourocil dehydrogense, NAD+) and coenzyme II (nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate, NADP+). NAD+ and NADP+ participate in the energy metabolism of cells and reducing power, respectively. The increased synthesis of NAD + and NADP+ was further proven the decrease of NADH and NADPH synthesis. VB6 is pyridoxine, including pyridoxine, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine. As a water-soluble vitamin, VB6 is closely related to the metabolism of amino acids. The increased concentration of pyridoxine showed the enhanced catabolism of amino acids. Folinic acid is the reduced form of folic acid. When the activity of folate reductase in the organism is reduced, folic acid can not be converted into folinic acid. The folinic acid was the carrier of the one-carbon unit in vivo. The synthesis of many amino acids and nucleotides requires one-carbon units. Therefore, folinic acid was a key marker of nucleotides and amino acids. The increased concentration of folinic acid was directly related to the increased biomass. Tretinoin is an intermediate metabolite of VA. VA is an unsaturated monoalcohol containing an aliphatic ring. VA contributes to cell proliferation and growth. A decrease in tretinoin concentration exhibited an increase in vitamin A concentration, which was consistent with an increase in biomass.

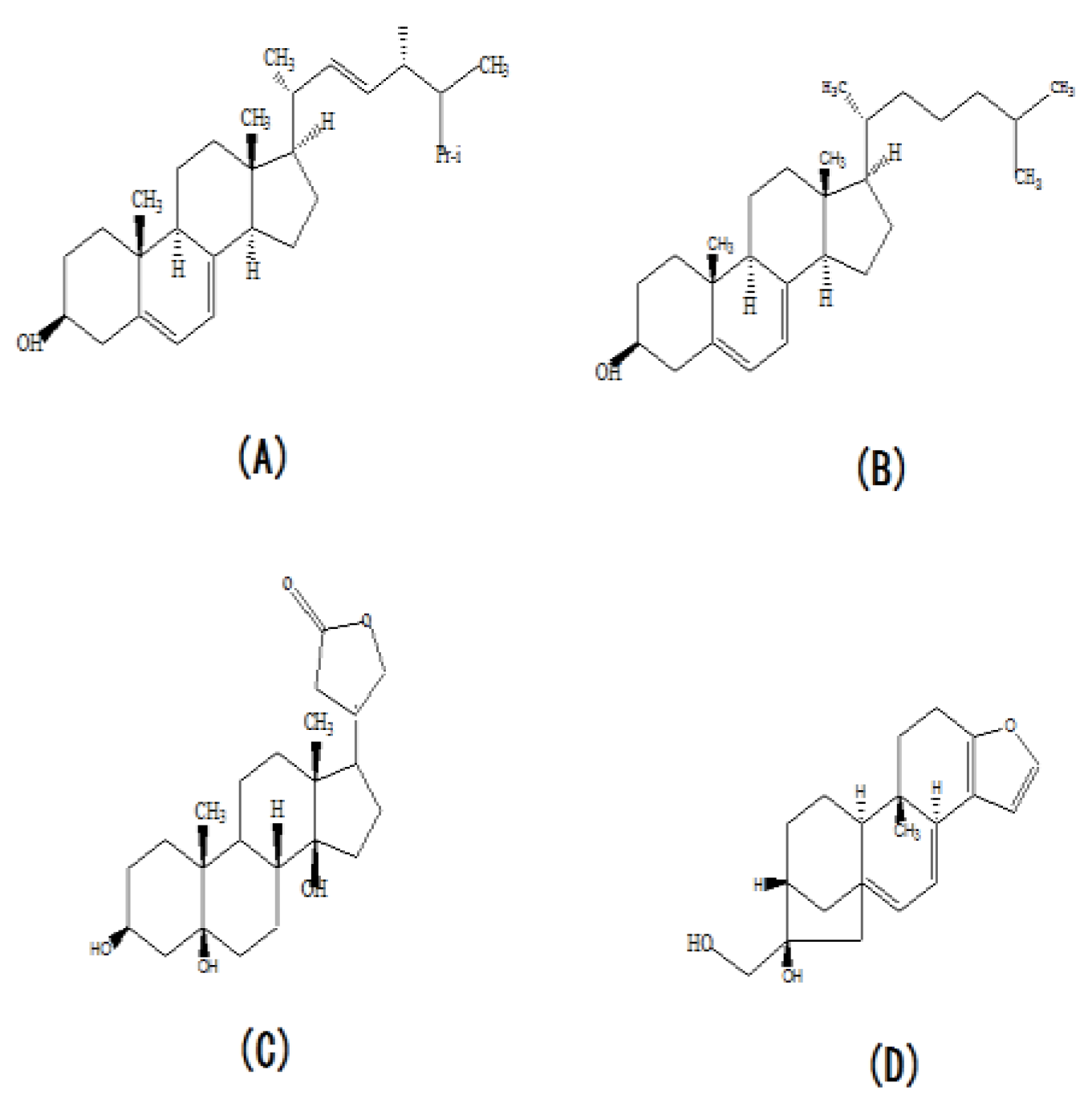

4.5. Sterol

Although we found that the concentration of extra-cellular ergosterol was significantly increased by supplementation of urea, a significant change in the ergosterol concentration was not found in this study. This may be explained by a reduction in ergosterol concentrations below significant levels. However, the periplogenin and cafestol concentration were found to be significant down-regulated and up-regulated, respectively. The periplogenin and cafestol are the other two sterols, whose molecular structure is similar to ergosteril (

Figure 7C). Cafestol has been reported to inhibit the degradation of cholesterol by down-regulation cholesterol 7ɑ-hydroxylase and sterol 27-hydroxylase [

44,

45]. Ergosterol and cholesterol have the same matrix structure, but they have different substitutent group in their matrix structure (Figure7A). Therefore, we hypothesized that cafesterol could inhibit the ergosterol degradation in the process of ergosterol synthesis and made the synthetic ergosterol be secreted extra-cellular. When the concentration of cafestol was up-regulated, the inhibition action of cafestol became the stronger and more ergosterol was secreted to extra-cellular. The structure of periplogenin is similar to the structure of ergosterol and change of its concentration can indicate the trend of intra-cellulare ergosterol concentration. Here, the decrease of periplogenin showed the decrease of intra-cellular ergosterol concentration. In the previous study, we have proven that supplementation of urea increase the synthesis, so we concluded that supplementation of urea made more ergosterol secrete to extra-cellular. In the fermentation anaphasem, the reducing powder (NADPH) and the energy materials (NADH and ATP) synthesis was significantly decreased caused by urea, NADPH, NADH and ATP were involved in many steps of ergosterol synthesis. Thus, we concluded that the inhibition on α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase caused by urea contributed to the decrease the ergosterol synthesis in the fermentation anaphase.

4.6. Other Secondary Metabolites

In the present study, the contents of some secondary metabolites with high biological activity in the fermentation broth of

C. cicadae were significantly changed, including flavonoids, terpenes, saponins, and alkaloids. In the flavonoids, the concentrations of catechin, protocatechuic acid, 3-hydroxy-glabrol, mulberrin, medicarpin, and quercetin were up-regulated. The concentrations of dihydromyricetin and ipriflavone were down-regulated. In the alkaloids, monocrotaline, dictamnine, and trigonelline were up-regulated, while scopolamine butylbromide, bullatine A, and 7-(2-hydroxyethyl) theophylline were down-regulated. In the terpenes, the levels of coniferin, curcumin, lindane, and demethoxycurcumin were up-regulated, and the levels of curcumenol, rubescensin A, bilobalide (BB) and 6-α-naltrexol were down-regulated. BB belongs to a sesquiterpene lactone and is only found in ginkgo leaves [

46,

47]. BB possesses remarkable curative effect on cardiovascular diseases [

48], such as coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia. Notably, BB is frequently used in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer disease [

49] because of an excellent effect on the dullness of old age. To our knowledge, BB is the first to be found in the fungi biomass. Whether there are other ginkgolides in the mycelium of

C. cicadae remains to be studied. Meanwhile, the biomass of

C. cicadae contained so many bioactive materials, suggesting that the biomass of

C. cicada was an excellent source of traditional Chinese medicine and worthy of further development.

In summary, Biomass metabonomic analysis using UPLC-Q-TOF/MS presented a useful tool in identifying physiological changes caused by a component in the medium. Based on our results, we concluded that urea supplementation significantly promoted the growth and ergosterol synthesis of C. cicadae in the liquid incubation process. The promoting effect was confirmed to be related to the increase of membrane integrity and physiological metabolism in C. cicadae and cafestol which inhibited the degradation of ergosterol. More active nitrogen metabolites, such as amino acids, nucleic acids, vitamins, and hormones, and high levels of stress-resistant substances, such as trehalose, disorganized lipid metabolism, and glutathione oxidized associated with urea stress, might be responsible for the increased biomass growth and ergosterol synthesis in the fermentation of C. cicadae. However, in the fermentation anaphase, urea limited the biomass growth and ergosterol by inhibiting activities of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and blocking the NADPH and NADH synthesis. Therefore, the strategy of urea supplementation was expected to be an effective way to improve ergosterol synthesis in the fermentation of C. cicadae.