1. Introduction

Reinforcement learning (RL) has become a powerful tool in developing adaptive control policies for autonomous robots navigating complex environments [

1]. As autonomous systems, particularly mobile robots, are deployed in dynamic and unpredictable real-world settings, robust navigation strategies are crucial. This challenge is especially relevant for skid-steered robots, widely known for their durability and versatility in various robotic applications [

2]. Despite their potential, enabling these robots to navigate efficiently and safely through diverse and unseen environments remains a significant research challenge.

The choice of RL algorithm is critical in developing navigation policies that are both efficient and adaptable [

3]. Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3), introduced by Fujimoto et al. at NeurIPS [

4], is a state-of-the-art RL algorithm designed to address overestimation bias and improve policy stability in continuous control tasks. TD3 improves upon earlier methods, such as Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [

5], through dual critic networks and delayed updates to the policy, which help mitigate overestimation errors and improve the stability of learned policies. Additionally, TD3 leverages a noise signal to promote effective exploration of the action space, preventing premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. Anas et al. [

6,

7] used TD3 to train and test navigation in a 2m x 2m indoor space with 14 obstacles, achieving a 100% success rate in simulation, though they encountered challenges in real-world deployment involving manually controlled obstacles. This work introduced Collision Probability (CP) as a metric for perceived risk, providing an additional layer of risk assessment in navigation tasks.In a different approach, Cimurs et al. [

8,

9] deployed TD3 in environments where obstacles were placed randomly at the start of each episode. By combining global navigation for waypoint selection with local TD3-based navigation, Cimurs et al. achieved effective goal-reaching and obstacle avoidance. Their method demonstrated the strength of integrating global navigation strategies with local reinforcement learning-based navigation, showcasing TD3’s versatility in adapting to diverse and dynamic environments.

Recent Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) methods[

10], such as DreamerV2 [

11], and Multi-view Prompting (MvP) [

12], have demonstrated significant advancements. Methods like TD3, Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) [

13], and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [

14] have gained wide adoption for their compatibility with various data science and machine learning tools. For example, Roth et al. [

15,

16] successfully deployed PPO in real-world scenarios, showcasing its ability to integrate Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, while Akmandor et al. [

17,

18] demonstrated PPO’s effectiveness in progressively more complex dynamic environments. Similarly, my previous work [

19] compared TD3 and SAC, highlighting TD3’s superior consistency and stability in navigating unseen environments. Roth et al. [

15,

16] also used PPO for real-world deployment with the Clearpath Jackal robot in environments similar to those used in simulation, adjusted for real-world conditions. This work uniquely integrated Explainable AI (XAI) techniques by transforming DRL policies into decision trees, enhancing the interpretability and modifiability of navigation decisions, which is especially useful for real-world deployment scenarios. Older techniques, such as DQN [

20], and DDPG, have seen reduced usage due to the superior performance of newer methods like TD3. Empirical results from benchmarks, such as the OpenAI Gym environments, demonstrate that TD3 outperforms several contemporary algorithms, including DDPG, in various control tasks [

1].

Recent works, including those by Xu et al. [

1] and Akmandor et al. [

17], have applied RL algorithms in various environments, demonstrating both their potential and their current limitations. These limitations, along with our approach to address them, are discussed further in

Section 2.

These studies, while advancing DRL-based navigation, exhibit common limitations, particularly in the ability of models to adapt effectively to completely unseen environments. The reliance on fixed start and goal points or controlled environments restricts the robot’s capacity to generalize across different navigation scenarios, which remains a key challenge in RL-based robotics.

The primary contribution of this work lies in extending the TD3 algorithm to improve generalization in robot navigation. Traditional RL-based models tend to excel in environments similar to those used during training but often struggle in unfamiliar settings. To address this, our approach introduces randomized start and goal points during training. By varying these points on each path, the robot is exposed to different navigation scenarios, enabling it to handle unseen environments more effectively. This allows the robot to develop more flexible and adaptive navigation strategies. By enhancing the robot’s ability to navigate in unseen environments, this research aims to bridge the gap between simulation-based training and real-world deployment and overcome the generalization challenges identified in previous studies.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows,

Section 3 provides a background of the TD3 algorithm and key concepts related to its robustness in robot navigation tasks.

Section 2 discusses the research gaps and motivation for extending existing work, particularly focusing on the limitations of current end-to-end deep reinforcement learning (DRL) deployments.

Section 4 outlines the methodology and experimental setup used to assess the extended TD3 model’s performance.

Section 5 outlines the experimental design and the evaluation metrics used to compare the performance of the two TD3 models.

Section 6 presents the training results and comparative analysis of our extended TD3 model with non-extended setups. Finally,

Section 7 evaluates the model’s ability to generalize across unseen environments, and

Section 8 concludes the paper with key findings and recommendations for future work in DRL-based robot navigation.

2. Research Gaps and Motivation for Extending Existing Work

Despite recent advancements in deep reinforcement learning (DRL) for robot navigation, significant challenges remain. Many approaches, though effective in scenarios similar to those used during training or previously encountered, struggle to generalize to diverse and unseen environments. A common issue is the reliance on fixed start and goal points during training, which limits adaptability and reduces the ability to address unexpected scenarios.

Xu et al. [

1,

21,

22] explored this problem by applying TD3, DDPG, and SAC in both static and dynamic environments. Their extensive work involved 300 static environments, each consisting of 4.5m x 4.5m fields with obstacles placed on three edges of a square [

21]. They also tested dynamic-box environments, which featured larger 13.5m x 13.5m fields with randomly moving obstacles of varying shapes, sizes, and velocities. Additionally, Xu et al. evaluated dynamic-wall environments composed of 4.5m x 4.5m fields with parallel walls that moved in opposite directions at various random locations. These scenarios required long-term decision-making to successfully navigate moving obstacles. While they achieved success rates between 60-74%, the highest performance was observed in static environments, and their fixed start and goal configurations hindered adaptability. The strength of their approach lay in the use of distributed training pipelines, which significantly reduced training time by running multiple model instances in parallel, thus optimizing the use of computational resources such as CPUs and GPUs.

Similarly, Akmandor et al. [

17,

18] employed hierarchical training using PPO. They designed a progressive approach from simple to more complex static and dynamic obstacle environments. By integrating heuristic global navigation with PPO-based local navigation, Akmandor et al. demonstrated the robot’s ability to effectively learn strategies such as overtaking oncoming agents and avoiding cross-path agents, which improved success rates in dynamic conditions. However, like other studies, their approach did not fully explore variability in start and goal points, limiting robust generalization.

These limitations are not unique to the works of Xu et al. and Akmandor et al. Many researchers have developed DRL models that excel in training environments but fail to adapt well to unseen settings. Cimurs et al. [

8,

9] achieved impressive simulation results but faced challenges in real-world deployment involving manually controlled obstacles, further highlighting the gap between simulation and practical application.

To address these research gaps, this work extends Xu et al.’s approach by enhancing the exploration capabilities of the TD3 model. The proposed extension introduces randomly generated start and goal points, as mentioned in the

Introduction and described in detail in

Section 4.1,

4.2.2. This randomization allows the robot to experience diverse navigation scenarios during training, significantly improving its adaptability and robustness in unseen environments.

Building on Xu et al.’s distributed rollout framework, this study aims to bridge the gap between simulation-based training and real-world applications by addressing the limitations robots encounter when navigating in environments that differ significantly from their training scenarios. The proposed enhancements focus on improving the robot’s ability to adapt to unseen navigation challenges, ensuring greater generalization and robustness in untested conditions.

3. Background

3.1. TD3 Architecture and Principles

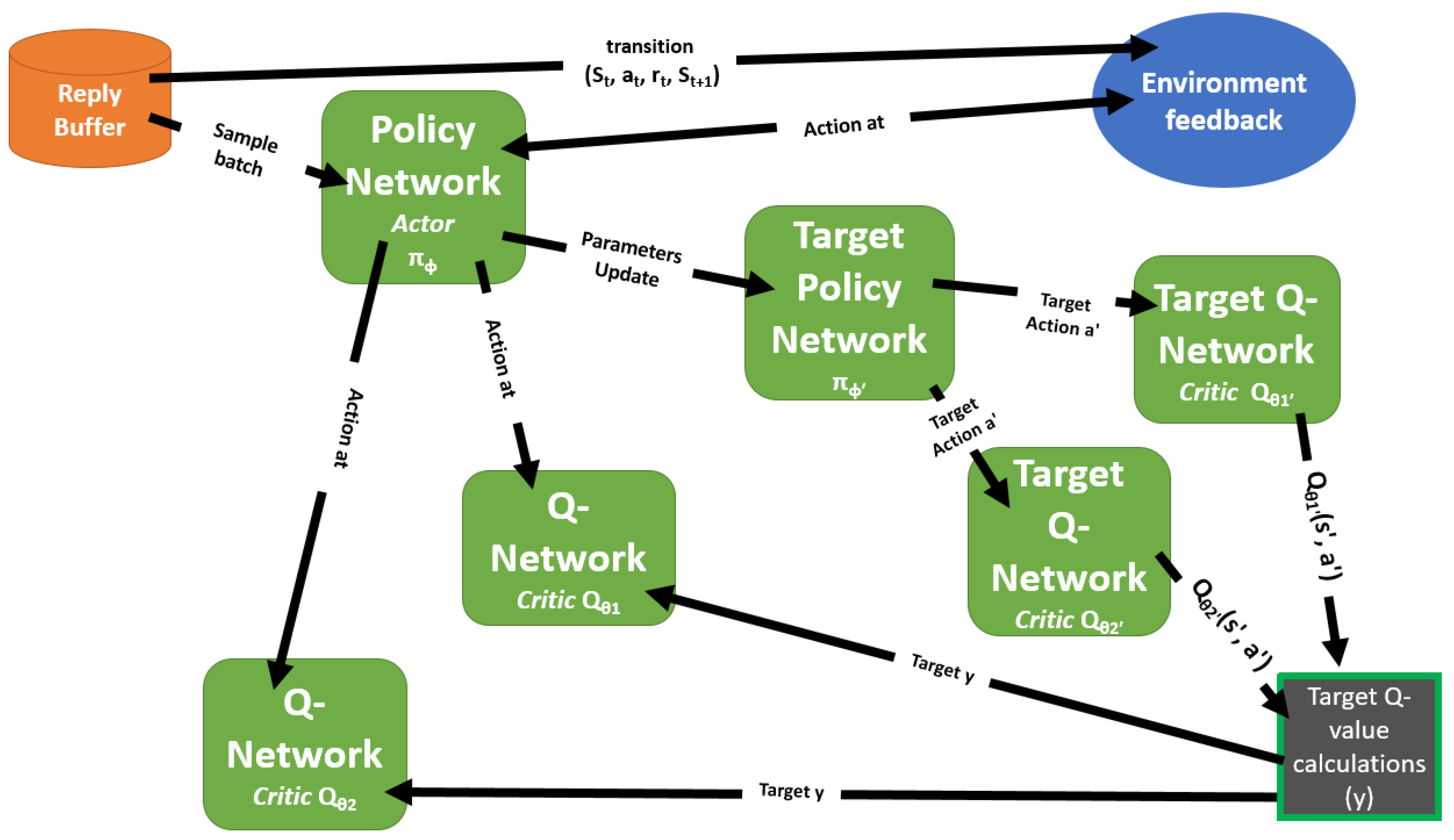

The architecture of TD3 consists of several key components as defined by Scott Fujimoto

et al. [

4]: the actor network, two critic networks, and their corresponding target networks (see

Figure 1). The following is a detailed explanation of each component:

Policy Network (Actor Network): The actor network, denoted as , is responsible for selecting actions given the current state. It approximates the policy function and is parameterized by . The actor network outputs the action that the agent should take in a given state to maximize the expected return.

Critic Networks ( and ): TD3 employs two critic networks, and , to estimate the Q-values for state-action pairs . Each network outputs a scalar value that represents the expected return for a specific state-action pair. The use of two critics helps to reduce overestimation bias, which can occur when function approximation is used in reinforcement learning. By employing double Q-learning, TD3 ensures more accurate value estimates, enhancing the stability of policy updates.

Critic Target Networks: The critic target networks, and , are delayed versions of the primary critic networks and are updated at a slower rate. These target networks provide stable Q-value targets for the critic updates, which helps to reduce variance and prevents divergence during training. By maintaining more conservative Q-value estimates, the critic target networks further mitigate the overestimation bias found in reinforcement learning models.

Actor Target Network: The actor target network, , is a delayed copy of the actor network and is essential for generating stable action targets for the critic updates. The actor target network changes gradually over time, ensuring that the target actions used in critic updates are consistent and stable. This stability is critical for reducing the variance in the Q-value targets provided by the critic target networks, leading to more reliable and stable training of the critics. The actor target network’s slow updates help in maintaining a steady learning process and improve the overall performance of the TD3 algorithm by preventing rapid and unstable policy changes.

3.2. TD3 Networks and Updates

The TD3 algorithm integrates actor and critic networks, each paired with corresponding target networks, to achieve stable and efficient policy updates. The actor network () determines actions that maximize the expected return , and its parameters are updated based on the computed policy gradient. This gradient combines the Q-value gradient () from the primary critic and the policy gradient ().

The critic networks ( and ) evaluate the expected returns for state-action pairs and minimize overestimation bias by employing Clipped Double Q-learning. They calculate a target value , where , and represents added noise for regularization. The critic parameters and are optimized by minimizing the mean squared error between predicted Q-values and y.

To ensure stable training, the target networks (, , ) are updated via a soft update mechanism. Their parameters gradually approach the current networks’ parameters through for the critics and for the actor. This mechanism reduces variance and stabilizes policy updates by ensuring reliable Q-value and action targets during training.

Symbol Definitions

: Actor network responsible for selecting actions.

: Critic networks estimating Q-values for state-action pairs.

, , : Target networks providing stable targets for updates.

: Expected return, optimized by the actor network.

r: Immediate reward received after taking an action.

: Discount factor for future rewards.

: Noise-regularized action used in target Q-value calculation.

: Soft update rate for target network parameters.

: Regularization noise added to target actions.

: Parameters of the primary critic networks.

: Parameters of the actor network.

4. Methodology and Experimental Setup

The research methodology operates within a Singularity container, integrating the Noetic ROS system framework with a simulation of the Jackal robot and a custom OpenAI Gym environment. These components work together with deep reinforcement learning (DRL), initialized using the PyTorch library, to train the robot for navigation tasks.

All simulations are conducted in the Gazebo simulator, specifically within a custom motion control environment, called the MotionControlContinuousLaser environment. This environment is designed for the Jackal robot and provides a continuous action space consisting of linear and angular velocities, enabling smooth robot movement. It also processes the 720-dimensional laser scan data, incorporating it into the observation space, allowing the agent to access essential sensory information for decision-making. By integrating both motion control and laser scan data processing, the environment offers a challenging scenario for evaluating reinforcement learning algorithms in a realistic context.

The training data is collected through interactions in the simulated environments and saved locally. The data is stored in a replay buffer, allowing randomized sampling during the training process. The model’s parameters are updated continuously, and new policies are saved locally until the model converges.

The computational requirements for this training were supported by an AMD Ryzen 9 3900X CPU (12 cores, 24 threads), an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti GPU, and 32 GB of RAM. However, only the CPU was utilized for the training process, while the GPU remained unused. The training relied entirely on the available CPU cores, running six models concurrently within a Singularity container. The training process took approximately five days to complete.

4.1. Jackal Robot Dynamics and Sensors

The Jackal robot is equipped with two primary sensors directly connected to the Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithm and the robot’s control system:

Laser Sensor: The LiDAR sensor provides essential data for navigation by scanning the environment and detecting obstacles. It generates a 720-dimensional laser scan, which is directly used by the DRL algorithm to inform the robot’s decision-making process. This data enables the robot to avoid collisions and select efficient paths to reach its goal. In the Gazebo simulation, the LiDAR sensor replicates real-world sensor dynamics, ensuring that the robot can adapt to complex environments during training.

Velocity Sensor: The velocity sensor monitors the robot’s movement by tracking the linear and angular velocities issued by the DRL node. These commands control the robot’s speed, ensuring that the actual movement matches the intended commands. This feedback helps maintain stable movement and highlights any deviations, such as low velocity, that may affect navigation performance.

4.2. Training and Evaluation Scenarios

The robot was trained and evaluated in static box environments and larger custom environments with randomized start and goal points.

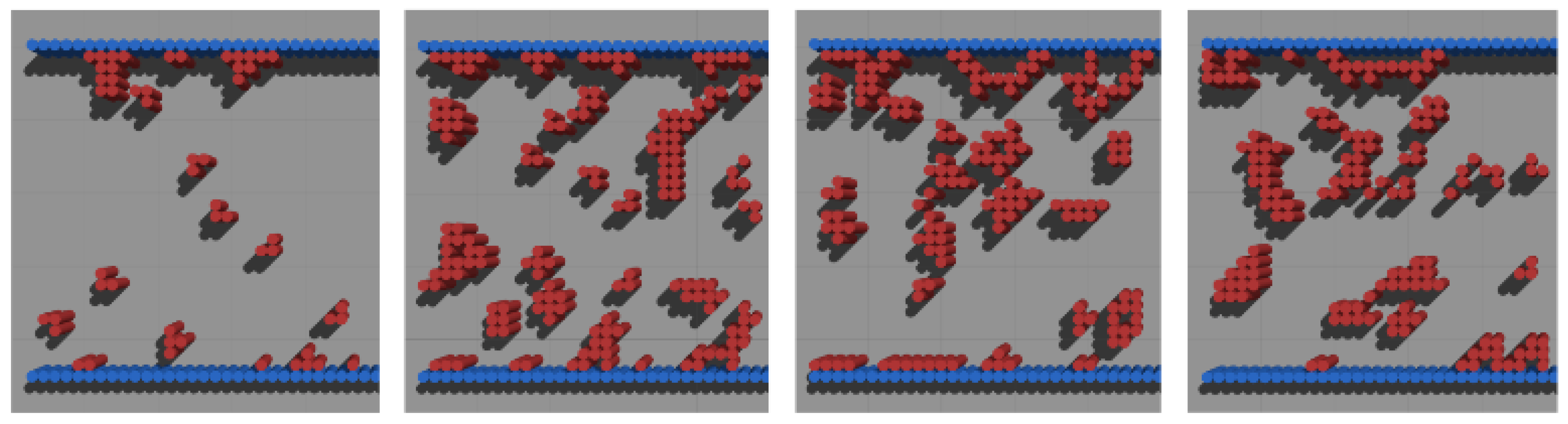

4.2.1. Static Box Environments

In line with previous work [

22], the static box environment measuring 4.5m x 4.5m was used for training. This environment consists of stationary obstacles arranged in various patterns, providing a controlled setting to assess the robot’s navigation performance under static conditions.

Figure 2 shows the layout of the static box environment as originally used in Xu’s study [

21].

4.2.2. Custom Static Environments with Randomized Start and Goal Points

These custom environments consist of 16 unique scenarios, each with distinct designs and varying object positions, creating a diverse range of challenges for the robot. Unlike the original 4.5m x 4.5m static boxes, which limited flexibility due to their small size, these environments are expanded to 16m x 16m, providing wide space for randomization of start and goal points in each episode. This increased area facilitates better exploration and ensures more robust generalization by exposing the robot to a wider variety of paths and obstacles. Each scenario is specifically tailored with unique layouts, different difficulty levels, and diverse obstacle configurations, all designed to enhance the robot’s adaptability, robustness, and overall navigation performance in complex settings.

The navigation scenarios consist of two types of static objects: boxes and cylinders, each with unique dimensions and purposes. Box objects have a fixed dimension of 1m (length) x 1m (width) x 1m (height) and are used as obstacles within the navigation area to add variety to the layouts. Cylinder objects come in five distinct dimensions: Cylinder 1 (radius: 0.14m, height: 1m), Cylinder 2 (radius: 0.22m, height: 1m), Cylinder 3 (radius: 0.30m, height: 2.19m), Cylinder 4 (radius: 0.13m, height: 1m), and Cylinder 5 (radius: 0.30m, height: 2.19m). The border walls of each scenario are constructed using Cylinder 5, which is also utilized as an obstacle inside the navigation area to further diversify the layouts. All objects are static but fully collidable, and any collision with the robot during navigation is registered in the evaluation metrics. The objects are distributed strategically within the 16 scenarios, ensuring a variety of paths, densities, and obstacle arrangements, designed to challenge the robot and enhance its generalization capabilities.

In these environments, the start and goal points are generated randomly and validated based on specific criteria to ensure feasibility. The randomization process ensures that the distance between the start and goal points is at least 8 meters and no more than 11 meters, providing a balanced level of challenge. Additionally, both points are required to maintain a 1.7-meter margin from obstacles to avoid invalid zones, preventing overlaps or unreachable paths. The process uses a random function to generate these points, followed by a validation check. If the points do not meet the criteria, new points are generated until valid positions are found.

The robot’s orientation (phase) is randomized at the beginning of each new path, similar to the randomization of start and goal points. This ensures variability in the robot’s starting direction, enhancing its adaptability and ability to handle diverse scenarios. Randomization is applied at the start of each new path and after failures, ensuring a fresh start with newly randomized parameters.

The same randomization and validation process is applied during testing, ensuring consistency across extended and non-extended models in identical unseen environments.

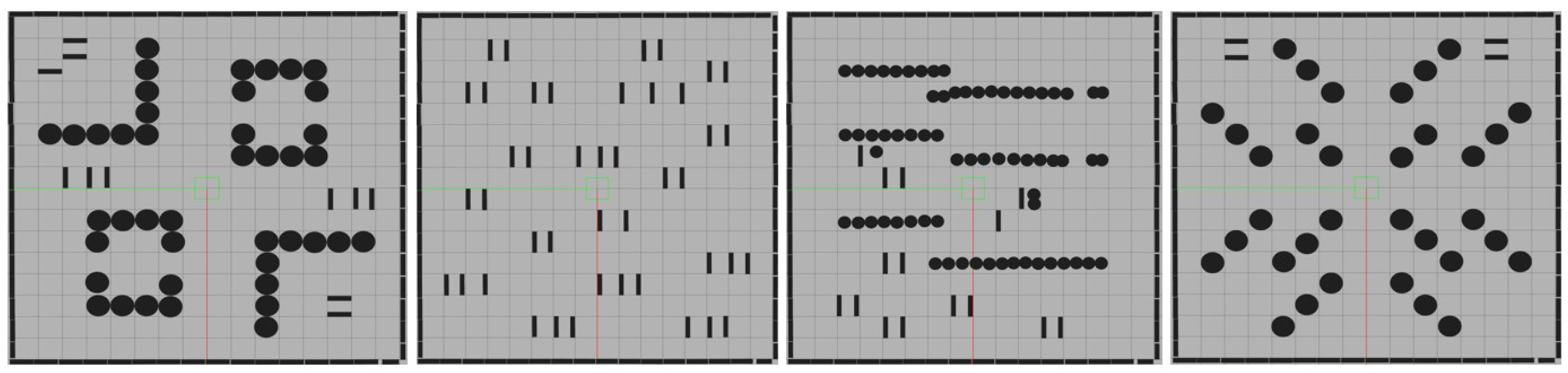

Figure 3 illustrates several examples of these custom environments.

5. Experimental Comparison of TD3 Models

The goal of this experiment is to compare the performance of our improved TD3 model, trained using 16 custom static environments defined in the previous section (

Section 4), with the baseline model trained by Xu et al. [

22] on 300 static environments from the original setup. By contrasting these two models, we aim to determine the impact of environment diversity and training methodology on overall performance.

5.1. Training and Evaluation Metrics

For the evaluation of our improved TD3 model, a comprehensive set of performance metrics will be used to provide a thorough analysis of the model’s behavior in unseen environments. The key metrics include:

Success Rate: The percentage of episodes where the robot successfully reaches the goal without collisions.

Collision Rate: The percentage of episodes where the robot collides with obstacles.

Episode Length: The average duration (in terms of steps) taken by the robot to complete a task.

Average Return: The cumulative reward earned by the robot over an episode, averaged over all episodes, to evaluate the learning efficiency of the algorithm.

Time-Averaged Number of Steps: The average number of steps the robot takes to complete each episode, providing insight into the efficiency of the navigation strategy.

Total Distance Traveled: This metric, calculated during the test phase, measures the total distance (in meters) the robot travels to complete a path. It provides an additional layer of analysis by assessing the efficiency of the robot’s movements in terms of path length.

6. Training Results and Comparison

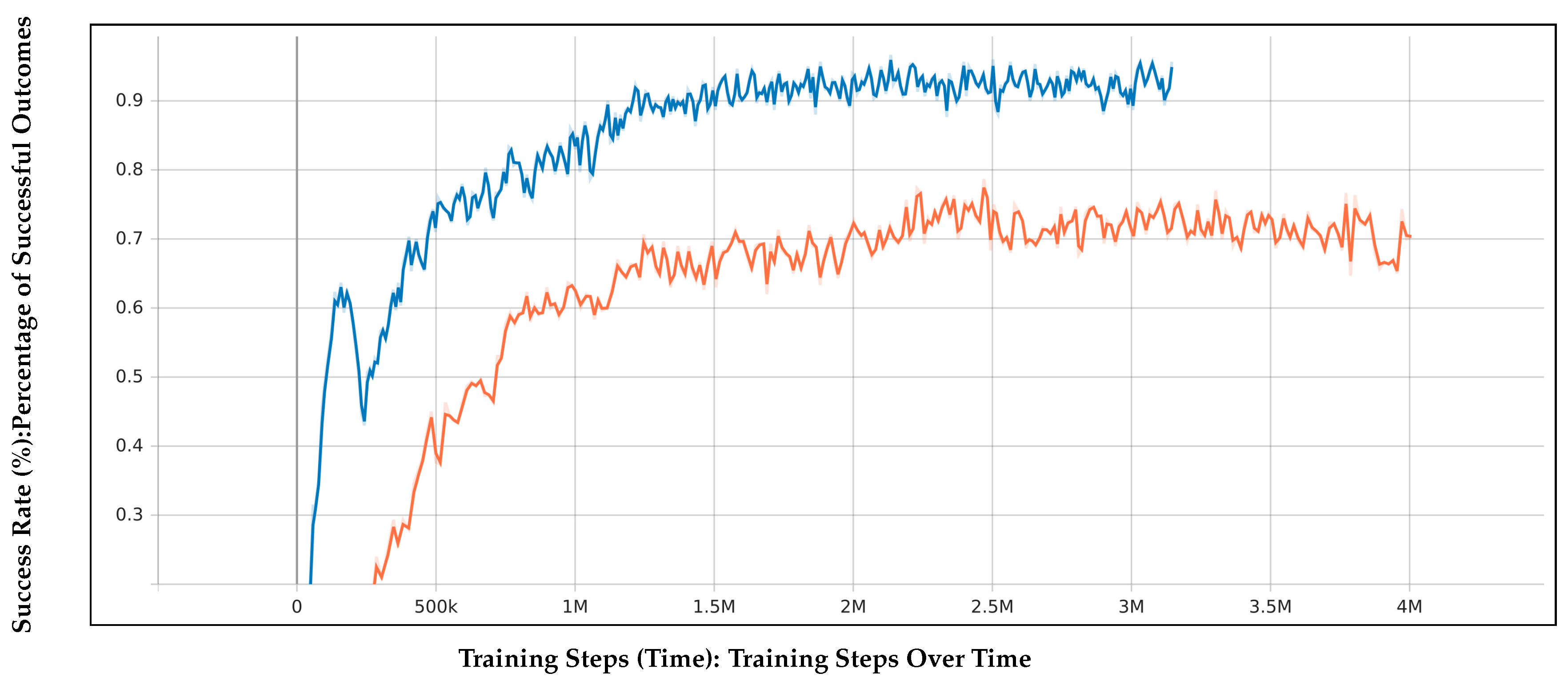

This section compares the performance of the extended model (blue plot) and the non-extended model (orange plot), focusing on success rate, collision rate, and average return.

6.1. Reward Calculation and Success Rate Comparison

At each step within an episode, the reward is calculated using a combination of different factors. The reward at each step is:

Where:

Slack reward: per step.

Progress reward: per meter closer to the goal.

Collision penalty: per collision.

Success reward: for reaching the goal.

Failure penalty: if the episode ends unsuccessfully.

The total reward for one episode is the sum of all step rewards:

The total cumulative reward across multiple episodes is the sum of the cumulative rewards from all episodes currently in the buffer. If you are considering a buffer that holds up to 300 episodes, the total cumulative reward is:

This means each episode contributes its cumulative reward (the sum of its step rewards) to the overall total. When new episodes are added and old ones are removed, the total cumulative reward reflects the most recent set of up to 300 episodes. The rewards ultimately reflect the model’s performance, as higher cumulative rewards align with increased success rates and more efficient navigation.

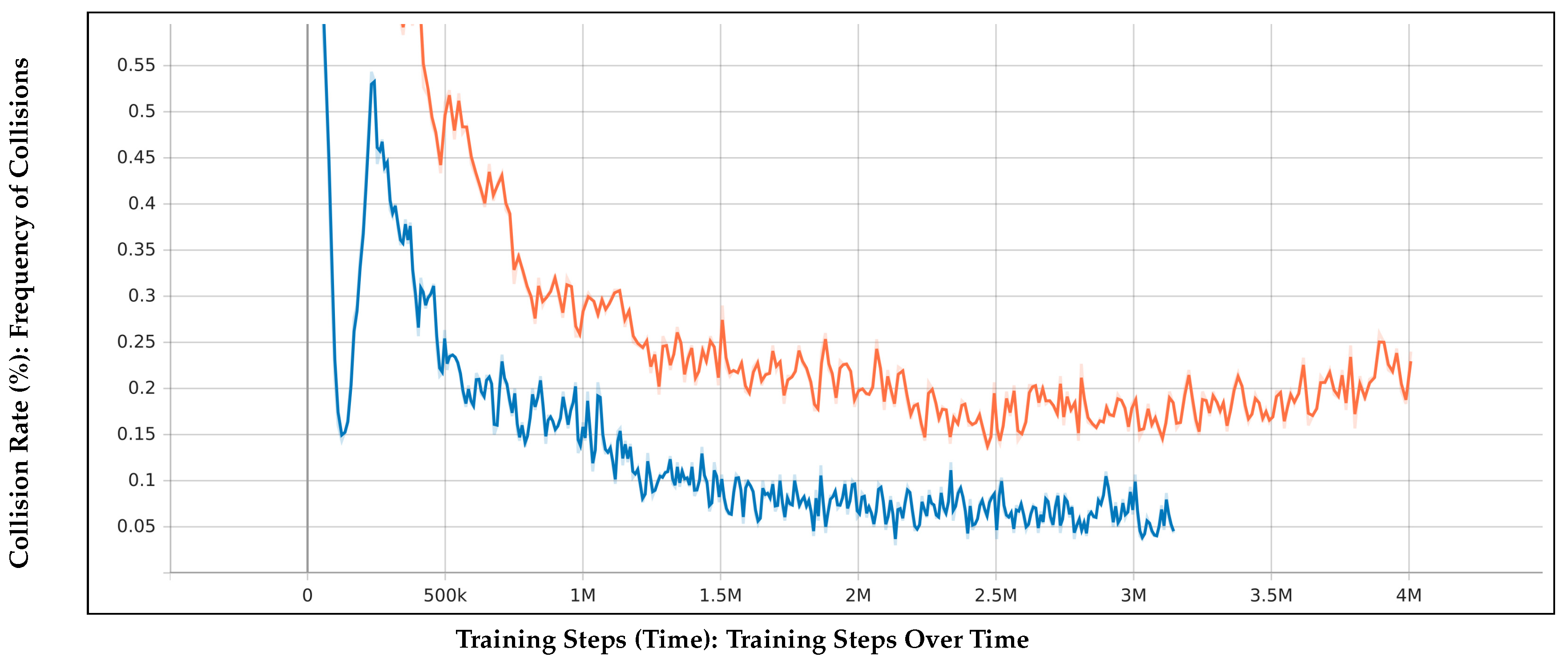

As shown in

Figure 4, the extended model achieved a success rate of 95%, converging before 2 million steps, while the non-extended model reached 70% after 3 million steps. This indicates the extended model’s faster learning speed and higher efficiency due to the randomization of start and goal points.

6.2. Collision Rate Analysis

Figure 5 shows that the extended model had a final collision rate of 4%, compared to 24% for the non-extended model. Both models saw improvements early in training, but the non-extended model’s collision rate increased again after 3.5 million steps, suggesting overtraining. The extended model maintained a more consistent collision reduction.

6.3. Training Efficiency and Convergence

The extended model demonstrated faster convergence and learning efficiency, reaching optimal performance with fewer training steps. The randomization of start and goal points enabled the extended model to explore more diverse environments, resulting in higher success rates. In contrast, the non-extended model, which was trained with fixed start and goal points, showed slower progress and lower success rates. Additionally, some of the environments used by the non-extended model were extremely narrow, which may have limited the robot’s ability to achieve a higher success rate.

7. Transfer to Test Environments Using TD3 and Global Path Planning

To evaluate the generalizability of the extended model, transfer tests were conducted using the Competition Package [

23]. This package, developed by previous researchers and specifically designed for testing, was used in its original form without any modifications or extensions in this study. However, the test environment, Race World [

24], which was not included in the original package, was integrated into it to facilitate evaluation. The Race World environment features a maze-like structure with long walls, creating a challenging scenario for navigation. Both the extended model and the non-extended model were evaluated in this integrated test environment. The contributions of this work are focused entirely on the training phase, where improvements were made to the training setup within a separate package.The Competition Package, enhanced with the integrated Race World environment, served as a reliable benchmark for evaluating the models’ ability to generalize to complex scenarios.

In these tests, the

move_base package [

25] was utilized to provide a global path planning strategy, while the main navigation was handled using the TD3 algorithm. The

move_base package was responsible for generating a global path from the start to the goal, providing a reference path for the robot. The TD3-based controller then followed this global path, adapting locally in real time to avoid obstacles and navigate effectively. This hybrid strategy allowed the robot to utilize the global path for overall guidance while leveraging the adaptability of the TD3-based navigation to handle local challenges.

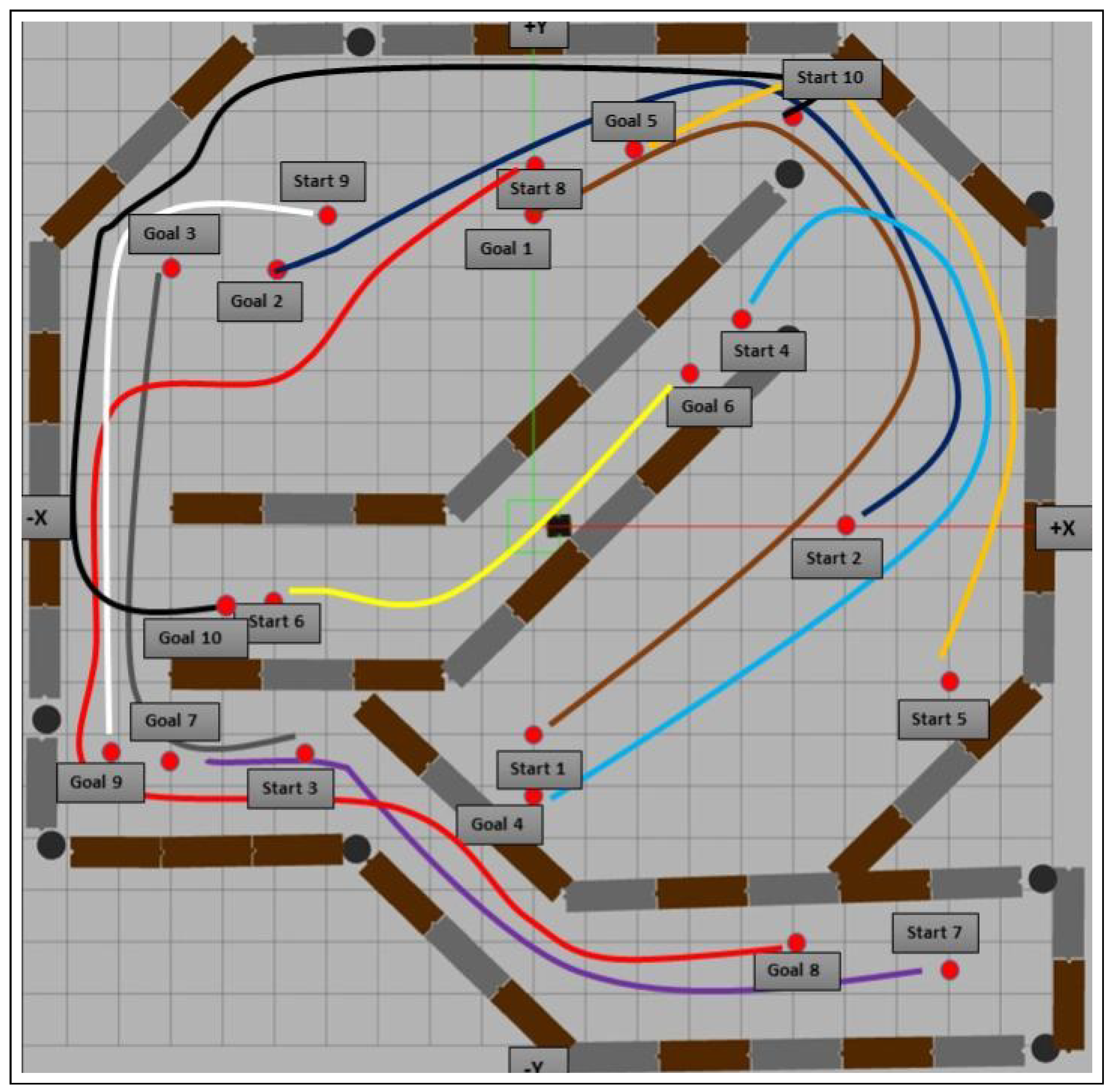

7.1. Evaluation Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the evaluation results for the extended and non-extended models, respectively. These tables provide key metrics, including the total distance traveled, the number of collisions, and the success status for each of the 10 test paths. The test paths used for evaluation are detailed in

Figure 6. The results highlight the superior performance of the extended model, which consistently achieved a higher success rate and fewer collisions compared to the non-extended model. Additionally, the extended model demonstrated more efficient navigation by achieving closer-to-optimal distances on most paths. In contrast, the non-extended model struggled significantly on certain complex paths, often leading to failed navigation attempts or a higher number of collisions.

7.2. Analysis of Results

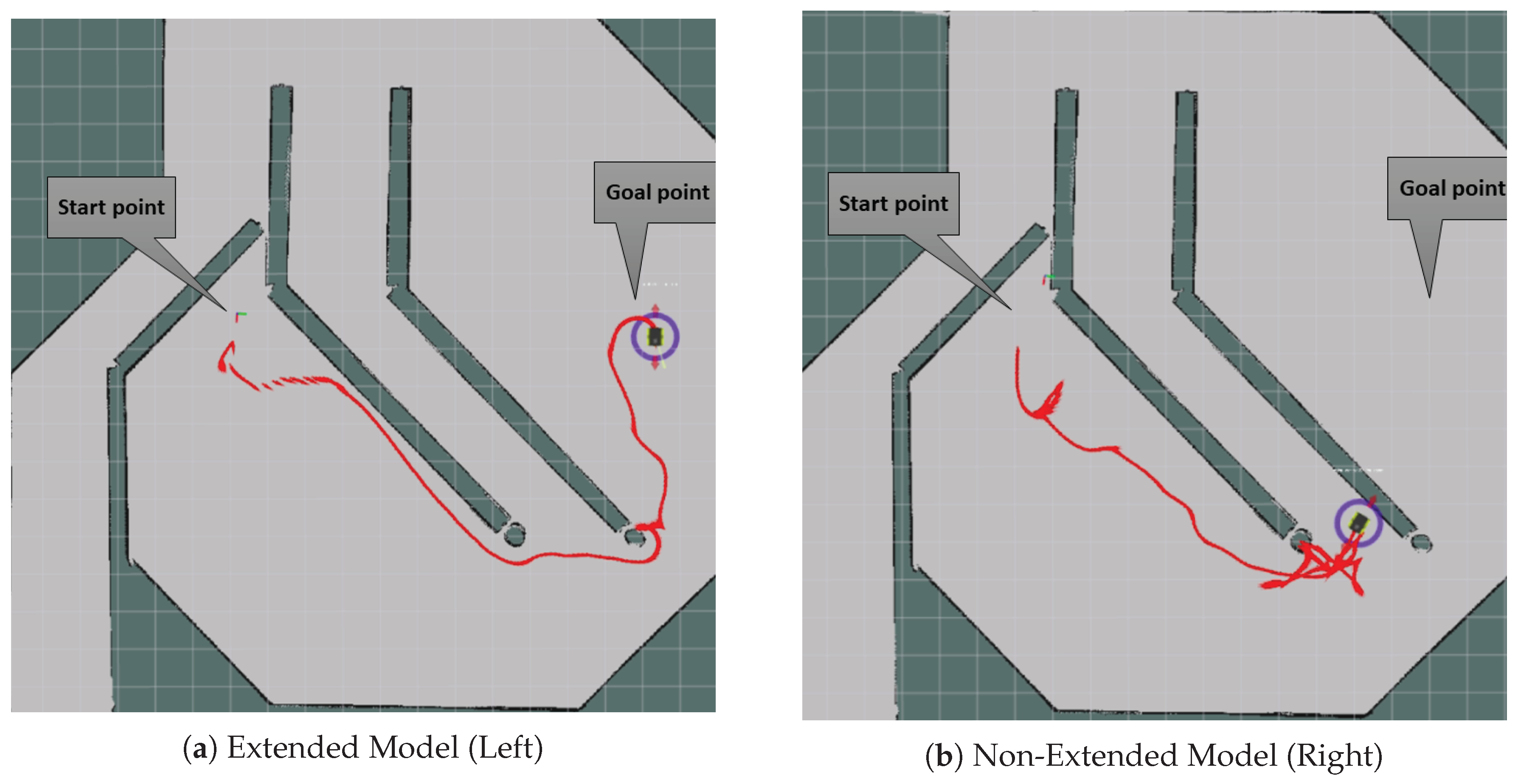

Success Rate and Distance Traveled: The extended model consistently outperformed the non-extended model in terms of success rate and total distance traveled. For instance, in Path 1, the extended model completed the navigation in 18.72 meters with no collisions, achieving a success metric of 100%. In contrast, the non-extended model failed, covering a distance of 33.53 meters with 4 collisions, resulting in a navigation metric of 0%. This highlights the extended model’s ability to stay closer to the optimal path, demonstrating superior generalization and efficient navigation without deviations. The non-extended model, however, faced significant challenges adapting to these scenarios.

Collision Rate and Penalties: The extended model exhibited a considerably lower collision rate across all paths, with either zero or minimal collisions, whereas the non-extended model encountered multiple collisions in most paths. For example, in Path 4, the extended model recorded 4 collisions and failed, achieving a metric of 0%, while the non-extended model also failed with 3 collisions and an even higher distance penalty, resulting in similarly low performance metrics. In contrast, the extended model achieved 100% on paths where collisions were avoided, showing superior collision avoidance and efficient navigation.

Time and Distance Efficiency: The extended model demonstrated better time and distance efficiency in all paths. For instance, in Path 5, the extended model completed the navigation in 9.26 seconds, covering 15.51 meters, while the non-extended model took 42.20 seconds, covering a less optimal path of 32.09 meters. This efficiency showcases the extended model’s ability to make precise navigation decisions in real time, completing tasks faster while adhering closely to the optimal route.

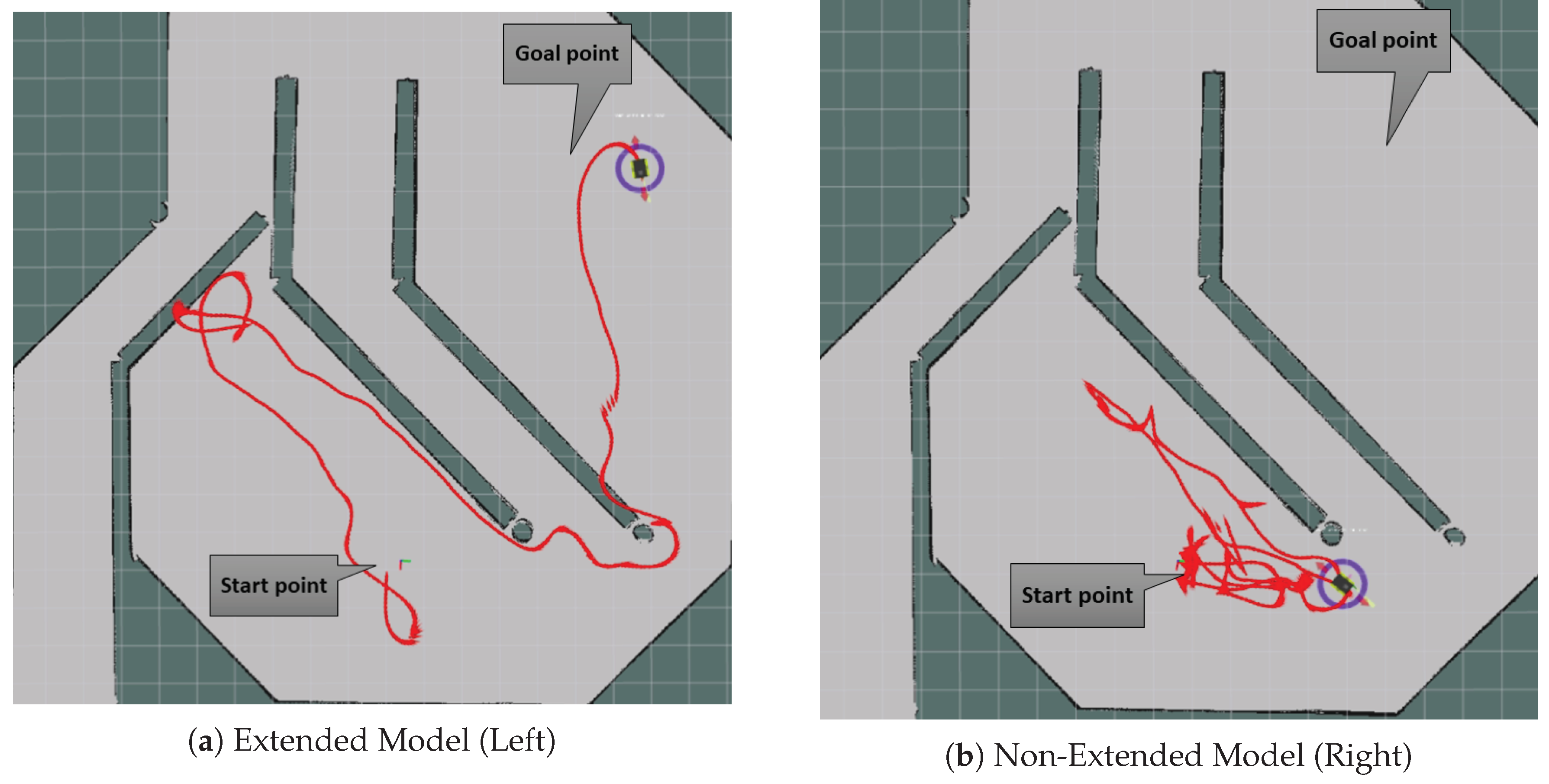

Generalization and Adaptability: The extended model’s superior generalization capability to navigate unseen environments was evident in its successful completion of complex paths with minimal collisions and reduced distances, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. In

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the same paths taken by both models in Path 1 and Path 2 highlight this distinction. The extended model’s trajectory is smooth and efficient, whereas the non-extended model displayed significant deviations and struggled to adapt to the scenario.

Challenges with Non-Straightforward Goals: The non-extended model showed significant difficulty when the goal was not directly aligned with the start point, reflecting a limitation in its ability to navigate complex paths. Trained with fixed start and goal points, the non-extended model primarily learned straightforward navigation, which proved insufficient in the test environments featuring complex turns and long walls (e.g., Paths 2 and 8). In Path 2, for example, the extended model navigated efficiently with a success metric of 57.60%, completing the path without timing out, whereas the non-extended model timed out after traveling an inefficient distance of 41.97 meters.

The extended model’s ability to navigate non-straightforward paths is attributed to its training with randomized start and goal points, which fostered a broader exploration capability and adaptability to unexpected environments, ultimately resulting in higher success rates and reduced penalties during testing.

7.3. Custom Navigation Performance Assessment Score Comparison

Evaluating navigation performance in real-world scenarios requires a metric that accounts for more than binary success or failure. The proposed custom navigation performance score metric better reflects real-world robot behavior by grading performance on a scale from 0% to 100%. This metric evaluates the robot’s efficiency and safety in reaching its goal by considering three key factors: distance traveled, time taken, and the number of collisions. Unlike traditional binary metrics that label navigation attempts as either successful or failed, this score allows for partial successes, acknowledging scenarios where the robot reaches the goal despite minor inefficiencies or collisions. Such graded scoring is critical for realistic evaluations, as in practical applications, minor collisions or suboptimal paths may still be acceptable. By integrating these penalties, the custom metric provides a more nuanced evaluation of robot performance, reflecting real-world decision-making scenarios where navigation is judged not only by reaching the goal but also by the efficiency and safety of the path taken. This approach complements traditional success metrics by offering deeper insights into the robot’s adaptability and robustness. Each test starts with a base score of 100%, with penalties applied based on performance deviations:

where

Each penalty term is defined as follows:

Distance Penalty (

): Applied if the path length exceeds twice the optimal distance. The distance penalty is proportional to the excess distance traveled over twice the optimal distance and is capped at a maximum of 33%. The formula used is:

where max_allowed_distance is four times the optimal distance. If this calculated penalty exceeds 33%, it is capped at 33%.

Time Penalty (

): Applied if the actual navigation time exceeds 40 seconds. This penalty increases with time beyond 40 seconds and is capped at 33%. The calculation is:

If this calculated penalty exceeds 33%, it is capped at 33%.

Collision Penalty (

): Applied based on the number of collisions, with a penalty of 11% per collision. This penalty is capped at a maximum of 3 collisions, leading to a maximum collision penalty of 33%:

If this calculated penalty exceeds 33%, it is capped at 33%.

In this scoring system, a score of 0% is assigned if the robot fails to reach the goal, exceeds four times the optimal distance, or incurs more than 3 collisions.

Table 3 and

Table 4 show that the extended model consistently achieved higher scores, demonstrating more efficient navigation, fewer collisions, and superior adaptability. This is further illustrated in

Figure 7a,b and

Figure 8a,b, which compare the trajectories of the extended and non-extended models for Paths 1 and 2 using RViz visualization. The figures highlight how the extended model navigates more efficiently with fewer collisions and smoother trajectories, while the non-extended model struggles with significant deviations and higher collision rates during navigation.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

Our evaluation of both extended and non-extended environments reveals a significant research gap in robot navigation using deep reinforcement learning (DRL). While models tend to perform well in familiar environments, they often struggle to generalize to unseen environments, highlighting the need to improve the adaptability and robustness of DRL-based navigation systems.

The key insight from this study is that robust generalization is better achieved by training with varied and dynamic start and goal points rather than increasing the number of training scenarios, as done in the non-extended model. This diversity allows the robot to adapt more effectively to unforeseen environments, a perspective not often emphasized in recent studies.

In terms of performance, the non-extended model demonstrates an advantage in navigating extremely narrow environments, likely due to specific training for such conditions. However, it struggles with unpredictable goal points, even in simpler environments. In contrast, the extended model, which emphasizes start and goal diversity, adapts well to unpredictable navigation tasks but may face challenges in extremely narrow environments. This highlights the complementary strengths of both approaches.

To address the concern regarding training time, retraining a pre-trained model instead of training from scratch can significantly reduce the time required to achieve convergence. Additionally, as shown in

Figure 4, the extended model achieved a higher success rate in a shorter time compared to the non-extended model. However, this difference in time efficiency cannot be solely attributed to the superiority of the extended model, as the training environments and setups for the two models were fundamentally different. The non-extended model faced environments with extremely narrow objects, which may have hindered its ability to achieve higher success rates. In contrast, the extended model focused on improving generalization through randomized goal positions, prioritizing adaptability to unseen environments. Future experiments could involve training the extended model in scenarios with extremely narrow objects, similar to those encountered by the non-extended model, to conclusively evaluate its time efficiency under such conditions. However, this may require reducing the variety of randomization to effectively incorporate narrow and extremely narrow objects while maintaining valid zones for random start and goal points.

Regarding real-world applications, this study’s experiments were conducted in a simulated environment using ROS, which provides real-time simulation to closely approximate real-world conditions. However, challenges such as sensor noise, dynamic environment changes, and computing resource constraints must be carefully managed during the deployment phase. While simulation in ROS helps bridge the gap between training and deployment.

We recommend that future work combines the strengths of both models. Training should include diverse start and goal points, as in this extension, while also incorporating narrow and extremely narrow environments to enhance performance in highly constrained spaces. As previously mentioned, Additionally, retraining a pre-trained model can reduce training time, providing a practical approach to address the additional training time that may be needed when integrating these elements.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the SCUDO Office at Politecnico di Torino for their vital support and assistance throughout this research. Special thanks are extended to REPLY Concepts company for their valuable contributions and collaboration. The authors also acknowledge the Department of DAUIN at Politecnico di Torino and the team at PIC4SeR Interdepartmental Centre for Service Robotics -

www.pic4ser.polito.it for their continued support and cooperation. Further appreciation is given to the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department of the University of Coimbra and the Institute for Systems and Robotics (ISR-UC) for their collaboration and assistance. This work was financially supported by the AM2R project, a Mobilizing Agenda for business innovation in the Two Wheels sector, funded by the PRR - Recovery and Resilience Plan and the Next Generation EU Funds under reference C644866475-00000012 | 7253. This paper is the result of a collaborative effort between Politecnico di Torino and the University of Coimbra.

References

- Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Xiao, X.; Nair, A.; Stone, P. Benchmarking Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Autonomous Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023; pp. 9224–9230. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yuxiang, Chirag Rastogi, and William R. Norris. 2021. A CNN Based Vision-Proprioception Fusion Method for Robust UGV Terrain Classification. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 6: 7965–72. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2021.3101866 (accessed on Month Day, Year).

- Sutton, Richard S., and Andrew G. Barto. 2018. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Fujimoto, Scott, Herke van Hoof, and David Meger. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), vol. 80, pp. 1582–91. Stockholm: Stockholmsmässan. 2018. Available online: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/fujimoto18a.html (accessed on Month Day, Year).

- Lillicrap, T. P.; Hunt, J. J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zerosansan. TD3, DDPG, SAC, DQN, Q-Learning, SARSA Mobile Robot Navigation. GitHub repository, 2024. Available online: https://github.com/zerosansan/td3_ddpg_sac_dqn_qlearning_sarsa_mobile_robot_navigation (accessed on September 2024).

- Anas, H.; Hong, O. W.; Malik, O. A. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Mapless Crowd Navigation with Perceived Risk of the Moving Crowd for Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Social Robot Navigation, IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cimurs, R. DRL-robot-navigation. GitHub repository, 2024. Available online: https://github.com/reiniscimurs/DRL-robot-navigation (accessed on September 5, 2024).

- Cimurs, R.; Suh, I. H.; Lee, J. H. Goal-Driven Autonomous Exploration Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 730–737 Available online:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapan, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning Hands-On: Apply Modern RL Methods, with Deep Q-networks, Value Iteration, Policy Gradients, TRPO, AlphaGo Zero and More. Packt Publishing, 2018.

- Hafner, D.; Lillicrap, T. P.; Norouzi, M.; Ba, J. Mastering Atari with Discrete World Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Y.; Yan, S.; Feng, J. Direct Multi-view Multi-person 3D Human Pose Estimation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. CoRR 2018, abs/1801.01290. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.01290.

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. CoRR 2017, abs/1707.06347. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.06347.

- Roth, A. M. JackalCrowdEnv. GitHub repository, 2019. Available online: https://github.com/AMR-/JackalCrowdEnv (accessed on September 5, 2024).

- Roth, A. M.; Liang, J.; Manocha, D. XAI-N: Sensor-based Robot Navigation using Expert Policies and Decision Trees. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akmandor, N. Ü.; Li, H.; Lvov, G.; Dusel, E.; Padir, T. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environments Using Occupancy Values of Motion Primitives. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 2022, pp. 11687–11694. [CrossRef]

- Akmandor, N. U.; Dusel, E. Tentabot: Deep Reinforcement Learning-based Navigation. GitHub repository, 2022. Available online: https://github.com/RIVeR-Lab/tentabot/tree/master (accessed on September 2024).

- Ali, R. Robot exploration and navigation in unseen environments using deep reinforcement learning. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, Open Science Index 213, International Journal of Computer and Systems Engineering 2024, 18, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.5602.

- Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Xiao, X.; Nair, A.; Stone, P. Benchmarking Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Autonomous Navigation. Available online: https://cs.gmu.edu/~xiao/Research/RLNavBenchmark/.

- Daffan, F.; ros_jackal. GitHub repository. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/Daffan/ros_jackal (accessed on September 5, 2024).

- Daffan, F. ROS Jackal: Competition Package. GitHub repository, 2023. Available online: https://github.com/Daffan/ros_jackal/tree/competition (accessed on October 22, 2024).

- Clearpath Robotics. Simulating Jackal in Gazebo. 2024. Available online: https://docs.clearpathrobotics.com/docs/ros1noetic/robots/outdoor_robots/jackal/tutorials_jackal/#simulating-jackal (accessed on October 22, 2024).

- Open Source Robotics Foundation. move_base. ROS Wiki, n.d. Available online: https://wiki.ros.org/move_base.

Figure 1.

TD3 algorithm architecture illustrating the connections between the policy network (actor), the twin critic networks, and the target networks.

Figure 1.

TD3 algorithm architecture illustrating the connections between the policy network (actor), the twin critic networks, and the target networks.

Figure 2.

Original Training Setup: Layout of four different Static Box Environments (4.5m x 4.5m) for training.

Figure 2.

Original Training Setup: Layout of four different Static Box Environments (4.5m x 4.5m) for training.

Figure 3.

Layout of the four different 16m x 16m custom static environments for training.

Figure 3.

Layout of the four different 16m x 16m custom static environments for training.

Figure 4.

Success rate comparison between the extended model (blue) and the non-extended model (orange) across training steps.

Figure 4.

Success rate comparison between the extended model (blue) and the non-extended model (orange) across training steps.

Figure 5.

Collision rate comparison between the extended model (blue) and the non-extended model (orange) across training steps.

Figure 5.

Collision rate comparison between the extended model (blue) and the non-extended model (orange) across training steps.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the 10 start and corresponding goal points used for evaluation in the Gazebo simulation GUI. The paths shown are intended only to indicate the connection between each start and goal point pair for both the extended and non-extended models; they do not represent the actual paths taken by the robot during evaluation, as each model followed a different route based on its learned navigation strategy.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the 10 start and corresponding goal points used for evaluation in the Gazebo simulation GUI. The paths shown are intended only to indicate the connection between each start and goal point pair for both the extended and non-extended models; they do not represent the actual paths taken by the robot during evaluation, as each model followed a different route based on its learned navigation strategy.

Figure 7.

Path taken by both models (Extended on the left, Not Extended on the right) for Path 1, as defined in Tables 1 and 2. The paths shown in both images are in red, illustrating the trajectory of the extended and non-extended models during evaluation. The extended model on the left demonstrates a more efficient navigation, while the non-extended model on the right shows significant deviations and exceeded the maximum allowed collisions without reaching the goal.

Figure 7.

Path taken by both models (Extended on the left, Not Extended on the right) for Path 1, as defined in Tables 1 and 2. The paths shown in both images are in red, illustrating the trajectory of the extended and non-extended models during evaluation. The extended model on the left demonstrates a more efficient navigation, while the non-extended model on the right shows significant deviations and exceeded the maximum allowed collisions without reaching the goal.

Figure 8.

Path taken by both models (Extended on the left, Not Extended on the right) for Path 2, as defined in Tables 1 and 2. The paths shown in both images are in red, illustrating the trajectory of the extended and non-extended models during evaluation. The extended model on the left demonstrates a more efficient navigation, while the non-extended model on the right shows significant deviations and timed out before reaching the goal. Note: The apparent overlap of the robot’s path with the walls in the RViz visualization seen in Figure (a) is a rendering artifact and does not represent any actual collisions during the robot’s navigation.

Figure 8.

Path taken by both models (Extended on the left, Not Extended on the right) for Path 2, as defined in Tables 1 and 2. The paths shown in both images are in red, illustrating the trajectory of the extended and non-extended models during evaluation. The extended model on the left demonstrates a more efficient navigation, while the non-extended model on the right shows significant deviations and timed out before reaching the goal. Note: The apparent overlap of the robot’s path with the walls in the RViz visualization seen in Figure (a) is a rendering artifact and does not represent any actual collisions during the robot’s navigation.

Table 1.

Test Evaluation Results for the Extended Model. Bold values indicate better performance compared to the Non-Extended Model for each metric (Distance, Collisions, Goal Reached, and Time).

Table 1.

Test Evaluation Results for the Extended Model. Bold values indicate better performance compared to the Non-Extended Model for each metric (Distance, Collisions, Goal Reached, and Time).

| Path |

Distance (m) |

Collisions |

Goal Reached |

Time (s) |

| Path 1 |

18.72 |

0 |

Yes |

9.77 |

| Path 2 |

47.16 |

1 |

Yes |

31.66 |

| Path 3 |

13.81 |

0 |

Yes |

8.28 |

| Path 4 |

26.41 |

4 |

No |

21.79 |

| Path 5 |

15.51 |

0 |

Yes |

9.26 |

| Path 6 |

8.12 |

0 |

Yes |

4.19 |

| Path 7 |

15.04 |

3 |

Yes |

9.87 |

| Path 8 |

37.74 |

0 |

No |

35.49 |

| Path 9 |

15.66 |

1 |

Yes |

9.98 |

| Path 10 |

30.54 |

0 |

Yes |

23.33 |

Table 2.

Test Evaluation Results for the Non-Extended Model. Bold values indicate better performance compared to the Extended Model for each metric (Distance, Collisions, Goal Reached, and Time).

Table 2.

Test Evaluation Results for the Non-Extended Model. Bold values indicate better performance compared to the Extended Model for each metric (Distance, Collisions, Goal Reached, and Time).

| Path |

Distance (m) |

Collisions |

Goal Reached |

Time (s) |

| Path 1 |

33.53 |

4 |

No |

33.79 |

| Path 2 |

41.97 |

0 |

No |

80.00 |

| Path 3 |

10.65 |

4 |

No |

14.88 |

| Path 4 |

39.40 |

3 |

No |

67.59 |

| Path 5 |

32.09 |

0 |

Yes |

42.20 |

| Path 6 |

8.12 |

0 |

Yes |

4.24 |

| Path 7 |

15.22 |

3 |

Yes |

9.55 |

| Path 8 |

37.75 |

0 |

No |

39.67 |

| Path 9 |

44.95 |

0 |

No |

56.42 |

| Path 10 |

58.16 |

1 |

No |

68.19 |

Table 3.

Navigation Performance Assessment Metric Scores for the Extended Model.

Table 3.

Navigation Performance Assessment Metric Scores for the Extended Model.

| Path |

Metric (%) |

Description |

| Path 1 |

100.00 |

No collisions, within max allowed distance |

| Path 2 |

57.60 |

1 collision, exceeded optimal distance with penalty |

| Path 3 |

100.00 |

No collisions, optimal path followed |

| Path 4 |

0.00 |

4 collisions, exceeded max allowed distance |

| Path 5 |

100.00 |

No collisions, within optimal range |

| Path 6 |

100.00 |

No collisions, optimal path |

| Path 7 |

67.00 |

3 collisions, distance exceeded slightly |

| Path 8 |

0.00 |

Exceeded max allowed distance |

| Path 9 |

70.00 |

1 collision, slight penalty |

| Path 10 |

98.33 |

No collisions, distance exceeded slightly |

Table 4.

Navigation Performance Assessment Metric Scores for the Non-Extended Model.

Table 4.

Navigation Performance Assessment Metric Scores for the Non-Extended Model.

| Path |

Metric (%) |

Description |

| Path 1 |

0.00 |

4 collisions, exceeded max allowed distance |

| Path 2 |

0.00 |

Timeout, exceeded max distance |

| Path 3 |

0.00 |

4 collisions, failed navigation |

| Path 4 |

0.00 |

Exceeded max allowed distance with 3 collisions |

| Path 5 |

85.77 |

No collisions, slight distance and time penalties |

| Path 6 |

100.00 |

No collisions, optimal path followed |

| Path 7 |

10.00 |

3 collisions, slight penalty |

| Path 8 |

0.00 |

Exceeded max allowed distance |

| Path 9 |

0.00 |

Exceeded max allowed distance, timeout |

| Path 10 |

0.00 |

Exceeded max allowed distance with 1 collision |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).