Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A navigation framework based on single-agent deep reinforcement learning, which allows the ego robot to move according to social norms among humans and other robots that follow a predefined collision avoidance behaviour.

- The use of imitation learning for socially aware single agent navigation in environments shared other robots and humans.

- A model of the full social awareness for the ego robot and partial social awareness for other robots to reflect realistic interactions, enabling the extraction of socially relevant knowledge from human-robot interactions.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Assumptions

- This work is based on a Single agent deep reinforcement learning framework where an agent learns in an environment that includes other robots and humans as part of the environment.

- The robot that learns the optimal policy is called the ego robot while the other robots in the environment are referred to as the other robots.

- The ego robot has a full view of the environment while the other robots have a partial view of the environment.

- All the robots are modeled as holonomic, i.e. they can move in any direction instantly without rotation constraints.

- Humans and other robots in the environment follow the ORCA policy.

- There is no explicit communication of navigation intent between ego robot, other robots and humans, they can only observe the states of each other.

- The navigation is modeled as point-to-point navigation scenarios in Two-Dimensional (2D) plane.

3.2. Problem Formulation

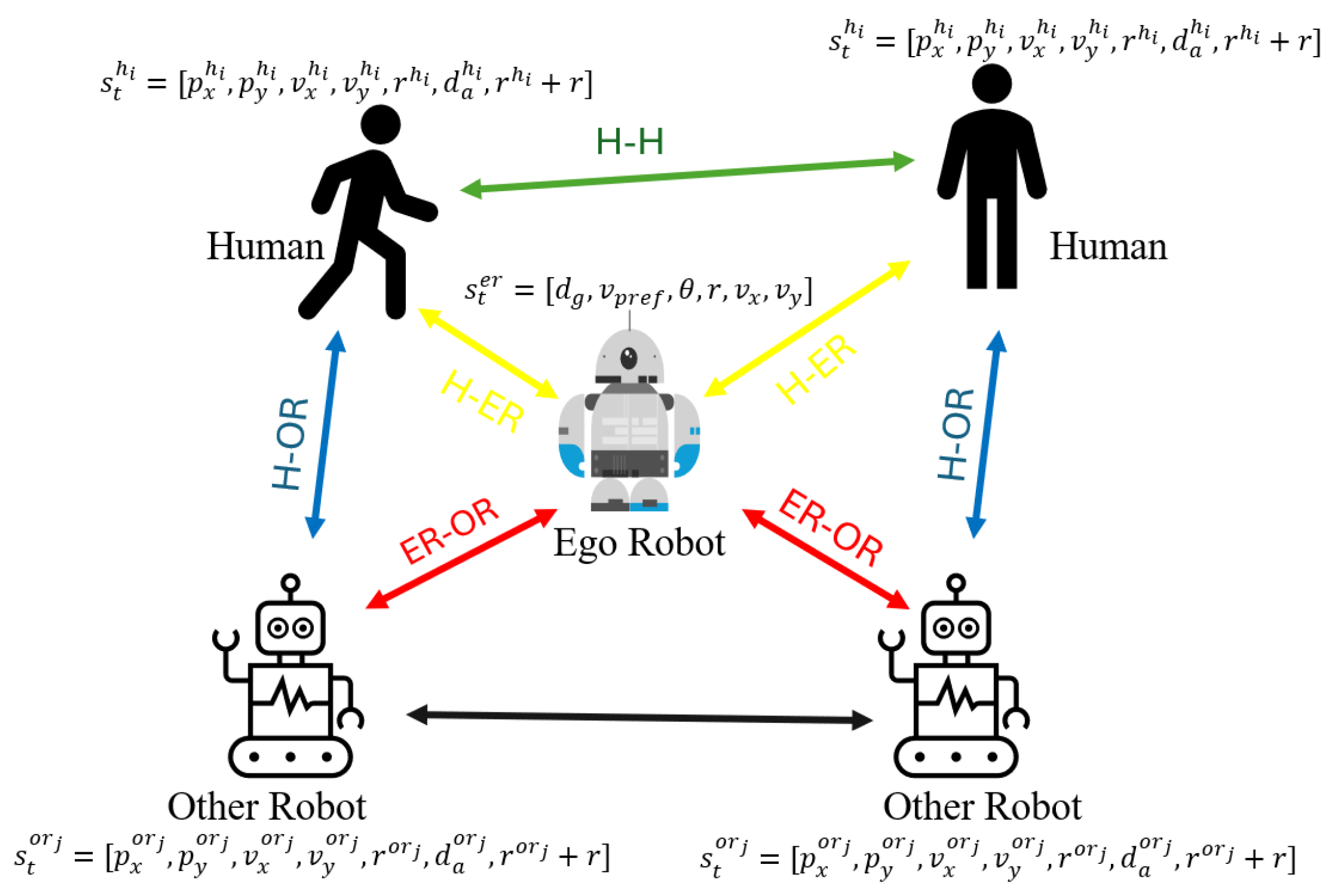

3.2.1. State Space

3.2.2. Action Space

3.2.3. Reward Function

3.2.4. Optimal Policy and Value Function

3.3. Interaction Modeling

3.3.1. Human-Human Interaction

3.3.2. Human-Ego Robot Interaction

3.3.3. Ego Robot-Other robot Interaction

3.3.4. Human-Other Robot Interaction

3.3.5. Other Robot-Other Robot Interaction

| Agent | In presence of Human | In presence of Ego Robot | In presence of other robot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Reciprocal collision avoidance | Reciprocal collision avoidance | Reciprocal collision avoidance |

| Ego Robot | Implements learned DRL policy with social awareness | - | Reciprocal collision avoidance (no social awareness) |

| Other Robot | Reciprocal collision avoidance with larger safety margin | Reciprocal collision avoidance (no social awareness) | Reciprocal collision avoidance |

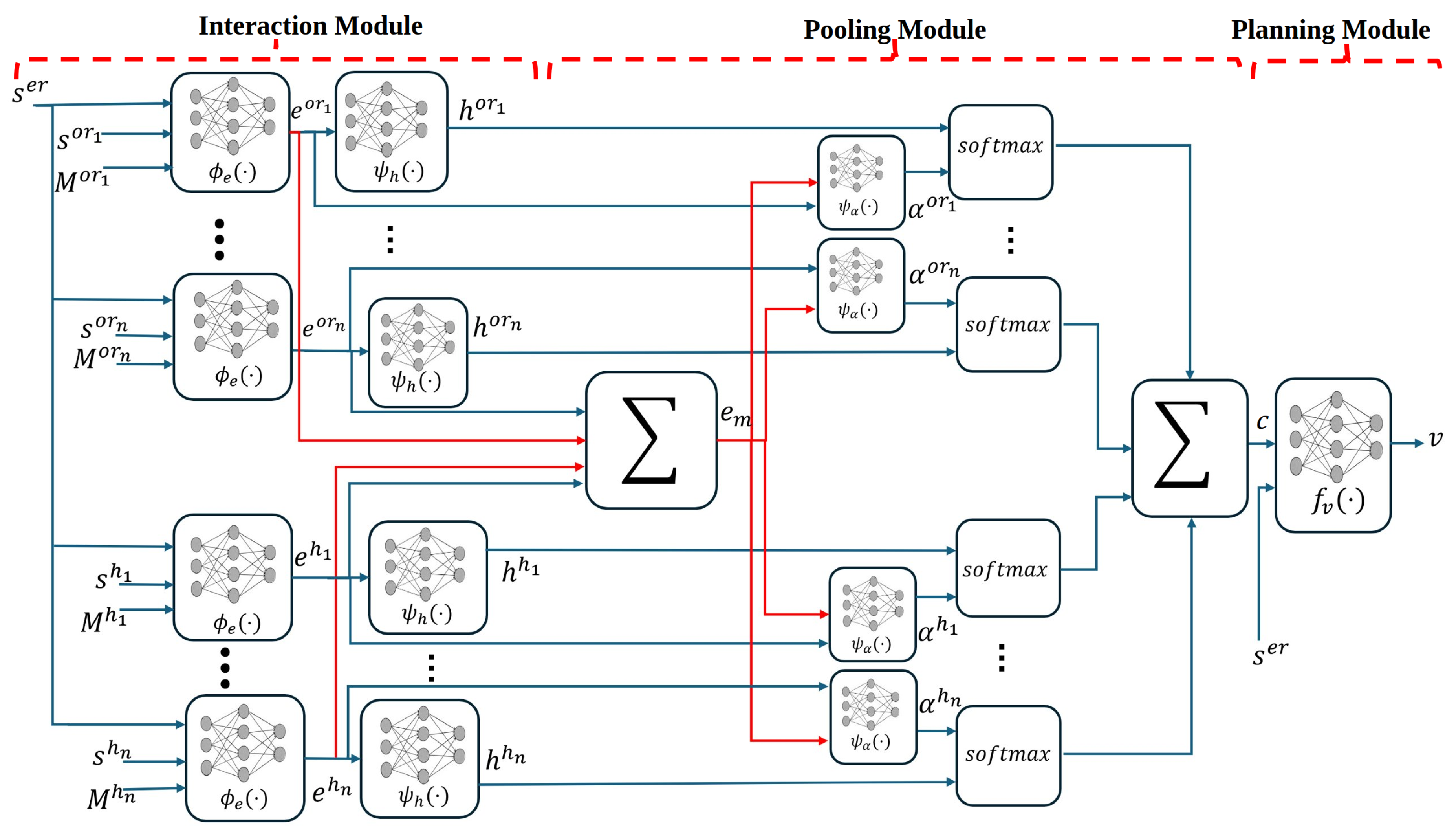

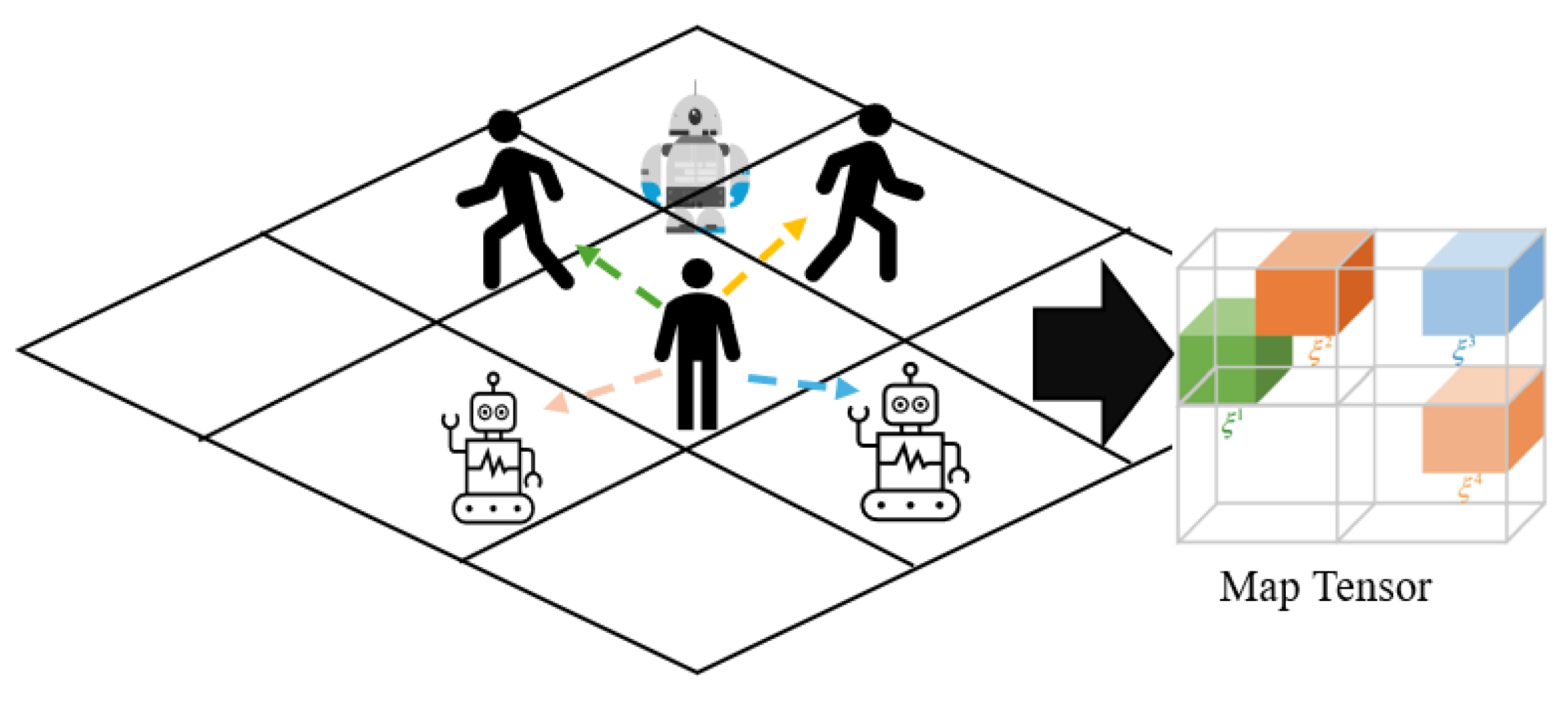

3.4. System Architecture

3.4.1. Interaction Module

3.4.2. Pooling Module

3.4.3. Planning Module

4. Results

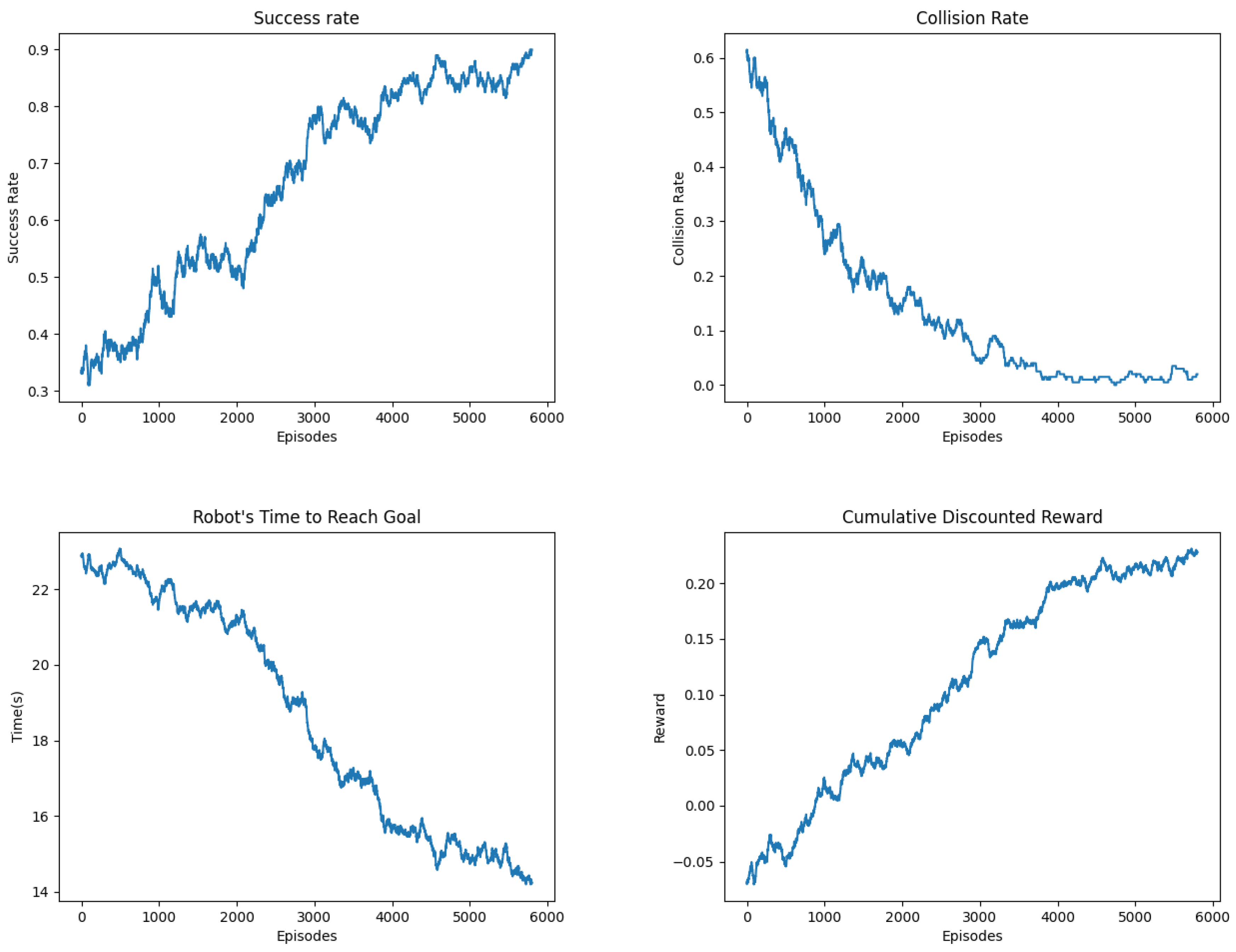

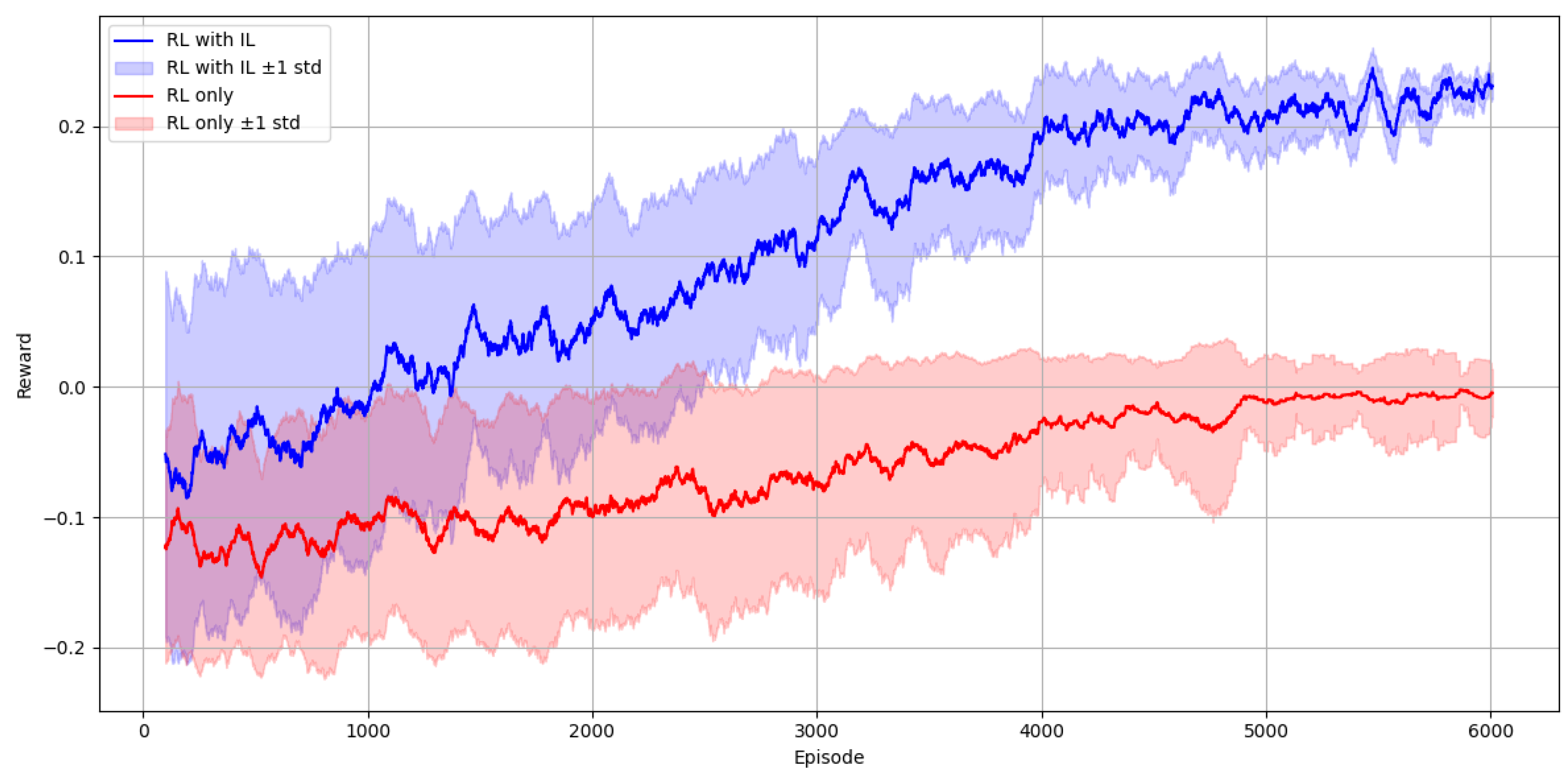

4.1. Training Setup

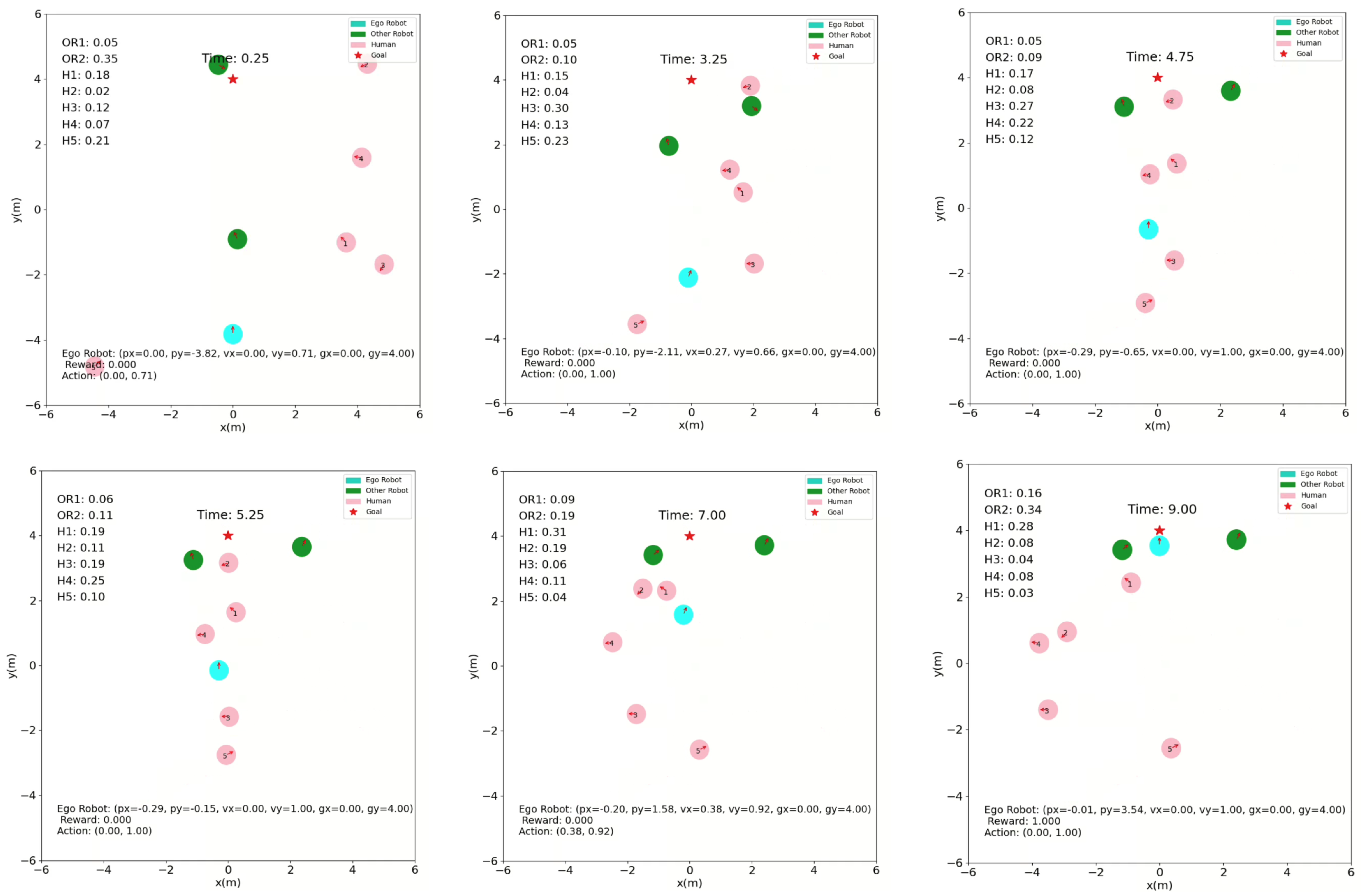

4.2. Qualitative Results

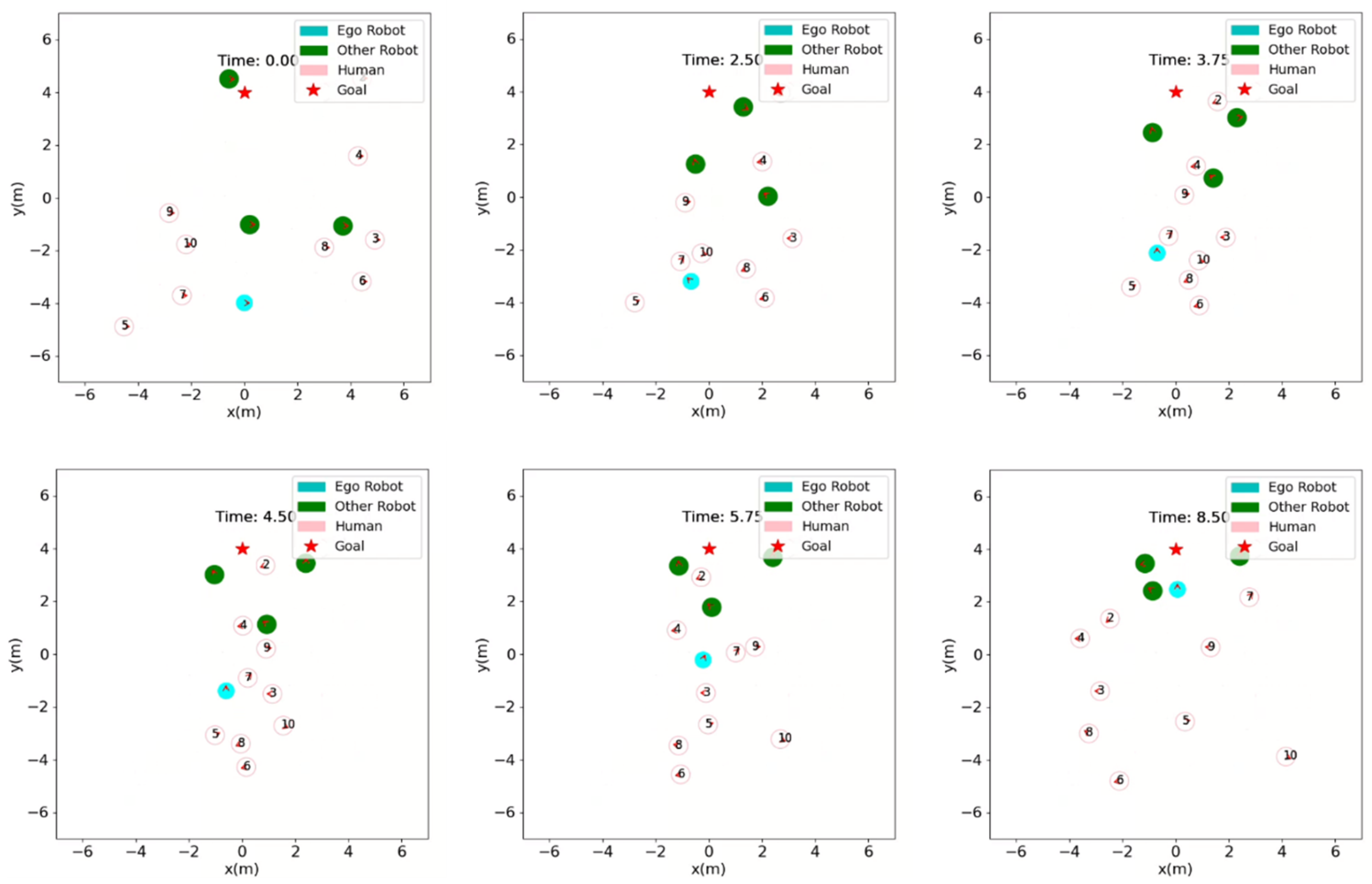

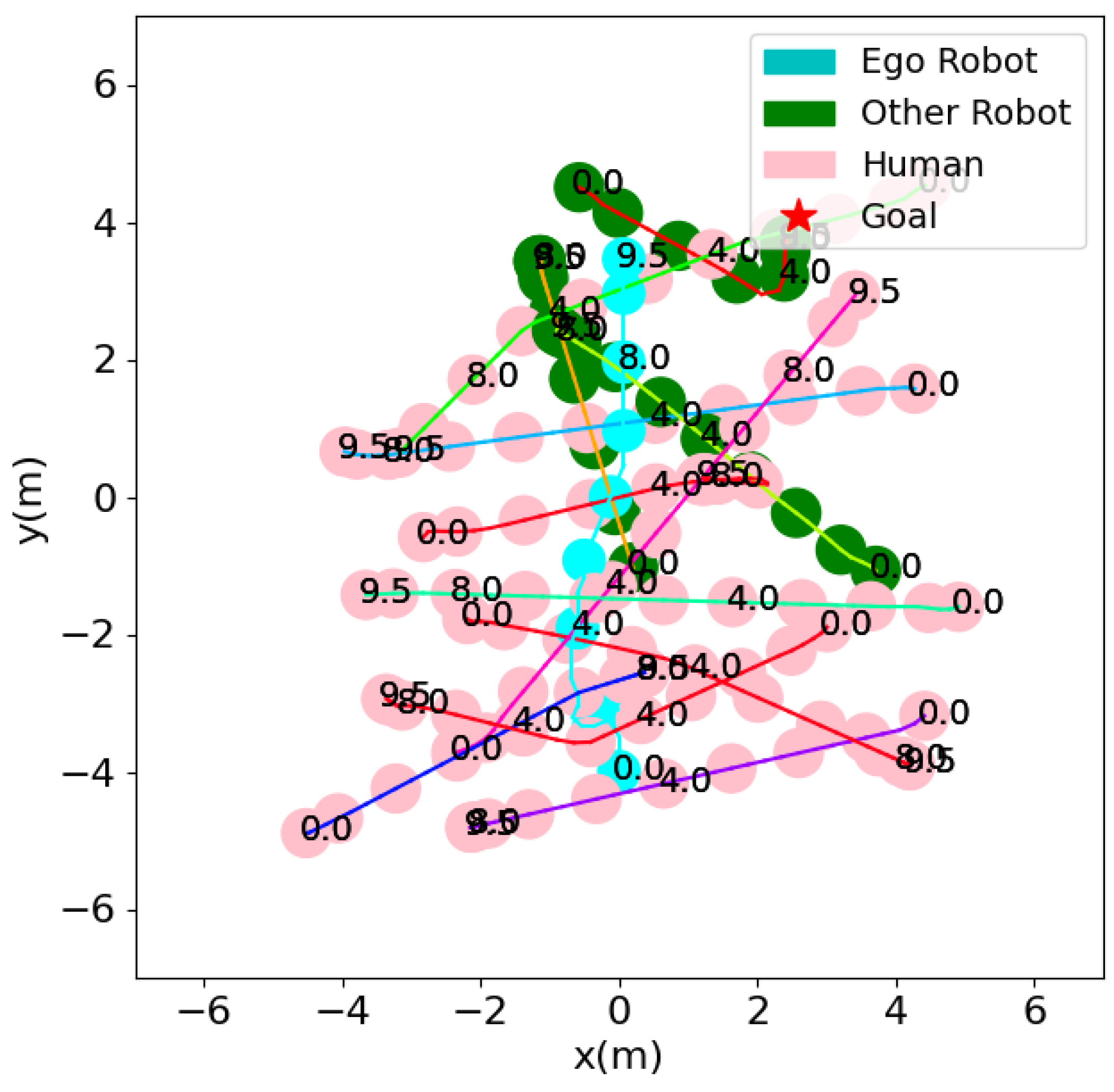

4.2.1. Open Space Scenario

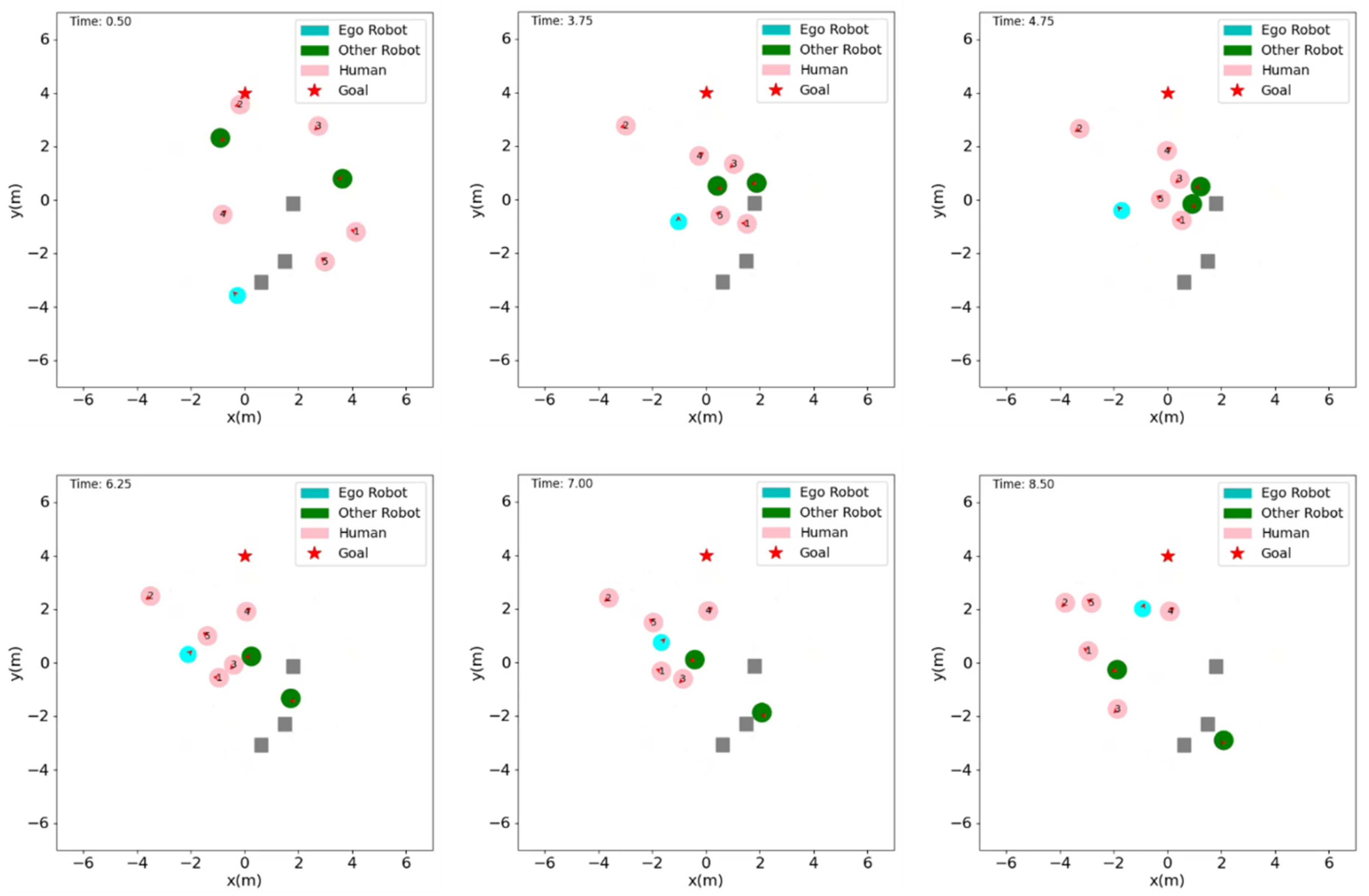

4.2.2. Static Obstacles Scenario

4.3. Quantitative Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivanov, S.; Gretzel, U.; Berezina, K.; Sigala, M.; Webster, C. Progress on robotics in hospitality and tourism: a review of the literature. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 2019, 10, (4), 489–521. [CrossRef]

- Personal space: An evaluative and orienting overview. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-23561-001 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Hall, Edward T.; Birdwhistell, Ray L.; Bock, Bernhard; Bohannan, Paul; Botkin, Daniel; Chapple, Eliot D.; Fischer, John L.; Hymes, Dell; Kimball, Solon T.; Monson, Munro S.; others. Proxemics [and comments and replies]. Current Anthropology 1968, 9, (2/3), 83–108.

- Kruse, Thibault; Pandey, Amit Kumar; Alami, Rachid; Kirsch, Alexandra. Human-aware robot navigation: A survey. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2013, 61, (12), 1726–1743. [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Ruiz, Silvia; Bandera, Juan Pedro; Hidalgo-Paniagua, Alejandro; Bandera, Antonio. Evolution of socially-aware robot navigation. Electronics 2023, 12, (7), 1570. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yujing; Zhao, Fenghua; Lou, Yunjiang. Interactive model predictive control for robot navigation in dense crowds. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2021, 52, (4), 2289–2301. [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, Paolo; Shiller, Zvi. Motion planning in dynamic environments using velocity obstacles. The International Journal of Robotics Research 1998, 17, (7), 760–772.

- Van den Berg, Jur; Guy, Stephen J.; Lin, Ming; Manocha, Dinesh. Reciprocal n-body collision avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2011; pp. 1928–1935.

- Helbing, Dirk; Molnar, Peter. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Physical Review E 1995, 51, (5), 4282–4286. [CrossRef]

- Aoude, Georges S.; Luders, Brandon D.; Joseph, Joshua M.; Roy, Nicholas. Probabilistically safe motion planning to avoid dynamic obstacles with uncertain motion patterns. Autonomous Robots 2013, 35, 51–76.

- Svenstrup, Mikael; Bak, Thomas; Andersen, Hans Jørgen. Trajectory planning for robots in dynamic human environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2010; pp. 4293–4298.

- Fulgenzi, Chiara; Tay, Christopher; Spalanzani, Anne; Laugier, Christian. Probabilistic navigation in dynamic environment using rapidly-exploring random trees and Gaussian processes. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2008; pp. 1056–1062.

- Trautman, Peter; Krause, Andreas. Unfreezing the robot: Navigation in dense, interacting crowds. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2010; pp. 797–803.

- Chen, Yu Fan; Liu, Miao; Everett, Michael; How, Jonathan P. Decentralized non-communicating multiagent collision avoidance with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2017; pp. 285–292.

- Chen, Yu Fan; Everett, Michael; Liu, Miao; How, Jonathan P. Socially aware motion planning with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2017; pp. 1343–1350.

- Everett, Michael; Chen, Yu Fan; How, Jonathan P. Motion planning among dynamic, decision-making agents with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2018; pp. 3052–3059.

- Tai, Lei; Zhang, Jingwei; Liu, Ming; Burgard, Wolfram. Socially compliant navigation through raw depth inputs with generative adversarial imitation learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2018; pp. 1111–1117.

- Pfeiffer, Mark; Schaeuble, Michael; Nieto, Juan; Siegwart, Roland; Cadena, Cesar. From perception to decision: A data-driven approach to end-to-end motion planning for autonomous ground robots. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2017; pp. 1527–1533.

- Albrecht, Stefano V.; Christianos, Filippos; Schäfer, Lukas. Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning: Foundations and Modern Approaches; Publisher: MIT Press, 2024.

- Chandra, Rohan; Zinage, Vrushabh; Bakolas, Efstathios; Biswas, Joydeep; Stone, Peter. Decentralized multi-robot social navigation in constrained environments via game-theoretic control barrier functions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10966, 2023.

- Escudie, Erwan; Matignon, Laetitia; Saraydaryan, Jacques. Attention graph for multi-robot social navigation with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.17914, 2024.

- Wang, Pengyuan; Chen, Yue; He, Yu; Guo, Yuhang; Wang, Xinyu; Wang, Yijie; Wang, Jun; Wang, Chenguang. Multi-robot task assignment with deep reinforcement learning: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2024; pp. 1–8.

- Chen, Changan; Liu, Yuejiang; Kreiss, Sven; Alahi, Alexandre. Robot social navigation in crowded environments: A deep reinforcement learning perspective. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine 2020, 27, (3), 154–167.

- Samsani, Sumanth; Maeng, JunYoung; Silva, Zachary; Faig, Jeremy; Manocha, Dinesh. Socially-aware robot navigation using deep reinforcement learning. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2021, 141, 103757.

- Wang, Pengyuan; Chen, Yue; He, Yu; Guo, Yuhang; Wang, Xinyu; Wang, Yijie; Wang, Jun; Wang, Chenguang. Multi-robot task assignment with deep reinforcement learning: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2024; pp. 1–8.

- Dong, Ziyi; Shi, Xijun; Huang, Jinbao; Cui, Jingzhe; Xue, Bin; Zhang, Zexi; Wang, Yang. Multi-robot cooperative target tracking via multi-agent reinforcement learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, (6), 5532–5539. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ziyu; Chen, Yutao; Hou, Yixiao; Hou, Yue. Hypergrids: A method for multi-robot cooperative exploration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.00000, 2024.

- Song, Yihan; Hu, Huimin; Kou, Xiangyang; Zhang, Xiaodong. Local target driven navigation for mobile robots in dynamic environments. Sensors, 2022.

- Zhou, Xinyu; Piao, Songhao; Chi, Wenzheng; Chen, Liguo; Li, Wei. HeR-DRL: Human aware reinforcement learning for robot navigation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2025.

- Paszke, Adam; Gross, Sam; Chintala, Soumith; Chanan, Gregory; Yang, Edward; DeVito, Zachary; Lin, Zeming; Desmaison, Alban; Antiga, Luca; Lerer, Adam. Automatic differentiation in PyTorch. 2017.

- Brockman, Greg; Cheung, Vicki; Pettersson, Ludvig; Schneider, Jonas; Schulman, John; Tang, Jie; Zaremba, Wojciech. OpenAI Gym. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.01540, 2016.

- Kingma, Diederik P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

- Chen, C.; Hu, S.; Nikdel, P.; Mori, G.; Savva, M. Relational graph learning for crowd navigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 10007–10013.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, P.; Zeng, Z.; Xiao, J.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Z. Robot navigation in a crowd by integrating deep reinforcement learning and online planning. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, (13), 15600–15616.

- Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Kreiss, S.; Alahi, A. Crowd-robot interaction: Crowd-aware robot navigation with attention-based deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 6015–6022.

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Gao, M. ST2: Spatial-temporal state transformer for crowd-aware autonomous navigation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 8, (2), 912–919. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dugas, D.; Cesari, G.; Siegwart, R.; Dubé, R. Robot navigation in crowded environments using deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 5671–5677.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Preferred velocity | 1.0 m/s |

| Radius of all agents | 0.3 m |

| Discomfort distance for humans | 0.2 m |

| Hidden units of | 150, 100 |

| Hidden units of | 100, 50 |

| Hidden units of | 100, 100 |

| Hidden units of | 150, 100, 100 |

| IL training episodes | 2000 |

| IL epochs | 50 |

| IL learning rate | 0.01 |

| RL learning rate | 0.001 |

| Discount factor | 0.9 |

| Training batch size | 100 |

| RL training episodes | 6000 |

| Exploration rate in first 4000 episodes | 0.5 to 0.1 |

| Works | Success Rate (%) | Collision Rate (%) | Navigation Time (s) | Discomfort Rate (%) | Avg. Min. separation distance (m) | No of Training episodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work | 89.0 | 0.15 | 12.13 | 6 | 0.16 | 6000 |

| HeR-DRL [29] | 96.54 | 3.14 | 10.88 | 6.9 | 0.154 | 15000 |

| HoR-DRL [29] | 96.05 | 3.06 | 10.91 | 7.8 | 0.15 | 10000 |

| LSTM-RL [16] | 85.52 | 5.49 | 11.52 | * | 0.147 | * |

| SARL [35] | 93.14 | 4.34 | 10.83 | * | 0.154 | 10000 |

| ST2 [36] | 96.46 | 2.99 | 11.08 | * | 0.149 | 1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).