1. Introduction

The Epstein Barr virus (EBV), taxonomically classified as Lymphocryptovirus humangamma4, is one of the most widely distributed human viruses, with a prevalence exceeding 95% in the adult population (Yu & Robertson, 2023). EBV is the etiological agent of infectious mononucleosis; which may develop after primary infection and presents with a higher incidence in developed countries in comparison to developing ones, where primary infection occurs in childhood and is usually asymptomatic (Chabay & Preciado, 2013; Hsu & Glaser, 2000). While acting as a harmless passenger in most cases, it may also behave as a tumor driver co-factor (Tzellos & Farrell, 2012). In this sense, EBV is associated with lymphoid neoplastic processes such as Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL), Burkitt's lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), as well as epithelial tumors like gastric carcinoma (GC) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (Chabay et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2022).

Based on sequence variations mainly in EBNA2 and the EBNA3 gene family, EBV is classified into two types, EBV1 and EBV2; however, genomic variation exceeds this set of genes (Yu & Robertson, 2023). Moreover, each EBV type displays its own geographical circulation pattern; while EBV1 is globally distributed and is generally more prevalent than EBV2 across most regions, in Sub-Saharan Africa the prevalence of both viral types is similar. Conversely, certain tropical areas such as Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Northern Brazil, exhibit a higher circulation of EBV2 genomes. Although the grounds for the higher prevalence of EBV2 in tropical regions is not fully understood, a potential selective advantage for this viral type in populations chronically exposed to immunomodulating infections, like endemic malaria or other tropical diseases, may exist (Farrell & White, 2021; Monteiro et al., 2020). Beyond its distinct geographic distribution, EBV2 has been identified more frequently in immunosuppressed individuals in any geographic region, such as patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or individuals with inborn errors of immunity (Neves et al., 2017; Tzellos et al., 2014). Regarding virus-host interactions, EBV1 has a greater capacity to transform B-lymphocytes in culture compared to EBV2, due to amino acid differences in the transactivation domain of EBNA2 (Rickinson et al., 1987). Another phenotypic difference observed between both viral types is that EBV2 in vitro infected B cells exhibit a higher expression of lytic proteins compared to those infected with EBV1 (Bristol et al., 2022; Romero-Masters et al., 2020). This latter difference could be attributed to the presence of the Zp-V3 variant of the BZLF1 gene promoter in all EBV2 genomes, whereas the prototypical Zp-P (also referred as Zp-V1) variant predominates in EBV1 (Farrell & White, 2021). The Zp-V3 variant in the promoter region of the BZLF1 gene contains an additional binding site for the cellular transcription factor NF-AT, which increases the transcription of the viral gene, whose protein product Zta plays a crucial role in inducing the switch from viral latency to lytic cycle (Bristol et al., 2018).

Recent advances in the number of complete EBV genomes and the development of bioinformatics tools have enabled more precise classification of viral variants and types. Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) comparison between viral types demonstrated that although sequence differences are mainly located in the EBNA2 and the EBNA3 gene family, variation also extends to the BLLF1 and BZLF2 genes, which encode for the membrane glycoproteins gp350/220 and gp42, respectively (Correia et al., 2017, 2018). Even though viral types represent the largest natural variation within the EBV genome, several authors have observed differential geographical circulation of genomic variants within EBV1 (Bridges et al., 2019; Palser et al., 2015). Moreover, in a previous report our group further identified the variable positions that contribute to this geographic segregation in EBV1 genomes (Blazquez et al., 2021). However, the variability in EBV2 genomes has been less explored due to the smaller number of sequenced genomes, a fact that could be attributed to its restricted geographical distribution. Given that the proportion of EBV2 genomes circulating in South America is steadily increasing (Monteiro et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2023), this study aims to extensively investigate the variability of EBV2 genomes in a geographical context and compare it with EBV1 variability.

2. Results

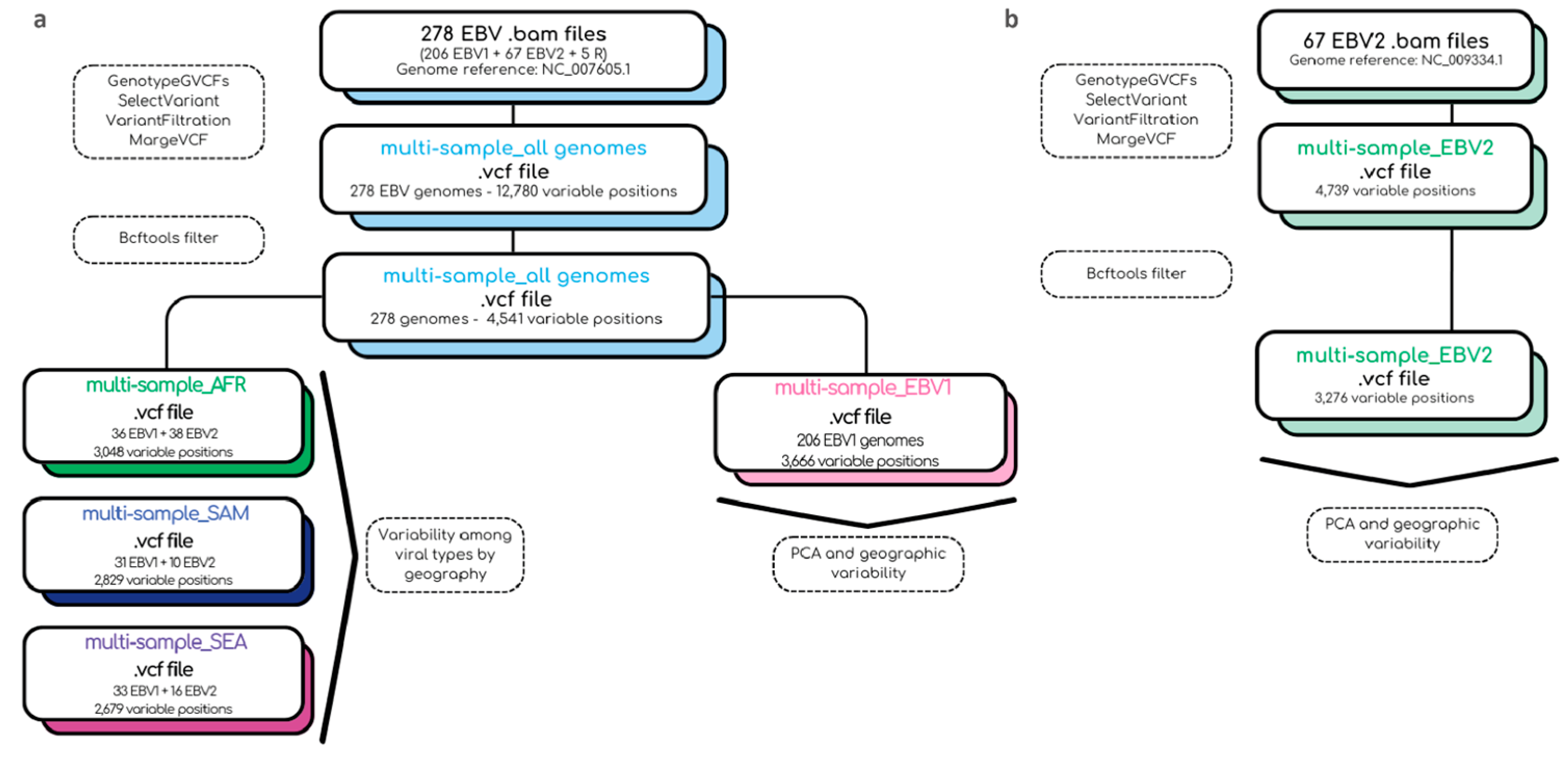

Complete EBV genome sequencing was performed in isolates from Argentina and analyzed together with raw data from different geographic origins to produce a viral type and geography-balanced data-set. Viral typing and recombination analysis between EBV types was assessed and 206 genomes were typed as EBV1, 67 as EBV2 and 5 as potential intertype recombinants; in particular, 28 Argentine genomes were classified as EBV1, 10 as EBV2, and one as a potential recombinant (see

Supplementary Table S2). Inter type recombinations were confirmed through

de novo assembly and further phylogenetic reconstruction of the EBNA2 gene and the EBV1 and EBV2 references showed that 4 isolates segregated with the EBV1 reference and one segregated with the EBV2 reference (see

Supplementary Figure S1a). Additionally, the same strategy was also implemented for the EBNA3 family of genes, revealing that 4 isolates clustered with the EBV2 reference, while the other one segregated with the EBV1 reference (see

Supplementary Figure S1b). Based on these findings, 4 genomes represented EBV1-EBV2 recombinants (ERS549494, ERS549475, ERS17911187 and ERS1791207), while the remaining one, an Argentinean isolate, represented an EBV2-EBV1 recombinant (SRR29321001). Finally, unequivocal recombination events were confirmed and precise braking-point locations were assessed with RDP4 (see

Supplementary Table S3).

2.1. Variability Between EBV1 and EBV2 Genomes

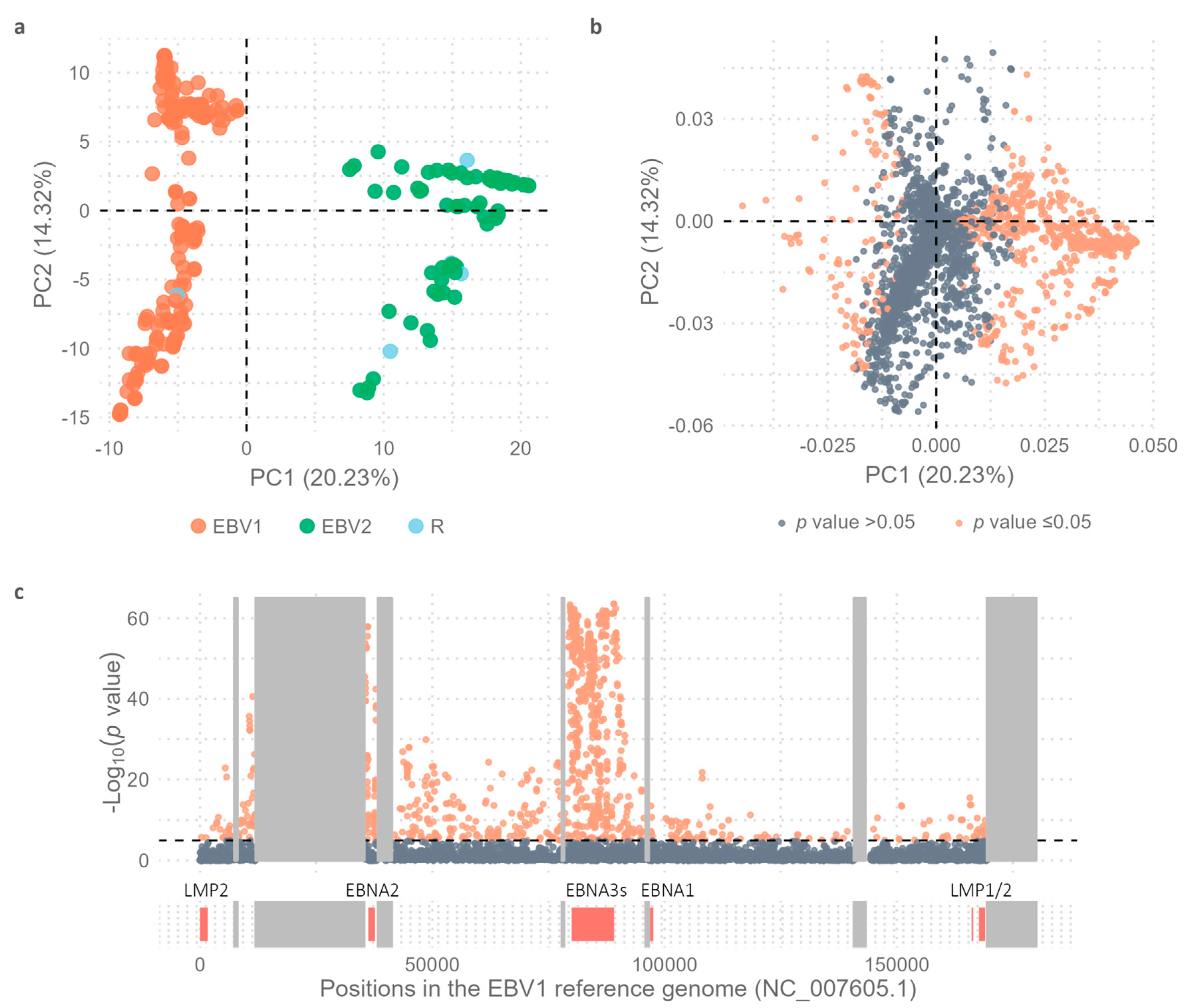

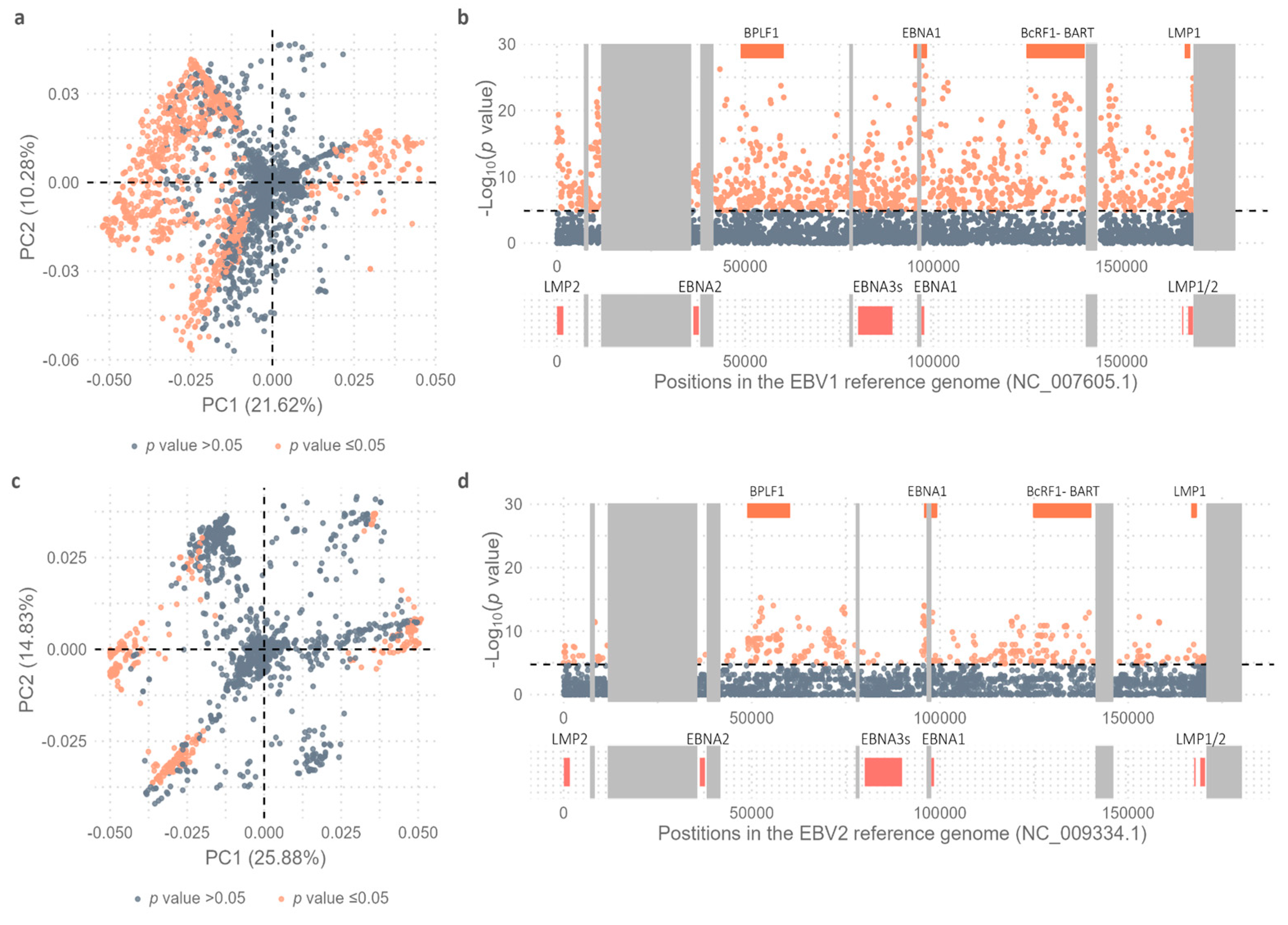

As expected, based on the Principal Component 1 (PC1 = 20.23%) in the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), EBV1 genomes were significantly segregated from EBV2 genomes (Wilcoxon test,

p value < 2.2 x 10

-16) (

Figure 2a). Intertype variability of the complete EBV genomes was further analyzed by PCA using a

multi-sample_all genomes.vcf file, which contained 4,541 variable positions (4,412 SNPs and 129 INDELs), as an input file (

Figure 1a).

Given that the strong linkage disequilibrium between variants in EBNA2 gene and the EBNA3 gene family with EBV type may not be the only type-specific variations along the genome, we sought to explore the presence of other characteristic polymorphisms contributing to the segregation of viral types. In this second analysis, the contribution of PC1 of each of the 4,541 variable positions between EBV1 and EBV2 genomes was evaluated using Fisher's exact test to quantify the contribution of each variable position to the segregation of viral types (

Figure 2b,c). As observed in

Figure 2B, the further a value is from the ordinate axis, the greater the contribution of that variant to PC1, which is reflected in increasingly significant

p values. In this way, 1093 variable positions showed statistical strength to segregate both viral types.

Figure 2c represents the distribution of these variable positions along the viral genome, as well as the significance of their contribution to the segregation of viral types, based on the -Log

10(

p value) obtained. In this way, from a total of 58 variable positions in EBNA2, 21 (36.20%) showed statistical strength to segregate viral types. Similarly, 542 from 819 (66.17%) were characterized in the EBNA3 family of genes and 24/59 (40.67%) in BZLF1, 12/19 (63.15%) in BZLF2 and 38/79 (48.10%) in BLLF1 genes (see

Supplementary Table S4). Although the major genetic differences among viral types lie within the EBNA2 gene and the EBNA3 gene family, intertype variability also extends into the region adjacent to the EBNA3 genes, particularly affecting the BZLF1, BZLF2, and BLLF1 genes.

Regarding the BZLF2 gene, which codes for glycoprotein gp42, significant differences were observed between both viral types at 12 variable positions within the coding region. Among these, 5 missense variants were exclusively harbored by EBV2 genomes: Ala38Ser, Val76Ile, Gln92Lys, Gly113Glu and Cys114Arg (see

Supplementary Table S4). Similarly, for the BLLF1 gene, coding for glycoprotein gp350/220, 36 variable positions with significant differences between both viral types were identified. Polymorphisms in the N-terminal region of this protein exhibited the most significant type-specific segregation strength, where Pro31Leu, Val48Ala, Gln60Lys, Asp62Asn and Gln67Leu were exclusively found in EBV2 genomes, while His17Gln, Gly20Arg, Glu21Asp, Thr38Ala and Val115Ile were more prevalent in EBV2 but also found in EBV1 from OCE (see

Supplementary Table S4). With respect to the promoter region of the BZLF1 gene, 4 EBV2 genomes failed to fully cover this region; in consequence the Zp-V3 variant (91,006 A>C, 91,012 T>C, and 91,047 T>C) was found in 64/206 EBV1 genomes and in 63/63 EBV2 isolates. On the other hand, the Zp-P variant was identified in 142/206 EBV1 isolates and was absent in EBV2 isolates; thus, implying a strict association of the Zp-V3 variant with EBV2 genomes (Fisher's exact test;

p value < 2.2 x 10

-16). Finally, on the coding region of the BZLF1 gene, coding for Zta protein, 9 missense variable positions and 1 disruptive in frame deletion with significant segregating strength between both viral types were found: Thr68Ala, Ser76Pro, Ala127del, Ala135Thr, Val146Ala, Val152Ala, Gln163Leu, Glu176Asp, Gln195His and Ala205Ser. While Thr68Ala, Ser76Pro, Ala135Thr, Val146Ala, Val152Ala, Gln163Leu, Glu176Asp, Gln195His and Ala205Ser were more prevalent in EBV2 genomes, Ala127del was a hallmark deletion of EBV1 (see

Supplementary Table S4). In summary, BZLF1, BZLF2, and BLLF1 genes all displayed EBV2 type-specific variable positions.

In order to assess the variability between EBV1 and EBV2 genomes isolated in each geographic region, three additional

multi-sample_all genomes.vcf files based on the geographical origin of the isolates (

multi-sample_SAM.vcf, multi-sample_SEA.vcf and

multi-sample_AFR.vcf) were constructed and used as input for PCA. Within each region, intertype variability was evaluated and 870/3,048 variable positions that differentiate between both viral types in AFR (

see Supplementary Table S5), 509/2,829 in SAM (see

Supplementary Table S6), and 531/2,679 in SEA (see

Supplementary Table S7) were characterized. As described above for the entire dataset, inter-type segregation potential remained in the EBNA2 gene, the EBNA3 gene family and the adjacent BZLF1, BLLF1 and BZLF2 genes when assessing geographic regions independently. Even though type-segregation potential was retained by the latter genes across all the geographies, variable positions in BZLF2 gene (Ala38Ser, Val76Ile, Gln92Lys, Gly113Glu, and Cys114Arg) were not capable of discriminating sequences by geographic origin. On the contrary, amino acid changes in the C-terminal domain of the gp350/220 protein (Asp441Ala, Trp495Arg, Asn672Ile, Ile710Thr, Gln754Lys and Pro812Thr) showed a higher prevalence among EBV2 isolates from Africa. On the other hand, BZLF1 displayed the greatest type segregation potential in each region. Regarding the gene´s coding region, the missense variable position resulting in Glu176Asp change showed significant differences between EBV1 and EBV2 in the three geographic regions (0/33 in EBV1 and 10/16 in EBV2 in SEA; 0/36 in EBV1 and 37/38 in EBV2 in AFR and 0/31 in EBV1 and 10/10 in EBV2 in SAM); meaning an association of EBV2 isolates with Glu176Asp (Fisher's exact test;

p value < 2.2 x 10

-16). Since the Glu176Asp is a hallmark of the BZLF1-A2 haplotype, this haplotype resulted to be associated with EBV2 across all geographies. Unlike SEA, where only the Glu176Asp amino acid showed segregation strength between viral types, in AFR and SAM the amino acid changes Thr68Ala, Ser76Pro, Val152Ala, Gln163Leu, Glu176Asp, Gln195His and Ala205Ser also displayed type-specific segregation strength and occurred preferentially in EBV2 genomes.

From the multi-sample.vcf files, the Zta protein haplotypes of each viral genome were identified. This analysis showed that 100% of EBV2 genomes (67 isolates) contained the BZLF1-A haplotype. Conversely, among EBV1 isolates, the BZLF1-A (17/33) and BZLF1-B (13/33) haplotypes were more prevalent in SEA, while the BZLF1-C haplotype was the most common in AFR (20/36) and BZLF1-B haplotype the most common in SAM (17/31). With respect to the BZLF1 gene promoter region, all EBV2 genomes harbored the Zp-V3 haplotype; however, the association of the Zp-V3 haplotype with EBV1 differed among the studied geographic origins. This haplotype showed a higher prevalence among SEA EBV1 (17/33) isolates with respect to AFR (7/36) and SAM (5/30) genomes (Fisher's exact test; p value = 0.00096).

Additional discrepancies between EBV1 and EBV2 isolates were also observed across the rest of the viral genome and these differences were grouped into three distinct blocks other than the above mentioned genes, as indicated in

Figure 3. The first block extended from 46,603 to 74,593 bp and included the coding region of genes BFRF1, BFRF2, BFRF3, BPLF1, BOLF1, BORF1, BORF2, BaRF1, BMRF1, BMRF2, BSLF2/BMLF1 and BSLF1. The variability within this block varied across the three geographic regions, with a higher number of variable positions (109/473) observed in the AFR isolates and the lesser (1/392) in SEA ones (Fisher's exact test;

p value

: < 2.2x 10

-16). On the other hand, SAM genomes harbored 19/432 variable positions that significantly segregated EBV2 from EBV1. While variable positions contributing to intertype differentiation were distributed throughout the entire block in AFR genomes, in SAM genomes variability was preferentially concentrated around 50,000 bp and was predominantly located within the coding regions of the BFRF2, BFRF3, and BPLF1 genes (

Figure 3).

The second block comprised nucleotides 104,403 to 112,651 bp and displayed a lower number of variable positions that contributed to intertype differentiation across the three geographic regions; however, variable positions with type-segregating capacity were made evident in AFR (6/143), in SEA (9/121) and in SAM (2/113). Specifically, in SAM and AFR, variability was primarily concentrated in the BBLF2/BBLF3 gene. In contrast, in SEA, variable positions contributing to type diversity were mainly located within the BGLF4 and BGLF3 genes (

Figure 3).

Finally, the third block encompassed variable positions (60/397 in AFR, 20/296 in SEA and 0/324 in SAM) with type segregating strength between 151,703 and 169,016 bp (Fisher's exact test; AFR vs SEA

p = 0.0007); conversely, no significant differences were found between the two viral types in SAM isolates within this region. Among AFR and SEA isolates, these type segregating variable positions were mainly located within BARF0 and LMP1, but while AFR genomes contained variable positions distributed throughout the entire block, SEA isolates concentrated their type segregating variability near the terminal repeat (

Figure 3).

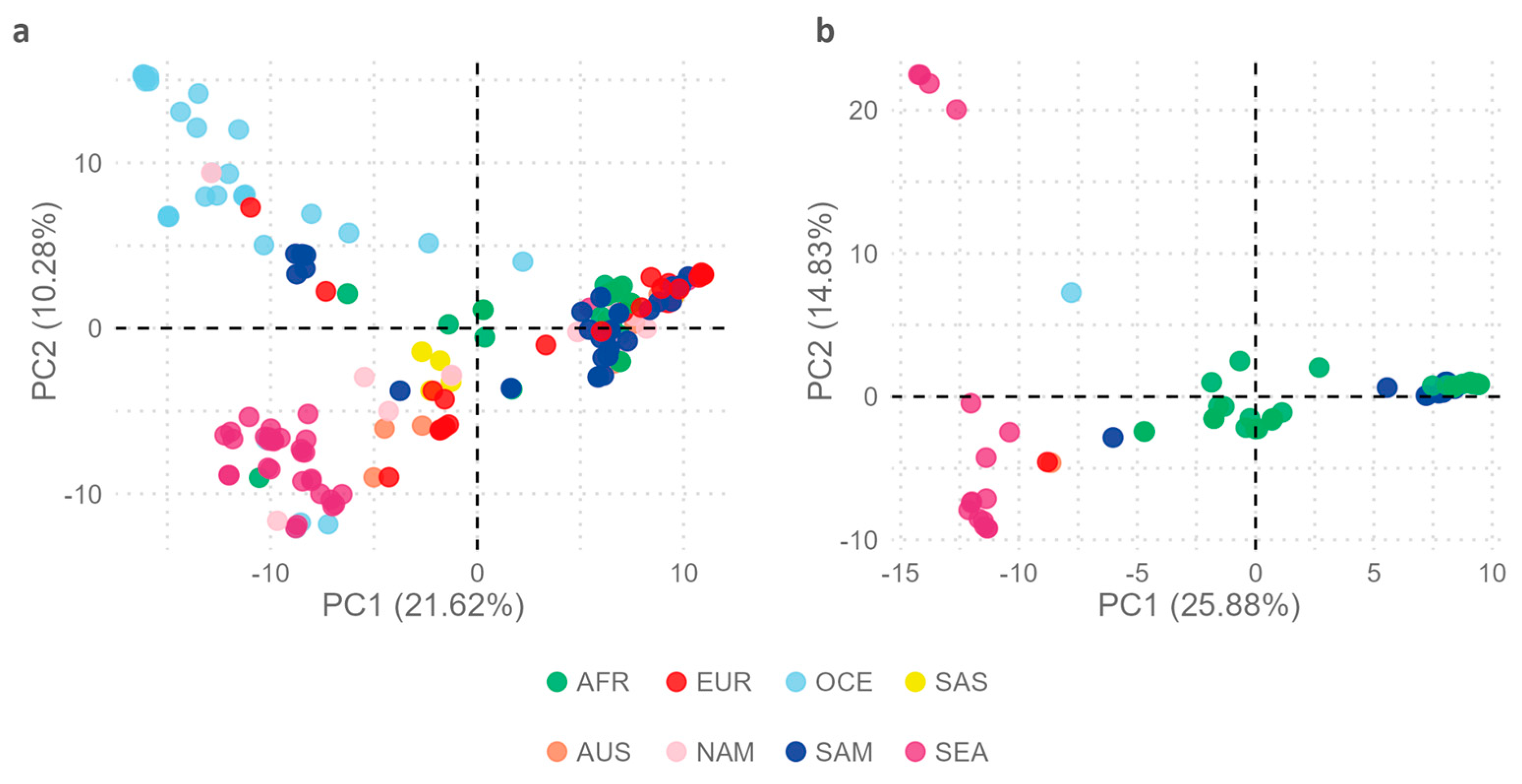

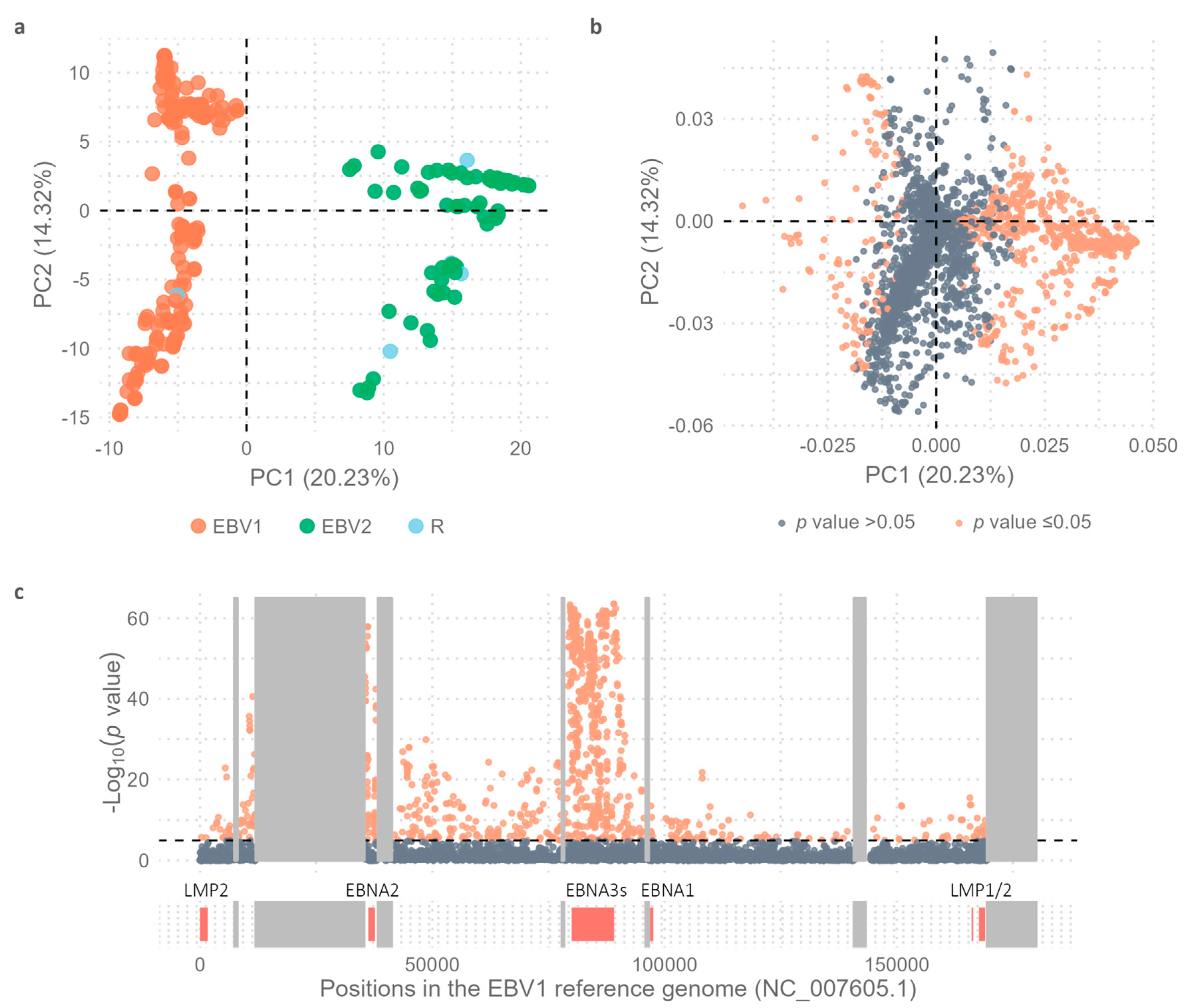

2.2. Comparative Geographic Variability Analysis in Each EBV Type

To further explore intratype variability in the geographic context, a new

multi-sample_EBV1.vcf file comprising 206 EBV1 genomes with 3,666 variable positions was constructed and used as an input file for PCA in order to assess the geographic segregation strength of variable positions in the EBV1 genomes. The relationship of each EBV1 genome with the first 2 principal components explains the segregation of sequences based on the geographical origin of the isolates (Kruskal-Wallis test,

p value PC1 < 2.2x 10

-16,

p value PC2 < 2.2x 10

-16) (

Figure 4a). In this way, PC1 (21.62%) explains the segregation of isolates from Oceania (OCE), South Asia (SAS), and Southeast Asia (SEA) from the rest of the world

[Africa (AFR), Europe (EUR), Australia (AUS), North America (NAM) and South America (SAM)], while the PC2 (10.28%) differentiates isolates from OCE and SEA. Additionally, the PC3 (6.35%) also contributes to explain the segregation of EBV1 genomes based on their geographical origin, in particular isolates from SAM from those from EUR, AUS, and SAS (Kruskal-Wallis test,

p = 1.06 x 10

-11) (see

Supplementary Figure S2).

In a similar way, to study the variability of EBV2 genomes in a geographical context, a

multi-sample_EBV2.vcf file was constructed from 67 EBV2 genomes and the EBV2 reference genome including 3,276 variable positions (3,155 SNPs and 121 INDELs) and was used as the input file for PCA. Geographical origin of EBV2 genomes was mainly restricted to AFR (38), SAM (10) and SEA (16), while only one was present in each OCE, EUR and AUS and none in SAS and NAM. In this PCA analysis, PC1 was able to discriminate EBV2 genomes according to geographical origin (Kruskal-Wallis test;

p = 1.37 x 10

-9) (

Figure 4b). In this way, PC1 (24.74%) allowed differential segregation of genomes from SEA compared to genomes from AFR (Wilcoxon test, Bonferroni correction;

p = 2.6 x 10

-9) and SAM (Wilcoxon test, Bonferroni correction;

p = 1.1 x 10

-7); however, it did not explain the variability between AFR and SAM genomes (Wilcoxon test, Bonferroni correction;

p = 1). Additionally, PC1 revealed two subpopulations of EBV2 in Africa, since 18 genomes presented with PC1 values close to 0 [median: 0.93; (Min.: -1.13 - Max.: 3.44)] and 19 genomes had PC1 values > 0 [median: 9.48; (Min.: 8.02 - Max.: 9.74)], a phenomenon not observed in the PCA derived from EBV1 genomes. On the other hand, PC2 (14.21%) contributed less in explaining the geographical segregation of EBV2 genomes (Kruskal-Wallis test;

p = 0.0027); similarly to PC1 it allowed the segregation of genomes from SEA with respect to isolates from AFR and SAM (Wilcoxon test, Bonferroni correction;

p = 0.023), but could not explain the variability between AFR and SAM genomes (Wilcoxon test, Bonferroni correction;

p = 1) (

Figure 4b).

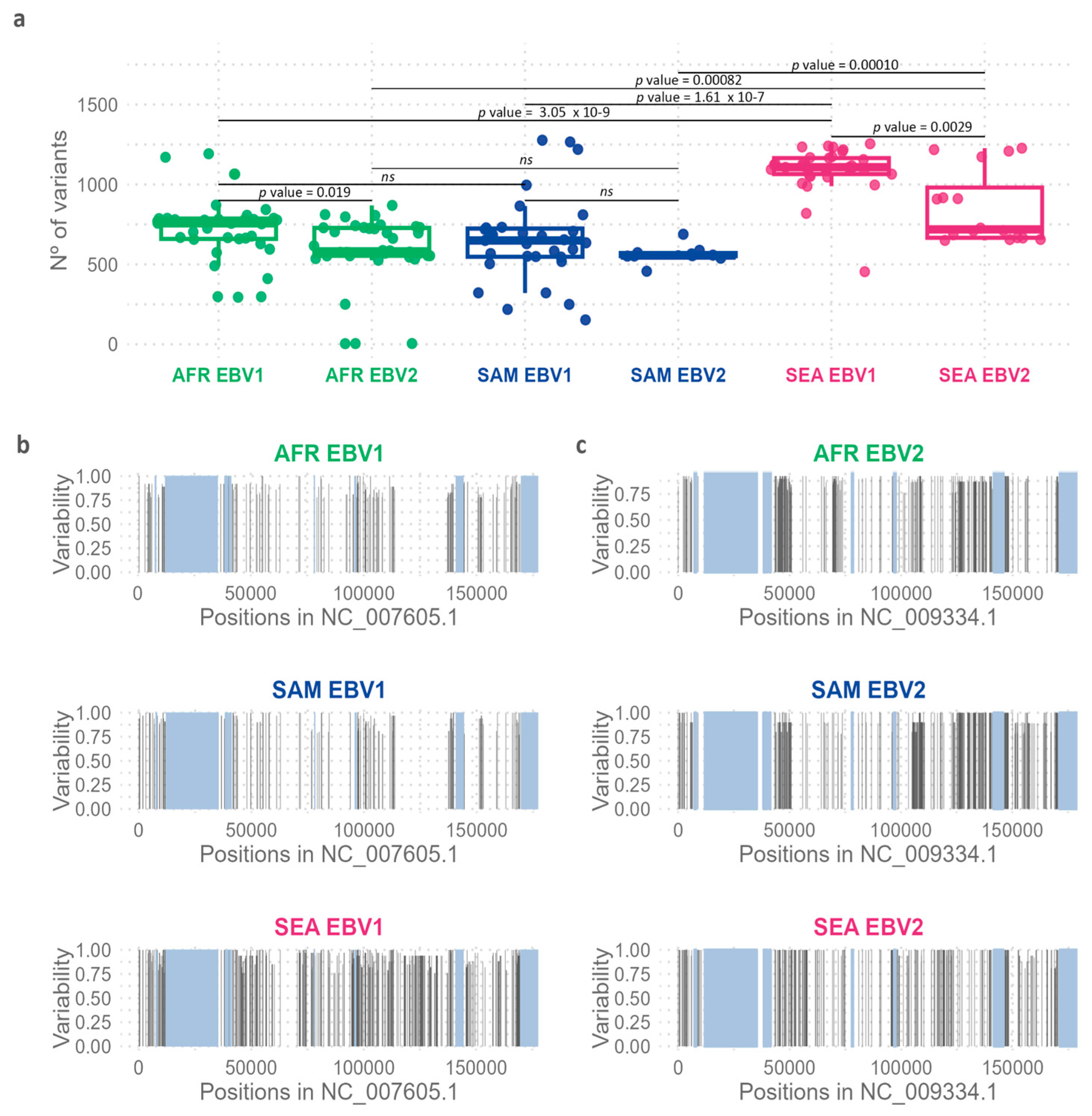

To further explore the observed geographic variability, the number of variable positions relative to the reference genome of EBV1 and EBV2 was quantified using the information from each m

ulti-sample.vcf files. A significant difference was observed between both viral types (Wilcoxon test,

p = 0.0001), with EBV2 showing less variability relative to its reference genome as compared to the variability of EBV1 isolates relative to the EBV1 reference. When considering each geographical origin independently, no significant differences in the median number of variants between viral types were found in SAM (Wilcoxon test,

p = 0.12); however, in AFR and SEA the median number of variants in EBV2, relative to its reference, was lower than that observed for EBV1 (Wilcoxon test,

p AFR = 0.019 and

p SEA = 0.0029) (

Figure 5a). In addition, the number of variable positions relative to the corresponding reference genome showed significant differences among geographic regions for both viral types (Kruskal-Wallis test;

p EBV1 = 3.69 x 10

-10;

p EBV2 = 0.00010). In this context, EBV genomes from SEA, regardless of the viral type, showed a higher number of variable positions in comparison to that observed in isolates from AFR (Wilcoxon test;

p EBV1 = 3.05 x 10

-9;

p EBV2 = 0.00082); and SAM (Wilcoxon test;

p EBV1 = 1.61 x 10

-7;

p EBV2 = 0.00010) (

Figure 5a). Common variable positions, present in more than 75% of the sequences, were plotted in relation to their positioning in the genome to further analyze and compare their precise location along each type-specific genome in each geographic region (see

Supplementary Table S8,

Figure 5b,c). With these settings, variable positions in SEA EBV1 genomes are distributed evenly throughout the entire viral genome; however, in SEA EBV2 genomes variable positions were restricted to discrete regions in the genome (

Figure 5c). On the other hand, variability patterns observed in AFR and SAM are similar, although type-specific. While in EBV1 genomes both AFR and SAM exhibited significant variability between 75,000 and 110,000 bp, EBV2 genomes concentrated the majority of variable positions in the region adjacent to 50,000 bp and the region between 110,000 and 150,000 bp.

To unequivocally identify those precise variable positions that contribute to the segregation of the genomes in relation to their geographic origin, the distribution and significance of each variable position in the

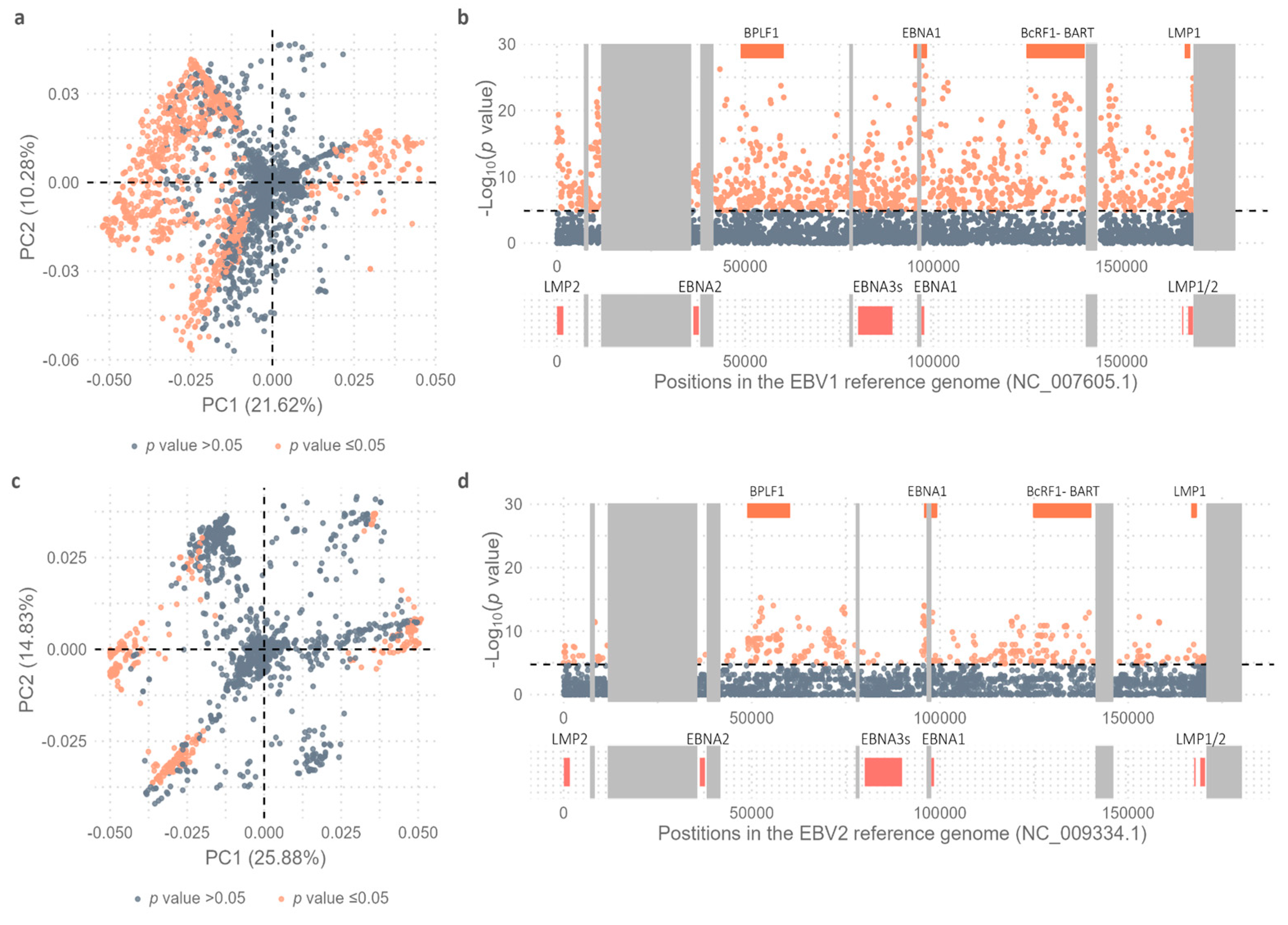

multi-sample_EBV1.vcf and

multi-sample_EBV2.vcf files were assessed for both viral types by a PCA (

Figure 6).

As described above in figure 4A and based on PCA results which showed that PC1 segregated two main geographical groups (SAS-SEA-OCE

vs AFR-SAM-NAM-EUR-AUS) and PC2 was able to separate OCE from SEA-SAS, the genomic positioning of these variable positions was further assessed. From the 3,666 variable positions considered, 1,135 (30.9%) showed the ability to discriminate isolates from SAS-SEA-OCE from the cosmopolitan group (see

Supplementary Table S9,

Figure 6a). When plotting the distribution of variable positions along the viral genome, it was observed that the variability contributing to the diversity between the two geographical groups was distributed throughout the entire viral genome; however, the most significant variants were located in four main regions, namely in the BPLF1, EBNA1, BcRF1 and miR-BART, and LMP1 genes (

Figure 6b).

Similarly, precise variable positions contributing to the separation of EBV2 genomes into the previously identified geographic groups (SEA-OCE vs AFR-SAM) were assessed (

Figure 4b). Of the total 3,276 variable positions considered for EBV2, 380 (11.5%) showed the capability to discriminate SEA-OCE from AFR-SAM genomes; a number of significant variable positions smaller than that observed in EBV1 isolates (

Figure 6c, see

Supplementary Table S10). The most capable geography-segregating variants for EBV2 genomes were discretely distributed in 3 genomic regions, namely the BPLF1, EBNA1 and BcRF1 genes (

Figure 6d). In particular, variations in EBNA1, BcRF1 and BPLF1 genes contributed significantly to geographic diversity in both viral types. However, unlike EBV1, in EBV2 the EBNA3 gene family and adjacent genes did not exhibit differential variability between SEA and OCE as compared to AFR and SEA.

3. Discussion

In recent years, with the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, more than 1,000 complete genomes of EBV have been sequenced. Since most of the available EBV genomes in public databases correspond to EBV1, most evolution, geographic variability and pathology association studies have focused on this viral type. Consequently, and due to the smaller number of sequenced EBV2 genomes, its variability has not been fully explored (Blazquez et al., 2021; Correia et al., 2017; Hui et al., 2019; Kaymaz et al., 2020). Since EBV2 appears to be increasingly circulating in Argentina, this study aimed to identify variable genomic regions responsible for the segregation of EBV types and their geographic distribution, focusing on EBV2 variability in a previously underrepresented geographic region. Specifically, previous studies that evaluated the prevalence of both viral types in healthy carriers or children with benign infections demonstrated a circulation that ranged between 85% and 95% in favor of EBV1 (Correa et al., 2004; Lorenzetti et al., 2014). On the other hand, only certain tropical regions in South America, such as Colombia or northern Brazil, showed an increased circulation of EBV2 where its prevalence rose to 20% of healthy carriers (Alves et al., 2022; Arturo-Terranova et al., 2020). In this work, viral type distribution among the Argentinian isolates showed a higher prevalence of EBV1 (72%) over EBV2 (26%) genomes; however, the proportion of EBV2 genomes was higher than that previously reported for our country and for other regions, such as Europe and North America where EBV2 only represents about 10-15% of the circulating EBV (Correia et al., 2018; Farrell & White, 2021; Palser et al., 2015). Although all geographic regions were represented by at least one EBV2 isolate in our dataset of 278 genomes, given the restricted geographic circulation of EBV2, genomes from Africa, Southeast Asia and South America were the most prevalent; a fact that limited the study to these regions. Recombinant genomes were characterized; however, those from Africa and Papua New Guinea were characterized as EBV1-EBV2 recombinants while the Argentine recombinant genome presented with an EBV2 type EBNA2 gene and EBV1 type EBNA3 genes, which is, to the best of our knowledge, the first EBV2-EBV1 recombinant to be described.

In line with previous knowledge, EBV type 1 and 2 was the primary viral differentiation and was mainly driven by variations in the EBNA2 gene and the EBNA3 gene family (Correia et al., 2018; Hui et al., 2019; Palser et al., 2015); however, variable positions within EBNA3 family adjacent genes BZLF1, BZLF2 and BLLF1 also contributed to viral type differentiation. Here, we identified and quantified the type-segregation potential of a total of 74 variable positions in the above mentioned genes. A similar observation was previously reported by Correia et al., for the promoter region of BZLF1 gene, although variation in the coding region of the gene and the statistical significance of these variants to type segregation were not assessed (Correia et al., 2017). The Zp-V3 variant of the BZLF1 gene promoter was found with higher prevalence in EBV2 genomes. Some authors suggested that the Zp-V3 variant originally derives from EBV2, and its presence in some EBV1 genomes is due to ancestral intertype recombinations (Correia et al., 2017; Kaymaz et al., 2020). Among the EBV1 isolates, the Zp-V3 variant showed higher circulation in Southeast Asia and Oceania compared to other geographic regions. On the other hand, Zp-V3 variant was strictly associated with EBV2 genomes in Argentina and Africa; a result previously reported for Argentinean EBV2 genomes, although with a smaller number of isolates (Lorenzetti et al., 2009; Lorenzetti et al., 2014). Additionally, differences were also found between viral types in the coding region of the BZLF1 gene. In this regard, the EBV2 genomes exclusively harbored the BZLF1-A haplotype, regardless of geographic origin. On the other hand, geographic differences in Zta haplotypes were found for EBV1 genomes: while the BZLF1-A and BZLF1-B haplotypes were more prevalent in Southeast Asia, BZLF1-C prevails in Africa and BZLF1-B in South America. All together, these results align with previous findings which reported an association between the BZLF1-A haplotype and the Zp-V3 variant in EBV2 isolates (Alves et al., 2024; Lorenzetti et al., 2014). Furthermore, and also in line with Alves, et al., we disclosed the association of the Zp-P variant with the BZLF1-B haplotype in EBV1 genomes (Alves et al., 2024). Although the most frequent Zta haplotype in our Argentine cases was BZLF1-B, which is consistent to that reported by Alves et al. in Brazilian cases, our observation could be biased by the fact that only 4 infectious mononucleosis samples were included in the present series. In this regard, a previous work from our group reported that the BZLF1-C haplotype was the most prevalent among primary infection cases in Argentina (Lorenzetti et al., 2014). The possible impact of variants in the promoter and coding region of BZLF1 gene in the biology of EBV warrants further investigation. Bristol et al., reported a higher lytic phase activation in EBV2-infected B cells, and that this could be due to an increased expression of Zta protein under the Zp-V3 promoter haplotype (Bristol et al., 2018). However, an increased dimerization capacity (active form) of the Zta protein in EBV2-infected cells could not be discarded, given that most variable positions in the BZLF1-A haplotype are located in this domain.

Regarding BZLF2 gene, five missense variants in gp42 protein were identified as exclusively harbored by EBV2; four of which were previously characterized by Correia et al. as having type-differentiation strength (Correia et al., 2018). Notably, this study is the first to identify Val76Ile as an EBV2-specific variable position, enhancing the ability of BZLF2 to distinguish between EBV types. Since changes Ala38Ser, Val76Ile, and Gln92Ala were located in the gp42 interaction domain with gH, which extends from amino acid residues 36 to 96 (Sathiyamoorthy et al., 2016), and it was recently demonstrated that the interaction between gp42 and the gH/gL heterodimer defines cellular tropism (Hong et al., 2021; Jean-Pierre et al., 2021), the identified amino acid changes could affect gp42-gH interaction and hence, modulate the efficiency of EBV2 infection of B cells. Concerning the BLLF1 gene, ten variable amino acids with type-segregation force were found in the N-terminal domain of gp350/220 protein in EBV2; all of which could affect viral infection since this region contains the binding site for the CR2 cellular receptor, but also serves as epitopes for recognition by host neutralizing antibodies (Ahmed et al., 2023; Cohen, 2015; Sokal et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2017). Additionally, this finding also correlated with the results reported by Luo et al., who observed a significant association between 9 of the amino acid variants described here and EBV2 (Luo et al., 2012). Again, variant Gln67Leu was characterized here for the first time as having type segregation capacity for EBV2 isolates, further strengthening the ability of BLLF1 gene to distinguish between EBV types. A similar observation, although not referring to specific variable positions, was also reported by Correia et al., for the N-terminal domain of gp350/220 in EBV isolates from various geographic origins (Correia et al., 2017). The authors identified three clades in the phylogenetic reconstruction and suggested that the variability in the N-terminal region of this glycoprotein was not solely restricted to the viral type but also related to the geographic origin of viral isolates. Our results aligned with those of Correia et al., since variants with preferential circulation in OCE were also characterized. Finally, when studying intertype variability by geography, we characterized prevalent amino acid changes in EBV2 isolates from AFR but not in SAM or SEA. Examining variable positions in gp350/220 and gp42 glycoproteins of EBV2 could be valuable for vaccine design, particularly in regions with higher EBV2 prevalence. As a deeper layer in our analysis, provided by the contribution of new SAM isolates, further differences between EBV1 and EBV2 were noted throughout the remainder of the genome, and these variations were organized into three distinct genomic blocks apart from the previously mentioned genes.

When assessing intertype variation at the genomic level in those geographic regions where EBV2 is present, EBV2 displayed less variability than EBV1 in AFR and SEA, but not in SAM isolates. On the other hand, when focusing on the geographic origin of the isolates, those from SEA presented the greatest amount of variation irrespective of the viral type suggesting a closer relation between isolates from SAM and AFR. Moreover, the distribution of variable positions along the entire genome also differed in these isolates, where AFR and SAM also showed a common variability pattern of distribution for each viral type with a higher number of fixed positions for EBV2. Altogether, these results demonstrate a closer relation between EBV isolates from SAM and AFR and that EBV2 is less diverse than EBV1.

Although variability in EBV1 has been widely studied (Correia et al., 2017, 2018), EBV2 variability has been studied to a lesser extent and in particular, isolates from South America have been misrepresented. In this study, PCA allowed us to further explore the above mentioned variability patterns and unequivocally assess their statistical significance to viral type and geographic segregation. While it discriminated EBV1 isolates from SEA, SAS, and OCE from those from the rest of the world, it also revealed the geographic structure of EBV2 isolates, segregating SAM and AFR from SEA genomes. This latter finding for EBV2 was similar to that observed in our previous study for EBV1 (Blazquez et al., 2021). Here, when discriminated by viral type, both EBV1 and EBV2 genomes from SAM segregate together with the AFR isolates and differentiate from those from SEA. These clustering patterns further reinforce the theory that ancestral introduction of EBV to SAM might have been influenced by slave trading from Africa during the colonial period of South America (Avena et al., 2012; Blazquez et al., 2021). Furthermore, no geographically segregating positions were observed in the EBV2 EBNA3 gene family and its adjacent regions, a similar result to that of Kaymaz et al., who compared divergence levels between viral types in each gene and found a greater divergence in the EBNA3 gene family and adjacent genes among EBV1 isolates, but not in EBV2, from Kenya (Kaymaz et al., 2020). Similarly, EBV genes BPLF1, EBNA1, and BcRF1 contained the highest proportion of missense variants that contributed to the segregation of AFR and SAM genomes from those from SEA. Moreover, in this study, it was observed that in the three analyzed geographic regions, EBV2 genomes have fewer variable positions compared to the EBV2 reference genome than EBV1 isolates from these regions compared to the EBV1 reference. Consistent with this result, Kaymaz et al. compared divergence levels between viral types in AFR isolates and reported lower divergence in EBV2 genomes (Kaymaz et al., 2020).

Understanding how EBV genome variation correlates with geographic location could be essential not only in clarifying the virus's role in disease development but also support efforts toward creating an effective EBV vaccine, in particular in those regions where both EBV types are prevalent. Ongoing initiatives to create an EBV vaccine and/or antiviral treatments should incorporate knowledge in these variations to improve their efficacy.

4. Methods

4.1. Ethic Statement

The hospital's ethics committee, Comité de Ética en Investigación (CEI), has reviewed and approved this study (CEI No. 17.25), according to the human experimentation guidelines of our institution and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as amended in 1983. Clinical samples from patients with EBV infection were anonymized before the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients' parents or legal guardians.

4.2. Patients and Samples

This study included samples from 45 patients with EBV-associated pathologies from Argentina:

(i) 4 pediatric patients with infectious mononucleosis (IM), median age of 5.75 years (range 3 to 9 years), 75% male;

(ii) 4 pediatric patients with immunodeficiency, median age of 5 years (range 3 to 12 years), 50% male. Of the patients included in this group, 3 had secondary immunodeficiency following a liver transplant and one had a diagnosis of inborn error of immunity;

(iii) 35 pediatric patients with EBV-positive lymphomas (22 HL, 6 non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 7 PTLDs, median age of 9 years (range 3 to 14 years), 65.7% male and

(iv) 2 asymptomatic pregnant adult healthy carriers (24 and 29 years). The type of sample used in each case is indicated in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.3. DNA Extraction and Viral Load Analysis

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood with Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, GE17-1440-02, USA). Total DNA was purified from PBMCs, pharyngeal secretions, saliva, and fresh tumor biopsies using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 51304, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The number of EBV genome copies was measured in all samples using a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay on a LightCycler 480 device, as previously described (Blazquez et al., 2021). Samples with a viral load above 500,000 EBV copies/μg of total genomic DNA, were selected for targeted NGS sequencing.

4.4. Library Preparation and NGS Sequencing on the Illumina Platform

Sequencing libraries were constructed using SureSelect QXT Target Enrichment Kit (Agilent Technologies, G9683B, USA) and RNA capture probes specifically designed for EBV (Agilent Technologies, 5190-4806, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described (Blazquez et al., 2021). Finally, sequencing of the libraries was performed on the Illumina NexSeq500 system. The

.fastq files were deposited in the NCBI database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA679281 (see

Supplementary Table S1).

4.5. Bioinformatics, Viral Typing and Recombination Analysis Between Viral Types

To study the variability of isolates from Argentina within the geographical context, 242

.fastq files corresponding to EBV genomes isolated from various geographical regions (79 from Africa, 19 from Australia, 33 from Europe, 19 from North America, 3 from South America, 34 from Oceania, 5 from South Asia, and 50 from Southeast Asia) were downloaded from the SRA-NCBI database, corresponding to the Bioproject numbers PRJNA522388, PRJNA505149, PRJNA552587, PRJNA480052 and PRJEB2768 (see

Supplementary Table S1). The 287

.fastq files (45 generated and 242 downloaded) were analyzed using a bioinformatic pipeline based on a mapping strategy as previously described (Blazquez et al., 2021). In this way, 9 genomes (6 generated and 3 downloaded) with a coverage less than 50% were excluded from all further analysis. Since linkage disequilibrium was described between variants in EBNA2 gene and EBNA3 family of genes (Correia et al., 2018; Sample et al., 1990), and that these variants define EVB type, the remaining 278 genomes were typed based on coverage and the number of variants in these genes after mapping the reads against both viral reference genomes (NC_007605.1 for EBV1 and NC_009334.1 for EBV2) (Blazquez et al., 2021). For those viral genomes showing evidence of potential recombination events between viral types,

de novo assembly was performed using

Spades v.3.14.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012). Scaffolds were formed from the assembly of reads, which were aligned and ordered using the

ABACAS program v.1.3.1 (Assefa et al., 2009). Consensus sequences constructed in this way were aligned with the reference genomes of both viral types using

MAFFT v.7.450 (Katoh & Standley, 2013). Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed from the coding region of the EBNA2 and EBNA3A genes using

IQ-TREE v.1.6 (Nguyen et al., 2015). The statistical validation of each tree's topology was conducted with 1000 replicates using the ultrafast bootstrap method. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using the online software iTOL (

https://itol.embl.de/). Additionally, recombination signals were studied using nine different computational algorithms with

RDP4 program v.4.97 and the detection of a recombination event was considered significant when detected by at least three independent computational algorithms (Martin et al., 2015).

4.6. Bioinformatic Pipeline for the Construction of Multi-Sample .vcf Files

The quality of the reads was assessed using

FastQC v.0.12.1 (

http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). The programs

fastp v.0.20.1 (Chen et al., 2018) and

PRINSEQ v.0.20.4 (Schmieder & Edwards, 2011) were employed to remove low-quality ends, low-quality reads, PCR duplicates, and adapters. The reads were aligned to the reference genome of EBV1 using

BWA v.0.7.17-r1188x (Li & Durbin, 2009).

SAMTools v1.9 (Li et al., 2009) was then u

tilized to convert the resulting .sam files to .bam files. The intersect-v function of BedTools v2.29.2 (Quinlan & Hall, 2010) was used to remove reads aligning to repetitive regions and OriLyt. From the obtained .bam files, .gvcf files were generated using the HaplotypeCaller tool of GATK v4.1 (Genome Analysis Toolkit) (McKenna et al., 2010)

. Joint genotyping was performed from the .gvcf files of each sample using GATK v4.1 GenotypeGVCFs. The next step involved extracting variable positions, including both SNPs and INDELs, using the SelectVariants tool of GATK v4.1, to obtain a multi-sample.vcf file. Subsequently, VariantFiltration and the bcftools filter function of GATK v4.1 were employed to identify and extract viral variants that did not meet the established quality criteria; i) variable positions, present in fewer than five genomes, and ii) variable positions covered in less than 50% of the total genome (missing data) were removed using the bcftools filter tool. The aforementioned bioinformatic strategy was employed to construct a multi-sample_all genomes .vcf file based on the EBV1 reference genome consisting of 278 viral genomes. From this .vcf file, a second multi-sample_EBV1.vcf file exclusively composed of pre-typed EBV1 genomes was constructed to study the segregation and geographic variability of this viral type. On the other hand, to study the variability of EBV2, a new multi-sample_EBV2.vcf file was constructed using the reference genome for this viral type and t

he genomes previously typed as EBV2. Finally, to study intertype variability in each geographical region separately, data from the original

multi-sample_all genomes.vcf file, constructed from the NC_007605.1 reference and 278 genomes were used to construct three region-specific

multi-sample.vcf files (Africa, South America and Southeast Asia).

In all cases, the SnpEff v5.0 program was utilized for variant annotation and prediction of their effect on viral proteins (Cingolani et al., 2012)

. In summary, the bioinformatic pipeline used in this study and the files obtained in each step are described in Figure 1.

4.7. Principal Component Analysis

Using the multi-sample.vcf files as input, the adegenet package v2.1.10 (Jombart, 2008) was applied for Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The vcfR package v1.14.0 (Knaus & Grünwald, 2017) was employed for .vcf file manipulation.

4.8. Variant Frequency

From the annotated multi-sample.vcf files, the frequency of variation at each position of the EBV genome relative to the reference was assessed using the VCFTools v0.1.15 (Danecek et al., 2011). Comparisons were made between viral types and geographies to identify positions contributing to differentiation. When referring to variable positions in the BZLF1 gene or its protein product Zta, BZLF1 haplotypes were termed using the classification introduced by Luo et al. (Luo et al., 2011) and when referring to variable positions within the BZLF1 promoter region, haplotypes were termed according to the classification introduced by Gutierrez, et al. (Gutiérrez et al., 2002).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.0.2 (R Development Core Team, 2003). Normality was initially evaluated using the Shapiro test to compare distributions between groups. Normality assumption was rejected if at least one group had a p value < 0.05, in which case the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for comparisons among more than two groups, and the Wilcoxon test for pairwise comparisons. Fisher's exact test was used to assess association between categorical variables. All p values from multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. All other supplemental data is available at https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/248073.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.L. and M.V.P.; methodology, A.C.B.; software, A.C.B.; validation, A.C.B., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; formal analysis, A.C.B., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; investigation, A.C.B., M.D.F., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; resources, M.D.F., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; data curation, A.C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.B., M.D.F., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C.B., M.D.F., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; visualization, A.C.B., M.A.L. and M.V.P.; supervision, M.A.L. and M.V.P.; project administration, M.A.L. and M.V.P.; funding acquisition, M.A.L. and M.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Agency for Research, Technology Development and Innovation Promotion (Agencia I+D+i), grants PICT 2020 Nº 00854, PICT 2021 Nº 00121, PUE 2018 Nº 0058. M.A.L., and M.V.P. are members of the CONICET Research Career Program. A.C.B was a PhD fellow from the National Research Council (CONICET).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of “Hospital de Niños Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez” (protocol code CEI nº 17.25 approved on 28 November 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We extend a very special thanks to Dr. Ariel José Berenstein, former researcher at IMIPP, for his assistance in developing bioinformatic scripts. We also would like to thank Dr. Carolina Torres for assisting with biological interpretation of the data and Dr. Elena De Matteo, Dr. Guillermo Moscatelli and Dr. Jaime Altcheh for patients´sample collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed, N. , Rabaan, A. A., Alwashmi, A. S. S., Albayat, H., Mashraqi, M. M., Alshehri, A. A., Garout, M., Abduljabbar, W. A., Yusof, N. Y., & Yean, C. Y. Immunoinformatic Execution and Design of an Anti-Epstein-Barr Virus Vaccine with Multiple Epitopes Triggering Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P. D. , Rohan, P., Hassan, R., & Abdelhay, E. Lytic and Latent Genetic Diversity of the Epstein-Barr Virus Reveals Raji-Related Variants from Southeastern Brazil Associated with Recombination Markers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P. , Larrate, M., Garcia-Costa, A., Rohan, P., Gama, B. E., Abdelhay, E., Delatorre, E., & Hassan, R. Spatial Dispersal of Epstein-Barr Virus in South America Reveals an African American Variant in Brazilian Lymphomas. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arturo-Terranova, D. , Giraldo-Ocampo, S., & Castillo, A. Molecular characterization of Epstein-Barr virus variants detected in the oral cavity of adolescents in Cali, Colombia. Biomedica : Revista Del Instituto Nacional de Salud 2020, 40 (Suppl. 1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Assefa, S. , Keane, T. M., Otto, T. D., Newbold, C., & Berriman, M. ABACAS: algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1968–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Avena, S. , Via, M., Ziv, E., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Gignoux, C. R., Dejean, C., Huntsman, S., Torres-Mejía, G., Dutil, J., Matta, J. L., Beckman, K., Burchard, E. G., Parolin, M. L., Goicoechea, A., Acreche, N., Boquet, M., Ríos Part, M. D. C., Fernández, V., Rey, J., … Fejerman, L. Heterogeneity in genetic admixture across different regions of Argentina. PloS One 2012, 7, e34695. [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich, A. , Nurk, S., Antipov, D., Gurevich, A. A., Dvorkin, M., Kulikov, A. S., Lesin, V. M., Nikolenko, S. I., Pham, S., Prjibelski, A. D., Pyshkin, A. V., Sirotkin, A. V., Vyahhi, N., Tesler, G., Alekseyev, M. A., & Pevzner, P. A. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology: A Journal of Computational Molecular Cell Biology 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blazquez, A. C. , Berenstein, A. J., Torres, C., Izquierdo, A., Lezama, C., Moscatelli, G., De Matteo, E. N., Lorenzetti, M. A., & Preciado, M. V. Comprehensive Evolutionary Analysis of Complete Epstein-Barr Virus Genomes from Argentina and Other Geographies. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, R. , Correia, S., Wegner, F., Venturini, C., Palser, A., White, R. E., Kellam, P., Breuer, J., & Farrell, P. J. Essential role of inverted repeat in Epstein-Barr virus IR-1 in B cell transformation; geographical variation of the viral genome. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 2019, 374, 20180299. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol, J. A. , Brand, J., Ohashi, M., Eichelberg, M. R., Casco, A., Nelson, S. E., Hayes, M., Romero-Masters, J. C., Baiu, D. C., Gumperz, J. E., Johannsen, E. C., Dinh, H. Q., & Kenney, S. C. Reduced IRF4 expression promotes lytic phenotype in Type 2 EBV-infected B cells. PLoS Pathogens 2022, 18, e1010453. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol, J. A. , Djavadian, R., Albright, E. R., Coleman, C. B., Ohashi, M., Hayes, M., Romero-Masters, J. C., Barlow, E. A., Farrell, P. J., Rochford, R., Kalejta, R. F., Johannsen, E. C., & Kenney, S. C. A cancer-associated Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter variant enhances lytic infection. PLoS Pathogens 2018, 14, e1007179. [Google Scholar]

- Chabay, P. A. , & Preciado, M. V. EBV primary infection in childhood and its relation to B-cell lymphoma development: a mini-review from a developing region. International Journal of Cancer. Journal International Du Cancer 2013, 133, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chabay, P. , Lens, D., Hassan, R., Rodríguez Pinilla, S. M., Valvert Gamboa, F., Rivera, I., Huamán Garaicoa, F., Ranuncolo, S. M., Barrionuevo, C., Morales Sánchez, A., Scholl, V., De Matteo, E., Preciado, M. V., & Fuentes-Pananá, E. M. Lymphotropic Viruses EBV, KSHV and HTLV in Latin America: Epidemiology and Associated Malignancies. A Literature-Based Study by the RIAL-CYTED. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. , Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cingolani, P. , Platts, A., Wang, L. L., Coon, M., Nguyen, T., Wang, L., Land, S. J., Lu, X., & Ruden, D. M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. I. Epstein-barr virus vaccines. Clinical & Translational Immunology 2015, 4, e32. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, R. M. , Fellner, M. D., Alonio, L. V., Durand, K., Teyssié, A. R., & Picconi, M. A. Epstein-barr virus (EBV) in healthy carriers: Distribution of genotypes and 30 bp deletion in latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) oncogene. Journal of Medical Virology 2004, 73, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correia, S. , Bridges, R., Wegner, F., Venturini, C., Palser, A., Middeldorp, J. M., Cohen, J. I., Lorenzetti, M. A., Bassano, I., White, R. E., Kellam, P., Breuer, J., & Farrell, P. J. Sequence Variation of Epstein-Barr Virus: Viral Types, Geography, Codon Usage, and Diseases. Journal of Virology 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S. , Palser, A., Elgueta Karstegl, C., Middeldorp, J. M., Ramayanti, O., Cohen, J. I., Hildesheim, A., Fellner, M. D., Wiels, J., White, R. E., Kellam, P., & Farrell, P. J. Natural Variation of Epstein-Barr Virus Genes, Proteins, and Primary MicroRNA. Journal of Virology 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P. , Auton, A., Abecasis, G., Albers, C. A., Banks, E., DePristo, M. A., Handsaker, R. E., Lunter, G., Marth, G. T., Sherry, S. T., McVean, G., Durbin, R., & 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, P. J. , & White, R. E. Do Epstein-Barr Virus Mutations and Natural Genome Sequence Variations Contribute to Disease? Biomolecules 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M. I. , Ibrahim, M. M., Dale, J. K., Greiner, T. C., Straus, S. E., & Bhatia, K. Discrete alterations in the BZLF1 promoter in tumor and non-tumor-associated Epstein-Barr virus. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2002, 94, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hong, J. , Wei, D., Wu, Q., Zhong, L., Chen, K., Huang, Y., Zhang, W., Chen, J., Xia, N., Zhang, X., & Chen, Y. Antibody Generation and Immunogenicity Analysis of EBV gp42 N-Terminal Region. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. L. , & Glaser, S. L. Epstein-barr virus-associated malignancies: epidemiologic patterns and etiologic implications. Critical Reviews in Oncology/hematology 2000, 34, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, K. F. , Chan, T. F., Yang, W., Shen, J. J., Lam, K. P., Kwok, H., Sham, P. C., Tsao, S. W., Kwong, D. L., Lung, M. L., & Chiang, A. K. S. High risk Epstein-Barr virus variants characterized by distinct polymorphisms in the EBER locus are strongly associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer 2019, 144, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jean-Pierre, V. , Lupo, J., Buisson, M., Morand, P., & Germi, R. Main Targets of Interest for the Development of a Prophylactic or Therapeutic Epstein-Barr Virus Vaccine. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 701611. [Google Scholar]

- Jombart, T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K. , & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar]

- Kaymaz, Y. , Oduor, C. I., Aydemir, O., Luftig, M. A., Otieno, J. A., Ong’echa, J. M., Bailey, J. A., & Moormann, A. M. Epstein-Barr Virus Genomes Reveal Population Structure and Type 1 Association with Endemic Burkitt Lymphoma. Journal of Virology 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, B. J. , & Grünwald, N. J. vcfr: a package to manipulate and visualize variant call format data in R. Molecular Ecology Resources 2017, 17, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H. , & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H. , Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., Marth, G., Abecasis, G., Durbin, R., & 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti, M. A. , Gantuz, M., Altcheh, J., De Matteo, E., Chabay, P. A., & Preciado, M. V. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene polymorphisms: malignancy related or geographically distributed variants? Clinical Microbiology and Infection : The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2014, 20, O861–O869. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti, M. A. , Gutiérrez, M. I., Altcheh, J., Moscatelli, G., Moroni, S., Chabay, P. A., & Preciado, M. V. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene promoter variants in pediatric patients with acute infectious mononucleosis: its comparison with pediatric lymphomas. Journal of Medical Virology 2009, 81, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, B. , Liu, M., Chao, Y., Wang, Y., Jing, Y., & Sun, Z. Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus gp350/220 gene variants in virus isolates from gastric carcinoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Archives of Virology 2012, 157, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, B. , Tang, X., Jia, Y., Wang, Y., Chao, Y., & Zhao, C. Sequence variation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BZLF1 gene in EBV-associated gastric carcinomas and nasopharyngeal carcinomas in Northern China. Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur 2011, 13, 776–782. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. P. , Murrell, B., Golden, M., Khoosal, A., & Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evolution 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McKenna, A. , Hanna, M., Banks, E., Sivachenko, A., Cibulskis, K., Kernytsky, A., Garimella, K., Altshuler, D., Gabriel, S., Daly, M., & DePristo, M. A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, T. A. F. , Costa, I. B., Costa, I. B., Corrêa, T. L. D. S., Coelho, B. M. R., Silva, A. E. S., Ramos, F. L. de P., Filho, A. J. M., Monteiro, J. L. F., Siqueira, J. A. M., Gabbay, Y. B., & Sousa, R. C. M. Genotypes of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV1/EBV2) in individuals with infectious mononucleosis in the metropolitan area of Belém, Brazil, between 2005 and 2016. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases 2020, 24, 322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, M. , Marinho-Dias, J., Ribeiro, J., & Sousa, H. Epstein-Barr virus strains and variations: Geographic or disease-specific variants? Journal of Medical Virology 2017, 89, 373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.-T. , Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Palser, A. L. , Grayson, N. E., White, R. E., Corton, C., Correia, S., Ba Abdullah, M. M., Watson, S. J., Cotten, M., Arrand, J. R., Murray, P. G., Allday, M. J., Rickinson, A. B., Young, L. S., Farrell, P. J., & Kellam, P. Genome diversity of Epstein-Barr virus from multiple tumor types and normal infection. Journal of Virology 2015, 89, 5222–5237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, A. R. , & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. The R Reference Manual: Base Package. Network Theory.

- Reyes, M. E. , Zanella, L., Riquelme, I., Buchegger, K., Mora-Lagos, B., Guzmán, P., García, P., Roa, J. C., Ili, C. G., & Brebi, P. (2023). Exploring the Genetic Diversity of Epstein-Barr Virus among Patients with Gastric Cancer in Southern Chile. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, A. B. , Young, L. S., & Rowe, M. Influence of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA 2 on the growth phenotype of virus-transformed B cells. Journal of Virology 1987, 61, 1310–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Masters, J. C. , Huebner, S. M., Ohashi, M., Bristol, J. A., Benner, B. E., Barlow, E. A., Turk, G. L., Nelson, S. E., Baiu, D. C., Van Sciver, N., Ranheim, E. A., Gumperz, J., Sherer, N. M., Farrell, P. J., Johannsen, E. C., & Kenney, S. C. B cells infected with Type 2 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) have increased NFATc1/NFATc2 activity and enhanced lytic gene expression in comparison to Type 1 EBV infection. PLoS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008365. [Google Scholar]

- Sample, J. , Young, L., Martin, B., Chatman, T., Kieff, E., Rickinson, A., & Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr virus types 1 and 2 differ in their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C genes. Journal of Virology 1990, 64, 4084–4092. [Google Scholar]

- Sathiyamoorthy, K. , Hu, Y. X., Möhl, B. S., Chen, J., Longnecker, R., & Jardetzky, T. S. Structural basis for Epstein-Barr virus host cell tropism mediated by gp42 and gHgL entry glycoproteins. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 13557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmieder, R. , & Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 863–864. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, E. M. , Hoppenbrouwers, K., Vandermeulen, C., Moutschen, M., Léonard, P., Moreels, A., Haumont, M., Bollen, A., Smets, F., & Denis, M. Recombinant gp350 vaccine for infectious mononucleosis: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of an Epstein-Barr virus vaccine in healthy young adults. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2007, 196, 1749–1753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tzellos, S. , Correia, P. B., Karstegl, C. E., Cancian, L., Cano-Flanagan, J., McClellan, M. J., West, M. J., & Farrell, P. J. A single amino acid in EBNA-2 determines superior B lymphoblastoid cell line growth maintenance by Epstein-Barr virus type 1 EBNA-2. Journal of Virology 2014, 88, 8743–8753. [Google Scholar]

- Tzellos, S. , & Farrell, P. J. Epstein-barr virus sequence variation-biology and disease. Pathogens 2012, 1, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tzellos, T. , Kyrgidis, A., Mocellin, S., Chan, A.-W., Pilati, P., & Apalla, Z. Interventions for melanoma in situ, including lentigo maligna. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, 2014, CD010308. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, B. J. H. , Schaal, D. L., Nkadi, E. H., & Scott, R. S. EBV Association with Lymphomas and Carcinomas in the Oral Compartment. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E. R. , Alter, G., Ogembo, J. G., Henderson, J. L., Tabak, B., Bakiş, Y., Somasundaran, M., Garber, M., Selin, L., & Luzuriaga, K. High Epstein-Barr Virus Load and Genomic Diversity Are Associated with Generation of gp350-Specific Neutralizing Antibodies following Acute Infectious Mononucleosis. Journal of Virology 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. , & Robertson, E. S. Epstein-Barr Virus History and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Summary of the bioinformatic pipeline used for the construction of multi-sample.vcf files.

Figure 1.

Summary of the bioinformatic pipeline used for the construction of multi-sample.vcf files.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis. (a) Distribution of viral genomes based on PC1 (20.23%) and PC2 (14.32%); EBV1 (orange), EBV2 (green), and viral-type recombinants (R), in light blue. (b) Dots represent the 4.541 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (c) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.95]. Most relevant genes are represented below, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis. (a) Distribution of viral genomes based on PC1 (20.23%) and PC2 (14.32%); EBV1 (orange), EBV2 (green), and viral-type recombinants (R), in light blue. (b) Dots represent the 4.541 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (c) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.95]. Most relevant genes are represented below, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

Figure 3.

Viral type variability. (a) Africa, (b) Southeast Asia and (c) South America. Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) AFR = 4.78; -Log10(p value) SEA = 4.73 and -Log10(p value) SAM = 4.75]. Most relevant genes are represented below, according to their position in the genome. Orange boxes above the graph delimited the 3 most informative blocks in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

Figure 3.

Viral type variability. (a) Africa, (b) Southeast Asia and (c) South America. Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of EBV1 and EBV2 using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) AFR = 4.78; -Log10(p value) SEA = 4.73 and -Log10(p value) SAM = 4.75]. Most relevant genes are represented below, according to their position in the genome. Orange boxes above the graph delimited the 3 most informative blocks in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

Figure 4.

Principal Component Analysis. Distribution of genomes in relation to the geographic origin of the isolates. (a) EBV1 and (b) EBV2.

Figure 4.

Principal Component Analysis. Distribution of genomes in relation to the geographic origin of the isolates. (a) EBV1 and (b) EBV2.

Figure 5.

Genomic variability of EBV1 and EBV2 in relation to geographic origin. (a) Quantification of the number of variants in isolates from different geographic regions relative to each reference genome. Boxes represent the interquartile range, the inner line of the box indicates the median value for each group, the whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum values. (b) Distribution of common variants by geography along the EBV1 reference genome (NC_007605.1). (c) Distribution of common variants by geography along the EBV2 reference genome (NC_009334.1). Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions.

Figure 5.

Genomic variability of EBV1 and EBV2 in relation to geographic origin. (a) Quantification of the number of variants in isolates from different geographic regions relative to each reference genome. Boxes represent the interquartile range, the inner line of the box indicates the median value for each group, the whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum values. (b) Distribution of common variants by geography along the EBV1 reference genome (NC_007605.1). (c) Distribution of common variants by geography along the EBV2 reference genome (NC_009334.1). Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions.

Figure 6.

Variability Study. (a) Dots represent the 3,666 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA, SAS, and OCE with EUR, AFR, AUS, NAM, and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (b) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA, SAS, and OCE with EUR, AFR, AUS, NAM, and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.86]. Orange boxes above the graph represent the 4 most informative coding regions in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome. (c) Dots represent the 3,276 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA and OCE with AFR and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (d) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA and OCE with AFR and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.74]. Orange boxes above the graph represent the 4 most informative coding regions in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

Figure 6.

Variability Study. (a) Dots represent the 3,666 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA, SAS, and OCE with EUR, AFR, AUS, NAM, and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (b) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA, SAS, and OCE with EUR, AFR, AUS, NAM, and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.86]. Orange boxes above the graph represent the 4 most informative coding regions in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome. (c) Dots represent the 3,276 variable positions; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values as obtained by comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA and OCE with AFR and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction. (d) Distribution of identified variants along the genome based on the -Log10(p value) when comparing the allelic frequencies of SEA and OCE with AFR and SAM using Fisher's exact test and subsequent Bonferroni correction; orange dots represent statistically significant values and gray dots non-statistically significant values. Black dotted line represents the threshold value above which the p values are considered significant [-Log10(p value) = 4.74]. Orange boxes above the graph represent the 4 most informative coding regions in terms of variable positions. Most relevant viral genes are represented as coral boxes below the graph, according to their position in the genome. Gray boxes represent the repetitive regions of the viral genome.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).