1. Introduction

Aristotle, 350 BC, described language as sound with meaning (Chomsky, 2013). This idea was widely accepted. Noam Chomsky, however, proposes a modified version as meaning with sound (Chomsky, 2013). However, neither approach gives a complete picture of language. Language not only conveys meaning, but also has the power to influence the mind and reality. Little attention has been paid to this aspect of language. As the saying goes, “Do nothing that is not within your ability” (Randy, 1993, p.4). For thousands of years, linguistic research focused mainly on phonology, lexical semantics, grammar, and syntax. It was not until the turn of the 20th century that there was notable progress in higher-order areas such as structural semantics. The study of sentence meaning is a multifaceted field of linguistics. However, the concept of meaning presents several challenges. Each word in a sentence contains a wealth of information that is influenced by numerous factors. In addition, the overall meaning is shaped by grammatical structure and syntax. To date, there has been no universally applicable theory of language or meaning.

As stated in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Speaks, Jeff, 2024), a theory of meaning is expected to provide answers to the following two fundamental questions.

i) What is the semantic meaning of a particular symbol of language?

ii) On the basis of what facts does the symbol have that meaning?

For over a century, the search has been on for a theory that provides a combined answer to the two fundamental questions mentioned above. A major drawback common to almost all theories of meaning is that they view language as a characterization of the mind or some kind of organ in the mind. When a language describes the world, it is interpreted as a way in which the mind sees the world in that way. However, this was not the case.

Furthermore, there are many other considerations that need to be taken into account in relation to language in order to develop a universally applicable theory.

It is obvious that humans are capable of producing speech that requires the use of a variety of information carried by language symbols that are combined in a particular pattern and governed by grammatical rules. Seeing children acquire the ability to use language, at least in its basic form, without specialized instruction, arouses curiosity about the fundamental nature of language.

Language is crucial to human life. Therefore, beyond curiosity, there is an urgent need to unlock the secrets of language. The effectiveness and efficiency of learning a second language depends on this important task. Multilingualism is the norm for surviving in a multitude of societies.

More than 6000 languages exist worldwide. Comparative language studies suggest that, in principle, all languages have a common deep structure, even if they appear different on the surface (Randy, 1993, p.14). The basic knowledge of a particular language is the same for all its speakers. This observation, combined with the ability of any individual to potentially acquire multiple languages, suggests that the fundamental nature of language is universal across humanity.

This essay presents a triadic law that links thought, language and reality and provides a comprehensive solution that takes into account all facets of language. It also proposes a universal linguistic framework derived from this principle that captures the essential features of all languages.

This paper examines important linguistic issues, including communication skills, universality of language, complicated syntactic structures, and the acquisition of primary and secondary languages. The analysis uses the law of the trio principle and a universal language model derived from this law.

2. The Law of the Trio: Unity of Thought, Language and Reality

Thought, language and reality are identical in content and structure, but differ in form like the phases of matter or some other systems in the world that exist in two or more forms.

Depending on pressure and temperature, for example, water exists in three phases: solid, liquid and gas. This also applies to other substances. The phases are the same in their constituent molecule, but have different properties and can co-exist under certain conditions. In addition, the transformation from one phase to another is possible through processes such as boiling, condensation, freezing, melting and sublimation.

Our telecommunication system is another typical example in which voice exists in different forms: analog, digital, electromagnetic or as light pulses. When a call is made from a cell phone, voice, an analog signal, is converted to digital pulses and transmitted as electromagnetic signal and light pulses to ensure transmission over long distances without loss of data or information, but then converted back to its analog form at the other end to match our perception of sound.

As in the examples above: Language, thought, and reality are the three forms of existence of entities or systems and their corresponding characteristics or behaviors and relationships between entities in the form of sentence, mental image and physical reality respectively.

Mathematically Speaking,

Language, Thought or Reality = f (Entity/System, Status (or Behavior))

Eq.1. The Universal Model of Language, Thought or Reality.

The state of an entity or system effectively describes its characteristics or appearance. Changes in this state occur through internal or external mechanisms, referred to as behaviors. As expressed in eq.1, the fundamental nature of reality, thought, and language comprises the entity, its state, and the processes that alter its state.

Linguistic expression employs sentence construction to depict entities, their states, and the behaviors that modify these states. Thoughts manifest as mental representations of entities, their states, or behaviors. Reality consists of physically observed or perceived entities, their states, and their behaviors.

Given that thought, language, and reality are fundamentally similar, they exert mutual influence and possess equal power to shape one another. For instance, a spoken word can induce changes in one’s mind or in reality. Consider a child whose mother tells him he will become the 7th king of his country when he grows up. This child may adapt his mindset to embody royal qualities in his future life, creating an environment through his behavior, actions, and interpersonal relationships that reflects the attributes of a king, ranging from elegance to wisdom.

3. Communication Skills: Speaking/Writing and Listening/Reading

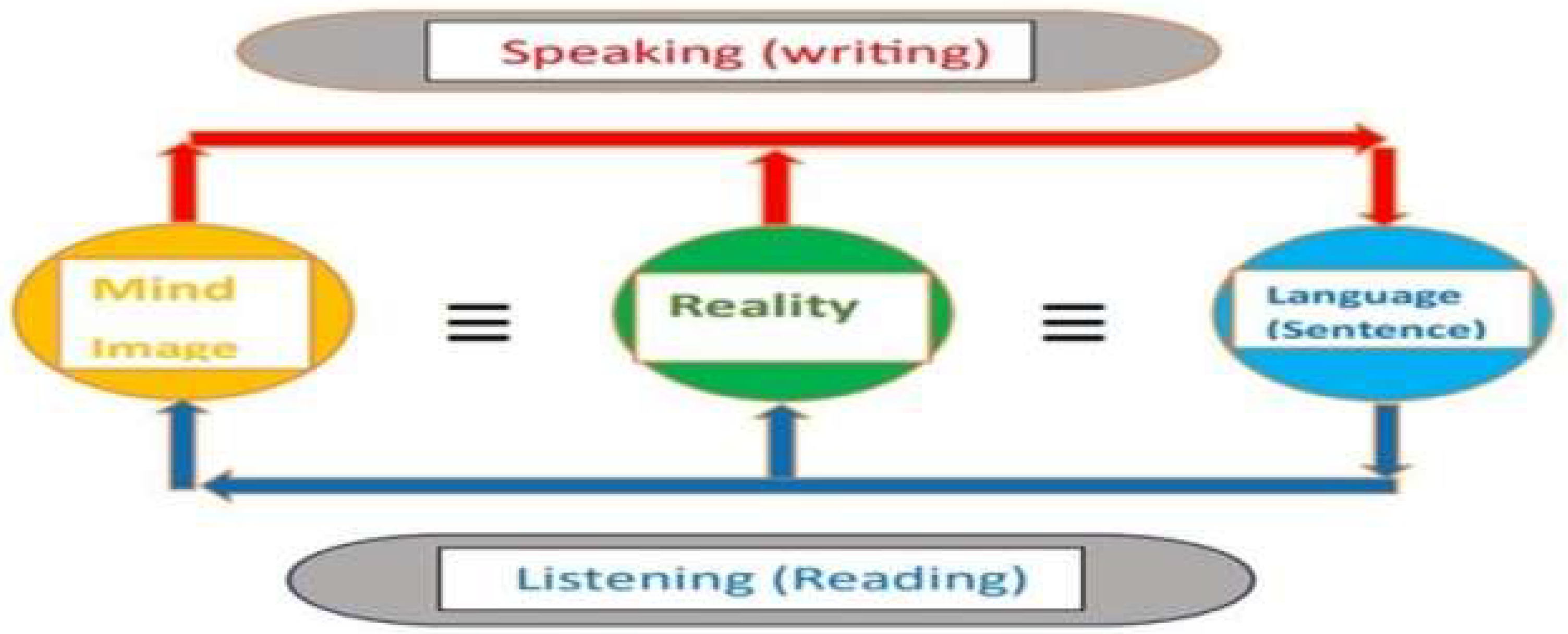

The transformation of mental imagery, real-world experiences, or a blend of both into linguistic forms, and vice versa, constitutes the essence of communication through speaking, writing, listening, and reading. Cognitive constructs and ideas are arranged as mental representations, reflecting the organization of actual reality. In these mental or physical realms, an entity occupies a particular condition, performs a specific action, within a defined temporal and spatial context. This fundamental structure typically finds expression through a single sentence in any given language system. This is demonstrated in

Figure 1 below.

4. Universality and Variation of Languages

Are the 6000 to 7000 spoken languages that exist today completely different, or are there similarities between them?

The law of a trio of world reality, thought (or metal image) and natural language justifies that all languages are essentially one and the same to each other. All languages represent reality, thought (or mental image), or combination of reality and thought in the form of a sentence. The differences between languages lie on the words, grammatical rules and syntax that speakers use to express the reality of the world they experience and the thoughts they have developed to transform reality.

The human sensory organs convert physical signals from the environment into electrical signals and transmit the electrical signals to the central nervous system for processing. The mind creates mental images of entities characterized by their corresponding properties or behaviors, which we refer to as perception when the input data comes from the sensory organs. As experience increases, the mind accumulates information categorized by entities associated with characteristics or behaviors and the entity’s relationship to other entities. Classes of sub-entities and sub-sub-entities may also develop hierarchically from top to bottom as more and more detailed information is acquired through growing experience with a particular entity.

The fields of information extend in all directions, connecting one entity to other entities as a particular entity interacts with other entities in different circumstances, becoming more and more acquainted. In this way, the mind develops knowledge about the entities as mental images of interconnected entities enriched by their corresponding properties. The perceived realities are mental images of the experienced realities.

Driven by innate desires or under the influence of external factors, the mind forms thoughts by processing information from various sources and forming modified or newly created mental images. The newly developed thought is capable of reshaping physical realities when conditions are favorable for the physical implementation of the thought. Achieving goals that go too far or solving complex problems require complex cognitive processes that take place in the mind. In simple or complex thoughts, the coupling of entities and their behavior are the building blocks of the network of mental images, just as physical reality is formed by the sensory organs.

In the realm of language, the connection between an entity and its characteristic or behavior is represented by a sentence. This is the characteristic feature of all languages. A sentence is basically a coupling of an entity with its feature or behavior, which is the basis of our thinking and the way we shape the physical world. So, the difference between languages lies in the formation of a sentence. They use different word encodings for the entities and their features or behaviors, introduce different grammatical rules and syntax structures. However, all languages contain the same information as in the mind and in the physical world.

While it is true that speakers of a particular language have unique life experiences compared to speakers of another language, this in no way distinguishes one language from another. The mental processes that occur in people with different languages are more or less the same.

The next section looks at the formation of sentence structures by applying the law of the trio of reality, thought and language.

5. Syntactic Structure

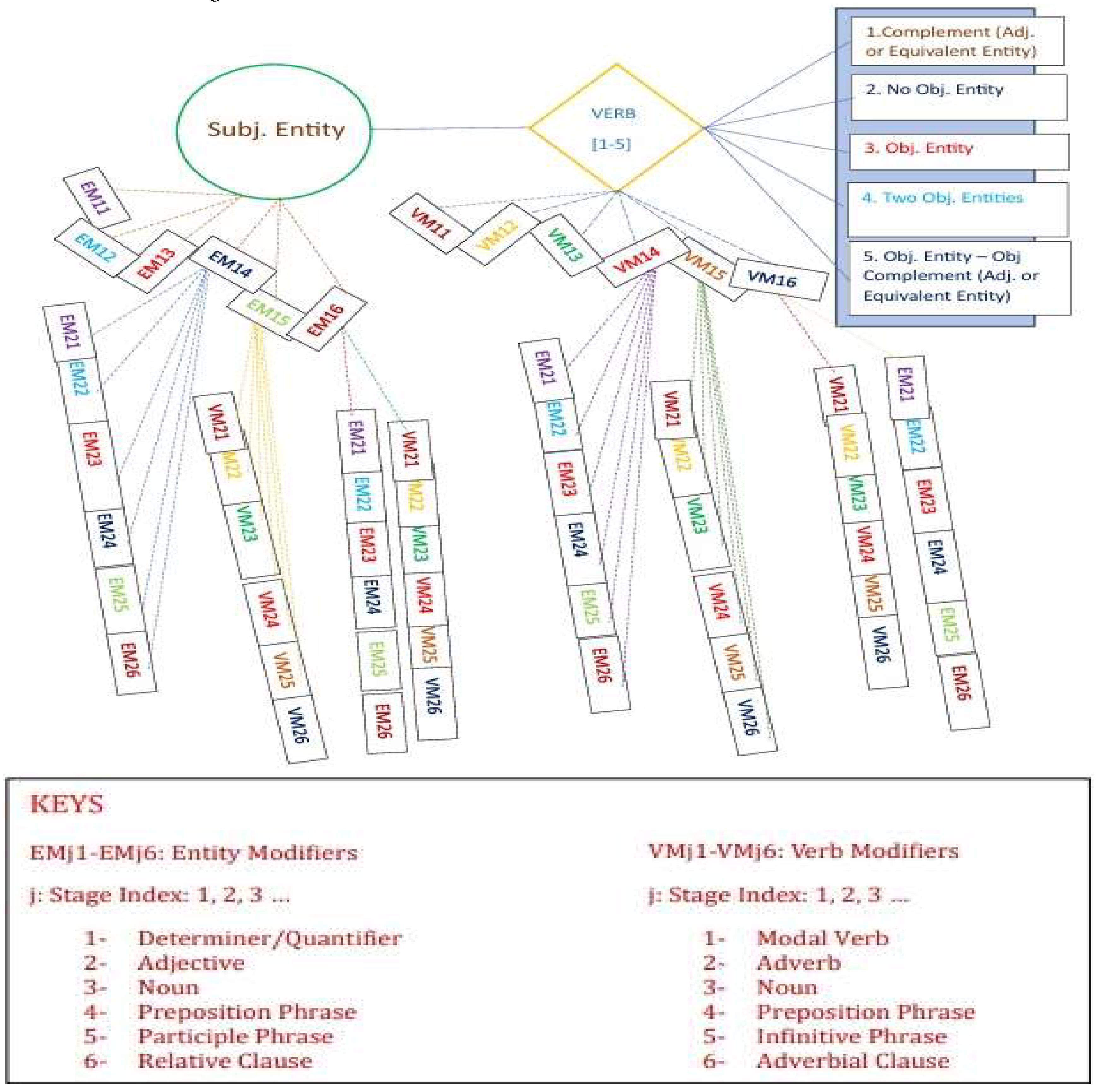

The fundamental structure of information in the physical realm, mental processes, and language is based on relationships between entities and their characteristics or actions. As shown in eq.1 in section 2, the core of a sentence is formed by linking an entity to its attributes or behaviors within an event. Thus, a sentence describes an entity’s condition, action, or interaction with other entities in a cognitive or physical event. In a changing environment, both internal and external factors can alter an entity’s state. External factors involve interactions between entities. Within a sentence, the subject head noun represents the entity in focus, while the predicate expresses its state or activity in relation to other entities. The predicate comprises the head verb and additional elements that correspond to the verb type and related information. Sentence structure may vary across languages. For example, English employs five verb types to depict a subject entity’s status or behavior in an event, while other languages may use fewer or more.

Languages utilize finite methods to express an infinite number of scenarios occurring mentally or physically. This is achieved through the application of grammatical rules. One crucial technique is the use of modifiers within sentences.

Common nouns and verbs are primarily modified by adjectives and adverbs, respectively. These modifiers help nouns and verbs accurately reflect events in one’s mind or in reality. Simple sentences are composed of these four fundamental word classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.

In addition to adjectives and adverbs, sentences employ additional methods to modify nouns and verbs. This process transforms simple sentences into complex ones, allowing for the inclusion of more information about nouns or verbs through words, phrases, or clauses.

In the English language, there are typically six techniques for providing supplementary information about common noun entities:

1. Determiner/quantifier

2. Adjective

3. Noun

4. Prepositional phrase, which modifies a noun by expressing its relationship to another noun using a preposition.

5. Participle phrase, which modifies a noun by describing the action it performs or that is performed on it.

6. A clause, which offers relevant information about the modified entity from another event. Relative pronouns connect the modified noun to the clause modifier.

Similarly, the English language employs six techniques to enhance verbs with additional information. These techniques, known as verb modifiers, include:

1. Modal verb

2. Adverb

3. Noun, primarily indicating the timing of the action or state described by the verb.

4. Prepositional phrase, which provides supplementary information to the modified verb by connecting it to a noun using a preposition that illustrates their relationship.

5. Infinitive phrase, a verb phrase that supplies extra details about the modified verb.

6. Adverbial clause, which offers more information about the modified verb by utilizing a sentence from a related event, facilitated by adverbial conjunctions.

This modification process extends beyond the head noun, head verb, or nouns functioning as complements or objects. Any noun or verb acting as a modifier can be modified in the same way as other nouns or the head verb. This structure creates a hierarchical arrangement within a sentence, allowing for open-ended construction.

In scenarios involving multiple independent entities, the sentence must portray the status or action of each entity, connecting it to its corresponding verb along with associated modifiers. Various languages may use different grammatical rules to describe other aspects such as subject-verb agreement and tense usage.

Figure 2 below demonstrates a two-stage modification sentence. The noun modifiers are denoted by the symbol EMji, where i represents the type of noun modifier as listed above, and j indicates the level of modification, taking values 1, 2, 3, and so on. Similarly, verb modifiers are symbolized as VMji, where i signifies the type of verb modifier as listed above, and j denotes the level of modification, taking values 1, 2, 3, and so forth.

6. Acquisition of 1st Language

The process by which children acquire language without formal instruction is a subject of intense debate. Given the lack of consensus on the fundamental nature of language, various theories exist to explain language-related phenomena. This section does not aim to explore the diverse viewpoints on this topic found in existing literature. Instead, it seeks to elucidate first language acquisition using the concept of the trio relationship between language, thought, and reality.

In young children, the role of thought is less significant. It takes considerable time before thought can substantially impact language or reality. The observed slowdown in language acquisition around ages 7 to 8 indicates the emerging influence of thought on language. Prior to this stage, language and reality interact considerably in children. Contrary to theories suggesting innate language acquisition, both language and reality are absorbed from the environment.

A unique characteristic of children is their immediate understanding of the equivalence between language and reality. They exhibit perfect adaptation to their surroundings, paying equal attention to all occurrences in their environment. For children, language is an ever-present element, available to them from birth.

Children perceive each sound from their caregivers, role models, or others in their environment alongside the concurrent physical activities surrounding them. This encompasses everything from the speaker’s facial expressions to the movements and interactions of bodies nearby. As naturally inquisitive beings, children derive meaning by connecting sounds to real-world states or actions. This process of equating language with reality enables children to acquire various aspects of language, starting with basic elements like learning names of objects and words describing actions or emotions. They then progress to comprehending sentence sequences and eventually combining multiple sequences to express more complex linguistic concepts.

Contrary to the notion presented in (Pinker, 1996), language does not emerge spontaneously as an instinctive behavior. Instead, children gradually acquire language, with all its nuances, from their environment, much like they learn other skills and knowledge.

7. Acquisition of 2nd Language

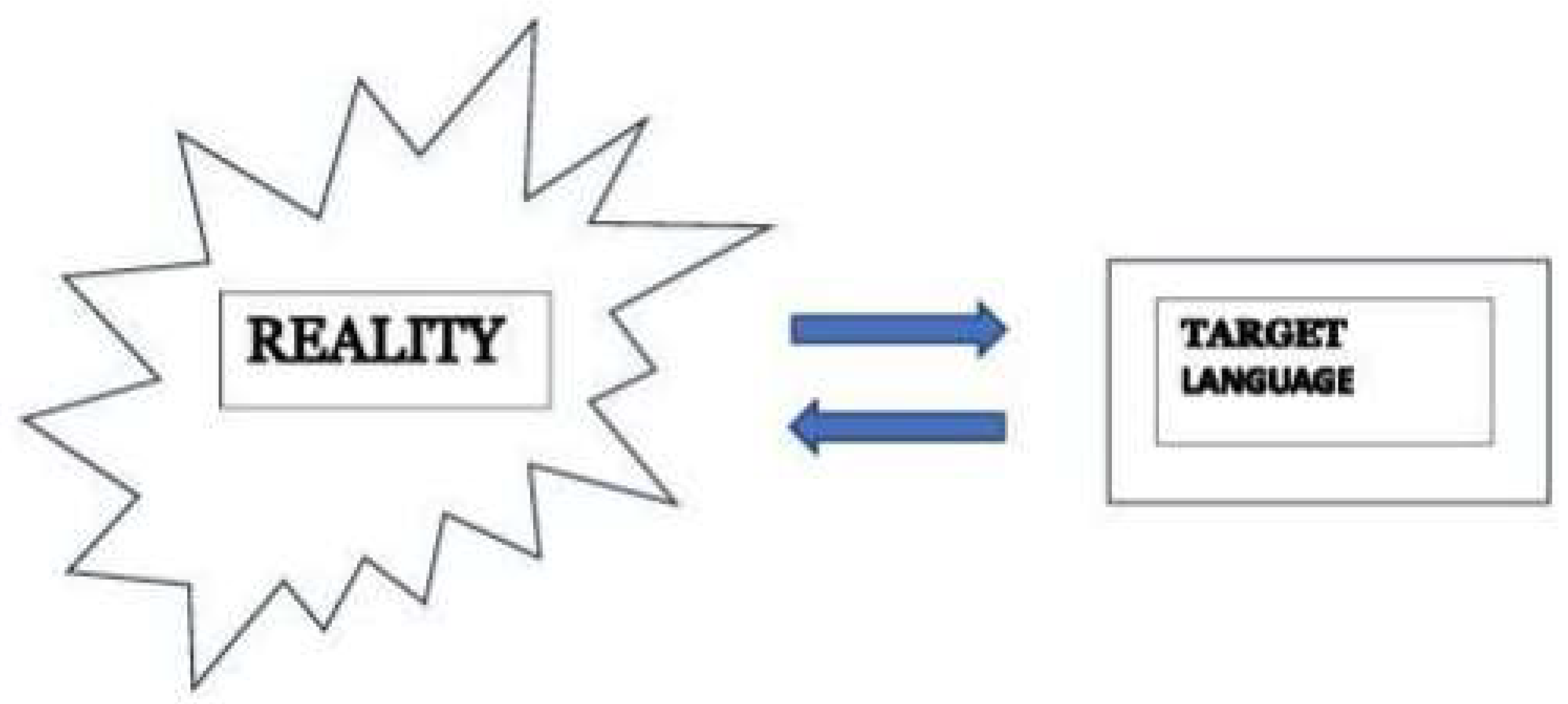

If we look at the technical aspects of second language learning, the learner is faced with the challenge of reconciling thought and reality in the form and structure of the foreign language. As described in the previous sections, his learned language and the target language have in principle the same purpose. Both describe reality and thought with the help of sentence formation.

Any event in reality at a given time and place is effectively expressed by combining the entities involved in the event with their corresponding states or actions. A sentence is basically a symbolic description of the reality or thoughts of a particular entity at a particular time and place. Structurally, reality and thoughts are the same thing. Thoughts can be perceived as mental reality, while reality is the existence outside the mind in the physical environment. The task of a learner of a second language is therefore to study the forms and structures of the target language in order to perform the same task that he performs in his acquired language. Both his acquired language and the target language are two images of reality.

According to the law of the trio, the effective method for learning a second language is to use reality as a reference for learning the target language. This method eliminates the interference of the acquired language in the learning of the target language. See

Figure 3 below.

If reality is a reference, learning the second language will be based on sentences. A sentence is like a bullet that is fired and hits a specific target at a specific time and place in reality. It uses words and grammatical rules and structures of a particular language that are appropriate for the target. Sentence-based learning allows the learner to learn words, grammar rules and structures all in one. However, care must be taken when selecting the realities that the learner knows well at the beginning of the learning phase. New realities contain new knowledge that the learner should understand in his/her acquired language before using the target language. Realities that are out of the learner’s imagination and knowledge should be put aside until the second language learner is familiar with most of the words and structures of the target language.

Language should not be understood as the processing of words in a particular order to produce a holistic meaning. It can be understood as the formation of sentences that reflect reality. For every constructed sentence, there is an event that takes place in reality (mental or physical reality). The meaning that a sentence conveys can therefore be understood in terms of its effects on reality. For example, the sentence “The dog is barking” can talk about the sound of a particular dog. However, this sentence may raise many questions for the listener in the context in which it is uttered or in relation to previous experiences related to the dog barking. Reality refers to the connection between events. When an event occurs, it leads to other events. Therefore, a sentence does not only convey a meaning by arranging a group of words in a certain way. It involves changes in reality that accompany the event mentioned in the sentence. Sentences are transformed into narratives to provide more information about connected events.

As shown in

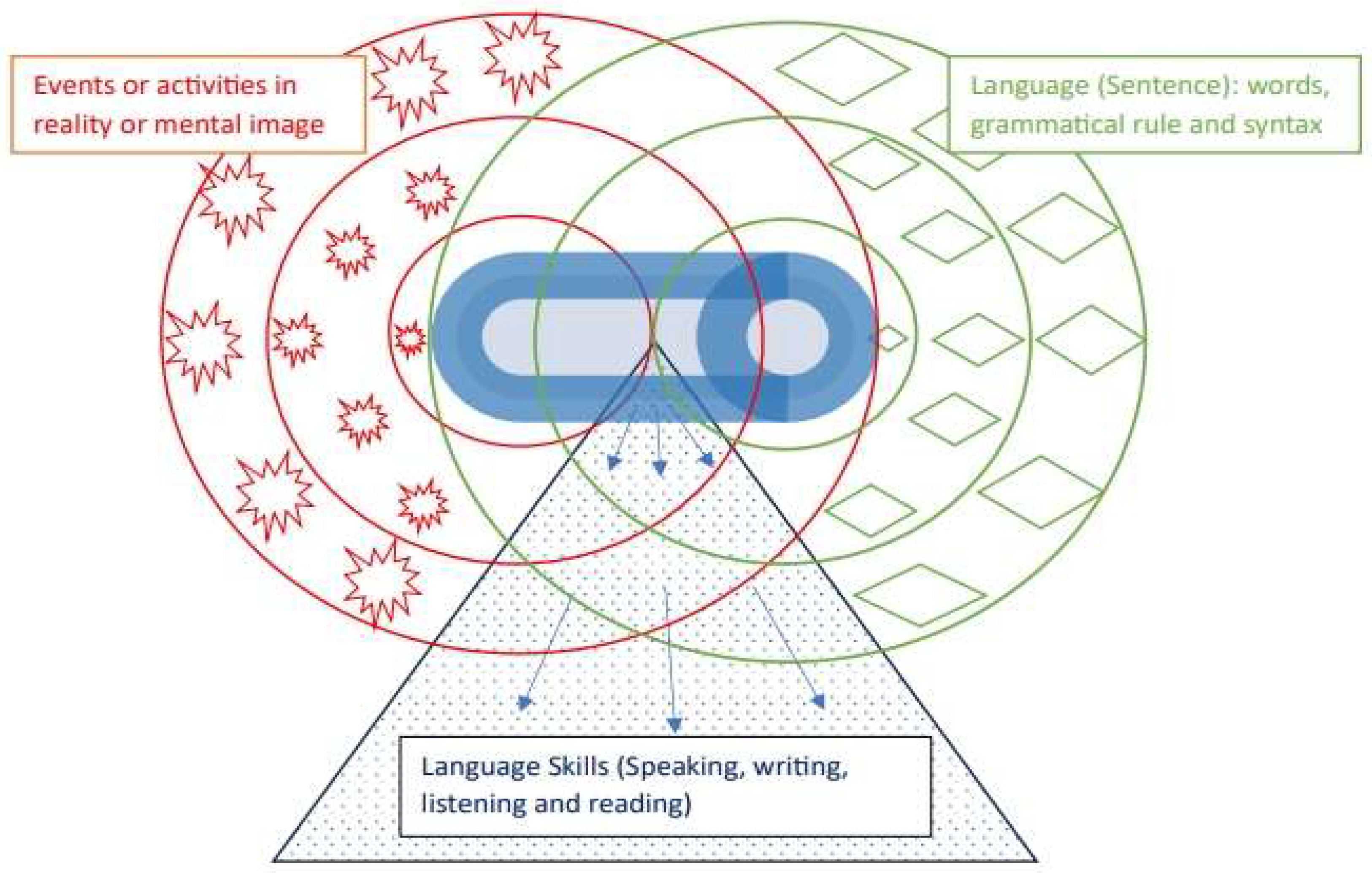

Figure 1, language skills (speaking, writing, listening and reading) are processes of transforming events in physical or mental reality into language in the form of sentences and vice versa. A second language learner learns how to acquire these skills in the target language. For every sentence that is formed, there is a corresponding event in the mental or physical world. Sentences and events are comparable to the two weight plates of a dumbbell. The natural way to learn the words and syntax of a sentence is to look at the event associated with the sentence. This is exactly what happens to a child learning their first language. Words, grammatical rules and syntax are effectively memorized when they are inextricably linked to the event they describe. Our mind is an event and word processing machine. After the events have taken shape, the mind works on the words and syntax that are appropriate to describe the event. These events evoke the corresponding words and syntactic rules.

If we turn the language learning process into word processing, the results will be disastrous. The event processing approach integrates realities and the memorization of the intricacies of language in a sentence with the resulting skill development, as shown in

Figure 4 below.

8. Conclusion

The enigma of language has been deciphered through the revelation of the trio principle, which asserts the unity of language, thought, and reality in substance, despite their distinct manifestations. A comprehensive framework for language, thought, or reality is exemplified by the functional representation of an entity coupled with its characteristics or actions. This principle and framework have successfully addressed crucial linguistic phenomena, including the commonalities among languages, verbal proficiency, syntactic organization, and the processes of primary and secondary language learning. The insights presented in this research elevate linguistic studies to a level comparable with other scientific disciplines, marking a pivotal moment in the field’s development.

9. Declarations

I certify that I’m the sole author of this research article. I have never received any financial assistance for the research from an individual or institution.

I also declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Noam Chomsky. 2013. ’What Is Language and Why Does It Matter.’ Lecture hosted by LSA-University of Michigan. https://youtu.be/-72JNZZBoVw?si=va1uNWqeT87inaK9.

- Randy Allen Harris. 1993. The Linguistics Wars. Oxford University Press.

- Speaks, Jeff, “Theories of Meaning”, The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Winter 2024 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), forthcoming URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/meaning/.

- Steven Pinker. 2007. The Language Instinct. Harper Collins.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).