Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

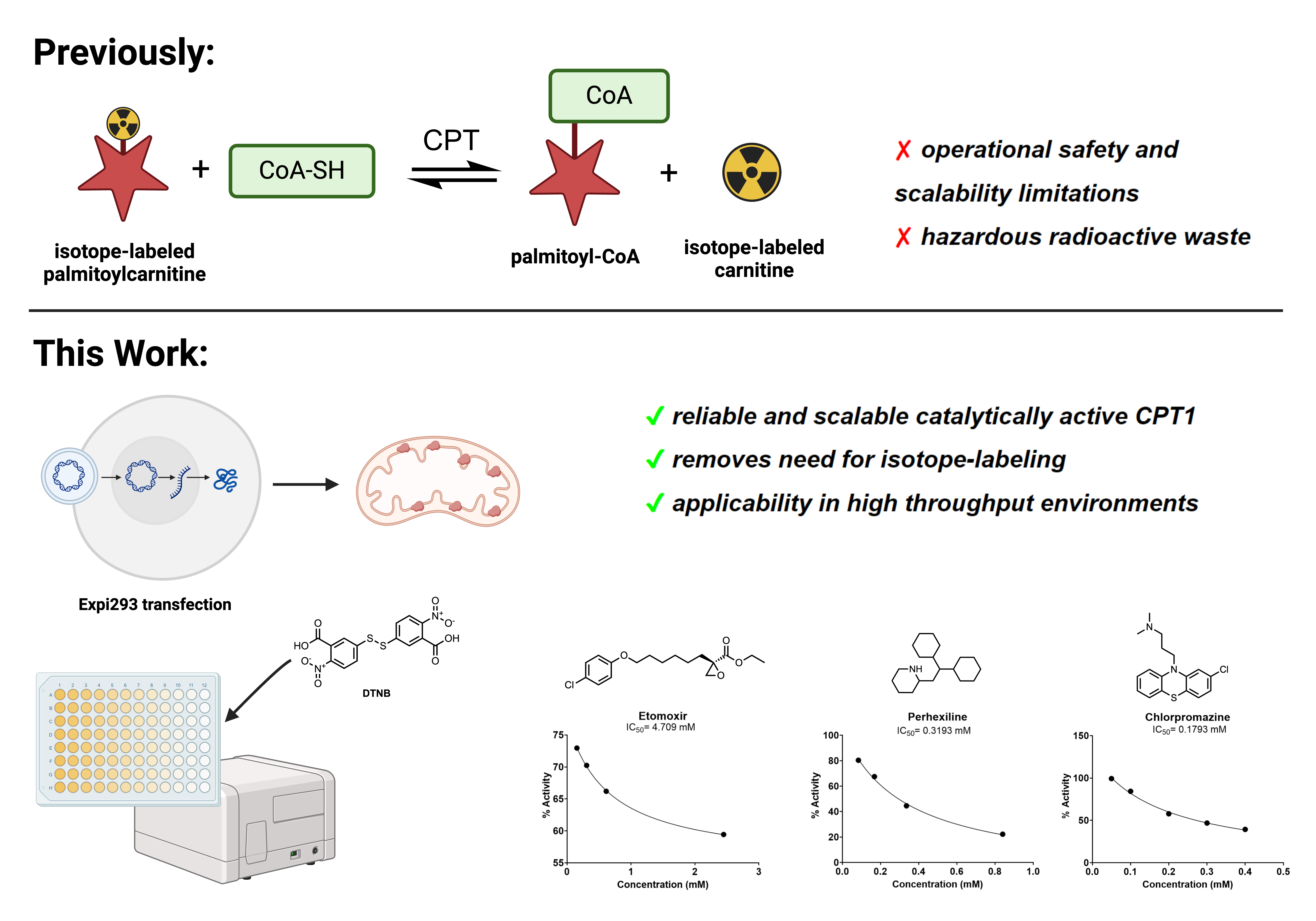

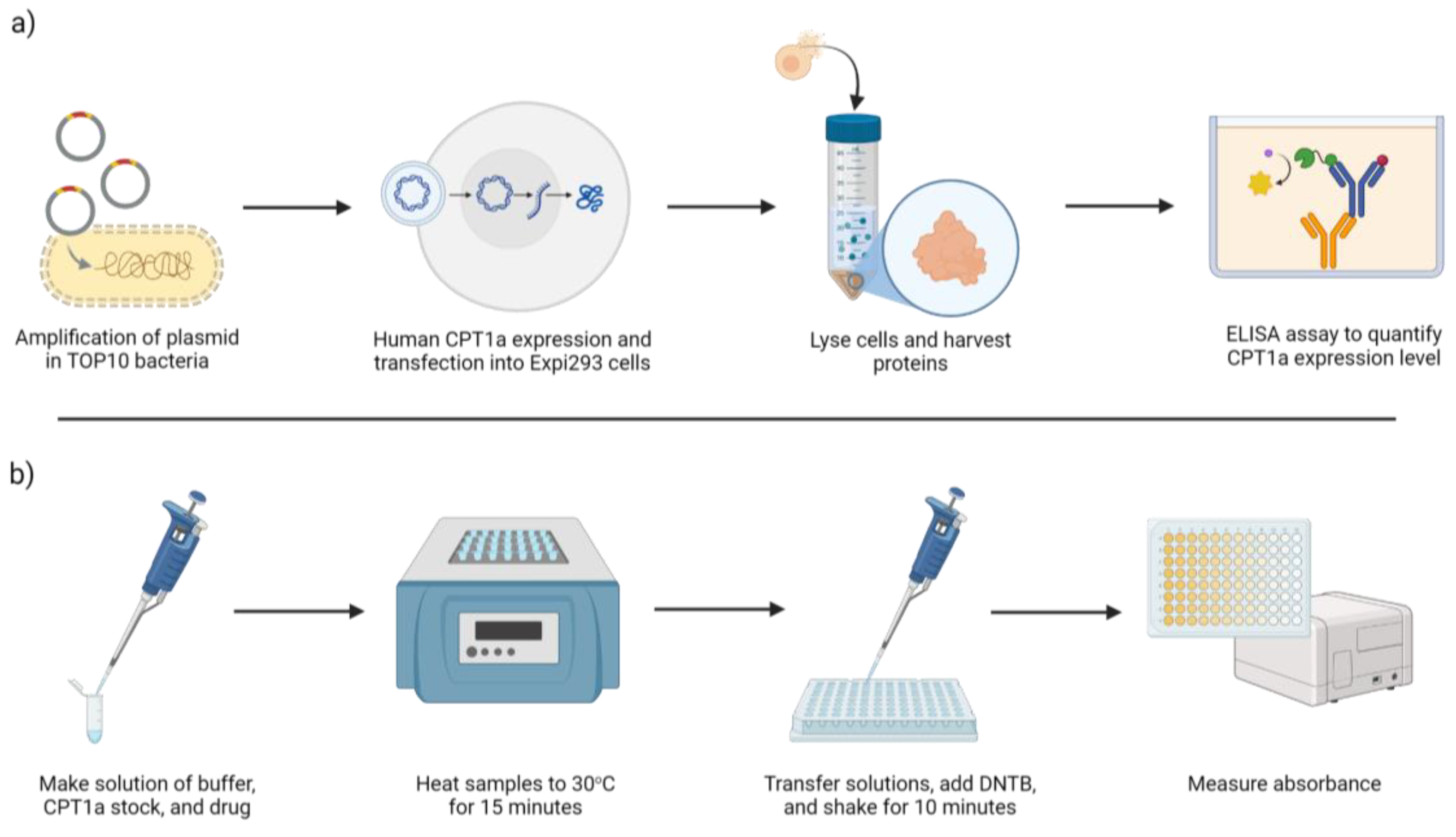

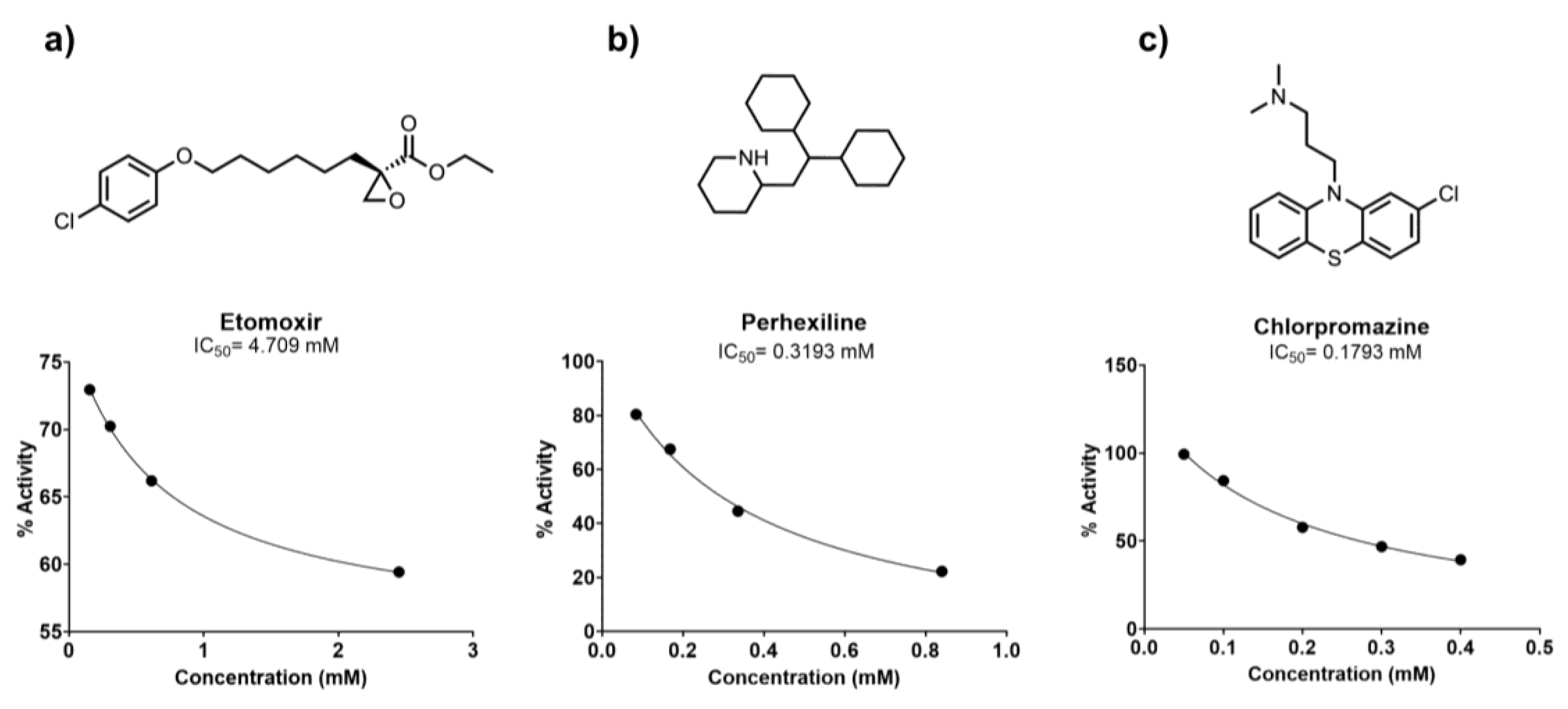

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of fatty acid oxidation, has been implicated in therapeutic approaches to several human diseases characterized by aberrant lipid metabolism. Isoform-specific quantification of CPT1 activity is essential in the characterization of small molecule inhibitors of CPT1, but several existing means to quantify enzymatic activity, including the use of radioisotope labeled carnitine, are not amenable to scalable, high throughput screening. Here, we demonstrate that mitochondrial extracts from Expi293 cells transfected with a CPT1a plasmid are a reliable and robust source of catalytically active human CPT1. Moreover, with a source of catalytically active enzyme in hand, we modified a previously reported colorimetric method of coenzyme A (CoA) easily scalable to a 96-well format for the screening of CPT1a inhibitors. This assay platform was validated by two previously reported inhibitors of CPT1a: R-etomoxir and perhexiline. To further demonstrate the applicability of this method in small molecule screening, we prepared and screened a library of 87 known small molecule APIs, validating the inhibitory effect of chlorpromazine on CPT1.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Human CPT1a Enzyme Expression

Immunoassay to Quantify CPT1a

CPT Enzyme Activity Assay and Inhibitor Sensitivity Assay

High-Throughput Screening of a Small Molecule Library

Data Analysis

3. Results

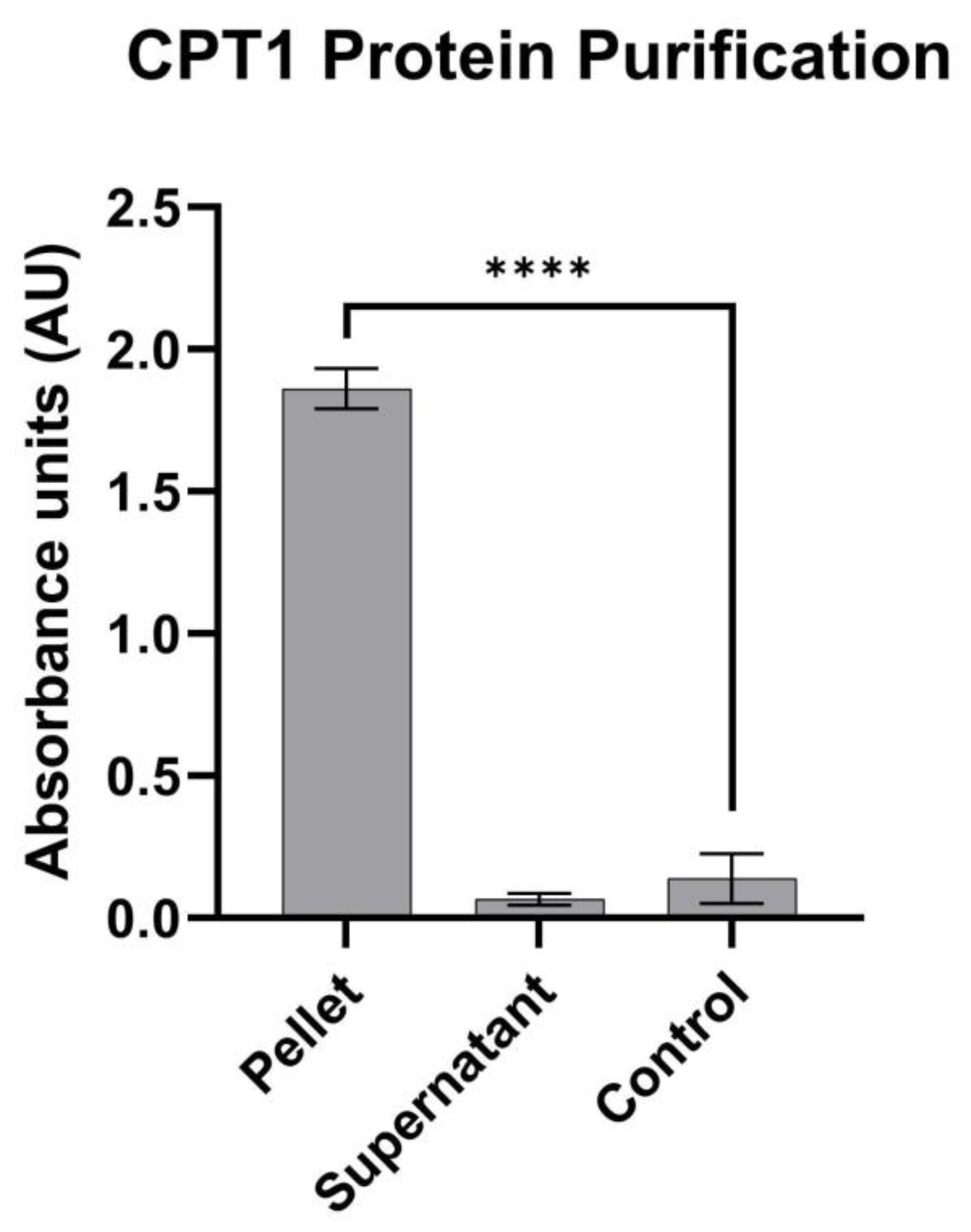

3.1. Human CPT1a Enzyme Expression and Protein Isolation

3.2. CPT1a Immunogenicity Assay

3.3. CPT1 Enzyme Activity Assay Validation

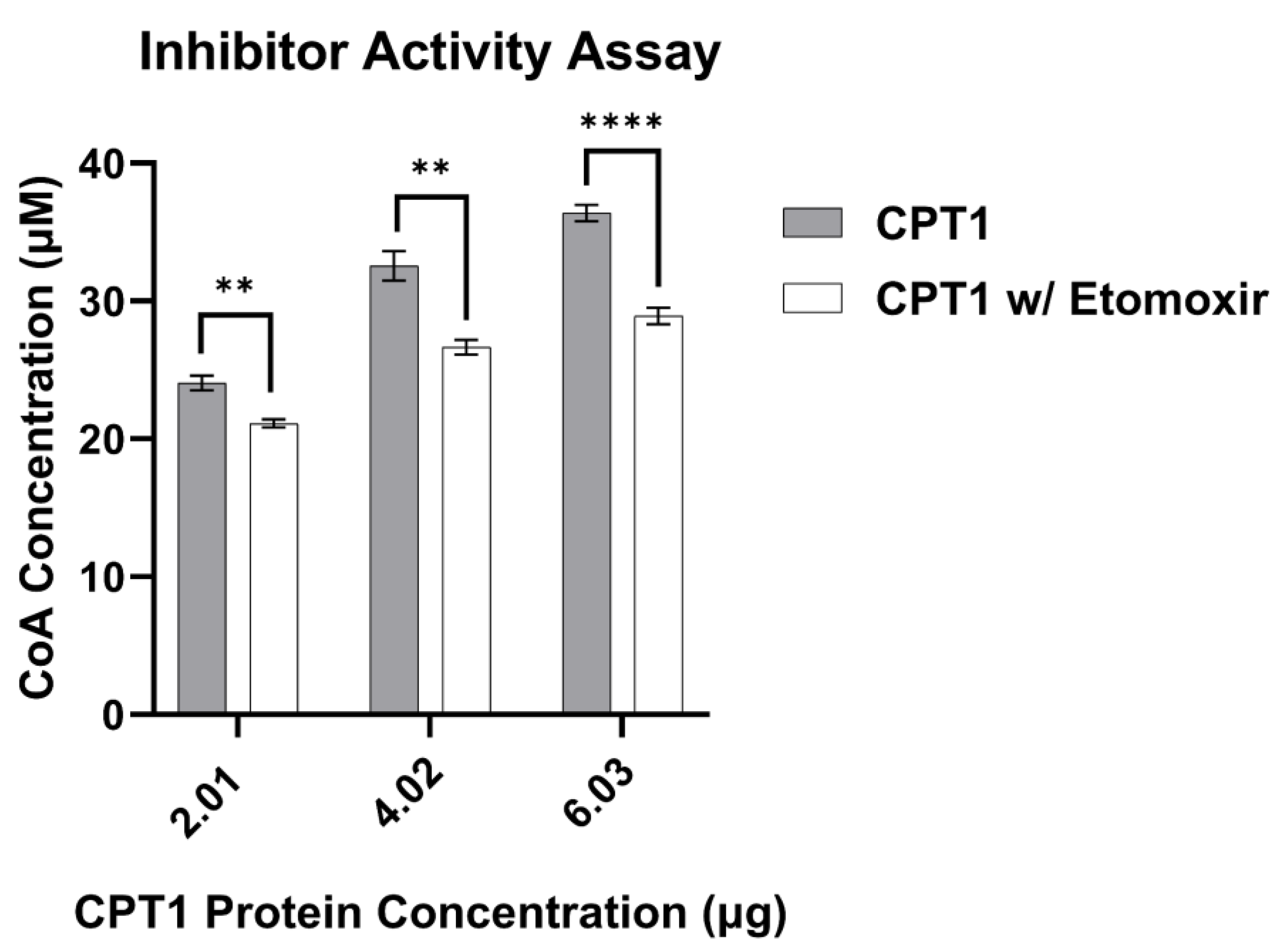

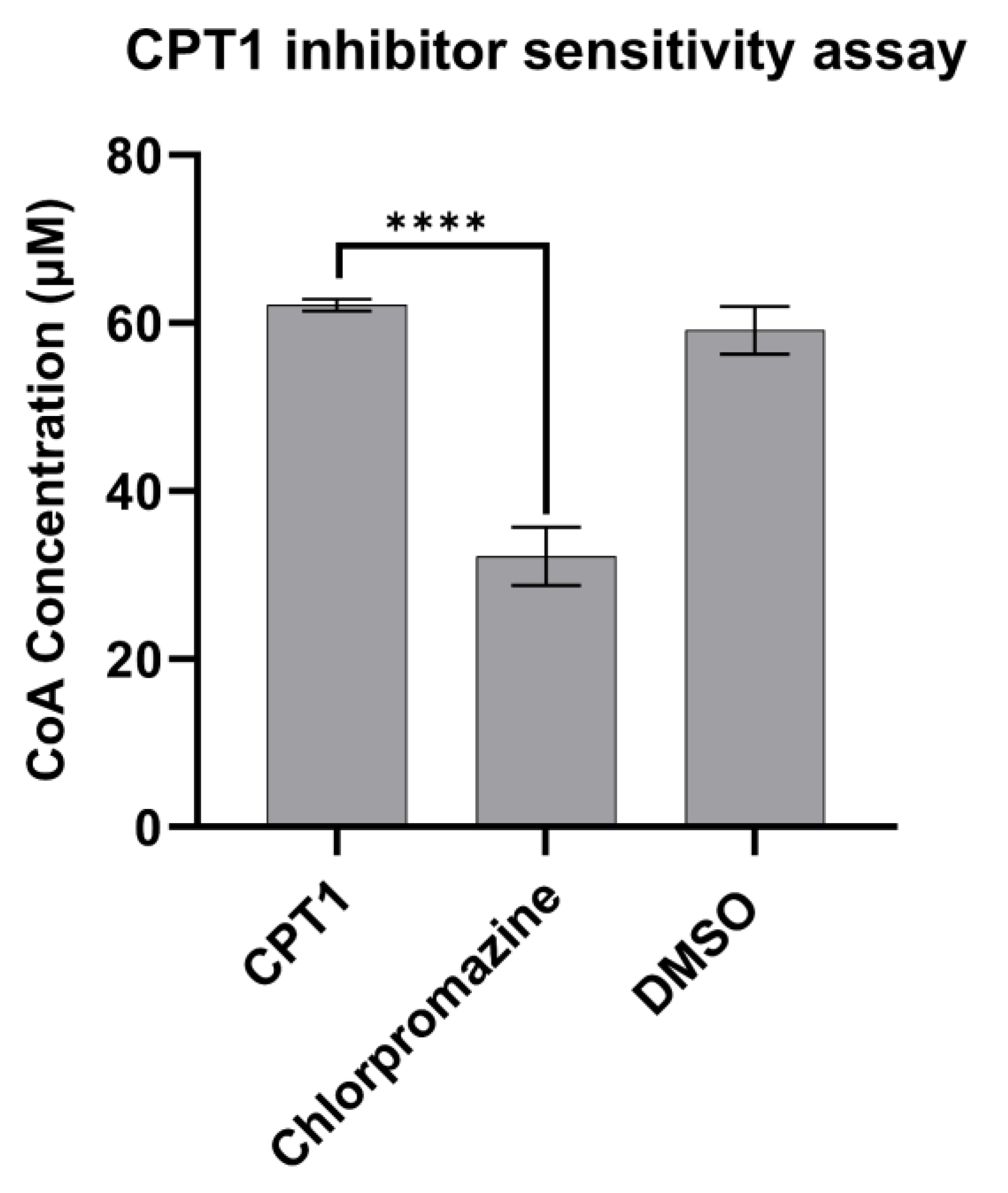

3.4. CPT1 Enzyme Inhibitor Sensitivity Assay

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Temkin, S.M.; Hawkridge, A.M.; Guo, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fang, X. Fatty Acid Oxidation: An Emerging Facet of Metabolic Transformation in Cancer. Cancer Lett 2018, 435, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, H.; Lu, Y.; Wu, T.; Ji, G. The Role and Therapeutic Implication of CPTs in Fatty Acid Oxidation and Cancers Progression. Am J Cancer Res 2021, 11(6), 2477–2494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roden, M.; Bernroider, E. Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in Humans—Its Role in Health and Disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 17(3), 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.A.; Mynatt, R.L.; Cook, G.A.; Kashfi, K. Insulin Regulates Enzyme Activity, Malonyl-CoA Sensitivity and MRNA Abundance of Hepatic Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-I. Biochemical Journal 1995, 310(3), 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Guo, M.; Yang, F.; Han, T.; Du, W.; Zhao, F.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W. Association of CPT1A Gene Polymorphism with the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Case-Control Study. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021, 38(7), 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, A.; Liu, C.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. The Role of the CPT Family in Cancer: Searching for New Therapeutic Strategies. Biology (Basel) 2024, 13(11), 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.N.; Karami-Tehrani, F.; Salami, S. Targeting Prostate Cancer Cell Metabolism: Impact of Hexokinase and CPT-1 Enzymes. Tumor Biology 2015, 36(4), 2893–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thupari, J.N.; Pinn, M.L.; Kuhajda, F.P. Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibition in Human Breast Cancer Cells Leads to Malonyl-CoA-Induced Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation and Cytotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 285(2), 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Kim, J.; D’Alessandro, A.; Monk, E.; Bruce, K.; Elajaili, H.; Nozik-Grayck, E.; Goodspeed, A.; Costello, J.C.; Schlaepfer, I.R. CPT1A Over-Expression Increases Reactive Oxygen Species in the Mitochondria and Promotes Antioxidant Defenses in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(11), 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Vázquez, M.C.; Romero, M. del M.; Todorcevic, M.; Delgado, K.; Calatayud, C.; Benitez -Amaro, A.; La Chica Lhoëst, M.T.; Mera, P.; Zagmutt, S.; Bastías-Pérez, M.; Ibeas, K.; Casals, N.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Llorente-Cortés, V.; Consiglio, A.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L. Implantation of CPT1AM-Expressing Adipocytes Reduces Obesity and Glucose Intolerance in Mice. Metab Eng 2023, 77, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana-Gavaldà, J.M.; Herrero, L.; Malandrino, M.I.; Pañeda, A.; Sol Rodríguez-Peña, M.; Petry, H.; Asins, G.; Van Deventer, S.; Hegardt, F.G.; Serra, D. Molecular Therapy for Obesity and Diabetes Based on a Long-Term Increase in Hepatic Fatty-Acid Oxidation §Δ. Hepatology 2011, 53(3), 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, P.; Muñoz, A.; Sola, A.; Hotter, G. CPT1a Gene Expression Reverses the Inflammatory and Anti-Phagocytic Effect of 7-Ketocholesterol in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Lipids Health Dis 2019, 18(1), 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malandrino, M.I.; Fucho, R.; Weber, M.; Calderon-Dominguez, M.; Mir, J.F.; Valcarcel, L.; Escoté, X.; Gómez-Serrano, M.; Peral, B.; Salvadó, L.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Casals, N.; Vázquez-Carrera, M.; Villarroya, F.; Vendrell, J.J.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L. Enhanced Fatty Acid Oxidation in Adipocytes and Macrophages Reduces Lipid-Induced Triglyceride Accumulation and Inflammation. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2015, 308(9), E756–E769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Liao, X.; Hu, H.; Chen, L.; Meng, L.; Gao, W.; Li, Q. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase System: A New Target for Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Therapy? Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JOGL, G.; HSIAO, Y.; TONG, L. Structure and Function of Carnitine Acyltransferases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004, 1033(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Gandour, R.D.; van der Leij, F.R. Molecular Enzymology of Carnitine Transfer and Transport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 2001, 1546(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Hoppel, C.L. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase Activity in the Rabbit Choroid Plexus: Its Possible Function in Fatty Acid Metabolism and Transport. Neurosci Lett 1992, 140(1), 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Mitochondrial CPT1A: Insights into Structure, Function, and Basis for Drug Development. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefont, J. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferases 1 and 2: Biochemical, Molecular and Medical Aspects. Mol Aspects Med 2004, 25(5–6), 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaepfer, I.R.; Joshi, M. CPT1A-Mediated Fat Oxidation, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Endocrinology 2020, 161(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, D.W. Malonyl-CoA: The Regulator of Fatty Acid Synthesis and Oxidation. J Clin Invest 2012, 122(6), 1958–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.A. Differences in the Sensitivity of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase to Inhibition by Malonyl-CoA Are Due to Differences in Ki Values. J Biol Chem 1984, 259(19), 12030–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.D.; Vandanmagsar, B.; Dubuisson, O.S.; Hodgeson, S.M.; Elks, C.M.; Ravussin, E.; Mynatt, R.L. Examination of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1 Abundance in White Adipose Tissue: Implications in Obesity Research. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2017, 312(5), R816–R820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufer, A.C.; Thoma, R.; Benz, J.; Stihle, M.; Gsell, B.; De Roo, E.; Banner, D.W.; Mueller, F.; Chomienne, O.; Hennig, M. The Crystal Structure of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 2 and Implications for Diabetes Treatment. Structure 2006, 14(4), 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, Y.-S.; Jogl, G.; Esser, V.; Tong, L. Crystal Structure of Rat Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II (CPT-II). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 346(3), 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; Fosch, A.; Garcia-Chica, J.; Zagmutt, S.; Casals, N. Targeting Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1 Isoforms in the Hypothalamus: A Promising Strategy to Regulate Energy Balance. J Neuroendocrinol 2023, 35(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.F.; Weis, B.C.; Husti, J.E.; Foster, D.W.; McGarry, J.D. Mitochondrial Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I Isoform Switching in the Developing Rat Heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270(15), 8952–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, N.T.; van der Leij, F.R.; Jackson, V.N.; Corstorphine, C.G.; Thomson, R.; Sorensen, A.; Zammit, V.A. A Novel Brain-Expressed Protein Related to Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I. Genomics 2002, 80(4), 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.S.; Kumari, S. Fatty Acids and Their Role in Type-2 Diabetes (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021, 22(1), 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Huang, J. The Expanded Role of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Cancer: New Aspects and Targets. Precis Clin Med 2019, 2(3), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koundouros, N.; Poulogiannis, G. Reprogramming of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Br J Cancer 2020, 122(1), 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakil, S.J.; Abu-Elheiga, L.A. Fatty Acid Metabolism: Target for Metabolic Syndrome. J Lipid Res 2009, 50 Suppl (Suppl), S138–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, J.; Begriche, K.; Buron, N.; Porceddu, M.; Borgne-Sanchez, A.; Fromenty, B. Drug-Induced Inhibition of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation and Steatosis. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2013, 1(3), 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mørkholt, A.S.; Oklinski, M.K.; Larsen, A.; Bockermann, R.; Issazadeh-Navikas, S.; Nieland, J.G.K.; Kwon, T.-H.; Corthals, A.; Nielsen, S.; Nieland, J.D.V. Pharmacological Inhibition of Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1 Inhibits and Reverses Experimental Autoimmune Encephalitis in Rodents. PLoS One 2020, 15(6), e0234493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Wang, H.; Xu, Q.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S.; Qu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, X. A Novel CPT1A Covalent Inhibitor Modulates Fatty Acid Oxidation and CPT1A-VDAC1 Axis with Therapeutic Potential for Colorectal Cancer. Redox Biol 2023, 68, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuffee, R.M.; McCommis, K.S.; Ford, D.A. Etomoxir: An Old Dog with New Tricks. J Lipid Res 2024, 65(9), 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratheiser, K.; Schneeweif, B.; Waldhausl, W.; Nowotny, P. Inhibition by Etomoxir of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I Reduces Hepatic Glucose Production and Plasma Lipids in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Metabolism 1991, 40(11), 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bristow, M. Etomoxir: A New Approach to Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure. The Lancet 2000, 356(9242), 1621–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubarsch, C.J.F.; Rohrbach, M.; Karrasch, M.; Boehm, E.; Polonski, L.; Ponikowski, P.; Rhein, S. A Double-Blind Randomized Multicentre Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Two Doses of Etomoxir in Comparison with Placebo in Patients with Moderate Congestive Heart Failure: The ERGO (Etomoxir for the Recovery of Glucose Oxidation) Study. Clin Sci 2007, 113(4), 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, R.; Mannucci, E.; Pessotto, P.; Tassoni, E.; Carminati, P.; Giannessi, F.; Arduini, A. Selective Reversible Inhibition of Liver Carnitine Palmitoyl-Transferase 1 by Teglicar Reduces Gluconeogenesis and Improves Glucose Homeostasis. Diabetes 2011, 60(2), 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannessi, F.; Pessotto, P.; Tassoni, E.; Chiodi, P.; Conti, R.; De Angelis, F.; Dell’Uomo, N.; Catini, R.; Deias, R.; Tinti, M.O.; Carminati, P.; Arduini, A. Discovery of a Long-Chain Carbamoyl Aminocarnitine Derivative, a Reversible Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase Inhibitor with Antiketotic and Antidiabetic Activity. J Med Chem 2003, 46(2), 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, K.; Dai, J.-Y. Progress of Potential Drugs Targeted in Lipid Metabolism Research. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1067652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugiatti, E.; Tenca, C.; Ravera, S.; Fabbi, M.; Ghiotto, F.; Mazzarello, A.N.; Bagnara, D.; Reverberi, D.; Zarcone, D.; Cutrona, G.; Ibatici, A.; Ciccone, E.; Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Fais, F.; Bruno, S. A Reversible Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase (CPT1) Inhibitor Offsets the Proliferation of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. Haematologica 2018, 103(11), e531–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.R.; Mirabilii, S.; Allegretti, M.; Licchetta, R.; Calarco, A.; Torrisi, M.R.; Foà, R.; Nicolai, R.; Peluso, G.; Tafuri, A. Targeting the Leukemia Cell Metabolism by the CPT1a Inhibition: Functional Preclinical Effects in Leukemias. Blood 2015, 126(16), 1925–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafian, H.; Horowitz, J.D.; Frenneaux, M.P. Perhexiline. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 2007, 25(1), 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, B.; Tomita, Y.; Drew, P.; Price, T.; Maddern, G.; Smith, E.; Fenix, K. Perhexiline: Old Drug, New Tricks? A Summary of Its Anti-Cancer Effects. Molecules 2023, 28(8), 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Unger, S.A.; Horowitz, J.D. Inhibition of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 in Rat Heart and Liver by Perhexiline and Amiodarone. Biochem Pharmacol 1996, 52(2), 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargman, S.; Wong, E.; Greig, G.M.; Falgueyret, J.-P.; Cromlish, W.; Ethier, D.; Yergey, J.A.; Riendeau, D.; Evans, J.F.; Kennedy, B.; Tagari, P.; Francis, D.A.; O’Neill, G.P. Mechanism of Selective Inhibition of Human Prostaglandin G/H Synthase-1 and -2 in Intact Cells. Biochem Pharmacol 1996, 52(7), 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Song, Z.G.; Jiao, H.C.; Lin, H. Dexamethasone Facilitates Lipid Accumulation in Chicken Skeletal Muscle. Stress 2012, 15(4), 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xia, H.; Ni, D.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yi, Q.; Xie, Y. High-Dose Dexamethasone Manipulates the Tumor Microenvironment and Internal Metabolic Pathways in Anti-Tumor Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(5), 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccarelli, S.M.; Chomienne, O.; Gubler, M.; Arduini, A. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase (CPT) Modulators: A Medicinal Chemistry Perspective on 35 Years of Research. J Med Chem 2011, 54(9), 3109–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, X.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, X.; Song, Y. A Mini Review of Small-Molecule Inhibitors Targeting Palmitoyltransferases. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2022, 5, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, H.N. Biologic Rationale for the Use of Beta-Blockers in the Treatment of Heart Failure. Heart Fail Rev 2004, 9(2), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Dhillon, P.; Wambolt, R.; Parsons, H.; Brownsey, R.; Allard, M.F.; McNeill, J.H. Metoprolol Improves Cardiac Function and Modulates Cardiac Metabolism in the Streptozotocin-Diabetic Rat. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2008, 294(4), H1609–H1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, M.; Urien, S.; Le Louet, H.; Tillement, J.-P.; Morin, D. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 by a Trimetazidine Derivative, S-15176. Pharmacol Res 2001, 44(2), 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xing, Y. Trimetazidine and L-carnitine Prevent Heart Aging and Cardiac Metabolic Impairment in Rats via Regulating Cardiac Metabolic Substrates. Exp Gerontol 2019, 119, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Horowitz, J.D. Effect of Trimetazidine on Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 in the Rat Heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1998, 12(4), 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, T.W.; Higgins, A.J.; Cook, G.A.; Harris, R.A. Two Mechanisms Produce Tissue-Specific Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation by Oxfenicine. Biochemical Journal 1985, 227(2), 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarman, G.; Marais, E.; Lochner, A.; du Toit, E.F. Effect of Chronic CPT-1 Inhibition on Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury (I/R) in a Model of Diet-Induced Obesity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2012, 26(3), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielefeld, D.; Vary, T.; Neely, J. Inhibition of Carnitine Palmitoyl-CoA Transferase Activity and Fatty Acid Oxidation by Lactate and Oxfenicine in Cardiac Muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1985, 17(6), 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge, G.; Stern, C.M. The Uptake of Tritium-Labelled Carnitine by Monolayer Cultures of Human Fetal Muscle and Its Potential as a Label in Cytotoxicity Studies. Clin Exp Immunol 1981, 44(1), 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, M.; Geelen, M.J.H. Activity of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase in Mitochondrial Outer Membranes and Peroxisomes in Digitonin-Permeabilized Hepatocytes. Selective Modulation of Mitochondrial Enzyme Activity by Okadaic Acid. Biochemical Journal 1992, 287(2), 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, J.D.; Leatherman, G.F.; Foster, D.W. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I. The Site of Inhibition of Hepatic Fatty Acid Oxidation by Malonyl-CoA. J Biol Chem 1978, 253(12), 4128–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C.R.; Brolin, C.; Turner, N.; Cleasby, M.E.; van der Leij, F.R.; Cooney, G.J.; Kraegen, E.W. Overexpression of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I in Skeletal Muscle in Vivo Increases Fatty Acid Oxidation and Reduces Triacylglycerol Esterification. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007, 292(4), E1231–E1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, J.D.; Mills, S.E.; Long, C.S.; Foster, D.W. Observations on the Affinity for Carnitine, and Malonyl-CoA Sensitivity, of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I in Animal and Human Tissues. Demonstration of the Presence of Malonyl-CoA in Non-Hepatic Tissues of the Rat. Biochemical Journal 1983, 214(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, C.R.; Hoy, A.J.; Turner, N.; Watt, M.J.; Allen, T.L.; Carpenter, K.; Cooney, G.J.; Febbraio, M.A.; Kraegen, E.W. Overexpression of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 in Skeletal Muscle Is Sufficient to Enhance Fatty Acid Oxidation and Improve High-Fat Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58(3), 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, L.L.; Abraham, T.; Helmrath, T. A Rapid Spectrophotometric Assay for Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase. Anal Biochem 1972, 50(2), 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, R.P.; Crockett, E.L. Endpoint Fluorometric Assays for Determining Activities of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase and Citrate Synthase. Anal Biochem 2000, 287(1), 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Dong, X.; Xiao, L.; Tan, Z.; Luo, X.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Shi, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, N.; Du, Q.; Xie, L.; Hu, J.; Weng, X.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Q.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liao, W.; Bode, A.M.; Cao, Y. CPT1A-Mediated Fatty Acid Oxidation Promotes Cell Proliferation via Nucleoside Metabolism in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13(4), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Xiao, L.; Tang, M.; Bai, F.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Shi, F.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Du, Q.; Lu, J.; Weng, X.; Yi, W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Q.; Onuchic, J.N.; Bode, A.M.; Luo, X.; Cao, Y. Targeting CPT1A-Mediated Fatty Acid Oxidation Sensitizes Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma to Radiation Therapy. Theranostics 2018, 8(9), 2329–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye, A.; Borthwick, K.; Esnous, C.; Price, N.T.; Gobin, S.; Jackson, V.N.; Zammit, V.A.; Girard, J.; Prip-Buus, C. Demonstration of N- and C-Terminal Domain Intramolecular Interactions in Rat Liver Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1 That Determine Its Degree of Malonyl-CoA Sensitivity. Biochem J 2005, 387 (Pt 1), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, S.; Zonetti, M.J.; Fisco, T.; Polidoro, C.; Bocchinfuso, G.; Palleschi, A.; Novelli, G.; Spagnoli, L.G.; Mazzarelli, P. Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase-1A (CPT1A): A New Tumor Specific Target in Human Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7(15), 19982–19996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierz, S.; Neumann-Schmidt, S. Inhibition of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase (CPT) by Chlorpromazine in Muscle of Patients with CPT Deficiency. J Neurol 1989, 236(4), 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cui, F.; Meng, L.; Chen, G.; Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Woldegiorgis, G. Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase Inhibitor in Diabetes. Journal of Molecular and Genetic Medicine 2016, 10(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).