Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Description

2.2. Determination of Meat Quality Traits

2.3. Circle-seq Data Analysis

2.4. EccDNAs Difference Analysis and Gene Annotation

2.5. Verification of eccDNAs

2.6. RNA-seq Data Analysis

2.7. Validation of DEGs

2.8. Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation of eccDNAs and eccDEGs

2.9. Prediction of Regulatory Network of eccDNAs-miRNAs-Genes

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Meat Quality Indicators in YN and YL Groups

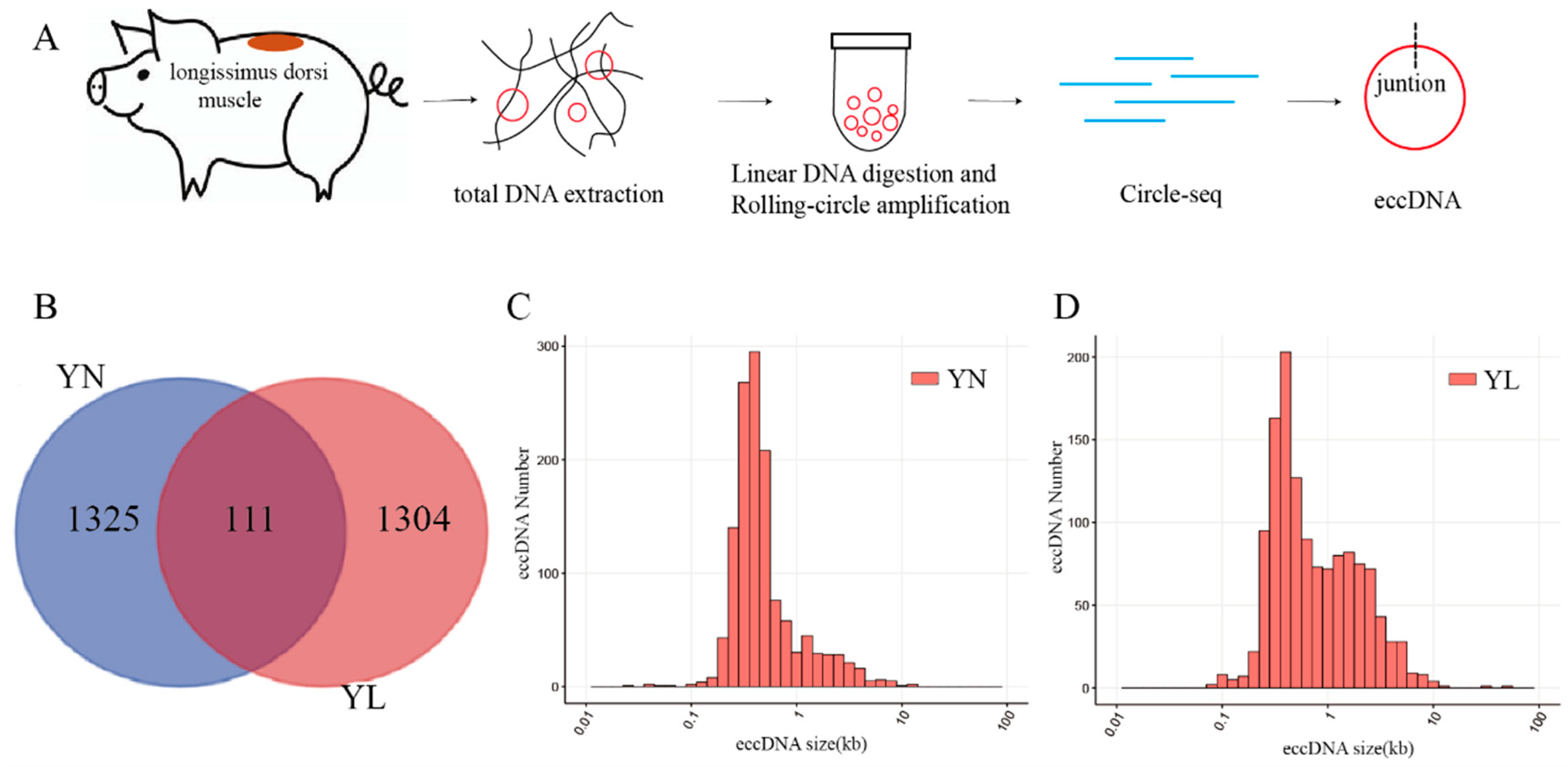

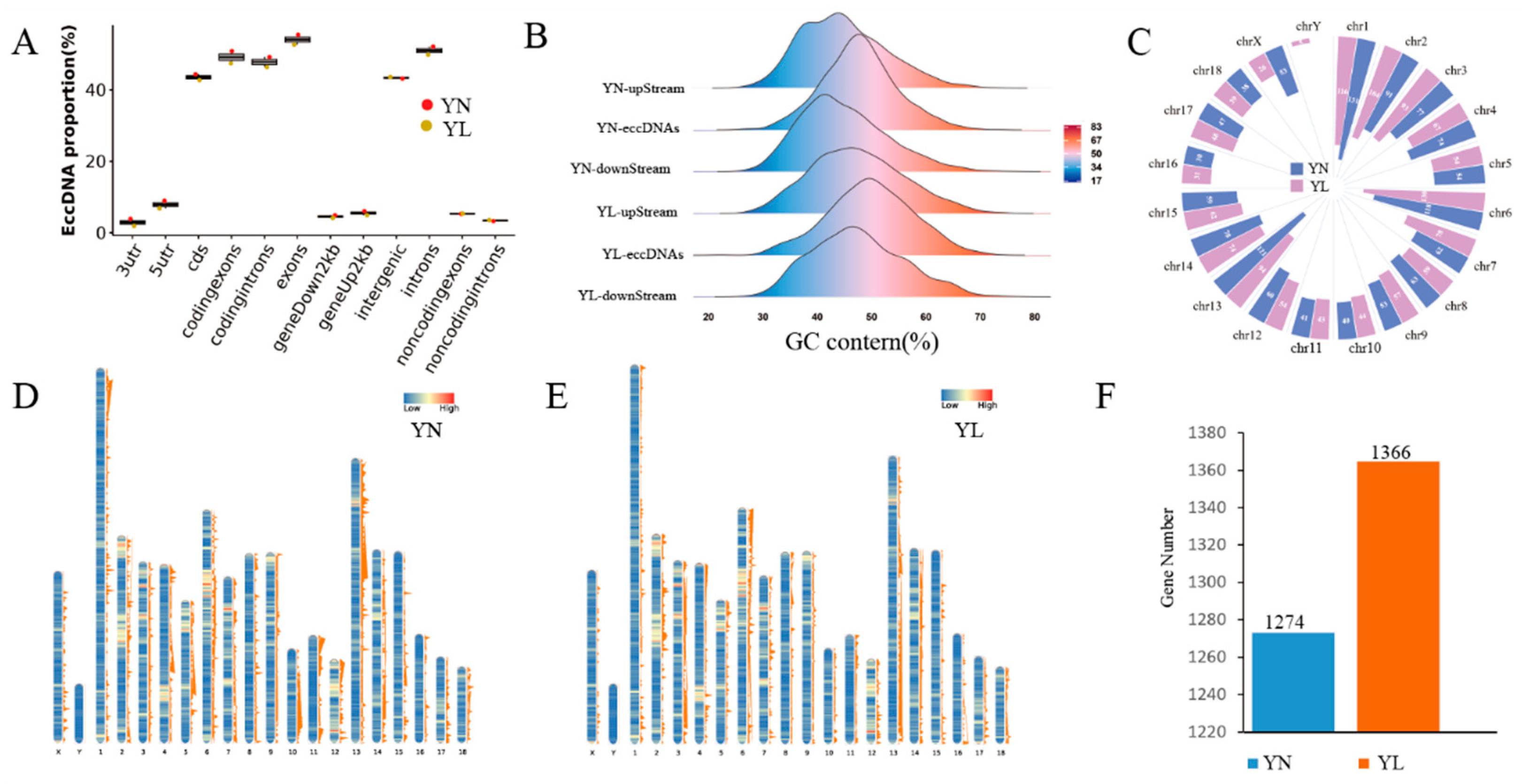

3.2. Basic Features of eccDNAs in YN and YL Pigs

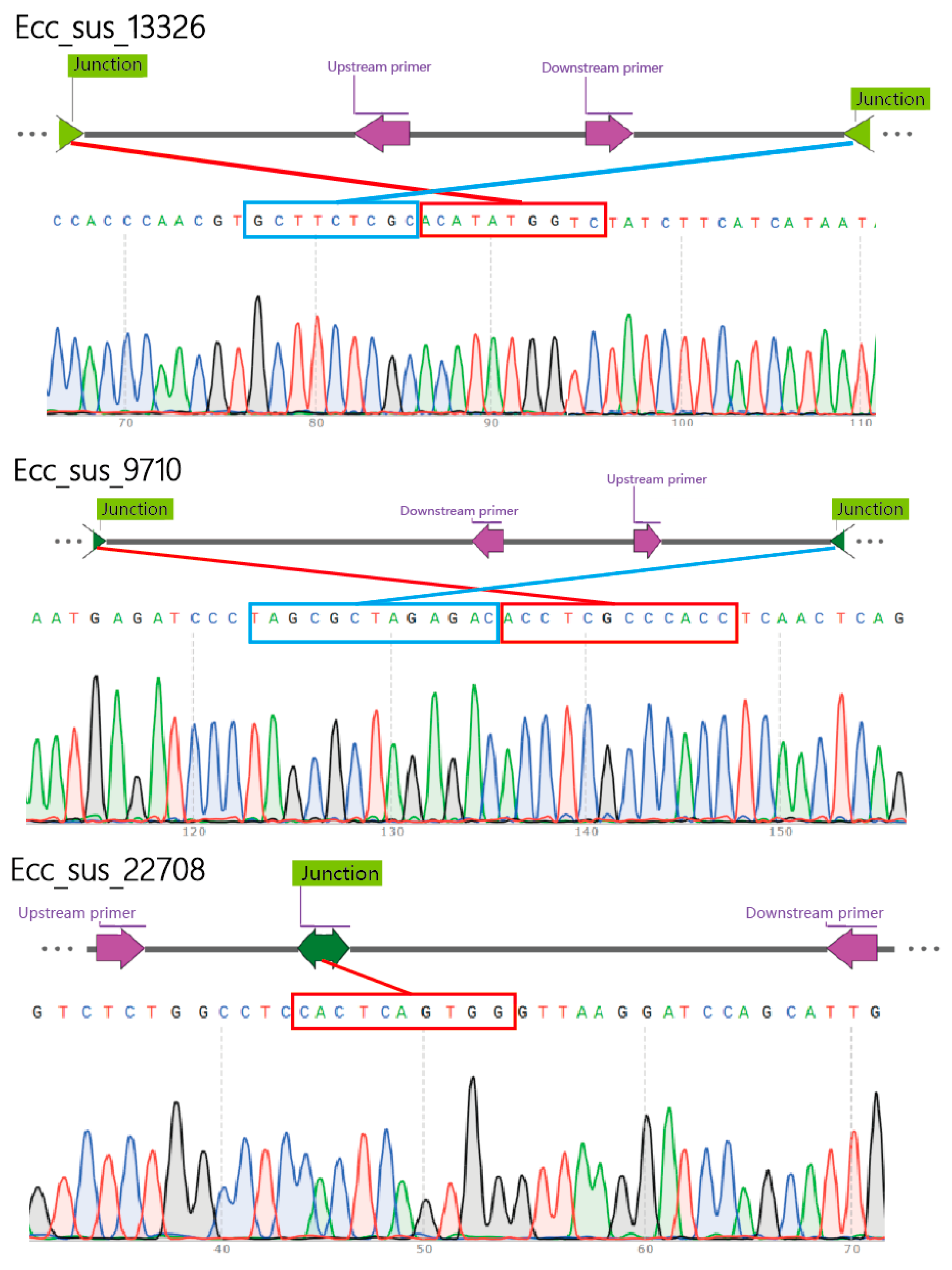

3.3. Validation of eccDNAs

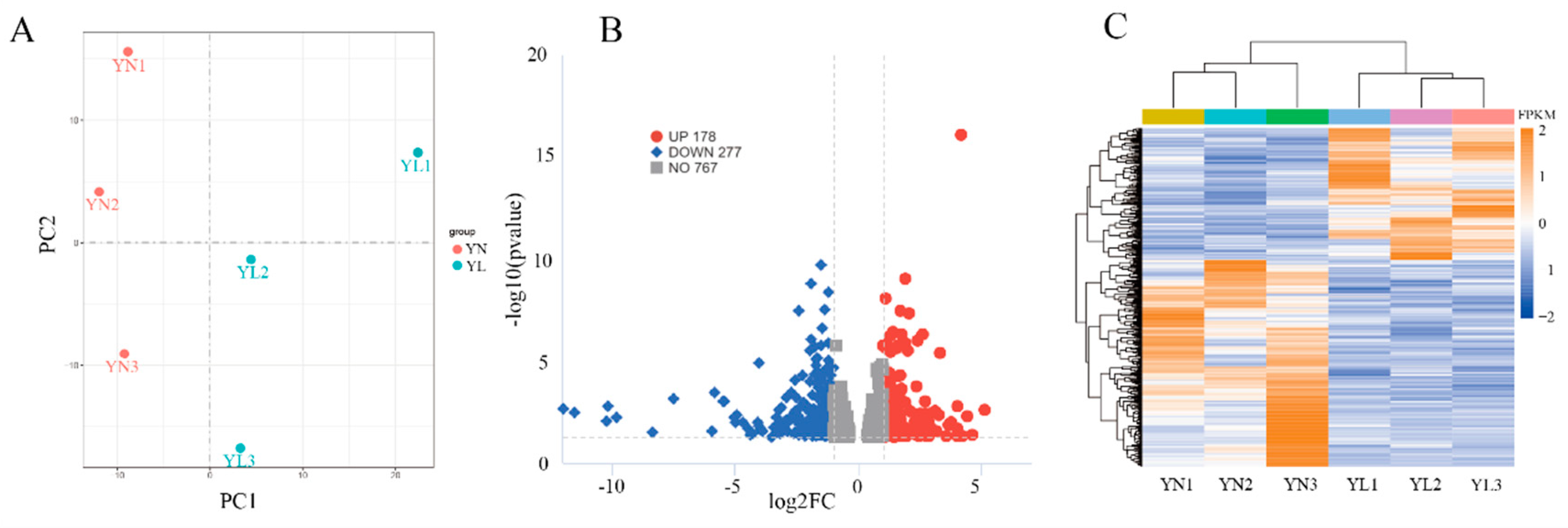

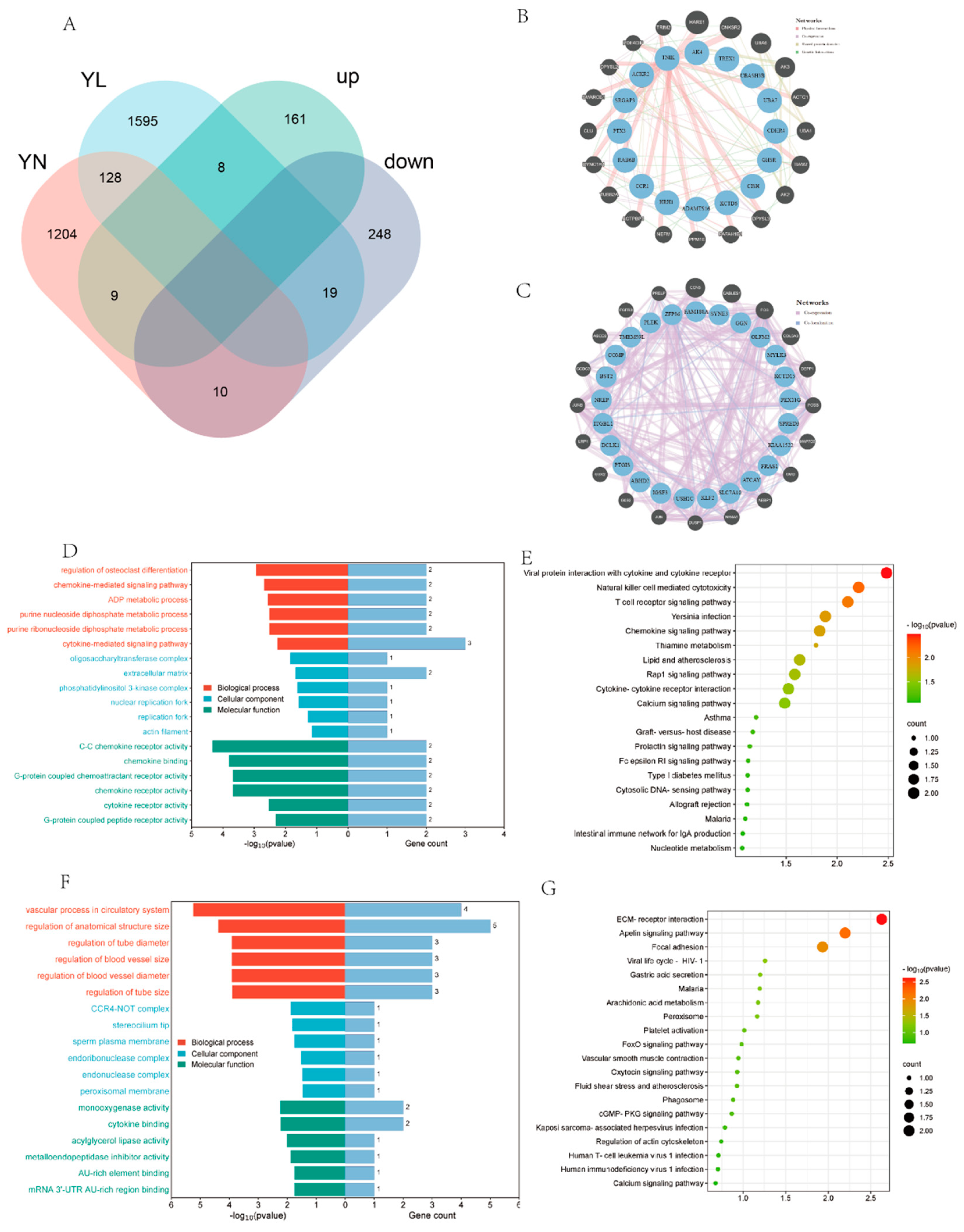

3.4. Identification of DEGs

3.5. Identification and Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed eccDNA-Amplified Encoding Genes

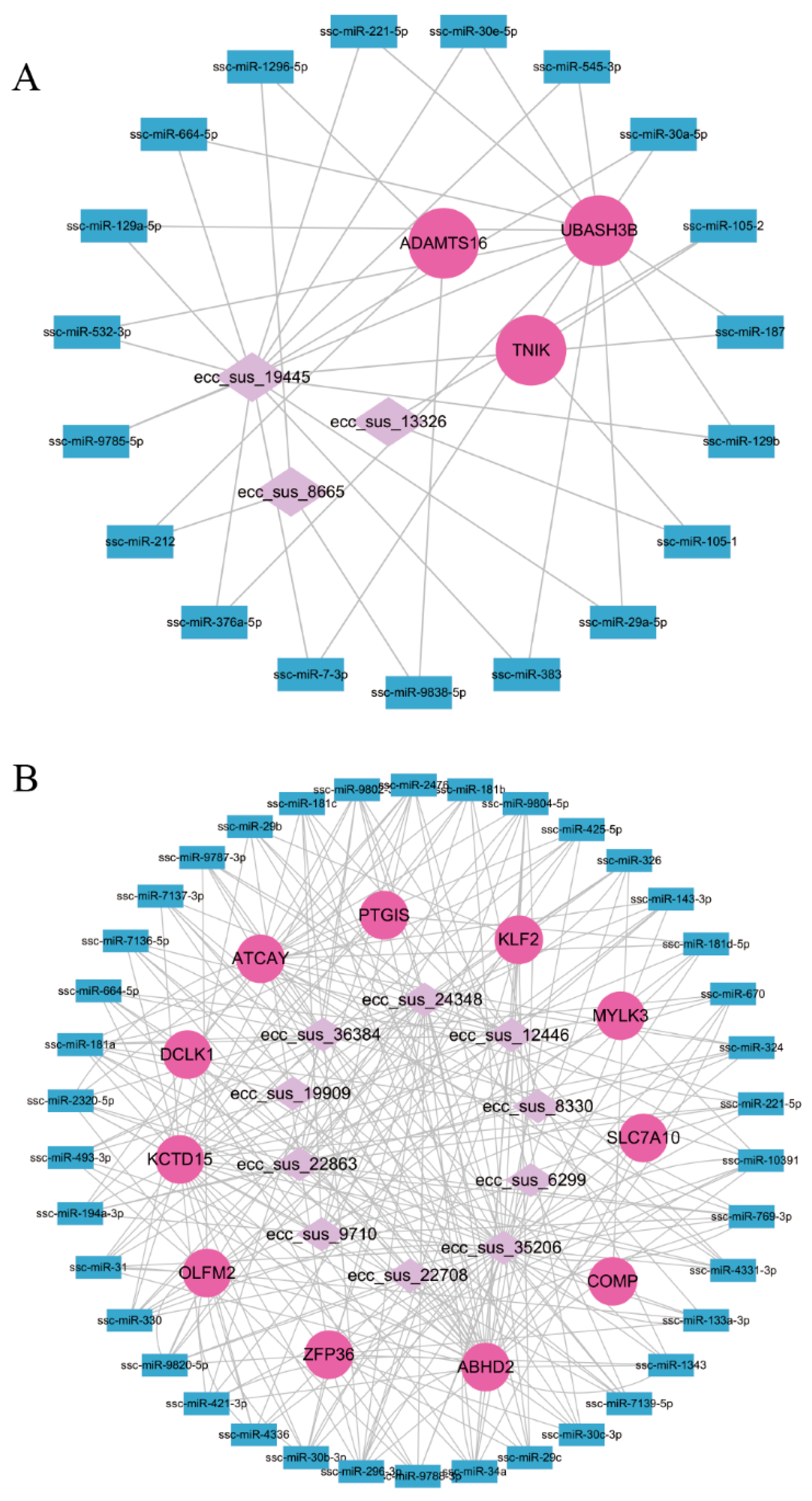

3.6. EccDNAs-miRNAs-Genes Regulatory Network

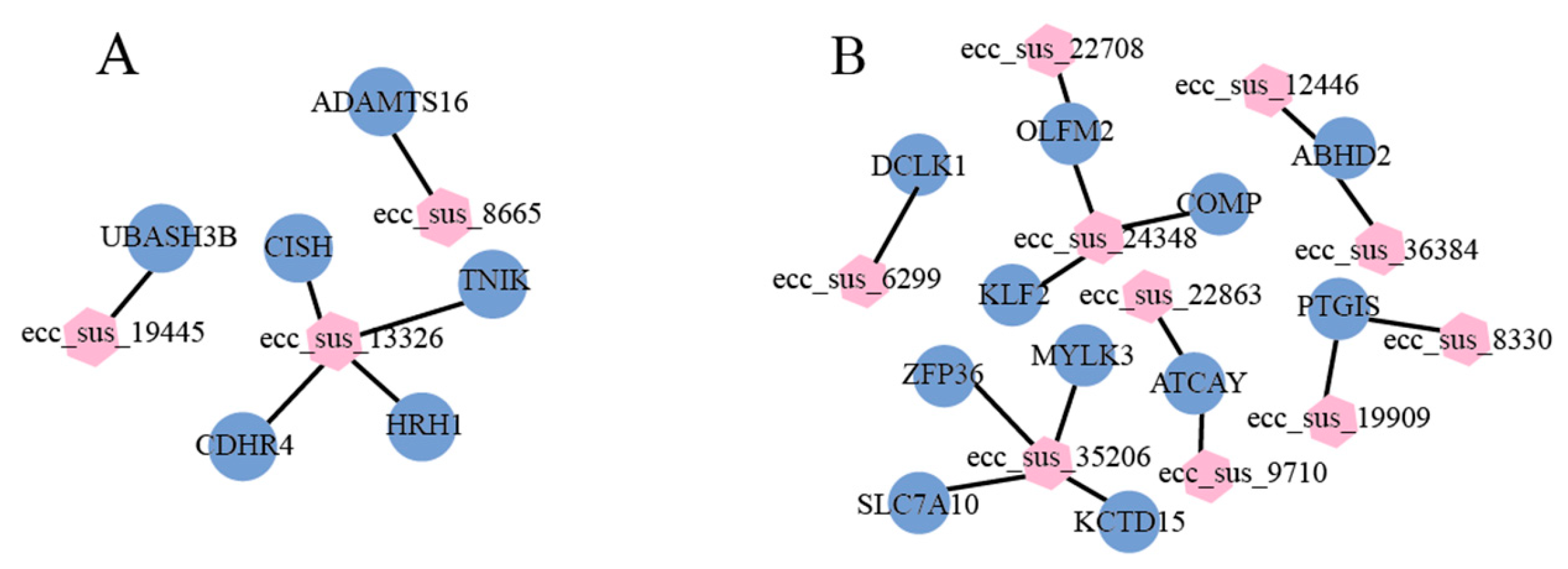

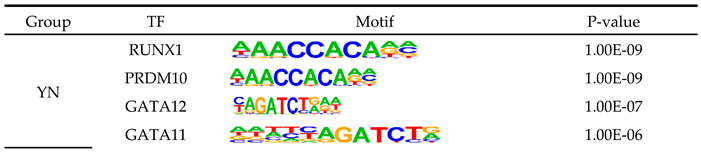

3.7. Identification of Candidate eccDNAs and eccDEGs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Yuan, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Qi, X.; Guo, Y.; Sheng, X.; Liu, J., et al. Comprehensive Analysis of the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Regulatory Network for Intramuscular Fat in Pigs. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Davoli, R.; Luise, D.; Mingazzini, V.; Zambonelli, P.; Braglia, S.; Serra, A.; Russo, V. Genome-wide study on intramuscular fat in Italian Large White pig breed using the PorcineSNP60 BeadChip. J Anim Breed Genet 2016, 133, 277-282. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, L.; Tong, X.; Li, R.; Jin, E.; Ren, M.; Gao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, S. Transcriptomic Profiling of Meat Quality Traits of Skeletal Muscles of the Chinese Indigenous Huai Pig and Duroc Pig. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Li, L.; Yu, N.; Xiong, S.; Xiao, S.; Zheng, H.; Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Huang, L. Phenotypic correlations of carpal gland diverticular number with production traits and its genome-wide association analysis in multiple pig populations. Anim Genet 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gui, R.; Liu, F.; Tong, C.; Wang, X. Transcriptome sequencing analysis of bovine mammary epithelial cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Anim Biotechnol 2024, 35, 2290527. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, T.; Jiang, Q.; Xi, Q.; Liu, G.E.; Zhang, Y. Integrated meta-omics reveals the regulatory landscape involved in lipid metabolism between pig breeds. Microbiome 2024, 12, 33. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Ge, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Sun, S.; Li, X. Screening of lncRNA profiles during intramuscular adipogenic differentiation in longissimus dorsi and semitendinosus muscles in pigs. Anim Biotechnol 2023, 34, 4616-4626. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X.; Shi, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Hou, X.; Shi, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Integrating genome-wide association study with RNA-seq revealed DBI as a good candidate gene for intramuscular fat content in Beijing black pigs. Anim Genet 2023, 54, 24-34. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Kang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y. TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic analyses on the longissimus dorsi to identify the proteins underlying intramuscular fat content in pigs. J Proteomics 2020, 213, 103630. [CrossRef]

- Gerovska, D.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J. Skeletal Muscles of Sedentary and Physically Active Aged People Have Distinctive Genic Extrachromosomal Circular DNA Profiles. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wen, A.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Hu, H. Identification and characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in Wei and Large White pigs by high-throughput sequencing. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1085474. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jia, R.; Ge, T.; Ge, S.; Zhuang, A.; Chai, P.; Fan, X. Extrachromosomal circular DNA: biogenesis, structure, functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 342. [CrossRef]

- Hotta, Y.; Bassel, A. MOLECULAR SIZE AND CIRCULARITY OF DNA IN CELLS OF MAMMALS AND HIGHER PLANTS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1965, 53, 356-362. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Jiang, W.; Ye, L.; Li, T.; Yu, X.; Liu, L. Classification of extrachromosomal circular DNA with a focus on the role of extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) in tumor heterogeneity and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020, 1874, 188392. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, T.; Kumar, P.; Koseoglu, M.M.; Dutta, A. Discoveries of Extrachromosomal Circles of DNA in Normal and Tumor Cells. Trends Genet 2018, 34, 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Houben, A.; Segal, D. Extrachromosomal circular DNA derived from tandemly repeated genomic sequences in plants. Plant J 2008, 53, 1027-1034. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Regev, A.; Lavi, S. Small polydispersed circular DNA (spcDNA) in human cells: association with genomic instability. Oncogene 1997, 14, 977-985. [CrossRef]

- Molin, W.T.; Yaguchi, A.; Blenner, M.; Saski, C.A. The EccDNA Replicon: A Heritable, Extranuclear Vehicle That Enables Gene Amplification and Glyphosate Resistance in Amaranthus palmeri. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 2132-2140. [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.D.; Lin, L.; Xiang, X.; Petersen, T.S.; Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Kjeldsen, E.; Jensen, U.B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X., et al. CRISPR-C: circularization of genes and chromosome by CRISPR in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, e131. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gujar, A.D.; Wong, C.H.; Tjong, H.; Ngan, C.Y.; Gong, L.; Chen, Y.A.; Kim, H.; Liu, J.; Li, M., et al. Oncogenic extrachromosomal DNA functions as mobile enhancers to globally amplify chromosomal transcription. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 694-707.e697. [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.M.; King, M.; Pizza, G.; Krueger, F.; Vergara, X.; Houseley, J. Transcription-induced formation of extrachromosomal DNA during yeast ageing. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000471. [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.D.; Parsons, L.; Jørgensen, T.S.; Botstein, D.; Regenberg, B. Extrachromosomal circular DNA is common in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E3114-3122. [CrossRef]

- Stanfield, S.W.; Lengyel, J.A. Small circular DNA of Drosophila melanogaster: chromosomal homology and kinetic complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979, 76, 6142-6146. [CrossRef]

- Sunnerhagen, P.; Sjöberg, R.M.; Karlsson, A.L.; Lundh, L.; Bjursell, G. Molecular cloning and characterization of small polydisperse circular DNA from mouse 3T6 cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1986, 14, 7823-7838. [CrossRef]

- Stanfield, S.W.; Helinski, D.R. Cloning and characterization of small circular DNA from Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Cell Biol 1984, 4, 173-180. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Duan, D.; Xue, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, K.; Qiao, R.; Li, X.L.; Li, X.J. An association study on imputed whole-genome resequencing from high-throughput sequencing data for body traits in crossbred pigs. Anim Genet 2022, 53, 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Li, C.; Duan, D.; Wang, M.; Han, X.; Wang, K.; Qiao, R.; Li, X.J.; Li, X.L. Genome-wide association studies for growth-related traits in a crossbreed pig population. Anim Genet 2021, 52, 217-222. [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczak, A.; Składanowska-Baryza, J.; Cieślak, A.; Stanisz, M.; Skrzypczak, E.; Sell-Kubiak, E.; Ślósarz, P.; Racewicz, P. Effect of prudent use of antimicrobials in the early phase of infection in pigs on the performance and meat quality of fattening pigs. Meat Sci 2024, 212, 109471. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Niu, X.; Li, S.; Huang, S.; Ran, X.; Wang, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of longissimus dorsi muscle reveal potential genes affecting meat trait in Chinese indigenous Xiang pig. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 8486. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114-2120. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint arXiv:13033997 2013.

- Prada-Luengo, I.; Krogh, A.; Maretty, L.; Regenberg, B. Sensitive detection of circular DNAs at single-nucleotide resolution using guided realignment of partially aligned reads. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 663. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841-842. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ji, N.; Zhao, R.; Liang, J.; Jiang, J.; Tian, H. Extrachromosomal circular DNAs are common and functional in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1464. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Ryan, D.P.; Grüning, B.; Bhardwaj, V.; Kilpert, F.; Richter, A.S.; Heyne, S.; Dündar, F.; Manke, T. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W160-165. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lv, D.; Ge, Y.; Shi, J.; Weijers, D.; Yu, G.; Chen, J. RIdeogram: drawing SVG graphics to visualize and map genome-wide data on the idiograms. PeerJ Comput Sci 2020, 6, e251. [CrossRef]

- Parkhomchuk, D.; Borodina, T.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Banaru, M.; Hallen, L.; Krobitsch, S.; Lehrach, H.; Soldatov, A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, e123. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yang, M.; Guo, H.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Liu, P.; Lian, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yan, J., et al. Single-cell RNA-Seq profiling of human preimplantation embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013, 20, 1131-1139. [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods 2008, 5, 621-628. [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 290-295. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923-930. [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 2010, 11, R106. [CrossRef]

- Otasek, D.; Morris, J.H.; Bouças, J.; Pico, A.R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 185. [CrossRef]

- Soto, L.F.; Li, Z.; Santoso, C.S.; Berenson, A.; Ho, I.; Shen, V.X.; Yuan, S.; Fuxman Bass, J.I. Compendium of human transcription factor effector domains. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 514-526. [CrossRef]

- Schmeier, S.; Alam, T.; Essack, M.; Bajic, V.B. TcoF-DB v2: update of the database of human and mouse transcription co-factors and transcription factor interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D145-d150. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Bai, X.; Ai, B.; Zhang, G.; Song, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, L.; Qian, F.; Li, Y., et al. TF-Marker: a comprehensive manually curated database for transcription factors and related markers in specific cell and tissue types in human. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D402-d412. [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, K.; Bee, T.; Wilson, N.K.; Janes, M.E.; Kinston, S.; Polderdijk, S.; Kolb-Kokocinski, A.; Ottersbach, K.; Pencovich, N.; Groner, Y., et al. A Runx1-Smad6 rheostat controls Runx1 activity during embryonic hematopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol 2011, 31, 2817-2826. [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.D.; Mohiyuddin, M.; Prada-Luengo, I.; Sailani, M.R.; Halling, J.F.; Plomgaard, P.; Maretty, L.; Hansen, A.J.; Snyder, M.P.; Pilegaard, H., et al. Circular DNA elements of chromosomal origin are common in healthy human somatic tissue. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1069. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, T.; Shibata, Y.; Kumar, P.; Dillon, L.; Dutta, A. Small extrachromosomal circular DNAs, microDNA, produce short regulatory RNAs that suppress gene expression independent of canonical promoters. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 4586-4596. [CrossRef]

- Shoger, K.E.; Cheemalavagu, N.; Cao, Y.M.; Michalides, B.A.; Chaudhri, V.K.; Cohen, J.A.; Singh, H.; Gottschalk, R.A. CISH attenuates homeostatic cytokine signaling to promote lung-specific macrophage programming and function. Sci Signal 2021, 14, eabe5137. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.B.; Gordus, A.; Krall, J.A.; MacBeath, G. A quantitative protein interaction network for the ErbB receptors using protein microarrays. Nature 2006, 439, 168-174. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wei, X.; Shi, L.; Chen, B.; Zhao, G.; Yang, H. Integrative genomic analyses of the histamine H1 receptor and its role in cancer prediction. Int J Mol Med 2014, 33, 1019-1026. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y. CircADAMTS16 Inhibits Differentiation and Promotes Proliferation of Bovine Adipocytes by Targeting miR-10167-3p. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Jin, W.; Lee, H.J. Acute exercise regulates adipogenic gene expression in white adipose tissue. Biol Sport 2016, 33, 381-391. [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Riosalido, A.; Bertran, L.; Vilaró-Blay, M.; Aguilar, C.; Martínez, S.; Paris, M.; Sabench, F.; Riesco, D.; Binetti, J.; Castillo, D.D., et al. The Role of Olfactomedin 2 in the Adipose Tissue-Liver Axis and Its Implication in Obesity-Associated Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, W.; Xu, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Cui, S.; Zhuo, Z.; Cui, Y.; Mei, H., et al. PTGIS May Be a Predictive Marker for Ovarian Cancer by Regulating Fatty Acid Metabolism. Comput Math Methods Med 2023, 2023, 2397728. [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, P.E.; Chen, F.S.; Moergelin, M.; Carlson, C.S.; Leslie, M.P.; Perris, R.; Fang, C. Matrix-matrix interaction of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and fibronectin. Matrix Biol 2002, 21, 461-470. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Gao, J.; Xie, Z.; Xie, M.; Song, R.; Yuan, X.; Wu, Y.; Ou, D. Effect of chronic deltamethrin exposure on brain transcriptome and metabolome of juvenile crucian carp. Environ Toxicol 2024, 39, 1544-1555. [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Liang, R.; Tan, B.; Li, L.; Lyu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Hu, X.; Wu, D., et al. Effects of Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes PTGIS and HRASLS on Phenotype, Prognosis, and Tumor Immunity in Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2023, 2023, 6811625. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shang, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B. Association of KCTD15 gene with fat deposition in pigs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2022, 106, 537-544. [CrossRef]

- Brahma, P.K.; Zhang, H.; Murray, B.S.; Shu, F.J.; Sidell, N.; Seli, E.; Kallen, C.B. The mRNA-binding protein Zfp36 is upregulated by β-adrenergic stimulation and represses IL-6 production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012, 20, 40-47. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y. Integrated analysis of mRNA and extrachromosomal circular DNA profiles to identify the potential mRNA biomarkers in breast cancer. Gene 2023, 857, 147174. [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.D.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Prada-Luengo, I.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Regenberg, B. Near-Random Distribution of Chromosome-Derived Circular DNA in the Condensed Genome of Pigeons and the Larger, More Repeat-Rich Human Genome. Genome Biol Evol 2020, 12, 3762-3777. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chi, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yang, M.; Tan, Q.; Hao, J.; Lin, Y.; Mao, F.; He, S.; Yang, J. Identification and characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in large-artery atherosclerotic stroke. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18210. [CrossRef]

- Sin, S.T.K.; Jiang, P.; Deng, J.; Ji, L.; Cheng, S.H.; Dutta, A.; Leung, T.Y.; Chan, K.C.A.; Chiu, R.W.K.; Lo, Y.M.D. Identification and characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 1658-1665. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Turner, K.M.; Nguyen, N.; Raviram, R.; Erb, M.; Santini, J.; Luebeck, J.; Rajkumar, U.; Diao, Y.; Li, B., et al. Circular ecDNA promotes accessible chromatin and high oncogene expression. Nature 2019, 575, 699-703. [CrossRef]

- Verhaak, R.G.W.; Bafna, V.; Mischel, P.S. Extrachromosomal oncogene amplification in tumour pathogenesis and evolution. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19, 283-288. [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Pan, X.; Lin, L.; Li, L.; Yuan, S.; Han, P.; Ji, X.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Chu, Z., et al. Characterization of Plasma Extrachromosomal Circular DNA in Gouty Arthritis. Front Genet 2022, 13, 859513. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, S.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, H.; Kuang, M.; Li, X. Identification and characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in alcohol induced osteonecrosis of femoral head. Front Genet 2022, 13, 918379. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wu, D.; Shen, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Xiong, H.; Xiong, Z.; Gong, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W., et al. Deciphering the role of extrachromosomal circular DNA in adipose stem cells from old and young donors. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 341. [CrossRef]

- Mansisidor, A.; Molinar, T., Jr.; Srivastava, P.; Dartis, D.D.; Pino Delgado, A.; Blitzblau, H.G.; Klein, H.; Hochwagen, A. Genomic Copy-Number Loss Is Rescued by Self-Limiting Production of DNA Circles. Mol Cell 2018, 72, 583-593.e584. [CrossRef]

- Gresham, D.; Usaite, R.; Germann, S.M.; Lisby, M.; Botstein, D.; Regenberg, B. Adaptation to diverse nitrogen-limited environments by deletion or extrachromosomal element formation of the GAP1 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 18551-18556. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Tong, X.; Qiu, Q.; Pan, J.; Wei, S.; Ding, Y.; Feng, Y.; Hu, X.; Gong, C. Identification and characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in the silk gland of Bombyx mori. Insect Sci 2023, 30, 1565-1578. [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; McGill, J.R.; Forseth, B.J.; Davidson, K.K.; Bradley, T.P.; Van Devanter, D.R.; Wahl, G.M. Elimination of extrachromosomally amplified MYC genes from human tumor cells reduces their tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 8165-8169. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cui, B.D.; Gong, M.; Li, Q.X.; Zhang, L.X.; Chen, J.L.; Chi, J.; Zhu, L.L.; Xu, E.P.; Wang, Z.M., et al. An ethanolic extract of Arctium lappa L. leaves ameliorates experimental atherosclerosis by modulating lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses through PI3K/Akt and NF-κB singnaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 325, 117768. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Quan, C.; Huang, Y.; Ji, W.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zou, H.; Li, Q., et al. Constitutive ERK1/2 activation contributes to production of double minute chromosomes in tumour cells. J Pathol 2015, 235, 14-24. [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Su, B.; Ning, N.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Zishen Yutai pills restore fertility in premature ovarian failure through regulating arachidonic acid metabolism and the ATK pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 324, 117782. [CrossRef]

- 童新宇. 家蚕丝腺eccDNAs的特征及eccDNA~(fib-L)的功能研究 [D], 2022.

- Jiang, X.; Pan, X.; Li, W.; Han, P.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Lv, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y., et al. Genome-wide characterization of extrachromosomal circular DNA in gastric cancer and its potential role in carcinogenesis and cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 191. [CrossRef]

| eccDNAs | Forward Primers | Reverse Primers |

|---|---|---|

| Ecc_sus_13326 | CAATCGCACCAGTGAGGCC | GGTGGTGTTGAGGATGAATGTG |

| Ecc_sus_9710 | ATTCCCATTGTGGCTCTTG | CACAAATCCAAAGGGAACAA |

| Ecc_sus_22708 | GAGATGTGCCAGGTGGACTGT | GTAATCAACCCTGACCATCTCCT |

| Gene Name | Forward Primers | Reverse Primers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBA7 | CTTCTGCTGAGTTTGGCCCT | ATAGTTCTGAGCTCGCAGGC | |

| GPCPD1 | TCTGGTGGGAGCTTTGCTTT | TGGTGGGGATTTGTCTTCCAA | |

| AKR1C4 | GACATCGAGGTGCAGGGAAT | CAAAGGCTGCACCGTGACTA | |

| GRM4 | GTCGGCAGACAGATGGTCTT | TGCTCTTAGGGACCAAATCCC | |

| FRAS1 | GTCAAGAAGTGCACCAACCG | CGGCATCGATCACAAACTGC | |

| PER2 | ACTTCGTCTTCCTGTCCAGATG | CTTTCAGCTCCCTCAGCGTT | |

| Item | YN | YL |

|---|---|---|

| Meat color 45min | 4.00±0.00a | 2.40±0.17b |

| Ph 45min | 5.45±0.12b | 6.17±0.15c |

| Marble grain 45min | 3.50±0.50 | 2.50±0.50 |

| Drip loss % | 1.04±0.12 | 1.10±0.27 |

| Moisture % | 73.66±1.66 | 75.14±0.66 |

| Intramuscular fat content (dry sample) % | 13.80±0.63a | 9.39±0.44c |

| Protein content (dry sample) % | 77.90±0.87 | 81.57±2.77 |

| eccDNAs ID | eccDNAs Segment | Gene | FPKM | Gene Locus | Overlap Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | TREX1 | up-regulated | ssc13:31179291-31180747 | 1211 |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | CDHR4 | ssc13:32322034-32329337 | 2646 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | UBA7 | ssc13:32332367-32341217 | 3162 | |

| ecc_sus_9559 | ssc18:7500811-7501075 | ENSSSCG00000016475 | ssc18:7421004-7580571 | 264 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | GHSR | ssc13:110983298-111038324 | 7847 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | KCTD6 | ssc13:40167717-40219838 | 2259 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | ENSSSCG00000034614 | ssc13:35207145-35257795 | 5308 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | CISH | ssc13:33085286-33090858 | 2077 | |

| ecc_sus_31597 | ssc4:112113803-112114225 | ENSSSCG00000062186 | ssc4:112075073-112201596 | 422 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | CCR1 | down-regulated | ssc13:29227222-29233960 | 3021 |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | HRH1 | ssc13:67209127-67411170 | 4052 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | PTX3 | ssc13:97273594-97279569 | 1887 | |

| ecc_sus_19445 | ssc9:49740087-49740527 | UBASH3B | ssc9:49630793-49770897 | 440 | |

| ecc_sus_8665 | ssc16:76445891-76446106 | ADAMTS16 | ssc16:76326721-76491003 | 215 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | TNIK | ssc13:109643895-110052236 | 8855 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | ACKR2 | ssc13:26288584-26329581 | 7187 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | SRGAP3 | ssc13:65367608-65721405 | 8787 | |

| ecc_sus_13326 | ssc13:6028213-113199299 | RAB6B | ssc13:75012268-75075239 | 5528 | |

| ecc_sus_38422 | ssc6:140981157-151173884 | AK4 | ssc6:147177031-147257814 | 6813 |

| eccDNAs ID | eccDNAs Segment | Gene | FPKM | Gene Locus | Overlap Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | USH1C | up-regulated | ssc2:41593802-41647247 | 3579 |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | PEX11G | ssc2:71639301-71652903 | 4441 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | ZFP36 | ssc6:48063677-48066250 | 1761 | |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | ENSSSCG00000031706 | ssc2:47042505-47240103 | 9894 | |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | BST2 | ssc2:60305283-60309697 | 1458 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | MYLK3 | ssc6:37850754-37920754 | 4932 | |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | KLF2 | ssc2:61270199-61273138 | 2256 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | ENSSSCG00000047099 | ssc6:12221270-12223375 | 2106 | |

| ecc_sus_12446/ ecc_sus_36384 | ssc7:54689073-54689459/ ssc7:54689071-54689419 | ABHD2 | down-regulated | ssc7:54655804-54770131 | 386/348 |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | SLC7A10 | ssc6:43002431-43017554 | 1869 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | GGN | ssc6:47297575-47301553 | 3216 | |

| ecc_sus_19909/ ecc_sus_8330 | ssc17:51172371-51172836/ ssc17:51172368-51172836 | PTGIS | ssc17:51153154-51200300 | 465/468 | |

| ecc_sus_25923 | ssc3:73896006-73896978 | PLEK | ssc3:73877743-73906667 | 972 | |

| ecc_sus_38878 | ssc8:73887871-73889045 | FRAS1 | ssc8:73502717-73957375 | 1174 | |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | TMEM59L | ssc2:59210792-59223202 | 2484 | |

| ecc_sus_24348 | ssc2:34161240-73232708 | COMP | ssc2:59061426-59069564 | 3022 | |

| ecc_sus_22863/ ecc_sus_9710 | ssc2:74816329-74817223/ ssc2:74816071-74816394 | ATCAY | ssc2:74800048-74838671 | 894/323 | |

| ecc_sus_24348/ ecc_sus_22708 | ssc2:34161240-73232708/ ssc2:68745326-68746000 | OLFM2 | ssc2:68734081-68807191 | 2297/674 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | KCTD15 | ssc6:43529806-43544186 | 2878 | |

| ecc_sus_6299 | ssc11:12110009-12110582 | DCLK1 | ssc11:11815357-12158826 | 573 | |

| ecc_sus_35206 | ssc6:10037381-48166072 | SPRED3 | ssc6:47298634-47310181 | 2736 | |

| ecc_sus_20701 | ssc18:13583492-13583857 | FAM180A | ssc18:13575527-13592344 | 365 | |

| ecc_sus_23489 | ssc2:117841533-117843133 | NREP | ssc2:117838660-117867801 | 1600 | |

| ecc_sus_9862 | ssc4:104147899-104150211 | IGSF3 | ssc4:103994390-104166988 | 2312 | |

| ecc_sus_12823 | ssc7:116708508-116708756 | SYNE3 | ssc7:116665435-116770302 | 248 | |

| ecc_sus_11533 | ssc6:89086144-89086537 | KIAA1522 | ssc6:89058808-89087839 | 393 | |

| ecc_sus_2392 | ssc11:70217219-70217727 | ITGBL1 | ssc11:70042232-70246968 | 508 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).