1. Introduction

Platichthys stellatus is a species of significant economic value currently undergoing active aquaculture development in Korea. Compared to other farmed fish such as olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus), P. stellatus has been less extensively studied and is often found in natural habitats. However, its high commercial value has led to its recognition as an essential aquaculture species [

1,

2,

3]. Unlike in natural environments, pigmentation anomalies such as darkening of the ventral skin occur during aquaculture processes, causing substantial economic losses [

4,

5]. Although various studies have been conducted to identify the causes of these pigmentation anomalies, large-scale genetic studies to discover the underlying genes remain lacking. Additionally, transcriptome-level studies to explore gene expression changes associated with pigmentation anomalies and their progression during the growth of P. stellatus have been limited due to insufficient genomic information and the need for large-scale research [

6,

7].

In recent years, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has emerged as a key tool in genomic research [

8,

9,

10]. This technology offers significant advantages over traditional Sanger sequencing, including drastically reduced costs (less than 1/100) and the ability to rapidly sequence large volumes of data. NGS is widely applied in fields such as biological research, medicine, and diagnostics [

11,

12]. Among NGS technologies, RNA-seq has become a revolutionary tool for transcriptome analysis, replacing traditional microarray techniques. RNA-seq enables the identification of gene expression levels and differences without prior gene sequence information, making it highly suitable for transcriptome studies [

13,

14].

This study aims to utilize RNA-seq de novo assembly technology to identify genetic sequences in P. stellatus and uncover the genes responsible for pigmentation anomalies during aquaculture. Brain samples from normal, albino, and melanistic individuals were collected and analyzed using RNA-seq. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) specific to each condition were identified to establish candidate gene sets for further investigation. The results of this study are expected to contribute valuable genomic resources for research on pigmentation variation and aquaculture development in P. stellatus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

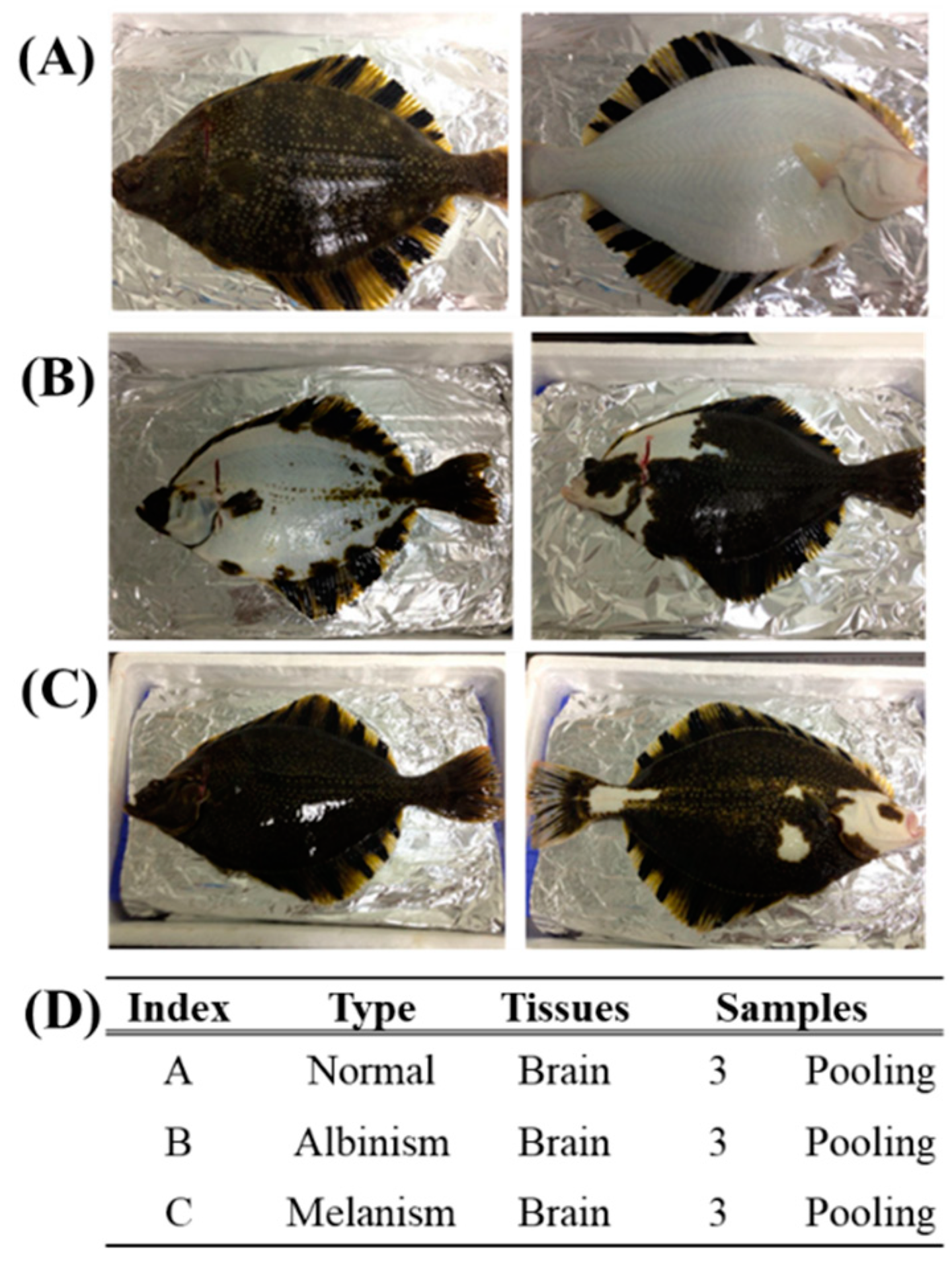

Samples from P. stellatus were categorized into three groups: normal, albino, and melanistic. Brain tissues were selected for transcriptome analysis (

Figure 1). To minimize RNA degradation, samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after dissection, including the pituitary gland. Each group included three male individuals to standardize comparisons.

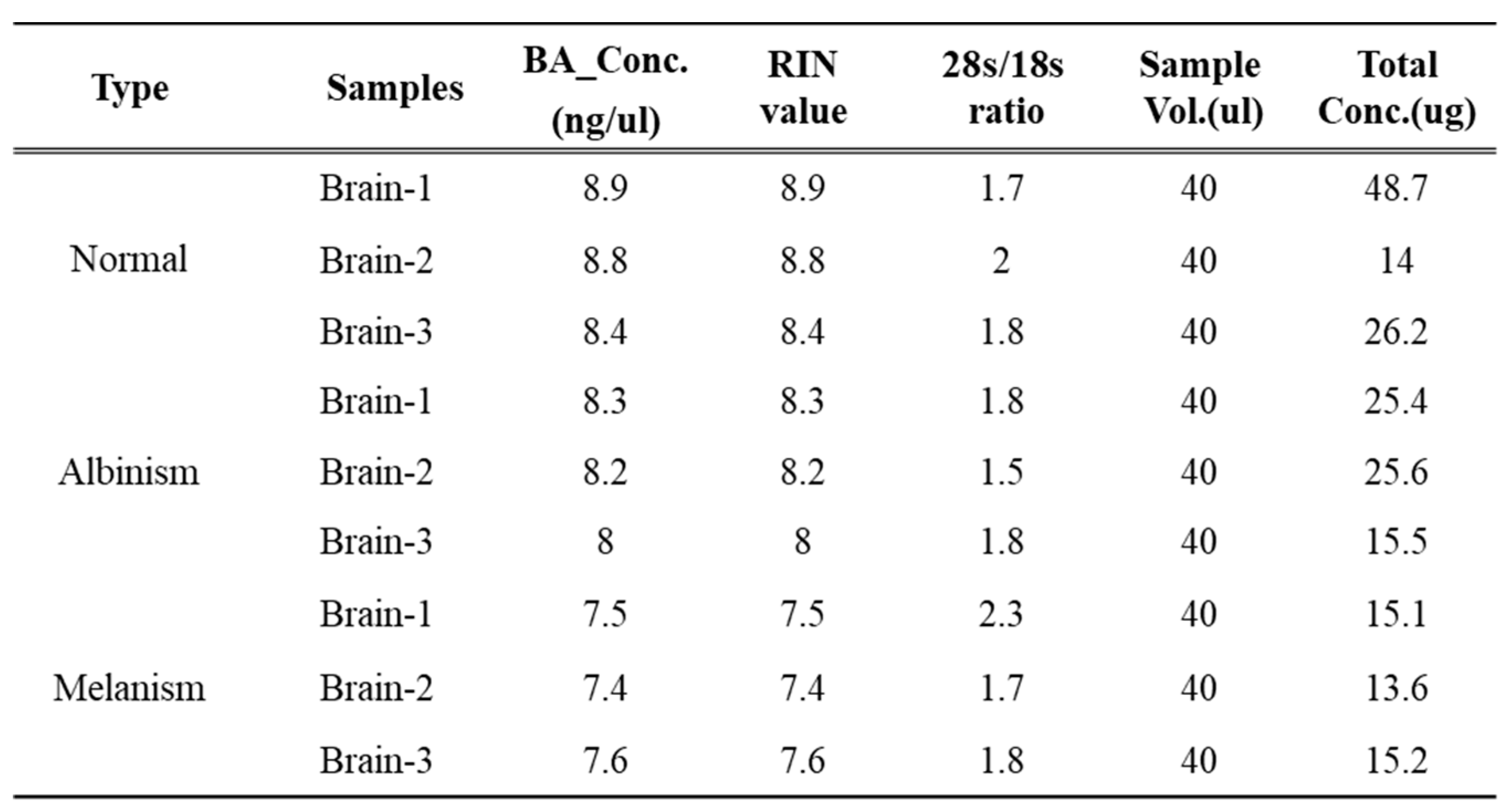

2.2. RNA Extraction and Library Preparation

RNA was extracted from brain tissues using Qiagen’s Tissuelyser for tissue homogenization. The homogenized tissue was treated with Trizol reagent, followed by chloroform addition and vortexing. After centrifugation, the aqueous phase was collected, and RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol, resuspended in RNase-free water, and analyzed using Agilent’s 2100 BioAnalyzer. RNA quality was evaluated using three metrics: BA Concentration (ng/µl), RIN (RNA Integrity Number), and 28s/18s ratio. Only samples with RIN values ≥7 were used for RNA-seq experiments (

Table 1). Libraries were prepared using Illumina’s TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit, with paired-end reads of 100 bp. mRNA was fragmented and reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA, followed by the synthesis of double-stranded cDNA. The cDNA was end-repaired, A-tailed, and adapter-ligated, then amplified by PCR. Libraries were quantified using KAPA Library Quantification Kit and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

2.3. NGS Data Analysis: Filtering, Assembly, and Clustering

Low-quality sequences were removed based on the following criteria: reads with more than 10% ambiguous bases (N), reads with over 20% bases of Q20 quality or lower, and reads with an average quality score below Q20. Remaining sequences were trimmed to remove low-quality bases at both ends. De novo assembly was performed using Trinity [

15,

16], which involves three steps: Inchworm, Chrysalis, and Butterfly. Inchworm groups sequences into subgroups using overlapping k-mers. Chrysalis clusters contigs into de Bruijn graphs based on shared sequences, and Butterfly refines these graphs to predict transcripts. Clustering of assembled transcripts was conducted using the TIGR Gene Indices Clustering Tool (TGICL) [

17], which compares sequences to calculate similarities and clusters them at a threshold of 0.94 similarity. CAP3 [

18] was used to reconstruct cluster representative sequences.

2.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

DEG analysis was conducted using the TCC program with the DEGES/DESeq method. This method normalizes data iteratively to improve the accuracy of DEG identification. A p-value threshold of <0.001 was applied to identify significant DEGs.

2.5. Functional Analysis. Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG Pathway Analysis

DEG analysis was conducted using the TCC program with the DEGES/DESeq method. This method normalizes data iteratively to improve the accuracy of DEG identification. A p-value threshold of <0.001 was applied to identify significant DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO) categorizes gene functions into Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). GO annotation for tissue-specific genes was based on the highest homology in RefSeq sequences. GO frequency and trend analyses were performed using DAVID [

22]. KEGG pathway analysis identifies the biological pathways associated with differentially expressed genes. Fisher’s exact test [

23] was used to calculate probabilities for pathway enrichment. Pathways significantly associated with tissue-specific DEGs were identified using DAVID.

3. Results

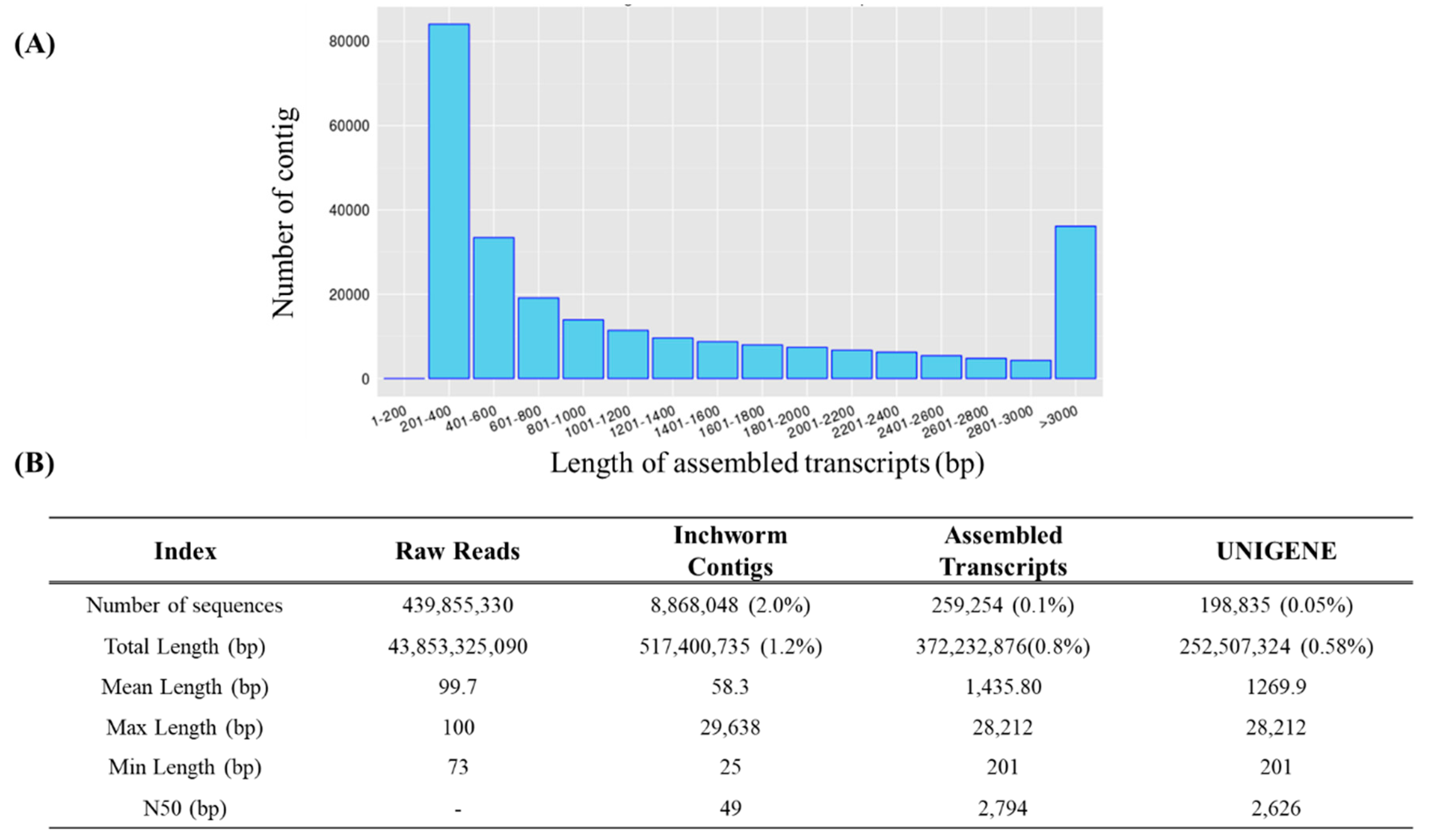

3.1. RNA-Seq De Novo Assembly

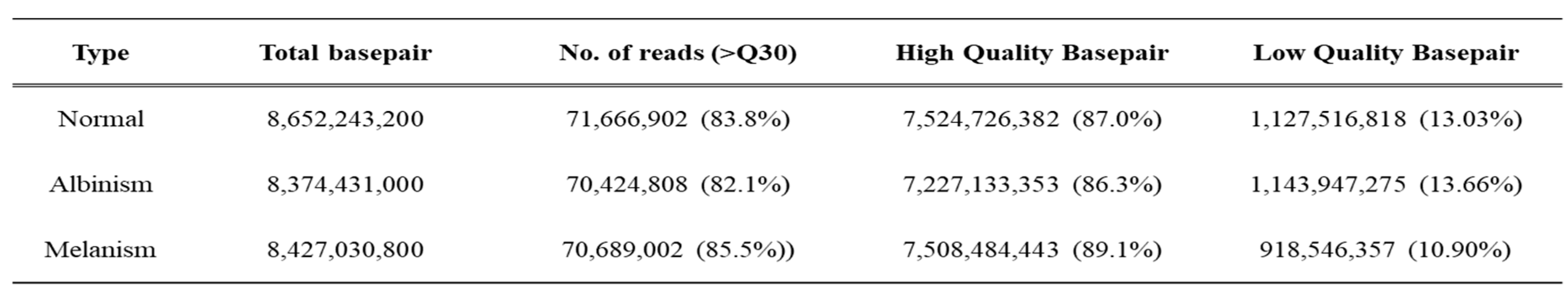

The high-quality base ratio obtained through sequence filtering was lowest in albino-brain samples at 86.3%, while melanistic-brain samples showed the highest quality at 89.1% (

Table 2). The total base sequence produced was 43.8 Gbp, which was reduced by 1.2% to 517 Mbp during the Inchworm process and further reduced to 0.8% (372 Mbp) in the final stage. The number of sequences decreased from 439,855,330 to 8,868,048 after the Inchworm process and ultimately to 259,254 (0.1%). The average sequence length was 1,435.8 bp, with a maximum length of 28,212 bp (

Figure 2B). The length distribution of the assembled transcripts is shown in

Figure 2A. Among the assembled transcripts, 84,084 (32.43%) were between 201–400 bp in length, while 36,132 (13.94%) were over 3,000 bp. To confirm unigene sequences, redundancy in the assembled transcripts was removed through a clustering method. After clustering, the total number of sequences decreased from 259,254 to 198,835. This indicates that 77% of transcripts assembled by Trinity were retained, while 23% were removed as redundant. On a nucleotide basis, 372.2 Mbp was reduced to 252.5 Mbp, indicating a 32% reduction (

Figure 2B).

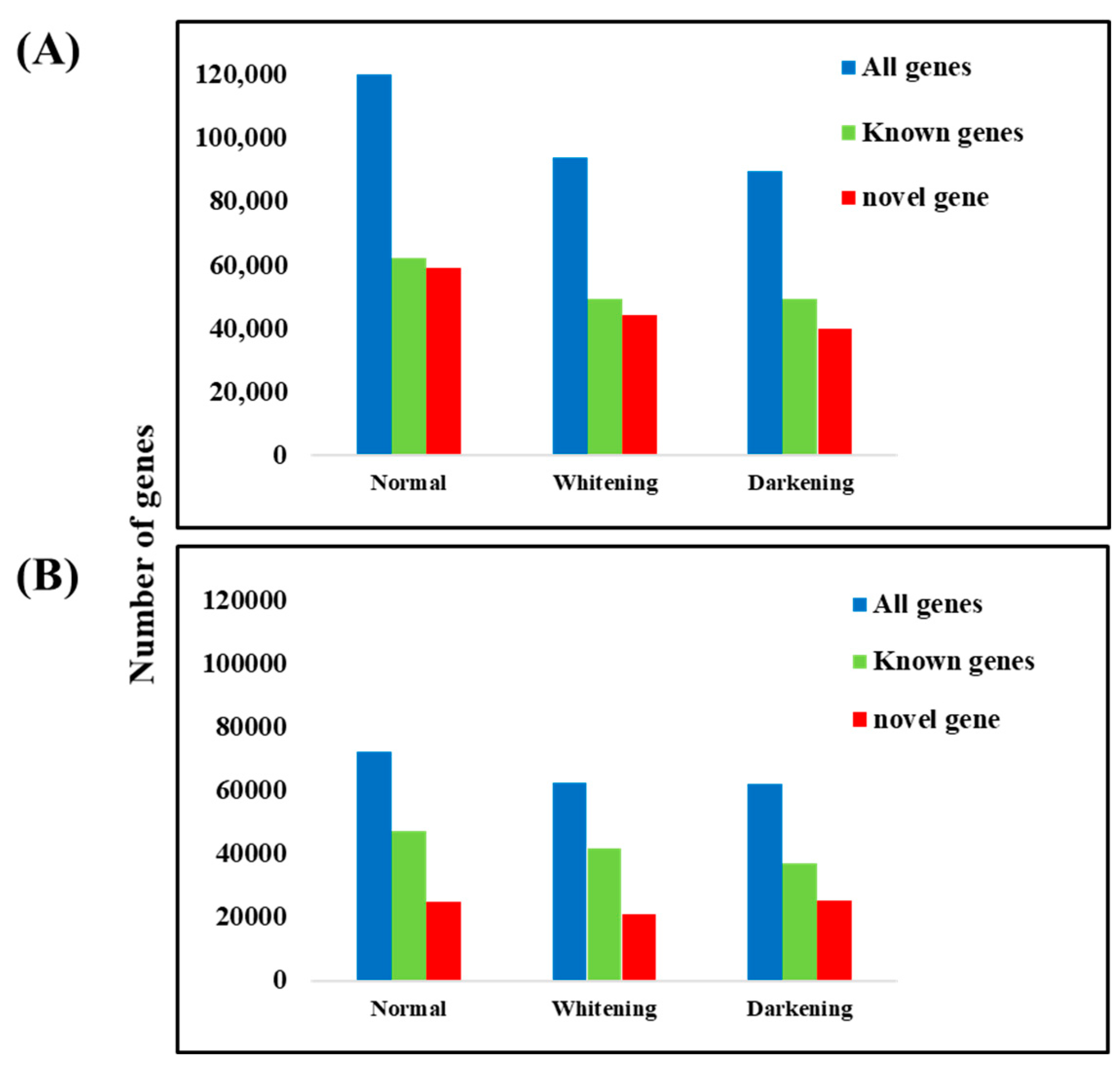

3.2. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

Out of 198,853 unigenes, the number of genes expressed in normal brain tissue was 121,617, consisting of 59,239 novel genes and 62,379 known genes. Genes expressed with an FPKM value of ≥1 totaled 72,102, including 24,740 novel genes and 47,362 known genes. In albino brain tissue, 93,850 genes were expressed, with 44,329 novel genes and 49,521 known genes. Genes expressed with an FPKM value of ≥1 totaled 62,485, including 20,824 novel genes and 41,661 known genes. In melanistic brain tissue, 98,555 genes were expressed, consisting of 40,103 novel genes and 49,452 known genes. Genes expressed with an FPKM value of ≥1 totaled 62,156, including 25,187 novel genes and 36,969 known genes (

Figure 3).The high-quality base ratio obtained through sequence filtering was lowest in albino-brain samples.

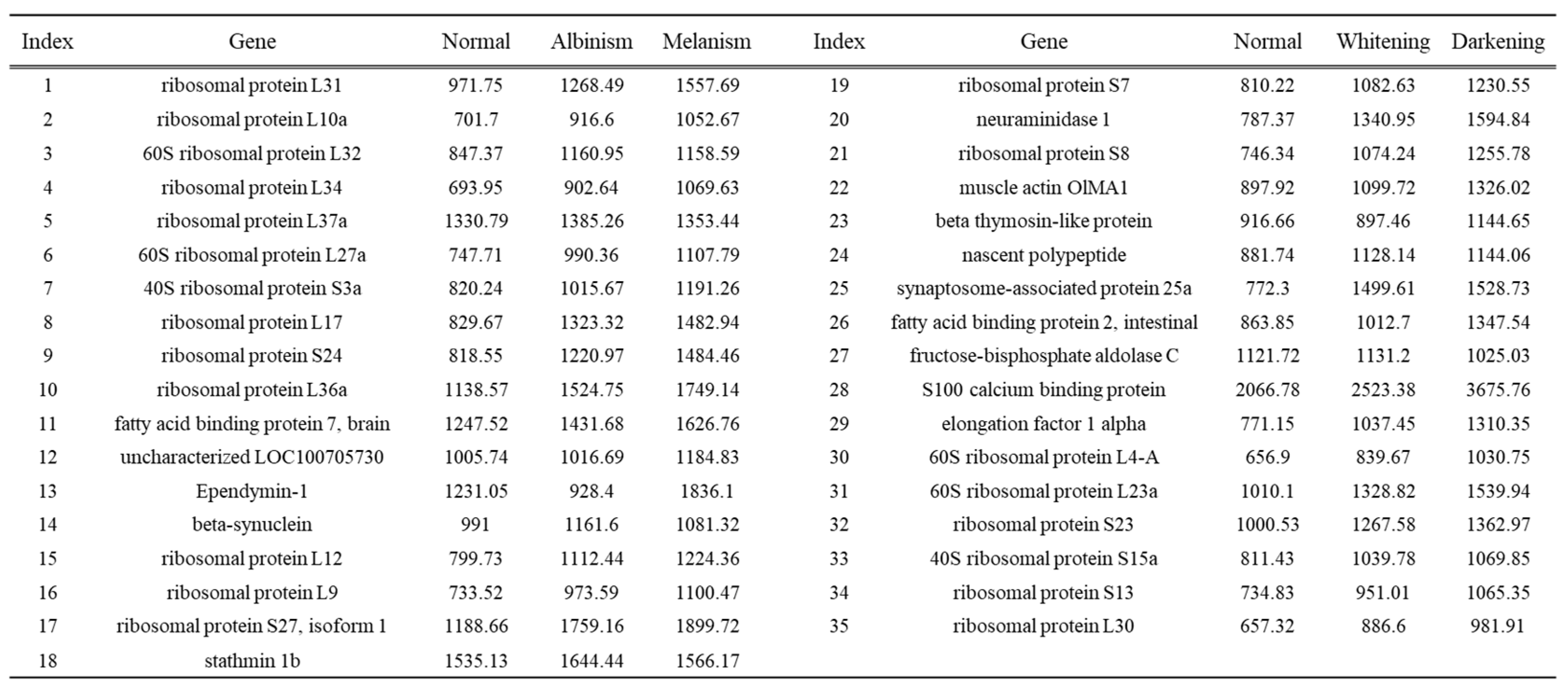

3.3. Commonly Expressed Genes in Brain Tissue

Among the highly expressed genes in normal, albino, and melanistic brain tissues, 35 genes were found to be expressed across all three groups (

Table 3). Most of these genes were ribosomal proteins, along with fatty acid binding protein 7, brain (fabp7), ependymin 1, and s100 calcium binding protein, which are known to be expressed in brain tissue.

3.4. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

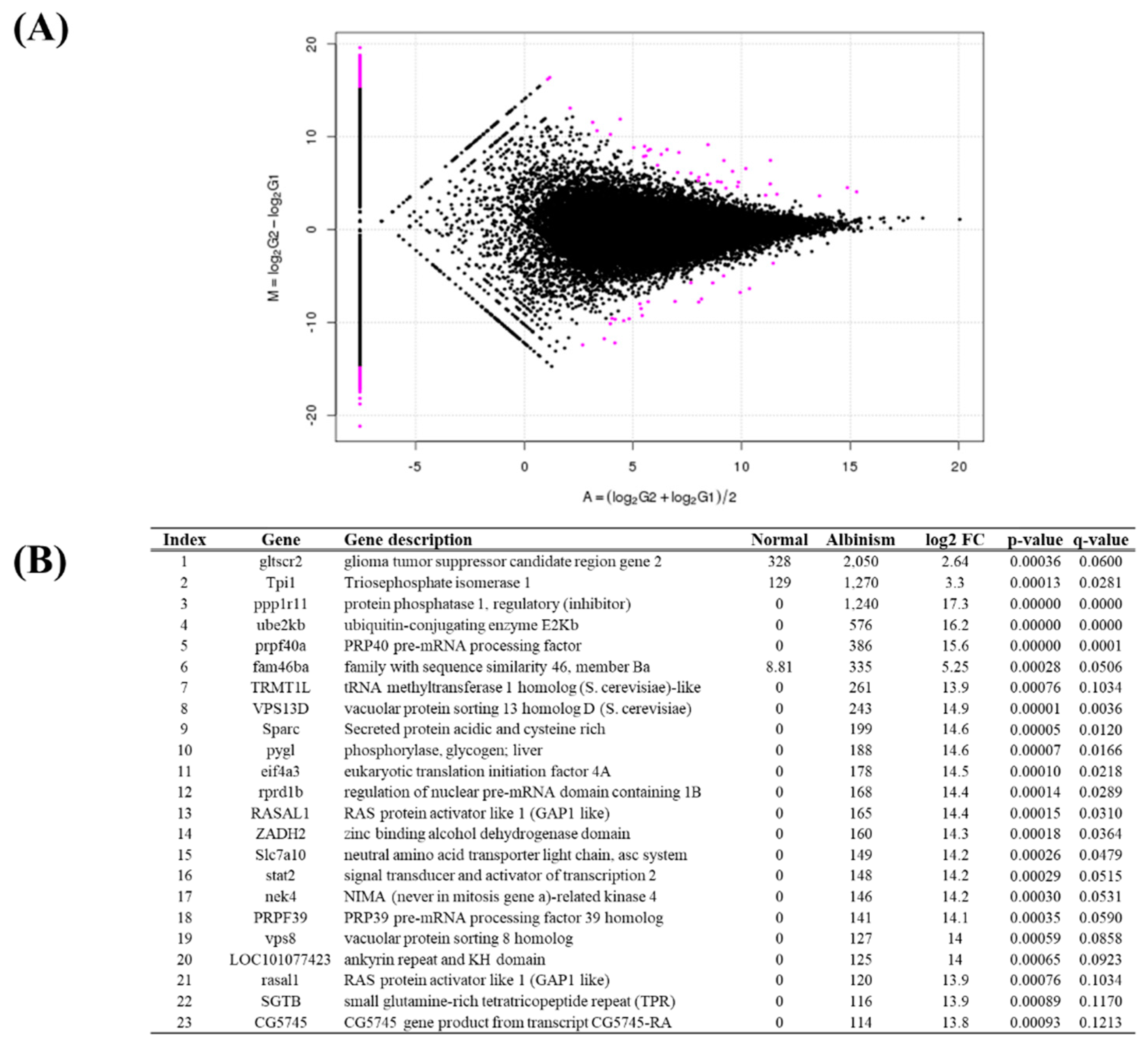

A total of 1,053 DEGs were identified between normal and albino brain tissues (

Figure 4A). Of these, 517 genes were upregulated, and 536 genes were downregulated in albino tissue compared to normal tissue. Among DEGs, 824 were expressed in only one sample group. The top 23 statistically significant DEGs were selected. The most significantly upregulated genes in albino brain tissue were gltscr2, ODZ1, and ppp1r11 (

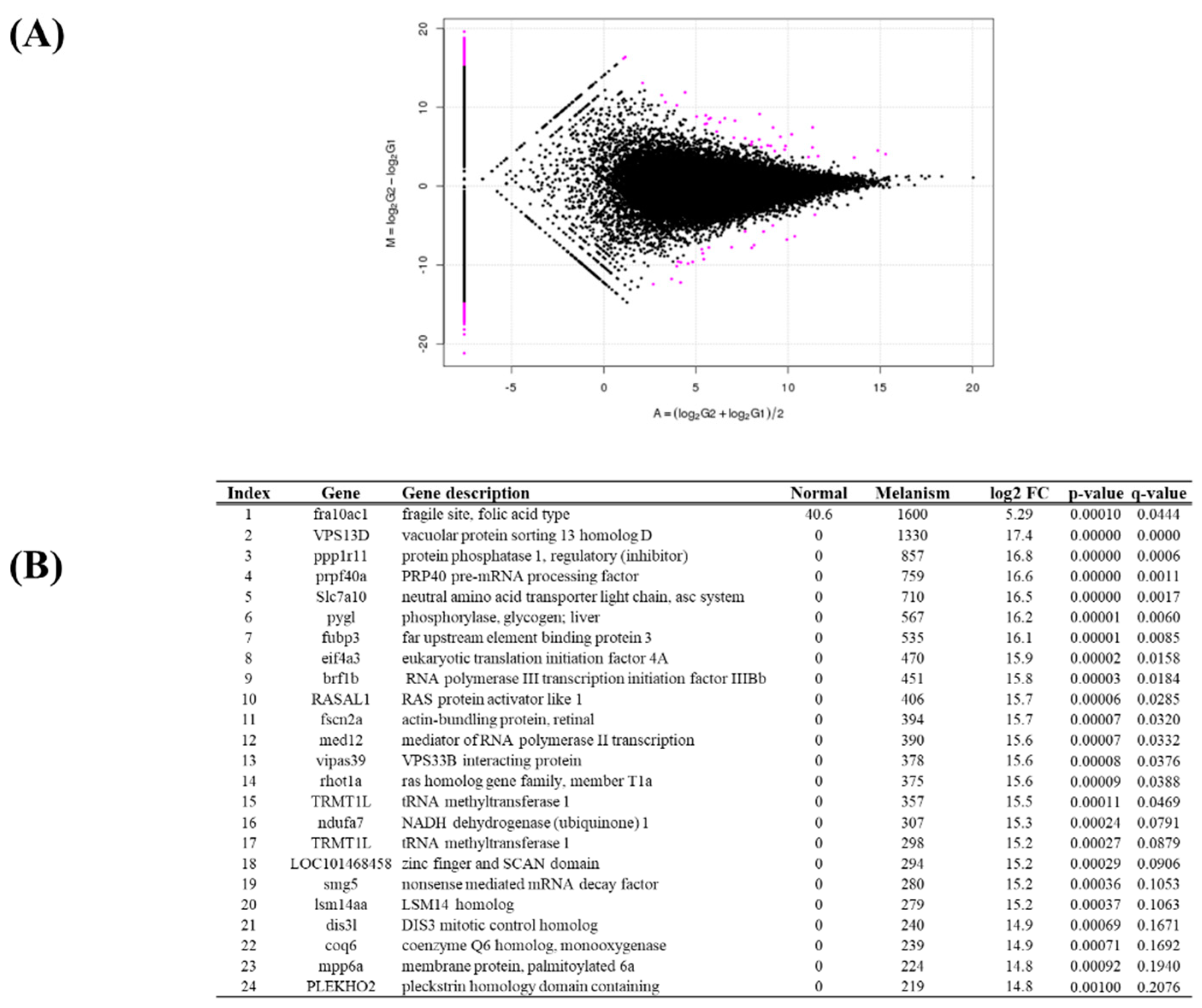

Figure 4B). Between normal and melanistic brain tissues, 642 DEGs were identified, consisting of 335 upregulated genes and 307 downregulated genes. Genes expressed in only one tissue group totaled 514. The top 24 statistically significant DEGs were selected (

Figure 5A). The most highly expressed genes in melanistic brain tissue included fra10ac1, VPS13D, and ppp1r11 (

Figure 5B).

3.5. Gene Ontology and KEGG Pathway Analysis

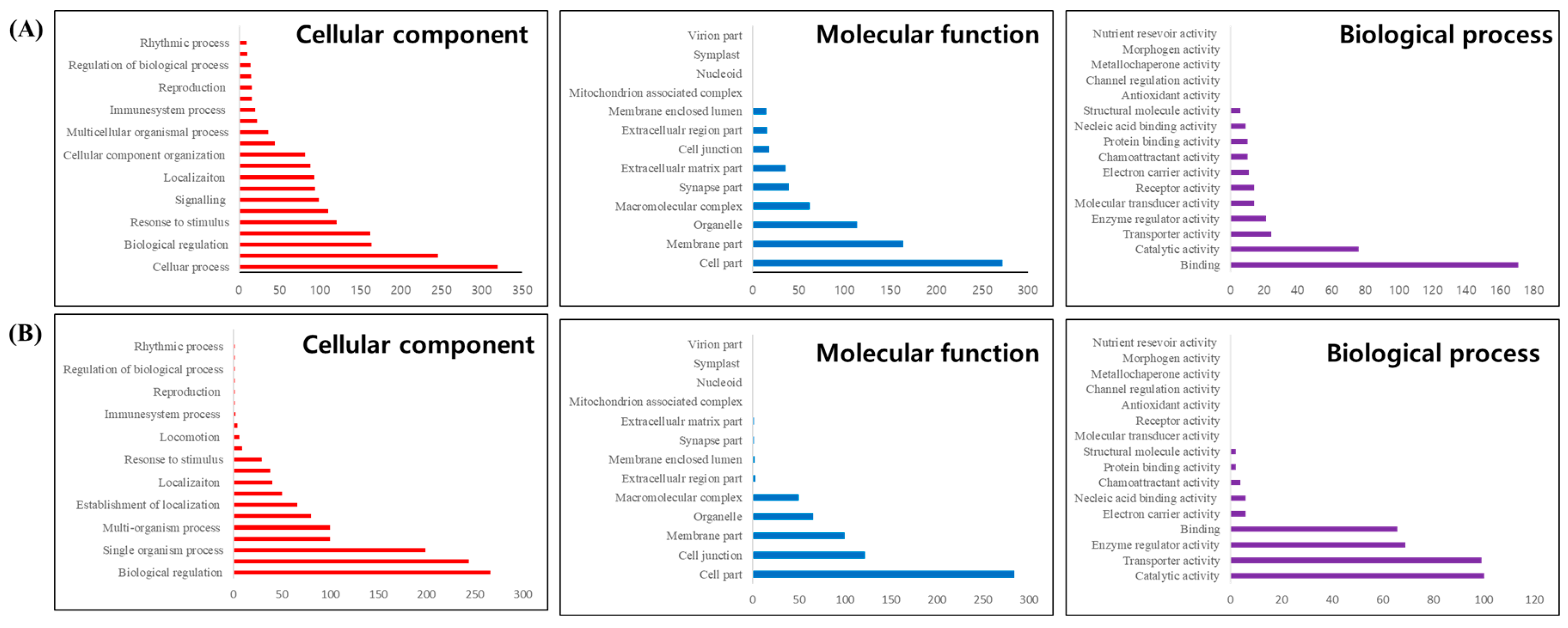

GO frequency analysis of the 1,053 DEGs identified between normal and albino brain tissues revealed changes in gene expression related to genetic functions. In the Biological Process (BP) category, cellular process was the most frequent, followed by biological regulation and response to stimulus (

Figure 6A). In the Cellular Component (CC) category, cell part had the highest frequency, followed by membrane part and organelle (

Figure 6A). In the Molecular Function (MF) category, binding was the most frequent, followed by catalytic activity (

Figure 6A). Additional GO trend analysis using DAVID revealed 34 significant GO categories (p-value < 0.01), including mRNA metabolic process, synapse, and RNA helicase activity (Supplementary Table S1).

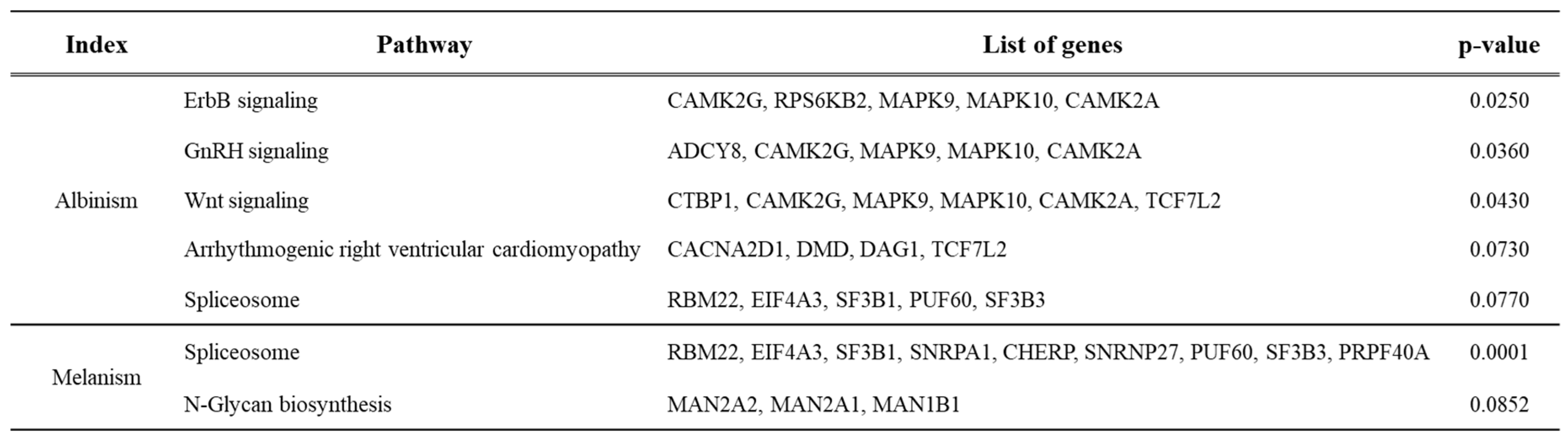

Pathway analysis of genes expressed in normal and albino brain tissues identified five significant pathways (p-value < 0.10): ErbB signaling pathway, GnRH signaling, Wnt signaling, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and spliceosome pathway. Each pathway involved 4–6 related genes (Table 4, Supplementary Figures S1–S5). Pathway analysis of genes expressed in normal and melanistic brain tissues identified two significant pathways (p-value < 0.10): spliceosome and N-glycan biosynthesis pathways. These involved 9 and 3 related genes, respectively (Table 4, Supplementary Figures S6 and S7).

Table 3.

KEGG pathway analysis showing trends in gene expression changes and lists of genes for normal vs. melanistic and normal vs. albino brain tissues.

Table 3.

KEGG pathway analysis showing trends in gene expression changes and lists of genes for normal vs. melanistic and normal vs. albino brain tissues.

4. Discussion

Platichthys stellatus is a high-value aquaculture species in Korea, with pigmentation playing a significant role in market quality [

2,

24]. This study conducted transcriptome analysis to investigate mechanisms underlying pigmentation variation. While recent studies have explored tissue-specific expression patterns of mRNA and miRNA in fish, genetic evidence for albinism and melanism in P. stellatus remains limited [

25,

26].

High-quality RNA-seq technology enables extensive monitoring of genetic changes due to environmental or external stress [

27,

28]. This study achieved high-quality sequencing through rapid runs, generating over 8 Gb of sequence data per brain tissue sample (

Table 2). A total of 198,853 unigenes were constructed, serving as a foundational database for analyzing expression differences in normal, albino, and melanistic brain tissues, with 121,617, 62,485, and 98,555 genes identified, respectively (

Figure 3).

Normal pigmentation in P. stellatus is essential for survival in natural environments. Albinism, a complex and permanent condition in flatfish, leads to irregular pigmentation, reduced UV protection, and increased vulnerability to environmental stress [

31]. Additionally, albinism adversely affects immune function, increasing susceptibility to disease [

32]. Many studies report reduced survival in pigment-deficient fish compared to normal individuals [

33,

34]. Moreover, albinism in aquaculture negatively impacts public perception of fisheries management [

35,

36]. The transcriptome of albino P. stellatus identified genes differentially expressed in pigmentation-related processes and responses to environmental stress (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). This study also highlighted endocrine metabolic pathways related to pigmentation (

Table 4), with the Wnt signaling pathway emerging as a key factor in skin color changes [

37].

Genes related to pigmentation variation are often associated with vascular and muscle formation, hypoxia, and phosphorylation. Highly expressed genes in vascular formation include lumican (LUM), which plays a role in epithelial cell generation and collagen fiber organization [

38]. Notably, Sparc (secreted protein acidic and cysteine-rich) and TPI1 (triosephosphate isomerase 1), upregulated in albino tissues, are critical for skin regeneration and stress response in fish (

Figure 5). Sparc’s upregulation may reflect compensatory mechanisms to mitigate pigment loss due to environmental stress. Increased TPI1 expression likely responds to elevated energy demands under stress [

40]. Additional upregulated genes (gltscr2, ppp1r11, fra10ac1, VPS13D) may indirectly impact pigmentation by influencing oxidative mechanisms, cell proliferation, and apoptosis, potentially affecting growth and disease susceptibility [

41]. These genes are also implicated in skin aging, UV response, DNA repair, and cell death, underscoring their role in stress response.

5. Conclusion

This study utilized RNA-seq de novo assembly to identify candidate genes in P. stellatus associated with pigmentation variation. Over 20 Gbp of reference data were generated from brain tissues of three groups (normal, albino, melanistic), resulting in approximately 198,853 unigenes. Differential expression analysis identified genes associated with pigmentation-specific characteristics, supported by GO and pathway analyses. These findings provide foundational knowledge for future studies on P. stellatus and contribute to understanding pigmentation mechanisms in aquaculture species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; Methodology, J.H. and D.K.; Field investigation, J.H.; Software, J.H; Writing-original draft preparation, J.H.; Writing-review and editing. D.K.; Project administration. D.K All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported the National Institute of Fisheries Science (NIFS), Incheon, Republic of Korea. (R2024057)

Institution Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cho, J.-H.; Hamidoghli, A.; Hur, S.-W.; Lee, B.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.-W.; Lee, S. Growth, Nutrient Deposition, Plasma Metabolites, and Innate Immunity Are Associated with Feeding Rate in Juvenile Starry Flounder (Platichthys stellatus). Animals 2024, 14, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.-C.; Kim, J.-H.; Kang, J.-C. Toxic Impact of Dietary Cadmium on Bioaccumulation, Growth, Hematological Parameters, Plasma Components, and Antioxidant Responses in Starry Flounder (Platichthys stellatus). Fishes 2024, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.S.; Nam, M.M.; Myeong, J.I.; An, C.M. Genetic diversity and differentiation of the Korean starry flounder (Platichthys stellatus) between and within cultured stocks and wild populations inferred from microsatellite DNA analysis. Molecular biology reports 2014, 41, 7281–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhawa, A.D.; Tandel, S.; Chellapan, A.; V, A.K.; Kumar, R. First Record of Hyperpigmentation in a Unicorn Cod, Bregmaceros Mcclellandi Thompson, 1840 (Gadiformes: Bregmacerotidae), From the North-west Coast of India. Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences 2021, 37, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-Y.; Kim, H.-C. Functional relation of agouti signaling proteins (ASIPs) to pigmentation and color change in the starry flounder, Platichthys stellatus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2024, 291, 111524. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Pattern of new gene origination in a special fish lineage, the flatfishes. Genes 2021, 12, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.M.; Jang, H.S.; Park, J.Y.; bin Lee, H.; Lim, H.K. Effects of Environmental Factors on the Eye Direction in Juvenile Starry Flounder Platichthys stellatus. Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2024, 57, 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- Piredda, R.; Mottola, A.; Cipriano, G.; Carlucci, R.; Ciccarese, G.; Di Pinto, A. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) approach applied to species identification in mixed processed seafood products. Food Control 2022, 133, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G. Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Oliveira, J.; Sousa, M. Bioinformatics and computational tools for next-generation sequencing analysis in clinical genetics. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteche-López, A.; Ávila-Fernández, A.; Romero, R.; Riveiro-Álvarez, R.; López-Martínez, M.; Giménez-Pardo, A.; Vélez-Monsalve, C.; Gallego-Merlo, J.; García-Vara, I.; Almoguera, B. Sanger sequencing is no longer always necessary based on a single-center validation of 1109 NGS variants in 825 clinical exomes. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surányi, B.B.; Zwirzitz, B.; Mohácsi-Farkas, C.; Engelhardt, T.; Domig, K.J. Comparing the efficacy of MALDI-TOF MS and sequencing-based identification techniques (Sanger and NGS) to monitor the microbial community of irrigation water. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidian, A.H.; Youssefian, L.; Vahidnezhad, H.; Uitto, J. Research techniques made simple: whole-transcriptome sequencing by RNA-seq for diagnosis of monogenic disorders. Journal of investigative dermatology 2020, 140, 1117–1126.e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, A.; Shukla, A.; Jaiswar, A.; Shrinet, J.; Jasrotia, R.S. Applications and challenges of microarray and RNA-sequencing. Bioinformatics 2022, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nature biotechnology 2011, 29, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.J.; Papanicolaou, A.; Yassour, M.; Grabherr, M.; Blood, P.D.; Bowden, J.; Couger, M.B.; Eccles, D.; Li, B.; Lieber, M. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature protocols 2013, 8, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, G.; Huang, X.; Liang, F.; Antonescu, V.; Sultana, R.; Karamycheva, S.; Lee, Y.; White, J.; Cheung, F.; Parvizi, B. TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 651–652. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Madan, A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome research 1999, 9, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Nishiyama, T.; Shimizu, K.; Kadota, K. TCC: an R package for comparing tag count data with robust normalization strategies. BMC bioinformatics 2013, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Nature Precedings 2010, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Kadota, A.; Fujisawa, K.; Sawada-Satoh, S.; Wajima, K.; Doi, A. An Intrinsic Short-Term Radio Variability Observed in PKS 1510− 089. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 2012, 64, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R.L.; Shreeve, T.G.; Van Dyck, H. Towards a functional resource-based concept for habitat: a butterfly biology viewpoint. Oikos 2003, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, B. Fisher’s historic 1922 paper On the dominance ratio. Genetics 2022, 220, iyac006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, W.-J.; Kim, H.-C. Morphological specificity in cultured starry flounder Platichthys stellatus reared in artificial facility. Fisheries and aquatic sciences 2012, 15, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.-A.; Choi, C.Y.; Kang, J.-C.; Kim, J.-H. Effects on lethal concentration 50% hematological parameters and plasma components of Starry flounder, Platichthys stellatus exposed to hexavalent chromium. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2024, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.H.; Park, M.S.; Myeong, J.-l. Stress responses of starry flounder, Platichthys stellatus (Pallas) following water temperature rise. Journal of Environmental Biology 2015, 36, 1057. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.B.; Yoon, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, I.Y.; Lim, H.K. A comparison of the physiological responses to heat stress of juvenile and adult starry flounder (Platichthys stellatus). Israeli Journal of Aquaculture-Bamidgeh 2021, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chung, J.S.; Yoon, J.; Park, J.Y.; Lim, H.K. Understanding Heat-Associated Adult Platichthys stellatus Mortality: Differential Transcriptome Analysis of Juvenile and Adult Starry Flounder Liver under Heat Stress. Aquaculture Research 2024, 2024, 9980817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johal, K.S.; Saour, S.; Mohanna, P.-N. The skin and subcutaneous tissues. In Browse’s Introduction to the Symptoms & Signs of Surgical Disease; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 111–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasquete, C.; Gisbert, E.; Ortiz-Delgado, J. Embryonic and larval ontogeny of the Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis: normal patterns and pathological alterations. In The Biology of Sole; CRC Press, 2019; pp. 216–252. [Google Scholar]

- Blandon, I.R.; DiBona, E.; Battenhouse, A.; Vargas, S.; Mace, C.; Seemann, F. Analysis of the Skin and Brain Transcriptome of Normally Pigmented and Pseudo-Albino Southern Flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma) Juveniles to Study the Molecular Mechanisms of Hypopigmentation and Its Implications for Species Survival in the Natural Environment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7775. [Google Scholar]

- Svitačová, K.; Slavík, O.; Horký, P. Pigmentation potentially influences fish welfare in aquaculture. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2023, 262, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.K.; Kumar, A.T.; Balasubramanian, T. Pigment deficiency correction in captive clown fish, amphiprion ocellaris using different carotenoid sources. Journal of FisheriesSciences. com 2016, 10, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bolker, J.A.; Hill, C. Pigmentation development in hatchery-reared flatfishes. Journal of Fish Biology 2000, 56, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Schaerlinger, B.; Żarski, D. Evaluation and improvements of egg and larval quality in percid fishes. Biology and Culture of Percid Fishes: Principles and Practices 2015, 193–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bernáth, G.; Csenki, Z.; Bokor, Z.; Várkonyi, L.; Molnár, J.; Szabó, T.; Staszny, Á.; Ferincz, Á.; Szabó, K.; Urbányi, B. The effects of different preservation methods on ide (Leuciscus idus) sperm and the longevity of sperm movement. Cryobiology 2018, 81, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, H.; Miguez-Macho, G. Global patterns of groundwater table depth. Science 2013, 339, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, S.; Larjava, H.; Häkkinen, L. Distinctive localization and function for lumican, fibromodulin and decorin to regulate collagen fibril organization in periodontal tissues. Journal of periodontal research 2005, 40, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Núñez, E. Sparc (Osteonectin): new insight into the function and regulation= Sparc (Osteonectin): nuevos conocimientos sobre sus funciones y regulación. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Shu, H.; Zhong, D.; Zhang, M.; Xia, J.H. Effect of fasting and subsequent refeeding on the transcriptional profiles of brain in juvenile Spinibarbus hollandi. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0214589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-C.; Dong, H.-J.; Wang, P.; Meng, W.; Chi, X.-J.; Han, S.-C.; Ning, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.-J. Cellular protein GLTSCR2: a valuable target for the development of broad-spectrum antivirals. Antiviral Research 2017, 142, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).