1. Introduction

Alcoy, with 65,000 inhabitants, is a city in Alicante (Spain) with a long tradition in the textile industry. Since the 15th century, it has excelled in the manufacture of textile products such as blankets, carpets, woollen fabrics and industrial fabrics, which boosted its economic development.the rigour of the trade is evident in the rules of the guild that document the minimum quality that a product must meet.it was in the Casa de la Bolla where the quality and finishes of textile fabrics were certified.the ‘bolla’ was the seal of guarantee with which the pieces were marked, so that they could be marketed with the Alcoyano designation of origin.

At the beginning of the 19th century, King Charles IV granted it the title of Royal Cloth Factory (RFPA), becoming the first textile school of technical education: the Bolla School. After the anti-machine riots of the industrial revolution, the Ministry of Development granted it the status of Elementary Industrial School, sponsored by the Royal Cloth Factory, under the conviction that an improvement in the cultural level and training of the workers could overcome the resistance by training them in the use of machines. At the end of the century, the school moved to a new building and the School of Arts and Crafts was created, which was the forerunner of the Industrial School (1903), which in turn became the Higher Polytechnic School of Alcoy (1972), which today is the Alcoy Campus of the Polytechnic University of Valencia.

The Royal Cloth Factory of Alcoy (RFPA) acted as an organisation ahead of its time. Thus, from the second half of the 18th century, it undertook a determined policy of renovation and industrialisation, promoting contracts with foreign technicians and experts in dyeing processes and equipment, as well as sending commissioners to different places in order to introduce innovations and incorporate new spinning machinery.

However, at the end of the 20th century, the textile industry in Alcoy, as in other parts of Spain and Europe, began to suffer a crisis due to foreign competition and changes in production methods, such as outsourcing to less developed countries. Despite this decline, and with the help of state funds, the Instituto Tecnológico Textil AITEX (1985) was created. It belongs to the Spanish Federation of Innovation and Technology Entities (FEDIT), to the Network of Technological Institutes of the Valencian Community (REDIT). It is currently the Research Association of the Textile and Cosmetics Industry, one of the five main centres in Europe, which provides advanced technical solutions and services to companies to adapt to new modes of production in order to modernise their processes and access more specialised market niches.

Historically, the textile and clothing sector has been one of the great economic engines of our country. Today, according to data from the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism, this industry is one of the five largest exporters in Spain, accounting for 6.1% of total sales abroad.

lthough this article focuses on the modernisation achieved, through the application of new technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) or Metaverse (MV), in the design of virtual stands useful in trade fairs and other promotional[

1,

2] activities applied to the textile sector, it is convenient to make a brief summary of essential aspects of their implementation in other fields.

There are many different sectors that are benefiting from VR and MV, both at a professional level and in terms of improving the user experience (UX). The tourism sector in general, virtual commercial spaces (clothing and accessories shops, opticians...), digital goods (NTF’s), the organisation of all kinds of events such as: trade fairs, art biennials, fashion shows, congresses, concerts), it is also important in the construction, architecture and interior design sectors.

In the case of tourism, it is an emerging concept that combines VR, AR, [

3,

8] and other digital elements to offer multi-sensory experiences in tourist destinations. This evolution of digital technologies allows for immersive virtual tours, experiences prior to the actual trip, receiving or providing personalised assistance through avatars or virtual assistants for itinerary planning, in short, it collaborates in the gamification of tourism.

The user can also participate in any event and/or congress. It is gradually being implemented as a tool for the promotion and marketing of many tourist destinations. The act of travelling is being modified by adding immersive experiences. A whole range of previously unknown experiences are presented, allowing visitors to discover territories and countries without having to travel at all. This fosters a kind of passive tourism, which has lost the capacity or possibilities of mobility, without losing interest in cultural diversity or even the need to escape from its immediate surroundings.

In the hospitality industry [

9,

12] particularly in luxury hotels, virtual planning and booking possibilities are beginning to multiply by offering virtual tours of the interior, exterior and surroundings of the hotel. Thus, guests can use AR to enhance their stay by obtaining additional information about restaurant menus, facilities, as well as accessing historical data and valuable information about the art and other treasures housed in the hotel itself. Of course, all of this is intended to enhance the stay of users and guests. In the hospitality industry, particularly in luxury hotels, virtual planning and booking possibilities are beginning to multiply by offering virtual tours of the interior, exterior and surroundings of the hotel. Thus, guests can use AR to enhance their stay by obtaining additional information about restaurant menus, facilities, as well as accessing historical data and valuable information about the art and other treasures housed in the hotel itself. Of course, all of this is intended to enhance the stay of users and guests.

We cannot fail to mention the possibilities that have arisen in the field of [

13] architecture, where architects and interior designers can explore and experiment with virtual environments (VE) without the physical constraints of the real world. In the MV, buildings and environments can be designed completely digitally. The fact that there is no obligation to consider physical laws frees the design process from the discipline-specific structural and economic constraints that these disciplines face on a daily basis. It offers the possibility of rethinking the concept of habitable and walkable space, so that projects can be more creative and highly experimental, as in the case of the Zaha Hadid Architects team who have designed experimental spaces in the MV through the Liberland platform for Decentraland.

Thus, architecture in the MV not only makes it possible to think, create and design digital spaces for virtual platforms, but also offers experiences of the prototypes and modelling of its projects to satisfy curiosity and anticipate the visit to the future home, thanks to the photorealistic finishes that these technologies allow.

On the other hand, it facilitates the evaluation, confrontation and validation of results through the possibilities of global connection, in real time, with any equipment and in any part of the world. Thus, some architectural offices and building construction companies have already implemented this technology to display building modelling information (BIM), the construction process and its subsequent monitoring. In addition, the MV serves as a test laboratory, where sustainability solutions can be experimented with and even new building technologies can be tested without the constraints of time, cost or environmental impact. For example, it is possible to design structures using sustainable materials and simulate the impact of their execution on the immediate surroundings and/or the environment, before materialising them in the real world.

It was to be expected that MV would influence the construction sector [

14] with its digital tools and solutions that can improve the design, planning, execution and maintenance stages of construction and traditional projects. However, although still at an early stage in this sector, the integration of MV-related technologies such as VR, AR, digital twins and 3D modelling is revolutionising the way construction companies approach projects. With digital twins, accurate virtual representations of a building or infrastructure in real time assist construction teams in the process before (predicting weather conditions and improving energy efficiency), during (visualising the construction process in an optimised way, anticipating problems to manage resources more efficiently and minimising costly mistakes) and after (monitoring the building for door opening, leak detection, alarm activation, etc.).

Linked to the previous sector, the design of events and other cultural spaces is beginning to mark professional paths among architects and interior designers, who are specialising in digital environments. Within the MV, cultural spaces and events such as museums, biennials, art galleries and concert halls are beginning to exist. These spaces allow the organisation of exhibitions, events and shows without the spatial, temporal or geographical limitations of the physical world. Examples include the catalogue of flexible architectural strategies linked to spaces detached from spatio-temporal limits presented at the 17th edition of the International Architecture Exhibition, which included the Biennale di Venezia 2020, and the virtual exhibitions designed specifically for visitors to the MV at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021. Both experiences propose new forms of coexistence, with broader and more ambitious environmental and social implications based on these technologies.

Smart glasses are used in these areas [

15]. Product development in the field of optics converges directly with MV. This technology is bringing about a comprehensive transformation in the optical sector [

16] offering solutions for both professionals and consumers. Devices such as Meta Quest (formerly Oculus), Ray-Ban Stories, Google Glass or Apple Vision Pro are bridging the gap between the physical and digital world.

Not only does it thrive on immersive shopping experiences (through VR and AR technologies, customers can enter optical shops in fully digital environments and behave as in a shop in reality), but it also proposes new forms of training (recreation of clinical scenarios for optical professionals) and advanced technologies such as smart glasses, the interaction between the optical and the MV opens up a number of opportunities to improve services and user experience.

On the other hand, marketing departments [

17,

20] use MV to encourage interactivity to test products before their final launch on the market. This growing trend leverages VE to connect with consumers. Thus, as platforms such as Decentraland, The Sandbox, and versions of MV developed by large technology companies such as Meta (formerly Facebook) gain popularity, attentive brands are exploring all the forms of interaction they have to offer. This type of marketing uses virtual experiences and interactive content to create advertising and other digital services installed within these decentralised spaces or scenarios [

21,

25].

One of the most popular forms of marketing in the VM is the virtual shop. Any brand can design 3D visitable retail spaces that can be accessed by all kinds of users through their avatars, to try out their products and make purchases that will then be delivered by courier to their real-life homes. Gucci, for example, is selling digital clothing on Roblox, while other luxury brands such as Balenciaga are launching digital collections within games such as Fortnite. This field is starting to deliver benefits, particularly in terms of loyalty. It has been proven that new ways of interacting with consumers and customers are more attractive because they are closer, more direct and more personalised [

26,

27].

These shops replicate and enhance the physical experience by allowing customers to explore all of their collections and purchase their products in real and virtual stores. Major brands such as Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren have opened the doors of their shops on the MV Decentraland platform, where avatars can walk through shops, try on clothes and buy them, both digitally and physically. Fashion shows on the MV allow brands to present their collections in a more accessible and democratised way.

One of the most innovative aspects of VR in apparel and accessory design is the emergence of digital fashion, where users can purchase and dress their avatars in garments and accessories that only exist in a given virtual environment. These digital assets, in the form of NFTs, are often exclusive and limited access, which increases their value within virtual reality and gaming platforms. We see how in 2023, Samsung offered a free skin within the game Fornite (See

Figure 1) for the purchase of its latest mobile model. Sales increased in this sector by 20

The very concept of the virtual environment leads to the sale of purely digital products, such as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) of art, fashion or any good that can be integrated and enjoyed in an immersive way. The trade of digital goods, such as NFTs or virtual products, of an exclusive nature, opens up new lines of business for brands, beyond physical products, thanks to a young audience familiar with the MV, especially popular among the Millennials generation and the so-called Generation Z or GenZ, with developed technological knowledge about virtual or augmented reality, compared to previous generations [

28,

30].

In parallel to this research, in the fashion industry [

31] the MV is offering new ways for the design-purchase interaction. Fashion brands are exploring how to leverage VR, AR, digital twins and immersive experiences to create new commercial opportunities and continually redefine the relationship between people and fashion. They are also developing virtual fitting experiences, where users can see how garments look on their bodies through AR technology. This is starting to be available both in online shops and within the MV platforms.

All of this also makes it possible to connect to industry events, so that users can attend all kinds of fashion shows, more or less exclusive, regardless of their physical location. Virtual fashion events [

32] including fashion shows, launches and exhibitions are already accessible to the global audience [

33] breaking down space-time barriers, displacing traditional events, seems to be their main goal.

For example, the Decentraland platform organised the first Metaverse Fashion Week in 2022, where brands such as Dolce and Gabbana, Etro and Elie Saab showcased digital fashion collections to a massive, diverse and multicultural audience, who left the role of spectator to participate directly in the event.

However, while one of the advantages of digital fashion is that it reduces the need for physical production, following the eminently sustainable character of immersive reality, this applied technology increases social responsibility [

34].

Brands can create innovative experiences that strengthen their image in a new virtual environment that is constantly evolving. This happens because a more direct interaction between brand/user favours the improvement of products and services on a more continuous basis. It is inevitable that the purchasing process will become more than just a simple selection of products [

35].

This is how the MV and artificial intelligence (AI) [

36] are redefining the future of fashion. From the creation of exclusive digital garments to the possibility of experiencing virtual fashion shows, fashion in the MV is already, in itself, a creative and dynamic platform that forces every sector that visits it to be constantly evolving.

Although this article focuses on the application of the MV [

37,

38] in one of the textile companies in Alcoy and Manissa, to improve the exhibition of their products, their sales and the relationship with their customers, it should first be noted that textile companies dedicated to upholstery invest a lot of resources to design their stands for promotional fairs. Stands that are only used during the 3 or 4 days of the event and are hardly reusable in other fairs [

39,

40]. This forces the designs to be economically viable and, in many cases, unattractive. However, the sector is at the point where both the company’s customers and suppliers have to travel thousands of kilometres to get to know the manufacturer’s new products, which is costly and time-consuming. The interest of manufacturers and customers in trade fairs is diminishing and there is more investment in the recycling of materials than in application or training in new technologies.

Through VR and its application to MV, it is possible to create virtual stands, digital twins of the physical ones, and to solve the aforementioned problems [

41,

42]. The absence of physical barriers allows us to create a stand design without the restrictions of material design.

By creating a virtual stand, customers, suppliers and potential users are offered the possibility of getting to know the new products and other products without having to travel to the event. Another advantage is the possibility of being able to define a space in the stand for experiences in the immersive space. In addition, a new sales channel is created for the brand, regardless of time and space limitations, since the virtual platform can continue to offer customers its products and promotions.

In this article we describe the study conducted on the design of virtual booths in the textile sector and how the application of basic design theories helps a comfortable UX. The current trend is that these technologies serve to strengthen the concept of Industry 5.0 [

43] which focuses on the collaboration between humans and machines, to improve production, personalisation and the well-being of workers, since they allow to focus more on creative and strategic tasks, rather than repetitive and dangerous ones.

This study is part of the thesis ‘Study and improvement of VR applications through design techniques. Evolution towards industry 5.0’ which proposes to create a guide of good practices so that any user, regardless of their technological and digital knowledge or without basic notions of composition and design, can achieve an acceptable result when building their immersive spaces.

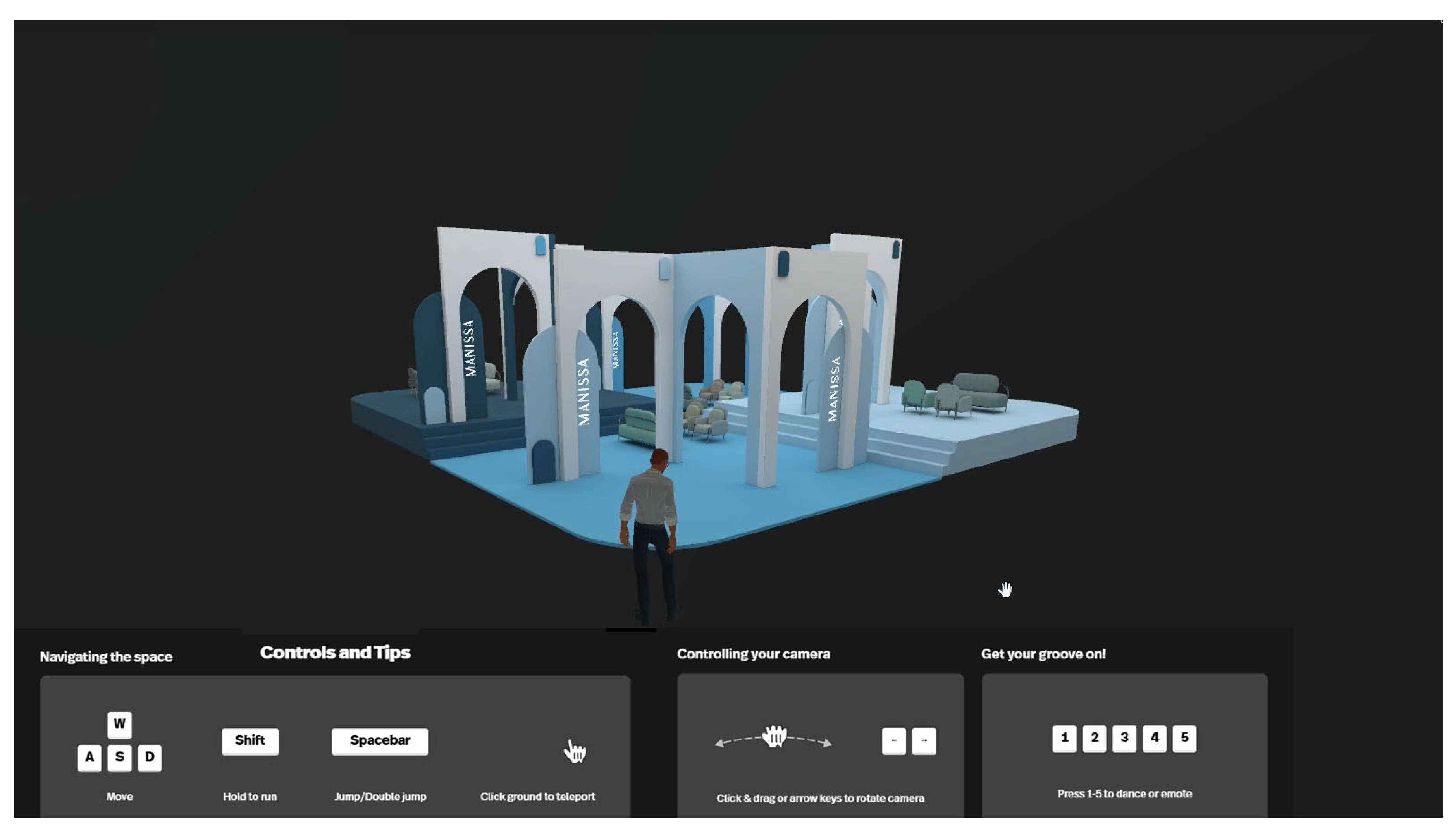

The study was carried out with the collaboration of the textile brand Manissa, using our experience and under their supervision, the latest 3D design tools were used: 3dsmax to model the stands, Unity to apply materials, animations and define the texture change carousels and the Spatial.io platform to publish the 3D content and convert it into an MV scenario.

In order to compare the results, two types of spaces have been created. The first is a digital twin of the brand. It is a model that requires few concepts and design notions, more neutral in terms of a specific style, and is more economical. The second one is designed based on a study that requires more complex composition concepts and is more aligned with contemporary minimalist trends. The tests were conducted on approximately 200 visitors at the textile manufacturer’s stand at the Hábitat fair, held in Valencia (Spain) from September 30 to October 3, 2024. After this introduction, the article is structured into four sections: In section 2, the generation of the MV scenario with the two stand designs is described; in section 3, we describe the usability of the scenario and the applied interactions. Finally, in sections 4 and 5, the discussion and final comments provided are detailed, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology for Designing Virtual Textile Stands

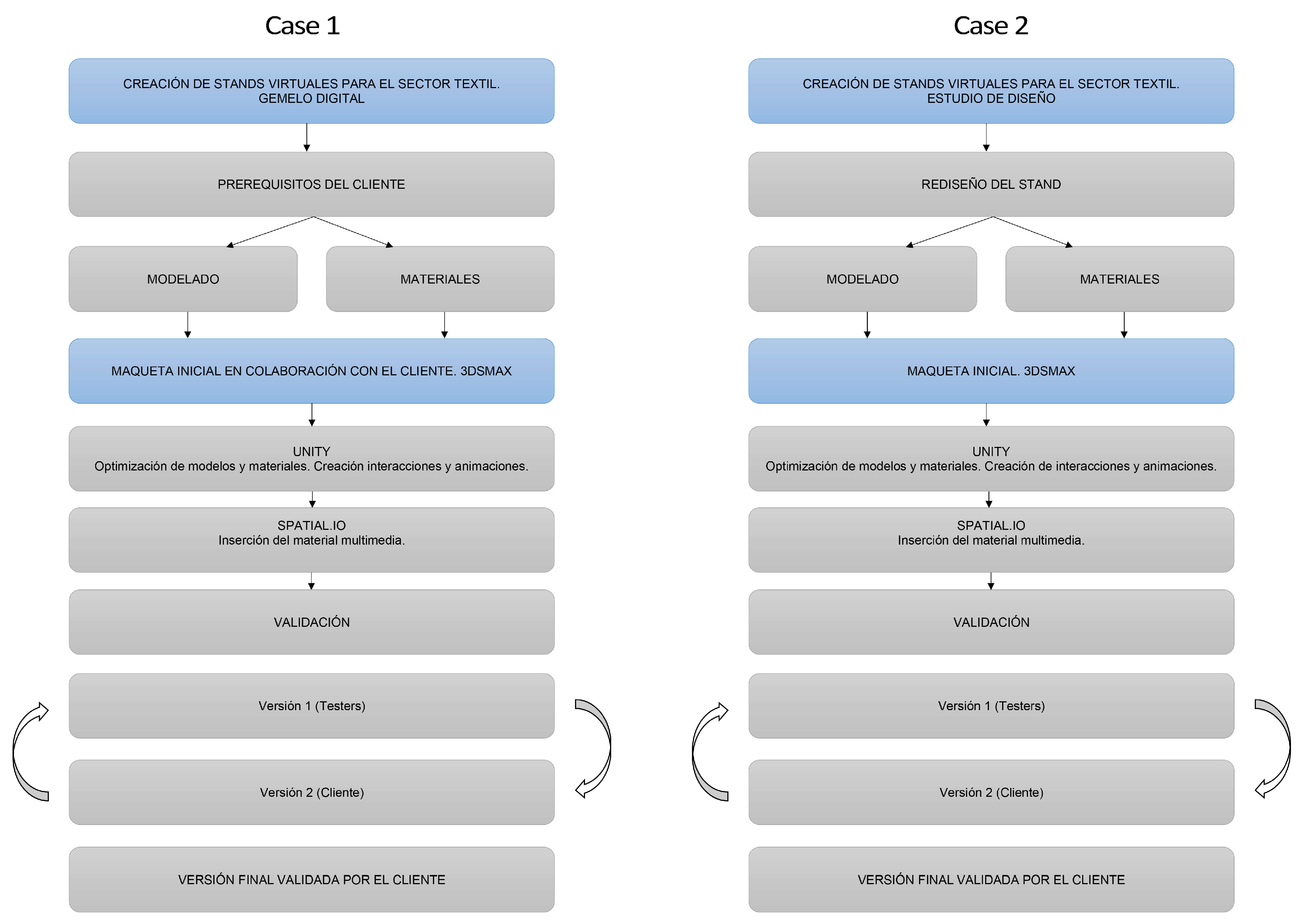

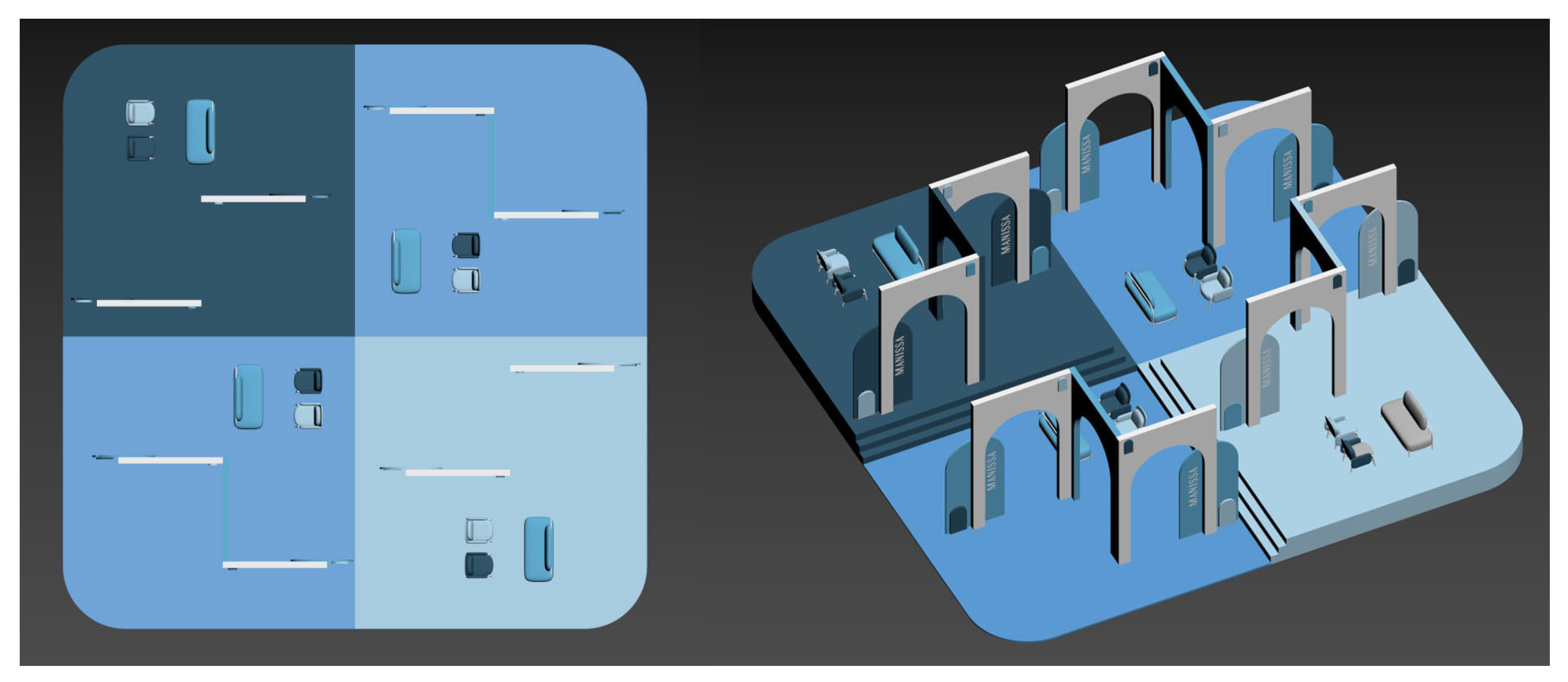

The methodologies used to create the virtual stands are illustrated in

Figure 2. They follow a comprehensive approach to developing virtual scenarios for fairs in the Textile sector. They are a foundation for any type of sector, whether for creating digital twins of the physical stand or for its redesign. The purpose of this article is to provide a structured guide that directs each phase of the design process, from the initial idea to the final product delivery. Thus, aspects such as the identification of customer needs, the selection of technical tools, and constant iteration are addressed to ensure that the final result meets the expectations of both users and the client within the MV framework. In this work, the importance of human-computer interaction (HCI) is taken into account without losing sight of the fact that interface design should be easy to use, very intuitive, and improve the UX. This study goes beyond this factor. Both methodologies share the same stages, except for the initial phase. In the case of the digital twin, a scenario is presented where it is the client who decides how they want their virtual stand. In the case of redesign, it is the designer who decides how the stand will be. This second scenario occurs rarely, since, according to acquired experience, decisions are usually subject to final validation by the client before publishing the final result on the digital platform. The process is a step-by-step system.

2.2. Modeling, Texturing, and Animation of the Digital Twin

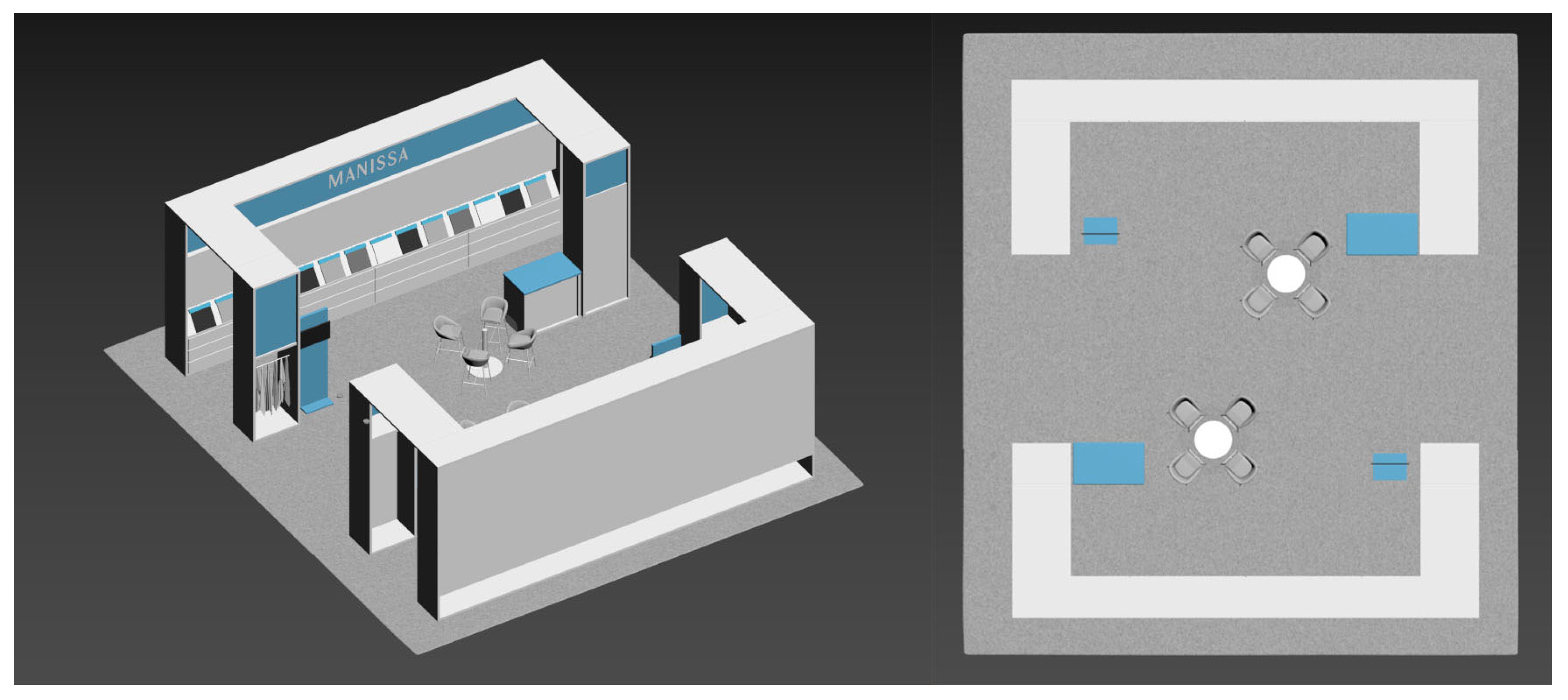

The process of modeling the digital twin begins with a meeting with the client, where they provide us with the plans for the physical stand, including its furniture, displays, and the requirements for its replica in the MV. He provides us with the hangers (samples) of the new fabrics, which we will need to scan in order to create the textures that define the digital samples. This phase is necessary as it allows us to align the client’s expectations with the limitations of the technology available for the project. The next step is to model the physical stand with 3ds Max and apply the materials according to their specifications. This process is quick, as there is no design study yet; it only needs to be replicated in the virtual world, as projected for the fair stand. In

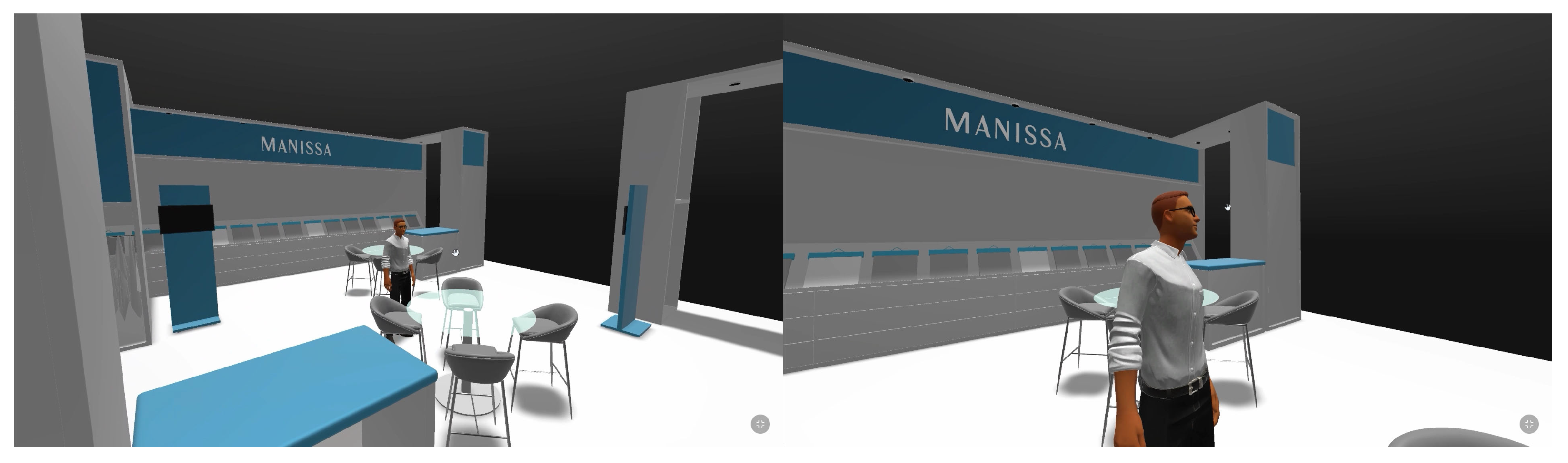

Figure 3, the result of the 3D modeling of the proposed physical stand can be appreciated.

It is a simple design that meets the client’s economic possibilities. After several meetings, the modeling of the stand, furniture, and displays is defined, in accordance with the guidelines and subsequent corrections and adjustments. This 3D modeling is exported to Unity, to optimize the objects and textures and incorporate them into the Spatial.io template [

44]. It could have been modeled and textured with Unity [

45] but the process is simpler with 3dsmax. In contrast, the Autodesk program does not have the necessary functions to implement the modeling into the MV, which Unity does have. As can be seen, the stand has a conventional structure with product displays and meeting tables. It is a robust structure, with a visually heavy appearance. The side walls are closed and obstruct the view of the stand from all angles, only allowing passage through the space in a longitudinal direction. We proceed to define the creative process of stand 2, under the premises of our basic design concept or "good design."

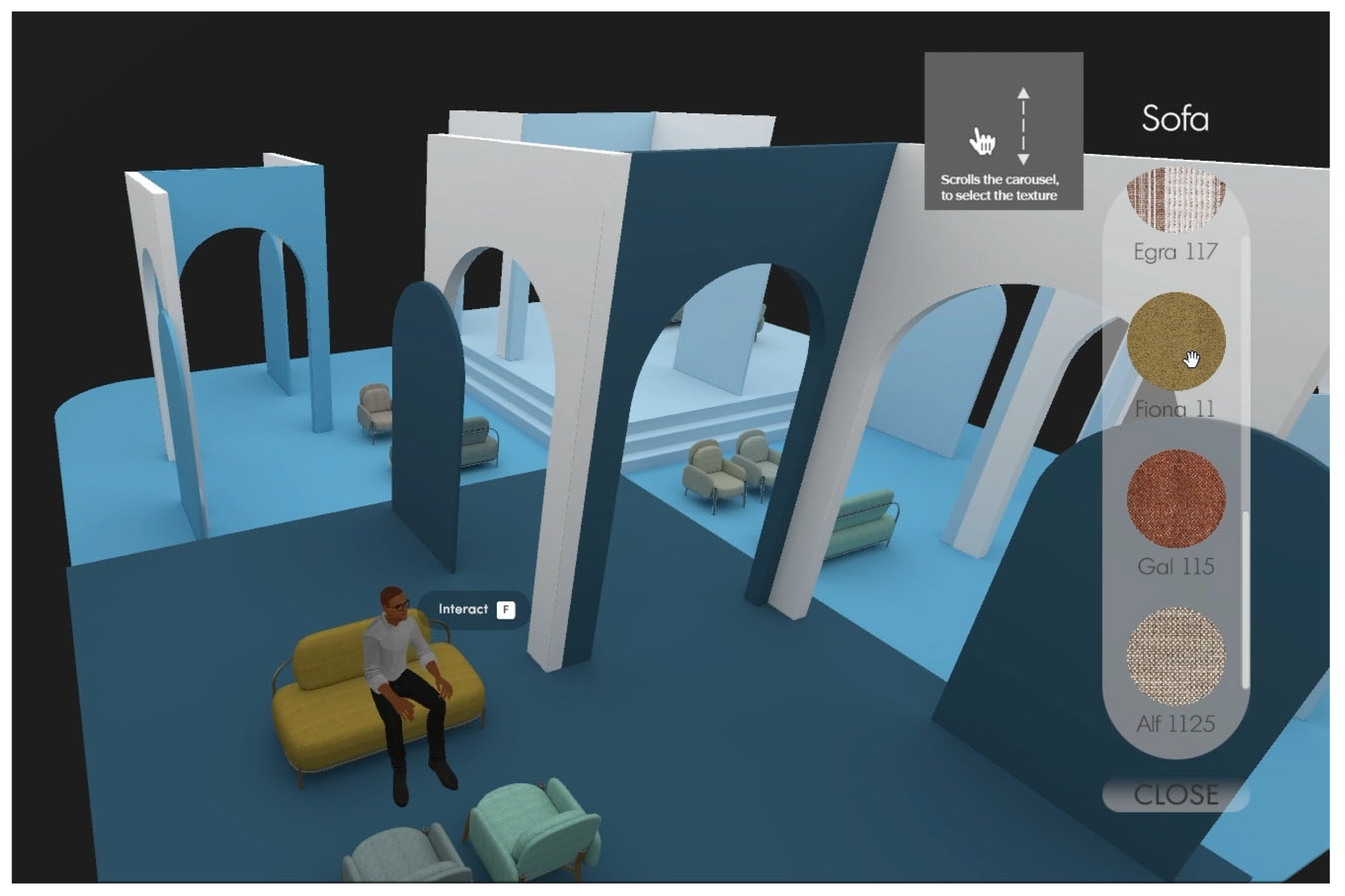

2.3. Redesign of the Virtual Booth. Modeling, Texturing, and Animation

In this case, we present a redesign of the actual stand, without any constraints from the client. For this, we apply the basic design concepts. We provide a brief summary of them:

1.- Proportion (a good proportion ensures that the components of a product are visually and formally balanced).

2.- Symmetry (when the parts of an object are reflected in a balanced manner across one or more axes, reinforcing the concepts of balance and order).

3.- Order (a good sense of order provides hierarchy and increases the indicative value of the product, which benefits the aesthetic aspects). The aim is to guide the intuitive use of the stand through shapes and spatial composition.

4.- Hierarchy (the arrangement of elements that allows the user to immediately know which parts of the product are most relevant or prioritized, favoring intuitive usability).

5.- Functionality (the ability of a product to effectively fulfill its intended purpose), Clarity (facilidad con la que un usuario puede entender y usar un producto).

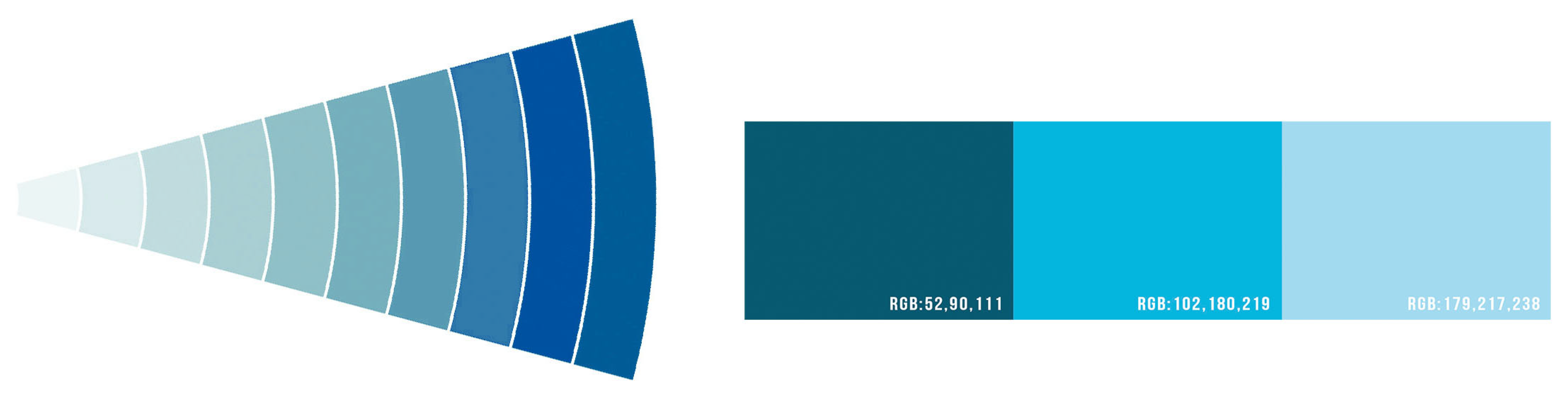

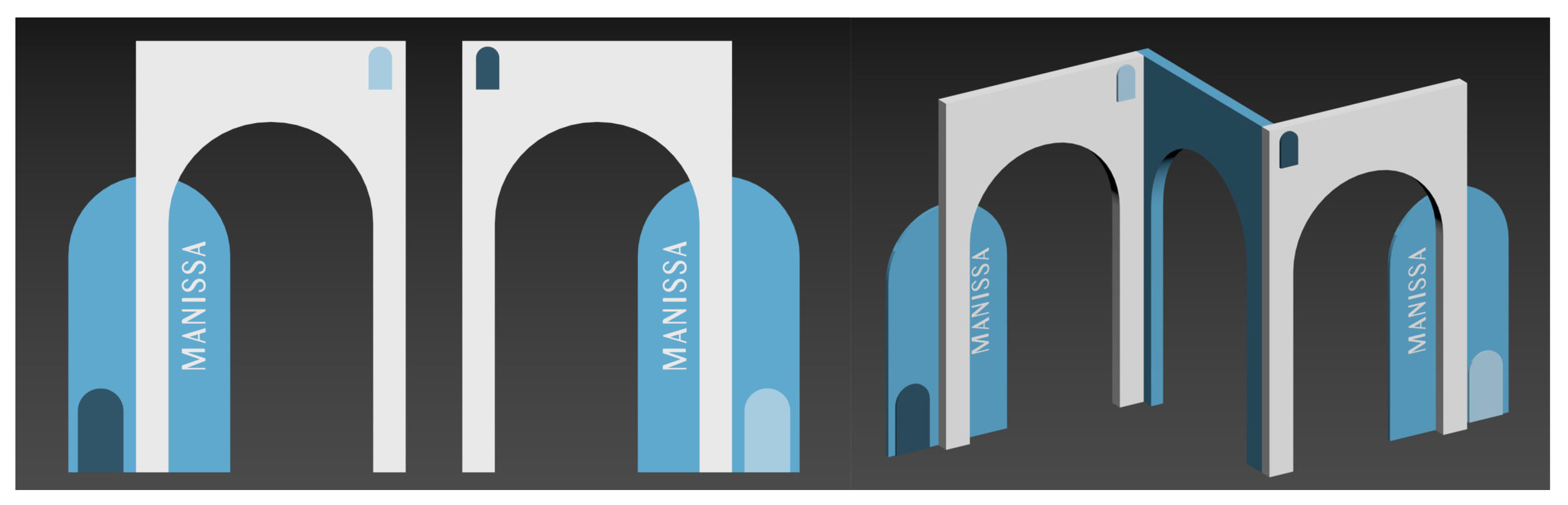

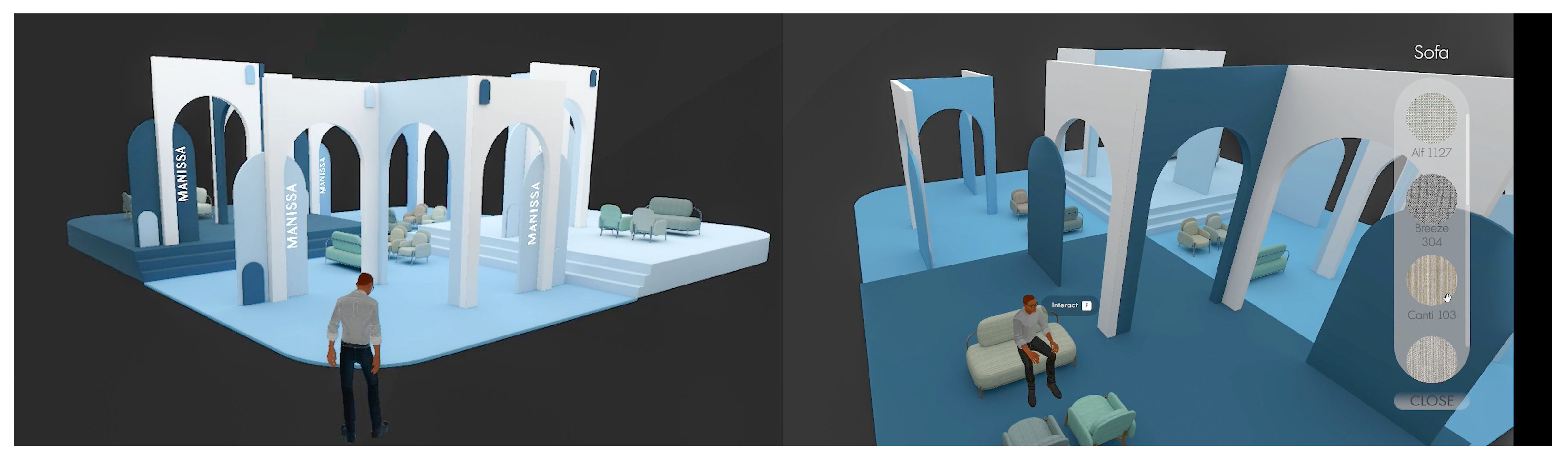

6.- Simplicity (reducing complexity that diverts balanced and aesthetic perception). First, it was decided that the color palette of the stand would be monochromatic (See

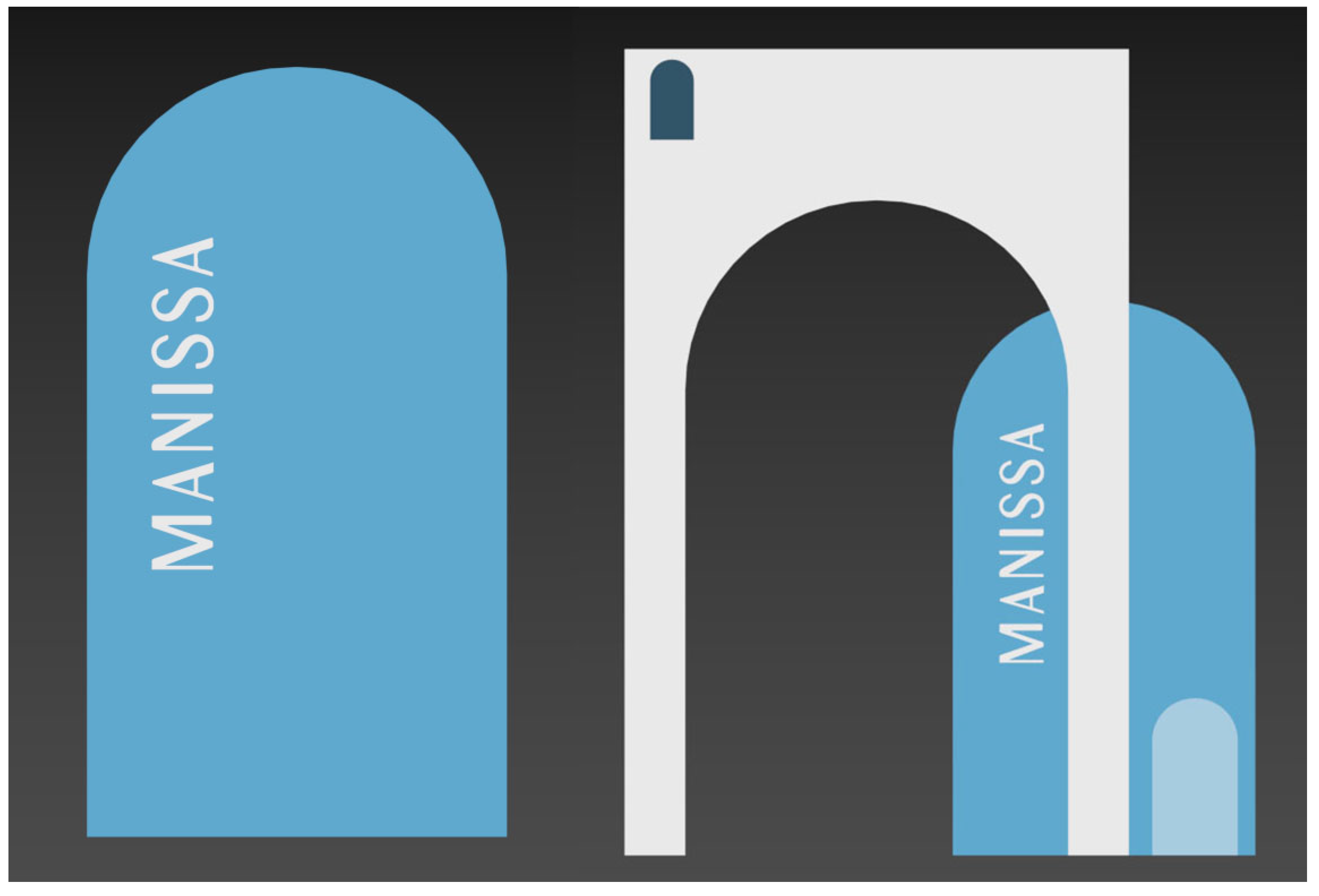

Figure 4), fading from the brand color, with increments of brightness, to white. The color games are arranged in simultaneous contrast, adhering to the principle of Proportion. To give the stand greater lightness, a system of enclosures and arches has been designed that bear the Manissa brand logo, ensuring that the perception is always formally and chromatically balanced, adhering to the principle of Simplicity. (See

Figure 5 and

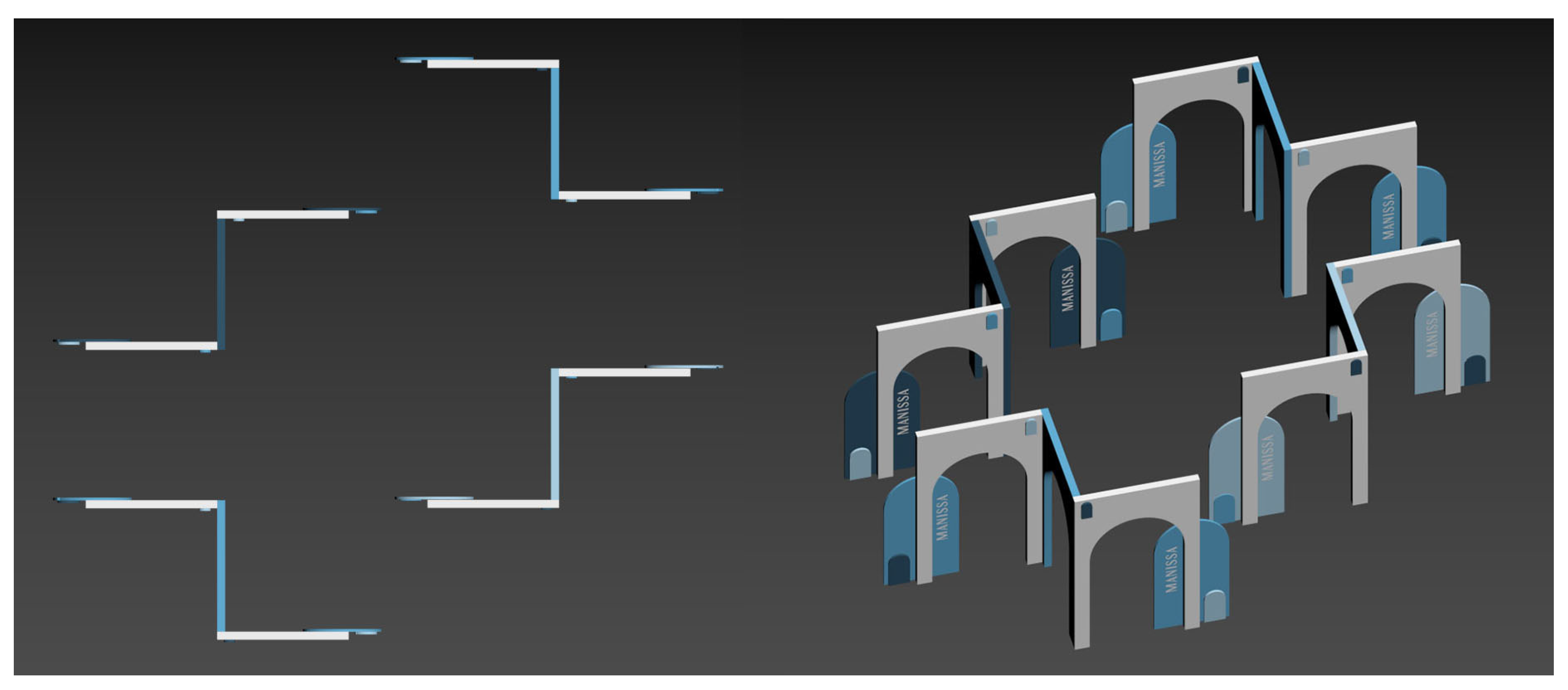

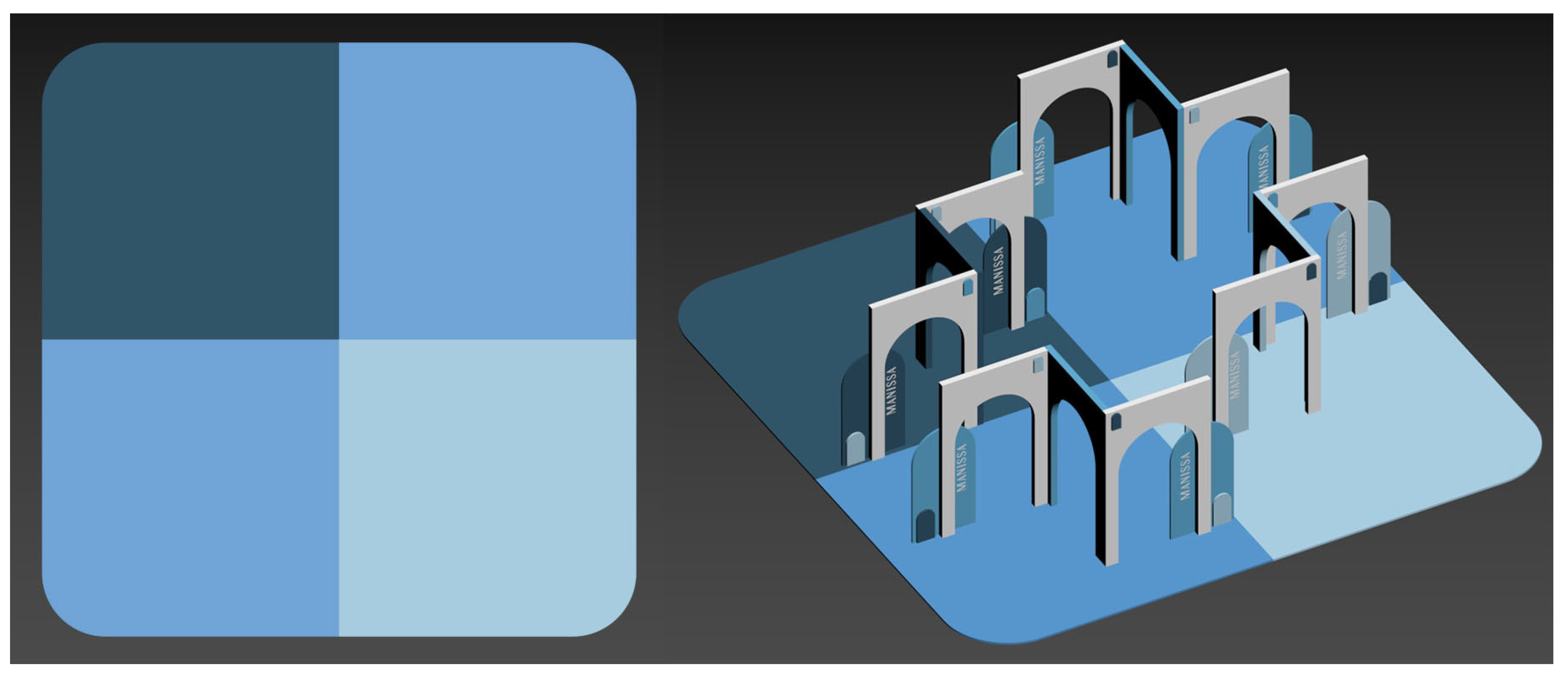

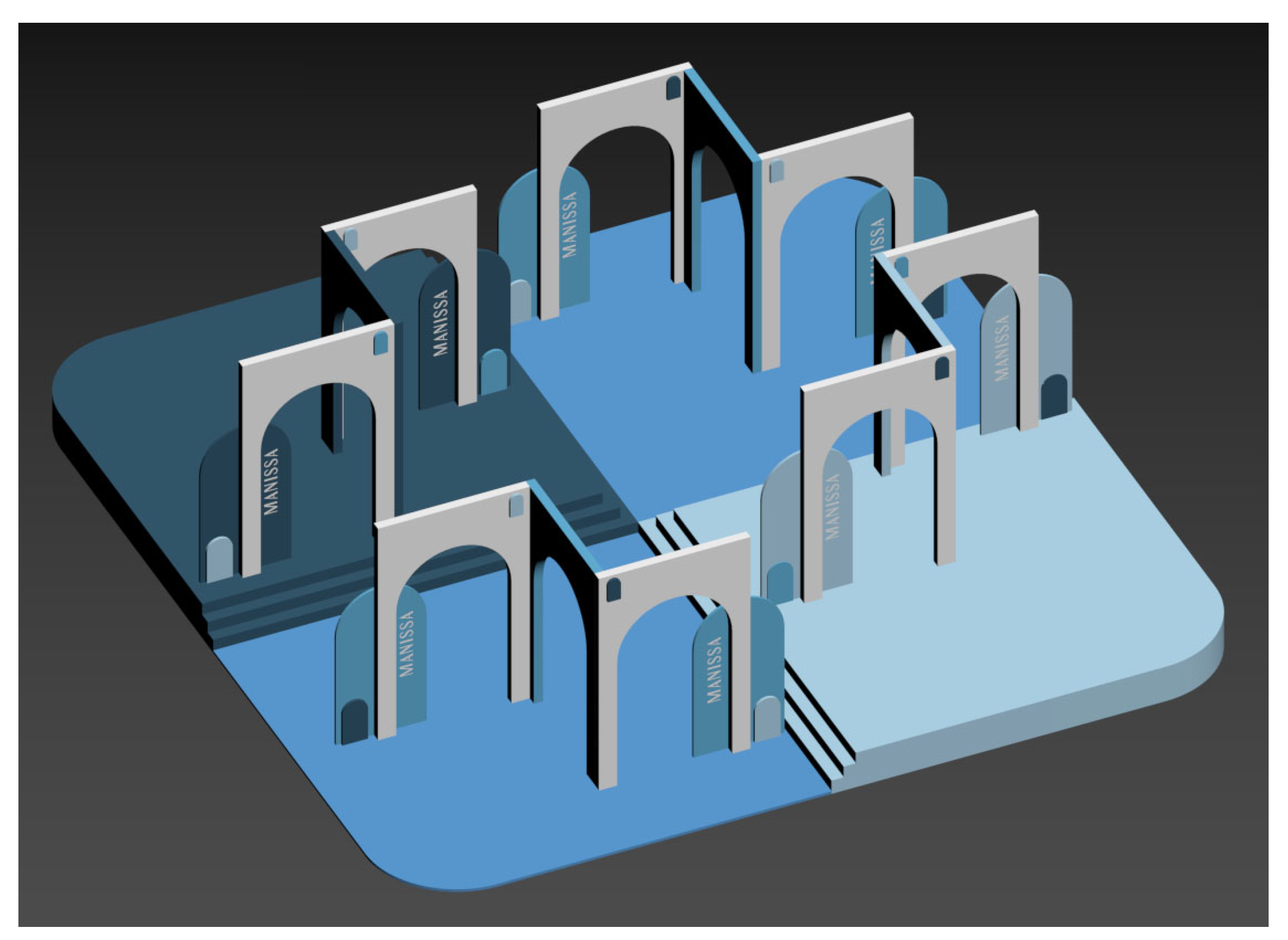

Figure 6). For the assembly of the different elements, it has been decided to place an L-shaped structure, which allows the user to move comfortably between the various areas, applying the principles of Order and Functionality. The result is a harmonious composition combining three shades of the same monochromatic range. The overall space has been designed using Symmetry, so that the user has a sense of harmony, applying the principle of Clarity. See

Figure 7). For the base or ground, a symmetrical chromatic arrangement has been decided in accordance with the rest of the three-dimensional set (See

Figure 8). Analyzing the design of the stand, it was found to be too flat, and it was decided to insert stairs in two of the panels to better differentiate the four areas (See

Figure 9). And finally, warm and comfortable furniture was designed. We decided to place a set of two armchairs and a sofa (See

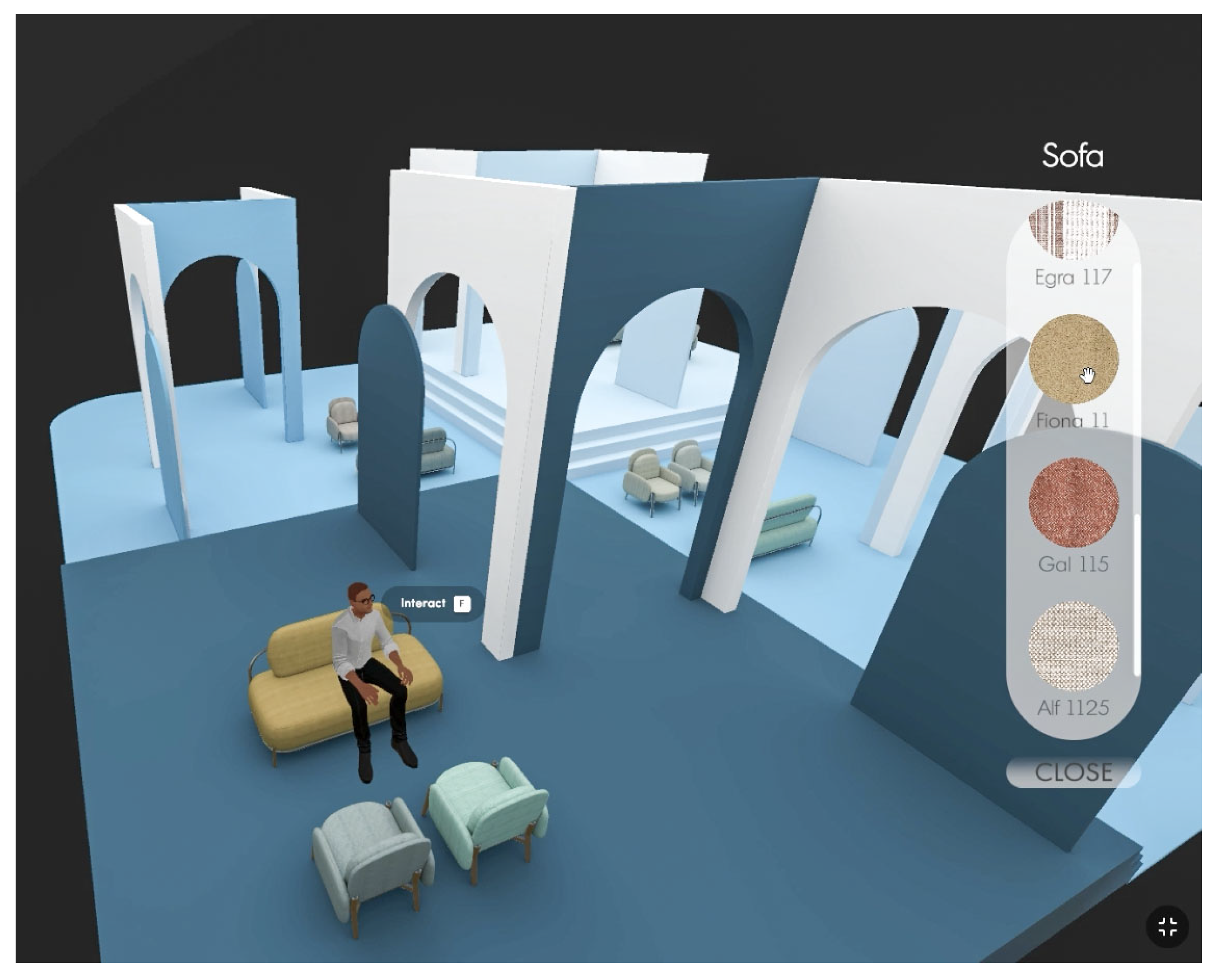

Figure 10). Regarding the fabric hangers or samples, it has been decided to digitize them. In the MV, carousels will be used to exchange the designs of upholstery fabrics applicable to sofas and armchairs. Our MV avatar can sit comfortably and choose textures from the carousel and apply them to the selected sofa or armchair model (See

Figure 11). In the case of constructing the real or physical stand, it would be preferable to use tablets or AR applications instead, to be able to show the customer "on-site" the possibility of combining and modifying textures in the same way.

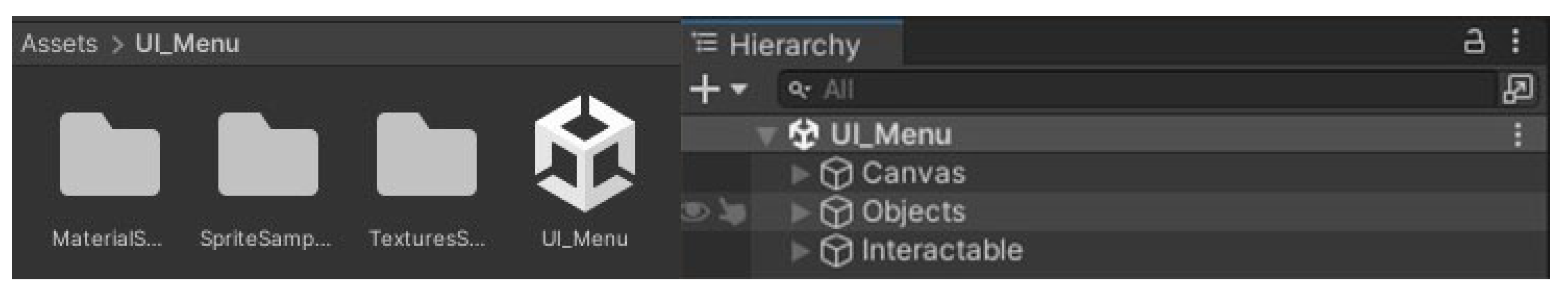

2.4. Optimization of Models and Materials with Unity. Creation of Interactions and Animations

Unity is one of the most popular and versatile game engines on the market, alongside Unreal. It has gained an important role in the development of applications for MV due to its ability to create interactive 3D environments and immersive experiences. Its technology allows developers to build virtual worlds in real-time, making it a key tool for projects ranging from video games to VR, AR, and Mixed Reality (MR) experiences, which are fundamental components of MV. It allows the creation of enriched, interactive, and customizable experiences that can be enjoyed on a variety of devices and platforms.

Although Unity and Spatial.io are closely related in the context of developing immersive experiences and VE, they serve different roles within the 3D content creation and MV ecosystem. They are interconnected because Spatial.io uses Unity as part of its development backend. The 3D environments and interactions seen in Spatial.io are built using Unity technology, allowing it to create visually very appealing and realistic experiences in real time. Spatial.io provides an accessible way to use the 3D worlds created with Unity, allowing for social, collaborative, and commercial interaction in the MV, while Unity is the technological foundation that makes it possible to build those environments with a high level of detail and interactivity.

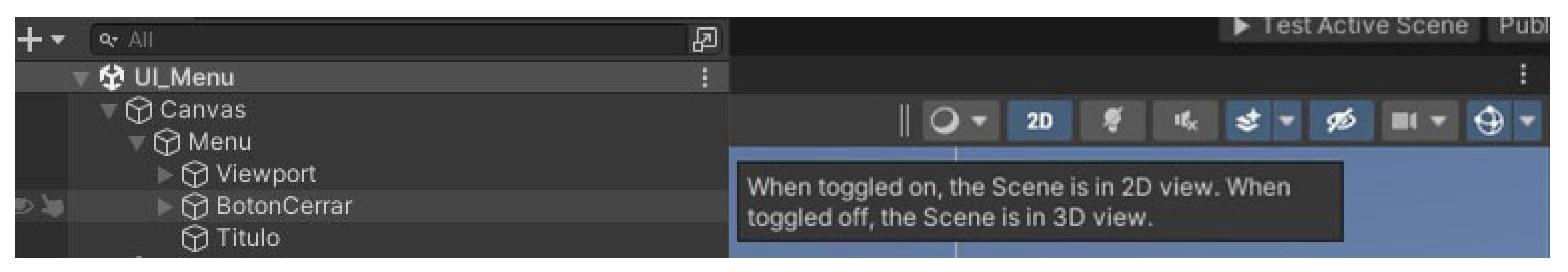

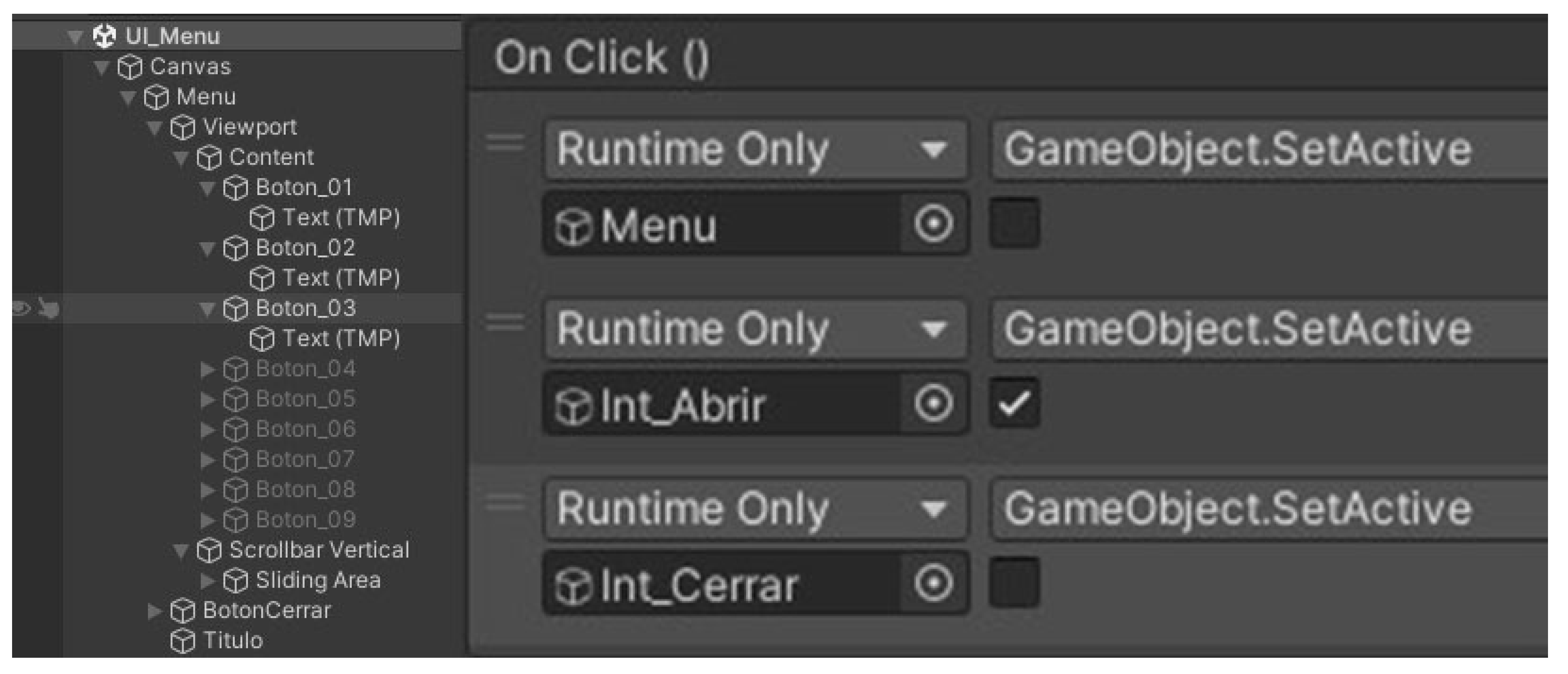

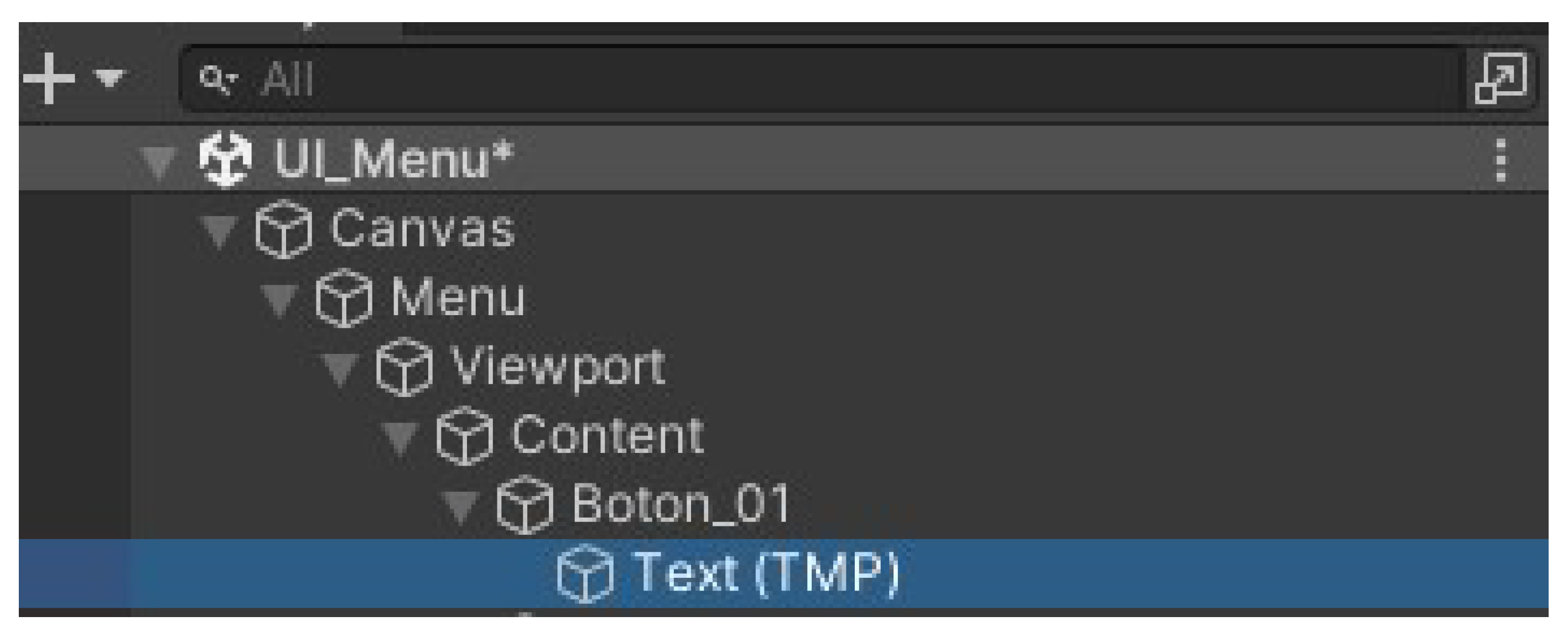

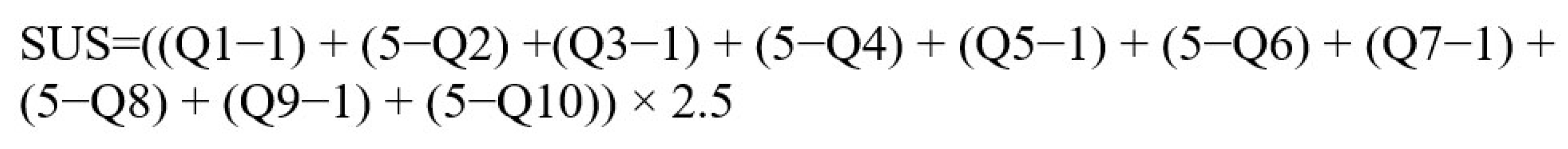

The version of Unity used for creating the digital twin and the redesign has been 2021.3.21f1. To start working, the ui_menu_spatial package must be imported into the project. By importing it, we will obtain example assets, which will serve as the foundation for our work. So, we need to open the level and copy all the elements from the hierarchy to the Project to use them as a template (See

Figure 12). Within this template, there is the group that defines the selection menu for textures. If another menu is created, it is recommended to include it within the canvas. The viewport tab contains the graphical elements of the menu; to view it correctly, you need to activate 2D mode and press the F key to center the view on the selected element (See

Figure 13).

In the Content group, the buttons are located. In this case, only three of them are activated to simplify the example (See

Figure 14). The Close Button is responsible for deactivating (GameObject.SetActive) the Menu component and the IntCerrar element. On the other hand, the same button activates the Interactable element with which we can open the menu again. The Title is the text component where a title for the menu can be defined (See

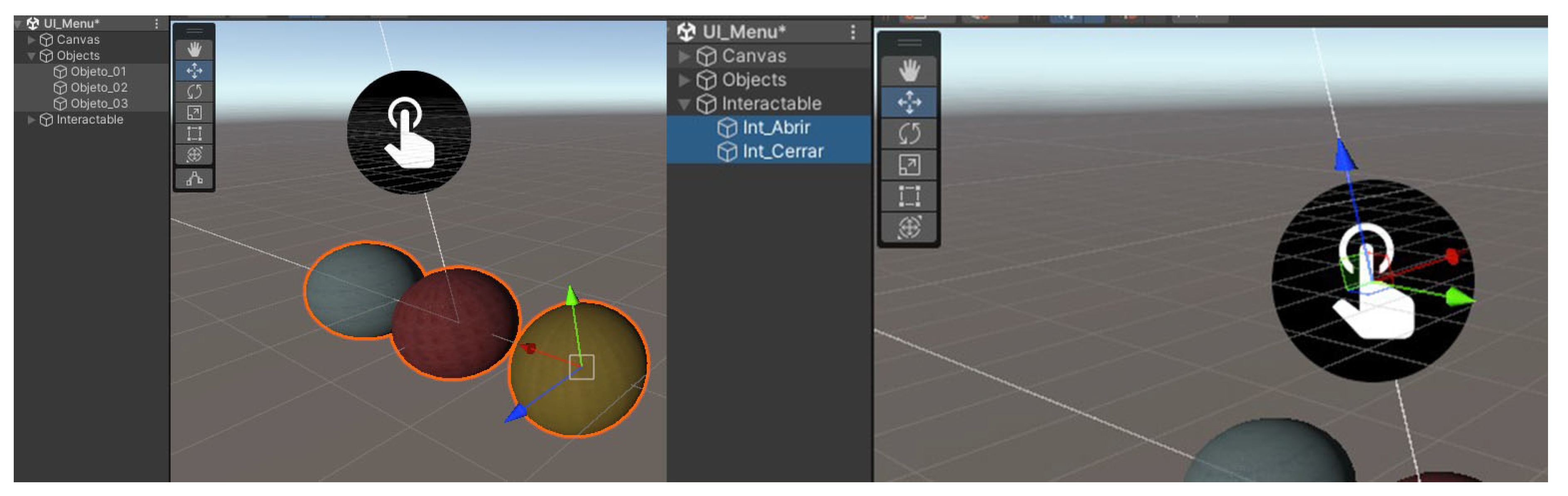

Figure 15). In the Objects group, there are the spheres that serve as samples (See

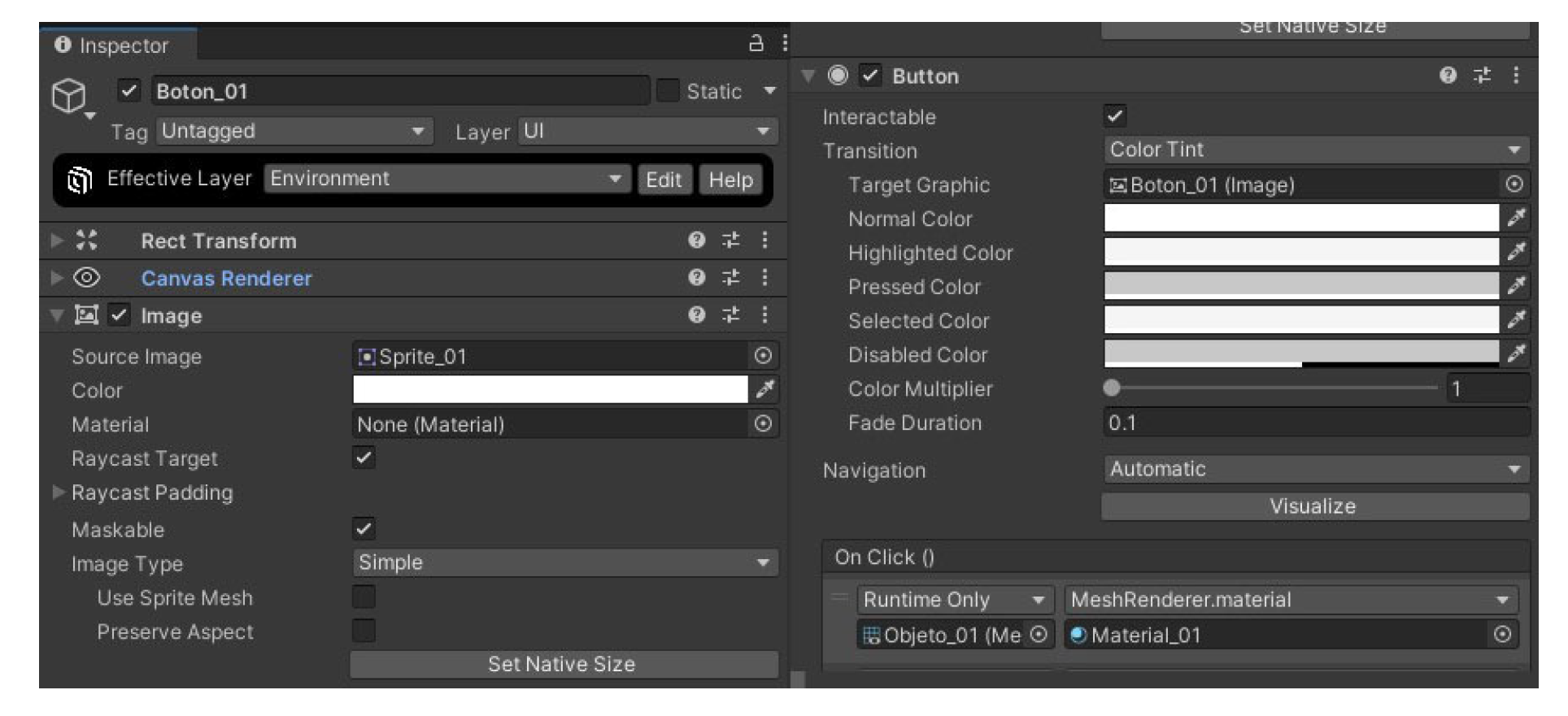

Figure 16). In the Interactable group, there are two Spatial components that will be used to define the actions of opening and closing the menu. We will need to rename the buttons in the hierarchy (they are located in Canvas>Menu>Viewport>Content) according to the name of the texture to facilitate their identification. When selecting any element from the Content group, you need to redefine:

1.- Button image (Source Image).

2.- Action on click: define the object and the MeshRenderer.material function.

In this way, the button will change the material of the selected object to the material defined in the Button component: OnClick (See

Figure 17).

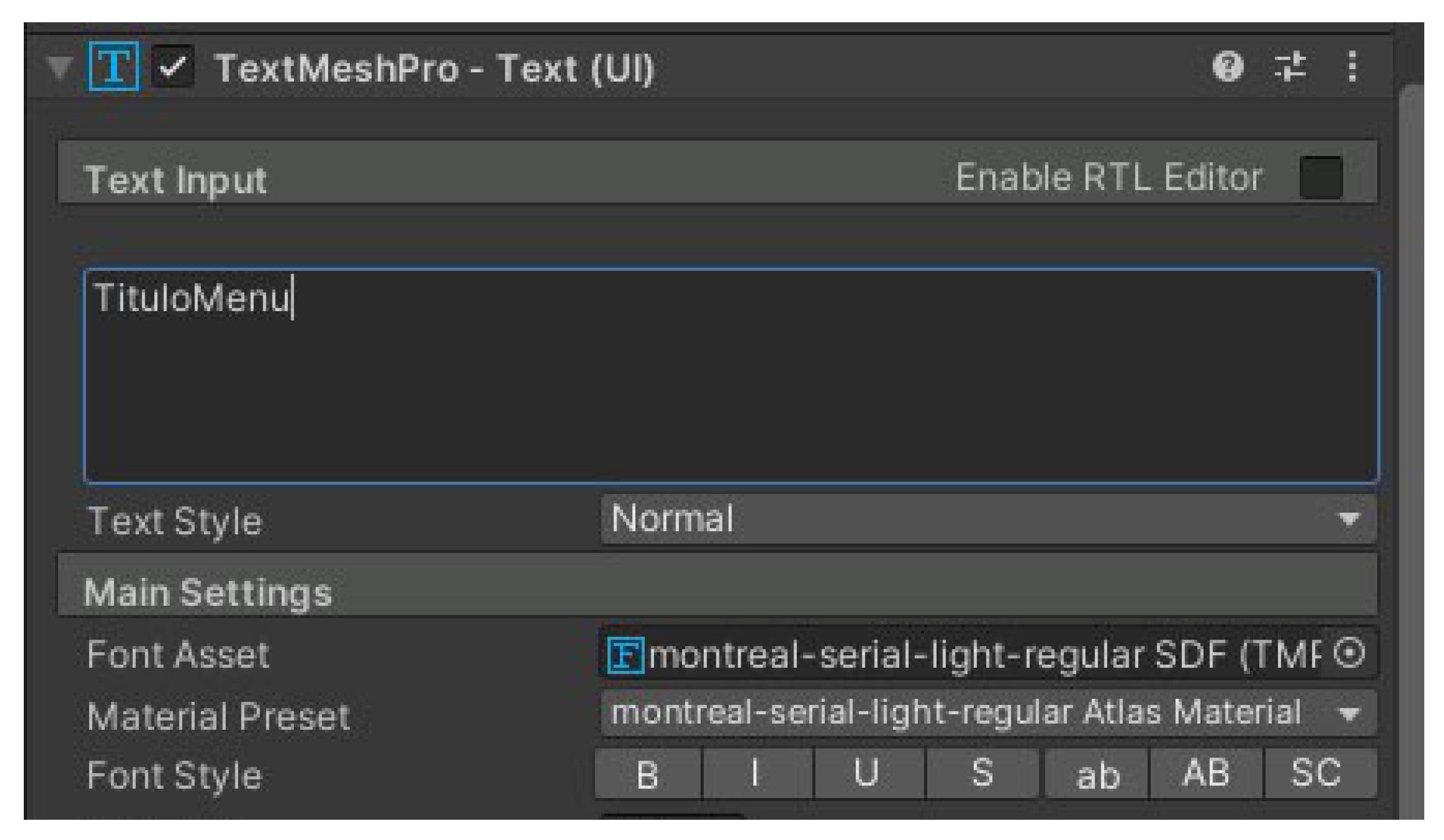

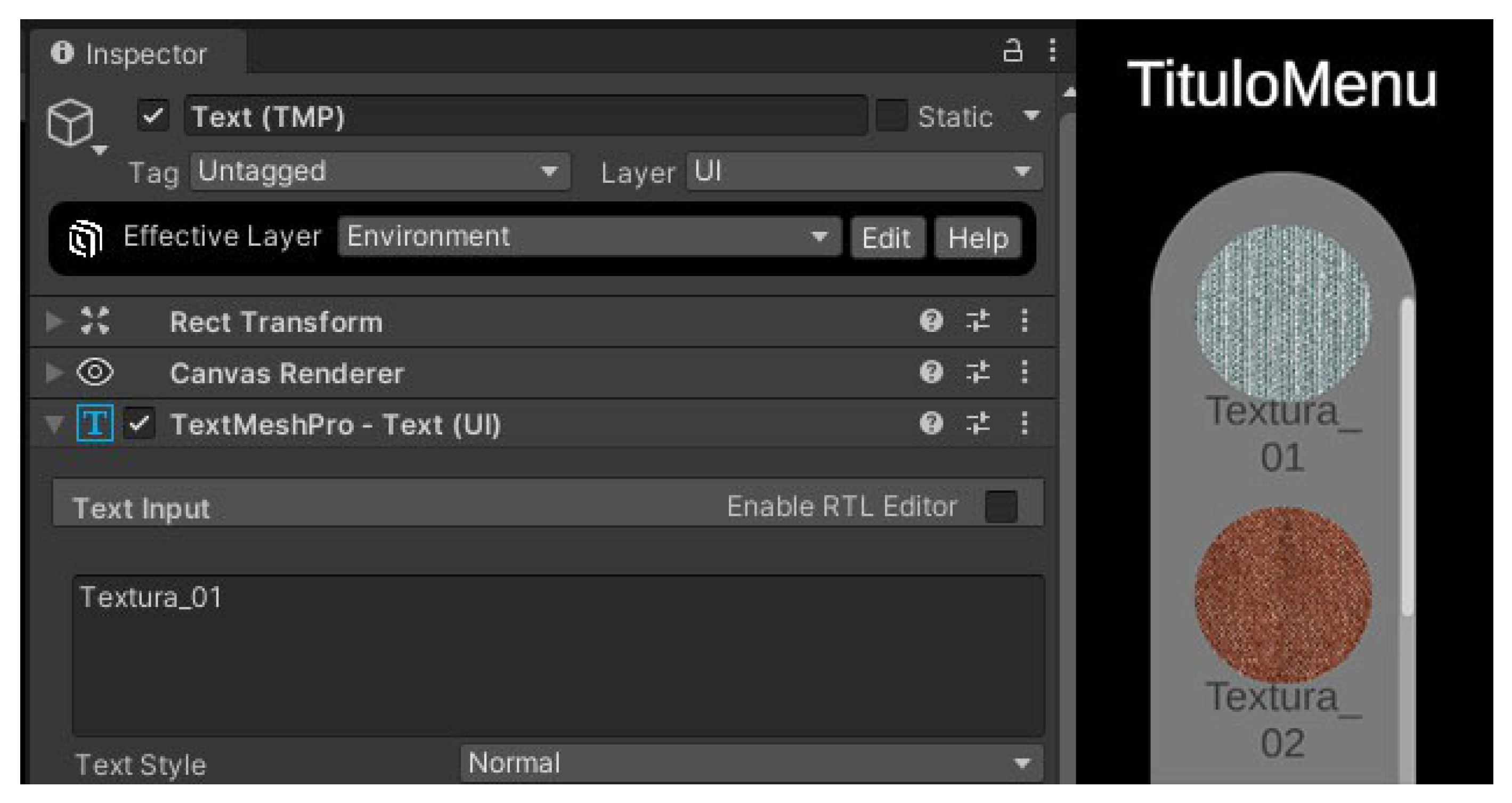

We also need to change the text displayed below the button: We select the Text (TMP) component (See

Figure 18).

In the Properties panel, we will be able to edit the text (See

Figure 19).

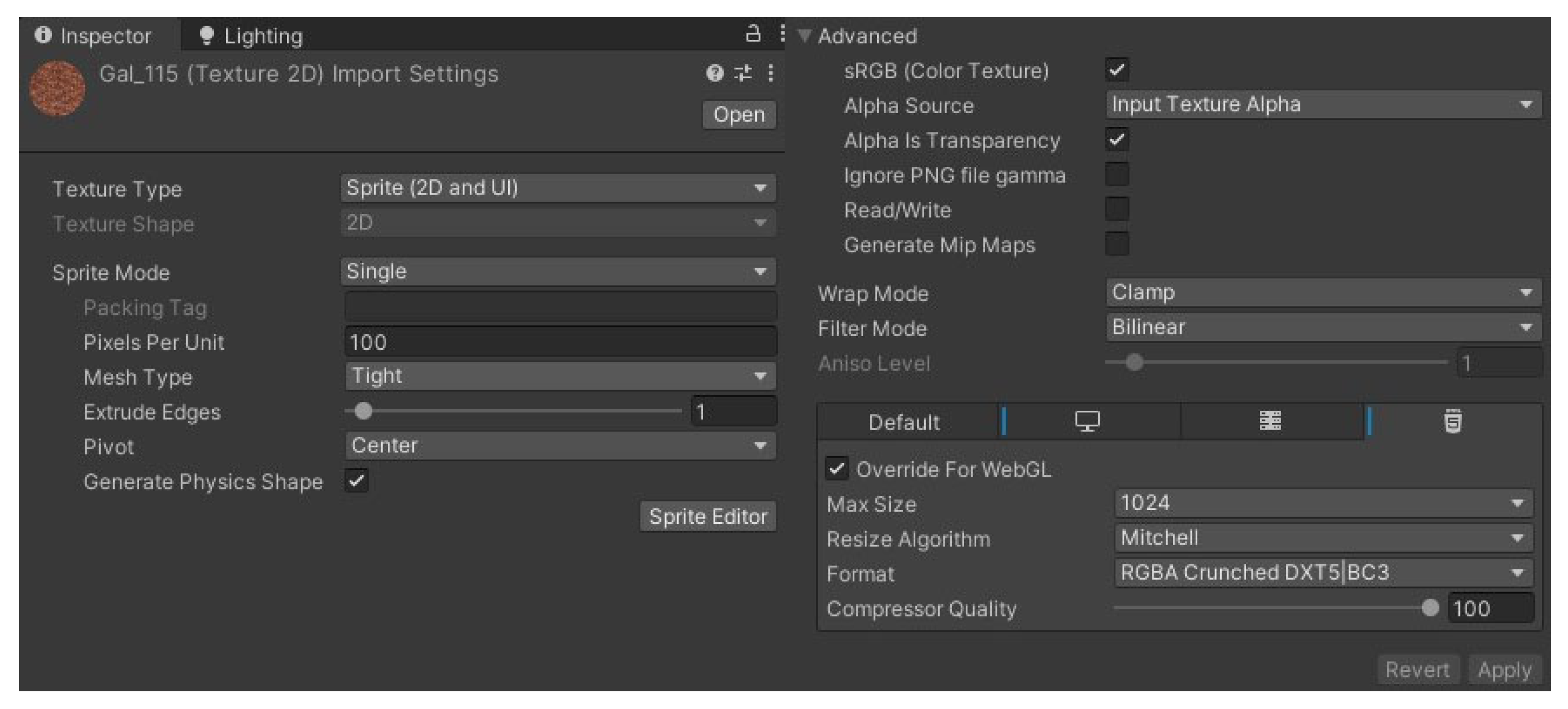

The textures for the icons must be of the Sprite type, with the following configuration (See

Figure 20).

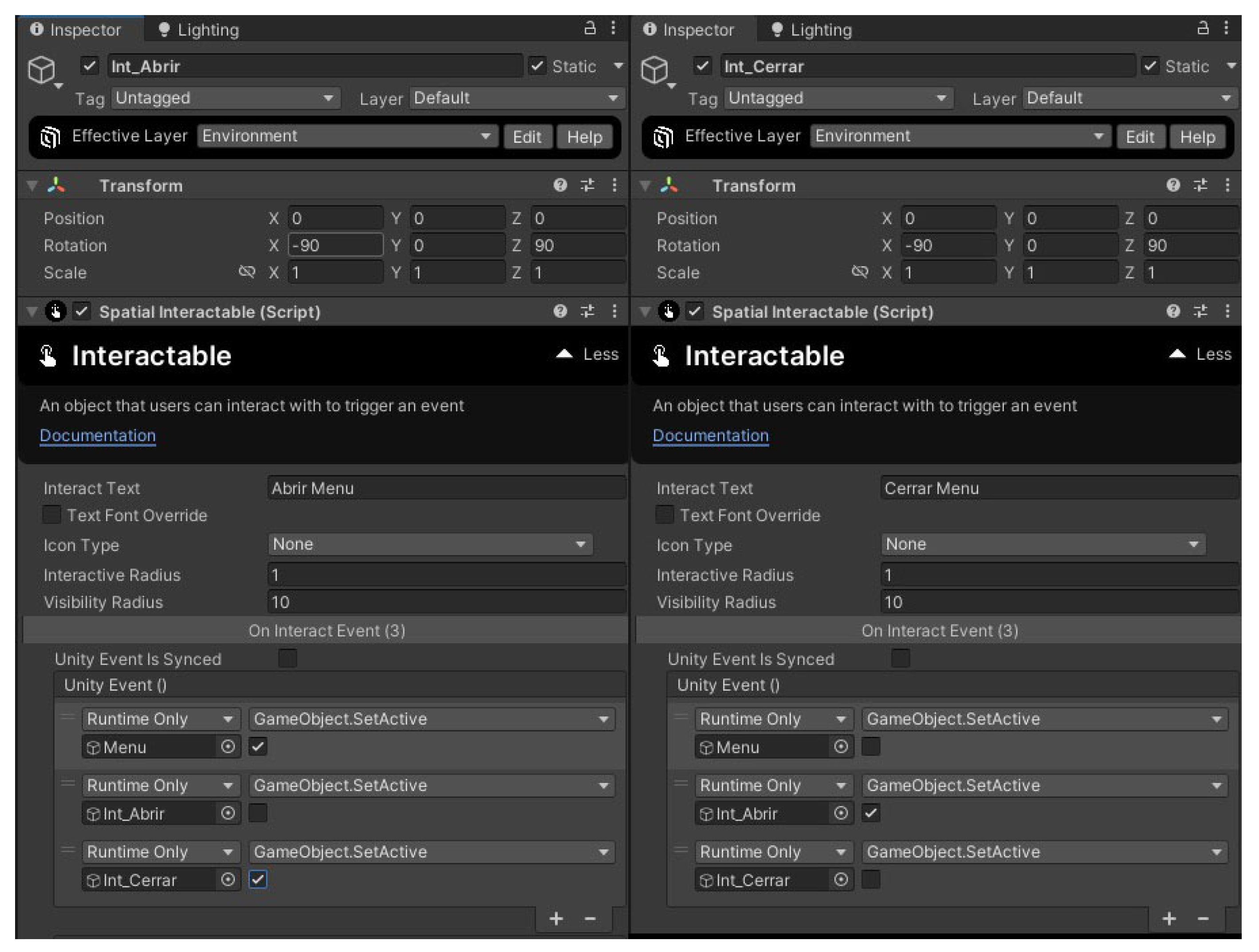

It is recommended to use power-of-two textures, with 1024x1024 being the recommended resolution. To open or close the menu, we will use two Interactable-type components, both placed in the same location. It is important to define the IntAbrir component as an activated object and the IntCerrar component as deactivated (See

Figure 21).

When executing IntAbrir, the following will happen:

1.- The menu will open.

2.- The IntAbrir object will be hidden.

3.- The IntCerrar object will be displayed.

Since the IntCerrar component is now the one that is active, when executed:

1.- The menu closes.

2.- The IntAbrir object will be displayed.

3.- The IntCerrar object will be hidden.

In this way, we are "swapping" the function of the interactivity button, but in practice, we are just playing with the visibility of both interaction components. It should be noted that the menu uses a background image (BGSprite), so if we need to scale the background, we must edit the sprite; otherwise, it will appear distorted (See

Figure 22).

2.5. SPATIAL.IO. Insertion of Multimedia Material

Once we have published our Unity space on the Spatial platform, we will be able to enter and navigate through it. All multimedia elements, such as images, videos, presentations, etc., must be configured from the online platform, using the Empty frames introduced in Unity (See

Figure 23).

2.6. Research Design

To validate the Tester versions of the digital twin and the redesign created for this research, a laptop and VR glasses, Meta Quest 3, were used. Our intention was for the user to be able to test both platforms and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of each one. The tests were conducted individually. Before each test, a technician conducted a simple tutorial to explain how to put on the glasses and use the controllers and their buttons to navigate through the space and its menus. The tools for socialization and avatar creation were described, as well as the tools for image and video capture creation. Users were warned about the possibility of feeling some dizziness and were advised not to make sudden and quick movements.

During the test, the technician virtually accompanied the user with their own avatar, to prevent them from getting lost on the route, and to ensure they knew how to correctly use the virtual texture carousel and apply it to the furniture. Once the user became proficient in their movements, they were allowed to navigate freely through the scene, without a time limit. The same process was followed for the rest of the users who tested the application from the laptop. They were introduced to the same scenario, so they could coexist with the person who was simultaneously testing the VR glasses. The tests were conducted during the International Furniture and Lighting Fair Hábitat València, from September 30 to October 3. For this, the physical stand of our client Manissa was used to showcase both platforms. In this way, the user could virtually visit the physical stand where it was located and compare it with the redesigned stand.

The interactions and reactions of the users were recorded during each of the tests, so they could be evaluated later. The test was considered finished when the user requested to leave the stage.

2.7. Data Analysis

To validate the methodology employed in the trials, interviews were conducted with the users and tests were carried out to assess the degree of satisfaction with the experience of the digital twin stand (Case 1) and the redesign. (Caso 2). Then, two standard questionnaires were given to each user: the IPQ (Igroup Presence Questionnaire) and the SUS. (Escala de usabilidad del Sistema).

Indicate that the iGroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) is a questionnaire designed to measure people’s sense of presence in VE, such as VR. Presence refers to the subjective feeling of "being" truly in a virtual environment, beyond simply interacting with a digital simulation. This questionnaire was developed to evaluate this immersive experience and is a widely used resource in virtual reality studies and interactive digital environments.

The IPQ is structured into 14 questions to evaluate different aspects of the presence experience, such as:

1.- Spatial Presence: Evaluates the perception of "being physically in another place" while in the virtual environment.

2.- Immersive Presence: It measures the level of concentration and interest in the virtual environment. Greater participation suggests that the user has emotionally "immersed" themselves in the experience.

3.- Presence Realism: Capture the perception of realism of the virtual environment. Evaluate if users feel that the environment is "believable" or similar to the real world.

4.-General Presence: A more general measure of presence that complements the other dimensions and allows for a comprehensive view of the presence experience.

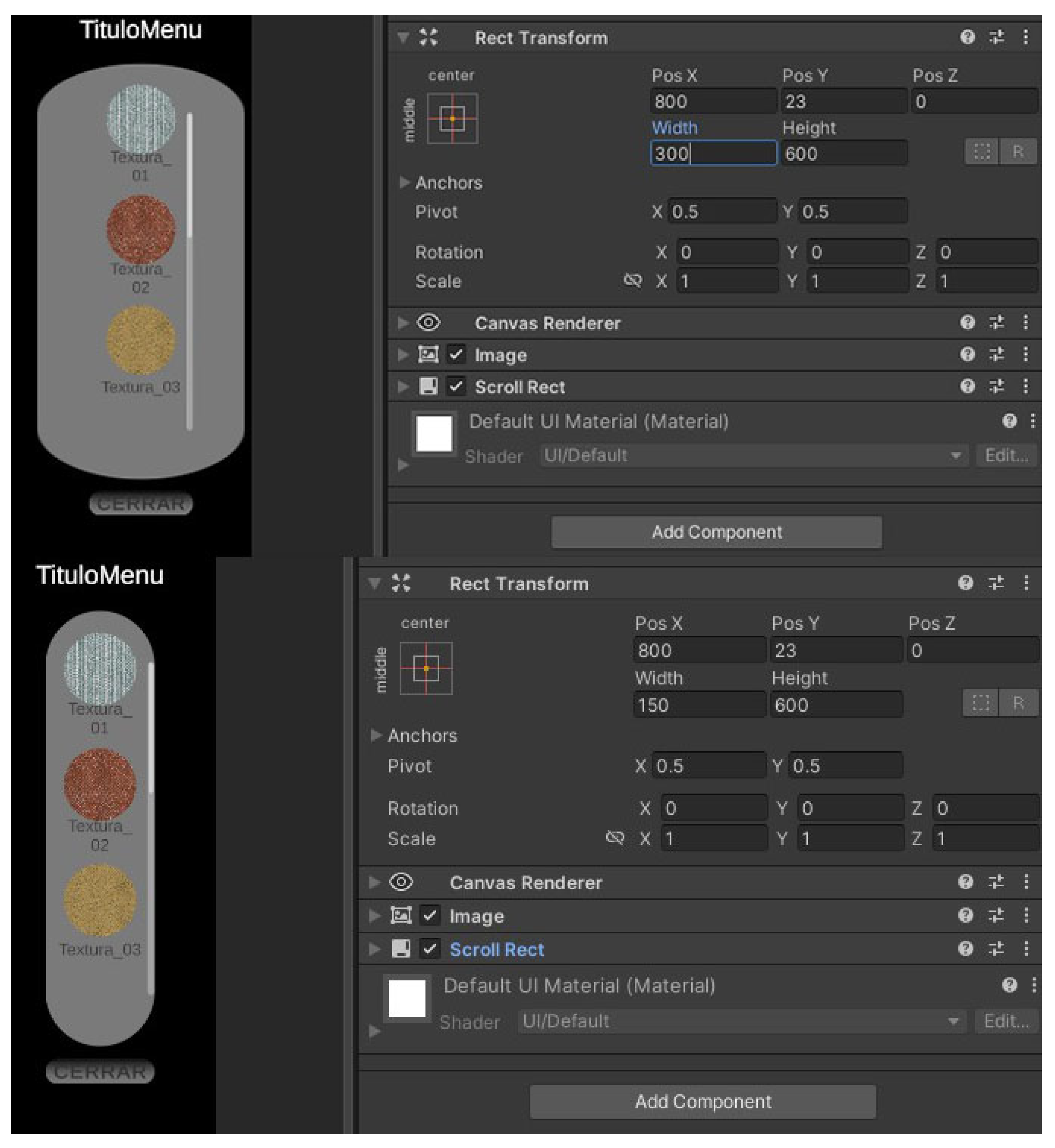

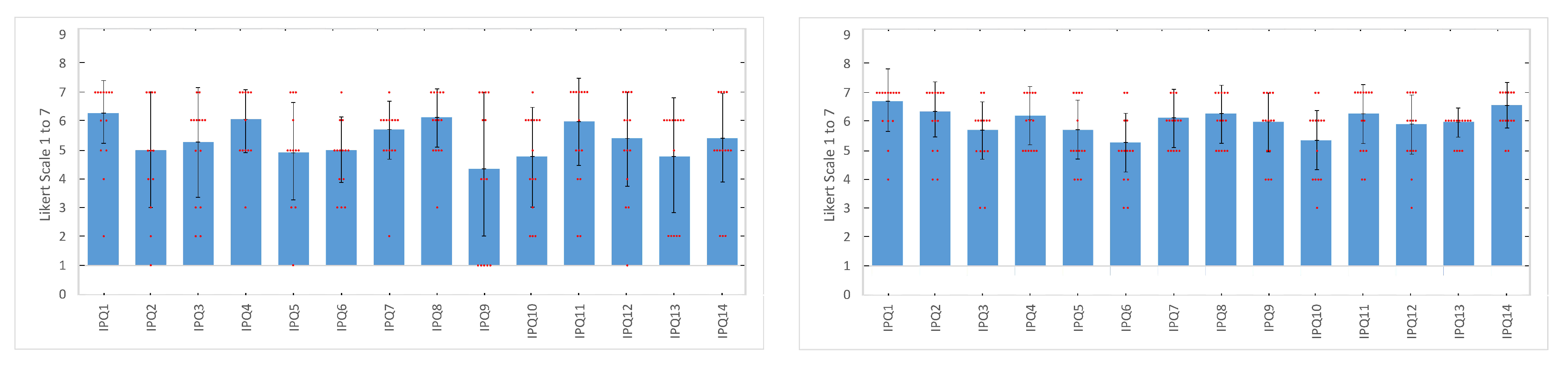

The IPQ is used to evaluate the effectiveness of VE in generating an immersive experience, compare different VR or AR technologies to see which ones generate a greater sense of presence, and improve the design of immersive experiences in video games, training simulations, exposure therapy, and educational applications. The 14 questions of the IPQ questionnaire are detailed in

Figure 24. The measurement method used for this questionnaire is a 7-point Likert scale. In this article, the variables of each test are analyzed, using a standard deviation of the average scores of the questions in each test.

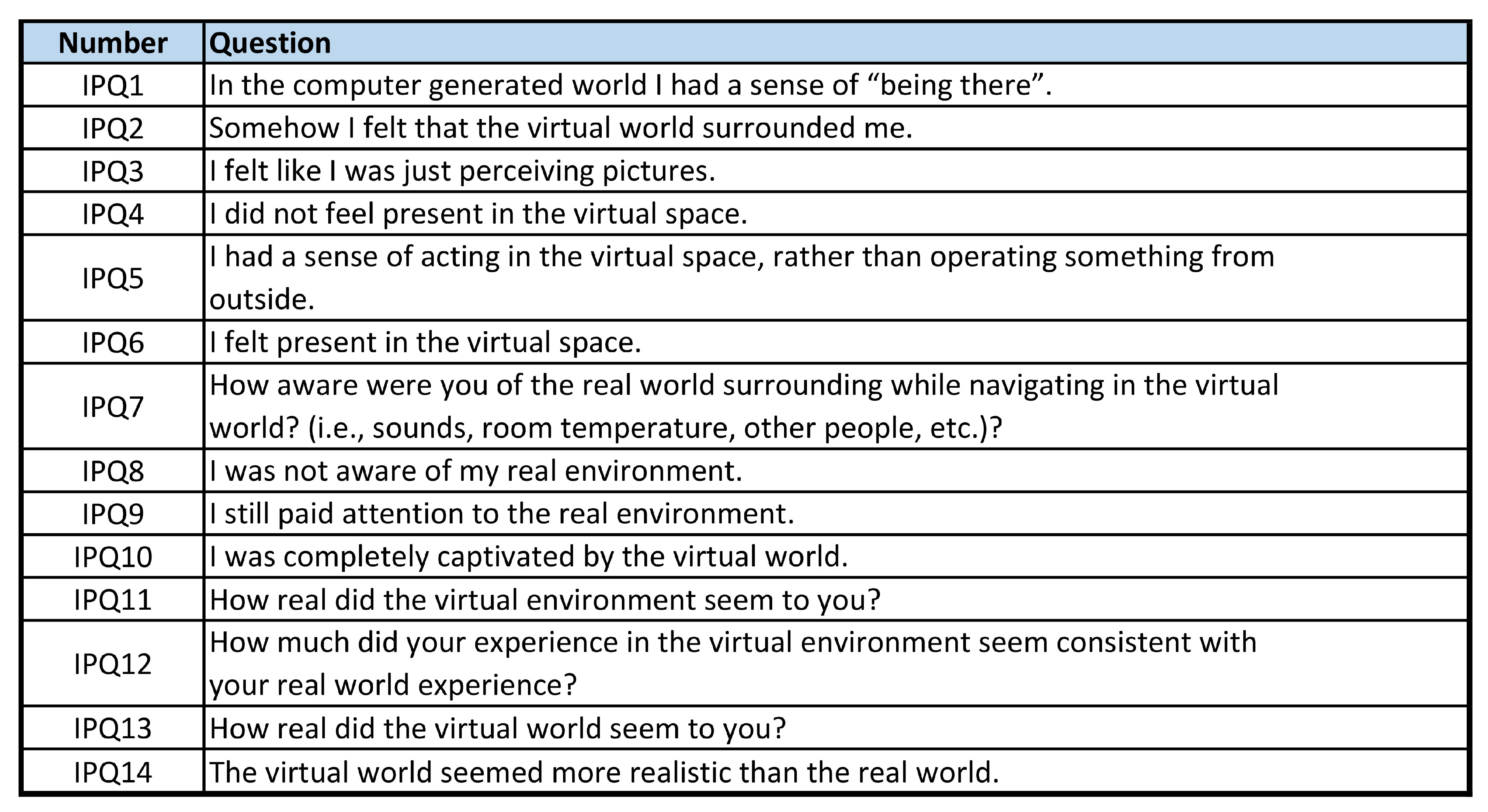

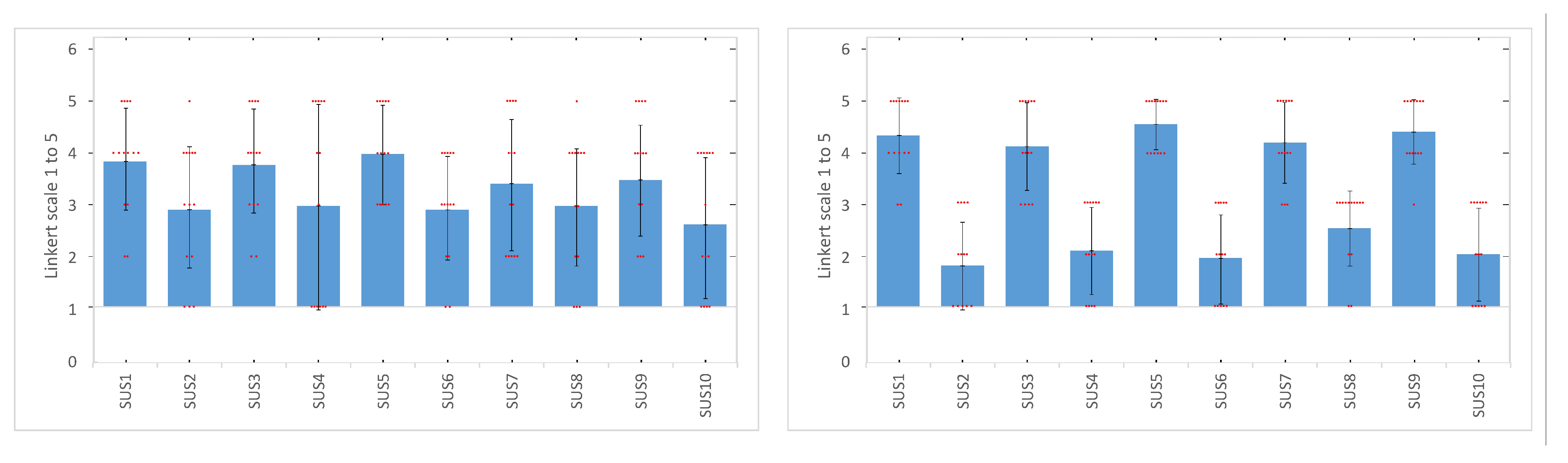

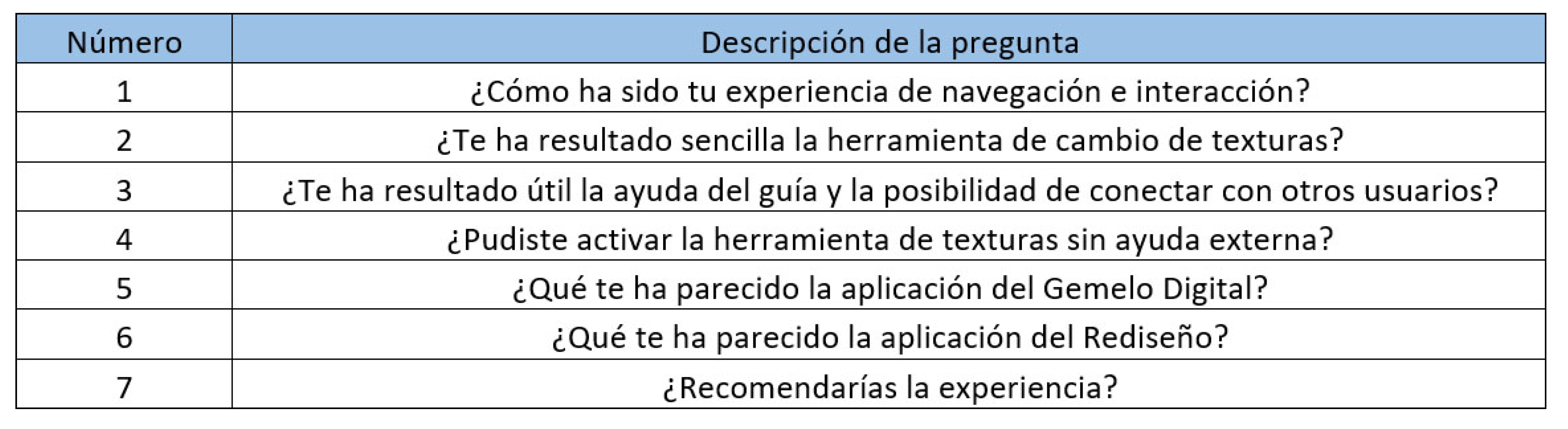

For its part, the SUS is a 10-question questionnaire designed to evaluate the usability of technological systems and products, such as websites, applications, and devices. It was developed in 1986 by John Brooke and is widely used because it is quick, easy to administer, and effective in obtaining a general measure of usability. The 10 questions are detailed in

Figure 25, and users must answer them after interacting with the system or product. The questions alternate between positive and negative statements to reduce bias and cover aspects of system usability and learning. Each statement is evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The SUS provides a scoring system from 0 to 100. It does not represent a percentage, but rather allows for the comparison of the relative usability of different systems and determines whether a system is easy or difficult to use (See

Figure 26). The formula can be expressed mathematically as follows: In this formula, the variables from Q1 to Q2 are the answers to the 10 questions. To evaluate the responses of all the tests, the mean and standard deviation are calculated.

3. Results

In this section, we detail the generated MV applications, case 1 (Digital Twin) and case 2 (Stand Redesign). To this end, a video demonstration of both applications has been created, where one of the users uses the Meta Quest 3 glasses model and another user navigates from a laptop (See

Figure 27). The two users previously completed the tutorial to familiarize themselves with the application.

Video Case 1 Video Case 2 (Consulted on October 31, 2024) Upon entering the immersive space, users could freely navigate both virtual stands, discover the client’s textile products, and modify the fabrics of the furniture. They were connected with the same Spatial.io account so they could interact with each other simultaneously from different devices (See

Figure 28).

Figure 29 shows details of the virtual stage of the Digital Twin, where the exhibitors, table, meeting chairs, and roll-ups can be seen. In

Figure 29, details of the redesigned stage are shown, where the different sections of the stand can be seen and how the avatar can sit on the sofa and configure, from the programmed carousel, the different upholstery textures. The ability to configure the fabrics in real time and see their application on the furniture surprised the users.

Different behaviors were recorded: in the case of the VR glasses user, the sense of immersion was greater, as well as a certain feeling of dizziness. He spent more time observing the screens and the furniture. In contrast, the portable PC user spent more time experimenting with the tools for running or jumping, as well as the socialization features of the Statial platform: chat, performing dances, and sending emoticons. The VR user focused more on exploring and moving through the space because they were curious about the spatial design.

Between both users, the interaction was smooth. Emojis and text messages were exchanged, initiating a conversation about the appearance of the stand, which demonstrates the improvement of the virtual experience. The VR user reported difficulty handling some menus and icons, as well as experiencing some dizziness if the navigation was too abrupt.

The analysis was applied to a total of 14 users. The demographic balance was as follows: half indicated they were men and the other half women. The demographic balance was as follows: 7.14% were under 18 years old, and 35.71% were between 18 and 25 years old. Between 25 and 40 years old, they made up 28.57%, and between 40 and 55 years old, they represented 21.43%. Finally, the group aged between 55 and 70 years represented 7.14%. Regarding academic education, 28.57% had basic studies, 50% were graduates, and 21.43% had a postgraduate degree. Regarding the use of these technologies, 42.86% stated that they used them daily, either at work or for leisure in video games or watching movies. 21.43% stated that they used them occasionally. Finally, they were asked if they had already had experiences with the MV and 28.57% responded affirmatively.

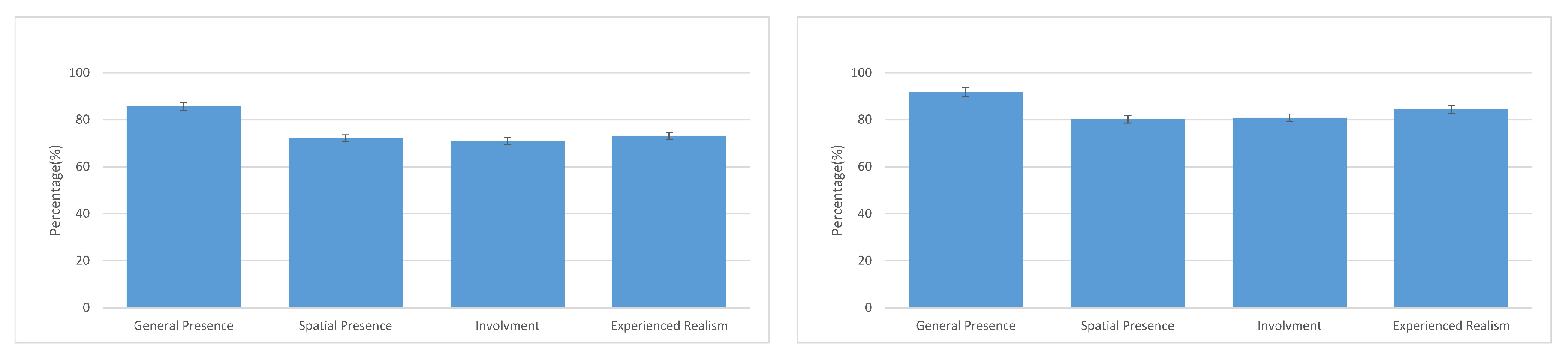

In the following figures (See

Figure 30 and

Figure 31), the data obtained from the IPQ can be appreciated, for case 1 (Digital Twin) and case 2 (Redesign). In

Figure 30, the mean and standard deviation for each question of the IPQ are indicated. In

Figure 31, each subscale of the questionnaire is indicated in percentage, with respect to the mean and the deviation obtained in the questionnaires. The data obtained, for case 1, indicate that 85.71% of the respondents experienced a General Presence, with a deviation of 1.52%. This indicates that the users had a high sense of immersion within the Visual Environment. (VE). Regarding Spatial Presence, a score of 72.11% with a deviation of 1.19% was obtained, indicating that users felt physically present within the digital twin of the stand. 70.92% of the respondents, with a deviation of 1.35%, stated that they had a high level of engagement within the VE. Regarding the Experienced Realism, 73.21% of the respondents, with a deviation of 1.05%, stated that they felt immersed within the VE. These data support our first objective, to create a digital twin of the physical stand, so that customers from anywhere in the world can access the manufacturer’s news without the need to travel to the Promotional Fair.

Regarding the data obtained for case 2 (redesign of the physical stand), it can be observed that the respondents rated it better than the digital twin. In General Presence, 91.84% of the respondents, with a standard deviation of 0.94%, stated that they felt a strong presence within the VE, 6.13% more than in case 1. Regarding Spatial Presence, users felt physically present 80.27% of the time with a deviation of 1.04%, 8 points more than in the first case. 80.87%, with a deviation of 1.2%, indicated that their participation in the VE was active, almost 10% more than in the case of the digital twin. And finally, in the section on Experienced Realism, 84.44% of users, with a standard deviation of 1.3%, reported a constant immersion in the VE, 11.23% more than in the previous case. This reinforces our initial hypothesis, where we expressed the lack of design and artistic criteria in the creation of virtual worlds. With the data in hand, it is observed that users have a better sense of the immersive space if it is created based on the basic principles of Design. Regarding the data obtained from the SUS questionnaire, for the first case, 73.39% of the respondents, with a standard deviation of 7.26%, indicated that the usability of the application was high. For the second case, the result was 88.04%, with a deviation of 3.35%. (See

Figure 32). It is worth noting that the majority agreed with the advantages of this type of applications and expressed their intention to use them more frequently. They stated that the experience had been gratifying, smooth, easy to learn, and use. This data supports our hypothesis that with a good design study, it is possible to improve the experience and usability of VR and MV applications.

4. Discussion

The public presentation of the two applications took place at Home Textiles Premium, by Textilhogar, during the Feria Hábitat València 2024, held from September 30 to October 3, 2024. Taking advantage of the fact that the manufacturer was exhibiting with a physical stand, this space was used to allow users to visit the two virtual stands.

A Meta Quest 3 headset and a laptop connected to a television screen were used for the demonstration, allowing visitors to observe in real-time how users navigated through the virtual stands. Before each test, one of the authors of this article explained to each user the operation of each device and the functions within Spatial.io. The author entered the virtual stands from their mobile device and acted as a guide, showing the users the functionalities of the stands. Once he was able to confirm that the user was navigating the application smoothly, they were given complete freedom to test each of its functions.

The two applications, digital twin and redesign, were presented to the textile specialist audience as new tools to complement physical stands, allowing for better interaction with customers from anywhere in the world, creating new sales channels, and providing a new platform for training and presenting new products for the brand. After the experience, users were invited to fill out a small questionnaire of 7 questions (See

Figure 33) about the applications of the virtual stands and their experience in the MV. Twenty-five users aged between 30 and 65 responded to the survey, which aimed to measure interaction with the furniture, the correct use of the texture selector, and navigation through the space.

The user could respond on a scale from 5 ("Very satisfactory") to 1 ("Very unsatisfactory"). The average score obtained was 4.1, with a standard deviation of 1.1, which indicates that the user was satisfied with the experience. Only three respondents rated any question with a value of 1, as they encountered difficulties navigating with the VR glasses. 75% of the users expressed satisfaction with the use of the texture carousel, and only two had problems applying it to the upholstery of the furniture. These revealing data will serve to improve both the explanatory tutorial and to add visual aids within the virtual environment, to guide the user in better handling the internal tools of the application. In general, the experience for most users was satisfactory, but they later indicated some improvements to be made, such as integrating a voice-over, designing some interactive aids, anticipating the experience through a virtual tour explaining the application’s functionalities, and slight graphical improvements.

At first, the comments triggered the "Wow, I love it" effect, and as the user explored the space, the "but" effects were indicated in the form of constructive suggestions for improvement options: "It’s very fun and useful for visualizing textures in real time, but it makes you a bit dizzy," "Can this type of application be applied to other sectors like furniture or ceramics?" "I was a bit lost at first, but then I felt completely integrated into the stand." It’s a very useful tool. (Opiniones literales).

These valuable responses were used for subsequent improvements, especially in the previous tutorial (See

Figure 34). Explanatory text was removed and more graphic information was added. Explanatory signs were also inserted to indicate the functions of the keyboard to the user. In

Figure 34, some examples of the new explanatory signs added can be seen. In

Figure 35, visual aids can be seen to improve the use of the carousel. These changes aim to improve navigation and UX in the immersive space. For the future, it is planned to expand the number and diversity of users, as well as the number of virtual reality glasses, to study the interaction among a larger number of users and the possible relationships between them, via chat, voice, etc...[

46]. Improvements and updates made to the Spatial Toolkit Creator will also be studied and applied to the applications if deemed appropriate.

It is important to highlight that applications like those presented in this article can assist and be very useful to the textile industrial sector to improve their sales [

48] by presenting their products in a different and interactive way. Sectors such as tourism [

49] hospitality [

50] marketing [

51] or fashion and accessories design [

52] are already benefiting. But, on the other hand, it is necessary to take into account aspects such as privacy and data protection for those who interact with the application. The tests conducted for this study have been anonymous, but in the future, the client may need this information, so existing legal regulations regarding privacy and data protection must be taken into account[

53,

56]. Although it is a tool that facilitates connection between people around the world [

57] accessibility, and inclusion, it is true that it will never fully replace human relationships.

An important aspect is the sustainability and environmental impact of future display devices. They should shift towards elements that are less polluting and recyclable, just as has happened in the mobile industry, where devices have reduced in size and materials have become more environmentally friendly; VR tools will undergo the same transformation. It should be noted that Meta already has a prototype of VR glasses, the Orion (See

Figure 36) which are lighter, more sustainable, and more powerful than the existing Meta Quest 3. For now, they have a very high price, but everything indicates that they will become a technological object for everyday use, grouped into a single device, alongside current mobile phones, watches, cameras, or headphones, etc. and with the possibility of enjoying VR or AR.

Figure 1.

Detail of the Fornite game and its Samsumg skin.

Figure 1.

Detail of the Fornite game and its Samsumg skin.

Figure 2.

Schemes of the methodologies followed for cases 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Schemes of the methodologies followed for cases 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Isometric view and floor plan of the 3D modeling of the physical stand.

Figure 3.

Isometric view and floor plan of the 3D modeling of the physical stand.

Figure 4.

Detail of the color chart. The base colors will focus on these three RGB colors.

Figure 4.

Detail of the color chart. The base colors will focus on these three RGB colors.

Figure 5.

Detail of the designed door and the Principle of Simplicity applied to the doors.

Figure 5.

Detail of the designed door and the Principle of Simplicity applied to the doors.

Figure 6.

Principles of Hierarchy and Symmetry, applied in the composition of elements.

Figure 6.

Principles of Hierarchy and Symmetry, applied in the composition of elements.

Figure 7.

Principle of Clarity applied.

Figure 7.

Principle of Clarity applied.

Figure 8.

Principle of Symmetry applied to the ground.

Figure 8.

Principle of Symmetry applied to the ground.

Figure 9.

Final appearance of the redesigned stand.

Figure 9.

Final appearance of the redesigned stand.

Figure 10.

3D furniture applied to the virtual stand.

Figure 10.

3D furniture applied to the virtual stand.

Figure 11.

Detail of the carousel designed to change the textures of the furniture.

Figure 11.

Detail of the carousel designed to change the textures of the furniture.

Figure 12.

Unity folder menu and template folder hierarchy.

Figure 12.

Unity folder menu and template folder hierarchy.

Figure 13.

Texture and Detail Selection Menu for the Viewport.

Figure 13.

Texture and Detail Selection Menu for the Viewport.

Figure 14.

Detail of the programmed buttons and the Close Button.

Figure 14.

Detail of the programmed buttons and the Close Button.

Figure 15.

Detail of the text component.

Figure 15.

Detail of the text component.

Figure 16.

Detail of the sample spheres and detail of the Interactable menu.

Figure 16.

Detail of the sample spheres and detail of the Interactable menu.

Figure 17.

Editing each button to assign it to its corresponding texture.

Figure 17.

Editing each button to assign it to its corresponding texture.

Figure 18.

Detail of the Text component.

Figure 18.

Detail of the Text component.

Figure 19.

In the Properties panel, we define the name of the texture so that it applies to the carousel.

Figure 19.

In the Properties panel, we define the name of the texture so that it applies to the carousel.

Figure 20.

Detail on how to define the texture icons.

Figure 20.

Detail on how to define the texture icons.

Figure 21.

Detail of the Int_Open and Int_Close components

Figure 21.

Detail of the Int_Open and Int_Close components

Figure 22.

Detail on how to correctly define the background of the carousel.

Figure 22.

Detail on how to correctly define the background of the carousel.

Figure 23.

Detail of the Empty Frame from Spatial.io, to define multimedia content.

Figure 23.

Detail of the Empty Frame from Spatial.io, to define multimedia content.

Figure 24.

Table with the IPQ issues

Figure 24.

Table with the IPQ issues

Figure 25.

Table with the issues of the SUS.

Figure 25.

Table with the issues of the SUS.

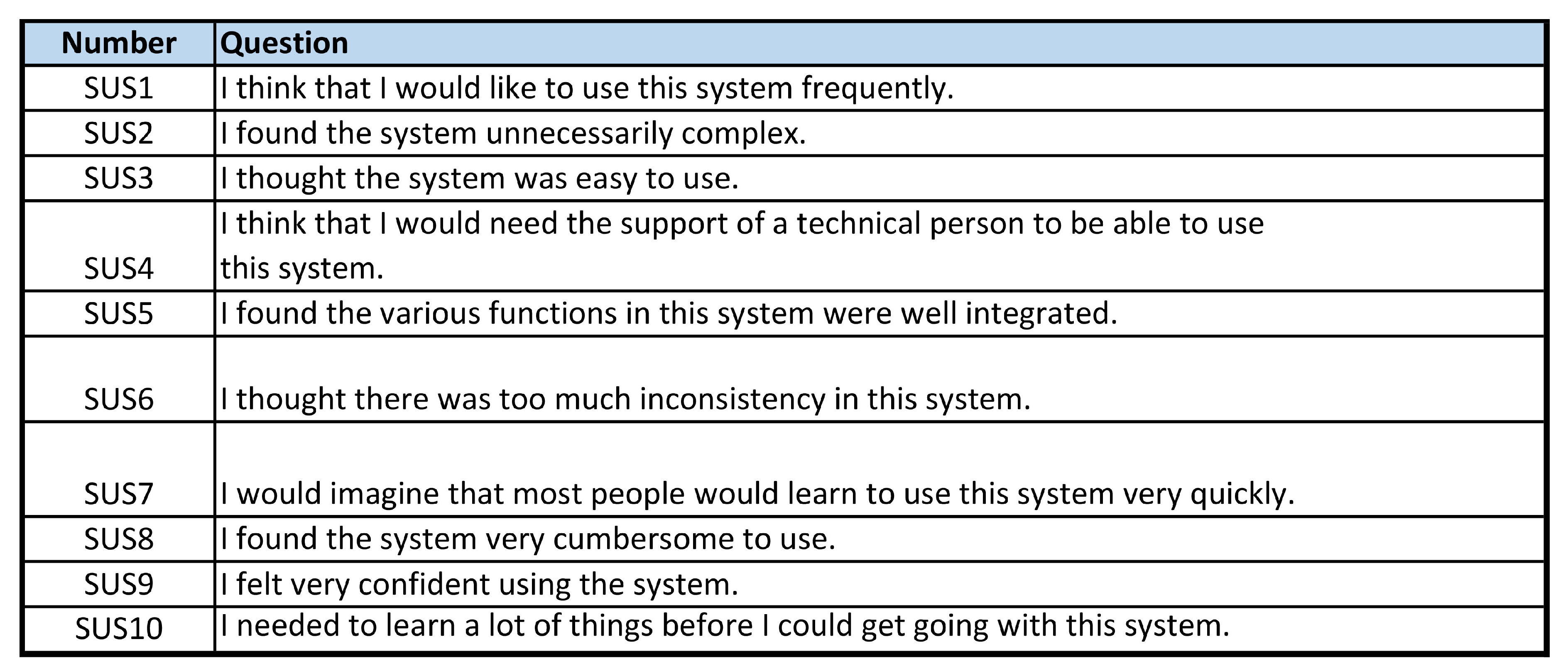

Figure 26.

Ecuación que define el sistema SUS.

Figure 26.

Ecuación que define el sistema SUS.

Figure 27.

Image of one of the couples who took the tests in case 1 and 2.

Figure 27.

Image of one of the couples who took the tests in case 1 and 2.

Figure 28.

Screenshots of the MV application, for case 1.

Figure 28.

Screenshots of the MV application, for case 1.

Figure 29.

Screenshots of the MV application, for case 2.

Figure 29.

Screenshots of the MV application, for case 2.

Figure 30.

Result of the IPQ obtained for both cases. The red dots show the obtained data, the blue bars the mean, and the vertical lines the standard deviation.

Figure 30.

Result of the IPQ obtained for both cases. The red dots show the obtained data, the blue bars the mean, and the vertical lines the standard deviation.

Figure 31.

Result of the IPQ subscales for both cases. The blue bars define the mean and the vertical lines, the standard deviation.

Figure 31.

Result of the IPQ subscales for both cases. The blue bars define the mean and the vertical lines, the standard deviation.

Figure 32.

SUS results obtained for both cases. The red dots show the obtained data, the blue bars the mean, and the vertical lines the standard deviation.

Figure 32.

SUS results obtained for both cases. The red dots show the obtained data, the blue bars the mean, and the vertical lines the standard deviation.

Figure 33.

Detail of the questionnaire delivered after the immersive experience.

Figure 33.

Detail of the questionnaire delivered after the immersive experience.

Figure 34.

Detail of the built-in control menu, to facilitate navigation.

Figure 34.

Detail of the built-in control menu, to facilitate navigation.

Figure 35.

Detail of the incorporated floating menu, to better understand the functioning of the carousel

Figure 35.

Detail of the incorporated floating menu, to better understand the functioning of the carousel

Figure 36.

Mark Zuckerberg presenting Meta’s new glasses, the Orion.

Figure 36.

Mark Zuckerberg presenting Meta’s new glasses, the Orion.