Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Observation Analysis

2.1. Data

2.2. Structure of the MCS and Identification of Bore

2.3. Large Scale Environment

3. Numerical Simulation

3.1. Experiment Design

3.2. Evaluation of the Model Simulation

4. Dynamic and Thermodynamic Structures of Bore formation and Its Role on CI

4.1. Horizontal Pattern

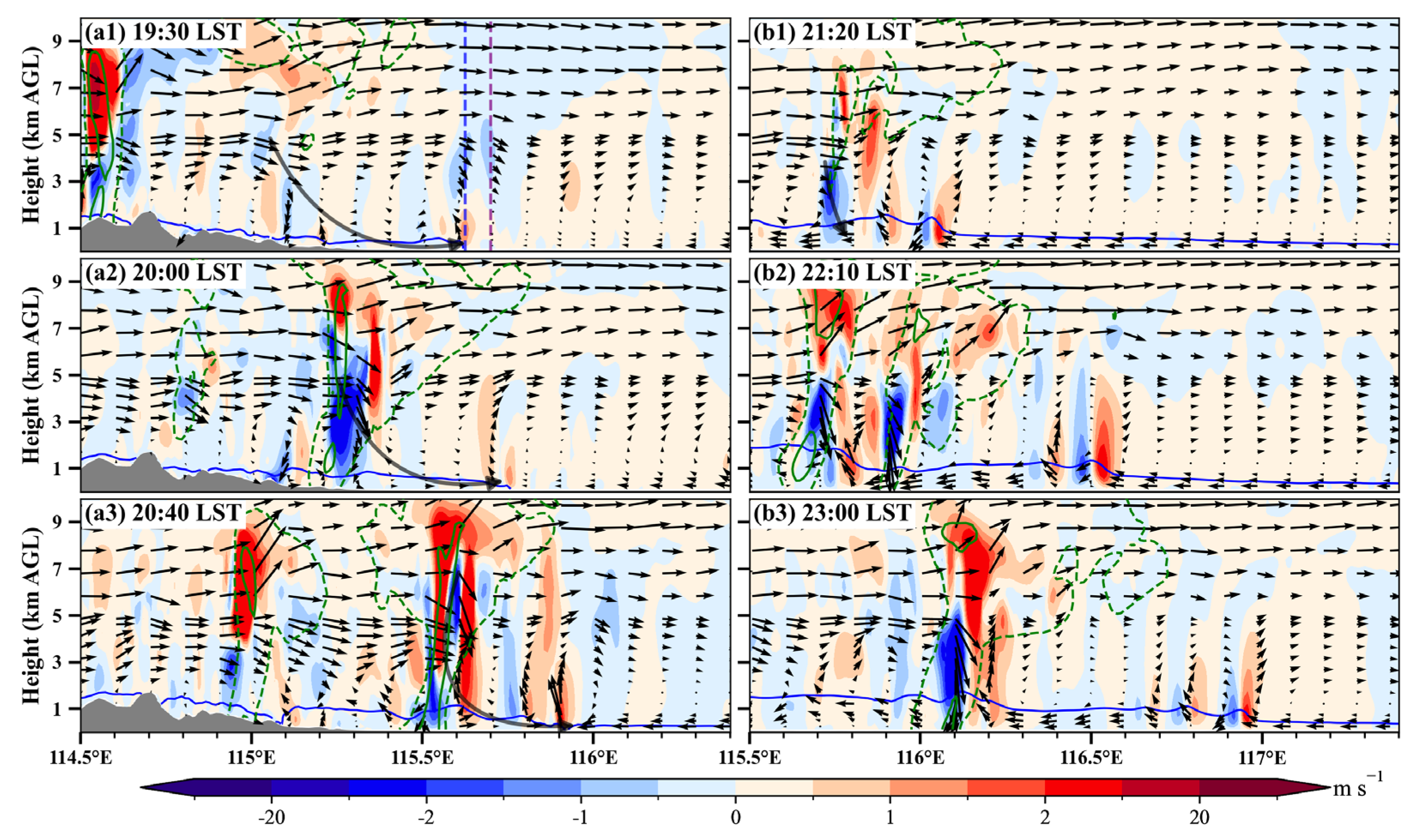

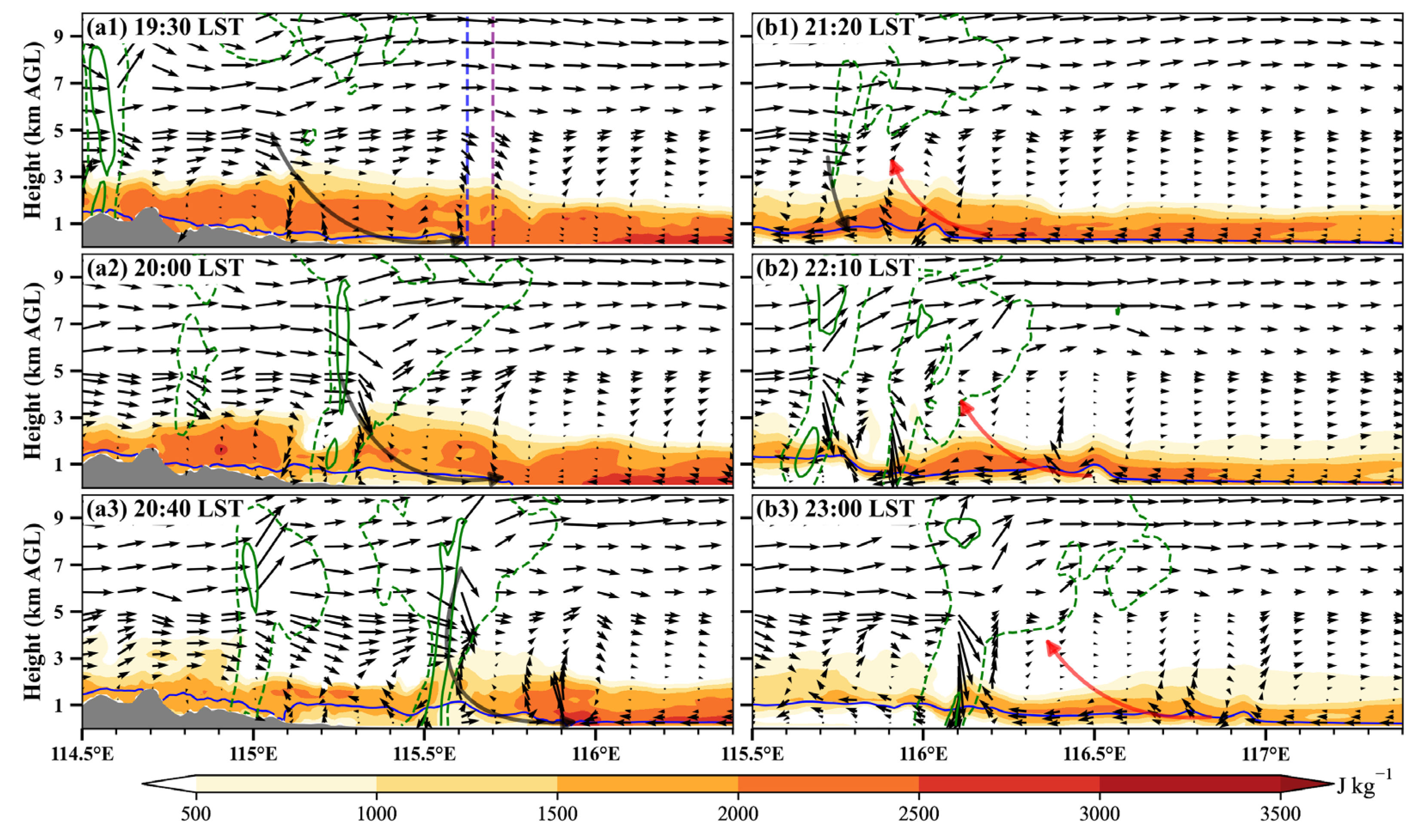

4.2. Dynamic and Thermodynamic Processes of Bore Formation

4.3. Role of the Undular Bore on the CI

5. Dynamics Governing of Bore Formation

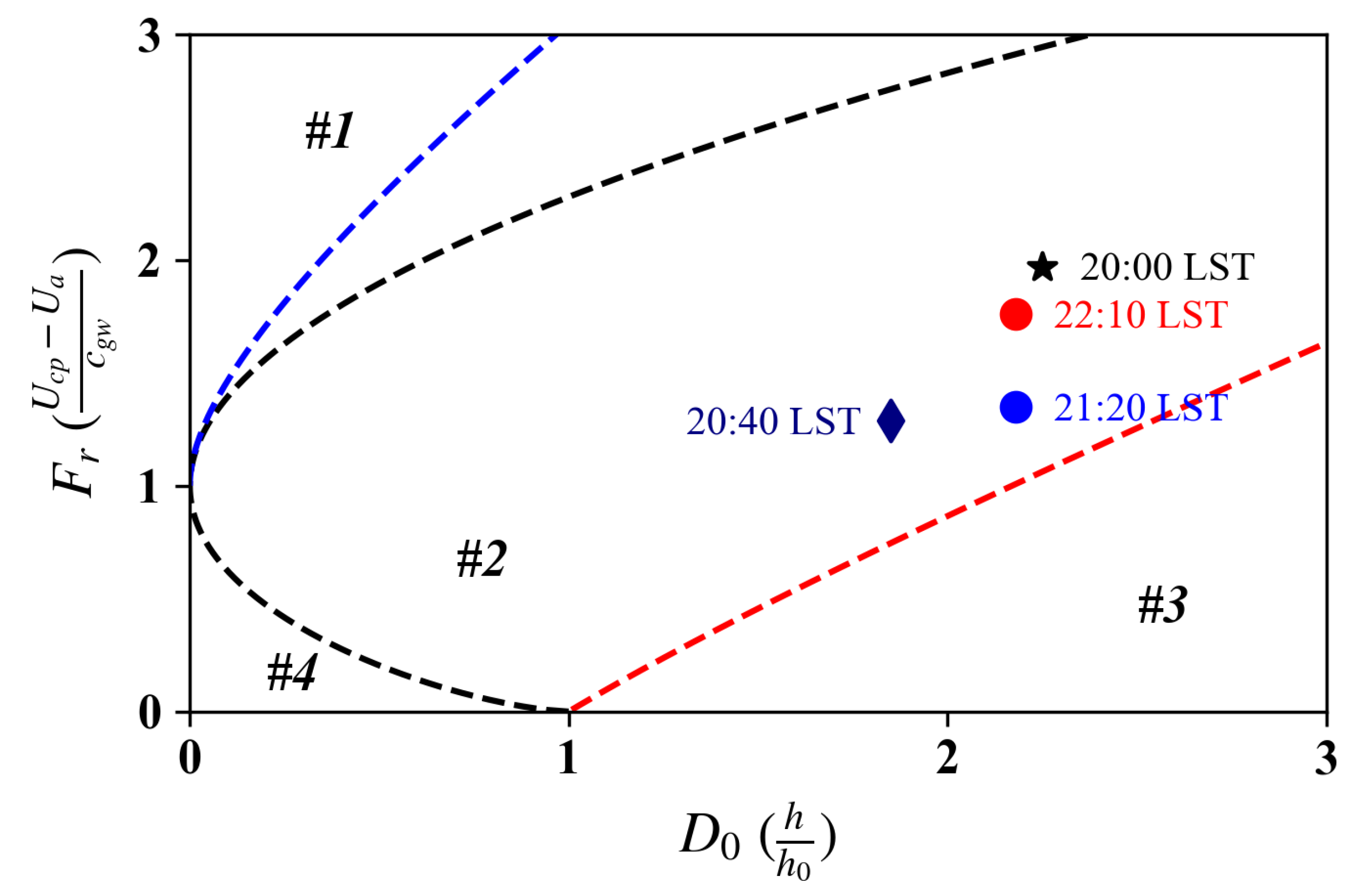

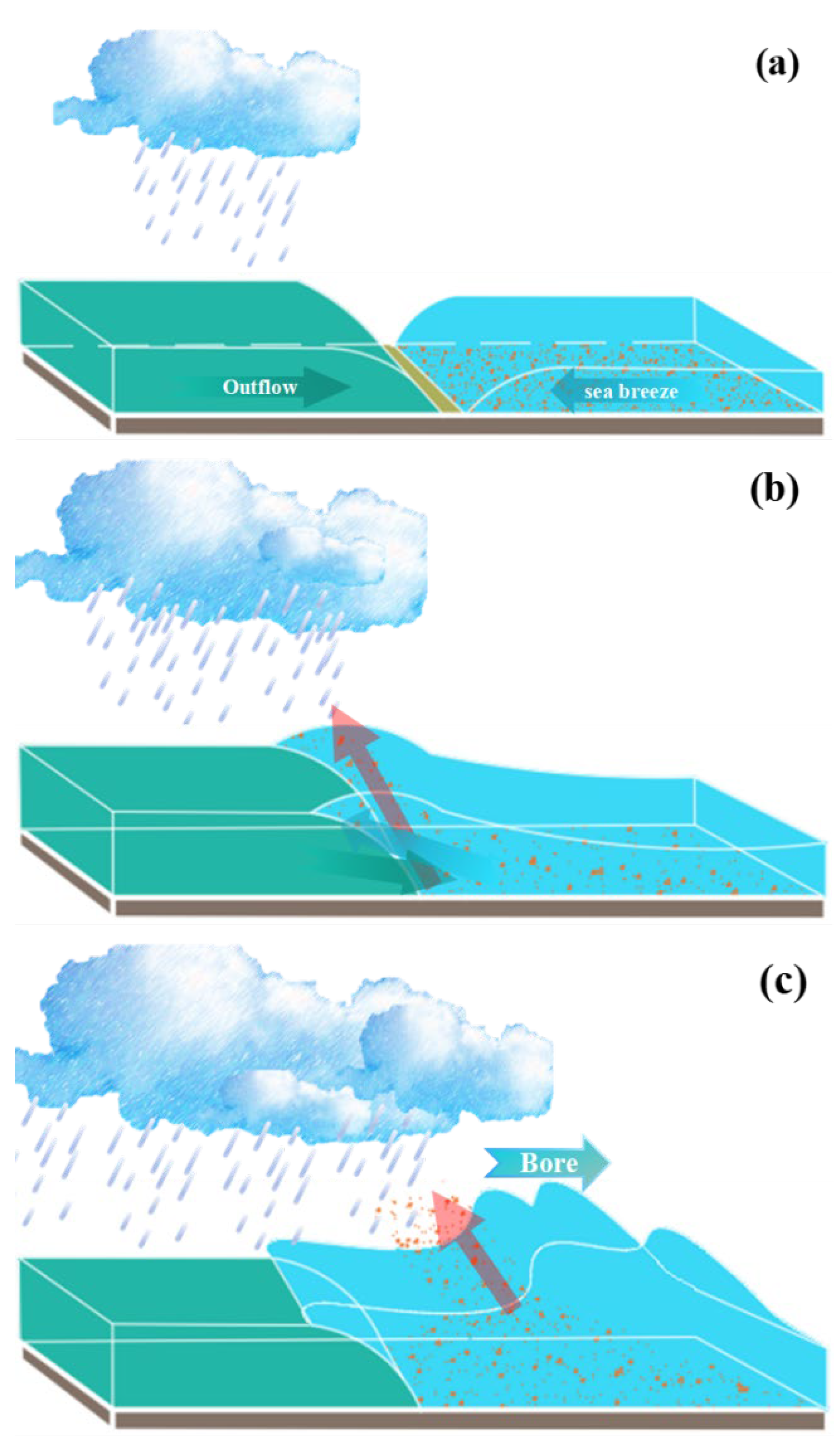

5.1. Classic Hydraulic Theory: Physical Mechanism of Bore Formation

5.2. Role of the Strong Convective Downdraft in Bore Formation

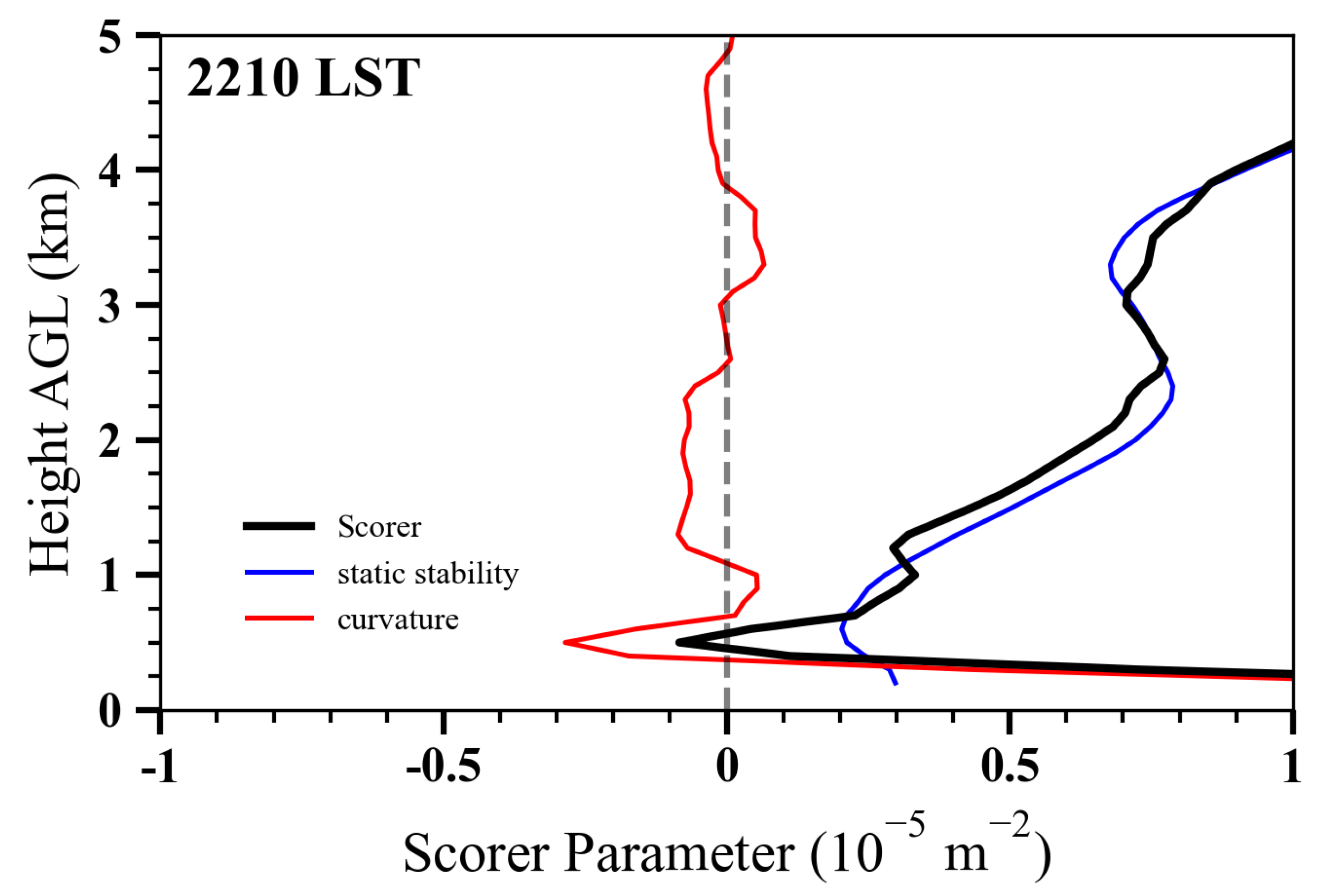

5.3. Waveguide Effect of LLJ

6. Summary and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knupp, K. Observational Analysis of a Gust Front to Bore to Solitary Wave Transition within an Evolving Nocturnal Boundary Layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 2006, 63, 2016–2035. [CrossRef]

- Haghi, K.R.; Parsons, D.B.; Shapiro, A. Bores Observed during IHOP_2002: The Relationship of Bores to the Nocturnal Environment. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2017, 145, 3929–3946. [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.; Reeder, M.J.; Lane, T.P. A climatology of atmospheric pressure jumps over southeastern Australia. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2017, 143, 439-449. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.E. Gravity Currents: In the Environment and the Laboratory, 2d ed; Cambridge University Press, 1997; pp. 244. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.H. The morning glory: An atmospheric hydraulic jump. J. Appl. Meteor. 1972, 11, 304–311. [CrossRef]

- Crook, N.A. Trapping of low-level internal gravity-waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 1988, 45, 1533–1541. [CrossRef]

- Haghi, K.R.; Geerts, B.; Chipilski, H.G.; Johnson, A.; Degelia, S.; Imy, D.; Parsons, D.B.; Adams-Selin, R.D.; Turner, D.D.; Wang, X. Bore-ing into nocturnal convection. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2019, 100, 1103–1121. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.H. Fair weather nocturnal inland wind surges and atmospheric bores. Part II: internal atmospheric bores in northern Australia. Aust. Meteor. Mag. 1983, 31, 147–160.

- Clarke, R.H. Colliding sea-breezes and the creation of internal atmospheric bore waves: Two-dimensional numerical studies. Aust. Meteor. Mag. 1984, 32, 207–226.

- Smith, R.K. Evening glory wave-cloud lines in northwestern Australia. Aust. Meteor. Mag. 1986, 34, 27–33.

- Noonan, J.A.; Smith, R.K. Sea-Breeze Circulations over Cape York Peninsula and the Generation of Gulf of Carpentaria Cloud Line Disturbances. J. Atmos. Sci. 1986, 43, 1679–1693. [CrossRef]

- Noonan, J.A.; Smith, R.K. The generation of North Australian cloud lines and the morning glory. Aust. Meteor. Mag. 1987, 35, 31–45.

- Wakimoto, R.M.; Kingsmill, D.E. Structure of an Atmospheric Undular Bore Generated from Colliding Boundaries during CaPE. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1995, 123, 1374–1393. [CrossRef]

- Kingsmill, D.E.; Crook N.A. An Observational Study of Atmospheric Bore Formation from Colliding Density Currents. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2003, 131, 2985–3002. [CrossRef]

- Karan, H.; Knupp, K. Radar and Profiler Analysis of Colliding Boundaries: A Case Study. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2009, 137, 2203–2222. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Grasmick, C.; Geerts, B.; Wang, Z.; Deng, M. Convection Initiation and Bore Formation Following the Collision of Mesoscale Boundaries over a Developing Stable Boundary Layer: A Case Study from PECAN. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2021, 149, 2351–2367. [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.E.; Dorian, P.B.; Ferrare, R.; Melfi, S.H.; Skillman, W.C.; Whiteman, D. Structure of an Internal Bore and Dissipating Gravity Current as Revealed by Raman Lidar. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1991, 119, 857–887. [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.E.; Feltz, W.; Fabry, F.; Pagowski, M.; Geerts, B.; Bedka, K.M.; Miller, D.O.; Wilson, J.W. Turbulent Mixing Processes in Atmospheric Bores and Solitary Waves Deduced from Profiling Systems and Numerical Simulation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2008, 136, 1373–1400. [CrossRef]

- Blake, B.T.; Parsons, D.B.; Haghi, K.R.; Castleberry, S.G. The Structure, Evolution, and Dynamics of a Nocturnal Convective System Simulated Using the WRF-ARW Model. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2017, 145, 3179–3201. [CrossRef]

- Grasmick, C.; Geerts, B.; Turner, D.D.; Wang, Z.; Weckwerth, T.M. The Relation between Nocturnal MCS Evolution and Its Outflow Boundaries in the Stable Boundary Layer: An Observational Study of the 15 July 2015 MCS in PECAN. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2018, 146, 3203–3226. [CrossRef]

- Loveless, D.M.; Wagner, T.J.; Turner, D.D.; Ackerman, S.A.; Feltz, W.F. A composite perspective on bore passages during the PECAN campaign. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2019, 147, 1395–1413. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Parsons, D.B.; Wang, Y. Wave Disturbances and Their Role in the Maintenance, Structure, and Evolution of a Mesoscale Convection System. J. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 77, 51–77. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Parsons, D.B.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Abulikemu, A.; Shen, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S. A modeling study of an atmospheric bore associated with a nocturnal convective system over China. J. Geophys. Res. 2020, 125, e2019JD032279. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Parsons, D.B.; Xu, X.; Huang, H.; Xu, F.; Wu, T.; Chen, G.; Abulikemu, A.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, Y. The development of atmospheric bores in non-uniform baroclinic environments and their roles in the maintenance, structure, and evolution of an MCS. J. Geophys. Res. 2024, 129, e2023JD039319. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, D.; Geerts, B.; Wang, Z.; Deng, M.; Grasmick, C. Evolution and Vertical Structure of an Undular Bore Observed on 20 June 2015 during PECAN. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2017, 145, 3775–3794. [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, T.M.; Hanesiak, J.; Wilson, J.W.; Trier, S.B.; Degelia, S.K.; Gallus, W.A.; Roberts R.D.; Wang, X. Nocturnal Convection Initiation during PECAN 2015. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2019, 100, 2223-2239. [CrossRef]

- Scorer, R.S. Theory of waves in the lee of mountains. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1949, 75, 41–56. [CrossRef]

- Haghi, K.R.; Durran, D.R. On the Dynamics of Atmospheric Bores. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 78, 313–327. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.B.; Haghi, K.R.; Halbert, K.T.; Elmer, B.; Wang, J. The potential role of atmospheric bores and gravity waves in the initiation and maintenance of nocturnal convection over the Southern Great Plains. J. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 76, 43–68. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.R.; Lapworth, A. Initiation and Propagation of an Atmospheric Bore in a Numerical Forecast Model: A Comparison with Observations. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 2017, 56, 2999-3016. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.R.; Johnson, R.H. An Observational and Modeling Study of an Atmospheric Internal Bore during NAME 2004. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2008, 136, 4150–4167. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, K. Kumjian, M.R. Observations of the Discrete Propagation of a Mesoscale Convective System during RELAMPAGO–CACTI. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2022, 150, 2111–2138. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Parsons, D.B.; Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Wu, T.; Xu, F.; Wei, N.; Chen, G. Bores observed during the warm season of 2015–2019 over the southern North China Plain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL099205. [CrossRef]

- Rottman, J.W.; Simpson, J.E. The formation of internal bores in the atmosphere: A laboratory model. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1989, 115, 941–963. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K. Travelling waves and bores in the lower atmosphere: the 'morning glory' and related phenomena. Earth Sci. Rev. 1998, 25, 267-290. [CrossRef]

- Skamarock, W.; Klemp, J.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.; Huang, X. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Model Version 4.1. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Chen, S.; Gourley, J.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, A.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C. Coverage of China New Generation Weather Radar Network. Adv. Meteorol. 2019, 2019, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Li, W.; Bai, L.; Meng, X. General features of radar-observed boundary layer convergence lines and their associated convection over a sharp vegetation-contrast area. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 2865–2873. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; Schepers, D.; Simmons, A.; Soci, C.; Dee, D.; Thépaut, J-N. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present [Dataset]. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2023. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Field, P.R.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Hall, W.D. Explicit Forecasts of Winter Precipitation Using an Improved Bulk Microphysics Scheme. Part II: Implementation of a New Snow Parameterization. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2008, 136, 5095-5115. [CrossRef]

- Mlawer, E.J.; Taubman S.J.; Brown P.D.; Iacono M.J.; Clough, S.A. Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 16663-16682. [CrossRef]

- Dudhia, J. Numerical study of convection observed during the winter monsoon experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. J. Atmos. Sci. 1989, 46, 3077-3107. [CrossRef]

- Janjic, Z. The surface layer in the NCEP Eta Model. Eleventh Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, Norfolk, VA, 19-23 August 1996. Amer. Meteor. Soc., Boston, MA, 354-355.

- Chen, F.; Dudhia, J. Coupling an Advanced Land Surface–Hydrology Model with the Penn State–NCAR MM5 Modeling System. Part I: Model Implementation and Sensitivity. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2001, 129, 569-585. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, G.L.; Yamada T. Development of a turbulence closure model for geophysical fluid problems. Rev. Geophys. 1982, 20, 851-875. [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Dévényi D. A generalized approach to parameterizing convection combining ensemble and data assimilation techniques. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Milbrandt, J.A. Parameterization of cloud microphysics based on the prediction of bulk ice particle properties. Part I: Scheme description and idealized tests. J. Atmos. Sci. 2015, 72, 287–311. [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Xu, X.; Xue, M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, K. On the Key Dynamical Processes Supporting the 21.7 Zhengzhou Record-breaking Hourly Rainfall in China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 40, 337–349. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ju, Y.; Liu. Q.; Zhao, K.; Xue, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, A.; Tang, Y. Dynamics of two episodes of high winds produced by an unusually long-lived quasi-linear convective system in South China. J. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 81, 1449-1473. [CrossRef]

- Haertel, P.T.; Johnson, R.H.; Tulich, S.N. Some simple simulations of thunderstorm outflows. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58, 504–516. [CrossRef]

- Haase, S.P.; Smith, R.K. The numerical simulation of atmospheric gravity currents. Part II. Environments with stable layers. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 1989, 46, 35–51. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Moncrieff, M.W. Simulated density currents in idealized stratified environments. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2000, 128, 1420–1437. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ni, X.; Zhang, F. Decreasing trend in severe weather occurrence over China during the past 50 years. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42310. [CrossRef]

| Domain #1 | Domain #2 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Spacing | 3 km | 1 km | |

| Horizontal dimensions | 2247 km × 2247 km | 1050 km × 1050 km | |

| Vertical sigma levels | 45 | 45 | |

| Model top pressure | 200 hPa | 200 hPa | |

| ICs and LBCs | EAR5 reanalysis | EAR5 reanalysis | |

| Microphysics | Thompson | Thompson | Thompson et al. 2008 [40] |

| Longwave radiation | RRTM | RRTM | Mlawer et al. 1997 [41] |

| Shortwave radiation | Dudhia | Dudhia | Dudhia 1989 [42] |

| Surface layer | Monin–Obukhov–Janjic | Monin–Obukhov–Janjic | Janjic 1996 [43] |

| Land surface model | Noah | Noah | Chen and Dudhia 2001 [44] |

| Boundary layer physics | MYJ | MYJ | Mellor and Yamada 1982 [45] |

| Cumulus parameterization | Grell and Dévényi | Grell and Dévényi | Grell and Dévényi 2002 [46] |

| 2000 LST | 2040 LST | 2120 LST | 2210 LST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | 540 | 550 | 550 | |

| 900 | 1000 | 1200 | 1200 | |

| 7.46 | 6.83 | 6.87 | 16.43 | |

| -8.64 | -8.51 | -9.88 | -7.99 | |

| 8.19 | 11.87 | 12.38 | 13.89 | |

| 1.97 | 1.29 | 1.35 | 1.76 | |

| 2.25 | 1.85 | 2.18 | 2.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).