Introduction

The cutaneous microbiome exerts a significant influence on host biology. While extensively studied in humans and vertebrates, research on invertebrate surface microbiota remains comparatively limited [

1,

2]. This disparity is likely due to two key factors: the greater stability of gut microbiomes compared to cutaneous microbiomes, facilitating less-contaminated sampling; and the inherently low biomass associated with the insects' exoskeletons [

1,

3], which pose challenges to cuticular microbiota identification.

The cuticular microbiota of a variety of terrestrial arthropods [

1], including

Drosophila [

3,

4,

5], spiders [

6], ants [

7,

8], and recently bees [

9,

10,

11] has been the subject of documented research. In particular, funnel-web spiders offer a valuable model for the study of host-microbe interactions on the exoskeleton

6. The available evidence suggests that these bacteria can influence host behaviour, thereby highlighting the critical role of surface microbiota regulation in host-microbe coevolution. Studies on ants demonstrate a correlation between body size and both the biomass and diversity of associated bacterial communities [

7,

8]. In general, the cuticle microbiota acts as a key barrier between the host and the external environment, as it is difficult for insects themselves to control the surface of their own cuticle [

1,

12].

The honeybee's environmental microbiota is believed to significantly impact pollen and bee bread processing, preservation, and ultimately, the nutritional quality of bee products [

2,

9,

10]. However, limited comprehensive metagenomic studies reveal that less than 2% of the bacterial population is independent of the gut microbiome. While this suggests potential variation in microbiota associated with other body regions, previous attempts at sequencing honeybee tissues excluding the gut have yielded inconclusive results .

To elucidate the composition of the honeybee's cuticular microbiota, researchers have employed both cultivation-based and molecular techniques [

9,

13,

14]. Recent studies on the cuticular microbiomes of Hymenoptera reveal distinct profiles between social and solitary bees. Solitary bees show greater microbial diversity, while honeybees have a more stable microbiota, reflecting their ecological roles. The high social interactions in honeybee colonies, such as allogrooming and co-cleaning, enhance microbiome stability, which partially overlaps with their gut microbiota. Studies show that predominant bacteria groups of honey bee surface include some “gut” species (

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Gilliamella, Bombella and Snodgrassella) and some possibly unique for this substrate (

Bacillus, Fructobacillus, Rhizobiales) [

9,

14]. These peculiar microorganisms, commonly associated with plant substrates, play a significant role in honeybee metabolism, particularly carbohydrate fermentation and utilization, and immune function [

15,

16]. The fungal component of the cuticular microbiota includes

Aureobasidium, Debaryomyces, Alternaria, Capnoidales, Metschnikowia, Saccharomyces, and

Melampsora. While many are plant pathogens, yeasts are also found alongside lactic acid bacteria in fresh honey and bee bread. The use of

Aureobasidium pullulans in biocontrol against plant pathogens suggests a potential influence of these microbial species on bee health and productivity [

17,

18].

This study addresses the knowledge gap regarding the honeybee surface microbiome by characterizing its composition and potential functions using both cultivation-based and molecular (16S rRNA and whole metagenome sequencing) techniques. We aimed to develop methods for effective cuticular microbiome research, elucidate the diversity, distribution and function of this microbiome across different body parts, building upon previous research demonstrating the influence of surface microbiota in other arthropods and the limited existing data on honeybees. Our investigation explores the hypothesis that this understudied microbiome plays a significant role in honeybee health, metabolism, and potentially contributes to colony resilience through interactions with both environmental and gut microbiota.

2. Methods

The standard media employed (GRM, GMF, Czapek, Sabouraud, Soy, A4, Gauze II; see

Supplementary Table 1) comprised both liquid and solid (20% agar) preparations. The bees (collected on 01/12/2021 from three hives) were stored individually at -20°C. To isolate cuticular microbes, five bees were held for one hour in sterile containers (150 mL), rinsed with 1 mL of water, and plated directly or after pre-enrichment in Czapek broth. Pure cultures were obtained by sequentially processing body parts (300-1200 µL wash/media), vortexing (1 min), and inoculating onto selective media (2–10 days incubation). Following this, enriched samples were plated in order to isolate pure lines. Further experiments were then conducted.

All obtained isolates were cultured on appropriate solid media. Their morphology and cellular structure were determined in unstained preparations and, if necessary, stained with methylene blue or Lugol solution, Gram and Zill-Nelsen stains. If all parameters coincided in isolates from the same source, they were considered identical and then only one of the lines was cultured, preserved and analyzed. In the article, the names of the crops correspond to their

Supplementary photos.

For experiments on “shedding” from the cuticle surface, inoculations were performed from initially sterile surfaces with which the bees were in contact. 5 bees were kept for one hour in sterile 150 ml containers. The containers were then rinsed with 1 ml of water, which was transferred to solid medium directly or first enriched in 10 ml of Czapek's nutrient medium.

A series of experiments were performed to select the optimum conditions for the development in the elective medium and to select techniques for flushing microbiomes. In the first one, after adding 1200 µl of water to the sample, the sample was vortexed for one minute, after which the flush and the sample itself were placed into a series of elective media (10 ml each) with varying pH from 6 to 8 in 0.2 increments. Every 24 hours, 1 ml of the elective medium was transferred to solid media for further separation of pure lines. Three different compositions of washing solutions were used: (1) distilled water; (2) 0.9% NaCl in water; (3) 0.001% SDS, 0.9% NaCl in water.

For extraction from the surface of the bees, the limbs were carefully separated from the body; the cuticle was incised from above and carefully separated. To avoid contamination, the lower part of the head and the last two segments of the abdomen were not used.

To determine the differences between the microbiota of the different parts of the surfaces, bees were cut with sterile needles, the intestines were removed and their microbiota were analyzed separately to exclude contamination: identical lines from the surface and from the intestines were not considered. Samples were placed in 300 μl of 0.9% NaCl solution, vortexed for one minute, and placed in 10 ml of a series of elective media with and without antimycotics added. The media were placed on a rocker for a week, from day 3 to day 15, 200 µl of media were transferred to solid media every other day to obtain isolates.

Tests for the production of antimicrobial compounds were performed. For the dot test, the test culture was transferred to the center of the petri dish and the inhibiting culture was transferred in 4 symmetrical dots at a distance of 2.5 cm from the center. For the line test, the suppressed culture was transferred along the diameter with a continuous stroke using a 2 mm thick glass rod. Perpendicular to it, the inhibitory culture was applied with 4-5 parallel strokes with a 2 mm glass rod. The size of the suppression zone was defined as the minimum distance between inhibiting and suppressed cultures. For CFU count and suppression zone measurement ImageJ was used [

19].

For metagenomics and 16S quantifications 10 bees were collected from three hives. After washing, samples were enriched on Czapek nutrient medium for 3 days and then sequenced. DNA isolation from isolates was performed using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. DNA library was quantified and quality-assured with a capillary electrophoresis TapeStation 4200 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For 16S rRNA sequencing we use Quick-16S NGS Library Prep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). 16S sequencing rRNA sequencing was performed using Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA), expected read length 250 bp.WGS sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA), expected read length 100 bp. Data available at BioProject PRJNA1048732.

16S amplicon sequencing data analysis was performed using QIIME 2 [

20] (version 2024.5.0). Following import, the DADA2 module [

21] was applied for data denoising. Taxonomy was assigned using naive Bayes classifiers with the SILVA [

22], GreenGenes [

23], and BEExact [

24] databases. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the IQ-TREE [

25] plugin (version 2.3.4). Metabolic annotation was carried out using the PICRUSt2 [

26] plugin (version 2.5.3).

WGS data trimming was performed using fastp [

27] (version 0.23.4) with a minimum quality threshold of Q20, a preference for front trimming, and a sliding window of size 10. For metagenomic annotation, comprehensive analysis was conducted using Kraken 2 [

28] (version 2.1.3) with Bracken [

29] (version 2.9) correction on the pre-built NCBI nucleotide database (nt). To annotate potential fungal metagenomic sequences, Kaiju [

30] (version 1.10.1) was employed with the pre-built RefSeq fungal sequences index.

To eliminate possible contamination, we compared our data with sequencing data from the same hive’s combs [

31] (BioProject PRJNA1048732) and with pan-metagenomic data [

9] (BioProject PRJNA879967). Host and human reads were removed using Bowtie 2 [

32] (version 2.5.2) with the ‘very-sensitive-local’ preset. Genomes for dehosting and decontamination are available in NCBI GenBank under the following IDs: GCA_003254395.2, GCA_029169275.1, GCA_000184785.2, GCA_000469605.1, GCA_014066325.1, GCA_000001405.29.

Metagenome assembly was performed using metaSPAdes [

33] and IDBA-UD [

34] (version 1.1.3). After quality control with MetaQUAST [

35] (version 5.2.0), IDBA-UD was selected with a k-mer step of 20 and k-mer sizes ranging from 16 to 116 which produced maximal N50. The PROKKA [

36] tool (version 1.14.5) was then used to perform metabolism reconstruction on the selected assembly.

For data visualization we use R [

37] with libraries tidyverse [

38], vegan [

39], ape [

40] and aRchiteutis [

41].

3. Results

The cultivation conditions and media were optimised through experimentation utilising a range of sample sources.

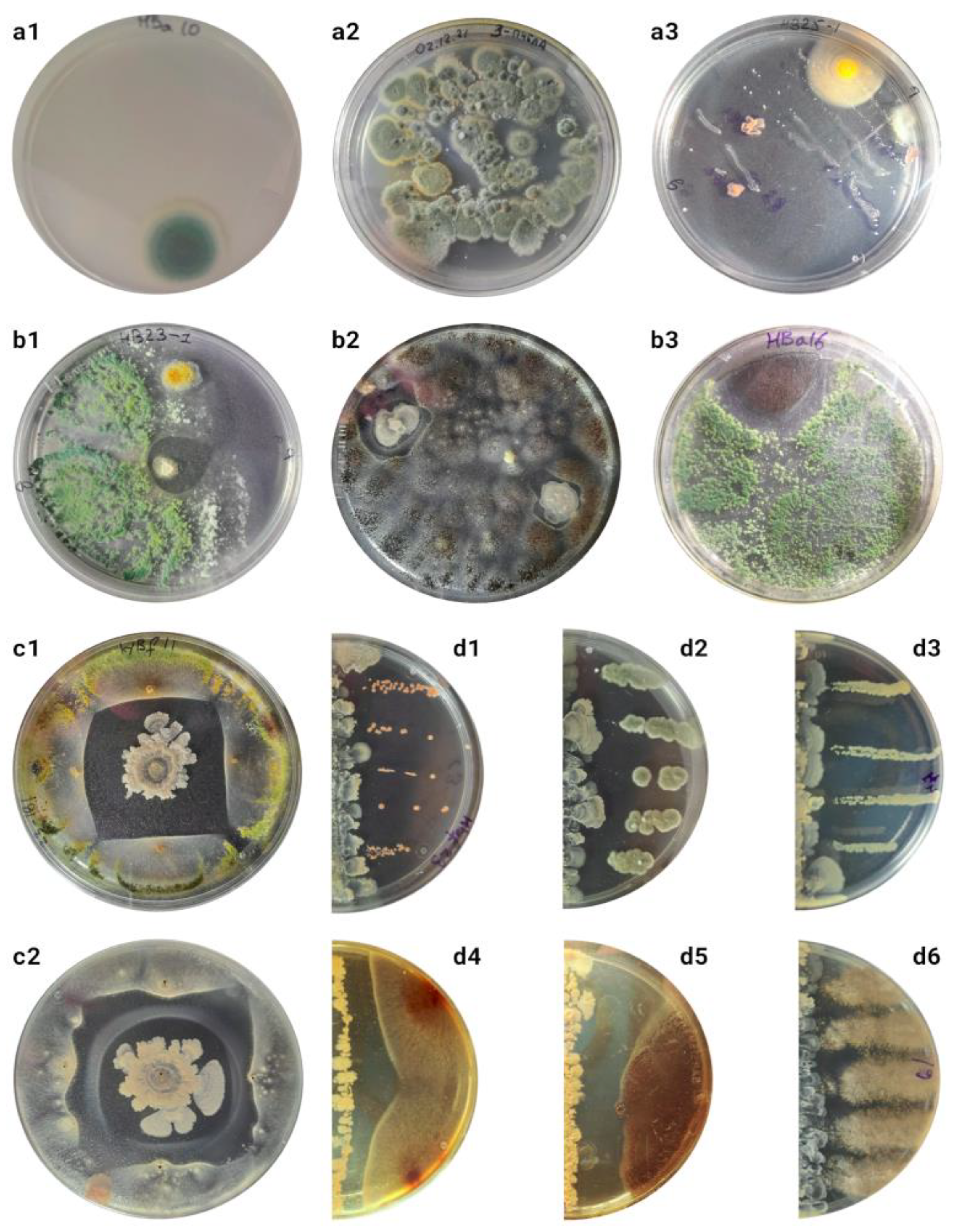

Keeping bees in sterile medium and further sowing the flushes onto solid media yields surprisingly low CFU counts (

Figure 1a1), no more than 20 in five experiments. Sowing the flushes directly onto nutrient media leads to the detection of relatively small CFU of fungi in the medium (

Figure 1a2), suppressing the activity of other microorganisms, resulting in no real cell counts in the medium. The highest biodiversity is achieved after pre-cultivation on enrichment liquid medium (

Figure S1).

To account for organisms not densely attached to the surface of bees, the microbiota obtained from the walls of the container in which the bees were transported were analyzed. Only Aspergillus and Penicillium were detected on Soburo's medium after direct bee washing; other species were cultured on Czapek's medium. The composition of organisms obtained on Czapek's, GRM and GMF media did not differ.

Seeding from abdomen, limbs and cuticular hairs was also performed to optimize the technique (

Figure S3). When using a solution with a mixture of compounds to disrupt biofilms, cultures could not be isolated (

Figure S2c). The highest diversity was obtained in cultures on solid nutrient agar after enrichment on liquid nutrient medium for 24 hours, isolating 100-5000 CFU from different bee organs (

Figure S3).

Different cultures with complex morphology, which was often not preserved during passages, as well as mixed colonies consisting of cells of different morphologies and probably from several taxa were frequently observed in the cultures (

Figure S4). In total, more than 250 colonies were obtained from the cuticle of 10 adult worker winter bees, of which 54 differed in morphological and physiological criteria (

Figure S5-13). Of these, only a small fraction (not more than 20%) are also readily isolated from the hive environment. Cultures S5c, S5d and S6d (

Aspergillus spp.) and S6a (

Penicillium sp.) dominated the cultures from dry dead bees from the same hive.

2 different cultures were obtained that inhibited the development of other microorganisms (

Figure 1b). Cultures similar to S10b were independently isolated from 4 out of 10 bees tested from 2 out of 3 different hives. Culture S10f was isolated only once from a sample in which S10b was also present.

Only the culture of the unknown Actinomycete S10b retained antimicrobial activity when transferred to other media. The highest zone of suppression was observed on Czapek medium, while on A4, Soy or Gauze II agar the activity was lost. For further studies, tests were performed after sowing with dots (

Figure 1c,

Figure S14) or lines (

Figure 1d,

Figures S14-15). Some cultures are more suppressed than others (

Figure S16). On average, activity against fungi is more strongly expressed than antibacterial activity (ANOVA p-value = 0.003), however, other obtained fungi producing antimicrobial compounds were not suppressed (

Figure 1d6). It is also possible that cultures obtained from the surface of bees are more resistant to the antimicrobial compounds produced (ANOVA p-value < 10

-4). However, more testing is needed to draw definite conclusions about this.

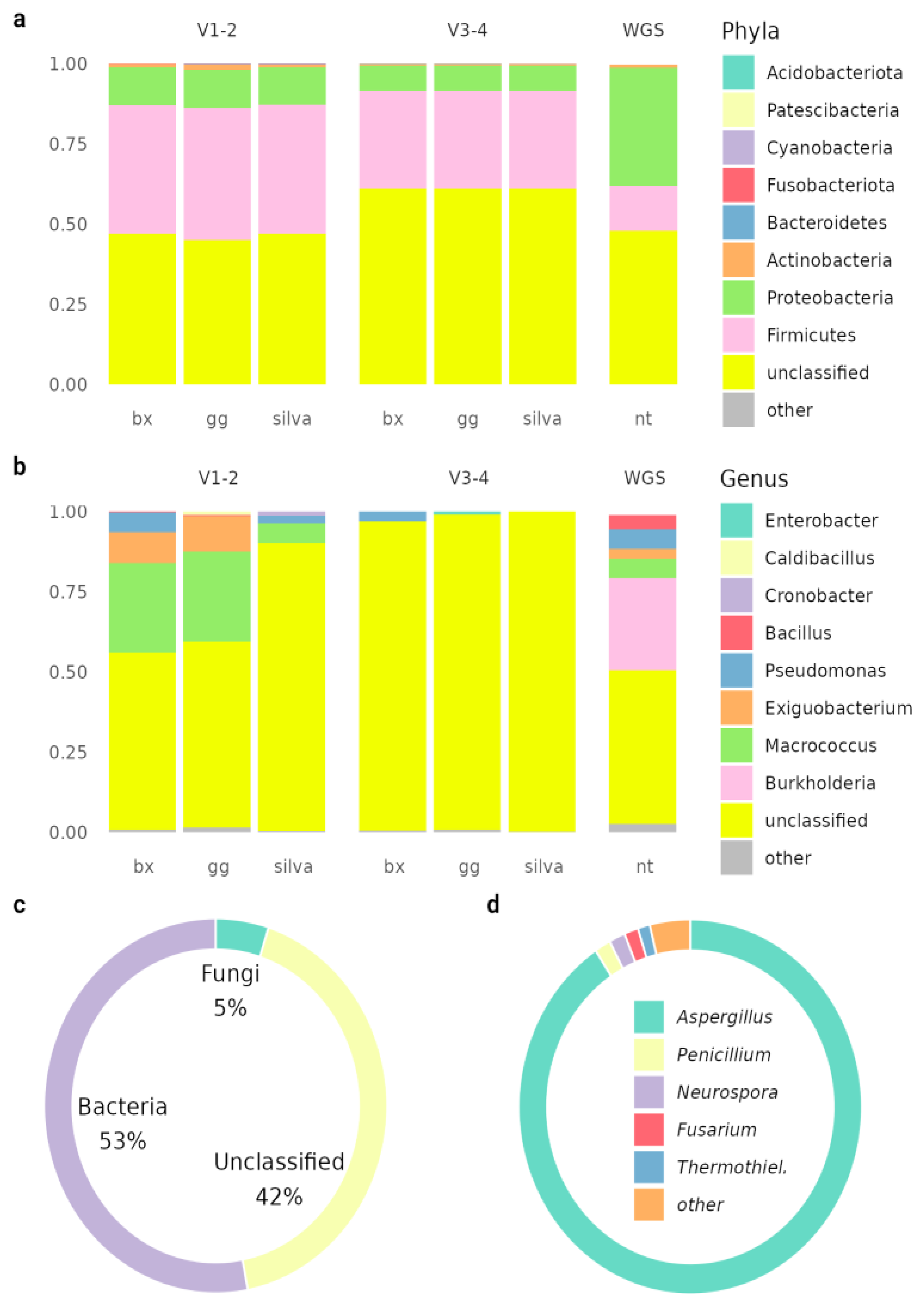

The pooled microbiota sample was analyzed by 16S and WGS sequencing methods (

Figure 2). The samples show an atypically high proportion of unclassifiable sequences for 16S sequencing, which may indicate the presence of unknown species or possible sample preparation problems. Different databases were used for annotation, all of which give similar results when used in the analysis and do not help to solve the low classification rate problem (

Figure S17).

Alpha diversity indices are similar for indices calculated from 16S sequencing data of V1-V2, V3-V4 and WGS: Shannon index 1.59±0.05, 1.41±0.18 and 1.63, Simpson index 0.70±0.01, 0.68±0.06 and 0.70. respectively. Alpha diversity is similar to that obtained in other articles (ANOVA p-value 0.13) (

Figure S18). For beta diversity, the annotation results differ from the rest of the pan-metagenome. This is due to sample preparation, especially - enrichment of the sample.

Metagenome annotation identified 23955 CDSs, of which 10588 were able to identify product function. Thirty-seven genes (26 unique) for biosynthesis of 22 different antimicrobial compounds (

Supplementary table S2) and 119 resistance genes (40 unique) were identified. Complete toxin-antitoxin systems higA/B, mqsA/R were detected.

Antimicrobial compounds possibly produced by the metagenome can vary in origin, mechanism of action, and chemical nature; they may be small molecules or antimicrobial peptides, such as bacitracin and gramicidin. Each antimicrobial compound can possess either a narrow mechanism of action or a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity.

Copper, cobalt-zinc-cadmium, and arsenic resistance cassettes were also detected. Several organic hydroperoxide resistance genes were found: ohrR (5), ohrB (3), ohrA (2). The community is characterized by a large spectrum of excreted and metabolizable secondary metabolites.

4. Discussion

The bee cuticle community grows on a relatively poor substrate. Studies with whole bee 16S sequencing in the methodology are encountered, but show little or no difference with gut sequencing [

42]. Small values are shown by qPCR analysis and culture methods [

9,

10,

43]. The bee surface microbiome is probably poor, with no more than a few thousand CFUs there. The highest biomass is probably characteristic of mold fungi (in contrast with previous research), while the maximum biodiversity is probably among bacteria and yeasts getting there from sugar-rich nectar and early honey (similar to previous studies [

9,

43]).

In the transition to opportunism or parasitism of individual members of the community, such an environment becomes richer for a short time. Community succession is complete after bee death, the final community is probably dominated by the mold fungi

Penicillium and

Aspergillus. The extent to which succession is sequential is unclear. It is also unclear what role the fungi, which are potential but not obligate pathogens [

44,

45], play in the cuticular microflora.

Metagenome annotation revealed more than 20 000 coding sequences, half of them linked to specific functions. A significant portion was associated with the biosynthesis of various antimicrobial compounds, while numerous resistance genes were also identified. Some members of the community produce antimicrobial compounds. Whole-genome sequencing also confirms the presence of genes for their biosynthesis and resistance. The key producers of antimicrobial compounds may be Burkholderiaceae, Bacilli and Actinobacteria. The detected components of toxin-antitoxin systems may also be involved as part of the community resistance maintenance system.

Fungicides and insecticides are known to affect this community [

11]. It remains unclear to what extent they will affect its bark representatives, given the diversity of resistance of organisms from the surface.

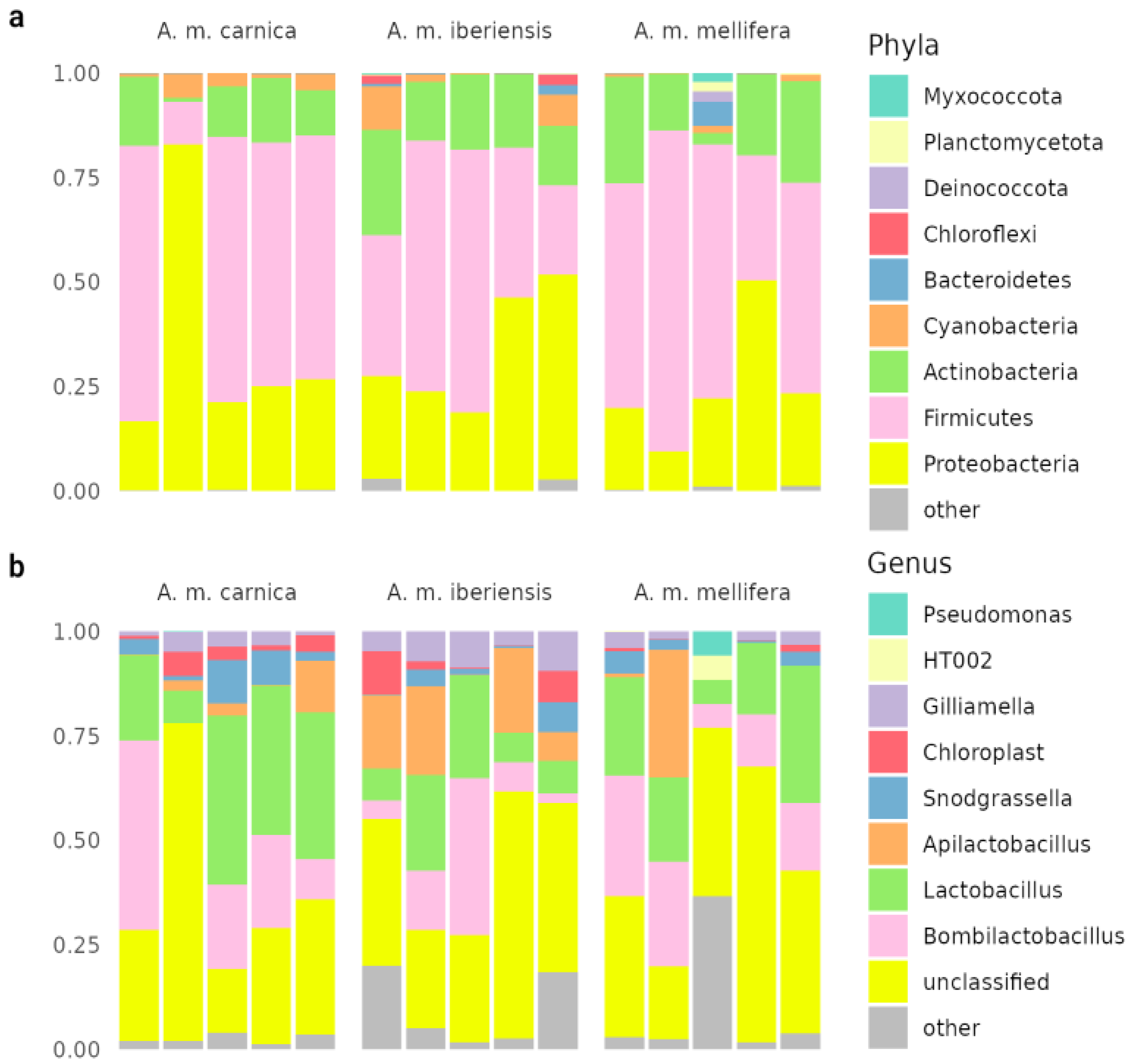

The results of the metagenomic analysis differ from the known literature data on bee microbiology [

2,

9,

31,

46,

47]. Previously, 16S sequencing of bee cuticle was performed [

9], which was reannotated in this work (

Figure 3). The community is dominated by impurities from intestinal microflora: obligately anaerobic

Lactobacillus,

Bombilactobacillus,

Snodgrassella. The share in the microbiome of aerobes characteristic of the foregut and other hive environments -

Apilactobacillus and Actinobacteria, probably represented by

Bifidobacterium asteroides - is high. In our study, after enrichment, we find a different situation, but it is difficult to say which approach better describes the real, influential bee cuticular community.

The alpha diversity indices from 16S and whole genome sequencing are comparable, consistent with all studies. However, beta diversity results varied across the pan-metagenome. Despite some similarities, there are also obvious differences with the intestinal microflora [

2,

15,

48]. Unclassifiable species are more widely represented in the cuticle community and may play an important role in it. Key isolated actinomycete cultures remain unclassifiable by both culture and metagenomic methods. Their further study in confirming their role and persistence in bee cuticle communities is very important.

5. Conclusions

Our work is one of the first studies of the bee cuticular community. Despite the application of various methods (16S sequencing, WGS, qPCR, cultural methods) the question still remains: what is the functionality of this community? What are the introduced species in it, and does it in principle have its own bark species? Our study supports the hypothesis that this community is independent, but unequivocal confirmation may come from analysis of the surface microflora by FISH or SEM. Metagenomic analyses and qPCR are hampered by significant contamination of the bee surface by representatives of their gut microbiome, which are obligate anaerobes. There is probably a higher proportion of actinomycetes and unclassifiable organisms in the community than in the bee gut. Their source may be the honeycomb of the hive, but the opposite situation may also be true, and finally different actinomycetes and unclassifiable organisms may be present on the surface of the hive and bees. This question requires further research.

Our results open a new chapter in micro”bee”ology. Currently, there are no fully unstudied hive environments from a metagenomic perspective. The beehive, functioning as a superorganism, incorporates the genomes of its associated organisms into a unified hologenome, collectively responding to external stimuli.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

L.A. and S.D. formed the idea of this study. S.D. conducted all experiments, prepared samples for sequencing; S.D, G.K and A.T. analyzed data, collected and structured information; L.A. and S.D. supervised the preparation of the draft. Authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of state support for the creation and development of World-Class Research Centers ‘Digital Biodesign and Personalized Healthcare’ (No 075-15-2022-305).

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the students of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of the Ecological and Biological Center “Krestovskiy Ostrov” for their maintenance in cultures photography and to the subscribers of “some biochemistry memes” for the likes under the posts with endless photos of cultures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Douglas, A. E. Multiorganismal Insects: Diversity and Function of Resident Microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smutin, D.; Lebedev, E.; Selitskiy, M.; Panyushev, N.; Adonin, L. Micro”bee”ota: Honey Bee Normal Microbiota as a Part of Superorganism. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Webster, P.; Finkel, S. E.; Tower, J. Increased Internal and External Bacterial Load during Drosophila Aging without Life-Span Trade-Off. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, G.; Segal, D.; Ringo, J. M.; Hefetz, A.; Zilber-Rosenberg, I.; Rosenberg, E. Commensal Bacteria Play a Role in Mating Preference of Drosophila Melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 20051–20056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokeev, V.; Flaven-Pouchon, J.; Wang, Y.; Gehring, N.; Moussian, B. Ratio between Lactobacillus Plantarum and Acetobacter Pomorum on the Surface of Drosophila Melanogaster Adult Flies Depends on Cuticle Melanisation. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, O. B.; Kothamasu, K. S.; Ziemba, M. J.; Benner, M.; Cristinziano, M.; Kantz, S.; Leger, D.; Li, J.; Patel, D.; Rabuse, W.; Sutton, S.; Wilson, A.; Baireddy, P.; Kamat, A. A.; Callas, M. J.; Borges, M. J.; Scalia, M. N.; Klenk, E.; Scherer, G.; Martinez, M. M.; Grubb, S. R.; Kaufmann, N.; Pruitt, J. N.; Keiser, C. N. Exposure to Cuticular Bacteria Can Alter Host Behavior in a Funnel-Weaving Spider. Curr. Zool. 2018, 64, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birer, C.; Tysklind, N.; Zinger, L.; Duplais, C. Comparative Analysis of DNA Extraction Methods to Study the Body Surface Microbiota of Insects: A Case Study with Ant Cuticular Bacteria. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, e34–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birer, C.; Moreau, C. S.; Tysklind, N.; Zinger, L.; Duplais, C. Disentangling the Assembly Mechanisms of Ant Cuticular Bacterial Communities of Two Amazonian Ant Species Sharing a Common Arboreal Nest. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamm, M.; Reiß, F.; Sohl, L.; Gabel, M.; Noll, M.; Scheiner, R. Solitary Bees Host More Bacteria and Fungi on Their Cuticle than Social Bees. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, G. T.; Melo, W. G. da P.; Castro, I. de; Menezes, C.; Paludo, C. R.; Rosa, C. A.; Pupo, M. T. Further Evidences of an Emerging Stingless Bee-Yeast Symbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiß, F.; Schuhmann, A.; Sohl, L.; Thamm, M.; Scheiner, R.; Noll, M. Fungicides and Insecticides Can Alter the Microbial Community on the Cuticle of Honey Bees. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janke, R. S.; Kaftan, F.; Niehs, S. P.; Scherlach, K.; Rodrigues, A.; Svatoš, A.; Hertweck, C.; Kaltenpoth, M.; Flórez, L. V. Bacterial Ectosymbionts in Cuticular Organs Chemically Protect a Beetle during Molting Stages. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2691–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, T.; Barnett, M. W.; Laetsch, D. R.; Bush, S. J.; Wragg, D.; Budge, G. E.; Highet, F.; Dainat, B.; de Miranda, J. R.; Watson, M.; Blaxter, M.; Freeman, T. C. Characterisation of the British Honey Bee Metagenome. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Jützeler, M.; França, S. C.; Wäckers, F.; Andreasson, E.; Stenberg, J. A. Bee-Vectored Aureobasidium Pullulans for Biological Control of Gray Mold in Strawberry. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W.; Moran, N. Gut Microbial Communities of Social Bees. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Martinson, V. G.; Moran, N. A. Functional Diversity within the Simple Gut Microbiota of the Honey Bee. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 11002–11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Jützeler, M.; França, S. C.; Wäckers, F.; Andreasson, E.; Stenberg, J. A. Bee-Vectored Aureobasidium Pullulans for Biological Control of Gray Mold in Strawberry. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda-Mejia, M. P.; Nägeli, L.; Lutz, S.; Hayes, R. D.; Varadarajan, A. R.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Ahrens, C. H.; Freimoser, F. M. Genome, Transcriptome and Secretome Analyses of the Antagonistic, Yeast-like Fungus Aureobasidium Pullulans to Identify Potential Biocontrol Genes. Microb. Cell Graz Austria 2021, 8, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J. R.; Dillon, M. R.; Bokulich, N. A.; Abnet, C. C.; Al-Ghalith, G. A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E. J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J. E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C. J.; Brown, C. T.; Callahan, B. J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A. M.; Chase, J.; Cope, E. K.; Da Silva, R.; Diener, C.; Dorrestein, P. C.; Douglas, G. M.; Durall, D. M.; Duvallet, C.; Edwardson, C. F.; Ernst, M.; Estaki, M.; Fouquier, J.; Gauglitz, J. M.; Gibbons, S. M.; Gibson, D. L.; Gonzalez, A.; Gorlick, K.; Guo, J.; Hillmann, B.; Holmes, S.; Holste, H.; Huttenhower, C.; Huttley, G. A.; Janssen, S.; Jarmusch, A. K.; Jiang, L.; Kaehler, B. D.; Kang, K. B.; Keefe, C. R.; Keim, P.; Kelley, S. T.; Knights, D.; Koester, I.; Kosciolek, T.; Kreps, J.; Langille, M. G. I.; Lee, J.; Ley, R.; Liu, Y.-X.; Loftfield, E.; Lozupone, C.; Maher, M.; Marotz, C.; Martin, B. D.; McDonald, D.; McIver, L. J.; Melnik, A. V.; Metcalf, J. L.; Morgan, S. C.; Morton, J. T.; Naimey, A. T.; Navas-Molina, J. A.; Nothias, L. F.; Orchanian, S. B.; Pearson, T.; Peoples, S. L.; Petras, D.; Preuss, M. L.; Pruesse, E.; Rasmussen, L. B.; Rivers, A.; Robeson, M. S.; Rosenthal, P.; Segata, N.; Shaffer, M.; Shiffer, A.; Sinha, R.; Song, S. J.; Spear, J. R.; Swafford, A. D.; Thompson, L. R.; Torres, P. J.; Trinh, P.; Tripathi, A.; Turnbaugh, P. J.; Ul-Hasan, S.; Van Der Hooft, J. J. J.; Vargas, F.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Vogtmann, E.; Von Hippel, M.; Walters, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, M.; Warren, J.; Weber, K. C.; Williamson, C. H. D.; Willis, A. D.; Xu, Z. Z.; Zaneveld, J. R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J. G. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B. J.; McMurdie, P. J.; Rosen, M. J.; Han, A. W.; Johnson, A. J. A.; Holmes, S. P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F. O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J. T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D. H.; Karst, S. M.; Albertsen, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; DeSantis, T.; Song, S. J.; Bartko, A.; Havulinna, A. S.; Jousilahti, P.; Cheng, S.; Inouye, M.; Niiranen, T.; Jain, M.; Salomaa, V.; Lahti, L.; Mirarab, S.; Knight, R. Greengenes2 Unifies Microbial Data in a Single Reference Tree. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daisley, B. A.; Reid, G. BEExact: A Metataxonomic Database Tool for High-Resolution Inference of Bee-Associated Microbial Communities. mSystems 2021, 6, e00082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H. A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, G. M.; Maffei, V. J.; Zaneveld, J. R.; Yurgel, S. N.; Brown, J. R.; Taylor, C. M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M. G. I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D. E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F. P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: Estimating Species Abundance in Metagenomics Data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.; Ng, K. L.; Krogh, A. Fast and Sensitive Taxonomic Classification for Metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smutin, D.; Taldaev, A.; Lebedev, E.; Adonin, L. Shotgun Metagenomics Reveals Minor Micro“Bee”Omes Diversity Defining Differences between Larvae and Pupae Brood Combs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: A New Versatile Metagenomic Assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Leung, H. C. M.; Yiu, S. M.; Chin, F. Y. L. IDBA-UD: A de Novo Assembler for Single-Cell and Metagenomic Sequencing Data with Highly Uneven Depth. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2012, 28, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheenko, A.; Saveliev, V.; Gurevich, A. MetaQUAST: Evaluation of Metagenome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L. D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; Kuhn, M.; Pedersen, T. L.; Miller, E.; Bache, S. M.; Müller, K.; Ooms, J.; Robinson, D.; Seidel, D. P.; Spinu, V.; Takahashi, K.; Vaughan, D.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G. L.; Blanchet, F. G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P. R.; O’Hara, R. B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M. H. H.; Szoecs, E.; Wagner, H.; Barbour, M.; Bedward, M.; Bolker, B.; Borcard, D.; Carvalho, G.; Chirico, M.; Caceres, M. D.; Durand, S.; Evangelista, H. B. A.; FitzJohn, R.; Friendly, M.; Furneaux, B.; Hannigan, G.; Hill, M. O.; Lahti, L.; McGlinn, D.; Ouellette, M.-H.; Cunha, E. R.; Smith, T.; Stier, A.; Braak, C. J. F. T.; Weedon, J. Vegan: Community Ecology Package; 2024.

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: An Environment for Modern Phylogenetics and Evolutionary Analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smutin, D. aRchiteutis: Tool for Visualize & Work with Kraken2 Reports, 2023. Available online: https://github.com/dsmutin/aRchiteutis (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Ribière, C.; Hegarty, C.; Stephenson, H.; Whelan, P.; O’Toole, P. W. Gut and Whole-Body Microbiota of the Honey Bee Separate Thriving and Non-Thriving Hives. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 78, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malassigné, S.; Minard, G.; Vallon, L.; Martin, E.; Valiente Moro, C.; Luis, P. Diversity and Functions of Yeast Communities Associated with Insects. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, K.; Fazio, G.; Jensen, A. B.; Hughes, W. O. H. The Distribution of Aspergillus Spp. Opportunistic Parasites in Hives and Their Pathogenicity to Honey Bees. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 169, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becchimanzi, A.; Nicoletti, R. Aspergillus-Bees: A Dynamic Symbiotic Association. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 968963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K. E.; Sheehan, T. H.; Mott, B. M.; Maes, P.; Snyder, L.; Schwan, M. R.; Walton, A.; Jones, B. M.; Corby-Harris, V. Microbial Ecology of the Hive and Pollination Landscape: Bacterial Associates from Floral Nectar, the Alimentary Tract and Stored Food of Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera). PloS One 2013, 8, e83125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, R. S.; Huang, Q.; Evans, J. D. Hologenome Theory and the Honey Bee Pathosphere. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, E. V. S.; Moran, N. A. The Honeybee Microbiota and Its Impact on Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).