Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

2.2. Experimental Setups Using Honey Bee Colonies

2.2.1. Preparatory Work for the #

2.2.2. Description of the Selected Apiary for Tests

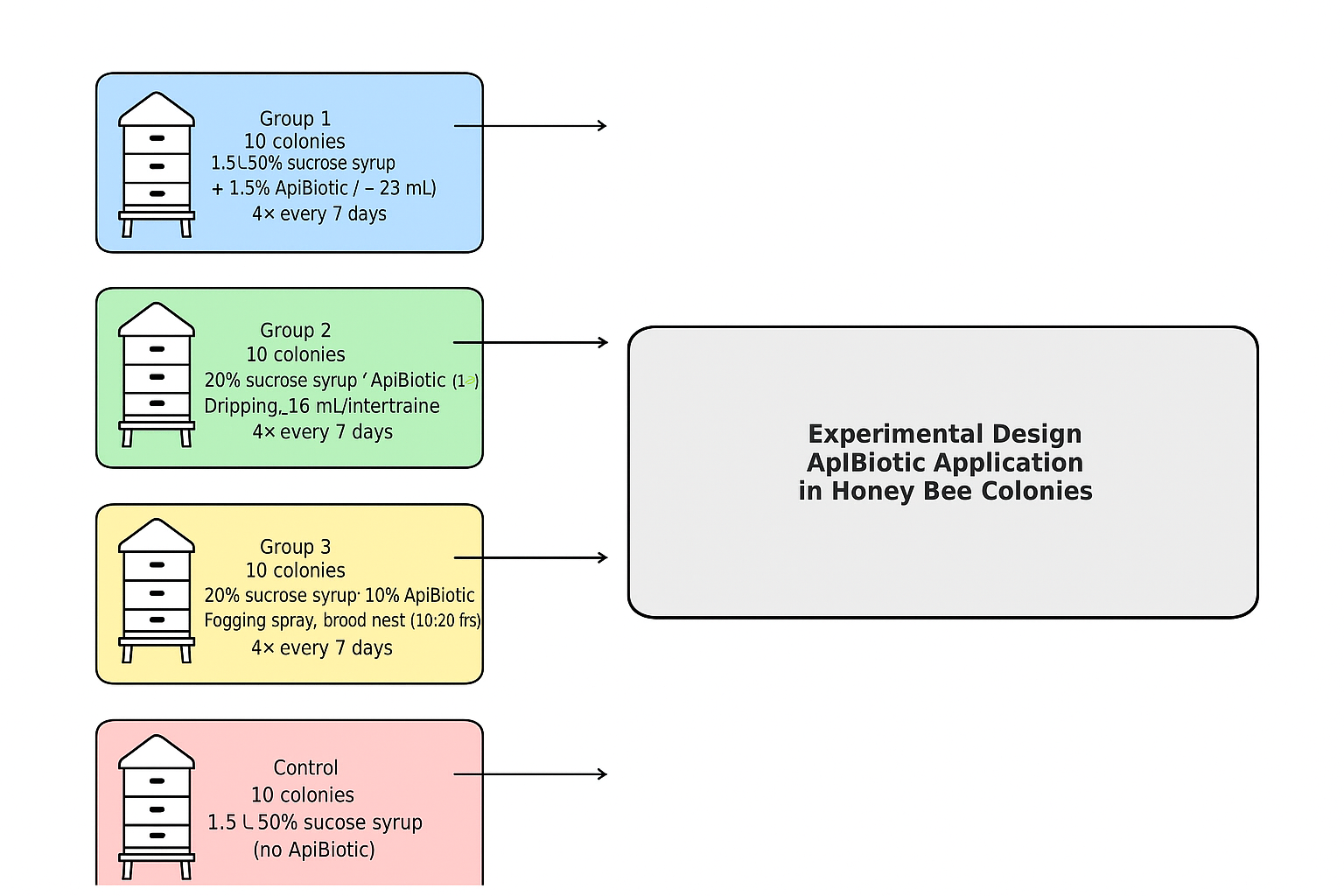

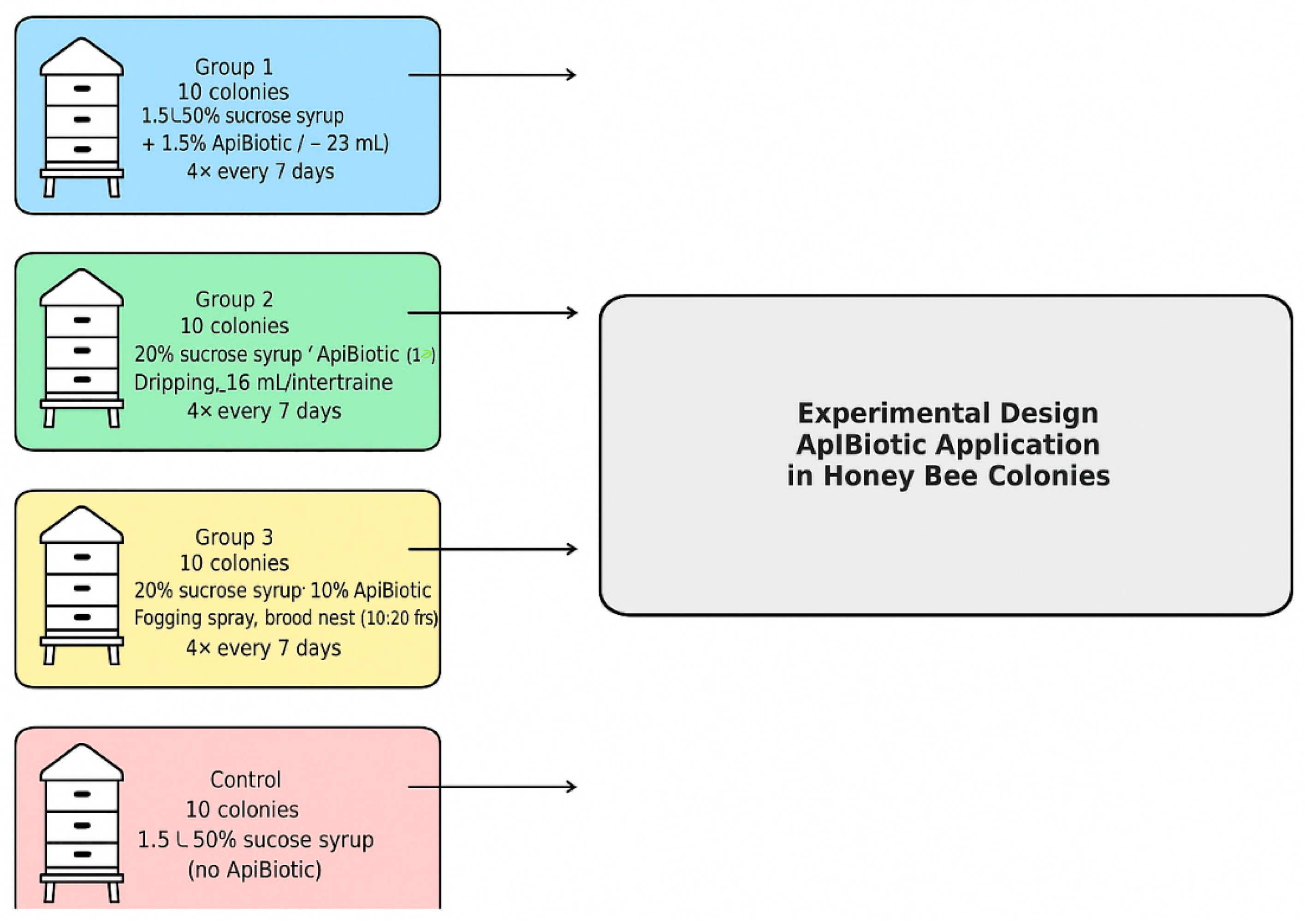

2.2.3. Experimental Setup

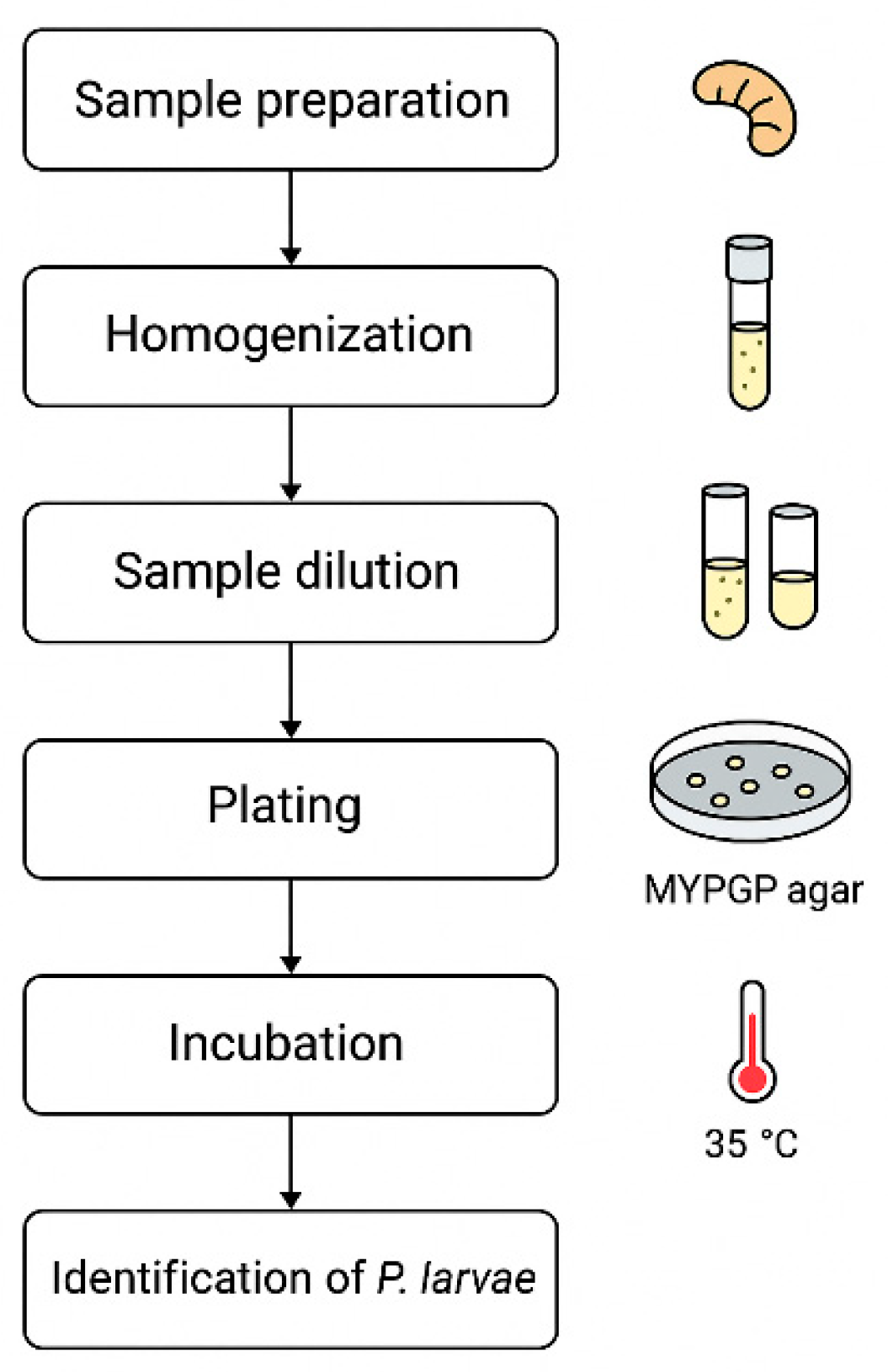

2.3. Working Methodology: Brood Samples Microbiological Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Number of Bee Colonies Released from Microbiological Risk and P. larvae Pressure After the Application of ApiBiotic

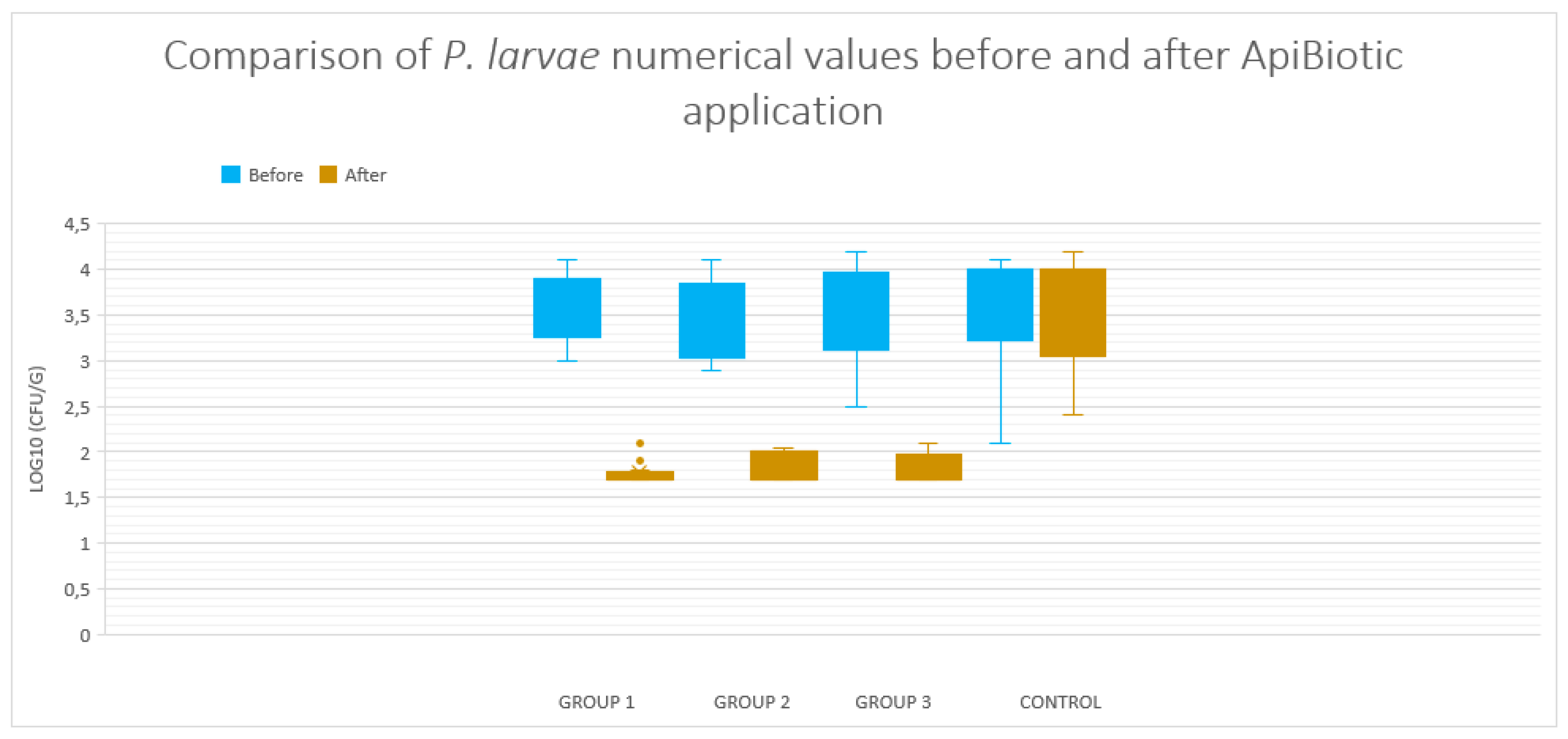

3.2. Changes in P. larvae Abundance in Groups 1-4 Without Subsequent Suspicion of American Foulbrood Infection

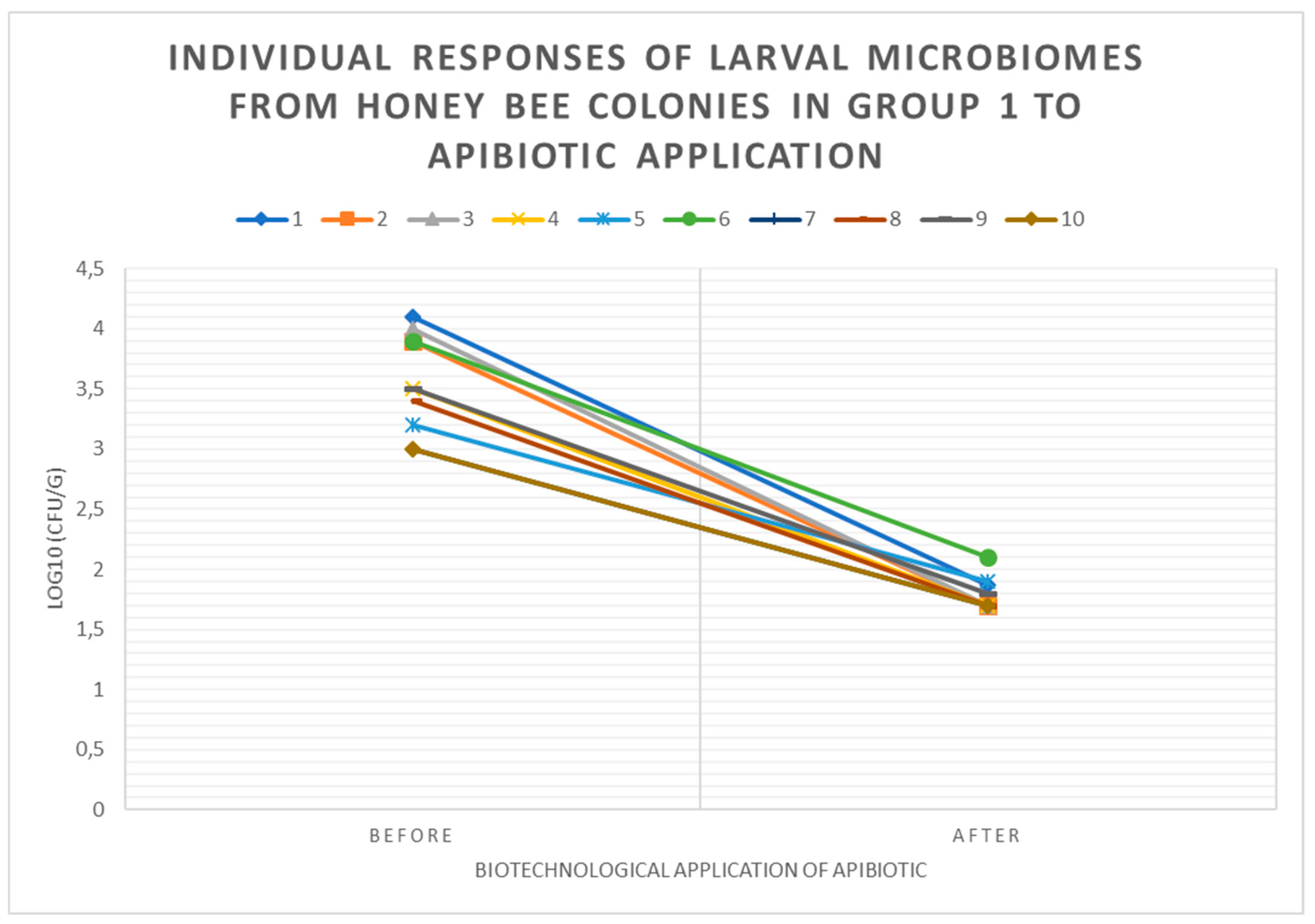

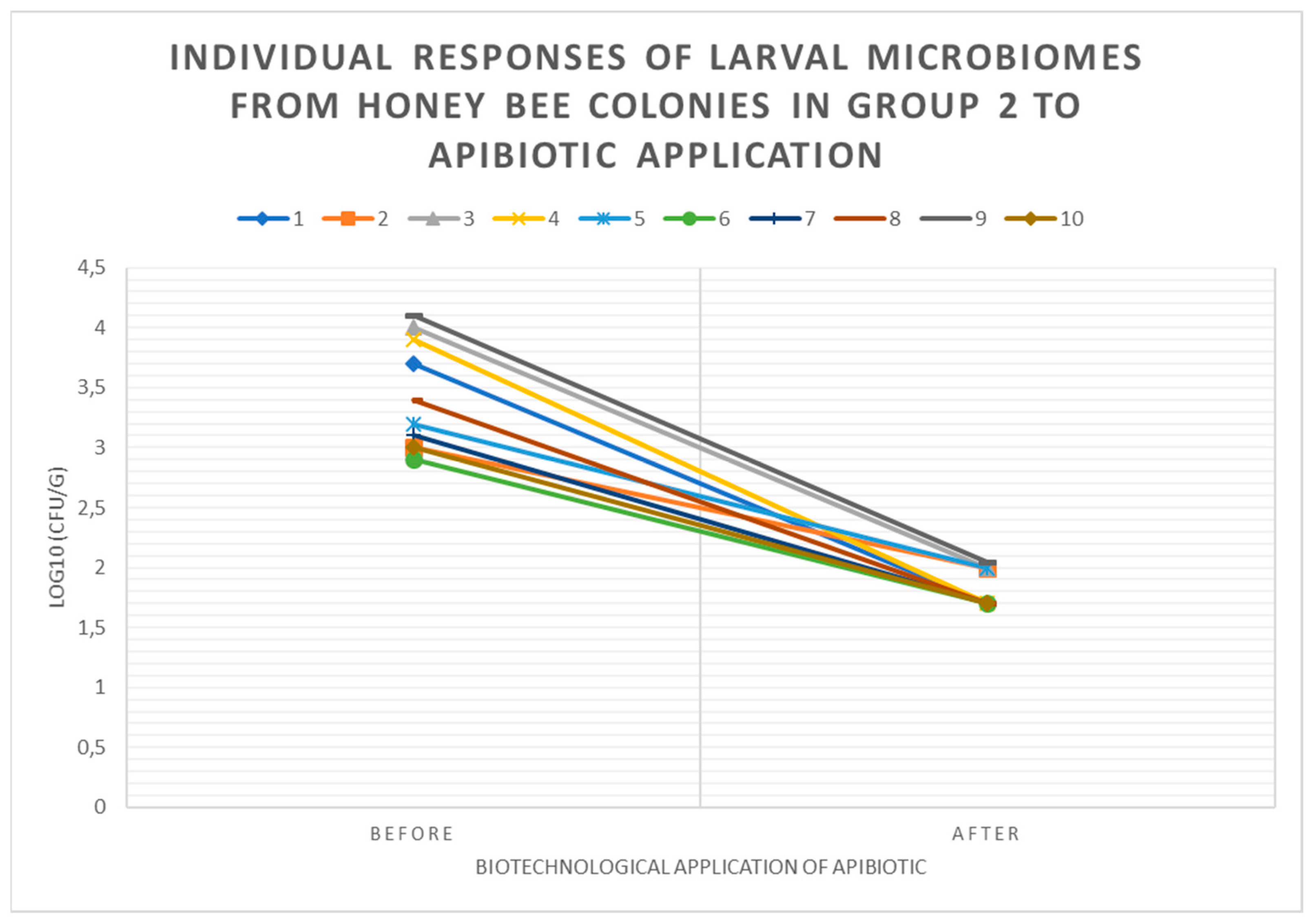

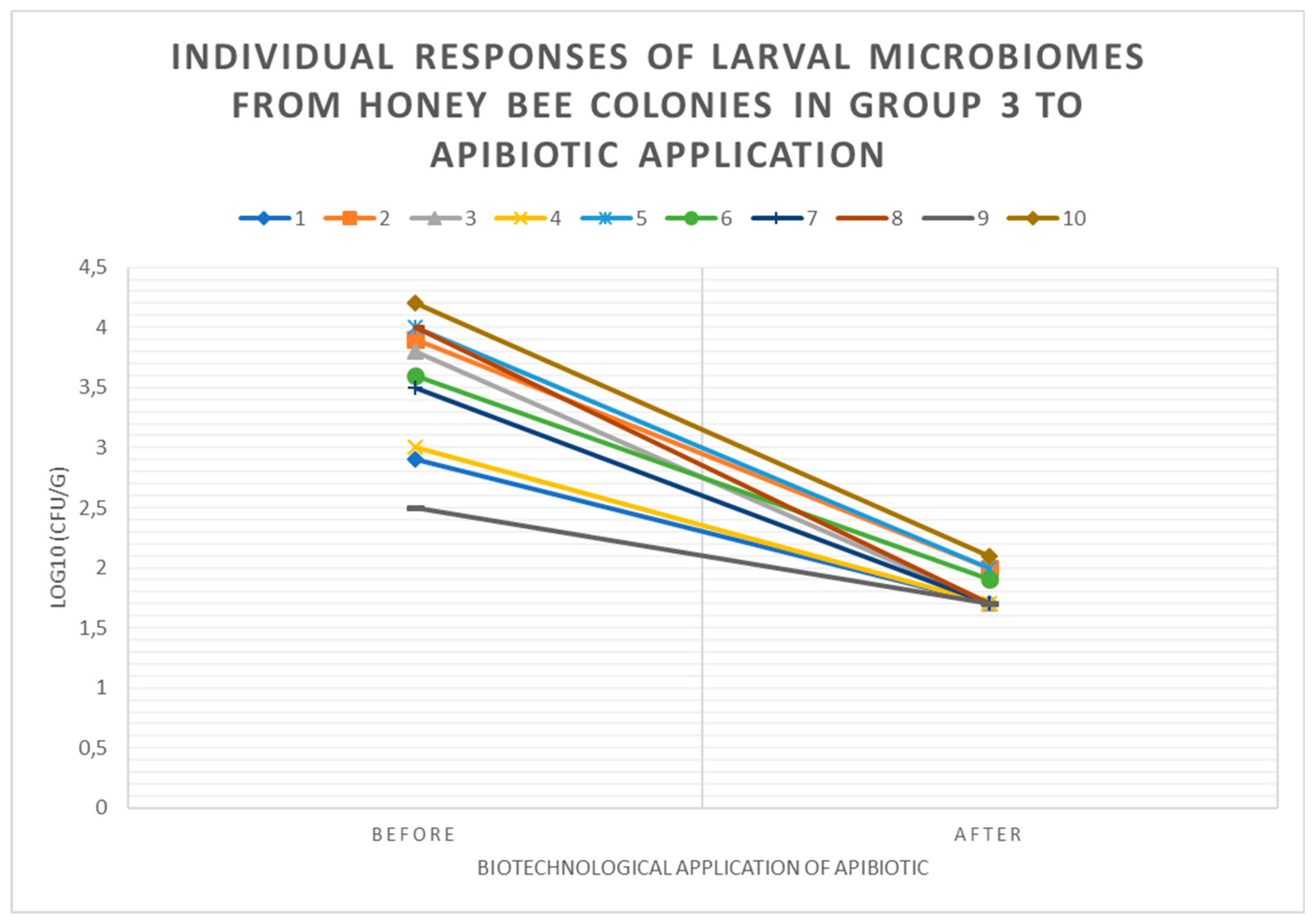

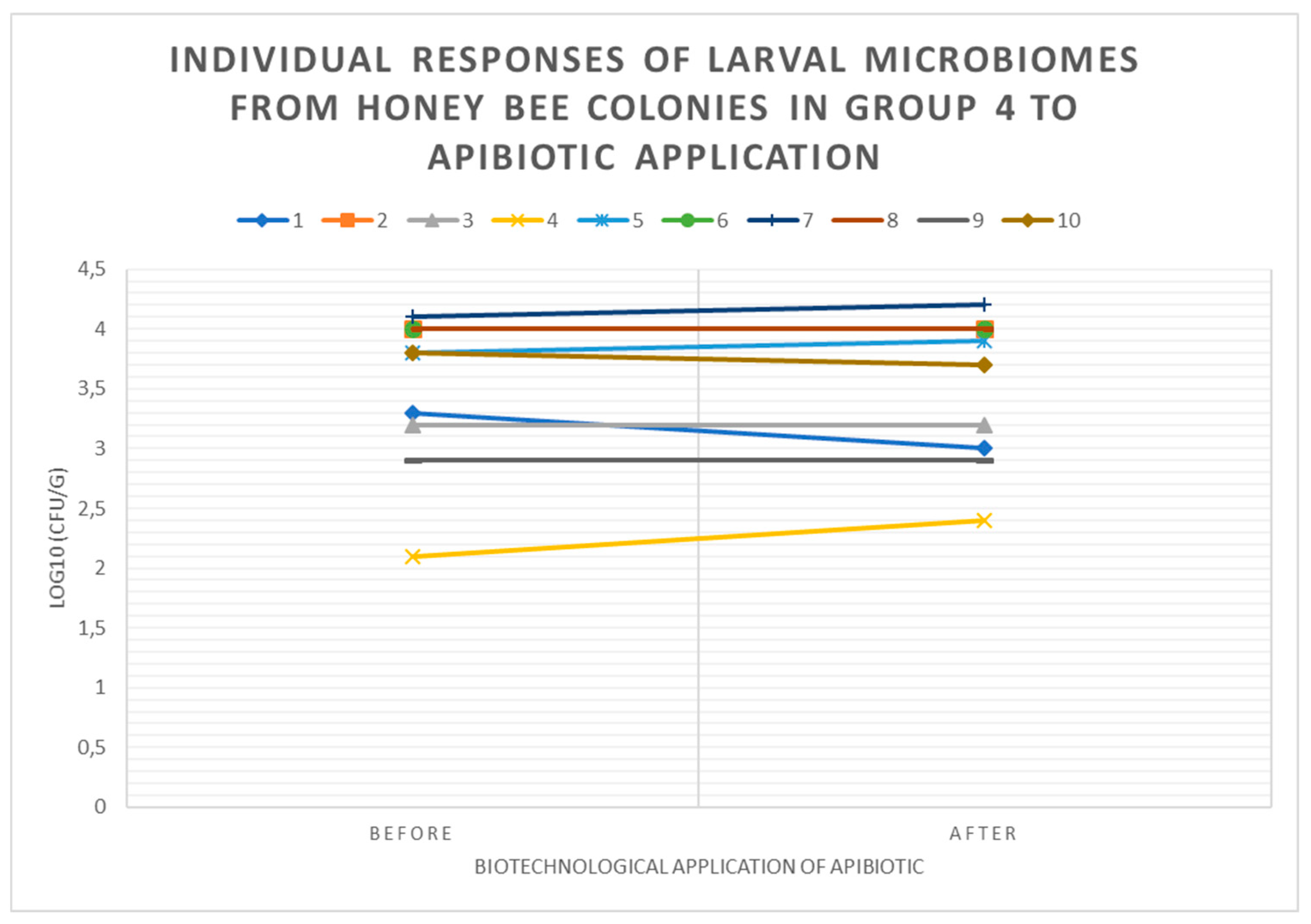

3.3. Individual Responses of Microbiomes of Brood with Changes in log10(CFU) of P. larvae in Honey Bee Colonies Before and After ApiBiotic Application in 1-4 Groups

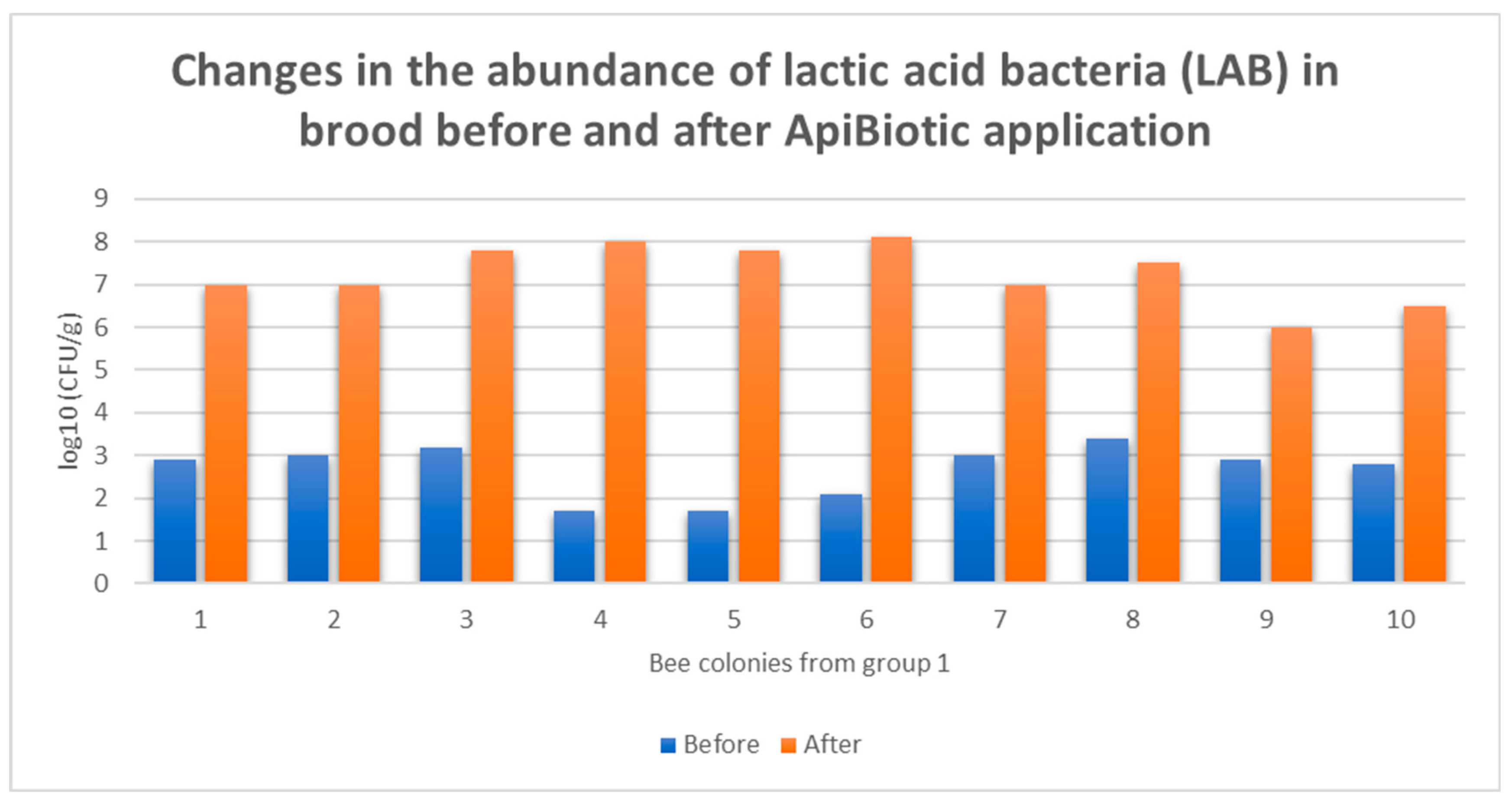

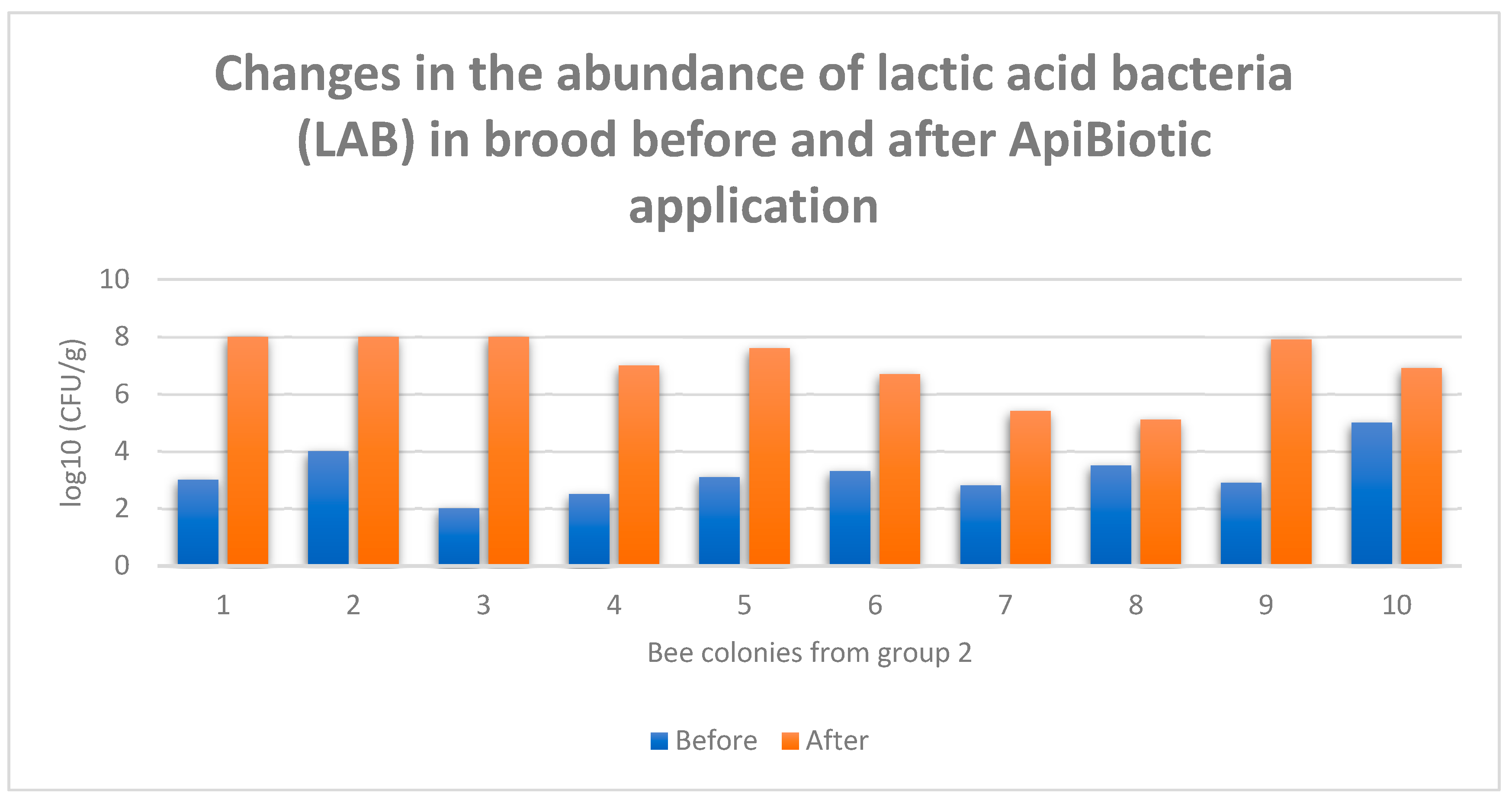

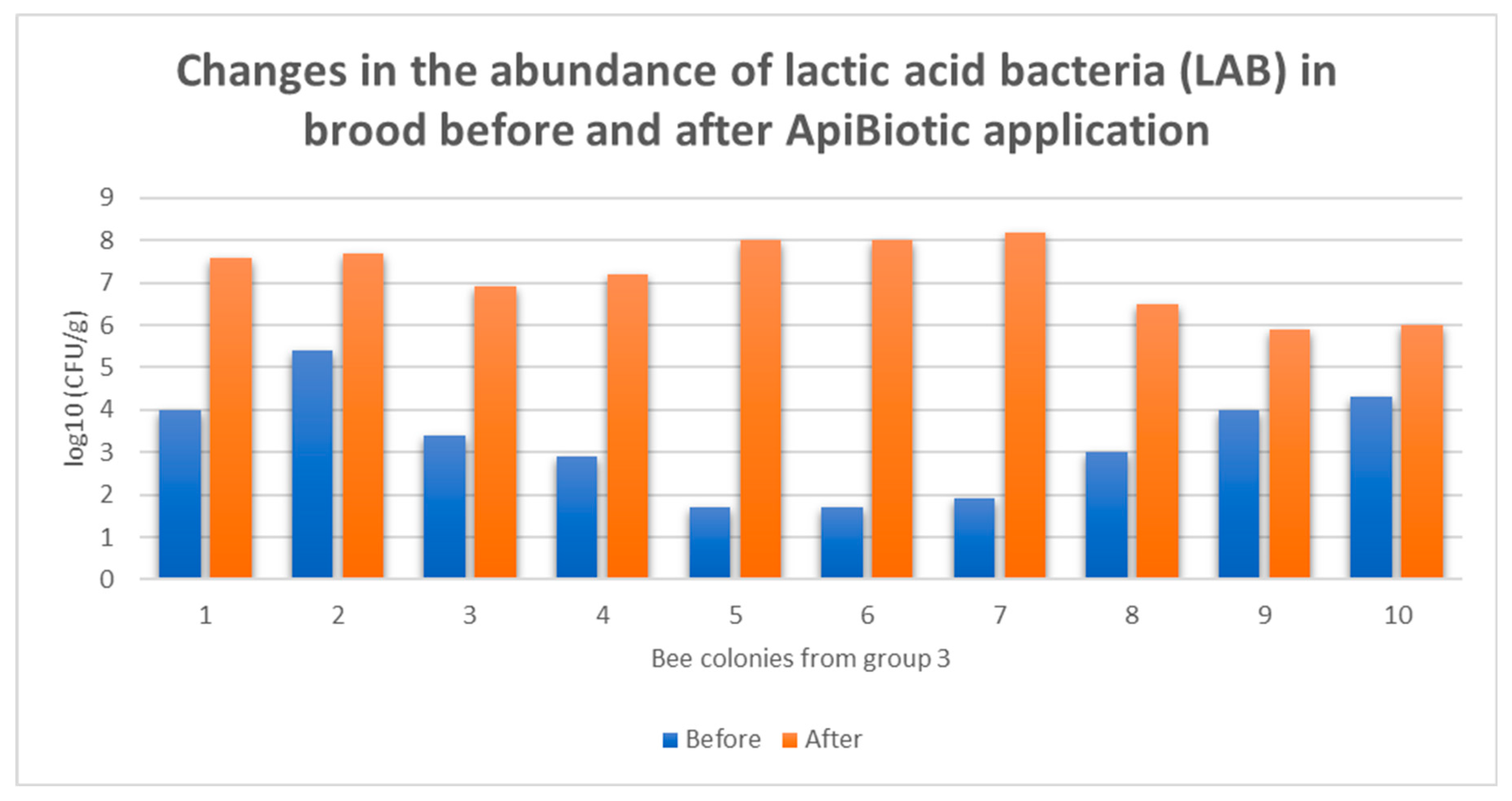

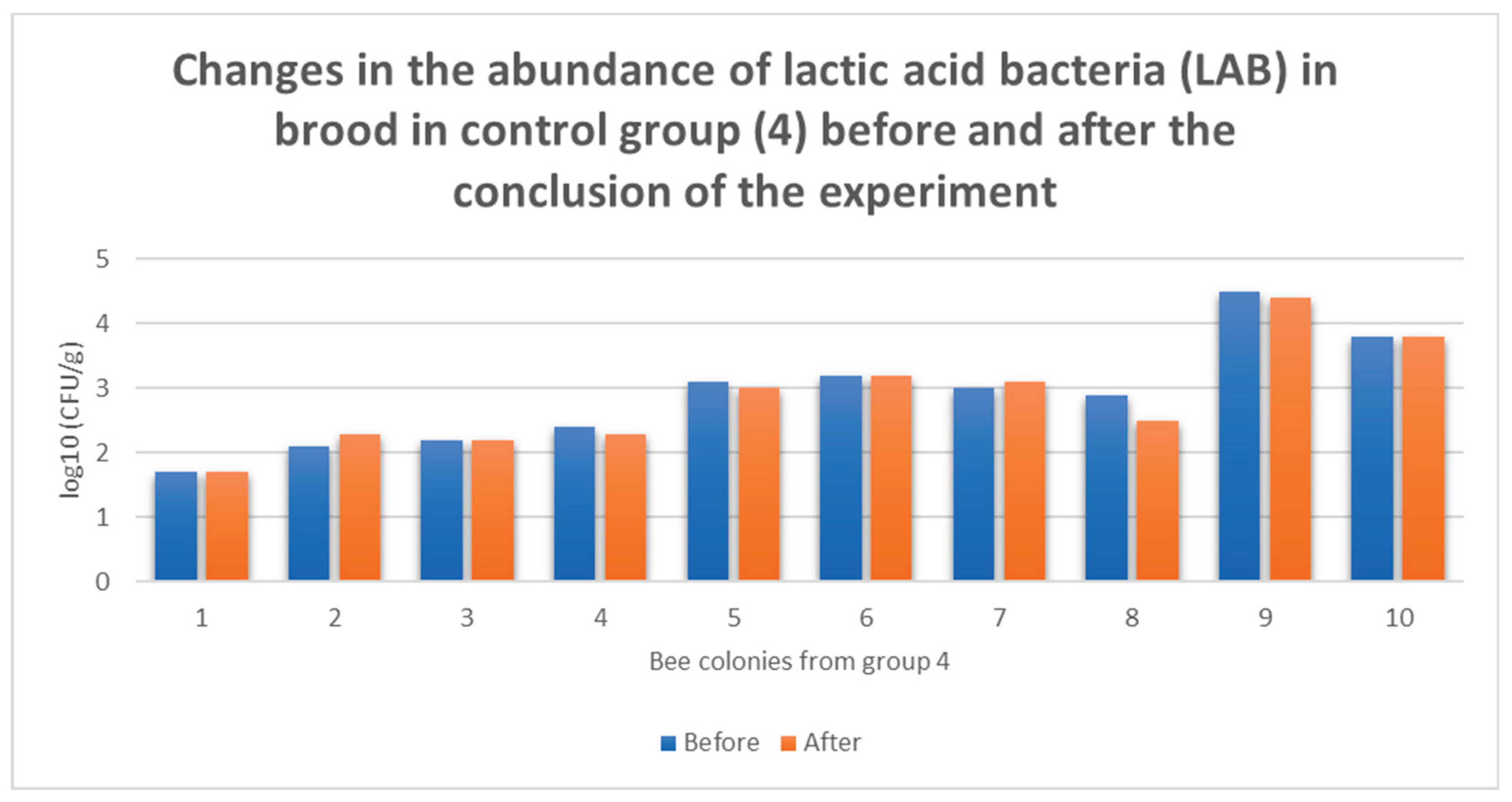

3.4. Individual Responses of Microbiomes Brood: Changes in log10(CFU) of LAB in Honey Bee Colonies Before and After ApiBiotic Application

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFB | American Foulbrood |

| OTC | Oxytetracycline hydrochloride |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| MRL | Maximum Residue Limit |

| EU | European Union |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MBC | Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| CT-46 | Line of bees belonging to Apis mellifera carnica |

| EBM | Evidence-Based Medicine |

| EBP | Evidence-Based Practice |

| EMBgt | Evidence-Based Management |

References

- Rosa Fuselli, S.; Gimenez Martinez, P.; Fuentes, G.; María Alonso-Salces, R.; Maggi, M. Prevention and Control of American Foulbrood in South America with Essential Oils: Review. In Beekeeping - New Challenges; Eduardo Rebolledo Ranz, R., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2020; ISBN 9781838804671 9781838804763.

- Mosca, M.; Gyorffy, A.; Milito, M.; Di Ruggiero, C.; De Carolis, A.; Pietropaoli, M.; Giannetti, L.; Necci, F.; Marini, F.; Smedile, D.; et al. Antibiotic Use in Beekeeping: Implications for Health and Environment from a One-Health Perspective. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.K.; Ngugi, H.K.; Biddinger, D.J. Bee Vectoring: Development of the Japanese Orchard Bee as a Targeted Delivery System of Biological Control Agents for Fire Blight Management. Pathogens 2020, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognesi, M.; Zuniga, A.I.; Cordova, L.G.; Mallinger, R.; Peres, N.A. Bee Vectoring Technology Using Clonostachys Rosea as a Biological Control for Botrytis Fruit Rot of Strawberry in Florida. Plant Health Progress 2024, 25, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griescom, D.C. Bee Vectoring Technologies: A Revolutionary Approach to Sustainable Crop Protection. Advances in Crop Science and Technology 2025, 13, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, E. American Foulbrood and the Risk in the Use of Antibiotics as a Treatment. In Modern Beekeeping - Bases for Sustainable Production; Eduardo Rebolledo Ranz, R., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2020. ISBN 9781838801557 9781838801564.

- Bulson, L.; Becher, M.A.; McKinley, T.J.; Wilfert, L. Long-term Effects of Antibiotic Treatments on Honeybee Colony Fitness: A Modelling Approach. J Appl Ecol 2021, 58, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, M.; Antúnez, K.; Invernizzi, C.; Aldea, P.; Vargas, M.; Negri, P.; Brasesco, C.; De Jong, D.; Message, D.; Teixeira, E.W.; et al. Honeybee Health in South America. Apidologie 2016, 47, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, F.; Thebeau, J.M.; Cloet, A.; Kozii, I.V.; Zabrodski, M.W.; Biganski, S.; Liang, J.; Marta Guarna, M.; Simko, E.; Ruzzini, A.; et al. Evaluating Approved and Alternative Treatments against an Oxytetracycline-Resistant Bacterium Responsible for European Foulbrood Disease in Honey Bees. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority Report for 2019 on the Results from the Monitoring of Veterinary Medicinal Product Residues and Other Substances in Live Animals and Animal Products. EFS3 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Kędzierska-Matysek, M.; Teter, A.; Skałecki, P.; Topyła, B.; Domaradzki, P.; Poleszak, E.; Florek, M. Residues of Pesticides and Heavy Metals in Polish Varietal Honey. Foods 2022, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, F.; Taha, E.-K.A. Contaminants in Honey: An Analysis of EU RASFF Notifications from 2002 to 2022. J Consum Prot Food Saf 2023, 18, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee Research Institute Dol. Hygiene in the Apiary: A Manual for Hygienic Beekeeping; BeeShop Project, 6th Framework Programme of the EU: Dol, Czech Republic, 2006. Bee Research Institute Dol. Hygiene in the Apiary: A Manual for Hygienic Beekeeping; BeeShop Project, 6th Framework Programme of the EU: Dol, Czech Republic, 2006.

- Vandegrift, R.; Bateman, A.C.; Siemens, K.N.; Nguyen, M.; Wilson, H.E.; Green, J.L.; Van Den Wymelenberg, K.G.; Hickey, R.J. Cleanliness in Context: Reconciling Hygiene with a Modern Microbial Perspective. Microbiome 2017, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Sevillano-Rivera, M.C.; Calus, S.T.; Bautista-de los Santos, Q.M.; Eren, A.M.; van der Wielen, P.W.J.J.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Pinto, A.J. Disinfection Exhibits Systematic Impacts on the Drinking Water Microbiome. Microbiome 2020, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäklin, T.; Thorpe, H.A.; Pöntinen, A.K.; Gladstone, R.A.; Shao, Y.; Pesonen, M.; McNally, A.; Johnsen, P.J.; Samuelsen, Ø.; Lawley, T.D.; et al. Strong Pathogen Competition in Neonatal Gut Colonisation. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelfel, S.; Silva, M.S.; Stecher, B. Intestinal Colonization Resistance in the Context of Environmental, Host, and Microbial Determinants. Cell Host & Microbe 2024, 32, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-B.; Wang, Y.-F.; Meng, S.-Y.; Zhang, X.-T.; Wang, Y.-R.; Liu, Z.-Y. Effects of Antibiotic and Disinfectant Exposure on the Mouse Gut Microbiome and Immune Function. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e00611–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.; Teutloff, E.; Unger, K.; Lehenberger, P.; Agler, M.T. Deterministic Colonization Arises Early during the Transition of Soil Bacteria to the Phyllosphere and Is Shaped by Plant–Microbe Interactions. Microbiome 2025, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grießhammer, A.; de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Müller, P.; Gekeler, C.; Homolak, J.; Chang, H.; Schmitt, K.; Planker, C.; Schmidtchen, V.; Gallage, S.; et al. Non-Antibiotics Disrupt Colonization Resistance against Enteropathogens. Nature 2025, 644, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISSUU Controlling American Foulbrood without Antibiotics. Available online: https://issuu.com/beesfd/docs/91_bfdj_jun2009/s/14114781 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Hristov, Y.V.; Allsopp, M.H.; Wossler, T.C. Investigating Hygienic Behaviour and AFB Resistance of Apis Mellifera Capensis Colonies: Are Cape Honey Bees Hygienic and How Well Do They Cope with the Disease? Apidologie 2025, 56, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickel, F.; Bos, N.M.P.; Hughes, H.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M.; Kleiser, A.; Freitak, D. The Oral Vaccination with Paenibacillus Larvae Bacterin Can Decrease Susceptibility to American Foulbrood Infection in Honey Bees—A Safety and Efficacy Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callens, B.; Persoons, D.; Maes, D.; Laanen, M.; Postma, M.; Boyen, F.; Haesebrouck, F.; Butaye, P.; Catry, B.; Dewulf, J. Prophylactic and Metaphylactic Antimicrobial Use in Belgian Fattening Pig Herds. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2012, 106, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maples, W.E.; Brorsen, B.W.; Peel, D.; Hicks, B. Observational Study of the Effect of Metaphylaxis Treatment on Feedlot Cattle Productivity and Health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 947585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Rodriguez, V.; Pfister, J.; Perreten, V.; Neumann, P.; Retschnig, G. The Dose Makes the Poison: Feeding of Antibiotic-Treated Winter Honey Bees, Apis Mellifera, with Probiotics and b-Vitamins. Apidologie 2022, 53, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credille, B.; Berghaus, R.D.; Jane Miller, E.; Credille, A.; Schrag, N.F.D.; Naikare, H. Antimicrobial Metaphylaxis and Its Impact on Health, Performance, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Contextual Antimicrobial Use in High-Risk Beef Stocker Calves. Journal of Animal Science 2024, 102, skad417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siwek, J. Evidence-Based Medicine: Common Misconceptions, Barriers, and Practical Solutions. afp 2018, 98, 343–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gudeta, T.G.; Terefe, A.B.; Mengistu, G.T.; Sori, S.A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Evidence-Based Practice and Its Associated Factors among Health Professionals in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2024, 24, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barends, E., Rousseau, D. M., & Briner, R. B. Evidence-Based Management: The Basic Principles; 2014. ISBN 9789462285057.

- Sohrabi, Z.; Zarghi, N. Evidence-Based Management: An Overview. Creative Education 2015, 6, 1776–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.R. The Underlying Interrelated Issues of Biosecurity. javma 2000, 216, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOAH Terrestrial Manual 2018 Biosafety and biosecurity: standard for managing biological risk in the veterinary laboratory and animal facilities. in; 2018.

- Beeckman, D.S.A.; Rüdelsheim, P. Biosafety and Biosecurity in Containment: A Regulatory Overview. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Overall condition of the bee colony | Total number of colonies | Number of bee colonies at microbiological risk | Number of bee colonies with deterioration of health, condition, or behaviour, and the appearance of clinical symptoms during the course of the experiment | Number of bee colonies with deterioration of health, condition, or behaviour, and the appearance of clinical symptoms after the experiment | Number of bee colonies rescued from microbiological risk (reduction and suppression of P. larvae in the microbiome |

The number of bee colonies in which microbiological risk was re-identified 14 days after the conclusion of the research program. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very good | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Good | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | Very good | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Good | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | Very good | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Good | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | Very good | 7 | 7 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Good | 2 | 2 | 1** | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Poor | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).