Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

An X-ray Diffraction pattern consists of the relevant information (the signal) and the noisy background. Under the assumption that they behave as the components of a two-dimensional mixture (bicomponent fluid) having slightly different physical properties related to the density-gradients, a Lattice Boltzmann Method is applied to disentangle the two different diffusive dynamics. The solution is numerically stable, computationally not demanding and, moreover, it provides an efficient increase of the signal-to-noise ratio for patterns blurred by poissonian noise and affected by collection data anomalies (fiber-like samples, experimental setup, etc.). The model has been succesfully applied to different resolution images.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A Fluidistic Approach

- Diffusion Equation. This equation models the process of substance spreading due to concentration gradients. It is typically written as , where c is the concentration of the substance, D is the diffusion coefficient, and is the Laplacian operator. It captures how substances diffuse through a medium over time.

-

Navier–Stokes Equations. These equations describe the motion of fluid substances and account for viscosity and external forces. They can be expressed as:, where is the fluid velocity, p is the pressure, is the kinematic viscosity, is the density, and represents external forces.

2.1. A Navier–Stokes Inspired Model

2.2. Lattice Boltzmann Method: Overview

- Discrete Lattice. The fluid is represented by particles moving on a fixed grid with discrete directions: the lattice dimensions (D) and the neighborhood (Q, the number of nearest neighbors, including the site itself) define the particular lattice Boltzmann method: e.g. D2Q9 means nine nearest neighbors for each site on a two-dimensional lattice .

- Collision Step. Particles collide and exchange momentum according to probabilistic rules.

- Streaming Step. After collisions, particles move to neighboring lattice sites.

- Macroscopic Variables. From the particle distribution functions, macroscopic quantities like density and velocity are computed.

2.3. Lattice Boltzmann Method: Application

3. Results and Conclusions

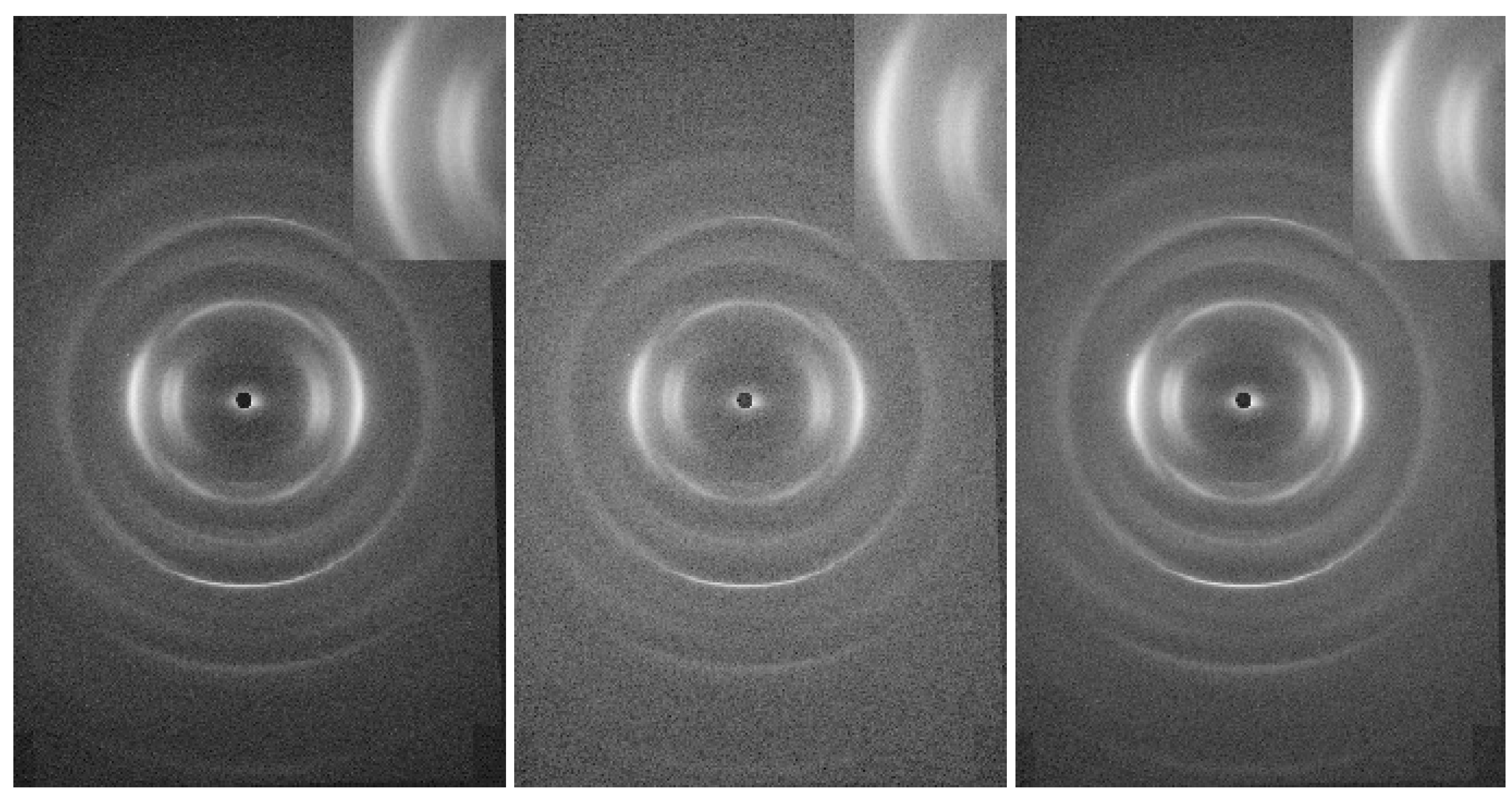

- diffraction peaks, that indicate the presence of crystalline regions while their position and intensity can help determine the fiber’s crystallinity and the arrangement of its molecular chains;

- intensity distribution of the peaks in the pattern, that can show how the crystalline regions are distributed and oriented relative to the fiber axis;

- azimuthal scans, that can be used to study the orientation of the crystallites around the fiber axis, revealing information about fiber alignment and texture.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pietsch, P.; Wood, V. X-Ray Tomography for Lithium Ion Battery Research: A Practical Guide. Annual Review of Materials Research 2017, 47, 451–479. [CrossRef]

- Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L.; Scattarella, F.; Scarcelli, G.; Siliqi, D.; Altamura, D.; Liebi, M.; Ladisa, M.; Bunk, O.; Giannini, C. Interfibrillar packing of bovine cornea by table-top and synchrotron scanning SAXS microscopy. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2016, 49, 1231–1239. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; Siliqi, D.; Bunk, O.; Beraudi, A.; Ladisa, M.; Altamura, D.; Stea, S.; Baruffaldi, F. Correlative Light and Scanning X-Ray Scattering Microscopy of Healthy and Pathologic Human Bone Sections. Scientific Reports 2012, 2(1), 2045–2322. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; Siliqi, D.; Ladisa, M.; Altamura, D.; Diaz, A.; Beraudi, A.; Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L.; Stea, S.; Baruffaldic, F.; Bunk, O. Scanning SAXS–WAXS microscopy on osteoarthritis-affected bone – an age-related study. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2014, 47, 110–117. [CrossRef]

- Terzi, A.; Storelli, E.; Bettini, S.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Salvatore, L.; Madaghiele, M.; Romano, A.; Siliqi, D.; Ladisa, M.; De Caro, L.; Quattrini, A.; Valli, L.; Sannino, A.; Giannini, C. Effects of processing on structural, mechanical and biological properties of collagen-based substrates for regenerative medicine. Scientific Reports 2018, 8(1), 2045–2322. [CrossRef]

- Altamura, D.; Lassandro, R.; Vittoria, F.A.; De Caro, L.; Ladisa, D.S.M.; Giannini, C. X-ray microimaging laboratory (XMI-LAB). Journal of Applied Crystallography 2012, 45, 869–873. [CrossRef]

- Ladisa, M.; Lamura, A. Diffusion-Driven X-Ray Two-Dimensional Patterns Denoising. Materials 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, A.A.; Bührer, M.; Leone, L.; Merlini, M.; Vigano, N.; Pelt, D.M.; Marone, F.; di Michiel, M.; Batenburg, K.J. Deep denoising for multi-dimensional synchrotron X-ray tomography without high-quality reference data. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1), 2045–2322. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, C.; Bi, X.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Hua, W.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. A machine learning model for textured X-ray scattering and diffraction image denoising. npj Computational Materials 2023, 9(1), 2057–3960.

- Oppliger, J.; Denner, M.M.; Küspert, J.; Frison, R.; Wang, Q.; Morawietz, A.; Ivashko, O.; Dippel, A.C.; Zimmermann, M.v.; Biało, I.; Martinelli, L.; Fauqué, B.; Choi, J.; Garcia-Fernandez, M.; Zhou, K.J.; Christensen, N.B.; Kurosawa, T.; Momono, N.; Oda, M.; Natterer, F.D.; Fischer, M.H.; Neupert, T.; Chang, J. Weak signal extraction enabled by deep neural network denoising of diffraction data. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 6(2), 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, C.; Fan, L.; Dong, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Zhanga, Y.; Dong, Y. Denoising an X-ray image by exploring the power of its physical symmetry. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2024, 57, 741–754. [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Fluid Mechanics, 2nd edition; Pergamon Press, 1987.

- Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Matthaeus, W.H. Recovery of the Navier–Stokes equations using a lattice-gas Boltzmann method. Physical Review A 1992, 45(8).

- He, X.; Luo, L.S. Lattice Boltzmann Model for the Incompressible Navier–Stokes Equation. Journal of Statistical Physics 1997, 88(3/4).

- He, X.; Luo, L.S. A priori derivation of the lattice Boltzmann equation. Physical Review E 1997, 55(6).

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Statistical Physics (Part 1), 3nd edition; Pergamon Press, 1980.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Physical Kinetics, 1st edition; Pergamon Press, 1981.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Mechanics, 3nd edition; Butterworth-Heinenann, 1976.

- Bhatnagar, P.; Gross, E.; Krook, M. A model for collision processes in gases. I. Small amplitude processes in charged and neutral one-component systems. Physical Review 1954, 94, 511–525.

- Kaushal, S.; Ansumali, S.; Boghosian, B.; Johnson, M. The lattice Fokker–Planck equation for models of wealth distribution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378. [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A Computational Approach to Edge Detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1986, PAMI-8, 679–698. [CrossRef]

- Broennimann, C.; Eikenberry, E.; Henrich, B.; Horisberger, R.; Hülsen, G.; Pohl, E.; Schmitt, B.; Schulze-Briese, C.; Suzuki, M.; Tomizaki, T.; Toyokawa, H.; Wagner, A. The PILATUS 1M detector. Journal of synchrotron radiation 2006, 13, 120–30. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2004, 13(4), 600–612.

- Siliqi, D.; De Caro, L.; Ladisa, M.; Scattarella, F.; Mazzone, A.; Altamura, D.; Sibillano, T.; Giannini, C. SUNBIM: a package for X-ray imaging of nano- and biomaterials using SAXS, WAXS, GISAXS and GIWAXS techniques. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2016, 49, 1107–1114. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The interested reader may refer to the papers cited herewith for further theoretical analysis. |

| 2 | In many applications, the two can be coupled, especially in cases involving heat transfer or pollutant dispersion in fluids. |

| 3 |

i.e. without kinetic term in the Lagrangian. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Unlike the numerical methods solving the system of linear equations traditionally used to describe the Navier–Stokes equations (e.g. gaussian elimination and back-sostitution). |

| 7 |

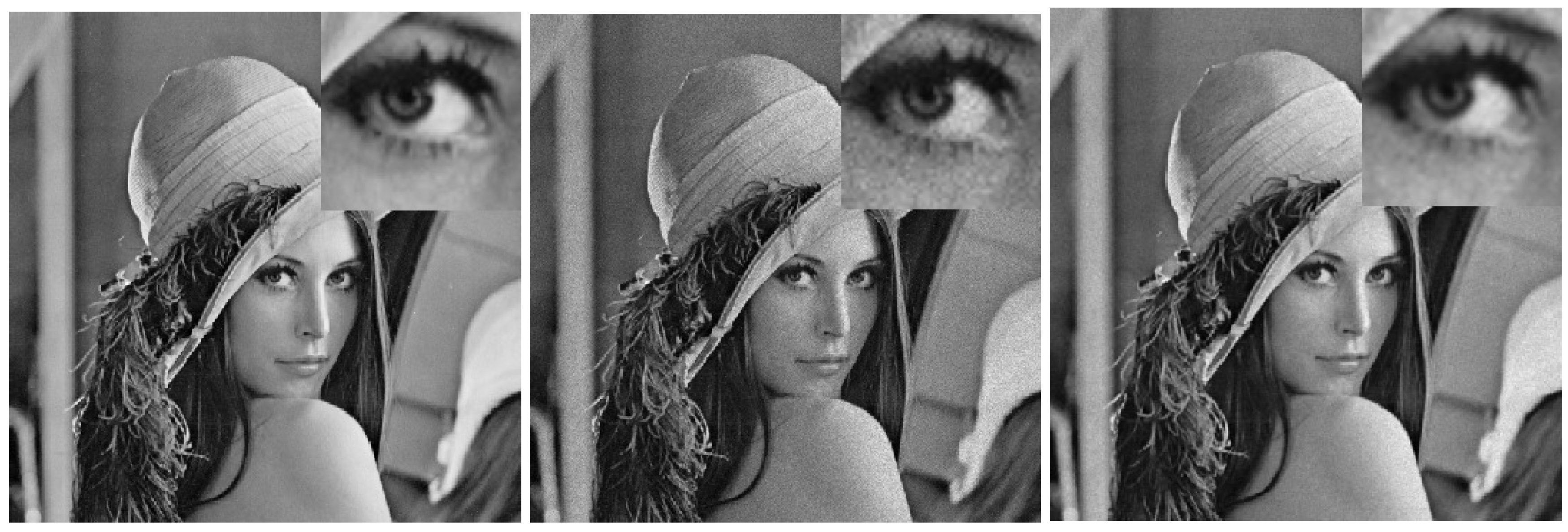

e.g. PSNR 34.76 vs 34.52 for Lenna image. |

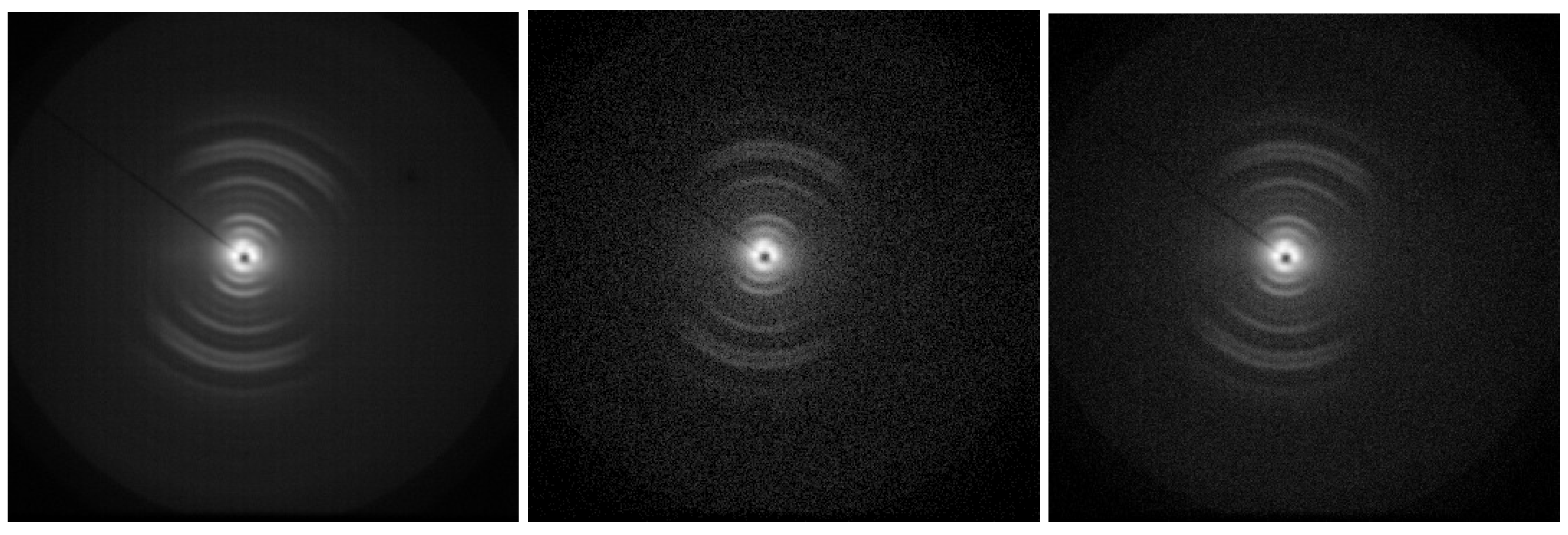

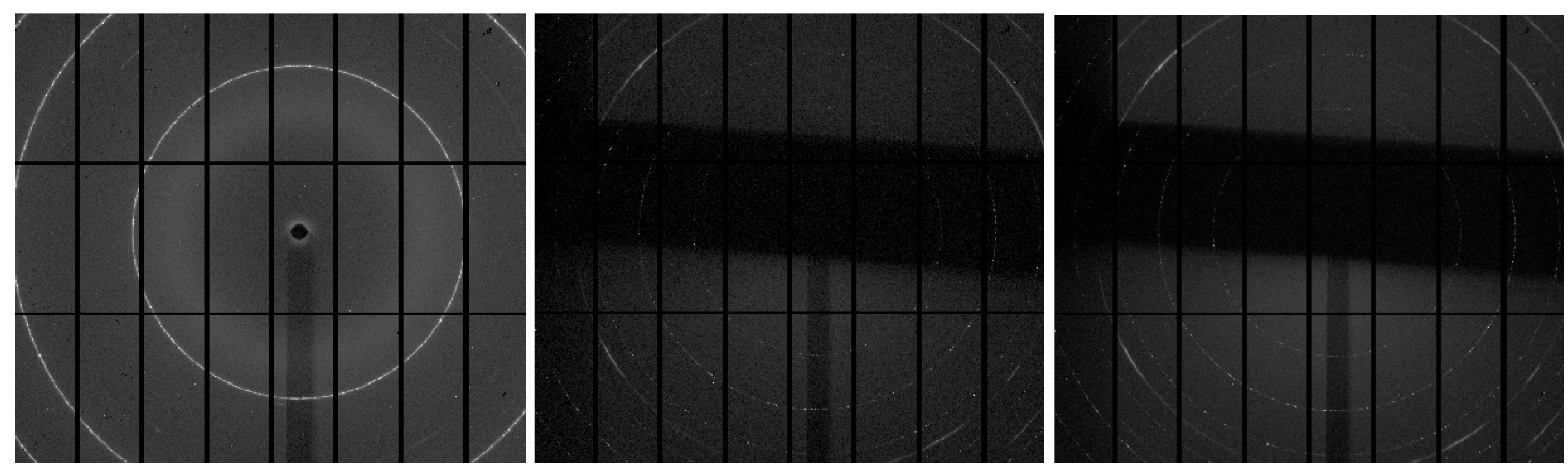

| image | Lenna | rat tendon | sam4 | S043XX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| resolution | 512×512 | 1024×1024 | 1600×2500 | 1679×1475 |

| 1.15 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | |

| 2.0 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | |

| noise | 0.05 | - | - | - |

| PSNR (ini.) | 31.33 | 25.94 | 30.91 | 18.10 |

| PSNR (fin.) | 34.76 | 30.76 | 34.75 | 18.28 |

| SSIM (ini.) | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.12 |

| SSIM (fin.) | 0.64 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).