1. Introduction

Growing needs for sustainable and biobased materials are fostering the emergence of new high-performance polymers with reduced environmental impact. Cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) as well as well as chitin nanofibrils (ChNF) and nanocrystals (ChNC) are gaining increasing interest as a platform for a wide range of applications in material science, medicine, and food packaging, to mention a few [

1,

2,

3]. Conventional nanocellulose production from lignocellulosic biomass, most frequently derived from wood, routinely involves harsh chemical extraction and energy-intensive fibrillation treatments [

4]. Globally increasing needs for the large-scale production of these polymers from terrestrial plant feedstocks is predicted to accelerate deforestation with foreseeable impact on global warming, to unbalance existing ecosystems, and to compete for arable land required for feeding a growing world population [

5]. Chitin production is presently mainly derived from marine crustacean processing industries [

6]. Similar to the currently established approaches for cellulose purification, the extraction of chitin also involves harsh chemical treatments for achieving demineralization and deproteinization of the crustacean shells [

7].

Interestingly, a growing number of studies signify the presence of both cellulose and chitin as constituents of the cell wall in a few microalgal species among them

Chlorella vulgaris [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Microalgae that produce both biopolymers cellulose and chitin via photosynthesis may have the potential to replace the above-mentioned classical feedstocks for the production of these biopolymers in a sustainable and renewable way.

Here, we focus on

C. vulgaris and describe initial steps towards a more environmentally-friendly cellulose and chitin extraction process, which we combine with the co-purification of a range of value-added bioactive compounds for increasing the economic viability of this so-called biorefinery process.

C. vulgaris, one of the leading species used for many algae-based products, exhibits high photosynthetic and CO

2 fixation activities and shows fast growth at industrial scale in aquaculture, totally independent from natural ecosystems [

12,

13]. Moreover, the

C. vulgaris biomass source is lignin free and allows “greener” extraction processes for obtaining cellulosic polymers.

As both biopolymers are constituents of the

C. vulgaris cell wall [

14,

15] and because they have a very similar chemical structure with the difference of a hydroxyl group in cellulose as compared to an acetamide group in chitin, we established a co-purification protocol that co-extracts both biopolymers with reasonable purity, as well as lipids and proteins with high extraction efficiencies. This achievement will allow in a near future to establish free-standing films composed of cellulose and chitin nanofibrils as a starting material for the development of new sustainable and biodegradable packaging products and as an inspiration for further innovative applications.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Microalgal Biomass

Dried Chlorella vulgaris biomass was purchased from the company Allma. The biomass was hydrated with sterile, deionized water prior to extraction (20% dry mass of C. vulgaris after hydration) to imitate a wet extraction condition, and used for the comparative assessment of green extraction conditions detailed in section 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4.

2.2 Extraction of Lipids and Pigments

Harsh solvent extraction using methanol and chloroform (2:1, v/v) (“Bligh and Dyer method”) [

16] has been used as reference to allow a comparison with the lipid extraction efficiency based on greener solvents. Solvents used for greener approaches were either pure ethanol or a mixture of ethanol and ethyl acetate (1:2, v/v) (“Green Bligh and Dyer”) inspired from the work of Breil et al. [

17]. Extractions were carried out in duplicate at room temperature for different extraction times (2 min, 10 min, 30 min) and different solvent-to-biomass ratios (3:1, 10:1) under constant stirring. The eco-friendly extraction condition maximizing the yield of lipids was kept for the next step.

2.3 Extraction of Proteins and Carbohydrates

The alkaline extraction was carried out with hot NaOH and three increasingly harsh extraction conditions were assessed by changing the extraction time, temperature, NaOH concentration, and solvent-to-biomass ratio. The extraction conditions used in the present study were inspired by articles reviewed in [

1]. Extractions were conducted in duplicate in an agitated hot bath. Details of the parameters can be found in

Table 1. The extraction condition maximizing the yield of proteins was kept for the next step.

2.4. Biopolymer Purification

The last purification step tested five different strategies. Extraction based on chlorinated bleach (1.7% NaClO

2) in acetate buffer (pH 4.9) (1:1, v/v) was used as reference method representing a non-ecofriendly purification process [

18]. More eco-friendly alternatives were tested such as chlorine-free bleach (H

2O

2), a harsher NaOH extraction, and a mixture of 80% acetic acid and 70% nitric acid (10:1, v/v) as inspired by the work of Updegraff [

19], or simply hot water. Extractions were conducted in duplicate in an agitated hot bath. Specific parameter details can be found in

Table 2.

2.5. Yield of Co-Products

2.5.1. Pigments

Solvent extractions (step 1) were conducted as detailed in chapter 2.2. After recovery of the extraction supernatant by centrifugation (4000 rcf, 3 min, 20 °C), a two-phase separation was performed to separate the organic and aqueous phase. After migration of the pigments into the organic phase (either chloroform or ethyl acetate), the concentration of pigments was assessed by spectrophotometry (DR3900, Hach). The concentrations of chlorophyll a and b were deduced according to the formula below.

Yields of pigments were calculated with the following equation:

2.5.2. Lipids

An aliquot of half of the total amount of organic solvent used during extraction and phase separation was evaporated to dryness under a flow of nitrogen at 40 °C. The dry residue was weighed and yields were determined by the following equation:

Yields were then corrected by subtracting the mass of pigments calculated above (chapter 2.5.1) as these were also present in the organic phase.

2.5.3. Proteins

Protein concentrations were assessed on the aqueous phase obtained after phase separation of the solvent extraction supernatant (step 1) or after the alkaline extraction (step 2) using a commercial kit (DC Protein Assay, Bio-Rad) containing two reagents dissolved in demineralized water: Reagent A contains an alkaline copper tartrate solution, and Reagent B contains a dilute Folin reagent.

A 25 µL aliquot of the aqueous phase was mixed with 125 µL of reagent A, then 1.0 mL of reagent B was added and the solution immediately vortexed. The sample was left to react for 15 min, and the absorbance was measured at 750 nm by spectrophotometry (DR3900, Hach). The protein concentration was determined from a standard curve prepared on the same day using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard. Yields of proteins were finally determined by the following equation:

2.6. Yield of the Residues

The moisture content of the biomass before extraction was assessed by comparing weights obtained before and after freeze drying to deduce the dry biomass weight. The residue was freeze dried after each extraction step (1, 2, 3) and the ratio of mass before and after extraction was used to calculate the yield:

A lower yield was used as an indication of increased purity of the residue.

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Gemini-SEM300, Zeiss) was used to visualize remaining impurities still present in the residue obtained after the third extraction step (chapter 2.4) and for making a comparative assessment of the relative purity of the residue after the different extraction procedures. Suspensions containing the purified residues were dried onto a silicon wafer. SEM high resolution images were obtained at an acceleration voltage of 1.5 or 3 kV, after sputter-coating a 10 nm thick Au/Pd layer onto the samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Design of the Biorefinery Process

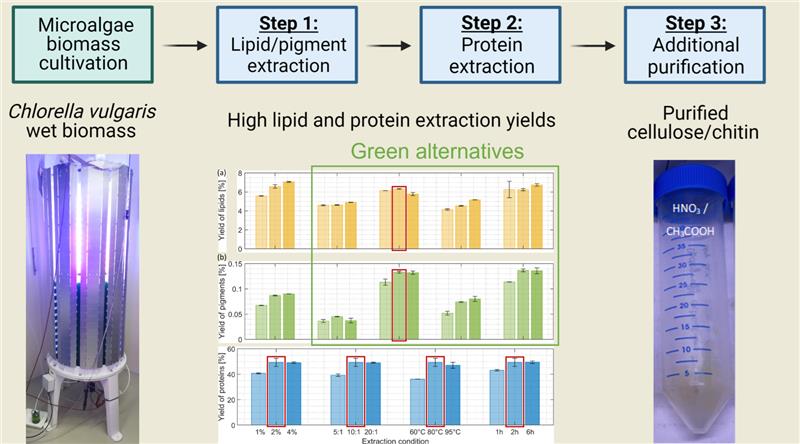

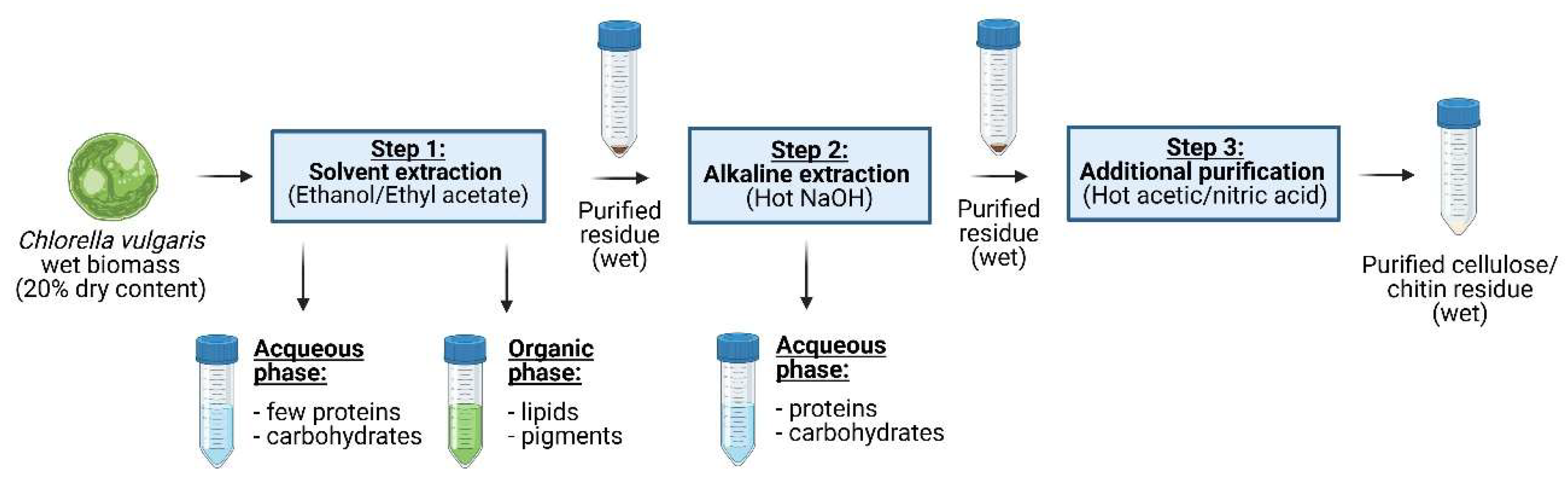

A fractionation and purification protocol has been developed to valorize microalgal co-products through a 3-step biorefinery process (

Figure 1). In the first step lipids were extracted and parts of the pigments using different solvents. The purified residue was then passed through a hot NaOH extraction process to remove proteins. Finally, a purification step with a mixture of acetic/nitric acid was applied to obtain cellulose and chitin with reasonable purity. The complete extraction procedure was carried out on wet biomass and the purified residues have been kept wet during the entire process, as potential bioplastic manufacturing would require “never dried” purified residues.

3.2. Yield of Co-Products

3.2.1. Lipids

Following the above-described outline (section 3.1), we compared the efficacy of harsher and milder extraction conditions to obtain optimal yields for co-products (lipids, proteins, pigments). Harsh solvent extraction using chloroform and methanol (“Bligh and Dyer method”) [

16], which is the gold standard for lipid extraction from microalgae or other microorganisms, has been applied here as reference to allow a comparison with greener solvents as for instance pure ethanol or a mixture of ethanol and ethyl acetate (“Green Bligh and Dyer”) inspired from the work of Breil et al. [

17].

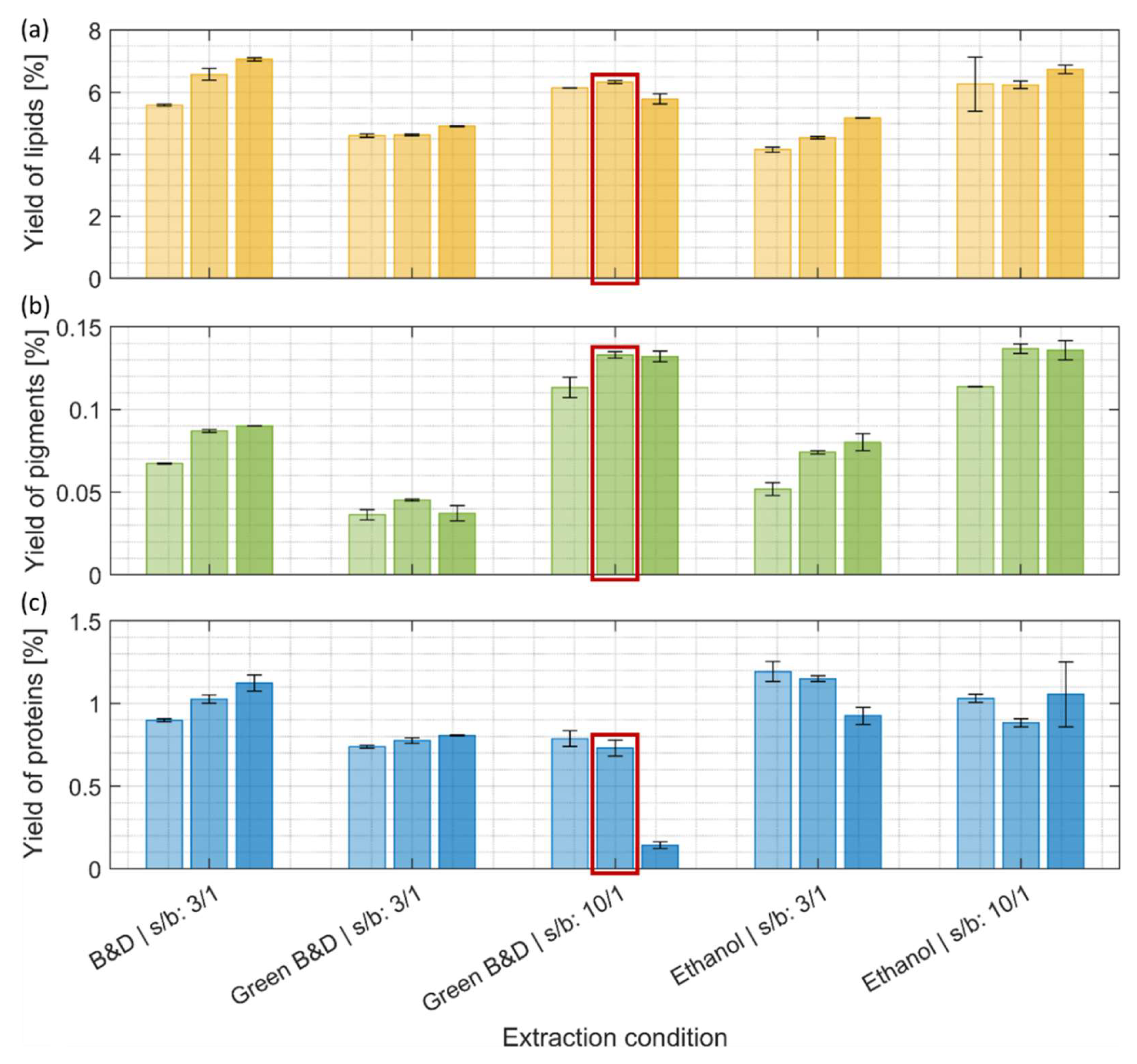

The conventional Bligh and Dyer method for lipid extraction was effective at a low (3:1) solvent-to-biomass ratio and higher yields were obtained with longer extraction times (

Figure 2, a). However, similar amounts of lipid were also obtained with more eco-friendly ethanol and ethanol/ethyl acetate extractions using a higher solvent-to-biomass ratio (10:1). In general, the yield of extracted lipid increased with higher solvent-to-biomass ratios and prolonged extraction times, with the exception of the harshest condition for the ethyl acetate/ethanol extraction (Green Bligh and Dyer at 10:1 ratio and 30 min) (

Figure 2, a). This drop in extraction efficiency might be explainable by the transesterification of lipids with ethyl acetate making them more water soluble, therefore less present in the organic phase where lipids were quantified.

To date, solvent extraction methods have most frequently been used for lipid extraction, as they provide high lipid recovery [

22,

23,

24]. Among these solvents, “greener” ones like ethanol and ethyl acetate/ethanol mixtures are gaining increasing importance as they are biocompatible and have a lower risk to human health. In comparison to chloroform and methanol they exhibit for instance no negative genotoxicity and long-term carcinogenicity effects [

25].

The data of the present study indicate that for a given biomass greener extractions needed slightly more than 3 times the amount of solvent for being as efficient as the conventional Bligh and Dyer extraction method. The finding that solvent to biomass ratio has the highest impact on the lipid extraction efficiency for the greener solvent ethanol, followed by the extraction time has also been demonstrated on the wet biomass of the microalga

Picochlorum sp. and is consistent with our results [

26].

In the following we would like to highlight some advantages of the greener solvents ethanol and ethyl acetate as compared to those derived from fossil fuels such as methanol (polar solvent) and chloroform (non-polar) solvent.

Greener solvents with medium polarity, may be preferred for the extraction of lipids from wet biomass. High contents of water in the wet biomass can inhibit the contact between lipids and non-polar solvents, such as chloroform. Thus, the influence of water can be diminished and the extraction yields can be increased by using solvents with medium polarity (e.g., ethyl acetate/ethanol mixtures) [

23].

Moreover, ethanol is regarded as a food-grade solvent and ethyl acetate, which is contained in many fruits, is for instance used for the removal of caffeine in coffee or tea [

27]. These aspects may be relevant, if considering lipid extraction from microalgae biomass for animal or human food applications.

Finally, if lipid extraction from microalgae biomass is not intended for food applications but for biofuel production, ethyl acetate has been shown to have a quite high selectivity for the extraction of neutral lipids (NLs, including triacylglycerol, diglyceride and mono-glyceride), which are of interest as a source of biologically produced diesel fuel substitute [

28].

3.2.2. Pigments

Two types of chlorophyll, a and b, are present in green microalgae like

C. vulgaris and they can be a relevant feedstock for the increasing industrial needs of these pigments [

29]. Mixtures of chloroform/methanol have shown to be efficient for the extraction of chlorophyll from algal cultures [

30]. In our present study the Bligh and Dyer extraction also provided reasonable pigment extraction results (

Figure 2, b). For all tested conditions the yield of extracted chlorophyll a and b generally increased with prolonged incubation times, with a maximum reached after 10 min of extraction (

Figure 2, b). At low solvent-to-biomass ratio (3:1), the extraction with ethanol yielded similar amounts of pigments, as obtained by the Bligh and Dyer method, while only half of the amount was obtained with the mixture of ethanol and ethyl acetate. A higher solvent-to-biomass ratio (10:1) resulted in a 50% increase in pigment yield in case of the ethanol extraction and 200% for the ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture as compared to the lower solvent-to-biomass ratio condition. At these elevated solvent-to-biomass ratios both greener extraction methods yielded similar results.

It is worth mentioning that chlorophylls are gaining increasing commercial relevance as natural pigments for the coloration of food, cosmetics and pharmaceutical products [

31]. In addition to the color providing characteristics, they also improve the preservation in food storage as they have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Moreover, they exhibit a positive influence on human health as they improve the immune system and they possess antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic as well as wound healing properties [

29,

31]. Chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b from edible plants are approved by European legislations to be marketed after solvent extraction [

29]. Our results indicate that these pigments can efficiently be extracted from

C. vulgaris by using eco-friendly extraction methods.

3.2.3. Proteins

C. vulgaris is considered as a microalga with high protein content and protein quality, as its essential amino acid composition meets the dietary requirements for human consumption [

32,

33]. For enhancing the bioavailability of proteins, they need to be extracted from microalgal biomass [

34]. The solvent extractions described in chapter 3.2.1 and 3.2.2 were adapted for the fractionation and purification of lipids and pigments and therefore showed only low performance yields for the extraction of proteins (around 1% maximum) (

Figure 2, c). We still monitor these protein extraction yields to document that there are no significant protein losses after the lipid and pigment extraction step.

The most quantitative protein extraction step as detailed in the following was performed on the defatted biomass remaining from extraction with the ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture (10:1, 10 min), which removed lipids and pigments in the previous step as efficiently as pure ethanol (

Figure 2, a + b). The decision in favour of the ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture was justified by the fact that pure ethanol and the subsequent addition of ethyl acetate for the 2-phase separation step would result in a three times higher solvent consumption than by directly using the ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture [

17].

In order to achieve high protein extraction yields, alkaline extraction with NaOH is regarded as the most favorable method as it increases protein solubility and can be performed at relatively low process costs [

35].

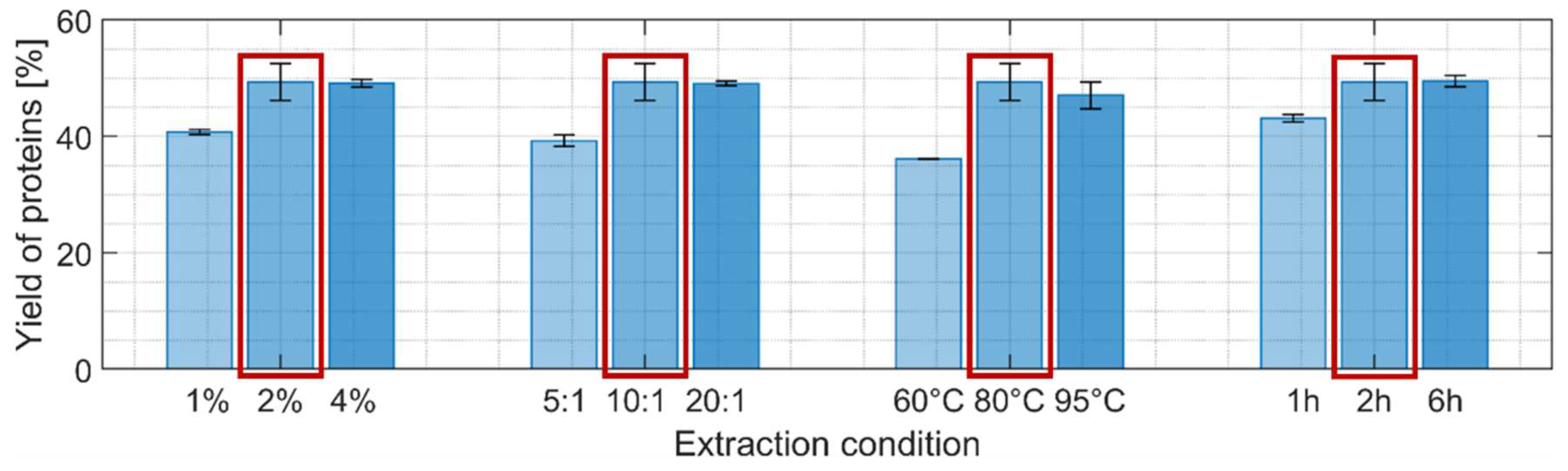

Four different parameters were individually varied using a hot NaOH extraction process: NaOH concentration, solvent-to-biomass ratio, temperature and extraction time, while keeping the other parameters at intermediate harshness level (

Figure 3). Higher protein extraction yields were obtained when each of the four parameters was independently increased with a maximum reached for the reference scenario: 56% yield if the lipid-free biomass is used as reference (i.e. after extraction step 1) or close to 50% when taking the initial biomass dry weight as reference. This indicates that almost all the proteins were extracted after the two first extraction steps since the supplier of the biomass indicated a protein content of 55%.

The lipid and protein content in microalgae is influenced by a number of factors as for instance the composition of growth media and abiotic stress conditions [

36,

37]. Lipid capabilities of

C. vulgaris can reach values of 30%-40% of dry weight [

38]. As our lipid yield was around 6-7% of dry weight, but still in a normal range of lipid content for

C. vulgaris our results indicate that the culturing conditions used to grow this biomass of commercial origin were focusing on increasing protein synthesis, while decreasing lipid in the cells, as it was found in other studies [

39].

3.3. Overall Yields and Purity of the Residue

3.3.1. Yield of the Residue After Each Extraction Step

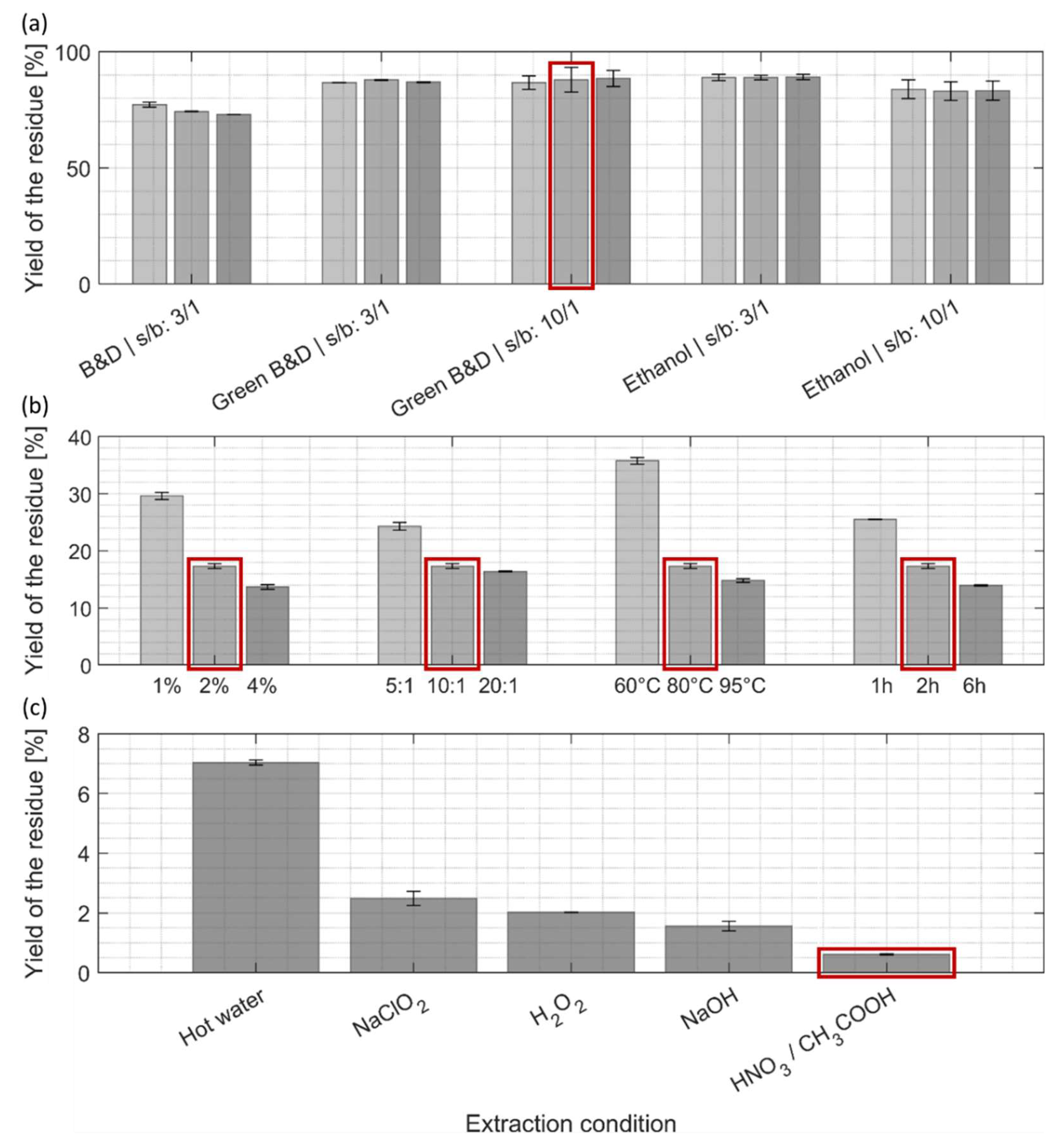

The following paragraphs summarize the yields and mass losses of the residue after each of the three extraction steps in comparison to the initial biomass dry weight prior to any extraction (

Figure 4). The sequential and selective extraction of lipids, pigments and proteins results in measurable mass losses of the residue but increases stepwise also the overall purity of cellulose/chitin biopolymers, which are further purified in the last step of the process as illustrated in chapter 3.3.2.

After the first lipid/pigment extraction step (

Figure 4, a), the yields of extracted residue remained quite high, ranging from 85-90% for the two green alternatives, and were slightly lower (around 75%) for the Bligh and Dyer method. For all different treatments the prolongation of the extraction time, and higher solvent-to-biomass ratio, did not significantly enhance the extraction yield of the residues.

The residue remaining from the first extraction step with ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture (ratio 10:1, 10min), was used for the second, protein extraction step (

Figure 4, b). A significant drop in yield could be observed for each of the four extraction parameters and was more pronounced for harsher chemical treatments and longer incubation times. This decrease in yield of the residue can be attributed to a mass loss due to efficient protein extraction (

Figure 3), but might also be due to a partial removal of carbohydrates as similar treatments were shown to efficiently extract hemicellulose in other microalgae species and different kinds of monosaccharides in

Chlorella [

18,

40,

41]. As we were looking for a compromise that maximized protein extraction yields at not too harsh conditions (

Figure 3) by still achieving reasonable mass yields of the residue (

Figure 4, b) it was decided to keep the intermediate condition (2% NaOH, ratio 10:1, 80 °C, 2h) for the next extraction step.

The last extraction step (

Figure 4, c), which compares five different treatments that are detailed in

Table 2, is meant to obtain purified cellulose/chitin biopolymers. One non-eco-friendly purification process was used as reference (sodium chlorite, NaClO

2), as it was reported in most common cellulose purification protocols from algal biomass [

1], and four more eco-friendly alternatives. Overall, yields of purified biopolymer residues were quite low in comparison to the initial biomass dry weight. A recent study has determined a total protein content of 56 % and a carbohydrate content of 14 % of the total biomass for

C. vulgaris [

40]. However, these numbers may vary depending on the taxonomic classification, cultivation conditions and metabolic status of the cells [

42]. Whereas the protein yield of our extraction procedure (

Figure 3) is in the range of the mentioned analysis by Weber et al. [

40] the low yield in cellulose/chitin biopolymers as compared to the 14 % of carbohydrate content determined by Weber et al. [

40] cannot readily be compared with our results, because their study determined the total amount of all different classes of monomeric sugars present in

C. vulgaris, which is obviously higher than the cellulose/chitin mass content. Moreover, our results may point to the fact that the culturing conditions for the

C. vulgaris biomass we used for extraction were not optimized for high carbohydrate biosynthesis [

39].

Among all tested conditions, extraction with hot water extracted residual impurities with the lowest efficiency (

Figure 4, c), although it still removed around 60% of the dry mass when taking the lipid/protein-free biomass as reference. The other tested conditions resulted in significantly lower yield for the dried residue suggesting for higher purity as compared to hot water extraction: 35% of the yield obtained by hot water extraction for NaClO

2, 30% for H

2O

2, 20% for NaOH and 10% for the mixture of nitric/acetic acid. Our results show that the common reference scenario (NaClO

2) might not be the best option for cellulose/chitin purification of

C. vulgaris, while several greener alternatives are yielding higher purity. The treatment with nitric/acetic acid was in our case the best performing purification process, although it has not been reported so far for routine cellulose or chitin purification processes to the best of our knowledge.

3.4.2. Purity of the Residue Containing Cellulose and Chitin Biopolymers

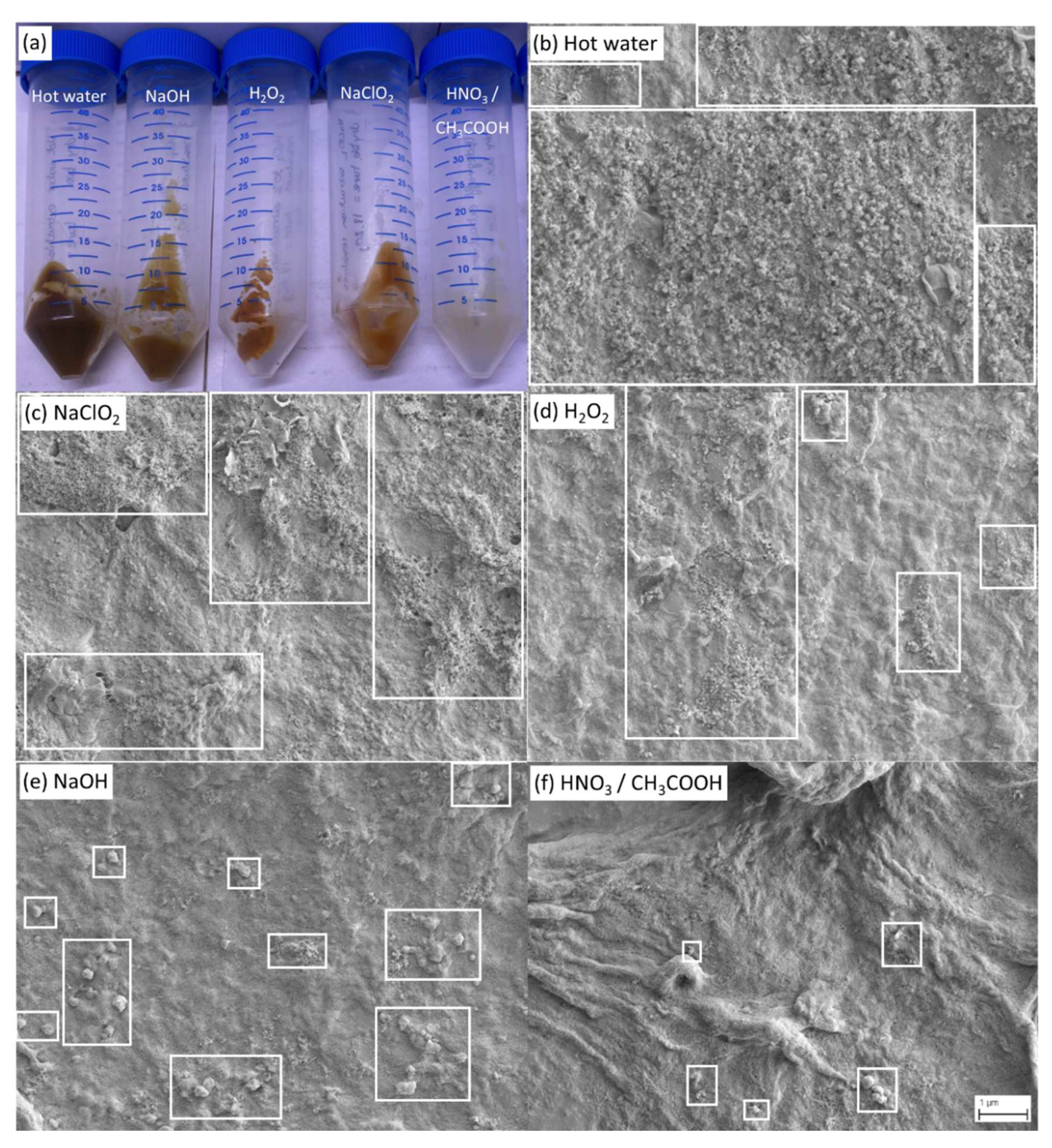

The visual inspection and the scanning electron microscopic analysis of the residues obtained after the last extraction step (

Figure 5) validate that the trends in the loss of masses (

Figure 4, c) inversely correlate with the level of purity of the residue as they follow the same ranking.

Macroscopic observations (

Figure 5, a) showed that the residue obtained after nitric/acetic acid (HNO

3/CH

3COOH) treatment exhibits a yellow-white color, closely related to the natural color of cellulose and chitin, while more brownish residues were observed for the other extraction conditions indicating that they presumably contain a higher level of impurities.

This trend was then verified by scanning electron microscopy analysis (

Figure 5, b-f). Whereas a network of fibers was observable for all treatments indicating that all the final extraction steps principally yield cellulose/chitin biopolymers, however with a different degree of purity. We show in

Figure 5, b-f representative SEM images at lower magnification for each of the extraction steps to better visualize the overall extent of the impurities, whereas higher magnification images can be found in the supplementary information that show the biopolymer networks in better detail. Treatments resulting in a lower purity (hot water, NaClO

2, H

2O

2) usually contained a large amount of small sized particles representing residual impurities (

Figure 5, b-d), while more efficient treatments (NaOH, HNO

3/CH

3COOH) showed significantly less small-sized impurities and rarely contained particles of larger sizes (

Figure 5, e-f). Again, the trend of the degree of purity of the residue as documented by SEM is inversely correlated to the residue yield shown in

Figure 4.

4. Conclusion

C. vulgaris is gaining increasing relevance as a new feedstock of cellulose and chitin biopolymers suitable for the production of many kinds of nanomaterials. We established a biorefinery process mainly using greener solvents and chemicals that allow the fractionation and purification of lipids, pigments and proteins as well as the co-purification of cellulose and chitin, from C. vulgaris biomass. For the different value-added compounds, we reached extraction efficiencies comparable to the most common but more toxic, fuel-derived solvent processes. High protein extraction efficiency was also obtained by NaOH treatment, reaching more than 90% of the protein content announced in the biomass. Finally, a highly pure network of biopolymer fibers was obtained by a final purification step using a mixture of acetic/nitric acid, achieving better purification efficiency than less environmentally-friendly conventional methods.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Enio Zanchetta: Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Baptiste Mercier: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation. Maxime Frabboni: Investigation, Data Curation. Eya Damergi: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Methodology. Christian Ludwig: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. Horst Pick: Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Nestlé SA (EPFL-Nestlé grant, project Biopack).

Appendix A

Supplementary data: E-supplementary data of this work can be found in online version of the paper.

References

- Zanchetta, E.; Damergi, E.; Patel, B.; Borgmeyer, T.; Pick, H.; Pulgarin, A.; Ludwig, C. Algal Cellulose, Production and Potential Use in Plastics: Challenges and Opportunities. Algal Res 2021, 56, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serventi, L.; He, Q.; Huang, J.; Mani, A.; Subhash, A.J. Advances in the Preparations and Applications of Nanochitins. Food Hydrocolloids for Health 2021, 1, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trache, D.; Tarchoun, A.F.; Derradji, M.; Hamidon, T.S.; Masruchin, N.; Brosse, N.; Hussin, M.H. Nanocellulose: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications. Front Chem 2020, 8, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isogai, A. Wood Nanocelluloses: Fundamentals and Applications as New Bio-Based Nanomaterials. Journal of Wood Science 2013, 59, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Coe, M.; Walker, W.; Verchot, L.; Vandecar, K. The Unseen Effects of Deforestation: Biophysical Effects on Climate. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2022, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, I.; Özogul, F.; Regenstein, J.M. Industrial Applications of Crustacean By-Products (Chitin, Chitosan, and Chitooligosaccharides): A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2016, 48, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, I.; Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan Preparation from Marine Sources. Structure, Properties and Applications. Mar Drugs 2015, 13, 1133–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapaun, E.; Reisser, W. A Chitin-like Glycan in the Cell Wall of a Chlorella Sp. (Chlorococcales, Chlorophyceae). Planta 1995, 197, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burczyk, J.; Śmietana, B.; Termińska-Pabis, K.; Zych, M.; Kowalowski, P. Comparison of Nitrogen Content Amino Acid Composition and Glucosamine Content of Cell Walls of Various Chlorococcalean Algae. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, C.A.; Mock, T.; Armbrust, E.V. Chitin in Diatoms and Its Association with the Cell Wall. Eukaryot Cell 2009, 8, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latil de Ros, D.G.; Lòpez Cerro, M.T.; Ruiz Canovas, E.; Durany Turk, O.; Segura de Yebra, J.; Mercadé Roca, J. Chitin and Chitosan Producing Methods 2016.

- Adamczyk, M.; Lasek, J.; Skawińska, A. CO2 Biofixation and Growth Kinetics of Chlorella Vulgaris and Nannochloropsis Gaditana. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2016, 179, 1248–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyande, A.K.; Chew, K.W.; Rambabu, K.; Tao, Y.; Chu, D.T.; Show, P.L. Microalgae: A Potential Alternative to Health Supplementation for Humans. Food Science and Human Wellness 2019, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, J.F.L.; Razafitianamaharavo, A.; Bihannic, I.; Offroy, M.; Lesniewska, N.; Sohm, B.; Le Cordier, H.; Mustin, C.; Pagnout, C.; Beaussart, A. New Insights into the Effects of Growth Phase and Enzymatic Treatment on the Cell-Wall Properties of Chlorella Vulgaris Microalgae. Algal Res 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchetta, E.; Ollivier, M.; Taing, N.; Damergi, E.; Agarwal, A.; Ludwig, C.; Pick, H. Abiotic Stress Approaches for Enhancing Cellulose and Chitin Production in Chlorella Vulgaris. Bioresour Technol In press. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breil, C.; Abert Vian, M.; Zemb, T.; Kunz, W.; Chemat, F. “Bligh and Dyer” and Folch Methods for Solid–Liquid–Liquid Extraction of Lipids from Microorganisms. Comprehension of Solvatation Mechanisms and towards Substitution with Alternative Solvents. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-R.; Kim, K.; Mun, S.C.; Chang, Y.K.; Choi, S.Q. A New Method to Produce Cellulose Nanofibrils from Microalgae and the Measurement of Their Mechanical Strength. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 180, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Updegraff, D.M. Semimicro Determination of Cellulose in Biological Materials. Anal Biochem 1969, 32, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as Well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J Plant Physiol 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ramakritinan, C.M.; Kumaraguru, A.K. Solvent Extraction and Spectrophotometric Determination of Pigments of Some Algal Species from the Shore of Puthumadam, Southeast Coast of India. International Journal of Oceans and Oceanography 2010, 4, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus, S.S.; Ferreira, G.F.; Moreira, L.S.; Maciel, M.R.W.; Maciel Filho, R. Comparison of Several Methods for Effective Lipid Extraction from Wet Microalgae Using Green Solvents. Renew Energy 2019, 143, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Keum, Y.S. Advances in Lipid Extraction Methods—a Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Martins, A.P.; Pinto, C.A.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J.; Barba, F.J. Extraction of Lipids from Microalgae Using Classical and Innovative Approaches. Food Chem 2022, 384, 132236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyao, A.S.; Villasica, S.L.G.; Dela Peña, P.L.L.; Go, A.W. Extraction of Lipids from Spent Coffee Grounds with Non-Polar Renewable Solvents as Alternative. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 119, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Xiang, W.; Sun, X.; Wu, H.; Li, T.; Long, L. A Novel Lipid Extraction Method from Wet Microalga Picochlorum Sp. at Room Temperature. Mar Drugs 2014, 12, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalakshmi, K.; Raghavan, B. Caffeine in Coffee: Its Removal. Why and How? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1999, 39, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Z. Characteristics of Lipid Extraction from Chlorella Sp. Cultivated in Outdoor Raceway Ponds with Mixture of Ethyl Acetate and Ethanol for Biodiesel Production. Bioresour Technol 2015, 191, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Manna, M.S.; Bhowmick, T.K.; Gayen, K. Extraction of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids from Dry and Wet Biomass of Isolated Chlorella Thermophila: Optimization of Process Parameters and Modelling by Artificial Neural Network. Process Biochemistry 2020, 96, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.W. Chloroform–Methanol Extraction of Chlorophyll a. Canadian journal of fisheries and aquatic sciences 1985, 42, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, B.; Mou, H.; Chen, F.; Yang, S. Microalgae-Derived Pigments for the Food Industry. Mar Drugs 2023, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Micro-Algae as a Source of Protein. Biotechnol Adv 2007, 25, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tibbetts, S.M.; McGinn, P.J. Microalgae as Sources of High-Quality Protein for Human Food and Protein Supplements. Foods 2021, 10, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M. Algal Proteins: Extraction, Application, and Challenges Concerning Production. Foods 2017, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongthai, S.; Lim, S.T.; Rawdkuen, S. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction of Rice Bran Protein Using Response Surface Methodology. J Food Biochem 2017, 41, e12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Xia, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Nitrate Concentration-Shift Cultivation to Enhance Protein Content of Heterotrophic Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris: Over-Compensation Strategy. Bioresour Technol 2017, 233, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, J.; Fa, Y.; Liu, X.; Lindblad, P. Enhancing Microalgal Lipid Accumulation for Biofuel Production. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1024441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, B.; She, X.; Zhao, F.; Cao, Y.; Ren, D.; Lu, J. Lipid Production and Composition of Fatty Acids in Chlorella Vulgaris Cultured Using Different Methods: Photoautotrophic, Heterotrophic, and Pure and Mixed Conditions. Ann Microbiol 2014, 64, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Angelidaki, I.; Georgakakis, D. Microalgal Carbohydrates: An Overview of the Factors Influencing Carbohydrates Production, and of Main Bioconversion Technologies for Production of Biofuels. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 96, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, S.; Grande, P.M.; Blank, L.M.; Klose, H. Insights into Cell Wall Disintegration of Chlorella Vulgaris. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.B.; Hamed, M.B.B.; Kassouar, S.; Abi Ayad, S.E.-A. Physicochemical Analysis of Cellulose from Microalgae Nannochloropsis Gaditana. Afr J Biotechnol 2016, 15, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Baudelet, P.H.; Ricochon, G.; Linder, M.; Muniglia, L. A New Insight into Cell Walls of Chlorophyta. Algal Res 2017, 25, 333–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).