Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction and PCR Conditions

2.3. Polymorphism in the ASIP Gene

2.4. Analysis of Polymorphisms in the MC1R Gene

2.5. MC1R Polymorphism Analysis in Individual Samples by PCR-RFLP

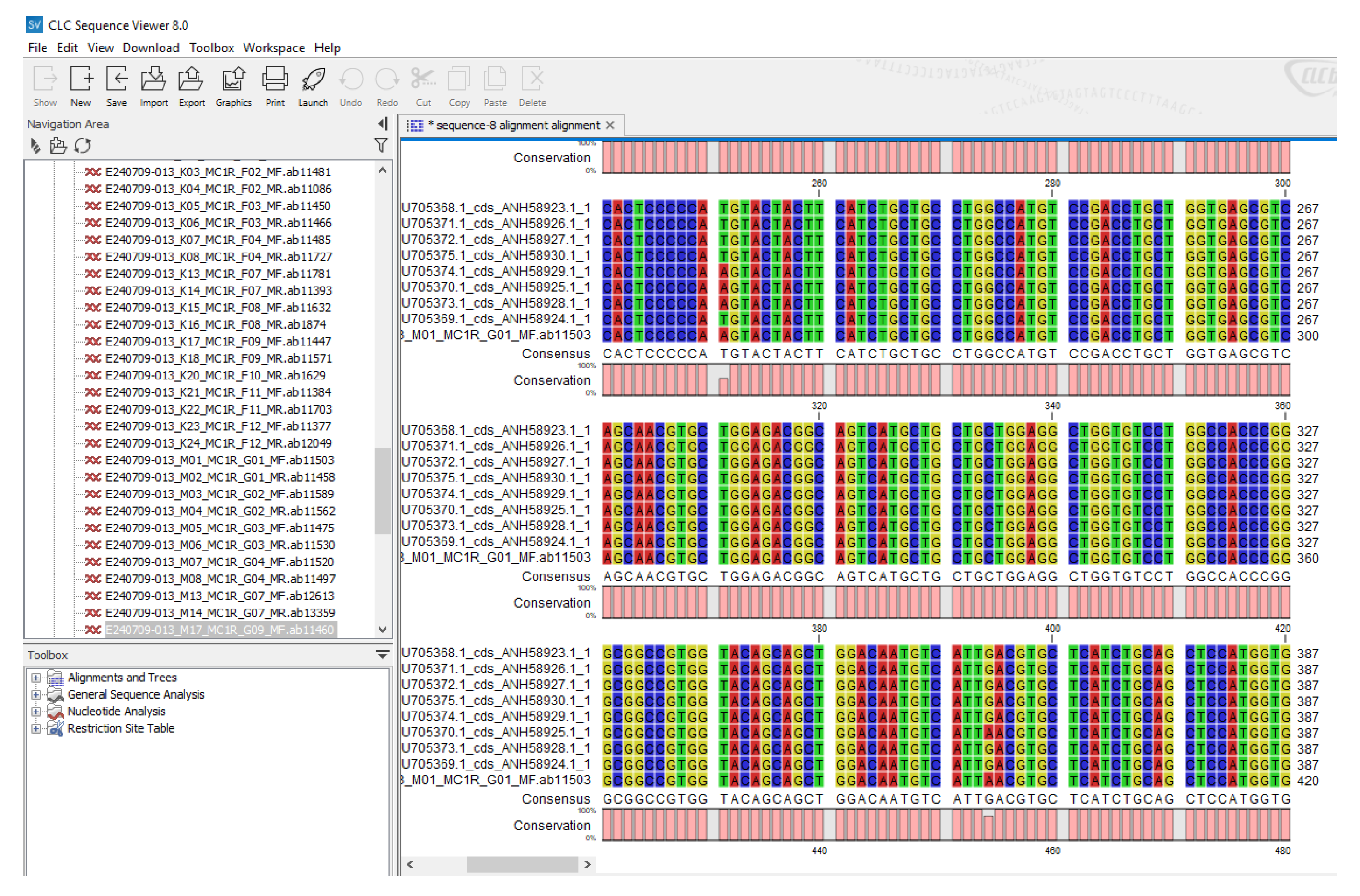

2.6. SNPs Identification and Genotyping /Sequencing of MC1R Gene

3. Results

3.1. Relationship Between ASIP Polymorphisms and Coat Colour in Sheep

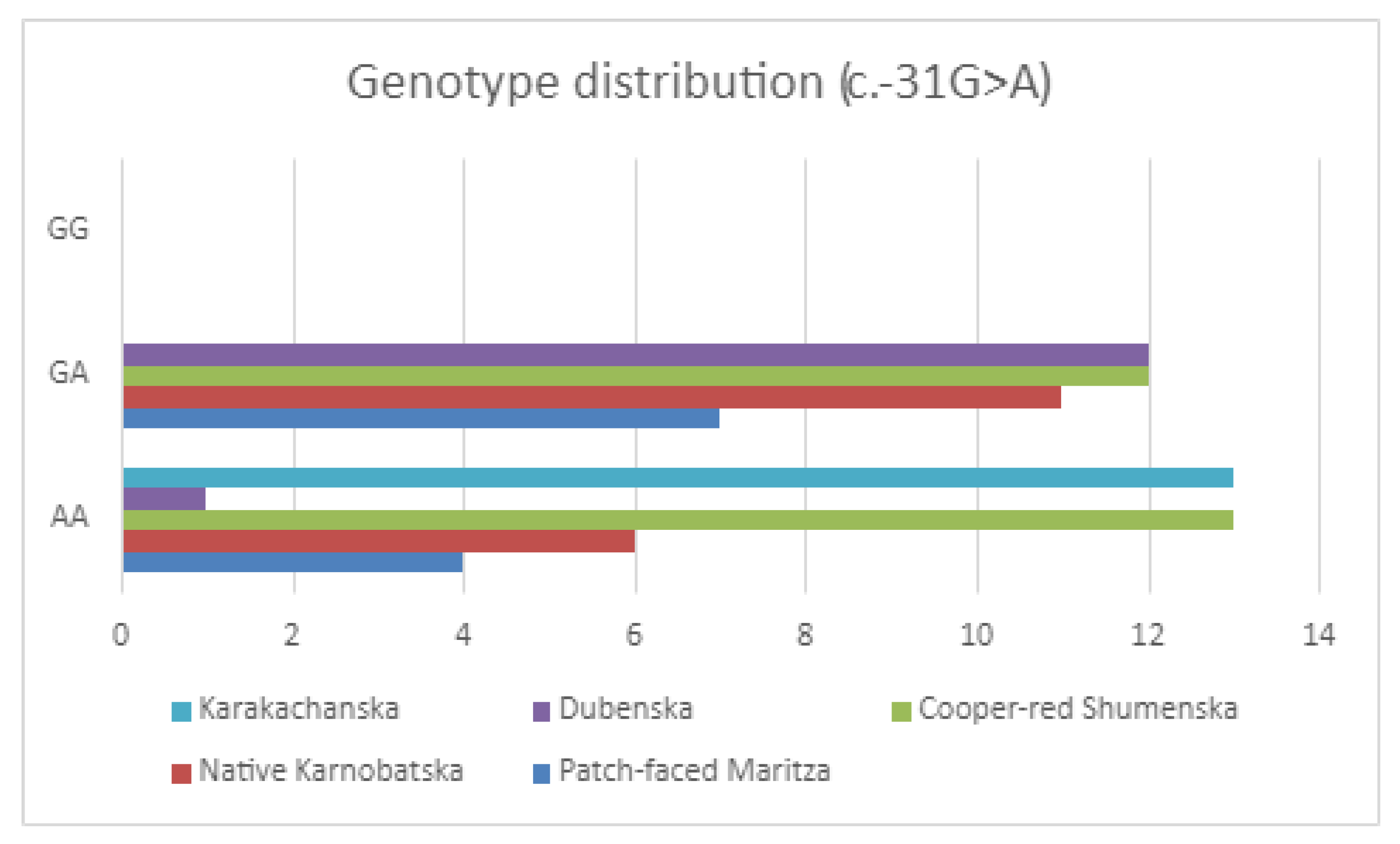

3.1.1. ASIP Genotypes

3.2. MC1R Polymorphism Analysis in Individual Samples by PCR-RFLP

3.2.1. Genotyping of the Mutation (c.361G > A; p.D121N)

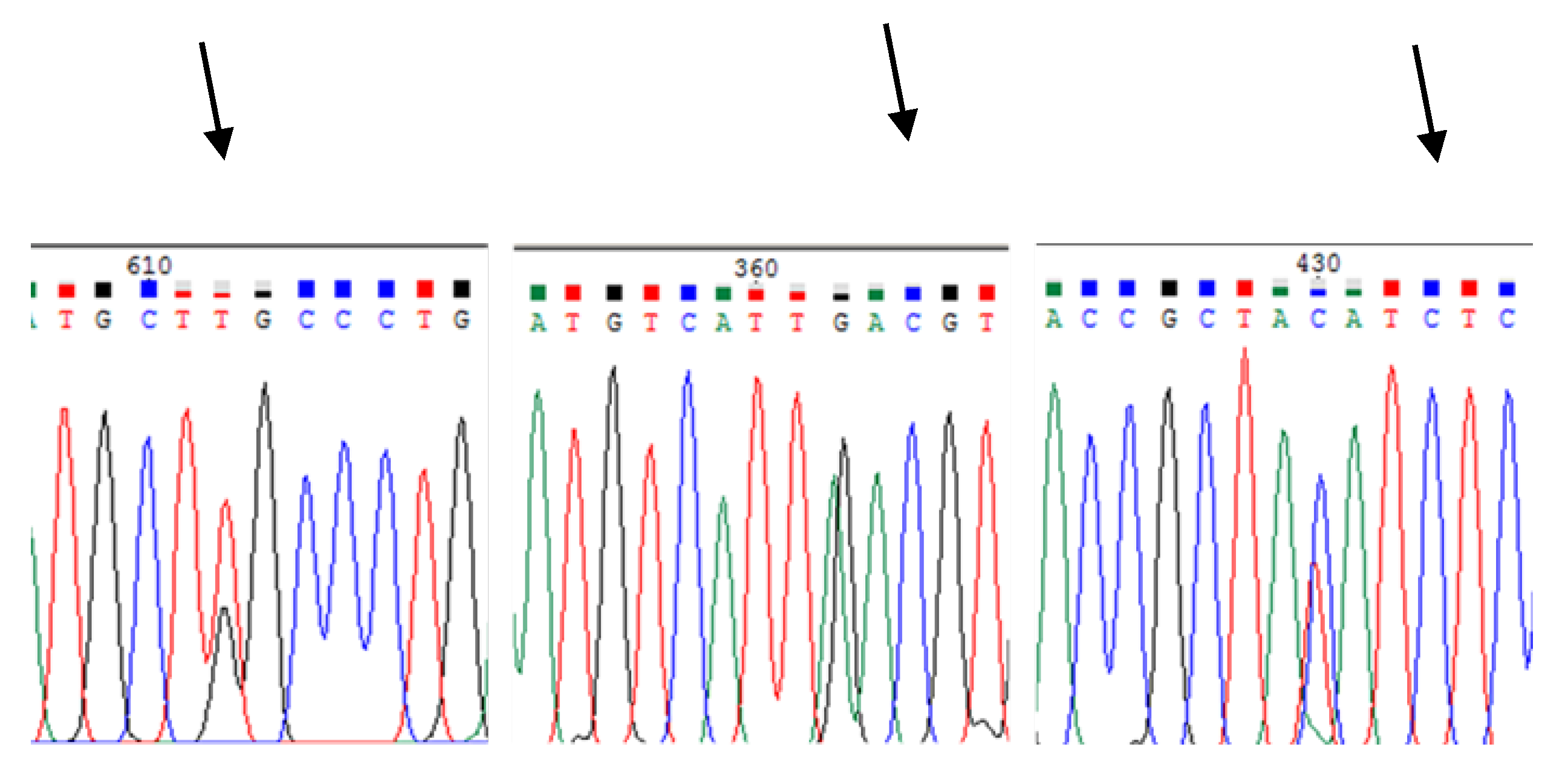

3.2.2. SNPs Identification and Genotyping

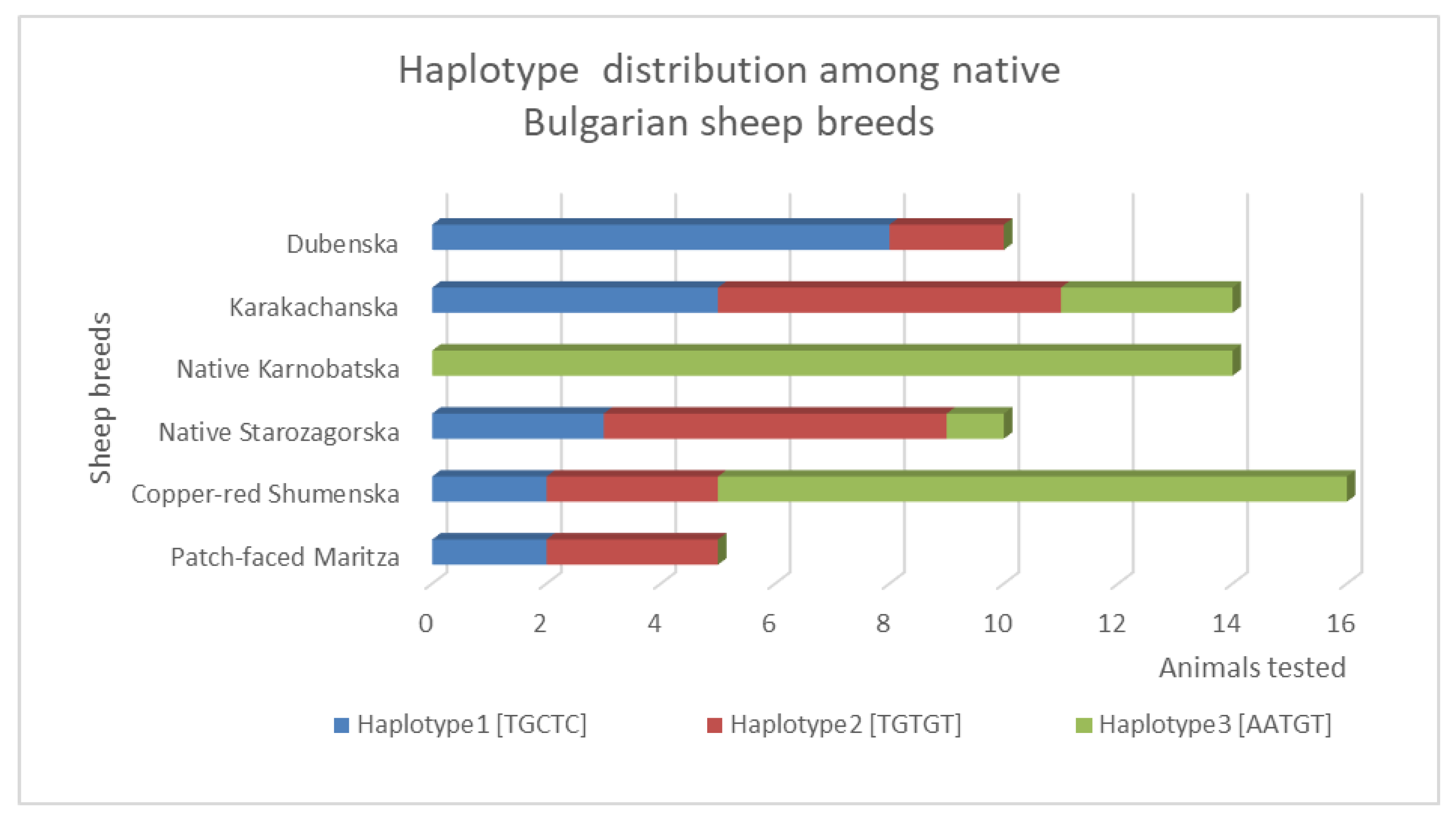

3.2.3. Haplotype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fontanesi, L.; Beretti, F.; Riggio, V.; Dall’Olio, S.; Calascibetta, D.; Russo, V.; Portolano, B. Sequence Characterization of the Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Gene in Sheep with Different Coat Colours and Identification of the Putative e Allele at the Ovine Extension Locus. Small Ruminant Research 2010, 91, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsh, G.; Gunn, T.; He, L.; Schlossman, S.; Duke-Cohan, J. Biochemical and Genetic Studies of Pigment-Type Switching. Pigment Cell Research 2000, 13, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundie, R.S. The Genetics of Colour in Fat-Tailed Sheep: A Review. Trop Anim Health Prod 2011, 43, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.S. Pigmentation and Inheritance: Comparative Genetics of Coat Colour in Mammals. A. G. Searle. Logos Press, London; Academic Press, New York, 1968. Xii + 308 Pp., Illus. $17.50. Science 1968, 161, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseniuk, A.; Ropka-Molik, K.; Rubiś, D.; Smołucha, G. Genetic Background of Coat Colour in Sheep. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2018, 61, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.R.; Li, H.; He, S. Understanding Key Genetic Make-up of Different Coat Colour in Bayinbuluke Sheep through a Comparative Transcriptome Profiling Analysis. Small Ruminant Research 2023, 226, 107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Bao, A.; Hong, W.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Aniwashi, J. Transcriptome Profiling Analysis Reveals Key Genes of Different Coat Color in Sheep Skin. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultman, S.J.; Michaud, E.J.; Woychik, R.P. Molecular Characterization of the Mouse Agouti Locus. Cell 1992, 71, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klungland, H.; Vage, D.I.; Gomez-Raya, L.; Adalsteinsson, S.; Lien, S. The Role of Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (MSH) Receptor in Bovine Coat Color Determination. Mammalian Genome 1995, 6, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollmann, M.M.; Lamoreux, M.L.; Wilson, B.D.; Barsh, G.S. Interaction of Agouti Protein with the Melanocortin 1 Receptor in Vitro and in Vivo. Genes & Development 1998, 12, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Willard, D.; Patel, I.R.; Kadwell, S.; Overton, L.; Kost, T.; Luther, M.; Chen, W.; Woychik, R.P.; Wilkison, W.O.; et al. Agouti Protein Is an Antagonist of the Melanocyte-Stimulating-Hormone Receptor. Nature 1994, 371, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Våge, D.I.; Fleet, M.R.; Ponz, R.; Olsen, R.T.; Monteagudo, L.V.; Tejedor, M.T.; Arruga, M.V.; Gagliardi, R.; Postiglioni, A.; Nattrass, G.S.; et al. Mapping and Characterization of the Dominant Black Colour Locus in Sheep. Pigment Cell Research 2003, 16, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, Y.M.; Fleet, M.R.; Cooper, D.W. The Agouti Gene: A Positional Candidate for Recessive Self-Colour Pigmentation in Australian Merino Sheep. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1999, 50, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraldi, D.; McRae, A.F.; Gratten, J.; Slate, J.; Visscher, P.M.; Pemberton, J.M. Development of a Linkage Map and Mapping of Phenotypic Polymorphisms in a Free-Living Population of Soay Sheep ( Ovis Aries ). Genetics 2006, 173, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauvergne, J.-J.; Raffier, P. Génétique de La Couleur de La Toison Des Races Ovines Françaises Solognote, Bizet et Berrichonne. Genet Sel Evol 1975, 7, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarach, P. Application of Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP-PCR) in the Analysis of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). FBOe 2021, 17, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Våge, D.I.; Klungland, H.; Lu, D.; Cone, R.D. Molecular and Pharmacological Characterization of Dominant Black Coat Color in Sheep. Mammalian Genome 1999, 10, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, L.J.; Álvarez, I.; Arranz, J.J.; Fernández, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Pérez-Pardal, L.; Goyache, F. Differences in the Expression of the ASIP Gene Are Involved in the Recessive Black Coat Colour Pattern in Sheep: Evidence from the Rare Xalda Sheep Breed. Animal Genetics 2008, 39, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanesi, L.; Beretti, F.; Riggio, V.; Dall’Olio, S.; Calascibetta, D.; Russo, V.; Portolano, B. Sequence Characterization of the Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Gene in Sheep with Different Coat Colours and Identification of the Putative e Allele at the Ovine Extension Locus. Small Ruminant Research 2010, 91, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-L.; Fu, D.-L.; Lang, X.; Wang, Y.-T.; Cheng, S.-R.; Fang, S.-L.; Luo, Y.-Z. Mutations in MC1R Gene Determine Black Coat Color Phenotype in Chinese Sheep. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatis, C.; Giannoulis, Th.; Galliopoulou, E.; Billinis, Ch.; Mamuris, Z. Genetic Analysis of Melanocortin 1 Receptor Gene in Endangered Greek Sheep Breeds. Small Ruminant Research 2017, 157, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, B.J.; Whan, V.A. A Gene Duplication Affecting Expression of the Ovine ASIP Gene Is Responsible for White and Black Sheep. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, L.C.G.; Moraes, J.C.F.; Faria, D.A.D.; McManus, C.M.; Nepomuceno, A.R.; Souza, C.J.H.D.; Caetano, A.R.; Paiva, S.R. Genetic Characterization of Coat Color Genes in Brazilian Crioula Sheep from a Conservation Nucleus. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2017, 52, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochus, C.M.; Westberg Sunesson, K.; Jonas, E.; Mikko, S.; Johansson, A.M. Mutations in ASIP and MC1R : Dominant Black and Recessive Black Alleles Segregate in Native Swedish Sheep Populations. Animal Genetics 2019, 50, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D.; Vuchkov, A. Sheep Genetic Resources in Bulgaria with Focus on Breeds with Coloured Wool. GenResJ 2021, 2, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Genetics of the Dog; CABI Books; Ruvinsky, A., Sampson, J., C.A.B., International, Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, 2001; ISBN 978-0-85199-520-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanesi, L.; Dall’Olio, S.; Beretti, F.; Portolano, B.; Russo, V. Coat Colours in the Massese Sheep Breed Are Associated with Mutations in the Agouti Signalling Protein (ASIP) and Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Genes. Animal 2011, 5, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanesi, L.; Beretti, F.; Dall’Olio, S.; Portolano, B.; Matassino, D.; Russo, V. A Melanocortin 1 Receptor ( MC1R ) Gene Polymorphism Is Useful for Authentication of Massese Sheep Dairy Products. Journal of Dairy Research 2011, 78, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-L.; Fu, D.-L.; Lang, X.; Wang, Y.-T.; Cheng, S.-R.; Fang, S.-L.; Luo, Y.-Z. Mutations in MC1R Gene Determine Black Coat Color Phenotype in Chinese Sheep. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanesi, L.; Rustempašić, A.; Brka, M.; Russo, V. Analysis of Polymorphisms in the Agouti Signalling Protein (ASIP) and Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Genes and Association with Coat Colours in Two Pramenka Sheep Types. Small Ruminant Research 2012, 105, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponenberg, P.; Reed, C. Effective Strategies for Local Breed Definition and Conservation. 2016.

- A., T. Allelic and Genotypic Frequencies of ASIP and MC1R Genes in Four West African Sheep Populations. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11. [CrossRef]

- Colour Inheritance in Icelandic Sheep and Relation between Colour, Fertility and Fertilization. 1970.

- Fan, R.; Xie, J.; Bai, J.; Wang, H.; Tian, X.; Bai, R.; Jia, X.; Yang, L.; Song, Y.; Herrid, M.; et al. Skin Transcriptome Profiles Associated with Coat Color in Sheep. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebreselassie, G.; Berihulay, H.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Review on Genomic Regions and Candidate Genes Associated with Economically Important Production and Reproduction Traits in Sheep (Ovies Aries). Animals 2019, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L.L.; Hou, L.; Loftus, S.K.; Pavan, W.J. Spotlight on Spotted Mice: A Review of White Spotting Mouse Mutants and Associated Human Pigmentation Disorders. Pigment Cell Research 2004, 17, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, M. Comparative Analysis of Gene Structure in 5-Flanking Region of Mc1r Gene in Indigenous Sheep Breeds 2024.

- Martin, P.M.; Palhière, I.; Ricard, A.; Tosser-Klopp, G.; Rupp, R. Correction: Genome Wide Association Study Identifies New Loci Associated with Undesired Coat Color Phenotypes in Saanen Goats. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Peng, X.; Lin, J.; He, S.; Li, X.; Han, B.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; et al. Alteration of Sheep Coat Color Pattern by Disruption of ASIP Gene via CRISPR Cas9. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratten, J.; Pilkington, J.G.; Brown, E.A.; Beraldi, D.; Pemberton, J.M.; Slate, J. The Genetic Basis of Recessive Self-Colour Pattern in a Wild Sheep Population. Heredity 2010, 104, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.; Masoudi, A.A.; Amirinia, C.; Emrani, H. Molecular Study of the Extension Locus in Association with Coat Colour Variation of Iranian Indigenous Sheep Breeds. Russ J Genet 2018, 54, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Paiva, S.R.; Louvandini, H.; Landim, A.; Fiorvanti, M.C.S.; Dallago, B.S.; Correa, P.S.; McManus, C. Use of Heat Tolerance Traits in Discriminating between Groups of Sheep in Central Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod 2010, 42, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, M.M.M.; Caetano, A.R.; McManus, C.; Cavalcanti, L.C.G.; Façanha, D.A.E.; Leite, J.H.G.M.; Facó, O.; Paiva, S.R. Application of Genomic Data to Assist a Community-Based Breeding Program: A Preliminary Study of Coat Color Genetics in Morada Nova Sheep. Livestock Science 2016, 190, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, S.; Chandramohan, B.; Pediconi, D.; Nocelli, C.; La Terza, A.; Renieri, C. Interaction between the Melanocortin 1 Receptor ( MC1R ) and Agouti Signalling Protein Genes ( ASIP ), and Their Association with Black and Brown Coat Colour Phenotypes in Peruvian Alpaca. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2020, 19, 1518–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundie, R.S. The Genetics of Colour in Fat-Tailed Sheep: A Review. Trop Anim Health Prod 2011, 43, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, T.; Abebe, A.; Gizaw, S.; Rischkowsky, B.; Bisrat, A.; Haile, A. Coat Color Alterations over the Years and Their Association with Growth Performances in the Menz Sheep Central Nucleus and Community-Based Breeding Programs. Trop Anim Health Prod 2020, 52, 2977–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Introduction to Heritage Breeds, D.P. Sponenberg, J. Beranger and A. Martin Edited by D. Burns & A. Larkin Hansen Storey Publishing, North Adams Published in 2014, Pp. 240 ISBN 978-1-61212-125-3 (Pbk.: Alk. Paper) ISBN 978-1-61212-130-7 (Hardcover: Alk. Paper) e-ISBN 978-1-61212-462-9. Anim. Genet. Resour. 2015, 56, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponenberg, D.P.; Martin, A.; Couch, C.; Beranger, J. Conservation Strategies for Local Breed Biodiversity. Diversity 2019, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer pair name | Forward and reverse primers (5′ –3′ ) | PCRa | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASIP | ex2_del | CAGCAGGTGGGGTTGAGCACGCTGC CTACCTGACTGCCTTCTCTG |

59/25/174 | Fragment analysis (genotyping of the exon 2 deletions) |

| ASIP | Agt17 Agt18 Agt16 |

GTTTCTGCTGGACCTCTTGTTC GTGCCTTGTGAGGTAGAGATGGTGTT CAGCAATGAGGACGTGAGTTT |

58/23/238–242 | Fragment analysis (duplication breakpoint analysis, asymmetric competitive PCR) |

| MC1R | MC1R-5’UTR | GCAACTGCACATCCAGAGAA CGCAGGGAGCAGGAAAGGGTGCTAG |

58/35/202 | PCR-RFLP analysis with AluI (c.-31G>A) |

| MC1R | 3 MC1R | GTGAGCGTCAGCAACGTG ACATAGAGGACGGCCATCAG |

61/35/366 | PCR-RFLP analysis with Tru1I (c.361G>A; p.D121N) |

| MF: MR: |

GAGAGCAAGCACCCTTTCCT GAGAGTCCTGTGATTCCCCT |

60/35/1170 | Complete coding region of MC1R |

| Breeds | Phenotype | n | duplication | deletion | dupl+del | -/- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch-faced Maritza | 76 | 6 | 43 | 11 | 16 | |

| Patch-faced* | 59 | 4 | 35 | 6 | 14 | |

| Fully pigmented** | 10 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Piebald | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | - | |

| White Maritza | 26 | 1 | 12 | 10 | 3 | |

| White | 17 | - | 8 | 6 | 1 | |

| Fully pigmented | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Piebald | 3 | - | - | 2 | 1 | |

| Dubenska | 22 | - | 16 | - | 6 | |

| White | 2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Fully pigmented | 20 | - | 15 | - | 5 | |

| native Starozagorska | 21 | 4 | 17 | - | - | |

| White | 4 | 4 | - | - | - | |

| Fully pigmented | 17 | - | 17 | - | - | |

|

Copper-red Shumenska |

38 | 1 | 37 | - | - | |

| Fully pigmented | 38 | - | - | - | - | |

| native Karnobatska | 33 | 10 | 23 | - | - | |

| Fully pigmented | 33 | - | - | - | - | |

| Karakachanska | 31 | |||||

| Fully pigmented | 31 | - | 11 | - | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).