Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

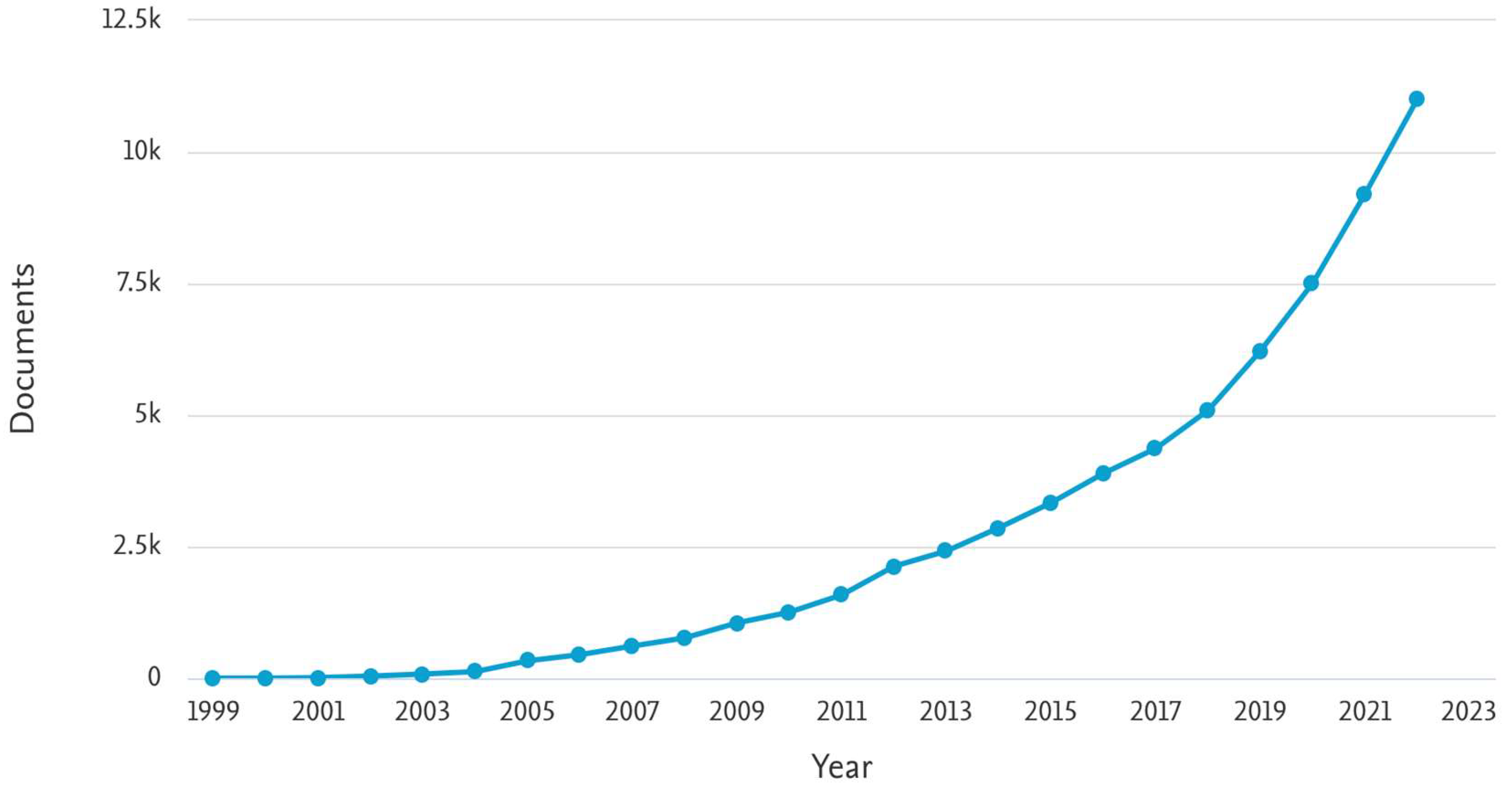

1. Introduction

2. Discussion

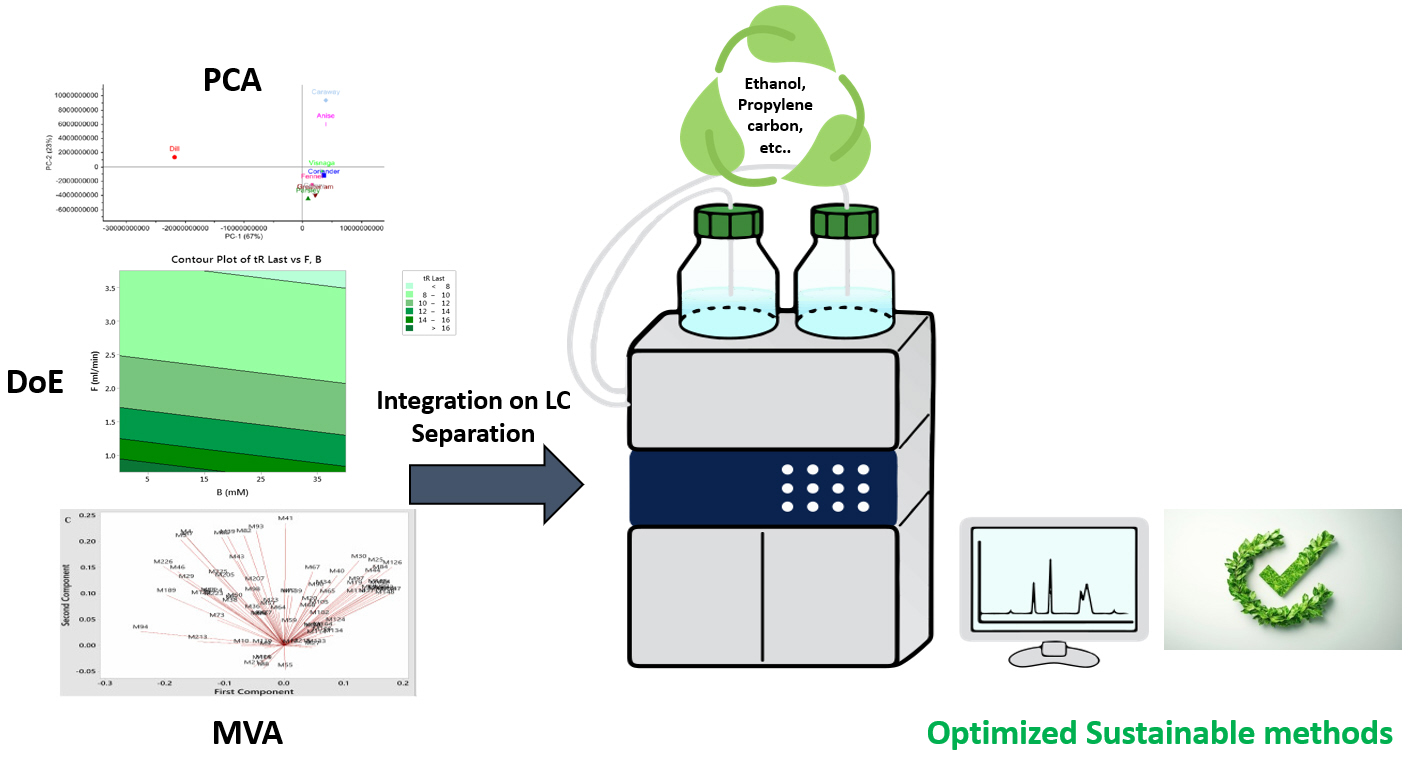

2.1. Multivariant Data Analysis (MDA).

- Can the variables be classified as independent and dependent?

- How many variables are taken to depend on an analysis?

- Are both the dependent and independent variables measured metric or nonmetric?

2.1.1. Partial component analysis (PCA)

2.1.2. Partial least square regression (PLSR)

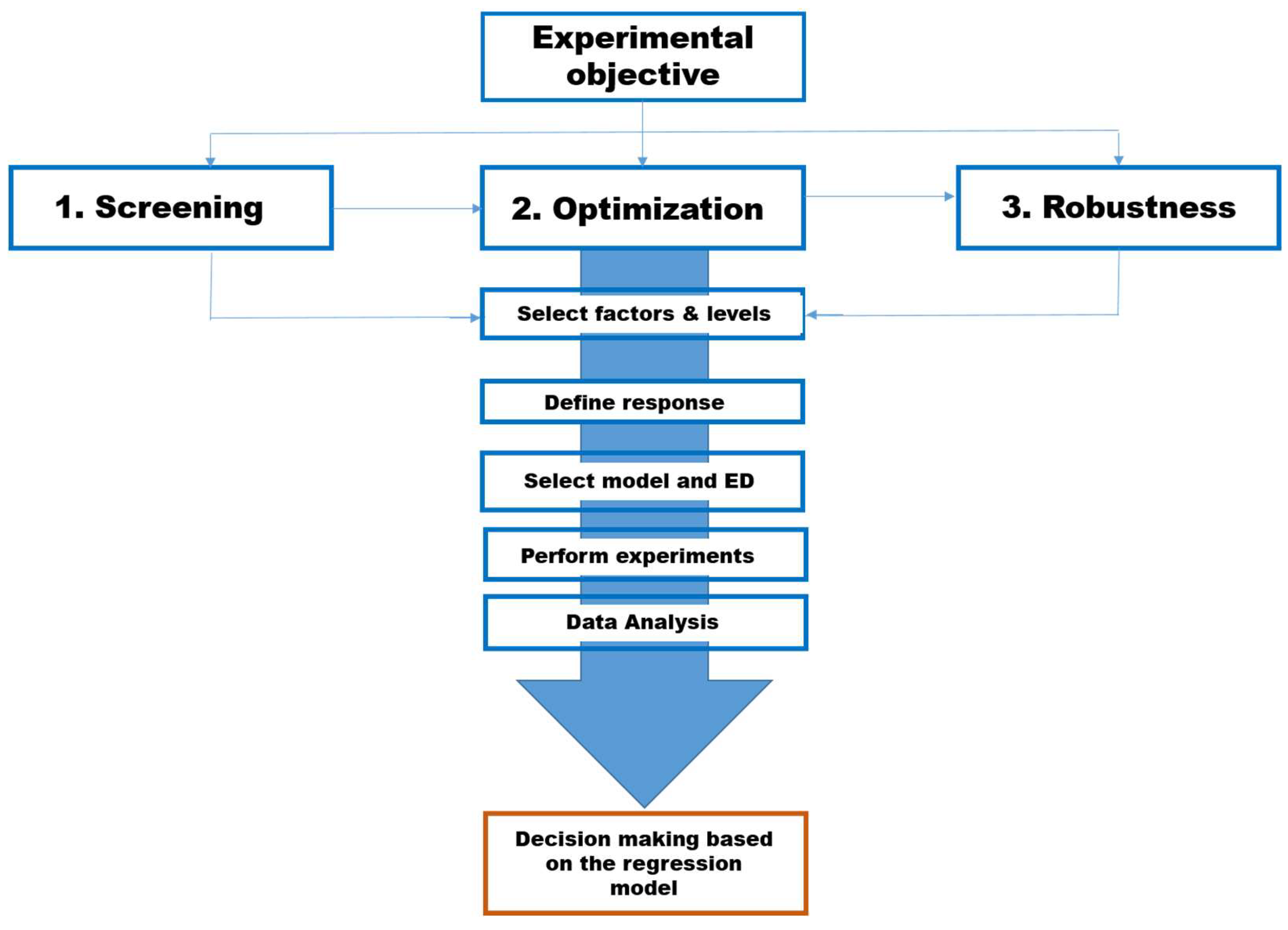

2.2. Design of Experiments (DoE)

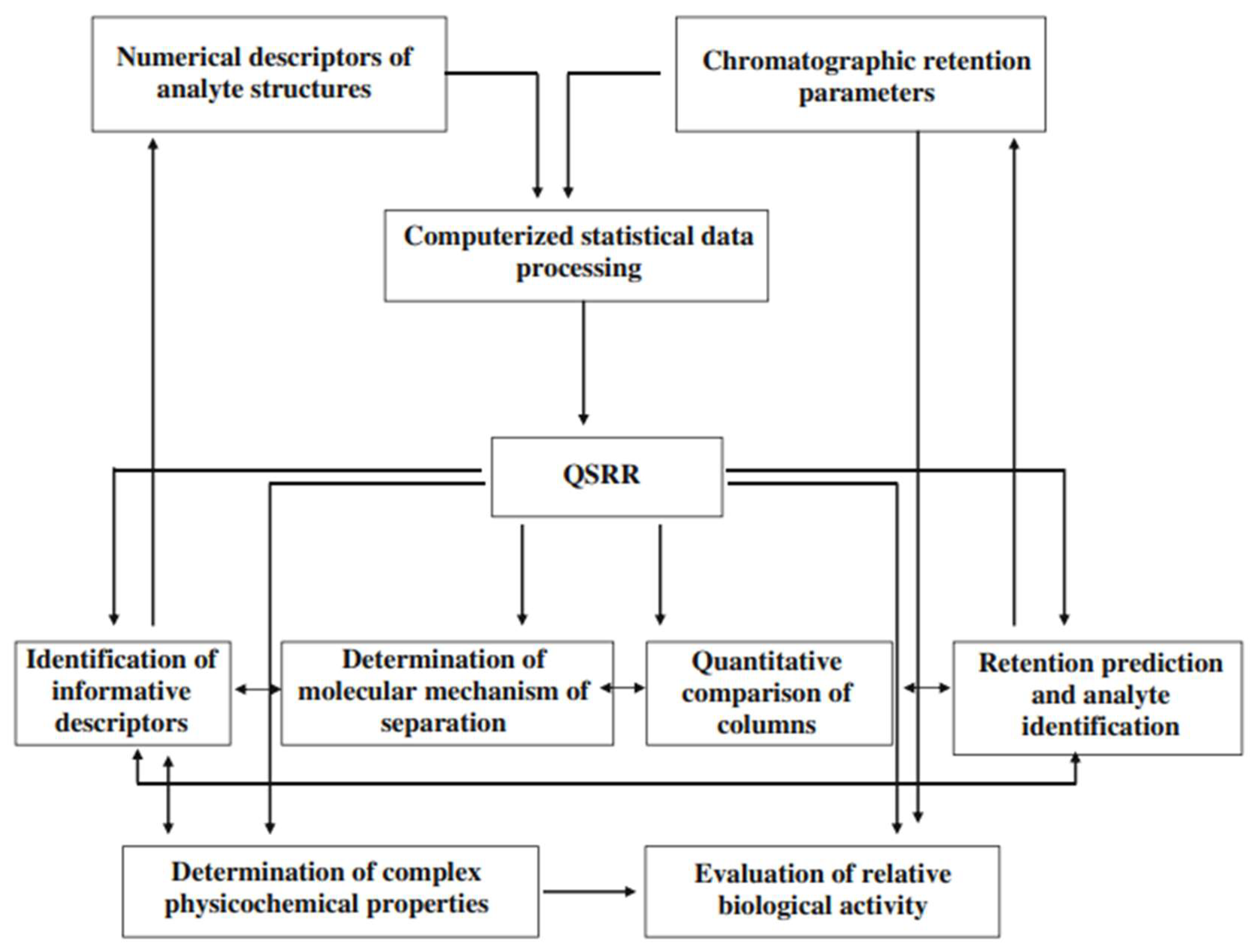

2.3. Retention time prediction

2.1.1. Peak Deconvolution

2.2. Application of chemometrics in sustainabilityof LC pharmaceutical analysis

Chemometrics to aid sustainable APIs analysis :

Chemometrics to aid sustainable impurity profiling:

Chemometrics to aid sustainable bioanalytical applications

Chemometrics to Aid Sustainable Stability Testing

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikolin, B., et al., High perfomance liquid chromatography in pharmaceutical analyses. Bosn J Basic Med Sci, 2004. 4(2): p. 5-9. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.M.M., Overview of Sample Preparation and Chromatographic Methods to Analysis Pharmaceutical Active Compounds in Waters Matrices. 2021. 8(2): p. 16.

- de Jesus Gaffney, V., et al., Occurrence and behaviour of pharmaceutical compounds in a Portuguese wastewater treatment plant: Removal efficiency through conventional treatment processes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017. 24(17): p. 14717-14734. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z., E. Kaleta, and P. Wang, Simultaneous Quantitation of 78 Drugs and Metabolites in Urine with a Dilute-And-Shoot LC–MS-MS Assay. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 2015. 39(5): p. 335-346. [CrossRef]

- Skov, T. and R. Bro, Solving fundamental problems in chromatographic analysis. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2008. 390(1): p. 281-285. [CrossRef]

- El Deeb, S., Enhancing Sustainable Analytical Chemistry in Liquid Chromatography: Guideline for Transferring Classical High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Ultra-High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Methods into Greener, Bluer, and Whiter Methods. 2024. 29(13): p. 3205.

- Roberto de Alvarenga Junior, B. and R. Lajarim Carneiro, Chemometrics Approaches in Forced Degradation Studies of Pharmaceutical Drugs. Molecules, 2019. 24(20). [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, M., V. Panchuk, and D. Kirsanov, Math is greener than chemistry: Assessing green chemistry impact of chemometrics. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2024. 172: p. 117556. [CrossRef]

- International Union of, P. and C. Applied, chemometrics.

- Mousavi, L., et al., Combining chemometrics and the technique for the order of preference by similarity to ideal solution: A new approach to multiple-response optimization of HPLC compared to desirability function. Microchemical Journal, 2020. 155: p. 104752. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P., et al., Chemometric and Design of Experiments-Based Analytical Quality by Design and Green Chemistry Approaches to Multipurpose High-Pressure Liquid Chromatographic Method for Synchronous Estimation of Multiple Fixed-Dose Combinations of Azilsartan Medoxomil. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 2022. 106(1): p. 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Massart, D.L.V., B.G.M.; Buydens, L.M.C.; De Jong, S.; Lewi, P.J. and Smeyers-Verbeke, J. , Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics: Part A. 1997: Elsevier Science.

- Komsta, Ł., Heyden, Y.V., Sherma, J., Chemometrics in chromatography. 1st Edition ed. 2017, Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Mathew, C. and S.J.A.J.o.P.A. Varma, Green Analytical Methods based on Chemometrics and UV spectroscopy for the simultaneous estimation of Empagliflozin and Linagliptin. 2022. 12(1): p. 43-48.

- Rahman, M.A.A., et al., Novel analytical method based on chemometric models applied to UV–Vis spectrophotometric data for simultaneous determination of Etoricoxib and Paracetamol in presence of Paracetamol impurities. BMC Chemistry, 2023. 17(1): p. 176. [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.-W., et al., A green chemometrics-assisted fluorimetric detection method for the direct and simultaneous determination of six polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in oil-field wastewaters. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2018. 200: p. 93-101. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., H. Shakeel, and R. Sharma, Overview of chemometrics in forensic toxicology. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 2023. 13(1): p. 53. [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, R., A. Sayago, and Á. Fernández-Recamales, An Overview on the Application of Chemometrics Tools in Food Authenticity and Traceability. Foods, 2022. 11: p. 3940. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.M., C.G. Hussain, and R. Keçili, White analytical chemistry approaches for analytical and bioanalytical techniques: Applications and challenges. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2023. 159: p. 116905. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.T., H.M.T. Nguyen, and V.D. Hoang, Recent applications of analytical quality-by-design methodology for chromatographic analysis: A review. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2024. 254: p. 105243. [CrossRef]

- Cela, R., et al., Chemometric-assisted method development in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Journal of chromatography. A, 2012. 1287. [CrossRef]

- Olkin, I. and A.R. Sampson, Multivariate Analysis: Overview, in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes, Editors. 2001, Pergamon: Oxford. p. 10240-10247.

- Bezerra, M.A., et al., Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta, 2008. 76(5): p. 965-977. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.D., Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography, Third Edition. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 2011. 22(1): p. 196-196. [CrossRef]

- Tome, T., et al., Development and Optimization of Liquid Chromatography Analytical Methods by Using AQbD Principles: Overview and Recent Advances. Organic Process Research & Development, 2019. 23(9): p. 1784-1802. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A. and F. Ghaemi, Solid-phase extraction of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in human plasma and water samples using sol–gel-based metal-organic framework coating. Journal of Chromatography A, 2021. 1648: p. 462168. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.E., et al., A Comparative Metabolomics Approach Reveals Early Biomarkers for Metabolic Response to Acute Myocardial Infarction. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 36359. [CrossRef]

- Beckman, E.J., Supercritical and near-critical CO2 in green chemical synthesis and processing. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 2004. 28(2): p. 121-191. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.D., H Principles of Green Chemistry. In Green Organic Reactions. 1 ed. Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials, ed. S.S. Gopinathan Anilkumar. 2021: Springer Singapore. 15–32.

- Prajapati, P., et al., Risk Assessment-Based Enhanced Analytical Quality-by-Design Approach to Eco-Friendly and Economical Multicomponent Spectrophotometric Methods for Simultaneous Estimation of Montelukast Sodium and Bilastine. J AOAC Int, 2021. 104(5): p. 1453-1463. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P., et al., Implementation of White Analytical Chemistry–Assisted Analytical Quality by Design Approach to Green Liquid Chromatographic Method for Concomitant Analysis of Anti-Hypertensive Drugs in Human Plasma. Journal of Chromatographic Science, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P., et al., Application of Principal Component Analysis and DoE-Driven Green Analytical Chemistry Concept to Liquid Chromatographic Method for Estimation of Co-formulated Anti-Hypertensive Drugs. J AOAC Int, 2023. 106(4): p. 1087-1097. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P., et al., Multivariate Analysis and Response Surface Modeling to Green Analytical Chemistry-Based RP-HPLC-PDA Method for Chromatographic Analysis of Vildagliptin and Remogliflozin Etabonate. J AOAC Int, 2023. 106(3): p. 601-612. [CrossRef]

- Dien, J., D.J. Beal, and P. Berg, Optimizing principal components analysis of event-related potentials: matrix type, factor loading weighting, extraction, and rotations. Clin Neurophysiol, 2005. 116(8): p. 1808-25. [CrossRef]

- Amin, K.F.M., R.H. Obaydo, and A.M. Abdullah, Eco-friendly chemometric analysis: Sustainable quantification of five pharmaceutical compounds in bulk, tablets, and spiked human plasma. Results in Chemistry, 2024. 11: p. 101761. [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H., Partial least squares regression and projection on latent structure regression (PLS Regression). 2010. 2(1): p. 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Nurani, L.H., et al., Chemometrics-Assisted UV-Vis Spectrophotometry for Quality Control of Pharmaceuticals: A Review. 2023, 2023. 23(2): p. 26 %J Indonesian Journal of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- P.B, P., et al., Design of Experiments (DoE) - Based Enhanced Quality by Design Approach to Hydrolytic Degradation Kinetic Study of Capecitabine by Eco-friendly Stability Indicating UV-Visible Spectrophotometry. American Journal of PharmTech Research, 2020. 10: p. 115-133. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.N. and C.S. Kothari, Multivariate Approaches for Simultaneous Determination of Avanafil and Dapoxetine by UV Chemometrics and HPLC-QbD in Binary Mixtures and Pharmaceutical Product. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 2019. 99(3): p. 649-663. [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.V.V.S.S., U.R. Mallu, and H.R. Bapatu, Analytical Quality by Design Approach to Test Method Development and Validation in Drug Substance Manufacturing. 2015. 2015(1): p. 435129. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency ICH Guideline Q14 on Analytical Procedure Development Step 2b. . 2022 [cited 2022 [(accessed on 31 March 2022)].]; Available from: Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-guideline-q14-analytical-procedure-development-step-2b_en.pdf,.

- Park, G., et al., Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) Approach to the Development of Analytical Procedures for Medicinal Plants. 2022. 11(21): p. 2960.

- Lundstedt, T., et al., Experimental design and optimization. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 1998. 42(1): p. 3-40. [CrossRef]

- Aboushady, D., M.K. Parr, and R.S. Hanafi, Quality-by-Design Is a Tool for Quality Assurance in the Assessment of Enantioseparation of a Model Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient. 2020. 13(11): p. 364.

- Gangnus, T. and B.B. Burckhardt, Improving sensitivity for the targeted LC-MS/MS analysis of the peptide bradykinin using a design of experiments approach. Talanta, 2020. 218: p. 121134. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H., et al., Time-Saving Design of Experiment Protocol for Optimization of LC-MS Data Processing in Metabolomic Approaches. Analytical Chemistry, 2013. 85(15): p. 7109-7116. [CrossRef]

- Aboushady, D., R.S. Hanafi, and M.K. Parr, Quality by design approach for enantioseparation of terbutaline and its sulfate conjugate metabolite for bioanalytical application using supercritical fluid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 2022. 1676: p. 463285. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, P. and S. Janagap, Doehlert uniform shell designs and chromatography. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, 2012. 910: p. 14-21. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.L., McLean, R.A. , Design of Experiments: A Realistic Approach. 1st Edition ed. 1974, Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Thorsteinsdóttir, U.A. and M. Thorsteinsdóttir, Design of experiments for development and optimization of a liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry bioanalytical assay. 2021. 56(9): p. e4727. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.A., et al., An innovative approach for planning and execution of pre-experimental runs for Design of Experiments. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 2016. 22(3): p. 155-161. [CrossRef]

- Székely, G., et al., Experimental design for the optimization and robustness testing of a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the trace analysis of the potentially genotoxic 1,3-diisopropylurea. 2014. 6(9): p. 898-908. [CrossRef]

- D. M., B. and B. Narasimha Murthy, Advanced Designs of Experiment Approach to Clinical and Medical Research, in Design of Experiments and Advanced Statistical Techniques in Clinical Research. 2020, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p. 77-131.

- Easterling, R.G., Fundamentals of Statistical Experimental Design and Analysis. 2015: Wiley.

- Fontdecaba, S., P. Grima, and X. Tort-Martorell, Analyzing DOE With Statistical Software Packages: Controversies and Proposals. The American Statistician, 2014. 68(3): p. 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Ganorkar, S.B. and A.A. Shirkhedkar, Design of experiments in liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of pharmaceuticals: analytics, applications, implications and future prospects. 2017. 36(3). [CrossRef]

- Székely, G., et al., Design of experiments as a tool for LC–MS/MS method development for the trace analysis of the potentially genotoxic 4-dimethylaminopyridine impurity in glucocorticoids. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2012. 70: p. 251-258. [CrossRef]

- Alves, C., et al., Analysis of tricyclic antidepressant drugs in plasma by means of solid-phase microextraction-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. 2007. 42(10): p. 1342-1347. [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, D.B., Experimental design in chromatography: A tutorial review. Journal of Chromatography B, 2012. 910: p. 2-13. [CrossRef]

- Zappi, A., et al., Extracting Information and Enhancing the Quality of Separation Data: A Review on Chemometrics-Assisted Analysis of Volatile, Soluble and Colloidal Samples. 2023. 11(1): p. 45.

- Henderson, R.K., et al., Expanding GSK's solvent selection guide – embedding sustainability into solvent selection starting at medicinal chemistry. Green Chemistry, 2011. 13(4): p. 854-862. [CrossRef]

- Jurjeva, J. and M. Koel, Implementing greening into design in analytical chemistry. Talanta Open, 2022. 6: p. 100136. [CrossRef]

- Funari, C.S., et al., Acetone as a greener alternative to acetonitrile in liquid chromatographic fingerprinting. 2015. 38(9): p. 1458-1465. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A., A.F. Roig-Navarro, and O.J. Pozo, Capabilities of microbore columns coupled to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry in speciation of arsenic and selenium. Journal of Chromatography A, 2008. 1202(2): p. 132-137. [CrossRef]

- Płotka, J., et al., Green chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 2013. 1307: p. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.R. and N. Adhikari, An Overview on Common Organic Solvents and Their Toxicity. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, 2019. 28(3): p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Yabré, M., et al., Greening Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography Methods Using Alternative Solvents for Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2018. 23(5): p. 1065.

- Gałuszka, A., Z. Migaszewski, and J. Namieśnik, The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013. 50: p. 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.L.Y., R.L. Smith, and M. Poliakoff, Principles of green chemistry: PRODUCTIVELY. Green Chemistry, 2005. 7(11): p. 761-762. [CrossRef]

- Nassef, H.M., et al., Greens assessment of RP-UPLC method for estimating Triamcinolone Acetonide and its degraded products compared to Box-Behnken and Six Sigma designs. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, 2024. 17(1): p. 2301315. [CrossRef]

- Ferey, L., et al., UHPLC method for multiproduct pharmaceutical analysis by Quality-by-Design. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2018. 148: p. 361-368. [CrossRef]

- Yabré, M., et al., Development of a green HPLC method for the analysis of artesunate and amodiaquine impurities using Quality by Design. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2020. 190: p. 113507. [CrossRef]

- Kokilambigai, K.S. and K.S. Lakshmi, Analytical quality by design assisted RP-HPLC method for quantifying atorvastatin with green analytical chemistry perspective. Journal of Chromatography Open, 2022. 2: p. 100052. [CrossRef]

- Perumal, D.D., M. Krishnan, and K.S. Lakshmi, Eco-friendly based stability-indicating RP-HPLC technique for the determination of escitalopram and etizolam by employing QbD approach. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, 2022. 15(3): p. 671-682. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moety, E.M., et al., A combined approach of green chemistry and Quality-by-Design for sustainable and robust analysis of two newly introduced pharmaceutical formulations treating benign prostate hyperplasia. Microchemical Journal, 2021. 160: p. 105711. [CrossRef]

- Ghonim, R., et al., Environmentally benign liquid chromatographic method for concurrent estimation of four antihistaminic drugs applying factorial design approach. BMC Chemistry, 2024. 18(1): p. 26. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T., et al., Implementation of analytical quality-by-design and green analytical chemistry approaches for the development of robust and ecofriendly UHPLC analytical method for quantification of chrysin. 2020. 3(9): p. 384-398. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.M., Green, environment-friendly, analytical tools give insights in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2015. 66: p. 176-192. [CrossRef]

- Tache, F., et al., Greening pharmaceutical applications of liquid chromatography through using propylene carbonate-ethanol mixtures instead of acetonitrile as organic modifier in the mobile phases. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2013. 75: p. 230-8. [CrossRef]

- Natalija, N., et al., Green Strategies toward Eco-Friendly HPLC Methods in Pharma Analysis, in High Performance Liquid Chromatography, N. Oscar, et al., Editors. 2023, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 5.

- Fayaz, T.K.S., et al., Propylene carbonate as an ecofriendly solvent: Stability studies of Ripretinib in RPHPLC and sustainable evaluation using advanced tools. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2024. 37: p. 101355. [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A., T. Górecki, and M.A. Omar, Green approaches to comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography (LC × LC). Journal of Chromatography Open, 2022. 2: p. 100046. [CrossRef]

- Atapattu, S.N., Applications and retention properties of alternative organic mobile phase modifiers in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography Open, 2024. 5: p. 100135. [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, P.C.C., et al., The Development of a Rapid, Cost-Effective, and Green Analytical Method for Mercury Speciation. 2024. 12(6): p. 424.

- Imam, M.S. and M.M. Abdelrahman, How environmentally friendly is the analytical process? A paradigm overview of ten greenness assessment metric approaches for analytical methods. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 2023. 38: p. e00202. [CrossRef]

- Spietelun, A., et al., Recent developments and future trends in solid phase microextraction techniques towards green analytical chemistry. Journal of Chromatography A, 2013. 1321: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.S., et al., Analytical tools for greenness assessment of chromatographic approaches: Application to pharmaceutical combinations of Indapamide, Perindopril and Amlodipine. Microchemical Journal, 2020. 159: p. 105557. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.C., et al., Box-Behnken design: An alternative for the optimization of analytical methods. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2007. 597(2): p. 179-186. [CrossRef]

- Pezzatti, J., et al., Choosing an Optimal Sample Preparation in Caulobacter crescentus for Untargeted Metabolomics Approaches. 2019. 9(10): p. 193.

- Stalikas, C., et al., Developments on chemometric approaches to optimize and evaluate microextraction. Journal of Chromatography A, 2009. 1216(2): p. 175-189. [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.J., et al., Greening analytical chromatography. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2010. 29(7): p. 667-680. [CrossRef]

- Asadollahzadeh, M., et al., Response surface methodology based on central composite design as a chemometric tool for optimization of dispersive-solidification liquid–liquid microextraction for speciation of inorganic arsenic in environmental water samples. Talanta, 2014. 123: p. 25-31. [CrossRef]

- Marrubini, G., et al., Experimental designs for solid-phase microextraction method development in bioanalysis: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2020. 1119: p. 77-100. [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, S. and S. Cinti, How Can Chemometrics Support the Development of Point of Need Devices? Analytical Chemistry, 2021. 93(5): p. 2713-2722. [CrossRef]

- Jovana, K., et al., QSRR Approach: Application to Retention Mechanism in Liquid Chromatography, in Novel Aspects of Gas Chromatography and Chemometrics, C.M. Serban, H. Vu Dang, and D. Victor, Editors. 2022, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 7.

- Manzon, D., et al., Quality by Design: Comparison of Design Space construction methods in the case of Design of Experiments. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2020. 200: p. 104002. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T., et al., Succinimidyl (3-[(benzyloxy)carbonyl]-5-oxo-1,3-oxazolidin-4-yl)acetate on a triazole-bonded phase for the separation of dl-amino-acid enantiomers and the mass-spectrometric determination of chiral amino acids in rat plasma. Journal of Chromatography A, 2019. 1585: p. 131-137. [CrossRef]

- Andries, J.P.M., M. Goodarzi, and Y.V. Heyden, Improvement of quantitative structure–retention relationship models for chromatographic retention prediction of peptides applying individual local partial least squares models. Talanta, 2020. 219: p. 121266. [CrossRef]

- Kaliszan, R., QSRR: Quantitative Structure-(Chromatographic) Retention Relationships. Chemical Reviews, 2007. 107(7): p. 3212-3246. [CrossRef]

- Kaliszan, R. and T. Bączek, QSAR in Chromatography: Quantitative Structure–Retention Relationships (QSRRs), in Recent Advances in QSAR Studies: Methods and Applications, T. Puzyn, J. Leszczynski, and M.T. Cronin, Editors. 2010, Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht. p. 223-259.

- Katritzky, A.R., V.S. Lobanov, and M. Karelson, QSPR: the correlation and quantitative prediction of chemical and physical properties from structure. Chemical Society Reviews, 1995. 24(4): p. 279-287. [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C. and T. Fujita, p-σ-π Analysis. A Method for the Correlation of Biological Activity and Chemical Structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1964. 86(8): p. 1616-1626. [CrossRef]

- Hanai, T., Chromatography in silico, basic concept in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2005. 382(3): p. 708-717. [CrossRef]

- Lippa, K.A., L.C. Sander, and R.D. Mountain, Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Alkylsilane Stationary-Phase Order and Disorder. 1. Effects of Surface Coverage and Bonding Chemistry. Analytical Chemistry, 2005. 77(24): p. 7852-7861. [CrossRef]

- Kaliszan, R., P. Wiczling, and M.J. Markuszewski, pH Gradient Reversed-Phase HPLC. Analytical Chemistry, 2004. 76(3): p. 749-760. [CrossRef]

- Meek, J.L., Prediction of peptide retention times in high-pressure liquid chromatography on the basis of amino acid composition. 1980. 77(3): p. 1632-1636. [CrossRef]

- Palmblad, M., et al., Prediction of Chromatographic Retention and Protein Identification in Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry, 2002. 74(22): p. 5826-5830. [CrossRef]

- Petritis, K., et al., Use of Artificial Neural Networks for the Accurate Prediction of Peptide Liquid Chromatography Elution Times in Proteome Analyses. Analytical Chemistry, 2003. 75(5): p. 1039-1048. [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L., et al., Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014. 48(4): p. 2097-2098. [CrossRef]

- Bade, R., et al., Critical evaluation of a simple retention time predictor based on LogKow as a complementary tool in the identification of emerging contaminants in water. Talanta, 2015. 139: p. 143-149. [CrossRef]

- Bade, R., et al., LC-HRMS suspect screening to show spatial patterns of New Psychoactive Substances use in Australia. Science of The Total Environment, 2019. 650: p. 2181-2187. [CrossRef]

- McEachran, A.D., et al., A comparison of three liquid chromatography (LC) retention time prediction models. Talanta, 2018. 182: p. 371-379. [CrossRef]

- Noreldeen, H.A.A., et al., Quantitative structure-retention relationships model for retention time prediction of veterinary drugs in food matrixes. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 2018. 434: p. 172-178. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, I., et al., Identifying unknown metabolites using NMR-based metabolic profiling techniques. Nature Protocols, 2020. 15(8): p. 2538-2567. [CrossRef]

- He, B., et al., Analytical techniques for biomass-restricted metabolomics: An overview of the state-of-the-art. Microchemical Journal, 2021. 171: p. 106794. [CrossRef]

- Letertre, M.P.M., G. Dervilly, and P. Giraudeau, Combined Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry Approaches for Metabolomics. Analytical Chemistry, 2021. 93(1): p. 500-518. [CrossRef]

- Goryński, K., et al., Quantitative structure–retention relationships models for prediction of high performance liquid chromatography retention time of small molecules: Endogenous metabolites and banned compounds. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2013. 797: p. 13-19. [CrossRef]

- Jinno, K. and K.D. Bartle, A computer assisted chromatography system: Hüthig, Heidelberg, 1990 (ISBN 3-7785-1487-0). viii + 271 pp. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1991. 243: p. 321-322. [CrossRef]

- Kaliszan, R., Retention data from affinity high-performance liquid chromatography in view of chemometrics. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications, 1998. 715(1): p. 229-244. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.M., R. Wietecha-Posłuszny, and J. Pawliszyn, White Analytical Chemistry: An approach to reconcile the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and functionality. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2021. 138: p. 116223. [CrossRef]

- Tache, F., et al., Estimation of the lipophilic character of flavonoids from the retention behavior in reversed phase liquid chromatography on different stationary phases: A comparative study. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2012. 57: p. 82-93. [CrossRef]

- Stella, C., et al., Silica and other materials as supports in liquid chromatography. Chromatographic tests and their importance for evaluating these supports. Part II. Chromatographia, 2001. 53(1): p. S132-S140. [CrossRef]

- Taraji, M., et al., Rapid Method Development in Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography for Pharmaceutical Analysis Using a Combination of Quantitative Structure–Retention Relationships and Design of Experiments. Analytical Chemistry, 2017. 89(3): p. 1870-1878. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M. and J.C. Giddings, Statistical theory of component overlap in multicomponent chromatograms. Analytical Chemistry, 1983. 55(3): p. 418-424. [CrossRef]

- Vanderheyden, Y., K. Broeckhoven, and G. Desmet, Peak deconvolution to correctly assess the band broadening of chromatographic columns. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016. 1465: p. 126-142. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.F., et al., Power Law Approach as a Convenient Protocol for Improving Peak Shapes and Recovering Areas from Partially Resolved Peaks. Chromatographia, 2019. 82(1): p. 211-220. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.C., et al., Separations at the Speed of Sensors. Analytical Chemistry, 2018. 90(5): p. 3349-3356. [CrossRef]

- Castledine, J.B. and A.F. Fell, Strategies for peak-purity assessment in liquid chromatography. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 1993. 11(1): p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.V., et al. Automatic Lane and Band Detection in Images of Thin Layer Chromatography. in Image Analysis and Recognition. 2004. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Chang, Y.-Y., et al., Comparison of three chemometric methods for processing HPLC-DAD data with time shifts: Simultaneous determination of ten molecular targeted anti-tumor drugs in different biological samples. Talanta, 2021. 224: p. 121798. [CrossRef]

- Komsta, Ł., Y. Vander Heyden, and J. Sherma, Chemometrics in Chromatography. 2018: CRC Press.

- Bukkapatnam, V., M. Annapurna, and K. Routhu, Experimental Design Methodology for Simultaneous Determination of Anti-Diabetic Drugs by Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatographic Method. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2021. 83. [CrossRef]

- Gigovska, M., et al., Chemometrically assisted optimization, development and validation of UPLC method for the analysis of simvastatin. Macedonian Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2018. 64: p. 25-38. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R., S. Belemkar, and C. Bonde, A Stepwise Strategy Employing Automated Screening for Reversed-Phase Chromatographic Separation of Itraconazole and Its Impurities. Chromatographia, 2019. 82(12): p. 1767-1775. [CrossRef]

- Nath, D. and B. Sharma, Impurity Profiling-A Significant Approach in Pharmaceuticals. Current Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2019. 15(7): p. 669-680. [CrossRef]

- Attimarad, M., et al., Mathematically Processed UV Spectroscopic Method for Quantification of Chlorthalidone and Azelnidipine in Bulk and Formulation: Evaluation of Greenness and Whiteness. 2022. 2022(1): p. 4965138. [CrossRef]

- Elsonbaty, A., et al., Analysis of quinary therapy targeting multiple cardiovascular diseases using UV spectrophotometry and chemometric tools. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2020. 238: p. 118415. [CrossRef]

- Attia, K.A.M., et al., A sustainable data processing approach using ultraviolet-spectroscopy as a powerful spectral resolution tool for simultaneously estimating newly approved eye solution in the presence of extremely carcinogenic impurity aided with various greenness and whiteness assessment perspectives: Application to aqueous humor. 2023. 47(5): p. 17475198231195811. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A., et al., Advanced chemometric methods as powerful tools for impurity profiling of drug substances and drug products: Application on bisoprolol and perindopril binary mixture. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2022. 267: p. 120576. [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, Y.A., et al., Green Chemometric Determination of Cefotaxime Sodium in the Presence of Its Degradation Impurities Using Different Multivariate Data Processing Tools; GAPI and AGREE Greenness Evaluation. 2023. 28(5): p. 2187.

- Halim, M.K., O.M. Badran, and A.E.F. Abbas, Greenness, blueness and whiteness evaluated-chemometric approach enhanced by Latin hypercube technique for the analysis of lidocaine, diclofenac and carcinogenic impurity 2,6-dimethylaniline. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2024. 38: p. 101463. [CrossRef]

- Gathungu, R.M., et al., The integration of LC-MS and NMR for the analysis of low molecular weight trace analytes in complex matrices. Mass Spectrom Rev, 2020. 39(1-2): p. 35-54. [CrossRef]

- Skibiński, R. and J. Trawiński, Application of an Untargeted Chemometric Strategy in the Impurity Profiling of Pharmaceuticals: An Example of Amisulpride. Journal of Chromatographic Science, 2016. 55(3): p. 309-315. [CrossRef]

- Plumb, R.S., et al., A Rapid Simple Approach to Screening Pharmaceutical Products Using Ultra-Performance LC Coupled to Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry and Pattern Recognition. Journal of Chromatographic Science, 2008. 46(3): p. 193-198. [CrossRef]

- KATAKAM, P., et al., An Experimental Design Approach for Impurity Profiling of Valacyclovir-Related Products by RP-HPLC. 2014. 82(3): p. 617-630.

- Elkhoudary, M.M., A.A.R. Salam, and M.G. Hadad, Robustness Testing in HPLC Analysis of Clarithromycin, Norfloxacin, Doxycycline, Tinidazole and Omeprazole in Pharmaceutical Dosage forms Using Experimental Design. Current Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2014. 10(1): p. 58-70. [CrossRef]

- Boussès, C., et al., Using an innovative combination of quality-by-design and green analytical chemistry approaches for the development of a stability indicating UHPLC method in pharmaceutical products. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2015. 115: p. 114-122. [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, K., Quantitative impurity profiling by principal component analysis of high-performance liquid chromatography–diode array detection data. Journal of Chromatography A, 2006. 1108(1): p. 50-67. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, E.B., Two green chromatographic methods for the quantification of tamsulosin and solifenacin along with four of their impurities. 2022. 45(7): p. 1305-1316. [CrossRef]

- Edrees, F.H., et al., Experimentally designed chromatographic method for the simultaneous analysis of dimenhydrinate, cinnarizine and their toxic impurities. RSC Advances, 2021. 11(3): p. 1450-1460. [CrossRef]

- Arase, S., et al., Intelligent peak deconvolution through in-depth study of the data matrix from liquid chromatography coupled with a photo-diode array detector applied to pharmaceutical analysis. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016. 1469: p. 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.L. and G.M. Escandar, Liquid chromatography with diode array detection and multivariate curve resolution for the selective and sensitive quantification of estrogens in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2014. 835: p. 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska, K., M. Bystrzanowska, and M. Tobiszewski, Chemometrics approaches to green analytical chemistry procedure development. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 2021. 30: p. 100498. [CrossRef]

- Narenderan, S.T., S.N. Meyyanathan, and V.V.S.R. Karri, Experimental design in pesticide extraction methods: A review. Food Chemistry, 2019. 289: p. 384-395. [CrossRef]

- Dejaegher, B. and Y.V. Heyden, Experimental designs and their recent advances in set-up, data interpretation, and analytical applications. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2011. 56(2): p. 141-58. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.N., et al., Correction to: Comparative Study of the UV-Chemometrics, Ratio Spectra Derivative and HPLC-QbD Methods for the Simultaneous Estimation of Carisoprodol, Paracetamol and Caffeine in Its Triple Combination Formulation CARISOMA. Chromatographia, 2021. 84(3): p. 313-313. [CrossRef]

- Bystrzanowska, M. and M. Tobiszewski, Chemometrics for Selection, Prediction, and Classification of Sustainable Solutions for Green Chemistry—A Review. 2020. 12(12): p. 2055.

- Roberto de Alvarenga Junior, B. and R. Lajarim Carneiro, Chemometrics Approaches in Forced Degradation Studies of Pharmaceutical Drugs. 2019. 24(20): p. 3804.

- Huynh-Ba, K. and M. Dong, Stability Studies and Testing of Pharmaceuticals: An Overview. Lc Gc North America, 2020. 38: p. 325.

- Lafossas, C., F. Benoit-Marquié, and J.C. Garrigues, Analysis of the retention of tetracyclines on reversed-phase columns: Chemometrics, design of experiments and quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) study for interpretation and optimization. Talanta, 2019. 198: p. 550-559. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S., et al., Bi2O3/ZnO nanocomposite: Synthesis, characterizations and its application in electrochemical detection of balofloxacin as an anti-biotic drug. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2021. 11(1): p. 57-67. [CrossRef]

- Godoy, J.L., J.R. Vega, and J.L. Marchetti, Relationships between PCA and PLS-regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2014. 130: p. 182-191. [CrossRef]

- Golubović, J.B., et al., Quantitative structure retention relationship modeling in liquid chromatography method for separation of candesartan cilexetil and its degradation products. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2015. 140: p. 92-101. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., et al., Determination of the paracetamol degradation process with online UV spectroscopic and multivariate curve resolution-alternating least squares methods: comparative validation by HPLC. Analytical Methods, 2013. 5(19): p. 5286-5293. [CrossRef]

- Attia, K.A., et al., Stability indicating methods for the analysis of cefprozil in the presence of its alkaline induced degradation product. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2016. 159: p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Marín-García, M., et al., Investigation of the photodegradation profile of tamoxifen using spectroscopic and chromatographic analysis and multivariate curve resolution. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2018. 174: p. 128-141. [CrossRef]

| Types | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional descriptors | They are derived from the molecular formula and describe the composition and connectivity of atoms within a molecule without considering its 3D structure | 1-Molecular weight 2-count of atoms and bonds 3-counts of rings |

| Topological descriptors | These descriptors capture information about the molecule's topology and how the atoms are connected to one another without considering their 3D spatial arrangement | 1- Wiener Index: 2- Kier and Hall Indices 3- Randic Index (Connectivity Index) |

| Electrostatic descriptors | They describe the distribution of electronic charge within a molecule. | 1-Partial Atomic Charges 2-polarity indices 3- charged partial surface area |

| Geometrical descriptors | These descriptors capture the 3D geometry of a molecule, which is critical for understanding its interactions with other molecules | 1-Molecular volume 2-Solvent-accessible molecular surface 3-Principale moment of intera |

| Quantum-chemical descriptors | They are derived from quantum chemical calculations. And provide information about internal electronic property which are crucial for understanding its reactivity, stability, and interactions with other molecules or environments | 1- HOMO and LUMO Energies 2- Dipole Moment 3- Electron Density Distribution |

| Chemometric Tool | Application | Variables/Factors | Experimental Design | Key Results/Findings | Example Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DoE (Design of Experiments) | Used for systematic method optimization by exploring the effects of multiple factors on outputs | Variables: solvent composition, temperature, pH, etc. | Fractional factorial design or other experimental designs | Identifies critical factors affecting chromatographic separation and drug stability | Example: DoE was applied to optimize RP-HPLC conditions for degradation products of candesartan cilexetil [163]. |

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Dimensionality reduction, used to identify key components in complex datasets | PCA uses components derived from spectral or chromatographic data | No specific design; based on matrix decomposition of the data set | Helps in identifying major components contributing to variability, removing noise from data | Example: PCA identified four components in alkaline degradation of paracetamol [164]. |

| PLS (Partial Least Squares) | Correlates input variables (X) with responses (Y) to predict concentration profiles | Variables: UV-VIS spectra, MS data, chromatographic factors | PLS regression is used to maximize the covariance between predictor variables and response variables | Provides concentration profiles and spectral profiles in the context of forced degradation | Example: PLS was used for correlating degradation profiles of Cefprozil upon Basic hydrolysis [165] |

| MCR-ALS (Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares) | Decomposes complex mixtures into individual chemical species to study degradation profiles | Variables: Spectral data (UV-VIS, MS), concentration profile of analytes | Iterative least-squares approach with constraints (e.g., non-negativity, unimodality) | Extracts pure component spectra and concentration profiles, identifies intermediates and degradation pathways | Example: MCR-ALS revealed four components in the photodegradation of tamoxifen[166] |

| ANN (Artificial Neural Networks) | Used to model nonlinear relationships and predict chromatographic behavior | Input variables: molecular descriptors (polarizability, H-bond donors, etc.), chromatographic conditions | ANN uses multi-layer feedforward networks and Box-Behnken design for training and validation | Achieves high predictive accuracy (R² > 0.99) and avoids overfitting in chromatographic optimization | Example: ANN predicted retention factors and optimized RP-HPLC conditions for the separation of degradation products of candesartan cilexetil [163]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).