Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

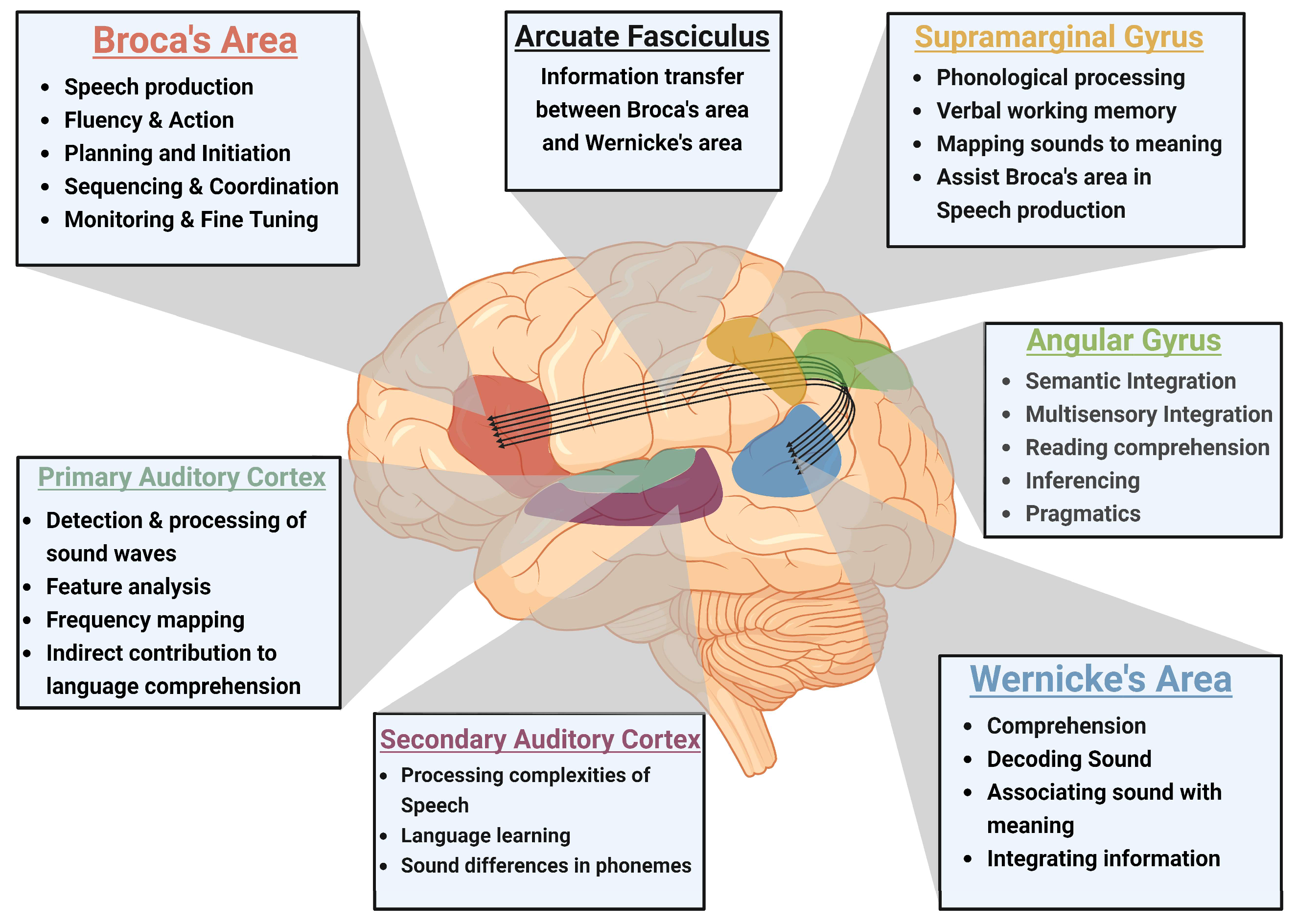

2. Neuroanatomy of Speech

2.1. Neuroanatomical Structures Involved in Speech Development

2.1.1. Broca's Area: Motor Aspects of Speech Production

2.1.2. Wernicke's Area: Language Comprehension

2.1.3. Arcuate Fasciculus: Connectivity and Coordination

2.1.4. Basal Ganglia: Modulation of Motor Speech

2.1.5. Cerebellum: Coordination and Timing

2.1.6. Primary Motor Cortex: Execution of Speech Movements

2.2. Neurodevelopmental Changes in Speech and Language Acquisition

3. Genetics of Speech

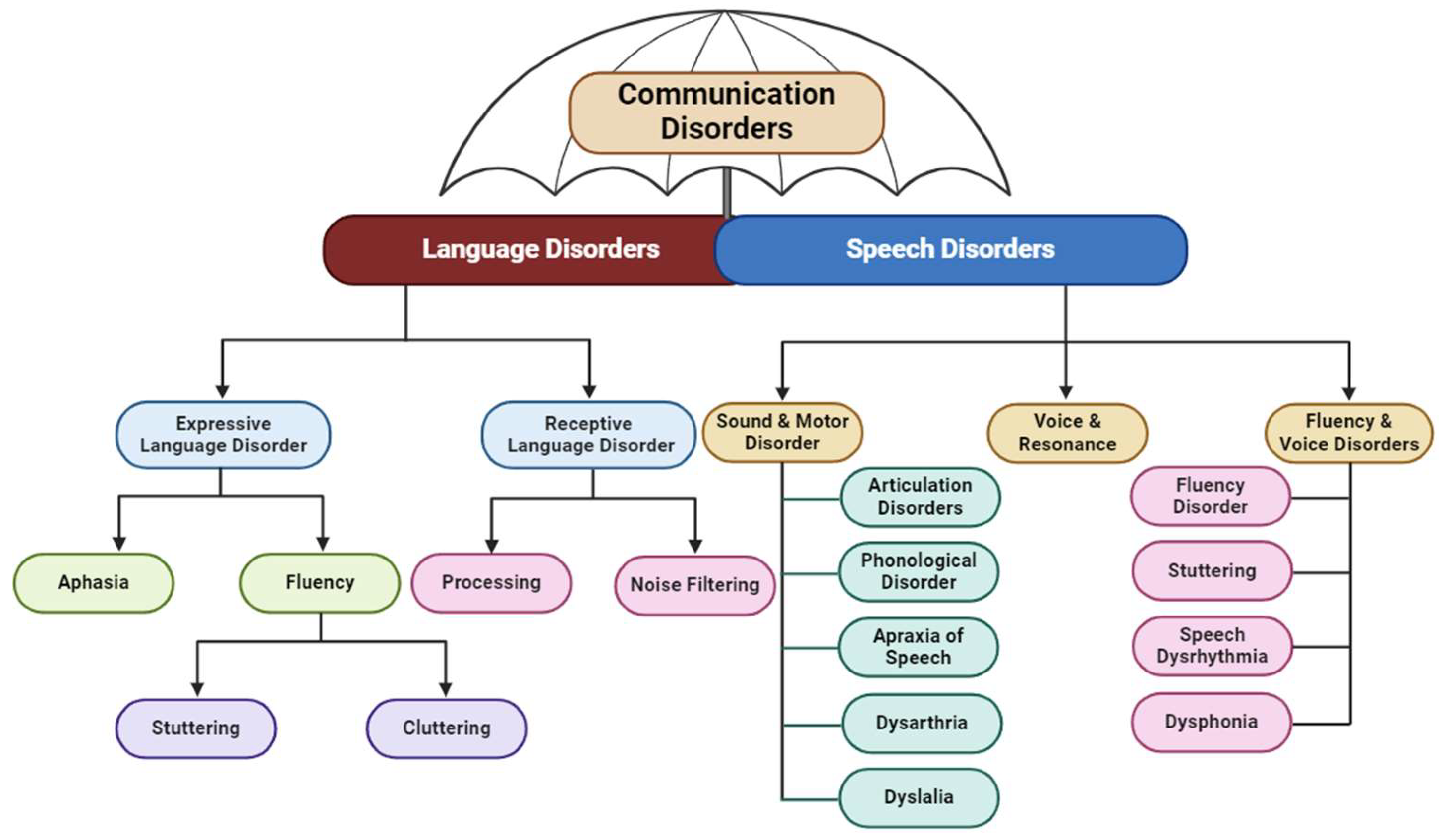

4. Speech Disorders

4.1. Speech Sound Disorders

4.1.1. Articulation Disorders

4.1.2. Phonological Disorders

4.2. Motor Speech Disorders

4.2.1. Apraxia of Speech

4.2.2. Dysarthria

4.3. Fluency Disorders

4.3.1. Stuttering

4.3.2. Cluttering

4.4. Dysphonia or Voice Disorder

4.4.1. Mutism

4.4.2. Selective Mutism

4.4.3. Cerebellar Mutism

4.4.4. Speech Dysrhythmia

4.4.5. Childhood Speech Disorders

4.4.6. Broca’s Aphasia

5. Psychological Comorbidities

5.1. Social Factors of Stuttering & Its Comorbidities

5.1.1. Cultural and Environmental Factors

5.1.2. Bilingualism

5.1.3. Linguistic Factors

5.1.4. Anxiety

5.1.5. Depression

5.1.6. Temperament

5.1.7. ADHD

6. Future Outlook

References

- Mountford HS, Braden R, Newbury DF, Morgan AT. The Genetic and Molecular Basis of Developmental Language Disorder: A Review. Children (Basel). 2022 Apr 20;9(5). [CrossRef]

- Morgan AT, Amor DJ, St John MD, Scheffer IE, Hildebrand MS. Genetic architecture of childhood speech disorder: a review. Molecular Psychiatry. 2024 May 1;29(5):1281–92. [CrossRef]

- Fujii M, Maesawa S, Ishiai S, Iwami K, Futamura M, Saito K. Neural Basis of Language: An Overview of An Evolving Model. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016 Jul 15;56(7):379–86. [CrossRef]

- Loucks T, Kraft SJ, Choo AL, Sharma H, Ambrose NG. Functional brain activation differences in stuttering identified with a rapid fMRI sequence. J Fluency Disord. 2011 Dec;36(4):302–7. [CrossRef]

- den Hoed J, Fisher SE. Genetic pathways involved in human speech disorders. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2020 Dec 1;65:103–11. [CrossRef]

- Rogalsky C, Basilakos A, Rorden C, Pillay S, LaCroix AN, Keator L, et al. The Neuroanatomy of Speech Processing: A Large-scale Lesion Study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2022 Jul 1;34(8):1355–75. [CrossRef]

- Friederici AD. The brain basis of language processing: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2011 Oct;91(4):1357–92. [CrossRef]

- Rogalsky C, Matchin W, Hickok G. Broca’s area, sentence comprehension, and working memory: an fMRI Study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2008;2:14. [CrossRef]

- Redcay E, Courchesne E. Deviant functional magnetic resonance imaging patterns of brain activity to speech in 2-3-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Oct 1;64(7):589–98. [CrossRef]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A, Matute E, Vélez-Uribe I. Language Development across the Life Span: A Neuropsychological/Neuroimaging Perspective. Neurosci J. 2014;2014:585237. [CrossRef]

- Skeide MA, Friederici AD. The ontogeny of the cortical language network. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 May;17(5):323–32. [CrossRef]

- Catani M, Mesulam M. The arcuate fasciculus and the disconnection theme in language and aphasia: history and current state. Cortex. 2008 Sep;44(8):953–61. [CrossRef]

- Paus T, Zijdenbos A, Worsley K, Collins DL, Blumenthal J, Giedd JN, et al. Structural maturation of neural pathways in children and adolescents: in vivo study. Science. 1999 Mar 19;283(5409):1908–11. [CrossRef]

- Ackermann H. Cerebellar contributions to speech production and speech perception: psycholinguistic and neurobiological perspectives. Trends Neurosci. 2008 Jun;31(6):265–72. [CrossRef]

- Ullman MT, Pierpont EI. Specific language impairment is not specific to language: The procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex. 2005;41(3):399–433. [CrossRef]

- Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Cortex. 2010 Aug;46(7):831–44. [CrossRef]

- Guenther FH. Cortical interactions underlying the production of speech sounds. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2006 Sep;39(5):350–65. [CrossRef]

- Tourville JA, Guenther FH. The DIVA model: A neural theory of speech acquisition and production. Lang Cogn Process. 2011 Jan 1;26(7):952–81. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl PK. Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron. 2010 Sep 9;67(5):713–27. [CrossRef]

- Werker JF, Tees RC. Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 1984 Jan 1;7(1):49–63. [CrossRef]

- Polikowsky HG, Shaw DM, Petty LE, Chen HH, Pruett DG, Linklater JP, et al. Population-based genetic effects for developmental stuttering. HGG Adv. 2022 Jan 13;3(1):100073. [CrossRef]

- Shaw DM, Polikowsky HP, Pruett DG, Chen HH, Petty LE, Viljoen KZ, et al. Phenome risk classification enables phenotypic imputation and gene discovery in developmental stuttering. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2021 Dec;108(12):2271–83. [CrossRef]

- Neef NE, Chang SE. Knowns and unknowns about the neurobiology of stuttering. PLoS Biol. 2024 Feb;22(2):e3002492. [CrossRef]

- Morgan A, Fisher SE, Scheffer I, Hildebrand M. FOXP2-Related Speech and Language Disorder. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(®). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2024, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.; 1993.

- Rappold G, Siper P, Kostic A, Braden R, Morgan A, Koene S, et al. FOXP1 Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(®). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2024, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.; 1993.

- Newbury DF, Gibson JL, Conti-Ramsden G, Pickles A, Durkin K, Toseeb U. Using Polygenic Profiles to Predict Variation in Language and Psychosocial Outcomes in Early and Middle Childhood. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019 Sep 20;62(9):3381–96. [CrossRef]

- Han TU, Root J, Reyes LD, Huchinson EB, Hoffmann JD, Lee WS, et al. Human GNPTAB stuttering mutations engineered into mice cause vocalization deficits and astrocyte pathology in the corpus callosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Aug 27;116(35):17515–24. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi N, Estiar MA, Fazilaty H, Sakhinia E. Variants in GNPTAB, GNPTG and NAGPA genes are associated with stutterers. Gene. 2018 Mar 20;647:93–100. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Wang G, Xia J, Zhou Y, Gao Y, Xu J, et al. Stuttering candidate genes DRD2 but not SLC6A3 is associated with developmental dyslexia in Chinese population. Behav Brain Funct. 2014 Sep 1;10(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Lan J, Song M, Pan C, Zhuang G, Wang Y, Ma W, et al. Association between dopaminergic genes (SLC6A3 and DRD2) and stuttering among Han Chinese. J Hum Genet. 2009 Aug;54(8):457–60. [CrossRef]

- Anthoni H, Sucheston LE, Lewis BA, Tapia-Páez I, Fan X, Zucchelli M, et al. The aromatase gene CYP19A1: several genetic and functional lines of evidence supporting a role in reading, speech and language. Behav Genet. 2012 Jul;42(4):509–27. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi H, Joghataei MT, Rahimi Z, Faghihi F, Khazaie H, Farhangdoost H, et al. Sex steroid hormones and sex hormone binding globulin levels, CYP17 MSP AI (-34T:C) and CYP19 codon 39 (Trp:Arg) variants in children with developmental stuttering. Brain Lang. 2017 Dec;175:47–56. [CrossRef]

- Morgan AT, Scerri TS, Vogel AP, Reid CA, Quach M, Jackson VE, et al. Stuttering associated with a pathogenic variant in the chaperone protein cyclophilin 40. Brain. 2023 Dec 1;146(12):5086–97. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Gao Y, Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wang D, et al. IFNAR1 gene mutation may contribute to developmental stuttering in the Chinese population. Hereditas. 2021 Dec;158(1):46. [CrossRef]

- Rehman AU, Hamid M, Khan SA, Eisa M, Ullah W, Rehman ZU, et al. The Expansion of the Spectrum in Stuttering Disorders to a Novel ARMC Gene Family (ARMC3). Genes (Basel). 2022 Dec 6;13(12):2299. [CrossRef]

- Feldman HM. How Young Children Learn Language and Speech. Pediatr Rev. 2019 Aug;40(8):398–411. [CrossRef]

- Rey OA, Sánchez-Delgado P, Palmer MRS, De Anda MCO, Gallardo VP. Exploratory study on the prevalence of speech sound disorders in a group of Valencian School students belonging to 3rd grade of infant school and 1st grade of primary school. Psicología Educativa Revista de los Psicólogos de la Educación. 2022;28(2):195–207. [CrossRef]

- Dodd B. Differential Diagnosis of Pediatric Speech Sound Disorder. Current Developmental Disorders Reports. 2014 Sep 1;1(3):189–96. [CrossRef]

- Jiramongkolchai P, Kumar MS, Chinnadurai S, Wootten CT, Goudy SL. Prevalence of hearing loss in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Aug;87:130–3. [CrossRef]

- Feldman HM, Messick C. Language and speech disorders. Developmental behavioral pediatrics. 2008;467–82. [CrossRef]

- Newbury DF, Monaco AP. Genetic advances in the study of speech and language disorders. Neuron. 2010 Oct 21;68(2):309–20. [CrossRef]

- Hayiou-Thomas ME, Carroll JM, Leavett R, Hulme C, Snowling MJ. When does speech sound disorder matter for literacy? The role of disordered speech errors, co-occurring language impairment and family risk of dyslexia. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017 Feb;58(2):197–205. [CrossRef]

- Pauls LJ, Archibald LM. Executive Functions in Children With Specific Language Impairment: A Meta-Analysis. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2016 Oct 1;59(5):1074–86. [CrossRef]

- Basilakos A, Fridriksson J. Types of motor speech impairments associated with neurologic diseases. Handb Clin Neurol. 2022;185:71–9. [CrossRef]

- Pernon M, Assal F, Kodrasi I, Laganaro M. Perceptual Classification of Motor Speech Disorders: The Role of Severity, Speech Task, and Listener’s Expertise. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2022 Aug 17;65(8):2727–47. [CrossRef]

- Landin-Romero R, Liang CT, Monroe PA, Higashiyama Y, Leyton CE, Hodges JR, et al. Brain changes underlying progression of speech motor programming impairment. Brain Commun. 2021;3(3):fcab205. [CrossRef]

- Webb WG. 8 - Clinical Speech Syndromes of the Motor Systems. In: Webb WG, editor. Neurology for the Speech-Language Pathologist (Sixth Edition). Mosby; 2017. p. 160–80.

- Jacks A, Haley KL. Apraxia of Speech. In: The Handbook of Language and Speech Disorders. 2021. p. 368–90.

- Malmenholt A, Lohmander A, McAllister A. Childhood apraxia of speech: A survey of praxis and typical speech characteristics. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2017 Jul;42(2):84–92. [CrossRef]

- Enderby P. Disorders of communication: dysarthria. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;110:273–81. [CrossRef]

- Atalar MS, Oguz O, Genc G. Hypokinetic Dysarthria in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2023;57(2):163–70. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell C, Bowen A, Tyson S, Butterfint Z, Conroy P. Interventions for dysarthria due to stroke and other adult-acquired, non-progressive brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1(1):Cd002088. [CrossRef]

- Neumann K, Euler HA, Bosshardt HG, Cook S, Sandrieser P, Sommer M. The Pathogenesis, Assessment and Treatment of Speech Fluency Disorders. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Jun 5;114(22–23):383–90. [CrossRef]

- Tichenor S, Yaruss JS. Repetitive Negative Thinking, Temperament, and Adverse Impact in Adults Who Stutter. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020 Feb 7;29(1):201–15. [CrossRef]

- Türkili S, Türkili S, Aydın ZF. Mental well-being and related factors in individuals with stuttering. Heliyon. 2022 Sep;8(9):e10446. [CrossRef]

- Van Borsel J. Acquired stuttering: A note on terminology. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2014 Jan 1;27(1):41–9. [CrossRef]

- Bóna J. Characteristics of pausing in normal, fast and cluttered speech. Clin Linguist Phon. 2016;30(11):888–98. [CrossRef]

- Krouse HJ, Reavis CCW, Stachler RJ, Francis DO, O’Connor S. Plain Language Summary: Hoarseness (Dysphonia). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Mar;158(3):427–31. [CrossRef]

- Saniasiaya J, Kulasegarah J, Narayanan P. New-Onset Dysphonia: A Silent Manifestation of COVID-19. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023 Apr;102(4):Np201-np202. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal A, Sharma DD, Kumar R, Sharma RC. Mutism as the presenting symptom: three case reports and selective review of literature. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010 Jan;32(1):61–4. [CrossRef]

- Mulligan C, Shipon-Blum E. Selective Mutism: Identification of Subtypes and Implications for Treatment. Journal of Education and Human Development. 2015 01;4. [CrossRef]

- Oerbeck B, Overgaard KR, Stein MB, Pripp AH, Kristensen H. Treatment of selective mutism: a 5-year follow-up study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018 Aug;27(8):997–1009. [CrossRef]

- Gudrunardottir T, De Smet HJ, Bartha-Doering L, van Dun K, Verhoeven J, Paquier P, et al. Chapter 11 - Posterior Fossa Syndrome (PFS) and Cerebellar Mutism. In: Mariën P, Manto M, editors. The Linguistic Cerebellum. San Diego: Academic Press; 2016. p. 257–313. [CrossRef]

- Launay J, Grube M, Stewart L. Dysrhythmia: a specific congenital rhythm perception deficit. Front Psychol. 2014;5:18. [CrossRef]

- Morgan A, Ttofari Eecen K, Pezic A, Brommeyer K, Mei C, Eadie P, et al. Who to Refer for Speech Therapy at 4 Years of Age Versus Who to “Watch and Wait”? J Pediatr. 2017 Jun;185:200-204.e1. [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Burraco A, Lattanzi W, Murphy E. Language Impairments in ASD Resulting from a Failed Domestication of the Human Brain. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:373. [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti E, Frustaci M, Zonca G, Aggujaro S, Molteni F, Luzzatti C. Disentangling phonological and articulatory processing: A neuroanatomical study in aphasia. Neuropsychologia. 2018 Dec;121:175–85. [CrossRef]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999 Jan;40(1):57–87.

- Albert U, Rosso G, Maina G, Bogetto F. Impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity on quality of life in euthymic bipolar disorder patients: differences between bipolar I and II subtypes. J Affect Disord. 2008 Jan;105(1–3):297–303. [CrossRef]

- Alm PA. Stuttering in relation to anxiety, temperament, and personality: review and analysis with focus on causality. J Fluency Disord. 2014 Jun;40:5–21. [CrossRef]

- Craig A, Blumgart E, Tran Y. The impact of stuttering on the quality of life in adults who stutter. J Fluency Disord. 2009 Jun;34(2):61–71. [CrossRef]

- Blood GW, Blood IM, Tellis G, Gabel R. Communication apprehension and self-perceived communication competence in adolescents who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2001 Sep;26(3):161–78. [CrossRef]

- Messenger M, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R. Social anxiety in stuttering: measuring negative social expectancies. J Fluency Disord. 2004;29(3):201–12. [CrossRef]

- Blood GW, Blood IM. Long-term Consequences of Childhood Bullying in Adults who Stutter: Social Anxiety, Fear of Negative Evaluation, Self-esteem, and Satisfaction with Life. J Fluency Disord. 2016 Dec;50:72–84. [CrossRef]

- Cook S, Howell P. Bullying in Children and Teenagers Who Stutter and the Relation to Self-Esteem, Social Acceptance, and Anxiety. Perspect Fluen Fluen Disord. 2014 Dec;24(2):46–57. [CrossRef]

- Bernard R, Hofslundsengen H, Frazier Norbury C. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Children and Adolescents Who Stutter: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2022 Feb 9;65(2):624–44. [CrossRef]

- Tellis G. Multicultural Considerations in Assessing and Treating Hispanic Americans who Stutter. Perspect Fluen Fluen Disord. 2008 Nov;18(3):101–10. [CrossRef]

- Nwokah EE. The imbalance of stuttering behavior in bilingual speakers. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 1988 Oct;13(5):357–73. [CrossRef]

- Dale P. Factors related to dysfluent speech in bilingual Cuban-American adolescents. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 1977 Dec;2(4):311–3. [CrossRef]

- Tichenor SE, Herring C, Yaruss JS. Understanding the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering Can Improve Stuttering Therapy. Topics in Language Disorders. 2022 Jan;42(1):57–75. [CrossRef]

- Yaruss JS. Dismissal Criteria for School-Age Children Who Stutter: When Is Enough Enough? One Opinion…. Perspect Fluen Fluen Disord. 2005 Apr;15(1):9–11. [CrossRef]

- Reitzes P. Response from the editor—Stuttering: Inspiring Stories and Professional Wisdom. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2013 Jun;38(2):235. [CrossRef]

- Boyle MP. Assessment of Stigma Associated With Stuttering: Development and Evaluation of the Self-Stigma of Stuttering Scale (4S). J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2013 Oct;56(5):1517–29. [CrossRef]

- Boyle MP. Enacted stigma and felt stigma experienced by adults who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2018 May;73:50–61. [CrossRef]

- Blanton S. A survey of speech defects. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1916 Dec;7(10):581–92.

- Karniol R. Stuttering, language, and cognition: A review and a model of stuttering as suprasegmental sentence plan alignment (SPA). Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(1):104–24. [CrossRef]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Fennema-Notestine C, Morris SK. Bilingualism affects picture naming but not picture classification. Memory & Cognition. 2005 Oct;33(7):1220–34. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval TC, Gollan TH, Ferreira VS, Salmon DP. What causes the bilingual disadvantage in verbal fluency? The dual-task analogy. Bilingualism. 2010 Apr;13(2):231–52. [CrossRef]

- Pelham SD, Abrams L. Cognitive advantages and disadvantages in early and late bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2014;40(2):313–25. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary C, Maruthy S, Guddattu V, Krishnan G. A systematic review on the role of language-related factors in the manifestation of stuttering in bilinguals. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2021 Jun;68:105829. [CrossRef]

- Van Borsel J, Maes E, Foulon S. Stuttering and bilingualism. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2001 Sep;26(3):179–205. [CrossRef]

- Howell P, Davis S, Williams R. The effects of bilingualism on stuttering during late childhood. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2009 Jan 1;94(1):42–6. [CrossRef]

- Bialystok E, Poarch G, Luo L, Craik FIM. Effects of bilingualism and aging on executive function and working memory. Psychology and Aging. 2014 Sep;29(3):696–705. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan MD, Janus M, Moreno S, Astheimer L, Bialystok E. Early stage second-language learning improves executive control: Evidence from ERP. Brain and Language. 2014 Dec;139:84–98. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein Ratner N, Brundage SB. Advances in Understanding Stuttering as a Disorder of Language Encoding. Annu Rev Linguist. 2024 Jan 16;10(1):127–43. [CrossRef]

- Kornisch M. Bilinguals who stutter: A cognitive perspective. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2021 Mar;67:105819. [CrossRef]

- Loe IM, Feldman HM. The Effect of Bilingual Exposure on Executive Function Skills in Preterm and Full-Term Preschoolers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016 Sep;37(7):548–56. [CrossRef]

- Arizmendi GD, Alt M, Gray S, Hogan TP, Green S, Cowan N. Do Bilingual Children Have an Executive Function Advantage? Results From Inhibition, Shifting, and Updating Tasks. LSHSS. 2018 Jul 5;49(3):356–78. [CrossRef]

- Carias S, Ingram D. Language and disfluency: Four case studies on Spanish-English bilingual children. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders. 2006 Jan;4(2):149–57. [CrossRef]

- Kashyap P, Maruthy S. Stuttering frequency and severity in Kannada-English balanced bilingual adults. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2020 Mar 3;34(3):271–89. [CrossRef]

- Tsai C. Linguistic Know-How: The Limits of Intellectualism. Theoria. 2011 Mar;77(1):71–86.

- Brown SF. The Loci of Stutterings In The Speech Sequence. J Speech Disord. 1945 Sep;10(3):181–92. [CrossRef]

- 103. Howell P, Van Borsel J, editors. Multilingual Aspects of Fluency Disorders [Internet]. Multilingual Matters; 2011 [cited 2024 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781847693570/html.

- Ononiwu, CA.THE IMPACT OF SYLLABLE STRUCTURE COMPLEXITY ON STUTTERING FREQUENCY FOR BILINGUALS AND MULTILINGUALS WHO STUTTER.

- Jakielski KJ. The Index of Phonetic Complexity: At-a-Glance Scoring System, Terminology, Instructions, & Data Forms.

- Howell P, Au-Yeung J. Phonetic complexity and stuttering in Spanish. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2007 Jan;21(2):111–27. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi F, Khamaiseh Z, Howell P. Phonetic complexity and stuttering in Arabic. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2013 Dec;27(12):874–87. [CrossRef]

- Essau CA, Olaya B, Ollendick TH. Classification of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of The Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2013 [cited 2024 Nov 13]. p. 1–21. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118315088.ch1.

- Smith KA, Iverach L, O’Brian S, Kefalianos E, Reilly S. Anxiety of children and adolescents who stutter: a review. J Fluency Disord. 2014 Jun;40:22–34. [CrossRef]

- McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Use of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations in a clinically depressed sample: factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress. J Clin Psychol. 2003 Apr;59(4):423–37. [CrossRef]

- Ingham RJ. Stuttering and behavior therapy. San Diego, Calif: College-Hill Pr; 1984. 480 p.

- Menzies RG, Onslow M, Packman A. Anxiety and Stuttering: Exploring a Complex Relationship. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1999 Feb;8(1):3–10. [CrossRef]

- Craig A, Hancock K, Tran Y, Craig M. Anxiety levels in people who stutter: a randomized population study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003 Oct;46(5):1197–206. [CrossRef]

- De Nil LF, Brutten GJ. Speech-associated attitudes of stuttering and nonstuttering children. J Speech Hear Res. 1991 Feb;34(1):60–6. [CrossRef]

- Blood GW, Blood IM, Maloney K, Meyer C, Qualls CD. Anxiety levels in adolescents who stutter. J Commun Disord. 2007;40(6):452–69. [CrossRef]

- Craig A, Tran Y. Trait and social anxiety in adults with chronic stuttering: conclusions following meta-analysis. J Fluency Disord. 2014 Jun;40:35–43. [CrossRef]

- Iverach L, O’Brian S, Jones M, Block S, Lincoln M, Harrison E, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among adults seeking speech therapy for stuttering. J Anxiety Disord. 2009 Oct;23(7):928–34. [CrossRef]

- Iverach L, Rapee RM. Social anxiety disorder and stuttering: current status and future directions. J Fluency Disord. 2014 Jun;40:69–82. [CrossRef]

- Bloodstein O. Interpersonal dynamics and the treatment of the stutterer. Journal of Communication Disorders. 1967 May;1(1):58–65.

- Blomgren M, Roy N, Callister T, Merrill RM. Intensive stuttering modification therapy: a multidimensional assessment of treatment outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005 Jun;48(3):509–23. [CrossRef]

- Menzies RG, O’Brian S, Onslow M, Packman A, St Clare T, Block S. An experimental clinical trial of a cognitive-behavior therapy package for chronic stuttering. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008 Dec;51(6):1451–64. [CrossRef]

- Craig A. An investigation into the relationship between anxiety and stuttering. J Speech Hear Disord. 1990 May;55(2):290–4. [CrossRef]

- Ingham RJ, Andrews G. The relation between anxiety reduction and treatment. Journal of Communication Disorders. 1971 Dec;4(4):289–301. [CrossRef]

- Briley PM, Ellis C. The Coexistence of Disabling Conditions in Children Who Stutter: Evidence From the National Health Interview Survey. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2018 Dec 10;61(12):2895–905. [CrossRef]

- Doruk A, Türkbay T, Yelbo Z, Sütçigil L, Özflahin A. Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance in Young Adults with Developmental Stuttering. 2008;18(4).

- Bray MA, Kehle TJ, Lawless KA, Theodore LA. The relationship of self-efficacy and depression to stuttering. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2003 Nov;12(4):425–31. [CrossRef]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: origins and outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000 Jan;78(1):122–35. [CrossRef]

- Cloninger CR. Temperament and personality. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994 Apr;4(2):266–73. [CrossRef]

- Walden TA, Frankel CB, Buhr AP, Johnson KN, Conture EG, Karrass JM. Dual diathesis-stressor model of emotional and linguistic contributions to developmental stuttering. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012 May;40(4):633–44. [CrossRef]

- Côté SM, Boivin M, Liu X, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, Tremblay RE. Depression and anxiety symptoms: onset, developmental course and risk factors during early childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009 Oct;50(10):1201–8. [CrossRef]

- Conture EG, Walden TA. DUAL DIATHESIS-STRESSOR MODEL OF STUTTERING.

- Rocha MS, Yaruss JS, Rato JR. Temperament, Executive Functioning, and Anxiety in School-Age Children Who Stutter. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2244. [CrossRef]

- Harris KS. The nature of stuttering (2nd Ed.). Charles Van Riper. Englwewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1982. Pp. x + 468. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1983 Jun;4(2):177–9.

- Jones R, Choi D, Conture E, Walden T. Temperament, emotion, and childhood stuttering. Semin Speech Lang. 2014 May;35(2):114–31. [CrossRef]

- Eggers K, De Nil LF, Van den Bergh BRH. Temperament dimensions in stuttering and typically developing children. J Fluency Disord. 2010 Dec;35(4):355–72. [CrossRef]

- Kefalianos E, Onslow M, Ukoumunne OC, Block S, Reilly S. Temperament and Early Stuttering Development: Cross-Sectional Findings From a Community Cohort. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2017 Apr 14;60(4):772–84. [CrossRef]

- Kraft SJ, Lowther E, Beilby J. The Role of Effortful Control in Stuttering Severity in Children: Replication Study. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2019 Feb 21;28(1):14–28. [CrossRef]

- Jo Kraft S, Ambrose N, Chon H. Temperament and environmental contributions to stuttering severity in children: the role of effortful control. Semin Speech Lang. 2014 May;35(2):80–94. [CrossRef]

- Tumanova V, Zebrowski PM, Throneburg RN, Kulak Kayikci ME. Articulation rate and its relationship to disfluency type, duration, and temperament in preschool children who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2011 Jan;44(1):116–29. [CrossRef]

- Delpeche S, Millard S, Kelman E. The role of temperament in stuttering frequency and impact in children under 7. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2022 May;97:106201. [CrossRef]

- Alderson RM, Rapport MD, Sarver DE, Kofler MJ. ADHD and Behavioral Inhibition: A Re-examination of the Stop-signal Task. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008 Oct;36(7):989–98. [CrossRef]

- Alm PA, Risberg J. Stuttering in adults: the acoustic startle response, temperamental traits, and biological factors. J Commun Disord. 2007;40(1):1–41. [CrossRef]

- Bental B, Tirosh E. The relationship between attention, executive functions and reading domain abilities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and reading disorder: a comparative study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 May;48(5):455–63. [CrossRef]

- Chhabildas N, Pennington BF, Willcutt EG. A comparison of the neuropsychological profiles of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001 Dec;29(6):529–40. [CrossRef]

- Donaher J, Richels C. Traits of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children who stutter. J Fluency Disord. 2012 Dec;37(4):242–52. [CrossRef]

- Druker K, Hennessey N, Mazzucchelli T, Beilby J. Elevated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children who stutter. J Fluency Disord. 2019 Mar;59:80–90. [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt PE, Corley M, Nigg JT, Ferreira F. The role of inhibition in the production of disfluencies. Mem Cognit. 2010 Jul;38(5):617–28. [CrossRef]

- Healey EC, Reid R. ADHD and stuttering: a tutorial. J Fluency Disord. 2003;28(2):79–92; quiz 93. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Lee H, Baik B, Kim K, Kim R. Failure mode and effects analysis drastically reduced potential risks in clinical trial conduct. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2017;11:3035–43. [CrossRef]

- Anderson JD, Pellowski MW, Conture EG, Kelly EM. Temperamental characteristics of young children who stutter. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003 Oct;46(5):1221–33. [CrossRef]

- Karrass J, Walden TA, Conture EG, Graham CG, Arnold HS, Hartfield KN, et al. Relation of emotional reactivity and regulation to childhood stuttering. J Commun Disord. 2006;39(6):402–23. [CrossRef]

- Martel MM, Nigg JT. Child ADHD and personality/temperament traits of reactive and effortful control, resiliency, and emotionality. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;47(11):1175–83. [CrossRef]

- Walcott CM, Landau S. The relation between disinhibition and emotion regulation in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004 Dec;33(4):772–82. [CrossRef]

- Eggers K, De Nil LF, Van den Bergh BRH. Inhibitory control in childhood stuttering. J Fluency Disord. 2013 Mar;38(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Schwenk KA, Conture EG, Walden TA. Reaction to background stimulation of preschool children who do and do not stutter. J Commun Disord. 2007;40(2):129–41. [CrossRef]

- Ambrose NG, Cox NJ, Yairi E. The genetic basis of persistence and recovery in stuttering. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997 Jun;40(3):567–80. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemot C, Scott SK. What is the relationship between phonological short-term memory and speech processing? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006 Nov;10(11):480–6. [CrossRef]

- Marchetta NDJ, Hurks PPM, Krabbendam L, Jolles J. Interference control, working memory, concept shifting, and verbal fluency in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neuropsychology. 2008 Jan;22(1):74–84. [CrossRef]

- Martinussen R, Hayden J, Hogg-Johnson S, Tannock R. A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;44(4):377–84. [CrossRef]

- Postma A, Kolk H. The covert repair hypothesis: prearticulatory repair processes in normal and stuttered disfluencies. J Speech Hear Res. 1993 Jun;36(3):472–87.

- Kazazi F. Assessing Executive Function Impairments and Comorbidity between ADHD and Stuttering.

- Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. [CrossRef]

- Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HLJ, Borsboom D. Comorbidity: a network perspective. Behav Brain Sci. 2010 Jun;33(2–3):137–50; discussion 150-193. [CrossRef]

- Epskamp S, Rhemtulla M, Borsboom D. Generalized Network Psychometrics: Combining Network and Latent Variable Models. Psychometrika. 2017 Dec;82(4):904–27. [CrossRef]

- Borsboom D, Deserno MK, Rhemtulla M, Epskamp S, Fried EI, McNally RJ, et al. Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021 Aug 19;1(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Eggers K, Millard SK, Kelman E. Temperament, anxiety, and depression in school-age children who stutter. J Commun Disord. 2022;97:106218. [CrossRef]

- Kohmäscher A, Primaßin A, Heiler S, Avelar PDC, Franken MC, Heim S. Effectiveness of Stuttering Modification Treatment in School-Age Children Who Stutter: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2023 Nov 9;66(11):4191–205. [CrossRef]

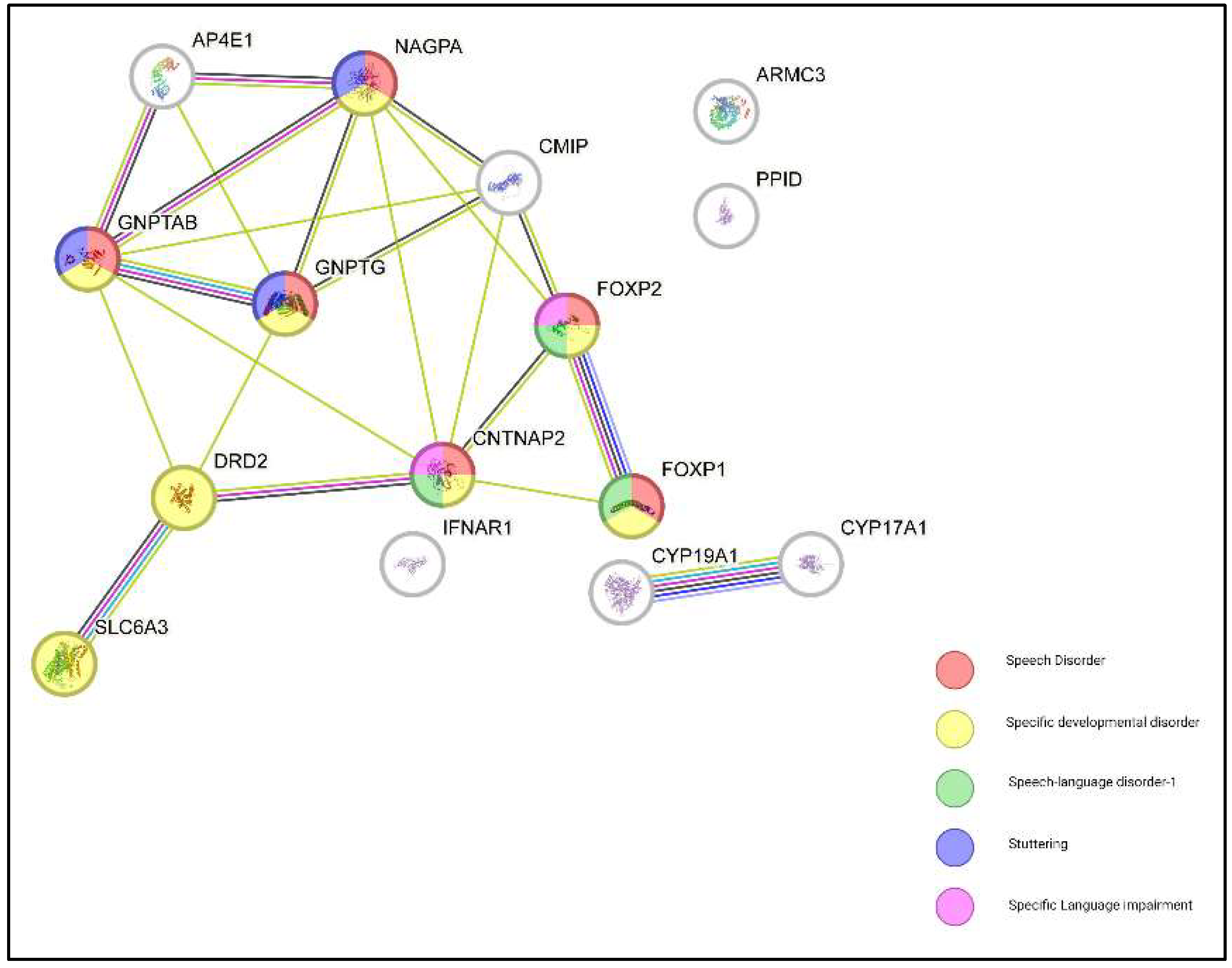

| Gene | Associated Disorder/Function | Chromosomal Location | Role in Speech and Language | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOXP2 | Verbal Dyspraxia | Chromosome 7q | Regulates genes in brain regions for motor control, impacting speech and language. Disruption leads to speech deficits. Acts as a transcription factor, reducing neural gene expression. | [24] |

| FOXP1 | Speech and Language Mechanisms | Chromosome 3 | Involved in neural circuitry for speech and language development. Disruption causes speech delays and developmental issues. | [25] |

| CNTNAP2 | Complex Language Impairment | Chromosome 7q35-q36.1 | Encodes a neurexin protein for synapse function. Mutations linked to SLI and SSD. Works with FOXP2 in gene-expression networks. | [26] |

| GNPTAB | Stuttering | Various chromosomes (2,3,5,7,9) | Involved in the lysosomal enzyme pathway. Mutations linked to stuttering. | [27] |

| GNPTG | Stuttering | Chromosome 7 | Similar to GNPTAB, involved in lysosomal enzyme pathway. Mutations linked to stuttering. | [27] |

| NAGPA | Stuttering | Chromosome 16p13.3 | Involved in lysosomal enzyme targeting. Mutations contribute to stuttering. | [28] |

| CMIP | Specific Language Impairment (SLI) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Chromosome 16q23.2 | Regulates phonological memory, critical for language acquisition. Linked to SLI and ASD. | [26] |

| TCF4, STOX1A | Combinatorial Gene-Expression Network in Speech | Chromosome 18q21.2, Chromosome 10q22.1 | Involved in gene networks with FOXP2 and CNTNAP2 for speech and language development. | [1,26] |

| DRD2 | Stuttering | Chromosome 11q23.2 | Encodes dopamine receptor D2, linked to susceptibility to stuttering. | [29] |

| SLC6A3 | Stuttering | Chromosome 5p15.33 | Encodes dopamine transporter (DAT); mutations affect speech and language, linked to stuttering. | [30] |

| CYP19A1 | Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Chromosome 15q21.1 | Involved in estrogen synthesis, potentially linked to neurodevelopmental speech disorders. | [31] |

| CYP17A1 | Neurodevelopmental Processes | Chromosome 10q24.32 | Influences steroid hormone biosynthesis; role in speech disorders unclear. | [32] |

| PPID | Persistent Stuttering | Chromosome 4q33 | Involved in protein folding; mutations linked to stuttering by affecting brain development. | [33] |

| AP4E1 | Neuroanatomical Anomalies | Chromosome 15q21.2 | Mutations associated with brain anomalies in people who stutter. | [22] |

| IFNAR1 | Developmental Stuttering | Chromosome 21q22.11 | Mutations linked to stuttering in certain populations. | [34] |

| ARMC3 | Persistent Stuttering | Chromosome 10p15.3 | Associated with non-syndromic persistent stuttering in specific populations. | [35] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).