Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

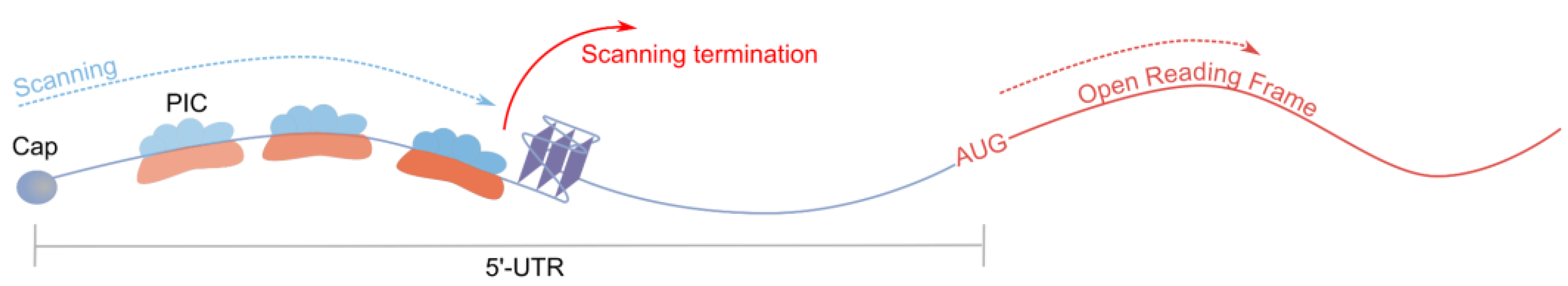

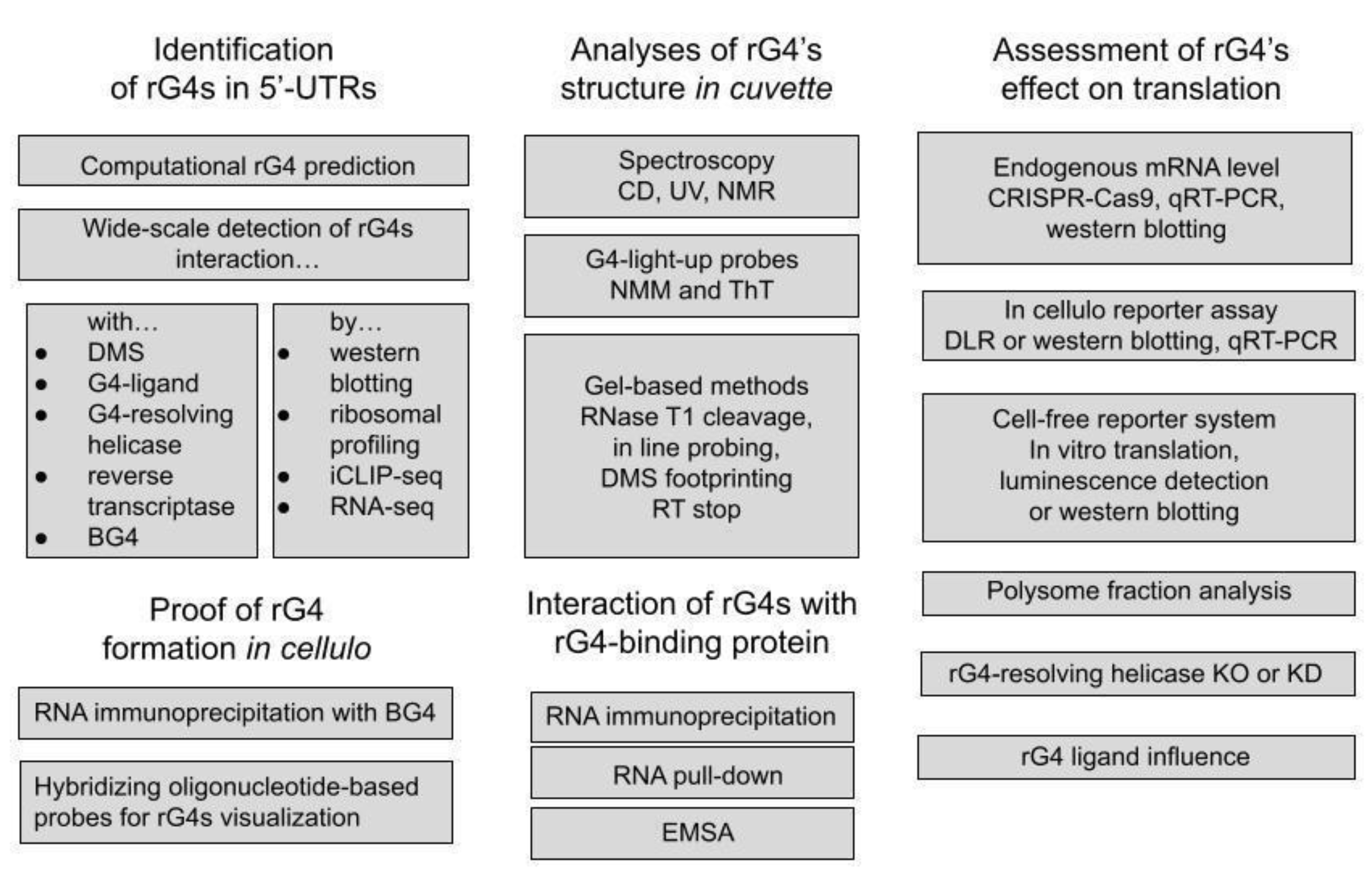

2. Translation-Inhibiting rG4s

2.1. Origins: First Identified Translation-Inhibiting rG4s

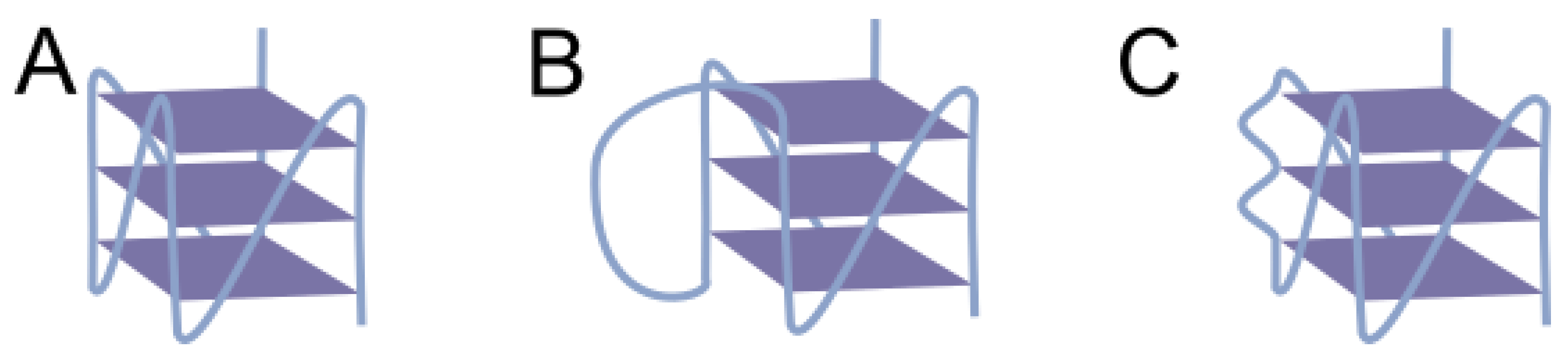

2.2. Non-Canonical rG4s Inhibiting Translation

2.3. Involvement of rG4-Binding Proteins in Translation Inhibition

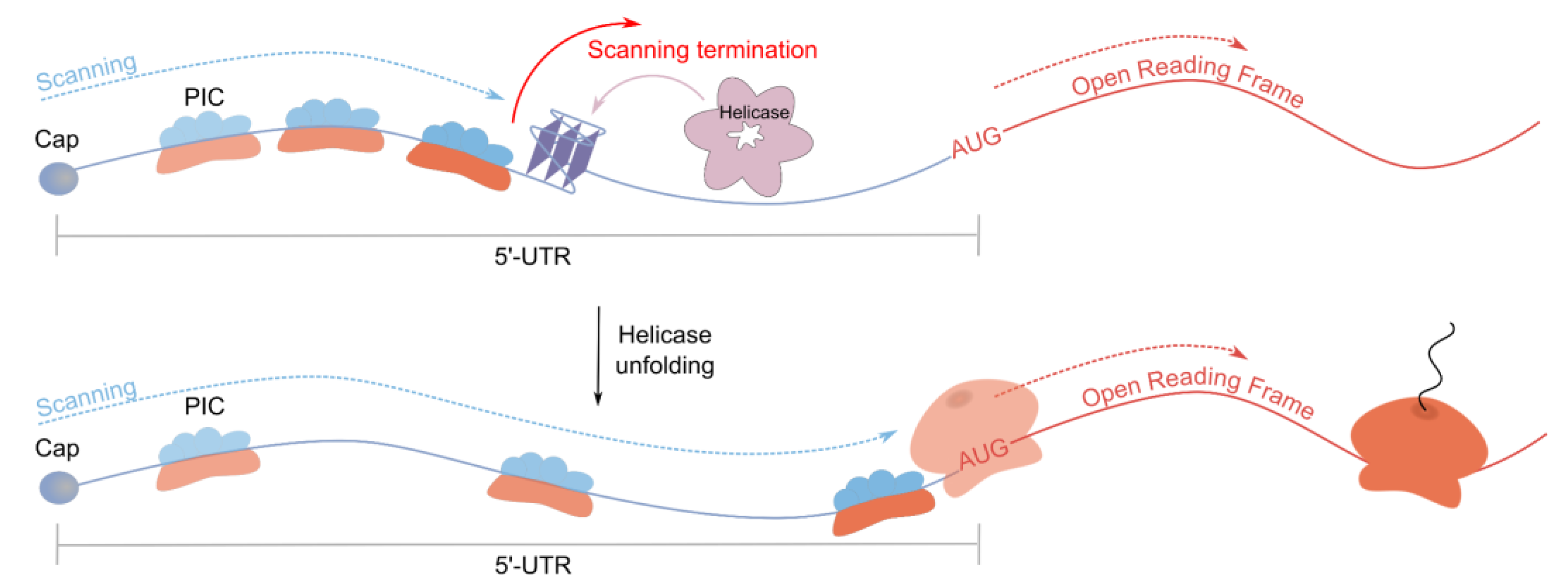

2.3.1. Investigation of Inhibitory rG4s in Context of Their Helicase Interactions

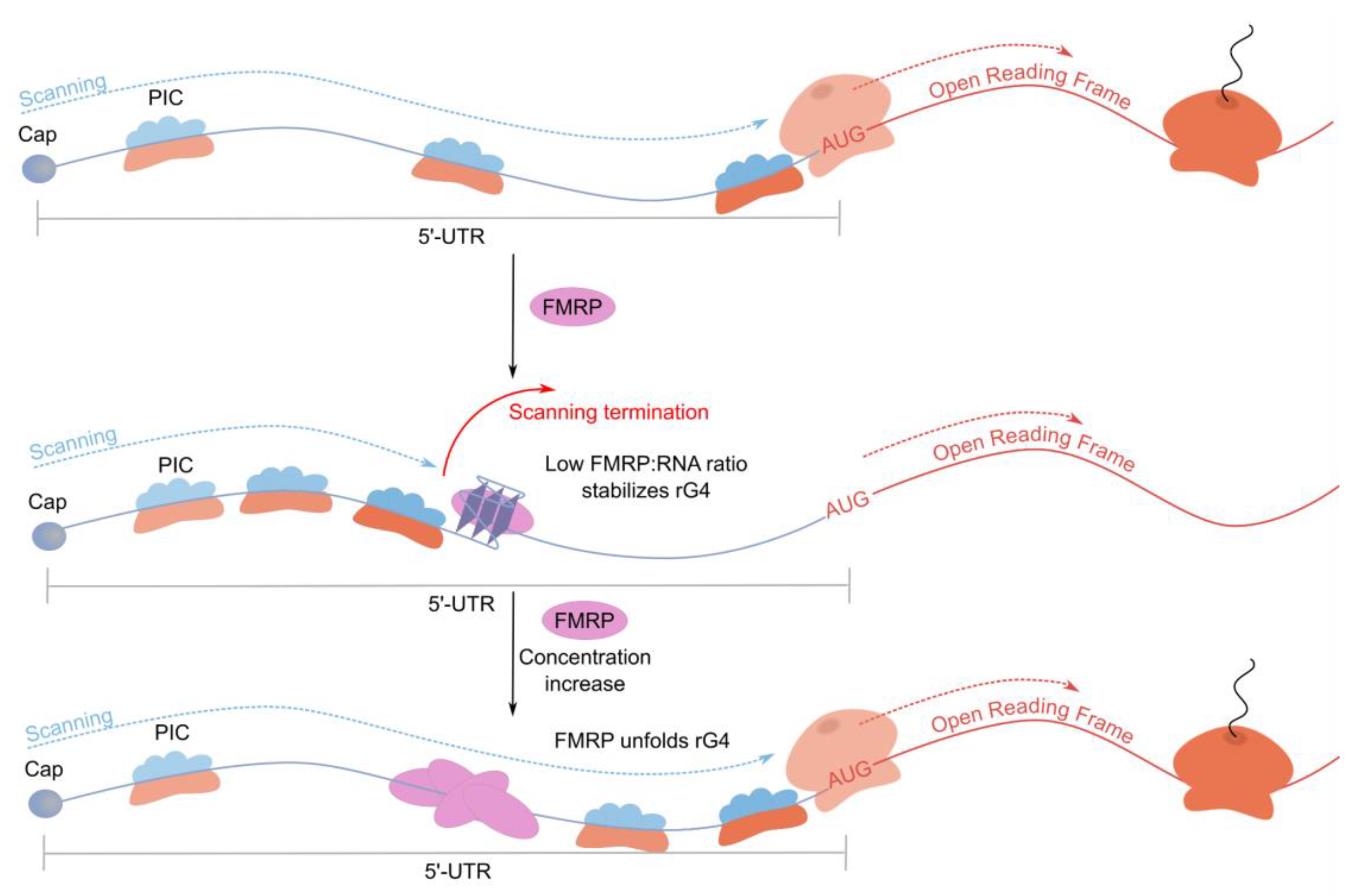

2.3.2. FMRP: rG4-Binding Protein Inhibiting Translation

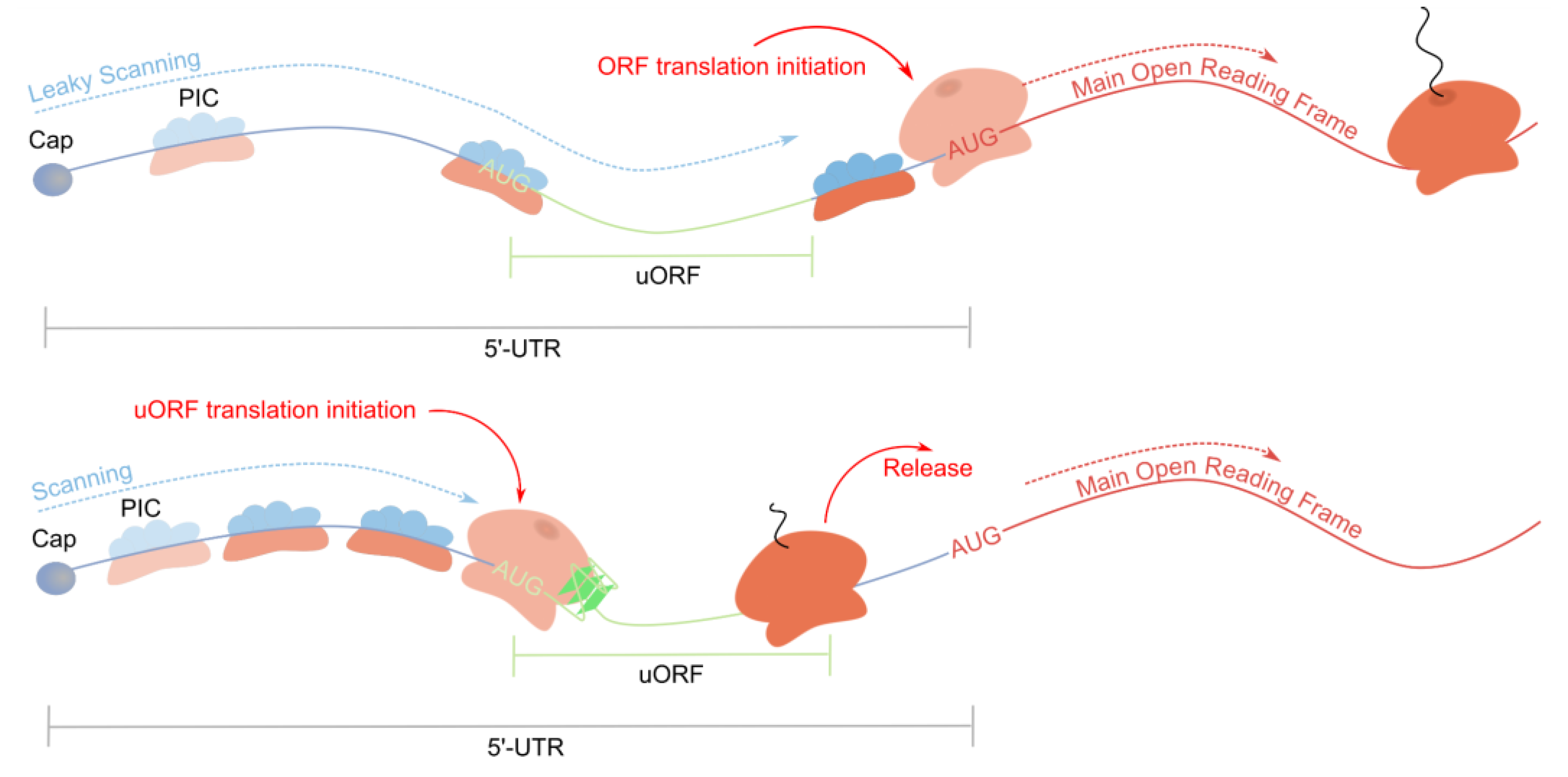

3.1. Synergistic Translation Inhibition by rG4s and Upstream Open Reading Frames

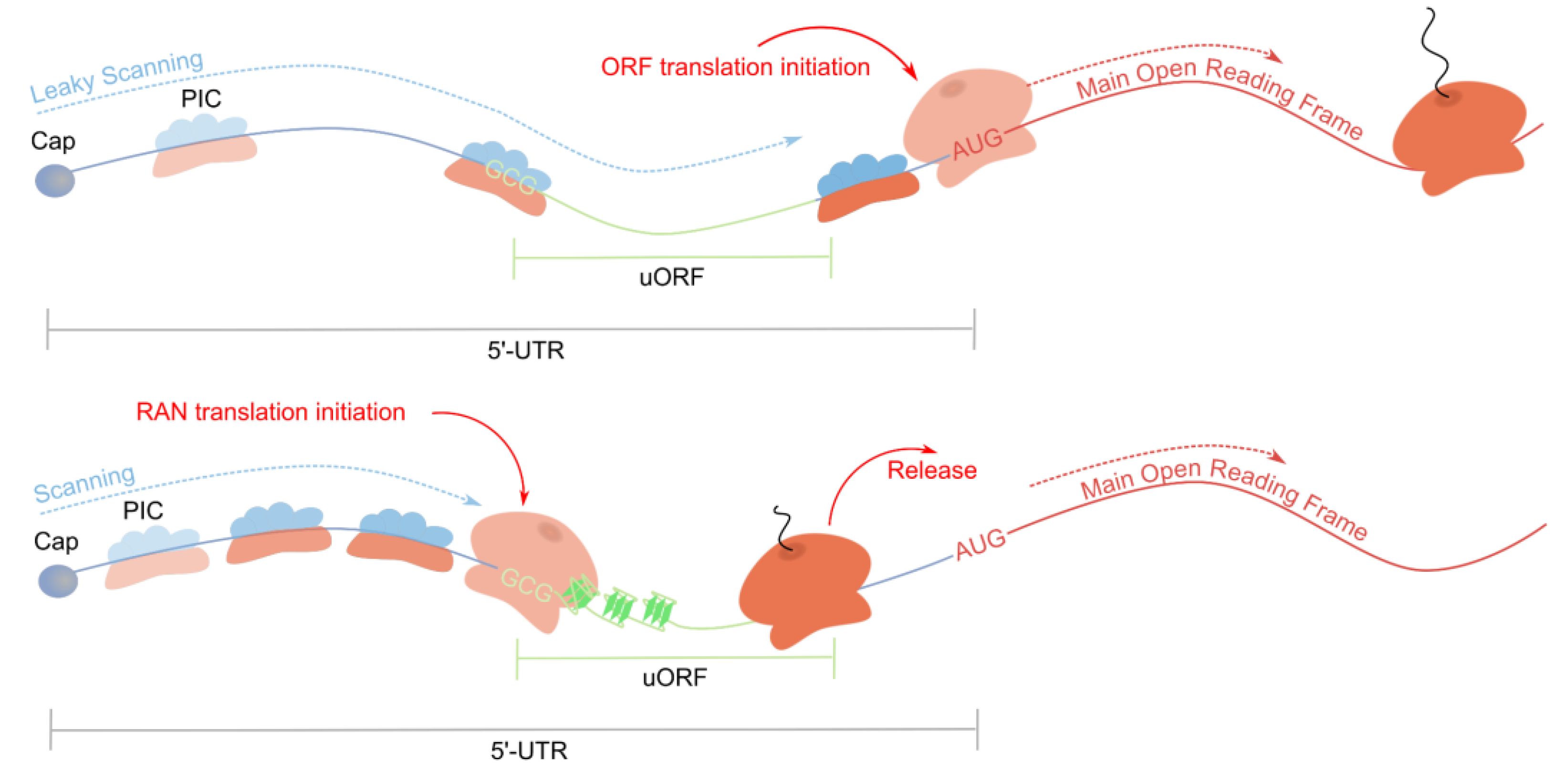

3.2. FMR1 mRNA and Repeat-Associated Non-AUG Translation

4.2. Other Translation-Enhancing rG4s

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tants, J.-N.; Schlundt, A. The Role of Structure in Regulatory RNA Elements. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20240139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppek, K.; Das, R.; Barna, M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA Structures in Eukaryotic Translation Regulation and How to Find Them. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R.; Saleem, I.; Mustoe, A.M. Causes, Functions, and Therapeutic Possibilities of RNA Secondary Structure Ensembles and Alternative States. Cell Chem. Biol. 2024, 31, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, D.; Spiegel, J.; Zyner, K.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. The Regulation and Functions of DNA and RNA G-Quadruplexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, M.M.; Lyons, S.M.; Ivanov, P. RNA G-Quadruplexes in Biology: Principles and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2127–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.K.; Marsico, G.; Sahakyan, A.B.; Chambers, V.S.; Balasubramanian, S. rG4-Seq Reveals Widespread Formation of G-Quadruplex Structures in the Human Transcriptome. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Lejault, P.; Chevrier, S.; Boidot, R.; Robertson, A.G.; Wong, J.M.Y.; Monchaud, D. Transcriptome-Wide Identification of Transient RNA G-Quadruplexes in Human Cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.U.; Bartel, D.P. RNA G-Quadruplexes Are Globally Unfolded in Eukaryotic Cells and Depleted in Bacteria. Science 2016, 353, aaf5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.-L.; Xu, Y. Investigation of Higher-Order RNA G-Quadruplex Structures in Vitro and in Living Cells by 19F NMR Spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglietta, G.; Marinello, J.; Capranico, G. Immunofluorescence Microscopy of G-Quadruplexes and R-Loops. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2024; Vol. 695, pp. 103–118 ISBN 978-0-443-21774-6.

- Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Dai, J.; Yuan, J.; Ou, T.; Huang, Z.; Tan, J. Tracking the Dynamic Folding and Unfolding of RNA G-Quadruplexes in Live Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4702–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugaut, A.; Balasubramanian, S. 5’-UTR RNA G-Quadruplexes: Translation Regulation and Targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4727–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bugaut, A.; Huppert, J.L.; Balasubramanian, S. An RNA G-Quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS Proto-Oncogene Modulates Translation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, A.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Scaria, V.; Hariharan, M.; Maiti, S.; Kurreck, J. Inhibition of Translation in Living Eukaryotic Cells by an RNA G-Quadruplex Motif. RNA 2008, 14, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, K.; Wieland, M.; Hartig, J.S. Predictable Suppression of Gene Expression by 5′-UTR-Based RNA Quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 6811–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bugaut, A.; Balasubramanian, S. Position and Stability Are Determining Factors for Translation Repression by an RNA G-Quadruplex-Forming Sequence within the 5′ UTR of the NRAS Proto-Oncogene. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 12664–12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.; Joseph, S. The Fragile X Proteins Differentially Regulate Translation of Reporter mRNAs with G-Quadruplex Structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.; Guédin, A.; Mergny, J.-L.; Salles, B.; Riou, J.-F.; Teulade-Fichou, M.-P.; Calsou, P. A G-Quadruplex Structure within the 5′-UTR of TRF2 mRNA Represses Translation in Human Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7187–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.J.; Wingate, K.L.; Silwal, J.; Leeper, T.C.; Basu, S. The Porphyrin TmPyP4 Unfolds the Extremely Stable G-Quadruplex in MT3-MMP mRNA and Alleviates Its Repressive Effect to Enhance Translation in Eukaryotic Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4137–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, G.D.; Derecka, K.; Garner, T.P.; Hodgman, C.; Flint, A.P.F.; Searle, M.S. Repression of Translation of Human Estrogen Receptor α by G-Quadruplex Formation. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11487–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, H.-Y.; Huang, H.-L.; Zhao, P.-P.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.-H. Translational Repression of Cyclin D3 by a Stable G-Quadruplex in Its 5′ UTR: Implications for Cell Cycle Regulation. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.; Bugaut, A.; Balasubramanian, S. The BCL-2 5′ Untranslated Region Contains an RNA G-Quadruplex-Forming Motif That Modulates Protein Expression. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 8300–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serikawa, T.; Eberle, J.; Kurreck, J. Effects of Genomic Disruption of a Guanine Quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the Bcl-2 mRNA in Melanoma Cells. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3649–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammich, S.; Kamp, F.; Wagner, J.; Nuscher, B.; Zilow, S.; Ludwig, A.-K.; Willem, M.; Haass, C. Translational Repression of the Disintegrin and Metalloprotease ADAM10 by a Stable G-Quadruplex Secondary Structure in Its 5′-Untranslated Region. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 45063–45072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.J.; Basu, S. An Unusually Stable G-Quadruplex within the 5′-UTR of the MT3 Matrix Metalloproteinase mRNA Represses Translation in Eukaryotic Cells. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 5313–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, J.-D.; Perreault, J.-P. 5’-UTR G-Quadruplex Structures Acting as Translational Repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7022–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, P.; Pandey, S.; Maiti, S. Role of G-Quadruplex Located at 5ʹ End of mRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 3503–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacht, A.V.; Seifert, O.; Menger, M.; Schütze, T.; Arora, A.; Konthur, Z.; Neubauer, P.; Wagner, A.; Weise, C.; Kurreck, J. Identification and Characterization of RNA Guanine-Quadruplex Binding Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6630–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaji, H.; Lizio, M.; Itoh, M.; Kanamori-Katayama, M.; Kaiho, A.; Nishiyori-Sueki, H.; Shin, J.W.; Kojima-Ishiyama, M.; Kawano, M.; Murata, M.; et al. Comparison of CAGE and RNA-Seq Transcriptome Profiling Using Clonally Amplified and Single-Molecule next-Generation Sequencing. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, P.G.; Tsiakanikas, P.; Stolidi, I.; Scorilas, A. A Versatile 5′ RACE-Seq Methodology for the Accurate Identification of the 5′ Termini of mRNAs. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaratnam, S.; Torrey, Z.R.; Calabrese, D.R.; Banco, M.T.; Yazdani, K.; Liang, X.; Fullenkamp, C.R.; Seshadri, S.; Holewinski, R.J.; Andresson, T.; et al. Investigating the NRAS 5′ UTR as a Target for Small Molecules. Cell Chem. Biol. 2023, 30, 643–657.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuda, Y.; Sato, S.; Asano, L.; Morimura, Y.; Furuta, T.; Sugiyama, H.; Hagihara, M.; Uesugi, M. A Small Molecule That Represses Translation of G-Quadruplex-Containing mRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9037–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, H.L.; Hagen, T.; Tatum, N.J.; Hall, J. The Diverse Structural Landscape of Quadruplexes. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 2083–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yuan, J.; Xue, G.; Campanario, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, W.; Mou, X.; Liew, S.W.; Umar, M.I.; Isern, J.; et al. Translational Control by DHX36 Binding to 5′UTR G-Quadruplex Is Essential for Muscle Stem-Cell Regenerative Functions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédin, A.; Gros, J.; Alberti, P.; Mergny, J.-L. How Long Is Too Long? Effects of Loop Size on G-Quadruplex Stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7858–7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodoin, R.; Bauer, L.; Garant, J.-M.; Mahdi Laaref, A.; Phaneuf, F.; Perreault, J.-P. The Folding of 5′-UTR Human G-Quadruplexes Possessing a Long Central Loop. RNA 2014, 20, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodoin, R.; Perreault, J.-P. G-Quadruplexes Formation in the 5’UTRs of mRNAs Associated with Colorectal Cancer Pathways. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0208363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuda, Y.; Sato, S.; Inoue, M.; Tsugawa, H.; Kamura, T.; Kida, T.; Matsumoto, R.; Asamitsu, S.; Shioda, N.; Shiroto, S.; et al. Small Molecule-Based Detection of Non-Canonical RNA G-Quadruplex Structures That Modulate Protein Translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 8143–8153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sinha, S.; Kundu, C.N. Nectin Cell Adhesion Molecule-4 (NECTIN-4): A Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 911, 174516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silacci, P.; Mazzolai, L.; Gauci, C.; Stergiopulos, N.; Yin, H.L.; Hayoz, D. Gelsolin Superfamily Proteins: Key Regulators of Cellular Functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Z. CapG Promoted Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cell Motility Involving Rho Motility Pathway Independent of ROCK. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, H.; An, L.; Hou, S.; Zhang, Q. CAPG Facilitates Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Cell Progression through PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Hum. Immunol. 2022, 83, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Zhao, M.; Long, B.; Li, H. Super-Enhancer-Associated Gene CAPG Promotes AML Progression. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, P.; Pal, G.; Pandey, S.; Maiti, S. Mutagenesis Reveals an Unusual Combination of Guanines in RNA G-Quadruplex Formation. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4790–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, H.; Doherty, D.; O’Donnell, J.S. New Developments in von Willebrand Disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Yao, J.; Yi, H.; Huang, X.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z. To Unwind the Biological Knots: The DNA / RNA G-quadruplex Resolvase RHAU ( DHX36 ) in Development and Disease. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2022, 5, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Jin, H.; Huang, X.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, C.; Lai, J.C.; Nagamine, Y.; et al. Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Nkx2-5 by RHAU in Heart Development. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikura, K. Functions and Regulation of RNA Editing by ADAR Deaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhaki, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, W.; Lee, Y.; Gustafsson, Å.B.; Mentzer, R.M.; Gottlieb, R.A. Autophagy Is Required for Preconditioning by the Adenosine A1 Receptor-Selective Agonist CCPA. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; Chen, S.; Chow, E.Y.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, J.; Cai, M.; Shi, J.; Chan, T.; Tan, J.; Kwok, C.K. An RNA G-Quadruplex Structure within the ADAR 5′UTR Interacts with DHX36 Helicase to Regulate Translation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, C.J.; Schofield, J.P.R.; Houghton, S.D.; O’Kelly, I.; Vargas-Caballero, M.; Deinhardt, K.; Coldwell, M.J. A 5′ UTR GGN Repeat Controls Localisation and Translation of a Potassium Leak Channel mRNA through G-Quadruplex Formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 9822–9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, D.; Liu, J. RNA Helicase DHX9 Enables PBX1 mRNA Translation by Unfolding RNA G-Quadruplex in Melanoma. EJC Skin Cancer 2024, 2, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, G.; Pastor, F.; Rahman, N.; Wang, W.-H.; Zhang, Z.; Merle, P.; Hui, L.; Salvetti, A.; Durantel, D.; et al. RNA Helicase DDX5 Enables STAT1 mRNA Translation and Interferon Signalling in Hepatitis B Virus Replicating Hepatocytes. Gut 2022, 71, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Qi, Q.; Xiong, W.; Shen, W.; Zhang, K.; Fan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; et al. Unveiling a Potent Small Molecule Disruptor for RNA G-Quadruplexes Tougher Than DNA G-Quadruplex Disruption. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024, 19, 2032–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitteaux, J.; Lejault, P.; Wojciechowski, F.; Joubert, A.; Boudon, J.; Desbois, N.; Gros, C.P.; Hudson, R.H.E.; Boulé, J.-B.; Granzhan, A.; et al. Identifying G-Quadruplex-DNA-Disrupting Small Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12567–12577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Hu, D.; Dai, Y.; Jing, H.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Li, J. Discovery of A G-Quadruplex Unwinder That Unleashes the Translation of G-Quadruplex-Containing mRNA without Inducing DNA Damage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melko, M.; Bardoni, B. The Role of G-Quadruplex in RNA Metabolism: Involvement of FMRP and FMR2P. Biochimie 2010, 92, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Perreault, J.-P.; Topisirovic, I.; Richard, S. RNA G-Quadruplexes and Their Potential Regulatory Roles in Translation. Translation 2016, 4, e1244031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, N.; Polonskaia, A.; Darnell, J.C.; Darnell, R.B.; Patel, D.J.; Serganov, A. Crystal Structure Reveals Specific Recognition of a G-Quadruplex RNA by a β-Turn in the RGG Motif of FMRP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, C. The Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Binds Specifically to Its mRNA via a Purine Quartet Motif. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4803–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, L.; Mader, S.A.; Mihailescu, M.-R. Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Interactions with the Microtubule Associated Protein 1B RNA. RNA 2008, 14, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castets, M.; Schaeffer, C.; Bechara, E.; Schenck, A.; Khandjian, E.W.; Luche, S.; Moine, H.; Rabilloud, T.; Mandel, J.-L.; Bardoni, B. FMRP Interferes with the Rac1 Pathway and Controls Actin Cytoskeleton Dynamics in Murine Fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pany, S.P.P.; Sapra, M.; Sharma, J.; Dhamodharan, V.; Patankar, S.; Pradeepkumar, P.I. Presence of Potential G-Quadruplex RNA-Forming Motifs at the 5′-UTR of PP2Acα mRNA Repress Translation. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 2955–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAninch, D.S.; Heinaman, A.M.; Lang, C.N.; Moss, K.R.; Bassell, G.J.; Rita Mihailescu, M.; Evans, T.L. Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Recognizes a G Quadruplex Structure within the Survival Motor Neuron Domain Containing 1 mRNA 5′-UTR. Mol. Biosyst. 2017, 13, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fähling, M.; Mrowka, R.; Steege, A.; Kirschner, K.M.; Benko, E.; Förstera, B.; Persson, P.B.; Thiele, B.J.; Meier, J.C.; Scholz, H. Translational Regulation of the Human Achaete-Scute Homologue-1 by Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 4255–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, P.; Marsico, G.; Herdy, B.; Ghanbarian, A.; Portella, G.; Balasubramanian, S. RNA G-Quadruplexes at Upstream Open Reading Frames Cause DHX36- and DHX9-Dependent Translation of Human mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.R.; Glineburg, M.R.; Moore, C.; Tani, N.; Jaiswal, R.; Zou, Y.; Aube, E.; Gillaspie, S.; Thornton, M.; Cecil, A.; et al. Human Oncoprotein 5MP Suppresses General and Repeat-Associated Non-AUG Translation via eIF3 by a Common Mechanism. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, C.J.F.; Asano, K. Between Order and Chaos: Understanding the Mechanism and Pathology of RAN Translation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 46, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.-J.; Krans, A.; Malik, I.; Deng, X.; Yildirim, E.; Ovunc, S.; Tank, E.M.H.; Jansen-West, K.; Kaufhold, R.; Gomez, N.B.; et al. Ribosomal Quality Control Factors Inhibit Repeat-Associated Non-AUG Translation from GC-Rich Repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 5928–5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.E.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Monroe, J.; Xing, J.; Krans, A.; Flores, B.N.; Barsur, V.; Ivanova, M.I.; Koutmou, K.S.; Barmada, S.J.; et al. CGG Repeats Trigger Translational Frameshifts That Generate Aggregation-Prone Chimeric Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 8674–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-F.; Ursu, A.; Childs-Disney, J.L.; Guertler, R.; Yang, W.-Y.; Bernat, V.; Rzuczek, S.G.; Fuerst, R.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gendron, T.F.; et al. The Hairpin Form of r(G4C2)Exp in c9ALS/FTD Is Repeat-Associated Non-ATG Translated and a Target for Bioactive Small Molecules. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 179–190.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateb, S.; Weisman-Shomer, P.; Hershco-Shani, I.; Ludwig, A.L.; Fry, M. The Tetraplex (CGG)n Destabilizing Proteins hnRNP A2 and CBF-A Enhance the in Vivo Translation of Fragile X Premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 5775–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumwalt, M.; Ludwig, A.; Hagerman, P.J.; Dieckmann, T. Secondary Structure and Dynamics of the r(CGG) Repeat in the mRNA of the Fragile X Mental Retardation 1 (FMR1) Gene. RNA Biol. 2007, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofer, N.; Weisman-Shomer, P.; Shklover, J.; Fry, M. The Quadruplex r(CGG)n Destabilizing Cationic Porphyrin TMPyP4 Cooperates with hnRNPs to Increase the Translation Efficiency of Fragile X Premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 2712–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

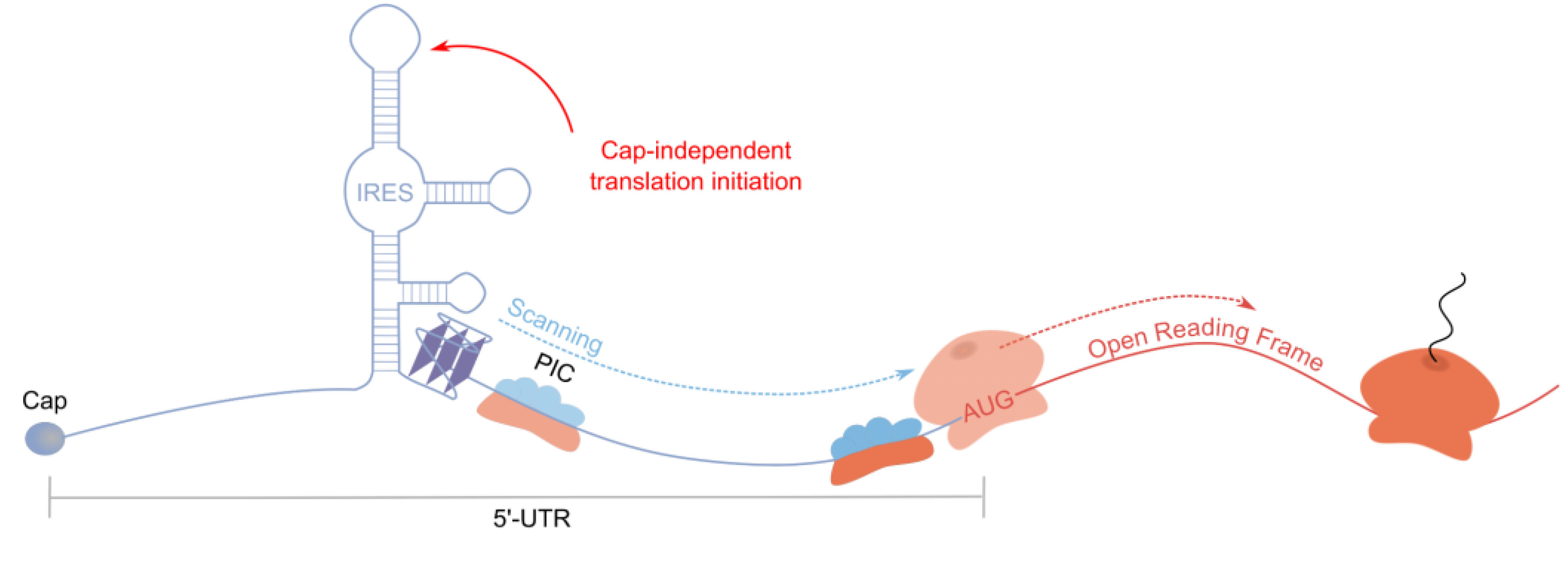

- Hoque, M.E.; Mahendran, T.; Basu, S. Reversal of G-Quadruplexes’ Role in Translation Control When Present in the Context of an IRES. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Jackson, N.L.; Shcherbakov, O.D.; Choi, H.; Blume, S.W. The Human IGF1R IRES Likely Operates through a Shine–Dalgarno-like Interaction with the G961 Loop (E-site) of the 18S rRNA and Is Kinetically Modulated by a Naturally Polymorphic polyU Loop. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 110, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Diamond, P.; Basu, S. An Independently Folding RNA G-Quadruplex Domain Directly Recruits the 40S Ribosomal Subunit. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 1879–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodoin, R.; Carrier, J.C.; Rivard, N.; Bisaillon, M.; Perreault, J.-P. G-Quadruplex Located in the 5′UTR of the BAG-1 mRNA Affects Both Its Cap-Dependent and Cap-Independent Translation through Global Secondary Structure Maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 10247–10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zeer, M.A.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Von Hacht, A.; Kreuzmann, D.; Röhrs, V.; Kurreck, J. Alternatively Spliced Variants of the 5’-UTR of the ARPC2 mRNA Regulate Translation by an Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) Harboring a Guanine-Quadruplex Motif. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnal, S.; Schaeffer, C.; Créancier, L.; Clamens, S.; Moine, H.; Prats, A.-C.; Vagner, S. A Single Internal Ribosome Entry Site Containing a G Quartet RNA Structure Drives Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Gene Expression at Four Alternative Translation Initiation Codons. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39330–39336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiin Von Hövel, F.; Kefalakes, E.; Grothe, C. What Can We Learn from FGF-2 Isoform-Specific Mouse Mutants? Differential Insights into FGF-2 Physiology In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.J.; Negishi, Y.; Pazsint, C.; Schonhoft, J.D.; Basu, S. An RNA G-Quadruplex Is Essential for Cap-Independent Translation Initiation in Human VEGF IRES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 17831–17839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammas, A.; Dubrac, A.; Morel, B.; Lamaa, A.; Touriol, C.; Teulade-Fichou, M.-P.; Prats, H.; Millevoi, S. Stabilization of the G-Quadruplex at the VEGF IRES Represses Cap-Independent Translation. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lv, Z.; Ge, L.; Xie, G.; Deng, G.; Rui, Y.; et al. N6 -Methyladenosine Promotes Translation of VEGFA to Accelerate Angiogenesis in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 2208–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.C.; Zhang, J.; Strom, J.; Yang, D.; Dinh, T.N.; Kappeler, K.; Chen, Q.M. G-Quadruplex in the NRF2 mRNA 5′ Untranslated Region Regulates De Novo NRF2 Protein Translation under Oxidative Stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37, e00122–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, J.W.; Willis, D.E. G-quadruplex Regulation of Neural Gene Expression. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 3284–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouraki, P.; Doxakis, E. Constitutive Translation of Human α-Synuclein Is Mediated by the 5′-Untranslated Region. Open Biol. 2016, 6, 160022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, P.; Pandey, S.; Mapa, K.; Maiti, S. The G-Quadruplex Augments Translation in the 5′ Untranslated Region of Transforming Growth Factor Β2. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwala, P.; Pandey, S.; Ekka, M.K.; Chakraborty, D.; Maiti, S. Combinatorial Role of Two G-Quadruplexes in 5′ UTR of Transforming Growth Factor Β2 (TGFβ2). Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 129416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha Roy, A.; Majumder, S.; Saha, P. Stable RNA G-Quadruplex in the 5′-UTR of Human cIAP1 mRNA Promotes Translation in an IRES-Independent Manner. Biochemistry 2024, acs.biochem.3c00521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, J.L.; Balasubramanian, S. Prevalence of Quadruplexes in the Human Genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2908–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martadinata, H.; Phan, A.T. Formation of a Stacked Dimeric G-Quadruplex Containing Bulges by the 5′-Terminal Region of Human Telomerase RNA (hTERC). Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, J.-D.; Jodoin, R.; Perreault, J.-P. New Scoring System to Identify RNA G-Quadruplex Folding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Matsugami, A.; Katahira, M.; Uesugi, S. A Dimeric RNA Quadruplex Architecture Comprised of Two G:G(:A):G:G(:A) Hexads, G:G:G:G Tetrads and UUUU Loops. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 322, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratta, P.; Mizielinska, S.; Nicoll, A.J.; Zloh, M.; Fisher, E.M.C.; Parkinson, G.; Isaacs, A.M. C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Repeat Associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia Forms RNA G-Quadruplexes. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolduc, F.; Garant, J.-M.; Allard, F.; Perreault, J.-P. Irregular G-Quadruplexes Found in the Untranslated Regions of Human mRNAs Influence Translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 21751–21760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskiewicz, J.; Sarzynska, J.; Szachniuk, M. How Bioinformatics Resources Work with G4 RNAs. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doluca, O. G4Catchall: A G-Quadruplex Prediction Approach Considering Atypical Features. J. Theor. Biol. 2019, 463, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garant, J.-M.; Perreault, J.-P.; Scott, M.S. Motif Independent Identification of Potential RNA G-Quadruplexes by G4RNA Screener. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3532–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagirici, H.B.; Budak, H.; Sen, T.Z. G4Boost: A Machine Learning-Based Tool for Quadruplex Identification and Stability Prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasi, R.; Marbiah, M.M.; Siciliano, V.; Polizzi, K.; Ceroni, F. A Call for Caution in Analysing Mammalian Co-Transfection Experiments and Implications of Resource Competition in Data Misinterpretation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, T.; Cella, F.; Tedeschi, F.; Gutiérrez, J.; Stan, G.-B.; Khammash, M.; Siciliano, V. Characterization and Mitigation of Gene Expression Burden in Mammalian Cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Shumate, A.; Pertea, G.; Varabyou, A.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Chang, Y.-C.; Madugundu, A.K.; Pandey, A.; Salzberg, S.L. CHESS: A New Human Gene Catalog Curated from Thousands of Large-Scale RNA Sequencing Experiments Reveals Extensive Transcriptional Noise. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batut, P.; Dobin, A.; Plessy, C.; Carninci, P.; Gingeras, T.R. High-Fidelity Promoter Profiling Reveals Widespread Alternative Promoter Usage and Transposon-Driven Developmental Gene Expression. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RGASP Consortium; Steijger, T.; Abril, J.F.; Engström, P.G.; Kokocinski, F.; Hubbard, T.J.; Guigó, R.; Harrow, J.; Bertone, P. Assessment of Transcript Reconstruction Methods for RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Function | Methods used for verification of rG4s /theirs effect on translation | rG4’s effect on translation, fold change versus mutant | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRAS | Membrane protein regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, associated with somatic rectal cancer, follicular thyroid cancer, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia | UV-melting (Tm=63℃ at 1 mM KCl)/ in vitro translation | 3.6 1 | [13] |

| ZIC-1 | Transcription factor regulating cerebellar development, overexpressed in medulloblastoma | UV-melting (Tm=79℃ at 25 mM KCl)/DLR, western blotting | 52 | [14] |

| ESR1 | Transcription factor, regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, upregulated in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers | CD-melting (Tm>85℃ at 100 mM KCl)/in vitro translation | 61 | [20] |

| TRF2 | Component of the telomere nucleoprotein shelterin complex, overexpressed in liver hepatocarcinomas, breast carcinomas and lung carcinomas | UV-melting (Tm=62℃ at 1 mM KCl)/ western blotting | 2.453 | [18] |

| CCND3 | Cyclin regulating the G0/G1 to S phase transition, overexpressed in myeloma, melanoma and mature B-cell malignancies | CD-melting (Tm=73℃ at 1 mM KCl), RNase T1/western blotting | 22 | [21] |

| BCL-2 | Integral outer mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks apoptosis and associated with follicular lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphoma | UV-melting (Tm=81℃ at 50 mM KCl)/ DLR, in vitro translation, western blotting | 3.51, 1.4-1.92 | [22,23] |

| ADAM10 | ɑ-Secretase of a disintegrin and metalloproteases family with anti-amyloidogenic activity | CD-melting (Tm=60℃ at 1 mM KCl)/ DLR, in vitro translation, western blotting | 31,2, 9-153 | [24] |

| MT3-MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase degrading extracellular matrix proteins, associated with invasiveness of gastric cancer, prostate cancer or renal carcinoma | CD-melting (Tm=72℃ at 1 mM KCl), RNase T1/ DLR | 2.22 | [25] |

| EBAG9 | Activator of apoptotic protease, associated with cervical adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer | in-line probing/DLR | 1.82 | [26] |

| FZD2 | Transmembrane receptor coupled to the beta-catenin canonical signaling pathway, associated with omodysplasia, Robinow Syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma | in-line probing/DLR | 2.52 | [26] |

| BARHL1 | Transcription factor involved in midbrain development/neuron migration, associted with triple-receptor negative breast cancer and medulloblastoma | in-line probing/DLR | 1.92 | [26] |

| NCAM2 | Membrane protein regulating cell adhesion/neuron adhesion, associated with epilepsy, familial temporal lobe and lissencephaly | in-line probing/DLR | 1.62 | [26] |

| THRA | Thyroid hormone receptor, associated with hypothyroidism, congenital, nongoitrous, and resistance to thyroid hormone | in-line probing/DLR | 1.62 | [26] |

| AASDHPPT | Phosphopantetheinyl transferase, associated with Pipecolic Acidemia and Lissencephaly | in-line probing/DLR | 2.22 | [26] |

| AKTIP | Protein interacting with protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt and modulating its activity by enhancing the phosphorylation of PKB regulatory sites | UV-melting (Tm=79℃ at 1 mM KCl)/DLR | 1.32 | [27] |

| CTSB | Lysosomal cysteine proteinase involved in the proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) | UV-melting (Tm=68℃ at 1 mM KCl)/DLR | 1.42 | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).