Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

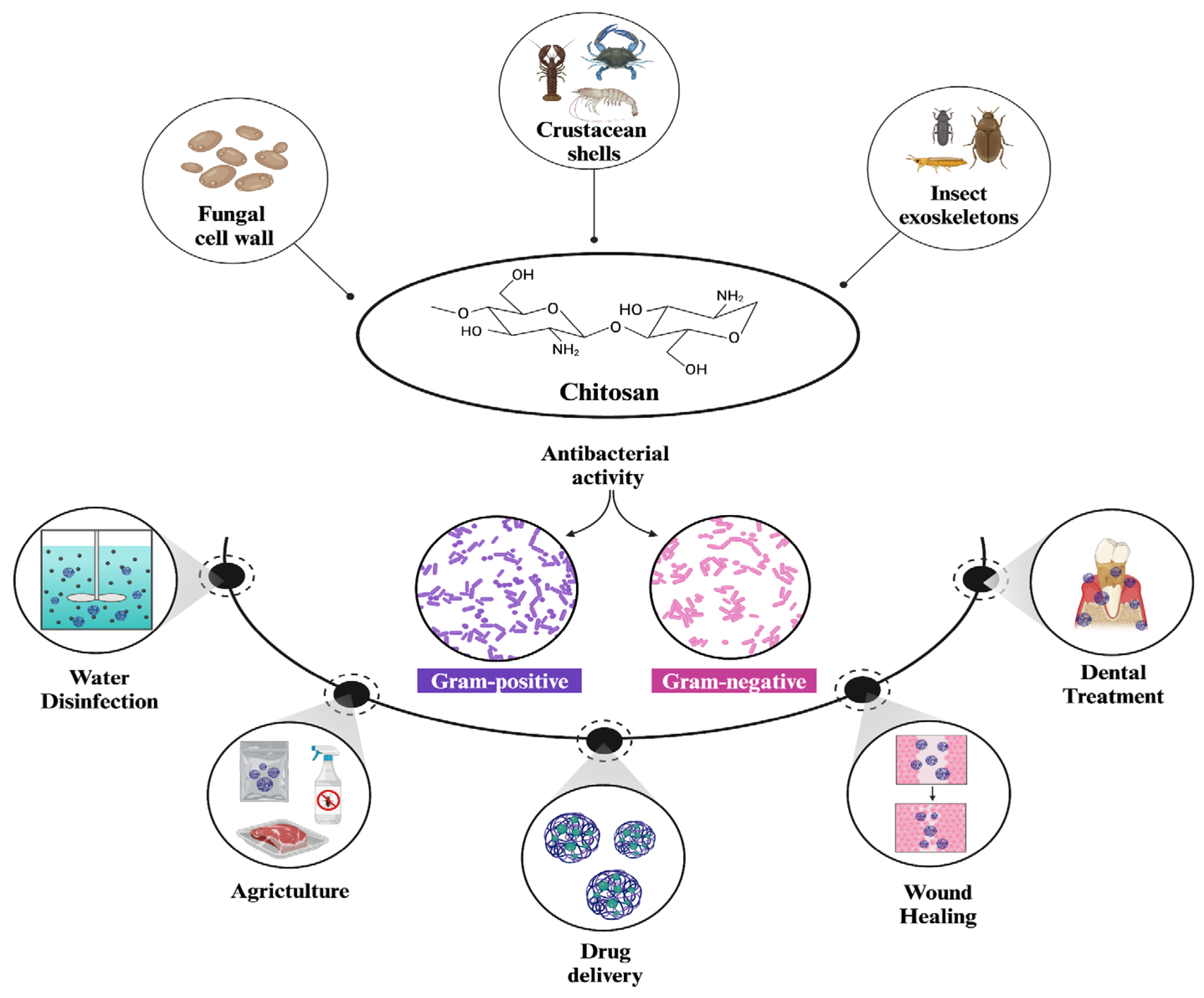

1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of Chitosan Nanoparticles

| Synthesis Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic gelation | The electrostatic interaction of a polyanion (such as TPP) with chitosan | Simple, mild, and eco-friendly | Limited particle size control; sensitive to ionic strength | [50] |

| Emulsion-Droplet Coalescence | NPs are formed in a water-oil system via solvent diffusion or evaporation. | Uniform particles, suitable for hydrophobic drugs | Requires organic solvents; time-consuming | [42] |

| Spray Drying | Chitosan solution atomization and solvent evaporation | Produces dry, stable powders; scalable | High-energy process; potential loss of bioactivity for sensitive molecules; large particle size | [48] |

| Self-Assembly | Chitosan molecules assembling spontaneously under some circumstances | No organic solvents; suitable for biomolecules | Sensitive to pH and ionic strength | [49] |

| Reverse Micellar Method | NPs generated in microemulsions of water and oil | Produces small, uniform particles | Complex process; use of organic solvents | [41] |

| Chemical Crosslinking | Crosslinked NPs are produced with substances like glutaraldehyde. | Produces stable NPs with tunable properties | Use of potentially toxic crosslinkers | [36] |

| Supercritical-CO2- assisted solubilization and atomization | Atomization | Solvent-free method; does not require additional separation process | Large particle size; time-consuming process. | [36] |

| Phase inversion precipitation | Precipitation | Suitable for large scale production, simple and cost effective | Requires organic solvent which can be toxic, limited control for particle size and morphology | [43] |

| Ionic gelation with radical polymerization | Polymerization and crosslinking | Precise control for particle size and morphology, suitable for drug delivery applications | Complex synthesis procedure, high cost | [46] |

| Top-down | Acid hydrolysis and deacetylation | Scalable for the industrial application, precise control for particle size and morphology | High energy consumption including harsh reaction conditions | [51] |

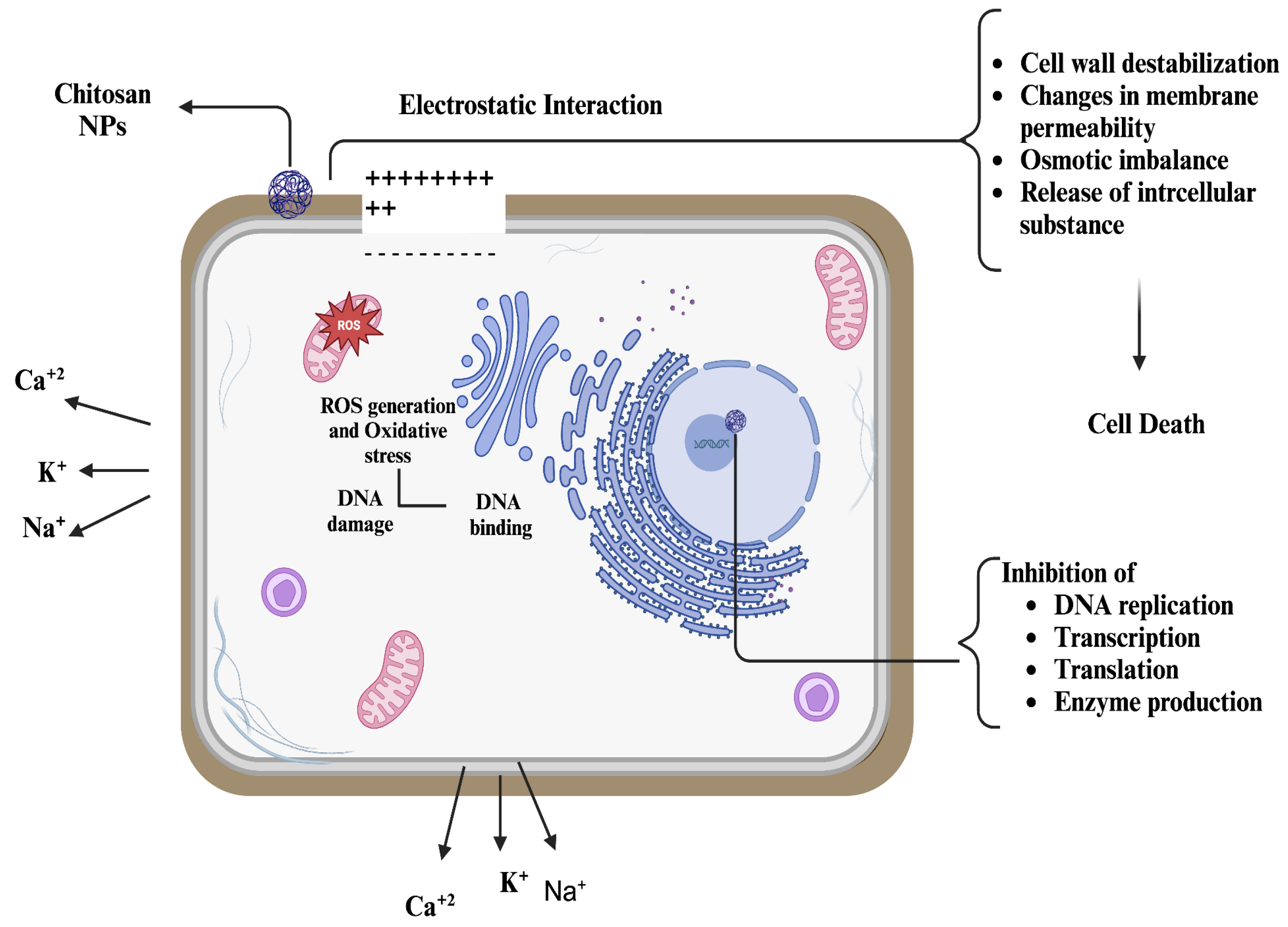

3. Antibacterial Mechanism of Chitosan Nanoparticles

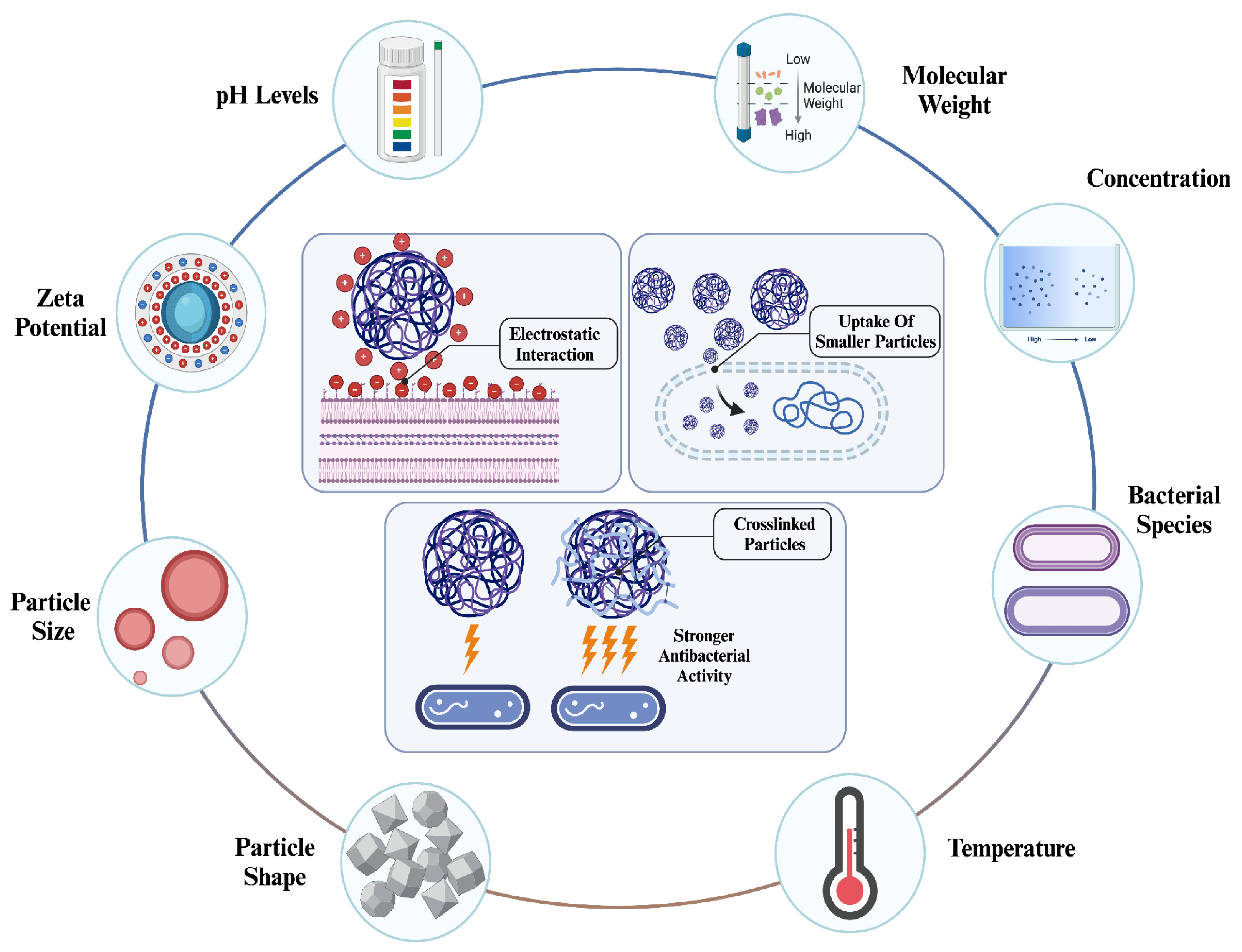

4. Effect of Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan and Chitosan NPs in Antibacterial Applications

4.1. Effect Of Surface Chemistry Of Chitosan NPs In Their Antibacterial Applications

4.1.1. Effect Of Crosslinking

4.1.2. Effect Of Surface Charge Density

4.2. Effect Of Physicochemical Property And Concentration Of Chitosan NPs On Nanocomplex-based Antibacterial Applications

5. Antibacterial Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles

5.1. Antibacterial Applications of Chitosan and Chitosan NPs with Drug Delivery Systems

5.2. Antibacterial Application of Chitosan and Chitosan NPs in Agriculture

5.3. Chitosan NPs in Water Disinfection

5.4. Chitosan Nanoparticles in Wound Healing Applications

5.5. Chitosan Nanoparticles in Dental Applications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terkula Iber, B.; Azman Kasan, N.; Torsabo, D.; Wese Omuwa, J. A Review of Various Sources of Chitin and Chitosan in Nature. Journal of Renewable Materials 2022, 10, 1097–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Sánchez-González, L.; Cháfer, M.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Edible Chitosan Coatings for Fresh and Minimally Processed Foods. In Emerging Food Packaging Technologies; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 66–95 ISBN 978-1-84569-809-6.

- Sharkawy, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Rodrigues, A.E. Chitosan-Based Pickering Emulsions and Their Applications: A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 250, 116885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Bhuiyan, M.A.R.; Islam, M.N. Chitin and Chitosan: Structure, Properties and Applications in Biomedical Engineering. J Polym Environ 2017, 25, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. (Gabriel); Peters, L.M.; Mucalo, M.R. Chitosan: A Review of Sources and Preparation Methods. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 169, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmana, M.; Mahmood, S.; Hilles, A.R.; Rahman, A.; Arifin, M.A.B.; Ahmed, S. A Review on Chitosan and Chitosan-Based Bionanocomposites: Promising Material for Combatting Global Issues and Its Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 185, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, M.C.M.; Martins, I.M.; Sobral, A.J.F.N. Role of Chitosan and Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles against Heavy Metal Stress in Plants. In Role of Chitosan and Chitosan-Based Nanomaterials in Plant Sciences; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 273–296 ISBN 978-0-323-85391-0.

- Xing, K.; Li, T.J.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.Q.; Li, X.Y.; Miao, X.M.; Feng, Z.Z.; Peng, X.; et al. Antifungal and Eliciting Properties of Chitosan against Ceratocystis Fimbriata in Sweet Potato. Food Chemistry 2018, 268, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamjumphol, W.; Chareonsudjai, P.; Chareonsudjai, S. Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan against Burkholderia Pseudomallei. MicrobiologyOpen 2018, 7, e00534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, Z.; Ridwanto, R.; Nasution, H.M.; Kaban, V.E.; Nasri, N.; Karo, N.B. Antibacterial Activity of Freshwater Lobster (Cherax Quadricarinatus) Shell Chitosan Gel Preparation against Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus. J App Pharm Sc 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, F.; Wang, X.; Feng, T.; Xia, S.; Zhang, X. Chitosan Decoration Improves the Rapid and Long-Term Antibacterial Activities of Cinnamaldehyde-Loaded Liposomes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 168, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Jisha, M.S. Chitosan Nanoparticles Preparation and Applications. Environ Chem Lett 2018, 16, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticles: From Classification to Application and Toxicity. Molecules 2024, 29, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Silver Nanoparticles in Therapeutics and Beyond: A Review of Mechanism Insights and Applications. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Duman, H.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Gold Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine: Unique Properties and Therapeutic Potential. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Silver Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis Methods and Chemical and Physical Properties. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Eker, F.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Gold Nanoparticles: Multifunctional Properties, Synthesis, and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasaj, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Asghari, B.; Ahmadieh-Yazdi, A.; Asgari, M.; Kabiri-Samani, S.; Sharifi, E.; Arabestani, M. Factors Influencing the Antimicrobial Mechanism of Chitosan Action and Its Derivatives: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 277, 134321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreras, U.S.; Méndez, F.T.; Martínez, R.E.M.; Valencia, C.S.; Rodríguez, P.R.M.; Rodríguez, J.P.L. Chitosan Nanoparticles Enhance the Antibacterial Activity of Chlorhexidine in Collagen Membranes Used for Periapical Guided Tissue Regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2016, 58, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, A.; Kishen, A. The Effect of Tissue Inhibitors on the Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Photodynamic Therapy. Journal of Endodontics 2012, 38, 1275–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mageshwaran, V.; Sivasubramanian, P.; Kumar, P.; Nagaraju, Y. Antibacterial Response of Nanostructured Chitosan Hybrid Materials. In Chitosan Nanocomposites; Swain, S.K., Biswal, A., Eds.; Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 161–179. ISBN 978-981-19964-5-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kongkaoroptham, P.; Piroonpan, T.; Pasanphan, W. Chitosan Nanoparticles Based on Their Derivatives as Antioxidant and Antibacterial Additives for Active Bioplastic Packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 257, 117610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarfaj, A. Preparation, Characterization and Antibacterial Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles against Food Spoilage Bacteria. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2019, 13, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Chitosan-Based Biodegradable Functional Films for Food Packaging Applications. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2020, 62, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavand, F.; Cacciotti, I.; Vahedikia, N.; Rehman, A.; Tarhan, Ö.; Akbari-Alavijeh, S.; Shaddel, R.; Rashidinejad, A.; Nejatian, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on the Nanocomposites Loaded with Chitosan Nanoparticles for Food Packaging. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 1383–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, B.; Bharatiya, D.; Purohit, S.S.; Swain, S.K. Chitosan-Based Nano Biomaterials and Their Applications in Dentistry. In Chitosan Nanocomposites; Swain, S.K., Biswal, A., Eds.; Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 325–348. ISBN 978-981-19964-5-0. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, G.; Zambom, C.; Siqueira, W.L. Nanoparticles in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, H.L.; Goh, B.H.; Lee, L.-H.; Chuah, L.H. Application of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles in Skin Wound Healing. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 17, 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, S.; Rastegari, A.; Mohammadi, Z.; Nazari, M.; Yousefi, M.; Samadi, F.Y.; Najafzadeh, S.; Aghsami, M. Chitosan Nanoparticle Loaded by Epidermal Growth Factor as a Potential Protein Carrier for Wound Healing: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. IET Nanobiotechnology 2023, 17, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehterami, A.; Salehi, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Vaez, A.; Samadian, H.; Sahrapeyma, H.; Mirzaii, M.; Ghorbani, S.; Goodarzi, A. In Vitro and in Vivo Study of PCL/COLL Wound Dressing Loaded with Insulin-Chitosan Nanoparticles on Cutaneous Wound Healing in Rats Model. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 117, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, F.K.; Salama, A.; Ali, S.I.; El-Hashemy, H.A. Dunaliella Salina Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Promising Wound Healing Vehicles: In-Vitro and in-Vivo Study. OpenNano 2023, 12, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benettayeb, A.; Seihoub, F.Z.; Pal, P.; Ghosh, S.; Usman, M.; Chia, C.H.; Usman, M.; Sillanpää, M. Chitosan Nanoparticles as Potential Nano-Sorbent for Removal of Toxic Environmental Pollutants. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Abd El-latif, M.B.; Mahmoud, A.; Diaa, D.; Kamal, G.; Mahmoud, H.; Emad, M.; Hany, M.; Hany, R.; Mohamed, S.; et al. Utilization of Ziziphus Spina-Christi Leaf Extract-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment and Their Impact on Animal Health. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 282, 137441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohya, Y.; Shiratani, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Ouchi, T. Release Behavior of 5-Fluorouracil from Chitosan-Gel Nanospheres Immobilizing 5-Fluorouracil Coated with Polysaccharides and Their Cell Specific Cytotoxicity. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 1994, 31, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanat, M.; Schroën, K. Preparation Methods and Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles; with an Outlook toward Reinforcement of Biodegradable Packaging. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 161, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shabouri, M.H. Positively Charged Nanoparticles for Improving the Oral Bioavailability of Cyclosporin-A. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2002, 249, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, T.; Takeuchi, H.; Hino, T.; Kunou, N.; Kawashima, Y. Preparations of Biodegradable Nanospheres of Water-Soluble and Insoluble Drugs with D,L-Lactide/Glycolide Copolymer by a Novel Spontaneous Emulsification Solvent Diffusion Method, and the Drug Release Behavior. Journal of Controlled Release 1993, 25, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Huang, J.; Ding, L.; Li, M.; Chen, Z. Preparation of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles and Immobilization of Laccase. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mat. Sci. Edit. 2009, 24, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-M.; Shi, L.-E.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Chen, J.-M.; Shi, D.-D.; Yang, J.; Tang, Z.-X. Preparation and Application of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Nanofibers. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 28, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafshgari, M.H.; Khorram, M.; Mansouri, M.; Samimi, A.; Osfouri, S. Preparation of Alginate and Chitosan Nanoparticles Using a New Reverse Micellar System. Iran Polym J 2012, 21, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumitsu, H.; Ichikawa, H.; Fukumori, Y. Chitosan-Gadopentetic Acid Complex Nanoparticles for Gadolinium Neutron-Capture Therapy of Cancer: Preparation by Novel Emulsion-Droplet Coalescence Technique and Characterization. Pharmaceutical Research 1999, 16, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenha, A. Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Survey of Preparation Methods. Journal of Drug Targeting 2012, 20, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonassen, H.; Kjøniksen, A.-L.; Hiorth, M. Stability of Chitosan Nanoparticles Cross-Linked with Tripolyphosphate. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3747–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, P.; Remunan-Lopez, C.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Alonso, M.J. Novel Hydrophilic Chitosan-Polyethylene Oxide Nanoparticles as Protein Carriers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 63, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeesh, S.; Sharma, C.P. Novel pH Responsive Polymethacrylic Acid–Chitosan–Polyethylene Glycol Nanoparticles for Oral Peptide Delivery. J Biomed Mater Res 2006, 76B, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ding, Y.; Ge, H.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan–Poly(Acrylic Acid) Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 3193–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, L.T.K.; Wang, S.-L.; Hiep, Đ.M.; Luong, P.M.; Vui, N.T.; Đinh, T.M.; Dzung, N.A. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles by Spray Drying, and Their Antibacterial Activity. Res Chem Intermed 2014, 40, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, J.P.; Peniche, H.; Peniche, C. Chitosan Based Self-Assembled Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery. Polymers 2018, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Yan, W.; Xu, Z.; Ni, H. Formation Mechanism of Monodisperse, Low Molecular Weight Chitosan Nanoparticles by Ionic Gelation Technique. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2012, 90, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesena, R.N.; Tissera, N.; Kannangara, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.; Amaratunga, G.A.J.; De Silva, K.M.N. A Method for Top down Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Nanofibers. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 117, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, N.; Rodier, E.; Letourneau, J.-J.; Louati, H.; Sauceau, M.; Le Moigne, N.; Benezet, J.-C.; Fages, J. Chitosan Nanoparticles Generation Using CO2 Assisted Processes. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2014, 95, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, S.S.; Bora, R.S.; Al-Garni, S.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2021, 35, 1874–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, D.; Von Bargen, K.; Haas, A.; Sahl, H.-G. Insights into the Mode of Action of Chitosan as an Antibacterial Compound. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 3764–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- No, H. Antibacterial Activity of Chitosans and Chitosan Oligomers with Different Molecular Weights. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2002, 74, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Shen, D.; Xu, W. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activities of Quaternary Ammonium Salt of Chitosan. Carbohydrate Research 2001, 333, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, G.-J.; Su, W.-H. Antibacterial Activity of Shrimp Chitosan against Escherichia Coli. Journal of Food Protection 1999, 62, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudarshan, N.R.; Hoover, D.G.; Knorr, D. Antibacterial Action of Chitosan. Food Biotechnology 1992, 6, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Kim, K.; Chun, S. Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Review. Processes 2020, 8, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, F.; Lam, H.; De Pedro, M.A.; Waldor, M.K. Emerging Knowledge of Regulatory Roles of D-Amino Acids in Bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahlawy, K.; Elbendary, M.; Elhendawy, A.; Hudson, S. The Antimicrobial Activity of Cotton Fabrics Treated with Different Crosslinking Agents and Chitosan. Carbohydrate Polymers 2005, 60, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Jeong, K.C. Application, Mode of Action, and in Vivo Activity of Chitosan and Its Micro- and Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 176, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preparation and Evaluation of Chitosan-Tripolyphosphate Nanoparticles Suspension as an Antibacterial Agent. J App Pharm Sci 2018, 8, 147–156. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Qian, J.; Fan, J.; Guo, H.; Gou, L.; Yang, H.; Liang, C. Preparation Nanoparticle by Ionic Cross-Linked Emulsified Chitosan and Its Antibacterial Activity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2019, 568, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritchenkov, A.S.; Egorov, A.R.; Artemjev, A.A.; Kritchenkov, I.S.; Volkova, O.V.; Kurliuk, A.V.; Shakola, T.V.; Rubanik, V.V.; Rubanik, V.V.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; et al. Ultrasound-Assisted Catalyst-Free Thiol-Yne Click Reaction in Chitosan Chemistry: Antibacterial and Transfection Activity of Novel Cationic Chitosan Derivatives and Their Based Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 143, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritchenkov, A.S.; Egorov, A.R.; Artemjev, A.A.; Kritchenkov, I.S.; Volkova, O.V.; Kiprushkina, E.I.; Zabodalova, L.A.; Suchkova, E.P.; Yagafarov, N.Z.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; et al. Novel Heterocyclic Chitosan Derivatives and Their Derived Nanoparticles: Catalytic and Antibacterial Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 149, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadkari, R.R.; Suwalka, S.; Yogi, M.R.; Ali, W.; Das, A.; Alagirusamy, R. Green Synthesis of Chitosan-Cinnamaldehyde Cross-Linked Nanoparticles: Characterization and Antibacterial Activity. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 226, 115298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, R.; Sharrouf, W.; Selting, K. Physical Properties of Nanoparticles That Result in Improved Cancer Targeting. Journal of Oncology 2020, 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Guan, J.; Qin, L.; Zhang, X.; Mao, S. Physicochemical Properties Affecting the Fate of Nanoparticles in Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoudho, K.N.; Uddin, S.; Rumon, M.M.H.; Shakil, M.S. Influence of Physicochemical Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Their Antibacterial Activity. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 33303–33334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasilewska, A.; Klekotka, U.; Zambrzycka, M.; Zambrowski, G.; Święcicka, I.; Kalska-Szostko, B. Physico-Chemical Properties and Antimicrobial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Green Synthesis. Food Chemistry 2023, 400, 133960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabourian, P.; Yazdani, G.; Ashraf, S.S.; Frounchi, M.; Mashayekhan, S.; Kiani, S.; Kakkar, A. Effect of Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticles on Their Intracellular Uptake. IJMS 2020, 21, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, M.; Jafari, S.M. Evaluation of Different Factors Affecting Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 85, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, A.; Almotairy, A.R.Z.; Henidi, H.; Alshehri, O.Y.; Aldughaim, M.S. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of the Implication of Nanoparticles’ Physicochemical Properties on Responses in Biological Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.R.; Peixoto, D.; Costa, R.R.; Franco, A.R.; Castro, V.I.B.; Pires, R.A.; Reis, R.L.; Pashkuleva, I.; Maniglio, D.; Tirella, A.; et al. Antibacterial Properties of Photo-Crosslinked Chitosan/Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles Loaded with Bacitracin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 277, 134250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminava, F.; Javanbakht, S.; Zabihi, M.; Abbaszadeh, M.; Fakhrzadeh, V.; Kafil, H.S.; Ahmadian, Z.; Joulaei, M.; Zahed, Z.; Motavalizadehkakhky, A.; et al. Crosslinking Chitosan with Silver-Sulfur Doped Graphene Quantum Dots: An Efficient Antibacterial Nanocomposite Hydrogel Films. J Polym Environ 2024, 32, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Zhi, X.; Du, B.; Yuan, S. Preparation of Elastic and Antibacterial Chitosan–Citric Membranes with High Oxygen Barrier Ability by in Situ Cross-Linking. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Radinekiyan, F.; Aliabadi, H.A.M.; Sukhtezari, S.; Tahmasebi, B.; Maleki, A.; Madanchi, H. Chitosan Hydrogel/Silk Fibroin/Mg(OH)2 Nanobiocomposite as a Novel Scaffold with Antimicrobial Activity and Improved Mechanical Properties. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.A.M.; Grinholc, M.; Dena, A.S.A.; El-Sherbiny, I.M.; Megahed, M. Boosting the Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan–Gold Nanoparticles against Antibiotic–Resistant Bacteria by Punicagranatum L. Extract. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 256, 117498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derakhshan-sefidi, M.; Bakhshi, B.; Rasekhi, A. Thiolated Chitosan Nanoparticles Encapsulated Nisin and Selenium: Antimicrobial/Antibiofilm/Anti-Attachment/Immunomodulatory Multi-Functional Agent. BMC Microbiol 2024, 24, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.A.; Alminderej, F.M.; Al-Harby, N.F.; Elmehbad, N.Y.; Mohamed, N.A. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of Novel Bis-Uracil Chitosan Hydrogels Modified with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Boosting Their Antimicrobial Activity. Polymers 2023, 15, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatin, S.; Maleki Dizaj, S.; Yari Khosroushahi, A. Effect of the Surface Modification, Size, and Shape on Cellular Uptake of Nanoparticles. Cell Biology International 2015, 39, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaymaz, S.V.; Nobar, H.M.; Sarıgül, H.; Soylukan, C.; Akyüz, L.; Yüce, M. Nanomaterial Surface Modification Toolkit: Principles, Components, Recipes, and Applications. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 322, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, R.M.; Dmour, I.; Taha, M.O. Stable Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles Using Polyphosphoric Acid or Hexametaphosphate for Tandem Ionotropic/Covalent Crosslinking and Subsequent Investigation as Novel Vehicles for Drug Delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Wei, Y.; Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Yuan, F.; Mao, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.; et al. Impact of Different Crosslinking Agents on Functional Properties of Curcumin-Loaded Gliadin-Chitosan Composite Nanoparticles. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 112, 106258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnicourt, L.; Ladavière, C. Interests of Chitosan Nanoparticles Ionically Cross-Linked with Tripolyphosphate for Biomedical Applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2016, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, J.; Liu, F.; Majeed, H.; Qi, J.; Yokoyama, W.; Zhong, F. Physicochemical and Morphological Properties of Size-Controlled Chitosan–Tripolyphosphate Nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2015, 465, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Qian, J.; Zhao, C.; Yang, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H. Study on the Relationship between Crosslinking Degree and Properties of TPP Crosslinked Chitosan Nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 241, 116349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoerunnisa, F.; Nurhayati, M.; Dara, F.; Rizki, R.; Nasir, M.; Aziz, H.A.; Hendrawan, H.; Poh, N.E.; Kaewsaneha, C.; Opaprakasit, P. Physicochemical Properties of TPP-Crosslinked Chitosan Nanoparticles as Potential Antibacterial Agents. Fibers Polym 2021, 22, 2954–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathoni, N.; Herdiana, Y.; Suhandi, C.; Mohammed, A.; El-Rayyes, A.; Narsa, A. Chitosan/Alginate-Based Nanoparticles for Antibacterial Agents Delivery. IJN 2024, Volume 19, 5021–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Z.; Qian, J.; Han, J.; Deng, X.; Shen, J.; Li, G.; Xie, Y. Comparison of Three Water-Soluble Polyphosphate Tripolyphosphate, Phytic Acid, and Sodium Hexametaphosphate as Crosslinking Agents in Chitosan Nanoparticle Formulation. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 230, 115577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, R.; Halder, J.; Rajwar, T.K.; Pradhan, D.; Dash, P.; Das, C.; Rai, V.K.; Kar, B.; Ghosh, G.; Rath, G. Design and Evaluation of Antibacterials Crosslinked Chitosan Nanoparticle as a Novel Carrier for the Delivery of Metronidazole to Treat Bacterial Vaginosis. Microbial Pathogenesis 2024, 186, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E. The Role of Surface Charge in Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Medical Nanoparticles. IJN 2012, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athavale, R.; Sapre, N.; Rale, V.; Tongaonkar, S.; Manna, G.; Kulkarni, A.; Shirolkar, M.M. Tuning the Surface Charge Properties of Chitosan Nanoparticles. Materials Letters 2022, 308, 131114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H.; Lin, H.-T.V.; Wu, G.-J.; Tsai, G.J. pH Effects on Solubility, Zeta Potential, and Correlation between Antibacterial Activity and Molecular Weight of Chitosan. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 134, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Wang, S.-L.; Vo, T.P.K.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles by TPP Ionic Gelation Combined with Spray Drying, and the Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles and a Chitosan Nanoparticle–Amoxicillin Complex. Res Chem Intermed 2017, 43, 3527–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, Z. The Effects of Ligand Valency and Density on the Targeting Ability of Multivalent Nanoparticles Based on Negatively Charged Chitosan Nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 161, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapre, N.; Gumathannavar, R.; Jadhav, Y.; Kulkarni, A.; Shirolkar, M.M. Effect of Ionic Strength on Porosity and Surface Charge of Chitosan Nanoparticles. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, S2214785322069401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dong, S.; Xu, W.; Tu, S.; Yan, L.; Zhao, C.; Ding, J.; Chen, X. Antibacterial Hydrogels. Advanced Science 2018, 5, 1700527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Tri, P.; Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, T.H.; Carriere, P. Antibacterial Behavior of Hybrid Nanoparticles. In Noble Metal-Metal Oxide Hybrid Nanoparticles; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 141–155 ISBN 978-0-12-814134-2.

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Luceño-Sánchez, J.A. Antibacterial Activity of Polymer Nanocomposites Incorporating Graphene and Its Derivatives: A State of Art. Polymers 2021, 13, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamady Hussein, M.A.; Baños, F.G.D.; Grinholc, M.; Abo Dena, A.S.; El-Sherbiny, I.M.; Megahed, M. Exploring the Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of Gold-Chitosan Hybrid Nanoparticles Composed of Varying Chitosan Amounts. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. ElS.; Mohamed, H.M.; Mohamed, M.I.; Kandile, N.G. Sustainable Antimicrobial Modified Chitosan and Its Nanoparticles Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaee, M.; Garavand, F.; Rehman, A.; Jafarazadeh, S.; Amini, E.; Cacciotti, I. Biodegradability, Physical, Mechanical and Antimicrobial Attributes of Starch Nanocomposites Containing Chitosan Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 195, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.M.; Ahmed Rather, G.; Patrício, A.; Haq, Z.; Sheikh, A.A.; Shah, M.Z.U.H.; Singh, H.; Khan, A.A.; Imtiyaz, S.; Ahmad, S.B.; et al. Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Versatile Platform for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Mehra, A.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, M.; Singh, M.; Panda, J.J. Lipopolysaccharide Targeting-Peptide-Capped Chitosan Gold Nanoparticles for Laser-Induced Antibacterial Activity. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 1913–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavand, F.; Rouhi, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Khodaei, D.; Cacciotti, I.; Zargar, M.; Razavi, S.H. Tuning the Physicochemical, Structural, and Antimicrobial Attributes of Whey-Based Poly (L-Lactic Acid) (PLLA) Films by Chitosan Nanoparticles. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 880520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardebilchi Marand, S.; Almasi, H.; Ardebilchi Marand, N. Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Incorporated with NiO Nanoparticles: Physicochemical, Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 190, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Fabrication of Chitosan-Based Functional Nanocomposite Films: Effect of Quercetin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 121, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Qi, M.; Sun, J.; Ai, M.; Ma, X.; Cai, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, L.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; et al. Preparation, Characterization and Wound Healing Effect of Vaccarin-Chitosan Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 165, 3169–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes Rocha Correa, V.; Assis Martins, J.; Ribeiro De Souza, T.; De Castro Nunes Rincon, G.; Pacheco Miguel, M.; Borges De Menezes, L.; Correa Amaral, A. Melatonin Loaded Lecithin-Chitosan Nanoparticles Improved the Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmaram, K.; Yazdian, F.; Pazhouhnia, Z.; Lotfibakhshaiesh, N. Preparation and Characterization of 3D Bioprinted Gelatin Methacrylate Hydrogel Incorporated with Curcumin Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for in Vivo Wound Healing Application. Biomaterials Advances 2024, 156, 213677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalini, T.; Basha, S.K.; Sadiq, A.M.; Kumari, V.S. In Vitro Cytocompatibility Assessment and Antibacterial Effects of Quercetin Encapsulated Alginate/Chitosan Nanoparticle. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 219, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, H.; Liu, J.; Liang, H. Chitosan Nanoparticles Efficiently Enhance the Dispersibility, Stability and Selective Antibacterial Activity of Insoluble Isoflavonoids. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 232, 123420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, T. Preparation, Characterization and Releasing Property of Antibacterial Nano-Capsules Composed of ε-PL-EGCG and Sodium Alginate-Chitosan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 204, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghiloo, S.; Ghajari, G.; Zand, Z.; Kabiri-Samani, S.; Kabiri, H.; Rajaei, N.; Piri-Gharaghie, T. Designing Alginate/Chitosan Nanoparticles Containing Echinacea Angustifolia : A Novel Candidate for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2023, 20, e202201008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, T.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Yan, J.; Xu, J. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Lysozyme Loaded Quaternary Ammonium Chitosan Nanoparticles Functionalized with Cellulose Nanocrystals. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 191, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, M.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Mohammadi, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Chitosan Nanoparticles Encapsulating Lemongrass (Cymbopogon Commutatus) Essential Oil: Physicochemical, Structural, Antimicrobial and in-Vitro Release Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 192, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, F.H.; Nurdiansyah; Salamah, U.; Sari, N.R.; Maddu, A.; Solikhin, A. Potential of Chitosan Hydrogel Based Activated Carbon Nanoparticles and Non-Activated Carbon Nanoparticles for Water Purification. Fibers Polym 2020, 21, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ranebennur, T.K.; Vasan, H.N. Study of Antibacterial Efficacy of Hybrid Chitosan-Silver Nanoparticles for Prevention of Specific Biofilm and Water Purification. International Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry 2011, 2011, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, A.S.; Syame, S.M.; Mohamed, W.S.; Hakim, A.S. Incorporation of Plant Extracted Hydroxyapatite and Chitosan Nanoparticles on the Surface of Orthodontic Micro-Implants: An In-Vitro Antibacterial Study. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharbaty, M.H.M.; Naji, G.A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the Potential of a Newly Developed Pectin-Chitosan Polyelectrolyte Composite on the Surface of Commercially Pure Titanium for Dental Implants. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K.; Qiu, X.; Ji, Q. The Effect of Doxycycline-Containing Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles on NLRP3 Inflammasome in Periodontal Disease. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 237, 116163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Y.; İnce, İ.; Gümüştaş, B.; Vardar, Ö.; Yakar, N.; Munjaković, H.; Özdemir, G.; Emingil, G. Development of Doxycycline and Atorvastatin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Local Delivery in Periodontal Disease. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 82, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiana, Y.; Wathoni, N.; Shamsuddin, S.; Muchtaridi, M. Drug Release Study of the Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgadir, M.A.; Uddin, Md.S.; Ferdosh, S.; Adam, A.; Chowdhury, A.J.K.; Sarker, Md.Z.I. Impact of Chitosan Composites and Chitosan Nanoparticle Composites on Various Drug Delivery Systems: A Review. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2015, 23, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current Advances in Chitosan Nanoparticles Based Drug Delivery and Targeting. Adv Pharm Bull 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gláucia-Silva, F.; Torres, J.V.P.; Torres-Rêgo, M.; Daniele-Silva, A.; Furtado, A.A.; Ferreira, S.D.S.; Chaves, G.M.; Xavier-Júnior, F.H.; Rocha Soares, K.S.; Silva-Júnior, A.A.D.; et al. Tityus Stigmurus-Venom-Loaded Cross-Linked Chitosan Nanoparticles Improve Antimicrobial Activity. IJMS 2024, 25, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yu, Y.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Yu, M.; Han, M.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, J. Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Eucommia Ulmoides Seed Essential Oil: Preparation, Characterization, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 257, 128820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Luo, C.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ruan, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Sun, T.; Li, N.; Han, L.; et al. Advances of Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems for Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. Chinese Chemical Letters 2023, 34, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmugam, A.; Abbishek, S.; Kumar, S.L.; Sairam, A.B.; Palem, V.V.; Kumar, R.S.; Almansour, A.I.; Arumugam, N.; Vikraman, D. Synthesis of Chitosan Based Reduced Graphene Oxide-CeO2 Nanocomposites for Drug Delivery and Antibacterial Applications. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2023, 145, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, A.-Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, C.-S.; Hsu, S. Antiviral and Antibacterial Sulfated Polysaccharide–Chitosan Nanocomposite Particles as a Drug Carrier. Molecules 2023, 28, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Meng, J.; Khan, Md.I.H.; Dai, L.; Khan, A.; An, X.; Zhang, J.; Huq, T.; Ni, Y. Chitosan as A Preservative for Fruits and Vegetables: A Review on Chemistry and Antimicrobial Properties. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2019, 4, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sree, K.P.; Sree, M.S.; Supriya, P.S. Application of Chitosan Edible Coating for Preservation of Tomato. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 3281–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.F.; Ghaderi, J.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C. Tailoring Physico-Mechanical and Antimicrobial/Antioxidant Properties of Biopolymeric Films by Cinnamaldehyde-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles and Their Application in Packaging of Fresh Rainbow Trout Fillets. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 124, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paomephan, P.; Assavanig, A.; Chaturongakul, S.; Cady, N.C.; Bergkvist, M.; Niamsiri, N. Insight into the Antibacterial Property of Chitosan Nanoparticles against Escherichia Coli and Salmonella Typhimurium and Their Application as Vegetable Wash Disinfectant. Food Control 2018, 86, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelatha, S.; Kumar, N.; Yin, T.S.; Rajani, S. Evaluating the Antibacterial Activity and Mode of Action of Thymol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Against Plant Bacterial Pathogen Xanthomonas Campestris Pv. Campestris. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 792737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairy, A.M.; Tohamy, M.R.A.; Zayed, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.F.; El-Tahan, A.M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Mesiha, P.K. Eco-Friendly Application of Nano-Chitosan for Controlling Potato and Tomato Bacterial Wilt. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 29, 2199–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.C.; Kumaraswamy, R.V.; Kumari, S.; Sharma, S.S.; Pal, A.; Raliya, R.; Biswas, P.; Saharan, V. Cu-Chitosan Nanoparticle Boost Defense Responses and Plant Growth in Maize (Zea Mays L.). Sci Rep 2017, 7, 9754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; He, J.; Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Bose, S.K.; Sun, Y.; Hu, J.; Yin, H. Effects of Chitosan Nanoparticles on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 126, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawale, K.S.; Giridhar, P. Chitosan Nanoparticles Modulate Plant Growth, and Yield, as Well as Thrips Infestation in Capsicum Spp. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 254, 127682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.M.; El-Shafei, A.A.; Elewa, M.M.; Moneer, A.A. Application of Silver-, Iron-, and Chitosan- Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment. Desalination and Water Treatment 2017, 73, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.-L.; Zhou, S.-F.; Jiao, W.-Z.; Qi, G.-S.; Liu, Y.-Z. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions by Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles Prepared Continuously via High-Gravity Reactive Precipitation Method. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 174, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuwei, C.; Jianlong, W. Preparation and Characterization of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles and Its Application for Cu(II) Removal. Chemical Engineering Journal 2011, 168, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipatova, I.M.; Makarova, L.I.; Yusova, A.A. Adsorption Removal of Anionic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions by Chitosan Nanoparticles Deposited on the Fibrous Carrier. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisova, V.; Mezule, L.; Juhna, T. The Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles on Escherichia Coli Viability in Drinking Water Disinfection. Water Practice and Technology 2022, 17, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Peña, L.V.; Petkova, P.; Margalef-Marti, R.; Vives, M.; Aguilar, L.; Gallegos, A.; Francesko, A.; Perelshtein, I.; Gedanken, A.; Mendoza, E.; et al. Hybrid Chitosan–Silver Nanoparticles Enzymatically Embedded on Cork Filter Material for Water Disinfection. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 3599–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshekga, S.C.; Ray, S.S.; Onyango, M.S.; Momba, M.N.B. Preparation and Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposites Containing Bentonite-Supported Silver and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Water Disinfection. Applied Clay Science 2015, 114, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, K.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Younes, N.; Pandey, R.P.; Abdul Rasheed, P.; Mahmoud, K.A. “Green” ZnO-Interlinked Chitosan Nanoparticles for the Efficient Inhibition of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Inject Seawater. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3896–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.; Pastar, I.; Drakulich, S.; Dikici, E.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Nanotechnology-Driven Therapeutic Interventions in Wound Healing: Potential Uses and Applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebeish, A.; El-Rafie, M.H.; EL-Sheikh, M.A.; Seleem, A.A.; El-Naggar, M.E. Antimicrobial Wound Dressing and Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2014, 65, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomi, P.; Ganesan, R.; Prabu Poorani, G.; Jegatheeswaran, S.; Balakumar, C.; Gurumallesh Prabu, H.; Anand, K.; Marimuthu Prabhu, N.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Saravanan, M. Phyto-Engineered Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) with Potential Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Wound Healing Activities Under in Vitro and in Vivo Conditions. IJN 2020, Volume 15, 7553–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Khurshid, S.; Qureshi, Z.; Daoush, W.M. Adsorption, Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Activities of Biosynthesised Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimirad, S.; Abtahi, H.; Satei, P.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Moslehi, M.; Ganji, A. Wound Healing Performance of PCL/Chitosan Based Electrospun Nanofiber Electrosprayed with Curcumin Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 259, 117640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thao, N.T.T.; Wijerathna, H.M.S.M.; Kumar, R.S.; Choi, D.; Dananjaya, S.H.S.; Attanayake, A.P. Preparation and Characterization of Succinyl Chitosan and Succinyl Chitosan Nanoparticle Film: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Wound Healing Activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 193, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagül, Ş.; Özel, D.; Özturk, İ.; Yurt, F. An in Vitro Evaluation of Hypericum Perforatum Loaded-Chitosan Nanoparticle/Agarose Film as a Wound Dressing. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 98, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimirad, S.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Abtahi, H.; Sarlak, N. Antimicrobial Activity, Stability and Wound Healing Performances of Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded Recombinant LL37 Antimicrobial Peptide. Int J Pept Res Ther 2021, 27, 2505–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, S.; Racovita, S.; Gugoasa, I.A.; Lungan, M.-A.; Popa, M.; Desbrieres, J. The Benefits of Smart Nanoparticles in Dental Applications. IJMS 2021, 22, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakaran, H.; Krithikadatta, J.; Doble, M. Local and Systemic Adverse Effects of Nanoparticles Incorporated in Dental Materials- a Critical Review. The Saudi Dental Journal 2024, 36, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yan, J.; Mujtaba, B.M.; Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Huang, S. The Dual Anti-caries Effect of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanogel Loaded with Chimeric Lysin ClyR and Amorphous Calcium Phosphate. European J Oral Sciences 2021, 129, e12784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, R.M.; Kareem, F.A. Synergistic Antibacterial Effect of Chitosan/Silver Nanoparticles Modified Glass Ionomer Cement (an in Vitro Study). Oxford Open Materials Science 2024, 4, itae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhajibagher, M.; Rokn, A.R.; Barikani, H.R.; Bahador, A. Photo-Sonodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy via Chitosan Nanoparticles-Indocyanine Green against Polymicrobial Periopathogenic Biofilms: Ex Vivo Study on Dental Implants. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 31, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Stolarz, A.; Mikulewicz, M.; Laskowska, J.; Karolewicz, B.; Owczarek, A. The Importance of Chitosan Coatings in Dentistry. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of the Application and Effect | Physicochemical Property And Changes In Structures | Enhanced Activity Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crosslinked chitosan NPs for antibacterial drug delivery | Average size of 478 ± 86 nm Zeta potential of −29.2 ± 1.1 mV (physicochemical properties of cross-linked, drug loaded chitosan NPs) |

-Significant reduction in size by nearly 38% with crosslinking. -Crosslinked chitosan NPs exhibited 97% drug loading capacity. -Temperature-dependent antibacterial activity with drug delivery ranging 5 - 15 mm inhibition zone (37 °C > 25 °C) |

[75] |

| Crosslinking of chitosan nanocomposite with silver-sulfur doped graphene quantum dots | Increased optical peak by the crosslinking Ranging concentration of crosslinked quantum dots 5% to 15% Rougher nanocomposite surface with increased quantum dot concentration Notable non toxicity |

-Notable antibacterial activity of the nanocomposite against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with increased % of crosslinked quantum dots. -The nanocomposite exhibited antibacterial activity to certain strains of bacteria such as E. coli and S. aureus. |

[76] |

| Antibacterial activity of nanoscaled cross linked chitosans with citric membranes | Improved heat-resistance by 50 °C with crosslinking Extensible film structure with crosslinking (reduced tensile strength and increased elongation at break) High oxygen barrier capability |

-Significant enhancement in antibacterial activity from 65% to 95% (colony counting results). |

[77] |

| Crosslinked chitosan included nanocomposite for improved antibacterial and mechanical properties | High compressive strength (enhanced by 3.5-fold with crosslinking) |

-Enhanced antimicrobial activity by 3-fold higher reduction in OD values of anti-biofilm histogram (the enhancement represented both crosslinking and added Mg(OH)2 NPs into the nanocomposite) |

[78] |

| Using capping agents on chitosan-gold hybrid NPs for enhancing antibacterial activity | Spherical morphology Red shifted absorption peaks from 525 to 532 nm Zeta Potential increased (-26.4 ± 6.3 to 53.1 ± 6.7 mV) with added chitosans, reduced with modification (53.1 ± 6.7 to 31.0 ± 6.0 mV) Size reduced (25.0 ± 4.0 to 16.9 ± 2.0) with added chitosans, increased with modification (25.0 ± 4.0 to 34.1 ± 5.9 nm) |

-Enhanced antibacterial activity against methicillin–resistant S. aureus bacteria. -Addition of chitosan in formation of hybrid NPs reduced the MIC value from 125 to 62.5 μg/mL. -Modification of the NP further reduced the value to 15.6 μg/mL. -Significant impact on growth curve of the bacteria with the minimal concentration of 15.6 μg/mL (nearly 10-fold lower) |

[79] |

| Enhanced delivery pf antibacterial agents with chitosan NP thioliation | Average size of 136.26 ± 43.17 nm with drug loading Spherical morphology with smooth surface Thiolation-dependent drug release property (faster release at pH 7.5 and 3.5 in thiolated and non thiolated chitosan NPs, respectively) |

-Encapsulation efficiency of 69.83%±0.04. -Enhanced antibacterial drug delivery of chitosan NPs with thiolation by up to 8-fold reduction in MIC values (for certain strains of bacteria) |

[80] |

| Effect of differently crosslinked chitosan NPs in antibacterial activity of zinc oxide (ZnO) NP-included nanocomposite | Excluding elemental analysis, no notable observation in the physicochemical properties of the nanocomposites | -Crosslinked chitosan hydrogels exhibited significant antibacterial activity compared to non-modified chitosan (Ranging reduction 20 - 60% in MIC values). -Highest antibacterial activity was observed in ZnO NP and crosslinking chitosan-included nanocomposite. |

[81] |

| Application | Properties | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of peptide-capped chitosan-gold NPs for laser-induced antibacterial activity | Average size of 227 nm (258 nm with peptide conjugation) Solely formed chitosan NPs 11 nm (increased to 22 nm with peptide conjugation) Spherical Morphology Zeta potential of +42 mV |

-Increased internalization of NPs with lipopolysaccharide targeting-peptide. -At the minimum concentration, un-capped NPs decreased colony-forming unit (CFU) values to 136 ± 13 and further decreased with laser irradiation to 103 ± 6. -Capped particles significantly reduced the CFU values to 81 ± 3 and further decreased with laser irradiation 69 ± 4. |

[106] |

| Development of chitosan NP-incorporated whey-based Poly (L-Lactic Acid) (PLLA) packaging films | Thickness between the range of 70–80 μm Smooth surface |

-Increased water vapor permeability and elongation at break by chitosan NPs. -Incorporation of higher amounts of chitosan NPs enhanced the antibacterial effects, with highest inhibition observed at 5% w/w in comparison to 1% and 3% w/w. -Improved tensile strength and Young's modulus, achieving up to 50.2 MPa and 2.28 GPa, respectively, following administration of 3% w/w NPs. |

[107] |

| Fabrication of nickel oxide (NiO) NP-incorporated chitosan-based nanocomposite films | Thickness in the range of 25-31 mm. |

-Antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, S. aureus and Salmonella typhimurium (S. typhimurium), respectively. -Photocatalytic activity evidenced by 72% dye (methyl orange) absorption, following 270 minutes of exposure to UV radiation. |

[108] |

| Development of chitosan-based bioactive films incorporating quercetin-loaded chitosan NPs (QCNPs) | Thickness ranging in between 43.1 and 45.6 μm. High transparency with bright yellow color Intact morphology after administration of QCNPs, with no defects observed |

-Significant UV-light barrier properties. -Enhanced thermal, mechanical and water vapor barrier properties through administration of QCNPs. -Antibacterial activity against E. coli and Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes). -Improved DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity following NP incorporation. |

[109] |

| Development of vaccarin-chitosan NPs for wound healing | Average diameter of 216.6 ± 10.1 nm Spherical-like morphology Zeta potential of +37.1 ± 1.2 mV |

-Faster cell migration by the administration of chitosan-vaccarin NPs . -Improved and faster wound healing effects on rat model, with complete recovery following 10 days of treatment. -Biocompatibility on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). |

[110] |

| Development of melatonin loaded lecithin-chitosan NPs for wound healing | Average size of 160.43 ± 4.45 nm Spherical and subspherical morphology Zeta potential of 25.0 ± 0.57 mV |

-Induced fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition by NPs. -Accelerated wound healing on rat model through administration of melatonin loaded lecithin-chitosan NPs. -Non-toxicity on Galleria mellonella model. |

[111] |

| Preparation of curcumin-loaded chitosan NPs containing hydrogels for wound healing | Average size of 370 nm with bioink encapsulation Zeta potential of 41.4 mV Spherical morphology |

-Enhanced antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus, with increasing concentrations of chitosan NPs. -Non-toxicity and biocompatibility on normal human dermal fibroblast (nHDF) cells. -Accelerated wound closure in comparison to control group following 14 days of treatment. |

[112] |

| Enhanced antibacterial activity of quercetin-loaded alginate/chitosan NPs | Spherical morphology Similar to rod-shaped structure after drug-loading Encapsulation efficiency up to 82.4% Loading capacity up to 46.5% |

- Antibacterial activity of unloaded alginate/chitosan NPs exhibited ZOI ranging from 8.1 ± 3.0 mm to 9.8 ± 0.17 mm. - Sole administration of quercetin exhibited ZOI ranging from 9.1 ± 0.2 mm to 14.1 ± 0.9 mm. - Drug-loaded particles exhibited ZOI of 12.1 ± 3.0 mm to 17.3 ± 0.30 mm, demonstrating the most significant antibacterial activity. |

[113] |

| Enhanced antibacterial activity of licoricidin | Spherical morphology Approximate size of 90 nm Increased size by drug loading to 150 nm Zeta potential of >45 mV pH responsive release behaviour (higher drug release at pH 5.5) |

-Compared to sole administration of the drug, chitosan NPs exhibited 2-fold reduction in MIC volumes and complete inhibition of the bacteria. -Higher antimicrobial activity in aqueous solution compared to solely used drugs. -Preserved inhibitory activity for 16 hours, while a solely used drug exhibited its activity for 10 hours. |

[114] |

| Antibacterial activity of drug-loaded alginate-chitosan NPs against spoilage bacteria | Approximate size of 100 nm Spherical and elliptical morphology Zeta potential averagely −16.12 ± 3.06 mV Temperature-dependent drug release behaviour (fastest release at 25 °C) |

-Significant reduction in concentrations of bacteria from multiple strains of aquatic products. (down to 2-3 log CFU/mL after 10 hours). -Large ZOI by >10 mm. |

[115] |

| Encapsulated alginate-chitosan NPs against Multidrug-Resistant S. aureus | Average size of 335.3 nm (drug-loaded) and 245.1 nm (unloaded) Spherical morphology Zeta potential of +33.0 ± 1 mV (unloaded) and 45.1 ± 1 mV (drug-loaded) Encapsulation efficiency of 83.45 % |

-Unloaded alginate-chitosan NPs demonstrated MIC and MBC values ranging between 32 - 128 μg/ml and 64 - 256 μg/ml, respectively. -Drug-loaded particles reduced values of MIC and MBC to 1 - 8 μg/ml and 2 - 16 μg/ml, respectively. -Anti-biofilm activity by 65–80%. -Results from biofilm gene expression demonstrated the inhibition of initial attachment of bacteria and biofilm formation. |

[116] |

| Encapsulation of cellulose nanocrystals stabilized lysozymes in chitosan NPs | Average unloaded size of 171.43 and 308.53 nm Spherical morphology Zeta potential of 59.21 mV and 51.24 mV Lowered zeta potential with drug-loading to 33.44 mV and 43.88 mV Encapsulation efficiency up to 88.29% and 84.25% (all respectively to low-sized and high-sized particles) |

-Significant antibacterial activity of drug-loaded chitosan NPs against S. aureus (up to 14.32 mm) and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (up to 11.34 mm). -Reduced MIC for both bacteria in increased particle size (0.094 and 0.377 mg/mL, respectively). -Reduced MBC in increased particle size (0.188 mg/mL) and reduced particle size (0.625 mg/mL), respectively. |

[117] |

| Characterization and antibacterial activity of chitosan NPs encapsulated lemongrass essential oil | Average size of <200 nm (unloaded particle) Spherical morphology Zeta potential of 36.3 mV (unloaded particle) Reduced zeta potential with increased essential oil concentration form 40.8 mV to 20.8 mV Encapsulation efficiency up to 44.82 ± 2.80 Loading percent up to 18.90 ± 0.87 |

-Non-loaded chitosan NPs demonstrated MIC values between 12.5 - 25 mg/mL and ZOI between 2.5 - 6.5 mm. -Loaded particles demonstrated MIC values between 1.56 - 6.25 mg/mL and ZOI between 13.8 - 17.5 mm. -The antifungal activity of both types of particles were evaluated . |

[118] |

| Development of chitosan hydrogels filled with activated and non-activated carbon NPs for water purification | Smooth external surface with several voids Increased crystallinity index with the incorporation of carbon NPs |

-Effective absorption of heavy metals including Fe, Zn, Cu and Pb, with stronger affinity towards Pb. -Bactericidal efficiency on E. coli by the unmodified chitosan hydrogels. -Loss of antibacterial activity following functionalization with carbon NPs due to lack of free positive charges. |

[119] |

| Development of hybrid chitosan-silver NP based films for water purification | - | -High mechanical stability. -Antibacterial activity in saline solution containing E. coli, with an inhibition zone of approximately 0.5 cm. -Biocompatibility on HEK 293 cells. |

[120] |

| Incorporation of chitosan NPs on orthodontic micro-implants for antibacterial activity | Particle size between 70 - 100 nm Uniform crystalline surface with dense structure |

-Strong antibacterial activity by inhibition zones between 13 - 18.3 mm (at the highest concentration of 10 mg/mL) against four different bacteria. -Significantly low MIC and MBC values by 8 - 16 µg/mL and 4 - 8.1 µg/mL, respectively. |

[121] |

| Chitosan-based nanocomposite for coating titanium dental implants | Size ranging from 26 to 52 nm (highest chitosan ratio groups) Low coating coverage and larger size (lowest chitosan ratio groups) Combination of nano-spherical particles and nanofibers |

-Pectin-chitosan nanocomposite demonstrated ZOI between average of 12.312 and 15.413 mm against various oral microorganisms (where both chitosan and pectin found in the highest concentration) -Significant bactericidal effect of 1:2 pectin/chitosan nanocomposite. |

[122] |

| Effect of chitosan NPs encapsulated with doxycycline against periodontal disease | Average size of 203.1 ± 10.51 nm Zeta potential of +32.3 ± 0.4 mV Size of 252.3 ± 4.78 and zeta potential of +30.6 ± 0.4 after drug-loading Spherical morphology Crosslinked particles with TPP |

-Significant bacteriostatic activity of the particles (500 μg/ml) against Porphyromonas gingivalis by reduction in colony numbers from 80 to complete reduction. -Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. |

[123] |

| Drug-loaded chitosan NPs for local delivery in periodontal disease | Approximate size ranging between 60.66 ± 4.97 nm to 87.44 ± 6.41 nm. Zeta potential between -15.26 ± 4.76 mV to −29.52 ± 4.91 mV. Spherical morphology Entrapment efficiency between 81.6 ± 1.8 and 88.0 ± 2.1%. Drug loading between 4.4 ± 0.3 and 16.1 ± 0.7%. |

-Controlled drug release of doxycycline and atorvastatin. -Strong inhibitory effect of chitosan NPs against S. aureus with an inhibition zone of 14–16 mm. -No notable activity against E. coli. |

[124] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).