1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement set the ambitious goal of maintaining the increase in the global temperature lower than 2 °C and if possible, below 1.5 °C compared to pre-industrial levels [

1]. This goal is directly connected to the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions originating from the use of fossil fuels in energy production. The reduction of the use of fossil fuels appears in fact feasible since, coal, oil and natural gas as a share of the total energy mix will reach a maximum of approximately 80 % within this decade and will decrease to 73 % in 2030 if the relevant policy decisions are enforced [

2]. At the same time however, the population worldwide is set to increase by 1.7 billion people by 2050 which will result to a corresponding increase in the global energy demand. Since the use of fossil fuels is projected to decrease, the increase in the energy demand will need to be met by an increase in the use of renewable energy (RE).

RE however has its own disadvantages since it is characterized by the intermittency of the corresponding energy supply which depends on factors such as the time of day, the weather and season, as well as the location of the installed capacity. To mitigate this issue, which leads to periods of either excess generated energy that needs to be curtailed or energy scarcity, energy storage (ES) solutions must be applied. Specifically for large capacity ES, pumped hydro and compressed air are suggested as the most suitable methods [

3] with the former, despite its limitation since it requires certain topological characteristics, currently having the largest share of the energy storage market; namely, more than 95 % [

4]. Another group of ES methods reported in literature consists of those associated with the Carnot Battery concept. This method is used to describe a wide range of ES methods which operate by converting electric energy to thermal (charging phase) and then thermal back to electric (discharging phase) [

5]. In the Rankine pumped thermal energy storage (Rankine PTES) Carnot Battery method the charging phase is conducted by a heat pump Rankine cycle and the discharging phase by a heat engine one, while cold and hot thermal energy storage (TES) units are used to store the thermal energy [

5]. In contrast Brayton PTES [

6], for the same process Joule–Brayton cycles are used. Rankine PTES is of specific interest among the different types of Carnot Battery methods since it can operate for temperatures between -30 °C and 400 °C and pressures between 1 bar and 200 bar [

5]. Compared to other types of Carnot Batteries, like the Brayton PTES, the narrow temperature span of the Rankine PTES cycles facilitates improved matching of the temperature profiles between the cycles and the TES units [

5]. Also, the temperature range of the Rankine PTES method makes it suitable for different types of applications like district or process heating and cooling, as well as utilization for microgrid ES [

5]. A large number of studies have been conducted in recent years on the topic of Rankine PTES. Eppinger et al. [

7] designed and analyzed a heat pump – organic Rankine cycle PTES system, choosing R1233zd(E) as the working fluid. In the same study, electric-to-electric round-trip efficiency of up to 59 % was calculated. A variation of the base case Rankine PTES system, namely the thermally integrated Rankine PTES (TI-PTES) system, promises higher round-trip efficiencies making use of low-grade heat sources [

8]. Through the implementation of multi-objective optimization a round-trip efficiency of 55 % was achieved [

8].

The utilization of a heat pump and a heat engine as described in the Rankine PTES system, namely an electrothermal energy storage method (EES) goes back to the concept presented by Cahn [

9]. The EES system more recently was introduced again by Mercangöz et al. [

10], as a method for energy storage in large quantities. The EES system is comprised of a heat pump (HP) and heat engine (HE) using transcritical CO

2 (TCO

2) as the working fluid, water for the storage of sensible heat and ice for the storage of latent heat. In the same study, thermoeconomic analysis of the EES system is conducted through modelling and simulations and optimal round-trip efficiencies are found between 51 % and 65 %. In another study, Morandin et al. [

11] proceeded to conduct the design and optimization of the EES system having as a focus point the thermal integration of the HP and HE cycles finding an optimal round-trip efficiency of 60 %. Fernadez et al. [

12], expand the research in the EES system by considering the addition of solar energy in the form of heat either on the HP or the HE cycle. The authors were able to reach round-trip efficiencies higher than 60 %. The reported round-trip efficiencies of EES systems utilizing TCO

2 cycles, are well within the reported range of the Rankine PTES systems (45 % to 65 %) [

5].

The EES system initially developed by Mercangöz et al. [

10], was redesigned to include the geological storage of the CO

2 [

13] with the new system CEEGS (CO

2-based Electrothermal Energy and Geological Storage system), comprising now of two subsystems, the above surface EES system and a below surface geological energy storage system. This new system achieved a round-trip efficiency approximately between 40 % and 50 %. The CEEGS concept has recently been the subject of a European Union Horizon research project, namely CEEGS-Novel CO

2-based Electrothermal Energy and Geological Storage system [

14]. Under this concept, further studies have been recently published. The above surface EES system, the one without any geological storage, has been modelled and analyzed with parametric sensitivity analysis implemented to identify the operating conditions which lead to the highest round-trip efficiency (46.90 %) [

15]. In the same study, the effect of alternative cold energy storage mediums on the round-trip efficiency is also measured. In a subsequent study [

16], the CEEGS system was analyzed and evaluated under a different configuration where salt cavities were used as the geological storage formations with reported round-trip efficiencies between 49.1 % and 73 %. The same study when analyzing the CEEGS system without the CO

2 geological storage, reported round-trip efficiencies between 47.3 % and 55.5 %. Finally, a small lab-scale unit (200 kW) of the CEEGS system has been designed and constructed at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf to validate the concept (TRL 4) [

17]. Initial results of the operation of the system (charging phase) were presented and valuable observations were made for the future enhancement of the process in ref. 17.

The use of supercritical CO

2 as the heat transmission fluid in geothermal-related applications was originally introduced by Brown [

18]. The proposed method coupled a novel enhanced/engineered geothermal system (EGS) with partial geological sequestration of CO

2. The partial CO

2 sequestration provided additional economic benefit and incentive for future CO

2 management scenarios. EGS systems are typically generated via hydro-fracturing hot dry rock. The thermodynamic and transport properties of CO

2 are such that the novel system using CO

2 was found superior to the corresponding case of using water as the working fluid for heat extraction [

19,

20,

21]. A significant advancement occurred when, instead of fractured systems, other existing high-porosity, high-permeability geologic reservoirs, overlain by a low-permeability cap-rock, were used. Such systems were referred to as CO

2-plume geothermal (CGP) systems [

22,

23].

The present study has developed an analysis and evaluation methodology of the CEEGS system, including the implementation of the optimization of the integrated above surface EES system and below surface CO2 geological storage system (CEEGS). Moreover, the operating and geological storage conditions, as well as the TES parameters that led to the optimal efficiency of the system have been studied. Through the aforementioned analysis and evaluation of the integrated CEEGS system, the main aim of the current work, is to identify the CO2 geological storage conditions under which the system can operate with the optimal overall efficiency. Moreover, the appropriate above surface system operational conditions that match the optimal geological storage conditions will also be investigated and calculated. The next challenge, for future research, will be the investigation of the dynamic behavior of the critical parameters of the system for different RE production profiles and geological storage scenarios. In the present study, focusing initially on the above surface EES system, a maximum round-trip efficiency of 46.89 % is calculated with the performance of the discharge cycle having the most significant effect on this result. In terms of the integrated CEEGS system with the inclusion of the below surface CO2 geological storage system, two case studies were investigated. The optimal round-trip efficiencies (Case Study 1: 50.37 %, Case Study 2: 67.39 %) are improved compared to the system without geological storage which indicated the advantages of the geological storage integration. Moreover, and by further analyzing the geological storage integration through the two case studies, the importance of the geological conditions towards the overall system performance is identified and discussed. The structure of the rest of the article is as follows. In section 2, the CEEGS system and the models used for its simulation are described and analyzed. In section 3, the methodologies that were implemented are explained while in section 4, the results of the study are presented in detail and analyzed. In section 5, the results of the previous section and the conclusions made are discussed in a broad context along with potential future research outlooks. Finally, the article finishes with the conclusions in section 6.

5. Discussion and Future Outlook

5.1. Observations and Conclusions

The CEEGS system was analyzed and evaluated under two configurations without (

Figure 2) and with (

Figure 3) the inclusion of CO

2 geological storage.

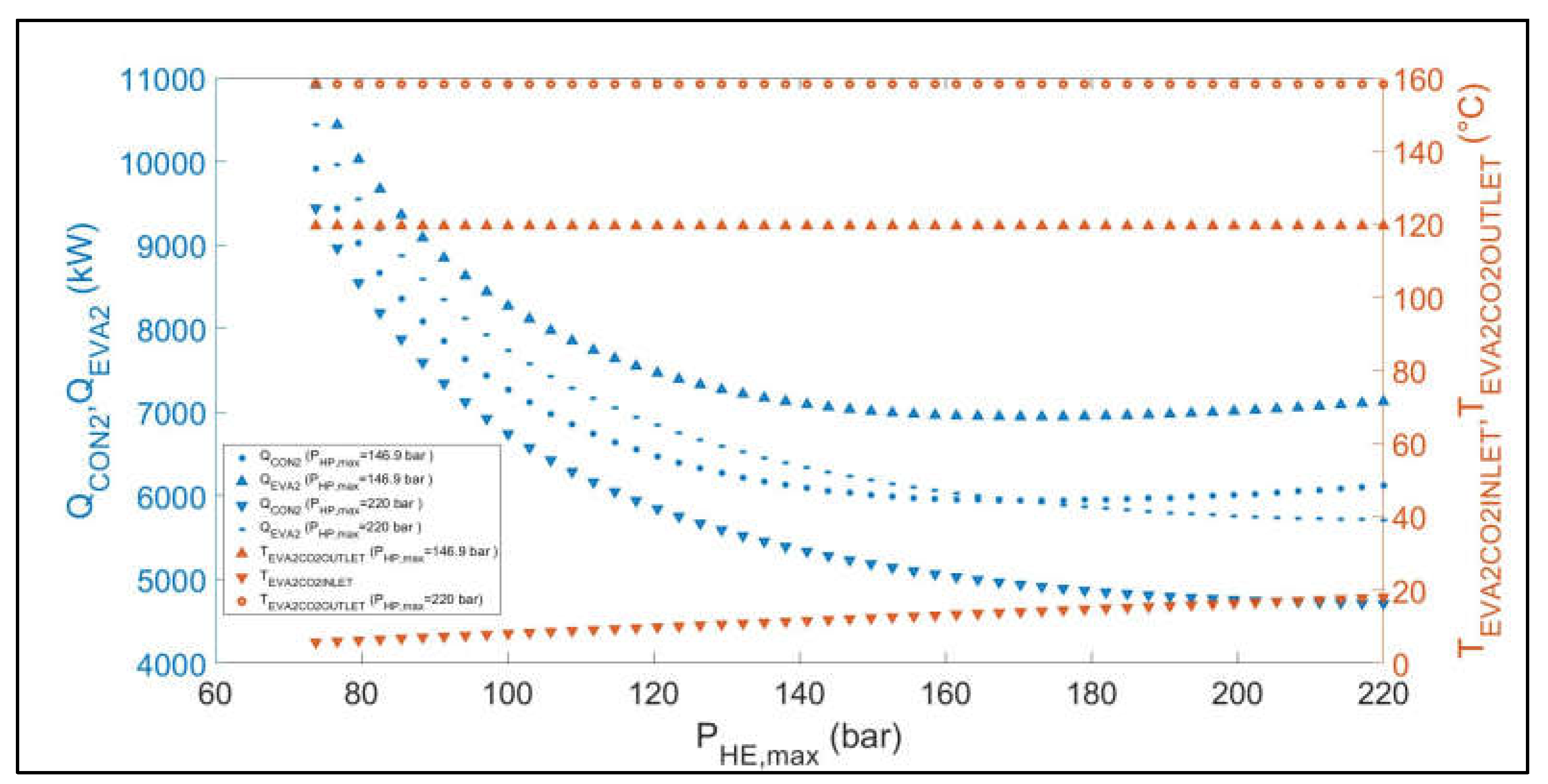

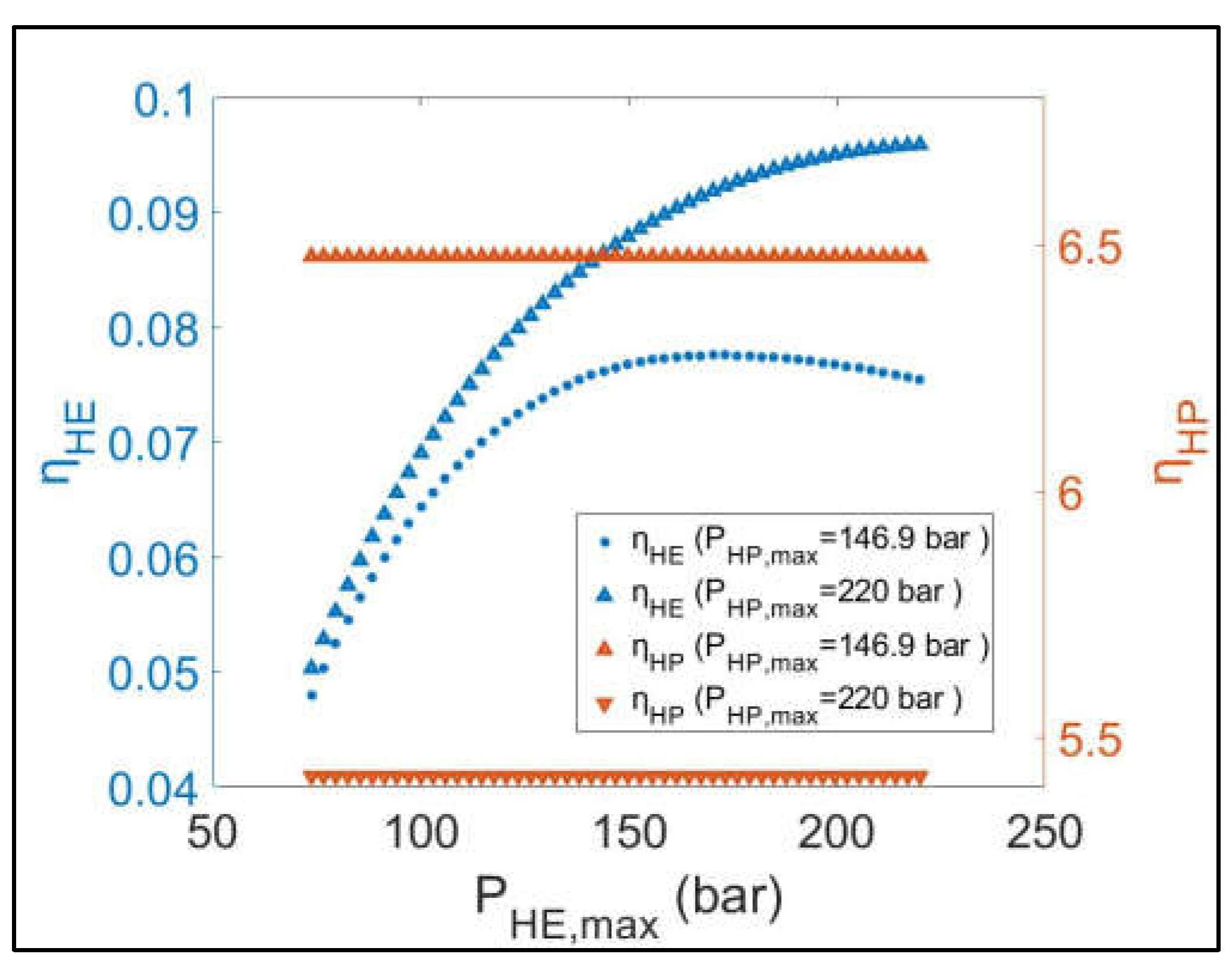

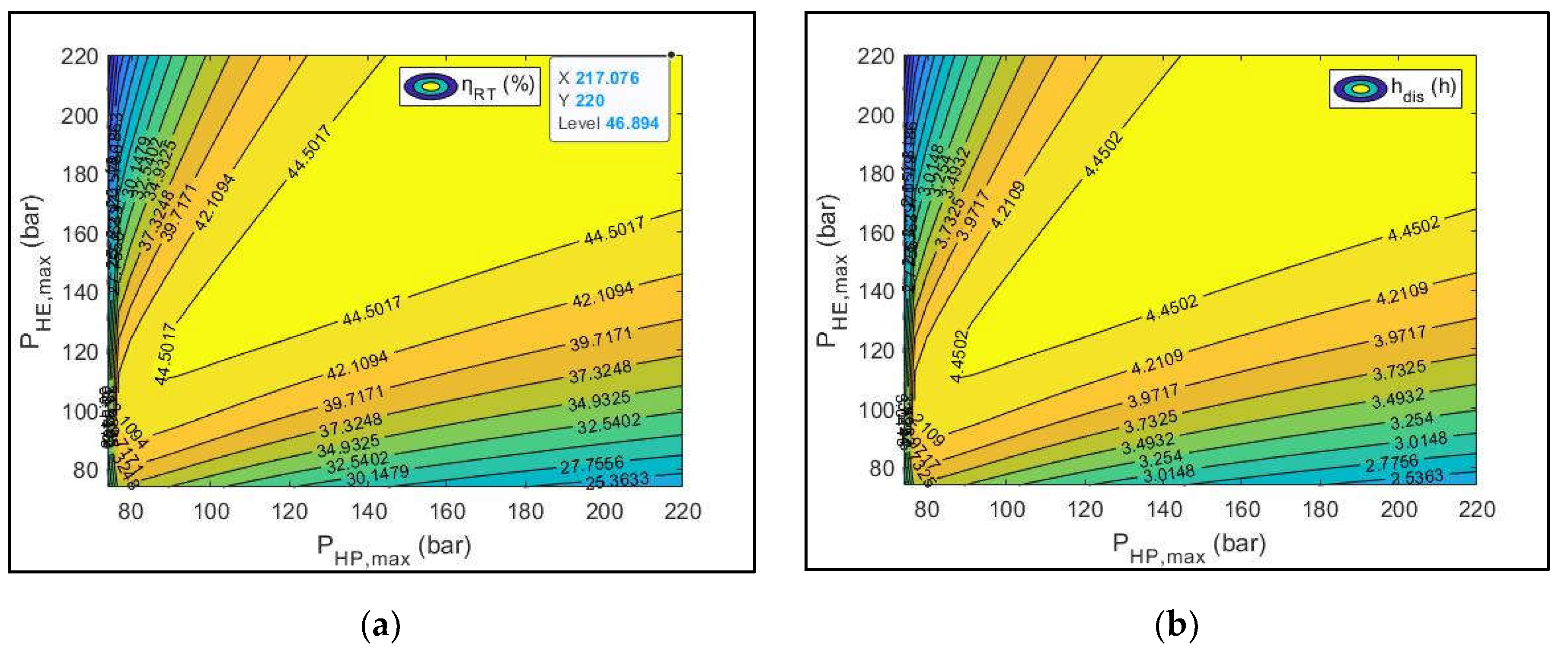

For the first CEEGS configuration without geological storage parametric sensitivity analysis was implemented to understand the operation of the system and evaluate its performance under the influence of two sensitivity analysis variables, PHP, max and PHE, max. Initially, studying the behavior of the individual cycles during the operation of the system it is observed, that the cycles’, HP and HE, efficiency metrics, ηHP and ηHE, present opposite behaviors with the increase of the PHP, max, meaning that they can never be both optimal for the same value of PHP, max. Instead, if the criterion of the performance of the whole model is these two efficiency metrics (ηHP, ηHE) a more balanced approach should be followed for the selection of the PHP, max value. In contrast, PHE, max only affects the performance of the HE cycle. When studying the whole system, the optimal ηR-T achieved is 46.89 %. This value is achieved for PHP, max and PHE, max values of 217.076 bar and 220 bar, respectively, both being towards the higher end of the range explored (73.8 bar to 220 bar). The high value of ηR-T is related to the duration of the discharging phase which is towards the upper end of the reported values at 4.69 h. At the same time, for the same sensitivity analysis values ηHP and ηHE are calculated as 5.45 and 0.095 respectively and they are located at opposite ends of their reported values, ηHP being towards the lower end and ηHE being towards the upper end. It is observed that the optimal value of the ηR-T correlates with the favorable value of the ηHE which leads to the conclusion that the HE cycle’s performance is more important to the overall round-trip performance of the first CEEGS system configuration than the performance of the HP cycle.

For the second CEEGS configuration with the inclusion of CO2 geological storage, steady-state single objective optimization was used for two case studies. The first case study used as decision variables only the above surface operating conditions (PHP, max, PHE, max) while the geological storage conditions (PWELL_A_IN, TWELL_A_IN, PWELL_A_OUT, TWELL_A_OUT, PWELL_B_IN) were predefined. In contrast, the second case study used as decision variables both above and below surface conditions (PHP, max, PHE, max, PWELL_A_IN, TWELL_A_IN, PWELL_A_OUT, TWELL_A_OUT, PWELL_B_IN). In both case studies appropriate equality and inequality constraints were used for the capacities of the two cycles, the temperature differences at the four heat exchangers and for the second case study for the pressure and temperature differences between injection and production at the well A wellheads. Initially, comparing the optimization results for the two case studies with the sensitivity analysis results of the first CEEGS configuration it is concluded that there is a positive impact in the addition of the CO2 geological storage for the ηR-T of the CEEGS system since it has improved from 46.89 % of the optimal scenario of the sensitivity analysis to 50.37 % of case study 1 and 67.39 % of case study 2. As in the sensitivity analysis observations, the increase in the ηR-T correlates with the increase of the discharging hours. At the same time, the ηHE has improved from 0.095 to 0.12 and 0.188 whereas ηHP has decreased from 5.45 to 4.29 and 3.6 respectively. The amount of wasted energy also reduced from 16.4 % to 3.82 % and 2.46 %, respectively. Finally, improved round-trip efficiencies have been achieved for lower values of the maximum pressures of the two cycles PHP, max and PHE, max which indicates reduced turbomachinery requirements.

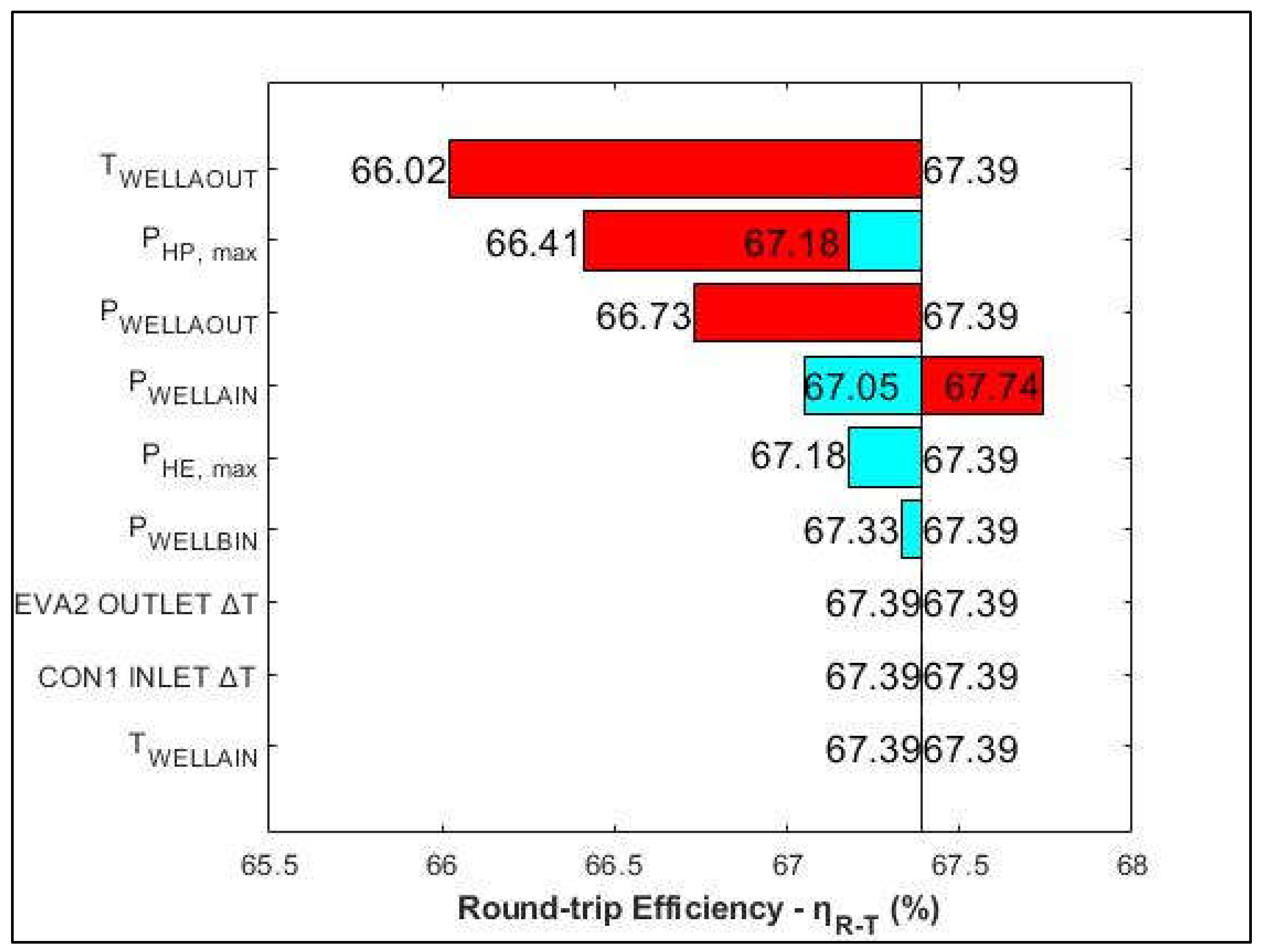

Focusing on the two geological storage case studies useful observations can be made for the identification of the appropriate geological storage conditions that can lead to the highest possible ηR-T. With regards to well A, in case study 2 where the ηR-T was significantly higher than case study 1, the wellhead injection and production pressure and temperatures have moved to higher values. At the same time, the pressure and temperature differences between injection and production wellheads is now 0. With regards to well B, the injection pressure has moved to the lowest possible value resulting to a 0 pressure difference at PUMP2. The same outcome is observed at COMP2 since the pressure difference at the compressor is also 0. Both results are expected since the compression requirements at the HE cycle are minimized. In terms of the two cycles, it is also observed, that in case study 2 the mass flows requirements in the HE cycle are reduced while the temperature that the hot water needs to reach is also significantly less. A further parametric sensitivity analysis on case study 2 reaffirms the previous conclusions since it indicates that the pressure loss between injection and production wellhead A is one of the most critical factors for the improvement on the ηR-T. Moving from a pressure loss (PWELL_A_IN - PWELL_A_OUT>0) to a pressure gain (PWELL_A_IN - PWELL_A_OUT<0) has a positive impact on the ηR-T. Finally, TWELL_A_OUT and PWELL_B_IN affect also significantly the round-trip efficiency. Based on the above observations, it can be concluded that in general in the second CEEGS configuration, for the improvement of the ηR-T mostly it is the geological storage parameters that play the biggest role. Nonetheless, above surface parameters as in the case of the first CEEGS configuration also play a significant role such as the PHP, max and PHE, max.

5.2. Comparison to Published Literature

Comparing the η

R-T result of the current article for the CEEGS system without the inclusion of CO

2 geological storage, with past research studying similar systems using TCO

2 cycles, the reported result of 46.89 % is in between the reported values. For example, the value of 46.89 % is higher than the reported value of 39.1 % of the BEES system presented by Carro et al. [

13] and lower than the 51 % [

10] and 56.47 % [

12] of two other studies. When it is assumed that all the available thermal energy in either the hot or cold TES tank can be discharged for example through the balancing of the tanks with the use of an additional cycle, higher η

R-T can be achieved. In the current study values up to 56.1 % can be reached in this manner compared to 60 % [

11] and 59.6 % [

12]. One of the most recent studies [

16] indicates results very similar to the current model both in the case of misbalanced (47.3 % versus 46.89 %) and balanced (up to 55.5 % versus up to 56.1 %) TES tanks. Finally, the η

R-T results of the current study are also within the reported range of the wider group of Rankine PTES systems (45 % to 65 %) [

5].

Similarly, comparing the results of the optimization of the CEEGS configuration with the inclusion of CO

2 geological storage of the current article with past literature similar or increased round-trip efficiencies have been achieved. For instance, Carro et al. [

13] report values of 49.6 % while for the present work values of 50.37 % (Case study 1) and 67.39 % (Case study 2) have been presented. When the full thermal capacity of the TES tanks is utilized, the corresponding values are 56.2 % versus 52.4 % (Case study 1) and 69.1 % (Case study 2). Finally, Carro et al. [

16], when utilizing salt cavities as geological storage structures report η

R-T in the case of misbalanced TES tanks, 22.95 % to 51.54 % and in the case of balanced up to 73.05 %.

5.3. Future Outlook

Future research will aim at investigating the dynamic performance of both CEEGS systems; namely, the first configuration (without the CO2 geological storage) and the second configuration (with the inclusion of CO2 geological storage). First of all, in terms of evaluating different controller algorithms and the closed loop performance. Advanced control schemes, like model predictive control will be tested. The dynamic response of a number of KPIs and critical system parameters will be studied under different operating scenarios, aiming at optimal renewable integration and demand response performance.

6. Conclusions

The first CEEGS configuration, was investigated with parametric sensitivity analysis using PHP, max and PHE, max as sensitivity analysis variables with the results showing, an ηR-T of 46.89 %, ηHP of 5.45 and ηHE of 0.095. The value of the ηR-T is related to the value of the discharging hours (4.69 h) while the efficiencies of the individual cycles have opposite directions, meaning that they can never be both optimal when PHP, max varies. Finally, it is concluded that the performance of the overall system is influenced mostly by the performance of the HE cycle and not the HP cycle. The second CEEGS configuration, was investigated for two case studies with the use of steady-state, single objective optimization. Case study 1 (base case), used as decision variables only the PHP, max and PHE, max, while the geological storage conditions (PWELL_A_IN, TWELL_A_IN, PWELL_A_OUT, TWELL_A_OUT, PWELL_B_IN) were predefined. On the contrast, case study 2 included in the decision variables the geological storage conditions in addition to PHP, max and PHE, max. The results show that both case studies show improved ηR-T compared to the best case scenario of the sensitivity analysis (46.89 %) of the first CEEGS configuration. This result indicates that the inclusion of the geological storage had a positive impact on the ηR-T (50.37 % - Case study 1, 67.39 % - Case study 2). These results were accomplished for lower values of the maximum pressures of the two cycles PHP, max and PHE, max. Moreover, ηHE has improved from 0.095 (sensitivity analysis result) to 0.12 (Case study 1) and 0.188 (Case study 2) while ηHP has decreased from 5.45 to 4.29 and 3.6 respectively. Finally, the amount of wasted energy also reduced from 16.4 % to 3.82 % and 2.46 % respectively. With regards to the comparison of the two case studies of the second CEEG configuration, it is concluded that it is mostly the variation in the geological storage conditions that play the most important role to the increase of the ηR-T from 50.37 % to 67.39 %. Specifically, moving to higher values of pressures and temperatures at the well A wellheads and minimizing or even reversing the pressure loss between injection and production wellheads have the most beneficial impact on the round-trip efficiency of the system. To conclude, the results obtained through the investigation and analysis of the CEEGS system have accomplished the main aim of the present study. Specifically, the operational and geological storage conditions of the integrated CEEGS system that lead to the optimal ηR-T have been identified and presented. Future studies will investigate the CEEGS system, under different operational scenarios, in a dynamic environment to explore the impact the dynamic changes certain parameters have on its operation and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., A-S.K. and S.V.; methodology, A.S. and A-S.K.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S. and A-S.K; formal analysis, A.S., A-S.K., J.C., D.B. and G.G.; investigation, A.S., A-S.K., J.C., D.B., G.G. and I.N.T.; data curation, A.S., J.C., D.B. and G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., A-S.K., J.C., D.B., G.G., I.N.T., P.S. and S.V.; visualization, A.S., A-S.K., D.B., and I.N.T.; supervision, P.S. and S.V.; project administration, S.V.; funding acquisition, J.C., I.N.T. and S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

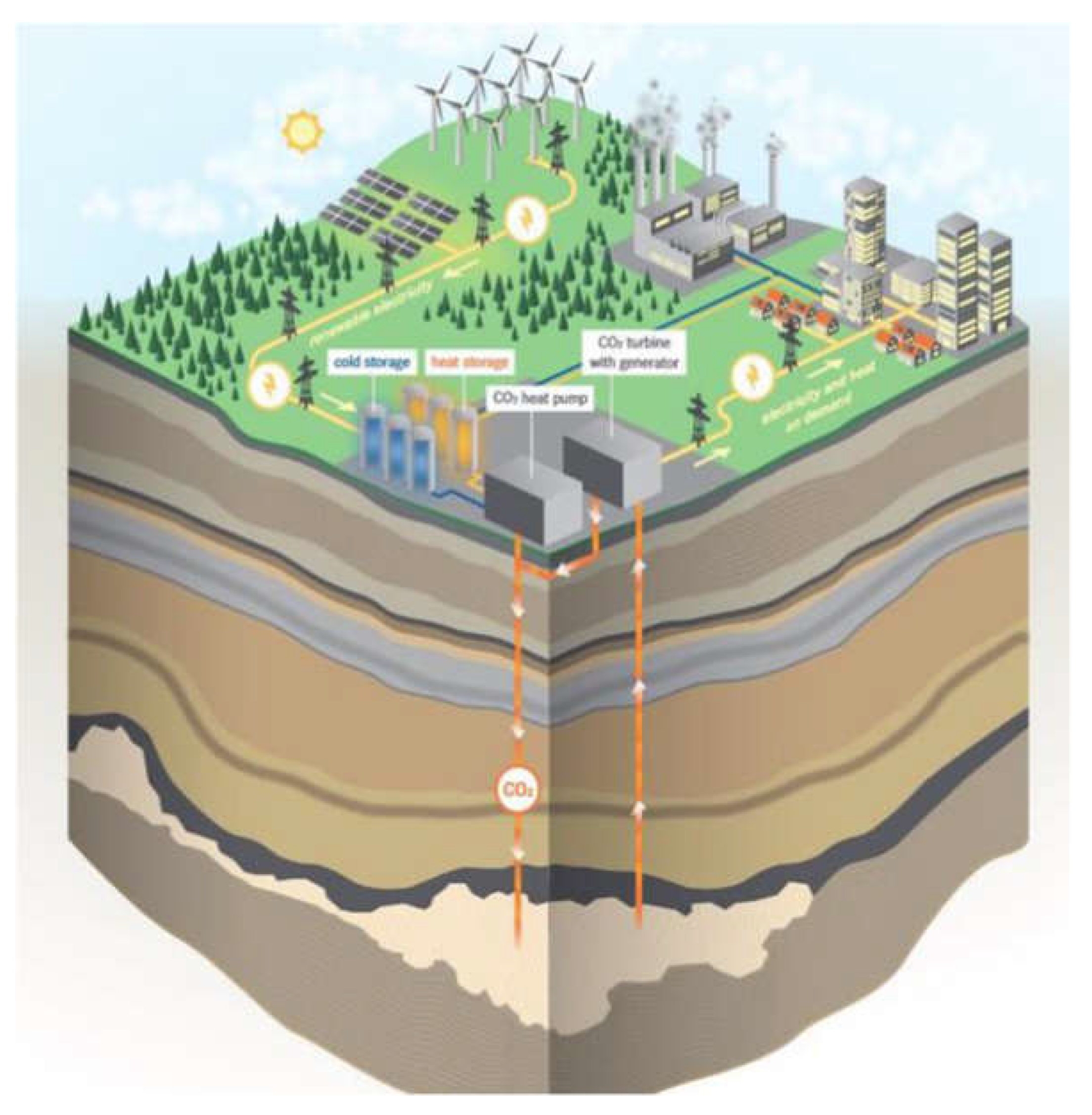

Figure 1.

The CEEGS concept [

14].

Figure 1.

The CEEGS concept [

14].

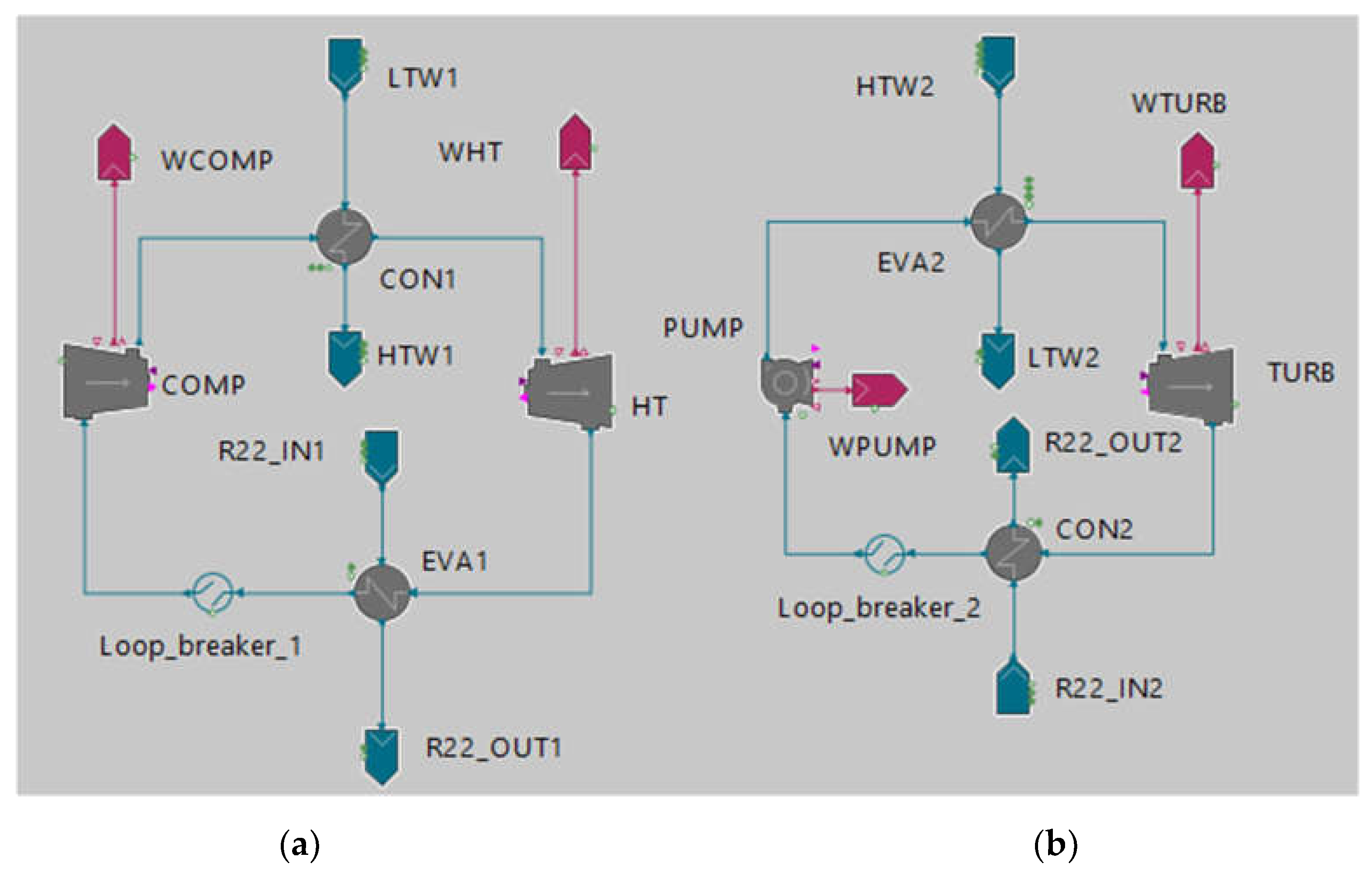

Figure 2.

EES system flowsheet: (a) Charge cycle – HP; (b) Discharge cycle – HE.

Figure 2.

EES system flowsheet: (a) Charge cycle – HP; (b) Discharge cycle – HE.

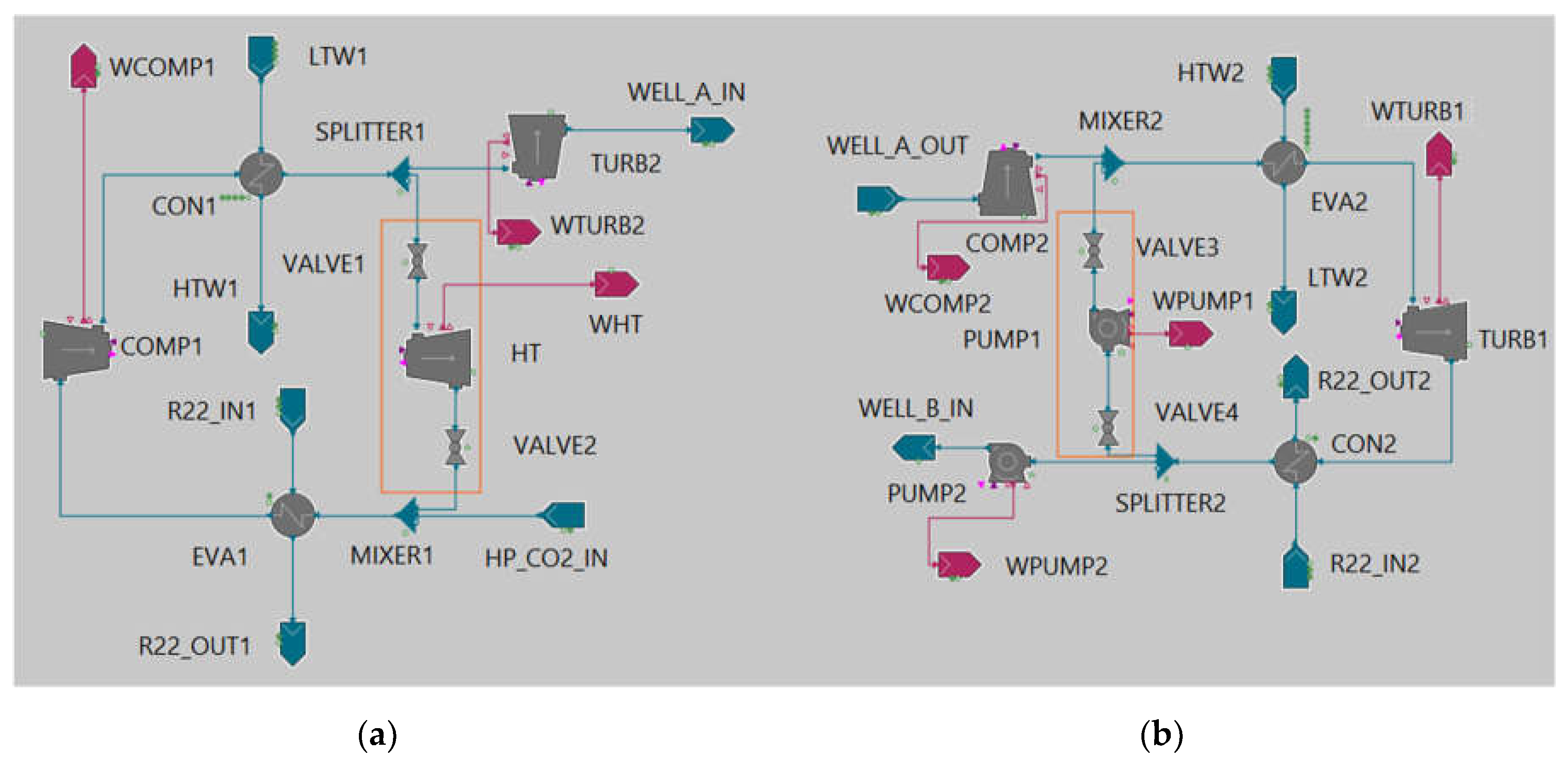

Figure 3.

EES system flowsheet with below surface CO2 storage: (a) Charge cycle – HP; (b) Discharge cycle – HE. The orange rectangles indicate the sections that are not operational for the modes considering CO2 geological storage.

Figure 3.

EES system flowsheet with below surface CO2 storage: (a) Charge cycle – HP; (b) Discharge cycle – HE. The orange rectangles indicate the sections that are not operational for the modes considering CO2 geological storage.

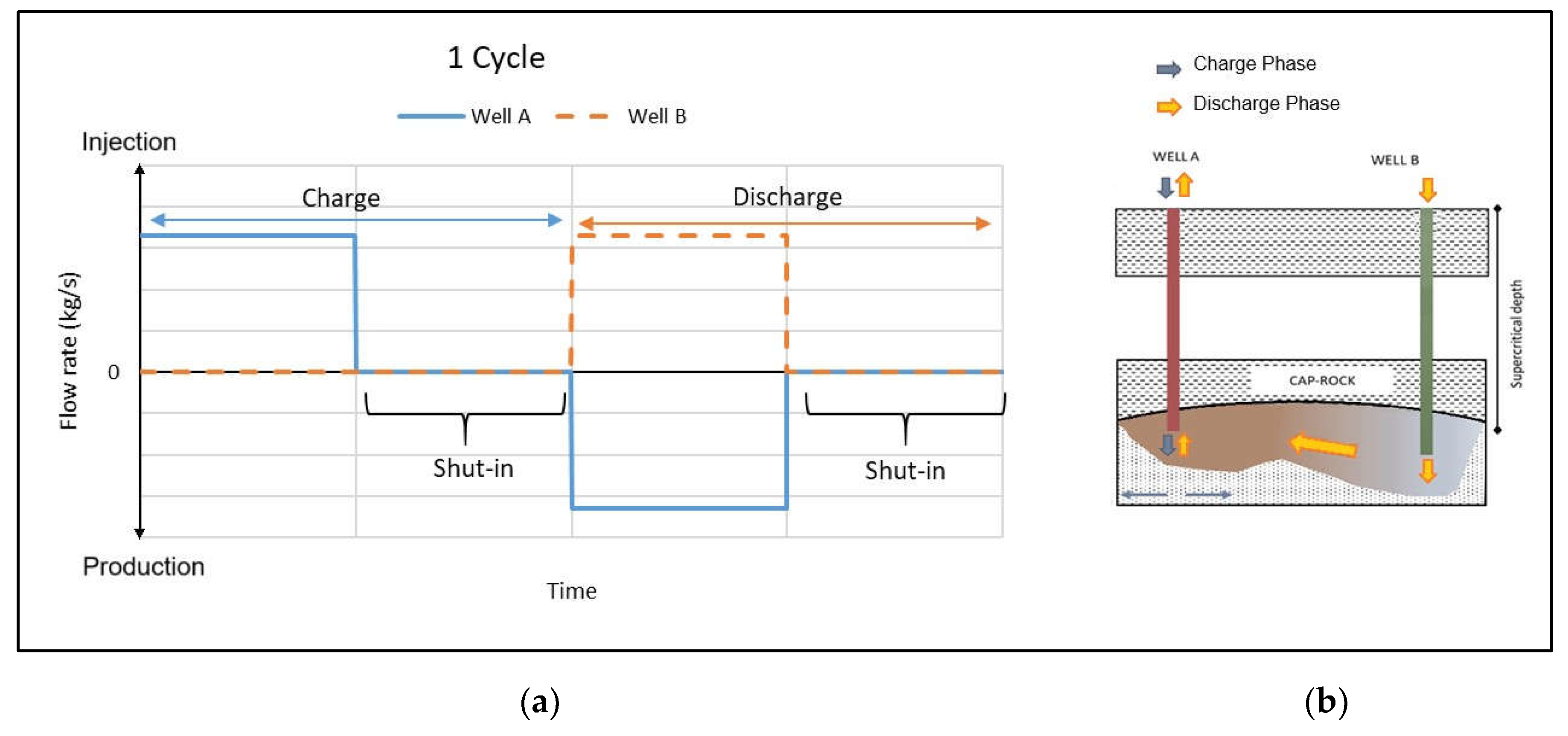

Figure 4.

CEEGS below surface CO2 storage subsystem: (a) CO2 mass flow variation with time during an energy storage scenario; (b) Depiction of the charge-discharge processes within the below surface formation.

Figure 4.

CEEGS below surface CO2 storage subsystem: (a) CO2 mass flow variation with time during an energy storage scenario; (b) Depiction of the charge-discharge processes within the below surface formation.

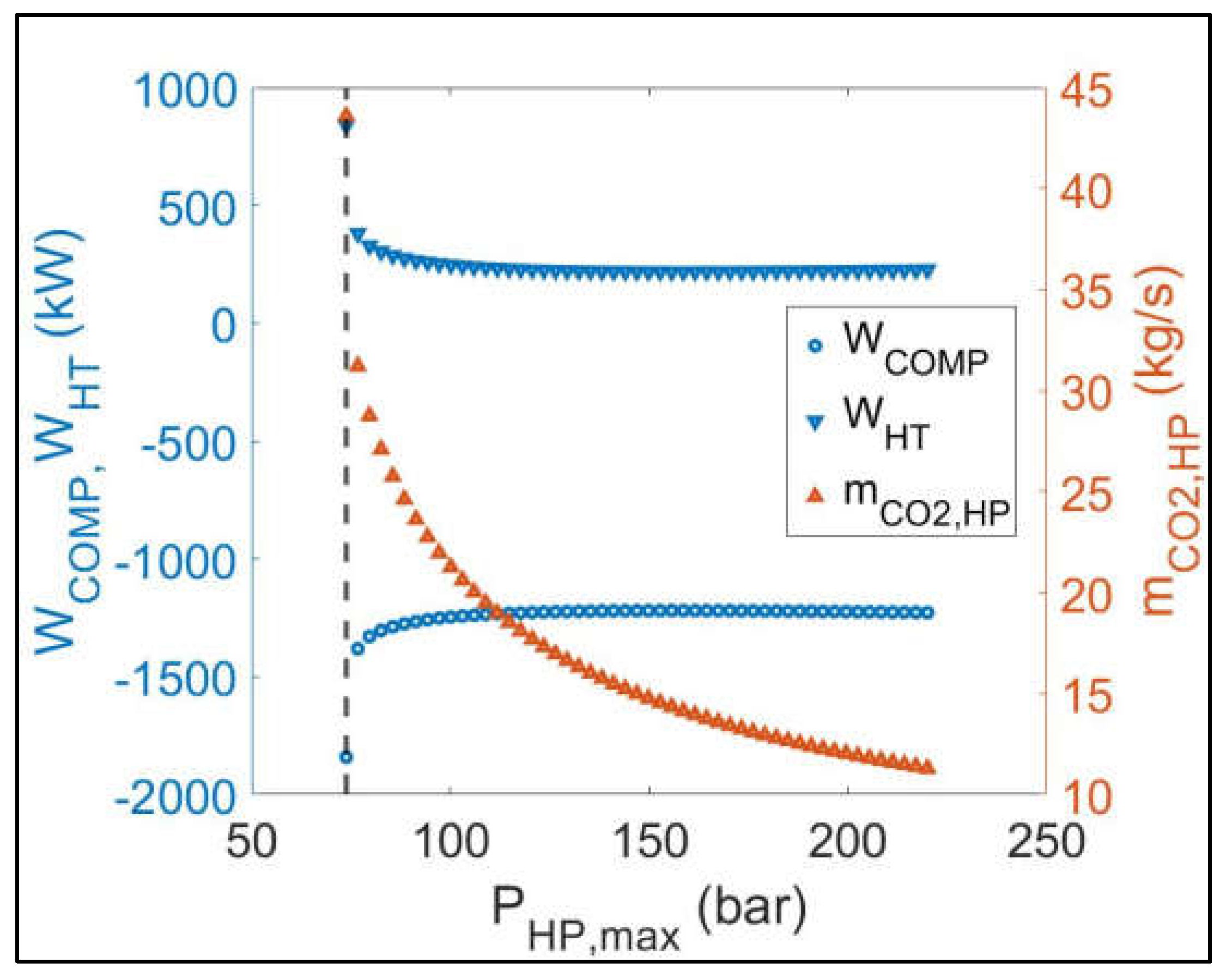

Figure 5.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of WCOMP, WHT and ṁCO2, HP versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

Figure 5.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of WCOMP, WHT and ṁCO2, HP versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

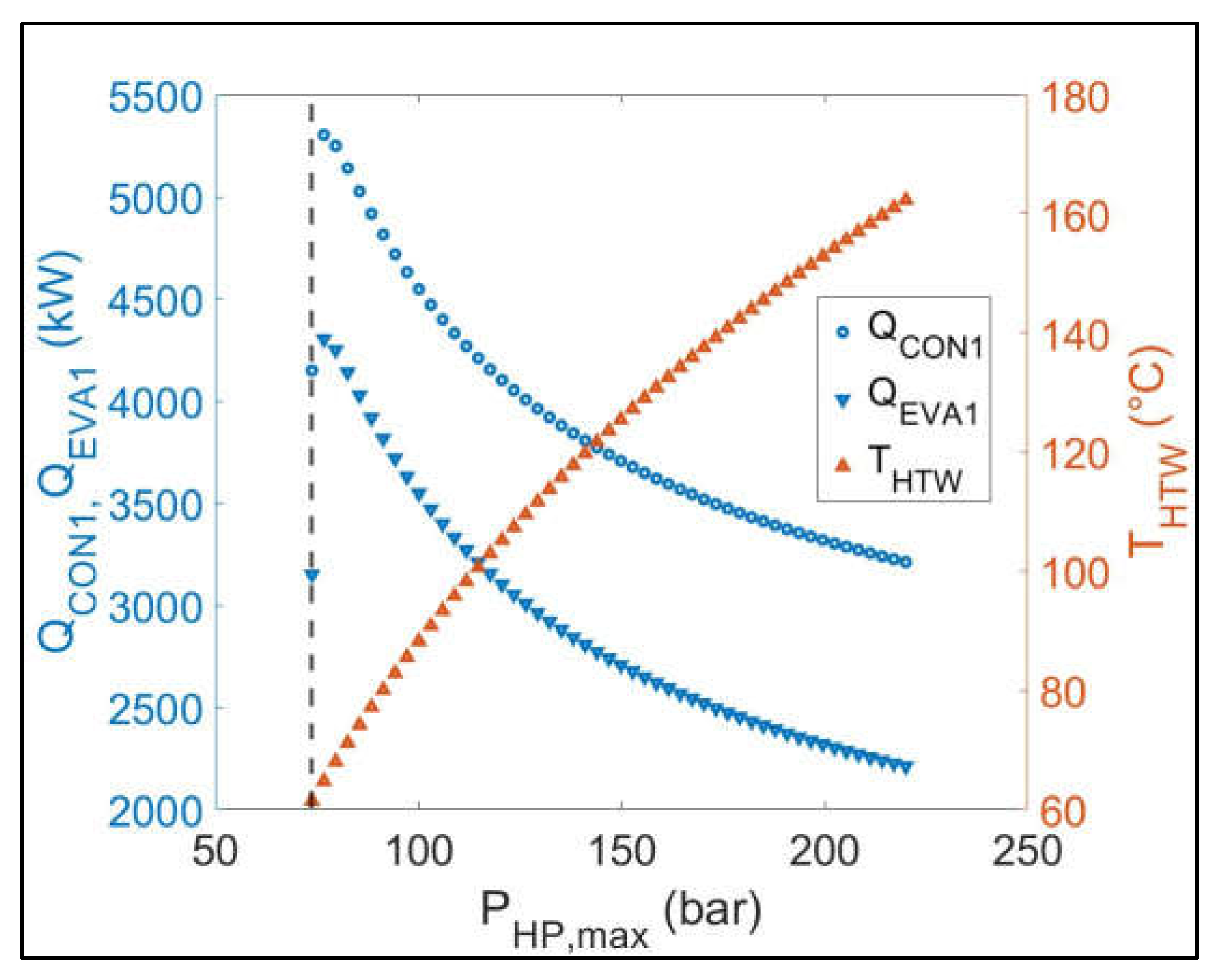

Figure 6.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON1, QEVA1 and THTW versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

Figure 6.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON1, QEVA1 and THTW versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

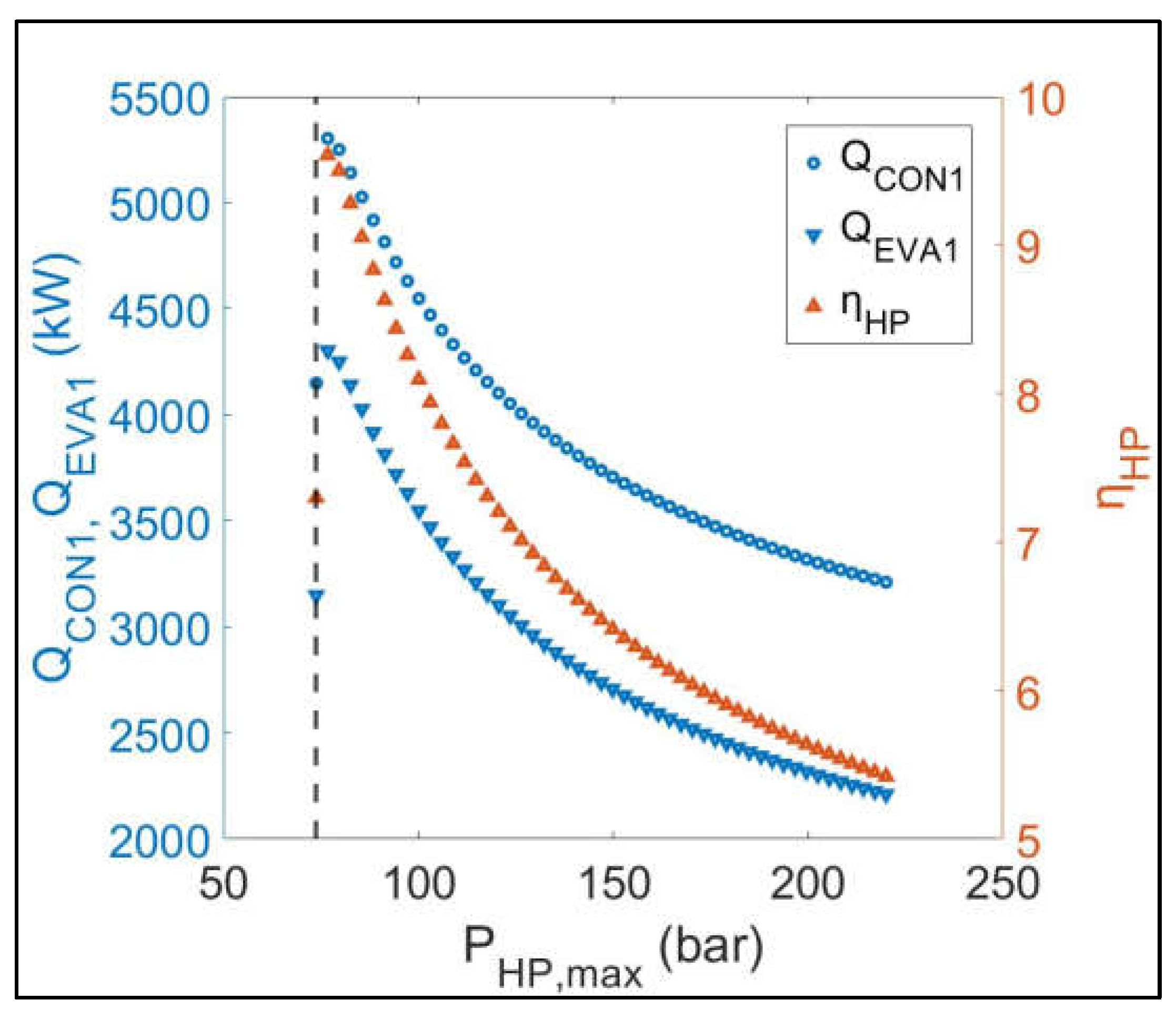

Figure 7.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON1, QEVA1 and ηHP versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

Figure 7.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON1, QEVA1 and ηHP versus PHP, max (Dashed vertical line corresponds to the critical pressure of CO2: PHP, max=73.8 bar).

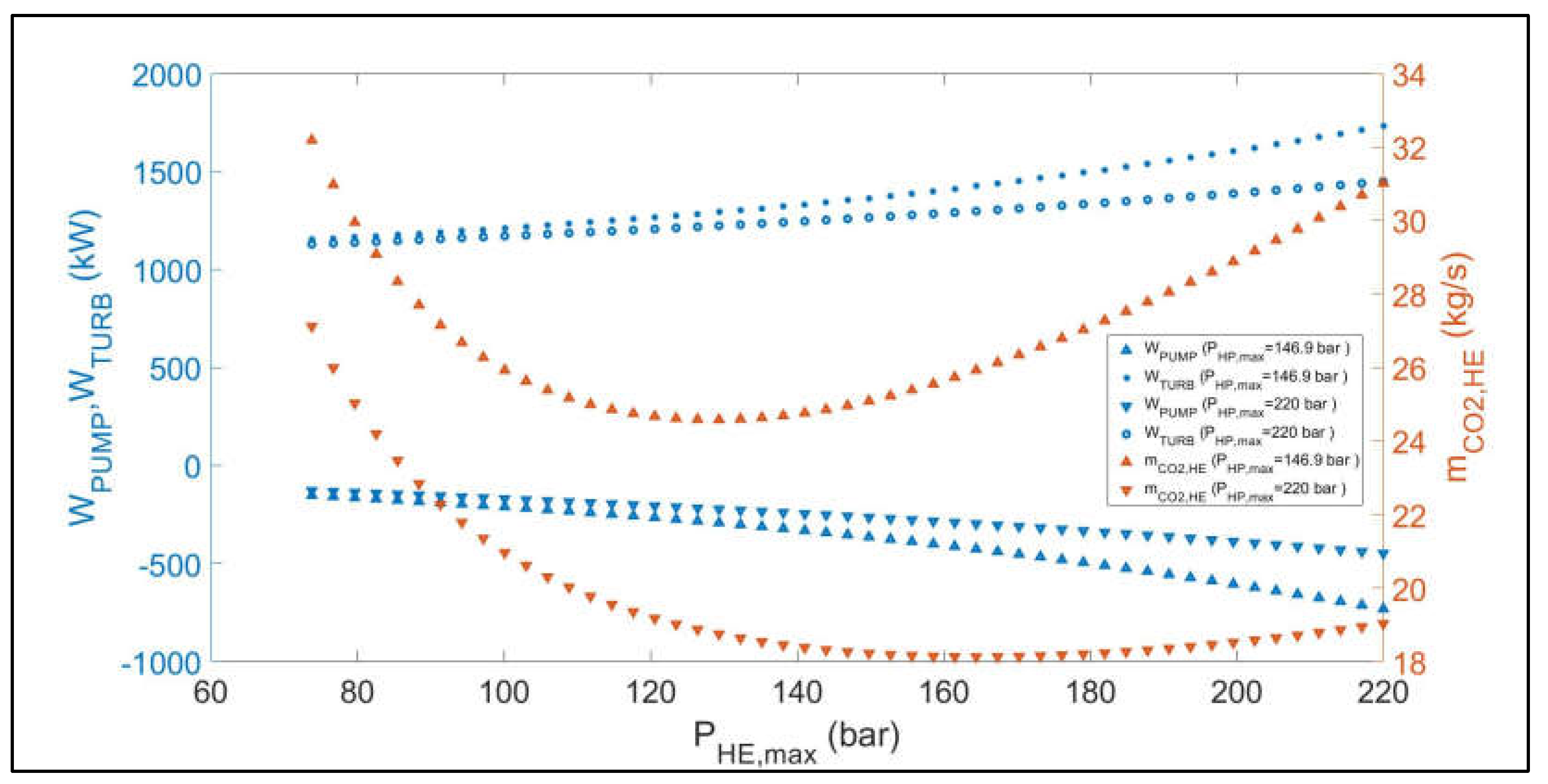

Figure 8.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of WPUMP, WTURB and ṁCO2, HE versus PHE, max.

Figure 8.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of WPUMP, WTURB and ṁCO2, HE versus PHE, max.

Figure 9.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON2, QEVA2, TEVA2_CO2_INLET, TEVA2_CO2_OUTLET versus PHE, max.

Figure 9.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of QCON2, QEVA2, TEVA2_CO2_INLET, TEVA2_CO2_OUTLET versus PHE, max.

Figure 10.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of ηHE and ηHP versus PHE, max.

Figure 10.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: Variation of ηHE and ηHP versus PHE, max.

Figure 11.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: (a) ηR-T versus PHP, max and PHE, max; (b) hdis versus PHP, max and PHE, max.

Figure 11.

Parametric sensitivity analysis results: (a) ηR-T versus PHP, max and PHE, max; (b) hdis versus PHP, max and PHE, max.

Figure 12.

Parametric sensitivity analysis on the optimal scenario of case study 2.

Figure 12.

Parametric sensitivity analysis on the optimal scenario of case study 2.

Table 1.

First CEEGS System Configuration: Input data.

Table 1.

First CEEGS System Configuration: Input data.

| Parameters |

Cycle |

Equipment |

Value |

Unit |

| Power capacity HP (Wnet, HP) |

HP |

- |

1,000 |

kW |

| Power capacity HE (Wnet, HE) |

HE |

- |

1,000 |

kW |

| Isentropic efficiency (Compressor) |

HP |

COMP |

0.86 |

[-] |

| Isentropic efficiency (Hydraulic turbine) |

HP |

HT |

0.85 |

[-] |

| Isentropic efficiency (Pump) |

HE |

PUMP |

0.85 |

[-] |

| Isentropic efficiency (Turbine) |

HE |

TURB |

0.88 |

[-] |

| Mechanical efficiency |

HP/HE |

COMP/HT/ PUMP/TURB |

1 |

[-] |

| Minimum pressure HP (PHP, min) |

HP |

- |

30 |

bar |

| Minimum pressure HE (PHE, min) |

HE |

- |

37 |

bar |

| THOT_STREAM_OUTLET

|

HP |

CON1 |

32 |

°C |

Heat exchangers minimum approach

temperature |

HP/HE |

CON1/EVA1/ CON2/EVA2 |

4 |

°C |

| Inlet stream vapor fraction |

HP |

COMP |

1 |

[-] |

| Inlet stream vapor fraction |

HE |

PUMP |

0 |

[-] |

| Pressure – water (PHTW1, PLTW1, PHTW2, PLTW2) |

HP/HE |

- |

8 |

bar |

| TLTW1

|

HP |

- |

23 |

°C |

| TLTW2

|

HE |

- |

23.1 |

°C |

| Pressure – R-22 (PR22_IN1, PR22_OUT1, PR22_IN2, PR22_OUT2) |

HP/HE |

- |

4.7 |

bar |

| TR22_OUT1, TR22_IN2

|

HP/HE |

- |

-1.55 |

°C |

| TR22_IN1, TR22_OUT2

|

HP/HE |

- |

1.52 |

°C |

| Charging hours (hchar) |

HP |

- |

10 |

h |

Table 2.

Optimization decision variables: Lower and upper bounds (Case Study 1 & 2).

Table 2.

Optimization decision variables: Lower and upper bounds (Case Study 1 & 2).

| Decision variables |

Case study |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

Unit |

| PHP, max

|

1/2 |

140 |

220 |

bar |

| PHE, max

|

1/2 |

105/140 |

220 |

bar |

| PWELL_A_IN

|

2 |

74 |

140 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_IN

|

2 |

32 |

100 |

°C |

| PWELL_A_OUT

|

2 |

74 |

140 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_OUT

|

2 |

32 |

100 |

°C |

| PWELL_B_IN

|

2 |

37 |

55 |

bar |

Table 3.

Optimization constraints: Lower and upper bounds (Case Study 1 & 2).

Table 3.

Optimization constraints: Lower and upper bounds (Case Study 1 & 2).

| Constraints |

Case study |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

Unit |

| Power capacity HP (Wnet, HP) |

1/2 |

-1,001 |

-999 |

kW |

| Power capacity HE (Wnet, HE) |

1/2 |

999 |

1,001 |

kW |

| ṁCO2, HP/HE

|

1/2 |

0 |

100 |

kg/s |

| ṁH2O, HP/HE

|

1/2 |

0 |

100 |

kg/s |

| ṁR-22, HP/HE

|

1/2 |

0 |

100 |

kg/s |

| CON1, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

1/2 |

4 |

100 |

°C |

| EVA1, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

1/2 |

4 |

100 |

°C |

| CON2, Inlet ΔT |

1/2 |

3.8 |

100 |

°C |

| CON2, Outlet ΔT |

1/2 |

4 |

100 |

°C |

| EVA2, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

1/2 |

4 |

100 |

°C |

| TCON1_CO2_OUTLET

|

1/2 |

29.85 |

176.85 |

°C |

| TEVA2_CO2_OUTLET

|

1/2 |

76.85 |

326.85 |

°C |

| TLTW1

|

1/2 |

6.85 |

176.85 |

°C |

| THTW2

|

1/2 |

76.85 |

326.85 |

°C |

| THTW2 – THTW1

|

1/2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

°C |

| TLTW2 – TLTW1

|

1/2 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

°C |

| TWELL_A_IN - TWELL_A_OUT |

2 |

0 |

0 |

°C |

| PWELL_A_IN - PWELL_A_OUT |

2 |

0 |

66 |

bar |

Table 4.

Second CEEGS System Configuration: Input data (Case Study 1 & 2).

Table 4.

Second CEEGS System Configuration: Input data (Case Study 1 & 2).

| Parameters |

Case study |

Cycle |

Equipment |

Value |

Unit |

Isentropic efficiency

(Compressor) |

1/2 |

HP/HE |

COMP1/COMP2 |

0.86 |

[-] |

| Isentropic efficiency (Pump) |

1/2 |

HE |

PUMP2 |

0.85 |

[-] |

Isentropic efficiency

(Turbine) |

1/2 |

HP/HE |

TURB2/TURB1 |

0.88 |

[-] |

| Mechanical efficiency |

1/2 |

HP/HE |

COMP1/COMP2/ PUMP2/TURB1/TURB2 |

1 |

[-] |

| PWELL_A_IN

|

1 |

HP |

- |

140 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_IN

|

1 |

HP |

70 |

°C |

| PWELL_A_OUT

|

1 |

HE |

105 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_OUT

|

1 |

HE |

50.2 |

°C |

| PWELL_B_IN

|

1 |

HE |

55 |

bar |

Table 5.

Optimization Results (Case Study 1 & 2).

Table 5.

Optimization Results (Case Study 1 & 2).

| Parameters |

Case study 1 |

Case study 2 |

Unit |

| WCOMP1

|

1083.84 |

1050.9 |

kW |

| WTURB2

|

83.84 |

50.89 |

kW |

| WCOMP2

|

331.17 |

0 |

kW |

| WTURB1

|

1380.89 |

999.99 |

kW |

| WPUMP2

|

49.72 |

0 |

kW |

| QCON1

|

1468.49 |

539.62 |

kW |

| QEVA1

|

2819.84 |

3064.56 |

kW |

| QEVA2

|

2915.16 |

781.14 |

kW |

| QCON2

|

5382.23 |

4547.3 |

kW |

| hdis, hs

|

5.04 |

6.91 |

h |

| hdis, cs

|

5.24 |

6.74 |

h |

| hdis

|

5.04 |

6.74 |

h |

| Dissipated energy on hot/cold TES tank |

3.82 |

2.46 |

% |

| ηHP

|

4.29 |

3.6 |

[-] |

| ηHE

|

0.12 |

0.188 |

[-] |

| ηR-T

|

50.37 |

67.39 |

% |

Table 6.

Decision variables: Case Study 1 & 2 Optimization Results.

Table 6.

Decision variables: Case Study 1 & 2 Optimization Results.

| Decision variables |

Case study 1 |

Case study 2 |

Unit |

| PHP, max

|

180.51 |

154.52 |

bar |

| PHE, max

|

170.33 |

140 *

|

bar |

| PWELL_A_IN

|

- |

140 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_IN

|

- |

100 **

|

°C |

| PWELL_A_OUT

|

- |

140 **

|

bar |

| TWELL_A_OUT

|

- |

100 |

°C |

| PWELL_B_IN

|

- |

37 *

|

bar |

Table 7.

Constraints: Case Study 1 & 2 Optimization Results.

Table 7.

Constraints: Case Study 1 & 2 Optimization Results.

| Constraints |

Case study 1 |

Case study 2 |

Unit |

| Power capacity HP (Wnet, HP) |

-1,000 |

-1,000 |

kW |

| Power capacity HE (Wnet, HE) |

1,000 |

1,000 |

kW |

| ṁCO2, HP/HE

|

11.42/21.45 |

12.41/17.97 |

kg/s |

| ṁH2O, HP/HE

|

5.53/11 |

5.17/7.52 |

kg/s |

| ṁR-22, HP/HE

|

13.41/25.59 |

14.57/21.62 |

kg/s |

| CON1, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

4 */4 |

4 */4 |

°C |

| EVA1, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

4/6.97 |

4/6.97 |

°C |

| CON2, Inlet ΔT |

3.83 |

3.83 |

°C |

| CON2, Outlet ΔT |

17.37 |

18.94 |

°C |

| EVA2, Inlet/Outlet ΔT |

4/4 |

4/4 |

°C |

| TCON1_CO2_OUTLET

|

84.64 |

107.9 |

°C |

| TEVA2_CO2_OUTLET

|

139.34 |

124.51 |

°C |

| TLTW1

|

80.64 |

103.9 |

°C |

| THTW2

|

143.34 |

128.51 |

°C |

| THTW2 – THTW1

|

0 |

0 |

°C |

| TLTW2 – TLTW1

|

0.1 |

0.1 |

°C |

| TWELL_A_IN - TWELL_A_OUT

|

- |

0 |

°C |

| PWELL_A_IN - PWELL_A_OUT

|

- |

0 * |

bar |

Table 8.

Parametric sensitivity analysis on the optimal scenario of case study 2: Lower & upper values.

Table 8.

Parametric sensitivity analysis on the optimal scenario of case study 2: Lower & upper values.

| Sensitivity Analysis Variables |

Lower

value |

Case study 2:

Optimal scenario |

Higher

value |

Unit |

| PHP, max

|

152.97 |

154.52 |

156.06 |

bar |

| PHE, max

|

- |

140 |

141.4 |

bar |

| PWELL_A_IN

|

138.6 |

140 |

141.4 |

bar |

| TWELL_A_IN

|

99 |

100 |

101 |

°C |

| PWELL_A_OUT

|

138.6 |

140 |

- |

bar |

| TWELL_A_OUT

|

99 |

100 |

101 |

°C |

| PWELL_B_IN

|

- |

37 |

37.37 |

bar |

| CON1, Inlet ΔT |

3.96 |

4 |

4.04 |

°C |

| EVA2, Outlet ΔT |

3.96 |

4 |

4.04 |

°C |