Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

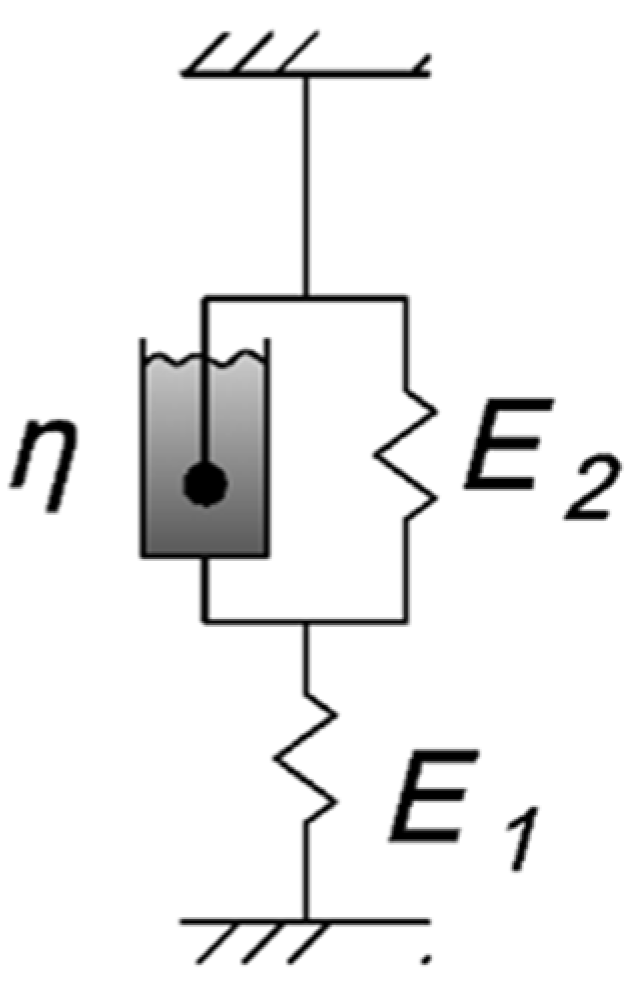

- To create a Python program for determining, based on experimental data, the mechanical parameters of the viscoelastic three-element Kelvin–Voigt model.

- To create a Python program for modeling, using the proposed approach, cyclic thermomechanical loading on a pre-loaded clamped rod sample of polymer or glass-reinforced plastic.

- To determine at different temperatures the mechanical parameters of the studied epoxy polymer and glass-reinforced plastic for the viscoelastic three-element Kelvin–Voigt model.

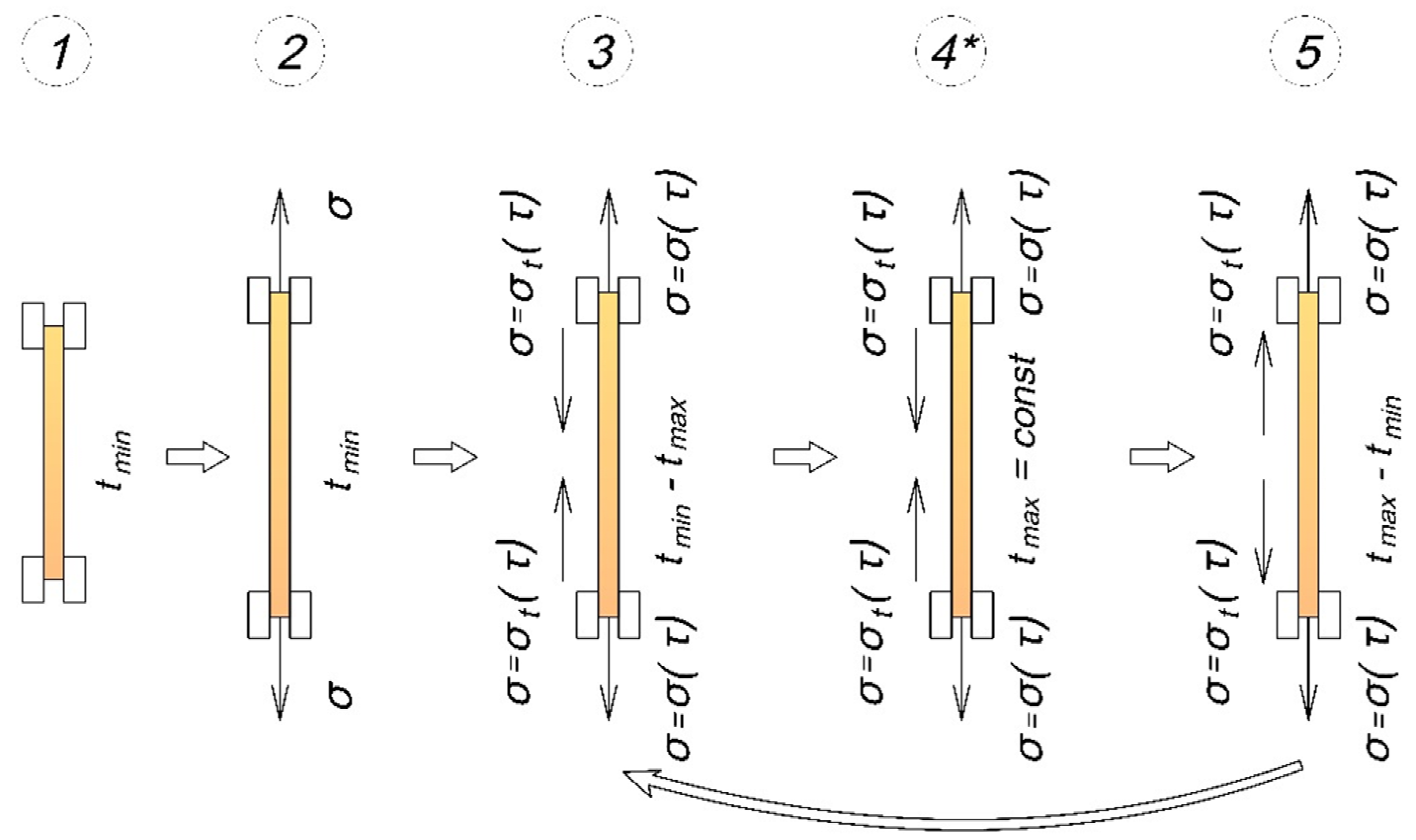

- To conduct experimental studies of the stress state of clamped rods made of epoxy polymer and glass-reinforced plastic under cyclic thermomechanical effects under different levels of initial stresses and different parameters of heating and cooling cycles.

- To perform modeling and compare with experimental results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- Epoxy resin (KER 828) – 52.5%;

- Hardener (IZOMTGFA) – 44.5%;

- Curing accelerator (Alkophen) – 3%.

- Thickness: 0.190 +0.01 / -0.02 mm.

- Surface density: 200 +16 / -10 g/m².

- Number of threads per 1 cm of fabric along the warp: 12 ± 1.

- Number of threads per 1 cm of fabric along the weft: 8 ± 1.

- Weave: plain.

- Sizing agent: paraffin emulsion.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Methods of Experimental Research

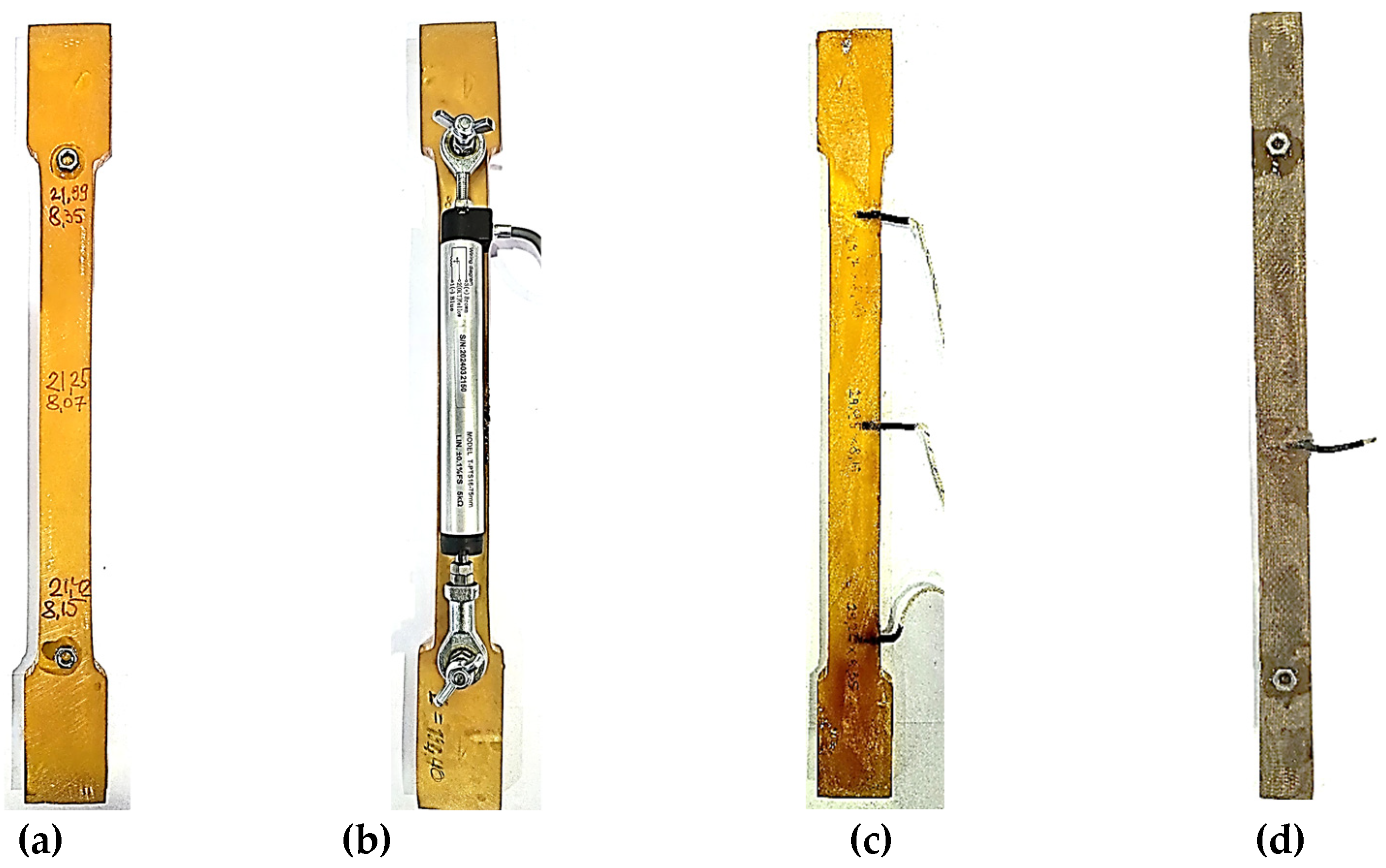

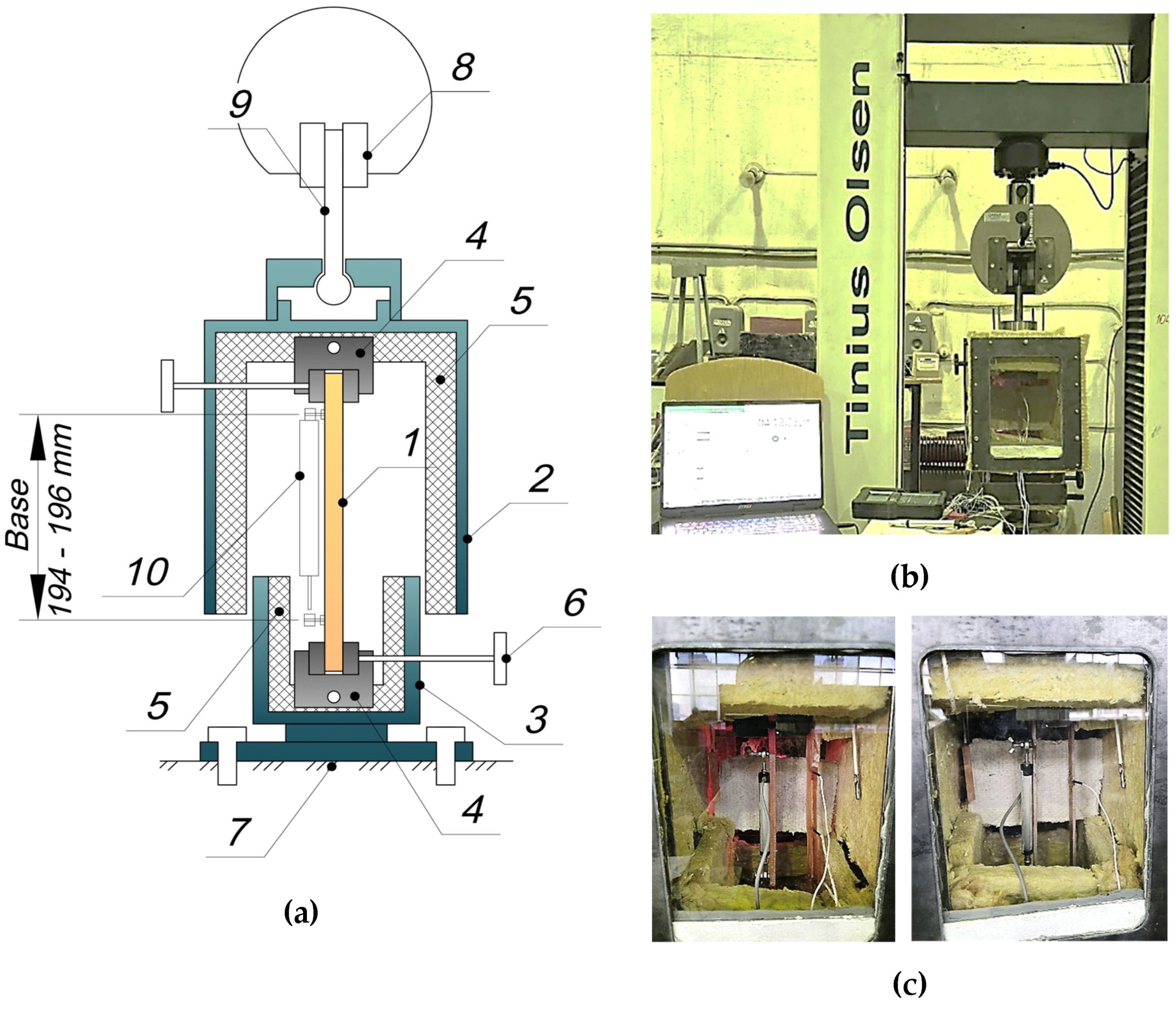

2.2.2. Methodology for Determining Mechanical Characteristics of Samples

2.2.3. Метoдика Теoретических Исследoваний

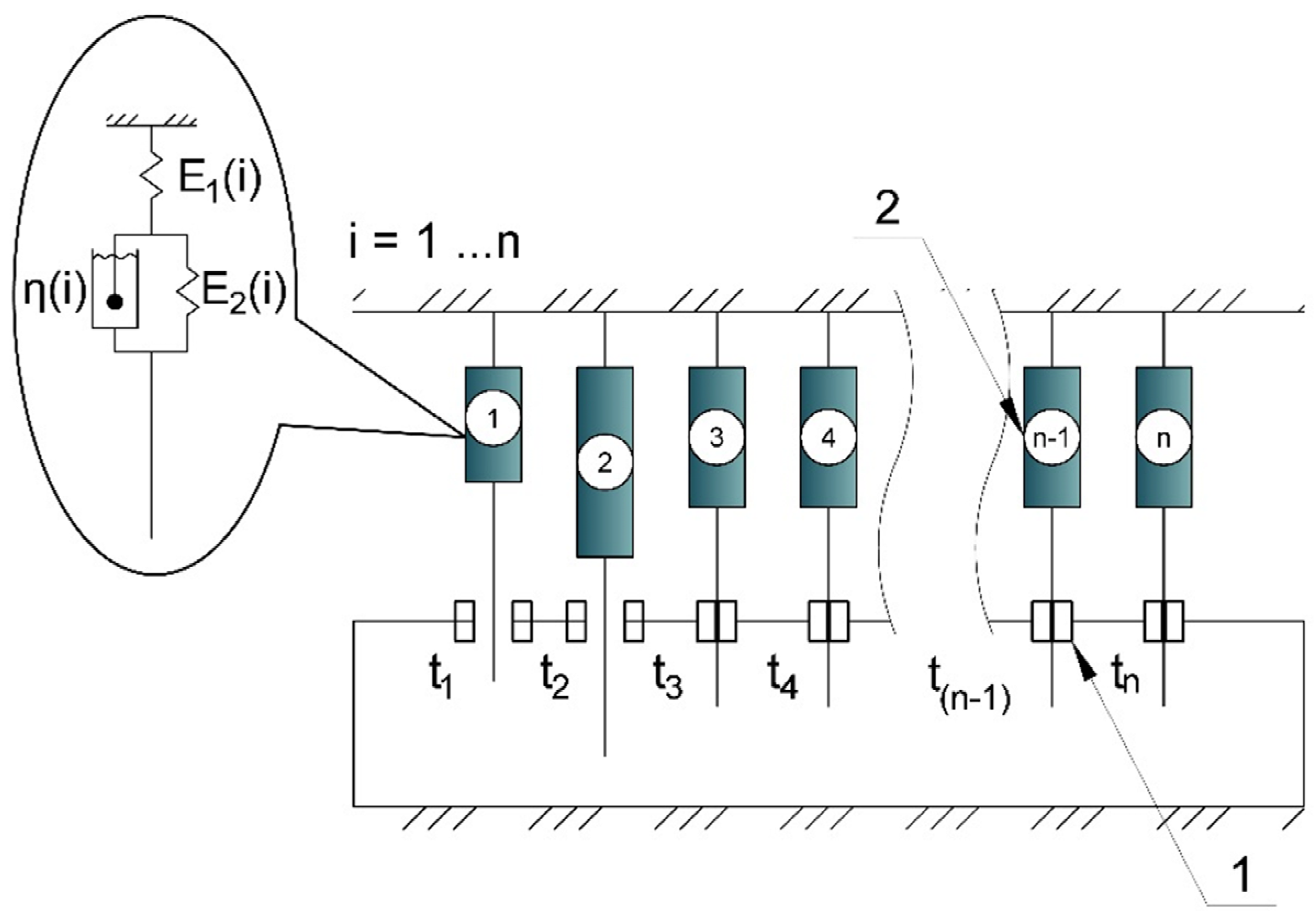

- The algorithm was implemented as a program in Python, consisting of a set of functions. This increased the modularity and flexibility of the code, simplified its maintenance and modification, and will allow adapting the program to other conditions of thermomechanical impacts in the future.

- Various laws of virtual deformation development in disconnected cells were introduced depending on the stress state at the time of deactivation. If at the time of cell deactivation, the stress was positive, virtual deformations are calculated according to one law: if negative, according to another. This allows more accurate modeling of the material's behavior under different loading regimes and temperature effects.

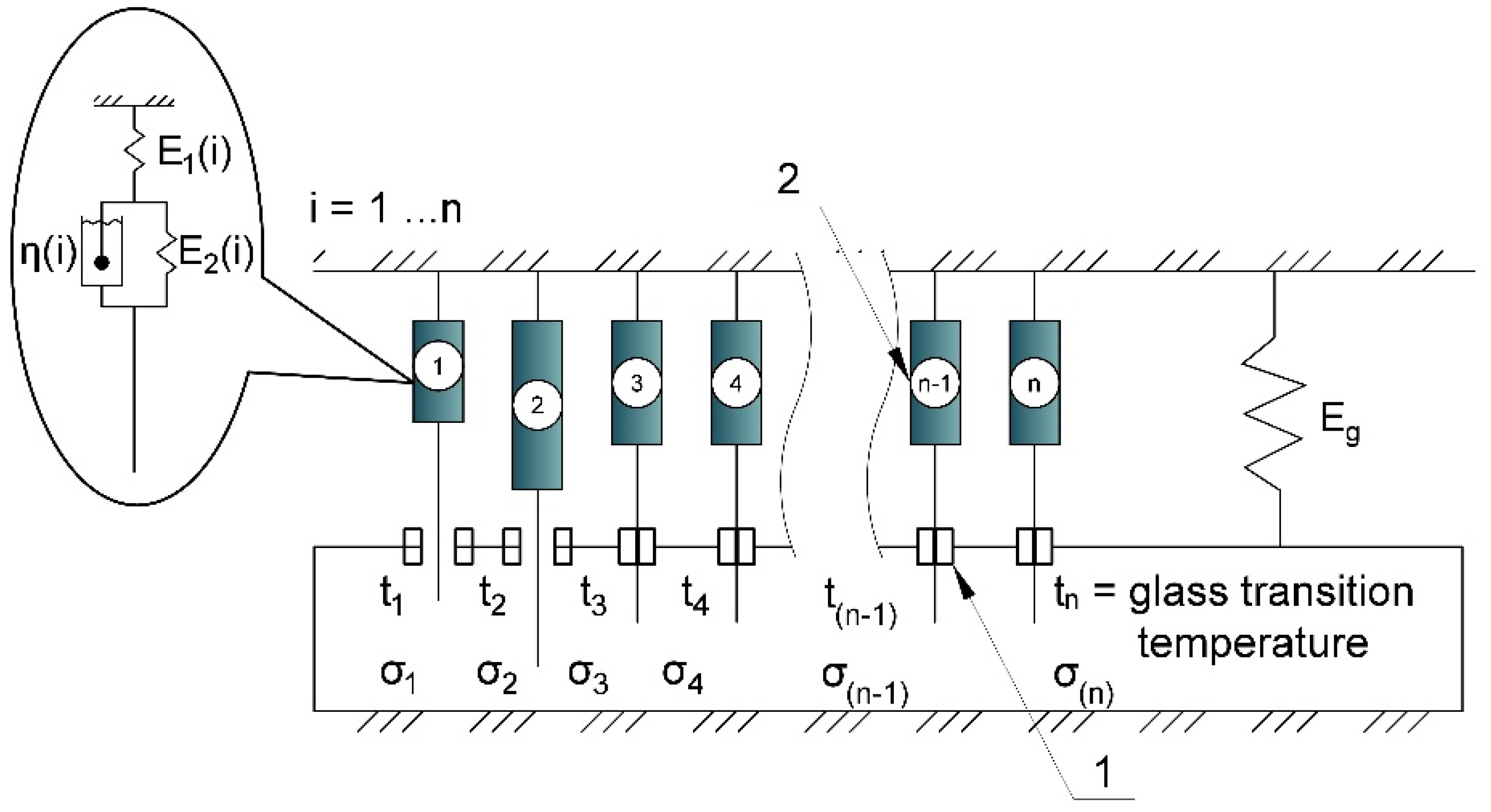

- The parameters E2 and η are distributed among the cells unevenly according to the results of their determination from relaxation curves at different temperatures, as described in section 2.2.2. For this, a parameter distribution function was developed, considering the variation of material properties with temperature, which provides a more accurate correspondence of the model to real experimental data.

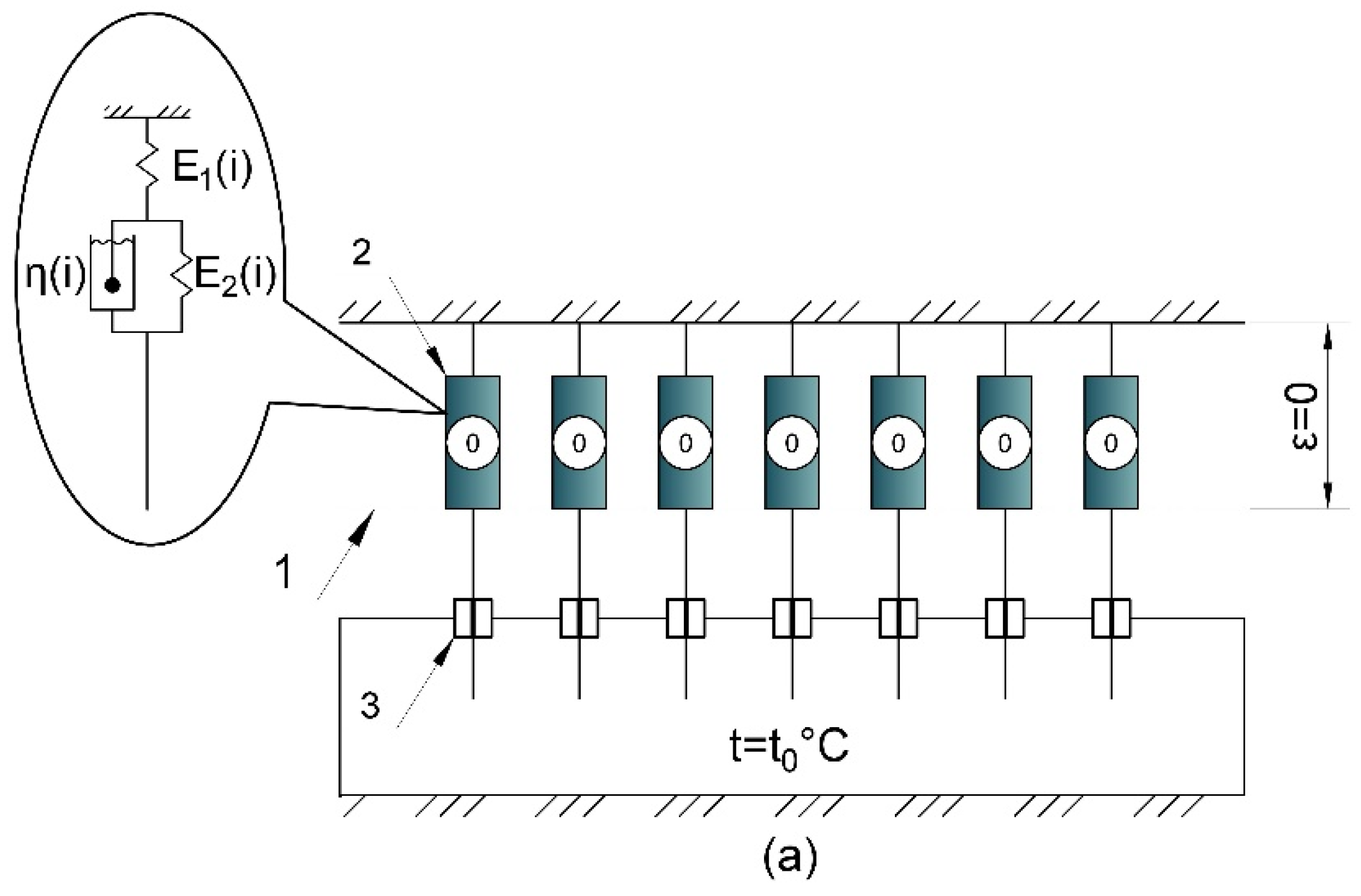

- Initialization of model parameters. The initial mechanical characteristics of the material at the initial and final temperatures, the number of cells deactivated in the heating range, geometric characteristics of the sample, mechanical load, heating and cooling rates (uniform or non-uniform) are set.

- Distribution of parameters among cells. Depending on the chosen mode (constant or variable characteristics), parameters E1, E2 и η are distributed among the cells.

- Calculation of characteristics of each cell. For each cell, the long-term elastic modulus and the relaxation time parameter m are calculated.

- Generation of temperature-time points. An array of time points and corresponding temperatures is formed, considering the specified heating and cooling cycles, heating and cooling rates, as well as possible holds at certain temperatures.

- Determination of the number of active cells. At each modeling step, the current number of active cells is calculated depending on the temperature and the specified temperature step at which cells are deactivated.

- Calculation of total mechanical properties. The parameters E1, E2, η are summed over active cells, which allows accounting for changes in stiffness and viscoelastic properties of the material during thermal exposure.

- Calculation of thermal stresses considering relaxation. At each time step, increments of thermal stresses are calculated considering relaxation processes in the material, using the stress relaxation law (2).

- Calculation of mechanical stresses considering relaxation according to law (2) and deactivation of cells. The total mechanical stresses in active cells are calculated, considering their relaxation and stress redistribution upon cell deactivation.

-

Calculation of virtual deformations in disconnected cells. Upon cell deactivation, the accumulation of virtual deformations is modeled, which depends on the stress state at the time of disconnection and the time the cell remains in the off state. Applied to the considered scheme of cyclic thermomechanical loading under the predominance of compressive (i.e., thermal) stresses before cell deactivation, the law of change:under the predominance of tensile (i.e., mechanical) stresses:

- Accounting for accumulated virtual deformations upon reactivation of cells. During cooling and reactivation of cells, accumulated virtual deformations are converted into additional stresses, which are summed with the current stresses in the material.

- Summation of total stresses and analysis of results. At each modeling step, mechanical and thermal stresses are summed, and additional stresses from virtual deformations are also considered, which allows refining the picture of the stress-strain state of the material.

- Visualization and saving of results. The program generates model graphs of stress dependence on time and saves the calculation results in files for further analysis and comparison with experimental data.

3. Results

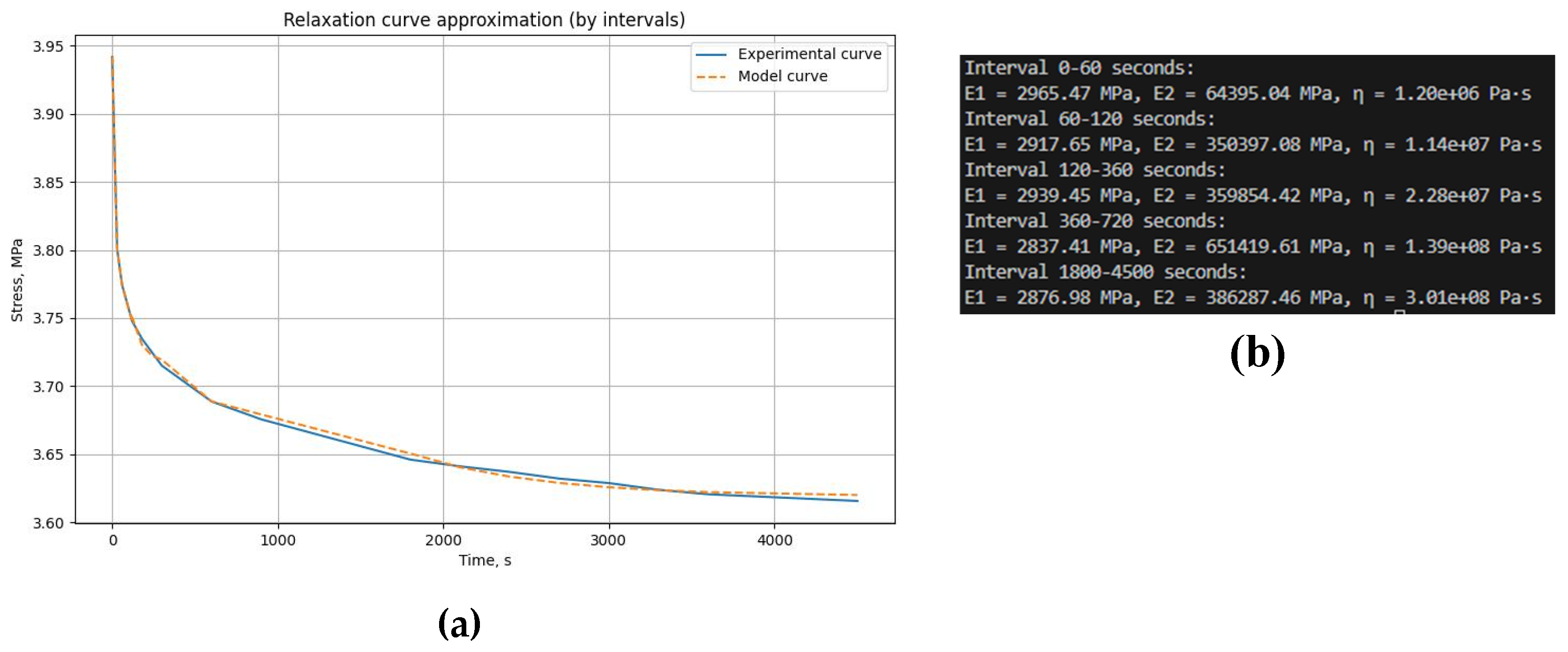

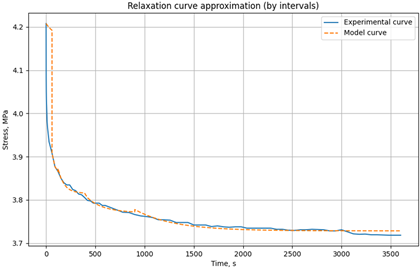

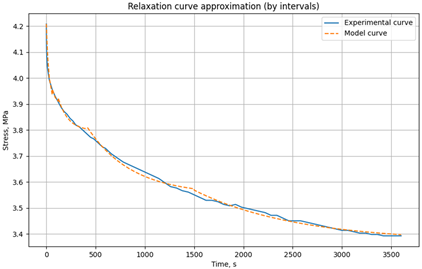

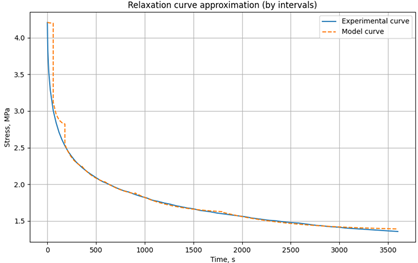

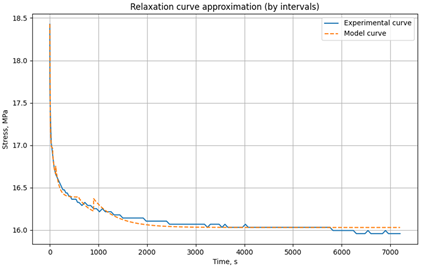

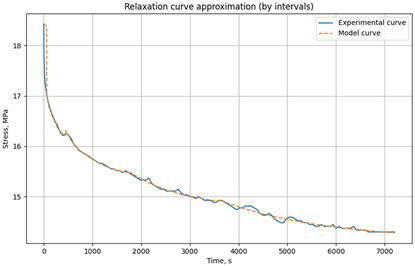

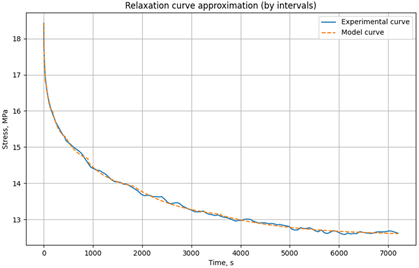

3.1. Relaxation Studies in Unreinforced Polymer and Glass-Reinforced Plastic

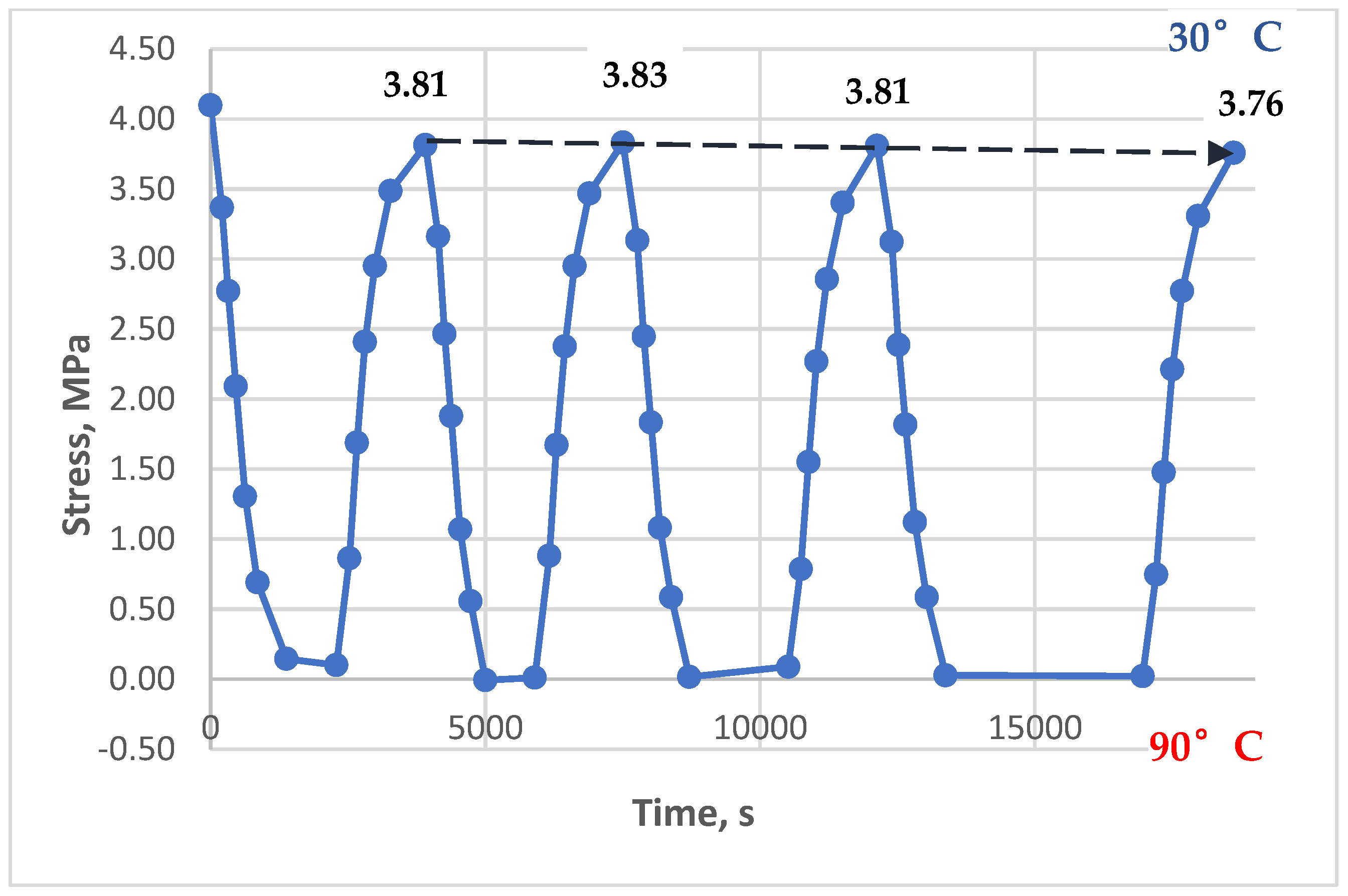

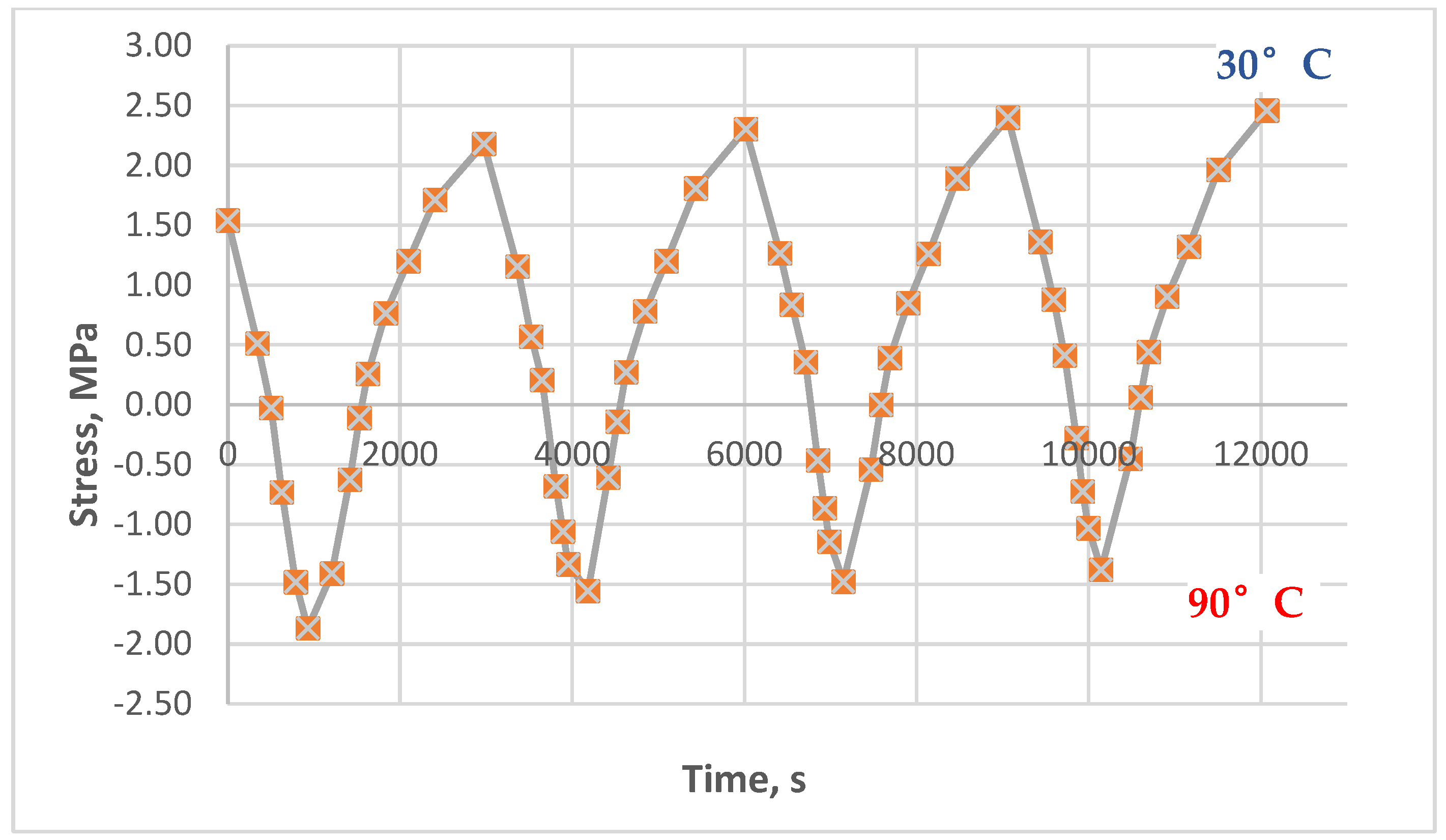

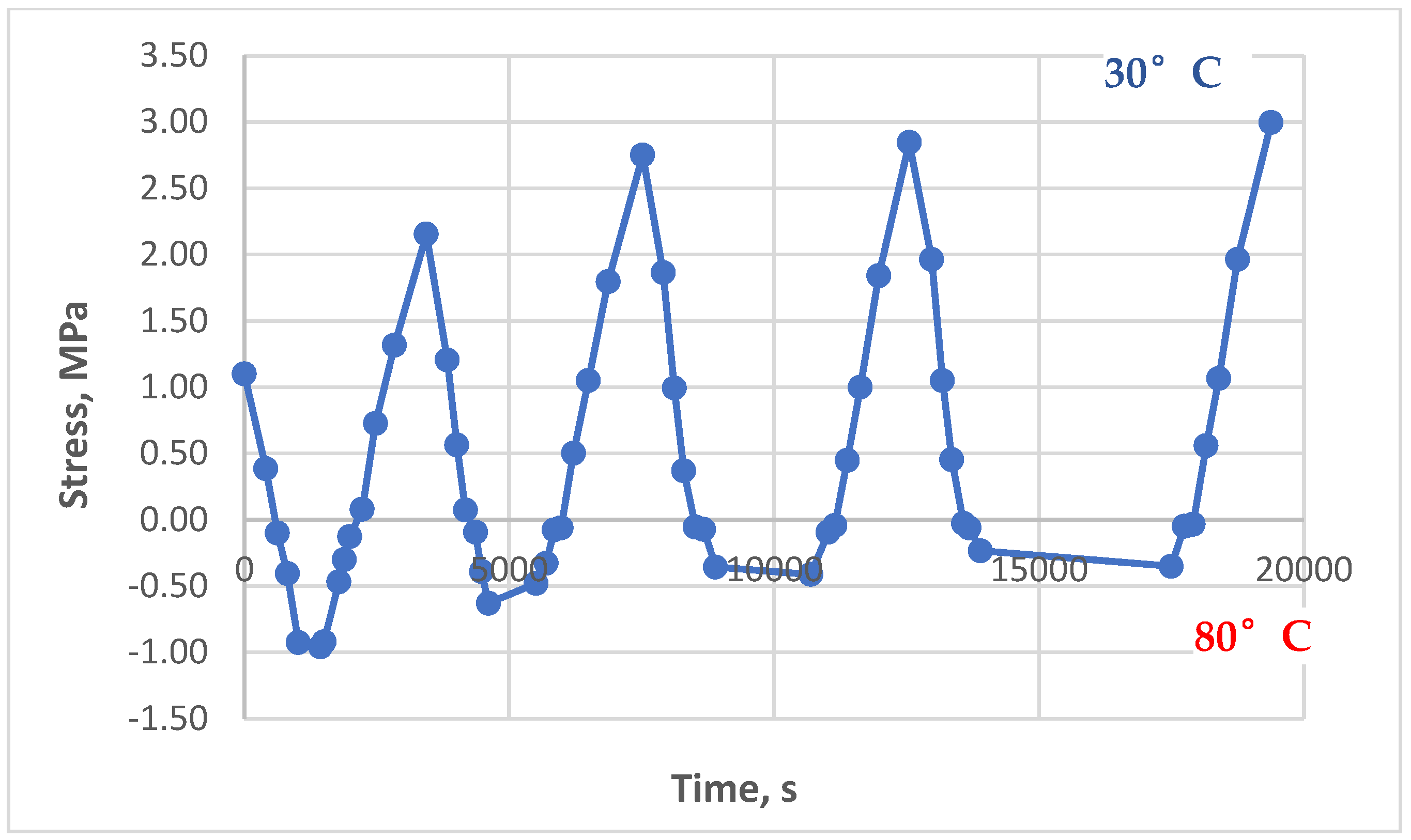

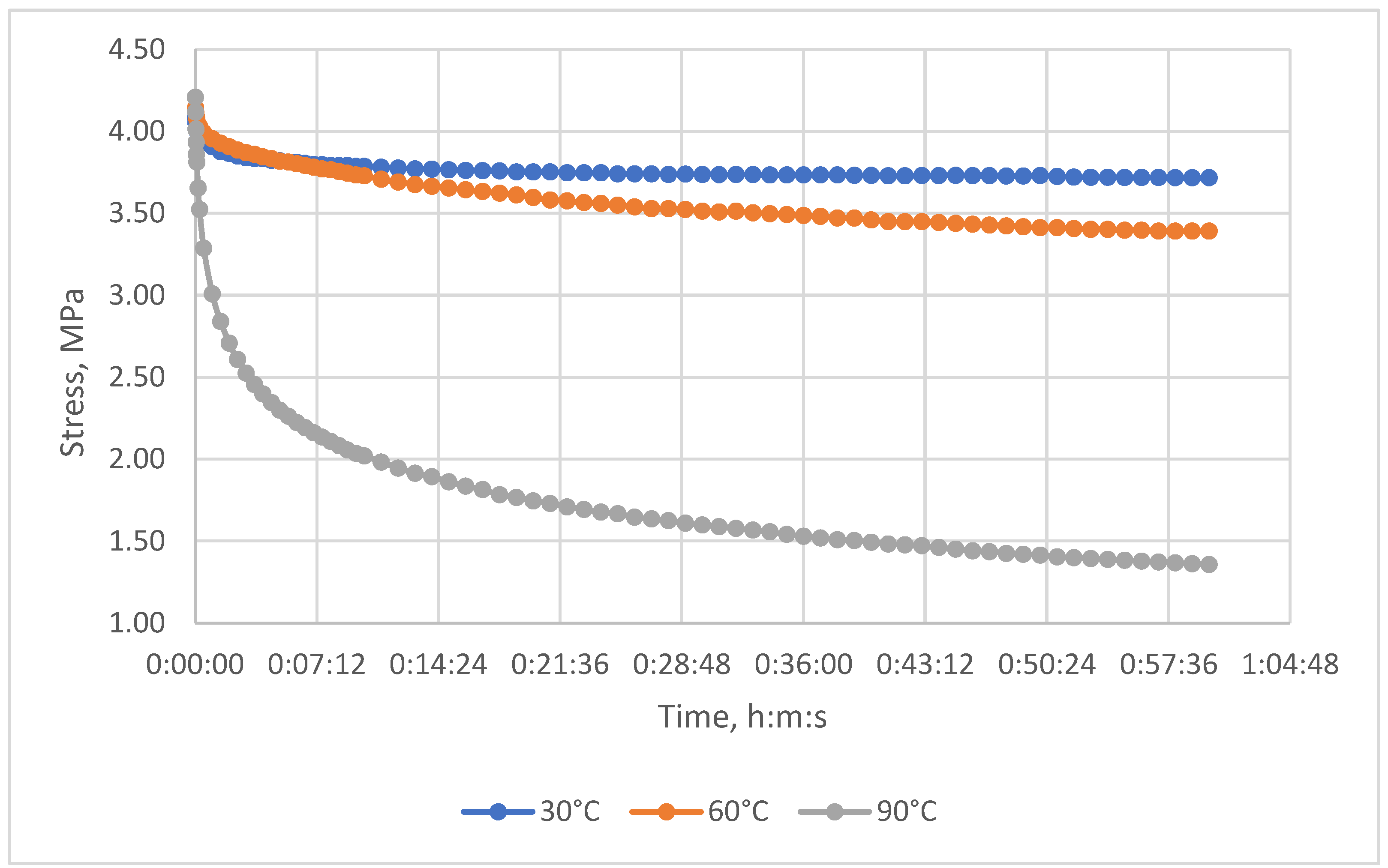

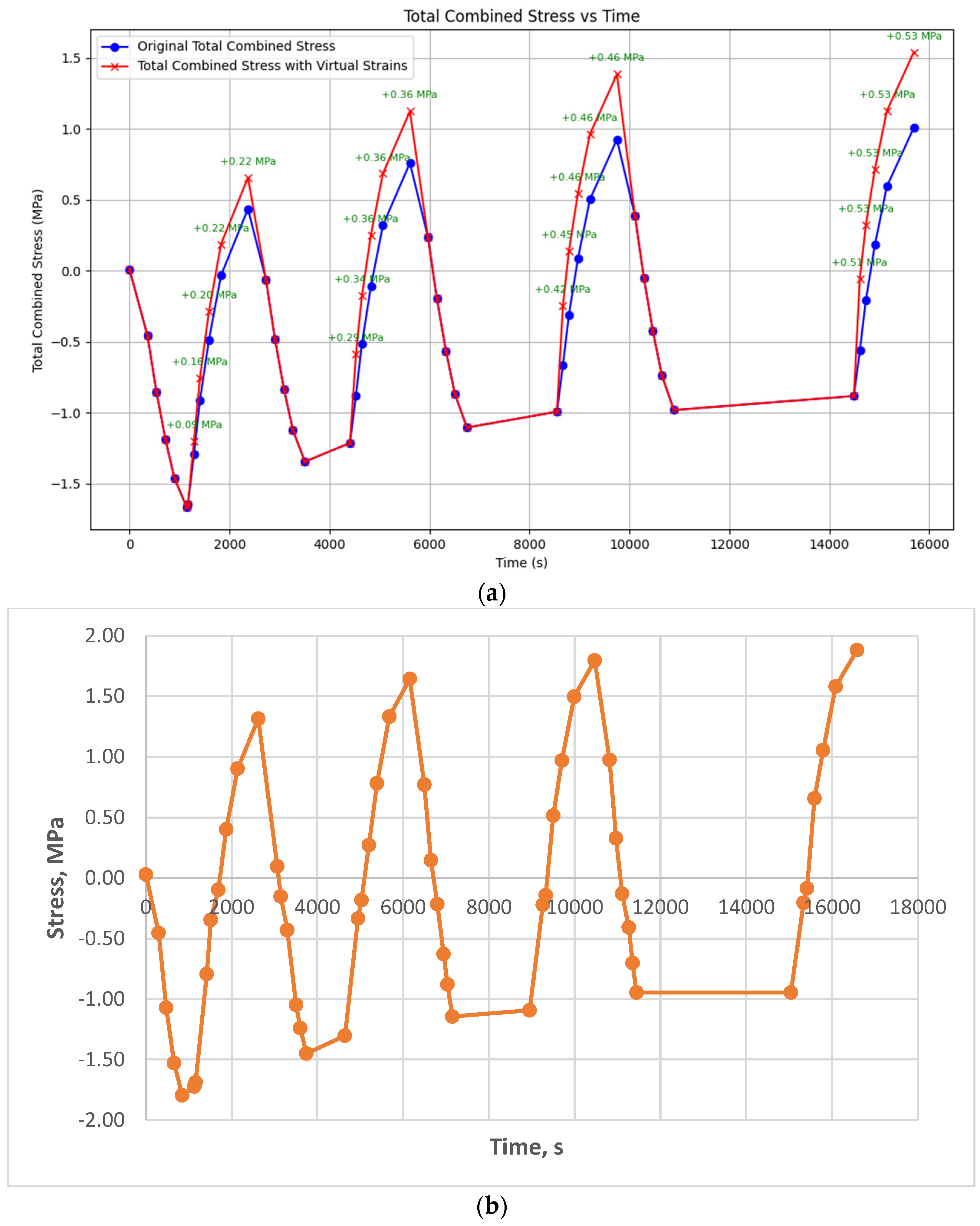

3.2. Experimental Studies of Unreinforced Epoxy Polymer Under Cyclic Thermomechanical Loading

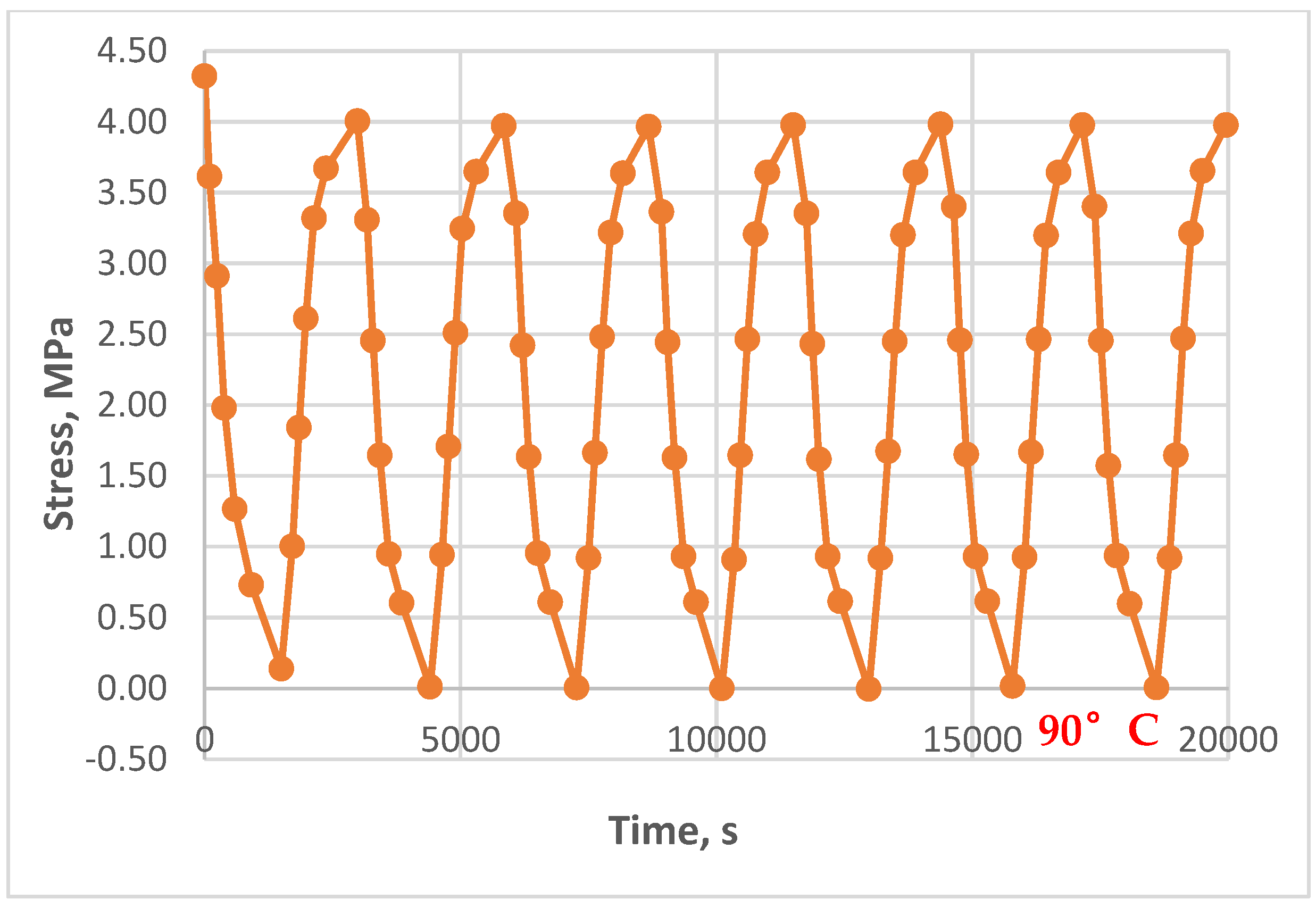

- At different maximum heating temperatures (some were heated to 90°C, others to 80°C).

- At different holding times (from 5 to 90 minutes) at a constant maximum temperature.

- At different initial tensile stresses (from 0 to 4.3 MPa).

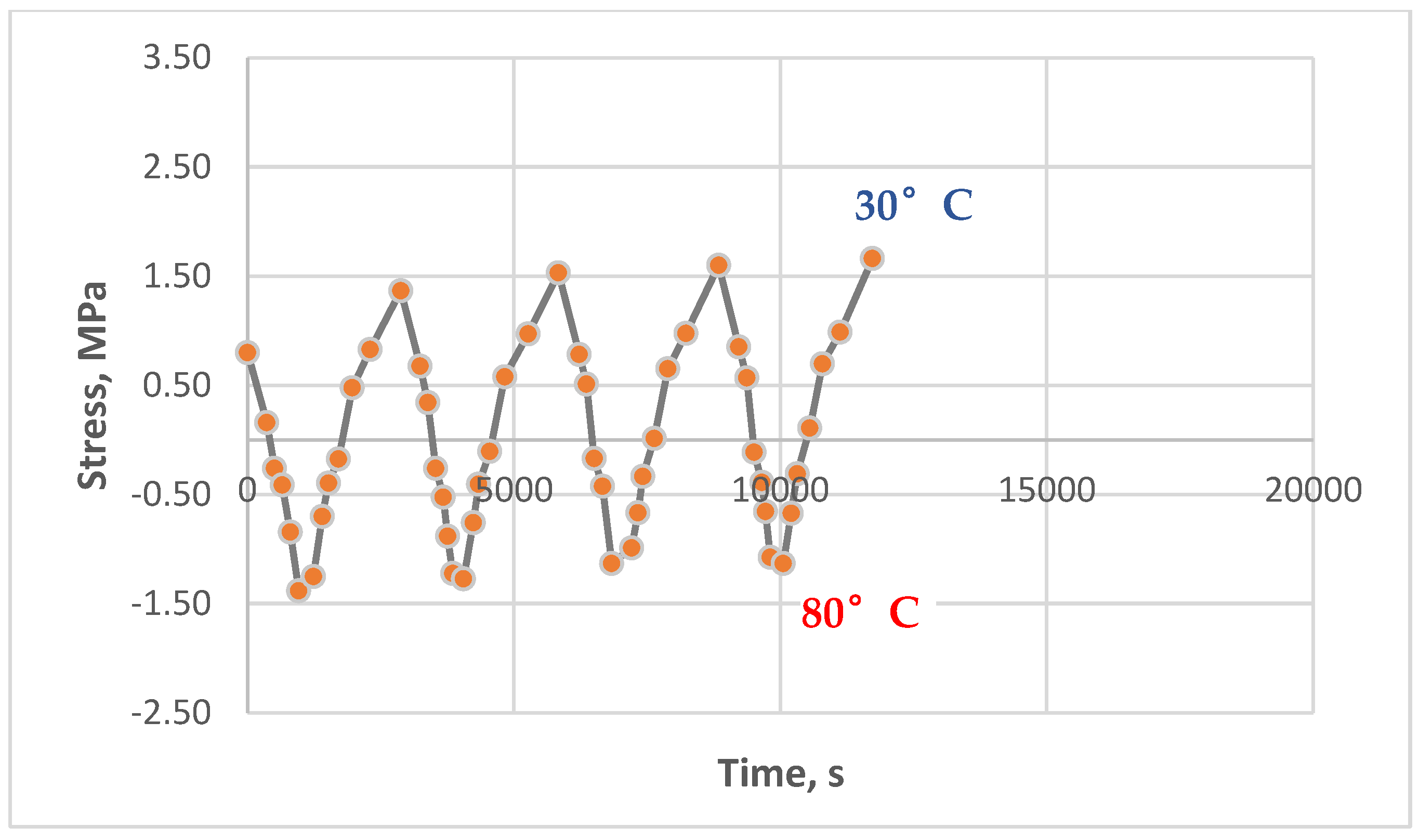

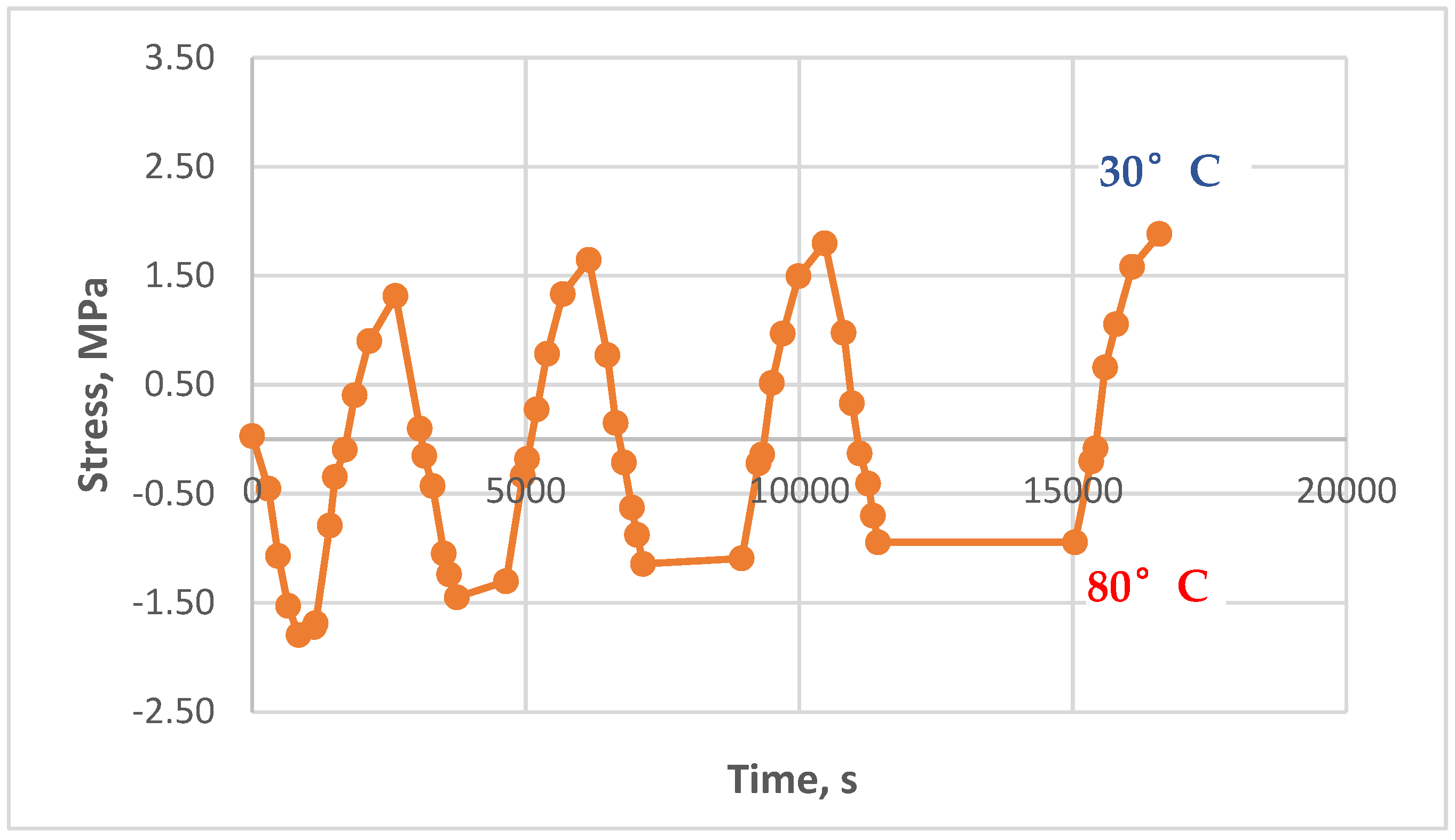

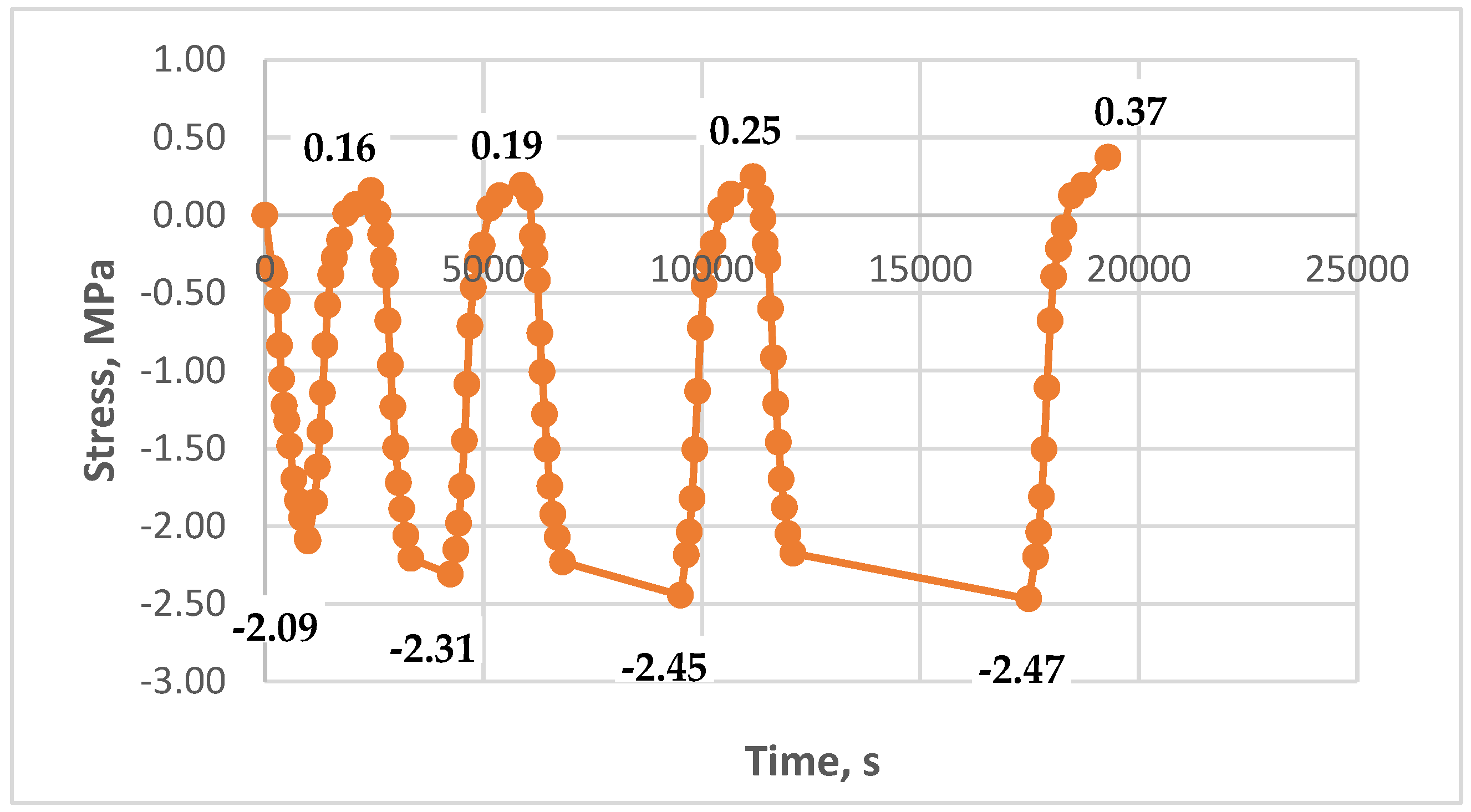

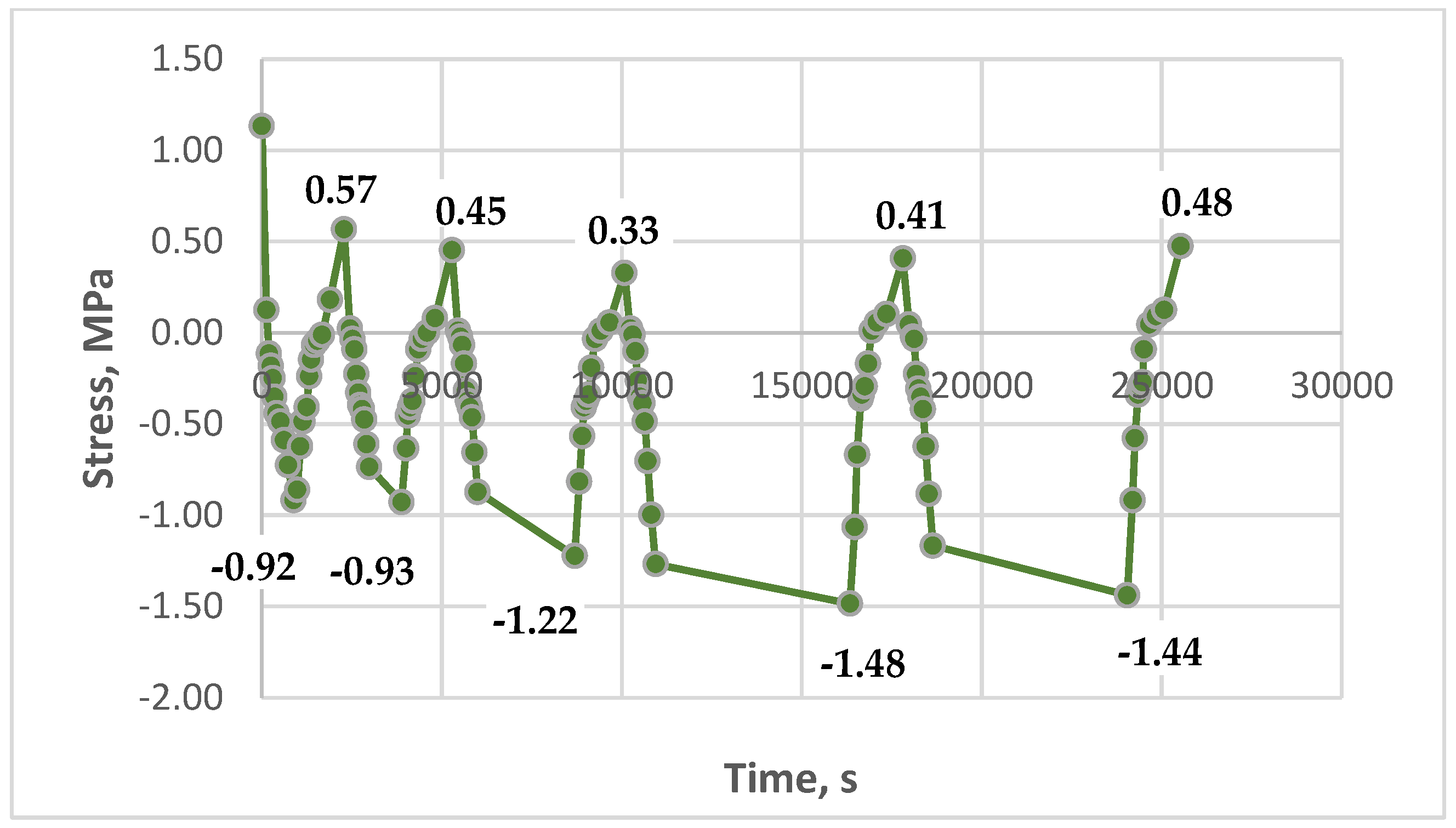

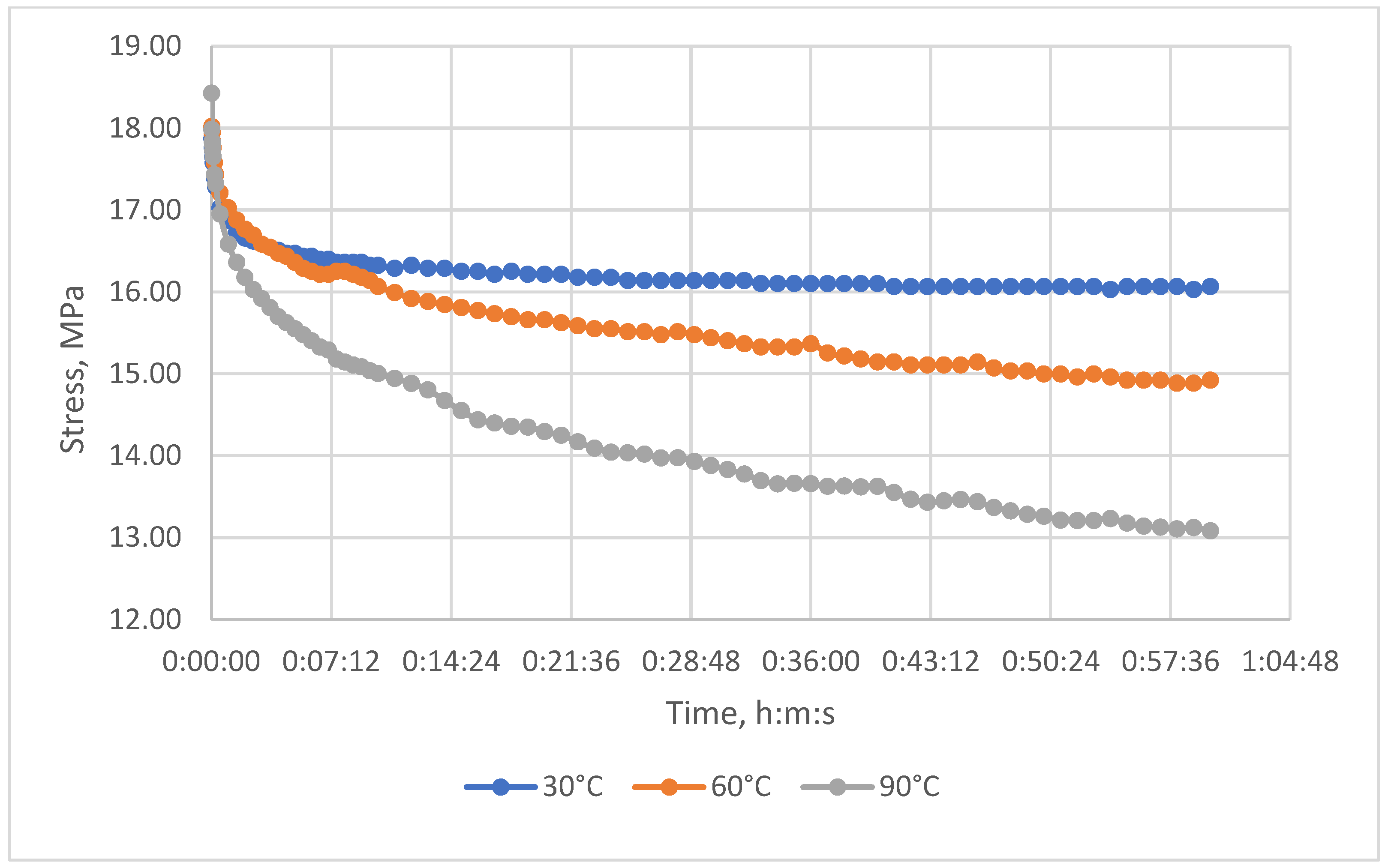

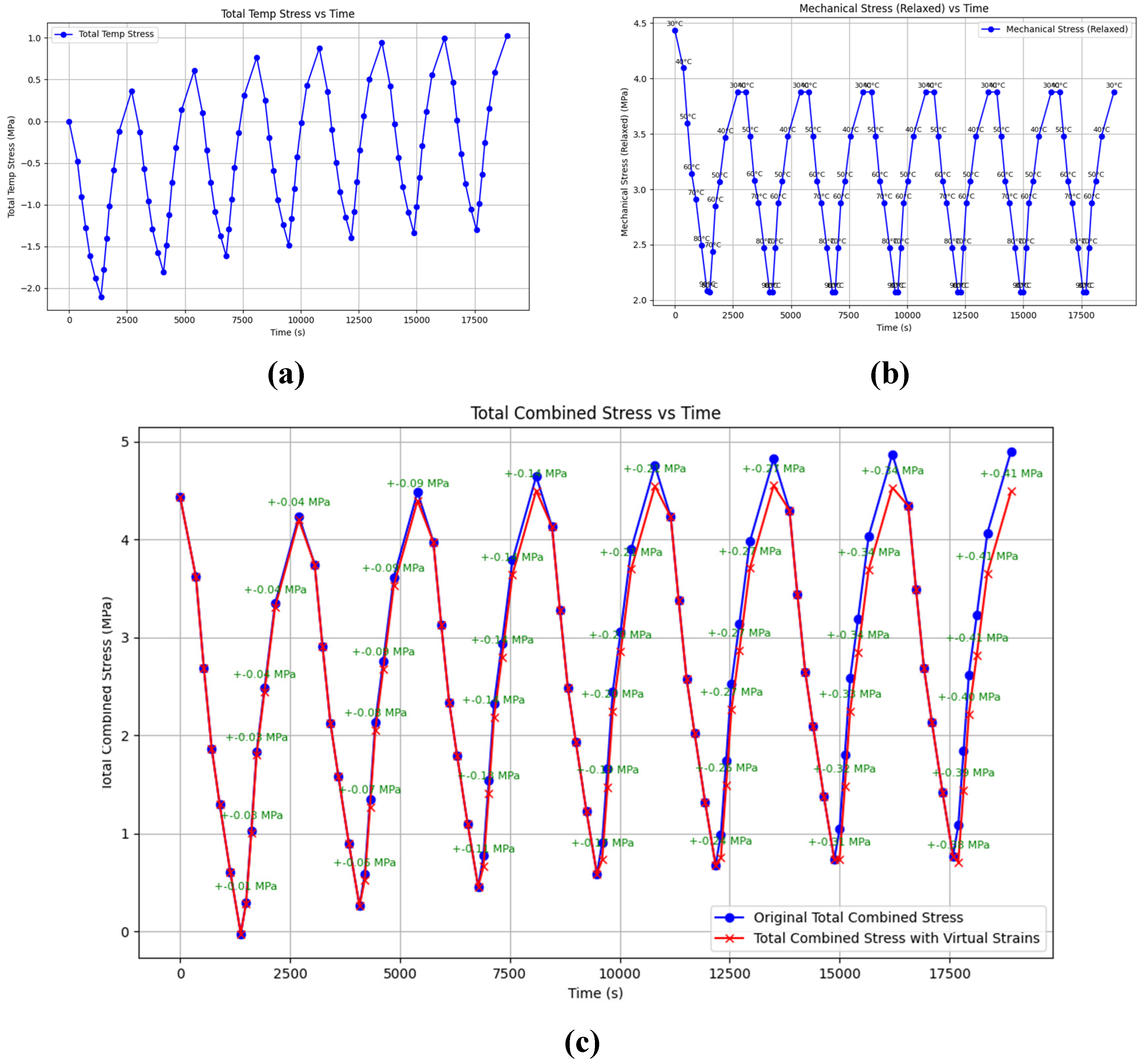

3.3. Results of Experimental Studies of Glass-Reinforced Plastic Under Cyclic Thermomechanical Loading

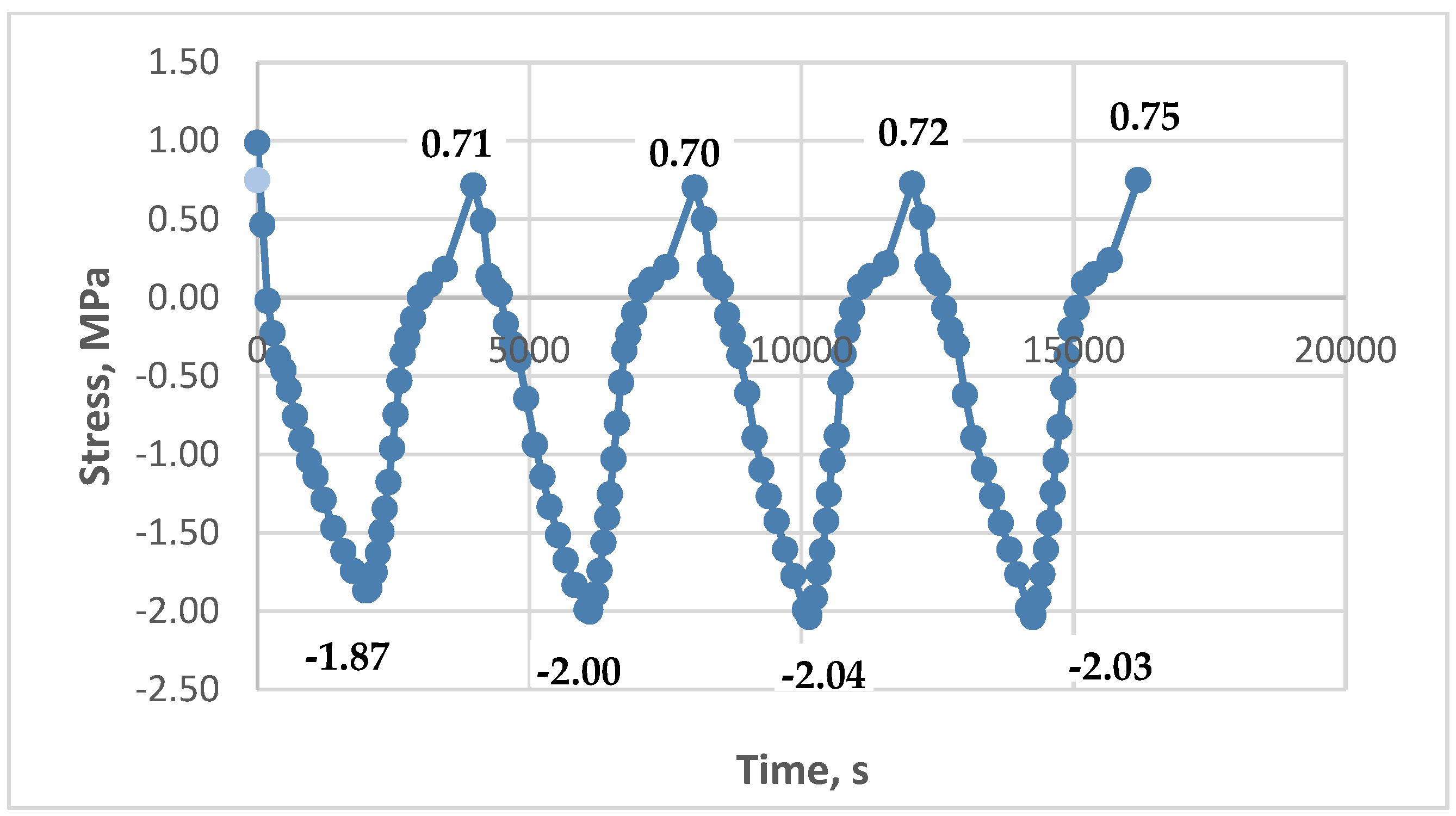

3.4. Modeling Cyclic Thermomechanical Loading on Unreinforced Epoxy Polymer

- The blue curve is the stress curve without accounting for additional stresses from virtual deformations considered in the proposed model.

- The red curve is the stress curve accounting for stresses from virtual deformations.

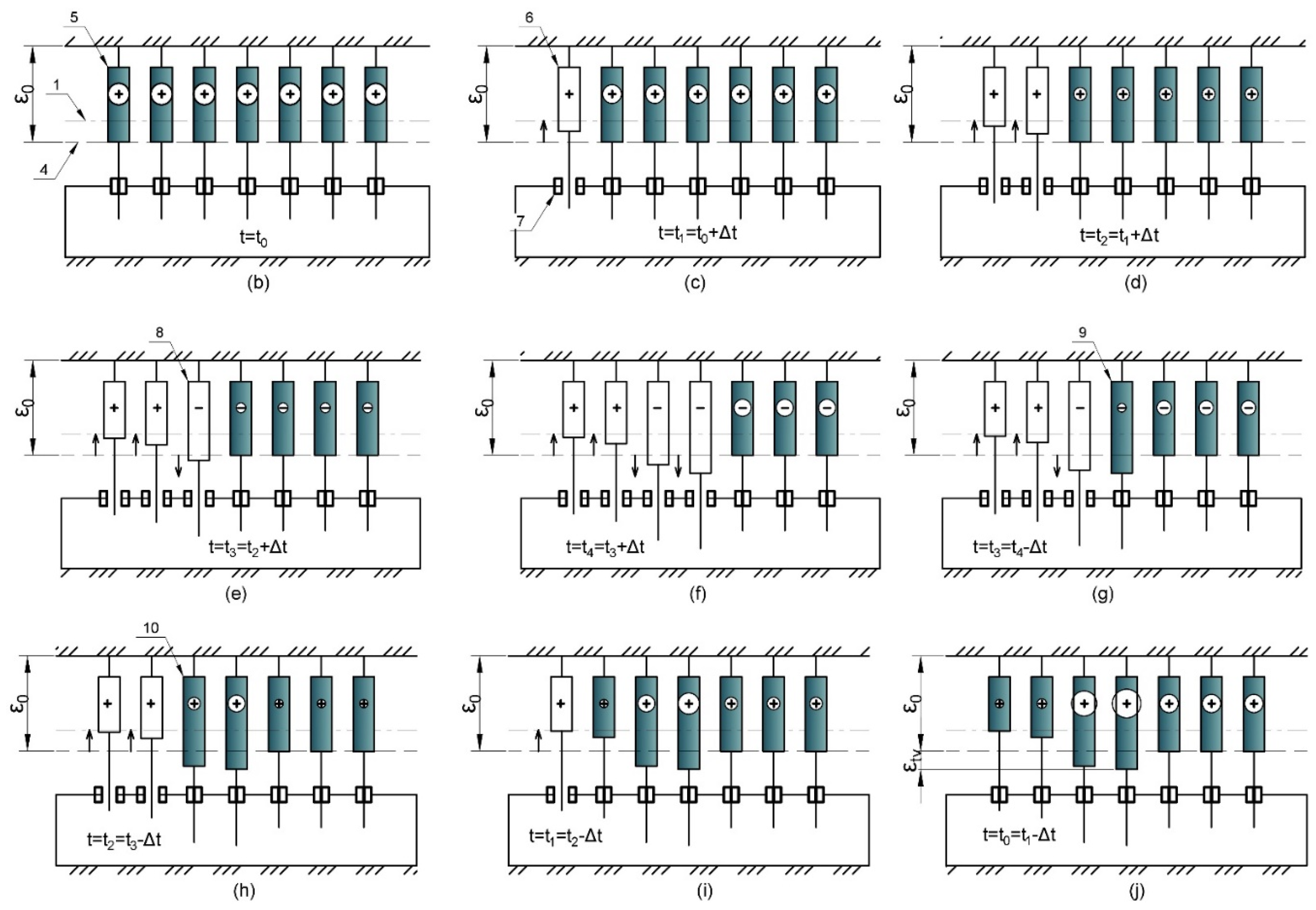

- 1 —

- conditional line of neutral position of cells;

- 2 —

- cell in neutral position;

- 3 —

- conditional thermal brake in the on state.

- Stage (c) – application of mechanical tensile load.

- Stages (d), (e), (f) – heating.

- Stages (g), (h), (i) – cooling.

- Stage (j) – return to the initial temperature.

- 4 —

- conditional line denoting the stretched position of cells under mechanical load;

- 5 —

- connected cell with tensile (positive) stresses;

- 6 —

- disconnected cell upon reaching a certain temperature tn, in which there were tensile stresses before disconnection;

- 7 —

- conditional thermal brake in the off state;

- 8 —

- disconnected cell upon reaching a certain temperature tn, in which there were compressive stresses before disconnection;

- 9 —

- cell reconnected during cooling with reduced positive stresses redistributed in the disconnected state;

- 10 —

- cell reconnected during cooling with accumulated positive stresses.

4. Discussion

- At low initial mechanical stresses (from 0 to 1.5 MPa), significant accumulation of residual tensile stresses is observed in the epoxy polymer.

- Maximum residual stresses exceed the initial ones by 1.7–2.7 times, reaching values up to 1.9 MPa at zero initial stresses and up to 2.1 MPa at initial stresses of 0.8 MPa.

- The presence of holds at the maximum temperature (up to 90 minutes) enhances the effect of residual stress accumulation.

- At high initial tensile stresses (about 4 MPa), exceeding thermal stresses, residual stress accumulation is not observed. This is because relaxation processes at elevated temperatures compensate for possible residual stress accumulation.

- In the glass-reinforced plastic based on the epoxy polymer, the effect of residual stress accumulation is significantly weaker. Maximum residual stresses in the glass-reinforced plastic did not exceed 0.2–0.3 MPa, which is less than 10% of the initial stresses. Reinforcement with glass fabric increases the material's stiffness and reduces the coefficient of thermal expansion, which reduces the influence of thermal cycles.

- The developed multi-element model based on the three-element Kelvin–Voigt model satisfactorily describes experimental data for the epoxy polymer. The model allows accounting for the memory effect on thermomechanical loading and predicting the accumulation of residual stresses depending on initial conditions and parameters of heating and cooling cycles.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Mishnev, M., Korolev, A., Zadorin, A. and Astashkin, V. (2024) Cyclic Thermomechanical Loading of Epoxy Polymer: Modeling with Consideration of Stress Accumulation and Experimental Verification. Polymers, 16, 910. [CrossRef]

- Astashkin, V.M. and Mishnev, M. V. (2016) On the Development of the Manufacturing Technology of Fiberglass Cylindrical Shells of Gas Exhaust Trunks by Buildup Winding. Procedia Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Astashkin V.M., Shmatkov S.B. and Shmatkov A.S. (2015) Polymer Composite Gas Exhaust Pipes in Chimneys of Large-Scale Power Industry. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Ser. Construction Engineering and Architecture, 15, 20–25. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/gazootvodyaschie-stvoly-iz-polimernyh-kompozitov-v-dymovyh-trubah-bolshoy-energetiki.pdf.

- Makarov, V.G. (2004) Application of GRP for Chimney Liners Exposed to Sulfur Dioxide and Sufur Trioxide. Annual Technical Conference - ANTEC, Conference Proceedings.

- Zhang, D.H. and Wang, J.H. (2013) The FRP Chimney Design and Construction Technology for Coal-Fired Power Plant FGD System. Frontiers of Energy and Environmental Engineering - Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Frontiers of Energy and Environmental Engineering, ICFEEE 2012. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, V.P. (2005) Resurgence in Corrosion-Resistant Composites. Reinforced Plastics, 49. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, V.P. (2011) Getting Ducts in a Row with Corrosion-Resistant FRP. Reinforced Plastics, 55. [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, W. (1976) FRP WIDENS USE IN ENERGY SYSTEMS. Power, 120, 79–81.

- Makarov, V.G. and Sinelnikova, R.M. (2007) Application of Composites in the Sulfur Acid Production. Annual Technical Conference - ANTEC, Conference Proceedings.

- Honga, S.J., Honga, S.H. and Doh, J.M. (2007) Materials for Flue Gas Desulfurization Systems Operating in Korea and Their Failures. Materials at High Temperatures. [CrossRef]

- Astashkin V.M. and Likholetov V.V. (1985) Residual Stress Formation in Plastic Elements of Structures during Heat Changes in Conditions of Constrained Deformation. Izvestiya Vuzov. Construction and Architecture, 10, 128–131.

- Astashkin V. M. and Tereshchuk S. V. (1991) Methods of Description of Stressed State of Structures from Laminated Plastics under Axisymmetric Alternating Thermal Influence. Investigations on Building Materials, Constructions and Mechanics: Collection of Scientific Works, 21–26.

- Kim, C., Kim, Y.-G. and Choe, U. (2002) Analysis of Thermo-Viscoelastic Residual Stresses and Thermal Buckling of Composite Cylinders. Transactions of the Korean Society of Mechanical Engineers A, 26, 1653–1665. [CrossRef]

- Coules, H.E., Horne, G.C.M., Abburi Venkata, K. and Pirling, T. (2018) The Effects of Residual Stress on Elastic-Plastic Fracture Propagation and Stability. Materials and Design, 143. [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, N., Xin, H. and Veljkovic, M. (2021) Effects of Residual Stresses on Fatigue Crack Propagation of an Orthotropic Steel Bridge Deck. Materials and Design, 198. [CrossRef]

- Shokrieh, M.M. (2014) Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, B. (2020) Influence of Residual Stresses on Mechanical Behavior of Polymers. Plastics Products Design Handbook. [CrossRef]

- Shokrieh, M.M. and Safarabadi, M. (2021) Understanding Residual Stresses in Polymer Matrix Composites. Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, R. and Koplin, C. (2014) Measuring and Modelling Residual Stresses in Polymer-Based Dental Composites. Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. [CrossRef]

- Dai, F. (2014) Understanding Residual Stresses in Thick Polymer Composite Laminates. Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. [CrossRef]

- (2020) Formation and Test Methods of the Thermo-Residual Stresses for Thermoplastic Polymer Matrix Composites. Civil, Architecture and Environmental Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Rzanitsyn A.R. (1968) Theory of Creep. Stroyizdat, Moscow.

- Ferry, J.D. (1980) Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. [CrossRef]

- Evaristo Riande, Ricardo Diaz-Calleja, Margarita G. Prolongo, Osa M. Masegosa and Catalina Salom. (2000) Polymer Viscoelasticity: Stress and Strain in Practice. Marcel Dekker, Inc. .

- Zhang, M., Zhang, S., Xie, H. and Li, S. (2021) Micromechanical Analysis and Experimental Studies of Thermal Residual Stress Forming Mechanism in FRP Composites. Applied Composite Materials, 28. [CrossRef]

- Shokrieh, M.M. and Kamali Shahri, S.M. (2021) Modeling Residual Stresses in Composite Materials. Residual Stresses in Composite Materials, Elsevier, 193–213. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, G., Tang, A., Yang, Z., Li, S., Li, Y. and Song, D. (2018) Evolution of Curing Residual Stresses in Composite Using Multi-Scale Method. Composites Part B: Engineering, 155. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.T., Zhang, M., Li, S.X., Pavier, M.J. and Smith, D.J. (2016) Residual Stresses Created during Curing of a Polymer Matrix Composite Using a Viscoelastic Model. Composites Science and Technology, 130. [CrossRef]

- Abouhamzeh, M., Sinke, J. and Benedictus, R. (2019) Prediction Models for Distortions and Residual Stresses in Thermoset Polymer Laminates: An Overview. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. [CrossRef]

- Di Landro, L. and Pegoraro, M. (1996) Evaluation of Residual Stresses and Adhesion in Polymer Composites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, Elsevier, 27, 847–853. [CrossRef]

- Chava, S. and Namilae, S. (2021) Continuous Evolution of Processing Induced Residual Stresses in Composites: An in-Situ Approach. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 145. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M. and Schile, R.D. (1982) An Investigation of Material Variables of Epoxy Resins Controlling Transverse Cracking in Composites. Journal of Materials Science. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Han, X., Duan, S. and Liu, G.R. (2021) A Two-Stage Genetic Algorithm for Molding Parameters Optimization for Minimized Residual Stresses in Composite Laminates During Curing. Applied Composite Materials, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M.M.A., Shirinzadeh, B., Zhao, P. and Shi, Y. (2022) Optimization of Process-Induced Residual Stresses in Automated Manufacturing of Thermoset Composites. Aerospace Science and Technology, 123. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S., Taheri-Behrooz, F. and Shokrieh, M.M. (2014) Characterization of Residual Stresses in a Thin-Walled Filament Wound Carbon/Epoxy Ring Using Incremental Hole Drilling Method. Composites Science and Technology, 94. [CrossRef]

- Turusov, R.A. and Stratonova, M.M. (1971) Temperature Stresses in Nonuniformly Heated Polymer Rods. Polymer Mechanics, 3, 624–625. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.A. (1973) Effects of Thermal Loading on Fiber-Reinforced Composites With Constituents of Differing Thermal Expansivities. Journal of Engineering Materials and Technology, 95, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, I.A. and Xie, T. (2010) Shape Memory Epoxy: Composition, Structure, Properties and Shape Memory Performances. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 20. [CrossRef]

- Xin, X., Liu, L., Liu, Y. and Leng, J. (2019) Mechanical Models, Structures, and Applications of Shape-Memory Polymers and Their Composites. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F. and Wang, Z.D. (2009) Review on Thermomechanical Constitutive Model of Shape Memory Polymers. Gaofenzi Cailiao Kexue Yu Gongcheng/Polymeric Materials Science and Engineering.

- Lexcellent, C., Butaud, P., Foltête, E. and Ouisse, M. (2017) A Review of Shape Memory Polymers Thermomechanical Modelling: Analysis in the Frequency Domain. Advanced Structured Materials. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Liu, L., Fei, F., Wang, Y., Liu, Y. and Leng, J. (2013) Modeling Mechanical Behavior of Epoxy-Shape Memory Polymers. Behavior and Mechanics of Multifunctional Materials and Composites 2013. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K., McClung, A.J.W., Tandon, G.P., Baur, J.W. and Jerry Qi, H. (2014) A Thermomechanical Constitutive Model for an Epoxy Based Shape Memory Polymer and Its Parameter Identifications. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., Yin, Y. and Liu, J. (2021) A Fractional Finite Strain Viscoelastic Model of Dielectric Elastomer. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 100, 564–579. [CrossRef]

- Meral, F.C., Royston, T.J. and Magin, R. (2010) Fractional Calculus in Viscoelasticity: An Experimental Study. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 15, 939–945. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.-J. (2020) Fractional Derivative Models for Viscoelastic Materials at Finite Deformations. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 190, 226–237. [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. and Spada, G. (2011) Creep, Relaxation and Viscosity Properties for Basic Fractional Models in Rheology. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 193, 133–160. [CrossRef]

- John D. Ferry. (1980) VISCOELASTIC PROPERTIES OF POLYMERS. THIRD EDITION., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Majda, P. and Skrodzewicz, J. (2009) A Modified Creep Model of Epoxy Adhesive at Ambient Temperature. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 29. [CrossRef]

- Seyedkazemi, M., Wenqi, H., Jing, G., Ahmadi, P. and Khajehdezfuly, A. (2024) Auxetic Structures with Viscoelastic Behavior: A Review of Mechanisms, Simulation, and Future Perspectives. Structures, 70, 107610. [CrossRef]

- National Standard GOST 19907–83 Dielectric Fabrics Made of Glass. Twister Complex Threads. Specifications.

- (1981) National Standard GOST 9550-81 Plastics. Methods for Determination of Elasticity Modulus at Strength, Compression and Bending.

- Storn, R. and Price, K. (1997) Differential Evolution - A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. Journal of Global Optimization, 11. [CrossRef]

- Turusov R. A. and Andreevskaya G. D. (1979) Isothermal Relaxation of Temperature Stresses in Rigid Mesh Polymers. Reports of the Academy of Sciences, 247, 1381–1383.

| Model relaxation curve | Time interval, s | E1, MPa | E2, MPa | η, MPa*s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

t=30°C σ0 = 4.2MPa |

|

0-60 | 3045 | 381810 | 3.57e+07 |

| 60-120 | 3056 | 238874 | 7.40e+06 | ||

| 120-400 | 3046 | 228618 | 1.45e+07 | ||

| 400-900 | 3060 | 404890 | 6.75e+07 | ||

| 900-3600 | 3054 | 301349 | 1.20e+08 | ||

|

t=60°C σ0 = 4.2MPa |

|

||||

| 0-60 | 2783 | 35982 | 1.00e+06 | ||

| 60-120 | 2761 | 194441 | 7.04e+06 | ||

| 120-400 | 2764 | 94170 | 9.87e+06 | ||

| 400-1500 | 2779 | 42637 | 2.04e+07 | ||

| 1500-3600 | 2760 | 51894 | 5.67e+07 | ||

|

t=90°C σ0 = 4.2MPa |

|

0-60 | 1658 | 315760 | 2.55e+07 |

| 60-90 | 1668 | 23270 | 1.00e+06 | ||

| 90-180 | 1661 | 10338 | 1.26e+06 | ||

| 180-360 | 1654 | 12222 | 2.39e+06 | ||

| 360-600 | 1658 | 13711 | 3.89e+06 | ||

| 600-1500 | 1667 | 10000 | 4.76e+06 | ||

| 1500-3600 | 1668 | 10000 | 8.63e+06 | ||

| Model / experimental relaxation curve | Time interval, s | E1, MPa | E2, MPa | η, MPa*s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

t=30°C σ0 = 5.6MPa |

|

0-60 | 10783 | 124579 | 1.00e+06 |

| 60-120 | 10689 | 705152 | 2.20e+07 | ||

| 120-600 | 10730 | 653221 | 4.63e+07 | ||

| 600-900 | 10683 | 999732 | 2.60e+08 | ||

| 900-3600 | 10773 | 774976 | 3.64e+08 | ||

|

t=60°C σ0 = 5.6MPa |

|

||||

| 0-60 | 7827 | 348725 | 1.82e+08 | ||

| 60-90 | 7833 | 317182 | 1.41e+07 | ||

| 90-180 | 7821 | 314093 | 3.64e+07 | ||

| 180-360 | 7825 | 208479 | 6.71e+07 | ||

| 360-600 | 7810 | 303202 | 1.42e+08 | ||

| 600-1500 | 7814 | 174597 | 1.97e+08 | ||

| 1500-3600 | 7832 | 139584 | 3.16e+08 | ||

|

t=90°C σ0 = 5.6MPa |

|

0-60 | 7105 | 65605 | 1.00e+06 |

| 60-90 | 7048 | 167061 | 8.48e+06 | ||

| 90-180 | 7101 | 143522 | 1.97e+07 | ||

| 180-360 | 7072 | 161122 | 4.50e+07 | ||

| 360-600 | 7091 | 128993 | 6.95e+07 | ||

| 600-1500 | 7077 | 100500 | 1.12e+08 | ||

| 1500-3600 | 7082 | 167416 | 2.67e+08 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).