1. Introduction

Mediterranean ecosystems are biodiversity hotspots, hosting numerous endemic species and playing a vital role in global conservation efforts, despite facing significant habitat loss and environmental challenges [

1]. These ecosystems are also ecologically fragile due to their unique climatic conditions, characterized by dry summers and mild, wet winters [

2]. Their fragility is further heightened by the introduction of invasive plant species, a process often driven by human activity. These plants, introduced either accidentally through trade or intentionally for purposes such as agriculture, gardening, or erosion control, often thrive in new environments due to the lack of natural predators, pathogens, or competitors [

3]. Specifically, humans have intentionally introduced non-native plants to address various environmental issues, such as organic matter loss and desertification, particularly in ecosystems located on slopes or degraded landscapes [

4]. However, invasive plant species are a major global concern due to their ability to reduce biodiversity and alter ecological processes [

5]. Moreover, climatic conditions (wind and rain) as well as animals (birds and insects) further contribute to the spread of seeds of invasive plant species [

6], which can outcompete native species, modify trophic interactions [

7], and shift ecosystem dynamics and balances [

8,

9,

10].

The interaction between invasive plants and soil is particularly concerning. Invasive species can alter soil physical structure and chemical composition, impacting nutrient cycles, pH, and organic matter quality [

11,

12]. Changes in soil characteristics can significantly alter soil microbial and microarthropod communities, critical components of ecosystem functions. By introducing litter with novel chemical properties or exuding unique root metabolites [

13], invasive plants can suppress beneficial microbial populations while promoting pathogenic or generalist fungi [

14,

15]. The resulting shifts in microbial diversity and function can alter microbial-mediated processes and form positive feedback loops, reinforcing the dominance of invasive species while degrading soil health and resilience [

16,

17,

18]. These disruptions in microbial communities also cascade into changes in soil microarthropods, which are strictly connected to microbial processes [

19,

20]. The changes in microbial and microarthropod assemblages can impact soil resilience, making ecosystems more vulnerable to disturbances such as droughts, floods, or human interventions [

21,

22]. Furthermore, the loss of native soil biodiversity can create feedback loops that reinforce the dominance of invasive plants, locking ecosystems into degraded states.

While many studies have focused on the aboveground impacts of invasive plants, few studies have comprehensively examined the interactions among soil characteristics, microorganisms and microarthropods. This research aimed to fill this gap by investigating how invasive plants simultaneously influence soil abiotic characteristics, microbial and Collembola communities. In particular, this study investigated the impact of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) and tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima Mill.) on soil physical and chemical characteristics, microbial abundance and activities, and microarthropod communities, particularly Collembola, in comparison with native vegetation such as holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) and herbaceous mediterranean vegetation. The hypotheses behind were i) both the investigated invasive plants, increased the content of nutrient and organic matter in soil and ii) increased as well microbial biomass and activities and the biodiversity of soil microarthropods and Collembola community. By linking aboveground vegetation changes to belowground dynamics, the research aimed to clarify the ecological consequences of plant invasions and their implications for soil ecosystem functioning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Plant Species

The study was conducted in the Vesuvius National Park, a protected area known for its diverse ecosystems and unique volcanic soil [

23]. The study area is typically Mediterranean, primarily characterized by herbaceous species (mosses, lichens, sage, and various grass species), shrubs (myrtle, laurel, wayfarer, brambles, and brooms), and trees (holm oak, and pine). Additionally, invasive species such as black locust (

Robinia pseudoacacia L.) and tree of heaven (

Ailanthus altissima Mill.), are present in many areas of Vesuvius National Park [

24].

2.2. Soil Sampling

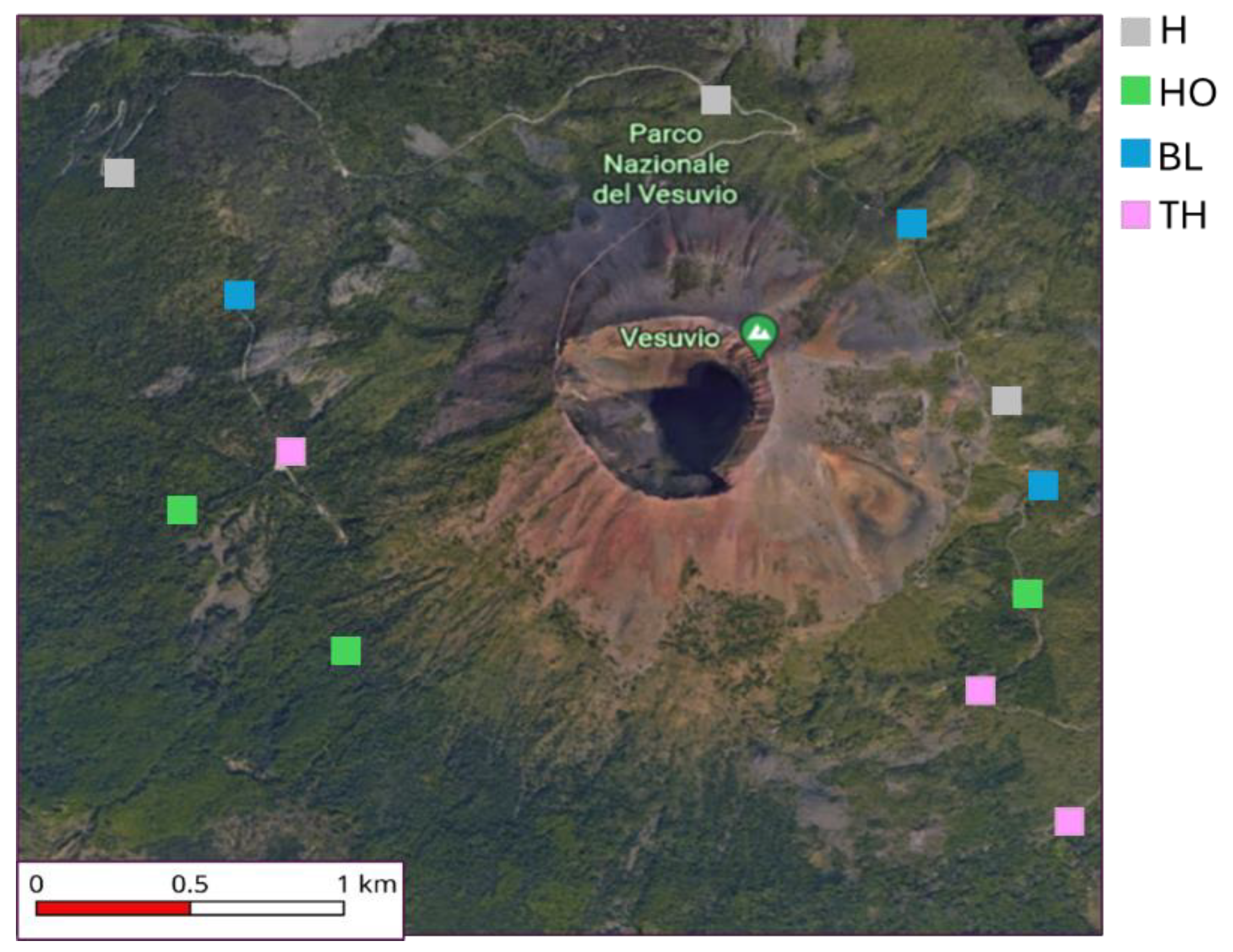

In Fall 2023, soil and microarthropod samplings were performed, after 15 days without rainfall, to minimize the effect of climatic variability. The soil was collected at 12 sites (approximately 400 m

2) equally divided into four different vegetation cover types: herbaceous (H) and holm oak (HO) as native vegetations and black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) as invasive vegetations (

Figure 1). Each site was divided in 3 parcels and from each parcel five soil cores (depth: 10 cm, diameter: 5 cm) used for the soil physical, chemical and microorganism analyses (for a total of 15 soil corers) and five soil corers (depth: 5 cm, diameter: 5 cm) used for the microarthropod analyses (for a total of 15 soil corers), were collected at the four corners of the site and one at the center, after removing litter.

The soil corers collected for the soil physical, chemical and biological analyses were mixed to obtain a homogeneous sample, whereas those collected to extract microarthropods were kept separated. The soil samples were put in sterile bags and transported refrigerated to the laboratory.

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis

In the laboratory, the soil samples were sieved (2 mm mesh size) to perform the analyses. Each soil sample was characterized by pH, water content (WC), total Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N) and organic carbon (Corg) concentrations. Soil pH was measured in a soil:distilled water (1:2.5 = v:v) suspension by an electrometric method. Soil WC was determined gravimetrically drying fresh soil at 105 C until constant weight. For the total C and N concentrations, soil samples were dried in oven at 70°C, until constant weight, and measured using Elemental Analyzer (Thermo Finnigan, CNS Analyzer). For the Corg, soil samples were previously treated with HCl (10%), to exclude carbonates, and then analyzed with Elemental Analyzer (Thermo Finnigan, CNS Analyzer).

2.4. Biological Analyses

2.4.1. Microbial Biomass and Activities

Soil samples intended for biological analyses were stored at 4°C until processing. The bacteria and fungi of the soil microbial community were detected by DNA extraction and subsequent amplification of a specific gene by qPCR [

25]. Total soil DNA (DNA yield) was extracted by the FastDNA™ SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) [

26]. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses were used to quantify the total bacterial (16S rDNA) and total fungal (18S rDNA) sequences in each soil DNA sample. For the total bacterial DNA (16S rDNA) the oligos Eub431f (5′ CCTACG GGAGGCAG 3′) and Eub515r (5′ TACCGCGGC KGCTGGCA 3′) were used for the amplification, respectively [

27]. Whereas the total fungal DNA (18S rDNA) the oligos FF390 (5′ CGATAACGAACGAGACCT 3′) and FR-1 (5′ A[I]CCATTCAATCGGTA[I]T 3’) were used for the amplification [

28]. The microbial respiration was measured using MicroResp® (Macaulay Scientific Consulting, Aberdeen, UK) assays [

29]. Hydrolase activity (HA) was determined by adding fluorescein diacetate (FDA) as substrate as reported by Adam and Duncan [

30]. Dehydrogenase activity (DHA) was determined using 1.5% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) dissolved in 0.1 M TrisHCl buffer (pH 7.5) as reported by Tan et al. [

31]. β-glucosidase activity (β-glu) was determined by adding modified universal buffer (MUB, pH 6) as reported by Tabatabai et al. [

32]. Urease activity (U) was determined using 0.1 M urea as substrate as reported by Kendeler et al. [

33] and Alef et al. [

34].

2.4.2. Microartrhopod and Collembola Community Analyses

Microarthropods were extracted using the Macfadyen extraction method: soil samples are heated from above by hot air and cooled from below. The organisms move down the soil core into the cool air and are collected in containers at the bottom of the extractor. During the 7-day extraction period, a thermal cycle is set whereby the temperature increases from 35°C (for the first two days) to 45°C (for three days), ending at 60°C. Below that, the temperature is maintained at 5°C. At the end of the extraction phase, the samples are stored in a 70% ethanol solution at 4°C. For each site, microarthropods were sorted in Collembola further identified through different keys [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] to the species or genus level and in other groups (Acari, Symhyla, Pauropoda, insect larvae). The data were reported as density (n. org. m

−2), richness (mean taxa number), Shannon index for total microarthropods and Collembola and QBS-ar index for total microarthropods and QBS-c index for Collembola. The abundances of Collembola species or genus and their percentages within the community were also reported as well as the abundance percentages of ecomorphological groups defined by Gisin [

40]. In detail, identified Collembola were assigned to the three which describe their habitat preferences combined with morphological properties: epi-edaphic species are very mobile organisms that mainly live in litter and topsoil, eu-edaphic species are not very mobile and live in soil macropores, and hemi-edaphic species are intermediate.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

As the soil physical-chemical and biological characteristics did not match the basic assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity required for parametric statistics (the Wilk–Shapiro test resulted in a rejection level of α = 0.05), the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test with the Bonferroni adjustment was performed to assess differences soil physical-chemical and biological characteristics among the different vegegtation covers.

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all the investigated soil characteristics assembled in a single matrix, to evaluate the soil sample distributions according to the vegetation covers (Herbaceous, Holm oak, Black locust, Tree of heaven) and to identify the which soil characteristics are typical of each category. Differences in the soil physical-chemical and biological characteristics tested by permutational multivariate analysis of variance using distance matrices (ADONIS).

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.1 (R Development Core Team, 2015) with packages ‘vegan’ [

41] and ‘ade4’[

42].

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physical-Chemical Characteristics

The values of the investigated physical-chemical characteristics in the soils are reported in

Table 1. Particularly, pH ranged between 6.33 and 6.95 showing the highest value in soil under TH and the lowest under HO; WC ranged between 10.6 and 29.5 % d.w. showing the highest values in soil under HO and the lowest under TH; total C content ranged between 3.26 and 4.00 % d.w. showing the highest values in soils under HO and TH and the lowest under BL; C

org content ranged between 1.21 and 2.06 % d.w. showing the highest value in soil under HO and the lowest under TH; finally, total N content ranged between 0.60 and 0.71 % d.w. and did not show signficant differences among soils (

Table 1).

3.2. Soil Biological Characteristics

3.2.1. Microbial Biomass and Activities

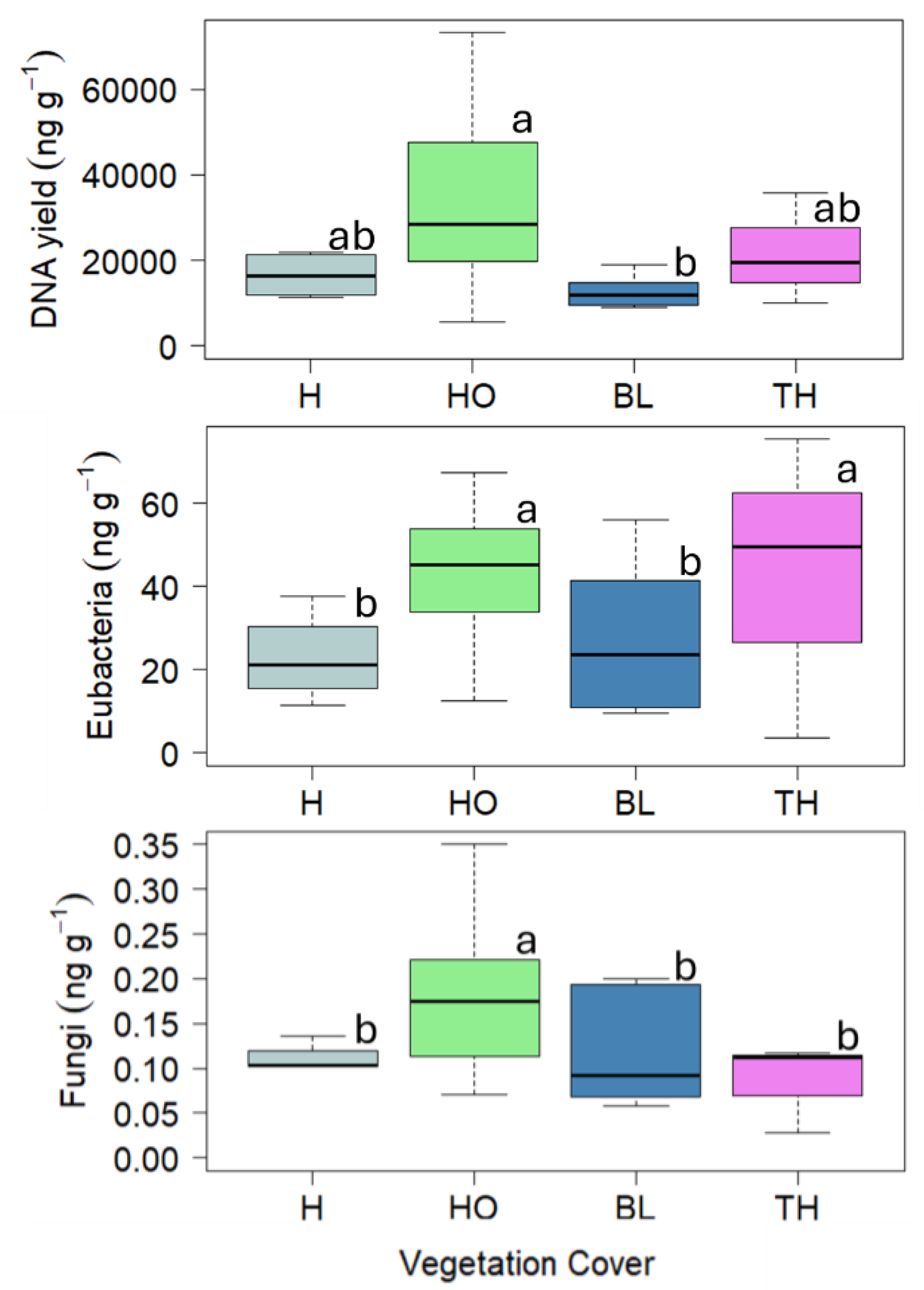

The investigated microbial biomass and activities are reported in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Particularly, DNA yield ranged between 12879 and 34550 ng g

-1 showing the highest value in soil under HO and the lowest under BL; the bacterial biomass ranged between 22.85 and 42.94 ng g

-1 showing the highest values in soils under HO and TH and the lowest under H and BL; the fungal biomass ranged between 0.08 and 0.18 ng g

-1 showing the highest values in soils under HO and the lowest under BL (

Figure 2).

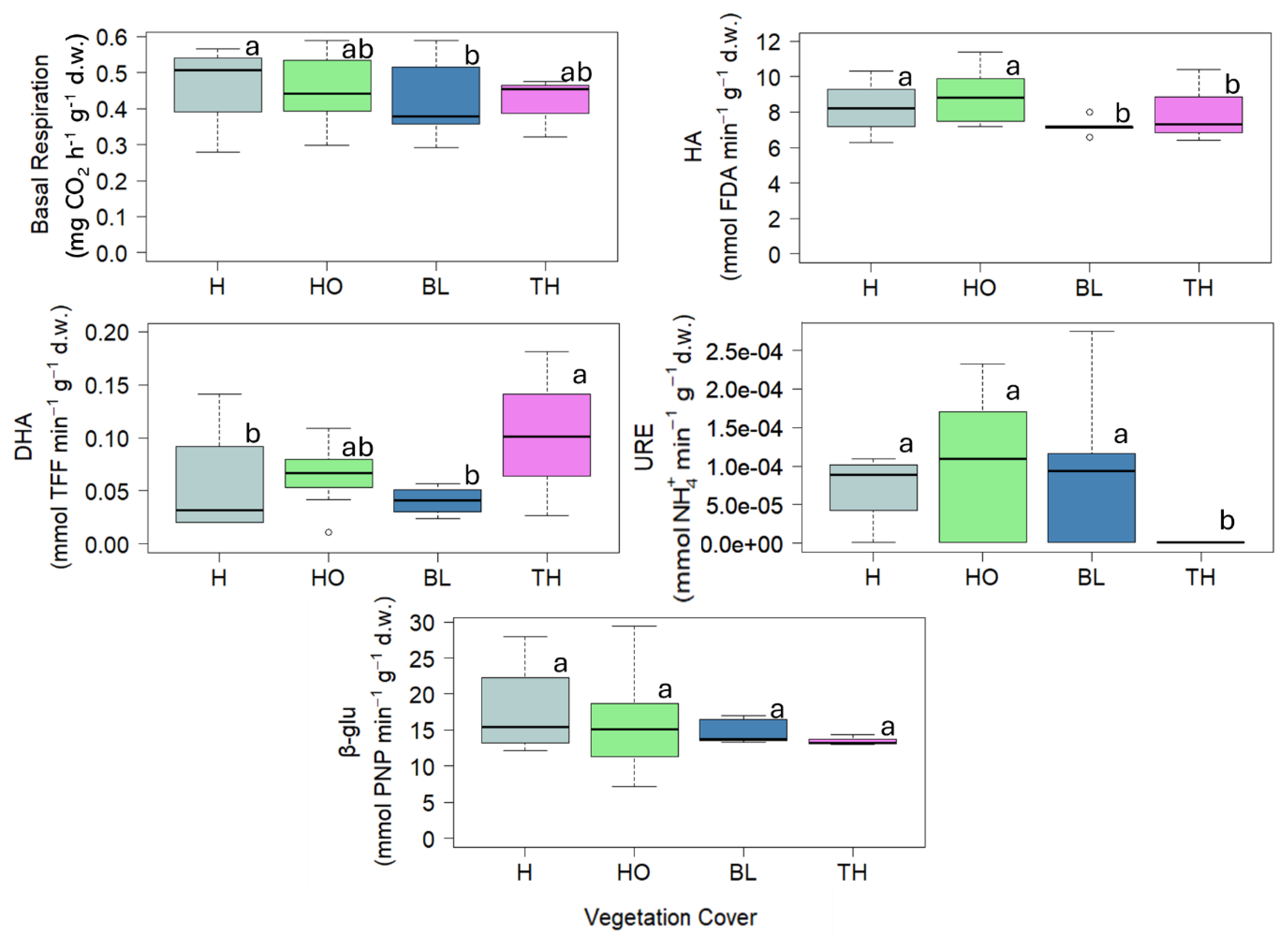

Soil basal respiration ranged between 0.41 and 0.46 mg CO

2 h

-1g

-1 d.w. showing the highest values in soil under H and the lowest under BL; the HA activity ranged between 7.22 and 8.88 mmol FDA min

-1g

-1 d.w. showing the highest value in soil under HO and the lowest under BL; the DHA activity ranged between 0.04 and 0.10 mmol TFF min

-1g

-1 d.w. showing the highest value in soils under TH and the lowest under BL; the URE activity ranged between 1.48E-06 and 9.81E-05 mmol NH

4+ min

-1g

-1 d.w. showing the highest values in soils under H, BL and HO and the lowest under TH; finally, the β-glu activity ranged between 13.49 and 17.73 mmol PNP min

-1g

-1 d.w. did not show any significant difference among the vegetation covers (

Figure 3).

3.2.2. Microartrhopod Community

The values of microartropod taxonomical indices are reported in

Table 2. In particular, microartropod density ranged between 2111 and 8945 n°of organism m

-2 showing the highest value in soil under TH. The microarthropod richness ranged between 6 and 12 n°of taxa, with the highest value under TH and the lowest under BL. Shannon index ranged between 0.73 and 1.41, showing the highest value under TH and the lowest under H. The QBS-ar ranged between 37.4 and 69.3, showing the highest value under TH and the lowest under H (

Table 2).

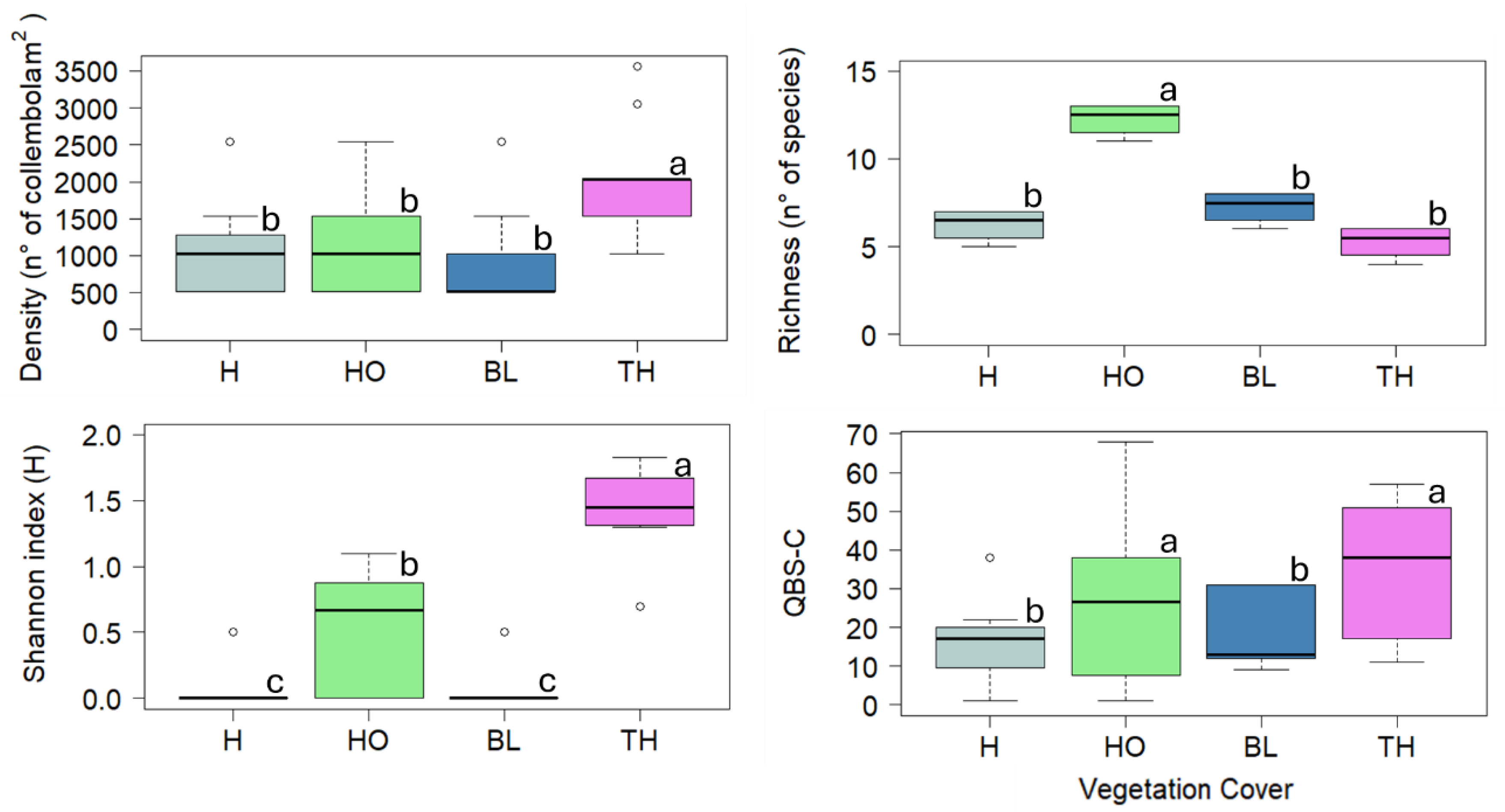

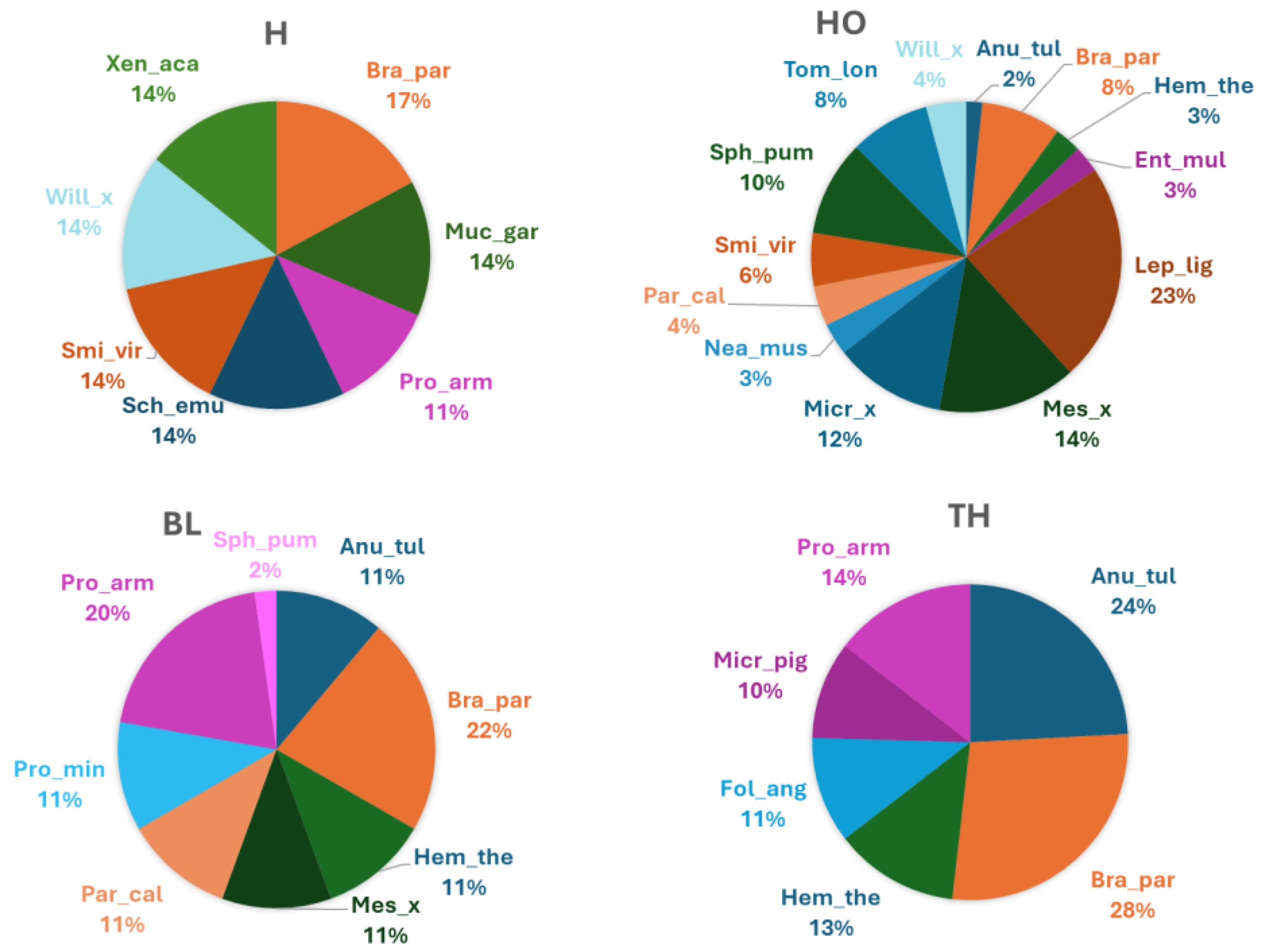

3.2.3. Collembola Community

The values of Collembola taxonomical indices are reported in

Figure 4. The proportion of Collembola regarding the total of microartrhopods is 69 %. In particular, Collembola density ranged between 873 and 2038 n°of organism m

-2 showing the highest values in soils under TH and the lowest under BL; the Collembola richness ranged between 5.25 and 12.5 n°of species or genus showing the highest value in soil under HO and the lowest under TH; Shannon index ranged between 0.08 and 1.41 showing the highest value in soil under TH and the lowest under H and BL; the QBS-c ranged between 15.5 and 34.11 showing the highest values in soil under TH and the lowest under BL (

Figure 4).

In total, 24 species of Collembola were found in the sampled area, with Brachystomella parvula, Anurida tullbergi and Protaphorura armata as the most abundant were in terms of individuals. In particular, in soil under H, 7 Collembola species were found, all with similar relative abundances (ranging from 11 and 17 %), in soil under HO, 11 Collembola species and 2 genus were found with Lepydocyrtus lignorum (23 %), Mesaphorura sp. (14 %) and Micraphorura sp. (12 %) as the most abundant groups (

Figure 5). In soil under BL, 8 Collembola species were found with Anurida tullbergii (11 %), Brachystomella parvula (22 %), Hemistoma thermophila (11 %) and Protaphorura armata (20 %) as the most abundant species, whereas in soil under TH, 6 Collembola species were found with Anurida tullbergii (24 %), Brachystomella parvula (28 %), Hemistoma thermophila (13 %) and Protaphorura armata (14 %) as the most abundant species (

Figure 5).

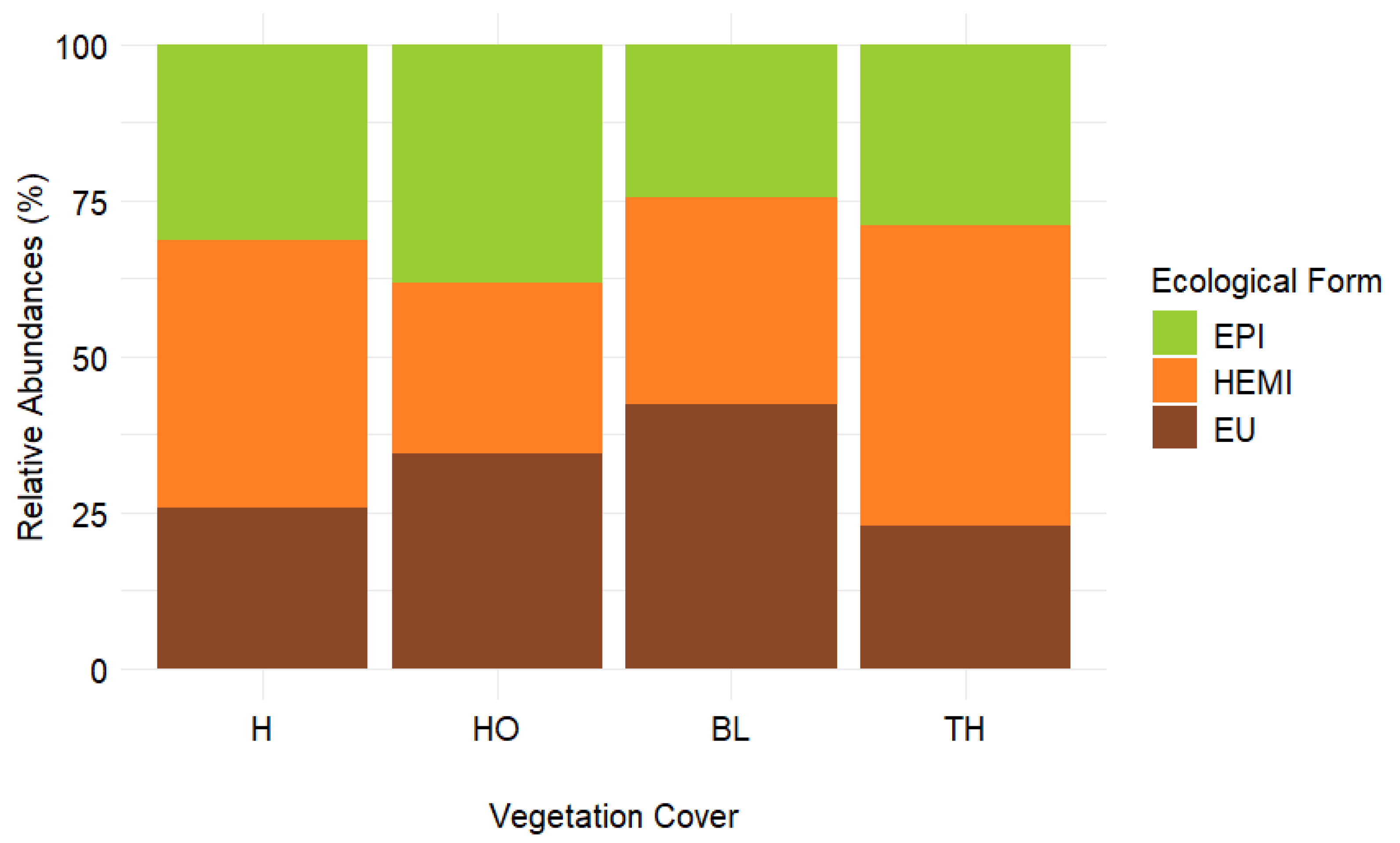

The values of Collembola eco-morphological forms are reported in

Figure 6. In particular, the proportion of eu-edaphic organisms ranged between 22.7 and 42.2 % showing the signifcant highest values in soils BL and the lowest under TH; the proportion of hemi-edaphic organisms ranged between 27.2 and 48.3 % showing the signficant highest values in soil under TH and and the lowest under HO; finally, the proportion of epi-edaphic organisms ranged between 24.4 and 38.3 % showing the signficant highest values in soils under HO and the lowest under BL (

Figure 6).

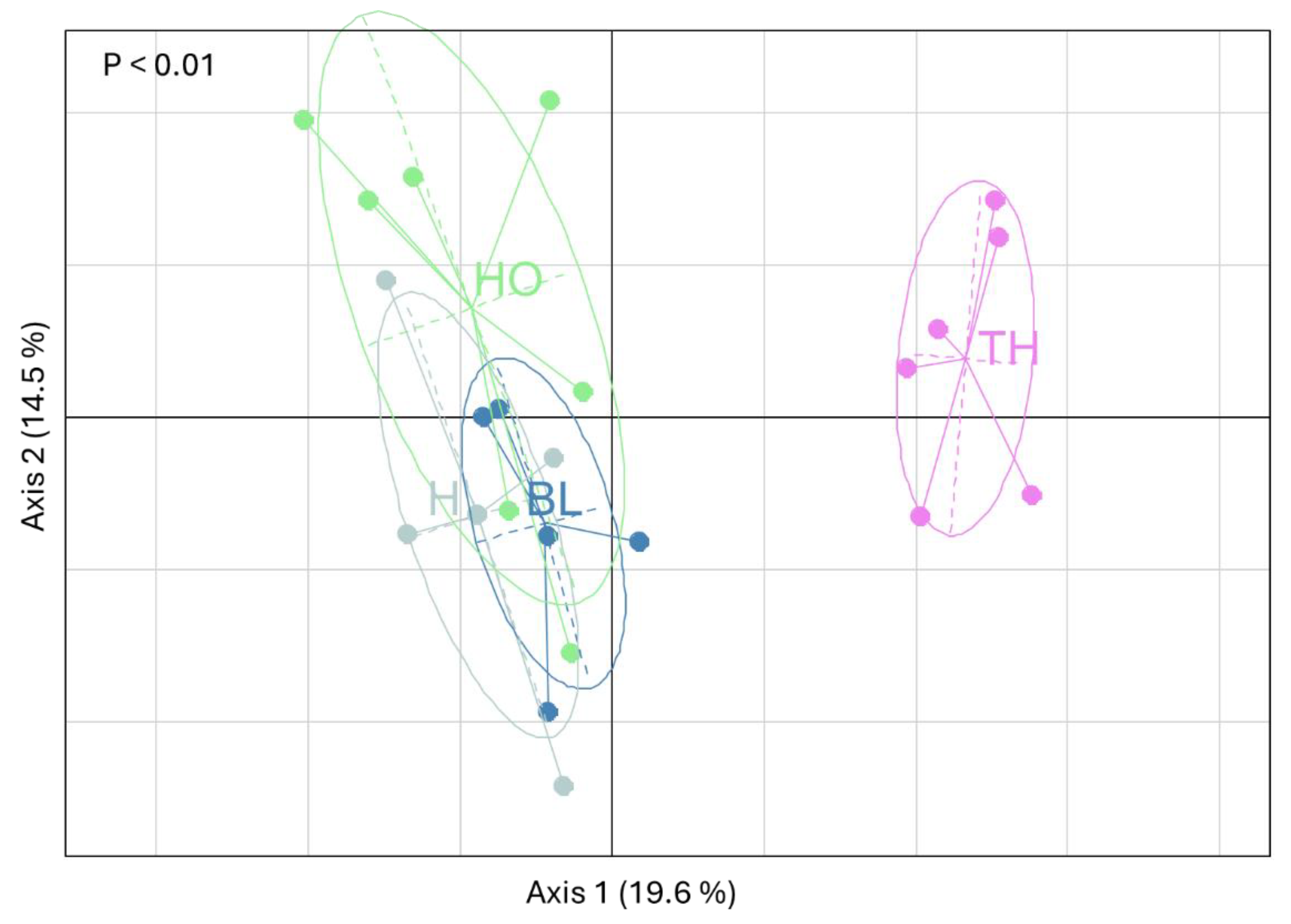

3.3. Impact of Vegetation Cover on Soil Physical-Chemical and Biological Characteristics.

The Principal component analysis (PCA), performed taking into account the abiotic andbiotic soil charactersitics, highlighted that the first two axes accounted, respectively, for 20 % and 25 % of the total variance (

Figure 7).

The first axis clearly separated the soils according to the vegetation cover, with TH soil on the left side and H, HO and BL on the right side (

Figure 7). Collemobla density, richness, Shannon and QBS-c indices, soil pH, ANU_TUL, BRA_PAR, HEM_THE abundances were positively correlated to the first axis; whereas, Corg content, basal respiration, URE activity, LEP_LIG, SMI_VIR, XEN_ACA abundances were negatively correlated to it (

Figure 7). The PERMANOVA analysis highlighted that soil under TH was significantly different (P < 0.01) from the soil under the other vegetation covers.

4. Discussion

The results revealed that different vegetation covers significantly influenced soil abiotic and biotic characteristics, with the two invasive species displaying distinct patterns in their effects. Specifically, soil under tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) appeared to positively impact soil biotic characteristics, showing marked differences compared to soils under native vegetation (holm oak and herbaceous covers). In contrast, black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) seemed to negatively affect soil biotic characteristics, exhibiting fewer differences from native vegetation, as confirmed by PERMANOVA analysis. The contrasting impacts of the two invasive species, disagreed with the first hypothesis and appear to stem primarily from differences in organic matter quality and nutrient utilization efficiency, consistent with findings by [

43]. These factors, in turn, differently influenced soil organism biomass and activities, disagreeing with the second hypothesis. However, the effects of invasive species on soil properties may change over time or with the age of the plants, as noted by Strayer et al. [

44]. This temporal aspect may partly explain the observed differences, given that black locust was introduced much earlier (1970) as part of afforestation programs [

45], whereas tree of heaven arrived spontaneously at a later date.

In soils invaded by tree of heaven, a significant increase in soil pH and a reduction in organic carbon (C

org) were observed. Similar changes in soil pH have been reported in various plant invasions [

46,

47,

48], although the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. One hypothesis is that the pH increase may result from the preferential uptake of nitrate by tree of heaven or by the elevated concentrations of base cations in the organic matter of tree of heaven [

49]. Invasive species are known to influence soil nutrient cycling by accelerating mineralization, altering nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) pools, and modifying C/N ratio [

46,

47]. In the case of tree of heaven, the reduction in C

org could be attributed to increased mineralization driven by the high quality of its organic matter [

50]. This highlights the role of invasive species in reshaping soil nutrient dynamics and ecosystem processes. This hypothesis is supported by the higher abundance of bacteria compared to fungi and the elevated dehydrogenase activity relative to other enzymes in soil under tree of heaven. Bacterial biomass and dehydrogenase activity are typically favored in soils rich in easily degradable organic matter [

51,

52], indicating intensified oxidative processes associated with organic matter degradation. The high decomposability of organic matter and abundant bacterial biomass in tree of heaven soil likely contributed to the observed increases in microarthropod and Collembola abundance and richness. The impact of invasive species on soil faunal communities varies widely. While some studies report negative effects on soil-dwelling arthropods [

53,

54], others describe positive impacts [

55,

56]. This variability suggests that the influence of invasive species is highly context-dependent. In the case of tree of heaven, the increase in microarthropod and Collembola abundance may be explained by the quality of its litter and organic matter, which provides diverse microclimatic niches and additional food resources [

57]. Tree of heaven soil also demonstrated high ecological quality, as indicated by elevated QBS-ar and QBS-c values, and the presence of hemi-edaphic Collembola, similar to those found in soil under holm oak. Holm oak soils are known for offering stable conditions for soil microarthropods [

24]. Despite invasive species often being associated with dynamic and disturbed environments [

58], the high QBS values in tree of heaven soil suggest it can support a stable environment that hosts organisms sensitive to disturbances [

59,

60]. However, the Collembola species composition differed markedly between soils under tree of heaven and holm oak. Holm oak soil supported higher species richness and a more diverse Collembola community, whereas tree of heaven soil harbored only six Collembola species. This limited diversity may be due to allelopathic compounds released by tree of heaven [

61,

62], which can exclude sensitive species while favoring tolerant ones. These findings highlight the critical role of indigenous species, which have co-evolved with the soil ecosystem over time, in maintaining and enhancing soil biodiversity and ecological functioning. Conversely, invasive species like tree of heaven, while capable of creating stable conditions for certain microarthropods, may ultimately reduce biodiversity by selectively favoring a narrower range of species.

The impacts of black locust on soil abiotic and biotic characteristics were notably distinct from those of tree of heaven. Except for urease activity, black locust was associated with lower microbial biomass and activity compared to soils under tree of heaven, with its soil characteristics falling intermediate between those under holm oak and herbaceous vegetation. While nutrient levels in soil under black locust were comparable to those under holm oak, microbial biomass and activities were significantly lower in black locust soil. This reduced microbial activity could be attributed to the presence of recalcitrant organic matter and nitrogen compounds in black locust soil, as previously observed [

48,

63]. However, recalcitrant organic matter compounds are also found in holm oak soils [

64], suggesting an additional factor—possibly the release of polyphenols by black locust. Polyphenols are known to form stable complexes with proteins, rendering them resistant to decomposition and partially inhibiting microbial activity [

65,

66]. Interestingly, urease activity in black locust soils was comparable to that in holm oak soil. This can be explained by black locust’s nitrogen-fixing ability and low nitrogen use efficiency [

67], which increased soil nitrogen content and promote urease activity. The presence of black locust also appeared to negatively influence the microarthropod and Collembola communities, consistent with findings by Lazzaro et al. [

68]. Changes in soil conditions and vegetation composition under black locust likely contributed to reduced microarthropod abundance and richness. Moreover, substances released during the decomposition of black locust leaves have been shown to exhibit allelopathic properties [

69], which could further limit microarthropod diversity. Despite the low abundance and richness of Collembola, soils under black locust showed a high abundance of eu-edaphic Collembola—specialists living within the soil, feeding on plant material, detritus, fungi, and bacteria [

70]. These organisms are known for their sensitivity to soil conditions, and their presence aligns with previous studies [

55,

71], which suggest that eu-edaphic organisms can thrive under invasive species, possibly as a refuge from unfavorable surface conditions. Despite the distinct impacts of black locust and tree of heaven on soil characteristics, the composition of Collembola species was surprisingly similar in both soils. The dominant species included A. tullbergi, B. parvula, H. thermophila, and P. armata. This similarity may reflect the selection of Collembola species tolerant to the secondary metabolites and allelopathic compounds released by both invasive species.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant influence of vegetation cover on soil abiotic and biotic characteristics, emphasizing the contrasting impacts of two invasive species, tree of heaven and black locust. In particular, tree of heaven positively influenced soil biotic characteristics, fostering microbial activity and microarthropod diversity. Conversely, black locust exhibited negative impacts on soil microbial communities and faunal abundance. These differences are likely driven by variations in organic matter quality and nutrient utilization efficiency. Despite the distinct effects of the two invasive species on soil characteristics, their similar Collembola species compositions suggest a convergent selection of taxa tolerant to their respective secondary metabolites and allelopathic substances.

Restoring ecosystems affected by invasive plants requires understanding the full scope of their impacts, both above and below ground. As the impacts of invasive species on soil properties may evolve over time, long-term studies are needed to assess how plant age and temporal changes affect soil ecosystems. In addition, expanding research, including other invasive species will provide broader insights into the mechanisms driving soil ecosystem changes and aid in developing more comprehensive management plans. Further investigations into the biochemical pathways and ecological impacts of allelopathic compounds will deepen our understanding of their influence on soil microbial and faunal dynamics. By integrating these findings into conservation and management practices, it could be possible to better mitigate the impacts of invasive species, preserve soil biodiversity, and maintain ecosystem functions in affected habitats.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: List reporting species or genus name, name code and the mean value (±s.e.) of the total abundance of each species identified in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S., M.Z., G.M.; methodology, G.S., V.M., G.D.N., M.To., M.T., M.Z.; software, G.S., V.M.; validation, M.Z., G.M., G.S., V.M., G.D.N., M. To., M.T., R.B., L.S.; formal analysis, G.S., V.M., G.D.N., M.To., M.Z.; investigation, L.S., M.Z.; resources, G.M., R.B.; data curation, L.S., M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S., M.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.M.; visualization, M.Z., G.M., G.S., V.M., G.D.N., M. To., M.T., R.B., L.S.; supervision, L.S., G.M.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M., R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“The research was funded by the collaboration of the Biology Department of University Federico II of Naples and the Vesuvius National Park within the “Azione di Sistema—Impatto antropico da pressione turistica nelle aree protette: interferenze su territorio e biodiversità” funded by “Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare”, Direttiva Conservazione della Biodiversità”.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundel, P.W. California chaparral and its global significance. Valuing chaparral: Ecological, socio-economic, and management perspectives, 2018, 1-27.

- Fried, G.; Laitung, B.; Pierre, C.; Chagué, N.; Panetta, F.D. Impact of invasive plants in Mediterranean habitats: disentangling the effects of characteristics of invaders and recipient communities. Biological Invasions, 2014, 16, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Cooper, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Orgiazzi, A.; Domínguez, A.; Dias Turetta, A.P.; Tapia Torres, Y. Threats to soil biodiversity—Global and regional trends. 2020.

- Rai, P.K.; Singh, J.S. Invasive alien plant species: Their impact on environment, ecosystem services, and human health. Ecol. Indicat. 2020, 111, 106020. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Singh, R. Key management issues of forest-invasive species in India. Indian J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 9, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maron, J.L.; Vilà, M. When do herbivores affect plant invasion? Evidence for the natural enemies and biotic resistance hypotheses. Oikos 2001, 95, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, C.P.; Brahma, B.C. A ray of hope against Parthenium in Rajaji National Park? Indian Forester 2001, 127, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R.B.; Banner, J.L.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Pockman, W.T.; Wall, D.H. Ecosystem carbon loss with woody plant invasion of grasslands. Nature 2002, 418, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà, M.; Espinar, J.L.; Hejda, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Jarošík, V.; Maron, J.L.; Pyšek, P. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: A meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities, and ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D.; Vitousek, P.M. Rapid nutrient cycling in leaf litter from invasive plants in Hawai’i. Oecologia 2004, 141, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenhamer, J.D.; Callaway, R.M. Direct and indirect effects of invasive plants on soil chemistry and ecosystem function. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeld, J.G.; Scott, N.A. Invasive species and the soil: Effects on organisms and ecosystem processes. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz, A.M.; Stanek, M.; Nobis, M.; Zubek, S. Species-specific effects of plant invasions on activity, biomass, and composition of soil microbial communities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.V.; Belnap, J.; D’Antonio, C.; Firestone, M.K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal assemblages in native plant roots change in the presence of invasive exotic grasses. Plant Soil 2006, 281, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, G.; Xue, S. A global meta-analysis of the impacts of exotic plant species invasion on plant diversity and soil properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Tsang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Sun, Y. Plant litter composition selects different soil microbial structures and in turn drives different litter decomposition patterns and soil carbon sequestration capability. Geoderma 2018, 319, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Putten, W.H.; Bardgett, R.D.; Bever, J.D.; Bezemer, T.M.; Casper, B.B.; Fukami, T.; Wardle, D.A. Plant–soil feedbacks: The past, the present, and future challenges. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, L.; Bolger, T. Soil microarthropod contribution to forest ecosystem processes: The importance of observational scale. Plant Soil 1998, 205, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, G.; Okafor, B.N.; Visconti, D. Soil microarthropods and nutrient cycling. Environ. Clim. Plant Veget. Growth 2020, 453–472. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggini, L.; Rusterholz, H.-P.; Baur, B. The invasive plant Impatiens glandulifera affects soil fungal diversity and the bacterial community in forests. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 124, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Rutherford, S.; Saif Ullah, M.; Ullah, I.; Javed, Q.; Rasool, G.; Du, D. Plant–soil feedback during biological invasions: Effect of litter decomposition from an invasive plant (Sphagneticola trilobata) on its native congener (S. calendulacea). J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperato, M.; Adamo, P.; Naimo, D.; Arienzo, M.; Stanzione, D.; Violante, P. Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metals in Urban Soils of Naples City (Italy). Environ. Pollut., 2003, 124, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santorufo, L.; Memoli, V.; Zizolfi, M.; Santini, G.; Di Natale, G.; Trifuoggi, M.; Barile, R.; De Marco, A.; Maisto, G. Microarthropod Responses to Fire: Vegetation Cover Modulates Impacts on Collembola and Acari Assemblages in Mediterranean Area. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.; Landi, L.; Pietramellara, G.; Renella, G. Microbial diversity and soil functions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasier, F.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.T.; Tomat, E.; Pietramellara, G. A simplified, rapid, low-cost, and versatile DNA-based assessment of soil microbial biomass. Ecol. Indicat. 2014, 45, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyzer, G.; De Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, E.J.; Hantula, J. Direct analysis of wood-inhabiting fungi using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of amplified ribosomal DNA. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.D.; Chapman, S.J.; Cameron, C.M.; Davidson, M.S.; Potts, J.M. A rapid microtiter plate method to measure carbon dioxide evolved from carbon substrate amendments so as to determine the physiological profiles of soil microbial communities by using whole soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, G.; Duncan, H. Development of a sensitive and rapid method for the measurement of total microbial activity using fluorescein diacetate (FDA) in a range of soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, K.; Wang, Z.; Lu, G.; He, Y.; He, W. Differences in the response of soil dehydrogenase activity to Cd contamination are determined by the different substrates used for its determination. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Soil enzymes. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties; 1983; Volume 9, pp. 903–947.

- Kendeler, E.; Gerber, H. Short-term assay of soil urease activity using colorimetric determination of ammonium. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1988, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alef, K.; Nannipieri, P. Enzyme Activities. In Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 311–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bretfeld, G. Synopses on Paleartic Collembolan. In Symphypleona; Dunger, W., Ed.; Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde: Görlitz, Germany, 1999; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Potapow, M. Synopses on Paleartic Collembolan. In Isotomidae; Dunger, W., Ed.; Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde: Görlitz, Germany, 2001; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud, J.M.; Schulz, Y.J.; da Gama Assalino, M.M. Synopses on Paleartic Collembolan. In Hypogastruridae; Dunger, W., Ed.; Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde: Görlitz, Germany, 2004; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fjellberg, A. The Collembola of Fennoscandia and Denmark; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin, S.P. A Key to the Collembola (Springtails) of Britain and Ireland; AIDGAP, Ed.; London, UK, 2007.

- Gisin, H. Ökologie und Lebensgemeinschaften der Collembolen im Schweizerischen Exkursionsgebiet Basels. Rev. Suisse Zool. 1943, 50, 131–224. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; Wagner, H. Vegan: Community ecology package, R Package, Version 2022.

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.B. The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Villar, S.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S.; Lorenzo, P.; Alonso, A.; Pérez-Corona, E.; Castro-Díez, P. Impacts of the Alien Trees Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle and Robinia pseudoacacia L. on Soil Nutrients and Microbial Communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 96, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Eviner, V.T.; Jeschke, J.M.; Pace, M.L. Understanding the Long-Term Effects of Species Invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fusco, N. Aspetti Forestali del Somma-Vesuvio. In Elementi di Biodiversità del Vesuvio; Picariello, O., Di Fusco, N., Fraissinet, M., Eds.; Ente Parco Nazionale del Vesuvio: Napoli, Italy, 2000; [In Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, M.; Tessier, M.; Suehs, C.M.; Brundu, G.; Carta, L.; Galanidis, A.; Lambdon, P.; Manca, M.; Médail, F.; Moragues, E.; Traveset, A.; Roumbis, A.Y.; Hulme, P.E. Local and Regional Assessment of the Impacts of Plant Invaders on Vegetation Structure and Soil Properties of Mediterranean Islands. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Aparicio, L.; Canham, C.D. Neighborhood Models of the Effects of Invasive Tree Species on Ecosystem Processes. Ecol. Monogr. 2008, 78, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Díez, P.; González-Muñoz, N.; Alonso, A.; Gallardo, A.; Poorter, L. Effects of Exotic Invasive Trees on Nitrogen Cycling: A Case Study in Central Spain. Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 1973–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeld, J.G. Effects of Exotic Plant Invasions on Soil Nutrient Cycling Processes. Ecosystems 2003, 6, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Villar, S.; Alonso, Á.; Vázquez de Aldana, B.R.; Pérez-Corona, E.; Castro-Díez, P. Decomposition and Biological Colonization of Native and Exotic Leaf Litter in a Central Spain Stream. Limnetica 2015, 34, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.A.; Crawford, J.W.; Field, D.J.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Zimmermann, M. The Knowns, Known Unknowns, and Unknowns of Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorufo, L.; Panico, S.C.; Zarrelli, A.; De Marco, A.; Santini, G.; Memoli, V.; Maisto, G. Examining Litter and Soil Characteristics Impact on Decomposer Communities, Detritivores, and Carbon Accumulation in the Mediterranean Area. Plant Soil 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, B.; Tatsumi, S.; Seibold, S.; Cadotte, M.W.; MacIvor, J.S. Urbanization and Plant Invasion Alter the Structure of Litter Microarthropod Communities. J. Anim. Ecol. 2020, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, T.; Forey, E.; Chauvat, M. Alien Invasive Plant Effect on Soil Fauna Is Habitat Dependent. Diversity 2022, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, A.R.; Cord, E.E.; Fulbright, T.E.; Schuster, G.L. Effects of Invasive Plants on Arthropods. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1532–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, W.A.M.; Molleman, J.; Franken, O.; Lammers, M.; Berg, M.P.; Behm, J.E.; Helmus, M.R.; Ellers, J. Disentangling the Effects of Plant Species Invasion and Urban Development on Arthropod Community Composition. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3294–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, M.; Kleijn, D.; Jogan, N. Species groups occupying different trophic levels respond differently to the invasion of semi-natural vegetation by Solidago canadensis. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmaier, M.; Lapin, K. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Invasive Alien Plants on Forest Regeneration in European Temperate Forests. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 524969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantoni, C.; Pellegrini, M.; Dapporto, L.; Del Gallo, M.M.; Pace, L.; Silveri, D.; Fattorini, S. Comparison of Soil Biology Quality in Organically and Conventionally Managed Agro-Ecosystems Using Microarthropods. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorufo, L.; Memoli, V.; Santini, G.; Di Natale, G.; Trifuoggi, M.; Barile, R.; Maisto, G. Responses of Soil Microarthropods to Soil Metal Fractions under Different Mediterranean Vegetation Covers. Catena 2023, 232, 107438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albouchi, F.; Hassen, I.; Casabianca, H.; Hosni, K. Phytochemicals, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and phytotoxic activities of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle leaves. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 87, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladonja, B.; Sušek, M.; Guillermic, J. Review on invasive tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle): Conflicting values, assessment of its ecosystem services, and potential biological threat. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1009–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Díez, P.; Fierro- Brunnenmeister, N.; González-Muñoz, N.; Gallardo, A. Effects of exotic and native tree leaf litter on soil properties of two contrasting sites in the Iberian Peninsula. Plant Soil 2012, 350, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panico, S.P.; Ceccherini, M.T.; Memoli, V.; Maisto, G.; Pietramellara, G.; Barile, R.; De Marco, A. Effects of different vegetation types on burnt soil properties and microbial communities. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, A.; Esposito, F.; Berg, B.; Zarrelli, A.; Virzo De Santo, A. Litter inhibitory effects on soil microbial biomass, activity, and catabolic diversity in two paired stands of Robinia pseudoacacia L. and Pinus nigra Arn. Forests 2018, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelac, M.; Sladonja, B.; Šola, I.; Dudaš, S.; Bilić, J.; Famuyide, I.M.; Poljuha, D. Invasive alien species as a potential source of phytopharmaceuticals: Phenolic composition and antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of Robinia pseudoacacia L. leaf and flower extracts. Plants 2023, 12, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Muñoz, N.; Castro-Díez, P.; Parker, I.M. Differences in nitrogen use strategies between native and exotic tree species: Predicting impacts on invaded ecosystems. Plant Soil 2013, 363, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, L.; Mazza, G.; d'Errico, G.; Fabiani, A.; Giuliani, C.; Inghilesi, A.F.; Foggi, B. How ecosystems change following invasion by Robinia pseudoacacia: Insights from soil chemical properties and soil microbial, nematode, microarthropod, and plant communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, H.; Iqbal, Z.; Hiradate, S.; Fujii, Y. Allelopathic potential of Robinia pseudoacacia L. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, R.; Ferrè, C.; Cardarelli, E.; Montagnani, C.; Bogliani, G.; Citterio, S.; Comolli, R. Comparing negative impacts of Prunus serotina, Quercus rubra, and Robinia pseudoacacia on native forest ecosystems. Forests 2019, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Neira, C.; Grosholz, E.D. Invasive cordgrass modifies wetland trophic function. Ecology 2006, 87, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Map of the sites collected under herbaceous vegetation (H, light grey), holm oak (HO, light green), black locust (BL, blue) and tree of heaven (TH, violet) inside Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 1.

Map of the sites collected under herbaceous vegetation (H, light grey), holm oak (HO, light green), black locust (BL, blue) and tree of heaven (TH, violet) inside Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 2.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of DNA yield (ng g-1), Eubacterial abundance (ng g-1) and Fungal abundance (ng g-1) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 2.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of DNA yield (ng g-1), Eubacterial abundance (ng g-1) and Fungal abundance (ng g-1) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 3.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of soil Basal respiration (mg CO2 g-1 d.w. h-1), Hydrolase (HA) activity (mmol FDA min-1 g-1 d.w.), Dehydrogenase (DHA) activity (mmol TFF min-1 g-1 d.w.), Urease (URE) activity (mmol NH4+ min-1 g-1 d.w.) and β-glucosidase (β-glu) activity (mmol PNP min-1 g-1 d.w.) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 3.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of soil Basal respiration (mg CO2 g-1 d.w. h-1), Hydrolase (HA) activity (mmol FDA min-1 g-1 d.w.), Dehydrogenase (DHA) activity (mmol TFF min-1 g-1 d.w.), Urease (URE) activity (mmol NH4+ min-1 g-1 d.w.) and β-glucosidase (β-glu) activity (mmol PNP min-1 g-1 d.w.) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 4.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of soil Collembola density (n. Collembola m-2), Collembola richness (n. of species or genus), Shannon index, QBS-c index calculated in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 4.

Boxplots reporting median (black dash), minimum and maximum of soil Collembola density (n. Collembola m-2), Collembola richness (n. of species or genus), Shannon index, QBS-c index calculated in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Figure 5.

Relative abudnance (%) of Collembola species or genus (

Table S1 for the whole name of species or genus) identified in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 5.

Relative abudnance (%) of Collembola species or genus (

Table S1 for the whole name of species or genus) identified in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 6.

Relative abudnance (%) of Collembola eco-morphological forms: eu-edaphic (brown), hemi-edaphic (orange) and epi-edaphic (green) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 6.

Relative abudnance (%) of Collembola eco-morphological forms: eu-edaphic (brown), hemi-edaphic (orange) and epi-edaphic (green) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park.

Figure 7.

Graphical display of the first two axes of the Principal Component Analysis performed on all the soil abiotic and biotic characteristics measured in soil under the different vegetation covers (H: herbaceous, HO holm oak, BL: black locust, TH: tree of heaven).

Figure 7.

Graphical display of the first two axes of the Principal Component Analysis performed on all the soil abiotic and biotic characteristics measured in soil under the different vegetation covers (H: herbaceous, HO holm oak, BL: black locust, TH: tree of heaven).

Table 1.

Mean values (± s.e.) of the pH, water content (WC % d.w.), total carbon (C % d.w.) and nitrogen (N % d.w.) content, organic carbon content (Corg % d.w.) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Table 1.

Mean values (± s.e.) of the pH, water content (WC % d.w.), total carbon (C % d.w.) and nitrogen (N % d.w.) content, organic carbon content (Corg % d.w.) measured in the soils collected under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

| Vegetations |

pH |

WC

(% d.w.) |

C

(% d.w.) |

N

(% d.w.) |

Corg

(% d.w.) |

| H |

6.41 b (±0.01) |

13.5 b

(±0.21) |

3.43 b (±0.53) |

0.60 a (±0.06) |

1.68 ab (±0.35) |

| HO |

6.33 b (±0.02) |

29.5 a

(±0.40) |

4.00 a

(±0.34) |

0.71 a (±0.10) |

2.06 a (±0.41) |

| BL |

6.50 b

(±0.04) |

12.9 b

(±0.20) |

3.26 b (±0.44) |

0.70 a (±0.10) |

1.50 ab (±0.31) |

| TH |

6.95 a (±0.03) |

10.6 b

(± 0.40) |

3.92 a (±0.42) |

0.62 a (±0.06) |

1.21 b (±0.40) |

Table 2.

Mean values (± s.e.) of density (expressed as n° of organisms m−2), taxa richness (expressed as n° of taxa), Shannon (H) and QBS-ar indices calculated for microarthropod community collected in the soils under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

Table 2.

Mean values (± s.e.) of density (expressed as n° of organisms m−2), taxa richness (expressed as n° of taxa), Shannon (H) and QBS-ar indices calculated for microarthropod community collected in the soils under four vegetation covers: herbaceous (H), holm oak (HO), black locust (BL) and tree of heaven (TH) at the Vesuvius National Park. Small letters indicate significant differences (at least, P < 0.05) among the vegetation covers.

| Vegetations |

Density |

Richness |

Shannon index |

QBS-ar |

| H |

2111 b (±502) |

8 ab

(±0.20) |

0.73 b (±0.21) |

37.42 b (±9.45) |

| HO |

3991 b (±535) |

8 ab

(±0.28) |

0.99 a

(±0.10) |

57.83 a (±3.74) |

| BL |

2661 b

(±303) |

6 b

(±0.22) |

0.79 b (±0.14) |

41.44 b (±5.60) |

| TH |

8945 a (±495) |

12 a

(± 0.21) |

1.41 a (±0.11) |

69.33 a (±10.22) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).