1. Introduction

Many species of buckwheat are found worldwide; however, only two are recognized for their agricultural and nutritional significance [

1]. These two species, Common buckwheat (

Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) and Tartary buckwheat (

Fagopyrum tataricum L. Gaertn) are widely utilized as raw material for food production. These grains are renowned for their rich nutritional profile, containing low digestible polysaccharides such as dietary fiber. Additionally, buckwheat grains provide proteins with well-balanced amino acids, lipids, essential micronutrients like minerals and vitamins, and polyphenolic compounds including flavonoids and phenols with antioxidative properties [

1,

2,

3].

The major components of dietary fiber are non-starch polysaccharides, and lignin, which are concentrated in the cell walls of starchy endosperm, aleurone, seed coats, and hulls [

4]. A considerable portion of buckwheat dietary fiber consists of soluble fraction. The soluble non-starch polysaccharides of buckwheat are rich in xylose, mannose, galactose, and glucuronic acid [

5]. Buckwheat grains and by-products are well known for their significant amounts of dietary fiber content, and antioxidative substances. The literature provides considerable evidence of an additive relationship between insoluble dietary fiber fractions, especially lignin, and total phenolic acid content[

6,

7,

8]. Lignin contains numerous phenolic hydroxyl groups and is an abundant source of polyphenolic compounds that can terminate oxygen reaction chains and neutralize harmful free radicals [

9]. Regarding pro-health food products, buckwheat can be used as an effective raw material for their production. Buckwheat and its products exhibit significant antioxidative activity, contributing to their prophylactic properties, which are crucial for human health [

1]. It contains catechins and phenolic acids including hydroxybenzoic, synigric, p-hydroxy-benzoic, vanillic, and p-coumaric acids, which exhibit strong antioxidant properties. These compounds are particularly concentrated in the bran and aleurone layer of buckwheat grains. However, the primary antioxidants in buckwheat are rutin, quercetin, and catechin [

1,

3,

10]. Notably, buckwheat bran and hulls demonstrate 2–7 times higher antioxidant activity compared to barley, triticale, and oats. The rutin content in buckwheat varies based on genotype, growing conditions, developmental phase, plant part, and year of harvest [

11]. Epidemiological studies have suggested that dietary flavonoids play a crucial role in the prevention of coronary heart diseases and cancers [

12]. Moreover, products rich in dietary fibre are associated with the prevention of affluent diseases such as overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colon cancer. As a result of these health benefits, the popularity of common buckwheat products has gained increasing attention in recent years, especially among health-conscious consumers.

It is worth noting that interest in Tartary buckwheat is increasing in some Asian and European countries. Tartary buckwheat deserves special attention because it is often underestimated and even treated by farmers as a weed, resulting in its cultivation being relatively uncommon. Compared to Common buckwheat, Tartary buckwheat contains a significant amount of rutin, quercetin, dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, and essential amino acids. Due to these attributes, Tartary buckwheat is recognized as a medicinal plant and has significant potential to be utilized in the production of dietary supplements. Furthermore, Tartary buckwheat may play an important role in reducing the risk of developing insulin resistance [

13,

14]. Its grains contain protein-derived peptides, with superior antioxidant capacity. Among these, four peptides (CR-8, LR-8, GK-10, and SR-12) have been identified for their ability to mitigate mild damage caused by reactive oxygen species [

15]. Moreover, polyphenols extracted from Tartary buckwheat husk through numerous methods have exhibited significant cytotoxicity against HepG2 cancer cells [

16].

Tartary buckwheat, compared to Common buckwheat, is characterized by higher yield potential (around 1.5 ton/ha), superior frost resistance, and the ability to grow at higher elevations [

1,

14]. Due to its low agrotechnical requirements and health-promoting properties, Tartary buckwheat is gaining increasing attention from researchers, food producers, and farmers. This provides hope for new possibilities in food technology and human nutrition, especially in the context of global climate change. Buckwheat flavonoids, as a secondary metabolite, play a significant role in regulating plant’s response to abiotic environmental factors. Consequently, many researchers are focusing on the stress adaptability of plants, aiming to understand the relationship between environmental stress adaptation and secondary metabolite production [

17]. Buckwheat tissues can be a rich source of high-quality flavonoids; however, their content varies throughout the plant development and is significantly influenced by soil quality [

18].

Both dietary fiber and flavonoids are important bioactive components that play a key role in protecting against chronic diseases and prolonging the shelf life of food products. Certain morphological parts of Tartary buckwheat, which are rich in these substances, can be utilized to create healthy food products, particularly in the context of climate change. Drought, a consequence of climate change, severely limits agricultural development, which leads to the reduction of crop yield and quality [

19,

20]. Buckwheat is considered as tolerant or even resistant to the adverse environment and abiotic stresses, including drought [

21]. The regulatory mechanism of Tartary buckwheat under drought stress is still under investigation [

22]. Therefore, this study aimed to reveal the changes in nutrient content across the morphological parts of the Tartary buckwheat plant in response to limited water supply.

3. Discussion

Experiments comparing the morphological parts of drought-stressed and non-stressed Tartary buckwheat plants revealed no significant differences in moisture content across all analyzed samples. However, other studies have reported that moisture content varies depending on the duration of drought stress treatments and the plant varieties used in the experiments. These studies highlighted that different plant varieties exhibited markedly distinct results under short- and long-term drought stress treatments [

23]. Therefore, the selection of more drought-resistant Tartary buckwheat plants for cultivation appears to be highly important. Similarly, a previous study investigated Amaranthus leaves under short, medium, and long drought stress treatments and observed a reduction in moisture content across all trials [

24].

Buckwheat grains are generally a good source of protein, with a well-balanced amino acid composition [

25]. Tartary buckwheat is typically characterized by a lower protein content compared to common buckwheat [

25,

26,

27]. In our study, the total protein content was highest in dehulled seed samples, ranging between 11% and 16.1%, which is comparable to data reported in the literature (11-18.9%) [

26,

27]. The drought-stressed treatment altered the concentration of total proteins in grain samples, as shown in previous studies [

25]. However, grains from well-watered plants exhibited higher protein concentrations. The second highest protein content was observed in the S and N husk samples, which contrasts with findings from other studies [

26]. The protein content of approximately 8.5% in the husk fraction can be attributed to the dehulling process conducted under laboratory conditions. It is likely that parts of the grain's outer layer, which is rich in protein, were crushed and transferred to the husk samples. No significant differences in protein levels were observed between the well-watered and drought-treated husk samples. Additionally, we identified slightly higher protein levels in leaves and stems compared to values reported by other studies. Yan et al. (2024) detected predominantly enzymatic proteins in the green parts of Tartary buckwheat during growth, which are involved in the physiological functions of the plant [

23]. Well-watered conditions led to an increase in the total protein content in leaves and stems. Other researchers have reported varying effects of well-watered and drought conditions on changes in soluble protein levels, attributed to differences in plant varieties and the duration of drought treatment. Prolonged stress occasionally causes a significant decrease in soluble protein content [

23]. A similar trend was observed in wheat plants treated with drought stress, as demonstrated in our study [

28,

29]. These studies reported a significant decrease in soluble proteins in the green parts of wheat. Additionally, drought stress at different stages of plant growth has been reported to impact the regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism [

30], which may explain the changes in protein content depending on water conditions.

Fagopyrum tataricum is not considered as an oilseed plant due to its relatively low lipid content. However, its fats are rich in tocopherols and phytosterols [

31]. The highest concentration of buckwheat lipids is typically found in its seeds and bran. In this experiment, variations in total lipid content were observed depending on the environmental treatment; however, these changes were significant only in the leaf samples. Lina et al. (2024) reported that water limitation during corn plant growth did not significantly affect the total lipid content in its green tissues after regeneration, which contrasts with the findings of our study [

32].

The morphological parts of Tartary buckwheat are a rich source of total dietary fiber, particularly its insoluble fraction [

6,

26,

33]. All of our samples were characterized by a high content of total dietary fiber, with the insoluble dietary fiber (IDF) fraction being the dominant component, while the soluble dietary fiber (SDF) fraction was the smallest. The order of TDF contents, from highest to lowest, is as follows: stems > leaves > husk > seeds. A previous study has reported lower fiber concentrations in the well-watered morphological parts of the plant, as determined using the chemical method outlined by Van Soest [

6]. There is limited information in the literature regarding the effect of drought treatment on TDF amounts and its distribution in the morphological parts of Tartary buckwheat. However, some studies have observed that drought stress did not alter the TDF content in wheat [

29]. In contrast, another study has found that drought treatment of the Amaranthus plant led to an increase in total dietary fiber content [

24]. Tartary buckwheat samples also contain the SDF fraction; however, the morphological parts of the plant are not considered rich sources of these compounds. The SDF fraction plays a vital role in enhancing gastrointestinal health, as it is linked to an increase in the microbiome and the production of various beneficial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids [

34]. To increase the SDF fraction at the expense of the IDF fraction, mechanical fragmentation is recommended [

35].

Tartary buckwheat is recognized as a medicinal plant, due to its high antioxidant profile, up to 10 times higher than that of other cereals and pseudo-cereals [

26]. As a result, leaves are commonly used in Western Asian countries to prepare Tartary buckwheat tea [

34]. Several studies have reported that drought treatment causes stress during the growth of buckwheat plants, which is ultimately linked to the expression of genes responsible for increasing protective factors [

23,

30]. There is also some evidence suggests that the cultivar and growing season influence the content of phenolic acids [

26]. The antioxidant potential of Tartary buckwheat is strongly associated with its phenolic compound content [

25]. Our results suggest that drought treatment decreased DPPH scavenging activity in the leaves and husks, although the leaves exhibited the highest total phenolic content. A similar trend for TPC was observed in both hull and leaves, contrary to findings from another study [

23]. However, no significant differences were noted for dehulled grains. Moreover, well-watered dehulled seeds and husks exhibited higher ferrous ion chelating activity, partially contradicting previously conducted studies. A comparison of TPC and phenolic profile estimated by HPLC-MS, revealed varied tendencies between drought and well-watered treatment samples, suggesting a lack of stress symptoms in the morphological parts of the treated plants. Drought treatment induces the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS), which regulate the state of the cell. The antioxidant system in plants is divided into two parts: enzymatic (catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and others), and non-enzymatic (phenolic compounds). During stress conditions, the detoxification of ROS and RNS is carried out by an antioxidant system, as some glycosides and phenolic substances act as ROS scavengers; as a result, the concentration of phenolic compounds and their activity were lower in drought treated samples [

36,

37]. It was notably observed that water deficit led to the decrease of most identified antioxidative compounds. Among these, phenolics such as rutin, quercetin, quercetin glucosides, and coumaric acid were found to be dominant. Both common and Tartary buckwheat are rich in these compounds. However, not all 57 compounds were identified in every sample, as their distribution varies during plant growth [

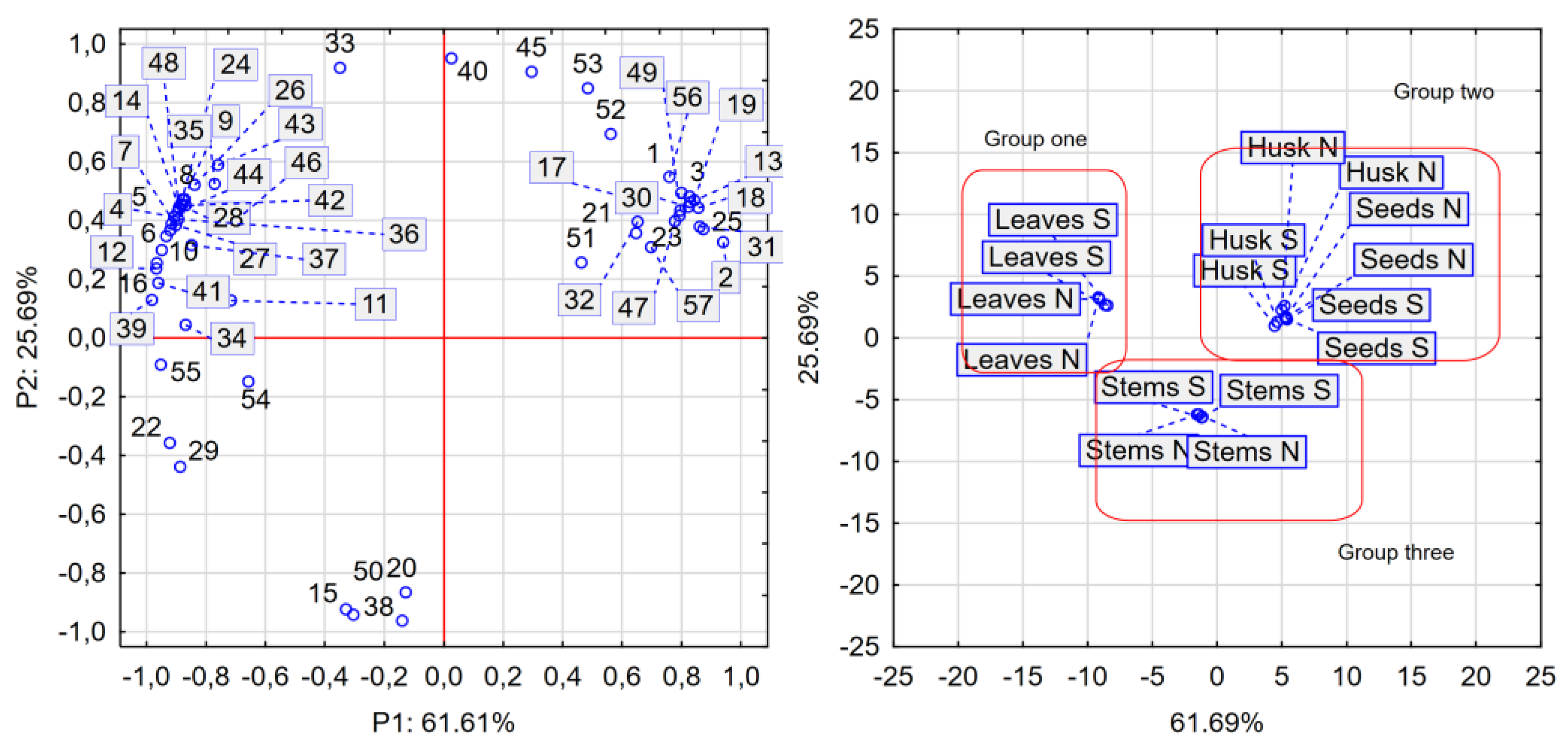

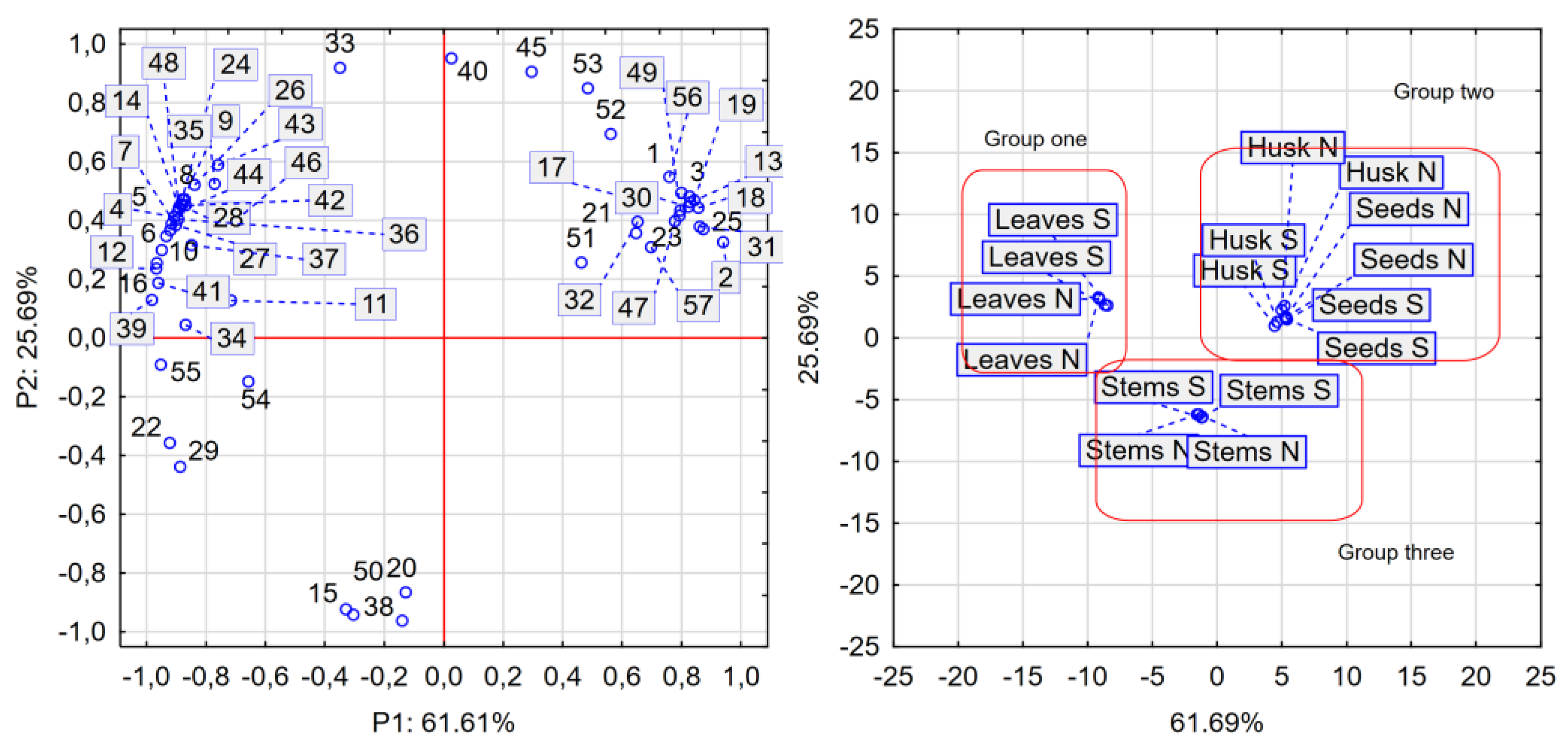

25]. Principal component analysis (Fig. 1) revealed that individual phenolic compounds grouped the samples into three clusters: leaves (group one), seeds and husks (group two), and stems (group three). Furthermore, no distinct group was generated by the drought-treated samples, providing strong evidence that Tartary buckwheat is a plant with good tolerance to water deficit. Plants respond to water-deficit conditions through a series of physiological, cellular, and molecular processes that enhance their stress tolerance [

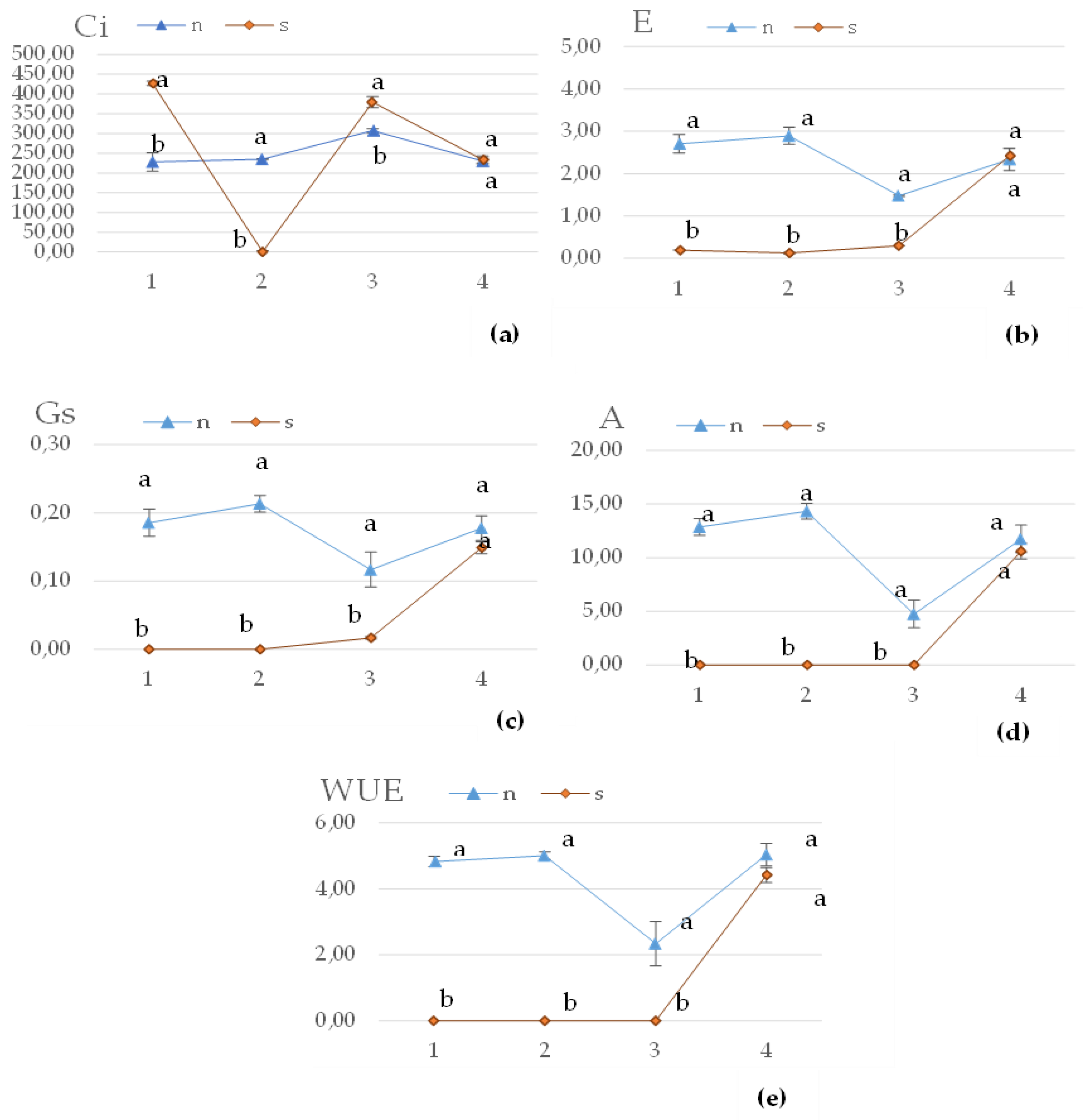

38]. Similar to our findings, some studies revealed that Tartary buckwheat exhibits physiological responses to drought stress including a reduction in photosynthesis, transpiration, stomatal conductance, and yield, while increase in intercellular CO2 concentration [

39]. Additionally, previous research showed that wheat genotypes with higher antioxidant activity increased intercellular CO

2 concentration, better water use efficiencies and improved net photosynthesis were better able to tolerate drought stress conditions [

40].

Tartary buckwheat, as a medicinal plant, is an excellent source of various phenolic compounds with high biological activity. In addition to its significant total dietary fiber content, particularly its insoluble fraction, it contains 57 distinct phenolic compounds that are distributed across different morphological parts of the plant. This composition contributes effectively to the antioxidative activity of all parts of the plant. Furthermore, drought stress did not cause negative effects on the plant's physiological development during its final growth stages. Therefore, Tartary buckwheat can be recommended as a drought-resistant plant, making it suitable for cultivation in the context of progressive climate changes. In this study, we identified the activity of phenolic compounds against oxygen and nitrogen reactive species, which effectively protected the plant during the final stage of growth. For this reason, to obtain higher amounts of phenolic compounds and greater antioxidant activity, we recommend harvesting the plant during the early stage of drought treatment.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material

Seeds of Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) were obtained from Breeding Station (Palikije, Poland). They were sown in 7 L polyethylene pots filled with soil classified as luvisol, a light clay sand grade, shallowly deposited on light clay that belongs to a good rye complex. The soil had a pH of 5.4, with an average content of 120.6 mg P₂O₅ per kg of soil (very high), 122.5 mg K₂O per kg of soil (high), and 0.59% organic matter. Five seeds were sown in each pot, and after germination, three uniformed plants were retained. The pot study was conducted in the didactic plant collection facility, belonging to the Department of Agronomy at the Poznan University of Life Sciences. Four weeks after seeds sowing, the plants were transferred to a phytotron (with a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 65 ± 5%, and a 16-hour photoperiod). Half of the experimental pots (120 plants) were maintained under control conditions with water supplied every 3 days, while the other 120 plants were subjected to water stress, with no water supply for 2 weeks during the 69-73 BBCH phase (Phenological development stages of plants). Soil moisture was measured to confirm well-watered conditions (15% water content, equating to 70% field capacity) or water stress conditions (<10% water content, approximately <40% field capacity) using a probe (ThetaProbe, Eijkelkamp Penetrologger SN, Giesbeek, The Netherlands). The experiment lasted 80 days. Samples of stalks, leaves, husks, and seeds were collected after harvesting and stored under chilled conditions (around 7 °C) for no longer than 6 months. All samples were ground using a knife mill (WŻ1, Sadkiewicz, Poland), ensuring that the size of each particle was no larger than 200 μm. A representative sample was taken in triplicate for each analysis.

4.2. Reagents

Caffeic acid (C0625-25G), chlorogenic acid (PHR2202-100MG), p-coumaric acid (C9008-1G), sinapic acid (D7927-5G), quercetin (Q4951-10G), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox, 238813-5G), and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, D9132-1G) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich company (Germany). Total dietary fiber enzymatic kit was obtained from Megazyme company (K-TDFR 05/12, Ireland). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, PA-03-4011-E#100G) was proved from Pol-Aura company (Poland). Methanol (67-56-1), diethyl ether (60-29-7), sulphuric acid VI (7664-93-9), sodium hydroxide (1310-73-2), and Kjeldahl Catalyst (85539, K₂SO₄, 23,10%; Na₂SO₄, 69,30%; CuSO₄, 1,80%; TiO₂, 2,80%) were purchased from VWR company (Poland).

4.3. Chemical Composition

Total nitrogen compounds were estimated using the ISO Method 20483:2013. The results were calculated as protein content with a conversion factor of 6.25. The enzymatic method AOAC 991.43 was used to estimate total dietary fiber (TDF) and its soluble (SDF) and insoluble (IDF) fractions. The AACC Method 30-10.01 was conducted to analyse total lipid content using the Soxtec System HT6 (Foss Tecator, Sweden).

4.4. Selected Phenolic Substances—HPLC-MS Chromatography

Reversed-phase (C18 column) electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (RP-UHPLC-ESI-MS) analysis was performed using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) coupled to a Bruker maXis impact ultrahigh resolution orthogonal quadrupole-time-of-flight accelerator (qTOF) equipped with an ESI source and operated in both positive- and negative-ion modes (Bruker Daltonik, Germany). many). The RP chromatographic separation was achieved with a Kinetex™ 1.7 µm C18 100 Å, LC column 100 × 2.1 mm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 30 °C according to [Biesaga and Pyrzyńska, 2013] using 8 mM formic acid as eluent A and acetonitrile as eluent B with flow 0.2 ml/min. Molecular ions: [M+H]+ and [M-H]- for phenolic compounds were extracted from full scan chromatograms (±0.005 m/z), and peak areas were integrated using TASQ 2.1 (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The limit of quantification (LOQ where S/N >15) was determined for caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, sinapic acid, quercetin, and it was no lower than 0.01 µg/mL [

41]. Calibration and quality control (QC) samples were prepared in water: methanol mixture (30:70 v/v) as surrogate matrix. The recovery of standards spiked into samples was above 95-106%. The coefficient of determination (R

2) for all calibration curves was higher than 0.99. The compounds present in each sample were identified based on retention time of standards, as well as molecular mass and structural information obtained from the MS detector during MS/MS experiments. Tandem mass spectrometric data were used for searching molecular structure identification using CSI (Compound Structure Identification): Finger ID (Friedrich Schiller University, Jena Germany), corporated in SIRIUS Software [

42]. Simultaneously the MoNA (MassBank of North America) tandem spectra were downloaded and used for the annotation of compounds in MetaboScape 4.0.4 (Bruker Daltonik, Germany) by a comparison of assigned MS/MS spectra with MoNA spectral database.

4.5. DPPH Analysis

A ground sample (10 g) was placed in an Erlenmeyer flask and incubated with 100 mL of distilled water for 24 hours at room temperature. The sample was then filtered and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The capacity of the sample extracts to scavenge the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was estimated according to the method of Sanchez-Moreno et al. [

43]. DPPH (1 mM, 0.25 mL) was dissolved in methanol, and then 0.025-0.15 mL of the water extract samples were added. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm after 30 minutes of incubation at room temperature in darkness. The results were expressed as mg Trolox per g of dry matter (d.m.) extract.

4.6. Ferrous Ions Chelating Activity

The results were estimated using the method described by Tang et al. [

44]. The assay involved the colorimetric measurements of the degree of color loss in iron (II) chloride (2 mM, 0.1 mL) complexes with ferrozine (5 mM, 0.2 mL) caused by the extracts, with values in the range 0.5-2 mL. The wavelength of measurement was 562 nm. The results were expressed as mg EDTA/g of dry matter extract.

4.7. Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC)

The Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (FCR) method was adopted to estimate the total amounts of phenolic substances in the sample extracts [

45]. The volume of sample (0.025-0.2 mL of water extract) was stirred with distilled water (final volumes of water extract with water were 10 mL) and 0.5 mL of the FCR. The investigated material was blended with 1 mL of saturated sodium carbonate solution. Then, the mixture was incubated 30 minutes at room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 750 nm (Specord 40). The results were presented in mg of gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry matter extract (mg of GAE/g of d.m. extract).

4.8. Physiological State of Plants

At the BBCH 73 phase parameters linked to the photosynthesis and water status of the plants were taken on the youngest expanded leaf of ten plants per condition in four replications. Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters: the maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), effective quantum yield of photosystem II (Yield) and electron transport rate (ETR), were measured using a portable modulated chlorophyll fluorometer (OS5p, Opti-Sciences, Inc., Hudson, NY, USA) with a PAR Clip that allows the measurement of PAR and leaf temperature, according to Sulewska et al. protocol settings [

46]. The net photosynthetic rate (A), leaf transpiration rate (E), the leaf stomatal conductance (Gs), and the intercellular CO

2 concentration (Ci) were quantified by using a portable photosynthesis system (LCpro-SD, ADC BioScientific Ltd., Hoddesdon, UK) with a narrow leaf chamber (area: 5.8 cm

2). The water use efficiency (WUE) was calculated as WUE=A/E. Measurements were taken on plants with a visible loss of turgor in the leaves 14 days after the abandonment of watering when the soil humidity of the drought-treated pots was at the level <10% by volume. In order to trace the regeneration of plants, they were irrigated again in the same way as at the beginning of the experiment. The regeneration of plants after undergoing drought stress was assessed after 6 days of irrigation (24 days from the start of measurements).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional plot representing the PCA: loading plot (left site), and score plot (right site). 1 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 2 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 3 - Vanillic acid glucoside, 4 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 5 - Neochlorogenic acid, 6 – Dihydroxybenzoate, 7 - Catechin glucoside, 8 - Catechin 3-O-rutinoside, 9 - Ferulic acid, 10 - Hydroxycinnamic acid, 11 - Chlorogenic acid, 12 - Catechin, 13 - Quercetin glycoside, 14 - Procyanidin B2/B4, 15 - Ethyl syringate, 16 - Sinapoyl hexoside, 17 - Coumaroylquinic acid, 18 - Epiafzelechin-catechin, 19 - Kaempferol glucoside, 20 - Apigenin glycoside, 21 - Coumaroylquinic acid, 22 - p-Coumaric acid, 23 - Hydroxycoumarin, 24 - Myricetin 3-glucoside, 25 - Afzelechin, 26 - Flavonoid glycoside, 27 - Chrysoeriol glucoside, 28 - Flavonoid glycoside, 29 - Ferulic acid, 30 - Quercetin 3-rhamninoside, 31 - Myricetin, 32 - Quercetin glycoside, 33 - Luteolin-glucoside, 34 - Epicatechin/catechin gallate, 35 - Quercetin 3-rutinoside, 36 - Procyanidin B, 37 - Quercetin hexoside, 38 - Sinapoyl aldehyde, 39 - Coumaric acids derivative, 40 - Kaempferol-3-rutinoside, 41 - Isorhamnetin glycoside, 42 - Quercetin glycoside, 43 - Quercetin glycoside, 44 - Phloretin glucoside, 45 - Quercetin glycoside, 46 - Emodin glycoside, 47 - Epicatechin hydroxybenzoate, 48 - Flavonoid glycoside (Luteolin glycoside), 49 - Flavonoid glycoside (Kaempferide 3-rhamnoside-7-(6''''-succinylglucoside)), 50 - Feruloyltyramine, 51 - Malvidin glucoside-ethyl-catechin, 52 - Flavone (Myricetin), 53 - Quercetin, 54 - Luteolin, 55 - Methylquercetin, 56 - Kampherol, 57 – Dimethylquercetin.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional plot representing the PCA: loading plot (left site), and score plot (right site). 1 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 2 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 3 - Vanillic acid glucoside, 4 - Dihydroxybenzoate hexoside, 5 - Neochlorogenic acid, 6 – Dihydroxybenzoate, 7 - Catechin glucoside, 8 - Catechin 3-O-rutinoside, 9 - Ferulic acid, 10 - Hydroxycinnamic acid, 11 - Chlorogenic acid, 12 - Catechin, 13 - Quercetin glycoside, 14 - Procyanidin B2/B4, 15 - Ethyl syringate, 16 - Sinapoyl hexoside, 17 - Coumaroylquinic acid, 18 - Epiafzelechin-catechin, 19 - Kaempferol glucoside, 20 - Apigenin glycoside, 21 - Coumaroylquinic acid, 22 - p-Coumaric acid, 23 - Hydroxycoumarin, 24 - Myricetin 3-glucoside, 25 - Afzelechin, 26 - Flavonoid glycoside, 27 - Chrysoeriol glucoside, 28 - Flavonoid glycoside, 29 - Ferulic acid, 30 - Quercetin 3-rhamninoside, 31 - Myricetin, 32 - Quercetin glycoside, 33 - Luteolin-glucoside, 34 - Epicatechin/catechin gallate, 35 - Quercetin 3-rutinoside, 36 - Procyanidin B, 37 - Quercetin hexoside, 38 - Sinapoyl aldehyde, 39 - Coumaric acids derivative, 40 - Kaempferol-3-rutinoside, 41 - Isorhamnetin glycoside, 42 - Quercetin glycoside, 43 - Quercetin glycoside, 44 - Phloretin glucoside, 45 - Quercetin glycoside, 46 - Emodin glycoside, 47 - Epicatechin hydroxybenzoate, 48 - Flavonoid glycoside (Luteolin glycoside), 49 - Flavonoid glycoside (Kaempferide 3-rhamnoside-7-(6''''-succinylglucoside)), 50 - Feruloyltyramine, 51 - Malvidin glucoside-ethyl-catechin, 52 - Flavone (Myricetin), 53 - Quercetin, 54 - Luteolin, 55 - Methylquercetin, 56 - Kampherol, 57 – Dimethylquercetin.

Figure 2.

Effect of water stress on (a) the intercellular CO2 concentration (µmol∙m−1) (Ci), (b) the transpiration rate (mmol∙m−2∙s−1) (E), (c) the leaf stomatal conductance (mol∙m−2∙s−1)(Gs), (d) the net photosynthesis rate (mmol∙m−2∙s−1) (A), (e) and the water use efficiency (WUE) of fresh plant F. tataricum; Water treatment: N-non-stressed, S-stressed ; 1, 2 - days of measurements after the occurrence of stress, 3, 4 – days of measurement after regeneration; the vertical bars show standard errors across treatment means; a-b different letters mean a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the two water treatments according to ANOVA test.

Figure 2.

Effect of water stress on (a) the intercellular CO2 concentration (µmol∙m−1) (Ci), (b) the transpiration rate (mmol∙m−2∙s−1) (E), (c) the leaf stomatal conductance (mol∙m−2∙s−1)(Gs), (d) the net photosynthesis rate (mmol∙m−2∙s−1) (A), (e) and the water use efficiency (WUE) of fresh plant F. tataricum; Water treatment: N-non-stressed, S-stressed ; 1, 2 - days of measurements after the occurrence of stress, 3, 4 – days of measurement after regeneration; the vertical bars show standard errors across treatment means; a-b different letters mean a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the two water treatments according to ANOVA test.

Table 1.

Dry matter, protein, lipid content, and the composition of total, soluble and insoluble dietary fibre composition in selected parts of buckwheat plant: leaves, stems seeds, and husk (g/100 g of dry powdered product).

Table 1.

Dry matter, protein, lipid content, and the composition of total, soluble and insoluble dietary fibre composition in selected parts of buckwheat plant: leaves, stems seeds, and husk (g/100 g of dry powdered product).

| |

DM |

Protein |

Lipids |

IDF |

SDF |

TDF |

| Leaves |

S |

91.3b

|

9.78c

|

1.74c

|

47.98d

|

0.42e

|

48.4d

|

| N |

91.18b

|

12.89b

|

2.44ab

|

48.71d

|

0.42e

|

49.13d

|

| Stems |

S |

93,01a

|

2.86f

|

0.47d

|

73.19a

|

3.46b

|

76.65a

|

| N |

93,43a

|

5.08e

|

0.57d

|

72.16a

|

4.04a

|

76.20a

|

| Seeds |

S |

89.62c

|

11.89b

|

2.15b

|

15.27e

|

0.09f

|

15.36e

|

| N |

88.91c

|

16.11a

|

2.58a

|

15.59e

|

0.03f

|

15.62e

|

| Husk |

S |

91.05b

|

8.23d

|

2.22ab

|

61.21b

|

2.34d

|

63.55b

|

| N |

90.84b

|

8.59d

|

2.23ab

|

52.16c

|

2.53c

|

54.69c

|

Table 2.

DPPH scavenging activity, ferrous ions chelating activity, and total content of phenolic compounds in selected parts of buckwheat plant: leaves, stems, seeds and husk.

Table 2.

DPPH scavenging activity, ferrous ions chelating activity, and total content of phenolic compounds in selected parts of buckwheat plant: leaves, stems, seeds and husk.

| |

DPPH* (mg/g d.m. of extract) |

Ferrous ions chelating activity** (mg/g d.m. of extract) |

TPC*** (mg/g of d.m. extract) |

Total phenolics (mg/100 g of d.m. product) |

| Leaves |

S |

208.03b

|

3.51fg

|

296.18a

|

266.33c

|

| N |

257.21a

|

2.17g

|

152.76b

|

309.32a

|

| Stems |

S |

27.45e

|

10.49e

|

58.40d

|

113.56g

|

| N |

28.31e

|

7.83ef

|

65.57c

|

126.64f

|

| Seeds |

S |

22.69f

|

57.89d

|

28.94f

|

233,54e

|

| N |

22.21f

|

81.22c

|

31.19e

|

246.24d

|

| Husk |

S |

43.59d

|

210.48b

|

43.3g

|

247,96d

|

| N |

53.21c

|

439.44a

|

43.65g

|

276.77b

|

Table 3.

The effect of water stress on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (non-nominated units) of F. tataricum fresh leaves.

Table 3.

The effect of water stress on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (non-nominated units) of F. tataricum fresh leaves.

| Water treatment |

During drought stress |

After regeneration |

| |

Non stressed |

Stressed |

Non stressed |

Stressed |

|

1Fv/Fm |

0.841a

|

0.823b

|

0.746a

|

0.775a

|

| ETR |

13.67b

|

43.40a

|

12.20a

|

10.64a

|

| Yield |

0.27a

|

0.30a

|

0.24a

|

0.21a

|