Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant growth and treatment

2.2. Physiological and biochemical analyses

2.2.1. Soil water potential

2.2.2. Leaf water potential

2.2.3. Measurements of shoot and root weights

2.2.4. Relative water content

2.2.5. Proline content

2.2.6. Hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde contents

2.2.7. Antioxidant enzyme activities

2.2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

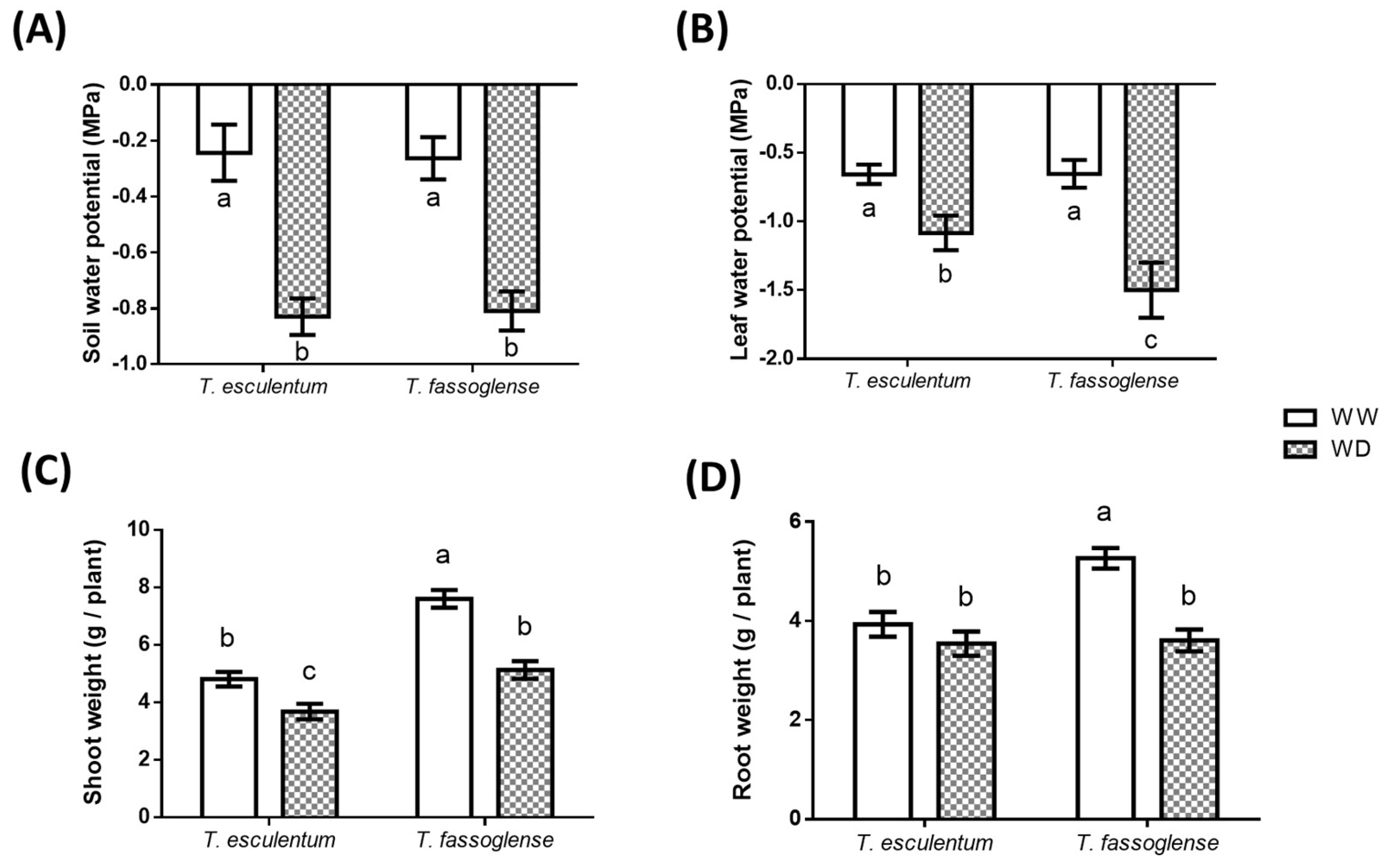

3.1. Plant water status and growth

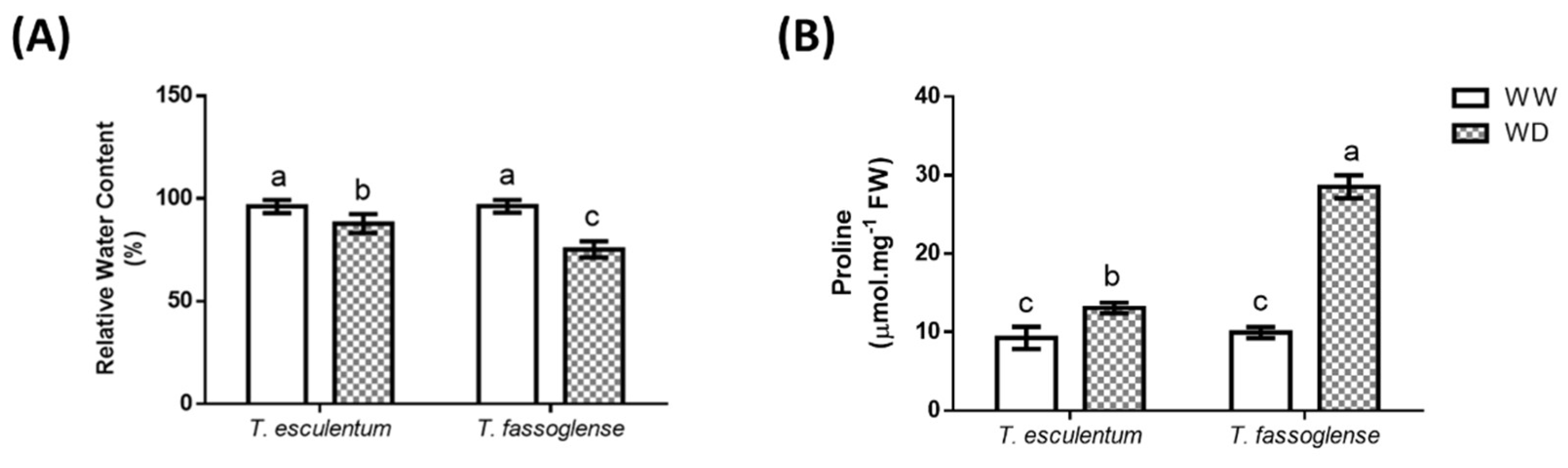

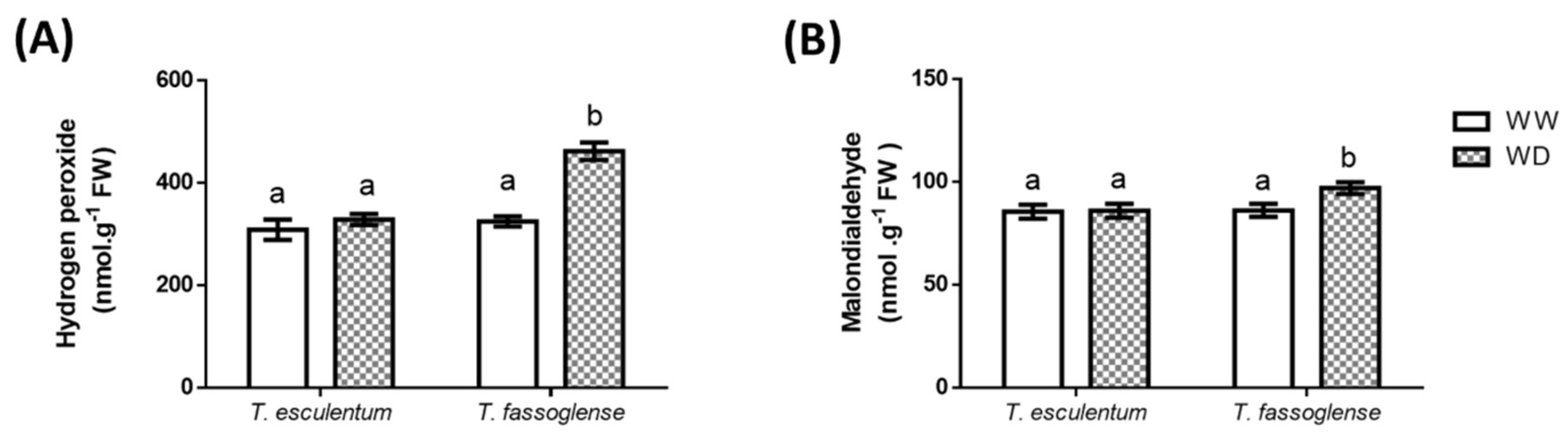

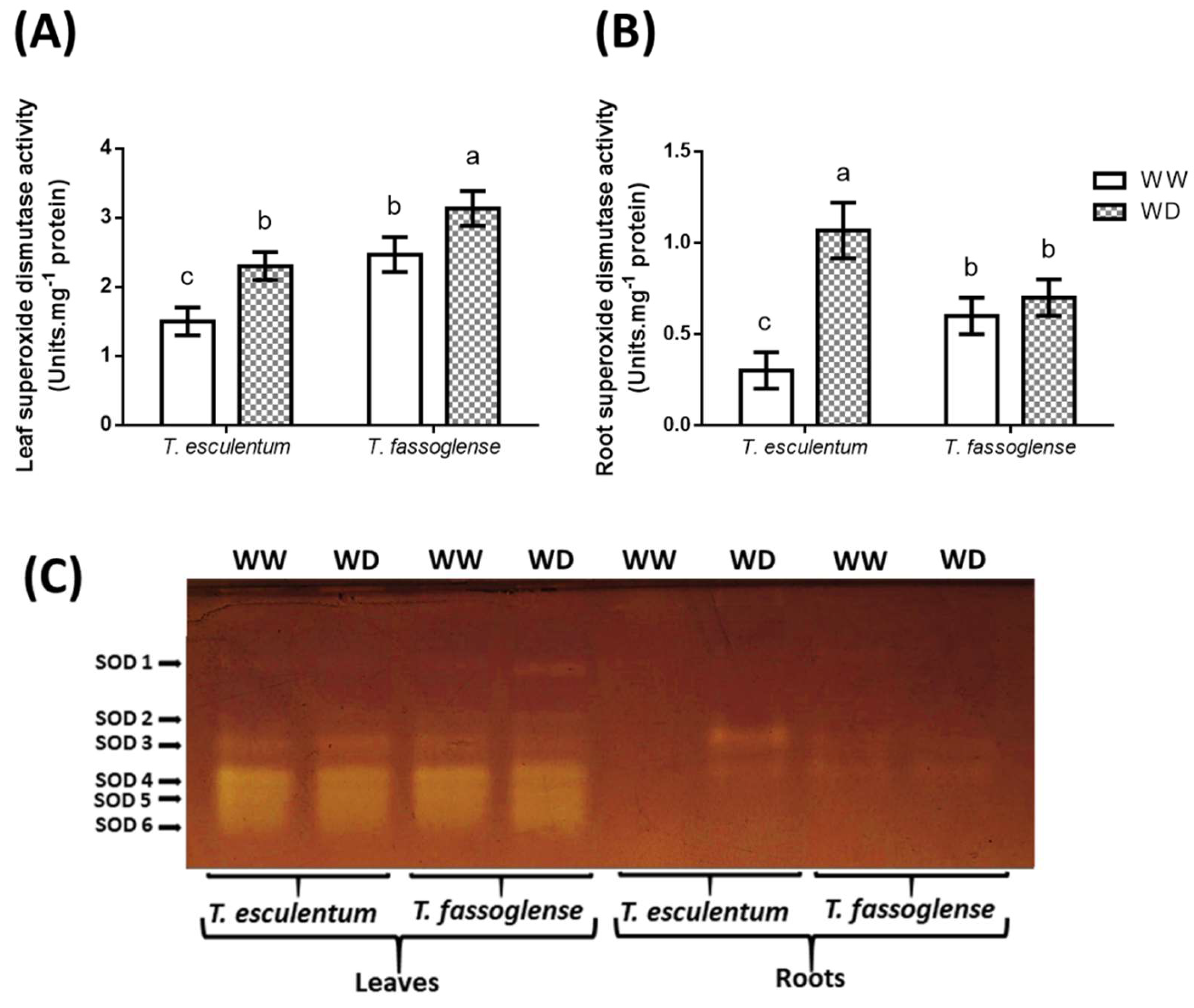

3.2. Oxidative stress and antioxidant responses

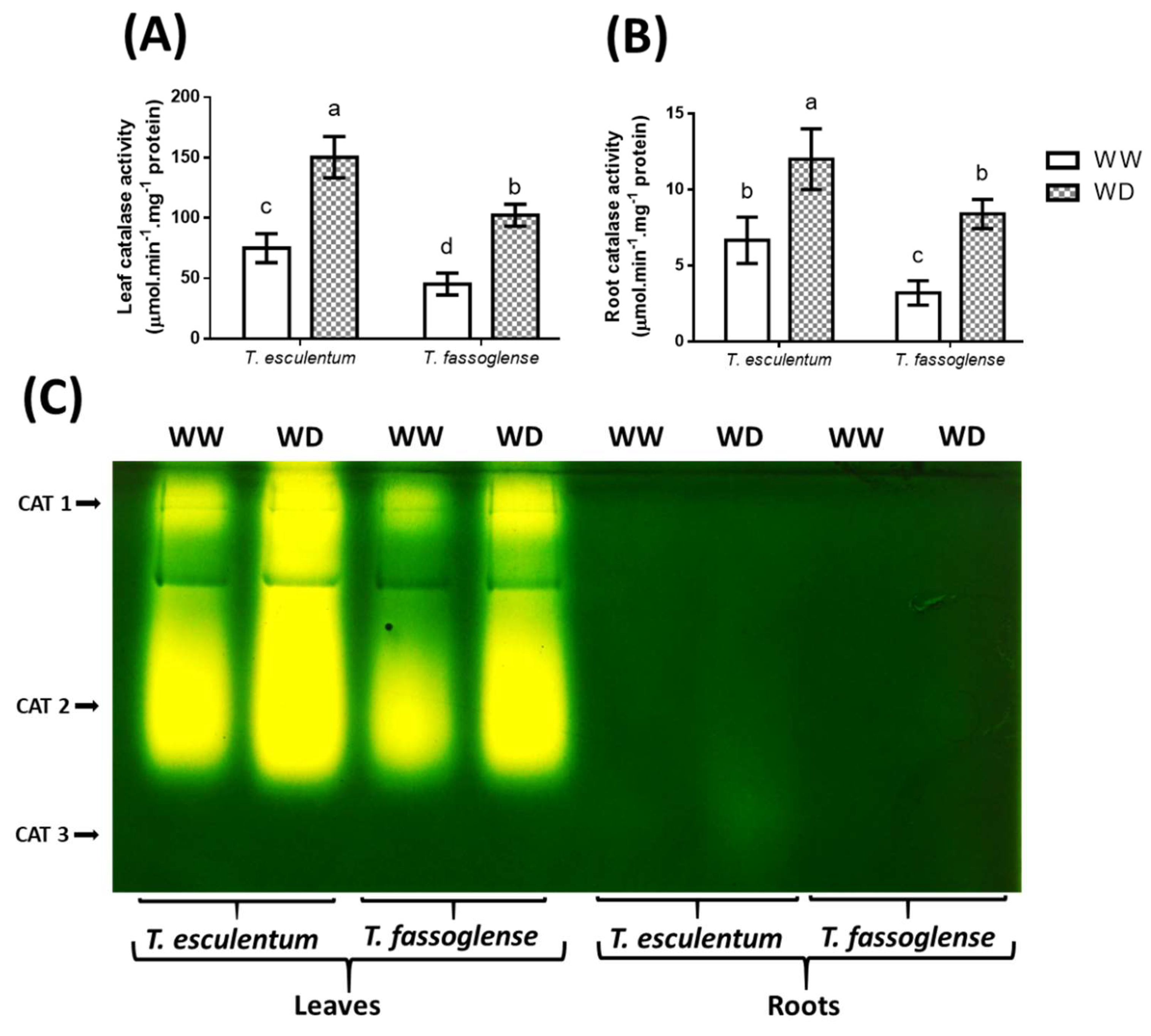

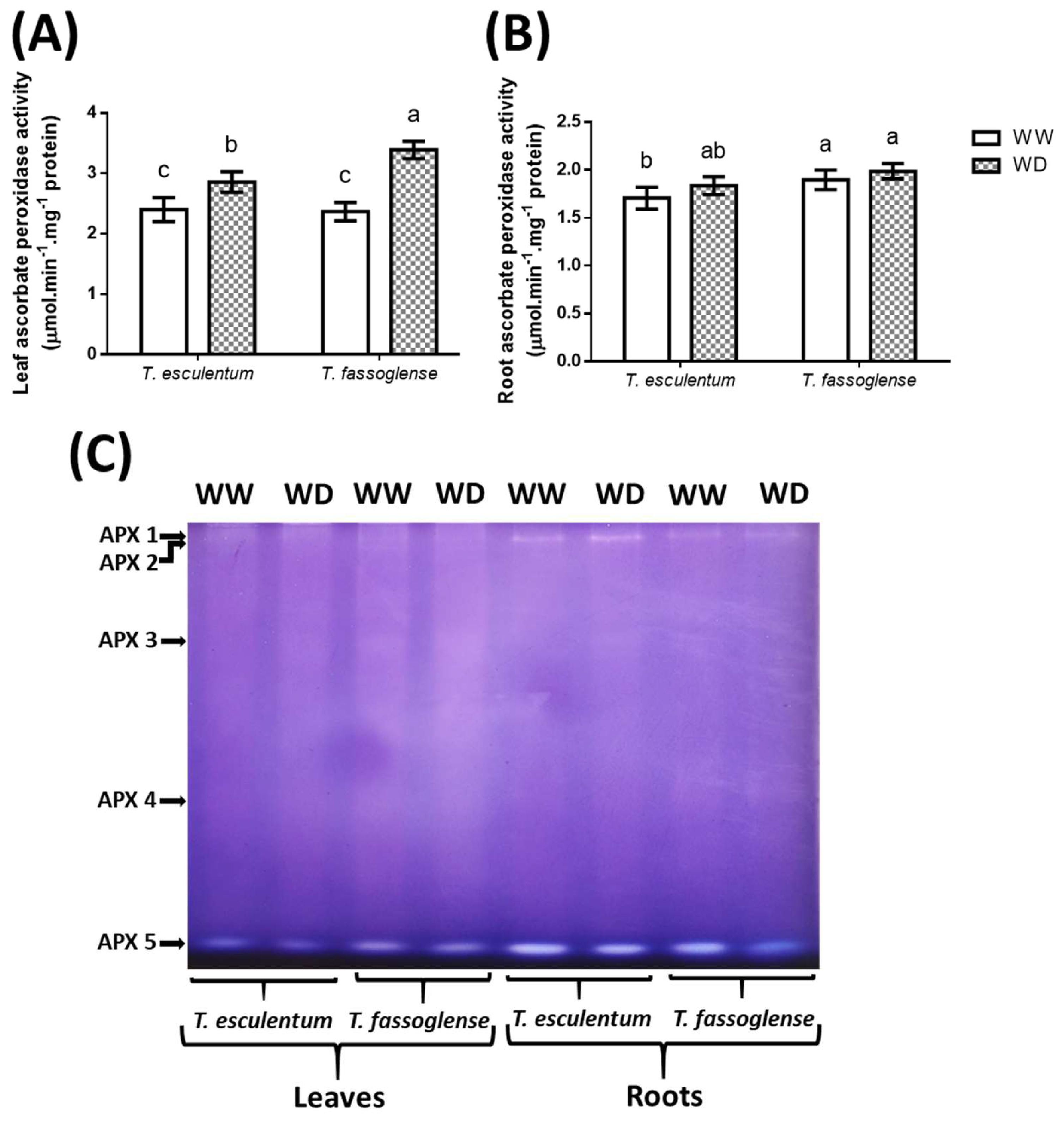

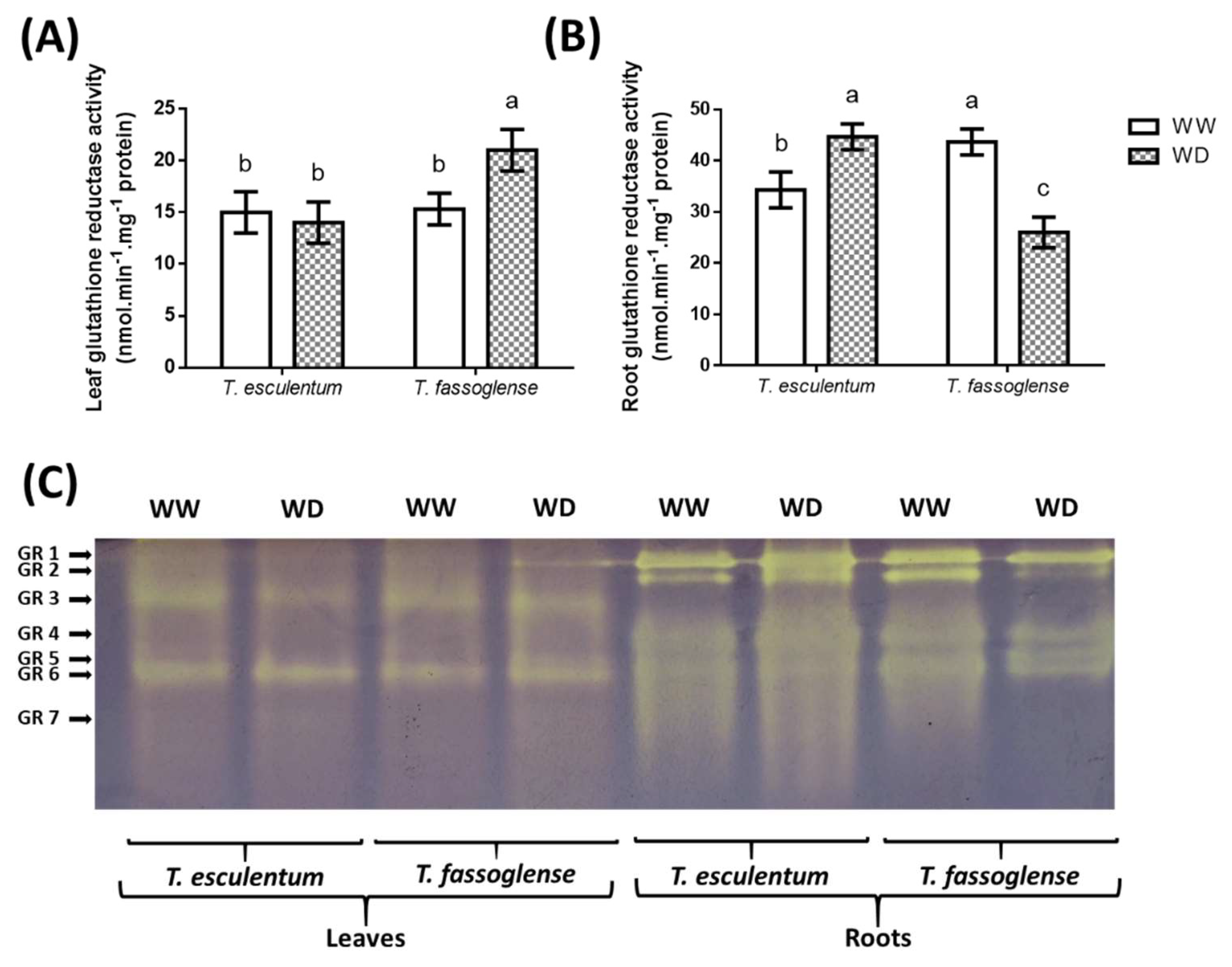

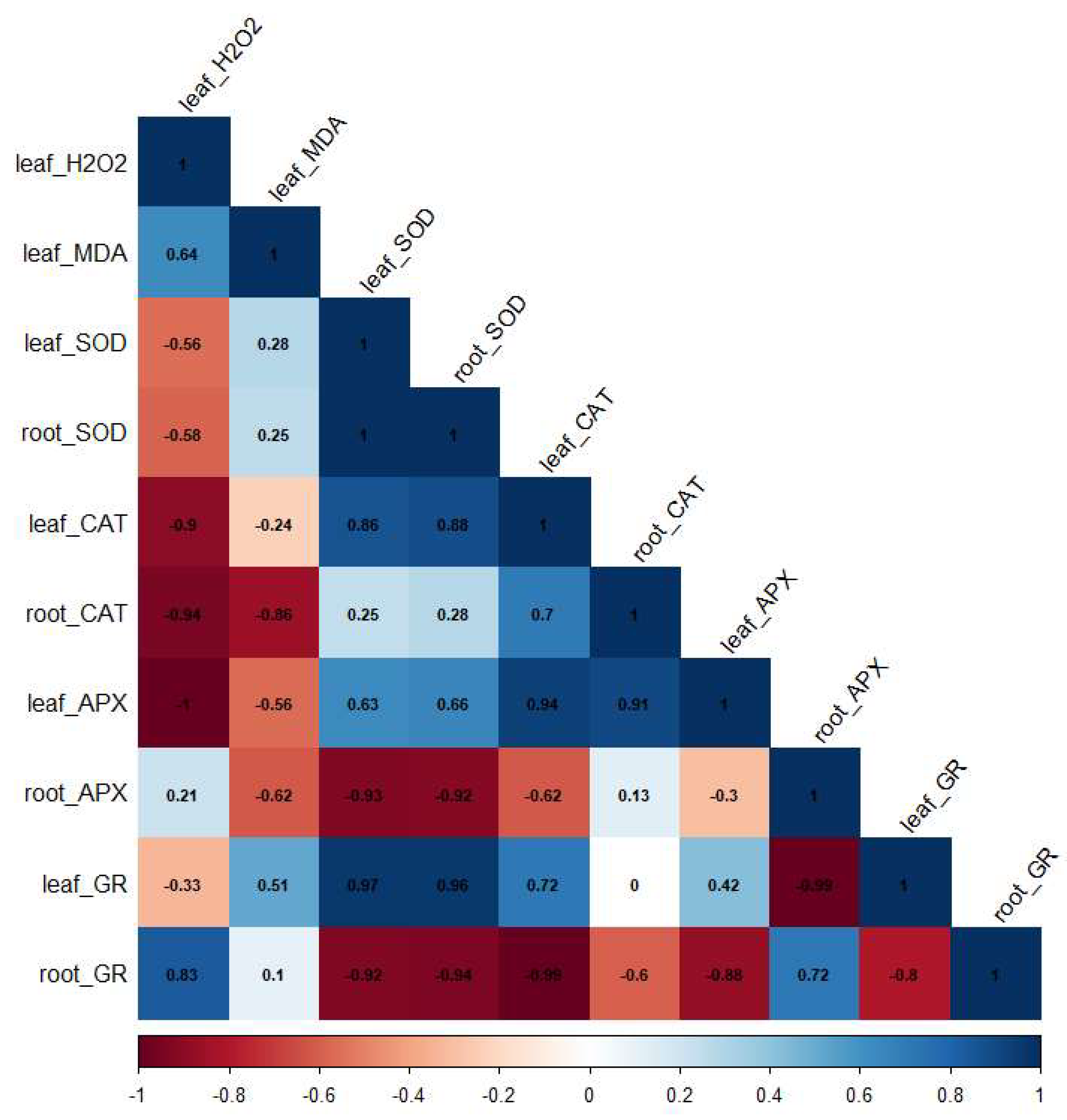

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mathivha, F.I.; Mabala, L.; Matimolane, S.; Mbatha, N. El Niño-Induced Drought Impacts on Reservoir Water Resources in South Africa. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.J.; Loake, G.J. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates and cognate redox signalling in disease resistance. Plant Physiol 2000, 124, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxa, M.; Liebthal, M.; Telman, W.; Chibani, K.; Dietz, K.J. The Role of the Plant Antioxidant System in Drought Tolerance. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Song, S.; Dong, S. Physiological response of soybean plants to water deficit. Front. Plant Sci 2022, 12, 809692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, H.; Mohan, B.S.; Prem, L.B. Towards developing drought-smart soybeans. Front. Plant Sci 2021, 12, 750664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, C.; Ma, C.; Liu, L. A study on soybean responses to drought stress and rehydration. Saudi J. Biol. Sci 2019, 26, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morosan, M.; Hassan, M.; Naranjo, M.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Boscaiu, M.; Vicente, O. Comparative analysis of drought responses in Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean) and P. coccineus (runner bean) cultivars. The Euro. Biotech. J 2017, 1, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsamadany, H. Physiological, biochemical and molecular evaluation of mung bean genotypes for agronomical yield under drought and salinity stresses in the presence of humic acid. Saudi J. Biol. Sci 2022, 29, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlar, A.; Kidrič, M.; Šuštar-Vozlič, J.; Pipan, B.; Zadražnik, T.; Meglič, V. Drought stress response in agricultural plants: A case study of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). In Drought-Detection and Solutions; Intech Open: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.A.C.; Keys, A.J.; Madgwick, P.J.; Parry, M.A.J.; Lawlor, D.W. Adaptation of photosynthesis in marama bean Tylosema esculentum (Burchell A. Schreiber) to a high temperature, high radiation, drought-prone environment. Plant Physiol. Biochem 2005, 43, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.W. Potential of underutilized traditional vegetables and legume crops to contribute to food and nutritional security, income and more sustainable production systems. Sustainability 2014, 6, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakora, F.D. Biogeographic distribution, nodulation and nutritional attributes of underutilized indigenous African legumes. Acta. Hortic 2013, 979, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, S.; Paulo, S.; Antonio, P.C.; Estrela, F. Systematic studies in Tylosema (Leguminosae). Bot. J. Linnean Soc 2005, 147, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Aremu, A.O. Marama bean Tylosema esculentum (Burch.) A. Schreib: an indigenous plant with potential for food, nutrition, and economic sustainability. Food Funct 2021, 12, 2389–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullis, C.; Chimwamurombe, P.; Barker, N.; Kunert, K.; Vorster, J. Orphan legumes growing in dry environments: Marama bean as a case study. Front. Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holse, M.; Husted, S.; Hansen, A. Chemical composition of Marama bean (Tylosema esculentum): A wild African bean with unexploited potential. J Food Compos. Anals 2010, 23, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepolo, E.; Takundwa, M.; Chimwamurombe, P.M.; Cullis, C.A.; Kunert, K. A review of geographical distribution of marama bean [Tylosema esculentum (Burchell) Schreiber] and genetic diversity in the Namibian germplasm. Afr. J. Biotechnol 2009, 8, 2088–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.M. Marama bean (Tylosema esculentum, Fabaceae) seed crop in Texas. Econ. Bot 1987, 41, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cullis, C. The multipartite mitochondrial genome of Marama (Tylosema esculentum). Front. Plant Sci 2021, 12, 787443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, M.; Belay, G. Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 1. Cereals and Pulses. Fondation PROTA; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anywar, G.; Kakudidi, E.; Byamukama, R.; Mukonzo, J.; Schubert, A.; Oryem-Origa, H. Medicinal plants used by traditional medicine practitioners to boost the immune system in people living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Eur. J. Integr. Med 2020, 35, 1876–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonsou, E.; Taylor, J.; Minnaar, A. Microstructure of protein bodies in marama bean species. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingwaru, W.; Majinda, R.T.; Yeboah, S.O.; Jackson, J.C.; Kapewangolo, P.T.; Kandawa-Schulz, M.; Cencic, A. Tylosema esculentum (Marama) tuber and bean extracts are strong antiviral agents against rotavirus infection. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2011, 2011, 284795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapesa, W.A.; Waweru, M.P.; Bukachi, F.; Wafula, K.D. Aqueous tuber extracts of Tylosema fassoglense (kotschy ex schweinf.) torre and hillc.(fabaceae). Possess significant in-vivo antidiarrheal activity and ex-vivo spasmolytic effect possibly mediated by modulation of nitrous oxide system, voltage-gated calcium channels, and muscarinic receptors. Front. Pharmacol 2021, 12, 636879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munialo, S.; Gasparatos, A.; Ludidi, N.; Ali, A.E.E.; Keyster, E.; Akanbi, M.O.; Emmambux, M.N. Systematic Review of the Agro-Ecological, Nutritional, and Medicinal Properties of the Neglected and Underutilized Plant Species Tylosema fassoglense. Sustainability 2024, 16, p6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigen, G.; Maritim, A.; Some, F.; Kibosia, J.; Rono, H.; Chepkwony, S.; Kipkore, W.; Wanjoh, B. Ethnopharmacological survey of the medicinal plants used in Tindiret, Nandi County, Kenya. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med 2016, 13, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudamba, A.; Kasolo, J.N.; Bbosa, G.S.; Lugaajju, A.; Wabinga, H.; Niyonzima, N.; Ocan, M.; Damani, A.M.; Kafeero, H.M.; Ssenku, J.E.; Alemu, S.O. Medicinal plants used in the management of cancers by residents in the Elgon Sub-Region, Uganda. BMC complement. med. Ther 2023, 23, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolo, Z.; Majola, A.; Phillips, K.; Ali, A.E.E.; Sharp, R.E.; Ludidi, N. Water Deficit-Induced Changes in Phenolic Acid Content in Maize Leaves Is Associated with Altered Expression of Cinnamate 4-Hydroxylase and p-Coumaric Acid 3-Hydroxylase. Plants 2023, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.E.; Husselmann, L.H.; Tabb, D.L.; Ludidi, N. Comparative Proteomics Analysis between Maize and Sorghum Uncovers Important Proteins and Metabolic Pathways Mediating Drought Tolerance. Life 2023, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.E.; Ludidi, N. Antioxidant responses are associated with differences in drought tolerance between maize and sorghum. J. Oasis Agric. Sustain 2021, 3, pp.1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide Dismutase: Improved Assays and an Assay Applicable to Acrylamide Gels. Anal. Biochem 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; and Asada, K. . Purification of ascorbate peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts: its inactivation in ascorbate depleted medium and reactivation by monodehydroascorbate radical. Plant Cell Physiol 1987, 28, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lück, H. Catalase. In Method of Enzymatic Analysis; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Academic Press: New York and London, 1965; pp. 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Halliwell, B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: a proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta 1976, 133, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seckin, B.; Turkan, I.; Sekmen, A.H.; Ozdan, C. The role of antioxidant defense systems at differential salt tolerance of Hordeum marinum Huds. (Sea barley grass) and Hordeum vulgare L. (cultivated barley). Environ. Exp. Bot 2010, 69, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Shiozawa, A.; Banno, S.; Fukumori, F.; Ichiishi, A.; Kimura, M.; Fujimura, M. Involvement of OS-2 MAP kinase in regulation of the large-subunit catalases CAT-1 and CAT-3 in Neurospora crassa. Genes Genet. Syst 2007, 82, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.V.; Paliyath, G.; Ormrod, D.P. Ultraviolet-B-and ozone-induced biochemical changes in antioxidant enzymes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 1996, 110, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanos, A.J.; Travlos, I.S. The water relations and some drought tolerance mechanisms of the marama bean. J. Agron 2012, 104, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Weng, B.; Jing, L.; Bi, W. Effects of drought stress on water content and biomass distribution in summer maize (Zea mays L.). Front. Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1118131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.S.; Li, F.M.; Xu, H. Deficiency of water can enhance root respiration rate of drought-sensitive but not drought-tolerant spring wheat. Agric. Water Manag 2004, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yadav, V.; Zhao, W.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, C. Drought-induced proline is mainly synthesized in leaves and transported to roots in watermelon under water deficit. Hortic. Plant J 2022, 8, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.S.; Ma, H.Y.; Li, X.W.; Wei, L.X.; Lv, H.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Jiang, C.J.; Liang, Z.W. Proline accumulation is not correlated with saline-alkaline stress tolerance in rice seedlings. J. Agron 2015, 107, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Luo, Q.; Tian, Y.; Meng, F. Physiological and proteomic analyses of the drought stress response in Amygdalus mira (Koehne) Yü et Lu roots. BMC Plant Biol 2017, 17, .1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyster, M.; Klein, A.; Du Plessis, M.; Jacobs, A.; Kappo, A.; Kocsy, G.; Galiba, G.; Ludidi, N. Capacity to control oxidative stress-induced caspase-like activity determines the level of tolerance to salt stress in two contrasting maize genotypes. Acta Physiol Plant 2013, 35, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed-Moucheshi, A.; Sohrabi, F.; Fasihfar, E.; Baniasadi, F.; Riasat, M.; Mozafari, A.A. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a selection criterion for triticale grain yield under drought stress: a comprehensive study on genomics and expression profiling, bioinformatics, heritability, and phenotypic variability. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Chen, M.; Su, Y.; Wu, N.; Yuan, M.; Yuan, S.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Comparison on photosynthesis and antioxidant defense systems in wheat with different ploidy levels and octoploid triticale. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynova, I.M.; Aliyeva, D.R.; Aliyev, J.A. Subcellular localization and responses of superoxide dismutase isoforms in local wheat varieties subjected to continuous soil drought. Plant Physiol. Biochem 2014, 81, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, F.; Hu, B.; Jia, Y.; Sha, H.; Zhao, H. Differential activity of the antioxidant defence system and alterations in the accumulation of osmolyte and reactive oxygen species under drought stress and recovery in rice (Oryza sativa L.) tillering. Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.K.; Rajkumar, B.K.; Kumar, V. Differential responses of antioxidants and osmolytes in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) cultivars contrasting in drought tolerance. Plant Stress 2021, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, A.; Noctor, G.; Baker, A. Plant catalases: peroxisomal redox guardians. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2012, 525, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpas, F.J. What is the role of hydrogen peroxide in plant peroxisomes? Plant Biol 2015, 17, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, V.; Kaur, N.; Gupta, A.K. Evaluation of oxidative stress tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings in response to drought. Indian J Biochem Biophys 2011, 48, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.D. Drought stress and reactive oxygen species. Plant Signal Behav 2008, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallie, D.R. L-ascorbic acid: a multifunctional molecule supporting plant growth and development. Scientifica 2013, 2013, 795964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Malagoli, M.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R. Drought stress in maize causes differential acclimation responses of glutathione and sulfur metabolism in leaves and roots. BMC Plant Biol 2016, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Kaur, K.; Gupta, A.K. Salicylic acid induces differential antioxidant response in spring maize under high temperature stress. Indian J. Exp. Biol 2016, 54, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kirkham, M.B. Antioxidant responses to drought in sunflower and sorghum seedlings. New Phytol 1996, 132, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahantaniaina, M.S.; Li, S.; Chatel-Innocenti, G.; Tuzet, A.; Mhamdi, A.; Vanacker, H.; Noctor, G. Glutathione oxidation in response to intracellular H2O2: key but overlapping roles for dehydroascorbate reductases. Plant Signal. Behav 2017, 12, 1356531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).