1. Introduction

The history of aviation is marked by significant milestones in technology, safety, and operational advancements. From the Wright brothers’ first powered flight in 1903 to the supersonic speeds of Concorde and the advanced automation of modern commercial jets, aviation has consistently pushed the boundaries of what is possible. Early pioneers faced considerable challenges, including unreliable engines, rudimentary aerodynamics, and limited materials science knowledge. Early aircraft, often constructed from wood and fabric, were prone to wear and structural failures. Compounding these issues were adverse weather conditions, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of standardized safety protocols, making early flight both daring and high-risk [

1].

Advances in material technology have been pivotal in addressing these challenges, transforming aviation into a safer and more reliable mode of transportation. The introduction of lightweight metals like aluminum in the 1920s revolutionized aircraft design, enabling stronger, more durable airframes while maintaining fuel efficiency [

2]. In later decades, composite materials such as carbon fiber provided unparalleled strength, flexibility, and resistance to fatigue and corrosion. These innovations enhanced safety, reduced weight, and extended the operational lifespan of modern aircraft [

3].

Technological advancements have also shaped other aspects of aviation. The evolution of engines from piston-driven to jet propulsion increased speed, range, and reliability, while avionics innovations reduced human error and operational workload [

4]. Today, aviation is one of the safest modes of transportation, reflecting the relentless efforts of engineers, scientists, and regulators. These breakthroughs have also made air travel more accessible, connecting people and cultures worldwide.

Despite these advancements, accidents have remained a persistent concern throughout aviation history. In the early years, accidents were frequent and catastrophic, often caused by unreliable engines, limited pilot training, and unpredictable weather. Over time, as technologies and operations became more complex, the nature of accidents evolved to include both human and technical factors. Human errors, such as miscommunication or procedural deviations, remain the leading cause of incidents. However, technical failures, including engine malfunctions, structural weaknesses, and environmental factors, like severe weather or runway conditions, pose significant risks [

5].

To address these challenges, organizations like the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) have developed robust accident investigation frameworks. These efforts have enhanced understanding, prevention, and mitigation strategies, leading to a steady decline in accident rates. However, with growing air traffic and evolving technologies, the aviation industry must continuously adapt to emerging risks.

Among these risks, material degradation mechanisms, such as Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE), have emerged as critical technical challenges. HE has been identified as a significant factor in several catastrophic aviation failures, particularly in high-strength metallic components exposed to cyclic loads and environmental stresses. Understanding these incidents is crucial for developing targeted mitigation strategies and improving aviation safety.

The NTSB aviation database highlights the complexity of aviation safety. Database has a total of 176,673 recorded accidents and incidents, and only 61,492 cases include detailed explanations of probable causes [

6]. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing diverse issues, including human performance, technical reliability, structural integrity, and aerodynamic functionality, to improve safety.

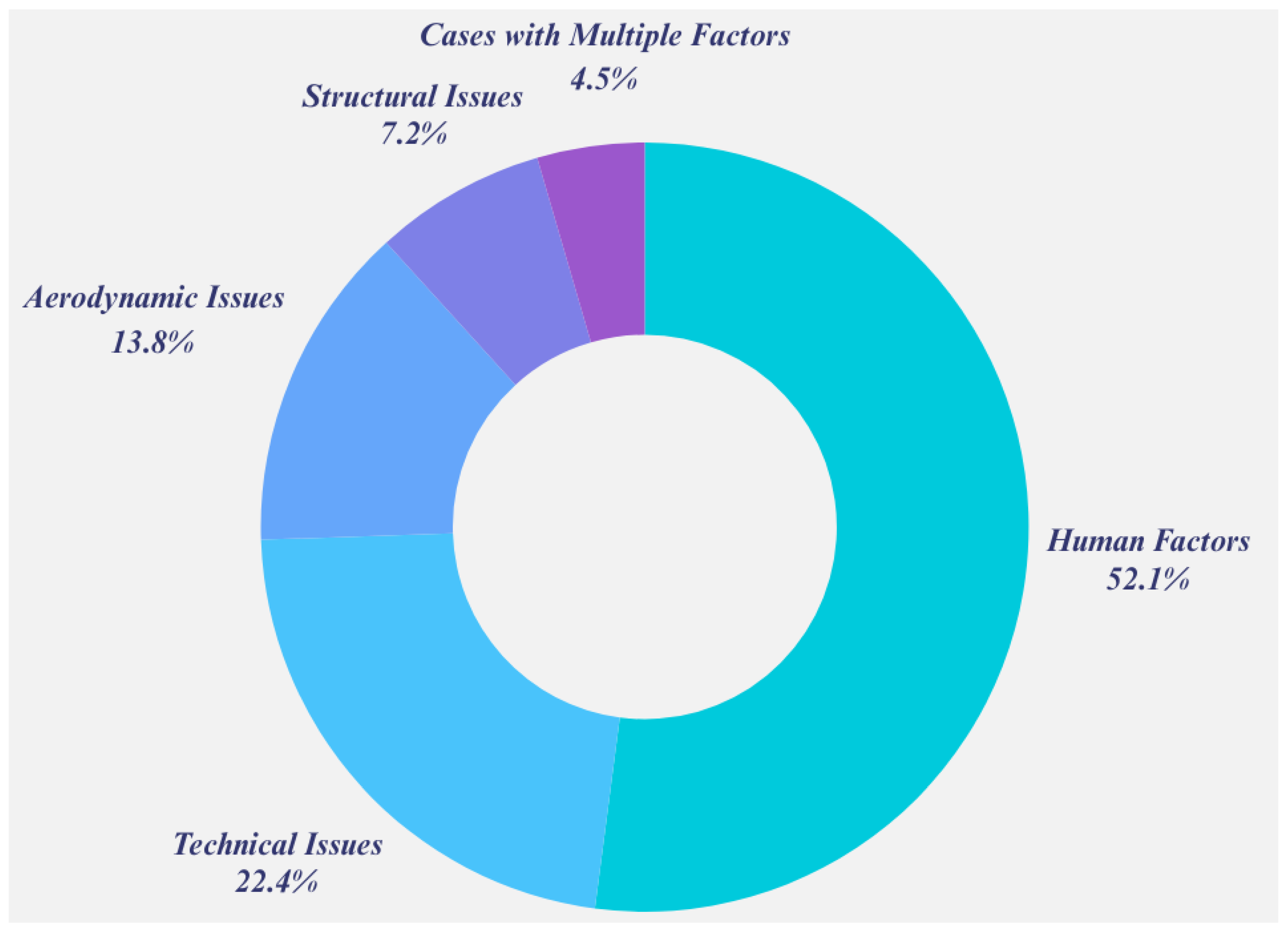

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of cases with probable causes. Human factors account for 52.1% of incidents, emphasizing the critical role of pilot performance and decision-making. Technical issues contribute 22.4%, highlighting the importance of engine reliability, maintenance, and electronic systems. Aerodynamic performance accounts for 13.8% of cases, reflecting challenges such as directional control and airspeed management. Structural issues comprise 7.2%, encompassing material fatigue, corrosion, and design failures, while cases involving multiple factors represent 4.2%. This distribution underscores the dominance of human-related factors while also highlighting the need to address technical and structural challenges to improve aviation safety further.

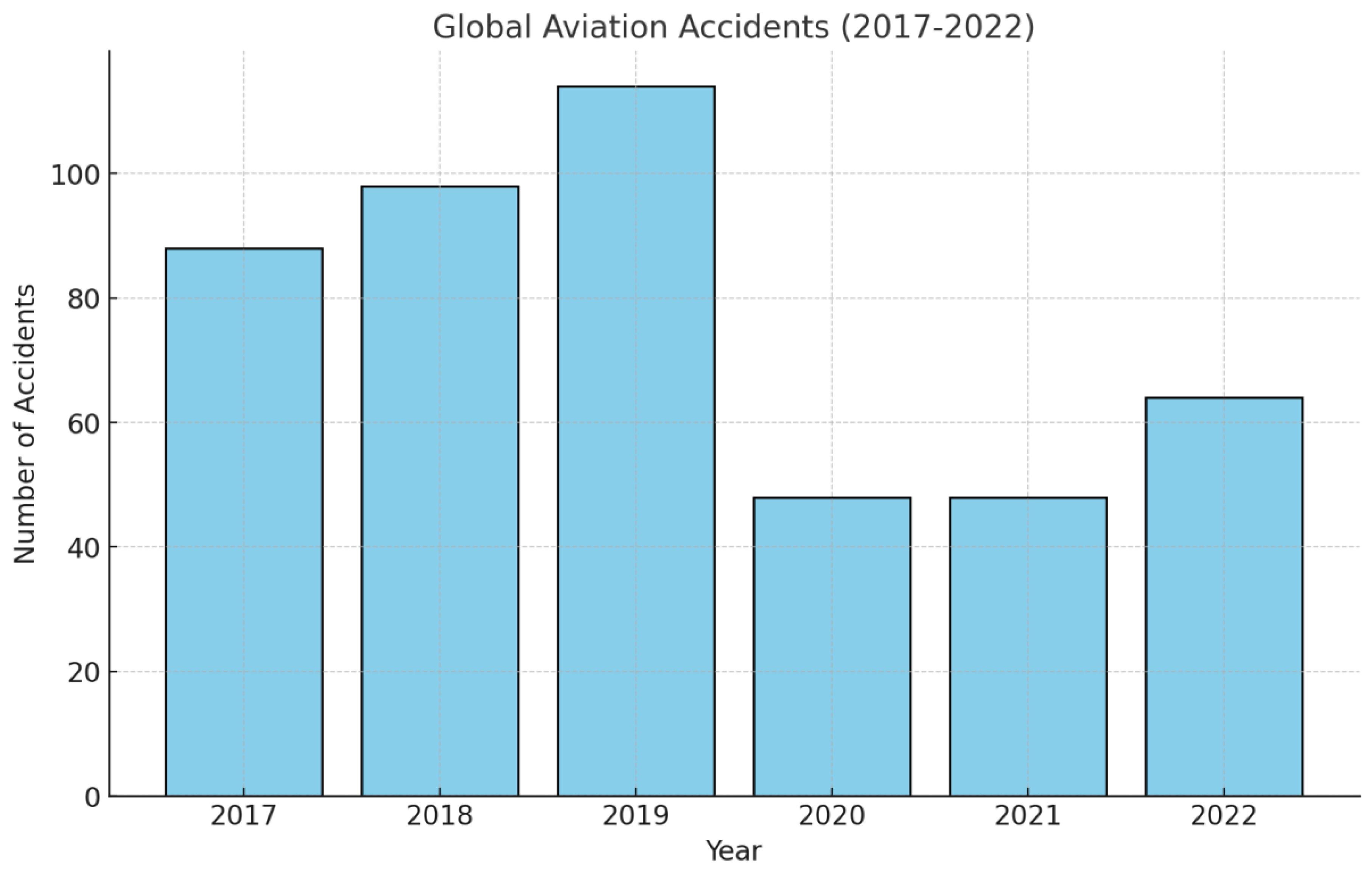

Figure 2 illustrates the annual number of global aviation accidents in scheduled commercial air transport operations. According to ICAO safety reports, accident numbers fluctuated during this period [

7]. The highest number of accidents occurred in 2019, with 114 incidents preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic years 2020 and 2021 saw a significant decline, with only 48 accidents each year, likely due to reduced air traffic. In 2022, as aviation activities resumed, accidents increased to 64. This data reflects the correlation between operational volume and accident occurrence, emphasizing the need for vigilance as air traffic normalizes.

According to ICAO safety reports,

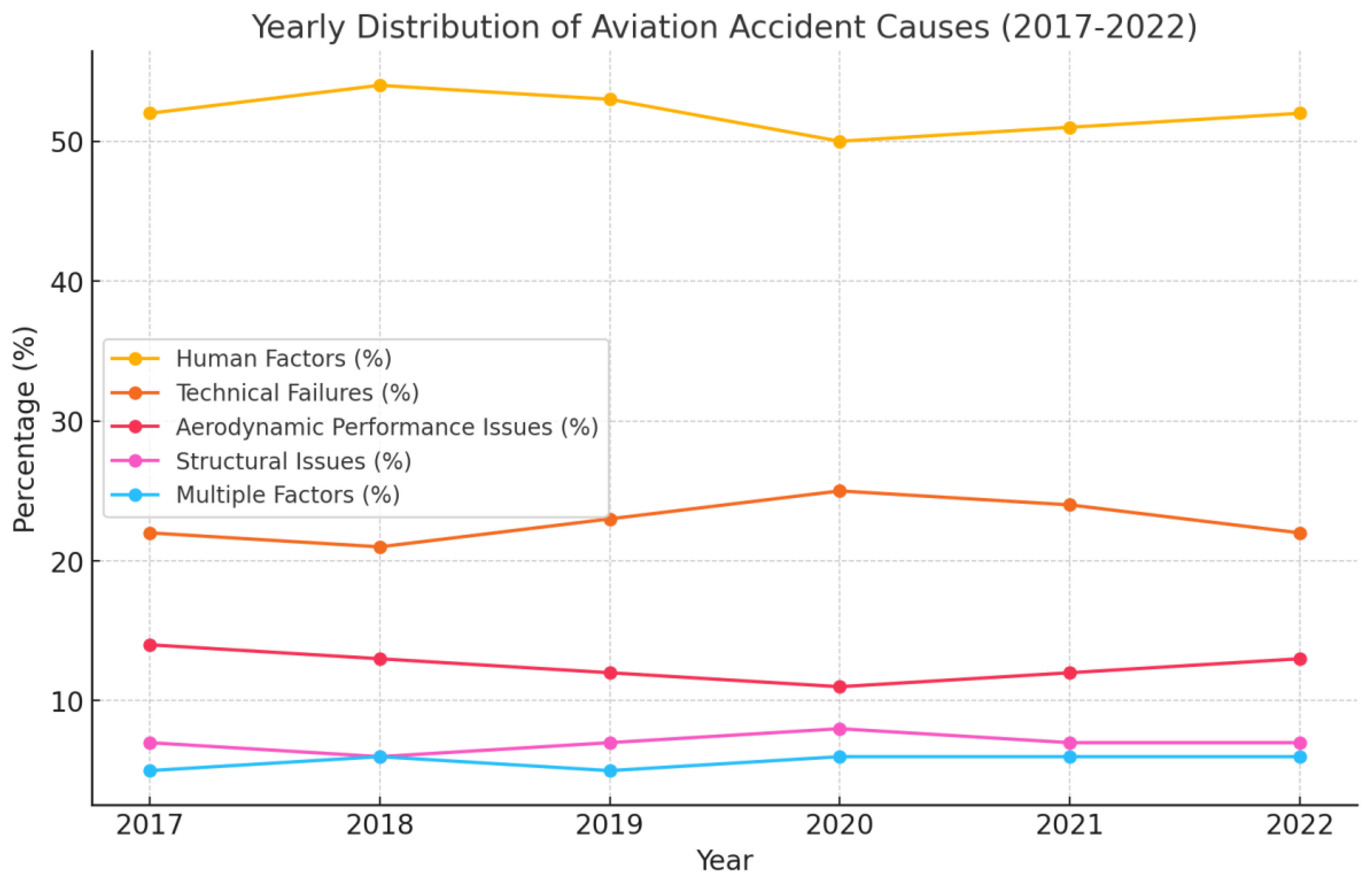

Figure 3 highlights the percentage distribution of aviation accident causes from 2017 to 2022 [

7]. Human factors consistently represent the largest share, ranging between 50% and 54%, reinforcing their significant role in aviation safety. Technical failures, the second-largest contributor, account for 21% to 25% of accidents, underscoring the importance of reliable systems and maintenance. Aerodynamic performance issues remain relatively steady at 11% to 14%, while structural issues contribute 6% to 8%. Cases involving multiple factors hover around 5% to 6%, reflecting the complexity of interactions in aviation incidents. This distribution underscores the need for targeted improvements in both technical and operational domains.

Among the multifaceted challenges in aviation safety, material degradation mechanisms like Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) require focused attention due to their potential to cause catastrophic failures. Characterized by hydrogen absorption and diffusion into metallic components, HE poses significant risks, especially in environments where high-strength materials are exposed to hydrogen during manufacturing, maintenance, or service. Notable aviation incidents have implicated HE, underscoring the need for comprehensive analysis and mitigation strategies. The importance of this study lies in its detailed presentation of real-world aviation incidents and accidents linked to hydrogen embrittlement, supported by concrete evidence and metallurgical analysis. Unlike many aviation safety studies that predominantly focus on statistical analyses, this work provides an in-depth examination of documented cases, bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical implications. This review aims to shed light on critical vulnerabilities and offer actionable solutions to improve aviation safety by emphasizing robust material selection, manufacturing controls, and post-processing techniques.

2. Airworthiness Directives

Airworthiness Directives (ADs) are essential regulatory mandates designed to ensure the flight safety and operational reliability of aircraft [

8]. The mentioned directives, typically issued by aviation authorities like the FAA, EASA and National Airworthiness Authorities (NAA) address identified unsafe conditions in aircraft systems, engines, or components that could compromise flight safety. ADs often emerge following accident investigations, recurring operational issues, or identified manufacturing flaws, requiring operators to take specific corrective actions such as inspections, modifications, or part replacements. Their primary goal is to mitigate risks, ensure continued airworthiness, and prevent further incidents [

9].

When a safety concern arises, manufacturers are often required to thoroughly assess the affected components or systems, identifying root causes and providing solutions. In some cases, this process may lead to an immediate grounding of aircraft or urgent part replacements under an AD to prevent further risks. For instance, ADs might mandate inspections to detect hidden defects, operational restrictions to mitigate risk, or the replacement of defective parts with redesigned or higher-quality alternatives. This collaborative approach between regulatory bodies, manufacturers, and operators ensures that identified issues are promptly resolved, safeguarding aviation safety.

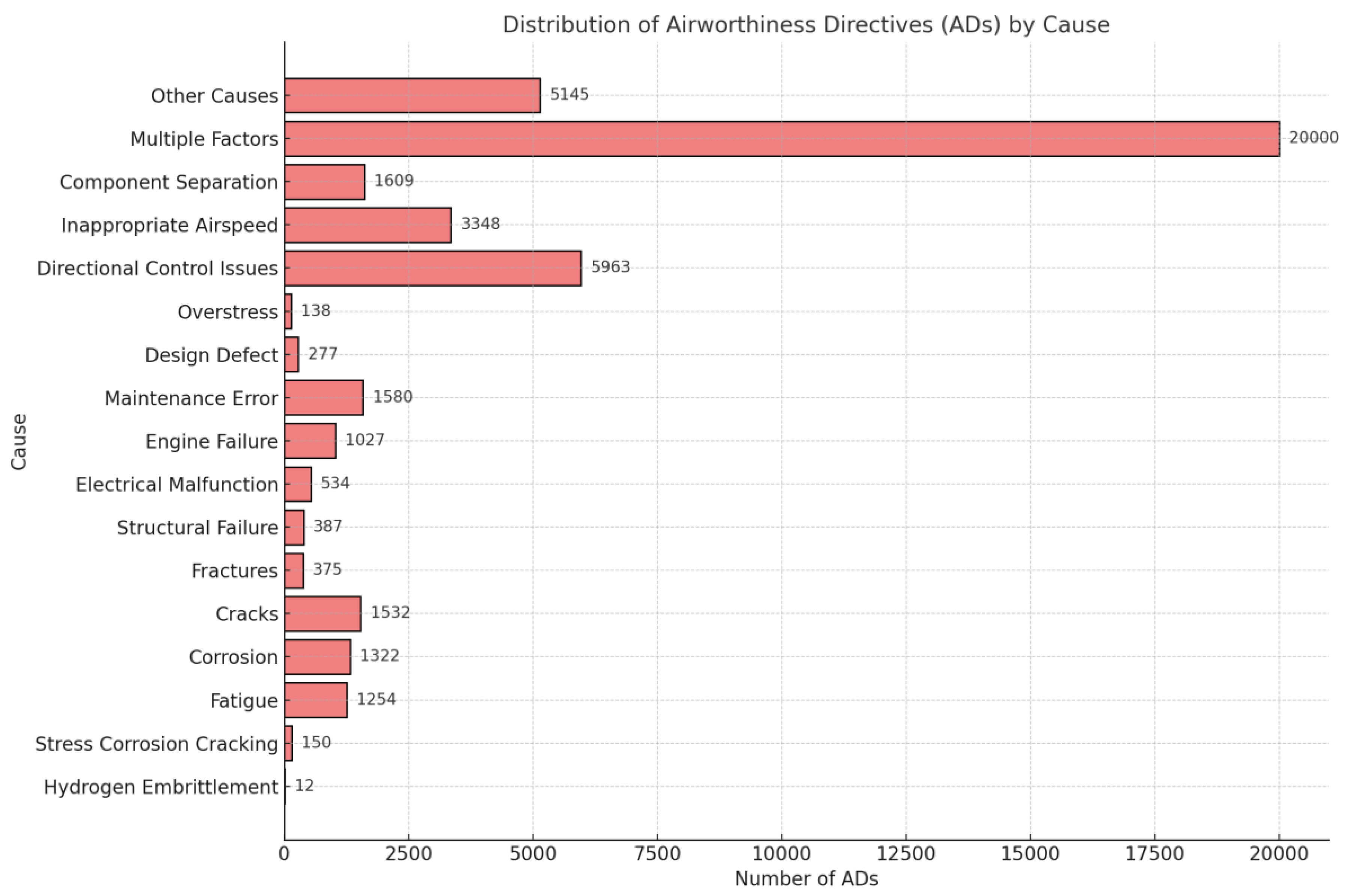

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the FAA has issued 167,751 ADs addressing a wide variety of concerns [

10]. Among these, operational issues like directional control (5,963 ADs) and inappropriate airspeed (3,348 ADs) dominate, reflecting the complexity of managing real-world flight conditions. Structural challenges, such as cracks (1,532 ADs), corrosion (1,322 ADs), and fatigue (1,254 ADs), also represent critical focus areas. While less frequent, issues like hydrogen embrittlement (HE) and stress corrosion cracking account for 12 and 150 ADs, respectively. Although small, these ADs highlight the significant risks posed by material degradation in critical components, requiring precise mitigation efforts.

The inclusion of hydrogen embrittlement among ADs emphasizes the growing recognition of material failures in aviation safety. Hydrogen embrittlement has been implicated in failures of critical parts like landing gear struts, crankshaft bolts, and helicopter drive assemblies. While accounting for only 12 ADs, HE incidents demonstrate the catastrophic potential of undetected material weaknesses, often introduced during manufacturing processes such as electroplating or insufficient post-treatment baking.

This transition from broader AD-related concerns to the specific challenges of HE underscores the need for precise manufacturing protocols and rigorous maintenance practices. In the following section, an in-depth exploration of hydrogen embrittlement, its mechanisms, and real-world impacts will illuminate this critical aviation safety challenge.

3. Hydrogen Embrittlement in Aviation: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Case Studies

Hydrogen-induced damage occurs when hydrogen atoms diffuse into metals, leading to mechanical property degradation, reduced ductility, and eventual failure [

11,

12,

13]. This phenomenon, known as hydrogen embrittlement (HE), presents significant challenges, particularly in industries such as aerospace and energy [

14]. The mechanisms behind HE includes complex mechanisms such as Hydrogen-Enhanced Local Plasticity (HELP) and Hydrogen-Enhanced Decoherence (HEDE), which alter the metal’s microstructure and increase susceptibility to cracking under stress [

15,

16,

17,

18]. HELP promotes dislocation movement and localized deformation, while HEDE weakens atomic bonds at grain boundaries, leading to brittle fractures [

19,

20]. Additionally, processes like Adsorption-Induced Dislocation Emission (AIDE) facilitate dislocation movement at crack tips, further contributing to embrittlement [

21]. These processes collectively alter a material’s microstructure, increasing its susceptibility to cracking under stress. Numerous studies have been conducted to better understand these mechanisms, providing valuable insights into how hydrogen interacts with different materials and the conditions that exacerbate embrittlement [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Aviation components are particularly vulnerable to hydrogen embrittlement due to their exposure to cyclic loads, harsh environmental conditions, and high material strength requirements. For example, in certain Airbus A380 aircraft, hydrogen-assisted cracking accelerated the development of cracks in wing spars after extended periods of storage in specific environmental conditions [

29]. Similarly, failures in helicopter drive systems and fixed-wing aircraft crankshaft bolts have been traced to hydrogen embrittlement introduced during manufacturing processes, such as electroplating and surface treatments [

30]. These incidents underscore the critical need for stringent manufacturing controls, post-processing treatments, and improved material testing methods to mitigate hydrogen-induced risks [

31,

32]. It is noteworthy that, by eliminating residual hydrogen and enhancing system reliability, flight safety can be significantly improved.

Efforts to mitigate HE focus on preventing hydrogen ingress and removing residual hydrogen through post-treatment processes. Advancements in protective treatments, such as anodizing, coatings (e.g., Al-Si-Zn, Zn-Ni, Graphene), and platings (e.g., Cr, Zn-Co, Zn-Ni, ZrN, Cd), have been developed. These methods aim to enhance corrosion resistance and act as barriers against hydrogen ingress during the service life of critical components [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, these protective methods can inadvertently introduce hydrogen into the material surface through chemical solution exposure [

44,

45,

46,

47]. If manufacturing controls and post-treatment processes are insufficient, parts subjected to high cyclic loads and environmental exposure, making them vulnerable to HE-related failures [

48,

49,

50]. Post-treatment processes such as baking and pulsed electric current, a heat treatment designed to remove residual hydrogen through diffusion, are critical for reducing the risk of embrittlement.

To address this issue, baking—a post-treatment heat treatment process—is designed to remove hydrogen introduced during manufacturing through diffusion, thereby reducing the risk of hydrogen embrittlement. This process operates under specific temperature and duration parameters, which vary depending on the material and are typically defined in manufacturer specifications [

51,

52]. However, the efficacy of this process is often assessed using specimens placed alongside the component during the process, leaving the component itself untested. This approach introduces uncertainties about the process’s reliability. Additionally, current verification methods, which predominantly rely on destructive testing, such as Thermal Desorption Analysis (TDA) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), limit the ability to evaluate components comprehensively [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, these methods necessitate component destruction, limiting their use to samples and making them impractical for widespread operational evaluations. These limitations highlight the need for more advanced techniques to ensure thorough hydrogen removal and component integrity [

58].

Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods are emerging as promising alternatives, offering the potential to evaluate materials and detect HE without damaging components. Techniques such as neutron imaging, x-ray diffraction, and electrochemical permeation testing demonstrate potential for real-time assessments [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. However, these technologies are still in developmental stages and have yet to be widely implemented on a large scale. The primary challenge lies in integrating such detection methods into the operational lifecycle, where design constraints and control requirements for HE-specific evaluations remain difficult to define.

This gap between current detection capabilities and the operational reality of aviation highlights the critical importance of robust manufacturing controls and maintenance practices. Failures due to HE, as underscored by documented incidents, often stem from lapses in manufacturing or post-processing protocols, such as insufficient dehydrogenation. Furthermore, the complexity of defining HE-specific detection and control measures exacerbates the difficulty of integrating effective solutions into design specifications.

The following sections delve into five detailed aviation incidents investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), where HE-induced failures played a significant role. These case studies not only illustrate the devastating potential of HE but also underline the urgency of implementing stringent quality control measures, effective maintenance strategies, and proactive regulatory oversight to prevent such occurrences. This synthesis of real-world events provides a crucial foundation for understanding the systemic improvements needed to mitigate HE risks in the aviation industry.

3.1. Failure of the Bell 412EP Helicopter (ERA10TA493)

On September 22, 2010, a Bell 412EP helicopter, encountered a critical mechanical failure during its final approach to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York. The sudden mechanical failure forced the pilot to execute an emergency autorotation landing into Jamaica Bay. Thankfully, all six crew members sustained only minor injuries, but the helicopter suffered significant damage, particularly to its powerplant system. The flotation devices, shown in

Figure 5, successfully deployed, preventing the helicopter from sinking despite the severe damage incurred during the emergency landing.

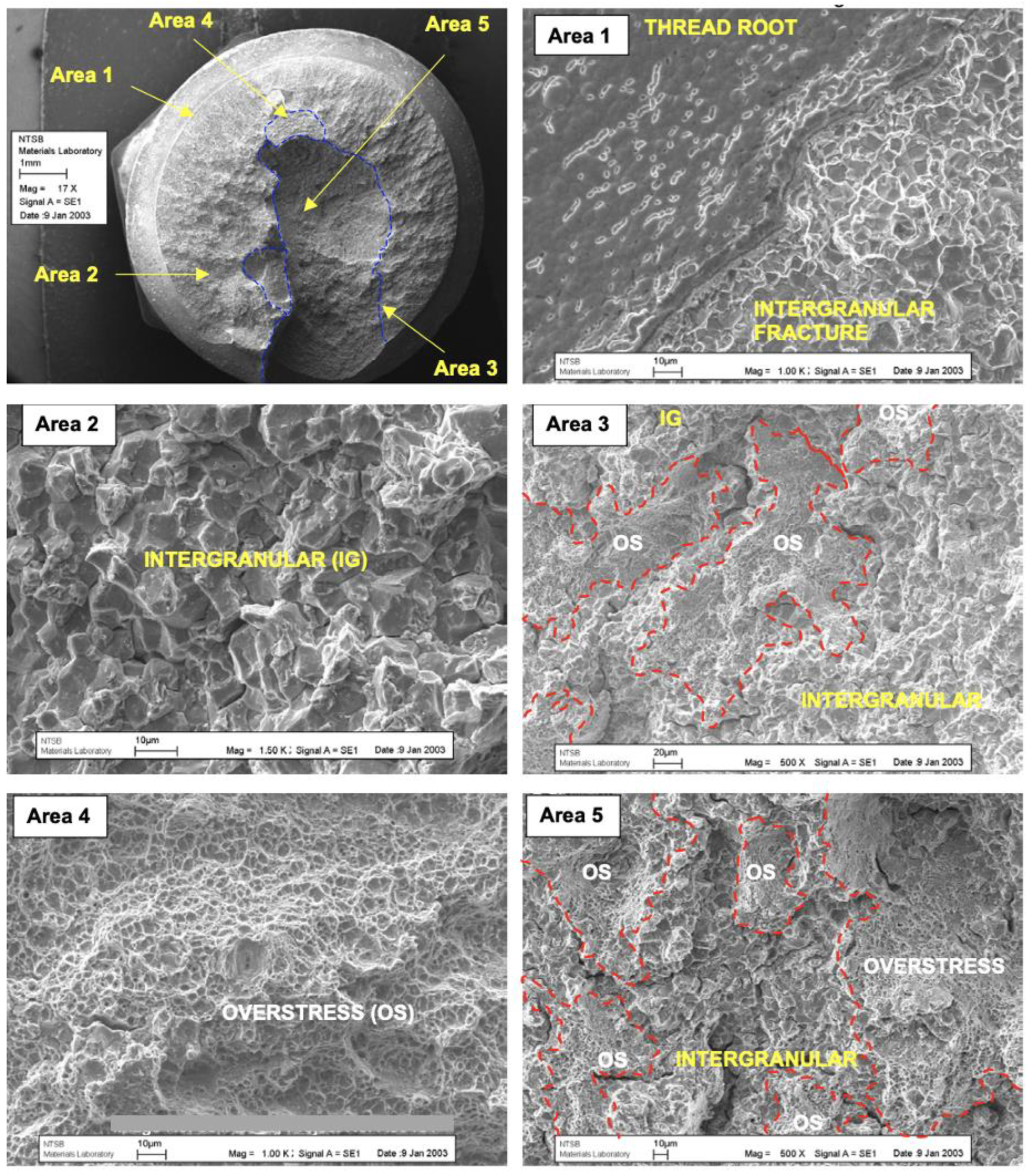

Subsequent investigations pinpointed the failure’s origin in the output drive gear (ODG) of the helicopter’s reduction gearbox. A detailed metallurgical analysis revealed a fatigue fracture that initiated at the root of one of the gear teeth, shown in

Figure 6. The fracture propagated due to hydrogen embrittlement (HE), a phenomenon where hydrogen atoms penetrate the metal, resulting in brittleness and cracking. The microscopic examination identified both intergranular and transgranular crack propagation patterns, which are hallmark indicators of hydrogen embrittlement.

The microscopic examination provided further insight into the failure mechanism. As depicted in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, intergranular cracking at the gear tooth root and distinct patterns of fatigue crack propagation were observed. The intergranular cracking, shown in

Figure 7, highlighted hydrogen’s role in weakening grain boundaries, making the material more susceptible to stress. Meanwhile,

Figure 8 revealed the propagation of fatigue cracks emanating from the hydrogen-embrittled region, with the microscopic evidence clearly indicating the insufficient removal of residual hydrogen during dehydrogenation treatments. Together, these findings confirmed hydrogen embrittlement as the root cause of the component’s failure.

The Bell 412EP incident underscores the urgent need for improved manufacturing controls and rigorous quality assurance to address hydrogen embrittlement risks. The current reliance on destructive testing for hydrogen detection is inadequate for comprehensive component evaluation. This incident exemplifies the critical importance of advancing non-destructive testing methods to identify residual hydrogen during manufacturing and maintenance. By implementing these improvements, the aviation industry can enhance the reliability of high-stress components and mitigate risks associated with hydrogen embrittlement.

3.2. Failure of the Bell 222U Helicopter (CEN10FA291)

On June 2, 2010, a Bell 222U helicopter suffered a catastrophic in-flight breakup during a post-maintenance flight near Midlothian, Texas. The helicopter, piloted by an airline transport pilot and accompanied by a mechanic, experienced structural failure that led to the separation of critical components, including the tail boom and main rotor hub. Witnesses reported seeing debris falling from the aircraft before it impacted the ground and erupted into flames, resulting in the tragic loss of both crew members.

Prior to the incident, the rotor components of the helicopter were reported as fully operational.

Figure 9 shows the rotor head assembly of the Bell 222U helicopter before the accident, with key components such as the A-side drive pin, B-side pitch link, and cyclic actuators clearly labeled.

Subsequent investigations revealed that the primary cause of the structural failure was the fracture of the A-side drive pin within the swashplate assembly. Metallurgical analysis identified the fracture as overstress-induced, but further detailed examination of the fracture surface revealed brittle cleavage features and intergranular separations consistent with hydrogen embrittlement (HE). Measurements taken from the fractured pin confirmed hydrogen levels between 8.7 and 9.3 ppm, indicating that absorbed hydrogen significantly contributed to material degradation.

Figure 10 shows the rotor components after disassembly, with failure points, including the A-side drive pin, highlighted.

Further examination under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) provided critical evidence of the brittle failure mechanism. The fractured surface of the A-side drive pin showed brittle cleavage and intergranular separations, highlighting how hydrogen atoms migrated into areas of high stress within the material. This accumulation of hydrogen weakened the structural bonds, leading to the failure of the drive pin under conditions it would normally withstand. Additionally,

Figure 11 shows radial cracks on the washer face of the A-side pin, further supporting hydrogen embrittlement as a key contributor to the failure. These cracks, observed at low magnifications, intersect the primary fracture and demonstrate localized plasticity near initiation sites where hydrogen atoms accumulated.

At higher magnifications, SEM analysis revealed ductile dimples adjacent to the main fracture surface, contrasting with brittle cleavage areas, as shown in

Figure 12. This contrast suggests that the failure initiated in brittle regions due to hydrogen embrittlement and propagated until the final stages, where localized ductility emerged in isolated areas.

These findings highlight the urgent need for strict hydrogen control during the manufacturing and maintenance of aviation components. The incident involving the Bell 222U helicopter emphasizes the importance of comprehensive post-treatment procedures, such as baking after cadmium plating, to effectively remove absorbed hydrogen. Without these precautions, residual hydrogen can significantly weaken high-strength materials, potentially resulting in catastrophic failures in critical aerospace systems.

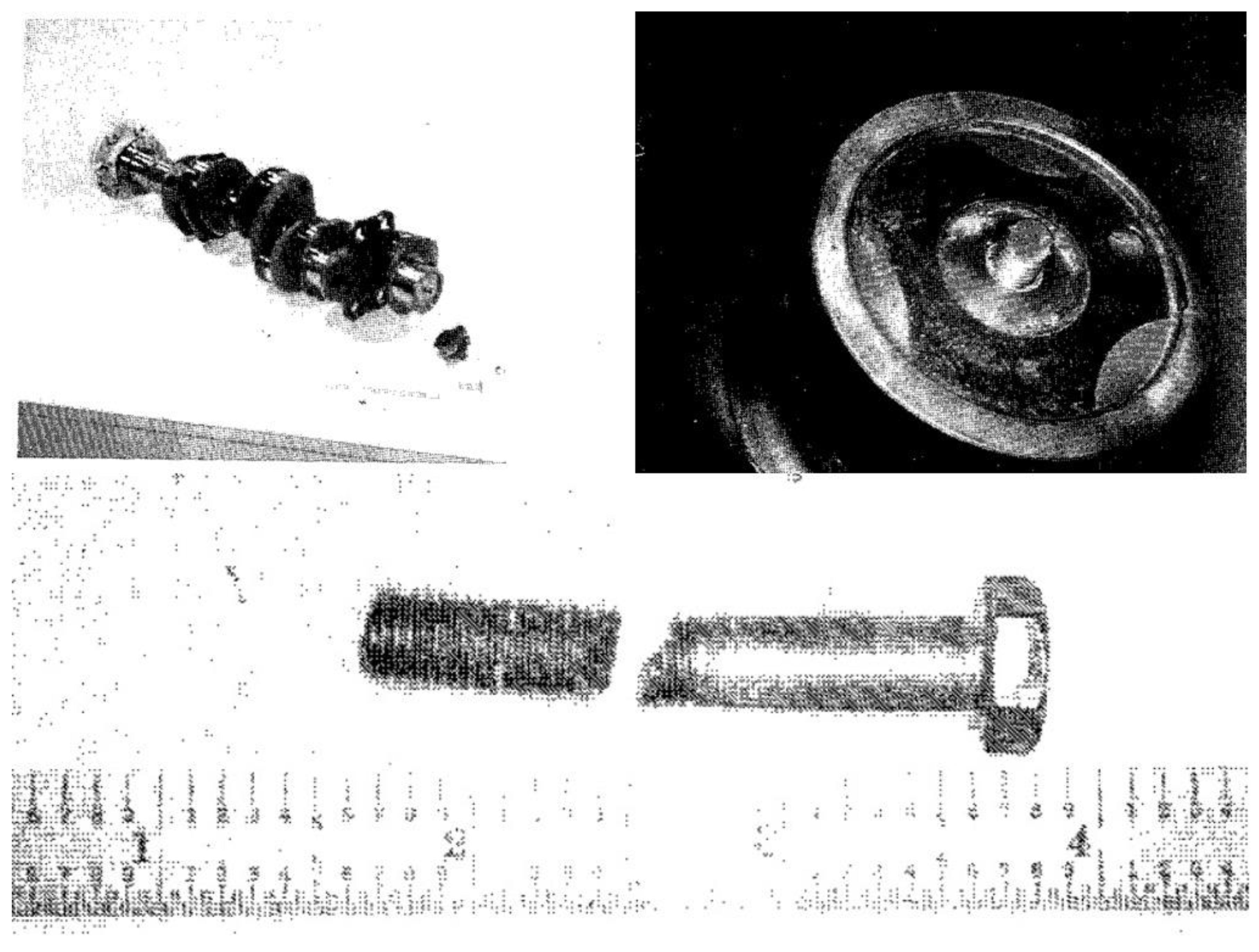

3.3. Failure of the Piper PA-32R-301T (IAD02FA091)

On September 8, 2002, a Piper PA-32R-301T experienced a catastrophic engine failure while cruising at 3,500 feet above Byram Township, New Jersey. The aircraft, operated by a private pilot, experienced a total loss of engine power due to the failure of the crankshaft gear retaining bolt, forcing a crash landing in a wooded area. The impact destroyed the aircraft, resulting in the deaths of the pilot and one passenger, with two others seriously injured.

Investigations identified the failed crankshaft gear bolt (part number STD-2209, SAE J429 grade 8 steel) as the root cause. Metallurgical analysis revealed hydrogen embrittlement as the primary failure mechanism. This condition was traced to residual hydrogen introduced during the zinc electroplating process. Unlike cadmium-plated bolts traditionally used, the substituted zinc-plated bolts lacked effective post-treatment baking, a critical step to mitigate hydrogen absorption.

Figure 13 shows the disassembled crankshaft assembly, highlighting the fractured bolt.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provided insights into the failure mode, as illustrated in

Figure 14. The fracture surface exhibited intergranular cracking and ductile failure patterns, hallmarks of hydrogen-assisted cracking. The fracture originated at the thread roots and propagated radially due to accumulated hydrogen, compromising the bolt’s integrity.

The problem of hydrogen embrittlement in zinc-plated bolts had been flagged earlier by Lycoming Engines following similar failures in O-540-F1B5 engines used in Robinson R44 helicopters. In response to these failures, Lycoming issued Special Service Advisory No. 48-798, mandating the replacement of zinc-plated bolts after limited operation hours. Despite these warnings, the substitution of cadmium with zinc-plated bolts persisted, leading to repeated incidents, including the Piper PA-32R-301T crash.

This case underscores the critical need for robust post-plating treatments, such as baking, to eliminate residual hydrogen effectively. It also highlights the importance of continuous monitoring and material verification, especially for high-stress components. In response to this incident, the FAA issued an emergency Airworthiness Directive requiring the immediate replacement of zinc-plated crankshaft gear bolts to prevent similar failures.

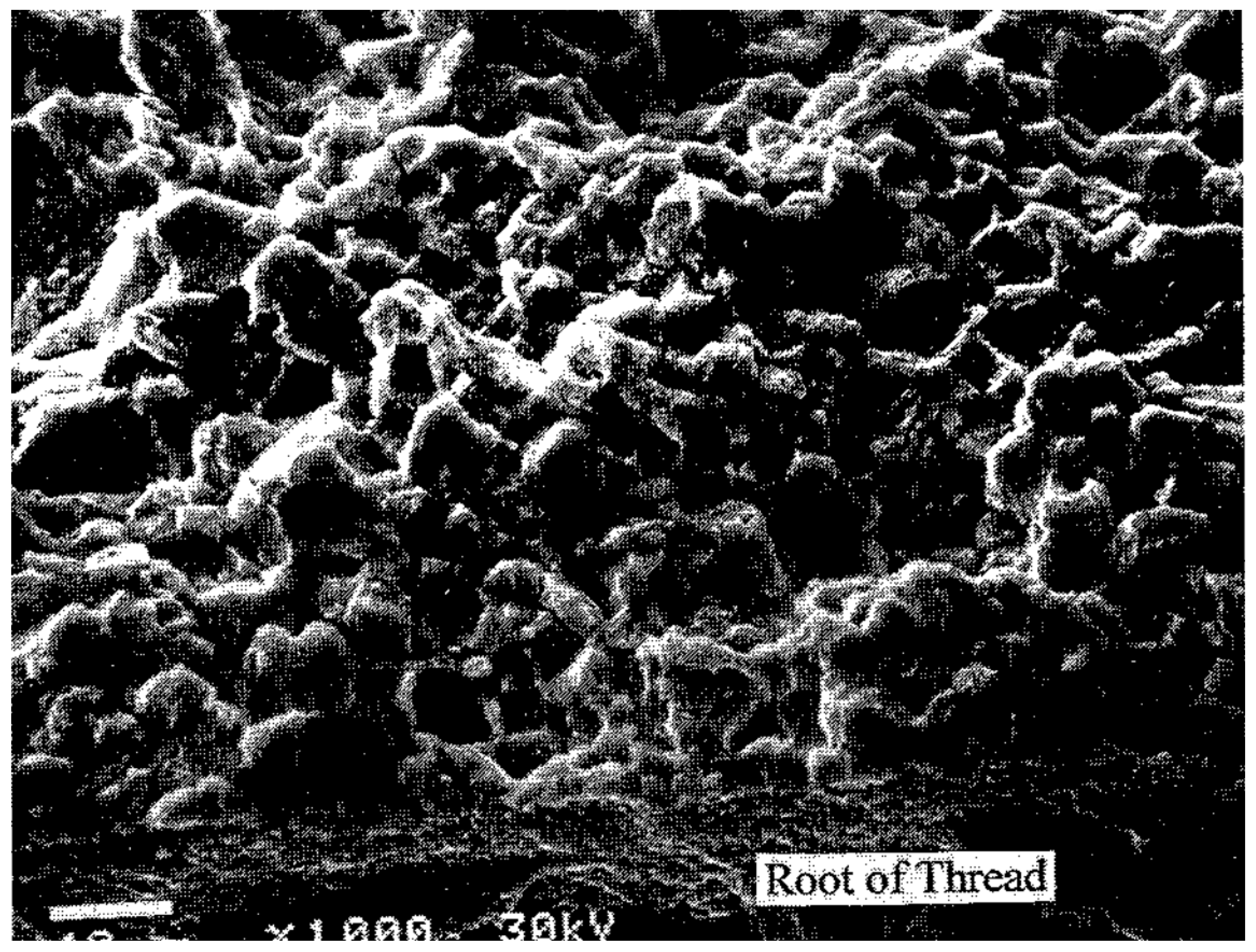

3.4. Failure of the Piper PA-32R-301 (MIA02LA108)

On June 7, 2002, a Piper PA-32R-301 suffered a catastrophic engine failure during a training flight near Key Field in Meridian, Mississippi. Operated by a private pilot, the aircraft experienced a sudden engine failure at 500-600 feet altitude, resulting in an emergency landing attempt. Unfortunately, the aircraft impacted a field and trees, overturning upon landing. The pilot sustained severe injuries, and the aircraft was destroyed.

Figure 15 illustrates the wreckage following its recovery.

Subsequent investigation identified the failure of the crankshaft gear bolt (part number STD-2209) in the Lycoming IO-540-K1G5 engine (Serial No: L-25968-48A) as the primary cause. Examination revealed the bolt fractured between the second and fifth threads from the shank (

Figure 16), with secondary cracks found at the 12th and 13th threads. The fracture was attributed to hydrogen embrittlement—a failure mechanism exacerbated by inadequate post-plating baking after zinc electroplating. This process allowed hydrogen to remain trapped, leading to material weakening and intergranular cracking.

A thorough investigation of the crankshaft gear bolt failure by the Lycoming Materials Laboratory identified hydrogen embrittlement as the root cause. The bolt fractured primarily between the second and fifth threads from the shank, with additional cracks extending through the twelfth and thirteenth threads. These fractures exhibited intergranular separation, a distinct characteristic of hydrogen-assisted cracking.

Figure 17 provides a detailed SEM image, highlighting the intergranular separation indicative of hydrogen embrittlement.

The hydrogen embrittlement was traced to the zinc electroplating process, which introduced hydrogen into the bolt material. Despite conforming to specifications for hardness and coating thickness, the inadequate post-plating dehydrogenation treatments allowed residual hydrogen to remain, compromising the bolt’s structural integrity. This residual hydrogen accumulated at the grain boundaries under operational stresses, leading to the initiation and propagation of cracks.

The bolt failure set off a cascade of damage, including rotational fatigue, that caused secondary damage to the gear and dowel components. This failure ultimately resulted in the separation of the crankshaft gear, leading to a complete loss of engine power. The investigation concluded that the manufacturing process lacked sufficient quality control, specifically in post-plating procedures aimed at eliminating hydrogen.

This incident underscores the critical need for stringent post-plating baking heat treatments to effectively remove hydrogen from plated components. Furthermore, it highlights the necessity of regular inspections for early detection of material degradation, particularly in components subjected to cyclic loading. The findings emphasize the importance of implementing robust quality assurance protocols and industry-standard practices for hydrogen mitigation in aviation manufacturing.

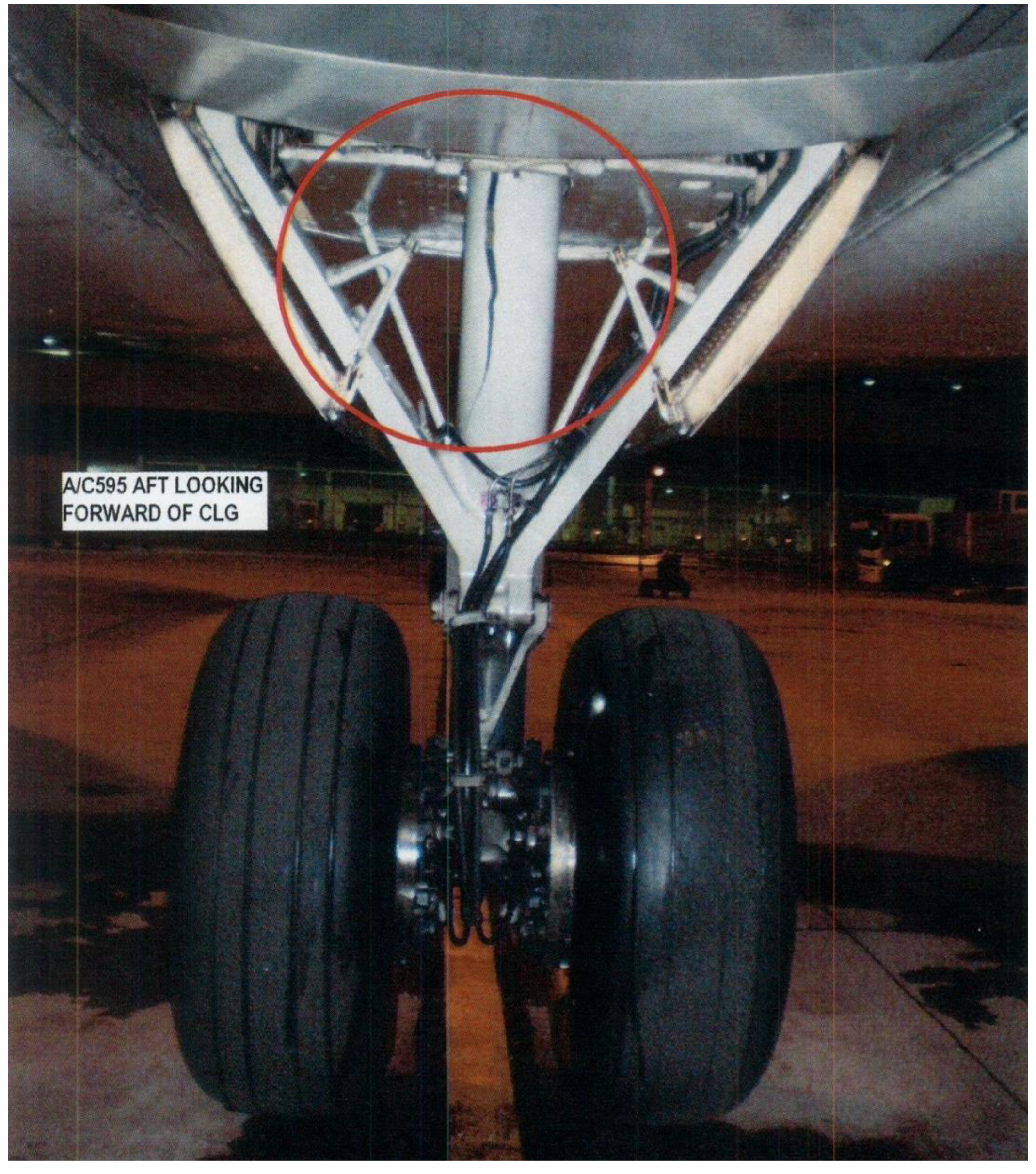

3.5. Failure of the Center Landing Gear on FedEx MD-11 (ENG08IA025)

On April 27, 2008, during a routine pre-flight inspection at Singapore Changi Airport (SIN), hydraulic fluid was discovered near the center landing gear (CLG) strut of a FedEx MD-11 aircraft. A detailed examination revealed a 33-inch longitudinal crack on the aft side of the CLG strut cylinder. The crack’s presence prompted the removal of the CLG strut for teardown and analysis, which was carried out at the Boeing Southern California Materials Laboratory. The strut had accumulated 5,058 cycles since its last installation on February 22, 2001, with a total lifetime of 9,379 cycles.

Figure 18 shows the initial findings, highlighting the visible crack.

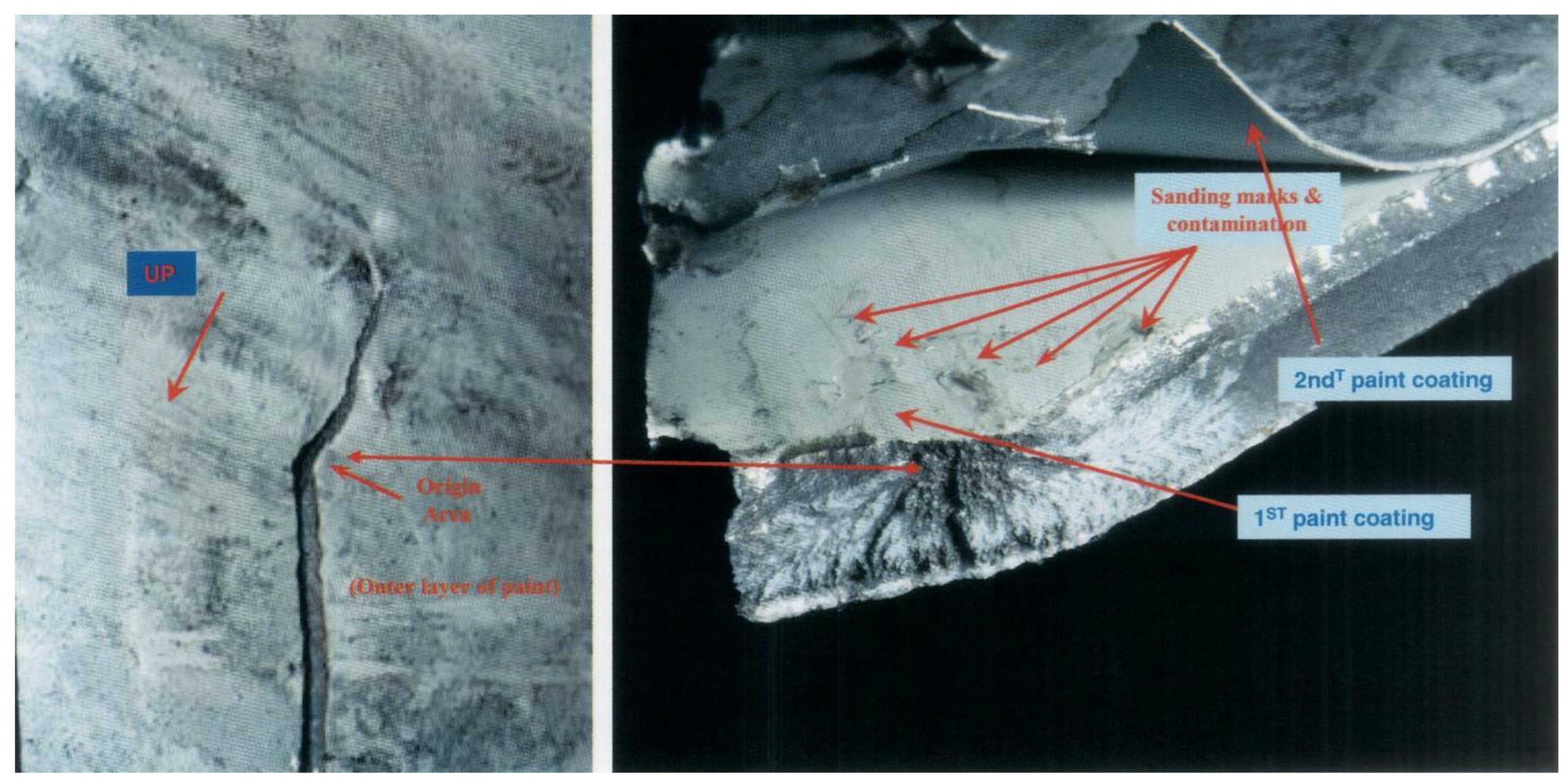

Metallurgical analysis confirmed that the failure was due to intergranular cracking, which originated from surface contamination introduced during a prior maintenance procedure. The contamination resulted from improper cleaning before the application of paint. Residual chemicals from paint removal solutions contributed to hydrogen embrittlement, causing the intergranular cracking to propagate through the cylinder wall and compromise its structural integrity. A cross-sectional view (

Figure 19) of the fracture origin highlights the intergranular cracking and subsequent progression.

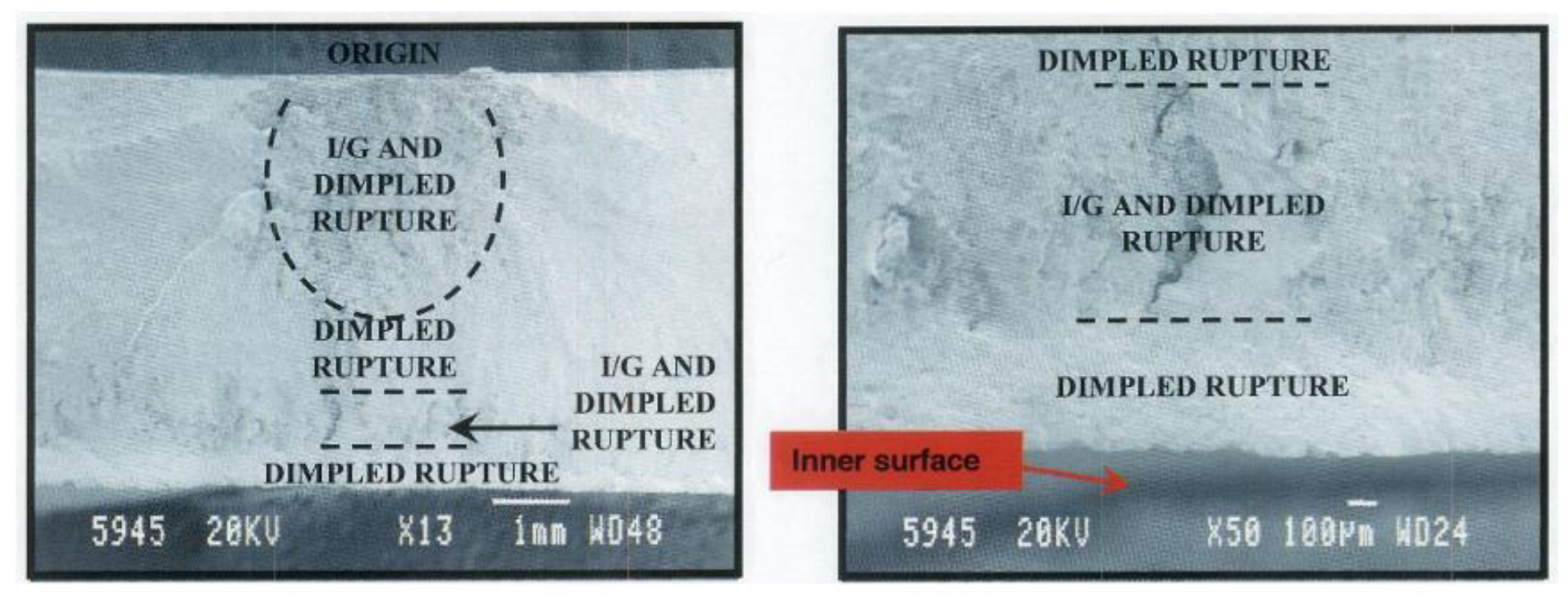

Teardown observations indicated high residual stresses in the material. While cutting the cylinder, loud “bangs” were reported, revealing further crack propagation due to residual stresses. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) analysis (

Figure 20) provided evidence of mixed-mode failure. The fracture surface exhibited intergranular separation at the origin and dimpled rupture in other areas, which is characteristic of ductile overload failure.

Further inspection revealed sanding and paint repair marks in the region of failure. Surface sanding likely introduced contamination, and the hydrogen absorbed during the cleaning and painting process contributed to the intergranular cracking. The primary fracture was traced to this contaminated region, approximately 18.2 inches from the bottom of the cylinder.

This failure underscores the critical importance of proper surface treatments and material handling during maintenance. The hydrogen embrittlement was caused by contamination from cleaning agents, combined with operational stresses.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

HE presents a unique challenge in aviation, particularly in high-strength components that operate under cyclic stress and are exposed to environmental hydrogen. This review, grounded in specific incident analyses, underscores the critical need for enhanced material science solutions, improved manufacturing protocols, and proactive maintenance strategies.

To enhance safety and operational reliability in the aviation industry, it is essential to focus on the development of hydrogen-resistant alloys specifically designed for aerospace applications. These advanced materials, such as titanium and steel alloys with superior hydrogen tolerance, are crucial for reducing susceptibility to embrittlement. Innovations like nanotechnology-based coatings provide promising pathways for improving resistance to hydrogen diffusion, ensuring the durability of components exposed to high-stress conditions.

Predictive modeling and simulation technologies, such as finite element analysis (FEA) and multi-scale modeling, have proven to be invaluable tools in understanding and mitigating hydrogen embrittlement. These techniques offer a deeper insight into hydrogen diffusion patterns and their impact on material microstructures, enabling the design of next-generation aircraft components that are both lightweight and resistant to HE.

Incident reports analyzed in this study highlight the importance of stringent post-manufacturing treatments, such as baking after electroplating, to eliminate residual hydrogen and mitigate risks. The relatively small number of Airworthiness Directives (ADs) related to hydrogen embrittlement—12 out of 167,751 total ADs issued by the FAA—underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and targeted interventions. These cases, while limited in number, emphasize the disproportionate impact that hydrogen embrittlement can have on aviation safety.

Looking forward, collaboration among materials scientists, aerospace engineers, and regulatory authorities is essential for addressing HE challenges. Additive manufacturing, real-time monitoring, and hydrogen-resistant materials represent promising avenues for future research and development. As the aviation industry transitions towards hydrogen-based propulsion systems, robust storage, and transportation solutions must also be developed to prevent embrittlement risks.

In conclusion, the aviation sector must embrace a multidisciplinary approach to combat hydrogen embrittlement, combining advanced materials, state-of-the-art detection tools, and robust regulatory frameworks. These efforts will not only safeguard against HE-induced failures but also support the shift toward sustainable and resilient aviation technologies in the decades ahead.