1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

Nanoporous membranes consist of a condensed organic or inorganic bulk phase (referred to as the matrix) containing a porous structure with pore diameters typically quantified in nanometers (usually 100 nm or smaller) [

1]. These membranes occur naturally, as in cell membranes, skin, activated carbon, and zeolites, but artificial nanoporous materials are also extensively manufactured and employed in diverse chemical, biological, medical, and engineering applications. These include the development of gas and energy storage systems and the design of sensing nanoelectronics devices [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In nearly all such applications, a theoretical understanding of energy and particle transport through nanoporous membranes is critical [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, modeling energy and mass transfer across these membranes is fundamental for understanding the physiology of living cells and drug delivery across skin [

22,

23,

24].

In textbooks and scientific literature, macroscopic models of dissipative processes, whether for particle transport or heat conduction, are predominantly based on classical diffusion theory [

25,

26]. However, experimental results often deviate from these classical models, revealing wave-like or anomalous diffusion effects [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Over the past few decades, numerous generalized models have been developed to account for such experimentally observed anomalies.

Anomalous diffusion dynamics, characterized by a non-linear growth of the mean-squared displacement (MSD), are increasingly observed in biological, soft, and active matter systems through single-particle tracking (SPT) techniques [

27,

28,

29,

30]. These techniques reveal power-law MSD dependencies, with subdiffusion occurring for anomalous exponents in the range (0,1) and superdiffusion for exponents in the range (1,2) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Anomalous diffusion can arise from the tortuous structure of the embedding space, resulting in fractal step-time distributions. Microscopically derived subdiffusive and superdiffusive fractional models of dissipative processes link fractional kinetics of mass or energy carriers with memory effects in the system’s dynamics across phase space [

43,

44]. This phenomenon, often termed kinetic memory, presents challenges as such models typically assume infinite propagation speeds, violating causality [

45].

A potential resolution to the causality issue involves introducing a phase lag between the flux and the gradient of the scalar physical field (e.g., particle concentration or temperature). This approach, as demonstrated in the Cattaneo–Vernotte generalization of heat conduction theory, attributes the phase lag to the inertia of moving particles, effectively incorporating inertial memory into transport models [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

In this paper, we adopt two types of inertial memory kernels—an exponentially decaying kernel and a power-law decaying kernel described by the Mittag-Leffler function [

53]—to derive causal models of particle transport. We analyze how inertial memory affects molecular transport across porous membranes. For simplicity, all derivations are conducted in a one-dimensional framework.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the causality limitations of classical and non-inertial anomalous diffusive theories.

Section 3 derives generalized transport equations incorporating inertial memory properties of the medium, demonstrating that these models resolve causality issues in non-inertial transport theories.

Section 4 presents spectral functions for concentration distribution within the porous membrane, flux at the non-excited membrane side, and cumulative particle delivery.

Section 5 discusses the effects of inertial memory on these spectral functions by comparing them with classical Fickian models for porous media and analyzes the evolution of cumulative particle delivery through thin membranes. Finally,

Section 6 provides the key conclusions.

2. Background

In the context of classical theory, the well-known model of transport of particle, mass or energy reads [

25,

26]

Symbols

and

signify the scalar field (particle concentration, temperature or mass density) and flux vector, respectively. With symbols D and k (

) are denoted diffusion constant and conductivity of a medium, respectively and γ is the capacity of the media (for heat transfer it is heat capacity and for particle transport γ=Vp/V is the dimensionless volume capacity where Vp is the total volume of free space (pores) between medium constituent, V is the total volume of the medium across with particles move [

54]).

The Eq2 (Fick’s Second Law for particle transport, or diffusion equation in heat transfer) is parabolic partial differential equation. As is well known from the theory of parabolic differential equation, the solution of Eq 2 in semi-infinite domain for impulse excitation is given by the following expression [

39]:

Equation (3) shows that the disturbance produced on the sample’s surface appears at the same time at an infinite distance from the source of the disturbance, suggesting that this theory predicts an infinite speed of disturbance propagation [

45,

46], and consequently, this theory is not causal.

Let’s now consider a widespread fractional transport theory [

21,

38,

39] which is derived from macroscopic approach. It describes transfer of mass or energy by constitutive relation (1) and the fractional partial differential equation:

A closed-form solution of Eq4 for the propagation of a disturbance through a semi-infinite medium produced by a pulse excitation on the sample surface can be found in terms of the Fox function [

39]. Employing some standard theorems of the Fox function, the asymptotic stretched Gaussian is obtained:

which is valid for

.

Eq. (5) shows that the rate of mass (or energy) changes produced by the change of concentration (or temperature) on the surface of a semi-infinite sample is lower than predicted by classical diffusion theory in each moment, explaining the anomalous diffusive effect. However, disturbance generated on the surface appears at the same moment at an infinite distance from the source of the disturbance. This means that this theory predicts an infinite propagation speed of the disturbance, like as in classical theory, and it is not causal.

Finally, we consider the Cattaneo-Vernotte transport model derived in heat conduction theory by combining the energy balance equation and time –delayed constitutive relation [

46,

51,

55,

56] :

where the time constant

is inertial relaxation time because the delayed time of flux

originates from the inertial properties of particles or energy carriers [

52]. It must be emphasized that although this time interval is sometimes connected to the mean collision time of the particles, it should not be associated with it. No general formula relates these two time constants yet [

57,

58].

One can obtain the following hyperbolic equation for transport of mass, concentration or energy disturbance, by replacing constitutive relation (6) in continuity equation:

The solution of Eq 7 for impulse excitation of mass disturbance and semi-infinite space is given by [

52]

if the relaxation time is non-zero and

In above equations (Eqs 8, 9), the speed of propagation of initial disturbance is denoted with symbol v:

and K1 is modified Bessel function.

Physical meaning of the condition given by Eq 9 is that the time, needed for initial disturbance to reach the point x in space, is exactly and before that the initial disturbance is not felt in the point x at all. This means that the hyperbolic theory is causal, because it predicts the final velocity of disturbance propagation.

Considering that this model was derived assuming a time-delayed constitutive relationship, it can be concluded that the causality of the transport model is related to the time-delayed flux. The time-delayed constitutive relation, given by Eq (6), states that flux in the given space point and the given moment depends not only on the concentration gradient in the same point and same moment but also on the concentration gradient in all previous moments due to inertia of carriers of mass or energy. This idea of introducing the inertial memory of substantial media for description the time-delayed fluxes comes from the electrodynamics of substantial media and especially from the theory of elasticity of non–linear materials and it will be presented in more detail in the next section (see References [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]).

3. Delayed Flux and Inertial Fading Memory Paradigm: Derivation of the Causal Models of Particle Transport

Following the idea of inertial memory [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63] in the non-local flux model, the flux

is related to the previous history of the particle concentration

through a relaxation function

as

The kernel describes the inertial memory of the material. Its role is in the distribution of the relevance of concentration gradients at different past moments.

If it is assumed that the Dirac delta function can describe the memory kernel:

the Fick’s first law for porous media is obtained (Eq1). In other words, the Fick’s constitutive relation (The First Fick’s Law) corresponds to zero memory materials and further non-causal parabolic transport theory with infinite propagation speed of disturbance. On the other hand, if it is assumed that the memory kernel is constant:

the case of media with infinite memory is obtained and further undamped wave propagation theory [

57]

where

is constant. This case corresponds to the causal assumption about the finite propagation speed of disturbance, which is equal to

but is physically objectable.

The physical sense says that the concentration gradients contribute to flux

, but their relevance diminishes as we go further into the past. This reason leads to the “fading memory” paradigm. Namely, in the theory of non-linear materials, this paradigm was introduced to express the idea that the recent history of deformation should have a more significant effect than the remote one on the present value of the stress [

57,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

In the frame of this paradigm, with a suitable choice for memory kernel, various constitutive relations can be obtained. Two of them, together with the continuity equation (conservation laws), yield transport theories that don’t show a lack of causality, i.e., they include finite propagation speed of disturbance. Both kernel and corresponding transport theory are derived in the following.

Application of the operator

to the memory constitutive relation (Eq 11) yields

By using Leibniz’s formula for the differentiation of an integral, Eq.15 becomes

Integral at the right side of Eq 16 can be neglected if one considers that the system is non-equilibrium but not far from the equilibrium state, and the linear approximation of constitutive relation becomes the Cattaneo-Vernotte equation (Eq.7). Then the memory kernel relaxation function can be obtained from the following differential equation:

Solving this differential equation (Eq 17), an exponentially decreasing relaxation function is obtained:

with

To summarize, in the linear approximation of the non-equilibrium transport process near the equilibrium state, the memory kernel given by Eq.15-16 yields a constitutive relation suggested by Cattaneo and Vernotte (Eq.6), which, together with the continuity equation (conservation law), give hyperbolic damped wave model of dissipative process ( Eq 7) with finite speed of propagation .

Let us derive the fractional causal model of particle transport across porous media. Fractional calculus [

64,

65] was introduced in the theory of dissipative processes to explain the non-linear relation between the mean square displacement of the particles and time of propagation, the so-called anomalous diffusive effect [

39]. There are a few fractional models, and all of them consider the influence of the prehistory of the system movement on its evolution in phase space [

39,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]. In this sense, we talk about memory effects in fractional models, but only one fractional model can be derived based on the inertial memory relaxation function and the fading memory paradigm.

Thus, we start with the following fractional derivative (see

Appendix A)

where

is dimensionless fractional exponent, and

is the Euler Gamma function.

The right-hand side may now be manipulated by inverting the order of the integrals and changing variables with

to obtain

We integrate the innermost integral once by parts

where, on the right-hand side, we have already taken the temporal derivative on the integral of the first summand (Leibniz’s formula), and we have changed the variable

to t-y in the integrals of the second summand. We can now recognize in the first summand of the right-hand side of equation (22) a fractional integral of order

. To proceed, it is now convenient to apply Leibniz’s formula to differentiate the integral in the second summand. Then we integrate the resulting expression once by parts, where we use the definition of fractional differ-integrals where applicable:

As in the first case, for a non-equilibrium system near thermodynamic equilibrium, integral at the right side of Eq 23 can be neglected, and the relaxation function can be obtained from the following differential equation:

with

The application of Laplace transform to Eq24 yields (see

Appendix B)

where s is complex frequency.

The inverse Laplace transform of Eq (26) is a generalized Mittag-Leffler function [

72]:

which is a fading function in accordance with power law for a long time,

.

In media where relaxation flux follows such long time power law, constitutive relation becomes

The relation (28) together with the continuity equation, i.e., conservation law, yields the following fractional transport model

where D is fractional diffusivity of a medium.

By analyzing Eq. 29, it has been shown that such a transport model is causal, i.e., it includes the finite propagation speed of disturbance

[

71].

In this paper, all further considerations of particle transport across the porous membrane are based on the transport models given by Eq (2)-classical Fick’s transport with zero memory, Eq (7)-exponentially fading memory, and Eq (29)-power-law fading memory, with corresponding constitutive relations, Eq.1, Eq.6, and Eq.28, respectively.

4. Particle Transport Across the Porous Membrane- Spectral Functions

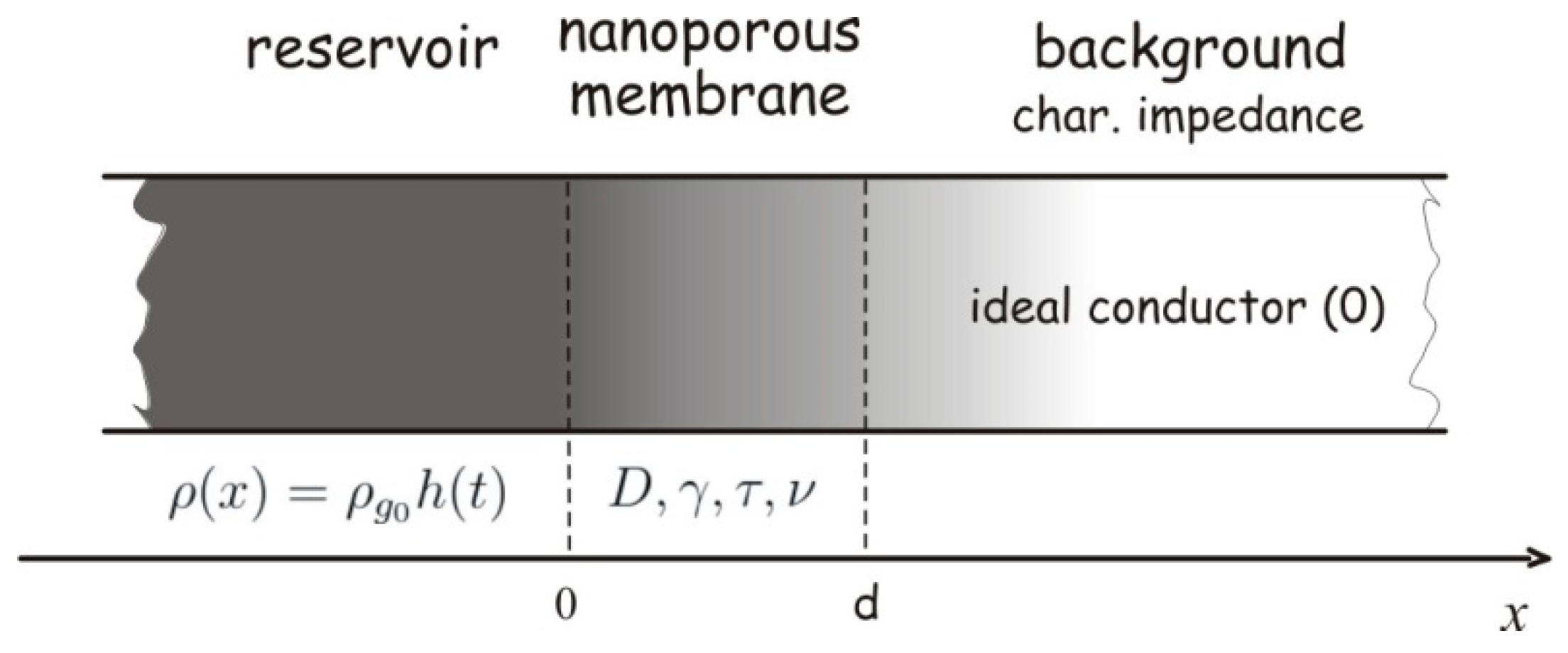

We are observing a porous membrane of thickness d, into which a uniform beam of molecules enters through its lateral surface, so it is convenient to consider the problem in a one-dimensional approximation. The geometry of the problem is illustrated in Fig.1.

Based on the considerations given in

Section 3, the transport of small molecules through the porous membrane shown in

Figure 1 can be described using three models: the classical Fick’s model or zero-memory model (Eqs 1,2) and two causal models that take into account the finite propagation speed of the concentration perturbation or fading memory models (Eqs 6, 7 exponentially fading memory, and Eqs 28, 29 power law fading memory).

We assume that the membrane at the point

x=0 comes into contact with a time-varying reservoir of molecules, so the boundary condition at this point can be written as follows:

where

is the initial concentration of molecules in the reservoir, which is constant, and

is the Heaviside step function.

At the point

x=d, there is an ideally conductive medium, i.e., a medium that has a much lower characteristic impedance than the membrane, and boundary condition in this point becomes [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

73,

74,

75]:

In many applications of nanoporous membranes, it is necessary to consider the cumulative amount of particles delivered from membrane [

12]:

where

and P is the area of the cross-section of the membrane.

Given that all three models (Eqs.1-2, classical model, Eqs. 6-7 exponentially fading memory model, and Eqs28-29 power-law fading memory model, with boundary conditions given by Eqs 30-31), as well as Eq (32), from a mathematical point of view describe the transport of molecules through the membrane in a linear approximation, the problem of molecular transport across nanoporous membrane can be solved by applying integral transformations. In this work, the spectral functions of the concentration profile and fluxes were obtained using the Laplace transform (see

Appendix B)

.

By applying the Laplace transformation to the equations of the transport model, the theoretical model of the transport of molecules through the membrane is described by a system of ordinary differential equations in the complex domain (the same form for all three transport models):

for

, where

is complex frequency and

.

In Eqs. 34, 35, with and are denoted the complex coefficient of propagation of concentration disturbance and characteristic impedance of the membrane, respectively. These complex parameters for all three models are given below:

Exponentially fading memory

It is interesting to note that, using the analogy with wave propagation, the real part of

can be related to the diffusion length of disturbance (inverse diffusion length), and the imaginary part of

is inverse proportional wavelength [

44].

By applying the Laplace transform to the boundary conditions given in Eqs 30, 31 the following complex boundary conditions are obtained:

The general solution of the system of Eqs 34, 35 can be written in the form of a sum of exponential functions:

where complex coefficients A

1 and A

2 depend on boundary conditions.

By substituting solutions given by Eqs 41, 42 into boundary conditions (Eqs 39, 40), the spectral function of the concentration and flux profiles are obtained:

By using equation (44), the flux on the unexcited side of the membrane becomes:

The spectral function of normalized cumulative amounts of molecules that are delivered through the membrane is defined by applying the Laplace transform to Eq32, 33 and by using Eq45

In most nanoporous materials applications, these membranes are very thin, in an order of micrometers or less. In that case, the spectral functions of particle flux at non-excited side of membrane (Eq 45) could be simplified as well as the model of cumulative amount of particles delivered from membrane.

By using the development functions

in power series [

43]:

and taking only the first term of the developments given by Eq 44, as dominant for thin samples, we obtain the following approximated spectral functions of flux for thin membrane:

Normalized cumulative amount of particles delivered from membrane, in that case, becomes:

where parameters

and

are given by Eq 36 for the classical model, Eq. 37 for the exponentially fading memory model, and Eq. 38 for the power-law fading memory model.

By substituting Eq 36 in Eqs 48-49, the spectral functions back-side flux and cumulative amount of particles delivered from thin membrane, predicted by classical model, are obtained:

where

By substituting Eq 37 in Eqs 48-49, the spectral functions of flux and cumulative amount of particles predicted by exponentially fading inertial memory model are obtained:

where

a is given by Eq 52 and

By substituting Eq 38 in Eqs 48-49, the spectral functions predicted by power- law fading inertial memory model are obtained:

5. Analyzes and Discussion

This section analyzes the influence of material’s inertial memory on the spectral function of the profile of concentration and spectral function of back-side flux. After that, the evolutions of cumulative amounts of delivered particles are calculated to analyze the effect of inertial memory on the evolution of cumulative amount of delivered particles.

5.1. Inertial Memory Effect on Spectral Function of the Profile of Concentration and Back-Side Flux

For ease of discussion, the following normalizations are introduced: , , , , , , , .

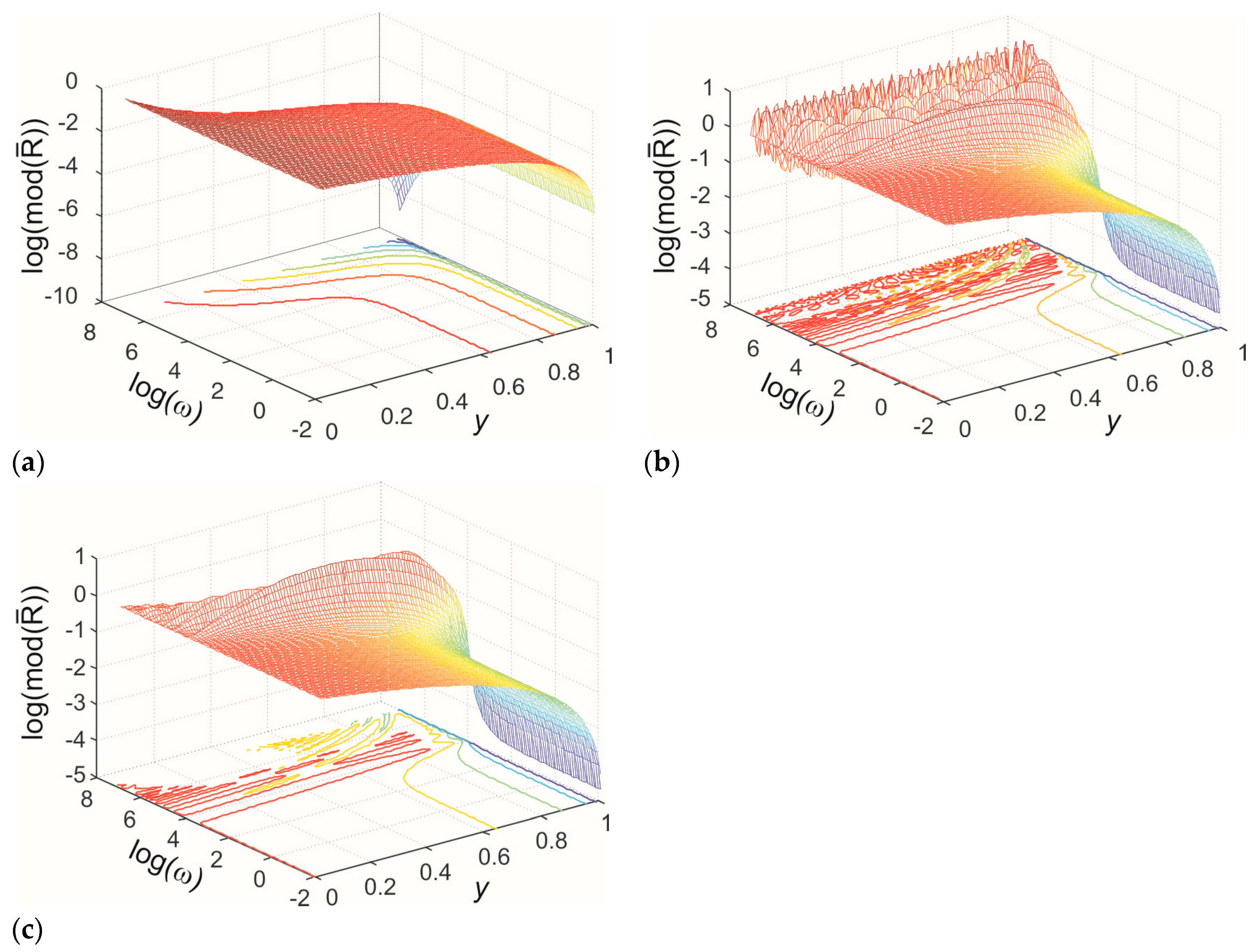

The spectral functions of the normalized profile of concentration are illustrated in

Figure 2 for all three models. The parameters used in calculations are:

,

,

.

The classical model (

Figure 2a) predicts a monotonically decreasing concentration profile and monotonically decreasing harmonic amplitudes, where amplitudes decrease as the harmonic frequency increases. In contrast, the memory models (

Figure 2b,c) predict a monotonically decreasing concentration profile for lower harmonics but exhibit oscillatory profiles for higher harmonics. Additionally, these models predict oscillatory changes in the amplitudes of higher harmonics. This behavior arises from the wave-like nature of concentration disturbance propagation introduced by the inertial memory models.

For harmonics with frequencies higher than

, where

is the propagation speed (

for exponentially fading memory and

for power-law fading memory) [

51,

71], the wavelength of the concentration disturbance becomes smaller than the sample dimensions. This results in the formation of standing waves for harmonics where the integer product of half the wavelength equals the membrane dimensions. The amplitudes of these waves decrease with increasing harmonic frequency due to increased damping at higher frequencies. For lower harmonics, where the wavelength is much larger than the membrane dimensions, wave effects do not occur. In these cases, the amplitudes of lower harmonics in memory models are higher because damping is minimal for low-frequency harmonics. These observations indicate that inertial memory creates two distinct regimes of concentration disturbance propagation: a diffusive regime at low harmonics and a damped wave regime at high excitation harmonics,

.

Comparing

Figure 2a,b reveals that the amplitudes of standing waves in the exponentially fading memory model are significantly higher than those predicted by the power-law fading memory model. Furthermore, in the exponential fading memory model, the decline in amplitudes diminishes for very high harmonics, contrary to the power-law fading memory model, which predicts increased amplitude attenuation with rising harmonic frequency. This difference can be explained by analyzing the real parts of the propagation coefficients

and

(Eqs. 37, 38). In the exponential fading memory model, the real part of the wave vector increases with frequency, approaching an asymptotic value that represents the maximum damping and corresponds to the minimum diffusion length of the concentration disturbance. Conversely, the power-law fading memory model predicts a continuous increase in damping with frequency, without a minimum diffusion length for the propagation of concentration disturbances.

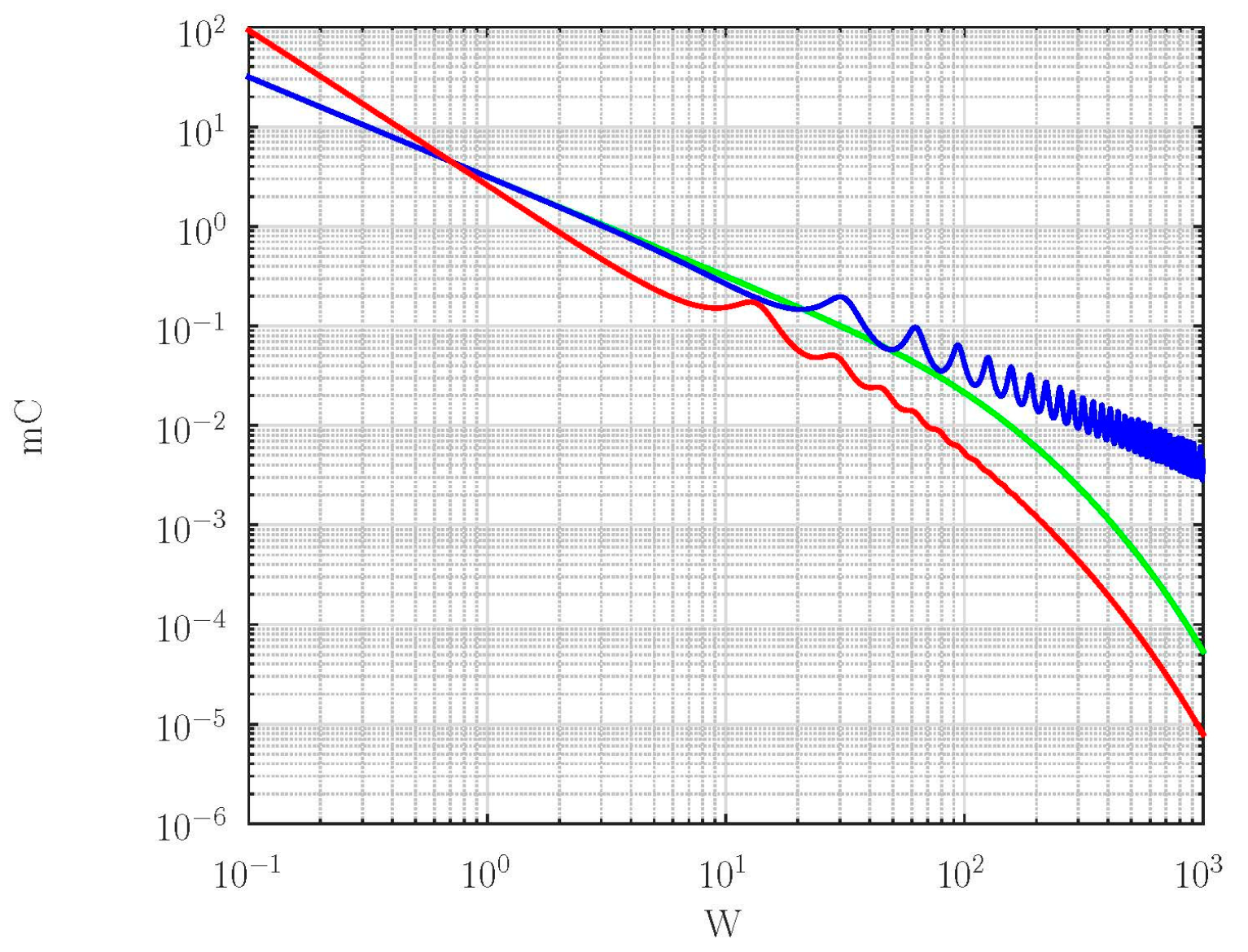

Figure 3 shows the spectral function of back-side flux calculated by the classical model (green line), the exponentially fading memory model (blue line), and the power law fading memory model (red line).

As shown in

Figure 3a, the inertial memory models predict oscillatory changes in the output cumulative flux at high frequencies, higher than

(blue and red lines,

Figure 3). Such behavior of spectral functions predicted by memory models is in accordance with the existence of two different regimes: diffusion at low frequencies and consequently in the long-time limit and damped wave regime at high frequencies (in the short-time limit). Due to the wave regime of particle propagation, one can expect cumulative amounts of molecules that pass across the membrane (proportional to time integral of back-side flux, Eq 42) oscillatory approach to its stationary value (with overshoots) and with a larger time constant [

76].

At high frequencies, the envelope distance of the exponentially fading memory model (blue line,

Figure 3) is larger than predicted by the power law fading memory model (red line,

Figure 3a), meaning that anomalous diffusive effects, described by fractional exponent

, could influence to reduce the overshoots in the short-time domain [

76]. Besides, power-law fading memory shifts the position of extremes toward lower frequencies because the propagation speed increases if there is an anomalous diffusive effect.

At low frequencies, the exponentially fading memory model and classical model predict the same rate of decreasing of the amplitude of back-side flux (monotonically decreasing function of the same slope). In contrast, the power-law fading memory model predicts the monotonically decreasing curve of a higher slope indicating the power-law fading memory model predicts super diffusion of particles disturbance at low harmonics.

Based on the analysis of the spectral functions of the concentration profile and the back-side flux, the following conclusions can be drawn. Inertial memory, either power law fading memory or exponential fading memory, cause the appearance of a damped wave regime of concentration disturbance propagation for harmonics whose frequency is . The wave regime affects the occurrence of oscillatory changes of the spectral function of the back-side flux at high frequencies. However, the decay slope of the envelope of oscillatory changes, predicted by the power-law and exponentially fading memory models are very different. The slope of the envelope of oscillatory changes of the back-side flux predicted by the exponentially fading memory model decreases significantly slower than the slope of the envelope predicted by the power-law fading memory model. In addition, power-law fading memory model and exponentially fading memory model predict completely different slopes of the low-frequency part of the back-side flux spectral function. The slope predicted by the exponentially fading memory model is smaller and coincides with the predictions of the classical model. The slope predicted by the power law fading memory depends on the fractional exponent . When this exponent is equal to unity, it can be expected that both memory models predict the same spectral function of the back-side flux, because in this case the coefficient of propagation and the characteristic impedance for both models coincide. However, as decreases toward zero, the difference in spectral functions predicted by these two memory models becomes increasingly large over the entire frequency range. The biggest difference can be expected for the case when . Based on this, it can be expected that these two memory models predict significantly different cumulative amounts of particles delivered through the membrane if .

5.2. The Influence of Inertial Memory to the Evolution of Cumulative Amounts of Particles Delivered from Thin Nanoporous Membranes

The analysis of spectral function from the previous section (Subsection 5.1) indicates that exponentially fading inertial memory primarily affects the high-frequency harmonics of the back-side flux. Consequently, its influence is noticeable only in the short-time cumulative amount of particles passing through the membrane. In contrast, power-law fading memory impacts the back-side flux across all frequencies, suggesting its influence on the cumulative particle transfer can manifest in both short- and long-time domains. For large fractional exponent (which value is close to unity), the effect of power-law fading memory is similar to that of exponential fading memory. However, for small fractional exponent (which values is near to zero), significant differences emerge between the two memory models regarding their impact on the cumulative amount of particles delivered through the nanoporous membrane.

To further analyze the influence of inertial memory, we derive expressions describing the evolution of the cumulative particle delivery through a thin nanoporous membrane as predicted by the classical model, the exponentially fading memory model, and the power-law fading memory model for

. By applying the inverse Laplace transform (see

Appendix B and [

77,

78]) to Eqs. (51), (54), and (57) for

, we obtain expressions that characterize the normalized cumulative amount of particles delivered over time for each model.

By finding the inverse Laplace transform (see

Appendix B and [

77,

78]) of the expressions Eq51, Eq54 and Eq-57 for

, expressions are obtained that describe the evolution of the normalized cumulative amount of delivered particles predicted by the classical model, exponentially fading and power law fading memory models, respectively:

where

,

, and

, and parameters

a and

b are defined by Eqs 52 and 55, respectively.

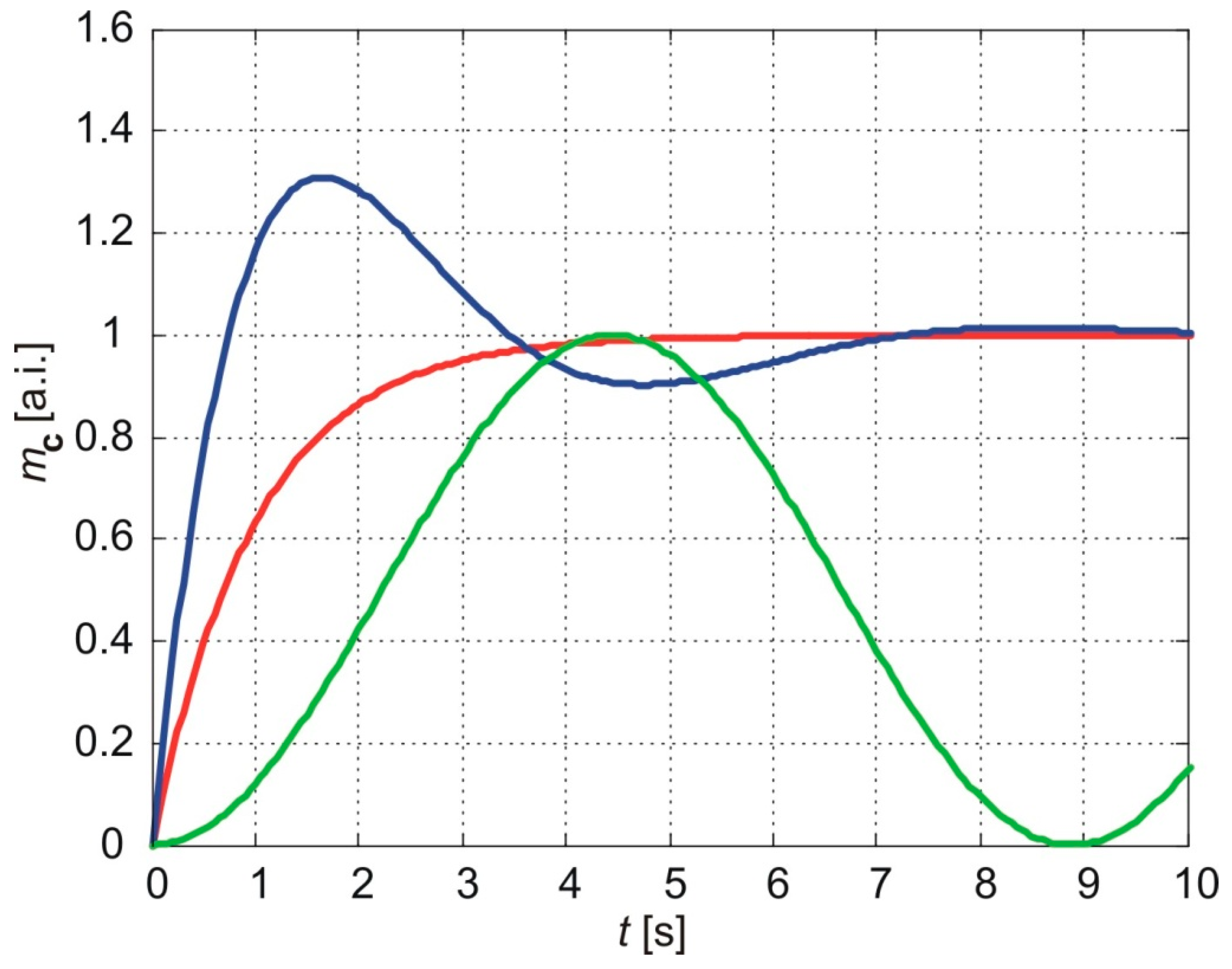

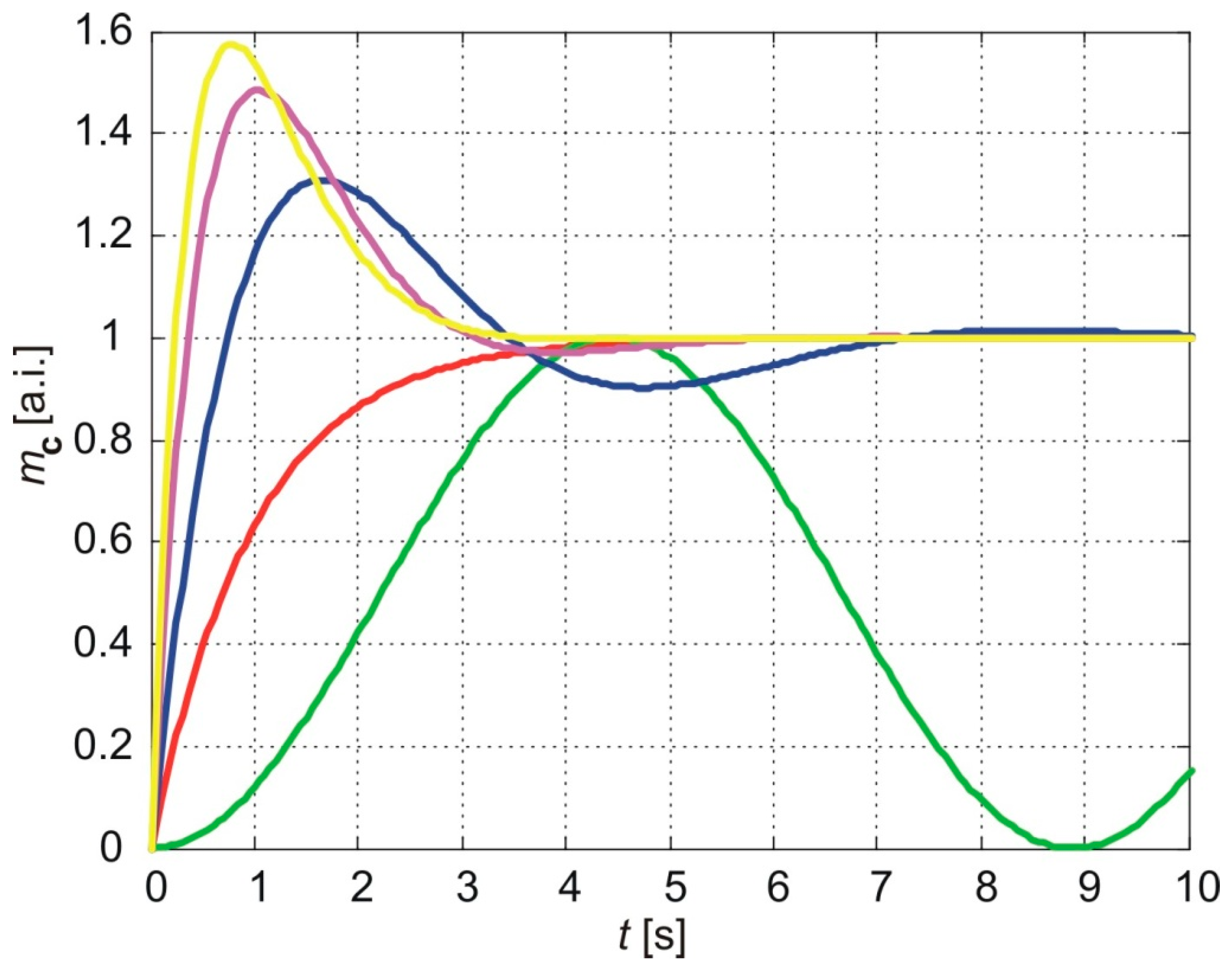

Figure 4 shows the normalized cumulative amount of particles that pass through the membrane depending on the time for

a=1,

b=.1 The red line shows the results of the classic model (Eq 58), the blue line shows the results of the exponential fading memory model (Eq 59) , and in green the results of the power law fading memory model when

(Eq. 60).

As shown in

Figure 4, the classical model predicts a monotonic increase in the cumulative amount of molecules delivered through the membrane, asymptotically approaching a maximum value equal to the steady-state cumulative amount. The time required to reach 90% of this steady value, referred to as the

settling time, depends on the parameter aaa, and thus on the diffusion coefficient and membrane thickness (Eq. 52).

In contrast, the exponentially fading memory model predicts a steep increase in the cumulative amount of molecules, reaching a maximum value larger than the steady-state value (overshoot), followed by an oscillatory approach to the steady-state value with decreasing amplitudes over time. The settling time for this model is longer than the corresponding settling time predicted by the classical model.

The power-law fading memory model, for , predicts oscillatory variations in the cumulative amount of molecules over time, with practically infinite settling time. The amplitudes of these oscillations converge to the steady-state value predicted by the classical model. Furthermore, the time required to reach the first maximum, referred to as the rising time, is larger for the power-law fading memory model compared to both the classical and exponentially fading memory models.

Interestingly, the results of the exponentially fading memory model (blue line) align with the results of the power-law fading memory model when . As the fractional exponent decreases, the behavior transitions to that predicted by the power-law fading memory model for (green line). A decrease in the fractional exponent increases both the rising and settling times but decreases the overshoot.

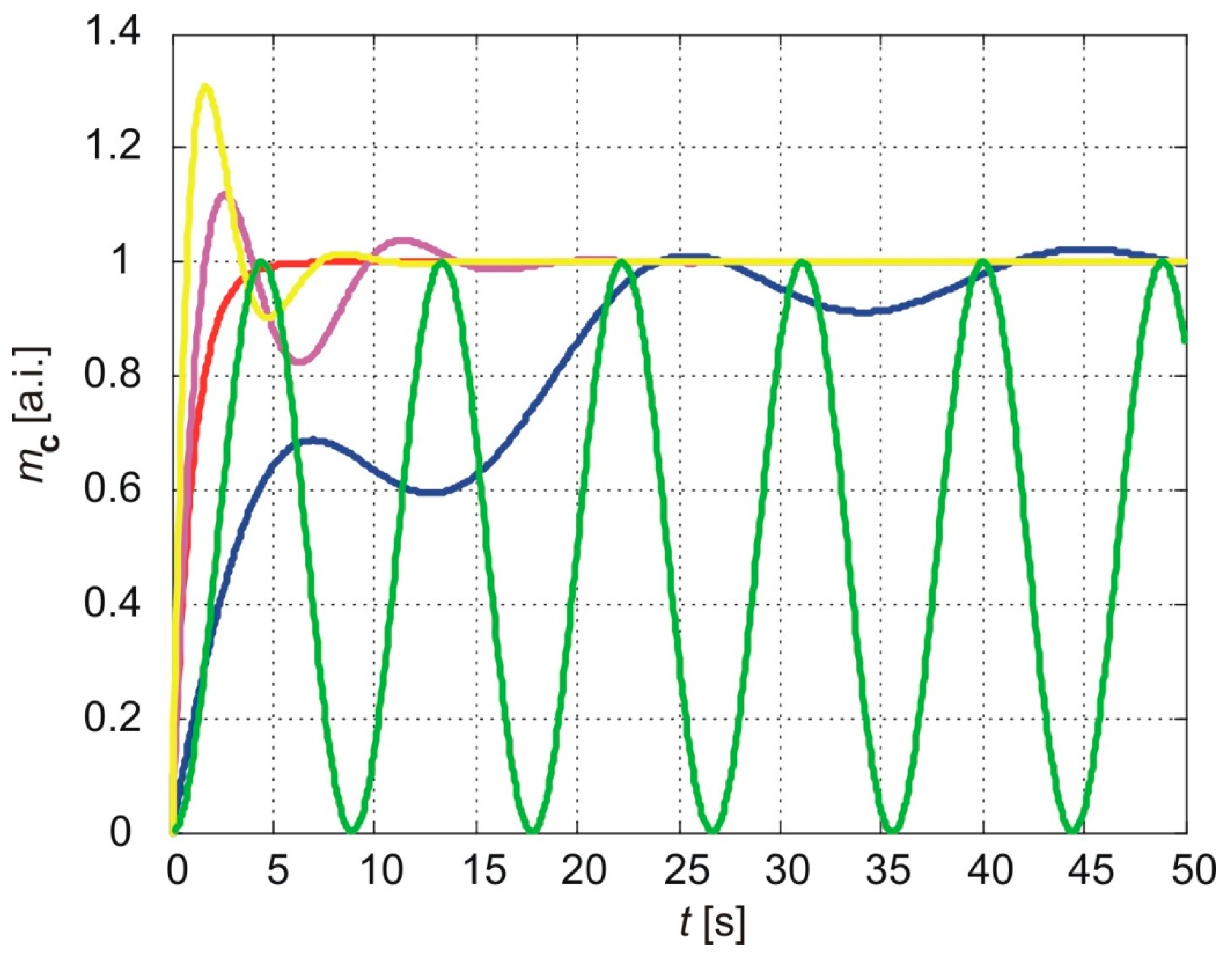

Figure 5 illustrates the normalized cumulative amounts of particles passing through the membrane over time. The parameters used for the calculations in all three models are

a=1 and three values of the parameter

b:

b=1,

b=2, and

b=3. The results of the exponentially fading memory model are shown with blue (

b=1), magenta (

b=2), and yellow (

b=3) lines. The red line represents the results of the classical model (Eq. 58), while the green line corresponds to the results of the power-law fading memory model for

(Eq. 60).

As shown in

Figure 5, the classical model and the power-law fading memory model for

are independent of the parameter

b. In contrast, the exponential fading memory model exhibits sensitivity to changes in

b. A decrease in

b reduces the overshoot of the cumulative amount of molecules relative to the steady-state value but increases the amplitude of oscillations, as well as the settling time and rising time.

The parameter b is related to the relaxation time τ, which reflects the phase lag between the flux and the concentration gradient, as shown in Eq. 55. An increase in τ corresponds to a decrease in b, implying that the exponential fading memory model predicts similar effects on the evolution of the cumulative amount of molecules for an increase in τ as for a decrease in the fractional exponent in the power-law fading memory model. Specifically, an increase in τ results in a longer settling time, a longer rising time (the time required to reach the first maximum of the cumulative amount of molecules), greater amplitude oscillations in the long-term behavior of the cumulative amount, and a decrease in the overshoot.

Figure 6 illustrates the normalized cumulative amounts of particles passing through the membrane over time, as predicted by all three models, with

a = 1 and

b=0.1 (blue line),

b=0.5 (magenta line), and

b=1 (yellow line). The results of the classical model (Eq. 58) are shown in red, while the results of the power-law fading memory model for

(Eq. 60) are represented by the green line.

As seen in

Figure 6, when the parameter

b is small, indicating a large relaxation time, the exponential fading memory model predicts an oscillatory increase in the cumulative amount of molecules. The first maximum is lower than the steady-state value, followed by a long-term oscillatory approach to the steady state (blue line,

Figure 6).

Comparing the short-time cumulative amounts of molecules predicted by the different models, it can be observed that for small

b, the exponential fading memory model shows closer agreement with the power-law fading memory model for

(compare the blue and green lines in

Figure 6). In contrast, for larger values of

b, the exponential fading memory model aligns more closely with the classical model (compare the yellow and magenta lines with the red line).

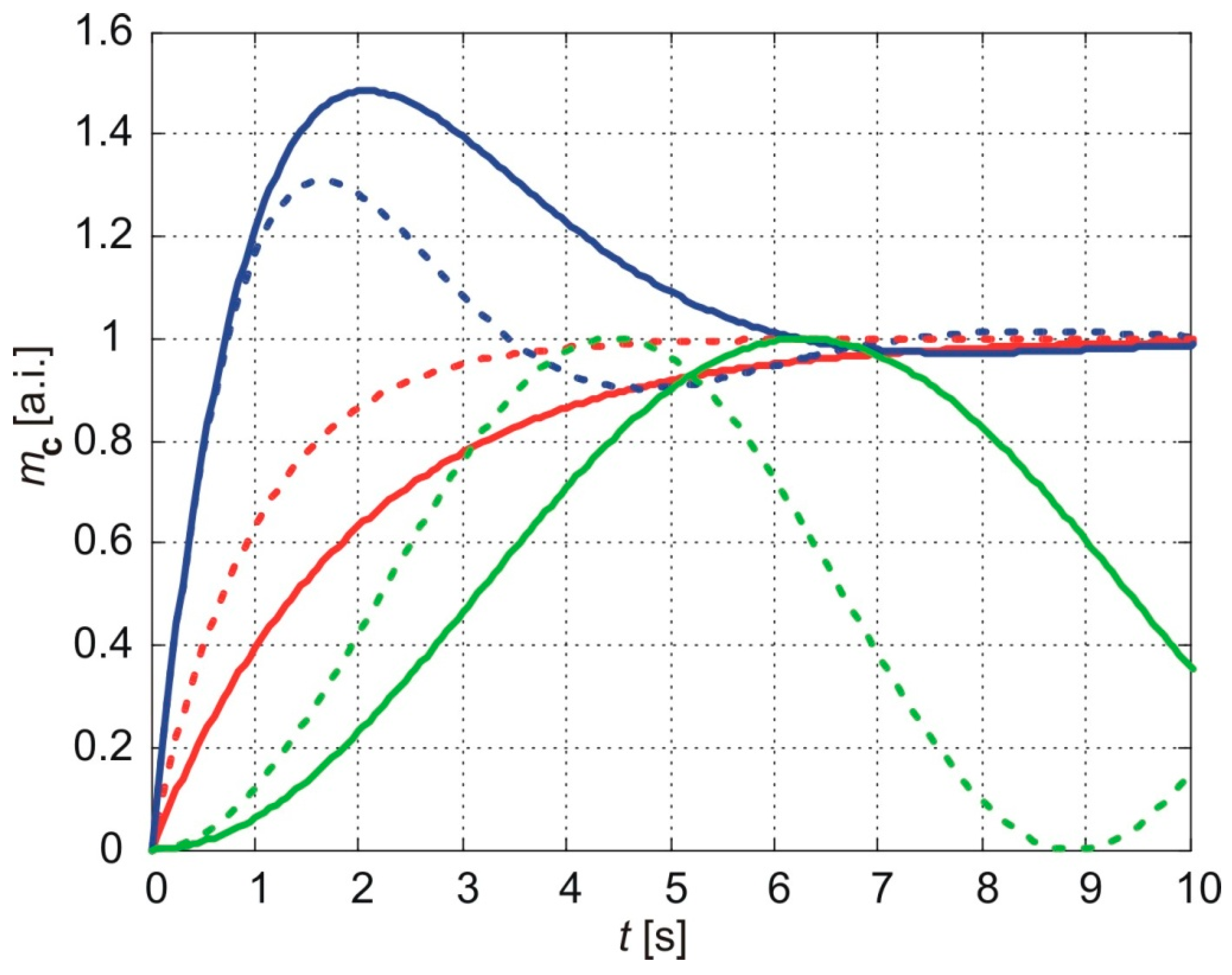

Figure 7 illustrates the evolution of the cumulative number of molecules predicted by the three considered models for

b=1 and two values of the parameter

a:

a=1 (solid lines) and

a=2 (dotted lines). The results of the classical model are represented by the red lines, the exponentially fading memory model by the blue lines, and the power-law fading memory model by the green lines.

As shown in

Figure 7, an increase in the parameter

a reduces the settling time and rising time of the cumulative amount of molecules predicted by the classical model and the exponential fading memory model. In contrast, for the power-law fading memory model an increase in

a leads to an increase in the frequency of oscillations of the cumulative amount of molecules. The parameter

a is inversely proportional to the thickness of the sample (Eq. 52), meaning that a decrease in the sample thickness does not alter the general form of the evolution of the cumulative amount of molecules but results in faster attainment of the steady state or higher-frequency oscillations of the cumulative amount of molecules.

From the analysis of the evolution of the cumulative amount of molecules passing through a thin nanoporous membrane, it can be concluded that inertial memory increases the time required for the cumulative amount of molecules to reach a steady state. The power-law fading memory model predicts a longer settling time compared to the exponential fading memory model for the same relaxation time. As the fractional exponent decreases the settling time, predicted by the power-law fading memory model, increases. For , the cumulative amount of molecules oscillates indefinitely without reaching a steady state.

6. Conclusions

This paper derives two causal extensions of the classical Fick’s theory of molecular transport, incorporating the inertial memory properties of the medium through which molecules propagate. Both memory models are formulated within the fading memory paradigm. Based on these causal theories, spectral functions for the molecular concentration profiles in nanoporous membranes and the back-side flux were derived and analyzed. The analysis revealed that membrane inertial memory induces two distinct regimes of concentration disturbance propagation: at low frequencies, the propagation is diffusive or super-diffusive, while at high frequencies, the inertial memory models predict the emergence of standing waves. The frequencies at which standing waves appear, as well as their amplitudes, are determined by the type of fading memory model applied.

Additionally, by examining the evolution of the normalized cumulative amount of molecules delivered through the membrane, it was shown that inertial memory significantly alters the time dynamics, increasing the duration required to reach a steady state. This effect can have important implications for applications of nanoporous membranes, particularly in pharmacological research, such as in time-projected drug delivery systems.

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.; methodology, S.G.; software, S.G, D.C..; validation, S.G., D.C. and M.C.; formal analysis, S.G, M.C., and D.C.; investigation, S.G, D.C., and M.C.; resources, S.G, D.C; data curation, S.G, M.C., and D.C..; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G., M.C., D.C..; visualization, D.C..; supervision, S.G; project administration, S.G., D.C..; funding acquisition, S.G., D.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, Contract No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200017 (SG and DC).

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. The research is theoretical in nature, involving the proposal of a model and the analysis of its results. No databases were used in this study.

Acknowledgments of AI Assistance

We would like to express our gratitude for the assistance received in improving the clarity and coherence of the manuscript. However, it is important to clarify that the authors retain full responsibility for all content, analyses, and conclusions presented in this work. The role of artificial intelligence in this context was limited to providing language enhancement and stylistic suggestions, and does not imply that any part of the manuscript was generated by AI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Fractional Differ-Integrals –Definitions

A fractional order differential calculus is a generalization of the integer order integral and derivative to real or even complex order [

57,

58,

77,

78]. The time derivative of fractional order is made as a weighted mean of the first derivative in the time interval [0, t]. The value of that first derivative at the time t

1 far apart from t is given a smaller weight than those closer in time to t. The further in time from particular t, the smaller the derivative associated weight. In other words, as time goes by the effect of the past is fading away.

More recently, by the end of the twentieth century, it turned out that some physical phenomena are modeled more accurately when fractional calculus is used. Typical examples of the use of fractal derivatives can be found in many areas of physics and engineering [

51,

69],

There are three main definitions of the fractional order integrals, derivatives, and differences: Riemann–Liouville, Caputo-Fabrizio and Grünwald–Letnikov [

64,

65,

66,

67]. Some others are also present in the literature but are rarely used in applications. In this section, the Riemann–Liouville definition of fractional derivative is used:

where

and

) are the Euler Gamma functions and

the fractional order with

.

Appendix B

The Laplace transform method is often used for solving engineering and physical problems described by linear integro-differential or linear partial integro-differential equation [

73,

77].

The Laplace transform maps a real function

defined for all real numbers

t ≥ 0 (real argument), into the complex function

defined for all complex numbers left than

where

is real constant and

(complex argument). It is a unilateral transform defined by [

77]

A necessary condition for the existence of the integral is that f must be locally integrable on [0, ∞).

The formulae for the Laplace transform of the Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative has the same form as it for integer derivatives [

45]:

where

or

.

To obtain evolution of some function

which spectral function

is known, one should solve inverse Laplace transform. Inverse Laplace transform of functions of complex argument is defined by [

77]:

where the integration is done along the vertical line

in the complex plane such that

is greater than the real part of all singularities of

and

is bounded on the line.

The integral formula given by Eq A2-3 is called the Bromwich integral, or Mellin's inverse formula or the Fourier–Mellin integral. In many problems, computing the complex integral can be done by using the Cauchy residue theorem.

In practice, it is not necessary to solve the complex integral given by Eq A2-3 always. Instead, it could be used existing solutions given in tables inverse Laplace transforms [

72,

78] and various methods of representation of a complex function by functions which Bromowich integral solutions are known [

79].

References

- S. Polarz, Sebastian, B. Smarsly, Nanoporous materials, Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2002, Volume 2 (6): 581–612. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Broom, M. K. Thomas, Gas adsorption by nanoporous materials: Future applications and experimental challenges, MRS Bulletin, 2013, Volume 38 (5): 412–421. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Ross, Hydrogen storage: The major technological barrier to the development of hydrogen fuel cell cars, Vacuum. The World Energy Crisis: Some Vacuum-based Solutions, 2006, Volume 80 (10): 1084–1089. [CrossRef]

- C. Azevedo, B. Tavernier, J. L. Vignes, P. Cenedese,P. Dubot, Design of Nanoporous Alumina Structure and Surface Properties for Dental Composite, Key Engineering Materials. 2008, Volume 361–363: 809–812. [CrossRef]

- E. Gultepe, D.Nagesha, S. Sridhar, M.Amiji, Nanoporous inorganic membranes or coatings for sustained drug delivery in implantable devices, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews.2010, Volume 62 (3): 305–315. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaerger, D. Ruthven, Diffusion in nanoporous materials: fundamental principles, insights and challenges, New J Chem., 2016, Volume 40: 4027–4048. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaerger, D. M. Ruthven, D.N. Theodorou, Diffusion in Nanoporous Materials, Weinheim:Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2012, ISBN: 978-3-527-31024-1.

- H. Wu, D. Wang, and D.K. Schwartz. Connecting Hindered Transport in Porous Media across Length Scales: From Single-Pore to Macroscopic. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2020, Volume 11(20): 8825–8831. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Bouchaud, A. Georges, Anomalous diffusion in disordered media: Statistical mechanisms, models and physical applications. Physics Reports, 1990, Volume 195(4-5):127–293. [CrossRef]

- M. Isaiev, P.J. Newby, B. Canut, A. Tytarenko, P. Lishchuk, D. Andrusenko, R. Burbelo, Thermal conductivity of partially amorphous porous silicon by photoacoustic technique. Materials Letters, 2014, Volume 128: 71–74. [CrossRef]

- M. Isaiev, S. Tutashkonko, V. Jean, K. Termentzidis, T. Nychyporuk, D. Andrusenko, V. Lysenko, Thermal conductivity of meso-porous germanium. App. Phys. Lett., 2014, Volume 105(3): 031912. [CrossRef]

- M. Fernandes, L. Simon, and N.W.Loney, Mathematical modeling of transdermal drug delivery systems: Analysis and applications, J. Memb. Sci, 2005, Volume 256: 184-192. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Jones, K.A.J. White, M.B. Delgado-Charro, A mechanicistic approach to modelling the formation of a drug reservoir in the skin, Math. Biosci. 2016, Volume 281: 36–45. [CrossRef]

- M. Caputo, Diffusion of fluids in porous media with memory, Geothermics, 1999, Volume 28: 113–130. [CrossRef]

- F. Cesarone, M. Caputo, C. Camettia, Memory formalism in the passive diffusion across, highly heterogeneous systems. Journal of Membrane Science, 2005, Volume 250: 79–84. [CrossRef]

- M. Caputo, C. Cametti, V. Ruggero, Time and spatial concentration profile inside a membrane by means of a memory formalism, Physica A, 2008, Volume 387: 2010–2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Caputo and C. Cametti, Diffusion through skin in the light of a fractional derivative approach: progress and challenges, J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn, 2021, Volume 48:3–19. [CrossRef]

- M. Caputo, M. Fabrizio,. Admissible frequency domain response functions of dielectrics. Math. Method Appl. Sci. 2014, Volume 38: 930–936. [CrossRef]

- R. Metzler, A. Rajyaguru, and B. Berkowitz, Modelling anomalous diffusion in semi-infinite disordered systems and porous media, New J. Phys., 2022, Volume 24:123004. [CrossRef]

- Yee Rui Koh, MohammadAli Shirazi-HD, Bjorn Vermeersch, Amr M. S. Mohammed, Jiayi Shao, Gilles Pernot, Je-Hyeong Bahk, Michael J. Manfra, and Ali Shakouri, Quasi-ballistic thermal transport in Al0.1Ga0.9N thin film semiconductors, APPLIED PHYSICS LETTERS, 2016, Volume 109: 243107. [CrossRef]

- N. Korabel, R. Klages, A.V. Chechkin, I. M. Sokolov, V. Yu. Gonchar, Fractal properties of anomalous diffusion in intermittent maps, Phys. Rev. E, 2007, Volume 75: 036213. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Chen, B. Wang, and S. Granick, Memoryless self-reinforcing directionality in endosomal active transport within living cells, Nature Mater., 2015, Volume 14: 589. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, J. U. de Mel, R. M. Perera, P. Zolnierczuk, M. Bleuel, A. Faraone, and G. J. Schneider, Dynamics of phospholipid membranes beyond thermal undulations, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, Volume 9: 2956-2960. [CrossRef]

- F. Hofling and T. Franosch, Anomalous transport in the crowded world of biological cells, Rep. Progr. Phys., 2013, Volume 76: 046602. [CrossRef]

- J. Crank , The Mathematics of Diffusion, Oxford, Clarendon, UK, 1970.

- H. S. Carslaw, J. C. Jaeger, Conduction of Heat in Solids, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1959. ISBN 0 19 8533 68 3.

- H. Scher and E. W. Montroll, Anomalous transit-time dispersion in amorphous solids., .Phys. Rev. B 1975, Volume 12: 2455. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu and D. K. Schwartz, Nanoparticle Tracking to Probe Transport in Porous Media, Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, Volume 53(10): 2130-2139. [CrossRef]

- F. Höfling, T. Franosch, Anomalous transport in the crowded world of biological cells, Rep Prog Phys., 2013, Volume 76: 046602. [CrossRef]

- E. Zagato, K. Forier, T. Martens, K. Neyts, J. Demeester, S. De Smedt, et al., Single-particle tracking for studying nanomaterial dynamics: applications and fundamentals in drug delivery, Nanomedicine, 2014, Volume 9 :913– 927. [CrossRef]

- V. Peshkov, Second sound in helium II. J. Phys. 1944, Volume 8: 381–389.

- V. Narayanamurti, R.C. Dynes, Observation of second sound in bismuth. Phys. Rev. Lett. , 1972, Volume 28: 1461–1465. [CrossRef]

- K. Mitra, S. Kumar, A. Vedavarez and M.K. Moallemi, Experimental Evidence of Hyperbolic Heat Conduction in Processed Meat J. Heat Transfer, 1995, Volume 117(3). [CrossRef]

- Yu. A. Kirsanov, A. Yu. Kirsanov, and A.E. Yudakhin, Measurement of thermal relaxation and temperature damping time in a solid., High Temp, 2017, Volume 55: 114–119. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ding, K. Chen, B. Song, et al. , Observation of second sound in graphite over 200 K, Nat Commun, 2022, Volume 13: 285. [CrossRef]

- J. Jeong, X. Li, S. Lee, L. Shi, Y. Wang, Transient hydrodynamic lattice cooling by picosecond laser irradiation of graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, Volume 127:085901. [CrossRef]

- H. Scher, M. F. Shlesinger, and J. T. Bendler, Time-Scale Invariance in Transport and Relaxation, Phys. Today, 1991, Volume 44(1): 26. [CrossRef]

- R. Hilfer, Fractional Diffusion Based on Riemann-Liouville Fractional Derivatives, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2000, Volume 104(16): 3914–3917. [CrossRef]

- R. Metzler and J. Klafter, The Random Walk’s Guide to Anomalous Diffusion: A Fractional Dynamics Approach. Phys. Rep. 2000, Volume 339: 1-77. [CrossRef]

- R. Metzler, J.-H. Jeon, A. G. Cherstvy, and E. Barkai, Anomalous Diffusion Models and Their Properties: Nonstationarity, Non-ergodicity, and Ageing at the Centenary of Single Particle Tracking, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, Volume 16 :24128. [CrossRef]

- R. Metzler, J.-H. Jeon, and A. G. Cherstvy, Non-Brownian Diffusion in Lipid Membranes: Experiments and Simulations, Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembranes, 2016, Volume 1858 :2451. [CrossRef]

- K. Nørregaard, R. Metzler, C.M. Ritter, K.Berg-Sørensen, and L. B. Oddershede, Manipulation and Motion of Organelles and Single Molecules in Living Cells, Chem. Rev. 2017, Volume 117: 4342. [CrossRef]

- S. Galovic, A.I. Djordjevic, B.Z. Kovacevic, K.Lj. Djordjevic, D. Chevizovich. Influence of Local Thermodynamic Non-Equilibrium to Photothermally Induced Acoustic Response of Complex Systems. Fractal Fract. 2024, Volume 8:399. [CrossRef]

- K. Lj. Djordjevic, S.P. Milicevic, E. Galovic, S.K. Suljovrujic, D. Jacimovski, M. Furundzic, M.N. Popovic, Photothermal Response of Polymeric Materials Including Complex Heat Capacity, Int. J. Thermophys, 2022, Volume 43:68. [CrossRef]

- R Metzler and T F Nonnenmacher, Fractional diffusion: exact representations of spectral functions, J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 1997, Volume 30: 1089–1093. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Joseph, L. Preciozi, Heat wave, Rev. Mod. Phys., 1989, Volume 61:41. [CrossRef]

- M Čukić, S Galovic, Mathematical modeling of anomalous diffusive behavior in transdermal drug-delivery including time-delayed flux concept, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2023, Volume 172: 113584. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Ozisik and D.Y. Tzou, On the wave theory of heat conduction, ASME J. Heat Transfer, 1994, Volume 116: 526-535. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Novikov, Resonant generation of harmonic thermal waves in media with memory J. Eng. Phys Thermophys 1992, Volume 62: 367-372. [CrossRef]

- I.A. Novikov, Harmonic thermal waves in materials with thermal memory, J. Appl. Phys., 1997, Volume 81: 1067–1072. [CrossRef]

- S. Galovic, D. Kostoski, Photothermal wave propagation in media with thermal memory, J. Appl. Phys., 2003, Volume 93 : 3063–3071. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhukovsky, Operational Approach and Solutions of Hyperbolic Heat Conduction Equations. Axioms. 2016, Volume 5(4):28. [CrossRef]

- R. Gorenflo, A. A. Kilbas, F. Mainardi, S.V. Rogosin, Mittag-Leffler Functions, Related Topics and Applications, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. ISBN 978-3-662-43930-2 (eBook). [CrossRef]

- V. J. Inglezakis, The concept of "capacity" in zeolite ion-exchange systems, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2005, Volume 281 (1): 68-79. [CrossRef]

- C. Cattaneo, Sur une forme de l’equation de la chaleur eliminant le paradowe d’une propagation instantanee, C. R. Acad. Sci., 1958, Volume 247 : 431.

- P. Vernotte, Sur quelques complications possible dans les phenomenes de conduction de la chaleur, C. R, Acad. Sci.,1961, Volume 252 : 2190.

- L. Herrera, Causal Heat Conduction Contravening the Fading Memory Paradigm. Entropy, 2019, Volume 21(10): 950. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Sobolev, Local non-equilibrium transport models, Physics-Uspekhi, 1997, Volume 40(10) : 1043-1053. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Green, R.S. Rivlin, The mechanics of non–linear materials with memory (Part III). Arch. Rational. Mech. Anal. 1959, Volume 4: 387–404 .

- A.E. Green, R.S. Rivlin, The mechanics of non–linear materials with memory (Part I). Arch. Rational. Mech. Anal., 1957, Volume 1:1–21.

- B.D. Coleman, W. Noll, Foundations of linear viscoelasticity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1961, Volume 33: 239–249.

- B. D. Coleman, V.J. Mizel, On the general theory of fading memory. Arch. Rational. Mech. Anal. 1968, Volume 29:18–31.

- J. C. Saut, D.D. Joseph, Fading memory. Arch. Rational. Mech. Anal. 1983, Volume 81:53–95.

- K.B. Oldham and J. Spanier, The Fractional Calculus, New York: Academic, New York, USA 1974.

- I. Podlubny, Fractional differential equations , San Diego, CA: Academic Press, San Diego, USA, 1999.

- A. Tateishi, H. V. Ribeiro, E. K. Lenzi, The role of the fractional time-derivative operators in anomalous diffusion, Front Phys, 2017, Volume 5:1-5. [CrossRef]

- V.S. Kiryakova, Generalized Fractional Calculus and Applications, Harlow, Longman Scientific and Technical, 1994.

- E.K. Lenzi, A. Somer, R.S. Zola, R. S. da Silva, M. K. Lenzi, A Generalized Diffusion Equation: Solutions and Anomalous Diffusion, Fluids, 2023, Volume 8: 34. [CrossRef]

- A. Somer, M.N. Popovic, G.K. da Cruz, A. Novatski, E.K. Lenzi, S.P. Galovic, Anomalous thermal diffusion in two-layer system: The temperature profile and photoacoustic signal for rear light incidence, Int. J. Therm. Sci., 2022, Volume 179: 107661. [CrossRef]

- Dzielinski, D. Sierociuk, G. Sarwas, Some applications of fractional order calculus, Bull.Polish Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2010, Volume 58: 583–592. [CrossRef]

- A Somer, S Galovic, EK Lenzi, A Novatski, K Djordjevic , Temperature profile and thermal piston component of photoacoustic response calculated by the fractional dual-phase-lag heat conduction theory, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2023, Volume 203:123801. [CrossRef]

- Y. Q. Chen, I. Petras, B. M. Vinagre, A list of Laplace and inverse Laplace transforms related to fractional order calculus. [online] http://www.steveselectronics. com/petras/foc laplace.pdf.

- Y. G. Anissimov, A. Watkinson, Modelling skin penetration using the Laplace transform technique, Skin Pharmacol Physiol, 2013, Volume 26:286-294. [CrossRef]

- Y.G. Anissimov, O.G. Jepps, Y. Dancik, M.S. Roberts, Mathematical and farmacokinetics modelling of epidermal and dermo transport processes, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, Volume 65: 169–190. [CrossRef]

- A. Naegel , G. Wittum , Detailed modelling of skin penetration: an overview, Adv. Drug Deliv. Reviews 2013, Volume 65: 191–207. [CrossRef]

- SP Galovic, KL Djordjevic, MV Nesic, MN Popovic, DD Markushev , Time-domain minimum-volume cell photoacoustic of thin semiconductor layer. I. Theory, J. App. Phys. 2023, Volume 133 (24): 245701. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Lynn, Paul The Laplace Transform and the z-transform. Electronic Signals and Systems. London: Macmillan Education, London, UK. pp. 225–272 1986. ISBN 978-0-333-39164-8. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Roberts, H. Kaufman, Table of Laplace Transform, W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia and London, USA, 1966.

- G. Baumann, Sinc Based Inverse Laplace Transforms, Mittag-Leffler Functions and Their Approximation for Fractional Calculus, Fractal Fract. 2021, Volume 5: 43. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).