Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What power rating of the HPS is needed to fulfill the takeoff requirements, according to CS-25 [16], and what is the corresponding takeoff distance?

- What is the impact on the TMS, in terms of cooling demand during takeoff?

- What power rating of the HPS is needed to fulfill the go-around (missed approach) requirements, according to CS-25 [16],

- What are the climb and cruise performances of the HAPSS aircraft for various HPS ratings and operating conditions?

2. Materials and Methods

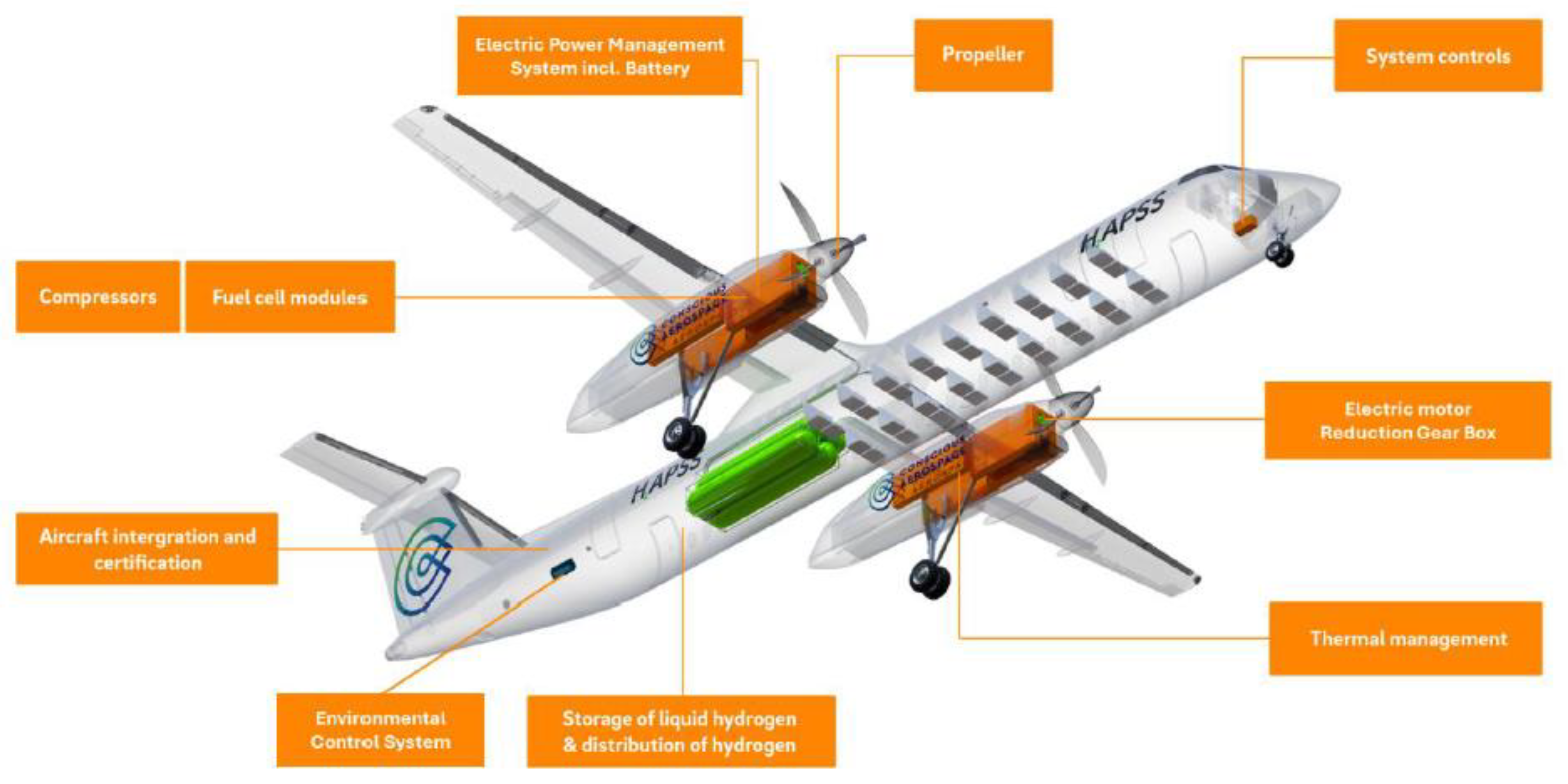

2.1. Aircraft Level Assumptions

- The aircraft operational empty mass (OEM) was increased from 11.6 t to 15.6 t, for the HAPSS aircraft. This increase is due to the additional HPS and LH2 fuel system masses (including tanks) [13].

- The maximum takeoff mass (MTOM) is lowered to the maximum landing mass of the reference aircraft (19.1 t). The reason for this decrease is that it is foreseen that the HAPSS aircraft cannot dump any fuel, after takeoff, in case of emergency [13].

- Due to the increased OEM and decreased MTOM, the payload mass is decreased to 3.1 t and the range is lowered to 750 km [13].

2.2. Mission Models

2.2.1. Mission Performance Tooling

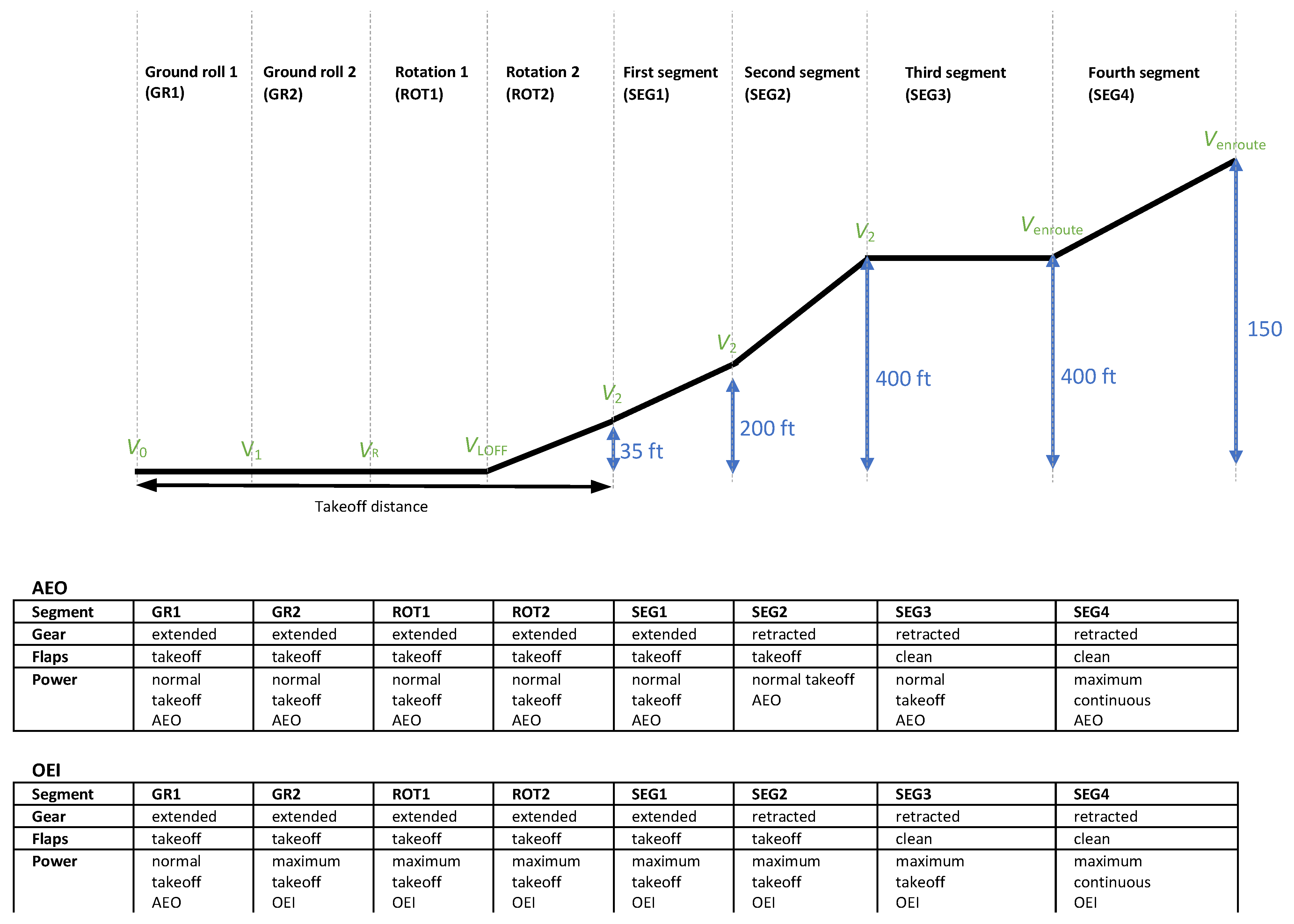

2.2.2. Modelling of the Takeoff Phase

- Initial speed v0. This is the start speed of the takeoff run, typically 0 m/s.

- Decision speed v1 In case an engine failure takes place below this speed, the aircraft must be able to break and come to a standstill before the end of the runway. When the aircraft has reached v1 it must be able to continue the takeoff with the other engine(s) that is/are still in operation.

- Rotation speed vR. At this speed the aircraft starts it rotation, by using the control surfaces.

- Liftoff speed vLOFF. At this speed the aircraft lifts off and its altitude increases with respect to the ground level.

- Obstacle clearance speed v2. The aircraft must have reached this speed when reaching 35 ft (10.7 m) altitude above the ground.

- Climb speed venroute. This is the indicated air speed for (the first part of) the climb phase.

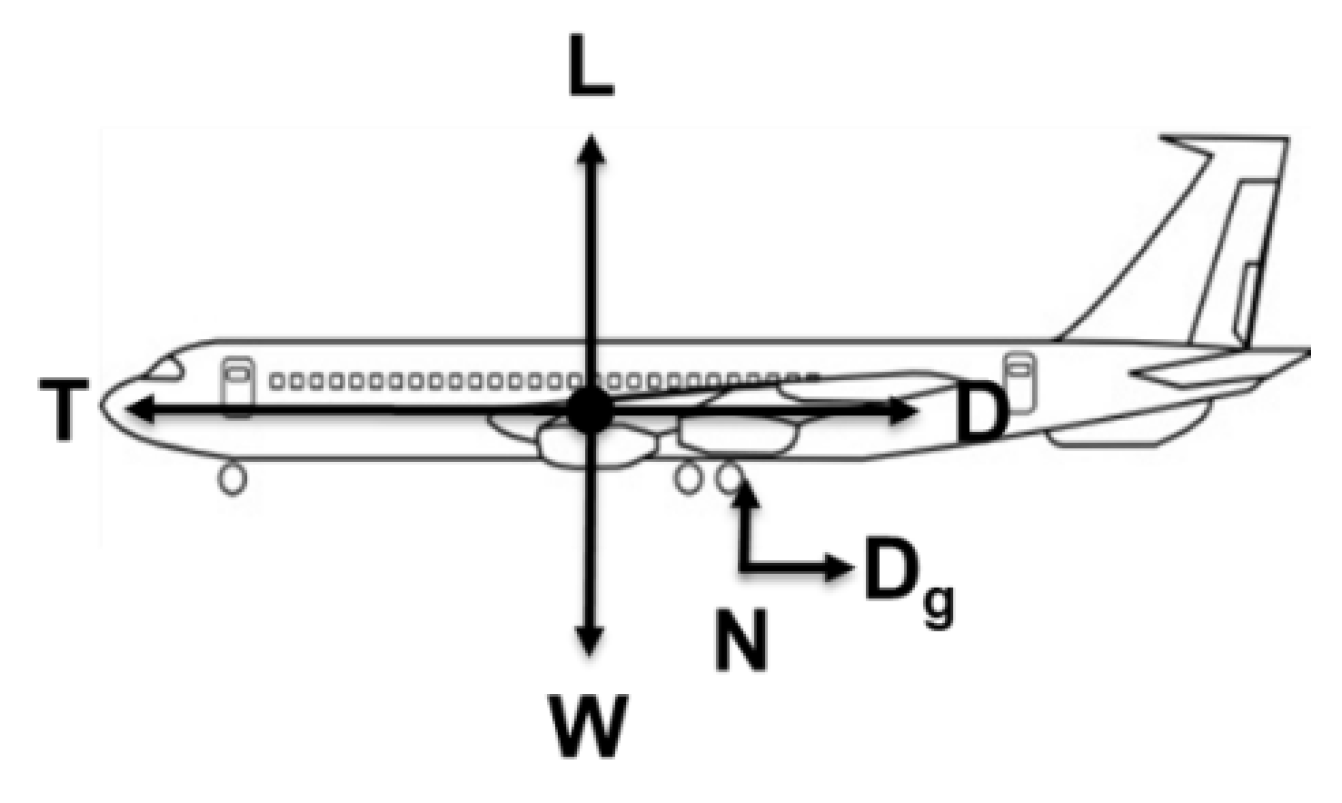

2.3. Aircraft Equations of Motion

2.4. Aerodynamic Coefficients

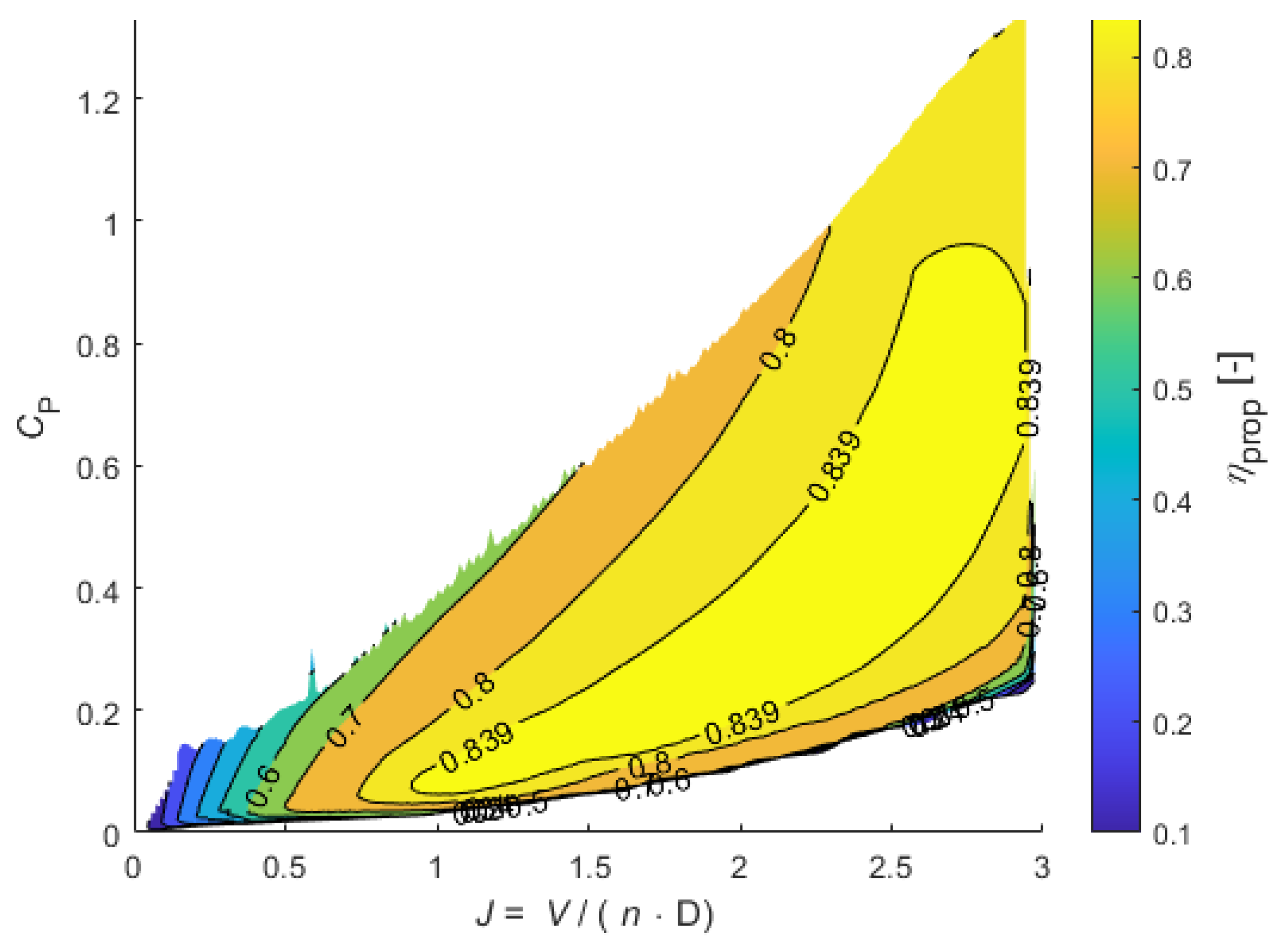

2.5. Propeller Model

2.6. Engine Model

2.7. HPS Model

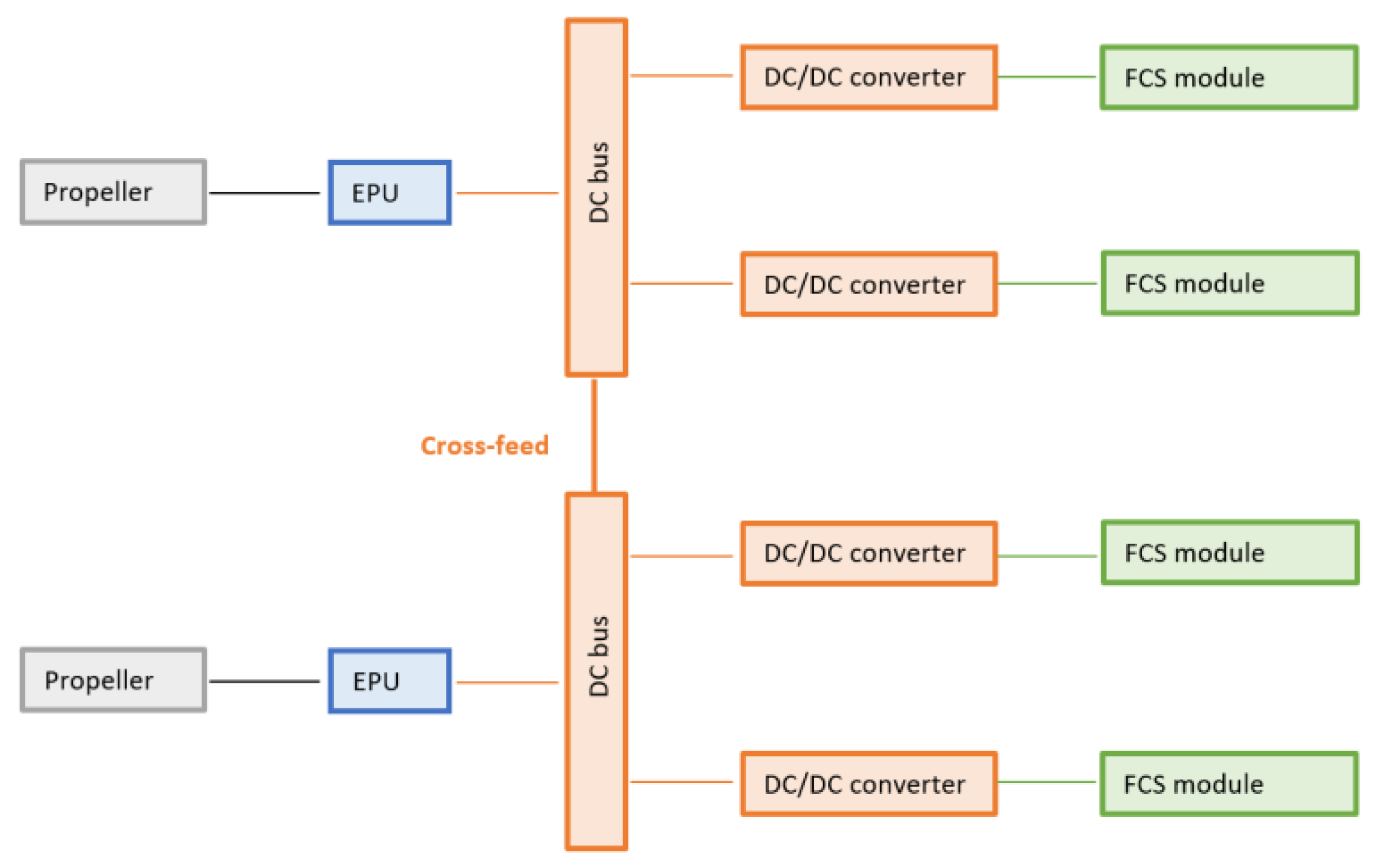

2.7.1. EPU Model

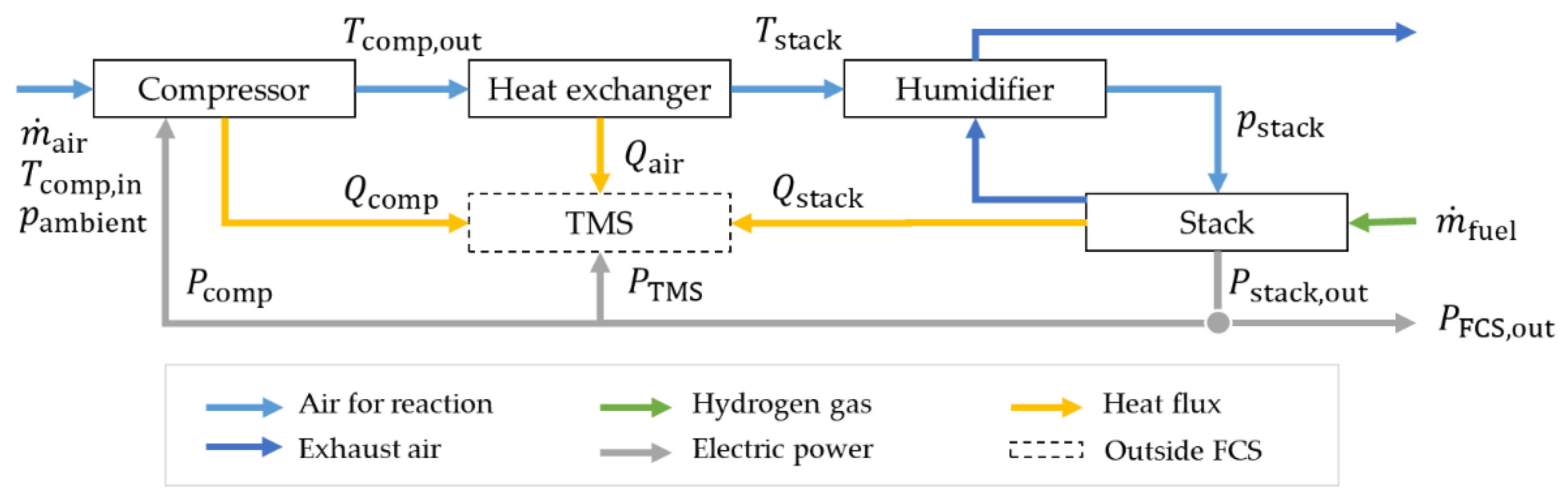

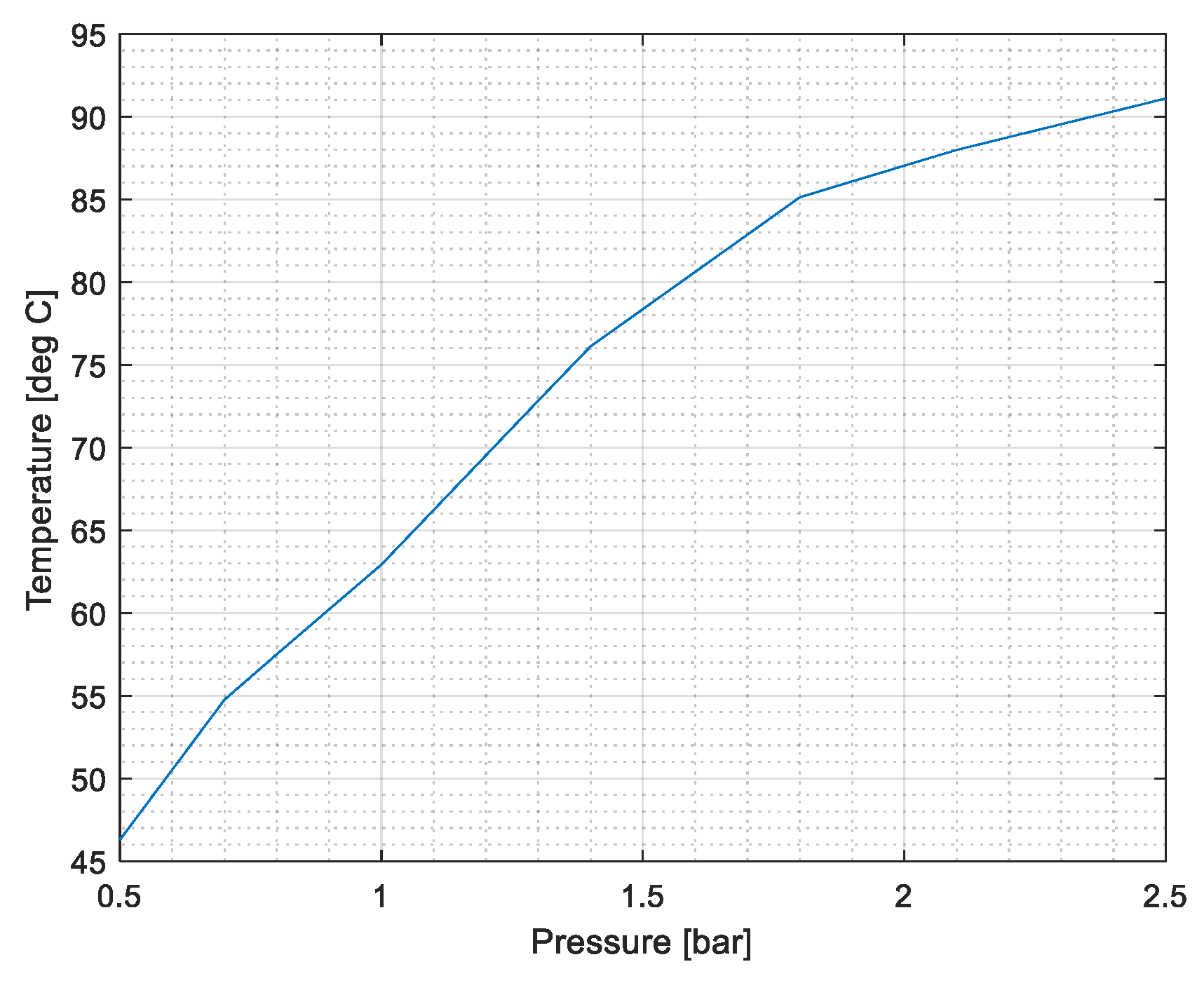

2.7.2. Fuel Cell System Model

- a compressor that is needed to deliver the air mass flow, at the pressure needed by the FC stack;

- a heat exchanger to lower the air temperature – which increases due to the compressor – to the temperature level needed by the FC stack;

- a humidifier that creates the level of air humidity needed by the FC stack.

3. Results

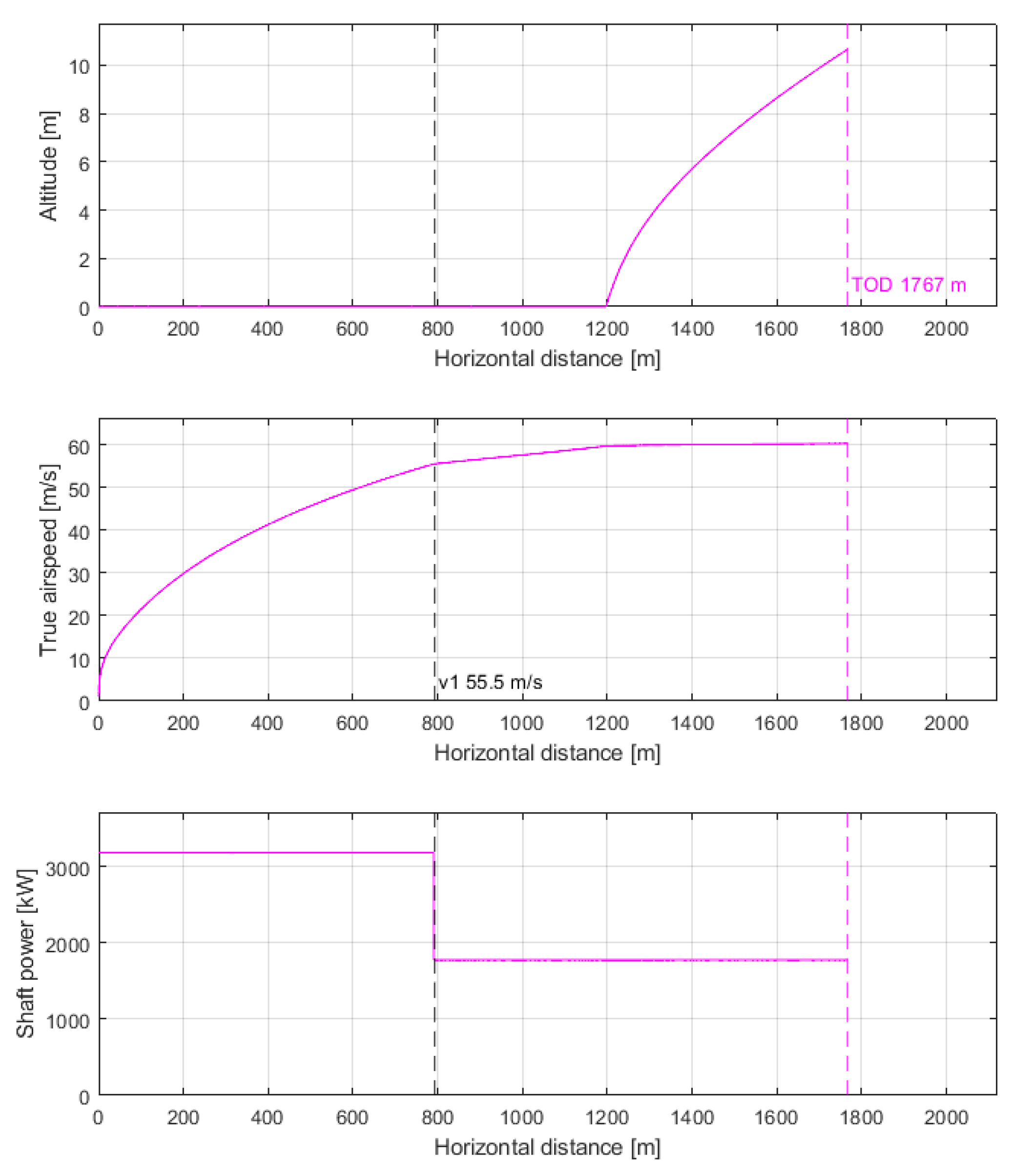

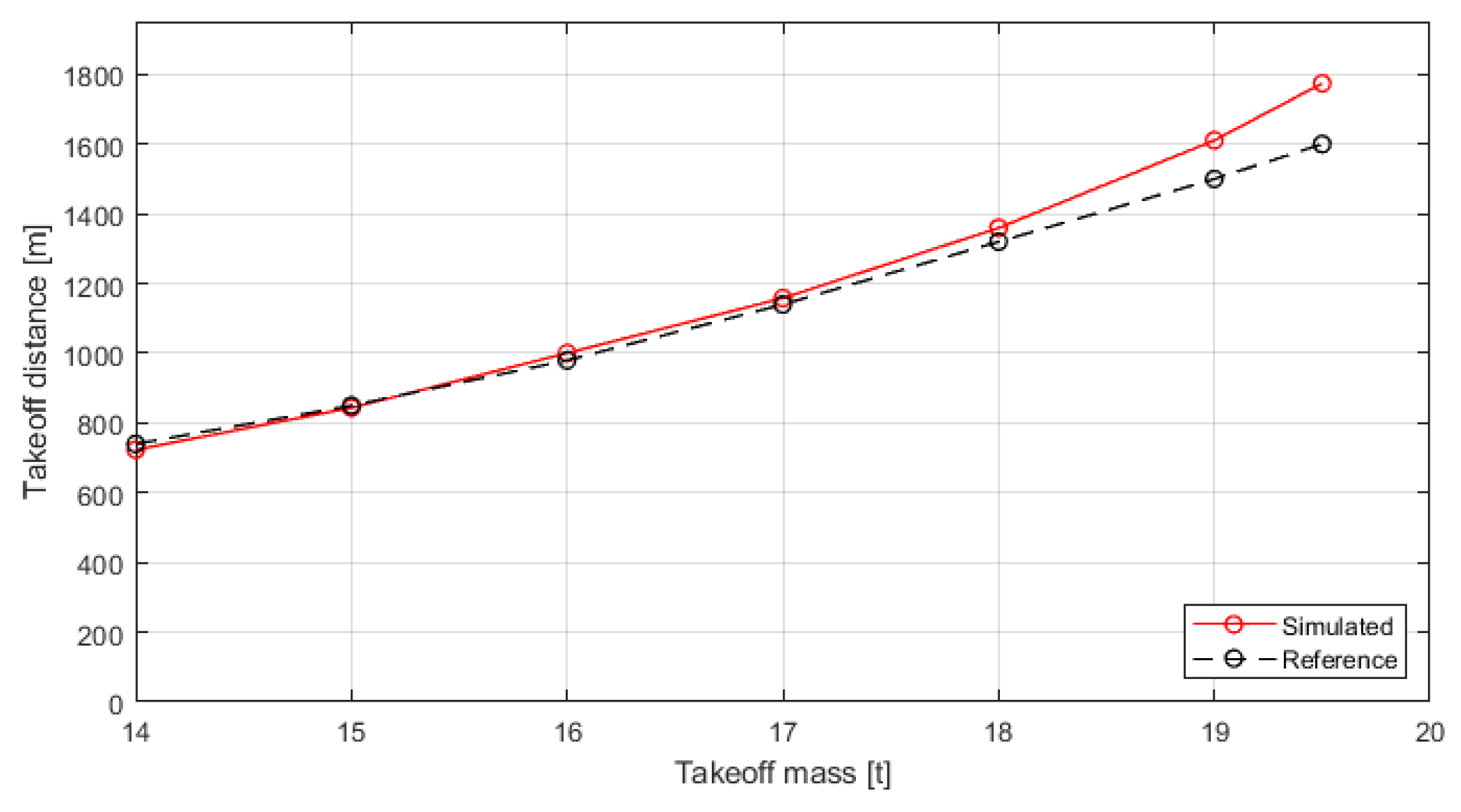

3.1. Takeoff Performance

3.1.1. Validation with Reference Aircraft Data

3.1.2. HAPSS Aircraft Results

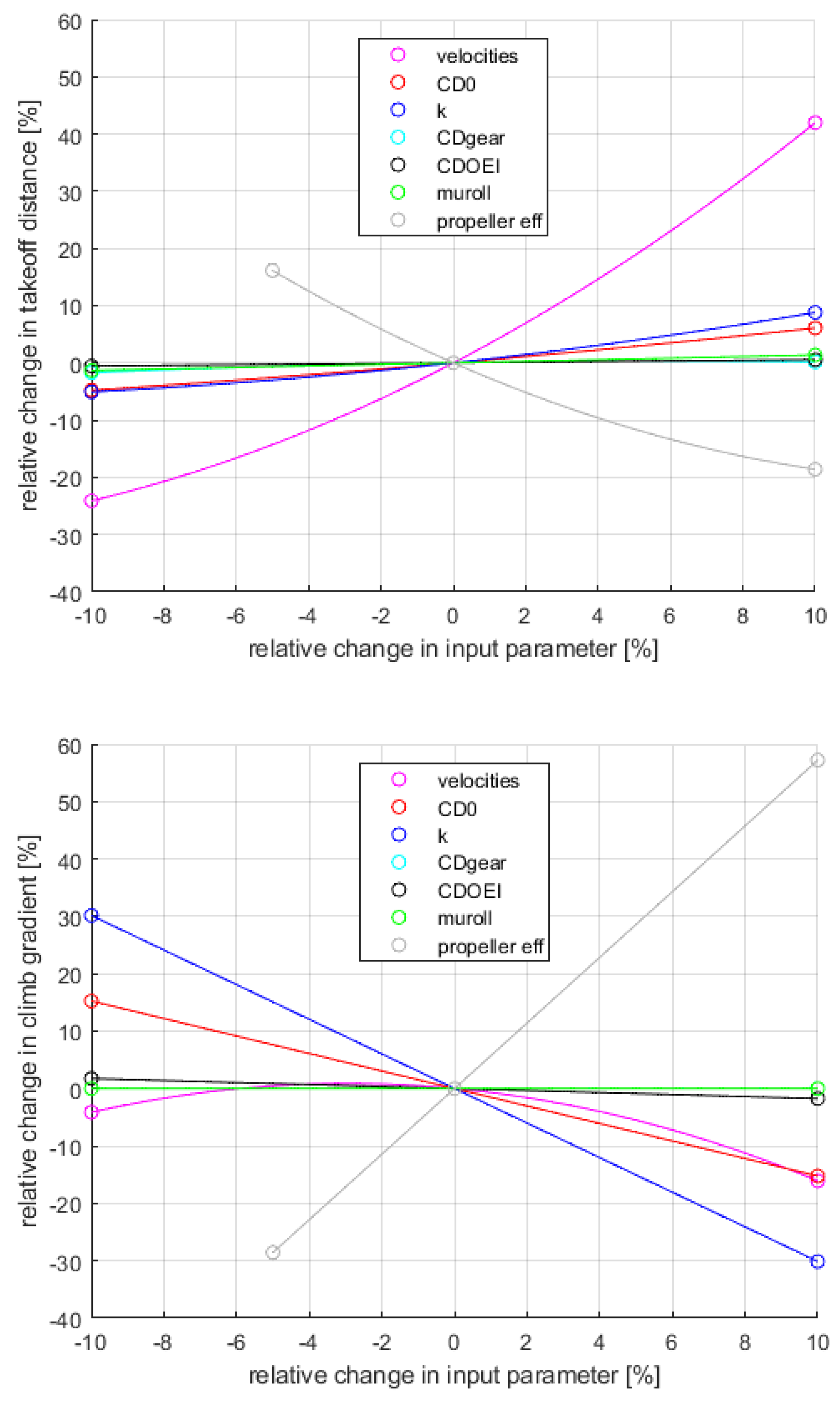

3.1.3. Sensitivity Analysis of HAPSS Aircraft Parameters

3.1.4. Effect of Gradual Power Increase on Fuel Cell Cooling Demand

3.2. Performance During Other Mission Phases

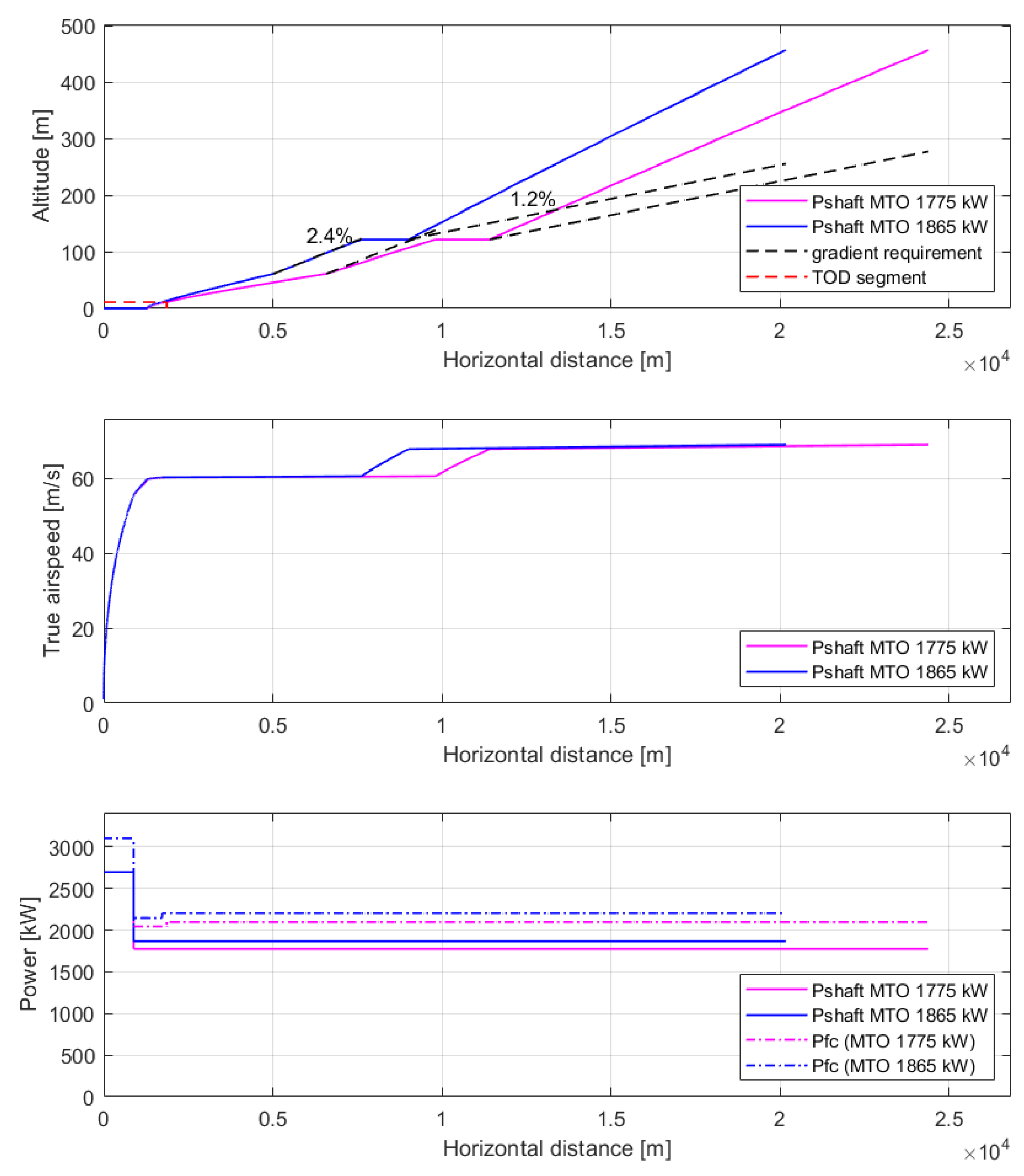

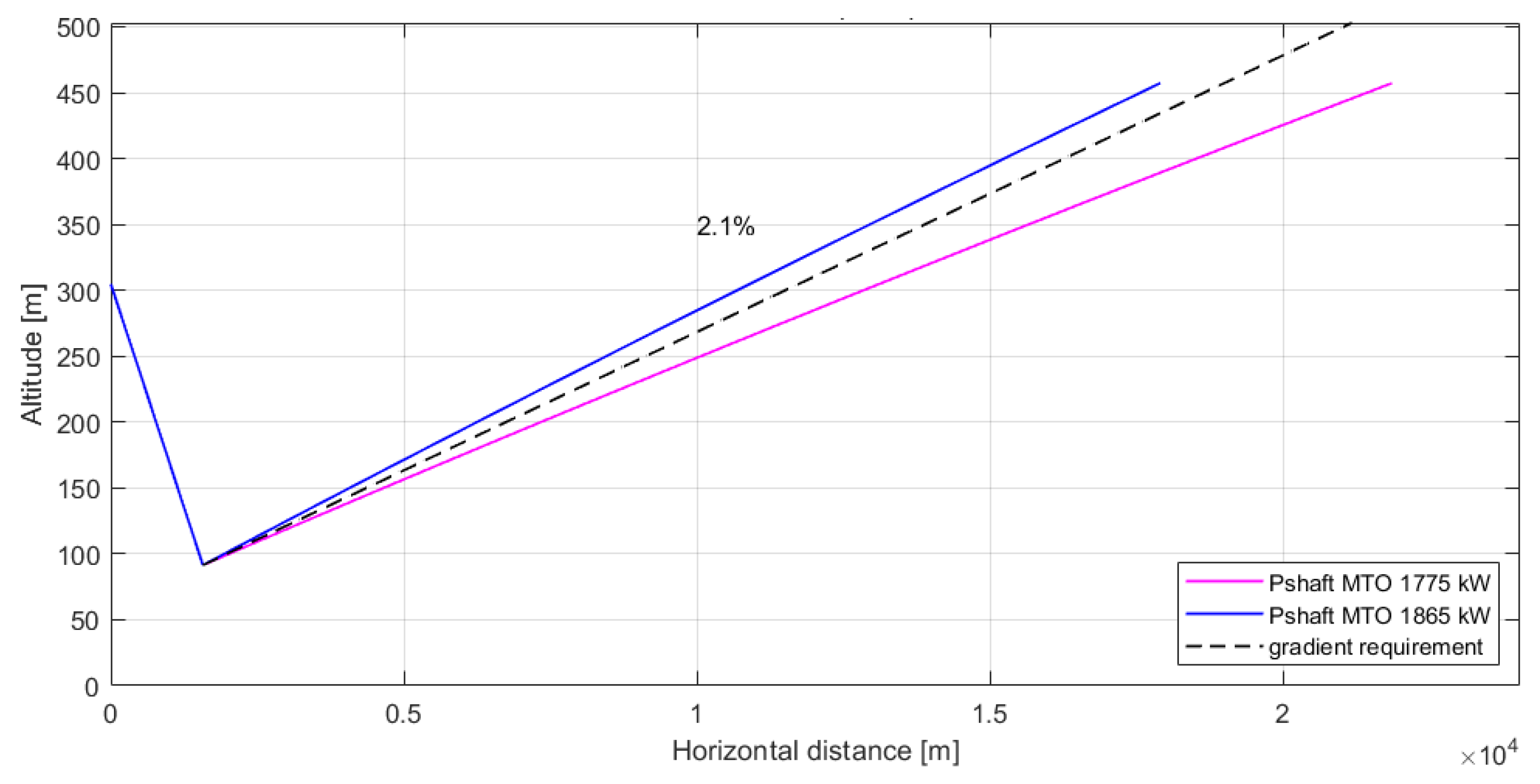

3.2.1. Go-Around Performance

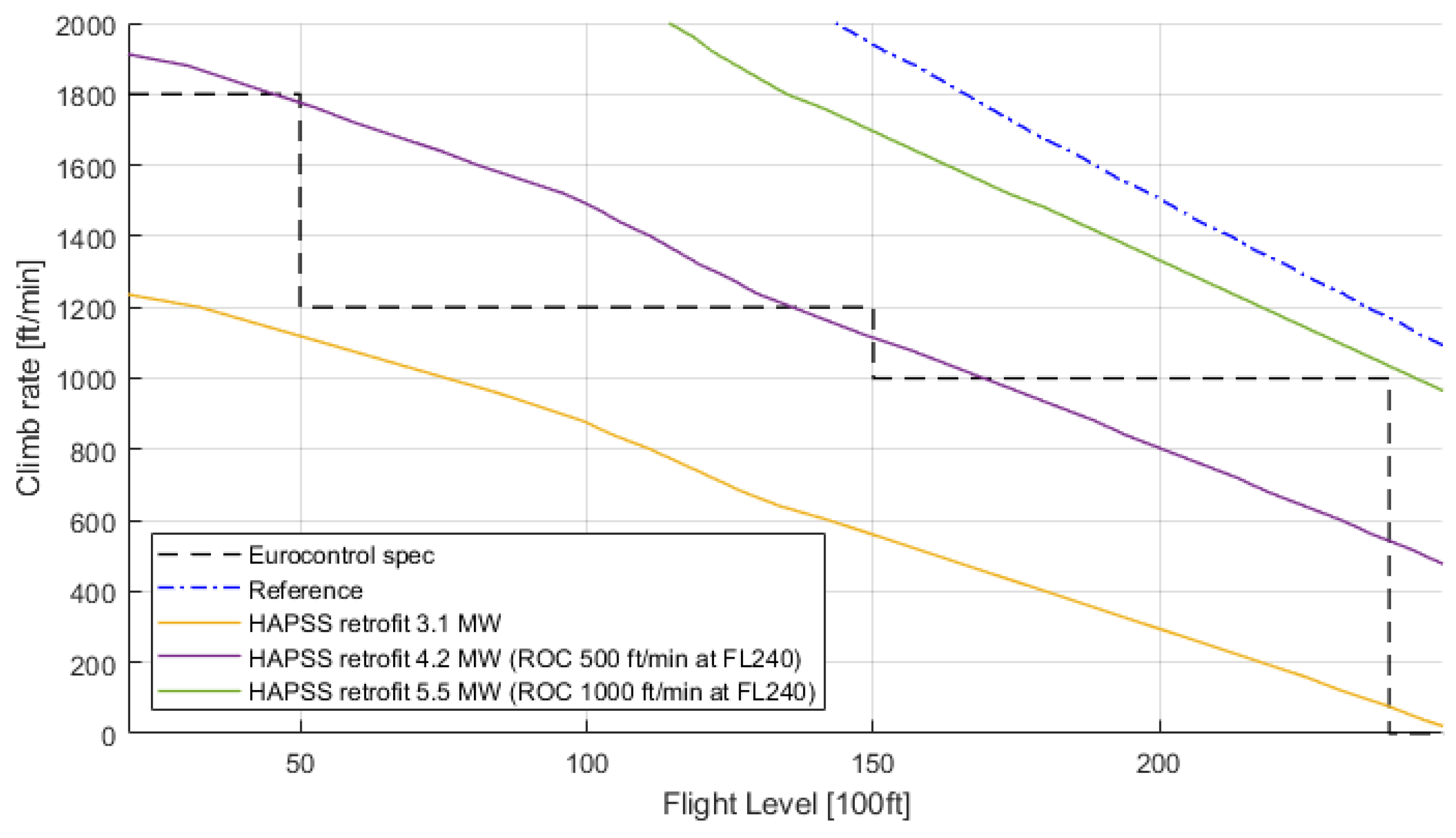

3.2.2. Climb Performance

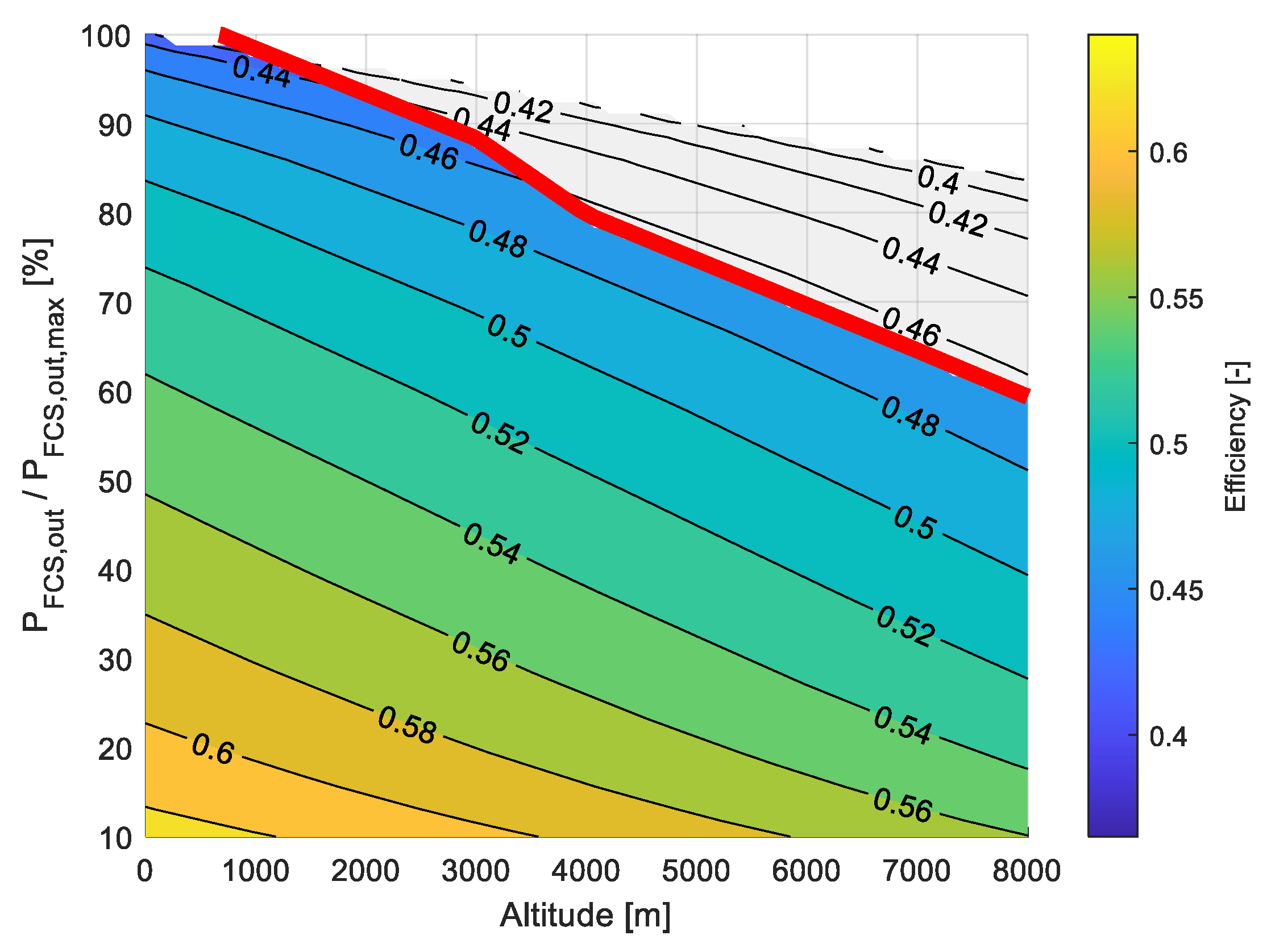

3.2.3. Cruise Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this paper, with HPS the combination of fuel cell system, electric distribution, power electronics and electric motors is meant.. |

| 2 | Picture adapted from https://simple-drawing.com/img/plane-outline-drawing-22.html. |

| 3 | Based on in-house experience at NLR. |

| 4 | For cruise at Mach 0.43, the overestimation of the compressor power is ca 10%. Since the compressor power itself is ca 10% of the FC stack power during cruise, the error in FCS output power is ca 1%. For low Mach numbers the error is significantly lower: at lift-off, the overestimation of the compressor power is ca 2% and the FCS output power error is ca 0.1%. |

| 5 | At the beginning of the takeoff, the propeller efficiency is already very low. When lowering it with more than 5%, the propeller model (see Section 2.5) gets outside operating limits of the propeller map. |

| 6 | The total climb to FL240 would take more than 1 hour. In the example mission profile of the reference aircraft, the total climb to FL240 takes only 20 minutes. |

| 7 | Altitude for a given speed at which the fuel flow is lowest and the potential range therefore maximal. |

| 8 | A service ceiling of 7620 m, was found to be possible with the 3.1 MW rated FCS, but at the expense of higher fuel consumption and slower speed, which is operationally not beneficial. |

| 9 | This sensitivity analysis was performed with the HAPSS aircraft. However, the lift induced drag coefficient was not changed between reference and HAPSS aircraft. |

References

- Home | Clean Aviation. Available online: https://www.clean-aviation.eu/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Homepage - Clean Hydrogen Partnership. Available online: https://www.clean-hydrogen.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Clean Sky 2 Joint Undertaking, Fuel Cells and Hydrogen 2 Joint Undertaking and McKinsey & Company (2020). Hydrogen powered aviation: A fact-based study of hydrogen technology, economics, and climate impact by 2050, Luxembourg, 22 July 2020.

- Airbus ZEROe. 2024. Available online: https://www.airbus.com/en/innovation/energy-transition/hydrogen/zeroe (accessed 30 October 2024).

- Lvovich, V.; Perkins, D.; Lavelle, T.; Hanlon, P.; Hasseeb, H.; McNichols, E.; Holland, F. Commercially-viable Hydrogen Aircraft for Reduction of Greenhouse Emissions. In Proceedings of the 26th International Society for Air Breathing Engines (ISABE) Conference, Toulouse, France, 22-27 September 2024.

- Ramm, J.; Rahn, A.; Silberhorn, D.; Wicke, K.; Wende, G.; Papantoni, V.; Dahlmann, K. Assessing the Feasibility of Hydrogen-Powered Aircraft: A Comparative Economic and Environmental Analysis. Journal of Aircraft, 2024, 61(5), 1337-1353. [CrossRef]

- Debney, D.; Beddoes, S.; Foster, M.; James, D.; Kay, E.; Kay, O.; Wilson, R. Zero-carbon emission aircraft concepts. Aerospace Technology Institute Fly Zero report FZO-AIN-REP-0007, 2022.

- Luchtvaart In Transitie, "Aviation in Transition". Available online: https://luchtvaartintransitie.nl/en (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Sahoo, S.; Zhao, X.; Kyprianidis, K. A review of concepts, benefits, and challenges for future electrical propulsion-based aircraft. Aerospace, 2020, 7(4), 44. [CrossRef]

- Adler, E. J.; Martins, J. R. Hydrogen-powered aircraft: Fundamental concepts, key technologies, and environmental impacts. Progress in Aerospace Sciences, 2023, 141, 100922. [CrossRef]

- Lammen, W. F.; Peerlings, B.; van der Sman, E. S.; Kos, J. Hydrogen-powered propulsion aircraft: conceptual sizing and fleet level impact analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences (EUCASS), Lille, France, July 2022. [EUCASS2022-7300.pdf].

- Home – ZeroAvia. Available online: https://zeroavia.com/ (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Rietdijk, B.; Selier, M. ARCHITECTURE DESIGN FOR A COMMERCIALLY VIABLE HYDROGEN-ELECTRIC POWERED RETROFITTED REGIONAL AIRCRAFT. In Proceedings of the ICAS conference, Florence, Italy, 9-13 September 2024. [ICAS2024_1090_paper.pdf].

- Tiwari, S.; Pekris, M. J.; Doherty, J. J. A review of liquid hydrogen aircraft and propulsion technologies. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2024, 57, 1174-1196. [CrossRef]

- HAPSS. Available online: https://www.hapss.eu/ (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Easy Access Rules for Large Aeroplanes (CS-25) - Revision from January 2023 | EASA (europa.eu). Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/easy-access-rules/online-publications/easy-access-rules-large-aeroplanes-cs-25 (Accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Q300 Dash 8 The Quiet One, Airport Planning Manual (APM), PSM 1-83-13, Bombardier Inc. Issue 2, 27 July 2001.

- CemAir / De Havilland-Dash 8 Q300. Available online: https://www.flycemair.co.za/general_r/dehavilland_dash8-q300.php (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- TYPE-CERTIFICATE DATA SHEET No. EASA.IM.A.191 For DHC-8, EASA Issue 16, 03 Feb 2023.

- TYPE-CERTIFICATE DATA SHEET No. IM.E.041 for PW100 series engines, EASA Issue: 07, 20 December 2023.

- MASS tool flyer. Available online: https://www.nlr.org/flyers/en/f543-analyse-the-energy-performance-of-aircraft.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Aircraft Performance Database > DH8C (eurocontrol.int). Available online: https://contentzone.eurocontrol.int/aircraftperformance/details.aspx?ICAO=DH8C&NameFilter=dash (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- BOMBARDIER Dash 8 Q300 | SKYbrary Aviation Safety. Available online https://skybrary.aero/aircraft/dh8c (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Shinkafi, A; Mohammed, A; Isah, A. Estimation of Drag Polar for ABT-18 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Nig. Res. Journal of Eng. and Env. Sc., 2021, 6. 357-365. 10.5281/zenodo.5048440. [CrossRef]

- Gunnam, R.S.; Design of a Regional Hybrid Transport Aircraft. MSc Thesis, San Jose State University, CA, USA, May 2019.

- Quillet, D.; Boulanger, V.; Rancourt, D.; Freer, R.; Bertrand, P. Parallel hybrid-electric powertrain sizing on regional turboprop aircraft with consideration for certification performance requirements. In Proceedings of AIAA Aviation 2021 Forum (p. 2443), 28 July 2021. [CrossRef]

- Roskam, J. Airplane Design: Preliminary sizing of airplanes. DARcorporation, Lawrence, Kansas, USA, 1985.

- Obert, E. Aerodynamic design of transport aircraft. IOS press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009.

- BOMBARDIER DASH-8-200-300 - SmartCockpit - Airline training guides, Aviation, Operations, Safety. Available online: https://www.smartcockpit.com/my-aircraft/bombardier-dash-8-200-300/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Torenbeek, E. Synthesis of subsonic airplane design. Delft University Press, Delft, The Netherlands, 1982.

- Raymer, D. Aircraft design: a conceptual approach. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., 2012.

- Bidin Suleimanovic. (Conscious Aerospace, Ypenburg, The Netherlands). Personal communication, May 2024.

- Pratt & Whitney Canada PW100 - Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pratt_%26_Whitney_Canada_PW100 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Schröter, J. Fuel cell air supply for hydrogen electric propulsion systems in aircraft applications. Doctoral dissertation, Universität Ulm, 13 June 2023, http://dx.doi.org/10.18725/OPARU-49048 .

- Larminie, J.; Dicks, A.; McDonald, M. S. Fuel cell systems explained (Vol. 2, pp. 207-225). J. Wiley, Chichester, UK, 2003.

- Schröder, M.; Becker, F.; Kallo, J.; Gentner, C. Optimal operating conditions of PEM fuel cells in commercial aircraft. Int. Journal of Hyd En, 2021 46(66), 33218-33240. [CrossRef]

- Turboprop Engine. Available online: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/Animation/turbtyp/etph.html (accessed on 2 November 2024).

| Parameter | Description | Value [17,18,19,20] |

|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | Aircraft model | 311 |

| R | Range | 920 NM (1704 km) |

| hCr | Maximum cruise altitude | 25000 ft (7620 m) |

| vCr | Cruise true air speed | 133 m/s (480 km/h) |

| MTOM | Maximum takeoff mass | 19505 kg |

| MLM | Maximum landing mass | 19051 kg |

| DPM | Design payload mass | 5300 kg |

| OEM | Operational empty mass | 11653 kg |

| Sw | Wing area | 56.3 m2 |

| Bw | Wing span | 27.4 m |

| Np | Number of engines / propellers | 2 |

| Engine | Engine type | Pratt & Whitney PW123 |

| MTO power | Maximum takeoff (shaft) power, per engine |

1775 kW |

| Propeller | Propeller type | Hamilton Sundstrand 14SF |

| Dp | Propeller diameter | 3.96 m |

| Bp | Number of propeller blades | 4 |

| Source | [-] | Lift-Induced Drag Coefficient k [-] |

|---|---|---|

| Gunnam [25] | 0.0247 | 0.0312 |

| Quillet et al [26] | 0.0322 | 0.0372 |

| Roskam averaged Statistics [27] |

0.0210 | 0.0289 |

| Roskam & Obert [28] | 0.0306 | 0.0320 |

| Aircraft Configuration | [-] | Lift-induced drag coefficient k [-] |

|---|---|---|

| Clean | 0.0322 | 0.0372 |

| Takeoff flaps | 0.0422 | 0.0403 |

| Takeoff flaps + Landing gear |

0.0572 | 0.0403 |

| Mission Phase | h [m] | v [m/s] |

(1 Engine) [kW] | (1 Engine) [kg/h] | [kg/kWh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| taxi | 0 | 10 | 100 | 86 | 0.860 |

| take off | 0 | 0 | 1775 | 507 | 0.285 |

| climb | 4000 | 100 | 1603 | 462 | 0.288 |

| cruise | 7620 | 133 | 1062 | 301 | 0.284 |

| descent | 4000 | 100 | 100 | 62 | 0.615 |

| landing | 0 | 0 | 855 | 267 | 0.321 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Air filter pressure drop [34] | - | 5e2 Pa |

| Humidifier pressure drop (supply side) [34] | - | 5e3 Pa |

| Heat exchanger pressure drop (supply side) [34] | - | 1e4 Pa |

| Specific heat capacity (for air) | 1006 J/kg/K | |

| Ratio of the specific heat capacities (for air) | 1.4 | |

| Compressor isentropic efficiency [36] | 0.76 | |

| Compressor driver efficiency (mechanical, electrical and power conversion efficiency) [36] | 0.97 0.94 0.95 = 0.87 |

| Speed Cases (at Which Max Power Is Reached) | Speed Value [kts] |

TOD [m], Determined by OEI Condition | Cooling Demand [MW] (at v = 40 kts) |

|---|---|---|---|

| from the start (reference case v0) | 0 | 1717 | 3.06 |

| ground minimum control speed vMCG | 78 | 1869 | 1.33 |

| air minimum control speed vMCA | 84 | 1901 | 1.25 |

| decision speed v1 | 108 | 2071 | 1.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).