Floating raft vibration isolation is a complex system with high nonlinearity, and it isn't easy to simulate it accurately by theoretical calculation. Some scholars have established a discrete transfer function mathematical model to obtain practical reference results using simulation and experimental methods [

4]. In the field of ship vibration control and floating raft structure design, a floating raft design scheme of air compressor unit [

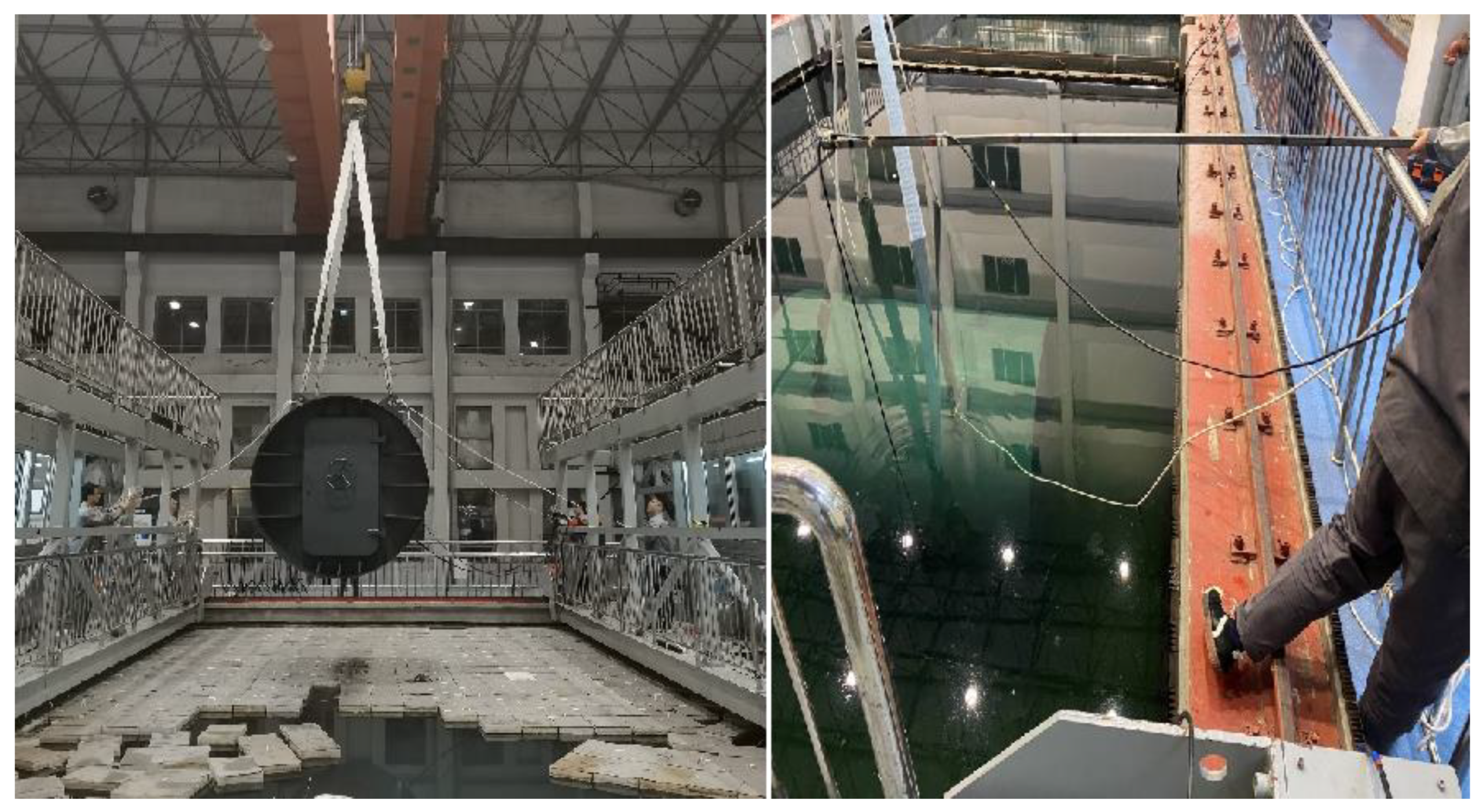

5] has been proposed to maintain the stability of the floating raft system and avoid the system resonance to a certain extent. Calculating the strength, mode, vibration response, and good power of the mechanism provides the reference for vibration isolation control. To maximize the overall vibration efficiency of the control system, low-frequency support and a low-frequency mounting system (LFMS) test stand was developed [

6]. Thrust bearings and Marine thrusters are added to the floating raft, and gas springs are installed to adjust the position of the suspended raft. The experimental results show that LFMS has a remarkable vibration isolation effect above 10 Hz. Considering the influence of infrastructure [

7], the effect of vibration isolators on evaluating flexible infrastructure is studied. The impact was assessed by comparing the maximum amplitude response of the structure, and experimental tests confirmed the rationality of the theoretical results. The device's effectiveness is analyzed using a damped damper and a structural vibration control method to optimize structural parameters. Experimental results show that [

8], compared with standard dampers, this method can reduce the amplitude ratio to zero and suppress higher vibration modes with fewer dampers. Based on the control scheme of filtered-x least mean square control strategy with dynamic variable step size [

9], the mathematical representation of the governing system is determined by the observer/Kalman filter identification method, which effectively reduces the system sound of submarines and other ships and improves the active vibration isolation effect of the floating raft system. Simulation and experiment establish the usefulness of this strategy. A novel silent hybrid "smart spring" isolation technology is created to deal with discrete frequency vibration sources [

10,

11]. This technique has the potential to offer outstanding isolation performance. Weng et al. [

12] built a floating raft vibration isolation dummy payload with switching tractor trailer control, using vibration acceleration response as the indicator of the vibration isolation efficacy. The empirical findings confirm the computer results. Sun et al. [

13] found a computational formula for the beam-based floating raft system using a derivative matrix. They studied the effects of several parameters, such as the setting position, dissipative, and volume of the dynamic vibration absorber, on its damping effect, as well as its damping effect at multiple excitation frequencies. Their findings demonstrated that it might increase the vibration-isolation performance of traditional floating raft systems. In contrast to Sun, Song et al. [

14] utilized periodic structure theory to develop a floating raft vibration isolation system to examine a flexible raft system's vibration and noise radiation suppression. Using numerical calculations, the suppression effects were improved. When the system stability is good, the higher the weight of the approximate pontoon, the better the system performance. When the system stability is good, the smaller the system support stiffness, the better for the system, as far as the natural working conditions allow. This gives a reference for determining counterweight and stiffness [

15]. In contrast, the intermediate raft's extra mass might strain the system. To save costs and promote convenience, the overall weight of the construction is kept as light as feasible. Compared to a typical numerical solution and other quasi-zero-stiffness (QZS) devices, Li et al. [

16] proved that the friction coefficient greatly minimizes the resonant crest in the vibration-isolated floating raft system using two layers of QZS. Fang et al. [

17] built a vibration isolation device for cabin auxiliary equipment to evaluate the influence of shell thickness, excitation source and thickness changes of different hulls and installation platforms on vibration response. The results show that the vibration isolation ability can be significantly enhanced. Studying the conflict between vibration isolation and energy reflection on a single isolation interface can reduce the impact of vibration on sensitive structures [

18]. Based on the employed active control mechanism and the experimental findings, it was demonstrated that even a soft and self-adapting isolation interface might produce the opposite outcome. This significantly lowers the seismic vibration propagation to susceptible structures. Through simulation and test-bed experiment [

19], it is studied that the proposed adaptive nonlinear control method has strong disturbance rejection ability against sensor noise and extra power disturbance, high vibration suppression level, and fast convergence rate. Asymmetric base isolation systems have specific responses to earthquakes when neighboring structures collide [

20]. When the collision occurs, the foundation raft's displacement will decrease. A design with vibration isolation will have superior vibration isolation than a structure without vibration isolation. One of the main challenges in isolating huge marine gear rafts is how to lessen the influence of excitation resonance. The vibration of marine constructions is a significant problem. A hybrid active/passive installation method is proposed to solve this problem [

21]. It uses numerical control braking to adjust the modal response of rigid structures while ignoring local displacement to eliminate resonance. High ship vibration can lead to mechanical equipment failure or shape breakdown due to fatigue. The finite element idealized model is utilized to examine vibration characteristics [

22], pinpoint its natural frequency and mode, and gauge the reaction of the nearby ship construction. Researchers created a numerical simulation dynamic model of a floating raft vibration isolation system that utilized the two-layer vibration isolation concept. Resonance is simple since the natural frequency is highly concentrated. As damping is raised, the resonance peak will be suppressed. Act synergistically in the broad frequency domain is attained when the dispersion of the floating raft vibration isolation system's natural frequency grows. The higher stiffness enhances the floating raft vibration isolation system's low-frequency performance [

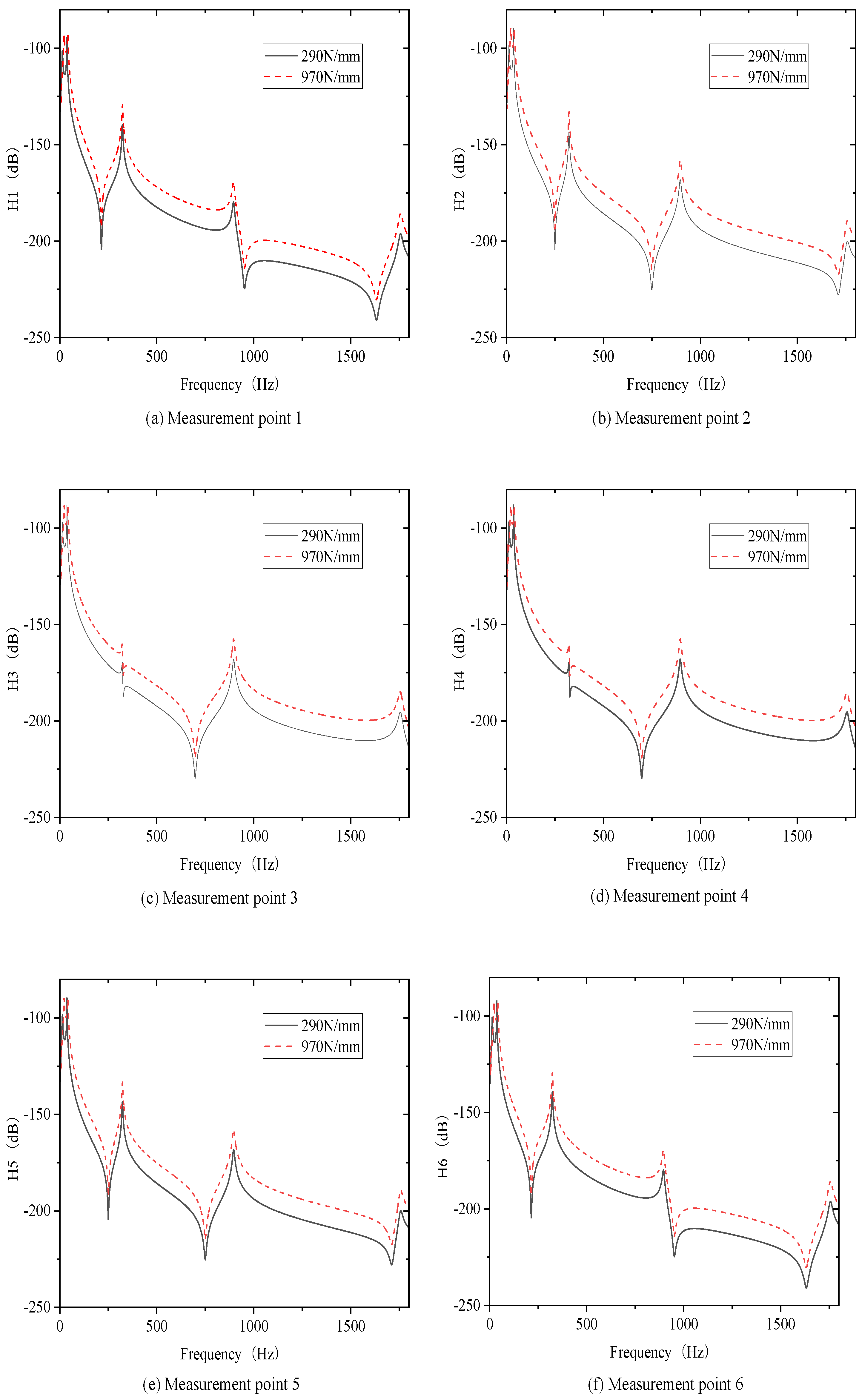

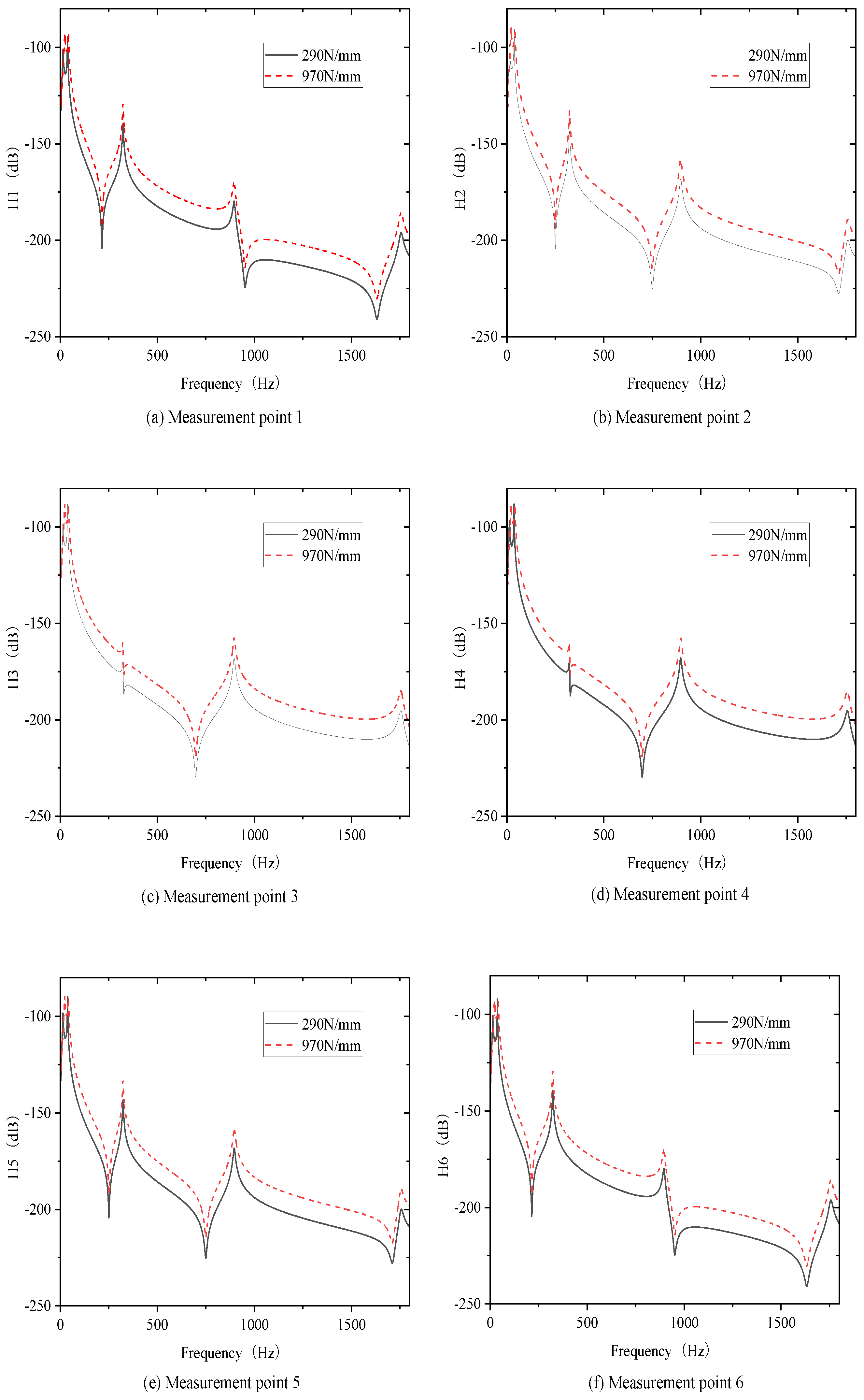

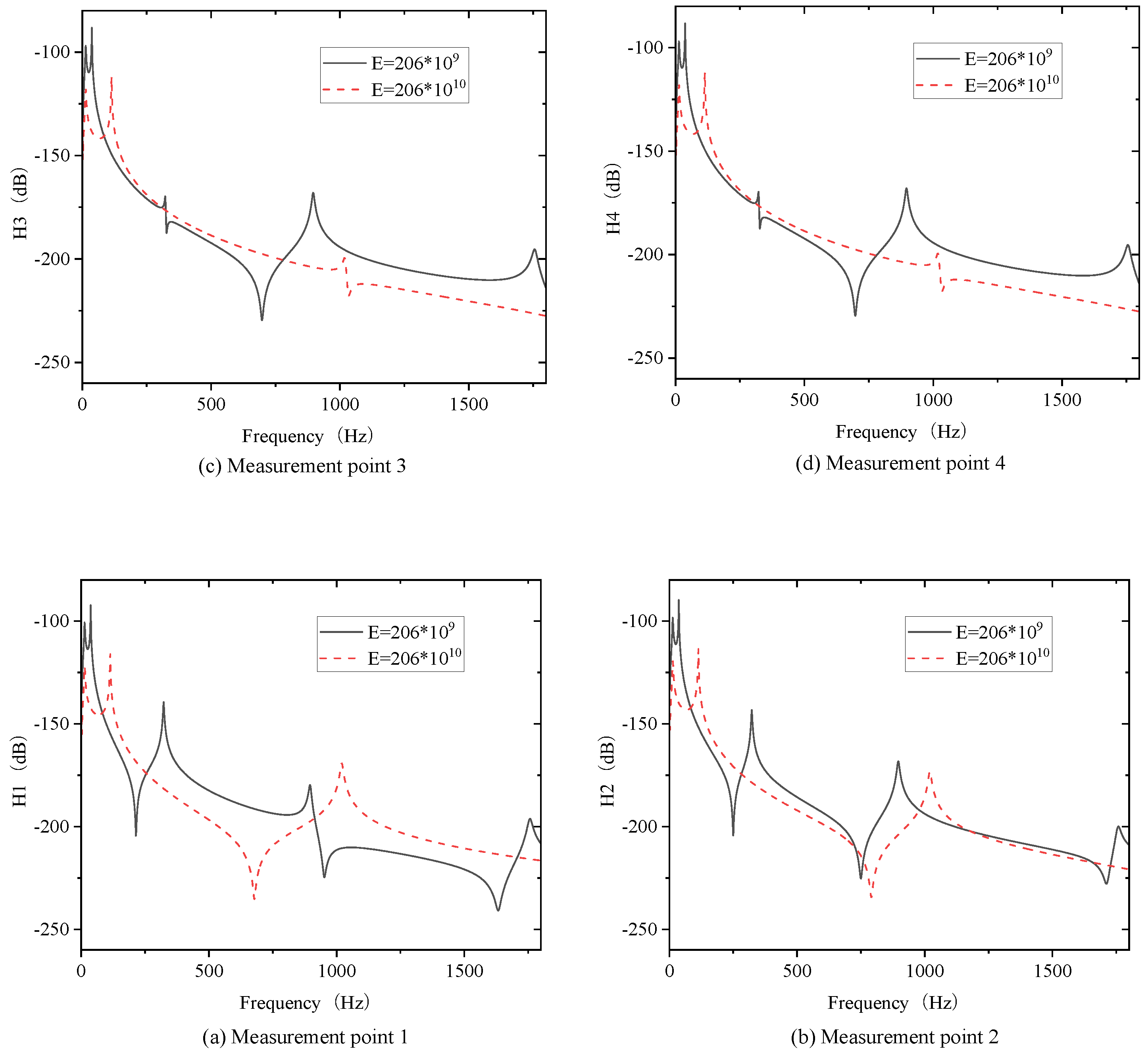

23].

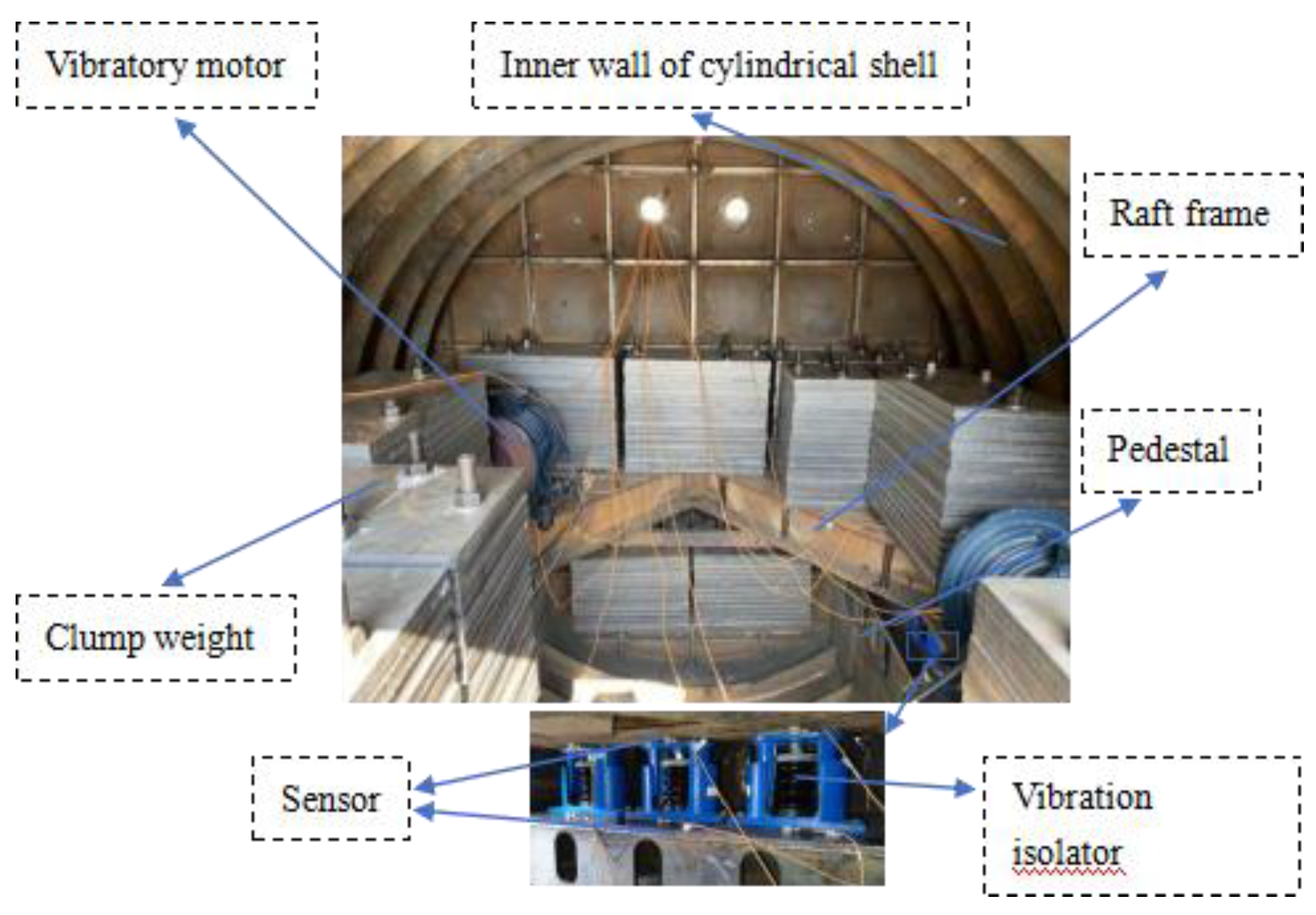

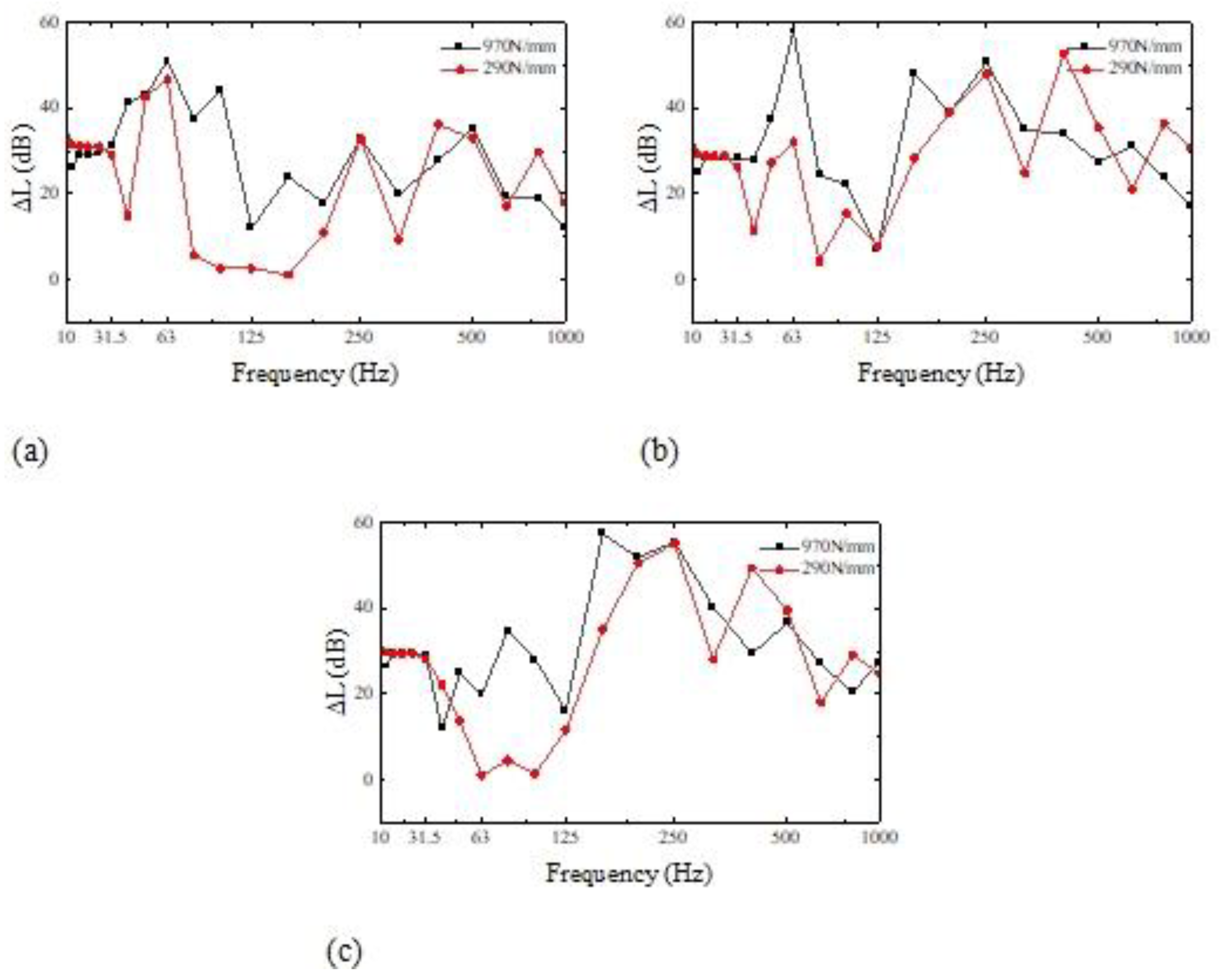

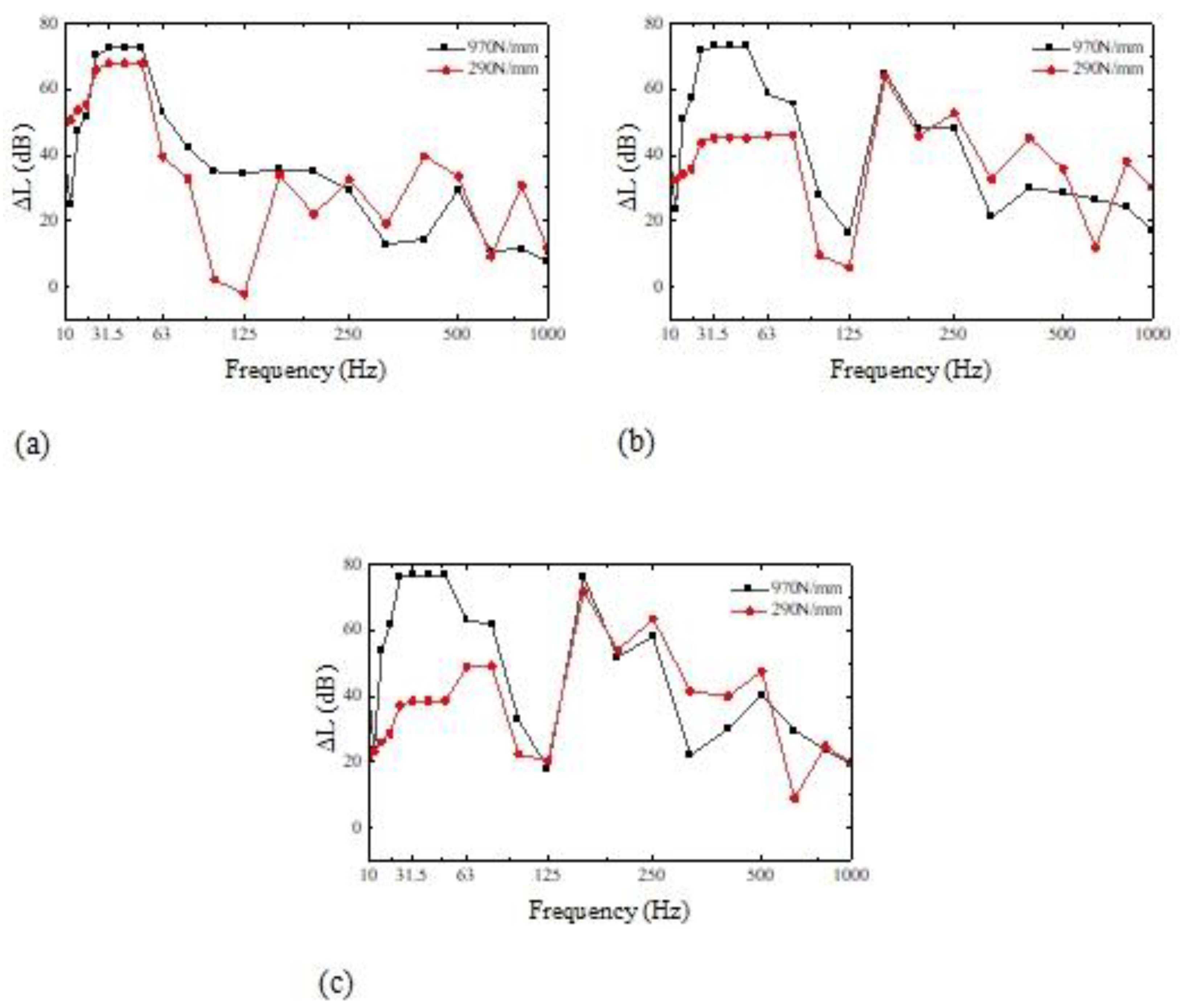

The current standard for ship mechanical vibration isolation is passive vibration isolation devices, such as solitary, twofold, and floating raft vibration isolation systems. The resonance transmitted from the raft to the cylinder ship can be reduced by using vibration isolation springs to elastically support the raft construction, which can considerably impact ship vibration and noise reduction. The vibration isolator is reduced using this technique to a spring and damping unit with vertical rigidity. Nevertheless, it overlooks the impact of the transverse stiffness and damping of the vibration isolator. Hu et al. [

24] addressed this issue by proposing several suiTable arrangement methods for the selection and arrangement principles of the vibration isolator and utilizing the vibration level drop as the vibration isolation impact of the vibration isolation evaluation. This offers vibration isolator arrangement design solutions. Li and Liu [

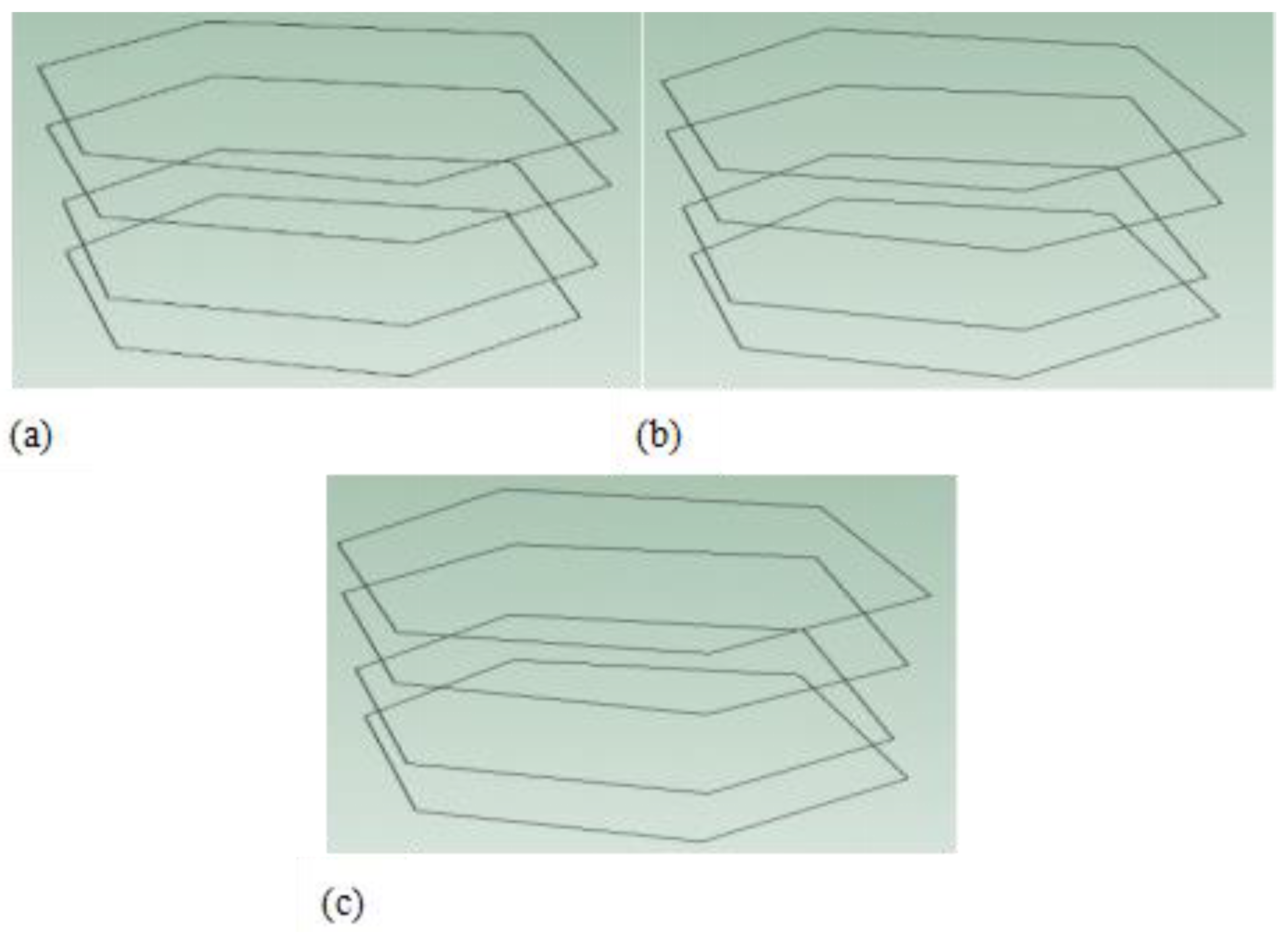

25] varied the raft frame's geometric characteristics while assuming that the overall mass of the elastic raft frame would remain constant to examine the effect of the intrinsic frequency distribution on vibration isolation performance. According to some research, the middle and high-frequency bands are where geometric parameters on the vibration isolation effect are most focused. The raft frame's height, aspect ratio, and number of ribs are the most significant geometric characteristics. Researchers frequently use output current to represent the vibration isolation effect. Through theoretical analysis, numerical data, and experimental testing of the floating raft vibration isolation system [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], it is essential to analyze the vibration problems in practical engineering applications. The floating raft isolation system with isotropic beams has no resonance peak. Hence it cannot boost damping opening avoidance in the high-frequency region. Wen et al. [

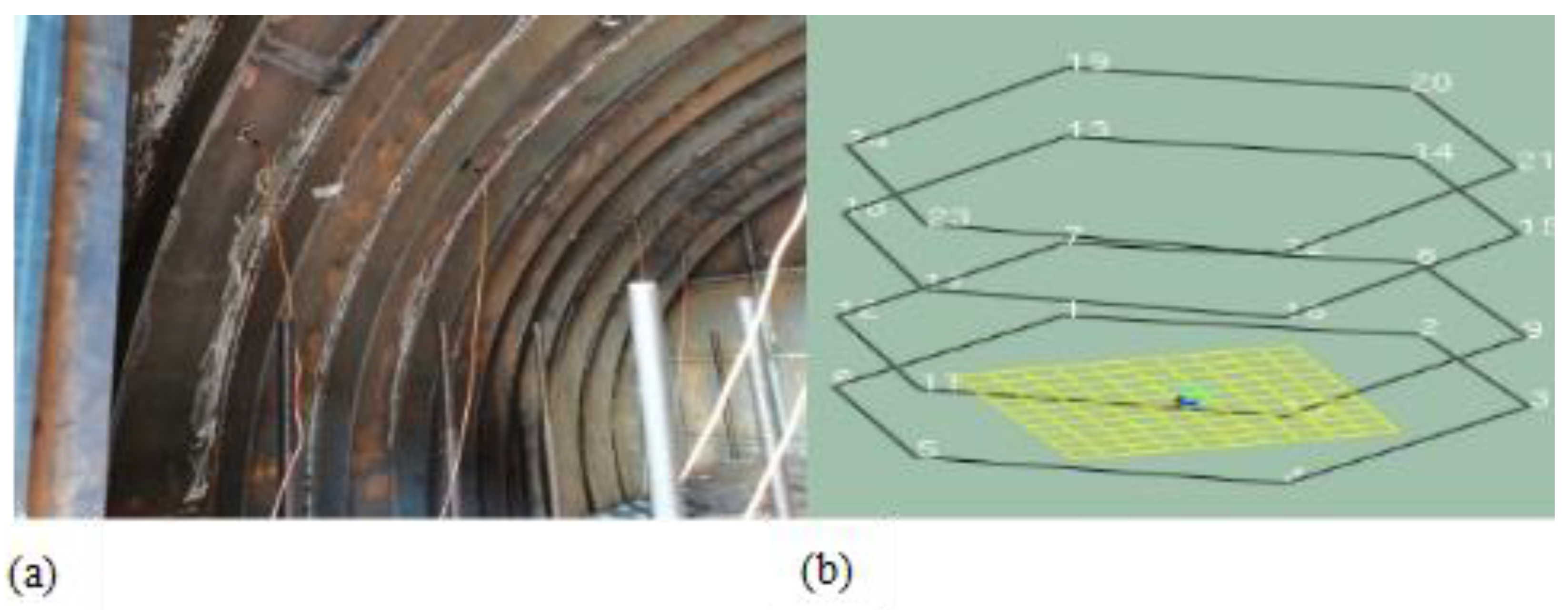

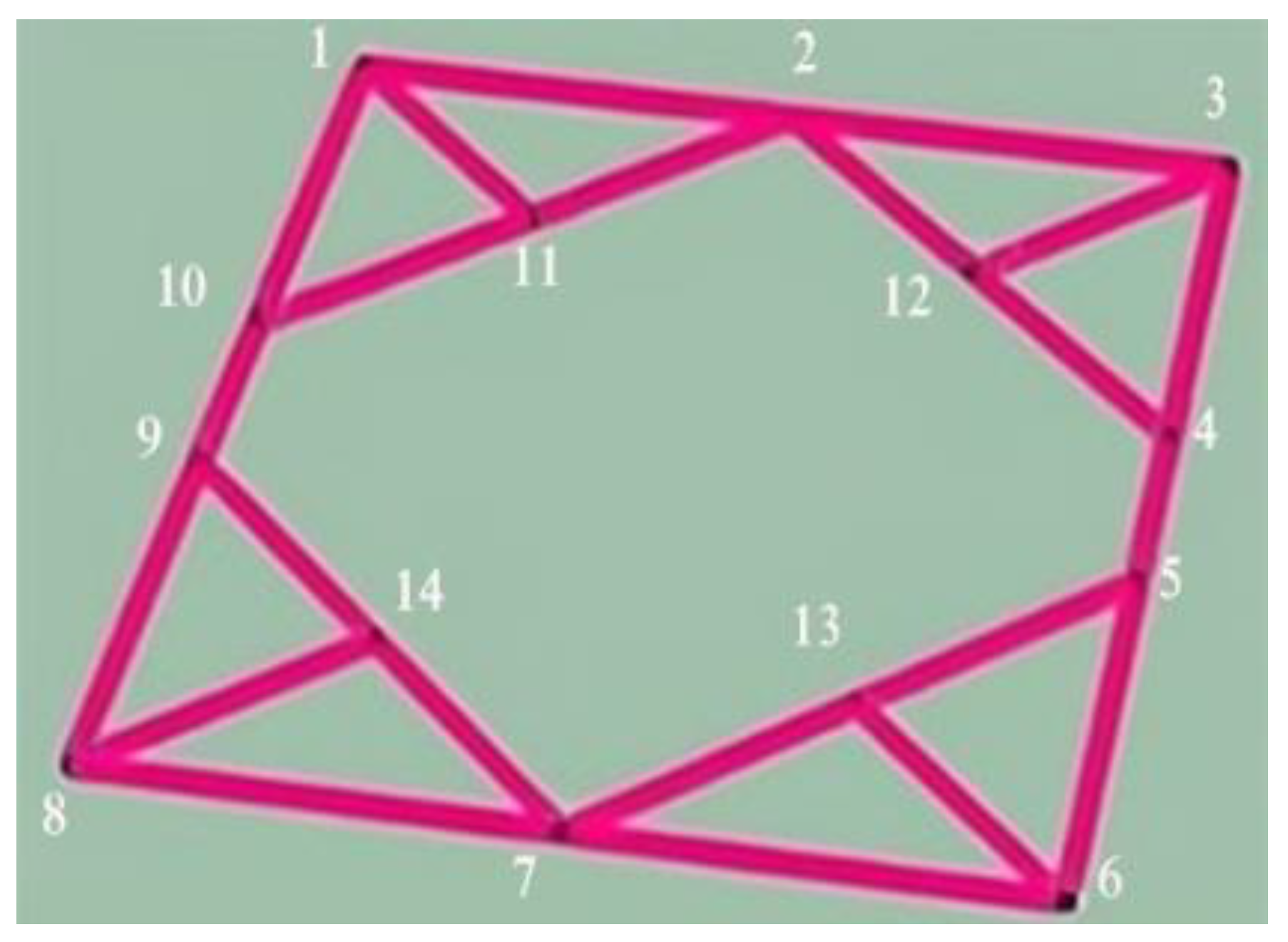

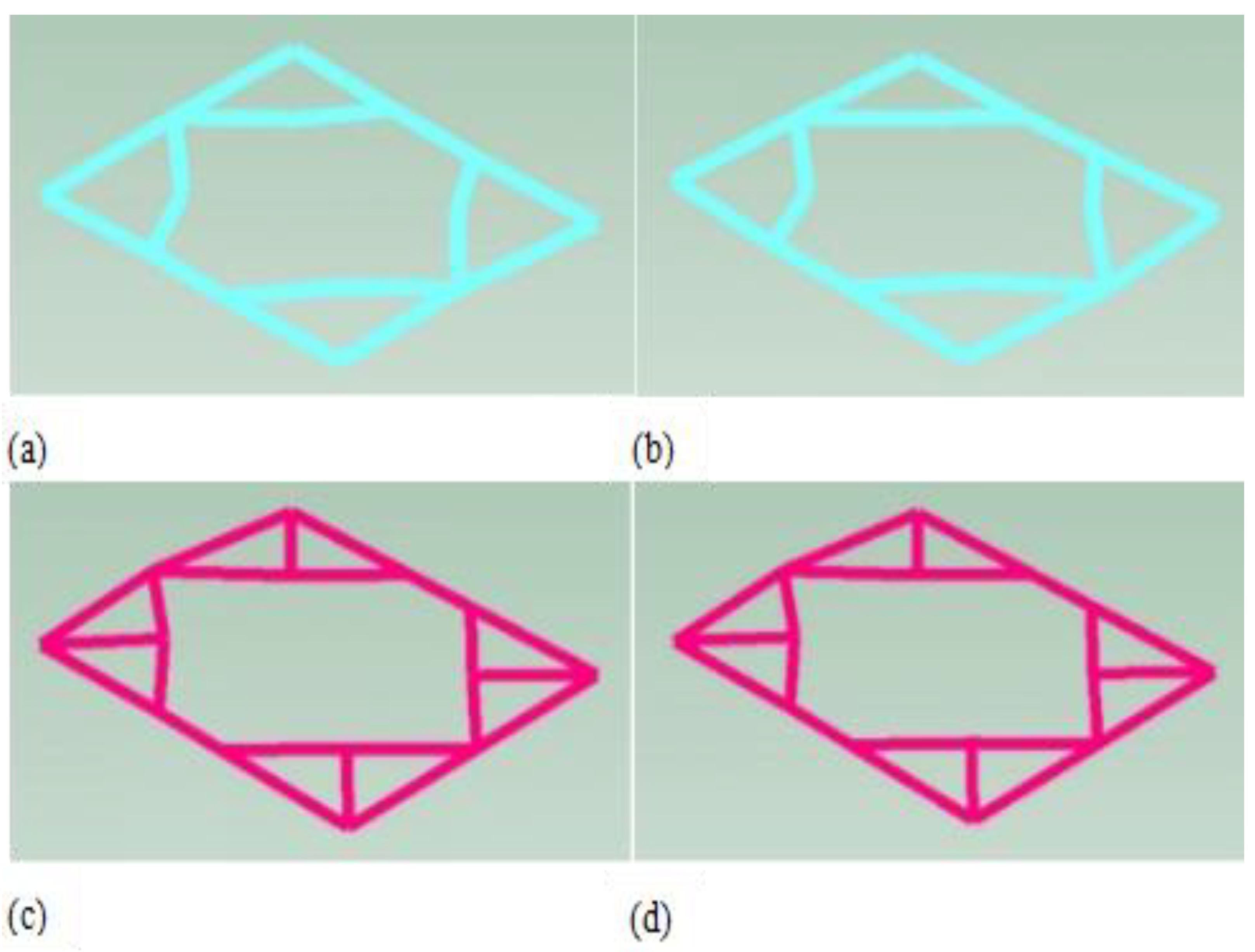

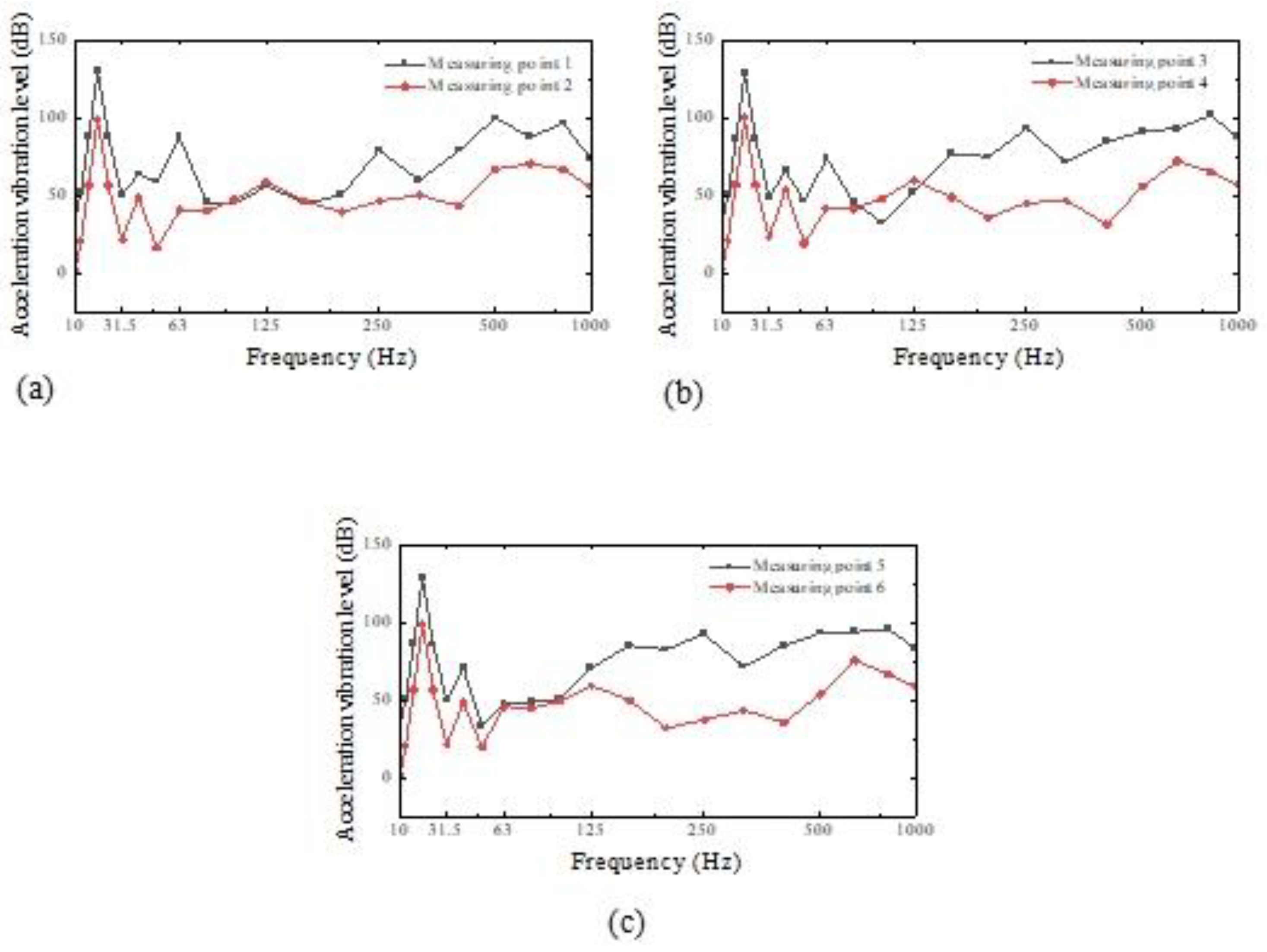

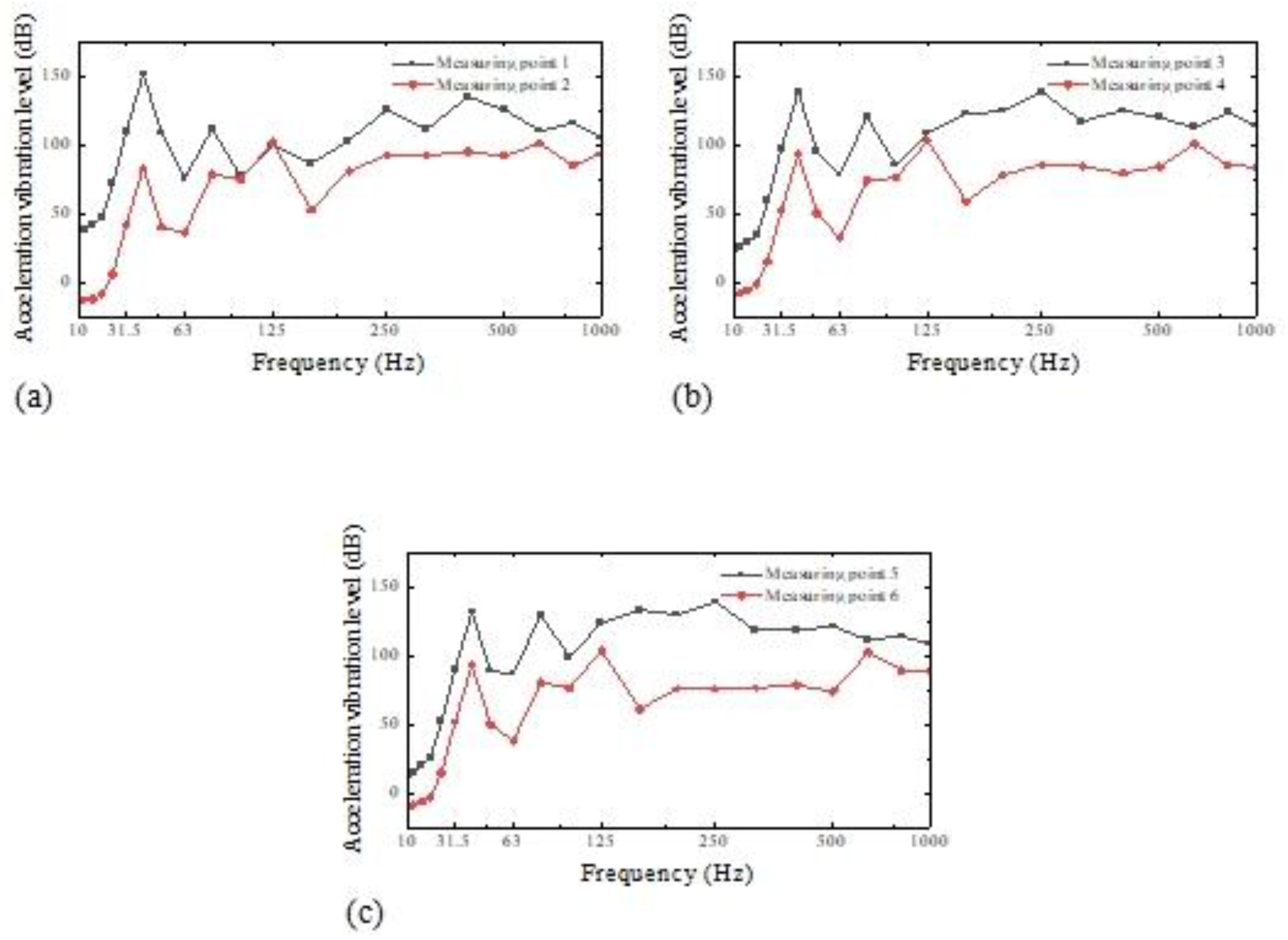

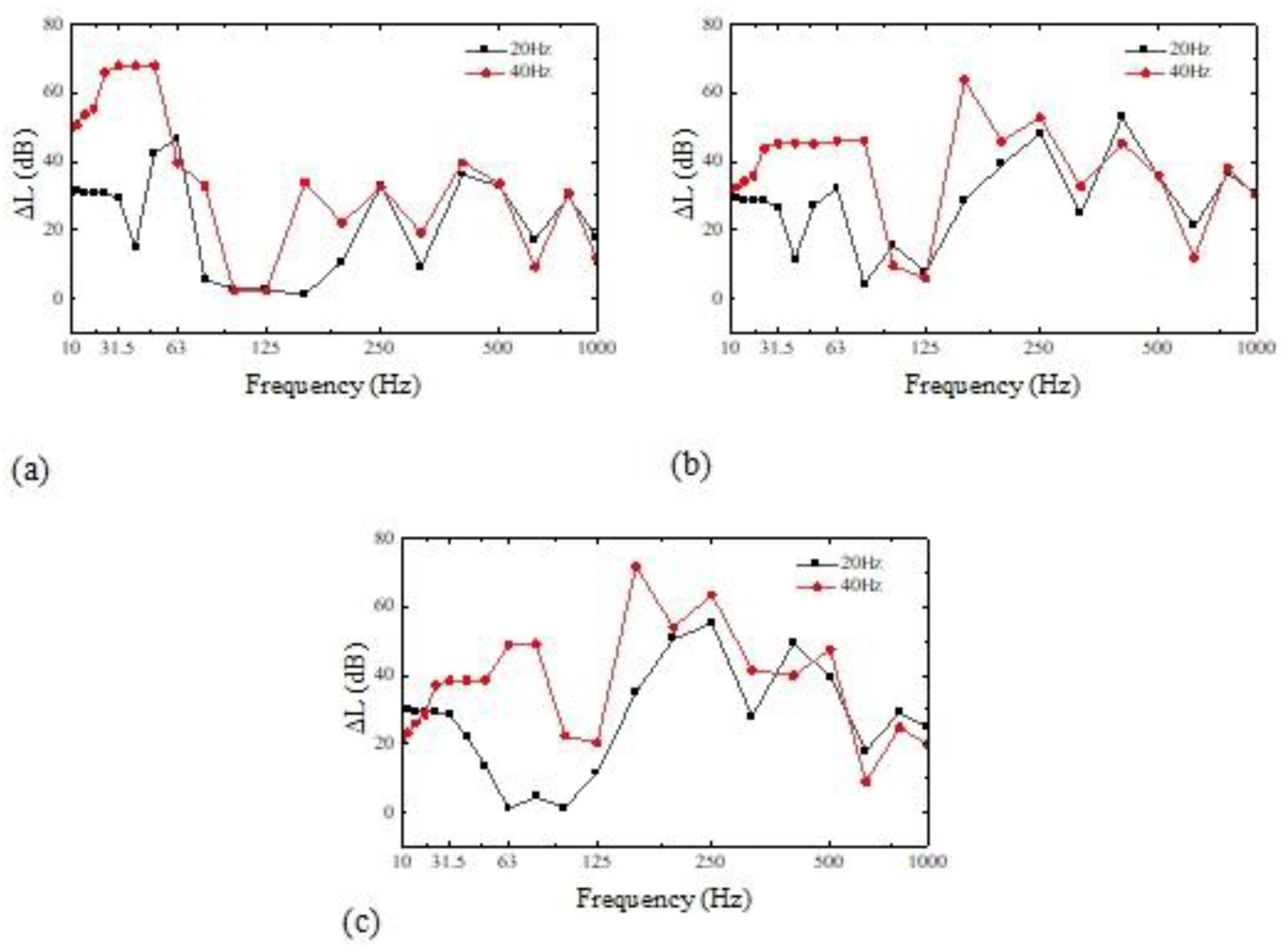

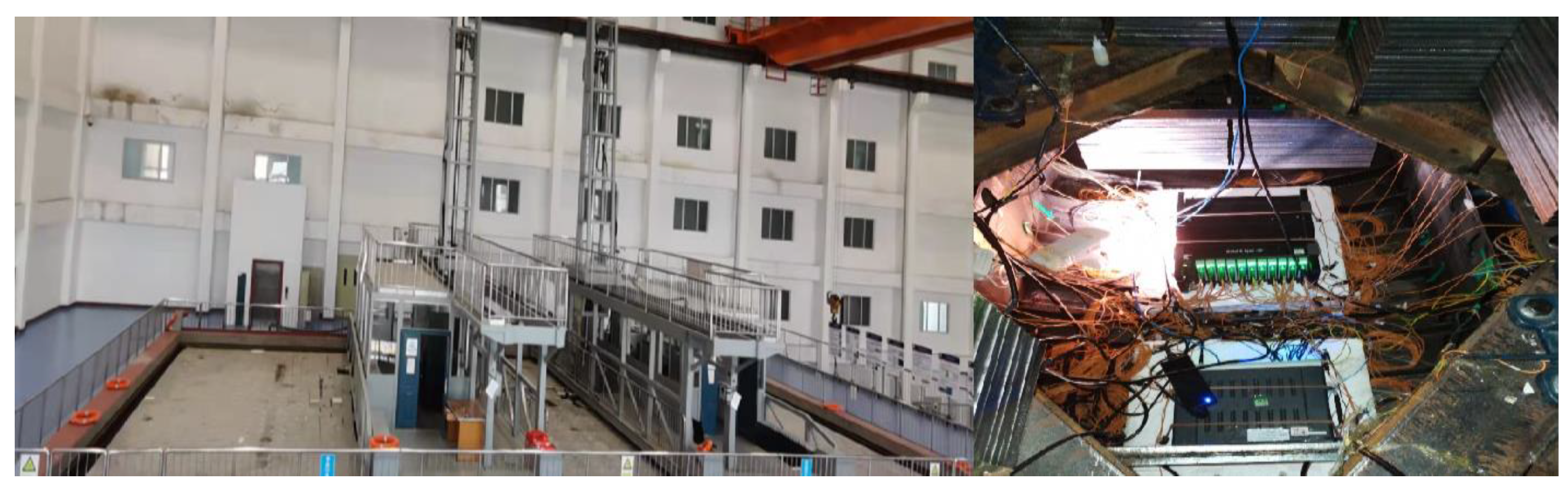

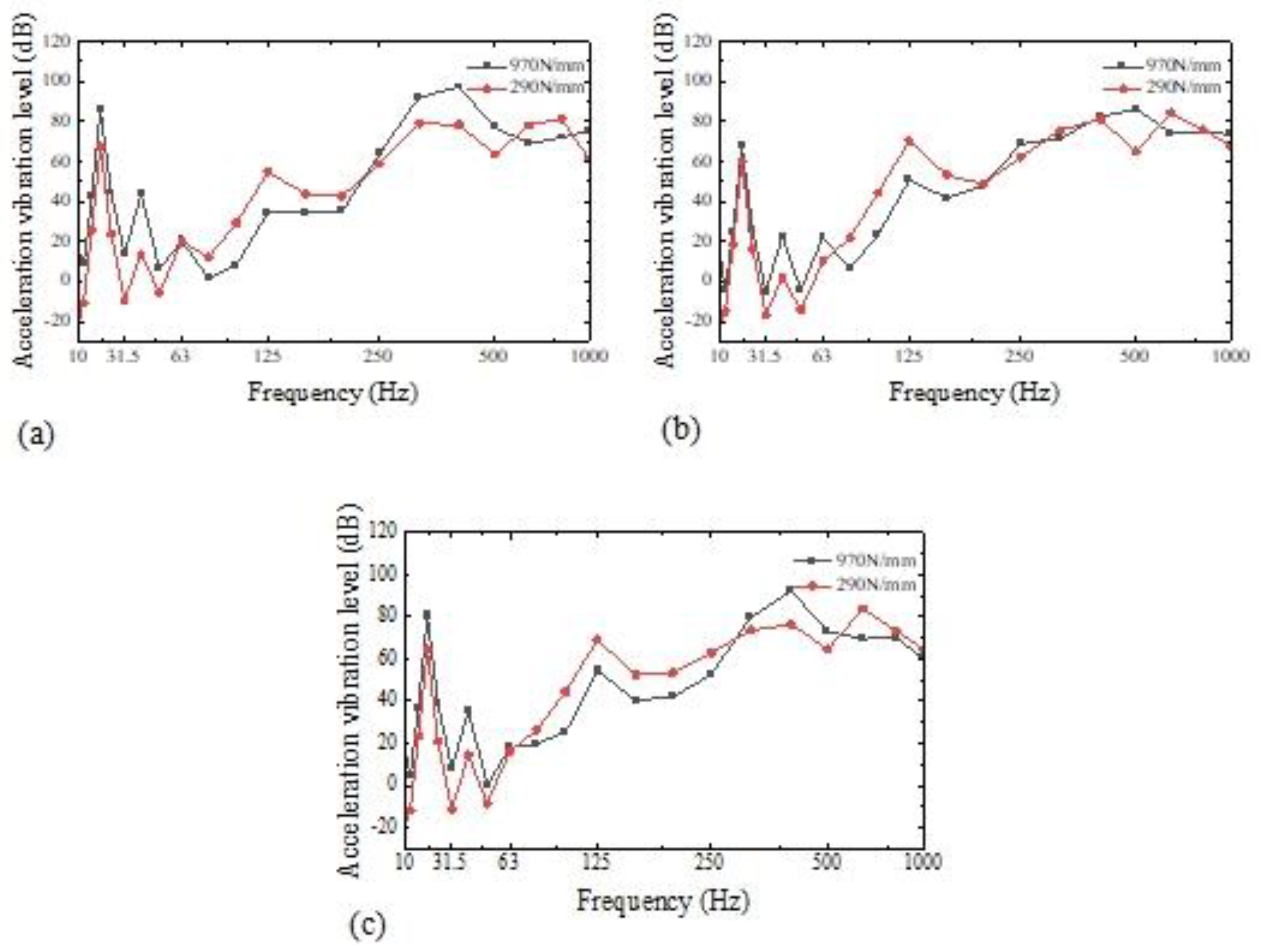

31] used ABAQUS finite element software to perform a modal analysis on a carbon fiber-reinforced plastics truss structure to enhance vibration isolation performance. The differences in acceleration vibration levels under various stimulation sources were investigated by constructing a floating raft isolation system experiment platform. Superior vibration isolation effects were attained. According to the literature, a brand-new active-passive analytical model for floating rafts was created [

32]. Numerically calculating the control effectiveness obtained for various control types led to some promising computational results, which may also be used as a guide when designing floating raft systems. A floating raft frame was created [

33], Using Abaqus software, modal analyses of several material frames were conducted, and the results were compared with modal tests based on vibration modal theory. According to the research, it is found that the steel floating raft frame has a lower frequency and damping ratio than the carbon fiber floating raft frame, which makes the vibration absorption effect better at low frequencies.

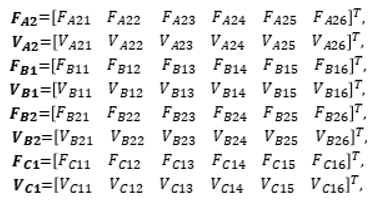

(1)

(1)