1. Introduction

In any physical systems there are fluctuations. If the temperature

T is low, this is due to the quantum nature of its constituents. When

T increases, temperature fluctuations set in and become dominant. If the fluctuations are mediated by massless excitations that can freely proliferate, they lead to long ranged interactions, called fluctuation induced forces, between any two bodies immersed in such a medium. The currently most prominent example of a fluctuation-induced force is the one due to quantum or thermal fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, leading to the so-called QED Casimir effect, named after the Dutch physicist H.B. Casimir. In 1948 he first realized that in the case of two perfectly-conducting, uncharged, and smooth plates parallel to each other in vacuum at

, these fluctuations lead to an

attractive force between them [

2]. Thirty years after Casimir’s publication, Fisher and De Gennes [

3] showed that a very similar effect exists in critical fluids, today known as the critical Casimir effect. Depending on the boundary conditions imposed on the surfaces bounding the system, the Casimir force can be bot

attractive and

repulsive. A summary of the results available for this effect can be found in the recent reviews [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Naturally, the effect takes place only in finite systems. Thus, the description of the critical Casimir effect is based on finite-size scaling theory [

8,

9,

10]. The effect is more than a theoretical construction within statistical mechanics—the critical Casimir effect has been observed experimentally [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] in a variety of systems.

Within equilibrium statistical mechanics, thermodynamic ensembles are described in terms of specific thermodynamic potentials, through which thermodynamic parameters control the macroscopic behavior of considered systems. One can define a fluctuation induced force in any of them. This can be motivated by the physical situation. The ensembles are, normally, thermodynamically equivalent in the bulk limit. The fluctuation induced forces are defined, however, in a system with at least one finite dimension, i.e., within finite systems. Thus, the forces defined in two different ensembles for any given model shall be expected to be, in principal, with a different behavior - at least as a function of the characteristic finite size

L and the temperature

T. Recently this has been demonstrated explicitly in the example of the fluctuation induced force in a system with fixed value of the total magnetization [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The corresponding fluctuation induced force has been defined in [

16] in the case of an Ising chain and called Helmholtz force. In [

16,

17,

18,

19] it has been shown that the behavior of the Helmholtz force is quite different from that of the Casimir force. This has been done for periodic, antiperiodic, Dirichlet boundary condition, as well as for the Ising chain with a defect bond. In the current article we continue the study of the ensemble dependence of the fluctuation induced forces in the example of the Nagle-Kardar model. More specifically, we consider the Helmholtz force in a model Hamiltonian [

20,

21,

22] with two competing interactions: the Ising model on a chain with “ nearest-neighbor" and with “infinitesimal equivalent-neighbor" interactions between the spins. This is also known as the Nagle-Kardar model (for reviews see [

23,

24,

25]). The Hamiltonian of the model is:

where the following notations:

,

are used. Given the symmetry of the problem it suffices to fix magnetization

.

The first term on the right hand side of (

1) describes the Ising model with short-ranged interactions between nearest neighbors on a spin chain with

periodic boundary conditions and with

with interaction constant

. The second term is the equivalent-neighbor Ising model with infinitesimal long-ranged interaction between spins characterized by

. With

one obtains the so-called Husimi-Temperley model [

26,

27]. In the case considered here, the nearest-neighbor interaction is either ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic, i.e.,

or

, while the long-range interaction is always ferromagnetic, i.e.,

. It can be shown that when

there is no long-range order in the bulk system at any finite temperature.

Initially, this model was introduced within the grand canonical ensemble, in the presence of an external field

h, by Baker in 1969 [

20]. Actually, subsequent considerations of the model have been mainly carried out in the grand canonical ensemble. The seminal contributions of Nagle [

21] and Kardar [

22] demonstrated that the model is instructive as a means to analyze complicated phase diagrams and crossover phenomena arising from the competition between ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions. A wide range of physical and mathematical problems have been revealed by this simple long-range interaction reviving interest in one-dimensional Ising systems [

23,

24,

25,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], which has proven to be a fertile platform for the investigation of various generalizations of the competition between the antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic interactions [

39,

40,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In particular it has been shown that this simple system may well describe a number of interesting phenomena, including ensemble inequivalence [

34,

36,

49], negative specific heat[

34,

35,

36], ergodicity breaking [

34,

35,

36], long-lived thermodynamically unstable states [

34,

35], the prospect of analysis of different information estimators [

42] and the cooling process of a long-range system [

50]. The

bulk thermodynamic properties of the model have been actively studied in both the grand canonical [

21,

22,

30,

51] and the microcanonical ensemble [

25,

34,

35,

36,

47].

We are not aware of the behavior of the Nagle-Kardar model within the canonical ensemble (with fixed magnetization) having been reported in any research up to this time—even in the case of the bulk limit. Here we will discuss it in a finite chain in that ensemble subject to periodic boundary conditions.

We note that there are systems for which the statistical-mechanical ensembles are not equivalent, even in the thermodynamic limit. One example is the case of systems with non-additive interactions [

52,

53]. The second term in Eq. (

1) is an example of such an interaction. As we will see, it leads to as non-convex behavior of the Helmholtz free energy in the canonical ensemble. In this case there are stable, metastable and unstable states in the system. For the Nagle-Kardar model we will determine their position in the

plane.

We have derived the behavior of this system not only in the thermodynamic limit, in which its phase diagram is highly non-trivial—see below—but also when the system is finite, in which case the fluctuation-induced critical Helmholtz force (HF) can be defined and studied.

The structure of the article is as follows. We define the model in

Section 2. In

Section 3 we determine the phase diagram of the model. Then,

Section 4 contains our analysis of the stable, metastable and unstable states of the system and the determination of their positions. The behavior of the Helmholtz force is elucidated in

Section 5. The article ends with a conclusion and discussion section, in

Section 6.

2. The Model in Canonical Ensemble

We start with the calculation of the canonical partition function

where

Obviously

Knowing the partition function for the short-range Ising model under periodic boundary conditions with fixed magnetization [

16], which equals the sum that remains in Eq. (

4), it is easy to determine the partition function

:

where

2 is the generalized hypergeometric function [

54]. From Eq. (

5) it immediately follows that the Helmholtz free energy density of the model takes the form:

with the Helmholtz free energy density of the one-dimensional Ising model:

In the thermodynamic limit

with

we obtain for the bulk case

where [

17]

Let

minimize the Helmholtz free energy given by Eq.(8), i.e.

. Then this, from now on to be referred to as the equilibrium magnetization

, is given by the solution of the equation

Explicitly, one has

For any fixed values of

and

the free energy attains an extremum as a function of

m, in that it is a minimum, at

when the system is in unordered phase; in the ordered phase this equation has more than one solution. In that case, at

the free energy usually attains a maximum there and possesses two minima at

. As we will see below, the system considered here also exhibits a tricritical point. There, the free energy, Eq. (

8), shows three equally deep minima, one of which is at

.

We note that

corresponds to the analogous solution for magnetization

of the same model in the grand canonical ensembles with

—see Eq. (7) in [

1]; there the actual magnetization of the system indeed is

.

4. On the Stability of the System

In the current section we will study the region of the stability of the states of Nagle-Kardar model within the canonical ensemble. Let us remind that in the current model any state is characterized by coordinates.

According to thermodynamics

and

Obviously, the system will be stable if

The last inequality implies that, when it is valid, the free energy is a

convex function of

.

From Eq. (

8) it follows that the above condition is equivalent to

Obviously, the last can be rewritten as

The second inequality, concerning the Ising model, is fulfilled for all values of

and

m. The first, however, is

not. For any nonzero finite value of

it will be a

region, for which the system will be unstable. Explicitly, one has

The above expression determines the equation of the "spinodal surface" of the magnetization

, called "spinodal magnetization", as a function of

and

Obviously, the spinodal surface indicates onset of metastability. Let us note that the susceptibility in the grand canonical ensemble, since it represents there the mathematical dispersion of the sum of spins, is

always positive. Thus, in the regions, where Eq. (

17) is violated, CE and GCE for the Nagle-Kardar model are

not equivalent, even in the thermodynamic limit.

For a few limiting cases one can easily obtain explicit solutions for

. For example, setting in Eq. (

20)

, we obtain the well-know result [

52] for the Husimi-Temperley model [

26,

27]

For

the solution of Eq. (

20) can also be directly found. It is

One can also immediately show that when

, formally the same solution of the above equation for

, up to the leading order, is also valid (but for other restrictions over

and

).

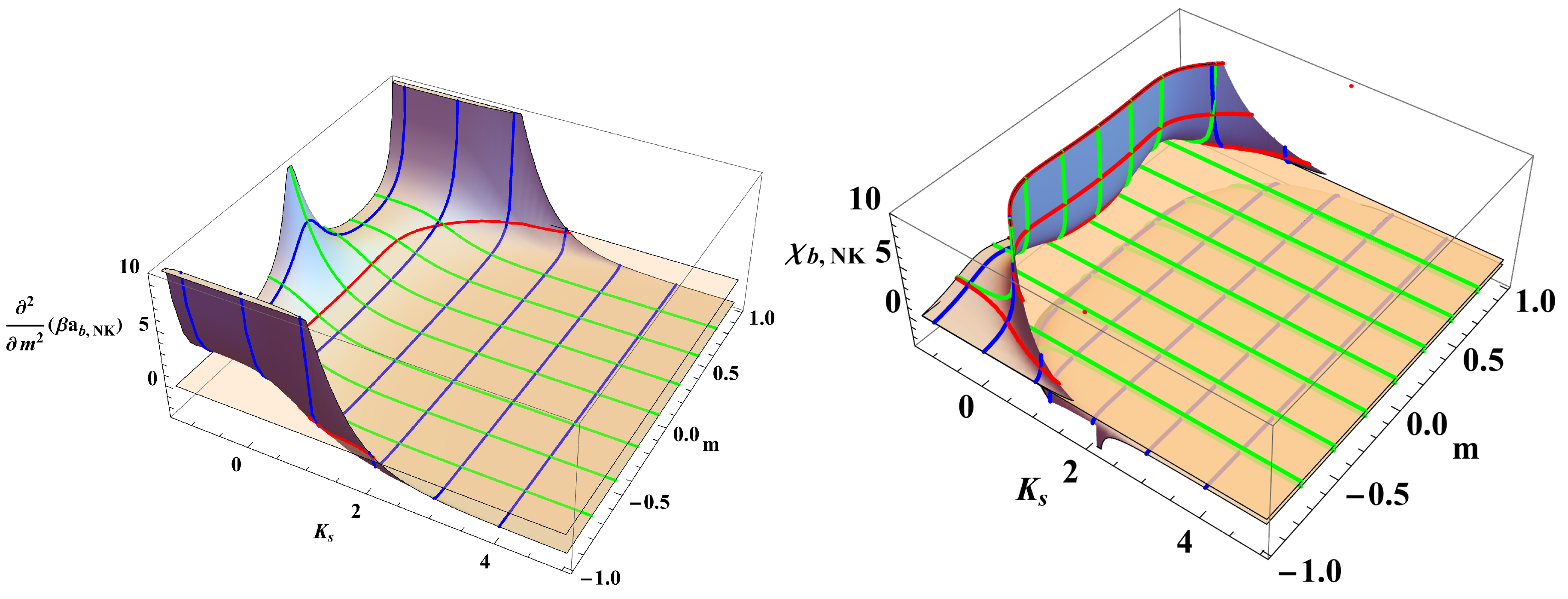

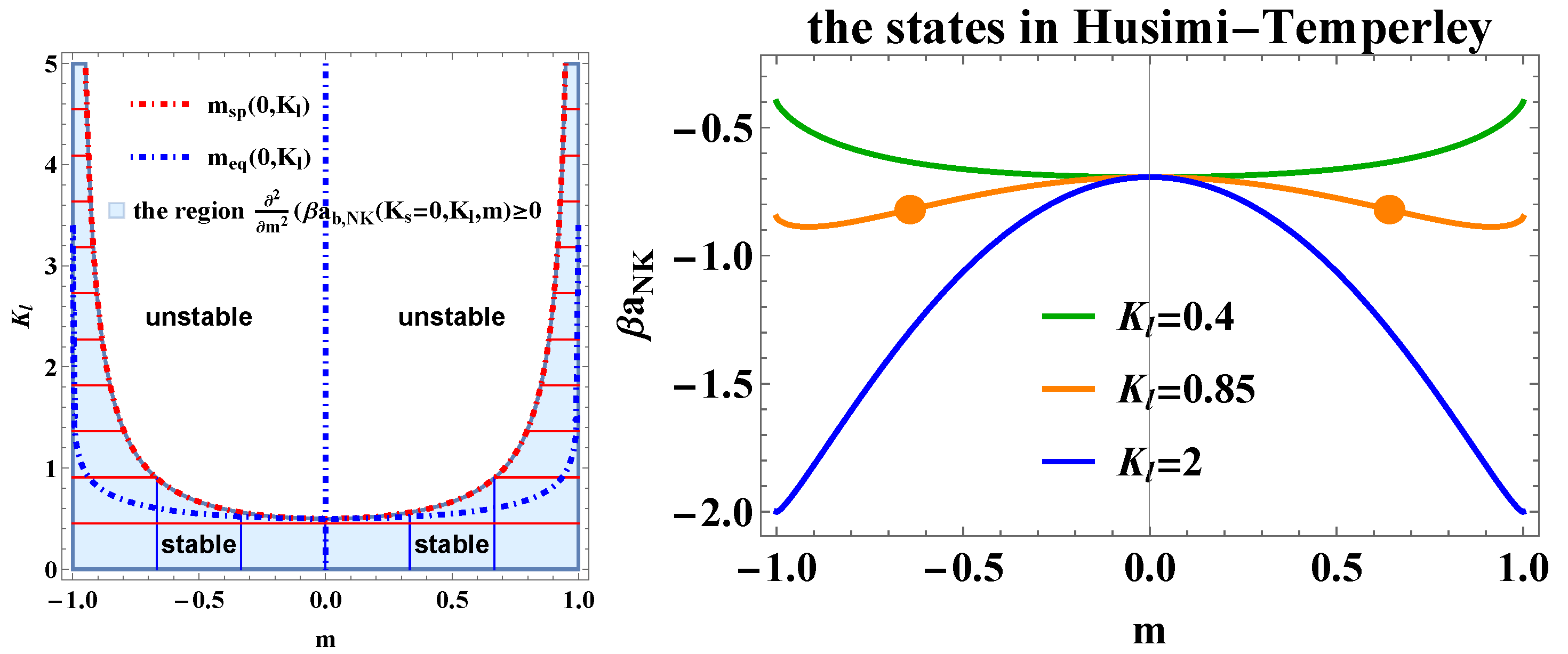

The regions of stability in the system are visualized in

Figure 1 for

.

Figure 2, left, visualizes the spinodal surface and the region below it, for which the system is with positive second derivative of the free energy with respect to

m which embraces the regions of thermodynamically stability. Above this region everywhere where

<0 the system is thermodynamically unstable for the corresponding

. The right panel shows the cross sections of this region with

planes at given values of

, for

and

.

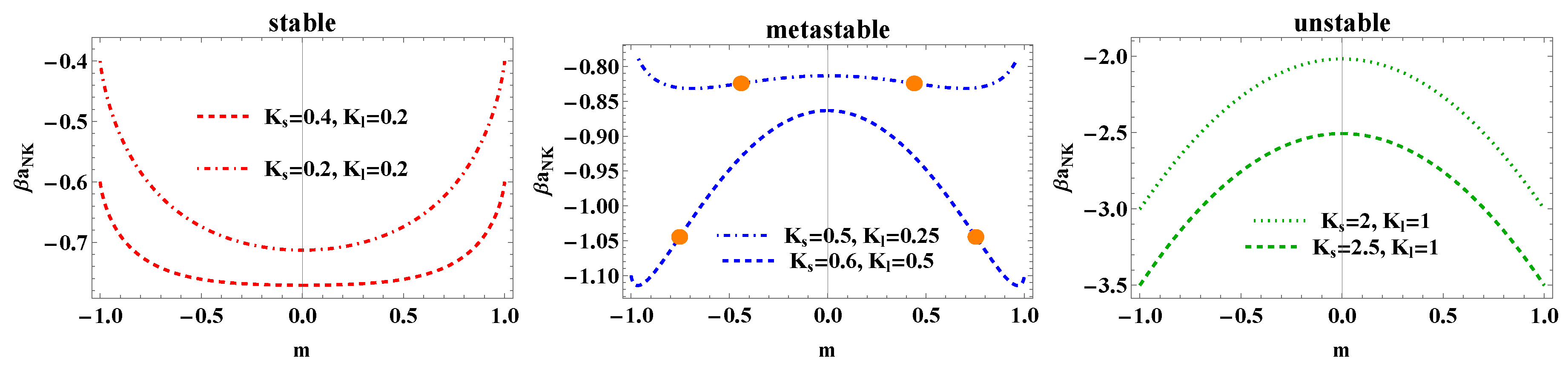

Figure 3 shows the behavior of the bulk free energy as a function of

m for the regions where system is stable, with free energy being convex, metastable - with a mixture of convex and concave regions of the free energy, or unstable, where the free energy is concave. For convenience of the reader the comparison with the known results [

55] for the Husimi-Temperley model, for which

, is shown in

Figure 4.

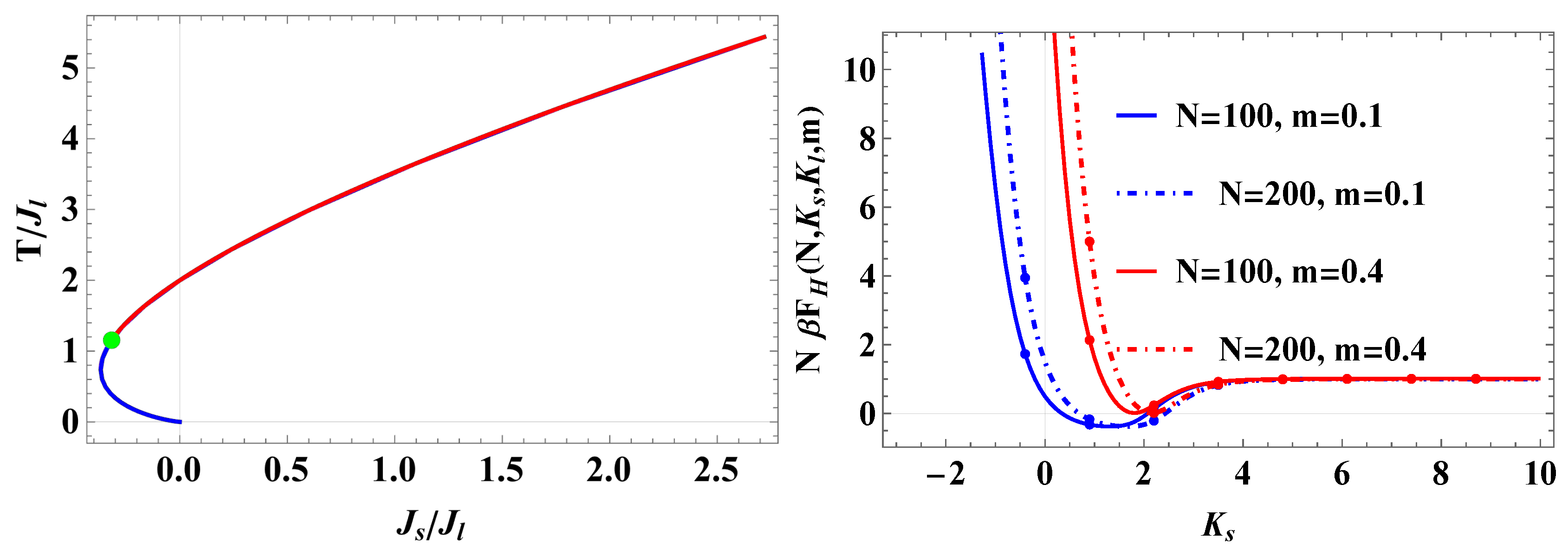

Figure 1.

Left panel. The figure illustrates the behavior of

in the

plane. The blue and green lines are the isolines of

and

m, respectively. The red line shows the positions of the zeros of

- i.e., it position the horisontal cross section of the spinodal surface - see below Eq. (

20). Below the horizontal surface that passes through this red line the system is

.

Right panel. The behavior of the bulk susceptibility

in the

plane for

. The area in

plane below the reddish surface belongs to the set of thermodynamic variables with

.

Figure 1.

Left panel. The figure illustrates the behavior of

in the

plane. The blue and green lines are the isolines of

and

m, respectively. The red line shows the positions of the zeros of

- i.e., it position the horisontal cross section of the spinodal surface - see below Eq. (

20). Below the horizontal surface that passes through this red line the system is

.

Right panel. The behavior of the bulk susceptibility

in the

plane for

. The area in

plane below the reddish surface belongs to the set of thermodynamic variables with

.

Figure 2.

Left panel The region in the space where the second derivative of the free energy of the system is non-negative is embraced by the figure presented. The upper surface of this reagion is given by the spinodal surface. Right panel The corresponding cross-sections of this region with planes at and are presented on the right panel. Their upper limiting lines are equal to , , and .

Figure 2.

Left panel The region in the space where the second derivative of the free energy of the system is non-negative is embraced by the figure presented. The upper surface of this reagion is given by the spinodal surface. Right panel The corresponding cross-sections of this region with planes at and are presented on the right panel. Their upper limiting lines are equal to , , and .

Figure 3.

The behavior of the Helmholtz bulk free energy

, see Eq. (

8), as a function of

m for specific values of the combination

and

for which the system is in a thermodynamically stable (leftmost) - with convex free energy, metastable (middle), or unstable (rightmost) states - for which the free energy is concave function. For the curves of the free energy im the middle panel (in blue) there are two regions:

i) region in which the free energy is concave (this is a stable region, it is about

and between the orange points; these points indicate the states at which the second derivative changes its sign) and

ii) another region where it is convex, i.e., the system is unstable (it is about the minimum of the free energy).

Figure 3.

The behavior of the Helmholtz bulk free energy

, see Eq. (

8), as a function of

m for specific values of the combination

and

for which the system is in a thermodynamically stable (leftmost) - with convex free energy, metastable (middle), or unstable (rightmost) states - for which the free energy is concave function. For the curves of the free energy im the middle panel (in blue) there are two regions:

i) region in which the free energy is concave (this is a stable region, it is about

and between the orange points; these points indicate the states at which the second derivative changes its sign) and

ii) another region where it is convex, i.e., the system is unstable (it is about the minimum of the free energy).

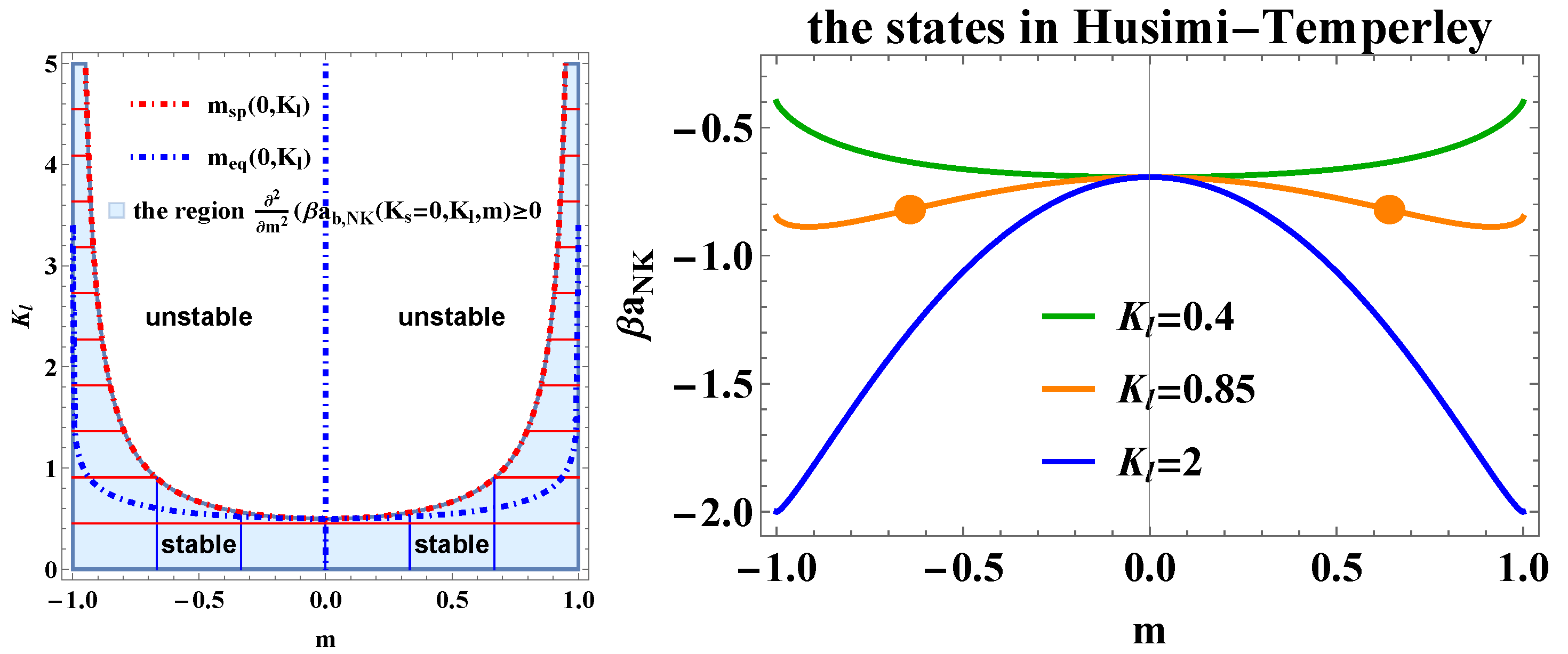

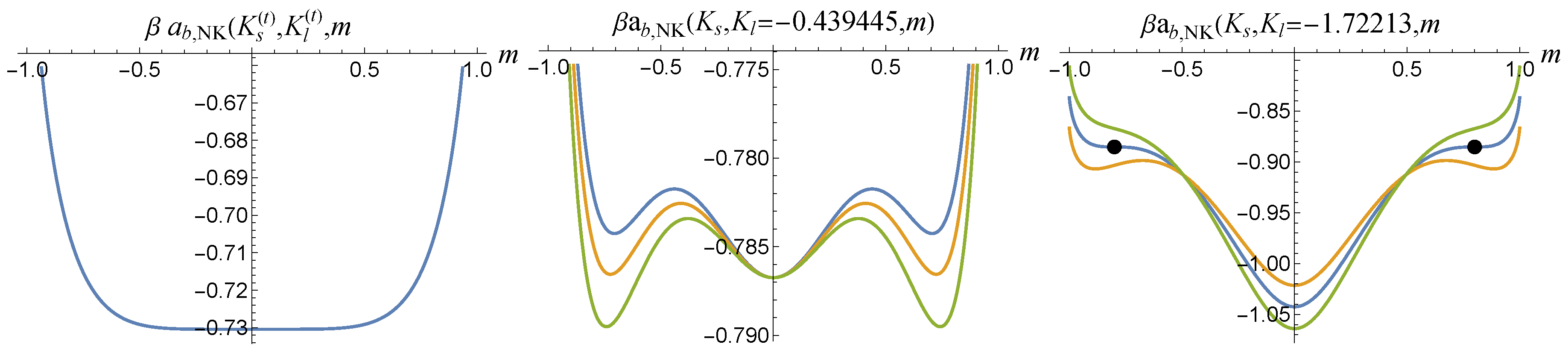

Figure 4.

Left panel The thermodynamically stable, metastable and unstable regions for Husimi-Temperley model, for which

. The blues region between the dot-dashed red spinodal line of

, determined by Eq. (

20) with

, and the dot-dashed blue line of equilibrium magnetization

, given by Eq. (

11) with

, is the region of

metastable states. The white region is the one with thermodynamically

unstable states. The part of the blue region below the metastable curve is a region of stable states.

Right panel The behavior of the free energy as a function of

m for given values of

, with

.The green line has a minimum only at

and the free energy is convex. That is why all states with given coordinates belonging to this curve are

stable. The orange curve has a maximum at

and two minima at

. The curve is concave in the middle, around

, and convex about

. Thus, on this line we have a mixture of stable and unstable states - metastable curve. The big orange dots indicate the states at which the second derivative changes its sign. The blue line has a maximum at

and minima at

. This curve is everywhere concave, i.e., all states belonging to it are unstable. The vertical dot-dashed blue line on the left panel represents the solution

. It is an extremum of the free energy, but it is not always its minimum — see the right panel.

Figure 4.

Left panel The thermodynamically stable, metastable and unstable regions for Husimi-Temperley model, for which

. The blues region between the dot-dashed red spinodal line of

, determined by Eq. (

20) with

, and the dot-dashed blue line of equilibrium magnetization

, given by Eq. (

11) with

, is the region of

metastable states. The white region is the one with thermodynamically

unstable states. The part of the blue region below the metastable curve is a region of stable states.

Right panel The behavior of the free energy as a function of

m for given values of

, with

.The green line has a minimum only at

and the free energy is convex. That is why all states with given coordinates belonging to this curve are

stable. The orange curve has a maximum at

and two minima at

. The curve is concave in the middle, around

, and convex about

. Thus, on this line we have a mixture of stable and unstable states - metastable curve. The big orange dots indicate the states at which the second derivative changes its sign. The blue line has a maximum at

and minima at

. This curve is everywhere concave, i.e., all states belonging to it are unstable. The vertical dot-dashed blue line on the left panel represents the solution

. It is an extremum of the free energy, but it is not always its minimum — see the right panel.

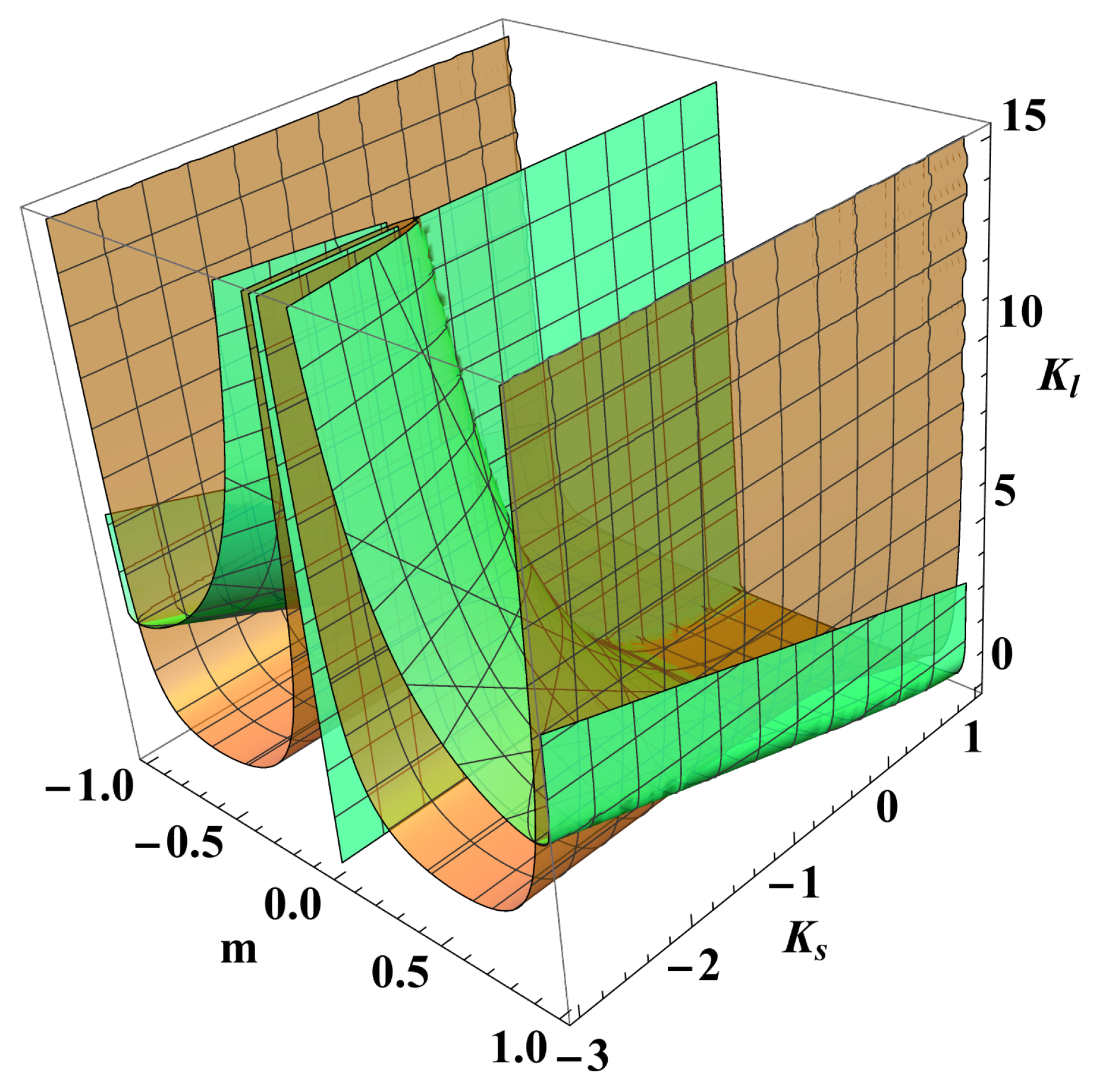

Figure 5.

The thermodynamically stable, metastable and unstable regions for Nagle-Kardar model. The reddish surface is the spinodal one, see Eq. (

19), while the greenish surface is the equilibrium one, see Eq. (

11). The surfaces mutually penetrate into each other. The region above the two surfaces is the one with unstable states, the one below the two - of stable states, while inbetween them embraces the metastable ones. This figure is the analogy of

Figure 4, left panel, that visualizes the case of the much simpler Husimi-Temperley model.

Figure 5.

The thermodynamically stable, metastable and unstable regions for Nagle-Kardar model. The reddish surface is the spinodal one, see Eq. (

19), while the greenish surface is the equilibrium one, see Eq. (

11). The surfaces mutually penetrate into each other. The region above the two surfaces is the one with unstable states, the one below the two - of stable states, while inbetween them embraces the metastable ones. This figure is the analogy of

Figure 4, left panel, that visualizes the case of the much simpler Husimi-Temperley model.

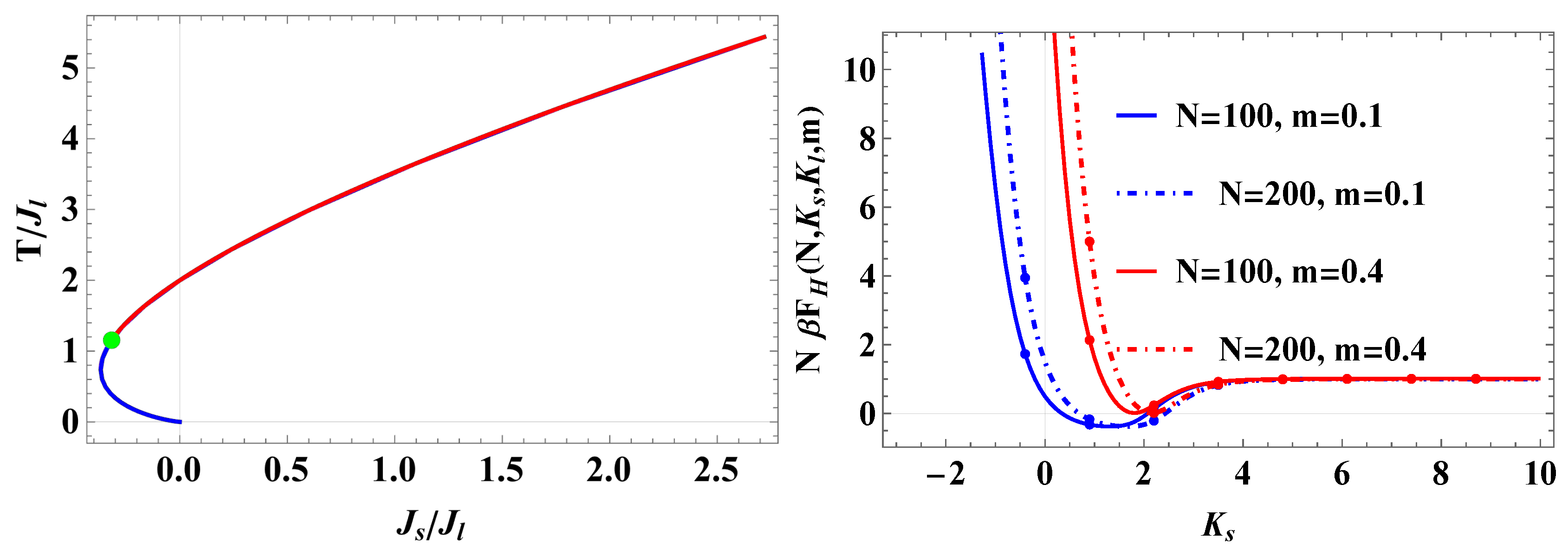

Figure 6.

Left panel The phase diagram in terms of the temperature. It is shown as a function of

and

. The red line represents a line of critical points with

, while the green point marks the tricritical point with

. The coordinates of the tricritical point in terms of

and

are

and in terms of

and

are

, and

. From this point, for

a line is starting at which three phases with the same free energy and magnetization

coexist. It is shown in blue. Above it at zero external field the magnetization is zero, while below it there are two phases with nonzero magnetization. That is why this blue line is the line of first-order phase transitions.

Right panel The figure illustrates the behavior of the Helmholtz force

as a function of

for fixed values of

N and

m. This function does

not depend on

. The function is repulsive and increases linearly for negative values of

. For large positive

the curves show the usual scaling behavior of the one-dimensional Ising model. For large positive

the curves show the usual scaling behavior of the one-dimensional Ising model - for details see [

7,

16,

17,

19].

Figure 6.

Left panel The phase diagram in terms of the temperature. It is shown as a function of

and

. The red line represents a line of critical points with

, while the green point marks the tricritical point with

. The coordinates of the tricritical point in terms of

and

are

and in terms of

and

are

, and

. From this point, for

a line is starting at which three phases with the same free energy and magnetization

coexist. It is shown in blue. Above it at zero external field the magnetization is zero, while below it there are two phases with nonzero magnetization. That is why this blue line is the line of first-order phase transitions.

Right panel The figure illustrates the behavior of the Helmholtz force

as a function of

for fixed values of

N and

m. This function does

not depend on

. The function is repulsive and increases linearly for negative values of

. For large positive

the curves show the usual scaling behavior of the one-dimensional Ising model. For large positive

the curves show the usual scaling behavior of the one-dimensional Ising model - for details see [

7,

16,

17,

19].

For examples of the behavior of the bulk Nagel-Kardar Helmholtz free energy when there is the possibility of a first order phase transition, see

Figure 7.

6. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In the current article we studied the behavior of the Nagle-Kardar model in an ensemble with conserved magnetization: the canonical ensemble, or CE. As explained in the introduction, this model has bee extensively studied in the grand canonical (with fixed external field) and in microcanonical ensemble. The current article, as far as we are aware about, is the only one that clarifies its behavior in the CE. We determined the phase diagram of the bulk model—see

Figure 6. It turns out that it has the same second-oder phase transition line, ending at a tricritical point (we note that this line, using the Lambert

W function, can be obtained analytically, as explained in [

1]), but differs in its behavior below that point. Furthermore, it turns out that the bulk system has stable, metastable and unstable thermodynamically regions, while the model in the GCE possesses only stable states. Details about where as a function of

and

m these states are located are visualized in

Figure 1—

Figure 3. For

the Nagle-Kardar model coincides with the Husimi-Temperley model, the behavior of which has been studied in both the GCE and the CE and is well known as a function of the same parameters used in the current article. This is shown in

Figure 4. They are in a full agreement with the existing literature for this model. In addition to the bulk behavior, we have also studied the finite-size behavior of a Nagle-Kardar chain under periodic boundary conditions and determined the behavior of the Helmholtz fluctuation-induced force. The behavior of this force as a function of

for several fixed values of the number of particles in the chain is shown in the right panel of

Figure 6. Interestingly, it does not depend on

, i.e., on the long-ranged part of the interaction. This means that the force actually coincides with the corresponding force for the Ising model. Thus, the Nagle-Kardar model is characterized by different thermodynamic behaviors in GCE and CE, and, in addition—by different fluctuation induced forces—the Casimir force in GCE and Helmholtz force in CE.