Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

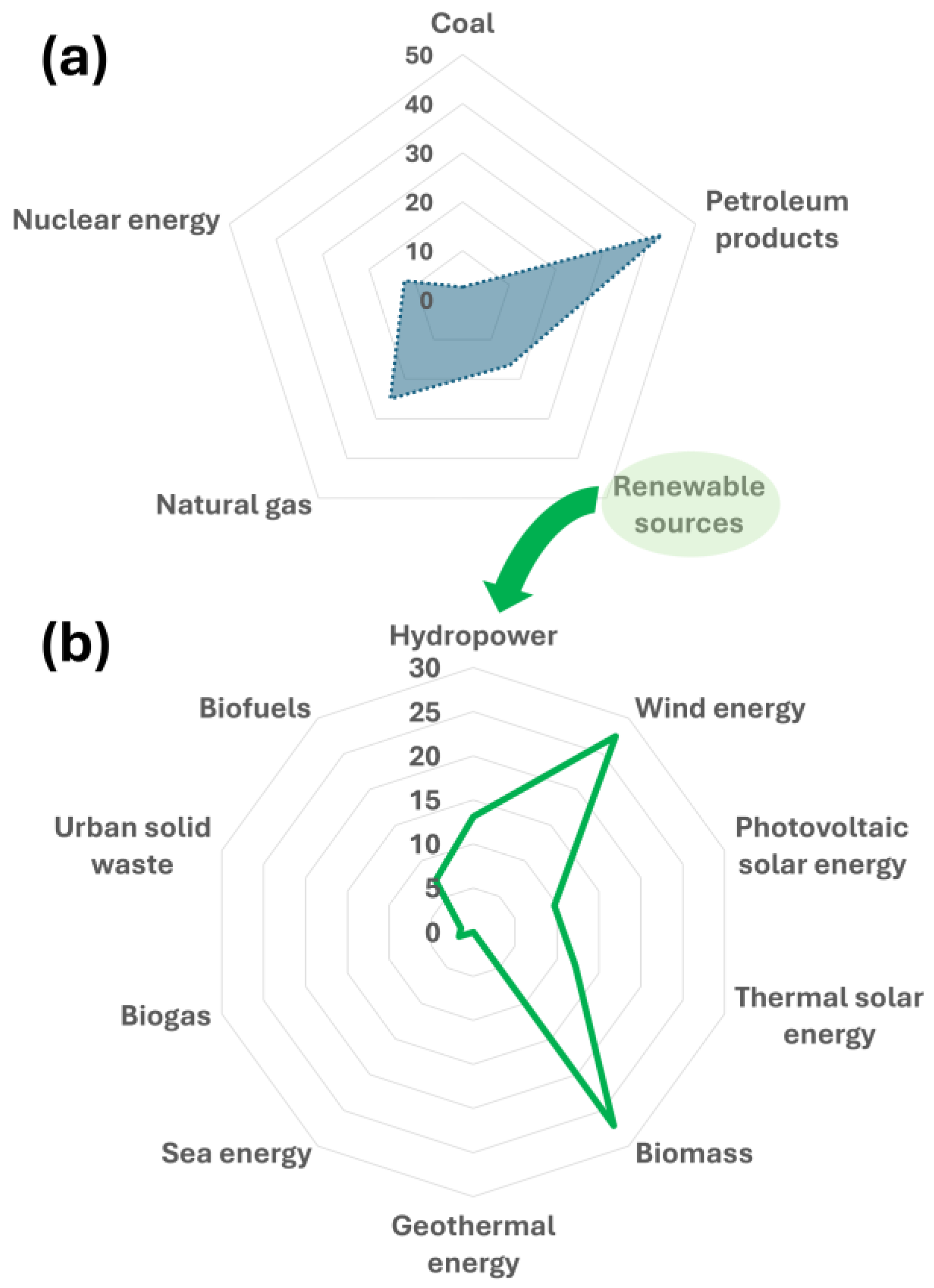

1. Introduction

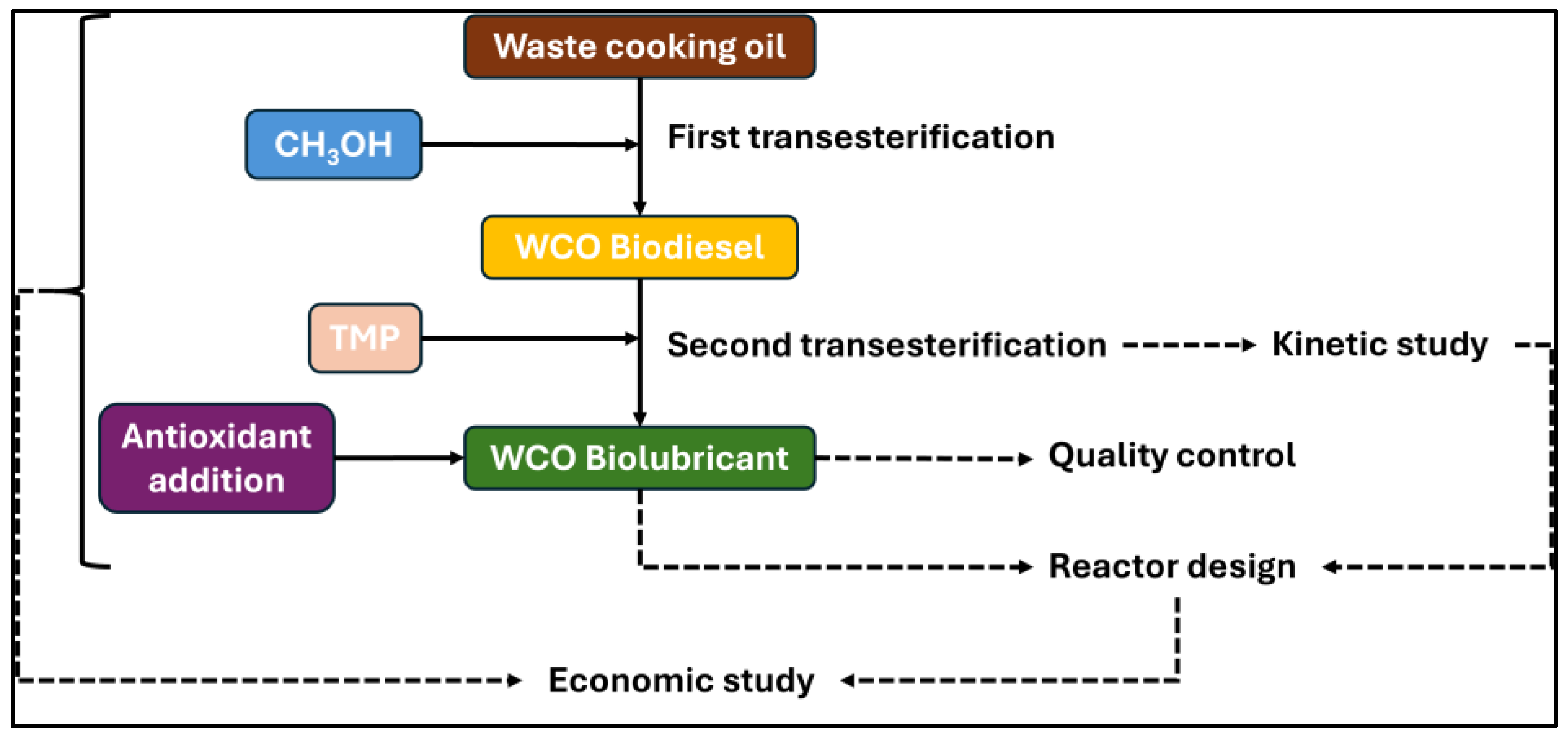

- Fatty acid methyl ester (biodiesel) production using a first transesterification with methanol and waste cooking oil, including its characterization according to the UNE-EN 14214 standard.

- Biolubricant production through double transesterification of fatty acid methyl esters with 2-ethyl-2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-propanediol, including an study about the effect of temperature, pressure and catalyst concentration on conversion yields. Also, the characterization of this biolubricant was carried out.

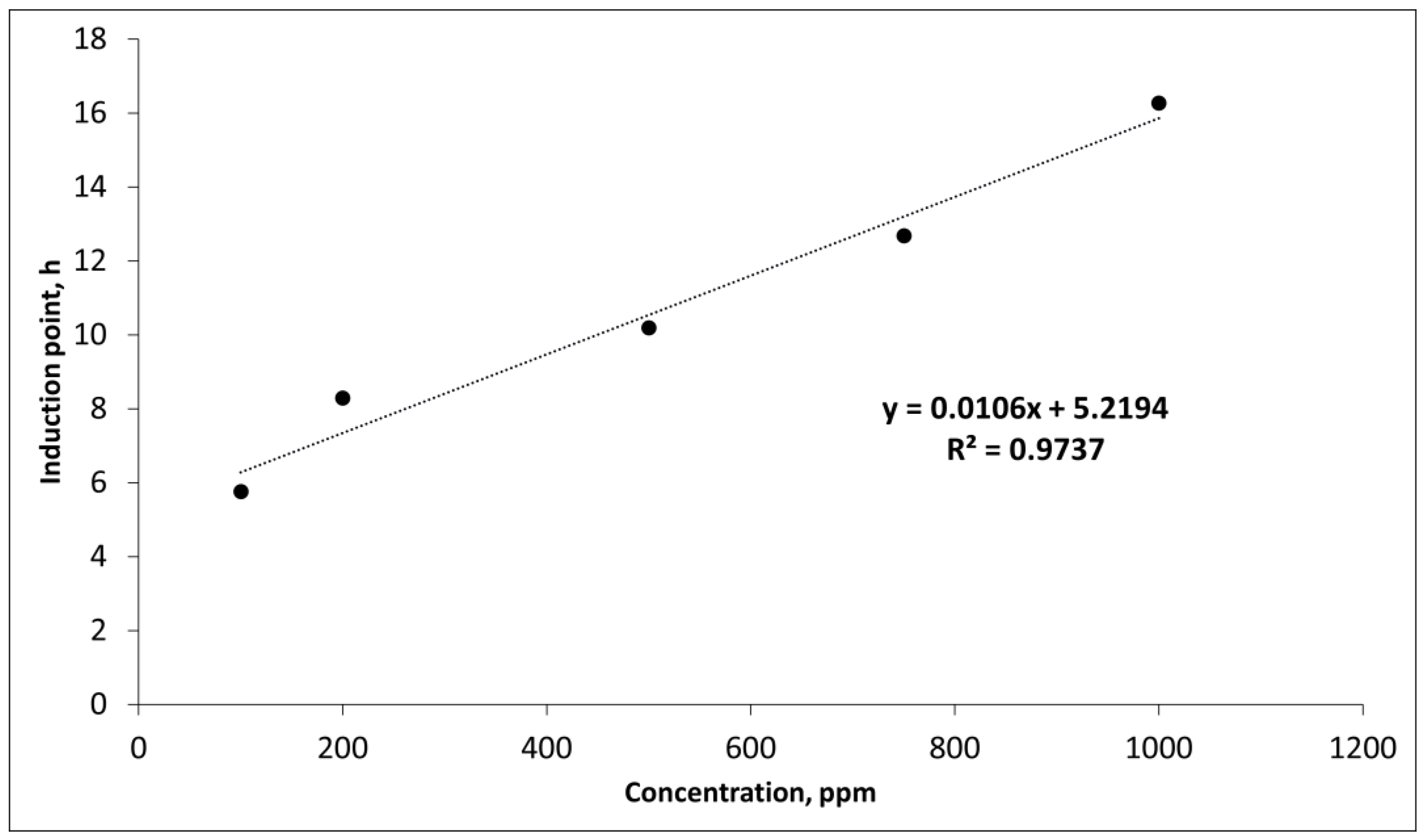

- Improvement of oxidation stability of biolubricants by adding an antioxidant (TBHQ).

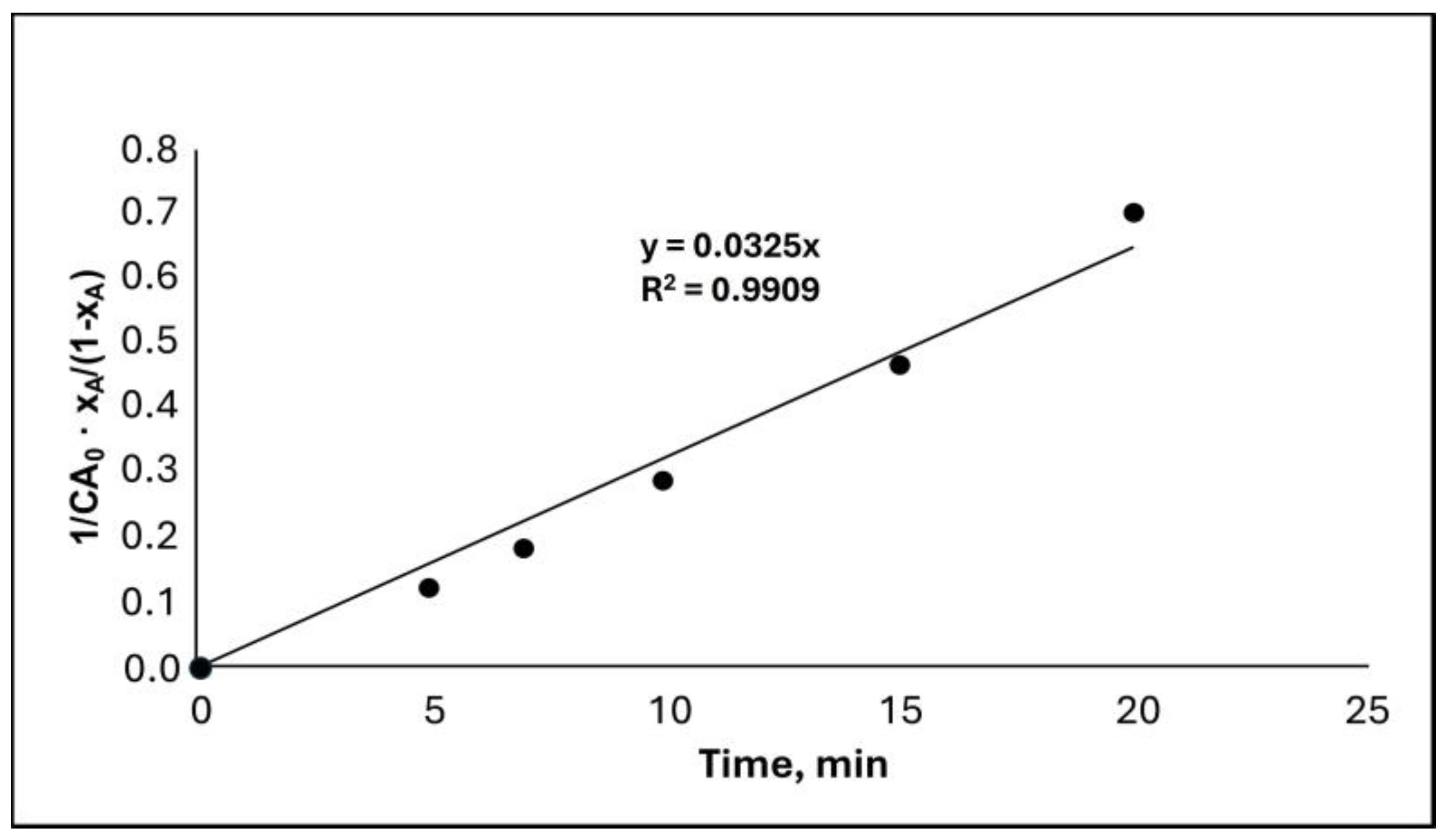

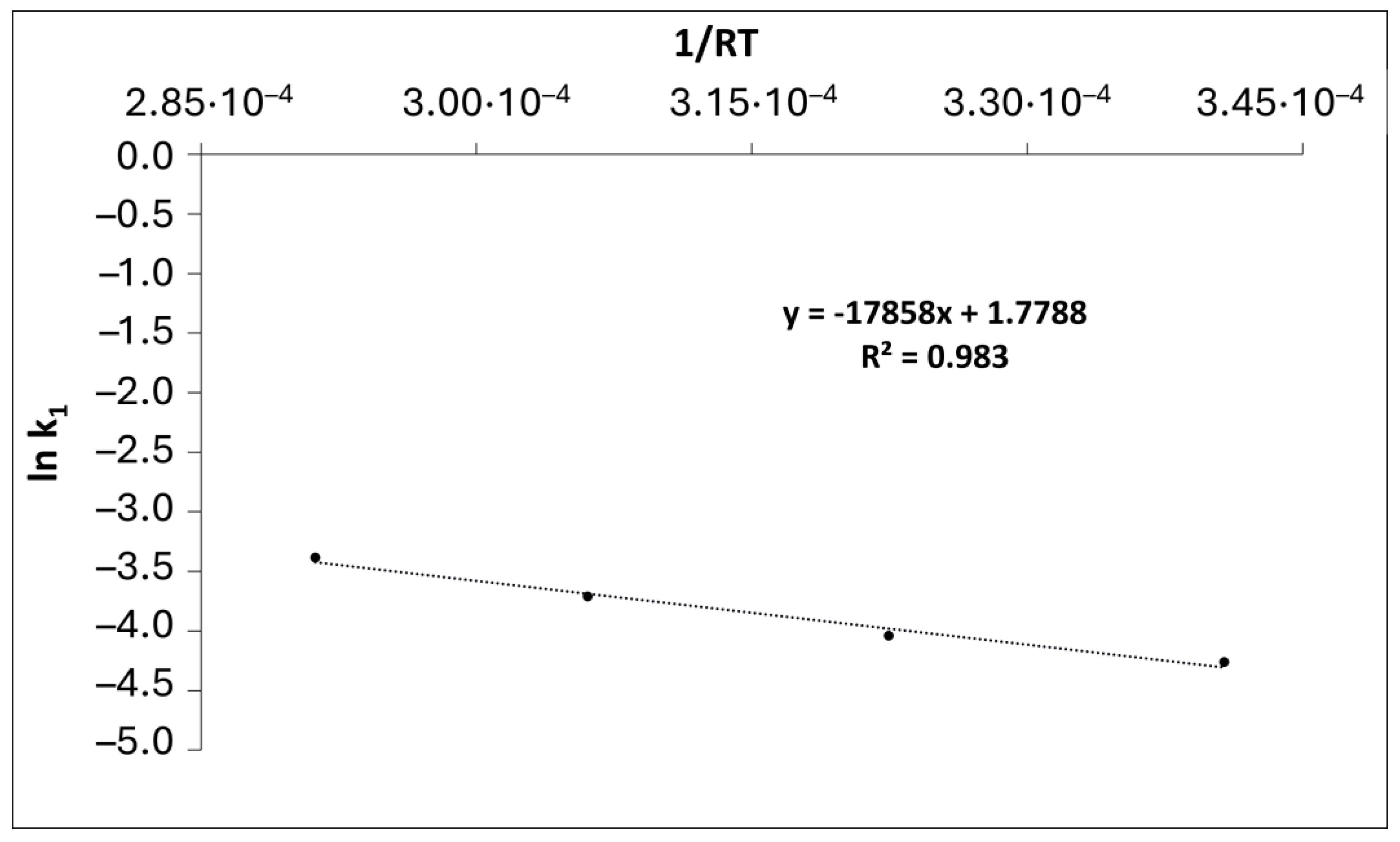

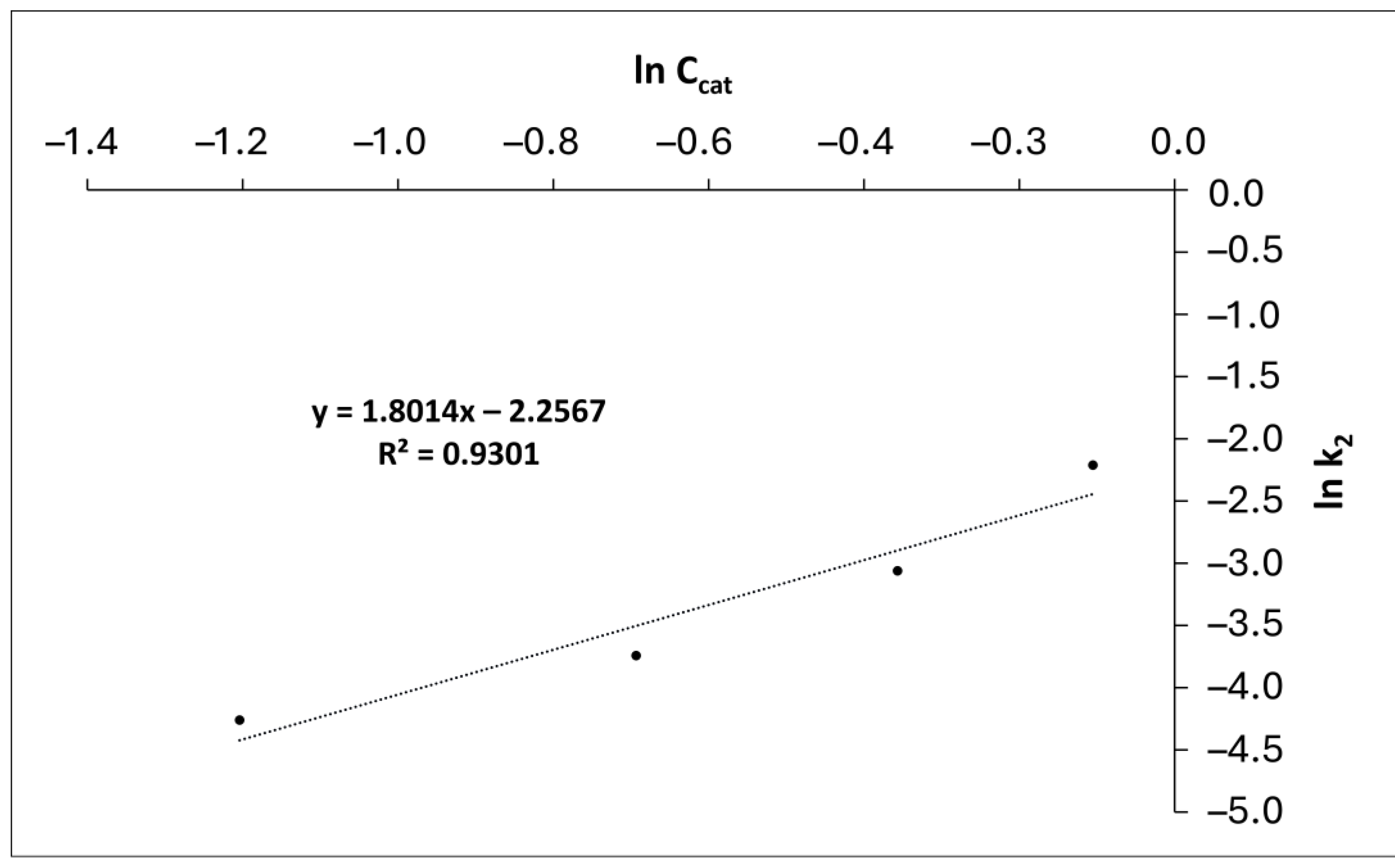

- Kinetic study of the second transesterification of FAMEs.

- Preliminary design and economic study of an industrial plant for biolubricant production from waste cooking oil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Waste cooking oil

2.2. Biodiesel and biolubricant production

2.3. Biodiesel and biolubricant characterization

2.4. Antioxidant addition

2.5. Kinetic study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. WCO-FAME characteristics

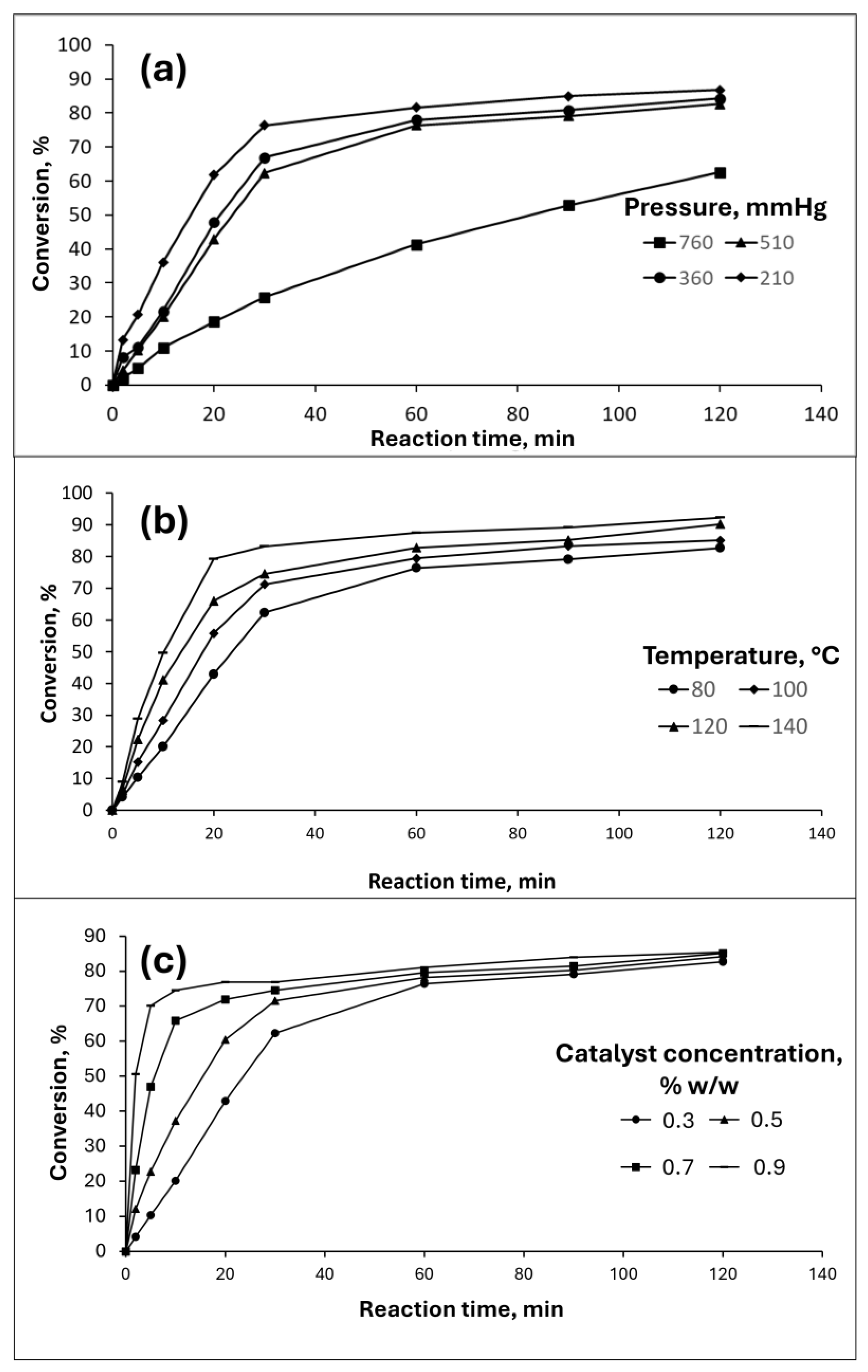

3.2. Effect of pressure, temperature and catalyst concentration on WCO-TMP production

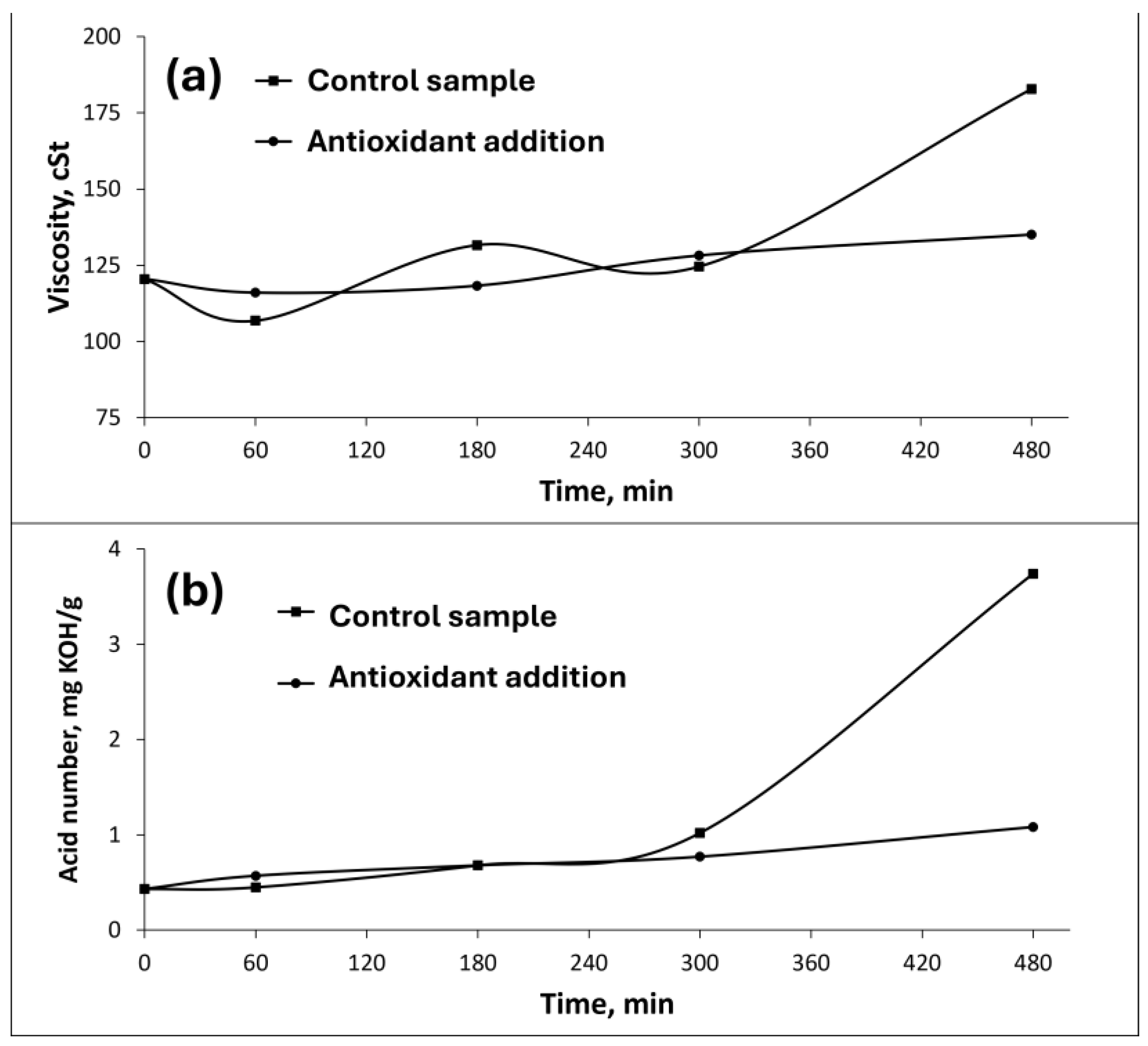

3.3. WCO-TMP and TBHQ addition

3.4. Kinetic study

3.5. Industrial equipment, reactor design and economic study

3.5.1. Preliminary approach

3.5.2. Main steps and equipment

| Step | Process/equipment | Details |

|---|---|---|

| WCO supply and preconditioning | Shipment (tank trucks), filtering and storage in tanks | For WCO and TMP, the steel tanks are used, for methanol and sodium methoxide, intermediate bulk containers (HDPE) were used. |

| Pumping | Pump system | Allows the introduction of WCO from tanks to the batch reactor |

| Steam generation | Electric steam generator |

Provides steam to the jacketed batch reactor to heat the system at 60 ˚C |

| 1st transesterification | Jacketed batch reactor |

WCO and methanol are mixed in the reactor, introducing the catalyst. |

| First separation (decantation) |

Jacketed batch reactor |

Once the previous step finished, the agitation system stopped, and the lower phase (containing glycerol) was removed and stored |

| Heating | Jacketed batch reactor and steam generator |

The steam generator provided saturated steam to the reactor at a suitable temperature for the second transesterification |

| 2nd transesterification | Jacketed batch reactor |

TMP and catalyst are added to FAMEs generated in the previous transesterification, providing steam to keep the isothermal regime of the reaction. Methanol and biolubricant are obtained as products |

| Vacuum | Vacuum system | Vacuum is used to promote the second transesterification and remove methanol, which is collected in containers |

| Purification | Pumping system and purifier | Once the reaction stops, the resulting biolubricant is cooled down and purified (removing moisture, particle and gas), placing the resulting biolubricant in the corresponding steel tank |

| Antioxidant addition | TBHQ supply | A suitable amount of TBHQ was added to WCO-TMP |

| Equipment | Size | Details |

|---|---|---|

| WCO container |

Volume = 2 m3; heigh = 2.8 m; diameter = 1.15 m; wall thickness = 1.2 mm |

The container (stainless steel) is oversized to ensure the collection of WCO |

| Methanol Container |

Volume = 0.6 m3; size = 1.2x0.8x1 m |

HDPE containers, a smaller container (V = 0.3 m3) is used for collection of methanol after vacuum capture |

| Sodium methoxide container | Volume = 0.3 m3; size = 1.2x0.8x1 m |

HDPE container to supply 100 L of catalyst on a daily basis |

| Glycerol container |

Volume = 0.6 m3; size = 1.2x0.8x1 m |

HDPE container to store 495 kg of glycerol obtained as by-product |

| TMP Container |

Volume = 0.3 m3; height = 1.7 m; diameter = 0.74 m; wall thickness = 1 mm |

Stainless steel container to provide TMP |

| Biolubricant container | Volume = 2 m3; height = 2.9 m; diameter = 1.15 m; wall thickness = 1.2 mm |

Stainless steel container to store WCO-TMP and to include TBHQ. A cooling and temperature control system is included |

| TBHQ container |

Volume = 150 L; height = 0.975 m; diameter = 0.48 m |

HDPE container to store and supply TBHQ when necessary |

| Condition | 1st reaction | 2nd reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Initial temperature, ˚C | 15 | 60 |

| Final (reaction) temperature, ˚C | 60 | 120 |

| Heating time, min | 35 | 40 |

| Saturated steam, kg | 136.1 | 112.5 |

| Flow, kg·min˗1 | 3.9 | 2.82 |

3.5.3. Reactor design

3.5.4. Economic study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Sustainable Development Goals. 2019.

- United Nations United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico Balances Energéticos.

- Di Serio, M.; Ledda, M.; Cozzolino, M.; Minutillo, G.; Tesser, R.; Santacesaria, E. Transesterification of Soybean Oil to Biodiesel by Using Heterogeneous Basic Catalysts. Ind Eng Chem Res 2006, 45, 3009–3014. [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.J.; Marques, J.P.C.; Rios, I.C.; Cecilia, J.A.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Luna, F.M.T.; Cavalcante, C.L. Production of Biolubricants from Soybean Oil: Studies for an Integrated Process with the Current Biodiesel Industry. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2021, 165, 456–466. [CrossRef]

- Mazanov, S. V.; Gabitova, A.R.; Usmanov, R.A.; Gumerov, F.M.; Labidi, S.; Amar, M. Ben; Passarello, J.P.; Kanaev, A.; Volle, F.; Neindre, B. Le Continuous Production of Biodiesel from Rapeseed Oil by Ultrasonic Assist Transesterification in Supercritical Ethanol. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2016. [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; Nogales-Delgado, S.; Sánchez, N.; González, J.F. Biolubricants from Rapeseed and Castor Oil Transesterification by Using Titanium Isopropoxide as a Catalyst: Production and Characterization. Catalysts 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.B.; Biberdžić, M.O.; Banković-Ilić, I.B.; Djalović, I.G.; Tasić, M.B.; Nježić, Z.B.; Stamenković, O.S. Biodiesel Production from Corn Oil: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 91, 531–548. [CrossRef]

- Nongbe, M.C.; Ekou, T.; Ekou, L.; Yao, K.B.; Le Grognec, E.; Felpin, F.X. Biodiesel Production from Palm Oil Using Sulfonated Graphene Catalyst. Renew Energy 2017. [CrossRef]

- Salimon, J.; Salih, N. Epoxidized Malaysian Elaeis Guineensis Palm Kernel Oil Trimethylolpropane Polyol Ester as Green Renewable Biolubricants. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106883. [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, E.; Canakci, M.; Ozsezen, A.N.; Turkcan, A.; Sanli, H. Using Waste Animal Fat Based Biodiesels-Bioethanol-Diesel Fuel Blends in a Di Diesel Engine. Fuel 2015. [CrossRef]

- Banković-Ilić, I.B.; Stojković, I.J.; Stamenković, O.S.; Veljkovic, V.B.; Hung, Y.T. Waste Animal Fats as Feedstocks for Biodiesel Production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 32, 238–254. [CrossRef]

- Behçet, R.; Oktay, H.; Çakmak, A.; Aydin, H. Comparison of Exhaust Emissions of Biodiesel-Diesel Fuel Blends Produced from Animal Fats. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015.

- Ahmad, U.; Naqvi, S.R.; Ali, I.; Naqvi, M.; Asif, S.; Bokhari, A.; Juchelková, D.; Klemeš, J.J. A Review on Properties, Challenges and Commercial Aspects of Eco-Friendly Biolubricants Productions. Chemosphere 2022, 309. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Encinar, J.M.; González, J.F. A Review on Biolubricants Based on Vegetable Oils through Transesterification and the Role of Catalysts: Current Status and Future Trends. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1299. [CrossRef]

- Barbera, E.; Hirayama, K.; Maglinao, R.L.; Davis, R.W.; Kumar, S. Recent Developments in Synthesizing Biolubricants — a Review. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 2867–2887.

- Chen, J.; Bian, X.; Rapp, G.; Lang, J.; Montoya, A.; Trethowan, R.; Bouyssiere, B.; Portha, J.F.; Jaubert, J.N.; Pratt, P.; et al. From Ethyl Biodiesel to Biolubricants: Options for an Indian Mustard Integrated Biorefinery toward a Green and Circular Economy. Ind Crops Prod 2019, 137, 597–614. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Guiberteau Cabanillas, A.; Moro, J.P.; Encinar Martín, J.M. Use of Propyl Gallate in Cardoon Biodiesel to Keep Its Main Properties during Oxidation. Clean Technologies 2023, 5, 569–583. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Guiberteau, A.; Encinar, J.M. Effect of Tert-Butylhydroquinone on Biodiesel Properties during Extreme Oxidation Conditions. Fuel 2022, 310, 122339. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Cabanillas, A.G.; Romero, Á.G.; Encinar Martín, J.M. Monitoring Tert-Butylhydroquinone Content and Its Effect on a Biolubricant during Oxidation. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Agarwal, P.; Porwal, J.; Porwal, S.K. Evaluation of Multifunctional Green Copolymer Additives–Doped Waste Cooking Oil–Extracted Natural Antioxidant in Biolubricant Formulation. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 761–770. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Agarwal, P.; Porwal, S.K. Natural Antioxidant Extracted Waste Cooking Oil as Sustainable Biolubricant Formulation in Tribological and Rheological Applications. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3127–3137. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.R.; Bhanderi, K.K.; Patel, J. V.; Karve, M. Chemical Modification of Waste Cooking Oil for the Biolubricant Production through Transesterification Process. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2023, 100. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Ma, X.; Tang, S.; Yan, R.; Wang, Y.; Riley, W.W.; Reaney, M.J.T. Synthesis and Oxidative Stability of Trimethylolpropane Fatty Acid Triester as a Biolubricant Base Oil from Waste Cooking Oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 66, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Teng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Reaney, M.J.T. K2CO3-Loaded Hydrotalcite: A Promising Heterogeneous Solid Base Catalyst for Biolubricant Base Oil Production from Waste Cooking Oils. Appl Catal B 2017, 209, 118–127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ji, H.; Song, Y.; Ma, S.; Xiong, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X. Green Preparation of Branched Biolubricant by Chemically Modifying Waste Cooking Oil with Lipase and Ionic Liquid. J Clean Prod 2020, 274. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.R.; Miranda, L.P.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Tardioli, P.W. Immobilization of Eversa® Transform via CLEA Technology Converts It in a Suitable Biocatalyst for Biolubricant Production Using Waste Cooking Oil. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, H.; Adhikari, S.; Roy, P.; Shelley, M.; Hassani, E.; Oh, T.S. Synthesis of Novel Biolubricants from Waste Cooking Oil and Cyclic Oxygenates through an Integrated Catalytic Process. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2021, 9, 13424–13437. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Chakraborty, R.; Mitra, D.; Biswas, D. Optimization of the Production Parameters of Octyl Ester Biolubricant Using Taguchi’s Design Method and Physico-Chemical Characterization of the Product. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 52, 783–789. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Mitra, D.; Biswas, D. Biolubricant Synthesis from Waste Cooking Oil via Enzymatic Hydrolysis Followed by Chemical Esterification. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2013, 88, 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.Z.K.; Attia, N.K.; Fouad, M.K.; ElSheltawy, S.T. Experimental Investigation and Process Simulation of Biolubricant Production from Waste Cooking Oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 144. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hamid, E.M.; Amer, A.M.; Mahmoud, A.K.; Mokbl, E.M.; Hassan, M.A.; Abdel-Monaim, M.O.; Amin, R.H.; Tharwat, K.M. Box-Behnken Design (BBD) for Optimization and Simulation of Biolubricant Production from Biomass Using Aspen plus with Techno-Economic Analysis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 21769. [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; Nogales-Delgado, S.; Pinilla, A. Biolubricant Production through Double Transesterification: Reactor Design for the Implementation of a Biorefinery Based on Rapeseed. Processes 2021, 9, 1224. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Encinar, J.M.; González, J.F. Safflower Biodiesel: Improvement of Its Oxidative Stability by Using BHA and TBHQ. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- 14214, U.-E. Liquid Petroleum Products – Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Use in Biodiesel Engines and Heating Applications – Requirements and Test Methods. 2013.

- UNE-EN ISO 3104/AC:1999 Petroleum Products. Transparent and Opaque Liquids. Determination of Kinematic Viscosity and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity (ISO 3104:1994). 1999.

- UNE-EN-ISO 3675 Crude Petroleum and Liquid Petroleum Products. Laboratory Determination of Density. Hydrometer Method 1999.

- UNE-EN 14112 Fat and Oil Derivatives - Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) - Determination of Oxidation Stability (Accelerated Oxidation Test) 2017.

- UNE-EN 14104:2003 Oil and Fat Derivatives. Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME). Determination of Acid Value. 2003.

- UNE-EN 51023:1990 Petroleum Products. Determination of Flash and Fire Points. Cleveland Open Cup Method. 1990.

- UNE-EN 116:2015 Diesel and Domestic Heating Fuels – Determination of Cold Filter Plugging Point- Stepwise Cooling Bath Method. 2015.

- Freedman, B.; Butterfield, R.O.; Pryde, E.H. Transesterification Kinetis of Soybean Oil; 1981; Vol. 58;

- Khan, E.; Ozaltin, K.; Spagnuolo, D.; Bernal-ballen, A.; Piskunov, M. V; Martino, A. Di Biodiesel from Rapeseed and Sunflower Oil : Effect of the Transesterification Conditions and Oxidation Stability. 2023.

- Bencheikh, K.; Atabani, A.E.; Shobana, S.; Mohammed, M.N.; Uğuz, G.; Arpa, O.; Kumar, G.; Ayanoğlu, A.; Bokhari, A. Fuels Properties, Characterizations and Engine and Emission Performance Analyses of Ternary Waste Cooking Oil Biodiesel–Diesel–Propanol Blends. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2019, 35, 321–334. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Meneses, L.; Hari, A.; Inayat, A.; Yousef, L.A.; Alarab, S.; Abdallah, M.; Shanableh, A.; Ghenai, C.; Shanmugam, S.; Kikas, T. Recent Advances on Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil (WCO): A Review of Reactors, Catalysts, and Optimization Techniques Impacting the Production. Fuel 2023, 348. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Guiberteau Cabanillas, A.; Catela Rodríguez, A. Combined Effect of Propyl Gallate and Tert-Butyl Hydroquinone on Biodiesel and Biolubricant Based on Waste Cooking Oil. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Pullen, J.; Saeed, K. An Overview of Biodiesel Oxidation Stability. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012.

- Rizwanul Fattah, I.M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Hazrat, M.A.; Masum, B.M.; Imtenan, S.; Ashraful, A.M. Effect of Antioxidants on Oxidation Stability of Biodiesel Derived from Vegetable and Animal Based Feedstocks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 30, 356–370.

- Encinar, J.M.; Nogales-Delgado, S.; Álvez-Medina, C.M. High Oleic Safflower Biolubricant through Double Transesterification with Methanol and Pentaerythritol: Production, Characterization, and Antioxidant Addition. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15, 103796. [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Encinar Martín, J.M.; Sánchez Ocaña, M. Use of Mild Reaction Conditions to Improve Quality Parameters and Sustainability during Biolubricant Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 161, 106456. [CrossRef]

- Varatharajan, K.; Pushparani, D.S. Screening of Antioxidant Additives for Biodiesel Fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 2017–2028.

- Nogales-Delgado, S.; Encinar, J.M.; Guiberteau, A.; Márquez, S. The Effect of Antioxidants on Corn and Sunflower Biodiesel Properties under Extreme Oxidation Conditions. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2019. [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.G.; Medeiros, M.L.; Cordeiro, A.M.M.T.; Queiroz, N.; Soledade, L.E.B.; Souza, A.L. Efficient Antioxidant Formulations for Use in Biodiesel. Energy and Fuels 2014, 28, 1074–1080. [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Imahara, H.; Saka, S. Kinetics on the Oxidation of Biodiesel Stabilized with Antioxidant. Fuel 2009, 88, 282–286. [CrossRef]

- Bizkaia garbiker Recogida de Residuos.

- BOE XX Convenio Colectivo General de La Industria Química.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| FAME/TMP ratio | 3 |

| Catalyst concentration, % | 0.3-1.0 |

| Reaction time, min | 120 |

| Reaction temperature, ˚C | 80-140 |

| Stirring rate, rpm | 350 |

| Working pressure, mmHg | 210-760 |

| Parameter | WCO-FAME | WCO-TMP | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAME content | Yes | No | [35] |

| Viscosity | Yes | Yes | [36] |

| Density | Yes | Yes | [37] |

| Oxidation stability | Yes | Yes | [38] |

| Acid value | Yes | Yes | [39] |

| Flash and combustion points | Yes | Yes | [40] |

| Cold filter plugging point | Yes | No | [41] |

| T, ˚C | T, K | k’ |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 353 | 0.0141 |

| 100 | 373 | 0.0176 |

| 120 | 393 | 0.0245 |

| 140 | 413 | 0.0339 |

| Catalyst concentration, % w/w | k’2 |

|---|---|

| 0.3 | 0.0141 |

| 0.5 | 0.0237 |

| 0.7 | 0.0468 |

| 0.9 | 0.1096 |

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Working hours, h·y˗1 | 2112 |

| Collected WCO, kg·y˗1 | 423823 |

| Processing capacity, kg·h˗1 | 206.03 |

| Processing capacity, kg·d˗1 | 1648 |

| Methanol required*, kg·d˗1 | 357.44 |

| Reagent | Molecular weight, g·mol˗1 | Density, kg·m˗3 | Mass flow, kg·h˗1 | Inlet mass, kg | Inlet volume, m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCO | 900 | 920 | 209.2 | 1673.80 | 1.82 |

| CH3OH | 32.04 | 792 | 44.68 | 357.44 | 0.45 |

| Sodium methoxide | 54.03 | 970 | 6.28 | 50.2 | 0.05 |

| Reagent | Molecular weight, g·mol˗1 | Density, kg·m˗3 | Mass flow, kg·h˗1 | Inlet mass, kg | Inlet volume, m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAMEs | 284.52 | 880 | 198.37 | 1586.96 | 1.8 |

| TMP | 134.17 | 1080 | 22.33 | 178.66 | 0.17 |

| Sodium methoxide | 54.03 | 970 | 5.95 | 47.62 | 0.05 |

| Parameter | Size |

|---|---|

| Reactor volume, m3 | 3 |

| Reactor surface, m2 | 29.49 |

| Inner diameter, m | 1.563 |

| Height, m | 1.562 |

| Wall thickness, mm | 6 |

| Weight, kg | 168.53 |

| Da | H | J | E | W | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.521 | 1.563 | 0.130 | 0.521 | 0.104 | 0.130 |

| Transesterification process |

Reagent | Price, €·T˗1 |

Amount, T·y˗1 |

Annual cost, €·y˗1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | WCO | 82 | 435.12 | 35679.84 |

| CH3OH | 265 | 92.93 | 24626.45 | |

| Sodium methoxide |

1800 | 13.05 | 23490 | |

| Total | -- | 541.1 | 83796.29 | |

| 2nd | TMP | 150 | 46.45 | 6967.5 |

| Sodium methoxide |

1800 | 12.38 | 22284 | |

| Total | -- | 58.83 | 29251.5 |

| Job post | Number of workers | Salary | Total salary + social charges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant manager | 1 | 44658.05 | 60288.37 |

| Chemist | 1 | 28985.65 | 39130.63 |

| Qualified worker | 2 | 21739.23 | 51087.19 |

| Total | 4 | 95382.93 | 150506.19 |

| Step | Power, kW | Daily working time | Yearly energy consumption, kWh | Annual cost, €·y˗1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | 25.54 | 1.3 | 8632.52 | 1553.85 |

| Stirring | 22.25 | 2.51 | 14520.35 | 2613.66 |

| Vacuum | 2.2 | 0.67 | 383.24 | 68.98 |

| Purification | 44 | 0.7 | 8008.00 | 1441.44 |

| Total | 91.87 | -- | 31544.11 | 5677.94 |

| Equipment | Cost (VAT included), € |

|---|---|

| WCO container | 2660 |

| Methanol container | 235.95 |

| Recovered methanol container | 179.95 |

| Sodium methoxide container | 179.95 |

| Glycerol container | 235.95 |

| TMP container | 1180 |

| Biolubricant container | 4500 |

| TBHQ container | 42.35 |

| Steam generator | 3194 |

| Vacuum pump | 2360.60 |

| Purifier | 4100 |

| Reactor | 33741 |

| Stirrer | 35639 |

| Annual production costs | Annual income | ||||

| Production |

Cost, € |

Product |

Production, L·y˗1 |

Selling price, €·L ˗1 |

Annual income, € |

| Raw materials | 150808.43 | Biolubricant | 446424 | 2.89 | 1290165.36 |

| Energy | 5677.94 |

Production, T·y˗1 |

Selling price, €·T ˗1 |

Annual income, € | |

| Water | 588.02 | Glycerol | 128.56 | 250 | 32140 |

| Annual profit | |||||

| Total annual costs (production), € | 157074.39 | ||||

| Total annual incomes, € | 1322305.36 | ||||

| Annual gross profit, € | 1165230.97 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).