Introduction

The current standard for modern prosthetic abdominal hernia repair involves the use of flat meshes to cover the herniated area. [

1] These flat meshes, however, are static and do not interact with the highly motile environment of the abdominal wall. When secured with sutures or tacks, they hinder the natural dynamics of the abdominal musculature, resulting in an unphysiological effect. [

2,

3] The foreign body response triggered by hernia meshes activates an immune reaction, leading to the formation of a granulomatous fibrotic scar that infiltrates the prosthesis. [

4] This fibrotic response is often presented as “reinforcement” of the weakened muscle area, but it fails to address the underlying degenerative processes responsible for hernia formation. [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Considering the degenerative etiology of hernia disease, an optimal treatment should not only prevent further tissue deterioration but also promote the regeneration of the muscular barrier. [

14] Failure to meet these physiological and pathogenetic needs likely contributes to the recurring adverse events seen after conventional hernia repair. [

15,

16,

17,

18] Despite ongoing issues, no definitive solution has been found to date.

Recent advances in the understanding of functional anatomy and hernia pathogenesis have led to the development of a novel approach for treating inguinal and other abdominal hernias. This approach introduces the Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System, a device made of medical-grade polypropylene based Thermo-Polymer- Elastomer (TPE), designed to address the shortcomings of flat meshes in abdominal hernioplasty, particularly but not exclusively in inguinal hernias. The proprietary design of the S&S device transforms it into a 3D scaffold upon deployment, achieving fixation-free, permanent obliteration of the hernia defect. Thanks to its dynamic compliance, the device moves harmoniously with the abdominal wall musculature, converting the body’s biological response into tissue regeneration. This distinctive feature is facilitated by various tissue growth factors that actively support the integration of newly formed connective tissue, muscles, blood vessels, and nerves into the 3D structure of the scaffold, ultimately achieving true regeneration of the abdominal wall’s composite tissues. [22–30].

This report outlines the outcomes of histological and immunohistochemical analyses performed on tissue samples taken at various time points following the implantation of 20 S&S devices in 10 experimental pigs. The data presented here suggest that transforming the conventional static flat hernia implant into a dynamic 3D scaffold is critical for inducing regenerative responses driven by a spectrum of tissue growth factors. Specifically, rather than generating granulomatous, low-quality scar tissue typical of flat meshes, the dynamic architecture of the S&S scaffold promotes the ingrowth of highly specialized tissue elements, such as muscles, vessels, and nerves.

Material and Methods

The experimental study was performed in compliance with the Animal Care Protocol for Experimental Surgery, in line with the guidelines established by the Italian Ministry of Health. Official approval for the study was granted under Decree No. 379/2021-PR, issued on June 1st, 2021.

Between February 2022 and November 2024, a total of ten female pigs were selected for the trial, each having a bilaterally created muscular defect in the lower abdominal wall. During laparoscopic surgery, two Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia Devices were implanted per pig. The S&S device has been developed to provide a non-invasive, atraumatic repair of various abdominal hernias, including inguinal, incisional, femoral, Spigelian, and obturator hernias.

The pigs, ranging in age from 4 to 6 months, weighed between 40 and 60 kg. All surgical procedures were performed laparoscopically under general anesthesia. The anesthesia protocol included premedication with zolazepam and tiletamine (6.3 mg/kg) along with xylazine (2.3 mg/kg), followed by induction with propofol (0.5 mg/kg), and maintenance using isoflurane in combination with pancuronium (0.07 mg/kg). Post-surgery, antibiotic prophylaxis was administered, with each pig receiving oxytetracycline (20 mg/kg/day) for three days.

Structure of the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System

The S&S Hernia System employed in the trial is manufactured from medical-grade polypropylene-based Thermo-Polymer Elastomer (TPE), with its technical properties detailed in

Table 1.

This device consists of two main elements: a rayed structure assembled around a central mast and a 3D oval shield measuring 10x8 cm, with a central ring. The mast has a button-like structure at the distal end and two conical stops positioned near it. Initially, the device is configured as a cylindrical structure, with the oval shield attached by threading its central ring onto the mast (

Figure 1 A & B). This design enables easy delivery via a 12 mm trocar into the abdominal cavity. Once placed at the hernia site, the oval shield is pushed forward using a metallic tube, which advances the device into the pre-established muscular defect. As the shield moves past one or both conical stops on the mast, the cylindrical structure expands within the defect, forming a 3D scaffold that permanently seals the hernia opening. This setup locks the shield in place, preventing backward displacement and ensuring the 3D scaffold remains anchored in the defect. The shield also covers and overlaps the muscular opening, coming into direct contact with the abdominal viscera (

Figure 1 C). The final 3D scaffold used in this study measures approximately 4.5 cm in diameter.

Follow-up Protocol

Of the 10 pigs involved in the trial, two were sacrificed between 4 and 6 weeks post-implantation (short-term), another three between 3 and 4 months (mid-term) and five between 5 and 8 months (long-term). Each pig underwent ultrasound examinations (

Figure 1 D) and laparoscopic evaluations at predefined postoperative intervals to confirm proper positioning of the 3D scaffold and to check for any adhesions between the shield and abdominal organs.

At the time of sacrifice, the implanted S&S devices were removed in one piece through a lower midline incision. The explanted devices were meticulously cleaned of host tissue, bisected, and examined for macroscopic evaluation of the tissue growth within the 3D scaffold (

Figure 2). These samples were then sent for detailed histological analysis.

Histological assessment

Tissue samples excised from the core of the 3D scaffold were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for a minimum of 12 hours before being embedded in paraffin. Thin sections (4 μm) were prepared and stored at room temperature for later use. Routine histological analysis aimed to detect basic histomorphological characteristics of muscle, vascular and nervous structures, was carried out with Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) and Azan Mallory stain (Bioptica Via S. Faustino, 58, 20134 Milano - Italy).

Immunohistochemistry

After dewaxing the sections, antigen retrieval was carried out using a Tris-EDTA solution (pH 9.0), which was heated to 96°C for 20 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was suppressed by incubating the slides in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution in methanol for 30 minutes. To minimize background staining, a 15-minute treatment with Background Sniper was performed. The tissue sections were then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with primary antibodies, including NSE, CD31, SMA, VEGF, NGF, and NGFRp75. A comprehensive list of the antibodies used for this study is provided in

Table 2.

Following antibody incubation, the sections were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for five minutes each. The slides were then exposed to biotinylated immunoglobulin (LSAB, Dako, USA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. This was followed by two additional washes in PBS, after which the slides were treated with streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 hour at room temperature. After being washed three times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), the sections were developed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Dako Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as the chromogen. The slides were then rinsed under running water and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, after which they were briefly dipped in 0.035% TBS solution for 1 minute. Positive immunoreactivity was indicated by the appearance of a brown precipitate from the DAB reaction. Negative controls were prepared by replacing the primary antibodies with either normal goat serum or PBS. As positive controls, tissue samples from vascular, nervous, or muscle tissues were used. All stained slides were evaluated under 100× magnification using a Leica DMR microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 digital camera, and images were captured using NIS Basic Research software.Monoclonal primary antibody NSE (LSBio) was applied at 1:100 dilution for 60 minutes to highlight evidence of newly developed nervous structures in the 3D scaffold of the S&S device.

Results

Biopsy samples and the corresponding histological sections were independently reviewed by two pathologists without prior knowledge of the sample collection times. The series of images presented here are organized by the post-surgery stages of the biopsies, beginning with the identification of specific tissue growth factors, followed by microphotographs that illustrate the developmental stages of the associated tissue structures.

Angiogenic Growth Factors and Vascular Structures in the 3D Scaffold of the S&S Hernia System

Regarding vascular tissue development, the specimens obtained 3-5 weeks after implantation (Short-Term, ST) H&E staining revealed numerous clusters of newly formed, immature vascular structures. Inflammatory infiltration against the polypropylene material of the scaffold was minimal, with only a few lymphocytes and histiocytes, while fibroblast proliferation and connective tissue formation were prominent in this early phase (

Figure 3).

The tissue specimens also exhibited clear evidence of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis (

Figure 4) and a marked CD31-positive response, which played a crucial role in vessel formation (

Figure 5). Early formation of smooth muscle cells, as indicated by the presence of smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive elements, was also observed, though limited in extent (

Figure 6)

In the midterm samples (3-4 months post-implantation), plenty of vascular structures in advanced stage of development were clearly detected close to 3D scaffold. No inflammatory reaction against the TPE structure pf the S&S device could be evidenced. (

Figure 7)

The tissue specimens also evidenced a decreased level of VEGF stained elements (

Figure 8), but there was a notable increase in vessel density as evidenced by CD31 staining (

Figure 9). During this period, smooth muscle cell development, induced by SMA, became more pronounced in veins and arteries (

Figure 10)

By the long-term stage (5-8 months post-implantation), H&E staining demonstrated the presence of mature, well-defined arteries and veins within the newly formed tissue around the S&S Hernia System. No inflammatory response surrounding the TPE structure of the S&S device could be detected (

Figure 11).

Tissue samples also proved that the VEGF expression had further diminished (

Figure 12), but CD31 continued to highlight endothelial cell growth (

Figure 13). SMA staining confirmed the maturation of the smooth muscle layer within the arterial walls, indicating that vessel formation was complete (

Figure 14).

Myogenic Growth Factors and Muscle Structures in the 3D Scaffold of the S&S Hernia System

Regarding muscle development, biopsy samples obtained in the short-term period after implantation of the S&S 3D scaffold showed a high concentration of nerve growth factor (NGF)-positive cells within the thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) material of the 3D scaffold (

Figure 15).

Table 16 The nascent myocytes exhibited prominent nucleoli, vesicular nuclei, and moderate basophilia, indicative of early myocytic differentiation. By the midterm phase, the number of NGF-positive cells had increased in the TPE fabric of the scaffold (

Figure 17), corresponding with a more extensive and organized development of muscle fibers and larger bundles of muscle cells interspersed throughout the connective tissue adjacent to the scaffold. The muscle fibers showed small, spindle-shaped nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, characteristic of progressing myocyte differentiation (

Figure 18).

Figure 16.

Biopsy specimen excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Viable connective tissue (stained in blue) surrounds developing muscle bundles (stained in red) in early stages near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). AM 200X.

Figure 16.

Biopsy specimen excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Viable connective tissue (stained in blue) surrounds developing muscle bundles (stained in red) in early stages near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). AM 200X.

Figure 17.

Tissue specimen removed 4 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Large numbers of NGF-positive elements (brown staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 50X.

Figure 17.

Tissue specimen removed 4 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Large numbers of NGF-positive elements (brown staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 50X.

Figure 18.

Tissue specimen removed 3 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Multiple developing muscle bundles (red staining) surrounded by viable connective tissue (colored in blue) are seen close to the 3D scaffold (X). AM 100X.

Figure 18.

Tissue specimen removed 3 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Multiple developing muscle bundles (red staining) surrounded by viable connective tissue (colored in blue) are seen close to the 3D scaffold (X). AM 100X.

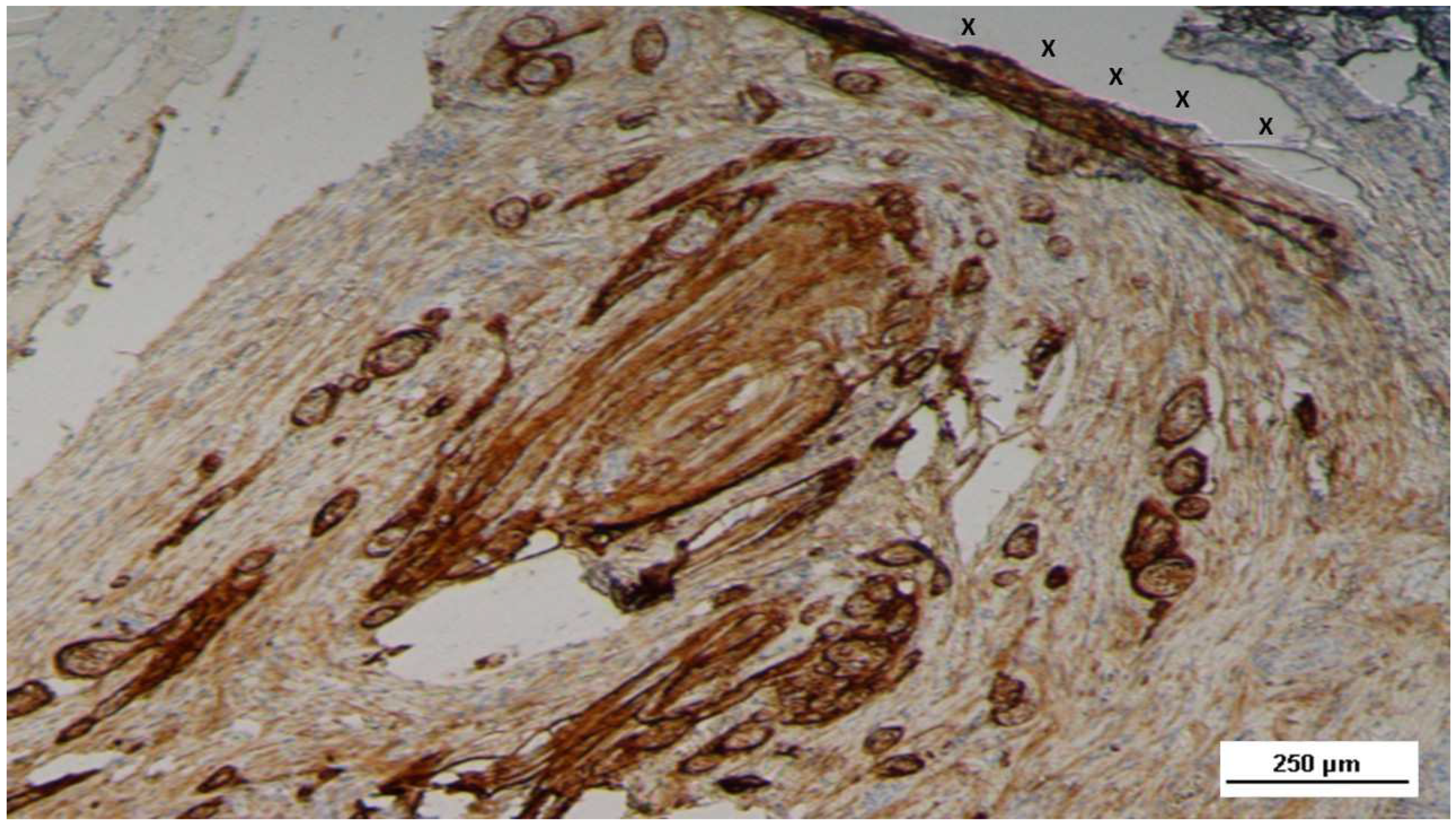

In the long-term phase (6-8 months post-implantation), numerous NGF-positive cells were observed within the scaffold, indicating continued stimulation of muscle regeneration (

Figure 19).

Large regions of mature muscle bundles were now present, integrated with well-perfused connective tissue. The bundles appeared to be fully developed muscle fibers, aligned according to functional lines of tension. At higher magnification, striated muscle fibers were clearly visible, displaying the typical spindle-shaped myocytes with small, hyperchromatic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, closely resembling normal human muscle tissue (

Figure 20).

Neurogenic Growth Factors and Nerve Structures in the 3D Scaffold of the S&S Hernia System

In the early post-implantation period (Short-term, ST), the neurogenic growth factor NGFRp75, which is critical for nerve formation, was observed in limited quantities throughout the S&S Hernia System structure (

Figure 21).

During this phase, several immature nerve structures, including developing myelin sheaths, were identified in the scaffold, immersed in well-vascularized connective tissue (

Figure 22).

At the midterm (MT) stage, biopsy samples exhibited a notable increase in the number of NGFRp75-positive elements (

Figure 23). These elements were associated with the presence of numerous large, developing nerve structures, arranged within the scaffold in a well-organized connective tissue matrix. These nerve structures were surrounded by clearly formed myelin sheaths positioned adjacent to the S&S Hernia System’s structure (

Figure 24).

In the long-term (LT) stage, compared to earlier phases, there was a marked increase in NGFRp75-positive spindle-shaped cells, located in the cytoplasm and along the membrane of cells near the 3D scaffold (

Figure 25).

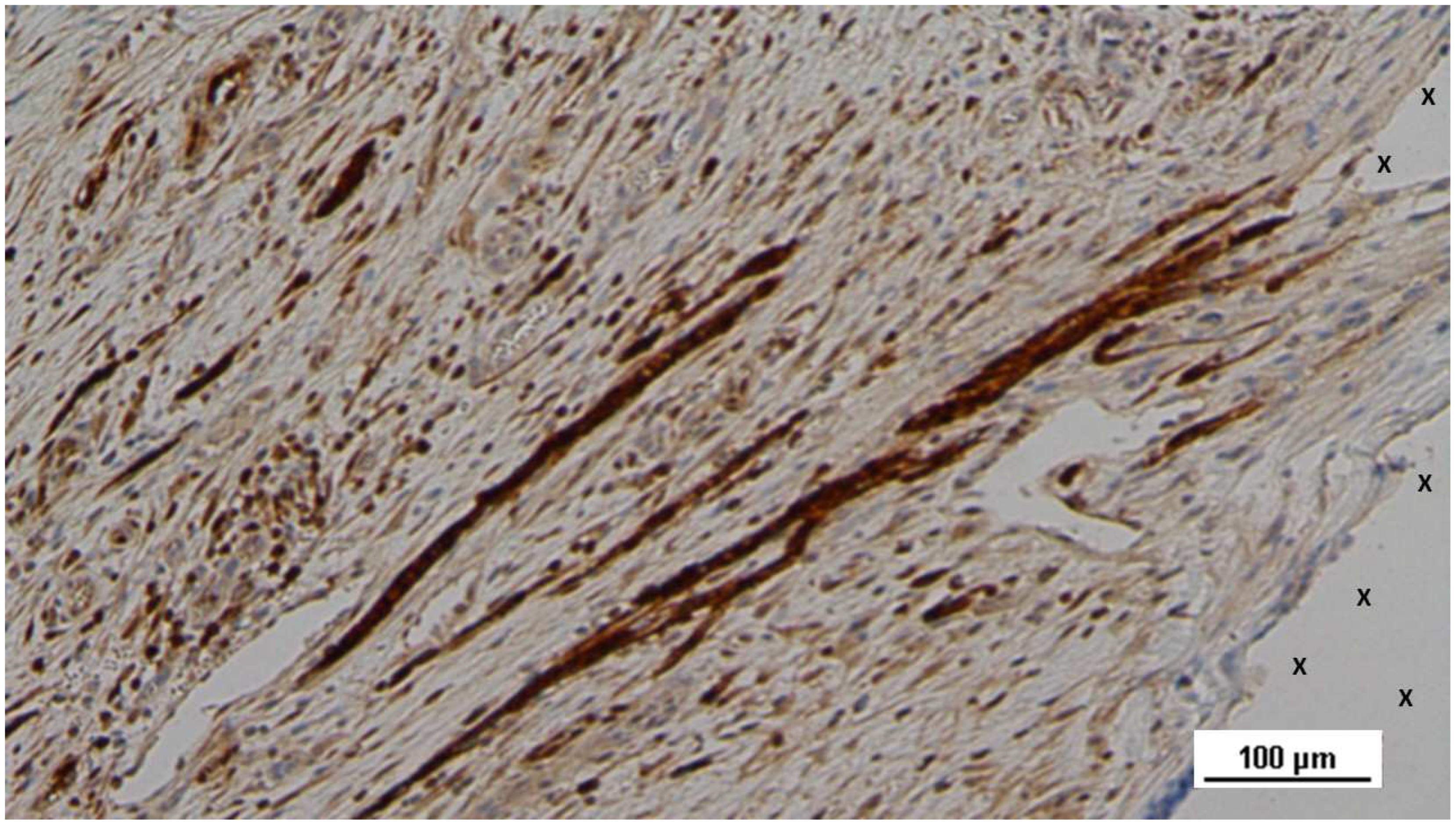

Numerous mature nerve structures were detected adjacent to the scaffold, signifying advanced nerve growth. These nerves, which developed within the S&S device, displayed substantial increases in both myelin and axon formation, resembling typical human nerve structures in terms of their key components (

Figure 26).

A summary of the histological and immunohistochemical findings is provided in

Table 3.

Discussion

The use of flat polypropylene meshes for reinforcing the herniated groin is widely considered the gold standard in treating abdominal hernias [31–33]. However, these traditional meshes are inherently passive and do not engage with the dynamic loads imposed by the abdominal wall, one of the most mobile regions of the body. To prevent migration, these meshes are typically secured to the surrounding muscle tissue with sutures or tacks. Unfortunately, this approach creates a physiological disconnect, as fastening meshes restrict normal muscle movement, increasing postoperative pain and the risk of adverse events [34–36].

A further concern with conventional hernia mesh repairs is that they may not address the underlying pathogenesis of the condition, particularly in inguinal hernias. The ideal treatment should not only prevent hernia recurrence but also target the degenerative processes driving tissue weakness and failure. However, conventional meshes always result in the formation of foreign body granulomas, which are regressive rather than regenerative in nature. Additionally, uncontrolled fibrotic incorporation of the mesh may entrap nearby nerves, which can lead to chronic pain—a debilitating complication as widely reported following inguinal herniorrhaphy [15–18,36].

To address these issues, a new approach has been introduced with the Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System. Unlike conventional meshes, the S&S system, made from a medical-grade polypropylene-based Thermo-Polymer Elastomer (TPE), is designed with a combination of a shield assembled to a 3D scaffold. Once deployed, it obliterates the hernia defect in a fixation-free fashion. The 3D scaffold is compressible in all planes and features recoil memory, allowing it to expand and contract with the movement of the abdominal wall. Unlike conventional meshes, the biological response of the S&S Hernia System is markedly different. In prior studies [S&S ref.25], this device has been shown to support the formation of new, highly specialized tissues similar to those found in the abdominal wall. Regenerative scaffolds like this are widely studied in scientific research and are designed to promote the development of new cellular structures when implanted [37–39].

As shown in the current study, vascular growth within the 3D scaffold of the S&S device is mediated by specific growth factors that act in a time-dependent manner. In the early postoperative phase (short-term), VEGF initiates the process of vascular formation, as indicated by the appearance of scattered CD31- and SMA-positive vascular elements. As the process continues over the next several months, the vascular network becomes more developed, with a reduction in VEGF levels and an increase in CD31 activity, signaling the formation of structured vessels. Concurrently, SMA positivity indicates the maturation of arterial and venous smooth muscle, contributing to the muscular layers of these vessels. By the long-term stage, the presence of VEGF has diminished, but CD31 remains active, and SMA continues to stabilize the muscle components of the vasculature. Eventually, a fully developed vascular system emerges, capable of perfusing the new tissues growing within the 3D scaffold, particularly muscles and nerves.

The formation of skeletal muscle follows a parallel course, driven by the differentiation of myogenic precursor cells. Cytokines and specific growth factors in the microenvironment of the 3D S&S scaffold stimulate the formation of myofibrils [40]. During the early phases, myocytes begin to produce neurotrophic factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF), as well as its receptors, TrkA, TrkB, and p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). NGF plays a crucial role in nerve cell survival and also regulates several important metabolic processes in other tissues [41–43]. NGF signaling is controlled by two types of receptors: the tropomyosin-related kinase (Trk) receptors and the p75 neurotrophin receptor (NGFRp75) [44]. Research has demonstrated that NGFRp75 promotes both the survival of myotubes and myogenic differentiation in vitro, and is also critical for muscle repair in vivo [40,41].

NGFRp75, also known as p75(NTR) due to its molecular mass, binds not only NGF but also other neurotrophins, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NTF3), and neurotrophin-4 (NTF4), with low affinity [43]. During the regeneration and growth of peripheral nerves, Schwann cells express increased levels of p75(NTR), which facilitates nerve myelination. Studies by Cosgaya et al. have shown that the absence of functional p75(NTR) impairs myelin formation, whereas its presence enhances it [44]. Furthermore, p75(NTR) appears to mediate myelin formation by interacting with endogenous BDNF, while TrkC receptors, which regulate neuronal survival, have the opposite effect, inhibiting myelination by responding to neurotrophin-3. The balance between these receptors governs myelination during glial proliferation and elongation. This model, established by Cosgaya et al., highlights the interplay between neurotrophins and their receptors in nerve development [44]. In the context of the S&S Hernia System, the presence of NGF and NGFRp75 in biopsy samples taken at different time points aligns with the progressive formation of muscle and nerve tissues within the 3D scaffold of the S&S device. These findings provide a plausible explanation for the development of newly formed muscle and nerve structures within the 3D scaffold of the device over time.

While the outcomes of this animal investigation looks encouraging, one limitations must be recognized. It concerns the size of the sample: actually the study was carried out on a relatively small cohort of 10 pigs (20 S&S devices implanted in total). Even though, as verified in the literature, such a figure seems sufficient to demonstrate preliminary safety and effectiveness, a larger sample size could achieve stronger statistical power thus improving the generalizability of the outcomes. [22] However, dealing with the financials of the investigation — that include purchasing of the pigs with related stabulation of all 10 animals up to 8 months and personnel costs— has entailed a significant economic burden.

In conclusion, the S&S Hernia System’s regenerative characteristics appear to be well-suited to the physiological demands of the abdominal wall. Unlike traditional flat meshes, which remain static and lead to fibrotic granulomas, the S&S system is dynamic, moving in synchrony with the surrounding musculature. This dynamic movement facilitates the regeneration of tissue structures damaged by the degenerative processes of hernia disease. The promising results obtained in this animal study lay the groundwork for future clinical trials in humans. Such studies will be critical in determining whether the tissue growth factors and biological responses observed in this experiment can be replicated in human patients. If confirmed, the S&S Hernia System could represent a significant advancement in hernia repair, potentially simplifying surgical procedures and enhancing patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

AG Conceptualization. PR Investigation. RG Validation. GDB Software, GC Resources. LC Methodology. RG2nd Project Administration. RW Review & Editing. NC Data Curation. AA Formal Analysis. VR Supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the reported results are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The corresponding author is the developer and patent owner of the device described in the report. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lichtenstein, I.L.; Shulman, A.G.; Amid, P.K.; Montllor, M.M. The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg. 1989, 157, 188–193, Amid PK. (2004) Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: Its inception, evolution, and prin-ciples Hernia 8: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K.; Shulman, A.G.; Lichtenstein, I.L.; Hakakha, M. Biomaterials for abdominal wall hernia surgery and principles of their applications. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 1994, 379, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Goetze, T.; Cicero, L.; Gulotta, E.; Calò, P.G.; Agrusa, A. Fixation free inguinal hernia repair with the 3D dynamic responsive prosthesis S&S Hernia System: Features, procedural steps and long-term results. International Journal of Surgery Open 2019, 21, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Klosterhalfen, B.; Klinge, U.; Schumpelick, V. Functional and morphological evaluation of different polypropylene-mesh modifications for abdominal wall repair. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Calò, P.G.; Rodolico, V.; Puleio, R.; Agrusa, A.; Gulotta, L.; Gordini, L.; Romano, G. The Septum Inguinalis: A Clue to Hernia Genesis? J Invest Surg. 2018, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Goetze, T.; Cicero, L.; Gulotta, E.; Calò, P.G.; Agrusa, A. Fixation free inguinal hernia repair with the 3D dynamic responsive prosthesis S&S Hernia System: Features, procedural steps and long-term results. International Journal of Surgery Open 2019, 21, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, G.; Marasa, L.; Sciacchitano, T.; Bell, S.G.; Romano, G.; Gioviale, M.C.; Monte, A.I.L.; Romano, M. Histological findings of the internal inguinal ring in patients having indirect inguinal hernia. Hernia 2009, 13, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Ober, E.; Romano, G.; Salamone, G.; Agrusa, A.; Gulotta, G.; Bussani, R. Nerve degeneration in inguinal hernia specimens. Hernia 2010, 15, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Salamone, G.; Agrusa, A.; Saladino, V.A.; Silvestri, F.; Bussani, R. Damage to the vascular structures in inguinal hernia specimens. Hernia 2011, 16, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Romano, G.; Salamone, G.; Gulotta, G.; Silvestri, F.; Bussani, R. Muscle degeneration in inguinal hernia specimens. Hernia 2011, 16, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Romano, G.; Salamone, G.; Cocorullo, G.; Mularo, S.A.; Marasa, S.; Gulotta, G. Histological findings in direct inguinal hernia. Hernia 2013, 17, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G. The Septum Inguinalis: Its Role in the Pathogenesis of Inguinal Hernia. In Inguinal Hernia: Pathophysiology and Genesis of the Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G. State of the Art and Future Perspectives in Inguinal Hernia Repair. In Inguinal Hernia: Pathophysiology and Genesis of the Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K. Causes, prevention, and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy neuropathic inguinodynia: Triple neurectomy with proximal end implantation. Hernia 2004, 8, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dwyer, P.J.; Kingsnorth, A.N.; Molloy, R.G.; Small, P.K.; Lammers, B.; Horeyseck, G. Randomized clinical trial assessing impact of a lightweight or heavyweight mesh on chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2005, 92, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, D.; Moltó, L.; Pereira, J.A.; Montes, A. Chronic pain after groin hernia repair: pain characteristics and impact on quality of life. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwaans, W.A.R.; Verhagen, T.; Wouters, L.; Loos, M.J.A.; Roumen, R.M.A.; Scheltinga, M.R.M. Groin Pain Characteristics and Recurrence Rates: Three-year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Self-gripping Progrip Mesh and Sutured Polypropylene Mesh for Open Inguinal Hernia. Repair. Ann Surg. 2018, 267, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasvang, E.; Kehlet, H. Surgical management of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2005, 92, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, N.; Tang, R. Functionalized Strategies and Mechanisms of the Emerging Mesh for Abdominal Wall Repair and Regeneration. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021, 7, 2064–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miserez, M.; Lefering, R.; Famiglietti, F.; Mathes, T.; Seidel, D.; Sauerland, S.; Korolija, D.; Heiss, M.; Weber, G.; Agresta, F.; et al. Synthetic Versus Biological Mesh in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hernia Repair (LAPSIS): Results of a Multinational, Randomized, Controlled, and Double-blind Trial. Ann Surg. 2021, 273, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Romano, G. Fixation-free inguinal hernia repair using a dynamic self-retaining implant. Surg Technol Int. 2012, 22, 107–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Agrusa, A.; Cocorullo, G.; Gulotta, G.; Goetze, T. Dynamic inguinal hernia repair with a 3d fixation-free and motion-compliant implant: a clinical study. Surg Technol Int. 2014, 24, 155–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Monte, A.I.L.; Cassata, G.; Damiano, G.; Romano, G.; Bussani, R. A New Prosthetic Implant for Inguinal Hernia Repair: Its Features in a Porcine Experimental Model. Artif. Organs 2011, 35, E181–E190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Agrusa, A.; Marasa, S.; Cocorullo, G.; Gulotta, G.; Goetze, T.; Puleio, R. Biologic Response of Inguinal Hernia Prosthetics: A Comparative Study of Conventional Static Meshes Versus 3D Dynamic Implants. Artif. Organs 2015, 39, E10–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Puleio, R.; Calò, P.G.; Goetze, T.; Romano, G. Neo-nervegenesis in 3D dynamic responsive implant for inguinal hernia repair. Qualitative study. Int J Surg 2020, 76, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Puleio, R.; Agrusa, A.; Goetze, T.; Gulotta, E.; Gordini, L.; Erdas, E.; Calò, P. Neomyogenesis in 3D Dynamic Responsive Prosthesis for Inguinal Hernia Repair. Artif. Organs 2018, 42, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Puleio, R.; Rodolico, V.; Agrusa, A.; Calò, P.G.; Di Buono GRomano, G.; Goetze, T. Enhanced angio-genesis in the 3D dynamic responsive implant for inguinal hernia repair S&S Hernia System®. Artif Organs. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa Puleio, R.; Micci, G.; Cassata, G.; Cicero, L.; Di Buono, G.; Calò, P.G.; Galia, M.; Ro-mano, G. A regenerative scaffold for inguinal hernia repair. MR imaging and histological cross evidence. Qualitative study. Int J Surg. 2021, 96, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klosterhalfen, B.; Junge, K.; Klinge, U. The lightweight and large porous mesh concept for hernia repair. Expert Rev. Med Devices 2005, 2, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, X.; Cheng, T.; Ji, Z.; Li, J. Long-Term Follow-Up of Lichtenstein Repair of Inguinal Hernia in the Morbid Patients With Self-Gripping Mesh (ProgripTM). Front. Surg. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Xie, W.X.; Li, S.; Wang, D.C.; Huang, L.Y. Meta-analysis of mesh-plug repair and Lichtenstein repair in the treatment of primary inguinal hernia. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, M.; Rohr, S.; Romain, B. Inguinal hernia repair using the Lichtenstein technique under local anesthesia (with video). J. Visc. Surg. 2021, 158, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehlet, H.; Bay-Nielsen, M.; for the Danish Hernia Database Collaboration. Nationwide quality improvement of groin hernia repair from the Danish Hernia Database of 87,840 patients from 1998 to 2005. Hernia 2007, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Chen, J. Treatment of mesh infection after inguinal hernia repair: 3-year experience with 120 patients. Hernia 2022, 27, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veenendaal, N.; Foss, N.B.; Miserez, M.; Pawlak, M.; Zwaans, W.A.R.; Aasvang, E.K. A narrative review on the non-surgical treatment of chronic postoperative inguinal pain: a challenge for both surgeon and anaesthesi-ologist. Hernia 2023, 27, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Agrusa, A.; Cocorullo, G.; Gulotta, G.; Goetze, T. Dynamic inguinal hernia repair with a 3d fixation-free and motion-compliant implant: a clinical study. Surg Technol Int. 2014, 24, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, G.; Romano, G.; Calò, P.G.; Di Buono, G.; Agrusa, A. First-in-man permanent laparoscopic fixation free obliteration of inguinal hernia defect with the 3D dynamic responsive implant S&S Hernia System-E®. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020, 77, S2–S7. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa Puleio, R.; Micci, G.; Cassata, G.; Cicero, L.; Di Buono, G.; Calò, P.G.; Galia, M.; Romano, G. A regenerative scaffold for inguinal hernia repair. MR imaging and histological cross evidence. Qualitative study. Int J Surg. 2021, 96, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Di Buono, G.; Calò, P.G.; Cassata, G.; Cicero, L.; Romano, G. Inguinal Hernia: Defect Obliteration with the 3D Dynamic Regenerative Scaffold S&S Hernia System™. Surgical Technology International 2021, 38, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amato, G.; Agrusa, A.; Calò, P.G.; Di Buono, G.; Buscemi, S.; Cordova, A.; Zanghì, G.; Romano, G. Fixation free laparoscopic obliteration of inguinal hernia defects with the 3D dynamic responsive scaffold S&S Hernia System. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 18971. [Google Scholar]

- Deponti, D.; Buono, R.; Catanzaro, G.; De Palma, C.; Longhi, R.; Meneveri, R.; Bresolin, N.; Bassi, M.T.; Cossu, G.; Clementi, E.; et al. The Low-Affinity Receptor for Neurotrophins p75NTR Plays a Key Role for Satellite Cell Function in Muscle Repair Acting via RhoA. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 3620–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Perini, A.; Dimauro, I.; Duranti, G.; Fantini, C.; Mercatelli, N.; Ceci, R.; Di Luigi, L.; Sabatini, S.; Caporossi, D. The p75NTR-mediated effect of nerve growth factor in L6C5 myogenic cells. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 686–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, K.; Yamaguchi, A. The Recent Understanding of the Neurotrophin′s Role in Skeletal Muscle Adaptation. BioMed Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 201696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibel, M.; Barde, Y.-A. Neurotrophins: key regulators of cell fate and cell shape in the vertebrate nervous system. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2919–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgaya, J.M.; Chan, J.R.; Shooter, E.M. The neurotrophin receptor p75NTR as a positive modulator of mye-lination. Science 2002, 298, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

(A) The Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System in its pre-delivery configuration, ready to be introduced into the abdominal cavity via a 12 mm trocar. - B: Outline of the S&S device in its fully deployed configuration. – C: Laparoscopic view after the placement of the S&S device in the right-sided defect. The mast has just been cut away and is being removed from the abdomen. A second defect in the lower left abdomen is visible, to be repaired with another S&S Hernia System. – D: Ultrasound scan 12 months post-surgery, displaying the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (red circle) now filled with newly developed tissue (yellow arrows).

Figure 1.

(A) The Stenting & Shielding (S&S) Hernia System in its pre-delivery configuration, ready to be introduced into the abdominal cavity via a 12 mm trocar. - B: Outline of the S&S device in its fully deployed configuration. – C: Laparoscopic view after the placement of the S&S device in the right-sided defect. The mast has just been cut away and is being removed from the abdomen. A second defect in the lower left abdomen is visible, to be repaired with another S&S Hernia System. – D: Ultrasound scan 12 months post-surgery, displaying the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (red circle) now filled with newly developed tissue (yellow arrows).

Figure 2.

The S&S Hernia System excised 3 months post-implantation. The 3D scaffold of the device is bisected, revealing viable tissue development within the scaffold.

Figure 2.

The S&S Hernia System excised 3 months post-implantation. The 3D scaffold of the device is bisected, revealing viable tissue development within the scaffold.

Figure 3.

Biopsy specimen excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Angiogenic clusters composed of developing vascular elements are seen adjacent to the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X) of the S&S device. Negligible inflammatory response to the device structure is noticeable. HE 50X.

Figure 3.

Biopsy specimen excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Angiogenic clusters composed of developing vascular elements are seen adjacent to the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X) of the S&S device. Negligible inflammatory response to the device structure is noticeable. HE 50X.

Figure 4.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). VEGF-positive endothelial elements of early-stage vascular structures (white spots) are visible near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). VEGF 100X).

Figure 4.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). VEGF-positive endothelial elements of early-stage vascular structures (white spots) are visible near the 3D scaffold of the S&S device (X). VEGF 100X).

Figure 5.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Clusters of vasculo-endothelial elements in early development (brown staining) are seen near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). CD31 100X.

Figure 5.

Biopsy sample excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Clusters of vasculo-endothelial elements in early development (brown staining) are seen near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). CD31 100X.

Figure 6.

Biopsy sample excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Sparse actin-positive vascular structures (brown staining) are detected near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 100X.

Figure 6.

Biopsy sample excised 5 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Sparse actin-positive vascular structures (brown staining) are detected near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 100X.

Figure 7.

Biopsy sample removed 5 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Several vascular structures (targeted elements) in advanced development are present near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X), with no detectable inflammatory response. HE 50X.

Figure 7.

Biopsy sample removed 5 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Several vascular structures (targeted elements) in advanced development are present near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X), with no detectable inflammatory response. HE 50X.

Figure 8.

Biopsy sample excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm –MT). Several arterial elements (yellow arrows) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). Adjacent to the growing muscular layer, VEGF-positive endothelial cells line the lumen of the vessels. VEGF 25X).

Figure 8.

Biopsy sample excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm –MT). Several arterial elements (yellow arrows) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). Adjacent to the growing muscular layer, VEGF-positive endothelial cells line the lumen of the vessels. VEGF 25X).

Figure 9.

Tissue sample excised 3 months post-implantation (Midterm – MT). Clusters of intense neo-angiogenesis (brown staining) in the intermediate-stage of vascular development are seen near the device’s fabric (X). CD31 100X.

Figure 9.

Tissue sample excised 3 months post-implantation (Midterm – MT). Clusters of intense neo-angiogenesis (brown staining) in the intermediate-stage of vascular development are seen near the device’s fabric (X). CD31 100X.

Figure 10.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm – MT). A venous structure (yellow arrows) showing smooth muscle development, induced by SMA, is seen near the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 50X.

Figure 10.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm – MT). A venous structure (yellow arrows) showing smooth muscle development, induced by SMA, is seen near the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 50X.

Figure 11.

Biopsy sample removed 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Well-formed convoluted arteries with thick muscular layers (yellow circle) and some veins (*) are embedded within newly developed muscle tissue (red) and adipose cells (white spots) surrounding the TPE scaffold (X). No inflammatory response is evident. HE 50X.

Figure 11.

Biopsy sample removed 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Well-formed convoluted arteries with thick muscular layers (yellow circle) and some veins (*) are embedded within newly developed muscle tissue (red) and adipose cells (white spots) surrounding the TPE scaffold (X). No inflammatory response is evident. HE 50X.

Figure 12.

Biopsy specimen excised from the S&S device 7 months post-implantation (Long term – LT). VEGF-positive elements compose the endothelial layer of a large vein (yellow arrows) and one artery (*) close to the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). VEGF 25X.

Figure 12.

Biopsy specimen excised from the S&S device 7 months post-implantation (Long term – LT). VEGF-positive elements compose the endothelial layer of a large vein (yellow arrows) and one artery (*) close to the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). VEGF 25X.

Figure 13.

Biopsy specimen excised 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Mature endothelial elements of vessel structures (brown staining) are visible close to the TPE scaffold (X). CD31 50X.

Figure 13.

Biopsy specimen excised 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Mature endothelial elements of vessel structures (brown staining) are visible close to the TPE scaffold (X). CD31 50X.

Figure 14.

Biopsy specimen excised 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Thick muscular layers (stained in brown) of vascular elements are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 50X.

Figure 14.

Biopsy specimen excised 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Thick muscular layers (stained in brown) of vascular elements are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). SMA 50X.

Figure 15.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). A large number of NGF-positive elements (brown staining) are seen near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 50X.

Figure 15.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). A large number of NGF-positive elements (brown staining) are seen near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 50X.

Figure 19.

Biopsy specimen excised 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Numerous NGF-positive elements in elongated bundles (brown staining) are visible near the structure of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 100X.

Figure 19.

Biopsy specimen excised 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Numerous NGF-positive elements in elongated bundles (brown staining) are visible near the structure of the 3D scaffold (X). NGF 100X.

Figure 20.

Biopsy specimen excised 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). A significant number of muscle bundles (red staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X), surrounded by viable connective tissue (colored in blue) and areas of adipocytes (white spotted elements). A large arterial structure is also visible (*). AM 25X.

Figure 20.

Biopsy specimen excised 6 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). A significant number of muscle bundles (red staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X), surrounded by viable connective tissue (colored in blue) and areas of adipocytes (white spotted elements). A large arterial structure is also visible (*). AM 25X.

Figure 21.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). NGFRp75-positive cells (beige/brown staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 100X.

Figure 21.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). NGFRp75-positive cells (beige/brown staining) are evident near the TPE fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 100X.

Figure 22.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Nervous elements (brown staining) in the initial stages of development are present close to the 3D scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 22.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 weeks post-implantation (Short term - ST). Nervous elements (brown staining) in the initial stages of development are present close to the 3D scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 23.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). NGFRp75-positive elements (brown staining) are evident near the fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 50X.

Figure 23.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). NGFRp75-positive elements (brown staining) are evident near the fabric of the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 50X.

Figure 24.

Biopsy sample excised 5 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Two developing nerve elements (yellow circles) are observed near broad venous structures (*) and a midsized artery (yellow arrows) in proximity to the TPE scaffold. NSE 50X.

Figure 24.

Biopsy sample excised 5 months post-implantation (Midterm - MT). Two developing nerve elements (yellow circles) are observed near broad venous structures (*) and a midsized artery (yellow arrows) in proximity to the TPE scaffold. NSE 50X.

Figure 25.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). NGFRp75-positive elements (brown staining) are seen close to the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 50X.

Figure 25.

Biopsy specimen excised 4 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). NGFRp75-positive elements (brown staining) are seen close to the 3D scaffold (X). NGFRp75 50X.

Figure 26.

Biopsy sample removed 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Elongated nerve elements (brown staining) in advanced development are present near the 3D scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Figure 26.

Biopsy sample removed 7 months post-implantation (Long term - LT). Elongated nerve elements (brown staining) in advanced development are present near the 3D scaffold (X). NSE 100X.

Table 1.

Technical properties of the TPE material used for the injection molding of the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System.

Table 1.

Technical properties of the TPE material used for the injection molding of the Stenting & Shielding Hernia System.

| TPE technical properties |

Value |

Unit |

Test Standard |

| ISO Data |

| Tensile Strength |

16 |

MPa |

ISO 37 |

| Strain at break |

650 |

% |

ISO 37 |

| Compression set at 70 °C, 24h |

54 |

% |

ISO 815 |

| Compression set at 100 °C, 24h |

69 |

% |

ISO 815 |

| Tear strength |

46 |

kN/m |

ISO 34-1 |

| Shore A hardness |

89 |

- |

ISO 7619-1 |

| Density |

890 |

kg/m³ |

ISO 1183 |

Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry antibodies used for processing biopsy specimens.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry antibodies used for processing biopsy specimens.

| Antibody |

Clone-Code |

Source |

Dilution |

| NSE |

LS-B14144 (LLSBio) |

Rabbit polyclonal |

1:100 |

| CD31 |

JC70A (DAKO) |

Mouse monoclonal |

1: 50 |

| SMA |

1A4 (DAKO) |

Mouse monoclonal |

1:100 |

| VEGF |

26503 (R&D) |

Mouse monoclonal |

1:50 |

| NGF |

Ab52918 (Abcam) |

Rabbit monoclonal |

1:100 |

| NGFRp75 |

Sc 13577 (Santa Cruz) |

Mouse monoclonal |

1:100 |

Table 3.

Stages of cellular development & growth factors evidenced in the S&S Hernia System over time. Growth factors evidence: + = limited ++ = noteworthy +++ abundant.

Table 3.

Stages of cellular development & growth factors evidenced in the S&S Hernia System over time. Growth factors evidence: + = limited ++ = noteworthy +++ abundant.

| |

Growth factors |

Tissue structures |

| |

VEGF |

CD31 |

SMA |

NGF |

NGFRp75 |

Vessels |

Muscles |

Nerves |

| Short term |

+++ |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

Evolving |

Evolving |

Evolving |

| Midterm |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

Advanced |

Advanced |

Advanced |

| Long term |

+ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

Mature |

Mature |

Mature |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).