1. Introduction

DNA methylation at CpG sites in mammalian cells is a crucial epigenetic modification that underpins the regulation of gene expression, development, genomic imprinting, and other cellular processes [

1,

2,

3]. The cytosine methylation pattern is bimodal: highly methylated intragenic regions with high CpG methylation level coexist with CpG islands—methylation-depleted regions of high CpG density—typically located in the promoters of actively transcribed genes [

4,

5,

6]. This pattern is maintained through the dynamic balance of enzymatic DNA methylation and active or passive demethylation processes [

7]. The initial establishment of DNA methylation patterns occurs during early development and is mediated by the de novo DNA methyltransferases (MTases) Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b [

8]. Maintenance of these patterns during DNA replication is primarily carried out by Dnmt1.

Methylation involves the transfer of a methyl group from the donor molecule S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) to the C5 position of cytosine residues at CpG sites. This reaction is catalyzed by the C-terminal catalytic domain of DNMT3A/3B, which form linear tetramers with two active sites in association with the catalytically inactive DNMT3L [

8,

9]. In addition to its catalytic domain, DNMT3a contains an N-terminal regulatory region composed of PWWP (Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro) [

10] and ADD (ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L) [

11] domains. These domains facilitate specific recruitment of the MTase tetramer to distinct genomic regions by recognizing histone marks, such as methylated (H3K36me2/3 [

12]), unmethylated (H3K4me0 [

13]), or ubiquitinylated (H2AK119ub [

14]) residues [

15].

Simultaneously, an increasing body of evidence highlights an additional layer of regulation in MTase activity, mediated by interactions with noncanonical DNA structures, particularly G-quadruplexes (G4s) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. G4s are formed through the stacking of G-tetrads—planar arrangements of four guanines stabilized by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds and centrally located monovalent cations, such as K⁺ or Na⁺ [

23,

24]. G4 structures are classified based on strand polarity: (i) parallel, where all four strands run in the same direction; (ii) antiparallel, where two pairs of strands run in opposite directions; and (iii) hybrid, where three strands run in one direction and the fourth strand runs in the opposite direction [

24]. Thus, the activity of MTases in a given genomic region is influenced by a complex integration of signals from histone modifications, the enzyme’s intrinsic sequence specificity [

25], protein multimerization [

26], and noncanonical DNA structures. This interplay makes it challenging to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the de novo establishment of DNA methylation pattern.

Whole-genome sequencing studies of the epigenome have further underscored the role of noncanonical DNA structures in shaping DNA methylation landscapes [

20]. A notable correlation has been observed across various tissues: genomic regions enriched in G4 structures tend to exhibit low CpG methylation, whereas regions with high CpG methylation are relatively depleted of G4s. These findings demonstrate that G4 structures act as a genome-wide impediment to CpG site methylation. This observation is particularly significant, given that cytosine methylation plays a critical role in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in mammals. Aberrant methylation patterns are frequently associated with cancer and other diseases [

27,

28,

29], highlighting the importance of understanding the interplay between DNA methyltransferase activity and alternative DNA structures.

Recent studies have shown a high density of potential G-quadruplex-forming sequences (PQS) in the promoters of human DNA repair genes [

30]. Using various experimental approaches, it has been demonstrated that some of the identified PQSs indeed fold into G4 structures both in vitro and in vivo. Among these, the

MGMT gene has been studied, which encodes an enzyme responsible for the repair of alkylated guanine residues [

31,

32]. This enzyme, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), restores damaged (alkylated) guanine by transferring the methyl group from the O6 position of guanine to a cysteine residue in the protein. This mechanism prevents gene mutations, cell death, and oncogenesis caused by alkylating agents [

31]. The expression of the

MGMT gene is primarily regulated by epigenetic modifications, specifically the methylation of the CpG island within the

MGMT promoter (MGMTp). When the promoter is methylated at CpG sites, the synthesis of the MGMT repair enzyme is significantly reduced, leaving alkylation-induced damage unrepaired. Under these conditions, chemotherapy with alkylating agents targeting cancer cells becomes a viable treatment option. Therefore, determining the methylation status of the

MGMT promoter is critically important [

33].

MGMTp is considered a marker of precancerous lesions and a biomarker for the early diagnosis of various tumors, including gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, and cervical carcinoma [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. It has also acquired a key diagnostic role for brain tumor lesions, serving as a molecular biomarker for selecting anti-cancer therapies [

39]. However, several challenges remain for its clinical application, such as achieving consensus on MGMTp methylation detection methods, as these methods vary significantly across laboratories. Additionally, optimal MGMTp methylation thresholds for glioblastoma diagnostics are still lacking [

40]. The CpG island in the MGMTp region contains several PQSs, raising the question of their potential influence on Dnmt3a activity, which is responsible for de novo DNA methylation and establishing the MGMTp methylation pattern. Previously, we reported a crosstalk between G4 structures and Dnmt3a-mediated methylation of the

c-MYC oncogene promoter [

19].

In this study, we explored the mechanistic aspects of de novo Dnmt3a in the MGMTp, with a focus on the influence of DNA sequence context and noncanonical structures on the methylation process. Using an in vitro methylation model, we examined how G4 structures affect DNA methyltransferase activity. Understanding the mechanisms that shape methylation patterns in MGMTp not only provides a deeper insight into the biology of de novo DNA methylation but also holds the potential to explain variability in clinical data and may enhance the utility of MGMTp methylation as a biomarker for disease prognosis and treatment.

2. Results

2.1. MGMTp PQS Reduces the Accuracy of Modified Base Identification in Nanopore Sequencing Data

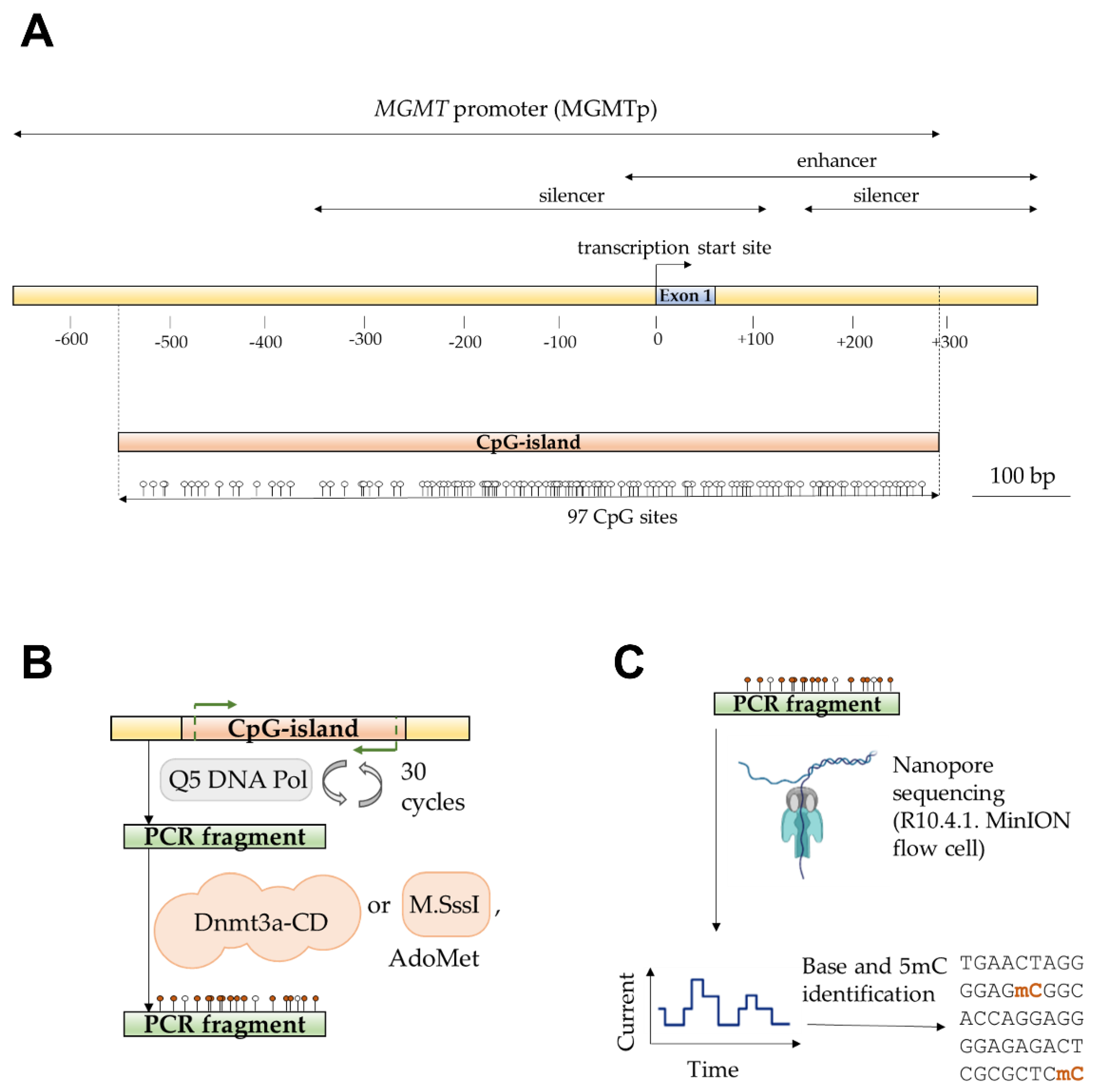

In this work, we focused on studying the methylation of a G/C-rich region of MGMTp that contains a CpG island overlapping with the first exon (

Figure 1A). The sequence of interest included CpG sites 3-97 out of 97 CpG sites within the island. The 752-base pair (bp) long sequence was amplified from Raji human lymphoblast-like cell line genomic DNA, and the resulting PCR product was referred to as MGMT-752 (

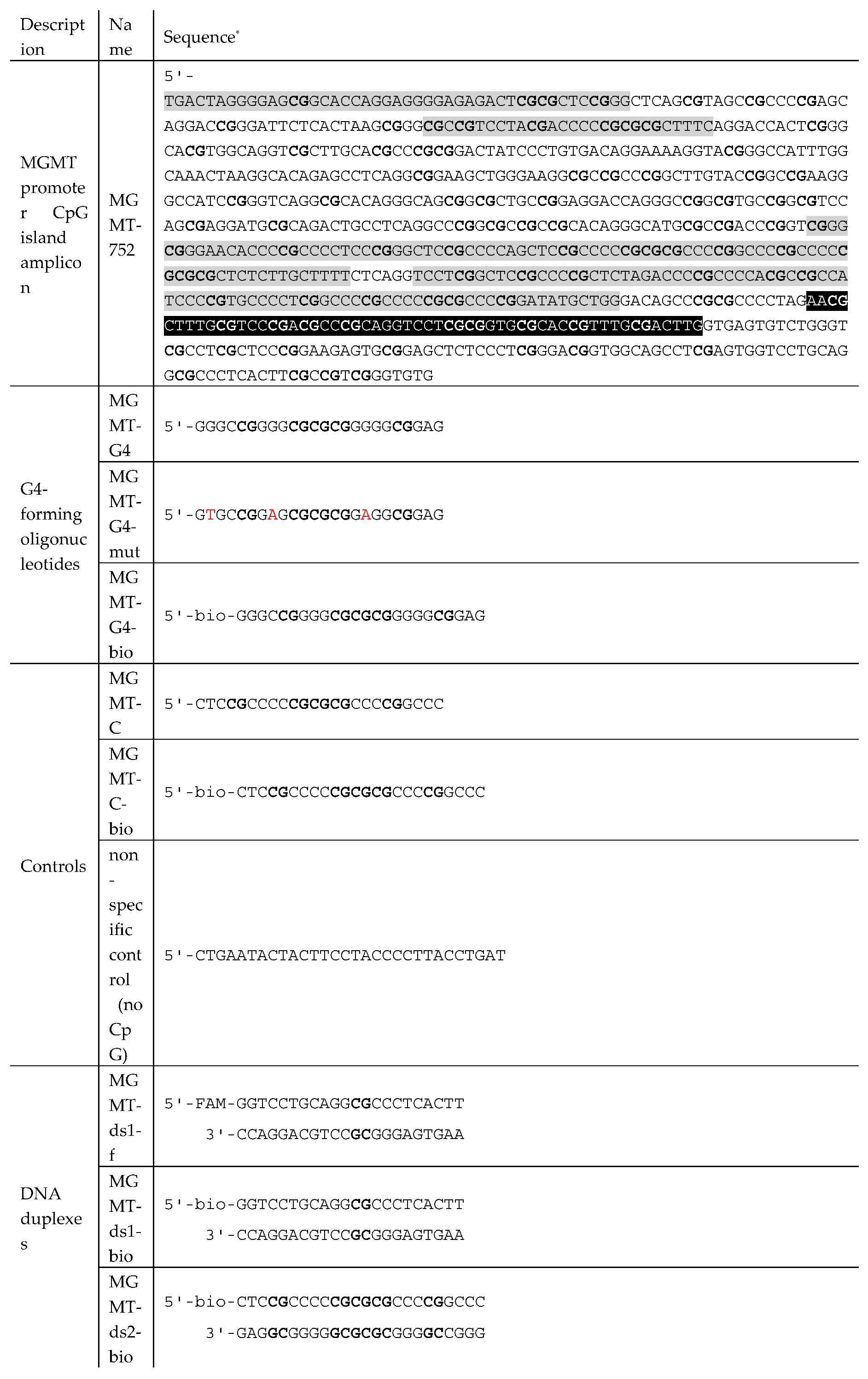

Table 1).

Then, we examined the efficiency of

de novo methylation of MGMT-752 by the catalytic domain of mouse MTase Dnmt3a (Dnmt3a-CD), which is identical in amino acid sequence to the human enzyme, and is catalytically active in absence of its N-terminal chromatin-targeting part [

41]. To this end, MGMT-752 duplex was enzymatically methylated by Dnmt3a-CD in the presence of methyl group donor AdoMet (

Figure 1B). For comparison, a portion of MGMT-752 was methylated by a procaryotic monomeric C5 MTase M.SssI from

Spiroplasma sp. strain MQ1 that targets CpG sites, while the control sample was left unmethylated.

Figure 1.

Detection of MGMTp CpG island methylation by nanopore sequencing.

A. Schematic representation of MGMTp; the region containing the CpG island is shown. Figure based on [

42] and NCBI (Gene ID: 4255).

B. PCR amplification and

in vitro methylation of a MGMTp region containing CpG sites 3-97 using Dnmt3a-CD or M.SssI.

C. Schematic representation of nanopore sequencing of methylated PCR product and detection of 5mC.

Figure 1.

Detection of MGMTp CpG island methylation by nanopore sequencing.

A. Schematic representation of MGMTp; the region containing the CpG island is shown. Figure based on [

42] and NCBI (Gene ID: 4255).

B. PCR amplification and

in vitro methylation of a MGMTp region containing CpG sites 3-97 using Dnmt3a-CD or M.SssI.

C. Schematic representation of nanopore sequencing of methylated PCR product and detection of 5mC.

To determine the enzymatic CpG methylation patterns of the amplicons, we employed nanopore sequencing. Purified DNA samples were analyzed using the Mk1B sequencing device equipped with a MinION Flow Cell (R10.4.1) (

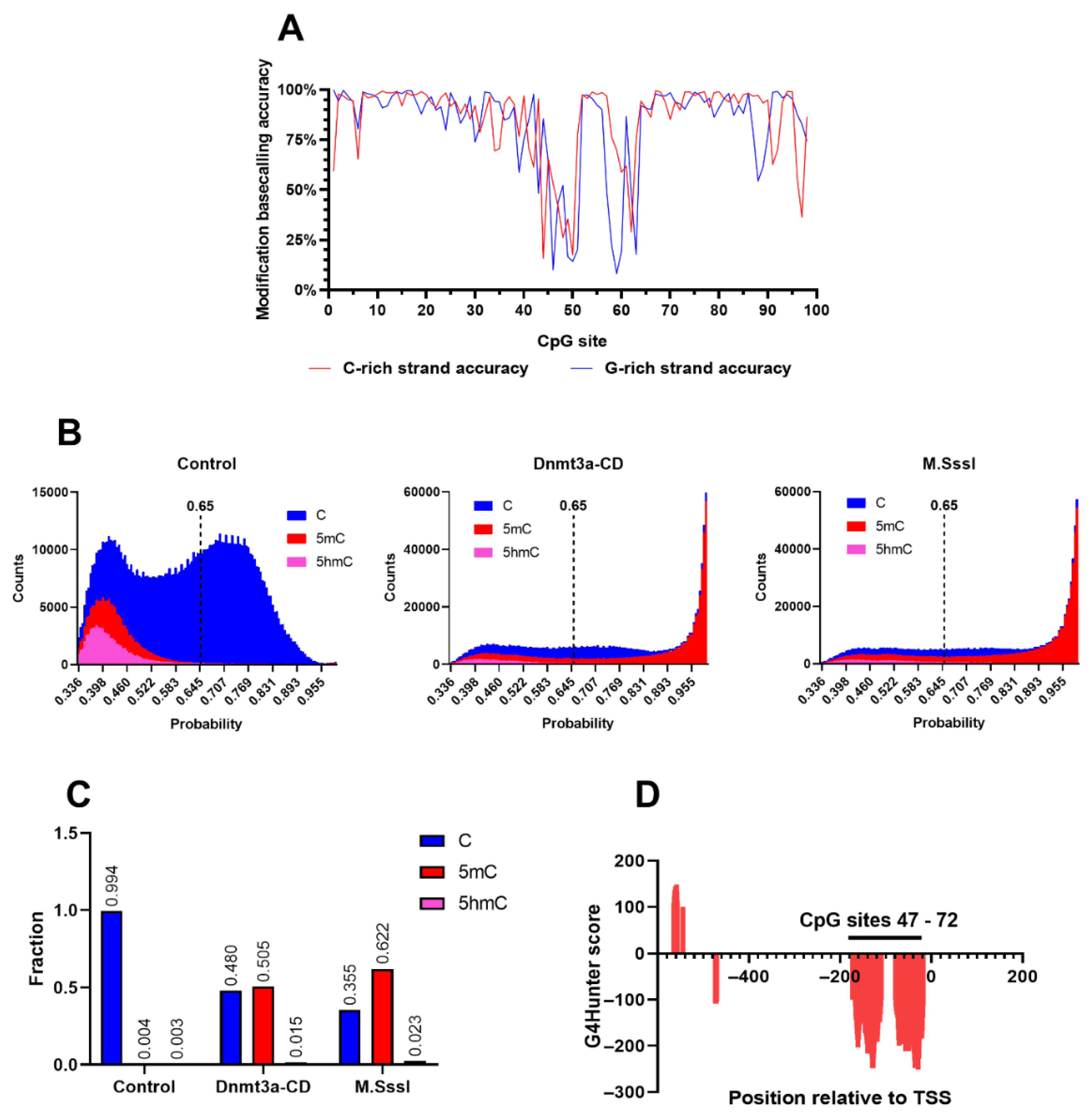

Figure 1C). The sequencing run generated 140,670 reads, yielding 117.69 megabases (Mb) of nucleotide data, which was subsequently mapped to the GRCh38.p14 reference human genome assembly. In addition to detecting 5-methylcytosine (5mC), the basecalling model used in the analysis also supported the identification of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). Although 5hmC was not present in the tested samples, its detection served as a quality control measure for assessing the accuracy of the modification model. Using the unmethylated control amplicon as a reference, the 5mC probability distribution was plotted to evaluate modification calling accuracy across the region of interest. The accuracy distribution, generated with the Modkit pileup tool, was separately visualized for the C-rich (coding) and G-rich (template) DNA strands of the control amplicon (

Figure 2A). Unexpectedly, an anomalous region between CpG sites 40 and 65 exhibited a marked reduction in modification calling accuracy for both DNA strands, with the probability of correctly identifying unmethylated cytosines reaching as low as 25%. In contrast, accuracy across the remainder of the region consistently exceeded 75%, except at the 5’- and 3’- ends of the amplicon, where lower sequencing quality is a well-documented artifact [

43].

To determine the extent of false positive modification calls in the unmethylated sample, the probability distributions for all three cytosine variants – canonical, 5mC and 5hmC – were plotted for control, Dnmt3a-CD- and M.SssI- treated amplicons (

Figure 2B). A significant amount of low-confidence, erroneous 5mC and 5hmC calls were detected in the control amplicon, likely corresponding to the low accuracy region between CpG sites 47 – 72. A number of 5hmC calls were also present in the methylated samples in the same low confidence interval. To account for these inaccuracies and exclude the erroneous modification calls, a confidence threshold of 0.65 was used in the following analyses. Next, total amount of modified cytosines was calculated for all three studied amplicons. The 5mC levels were 0.04, 0.505 and 0.622 for control, Dnmt3a-CD- and M.SssI- treated amplicons, respectively, with all three samples exhibiting a low level (< 0.03) of high-confidence 5hmC calls. These calls were considered insignificant in the following analyses, and raising the confidence threshold further would invalidate a large number of correct modification calls. Surprisingly, the anomalous region of low modification calling accuracy closely coincided with the PQSs in the MGMTp CpG island, predicted using G4Hunter® software (

Figure 2D). Therefore, the accuracy of detecting modified bases in PQS was significantly reduced compared to the surrounding sequences (

Figure 2A,D)

2.2. Differential Methylation of MGMTp DNA Strands by Dnmt3a-CD

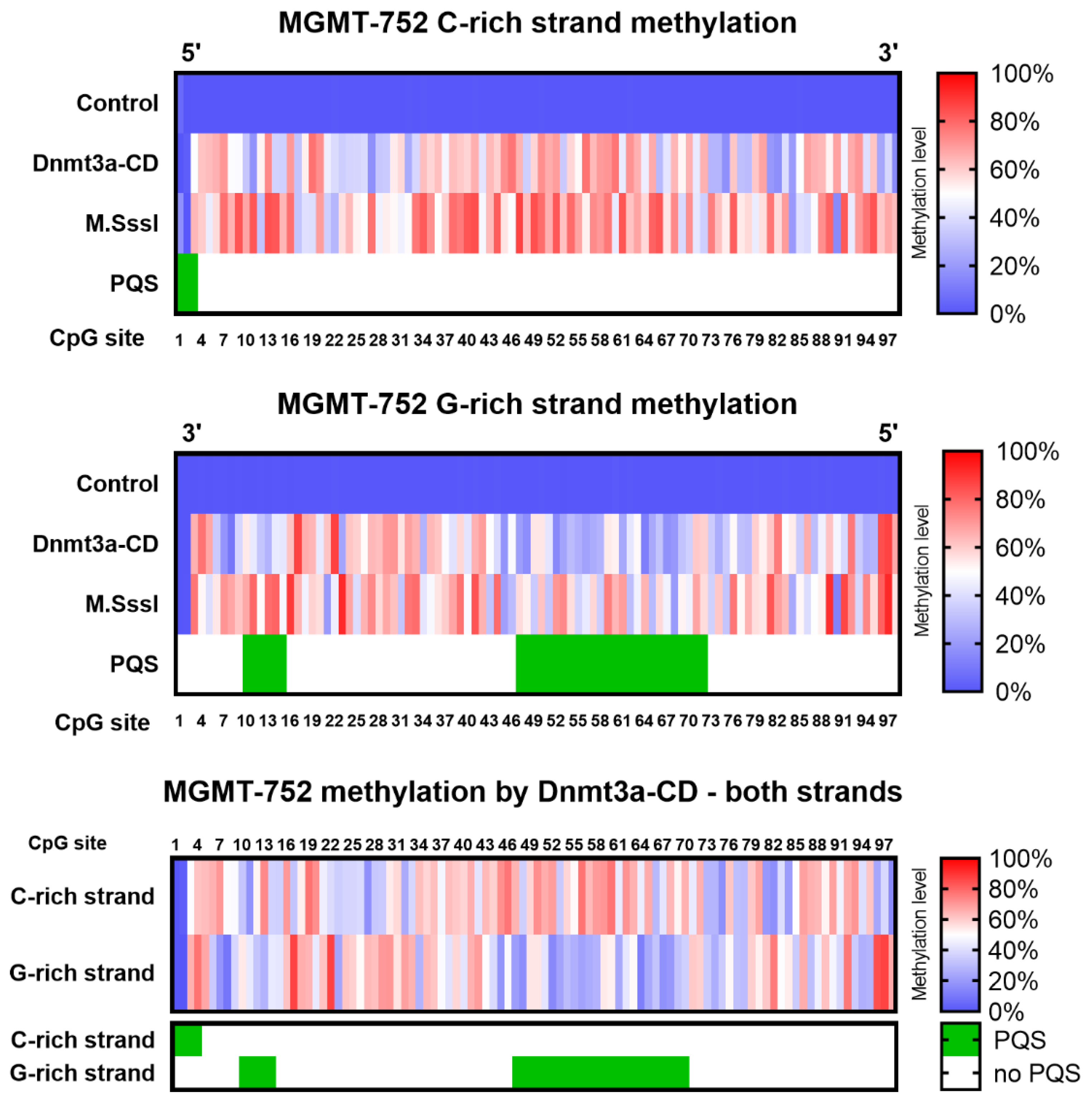

The cytosine methylation patterns of the analyzed amplicons were next examined (

Figure 3). Single-molecule sequencing allowed to differentiate the methylation patterns of the DNA strands. Control amplicons were uniformly unmethylated, whereas MTase-treated molecules exhibited methylation patterns that varied depending on the DNA strand and the enzyme used.

Unexpectedly, both Dnmt3a-CD and M.SssI exhibited differential methylation patterns between the C- and G-strands of the amplicon, with the C-strand generally displaying higher 5mC levels. Notably, amplicons treated with Dnmt3a-CD revealed a region of pronounced strand-specific methylation differences spanning CpG sites 47 to 72 (

Figure 3, bottom panel). Interestingly, this region corresponded to an area previously identified as having reduced modification-calling accuracy and overlapped with the PQS in MGMTp, as predicted by G4Hunter software (

Figure S1A). Specifically, the G-rich DNA strand in the primary PQS region displayed significantly lower methylation levels compared to its complementary C-rich strand (33% ± 3% vs. 58% ± 3%, respectively; P value < 0.0001) (

Figure S1B). On the other hand, the difference of methylation efficiency between DNA strands outside of the primary PQS was not significant (47% ± 3% vs. 49% ± 3%, for G-rich and C-rich strands, respectively; P value 0.40) (

Figure S1C). These findings suggest a possible relationship between the presence of PQS and the regulation of de novo methylation at CpG sites within these sequences. While the PQSs in the MGMT-752 amplicon are unlikely to form stable G4 structures due to competition with the energetically favorable B-form DNA duplex, MGMTp PQSs have been shown to adopt G4 folds in human cells [

30]. Consequently, the next objective of this study was to assess the effect of MGMTp G4 structures on methylation efficiency and to determine the extent to which these differences could be attributed to the presence of G4s [

16] or MTase sequence preferences [

25].

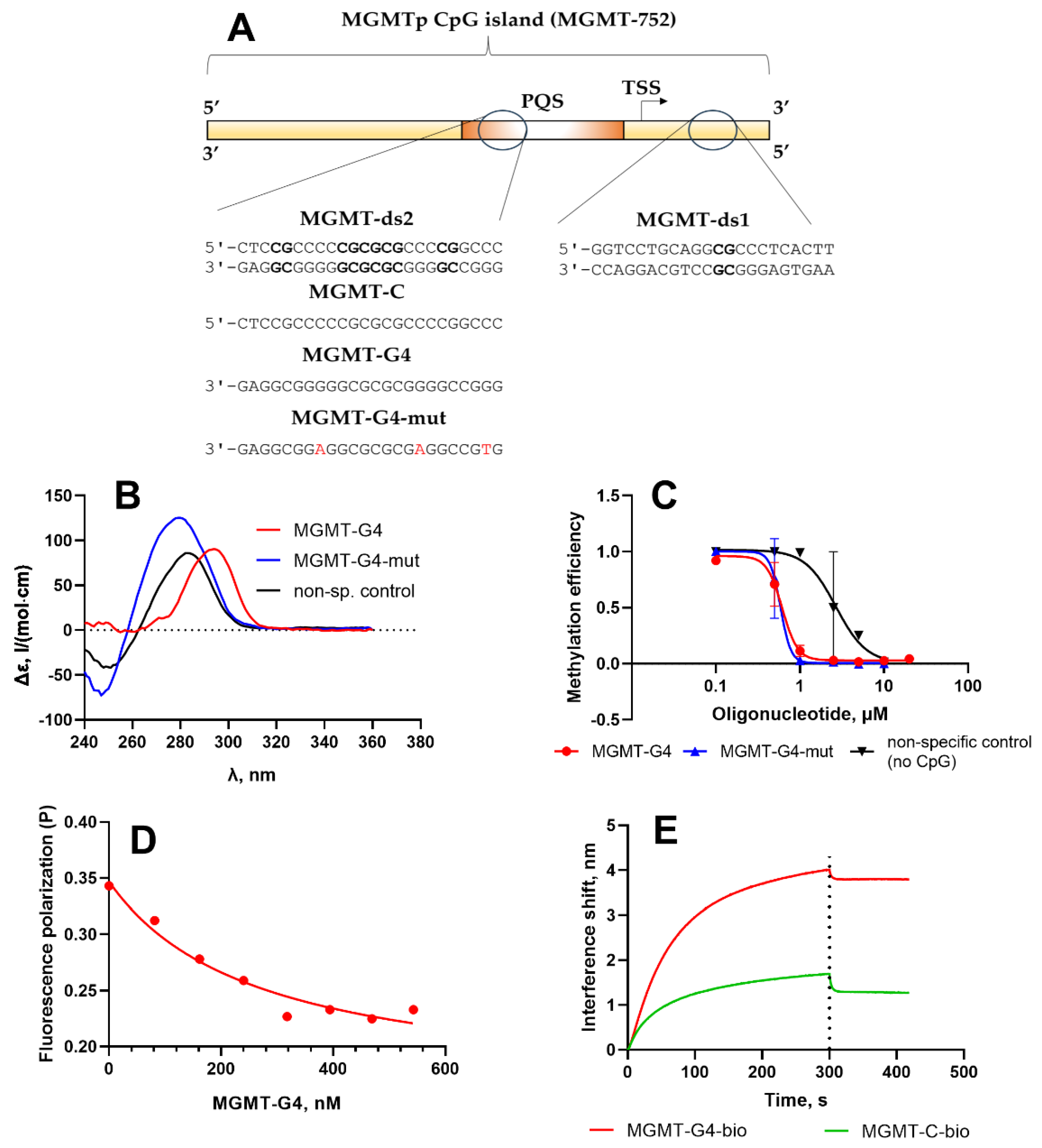

2.3. MGMTp PQS and G4 Structures form Stable Complexes with Dnmt3a-CD and Inhibit Its Methylation Activity

For this study, we selected a range of short DNA duplexes and oligonucleotides derived from the MGMTp CpG island (

Figure 4A). These included a 24-bp double-stranded DNA fragment, MGMT-ds2, from the MGMTp PQS; its G-rich strand, MGMT-G4; and an analog, MGMT-G4-mut, which contained guanine substitutions designed to inhibit G4 formation (

Table 1). Additionally, a C-rich oligonucleotide, MGMT-C, and a 24-bp DNA duplex from outside the PQS region (MGMT-ds1) were included. As a reference, a non-specific control oligonucleotide lacking CpG sites (non-sp. control) was also utilized.

The secondary structures of the single-stranded DNA fragments were analyzed using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (

Figure 4B). The MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide displayed a positive peak at 295 nm, indicative of a hybrid quadruplex structure characterized by a combination of parallel and antiparallel DNA strands [

44]. In contrast, the MGMT-G4-mut oligonucleotide exhibited no evidence of noncanonical structures; its CD spectrum closely resembled that of the single-stranded non-specific control. Earlier, it was shown that a 24-bp oligonucleotide representing the MGMT promoter PQS exhibited CD spectra characteristic of a parallel G4 structure [

30]. In contrast, our findings suggest a mixed-hybrid G4 folding conformation for the MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide (

Figure 4A). This difference may result from our oligonucleotide covering a slightly different region of the same PQS, incorporating more downstream and fewer upstream nucleotides in the sequence (

Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Molecular characterization of interaction of MGMTp G4 oligonucleotides with Dnmt3a-CD. A. Short oligonucleotides and DNA duplexes based on MGMTp CpG island. B. Circular dichroism studies of MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide and non-G4-forming controls (

Table 1). C. Inhibition of methylation of a double-stranded Dnmt3a substrate MGMT-ds1-f by Dnmt3a-CD in the presence of MGMT-G4. Error bars represent SD from at least two independent experiments. D. Displacement of MGMT-ds1-f from the complex with Dnmt3a-CD studied by fluorescence polarization. E. Binding of MGMT-G4 to Dnmt3a-CD studied by biolayer interferometry. The experiments were conducted in buffer A.

Figure 4.

Molecular characterization of interaction of MGMTp G4 oligonucleotides with Dnmt3a-CD. A. Short oligonucleotides and DNA duplexes based on MGMTp CpG island. B. Circular dichroism studies of MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide and non-G4-forming controls (

Table 1). C. Inhibition of methylation of a double-stranded Dnmt3a substrate MGMT-ds1-f by Dnmt3a-CD in the presence of MGMT-G4. Error bars represent SD from at least two independent experiments. D. Displacement of MGMT-ds1-f from the complex with Dnmt3a-CD studied by fluorescence polarization. E. Binding of MGMT-G4 to Dnmt3a-CD studied by biolayer interferometry. The experiments were conducted in buffer A.

To evaluate the impact of the G4 structure on Dnmt3a-CD function, we investigated the inhibition of the methylation reaction of the fluorescently tagged MGMT-ds1-f duplex by oligonucleotides MGMT-G4 and controls (

Table 1), following a previously established methodology (

Figure 4C) [

19]. MGMT-ds1-f was a 22-bp DNA duplex containing a single central CpG site, derived from a region of the MGMTp CpG island located outside the PQS. Methylation efficiency was measured by protection of methylated DNA from digestion by restriction endonuclease Hin6I. In the absence of MGMT-G4, the MGMT-ds1-f duplex was almost fully methylated by Dnmt3a-CD. However, as the concentration of MGMT-G4 increased, the degree of MGMT-ds1-f methylation decreased, indicating inhibition of Dnmt3a-CD activity (

Figure S2). The IC

50 value, derived from the plot of methylation fraction as a function of MGMT-G4 concentration (

Figure 4C), was 0.61 ± 0.03 µM. In contrast, the control oligonucleotide without CpG sites (non-sp. control,

Table 1) demonstrated significantly weaker inhibition of Dnmt3a-CD activity (IC

50 2.4 ± 0.7 µM). Interestingly, the MGMT-G4-mut, which, according to CD data, lacks a G4 structure, exhibited a similar level of inhibition as MGMT-G4 (IC

50 0.59 ± 0.09 µM). In this case, the presence of multiple CpG repeats in MGMT-G4-mut may promote the formation of transient double-stranded structures, resulting in a high affinity for Dnmt3a-CD. Therefore, the G4-forming oligonucleotide MGMT-G4, derived from the MGMTp PQS, effectively inhibited the methylation reaction by tightly binding to Dnmt3a-CD and preventing the MTase from binding to its regular double-stranded substrate.

The mechanism of Dnmt3a-CD interaction with guanine-rich DNA sequences is supported by the results of a DNA displacement experiment involving the Dnmt3a-CD/MGMT-ds1-f complex. Using fluorescence polarization, it was shown that the addition of the unlabeled guanine-rich sequence MGMT-G4, capable of forming a G4, to the Dnmt3a-CD/MGMT-ds1-f complex leads to a decrease in fluorescence polarization signal (

Figure 4D). This indicates that the FAM-labeled DNA duplex is displaced by the MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide from the enzyme’s binding site.

Next, bio-layer interferometry (BLI) was employed to investigate the interaction between MGMTp G4 structures or PQS sequences and Dnmt3a-CD, as well as to evaluate their properties as MTase substrates. Biotinylated DNA substrates were immobilized on streptavidin-coated biosensors. The experiment consisted of an association phase, during which the DNA substrates interacted with Dnmt3a-CD, followed by a dissociation phase to observe the stability of the complexes.

The BLI results demonstrate that Dnmt3a-CD binds to MGMT-ds1-bio and MGMT-ds2-bio with high affinity (

Figure S3). The dissociation constants (

Kd) of the DNA-protein complexes varied by a factor of 4, depending on the number of CpG-sites and the presence of G clusters (

Table 2), with the guanine-rich duplex MGMT-ds2-bio binding to Dnmt3a-CD more strongly than the MGMT-ds1-bio duplex. Furthermore, notable differences were observed in the binding affinity of Dnmt3a-CD to complementary cytosine- and guanine-rich DNA strands of MGMT-ds2-bio (

Figure 4E). The guanine-rich strand MGMT-G4-bio binds to the protein similarly to G/C-rich MGMT-ds2-bio and 14 times more strongly than its complementary cytosine-rich strand MGMT-C-bio, confirming the high affinity of Dnmt3a-CD for G4 structures [

16]. These findings are supported by the results of a DNA displacement experiment (

Figure 4D).

3. Discussion

In this study, we characterized, for the first time, the de novo methylation pattern of a long model DNA fragment from MGMTp using a Dnmt3a-CD-based in vitro methylation system (

Figure 1). Utilizing nanopore sequencing for the direct detection of methylation products (

Figure 2), we identified strand-specific effects and a distinct methylation pattern for Dnmt3a (

Figure 3). Specifically, the region of strand-dependent Dnmt3a-mediated methylation coincided with the MGMTp PQS identified by G4Hunter algorithm, leading to highly uneven methylation across the 97 CpG positions of MGMTp.

The observed preferential methylation of the C-rich strand could be attributed to Dnmt3a’s known strong flanking sequence preference [

45], favoring CpG sites followed by cytosines and thymines. Dnmt3a’s distributive mechanism necessitates either dissociation and rebinding to hemimethylated CpG sites to methylate the complementary strand or the binding of a second tetramer to the same site [

26]. In contrast, the effects were less pronounced with the monomeric CpG recognizing MTase M.SssI, which in spite of strong homology to ten conserved regions of the tetramerDnmt3a-CD exhibits a differently arranged complex with DNA [

46,

47]. Thus, one can suggest that in the context of a PQS with a high density of CpG sites, Dnmt3a tetramers may preferentially methylate CpGs with favorable nucleotide contexts on the C-rich strand, resulting in the accumulation of hemimethylated CpG sites.

The accuracy of 5mC detection within the MGMTp PQS using nanopore sequencing data was significantly lower than for surrounding sequences, underscoring the need for improved modified basecalling models. This limitation, coupled with known challenges in nanopore sequencing of homopolymer regions—such as cytosine and guanine repeats in PQSs [

43]—highlights the importance of considering such sequences in the development and refinement of basecalling algorithms.

The alignment of strand-specific methylation sites with PQS regions (

Figure 3) suggested an influence of these structures on methylation in human cells. G4 structures might form locally in the G-rich strand, potentially affecting the catalytic activity of Dnmt3a-CD (

Figure 4). The differences in the dissociation constants of Dnmt3a-CD complexes with MGMTp DNA duplexes and oligonucleotides were also revealed (

Table 2). One possible explanation is that G4 structures, formed locally on the G-rich strand, may provide an independent interaction site for DNMT3a-CD, attracting the enzyme to G4s and resulting in hypomethylation of the surrounding regions. At the same time, if the double stranded form is preserved, increased methylation can be expected in PQS.

The characteristic G4-associated methylation pattern observed in brain tumor samples aligns with our findings. This pattern, as reported by Shah

et al. (2011) in their comprehensive analysis of MGMT promoter methylation and its correlation with MGMT expression and clinical response in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [

48], strongly supports the conclusion that this is a result of de novo methylation rather than a malfunction of the maintenance MTase.

The ability of PQS from MGMTp to fold into G4 structures upon interaction with G4-specific ligands in human glioblastoma cells was demonstrated by Fleming

et al. in 2018 [

30]. This finding was supported by bioinformatic analysis and circular dichroism (CD) experiments. However, these results and our CD experiments using short DNA oligonucleotides may not directly reflect the precise topology of MGMT promoter PQS G4 structures within human cells. Instead, they provide evidence supporting the potential for G4 formation in the studied region. Further studies are needed to clarify the interplay between strong flanking sequence preference and interaction with histone and noncanonical structures in de novo methylation of MGMTp CpG island by Dnmt3a.

Our findings also necessitate a reevaluation of research data obtained using methods such as the OneStep qMethyl™ Kit from Zymo Research [

49]. This kit detects locus-specific DNA methylation by selectively amplifying methylated regions of DNA and comparing them to human non-methylated DNA. The reference DNA is purified from cells with genetic knockouts of both DNMT1 and DNMT3b DNA methyltransferases, resulting in a low level of DNA methylation (~5%) [

50]. In the context of MGMTp, the application of this kit must be reconsidered, as the presence of PQS could influence the interpretation of methylation levels and compromise the accuracy of the results.

4. Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotides (

Table 1) were commercial products (Genterra, Moscow, Russia). Some of the oligonucleotides contained biotin or the fluorescent label 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). The concentrations of the oligonucleotides were determined spectrophotometrically. AdoMet was purchased from Sigma (Steinheim, Germany). DNA duplexes and G4 structures were formed using by heating at 95 ◦C for 3 min and slow cooling to 4 °C in buffer A: 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol.

Enzymes. To obtain Dnmt3a-CD, Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with plasmid pET-28a(+) carrying the gene encoding Dnmt3a-CD with an N-terminal 6×His tag. Subsequently, Dnmt3a-CD was isolated and purified using metal-affinity chromatography on Co2+-containing TALON® resin (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Plasmid pET-28a(+) encoding Dnmt3a-CD was provided by Prof. A. Jeltsch (University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany). R.Hin6I and M.SssI were commercial products (SibEnzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia). The purity of the protein samples was evaluated using electrophoresis in a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The protein concentrations per protein monomer were determined using the Bradford assay. The proteins were stored at −80 °C.

DNA methylation. MGMTp CpG island PCR product (MGMT-752;

Table 1) was amplified using 1 µg of genomic DNA from the Raji human lymphoblast-like cell line (Eurogen, Moscow, Russia) as the template, along with NEB Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, MA, USA) and the primers: 5′-GGGATTCTCACTAAGCGGGC and 5′-CTGGCACCTAGAGGTAAGGC. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 5 s, primer annealing at 72°C for 10 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 2 min. The PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and bands corresponding to the 752-bp product were excised and purified using the Cleanup S-Cap DNA Purification Kit (Eurogen, Moscow, Russia) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, 300 ng of the MGMT-752 amplicons were methylated using either Dnmt3a-CD (2 µM) or M.SssI (5 U) in the presence of S-adenosyl-L-methionine (25 µM) for 1 hour at 37°C. The methylated amplicons were purified using the Cleanup S-Cap DNA Purification Kit.

Sequencing Library Preparation and Nanopore Sequencing. Sequencing libraries were prepared using 130 ng of either Dnmt3a-CD/M.SssI-treated, or unmethylated MGMT-752 amplicons following the «Ligation Sequencing Amplicons - Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24) » protocol (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, UK). The sequencing mix was prepared with 30 µl of the barcoded DNA library. The mix was loaded onto a MinION R10.4.1 flow cell and run on an Mk1-B sequencing unit (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, UK). The sequencing run lasted 1 hour and 56 min., yielding 141,000 raw reads and 177 Mb of sequence data in POD5 format. The sequencing run was monitored using MinKNOW software (version 5.7.2). Offline basecalling was performed with the Dorado tool (version 0.6.2) [

51] using supported "sup" models. The reads were mapped to the GRCh38.p14 reference human genome assembly. DNA methylation levels and profiles were analyzed using the Modkit tool (version 0.2.7) and visualized with Prism GraphPad software (version 8.0.1). The modification calling accuracy was defined as a probability that the cytosine is correctly identified as unmethylated. Therefore, an accuracy of 100% represented a 100% average probability among all sequencing reads that the position contained an unmodified cytosine, while an accuracy of 0% meant that there were equal probabilities of cytosine, 5mC and 5hmC present in the analyzed CpG site.

Statistical Analysis. The significance of observed effects was assessed using a two-sided t-test with unequal variances, performed in Prism GraphPad software (version 8.0.1). Methylation efficiencies within or outside the primary PQS region of MGMTp (CpG sites 47–72) were compared between the C-rich and G-rich DNA strands, and two-tailed P values were calculated. Results were reported as mean ± SEM.

CD Measurements. CD spectra of oligonucleotides were recorded in a quartz cuvette of 10 mm optical path length at room temperature in buffer A on a Chirascan CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics Ltd., Surrey, UK) equipped with a thermoelectric controller. The DNA concentration (~2 μM concentration per oligonucleotide strand) was chosen to attain an absorption of 0.6–0.8 at 260 nm, which gives an optimum signal-to-noise ratio. The measurements were performed in the 230–350 nm wavelength range at a scanning speed of 30 nm/min and a signal averaging time of 2 s with a constant flow of dry nitrogen. The CD spectra were normalized to molar circular dichroism (Δε) using molar strand concentration as a reference. Spectra were baseline-corrected for signal contributions caused by the buffer and processed with Graph Pad Prism 8.0.1 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Inhibition of DNA methylation by G4-forming oligonucleotides. MGMT-ds1-f (300 nM) was methylated by 2 μM Dnmt3a-CD in the presence of various concentrations of MGMT-G4, MGMT G4-mut or non-specific control oligonucleotide for 1.5 h at 37 °C in buffer A containing AdoMet (25 μM). Methylation efficiency was analyzed by the protection of methylated DNA from cleavage by R.Hin6I (G↓CGC). After digestion with R.Hin6I, the mixtures were analyzed on 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea, with the determination of the extent of methylation as described in [

19]. The gels were visualized using a Typhoon FLA 9500 scanner (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, UK), and the fluorescence intensities of intact DNA and cleavage products were determined. The methylation efficiency was calculated using GelQuantNET version 1.7.8. using the equation:

where

w0 is the extent of DNA cleavage before methylation,

wDnmt3a is the extent of DNA cleavage after methylation by Dnmt3a-CD. IC

50 values were calculated via fitting the dependence of the extent of methylation on the concentration of an oligonucleotide using Graph Pad Prism 8.0.1 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Bio-layer interferometry. DNA duplexes or oligonucleotides (690 nM) were used for the experiment. The binding buffer contained 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 100 µM AdoHcy, 5% glycerol, 0.02% Tween-20, and 0.5 mg/mL BSA. Bio-layer interferometry (BLI) analyses were performed using the BLItz instrument (ForteBio, Fremont, CA, USA) in extended kinetics mode with stirring at 2200 rpm in triplicate. Streptavidin biosensors (ForteBio, Fremont, CA, USA) were hydrated in the binding buffer for 10 min. prior to measurements. The optimized BLI protocol included the following steps: (i) incubation for 30 s; (ii) biotinylated DNA substrate immobilization for 120 s; (iii) sensor wash for 30 s; (iv) DNA binding to Dnmt3a-CD (690 nM in binding buffer) for 300 s; (v) dissociation of the DNA-protein complex in binding buffer for 120 seconds. All measurements were conducted in black microtubes (Sigma-Aldrich, New York, NY, USA) using a minimum of 300 µL of the appropriate solution. The resulting binding curves were fitted to a 1:1 DNA:protein binding model using an exponential approximation using Graph Pad Prism 8.0.1 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated that PQS within the MGMT promoter influence the activity of MTase Dnmt3a, a key enzyme responsible for de novo methylation and establishing the MGMT promoter’s methylation pattern. Our findings underscore the role of PQS in regulating MGMT promoter methylation and highlight the technical challenges posed by guanine-rich sequences in nanopore sequencing. Specifically, the presence of PQS in the sequenced region impacts basecalling accuracy in nanopore data, emphasizing the need to account for such structures during analysis. Moreover, MGMTp CpG island G4 structures are recognized by Dnmt3a-CD and compete with the DNA duplex substrate, thereby modulating the methylation efficiency at nearby CpG sites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Figure S1: Methylation efficiencies of MGMT-752 by Dnmt3a-CD calculated from nanopore sequencing data. Figure S2: Inhibition of methylation of a DNA duplex MGMT-ds1-f by MGMT-G4 oligonucleotide; Figure S3: Binding of MGMT-G4 to Dnmt3a-CD studied by biolayer interferometry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Zvereva; Funding acquisition, Galina Pavlova and Maria Zvereva; Investigation, Alexander Sergeev, Daniil Malyshev and Adelya Genatullina; Project administration, Maria Zvereva; Resources, Maria Zvereva; Supervision, Alexander Sergeev, Elizaveta Gromova and Maria Zvereva; Visualization, Alexander Sergeev; Writing – original draft, Alexander Sergeev; Writing – review & editing, Elizaveta Gromova and Maria Zvereva. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation under agreement No. 075-15-2021-1343.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, Z.D.; Meissner, A. DNA Methylation: Roles in Mammalian Development. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14, 204–220. [CrossRef]

- Bird, A. DNA Methylation de Novo. Science (1979) 1999, 286, 2287–2288. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.D.; Hetzel, S.; Meissner, A. DNA Methylation in Mammalian Development and Disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2024 2024, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.M.; Bird, A. CpG Islands and the Regulation of Transcription. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 1010–1022. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A. Functions of DNA Methylation: Islands, Start Sites, Gene Bodies and Beyond. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 484–492. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Kondo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ahmed, S.; Shu, J.; Chen, X.; Waterland, R.A.; Issa, J.-P.J. Genome-Wide Profiling of DNA Methylation Reveals a Class of Normally Methylated CpG Island Promoters. PLoS Genet 2007, 3, e181. [CrossRef]

- Jeltsch, A.; Jurkowska, R.Z. New Concepts in DNA Methylation. Trends Biochem Sci 2014, 39, 310–318. [CrossRef]

- Jurkowska, R.Z.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. Structure and Function of Mammalian DNA Methyltransferases. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 206–222. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-H.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.E.; Liang, G.; Zhao, G.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K.; Jones, P.A. Structure of Nucleosome-Bound DNA Methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B. Nature 2020, 586, 151–155. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Tsujimoto, N.; Li, E. The PWWP Domain of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b Is Required for Directing DNA Methylation to the Major Satellite Repeats at Pericentric Heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 9048–9058. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Ding, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yin, X.; He, S.; Shi, P.; Dong, L.; Li, G.; et al. Structural Insight into Autoinhibition and Histone H3-Induced Activation of DNMT3A. Nature 2014 517:7536 2014, 517, 640–644. [CrossRef]

- Dukatz, M.; Holzer, K.; Choudalakis, M.; Emperle, M.; Lungu, C.; Bashtrykov, P.; Jeltsch, A. H3K36me2/3 Binding and DNA Binding of the DNA Methyltransferase DNMT3A PWWP Domain Both Contribute to Its Chromatin Interaction. J Mol Biol 2019, 431, 5063–5074. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, N.; Uehara, R.; Uemura, S.; Ohishi, H.; Shirane, K.; Sasaki, H. Combined and Differential Roles of ADD Domains of DNMT3A and DNMT3L on DNA Methylation Landscapes in Mouse Germ Cells. Nature Communications 2024 15:1 2024, 15, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wapenaar, H.; Clifford, G.; Rolls, W.; Pasquier, M.; Burdett, H.; Zhang, Y.; Deák, G.; Zou, J.; Spanos, C.; Taylor, M.R.D.; et al. The N-Terminal Region of DNMT3A Engages the Nucleosome Surface to Aid Chromatin Recruitment. EMBO Rep 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of Chromatin by Histone Modifications. Cell Res 2011, 21, 381–395. [CrossRef]

- Cree, S.L.; Fredericks, R.; Miller, A.; Pearce, F.G.; Filichev, V.; Fee, C.; Kennedy, M.A. DNA G-Quadruplexes Show Strong Interaction with DNA Methyltransferases in Vitro. FEBS Lett 2016, 590, 2870–2883. [CrossRef]

- Rauchhaus, J.; Robinson, J.; Monti, L.; Di Antonio, M. G-Quadruplexes Mark Sites of Methylation Instability Associated with Ageing and Cancer. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 1665. [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.-Q.; Ghanbarian, A.T.; Spiegel, J.; Martínez Cuesta, S.; Beraldi, D.; Di Antonio, M.; Marsico, G.; Hänsel-Hertsch, R.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. DNA G-Quadruplex Structures Mold the DNA Methylome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 951–957. [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, A. V; Loiko, A.G.; Genatullina, A.I.; Petrov, A.S.; Kubareva, E.A.; Dolinnaya, N.G.; Gromova, E.S. Crosstalk between G-Quadruplexes and Dnmt3a-Mediated Methylation of the c-MYC Oncogene Promoter. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 45. [CrossRef]

- Halder, R.; Halder, K.; Sharma, P.; Garg, G.; Sengupta, S.; Chowdhury, S. Guanine Quadruplex DNA Structure Restricts Methylation of CpG Dinucleotides Genome-Wide. Mol Biosyst 2010, 6, 2439–2447. [CrossRef]

- Jara-Espejo, M.; Line, S.R. DNA G-quadruplex Stability, Position and Chromatin Accessibility Are Associated with CpG Island Methylation. FEBS J 2020, 287, 483–495. [CrossRef]

- Varizhuk, A.; Isaakova, E.; Pozmogova, G. DNA G-Quadruplexes (G4s) Modulate Epigenetic (Re)Programming and Chromatin Remodeling. BioEssays 2019, 41, 1900091. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Hurley, L.H. Structures, Folding Patterns, and Functions of Intramolecular DNA G-Quadruplexes Found in Eukaryotic Promoter Regions. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1149–1171. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.H.; Liew, C.W.; Heddi, B.; Phan, A.T. Structural Basis for Parallel G-Quadruplex Recognition by an Ankyrin Protein. J Am Chem Soc 2024, 146, 13709–13713. [CrossRef]

- Dukatz, M.; Dittrich, M.; Stahl, E.; Adam, S.; de Mendoza, A.; Bashtrykov, P.; Jeltsch, A. DNA Methyltransferase DNMT3A Forms Interaction Networks with the CpG Site and Flanking Sequence Elements for Efficient Methylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298, 102462. [CrossRef]

- Rajavelu, A.; Jurkowska, R.Z.; Fritz, J.; Jeltsch, A. Function and Disruption of DNA Methyltransferase 3a Cooperative DNA Binding and Nucleoprotein Filament Formation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 569–580. [CrossRef]

- Kulis, M.; Esteller, M. DNA Methylation and Cancer. Adv Genet 2010, 70, 27–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Wu, C.; Cui, W.; Wang, L. DNA Methyltransferases in Cancer: Biology, Paradox, Aberrations, and Targeted Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2123. [CrossRef]

- Berdasco, M.; Esteller, M. Aberrant Epigenetic Landscape in Cancer: How Cellular Identity Goes Awry. Dev Cell 2010, 19, 698–711. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.M.; Zhu, J.; Ding, Y.; Visser, J.A.; Zhu, J.; Burrows, C.J. Human DNA Repair Genes Possess Potential G-Quadruplex Sequences in Their Promoters and 5′-Untranslated Regions. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 991–1002. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Q.; Shao, A. O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT): Challenges and New Opportunities in Glioma Chemotherapy. Front Oncol 2020, 9, 1547. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Simeone, A.; Melidis, L.; Cuesta, S.M.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. An Upstream G-Quadruplex DNA Structure Can Stimulate Gene Transcription. ACS Chem Biol 2024, 19, 736–742. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, J.; Ji, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, J. Unraveling the Mysteries of MGMT: Implications for Neuroendocrine Tumors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2024, 1879, 189184. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xin, S.; Gao, M.; Cai, Y. Promoter Hypermethylation of MGMT Gene May Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Gastric Cancer. Medicine 2017, 96, e6708. [CrossRef]

- Inno, A. Role of MGMT as Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer. World J Clin Cases 2014, 2, 835. [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Shi, Y.; Ye, P.; Pan, Z.; Long, X. Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2017, 42, 2430–2440. [CrossRef]

- Kordi-Tamandani, D.M.; Moazeni-Roodi, A.-K.; Rigi-Ladiz, M.-A.; Hashemi, M.; Birjandian, E.; Torkamanzehi, A. Promoter Hypermethylation and Expression Profile of MGMT and CDH1 Genes in Oral Cavity Cancer. Arch Oral Biol 2010, 55, 809–814. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Luo, J.-Y.; Tan, H.-Z. Associations of MGMT Promoter Hypermethylation with Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion and Cervical Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0222772. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qu, W.; Tu, J.; Qi, H. Implications of Advances in Studies of O6-Methylguanine-DNA- Methyltransferase for Tumor Prognosis and Treatment. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2023, 28, 197. [CrossRef]

- Della Monica, R.; Cuomo, M.; Buonaiuto, M.; Costabile, D.; Franca, R.A.; Del Basso De Caro, M.; Catapano, G.; Chiariotti, L.; Visconti, R. MGMT and Whole-Genome DNA Methylation Impacts on Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapy of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 7148. [CrossRef]

- Gowher, H.; Jeltsch, A. Molecular Enzymology of the Catalytic Domains of the Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b DNA Methyltransferases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 20409–20414. [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Yang, L.; Yu, L.; Yuan, J.; Hu, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Pang, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, J.; et al. Epigenetic Silencing of O6 -Methylguanine DNA Methyltransferase Gene in NiS-Transformed Cells. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1267–1275. [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, C.; Nicolas, J. Sequencing DNA with Nanopores: Troubles and Biases. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0257521. [CrossRef]

- Kejnovská, I.; Renčiuk, D.; Palacký, J.; Vorlíčková, M. CD Study of the G-Quadruplex Conformation. In Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.); Humana Press Inc., 2019; Vol. 2035, pp. 25–44.

- Mallona, I.; Ilie, I.M.; Karemaker, I.D.; Butz, S.; Manzo, M.; Caflisch, A.; Baubec, T. Flanking Sequence Preference Modulates de Novo DNA Methylation in the Mouse Genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, M.; Czapinska, H.; Bochtler, M. CpG Underrepresentation and the Bacterial CpG-Specific DNA Methyltransferase M.MpeI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 105–110. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Lu, R.; Wang, P.; Yu, Y.; Chen, D.; Gao, L.; Liu, S.; Ji, D.; Rothbart, S.B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Structural Basis for DNMT3A-Mediated de Novo DNA Methylation. Nature 2018, 554, 387–391. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Lin, B.; Sibenaller, Z.; Ryken, T.; Lee, H.; Yoon, J.-G.; Rostad, S.; Foltz, G. Comprehensive Analysis of MGMT Promoter Methylation: Correlation with MGMT Expression and Clinical Response in GBM. PLoS One 2011, 6, e16146. [CrossRef]

- OneStep QMethylTM Kit Available online: https://epigenie.com/products/onestep-qmethyl-kit/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- OneStep PLUS QMethylTM PCR Kit Available online: https://files.zymoresearch.com/protocols/_d5312_onestep_plus_q_methyl_pcr_kit.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Dorado - Oxford Nanopore’s Basecaller Available online: https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado (accessed on 28 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).