Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

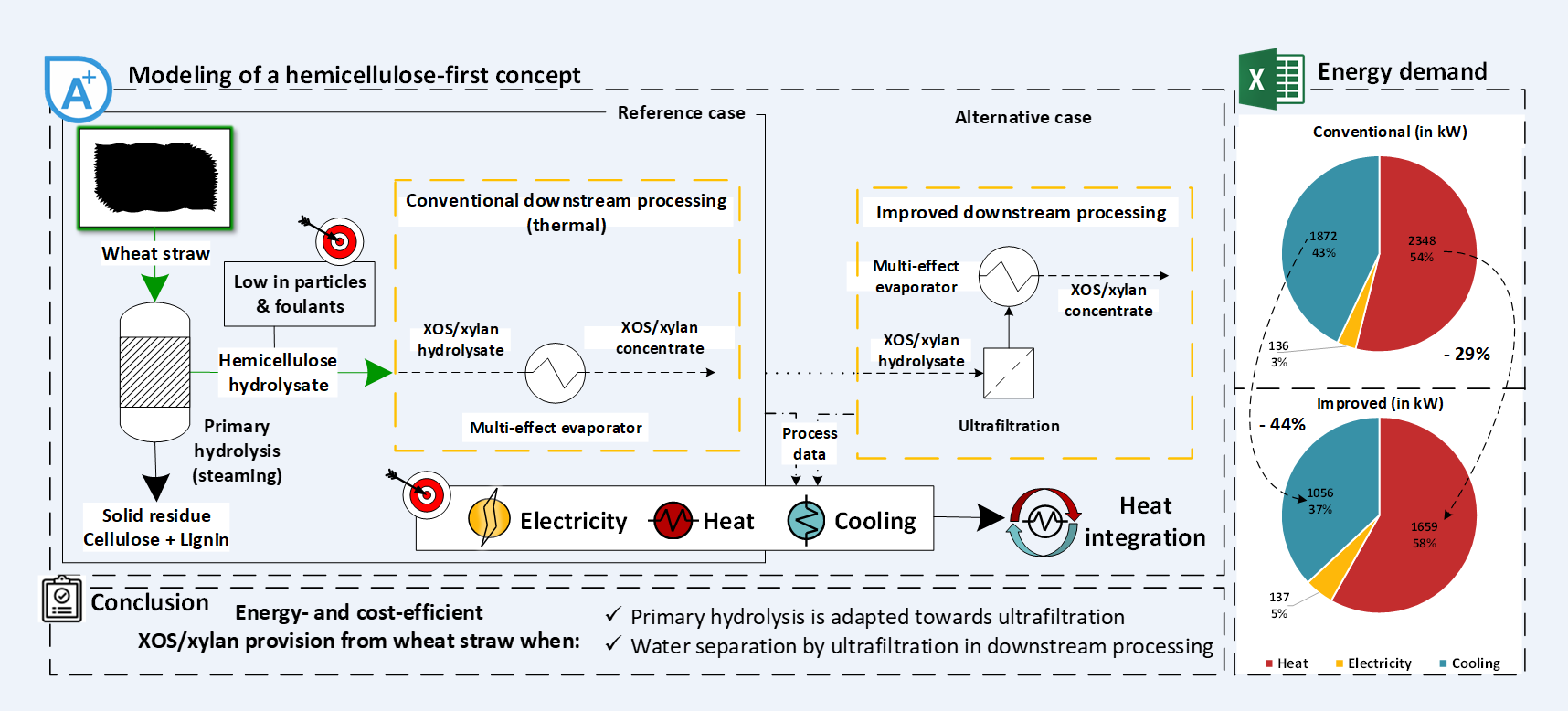

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

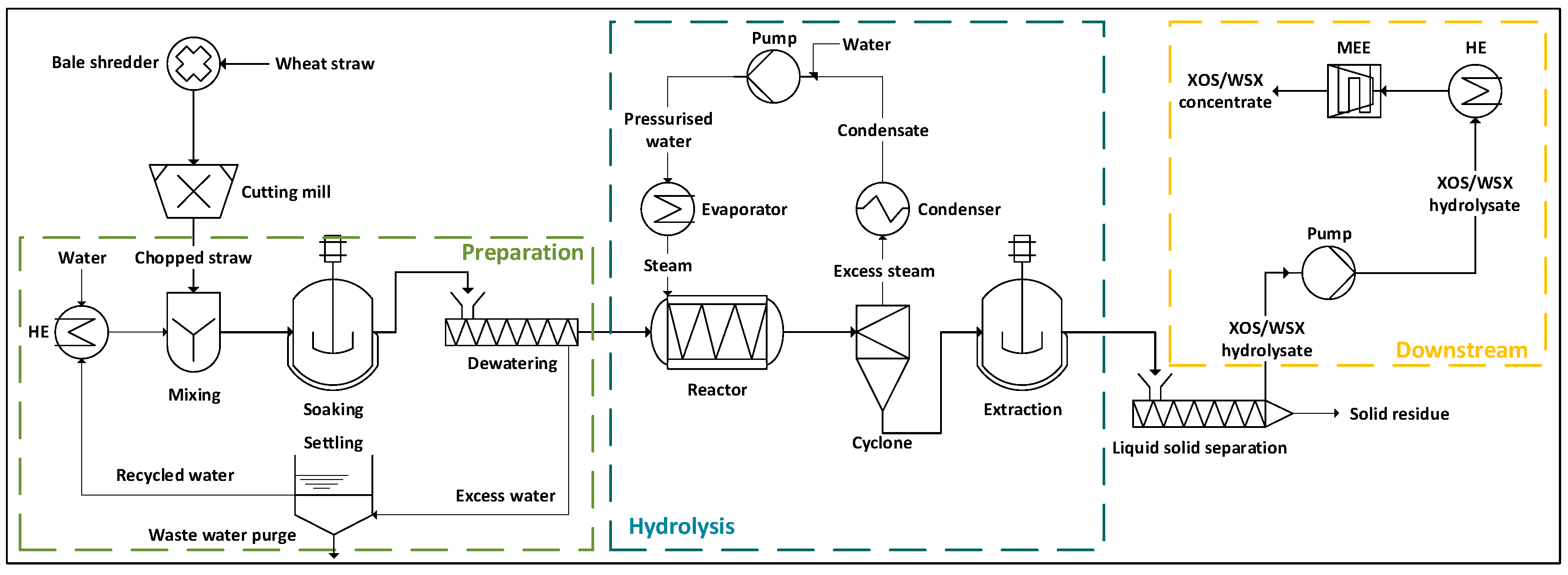

2. Process Analysis (Reference Case)

2.1. Process Modeling

2.1.1. Process Definition

| Fraction | DM | oDM | Glucan | Arabino-xylan | Lignin | Acetate | Ash | Protein | Rest |

| Unit | wt%FM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM | wt%DM |

| Hydrolysate | 4.5 | 93.0 | 5.5 | 57.9 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 13.3 |

| STD | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Component | CB | Glucose | Xylose | Arabinose | Formic Acid | Acetic Acid | HMF c | Furfural | Ara/Xyl |

| Unit | g/L | g/L | g/L | g/L | g/L | g/L | g/L | g/L | |

| Measured total concentrationsb | |||||||||

| Hydrolysate | 0.82 | 1.75 | 26.11 | 2.06 | 0.80 | 3.28 | 0.11 | 0.92 | 7.9% |

| STD | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07% |

| Released from oligomers | |||||||||

| Hydrolysate | 0.82 | 1.67 | 22.75 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 2.7% |

| STD | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06% |

| Sol (%) a | -- | 95 | 87 | 30 | 0 | 26 | 8 | 46 | -- |

2.1.2. Flowsheet Simulation

2.2. Results and Discussion

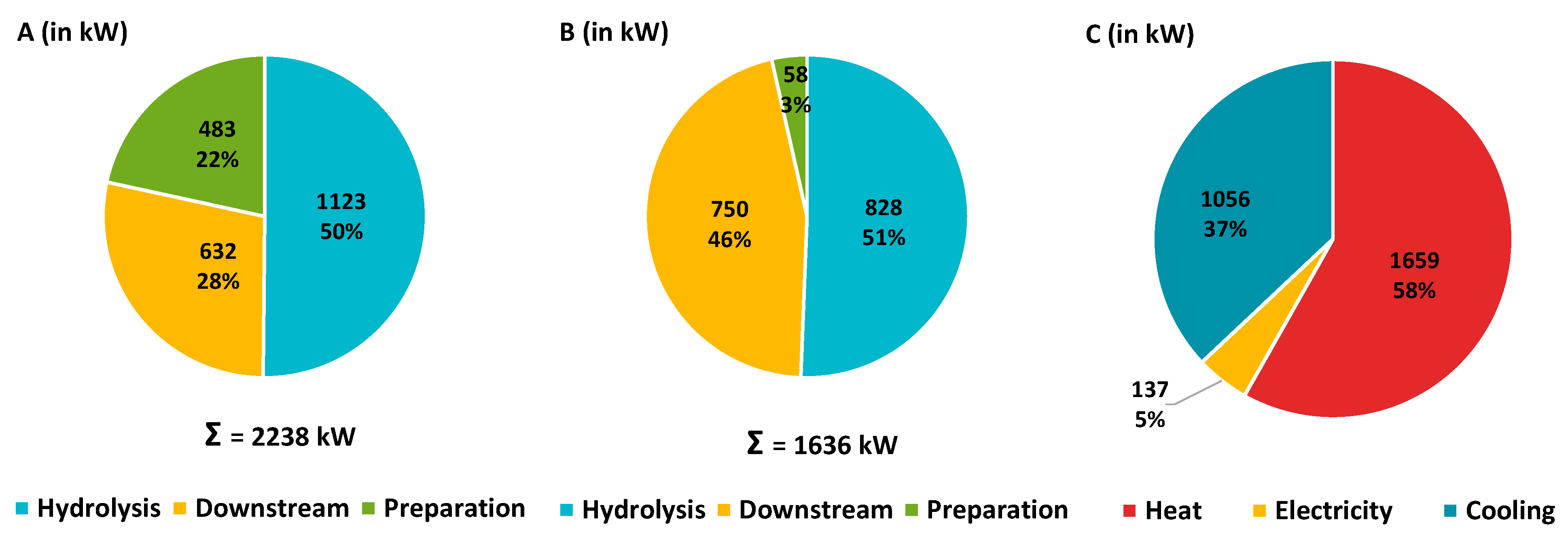

| Unit | Conventional process a | |

|

Heating Preparation Hydrolysis Downstream |

MWh/a MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) |

17,610 0 (0) 8453 (48) 9157 (52) |

| High Pressure steam Low Pressure steam |

MWh/a (%) t/a MWh/a (%) t/a |

8,075 (46) 17,070 9,538 (54) 15,630 |

|

Cooling Preparation Hydrolysis Downstream |

MWh/a MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) |

14,040 0,421 (3) 1,123 (8) 12,496 (89) |

| Electricity | MWh/a | 1,020 |

|

XOS/WSX concentrate Dry mass (DM) XOS/WSX content |

t/a wt% %DM |

10,172 50 61 |

|

Solid residue Dry mass (DM) Cellulose Lignin |

t/a wt% %DM%DM |

47,733 50 46 34 |

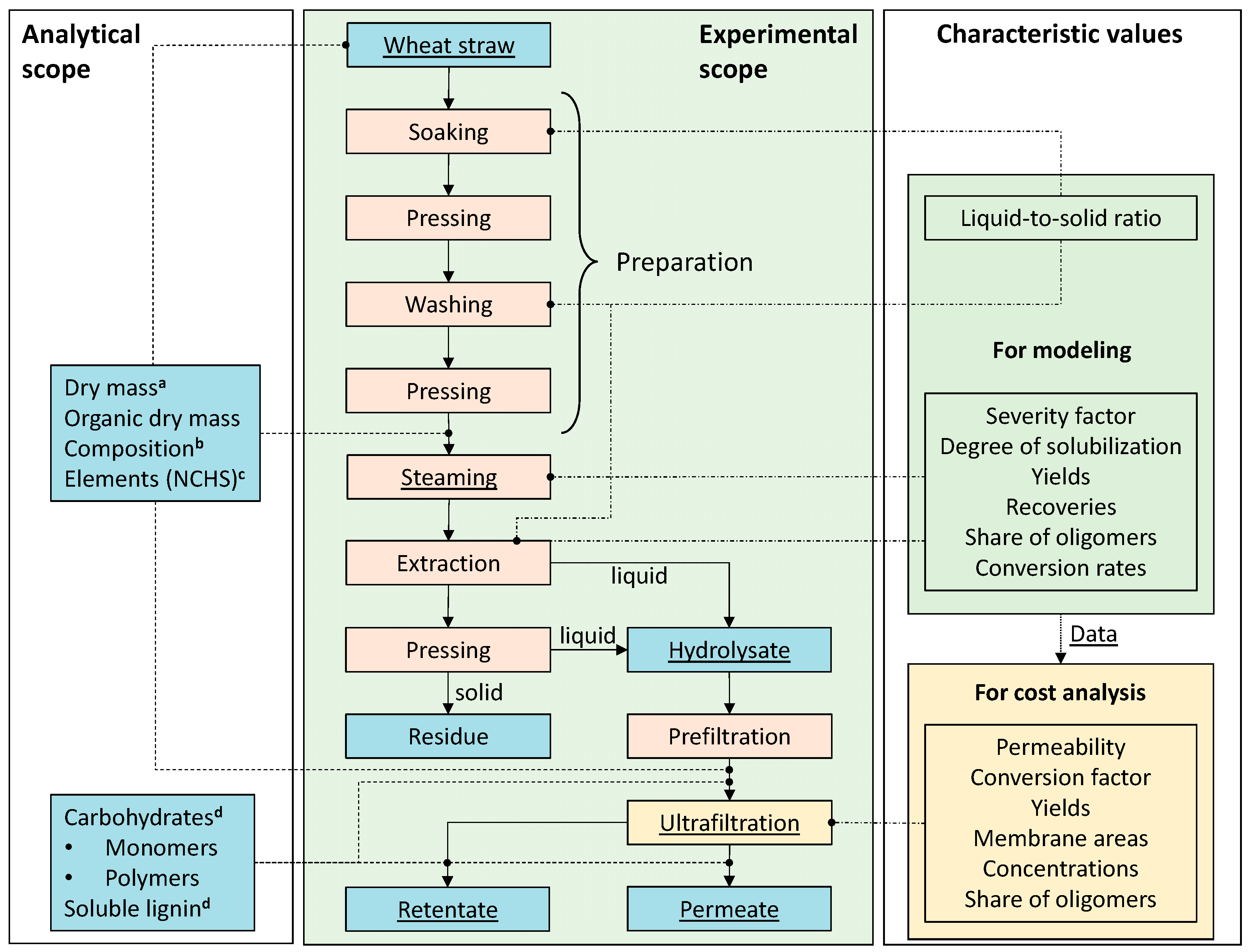

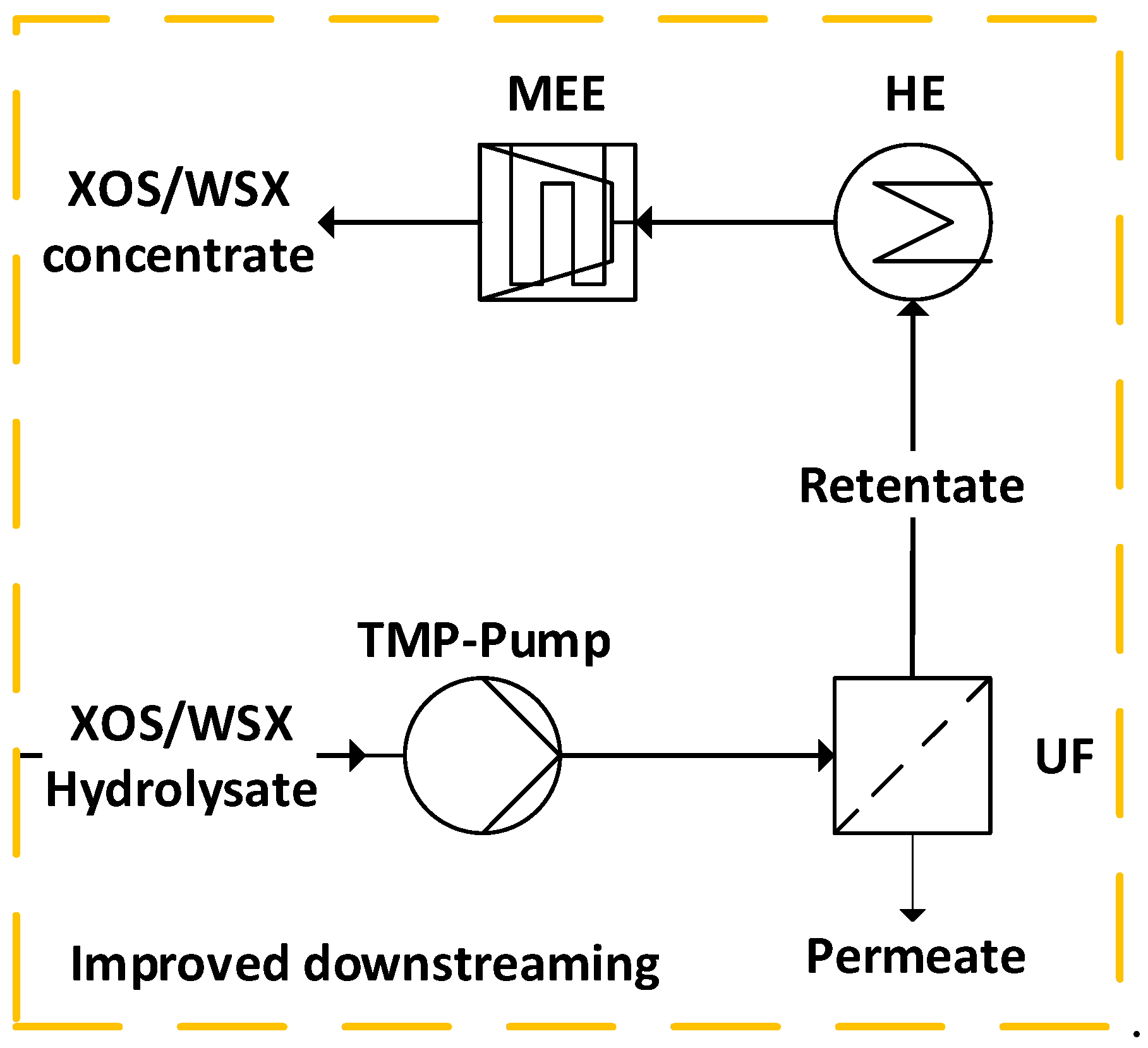

3. Process Improvement (Alternative Case)

3.1. Experimental Procedure

| Membrane type | MWCO a kDa |

Material b | Supplier | pH |

T °C |

p bar |

Permeabilityc L/(m2 h bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UH050 | 50 | Hydrophilic PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 85 | |

| UH030 | 30 | Hydrophilic PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 35 | |

| UP020 | 20 | PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 70 | |

| UP010 | 10 | PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 50 | |

| UP005 | 5 | PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 10 | |

| UH004P | 4 | Hydrophilic PES | Microdyn Nadir | 0-14 | 5-95 | ≥ 7.0 | |

| UF10 | 10 | PES | Microdyn Nadir | 2-11 | 5-45 | 1-21 | ≥ 74 |

| UF5 | 5 | PES | Microdyn Nadir | 2-11 | 5-45 | 1-21 | ≥ 8.3 |

| PS (GR61PP) | 20 | PS | Alfa Laval | 1-13 | 5-75 | 1-10 | |

| PES (GR80PP) | 10 | PES | Alfa Laval | 1-13 | 5-75 | 1-10 | |

| PES (GR90PP) | 5 | PES | Alfa Laval | 1-13 | 5-75 | 1-10 |

3.2. Process Modeling

3.2.1. Process Definition

3.2.1. Flowsheet Simulation

3.3. Cost Analysis

3.4. Results and Discussion

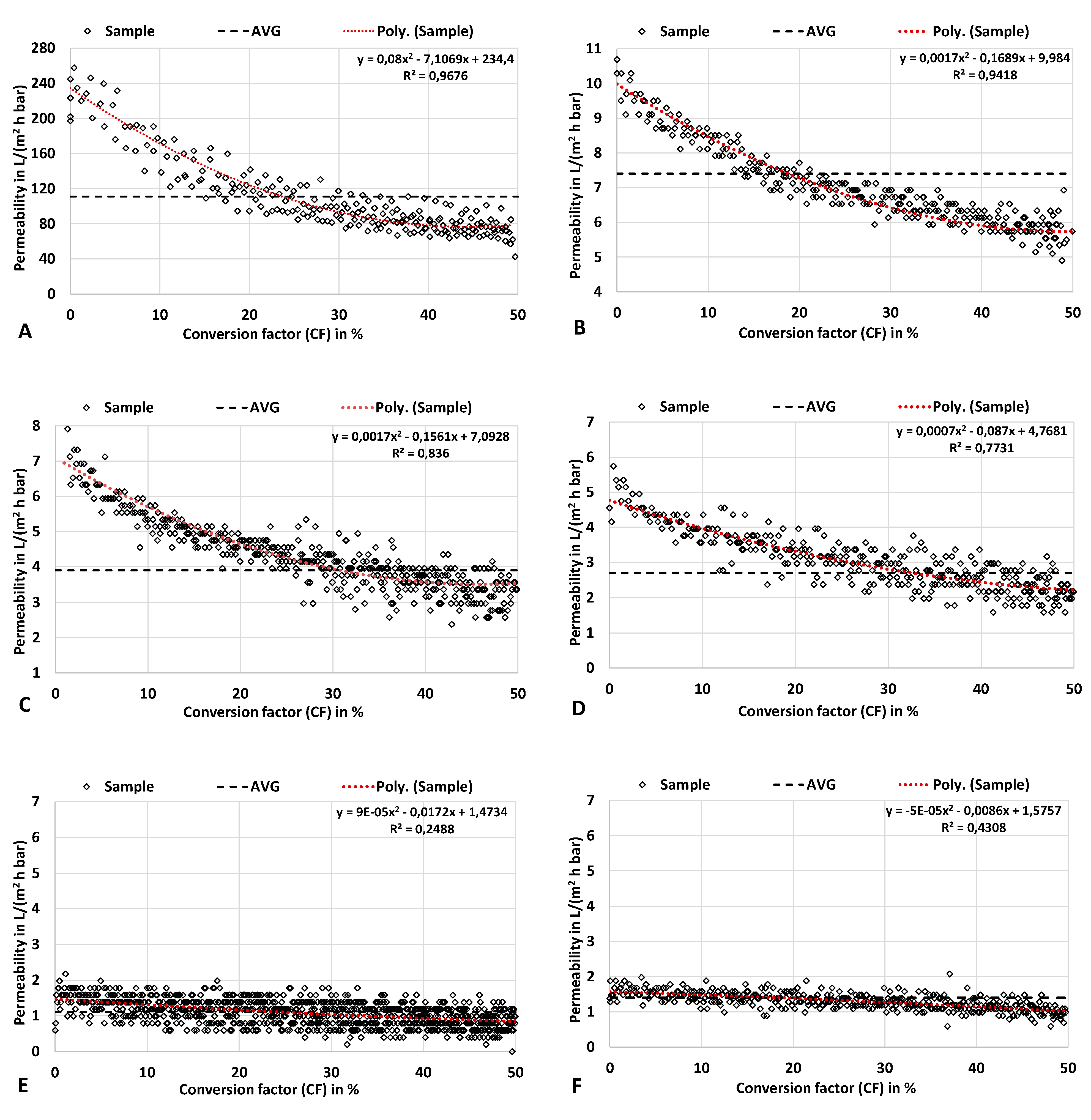

3.4.1. Experimental Data

3.4.2. Process Data

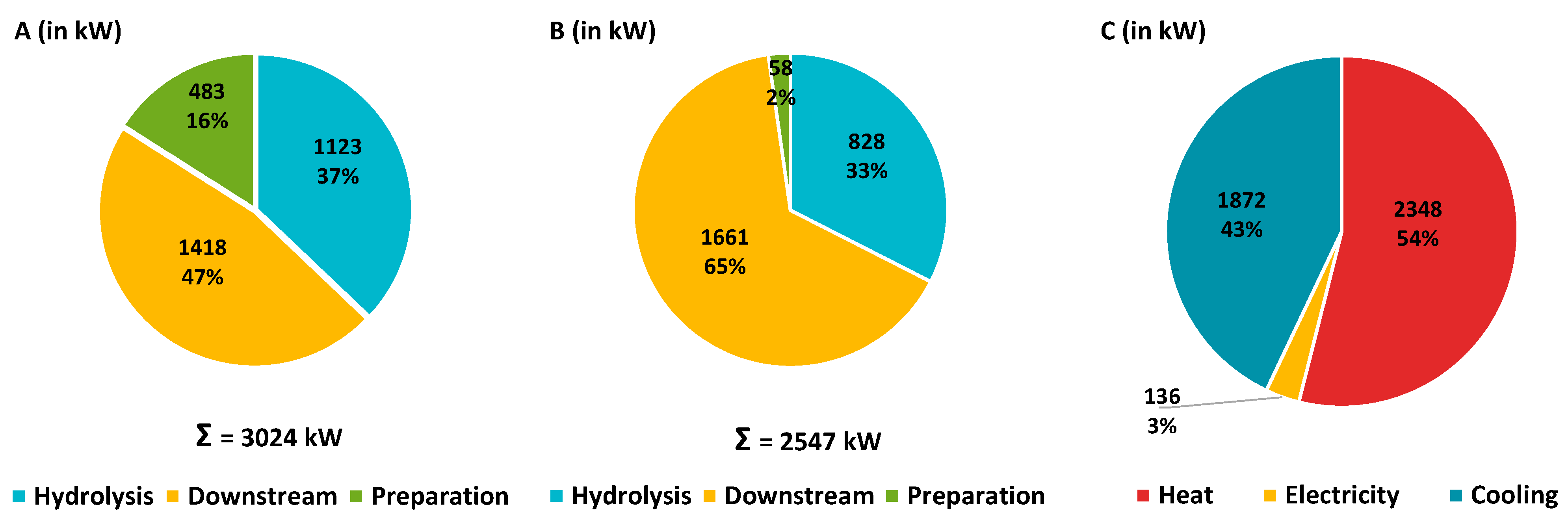

| Unit | Improved process | Change to reference case b | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Heating Preparation Hydrolysis Downstream |

MWh/a MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) |

12,443 0 (0) 8,461 (68) 3,982 (32) |

-29.3 % (+41.7 %) (-38.5 %) |

| High Pressure steam Low Pressure steam |

MWh/a (%) t/a MWh/a (%) t/a |

8,075 (65) 17,070 4,369 (35) 7,163 |

0 % 0 % -54.2 % -54.2 % |

|

Cooling Preparation Hydrolysis Downstream |

MWh/a MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) MWh/a (%) |

7,920 0, 396 (5) 1,901 (24) 5,623 (71) |

-43.6 % (+66.7 %) (+200.0 %) (-20.2 %) |

| Electricity | MWh/a | 1,028 | +0.9 % |

|

XOS/WSX concentrate Dry mass (DM) XOS/WSX content |

t/a wt% %DM |

7,698 a50 71 a |

-24.3 % 0 % +16.4 % |

|

Solid residue Dry mass (DM) Cellulose Lignin |

t/a wt% %DM%DM |

47,733 50 46 34 |

0 % 0 % 0 % 0 % |

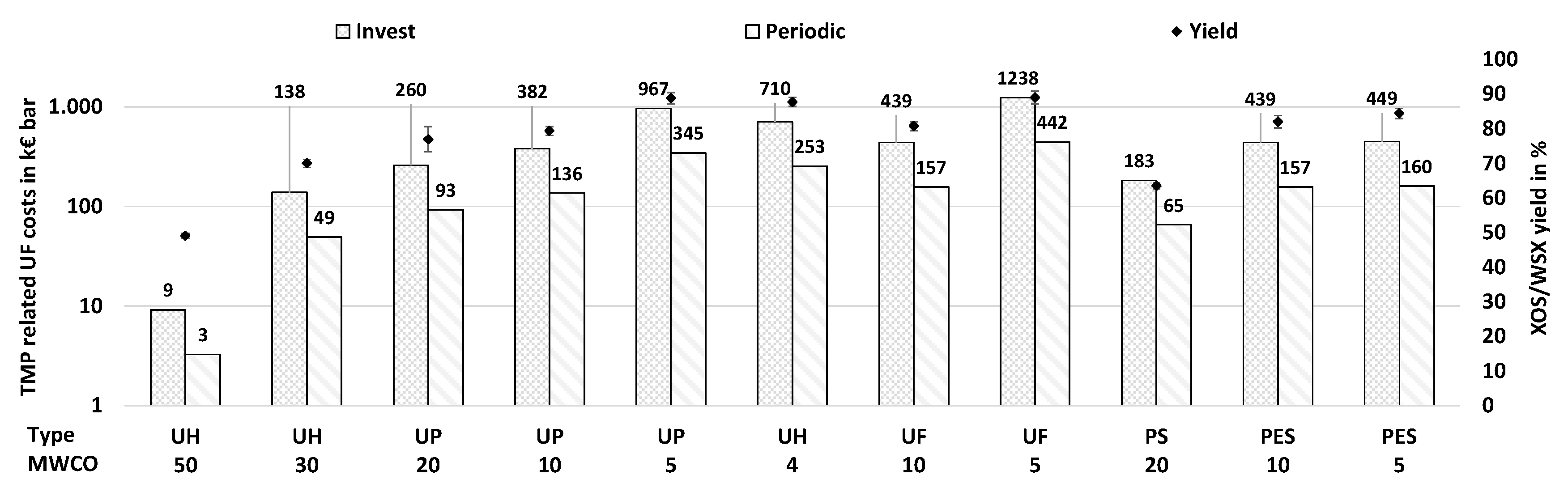

3.4.3. Cost Analysis

| Type b MWCO |

Unit | UH 50 |

UH 30 |

UP 20 |

UP 10 |

UP 5 |

UH 4 |

UF 10 |

UF 5 |

PS 20 |

PES 10 |

PES 5 |

| l/(m2 h bar) | 111 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

| c | m2 bar | 66 | 986 | 1854 | 2725 | 6904 | 5069 | 3138 | 8840 | 1306 | 3138 | 3208 |

| g/L | 48 | 68 | 75 | 77 | 87 | 85 | 79 | 87 | 62 | 80 | 82 | |

| g/L | 44 | 30 | 25 | 21 | 9 | 13 | 17 | 9 | 33 | 16 | 16 |

4. Overall Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, N.; Singhania, R.R.; Nigam, P.S.; Dong, C.-D.; Patel, A.K.; Puri, M. Global status of lignocellulosic biorefinery: Challenges and perspectives. Bioresource Technology 2022, 344, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuling, U.; Kaltschmitt, M. Review of biofuel production – feedstock, processes and markets. Journal of Oil Palm Research 2017, 29, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchspies, B.; Kaltschmitt, M. Life cycle assessment of bioethanol from wheat and sugar beet discussing environmental impacts of multiple concepts of co-product processing in the context of the European Renewable Energy Directive. Biofuels 2016, 7, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.F.; Parsin, S.; Lüdtke, O.; Kaltschmitt, M. Biogas production from straw—the challenge feedstock pretreatment. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2020, 12, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro, F.; Duarte, L.C.; Gírio, F.M. Hemicellulose biorefineries: a review on biomass pretreatments. Journal of Scientific & Industrial Research 2008, 849–864. [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann, T.; Kravanja, P.; Friedl, A. Simulation of the downstream processing in the ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass with ASPEN Plus® and IPSEpro. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Pan, X.J. Woody biomass pretreatment for cellulosic ethanol production: Technology and energy consumption evaluation. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, 4992–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, W.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Show, P.L. Tg. Ibrahim, Tg. Nilam Baizura; Chew, K.W.; Culaba, A.; Chang, J.-S. Pretreatment methods for lignocellulosic biofuels production: current advances, challenges and future prospects. Biofuel Research Journal 2020, 7, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Awasthi, A.K.; Lukk, T.; Tuohy, M.G.; Gong, L.; Nguyen-Tri, P.; Goddard, A.D.; Bill, R.M.; Nayak, S.; et al. Lignocellulosic biorefineries: The current state of challenges and strategies for efficient commercialization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 148, 111258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankar, A.R.; Pandey, A.; Modak, A.; Pant, K.K. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresource Technology 2021, 334, 125235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, A.W.; Qureshi, K.; Harijan, K.; Abro, R.; Abbas, T.; Bazmi, A.A.; Karim, S.; Yu, G. Insight into progress in pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Energy 2017, 122, 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Purkait, M.K. A review on the environment-friendly emerging techniques for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: Mechanistic insight and advancements. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Conrad, M.; Sun, S.-N.; Sanchez, A.; Rocha, G.J.M.; Romaní, A.; Castro, E.; Torres, A.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Andrade, L.P.; et al. Engineering aspects of hydrothermal pretreatment: From batch to continuous operation, scale-up and pilot reactor under biorefinery concept. Bioresource Technology 2020, 299, 122685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Larnaudie, V.; Veersma, R.J.; van Erven, G.; Shiva, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ríos-González, L.J.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rosero-Chasoy, G.; Ferrari, M.D.; et al. Advances in process design, techno-economic assessment and environmental aspects for hydrothermal pretreatment in the fractionation of biomass under biorefinery concept. Bioresource Technology 2023, 369, 128469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, G.P.; Mansell, R.V. A comparative thermodynamic evaluation of bioethanol processing from wheat straw. Applied Energy 2018, 224, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font Palma, C. Modelling of tar formation and evolution for biomass gasification: A review. Applied Energy 2013, 111, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, M.; Kaltschmitt, M. Thermal pre-treatment options to enhance anaerobic digestibility – A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 137, 110627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, M.M.; Barta, K.; Beckham, G.T.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Ralph, J.; Rinaldi, R.; Román-Leshkov, Y.; Samec, J.S.M.; Sels, B.F.; Wang, F. Guidelines for performing lignin-first biorefining. Energy & Environmental Science 2021, 14, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, W.; van Aelst, K.; Cooreman, E.; van Aelst, J.; van den Bosch, S.; Sels, B.F. Stepping away from purified solvents in reductive catalytic fractionation: a step forward towards a disruptive wood biorefinery process. Energy & Environmental Science 2023, 16, 2518–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, L.; Henríquez, C.; Corro-Tejeda, R.; Bernal, S.; Armijo, B.; Salazar, O. Xylooligosaccharides from lignocellulosic biomass: A comprehensive review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 251, 117118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro, F. Production of oligosaccharides by autohydrolysis of brewery's spent grain. Bioresource Technology 2004, 91, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, D.S.; Hlangothi, S.P.; John, M.J. Bio-based products from xylan: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 179, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, M.F.; Shaheen, H.; Wu, A.-M. Cell wall hemicellulose for sustainable industrial utilization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 144, 110996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Hu, Y.; Tian, R.; Bian, J.; Peng, F. Hydrothermal pretreatment for the production of oligosaccharides: A review. Bioresource Technology 2022, 343, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, C.; Silvério, S.C.; Prather, K.L.J.; Rodrigues, L.R. From lignocellulosic residues to market: Production and commercial potential of xylooligosaccharides. Biotechnology Advances 2019, 37, 107397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.G.; Teixeira, J.A.; Domingues, L. Economic determinants on the implementation of a Eucalyptus wood biorefinery producing biofuels, energy and high added-value compounds. Applied Energy 2021, 303, 117662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsin, S.; Kaltschmitt, M. Processing of hemicellulose in wheat straw by steaming and ultrafiltration - A novel approach. Bioresource Technology 2023, 393, 130071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scapini, T.; Dos Santos, M.S.N.; Bonatto, C.; Wancura, J.H.C.; Mulinari, J.; Camargo, A.F.; Klanovicz, N.; Zabot, G.L.; Tres, M.V.; Fongaro, G.; et al. Hydrothermal pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for hemicellulose recovery. Bioresource Technology 2021, 342, 126033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, R.; Etzold, H.; Verges, M.; Gröngröft, A.; Kraume, M. Demonstration and Assessment of Purification Cascades for the Separation and Valorization of Hemicellulose from Organosolv Beechwood Hydrolyzates. Membranes (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valério, R.; Crespo, J.G.; Galinha, C.F.; Brazinha, C. Effect of Ultrafiltration Operating Conditions for Separation of Ferulic Acid from Arabinoxylans in Corn Fibre Alkaline Extract. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.S.; Timmerhaus, K.D.; West, R.E. Plant design and economics for chemical engineers, 5. ed., internat. ed., [Nachdr.]; McGraw-Hill: Boston, 2006; ISBN 0071198725. [Google Scholar]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Tabil, L.G.; Song, Y.; Iroba, K.L.; Meda, V. Grinding energy and physical properties of chopped and hammer-milled barley, wheat, oat, and canola straws. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 60, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Tabil, L.G.; Sokhansanj, S. Grinding performance and physical properties of wheat and barley straws, corn stover and switchgrass. Biomass and Bioenergy 2004, 27, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratky, L.; Jirout, T. Biomass Size Reduction Machines for Enhancing Biogas Production. Chemical Engineering & Technology 2011, 34, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Smirnova, I. Counter-Current Suspension Extraction Process of Lignocellulose in Biorefineries to Reach Low Water Consumption, High Extraction Yields, and Extract Concentrations. Processes 2021, 9, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renon, H.; Prausnitz, J.M. Local compositions in thermodynamic excess functions for liquid mixtures. AIChE Journal 1968, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DDBST GmbH. Dortmund Data Bank (DDB). Available online: https://www.ddbst.com/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Humbird, D.; Davis, R.; Tao, L.; Kinchin, C.; Hsu, D.; Aden, A.; Schoen, P.; Lukas, J.; Olthof, B.; Worley, M.; et al. Process Design and Economics for Biochemical Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Ethanol: Dilute-Acid Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Corn Stover 2011. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Ruzene, D.S.; Silva, D.P.; Da Silva, F.F.M.; Vicente, A.A.; Teixeira, J.A. Development and characterization of an environmentally friendly process sequence (autohydrolysis and organosolv) for wheat straw delignification. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2011, 164, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, K.; Spetz, P.; Pranovich, A.; Hartonen, K.; Kitunen, V.; Ilvesniemi, H. Pressurized hot water extraction of Norway spruce hemicelluloses using a flow-through system. Wood Sci Technol 2011, 45, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawther, J.M.; Sun, R.; Banks, W.B. Extraction, fractionation, and characterization of structural polysaccharides from wheat straw. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1995, 43, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, K.; Wopienka, E.; Pfeifer, C.; Schwarz, M.; Sedlmayer, I.; Haslinger, W. Screw reactors and rotary kilns in biochar production – A comparative review. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2023, 174, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, F.; Brown, R.C.; Martínez, J.D. Auger reactors for pyrolysis of biomass and wastes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 102, 372–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, H.; Stahl, A.; Frerichs, H. NCHS-Elementaranalyse: M02.001. Available online: https://www.tuhh.de/zentrallabor/methoden/ac-methoden/m02001.html (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Choi, H.; Zhang, K.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Oerther, D.B.; Sorial, G.A. Influence of cross-flow velocity on membrane performance during filtration of biological suspension. Journal of Membrane Science 2005, 248, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, N.; Das, D.B.; Starov, V.M. Filtration of natural organic matter using ultrafiltration membranes for drinking water purposes: Circular cross-flow compared with stirred dead end flow. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 276, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, A.; Thi, H.N.; Legentilhomme, P.; Jaouen, P. Dead-end and tangential ultrafiltration of natural salted water: Influence of operating parameters on specific energy consumption. Journal of Membrane Science 2011, 380, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, S.J. Membrane technology costs and me. Water Research 2017, 122, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, A.I.; Fane, A.G.; Waite, T.D. Cost factors and chemical pretreatment effects in the membrane filtration of waters containing natural organic matter. Water Research 2001, 35, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Natural gas price statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Natural_gas_price_statistics#Natural_gas_prices_for_non-household_consumers (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Vegas, R.; Alonso, J.L.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Processing of rice husk autohydrolysis liquors for obtaining food ingredients. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2004, 52, 7311–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.J.; Garrote, G.; Alonso, J.L.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Refining of autohydrolysis liquors for manufacturing xylooligosaccharides: evaluation of operational strategies. Bioresource Technology 2005, 96, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, M.R.; Hackney, J.; Sethi, S.; Jacangelo, J.G.; Laîé, J.-M. Cost estimates for membrane filtration and conventional treatment. Journal AWWA 1994, 86, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hliavitskaya, T.; Plisko, T.; Pratsenko, S.; Bildyukevich, A.; Lipnizki, F.; Rodrigues, G.; Sjölin, M. Development of antifouling ultrafiltration PES membranes for concentration of hemicellulose. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2021, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S; P Global. Molasses and Feed Ingredients Market Analysis. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/ci/products/food-commodities-food-manufacturing-softs-molasses-feed-ingredients.html (accessed on 14 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).