Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Excessive dietary sodium intake is a major risk factor for hypertension, prompting interest in potassium chloride (KCl) as a sodium chloride (NaCl) alternative. While KCl preserves saltiness, its neural processing compared to NaCl remains underexplored. This study investigates the neural correlates of taste perception for NaCl, KCl, and their mixture using gustatory event-related potentials (ERPs) in a sample of Twenty-eight healthy young adults. Participants rated the intensity, saltiness, and pleasantness of the stimuli, which were matched for iso-intensity and iso-pleasantness. High-density EEG data revealed distinct microstate patterns associated with each condition, particularly in the later stages of processing, which align with the endogenous phases of taste perception. Source localization identified the insula and opercular regions as primary sites for gustatory processing, with specific differences in activation patterns between NaCl and KCl. These findings suggest that while KCl elicits comparable behavioral responses to NaCl, its neural representation involves unique processes that may reflect its distinct chemical properties. This study advances our understanding of the neural dynamics of salt taste perception, providing insights into the potential use of KCl as a potentially healthier alternative in dietary interventions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Study Design

2.3. Stimuli

2.4. EEG Acquisition and Data Analysis

2.5. Topographical Analysis and Source Localization

2.6. Demographics and Behavioral Data Analysis

3. Results

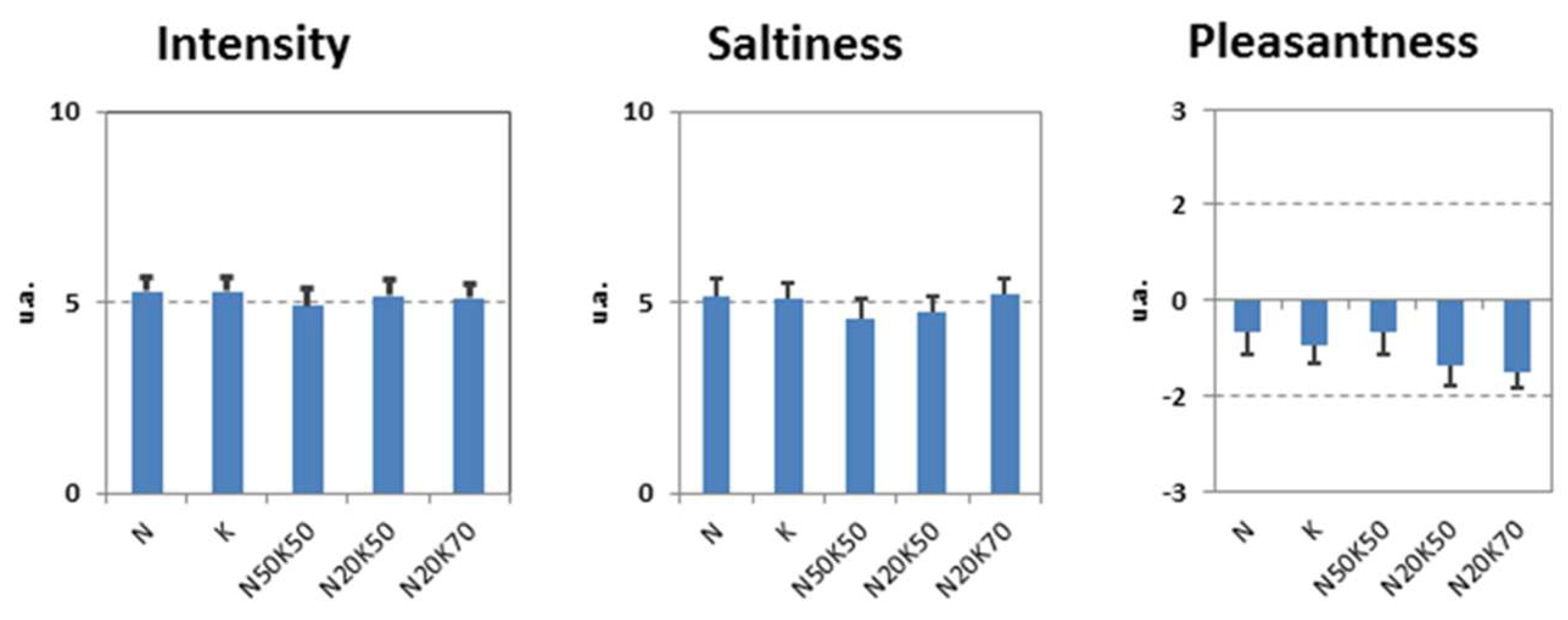

3.1. First Lab Session – Stimuli Ratings

3.2. Gustatory ERPs

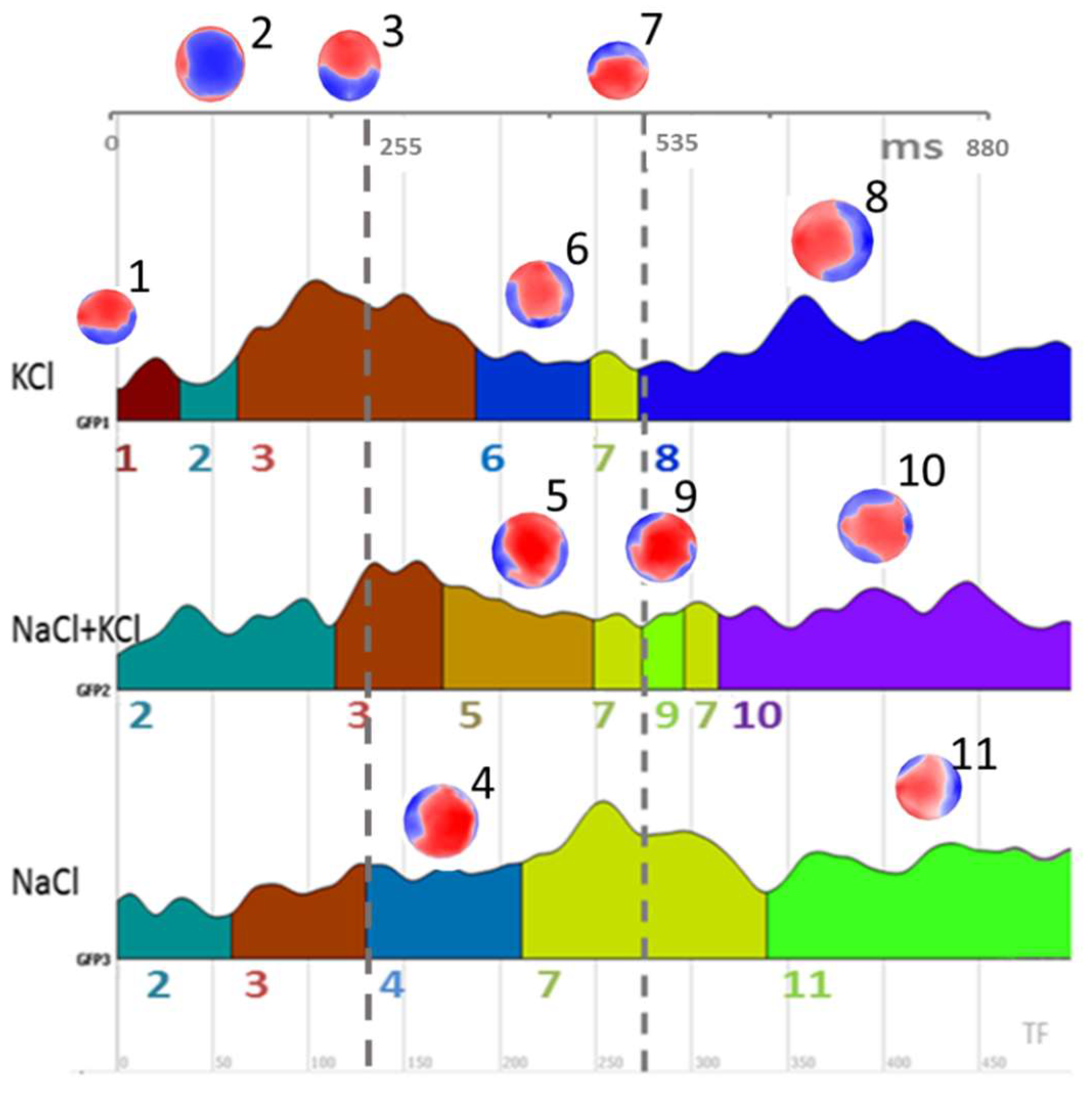

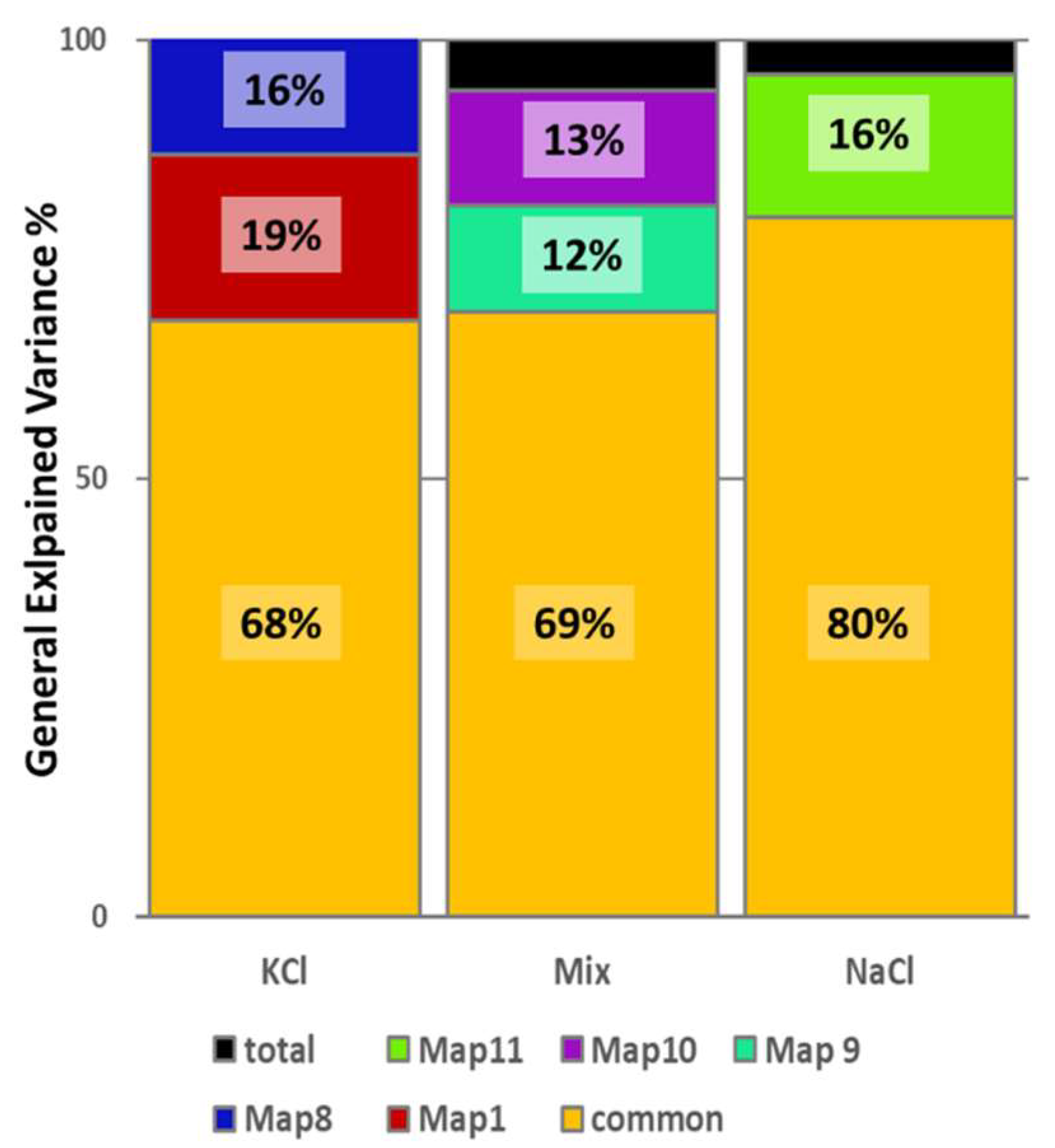

3.3. Microstates Segmentation

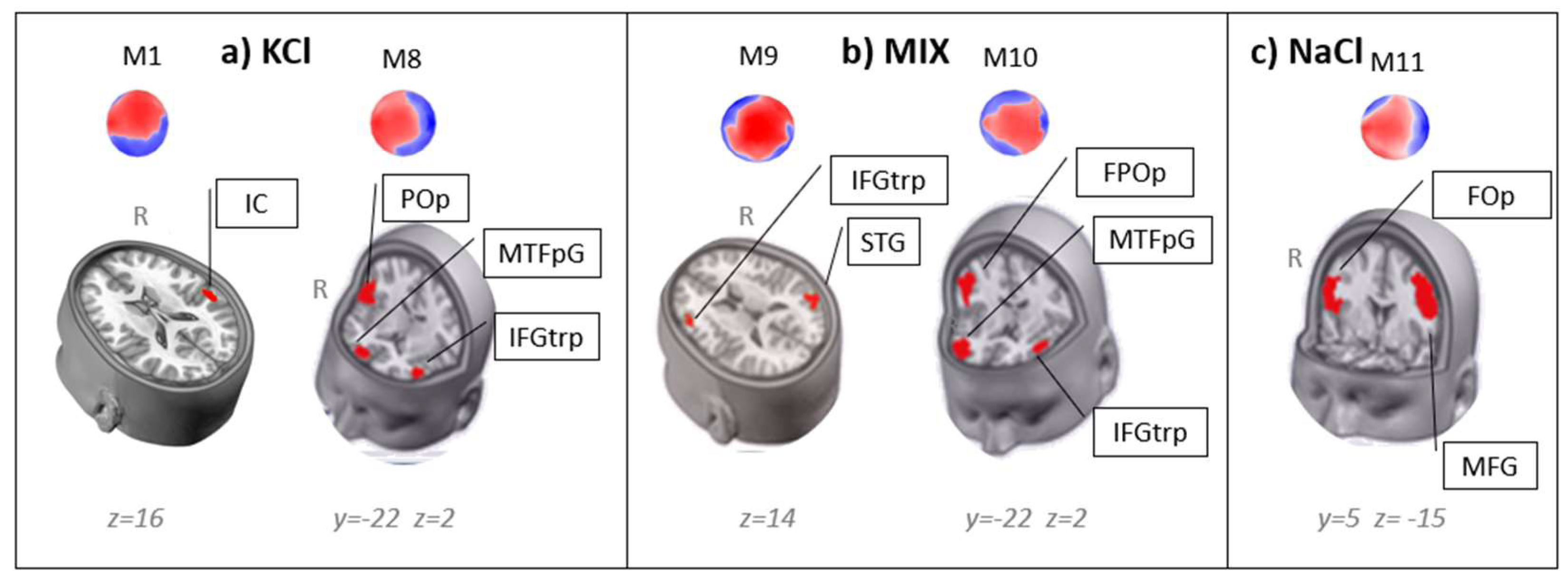

3.4. Sources Localization on the Microstates Specific for Each Condition

4. Discussion

4.1. Palatability of the Potassium Chloride

4.2. Scalp Topography and Brain Sources of Salty-taste

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aburto, N.J.; Ziolkovska, A.; et al. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013, 346, f1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez-Rattoni, F. Molecular mechanisms of taste-recognition memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez-Rattoni, F. The forgotten insular cortex: Its role on recognition memory formation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2014, 109, 207–216, (2001). "Mouse taste cells with glialike membrane properties." J Neurophysiol 85(4): 1552-1560.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushara, K.; Hanakawa, T.; Immisch, I.; Toma, K.; Kansaku, K.; Hallett, M. Neural correlates of cross-modal binding. Nat. Neurosci. 2003, 6, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikazoe, J.; Lee, D.H.; Kriegeskorte, N.; Anderson, A.K. Distinct representations of basic taste qualities in human gustatory cortex. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.; Chen, K.; Bandy, D.; Reiman, E. Thermosensory activation of insular cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, M.; Lopez, A.D.; et al. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002, 360, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal-Ben-Ari, S.; Rosenblum, K. Molecular mechanisms underlying memory consolidation of taste information in the cortex. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2012, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooge, S.; Chambers, D. A comparison of basic taste modalities, using a descriptive analysis technique, for varying levels of sodium and KCl in two model soup systems. J Sens Stud 2010, 25, 521–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, A.; Gleichgerrcht, E.; Manes, F. Clinical effects of insular damage in humans. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannilli, E.; Gudziol, V. Gustatory pathway in humans: A review of models of taste perception and their potential lateralization. Journal of neuroscience research 2019, 97, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, E.; Singh, P.B.; Schuster, B.; Gerber, J.; Hummel, T. Taste laterality studied by means of umami and salt stimuli: An fMRI study. Neuroimage, 2012, 60, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannilli, E. (2023). Electroencephalography and Gustatory Event-Related Potentials Measures to Oral Stimuli. In Basic Protocols on Emotions, Senses, and Foods (pp. 247-262). New York, NY: Springer US.

- Jacobson, M.F. 2005. Salt the forgotten killer. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest, 27 p.

- Kearney, P.M.; Whelton, M.; et al. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005, 365, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilcast, D.; Angus, F. 2007. Reducing salt in foods: Practical strategies. Woodhead Publishing in Food science, Technology and Nutrition, pp. 130–210.

- Li, N.; Prescott, J.; et al. The effects of a reduced-sodium, high-potassium salt substitute on food taste and acceptability in rural northern China. Br J Nutr 2009, 101, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mălîia, M.D.; Donos, C.; Barborica, A.; Popa, I.; Ciurea, J.; Cinatti, S.; Mîndruţă, I. Functional mapping and effective connectivity of the human operculum. Cortex 2018, 109, 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, L.; Royet, J.P.; Catenoix, H.; Montavont, A.; Isnard, J.; Mauguière, F. Gustatory and olfactory responses to stimulation of the human insula. Annals of neurology, 2017, 82, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; Schriever, V.A.; Croy, I.; Haehner, A.; Hummel, T. Updated Sniffin’Sticks normative data based on an extended sample of 9139 subjects. European Archives of Oto-rhino-laryngology, 2019, 276, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pause, B.M.; Sojka, B.; Krauel, K.; Ferstl, R. The nature of the late positive complex within the olfactory event-related potential (OERP). Psychophysiology, 1996, 33, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, T.; Macaluso, D.; Eslinger, P. Taste perception in patients with insular cortex lesions. Behav. Neurosci. 1999, 113, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 2001, 344, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherg, M.; Von Cramon, D. A new interpretation of the generators of BAEP waves I–V: Results of a spatio-temporal dipole model. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section, 1985, 62, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, B.; Iannilli, E.; et al. Gustatory testing for clinicians. B-ENT 2009, 5 (Suppl 13), 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Small, D.M. Taste representation in the human insula. Brain Structure and Function 2010, 214, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; He, J.; et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. JAMA 1997, 277, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Map | Talairach | Microscopic Atlas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl | M1 | 40 | -20 | 16 | Insula / Rolandic Operculum | RPS38 | |

| M8 | -48 | 38 | 2 | Inferior Frontal Gyrus triangular part | LAI371 | ||

| 4 | 58 | -2 | Medial Transverse Frontopolar Gyrus | RAI 431 | |||

| 43 | -27 | 22 | Parietal Operculum | RPS 171 | |||

| Mixture | M9 | 50 | -60 | 19 | Superior Temporal Gyrus | RPS144 | |

| -48 | 31 | 14 | Inferior Frontal Gyrus triangular part/ Medial Frontal Gyrus | LAS624 | |||

| M10 | 57 | -16 | 22 | Frontoparietal Operculum | RAS52 | ||

| 24 | 57 | 3 | Medial Transverse Frontopolar Gyrus | RAI265 | |||

| -48 | 38 | 2 | Inferior Frontal Gyrus triangular part | LAI 371 | |||

| NaCl | M11 | 51 | 5 | 16 | Frontal Operculum | RAS33 | |

| -45 | 2 | 42 | Medial Frontal Gyrus | LAS637 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).