1. Introduction

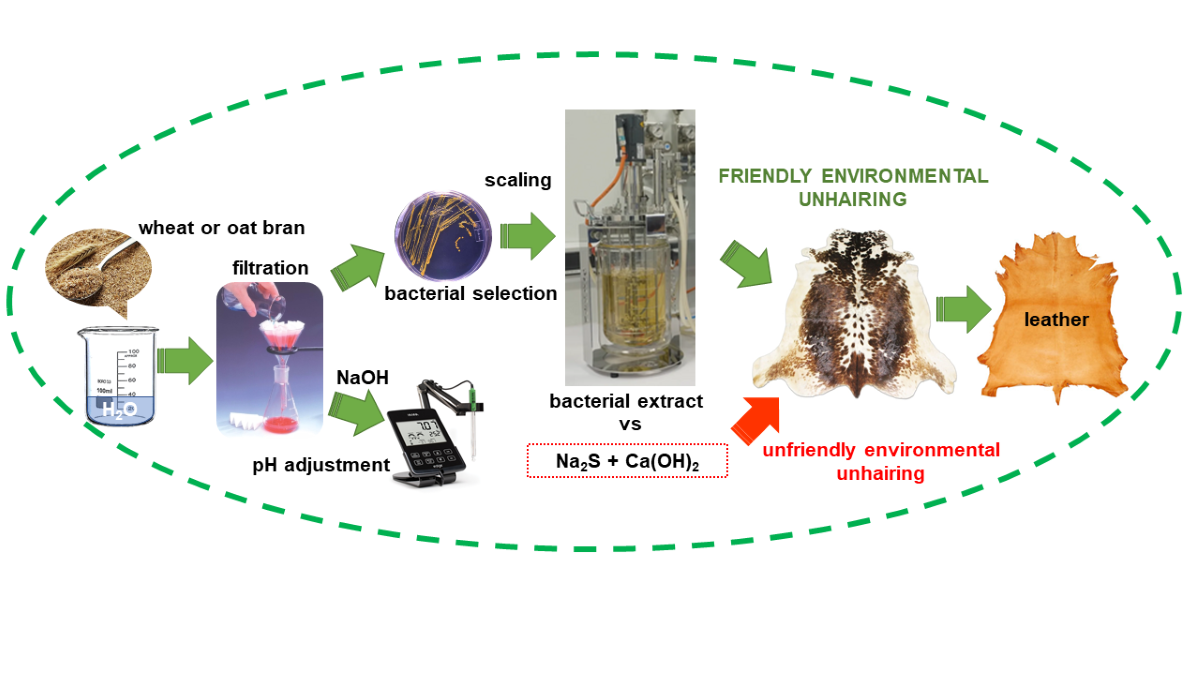

In order for raw hide to be used as a consumer good, it must undergo the tanning process. This process chemically stabilizes collagen, the predominant protein in the skin. The result of this process is a material suitable for the production of consumer goods (e.g., handbags, shoes), often associated with the concept of quality.

The conventional tanning process involves the use of toxic substances and generates significant pollution [

1]. This process involves several stages, the most polluting of which is the unhairing of the hide [

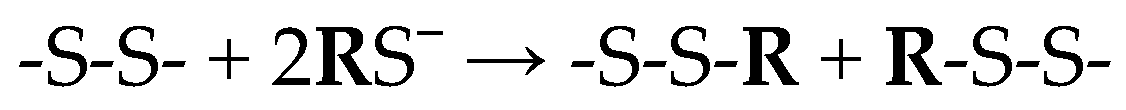

2]. In most cases, sodium sulfide/hydrosulfide and lime are used to separate the hair and epidermis from the raw hide. This combination breaks the disulfide bonds of keratin in the hair, allowing its subsequent removal (

Scheme 1):

The wastewater from this stage exhibits very high levels of parameters such as Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), and Total Suspended Solids (TSS). It also negatively impacts the operation of wastewater treatment plants [

3] and significantly complicates the reuse of the large quantity (50 kg per 1 Mg of processed raw hide) of solid waste generated [

4]. An additional, extremely serious latent problem exists, as it has been the cause of recurrent fatal accidents over the years [

5]. If, for any reason, the pH value during the unhairing process drops sufficiently to generate hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), there is a high risk of inhalation poisoning. Inhaling this gas in very small doses is fatal to humans [

6].

The substitution of sodium sulfide/hydrosulfide with alternative substances for raw hide unhairing has been the focus of numerous studies in the field of leather tanning [

7]. An unhairing system that eliminates the need for these chemical products is enzymatic depilation. This method has been used for many years on sheep skins [

8]. It is an unhairing process with limited control, primarily aimed at recovering the wool. Consequently, it often renders the skin unsuitable for further use.

The large number of research conducted in recent years has focused on performing enzymatic unhairing in a controlled manner without damaging the skin. This objective applies to all types of skins, not just sheep skin. Enzymes of various types have been tested, such as alkaline proteases [

9], keratinases [

10], metalloproteinases [

11], glycosidases [

12], and galactosidases [

13]. These enzymes originate from a wide variety of sources, e.g., tannery solid wastes [

14], fish market wastes [

15], feather wastes [

16], tannery soil [

17], seawater [

18], different plants [

19], or even from a soda lake in the Rift Valley region of Kenya [

20].

However, in spite of the efforts made, today there is no enzyme product, at least at industrial level, which, on its own, can correctly unhairing the skins without impairing their quality, causing problems such as incomplete hair removal and exfoliation, hydrolysis of collagen and grains, etc. [

21]. The objective of this work is to contribute to obtaining the enzyme or combination of enzymes that can be used industrially to efficiently unhairing the skins without impairing their quality. The novelty of the work consists in the use of new enzymes contained in raw extracts of bacterial cultures, and not tested so far as an unhairing agent. The raw materials used in the research to obtain the unhairing product were wheat bran and oat bran. Both are considered agri-food wastes. Different types of microbes from agri-food wastes are known to produce enzymes that have applications in various industrial processes [

22].

Wheat bran is one of three layers of the wheat kernel, specifically, the most external one. It is the main by-product of white flour processing and is produced in large quantities globally. It is a relatively inexpensive by-product [

23]. Wheat bran is considered an agri-food waste. The full potential of agri-food wastes as renewable resources remains unexploited [

24]. Approximately 15.5 million tm protein from wheat bran are wasted annually worldwide [

25]. Apart from being an essential source of dietary fiber, wheat bran also comprises a high proportion of protein, fat, minerals, starch, B-vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds [

26]. The potential of wheat bran is underutilized, and its application value requires further exploration. Thus, advancing the comprehensive use of wheat bran can significantly minimize waste and create economic benefits for the wheat industry. [

27]. In recent years, many studies have been carried out with the objective of recycling such solid waste [

28,

29,

30]. The use of wheat bran has been studied in several fields such as enzyme production, metabolites production, biofuels production, heavy metal removal, and food-feed additive [

31].

Oat bran is produced by rolling and/or milling of oats and its separating by sieving or other suitable means to obtain the oat flour. By-product oat bran fraction is not more than 50% of the original biomaterial [

32]. Oat bran is another major agro-industrial by-product that comprises the richest in dietary fiber part of oats. It is characterized by a high protein content and is considered as a high source of minerals, vitamins and soluble β-glucan. Oat bran is extensively used in the human diet, since it is well established that improves the intestinal microflora and reduces the level of cholesterol and glucose in the blood [

33]. Additionally, it is used as a dietary supplement for feeding various animals, such as pigs [

34]. Finally, the research fits into the premises of the circular economy, recycling agri-food wastes and developing a new and more eco-friendly agent for raw hide unhairing.

2. Results and Discussion

The research was divided into two parts. First, several tests were conducted to determine the optimal maceration conditions for wheat and oat bran. Second, other tests were carried out to characterize the unhairing active agents found in both types of bran.

2.1. Determination of Optimal Conditions for Unhairing Activity in the Studied Bran

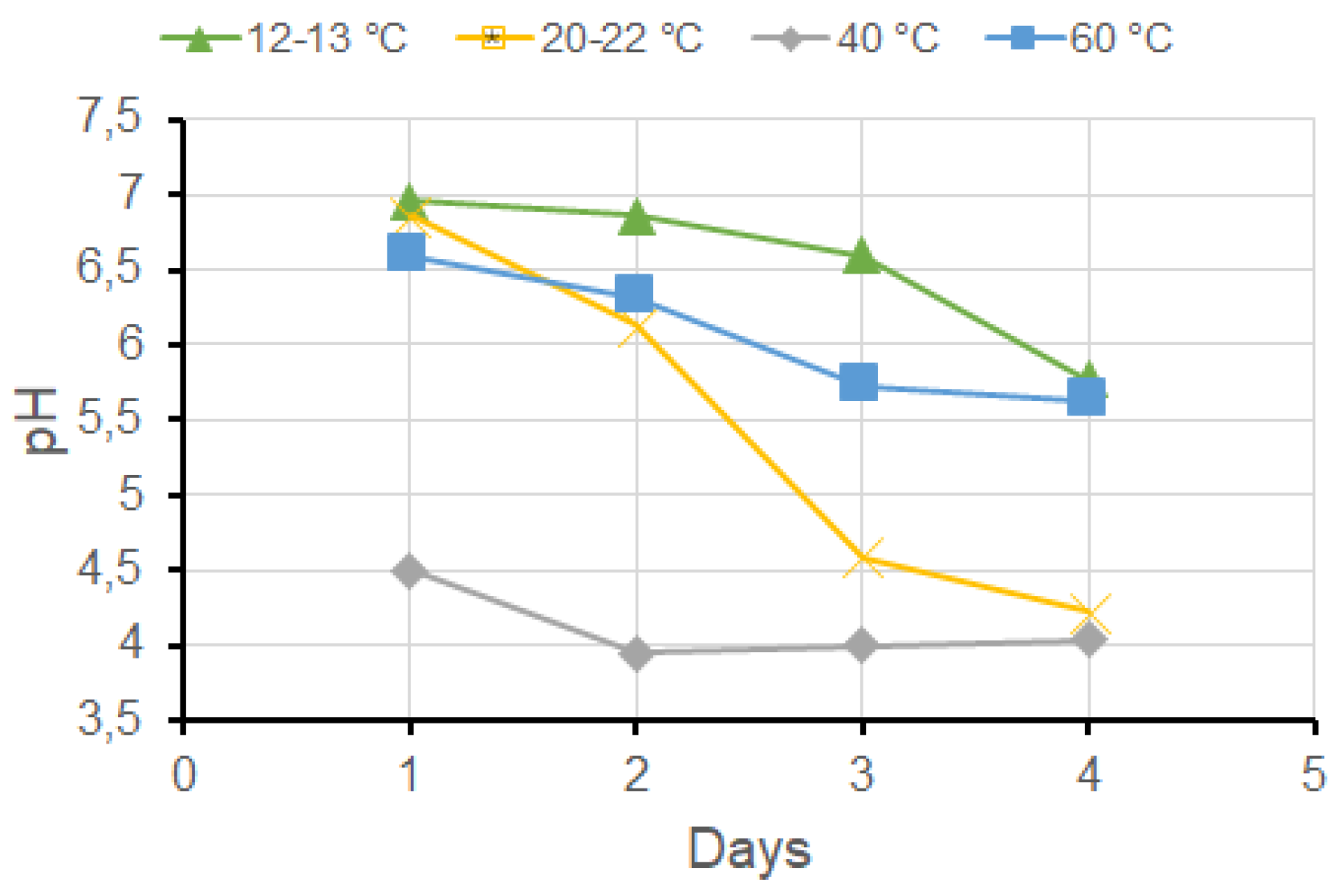

2.1.1. Study of Optimal Maceration Temperature

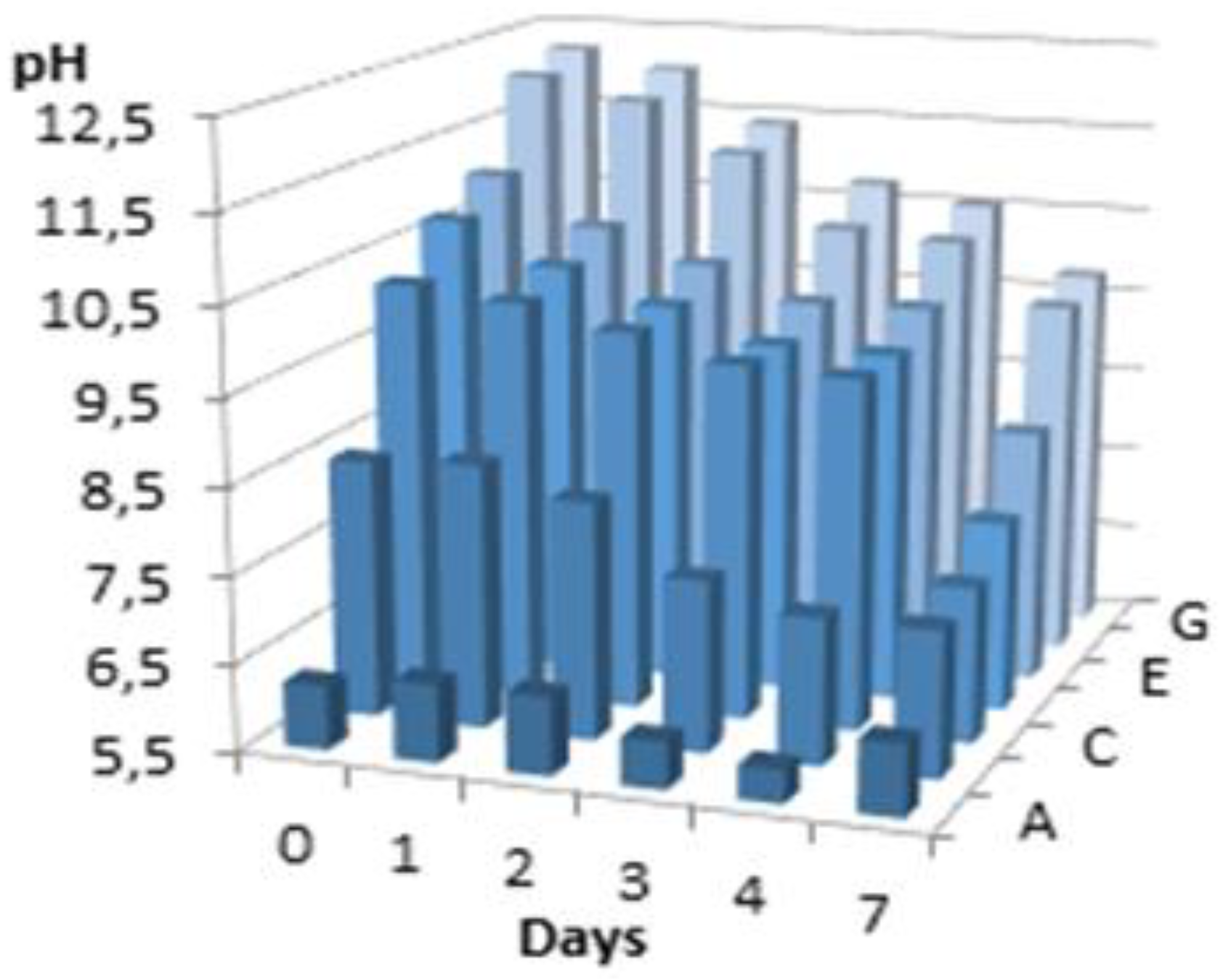

The wheat and oat bran were macerated in water (10 %-w/w) at different temperatures, with daily monitoring of pH variations in each mixture. The results obtained for wheat bran are presented in

Figure 1. The results for oat bran maceration were very similar.

As the temperature increases, the pH of the mixture progressively decreases, and the rate of pH stabilization increases. However, when maceration was performed at 60 °C, the results did not follow the same trend. Due to this anomalous behavior and the fact that hide denatures at this temperature, subsequent tests were conducted at 40 °C, where pH stabilization occurs more rapidly.

2.1.2. Study of the Behavior of the Aqueous extract of the Macerate Against Basification

Since the pH at which the aqueous macerate extract can unhairing skin was unknown, its response to the addition of NaOH was studied. After maceration at 40 °C, the solution was allowed to rest for 48 hours, cooled to room temperature, and filtered. Seven aliquots were prepared, each adjusted to a different pH (6, 8, 10, 10.5, 11, 11.5, and 12).

Figure 2 shows the time-dependent pH variation for each aliquot in the case of wheat bran macerate. The results for oat bran macerate were very similar.

Except for samples alkalized to pH 6, all pH values decreased over time. This decrease was more pronounced in tests with lower initial pH levels. Beyond pH 11, the difference between the initial and final pH stabilized. This behavior indicates the presence of latent acidity in the solution. Adding a sufficient amount of alkali neutralizes this acidity, leading to pH stabilization. The acidification of the extract could be due to microbial growth (see

Section 2.2.5 below) and products/by-products of their metabolism, e.g., the incorporation of atmospheric CO

2 can form acid species (H

2CO

3/HCO

3 ¯) that could buffer the aqueous extracts.

2.1.3. Study of the Depilation Capacity of Aqueous Extracts from Macerates

The depilatory capacity was studied by adding a piece of soaked bovine hide in different macerate solutions. It was also tested whether the timing of hide addition to the depilatory solution affected the time required to easily remove hair without degrading the hide. Hide degradation was monitored visually. The layer of skin containing the hair is called “grain”. When the hide degrades, part of the grain is destroyed, exposing the underlying, much rougher layer of hide.

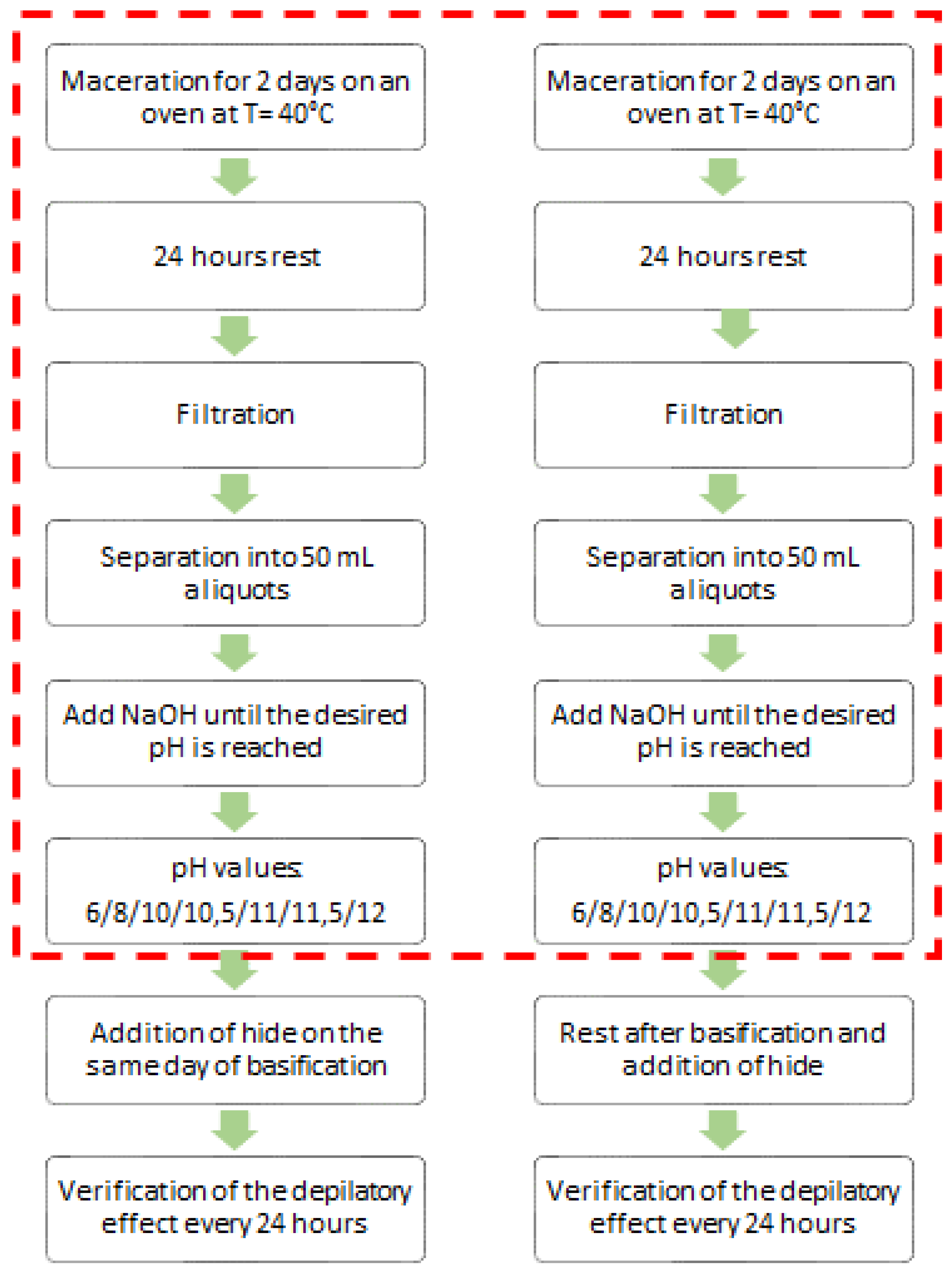

Two different procedures were followed (

Figure 3). In one, the hide was added on the same day the pH of the depilatory solution was adjusted, and the evolution of the hide was monitored every 24 hours. In the other, the interval between adjusting the pH of the depilatory solution and introducing the hide was varied.

The results obtained from wheat bran and oat bran were very similar. In both cases, after two days of basification, the depilatory solutions with an initial pH value of 12 or higher (with a final approximate pH of 11.5) caused the hair to be easily removed, and the epidermal tissue was eliminated. In the other tests, the depilatory effect was barely noticeable and/or the hide showed signs of putrefaction.

That is, the depilatory substance is generated in the solution derived from the maceration of wheat or oat bran once basified to a certain pH, and a period of time is required for it to destroy the epidermis of the hide, allowing the hair to be easily removed. Once the depilatory effect of the wheat bran and oat bran macerates was demonstrated, another series of tests was conducted to characterize the substance responsible for this effect.

2.2. Characterization of the Depilatory Active Agent Obtained from Wheat Bran and Oat Bran Extracts

2.2.1. Preparation of the Extracts

The two extracts (wheat bran and oat bran) were prepared following the same procedure, as explained in the Materials and Methods section (see

Figure 3). The resulting solutions, adjusted to pH 12.5, were stored frozen at -20 °C.

2.2.2. Effect of Dialysis on the Extracts

The pH, conductivity, and protein content of two 80 mL aliquots of the previously thawed and stabilized bran extracts at 20 °C were monitored. These aliquots were subjected to a dialysis process, and the same controls were performed. The results are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, where OB and WB refer to the oat bran and wheat bran aliquots, respectively. The prepared aqueous extracts were dialyzed against water supplemented with sodium azide to avoid contamination by microbiological growth. A phosphate buffer saline (PBS) sample was included in the study as a control.

The dialysis of depilatory extracts from oat and wheat bran demonstrates that the process effectively removes numerous salts that contribute to the conductivity of the extracts. Moreover, it is noteworthy that even after dialysis (starting from extracts with a pH of 12), the pH remains within the alkaline range, stabilizing at approximately pH 8.5 (

Table 1). This result may suggest that the extracts contain certain component(s) or mechanism(s) that enable pH buffering. On the other hand, dialysis also reveals the removal of low molecular weight peptides (e.g., below 5 kDa, because the pore size of the dialysis membrane had a cutoff of 5 kDa), which are more abundant in the wheat bran extracts, where the protein content reduction reached nearly 40%, compared to a 20% loss in the oat bran extract (

Table 2).

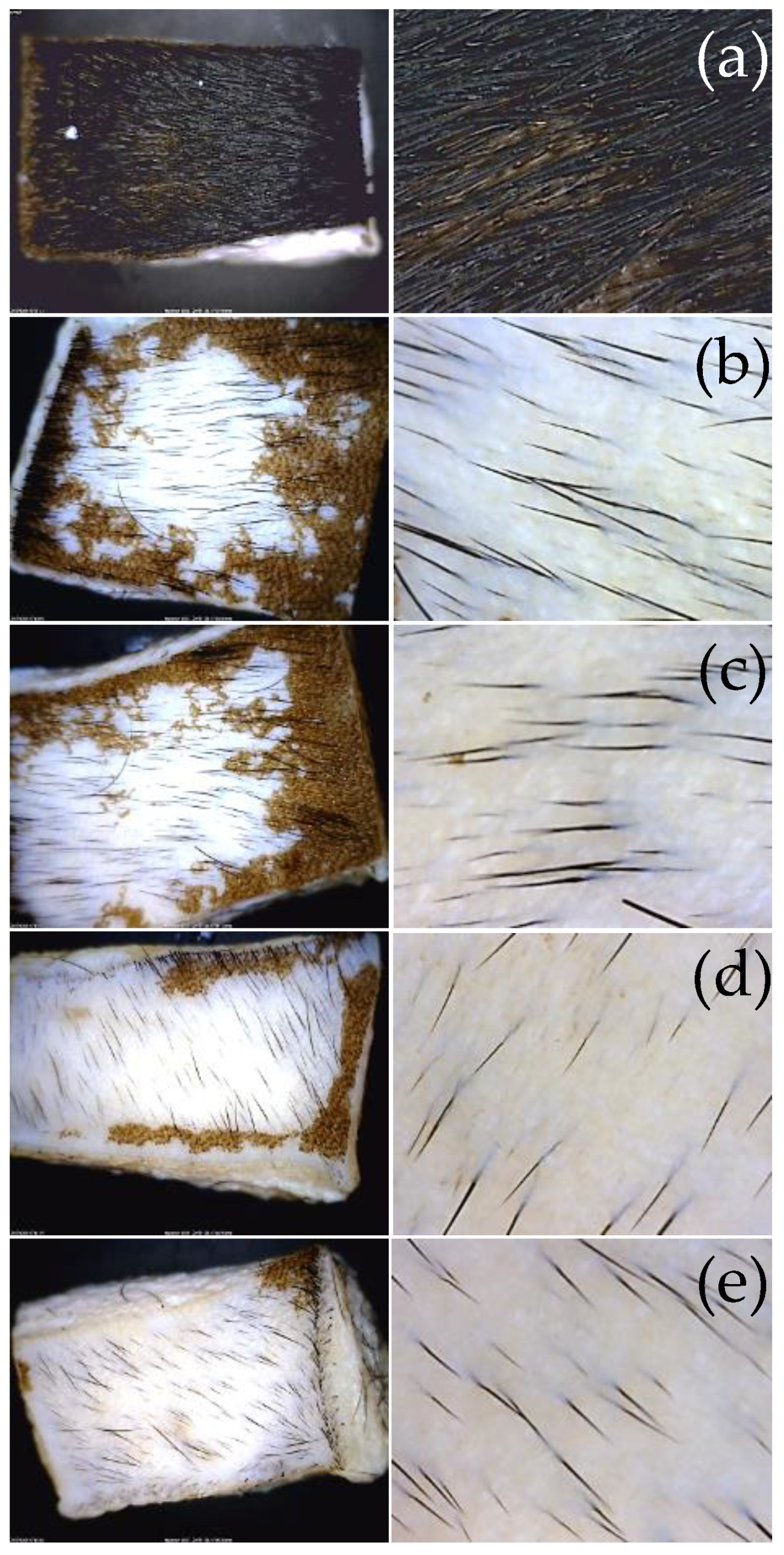

The depilatory activity on pieces of hide was compared between the extracts before and after dialysis.

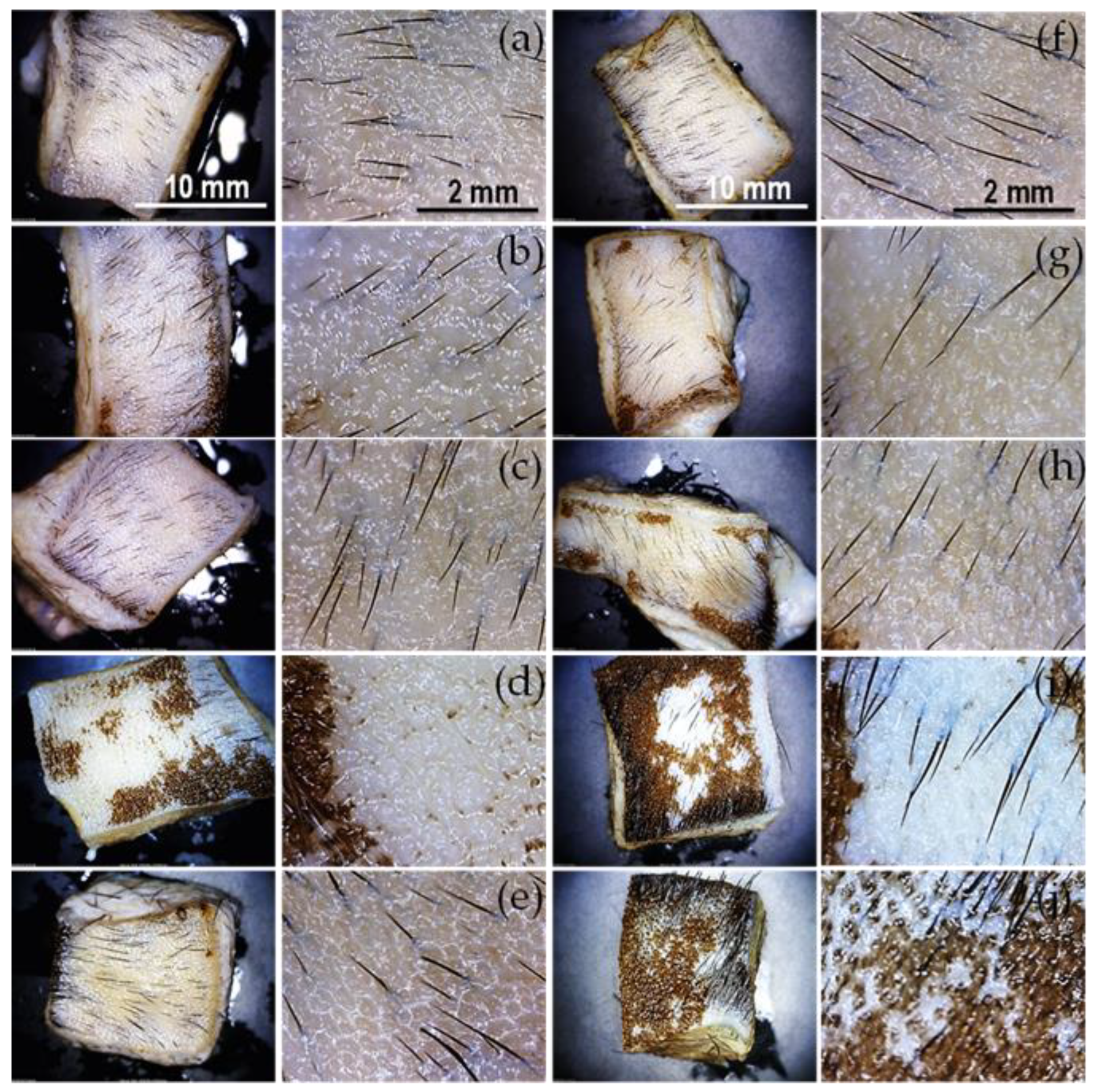

Figure 4 shows optical microscopy images of the appearance of the hide pieces before and after treatment with the extracts. These images demonstrate that the depilatory activity is maintained after dialysis of the extracts and therefore suggest that the activity could correspond to macromolecular components of the extracts. In addition, it is shown that together with the removal of hair, the grain on the skin is maintained.

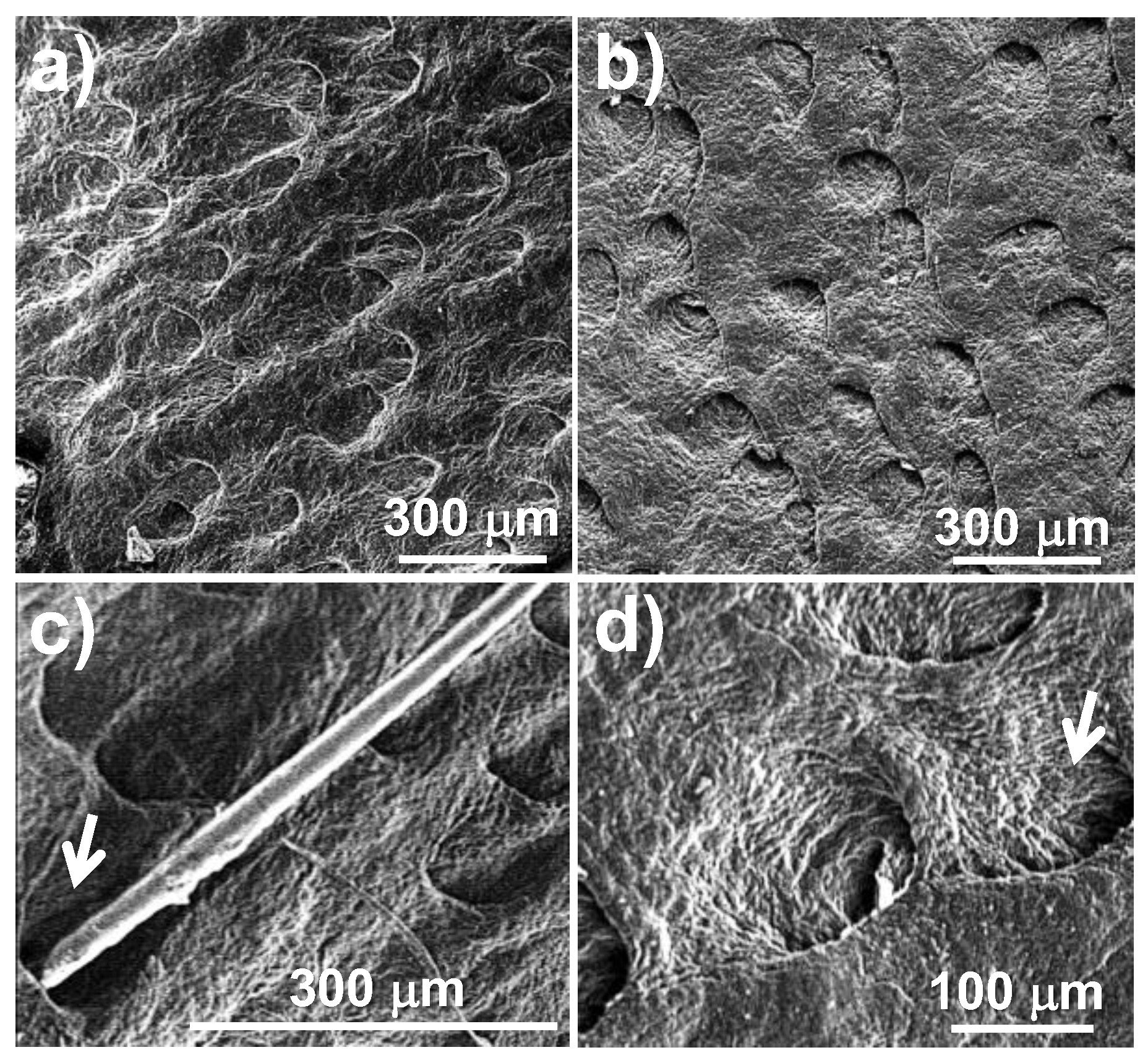

Figure 5 presents the same comparison for depilatory activity, but with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, where the correct morphology of the depilated skin surface is shown in detail, highlighting the grain of the surface and the integrity of the pores after depilation.

Finally, the depilatory activity assay demonstrates that this activity is retained in the extracts after dialysis and pH adjustment to 12. Thus, it can be inferred that the potential depilatory proteins correspond to activities with a molecular weight greater than 5 kDa. The hide treated with these activities shows that hair can be easily removed manually and that it does not undergo hydrolysis (e.g., in

Figure 4c, the hair’s integrity is clearly visible). The activity corresponds to the removal of the epidermis while leaving the hide grain intact (

Figure 4). This result is clearly observed through scanning electron microscopy, where the structure of the pore containing the hair follicle bulb is seen to be cleared of hair while maintaining its morphology. Furthermore, the hide grain remains intact, as evidenced by the presence of cutaneous folds (

Figure 5). These findings suggest that the depilatory activity of oat bran and wheat bran extracts may offer advantages over currently applied methods that alter the integrity of the treated skin surface.

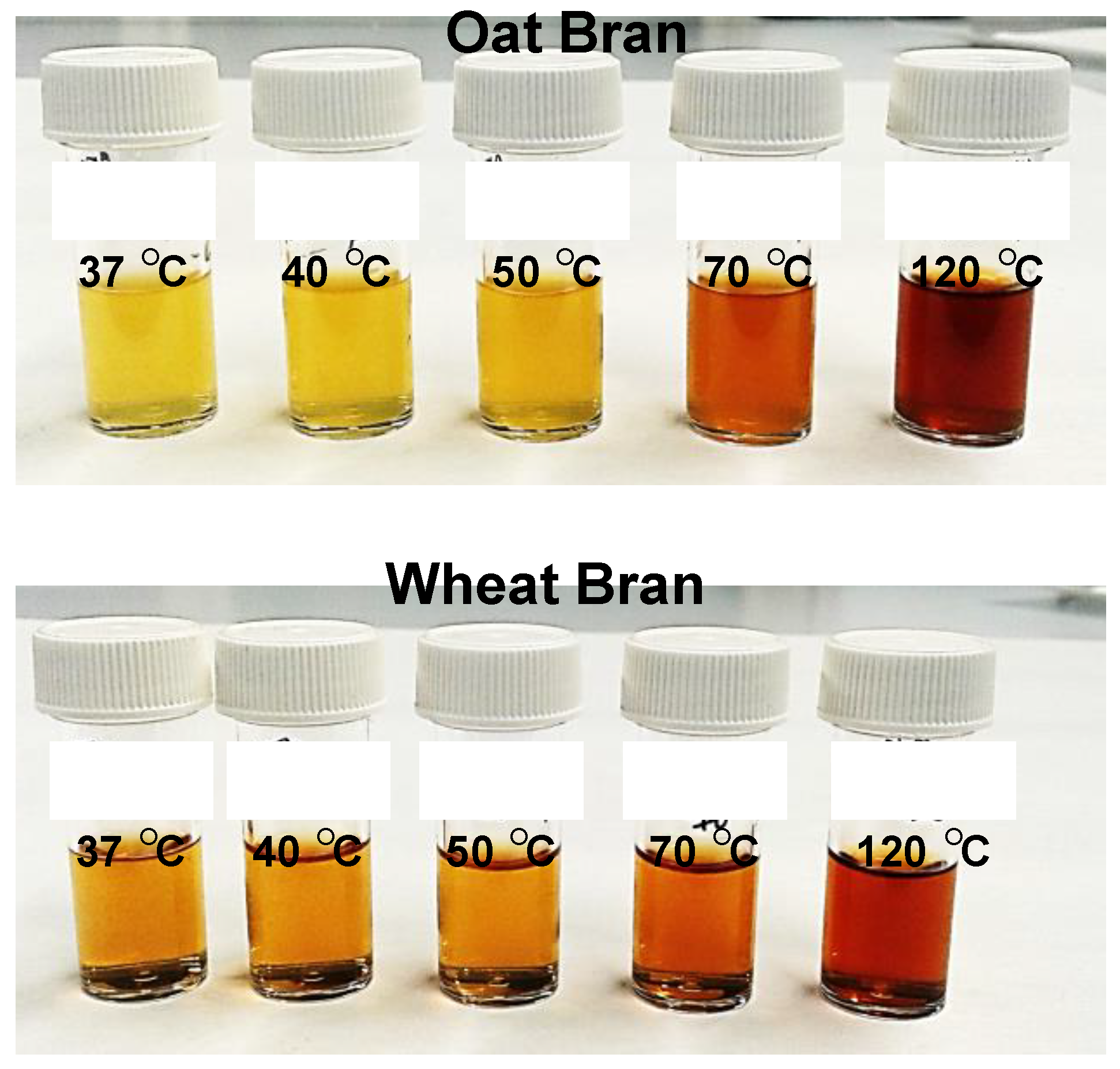

2.2.3. Thermal Stability of the Extracts

The effect of temperature on the depilatory activity of the extracts was studied. For this purpose, samples of each extract were maintained at temperatures of 37, 40, 50, 50, 70 and 120 °C for 1 h. The samples were allowed to stabilize at room temperature and were centrifuged.

Figure 6 illustrates the appearance of the extracts after thermal treatment.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the depilated hide grains with the extracts after dialysis. Hide depilated with oat extract (a) and wheat extract (b). A close-up of a hair trapped in a pore (see arrow) (c), and pores without hair after depilation, showing the granulation of the skin (see arrow) (d).

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the depilated hide grains with the extracts after dialysis. Hide depilated with oat extract (a) and wheat extract (b). A close-up of a hair trapped in a pore (see arrow) (c), and pores without hair after depilation, showing the granulation of the skin (see arrow) (d).

Following the same procedures as in the previous section, the pH, protein concentration, and conductivity of the extracts were measured. The results are presented in

Table 3. Additionally, the depilatory activity of these extracts was tested, as shown in

Figure 7.

The heat treatment of the extracts shows an important content of sugars that can be caramelized at 70 °C and above. This is more evident in the oat extract because it has an initial yellowish coloration which transforms into an intense brown during heating at 70 °C and 120 °C (

Figure 6). Possibly, this is the decomposition of sucrose into glucose and fructose and even some acetic acid may be formed. This may be in agreement with the results shown in

Table 3, where an increase in conductivity can be observed as a consequence of the number of molecules and along with it the acidification. At high temperature (120 °C) it is possible that some non-enzymatic glycosylation of the proteins occurs (Maillard reaction). However, the high protein content together with the decrease in the depilatory activity observed at 70 °C and above (

Figure 7) suggest a thermal denaturation by misfolding of the proteins. In conclusion, it could be indicated that the depilatory activity of the extracts is thermosensitive at 70 °C.

2.2.4. Effect of pH on the Depilatory Activity of the Extracts

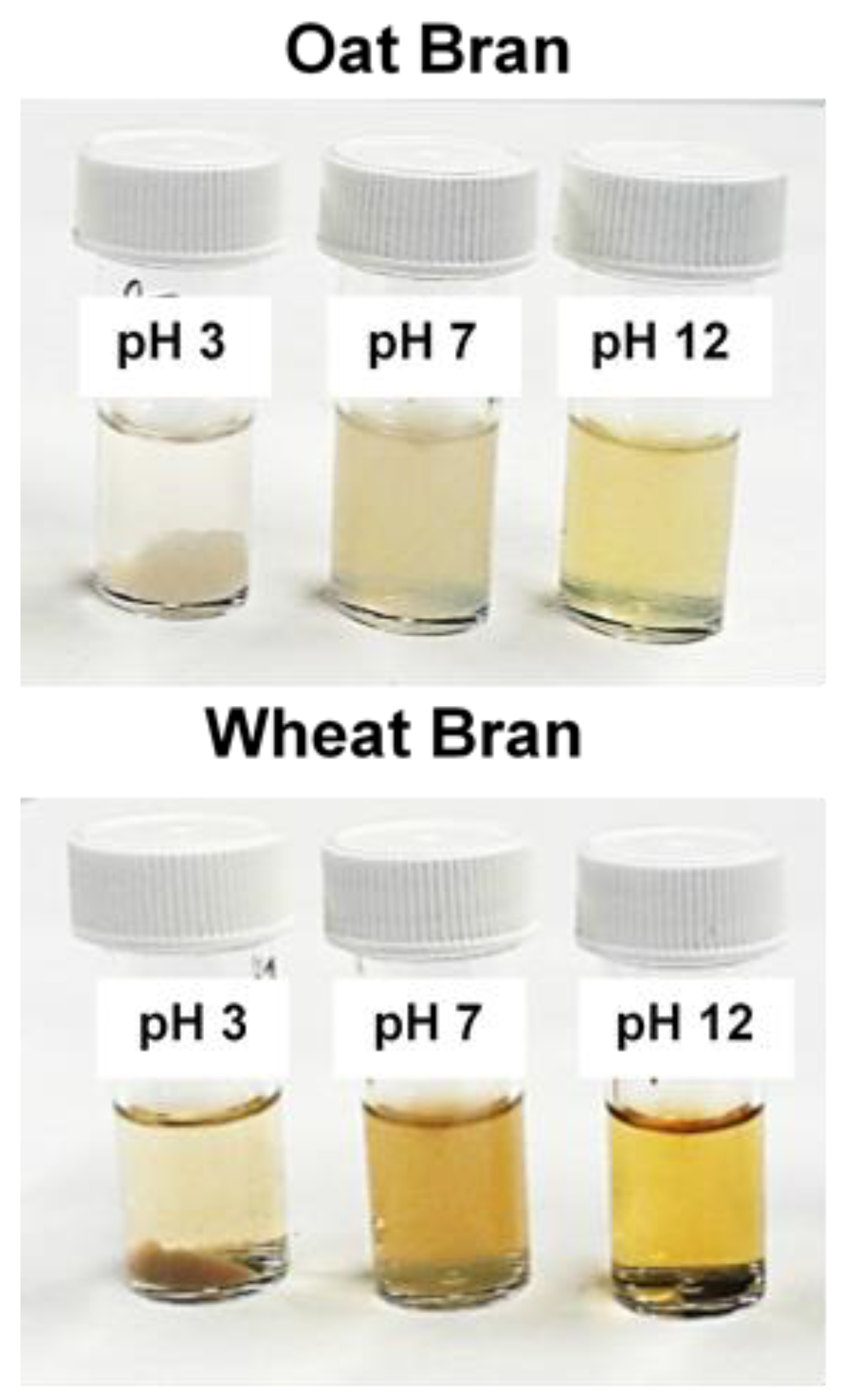

The dialyzed extracts were aliquoted into 3 mL volumes in polystyrene vials. The extracts were adjusted to three different pH values: 3, 7, and 12 (acidic, neutral, and alkaline, respectively). To achieve this, the extracts were alkalized with 4 M NaOH and acidified with 12 M HCl. During the acidification process, sediments formed (

Figure 8), which were separated by centrifugation after stabilizing the extracts for 24 hours at 4 °C.

The protein concentration and conductivity of each sample were determined (

Table 4), as well as the depilatory activity of each sample (

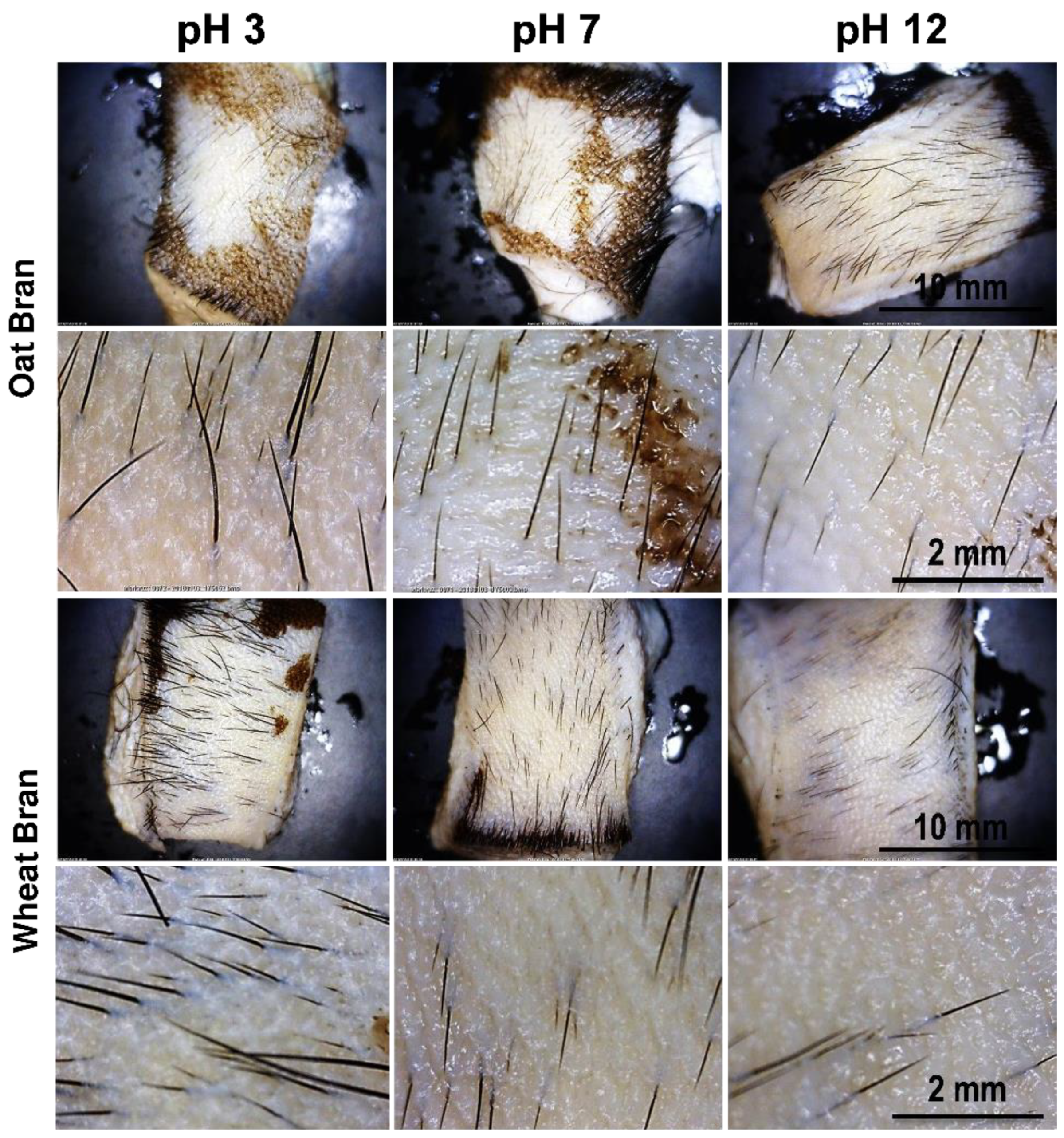

Figure 9). It is clearly observed that the protein concentration decreases at acidic pH and this could be related to the formation of sediment, possibly due to the formation of complexes because the conductivity also decreases in the same way. The opposite occurs when the extract has a basic pH and an increase in its solubility is clearly shown.

The depilatory activity of oat bran and wheat bran extracts as a function of pH adjustment (

Figure 9) demonstrated that at acidic and neutral pH, depilatory activity is maintained partially or defectively. This is evidenced by residual epidermis appearing as spots on the surface of treated samples. On the other hand, at alkaline pH, clear depilatory activity was observed, with complete removal of the epidermis. In this regard, it is concluded that the depilatory activity of the extracts requires an alkaline pH.

2.2.5. Bacterial Cultures

Aliquots of extracts from both brans were inoculated onto BHI agar plates (brain-heart infusion medium supplemented with bacteriological agar at a concentration of 12 g/L). The plates were incubated, and 20 isolated colonies by their different morphologies and sizes were selected from each extract of bran. Each bacterial strain was cultured in broth and after growth, the bacterial pellet and the supernatant medium were separated by centrifugation. The extract was prepared from the bacterial pellet and the supernatant was used as conditioned medium. Both the bacterial extract and bacteria-free culture medium or conditioned medium were prepared by adjusted it to pH 12.

The evaluation of the depilatory activity of the bacterial extract and its corresponding conditioned medium allowed the determination of whether the factors responsible for the activity are secreted by the bacteria or remain contained within them. The colonies (20 colonies/extract) were selected for each extract and designated as OB-X (Oat Bran) and WB-X (Wheat Bran), where X corresponds to the colony's ordinal number (

Table 5).

The bacteria were isolated from independently prepared extracts. Bacterial strains OB-1 to OB-10 and OB-11 to OB-20 were isolated from two separate oat bran extracts, respectively. Similarly, strains WB-1 to WB-10 and WB-11 to WB-20 were isolated from two separate wheat bran extracts, respectively. The isolated strains were cultured to prepare conditioned media and determine their depilatory activity. The results are shown in

Table 5 and demonstrate that the conditioned media exhibit depilatory activity, which would suggest that the molecules responsible for the depilatory activity can be secreted by the bacteria.

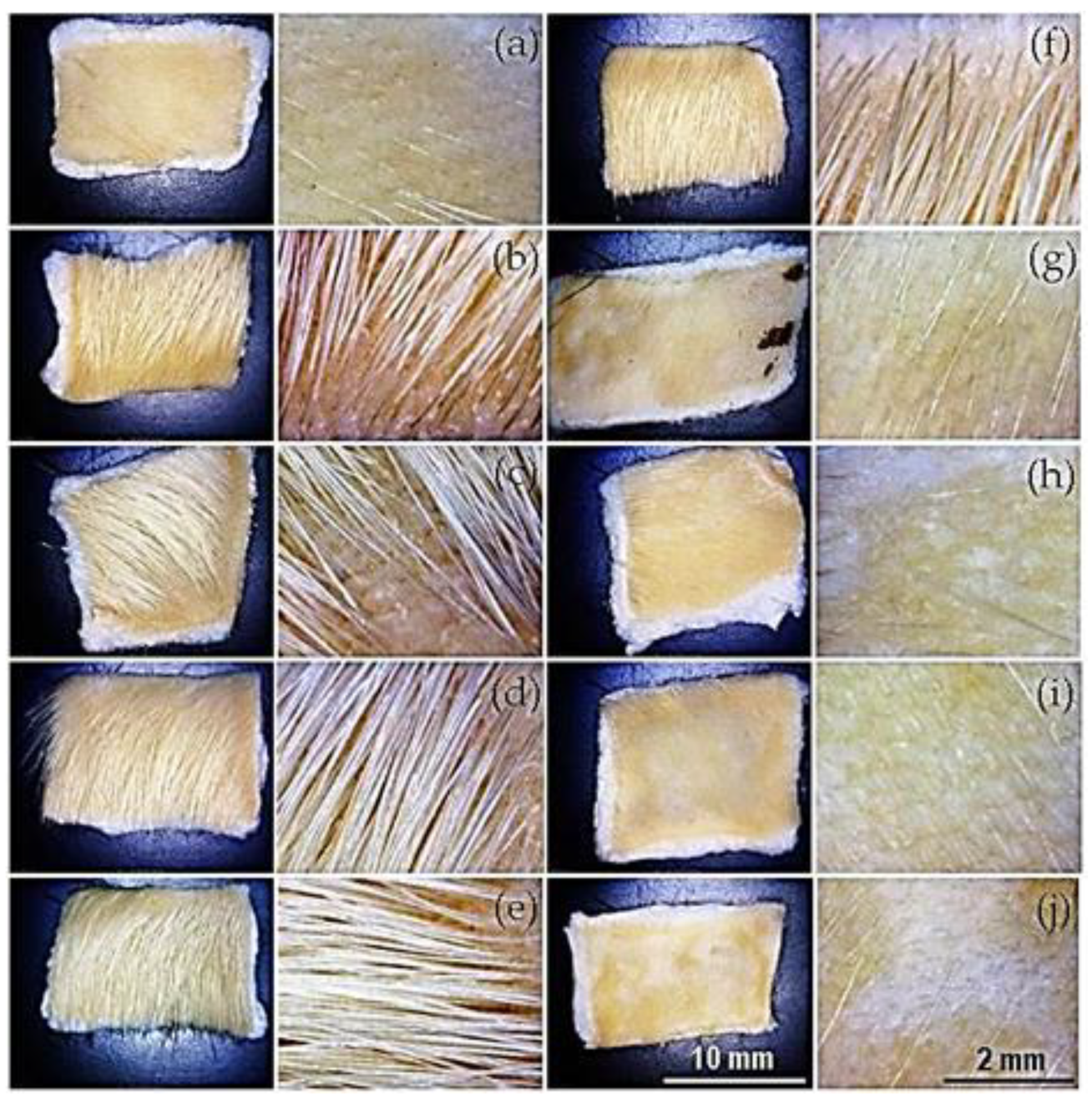

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show images of depilated hide samples treated with conditioned media and extracts from bacteria isolated from oat bran extract. Similarly,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 display images of depilated hide samples treated with conditioned media and bacterial extracts prepared from strains isolated from wheat bran extract. The qualitative results of these activities are shown in

Table 5. The highest activity corresponds to the complete depilation of the hide sample and is characterized by the preservation of the hide grain. Low activity is identified by the removal of only a few hairs while maintaining the epidermis during the depilation process, and the lack of hair removal was considered as negative activity.

In conclusion, it has been determined that the factors responsible for the depilation of the pieces of hide are produced by bacteria, and these factors can be found in the conditioned medium of the bacterial culture. This suggests that these factors may be secreted by the bacteria into the culture medium.

3. Materials and Methods

The agri-food wastes used were wheat (

Triticum aestivum) bran and oat (

Avena sativa) bran (

Figure 14). Salted bovine hide was used in all the depilation tests (GREiA Research Group, Universitat de Lleida, Igualada, Spain). All macerations corresponding to the tests in

Section 2.1 of the results section were performed by mixing either wheat bran or oat bran with drinking water and stirring manually. A laboratory oven (Nahita, Model 631/2, Navarrete, Spain) was used to control the temperature during maceration. Basifications were performed by slowly adding a 5% NaOH solution with a burette and controlling the pH with a pH-meter (Crison, MicropH2002, Alella, Spain).

The following methodology was used for the preparation of extracts (

Section 2.2.1): 30 g of bran were suspended in 300 mL of sterile ultrapure (milli-Q) water (autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min) contained in a sterile polypropylene bottle. Thus, a 10 %-w/v preparation was obtained. The suspension was incubated at 40 °C with 100 rpm orbital shaking for 4 days. The suspensions were filtered and pressed in a steel strainer to obtain the extracts. With this operation, about the initial volume (300 mL approx.) was recovered. The pH of the extracts was adjusted to 12.5 using a concentrated NaOH solution (4 M). The adjustment was carried out using magnetic stirring. In order to avoid microbial growth, the extracts were supplemented with sodium azide (using a stock of 3 %-w/v) to obtain a final concentration of 0.03 %-w/v. The extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 5000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min using a GSA rotor (equivalent to 4080 g). The supernatant obtained was recovered and filtered by gravity using No. 1 analytical paper, and pH 12.5 was checked. The bacterial pellet was preserved by freezing at -20 °C. The filtrate was clarified by centrifugation at 10000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min using a GSA rotor (equivalent to 16319 g). The amount of sediment obtained was negligible. Therefore, clarification was performed by gravity filtration using filter paper with pore size > 20 µm (ref. CFILA0125; Scharlab S.L. Sentmenat, Barcelona, Spain). Finally, about 240 mL of each extract were recovered (

Figure 15), and stored frozen at -20 °C.

In the study of the effect of dialysis on the prepared extracts (

Section 2.2.2), the following procedure was followed: 80 mL of the oat bran and wheat bran extracts were dialyzed against distilled water for 48 h at 4 °C and gentle magnetic stirring (approx. 250 rpm). For this purpose, the extracts were deposited in 6.8 cm diameter dialysis tubes (MWCO 5000 Daltons; Spectrum Inc., Boca Raton, FL, USA). The dialysis tubes were closed at both ends with polypropylene clamps. Dialysis was performed against 5 L of distilled water, with water change every 24 h. Finally, the extracts were recovered in 50 mL polypropylene tubes to be stored at -20 °C. Previously, pH and conductivity measurements were performed. Measurements were performed with the extracts stabilized at room temperature (20 °C). The pH values were measured on a pH-meter calibrated with buffers of pH 7 and 4. Conductivity was measured directly in the extracts using a digital conductivity meter.

Protein concentration was determined by Bradford's method using a commercial reagent (Bio-Rad Lab. Inc., Hercules, California, USA) and according to the micro-method described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 5 µL of the extract was deposited in the well of a 96-well microplate and then 250 µL of Bradford's reagent was added. The plate was placed in gentle orbital shaking to procure mixing. After 30 min, the absorbance at 595 nm (λ595) was measured in a microplate reader (Biochrom, Cambridge, UK), and BSA (bovine serum albumin, Fraction V) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) was used as the standard protein.

To perform the depilatory activity assay, 3 mL of the extracts before and after dialysis were placed in small polystyrene vials of 5 mL capacity with screw cap. The pH was measured and if necessary readjusted to pH 12 with 4 M NaOH. On the other hand, salted bovine hide kept frozen at -20 °C was cut into small pieces of approximately 2x2 cm area. They were then thoroughly desalted using potable water and finally distilled water under gentle magnetic stirring (250 rpm). Then, they were kept for 1 h in 0.06 %-w/v sodium azide solution under orbital agitation (100 rpm). This last operation was performed in order to sanitize them to avoid microbial growth. The pieces of hide were removed from the solution and kept frozen at -20 °C until use.

To perform the depilatory activity assay, the thawed hide sample at room temperature was placed in a vial containing the extract to be tested. The vials were sealed to prevent evaporation and contamination and maintained for 3 hours at 40 °C with orbital shaking at 100 rpm. A control for the effect of pH (alkalinization) was performed using 0.1 M PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) at pH 11.26, supplemented with sodium azide at a final concentration of 0.03 %-w/v. Subsequently, the hide samples were removed with tweezers, and manual depilation was carried out by pulling the hairs in the direction opposite to their natural alignment. The samples were rinsed with drinking water and subsequently with distilled water. The air-dried samples were photographed using an optical microscope (Dino-Lite Europe, Netherlands) for morphological surface analysis. The samples were then placed in clean vials and fixed with 2 mL of a 2.5 %-v/v aqueous formaldehyde solution. Fixation was carried out overnight at 4 °C, followed by dehydration through a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 90, 95, and 100%) for 30 minutes in each alcohol. Finally, the samples were air-dried and prepared by carbon evaporation for observation via scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Neon 40, Jena, Germany).

To study the effect of temperature on the depilatory activity of the extracts (

Section 2.2.3), 5 mL of each extract were incubated in different ovens at temperatures of 37, 40, 50, 70, and 120 °C for 1 hour. The extracts were placed in 12 mL polystyrene tubes with screw caps, while a glass tube with a Bakelite cap was used for incubation at 120 °C. The tubes were stabilized at room temperature for 15 minutes and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. No sediment formation was observed during this process. Consequently, the extracts were filtered under positive pressure using 0.22 µm pore-sized nitrocellulose syringe filters. The pH, protein concentration, and conductivity values were measured, and the depilatory activity of these extracts was tested.

To perform bacterial cultures and subsequent tests (

Section 2.2.5), the following procedure was followed: 10 g of bran were suspended in 100 mL of sterile ultrapure water (Milli-Q, Millipore Corp., Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) that had been autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 minutes, contained in a sterile polypropylene flask. This yielded a 10 %-w/v preparation. The suspension was incubated at 40 °C with orbital shaking at 100 rpm for 4 days. Using a sterile inoculating loop (5 µL), aliquots were taken and streaked onto BHI agar plates (brain heart infusion medium supplemented with 12 g/L bacteriological agar). The inoculation was performed using the streak and exhaustion method. The plates were incubated in an inverted position at 40 °C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the growth of colonies was observed on the BHI agar plates.

From the BHI plates, isolated colonies of different morphologies and sizes were selected. Ten colonies per extract were chosen and designated as OB-X and WB-X, where X corresponds to the sequential number (e.g., OB-1 and WB-1, respectively). To create a strain collection, these colonies were re-inoculated into 10 mL of BHI broth and incubated for 24 hours at 40 °C. Subsequently, the bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. The bacterial pellet was then resuspended in 5 mL of BHI broth supplemented with 10 %-v/v sterile glycerol. Aliquots of 1 mL were stored in Eppendorf tubes at -20 °C. To achieve greater strain variability, the process was repeated from the beginning, producing new extracts. Subsequently, an additional 10 colonies were selected for each extract. Finally, a collection of 20 colonies was prepared for each extract.

To determine the depilatory activity of the selected strains, the bacterial strains were cultured in 10 mL of BHI broth for 24 hours at 40 °C. The bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to prepare a bacterial extract. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of PBS broth supplemented with 0.03 %-w/v sodium azide, and the pH was adjusted to 12 using 3 M NaOH (approximately 15–25 µL were required). The bacteria were not subjected to any additional procedures (e.g., sonication) as it was assumed that at pH 12, the bacteria underwent alkaline hydrolysis, a routine procedure for bacterial lysis. On the other hand, the bacteria-free culture medium obtained after centrifugation of the bacterial cultures was supplemented with 100 µL of 3 %-w/v sodium azide, and the pH was adjusted to 12 using 3M NaOH. This processed culture medium was referred to as conditioned medium. In this context, the evaluation of the depilatory activity of the bacterial extract and its respective conditioned medium will allow determination of whether the factors responsible for the activity are secreted by the bacteria or remain contained within them.

4. Conclusions

The conclusion of the study conducted is that the two agri-food wastes tested, oat bran and wheat bran, contain an active principle exhibiting clear enzymatic depilatory activity. This conclusion expands the possibilities of replacing traditional unhairing process for hides, which are highly polluting and toxic, with enzymatic depilation, a significantly eco-friendlier alternative.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and funding acquisition, J.M.M. and M.C.; investigation, J.M.M., L.J.V., E.B. and M.C.; methodology, L.J.V. and E.B.; formal analysis, E.B.; project administration, M.C.; visualization, E.B.; writing—original draft, J.M.M. and L.J.V.; writing—review and editing, J.M.M. and L.J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the Spanish Government through the Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico (CDTI) and by the company Cromogenia Units, S.A. This research was funded for PSEP research group by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through PID2022-140302OB-I00 and by the Generalitat de Catalunya under the project 2021-SGR-01042.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study are deposited in the network of PSEP research group of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC).

Acknowledgments

The GREIA research group would like to thank the Catalan Government for the quality accreditation given to her research group (2021 SGR 01615). GREIA is certified agent TECNIO in the category of technology developers from the Government of Catalonia. The PSEP research group report that this work is part of Maria de Maeztu Units of Excellence Programme CEX2023-001300-M / funded by MCIN/AEI / 10.13039/501100011033.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kandasamy, N.; Velmurugan, P.; Sundarvel, A.; Jonnalagadda Raghava, R.; Bangaru, C.; Palanisamy, T. Eco-benign enzymatic dehairing of goatskins utilizing a protease from a Pseudomonas fluorescens species isolated from fish visceral waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 25, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, G.L.; Tekalign, K.G. Impacts of tannery effluent on environments and human health. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 7, 88–97, ISSN (Paper)2224-3216 ISSN (Online)2225-0948. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, S.; Yadav, A.; Dwivedi, P.D.; Das, M. Toxic hazards of leather industry and technologies to combat threat: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mikula, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Izydorczyk, G.; Kuligowski, K.; Bandrów, P.; Kułażyński, M. Progress in sustainable technologies of leather wastes valorization as solutions for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongsiri, C.; Vollertsen, J.; Hvitved-Jacobsen, T. Effect of temperature on air-water transfer of hydrogen sulfide. J. Environ. Eng. 2004, 130, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Fan, Y. An individual risk assessment framework for high-pressure natural gas wells with hydrogen sulfide, applied to a case study in China. Saf. Sci. 2014, 68, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, J.M.; Bartolí, E.; Cebollada, P.; Cabeza, L.F. ; A bibliometric study of the unhairing and liming of the leather tanning process. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2022, 117, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzet, J.M.; Sabe, R.; Sorolla, S.; Castell, J.C. Dry biomaterIal production from fresh hides and skins. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2010, 105, 376–382. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi, B.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S.; Ali, M.B.; Messaoud, E. B; Naili, B; Dhouib, A.; Bejar, S. Excellent laundry detergent compatibility and high dehairing ability of the Bacillus pumilus CBS alkaline proteinase (SAPB). Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2009, 14, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerouaz, B.; Jaouadi, B.; Brans, A.; Saoudi, B.; Habbeche, A.; Haberra, S.; Belghith, H.; Gargroui, A.; Ladjama, A. Purification and biochemical characterization of two novel extracellular keratinases with feather-degradation and hide-dehairing potential. Process Biochem. 2021, 106, 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Tian, Y. Heterologous expression of alkaline metalloproteinases in Bacillus subtilis SCK6 for eco-friendly enzymatic unhairing of goat skins. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2022, 117, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, C.; Peng, B.; Long, Z. A novel approach for quantitative characterization of hydrolytic action of glycosidases to glycoconjugates in leather manufacturing. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2020, 15, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, D. , Mandal, S., Chellan, R., Chellappa, M. Enzyme-induced changes in skin and its implications. Clean Technol. Envir. 2020, 22, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, R.R.; Ferdes, M.; Ignat, M.; Chelaru, C.; Ciobanu, A.; Drusan, D. Isolation and characterization of bacterial protease enzyme of leather waste. ICAMS 2022 – 9th International Conference on Advanced Materials and Systems, Bucarest, Romania, 26-28 October 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo. R.L.M.S.A.; Yuliatmo, R. Characterization and production optimization of keratinase from three bacillus strains. Leather Footwear J. 2020, 20, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrola, S.M.L.; de Melo, A.C.N.; Mazotto, A.M.; Lins. U.; Rosado, A.S.; Peixoto, R. S.; Vermelho, A.B. Keratinases and sulfide from Bacillus subtilis SLC to recycle feather waste. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 28, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanadan, A.; Kanagaraj, J.; Sunderraj, L.; Govindaraju, R.; Suseela, R.G. Application of alkaline protease in leather processing - an eco-friendly approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.X.; Cheng, J.H.; Su, H.N.; Sun, H.M.; Li, C.Y.; Yang, L.; Shen, Q.T.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.L. Characterization of a new M4 metalloprotease with collagen-swelling ability from marine Vibrio pomeroyi strain 12613. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshome, Z.; Ahmed, F.E.; Tesfaye, T.; Getachew, L.; Wodag, A.F.; Bitew, M. Preparation of sheepskin unhairing extracts from locally available plants: cleaner leather processing. J. Eng. 2022, 6139674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakundi, J.O.; Ombui, J.N.; Wanyonyi, W.C.; Mulaa, F.J. Recovery of industrially useful hair and fat from enzymatic unhairing of goatskins during leather processing. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2022, 117, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, K.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Pei, Y. Efficient and ecological leather processing: replacement of lime and sulphide with dispase assisted by 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2022, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T., Bhattacharjee, T., Nag, P., Ritika, Ghati, A., Kuila, A. Valorization of agro-waste into value added products for sustainable development. Bioresource Technology Reports 2021, 16, 100834. [CrossRef]

- Paesani, C.; Lammers, T.C.G.L.; Sciarini, L.S.; Pérez, G.T.; Fabi, J.P. Effect of chemical, thermal, and enzymatic processing of wheat bran on the solubilization, technological and biological properties of non-starch polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 328, 121747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeorba, T.P.C.; Okeke, E.S.; Mayel, M.H.; Nwuche, C.O.; Ezike, T.C. Recent advances in biotechnological valorization of agro-food wastes (AFW): Optimizing integrated approaches for sustainable biorefinery and circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandrán-Quintana, R.R.; Mercado-Ruiz, J.N.; Mendoza-Wilson, A.M. Wheat bran proteins: A review of their uses and potential. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Islam, M.; Das, R.; Shekhar, S.; Sinha, A.S.K.; Prasad, K. Wheat bran as potential source of dietary fiber: Prospects and challenges. J Food Compost Anal. 2023, 116, 105030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, D. Structure characterization and dye adsorption properties of modified fiber from wheat bran. Molecules 2024, 29, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D. Integrating bran starch hydrolysates with alkaline pretreated soft wheat bran to boost sugar concentration. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 302, 122826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremikael, M.T.; Ranasinghe, A.; Hosseini, P.S.; Laboan, B.; Sonneveld, E.; Pipan, M.; Oni, F.E.; Montemurro, F.; Höfte, M.; Sleutel, S.; De Neve, S. How do novel and conventional agri-food wastes, co-products and by products improve soil functions and soil quality? Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, E.; Kontogiannopoulos, K.N.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Mantzouridou, F.T. Feasibility of multi-hydrolytic enzymes production from optimized grape pomace residues and wheat bran mixture using Aspergillus niger in an integrated citric acid-enzymes production process. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 309, 123317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrawy, A.A.; Marey, H.S.; Embaby, A.M. The agro-industrial byproduct wheat bran as an inducer for alkaline protease (ALK-PR23) production by pschyrotolerant Lysinibacillus sphaericus Strain AA6 EMCCN3080. Waste Biomass Valori 2023, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovskis, V.; Plume, I. Suitability of oat bran for methane production. Agron. Res. 2017, 15, 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Tarasiuk, W.; Rózyło, R. Fiber preparation from micronized oat by-products: Antioxidant properties and interactions between bioactive compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliopoulos, C.; Markou, G.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Haroutounian, S.A.; Arapoglou, D. Transformation of mixtures of olive mill stone waste and oat bran or Lathyrus clymenum pericarps into high added value products using solid state fermentation. Waste Manag. 2022, 149, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scheme 1.

Breaking of the disulfide bonds of keratin in the hair.

Scheme 1.

Breaking of the disulfide bonds of keratin in the hair.

Figure 1.

pH variation over time as a function of maceration temperature for the wheat bran.

Figure 1.

pH variation over time as a function of maceration temperature for the wheat bran.

Figure 2.

pH variation of the aqueous extract of wheat bran over time of the macerate as a function of its initial pH. Letters A to G correspond to the initially adjusted pH: 6, 8,10,10.5, 11, 11.5 and 12.

Figure 2.

pH variation of the aqueous extract of wheat bran over time of the macerate as a function of its initial pH. Letters A to G correspond to the initially adjusted pH: 6, 8,10,10.5, 11, 11.5 and 12.

Figure 3.

Test procedures to verify the depilatory activity of the extracts. The dashed box shows the common part for both procedures.

Figure 3.

Test procedures to verify the depilatory activity of the extracts. The dashed box shows the common part for both procedures.

Figure 4.

Optical microscopy images of the hide grain with the extracts before and after dialysis. Control, hide maintained in PBS (a). Oat extract before (b) and after dialysis (c). Wheat extract before (d) and after dialysis (e). Images of the left column at low magnification (30x) and on the right at high magnification (60X).

Figure 4.

Optical microscopy images of the hide grain with the extracts before and after dialysis. Control, hide maintained in PBS (a). Oat extract before (b) and after dialysis (c). Wheat extract before (d) and after dialysis (e). Images of the left column at low magnification (30x) and on the right at high magnification (60X).

Figure 6.

Extracts of oat and wheat bran stabilized at different temperatures for 1 hour.

Figure 6.

Extracts of oat and wheat bran stabilized at different temperatures for 1 hour.

Figure 7.

Depilatory activity of extracts treated at different temperatures. Images at lower (30x) and higher magnifications (x60) depict skin samples treated with oat bran (a-e) and wheat bran (f-j) extracts. Thermal treatment for 1 hour at 37 °C (a, f), 40 °C (b, g), 50 °C (c, h), 70 °C (d, i), and 120 °C (e, j).

Figure 7.

Depilatory activity of extracts treated at different temperatures. Images at lower (30x) and higher magnifications (x60) depict skin samples treated with oat bran (a-e) and wheat bran (f-j) extracts. Thermal treatment for 1 hour at 37 °C (a, f), 40 °C (b, g), 50 °C (c, h), 70 °C (d, i), and 120 °C (e, j).

Figure 8.

Dialyzed extracts adjusted to acidic, neutral, and alkaline pH.

Figure 8.

Dialyzed extracts adjusted to acidic, neutral, and alkaline pH.

Figure 9.

Depilatory activity of oat bran and wheat bran extracts with pH adjusted to 3, 7, and 12.

Figure 9.

Depilatory activity of oat bran and wheat bran extracts with pH adjusted to 3, 7, and 12.

Figure 10.

Depilatory activity of the conditioned media from strains isolated from oat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the conditioned media from bacterial strains OB-11 to OB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 10.

Depilatory activity of the conditioned media from strains isolated from oat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the conditioned media from bacterial strains OB-11 to OB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 11.

Depilatory activity of the bacterial extract from strains isolated from oat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the bacterial extracts from strains OB-11 to OB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 11.

Depilatory activity of the bacterial extract from strains isolated from oat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the bacterial extracts from strains OB-11 to OB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 12.

Depilatory activity of the conditioned media from strains isolated from wheat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the conditioned media from bacterial strains WB-11 to WB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 12.

Depilatory activity of the conditioned media from strains isolated from wheat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the conditioned media from bacterial strains WB-11 to WB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 13.

Depilatory activity of the bacterial extract from strains isolated from wheat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the bacterial extracts from strains WB-11 to WB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 13.

Depilatory activity of the bacterial extract from strains isolated from wheat bran extract. Optical microscopy images at lower (30x) and higher magnification (60x) of the bacterial extracts from strains WB-11 to WB-20 (a-j, respectively).

Figure 14.

Morphology particles of the oat bran (a) and wheat bran (b).

Figure 14.

Morphology particles of the oat bran (a) and wheat bran (b).

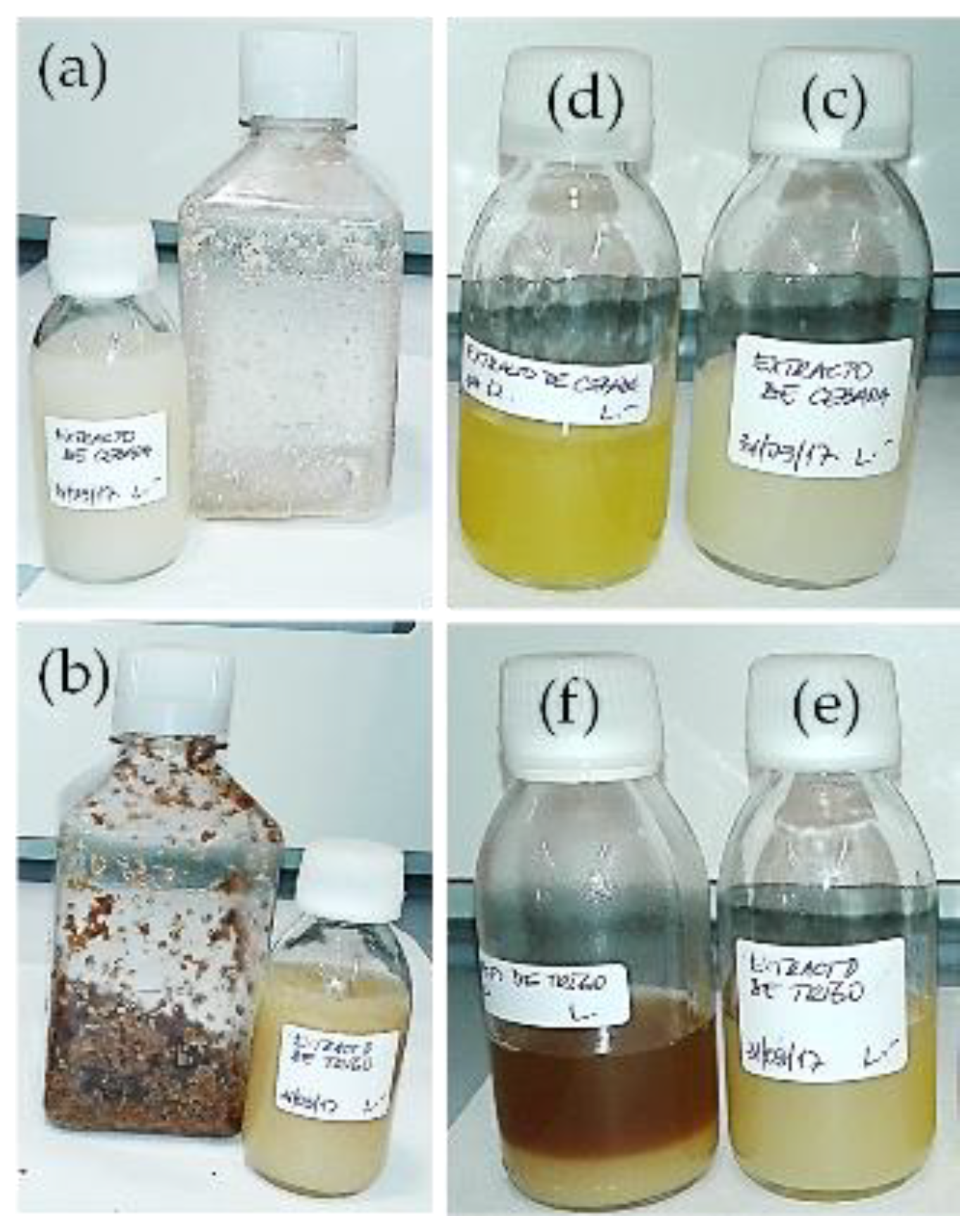

Figure 15.

Preparation of extracts from oat bran (a) and wheat bran (b). The pH of the initial extracts (c and e) was adjusted to pH 12 using NaOH, during the adjustment and after resting, color change of the extract and sediment formation can be observed (d and f).

Figure 15.

Preparation of extracts from oat bran (a) and wheat bran (b). The pH of the initial extracts (c and e) was adjusted to pH 12 using NaOH, during the adjustment and after resting, color change of the extract and sediment formation can be observed (d and f).

Table 1.

pH and conductivity of the extracts before and after dialysis. Oat bran (OB), wheat bran (WB), phosphate buffer saline (PBS).

Table 1.

pH and conductivity of the extracts before and after dialysis. Oat bran (OB), wheat bran (WB), phosphate buffer saline (PBS).

| Extract |

pH |

Conductivity

(mS) |

pH readjusted1

|

| Initial OB |

12.41 |

9.300 |

--- |

| Dialyzed OB |

8.57 |

0.375 |

12.23 |

| Initial WB |

12.25 |

9.300 |

--- |

| Dialyzed WB |

8.40 |

0.246 |

12.24 |

| Initial Water |

6.50 |

0.001 |

--- |

| Post-dialysis Water |

7.50 |

0.038 |

--- |

| PBS+azide |

11.26 |

9.400 |

--- |

Table 2.

pH and conductivity of the extracts before and after dialysis. Oat bran (OB), wheat bran (WB).

Table 2.

pH and conductivity of the extracts before and after dialysis. Oat bran (OB), wheat bran (WB).

| |

mg/mL |

% |

| Initial OB |

22.46 ± 0.47 |

100.00 |

| Dialyzed OB |

18.14 ± 0.22 |

80.78 |

| Initial WB |

12.42 ± 0.69 |

100.00 |

| Dialyzed WB |

7.88 ± 0.79 |

63.42 |

Table 3.

Protein concentration, pH, and conductivity of extracts treated at different temperatures.

Table 3.

Protein concentration, pH, and conductivity of extracts treated at different temperatures.

| |

Oat bran |

Wheat bran |

| Temp. |

Proteins |

pH |

Conduc. |

Proteins |

pH |

Conduc. |

| (°C) |

(mg/mL) |

(%) |

|

(mS) |

(mg/mL) |

(%) |

|

(mS) |

| 37 |

22.5 ± 1.3 |

100.00 |

12.29 |

11.4 |

12.3 ± 0.4 |

100.00 |

12.00 |

12.0 |

| 40 |

22.8 ± 0.3 |

101.25 |

12.19 |

11.5 |

12.9 ± 0.2 |

105.34 |

11.98 |

12.0 |

| 50 |

22.0 ± 0.6 |

97.59 |

12.09 |

11.2 |

13.4 ± 0.0 |

108.75 |

11.90 |

11.8 |

| 70 |

21.7 ± 0.1 |

96.35 |

12.25 |

14.4 |

12.1 ± 1.2 |

98.30 |

11.80 |

13.5 |

| 120 |

23.3 ± 0.7 |

103.35 |

10.04 |

28.1 |

10.2 ± 0.4 |

83.18 |

11.80 |

18.5 |

Table 4.

Characteristics of the extracts adjusted to acidic, neutral, and alkaline pH before dialysis.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the extracts adjusted to acidic, neutral, and alkaline pH before dialysis.

| |

Oat bran |

Wheat bran |

| pH1

|

Proteins |

pH2

|

Conduc. |

Proteins |

pH2

|

Conduc. |

| |

(mg/mL) |

(%) |

|

(mS) |

(mg/mL) |

(%) |

|

(mS) |

| 3 |

1.65 |

7.35 |

4.84 |

1.39 |

1.68 |

13.53 |

4.61 |

0.95 |

| 7 |

16.90 |

75.24 |

7.35 |

1.07 |

9.02 |

72.62 |

6.3 |

0.84 |

| 12 |

20.14 |

89.67 |

12.12 |

8.3 |

7.71 |

62.10 |

12.25 |

3.84 |

Table 5.

Qualitative determination of the depilatory activity of the bacterial strains. (+++ = high; ++ = medium; + = low activity; - = no activity; nd = not determined).

Table 5.

Qualitative determination of the depilatory activity of the bacterial strains. (+++ = high; ++ = medium; + = low activity; - = no activity; nd = not determined).

| Strain |

Bacterial extract |

Conditioned

medium |

Strain |

Bacterial

extract |

Conditioned

medium |

| OB-1 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-1 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-2 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-2 |

nd |

+ |

| OB-3 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-3 |

nd |

+ |

| OB-4 |

nd |

++ |

WB-4 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-5 |

nd |

- |

WB-5 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-6 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-6 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-7 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-7 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-8 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-8 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-9 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-9 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-10 |

nd |

+++ |

WB-10 |

nd |

+++ |

| OB-11 |

+++ |

+++ |

WB-11 |

+++ |

+++ |

| OB-12 |

+++ |

+ |

WB-12 |

+++ |

+ |

| OB-13 |

+++ |

+ |

WB-13 |

+++ |

+++ |

| OB-14 |

+++ |

- |

WB-14 |

+++ |

+ |

| OB-15 |

+++ |

- |

WB-15 |

++ |

- |

| OB-16 |

+++ |

- |

WB-16 |

+++ |

+ |

| OB-17 |

+++ |

+++ |

WB-17 |

++ |

+++ |

| OB-18 |

+++ |

+++ |

WB-18 |

+++ |

+++ |

| OB-19 |

+++ |

+++ |

WB-19 |

+++ |

+++ |

| OB-20 |

+++ |

+++ |

WB-20 |

+++ |

+++ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).