Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Properties of Nanocelullose-Based Hydrogels and Hydrogel-Mucin Systems

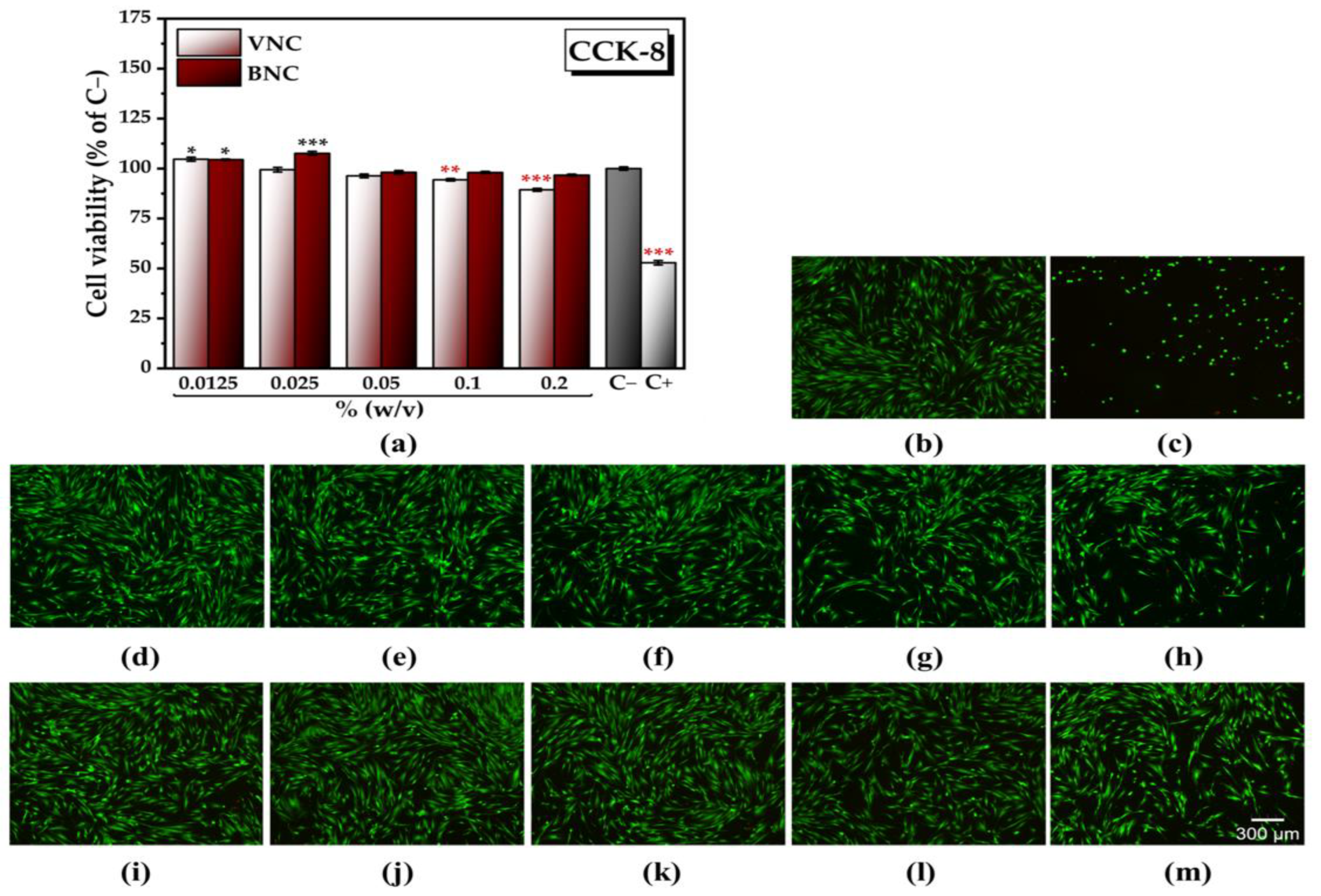

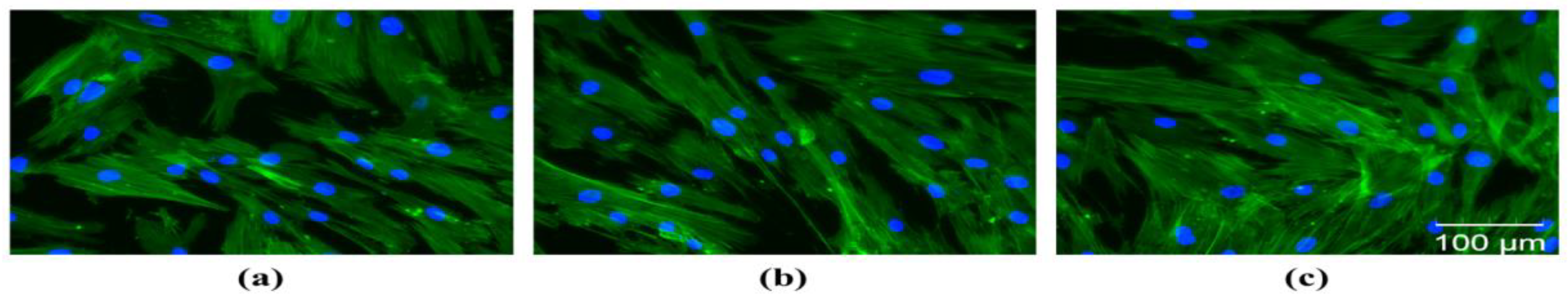

2.2. The Cytocompatible Behaviour of Nanocellulose-Based Hydrogels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Production of Bacterial Cellulose

4.3. Production of Bacterial and Vegetal Cellulose Nanofibers

4.4. Preparation of VNC- / BNC Hydrogels, and Hydrogel-Mucin Systems

4.4. Physico-Chemical Characterization of the VNC / BNC Hydrogels and Investigation of the Hydrogel-Mucin Interaction

4.4.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

4.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

4.4.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

4.4.4. Interfacial Tension and Contact Angle Assessment

4.4.5. Investigation of Mucin Binding Efficiency by Periodic ACID SCHIFf (PAS) Assay

4.4.6. Rheological Analysis

4.5. Cytocompatibility Analysis of VNC and BNC

4.5.1. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and LIVE/DEAD Assays

4.5.2. Investigation of Cell Morphology

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scrivener, C.A.; Schantz, C.W. Penicillin: New Methods for its Use in Dentistry. The Journal of the American Dental Association 1947, 35, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.D. The basics and underlying mechanisms of mucoadhesion. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1556–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grondin, J.A.; Kwon, Y.H.; Far, P.M.; Haq, S.; Khan, W.I. Mucins in Intestinal Mucosal Defense and Inflammation: Learning From Clinical and Experimental Studies. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, D.; Ravindra, N.M. Transdermal drug delivery and patches—An overview. Medical Devices & Sensors 2020, 3, e10069. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, R.; Tevatia, S.; Rath, A.; Behl, A.; Modgil, V.; Sharma, N. Mucoadhesive Systems in Dentistry: A Review. Indian Journal of Dental Research 2016, 4, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar, S.; Malviya, R.; Prajapati, B.G.; Puri, D.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Sriamornsak, P. Recent advances in biopolymer-based mucoadhesive drug delivery systems for oral application. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 91, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pal, K.; Anis, A.; Pramanik, K.; Prabhakar, B. Polymers in Mucoadhesive Drug-Delivery Systems: A Brief Note. Designed Monomers and Polymers 2009, 12, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, G.; Rossi, S.; Ferrari, F.; Bonferoni, M.C.; Caramella, C.M. Mucoadhesive Polymers as Enabling Excipients for Oral Mucosal Drug Delivery. In Oral Mucosal Drug Delivery and Therapy, Rathbone, M.J., Senel, S., Pather, I., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 53–88. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Döring, A.; Persson, S. The cell biology of cellulose synthesis. Annual review of plant biology 2014, 65, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaramudu, T.; Ko, H.-U.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, E.S.; Kim, J. Adhesion properties of poly (ethylene oxide)-lignin blend for nanocellulose composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2019, 156, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontturi, K.S.; Biegaj, K.; Mautner, A.; Woodward, R.T.; Wilson, B.P.; Johansson, L.-S.; Lee, K.-Y.; Heng, J.Y.; Bismarck, A.; Kontturi, E. Noncovalent surface modification of cellulose nanopapers by adsorption of polymers from aprotic solvents. Langmuir 2017, 33, 5707–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, J.A.Á.; Hoyos, C.G.; Arroyo, S.; Cerrutti, P.; Foresti, M.L. Acetylation of bacterial cellulose catalyzed by citric acid: Use of reaction conditions for tailoring the esterification extent. Carbohydrate polymers 2016, 153, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Sabu, A.; Tiwari, S. Materials chemistry and the futurist eco-friendly applications of nanocellulose: status and prospect. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2018, 22, 949–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Marra, K.G. Injectable, biodegradable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Materials 2010, 3, 1746–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Cheng, W.; Fan, H.; Pei, G. Reconstruction of goat tibial defects using an injectable tricalcium phosphate/chitosan in combination with autologous platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3201–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ji, Q.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Q.; Deng, P.; Hu, F.; Yang, J. Accelerated bony defect healing based on chitosan thermosensitive hydrogel scaffolds embedded with chitosan nanoparticles for the delivery of BMP2 plasmid DNA. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A 2017, 105, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimardani, Y.; Mirzakhani, E.; Ansari, F.; Pourjafar, H.; Sadeghi, N. Prospective and applications of bacterial nanocellulose in dentistry. Cellulose 2024, 31, 7819–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revin, V.V.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Parchaykina, M.V.; Kuzmenko, T.P.; Kurgaeva, I.V.; Revin, V.D.; Ullah, M.W. Bacterial Cellulose-Based Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horue, M.; Silva, J.M.; Berti, I.R.; Brandão, L.R.; Barud, H.D.S.; Castro, G.R. Bacterial Cellulose-Based Materials as Dressings for Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastav, P.; Pramanik, S.; Vaidya, G.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Singh, A.; Abualsoud, B.M.; Amaral, L.S.; Abourehab, M.A.S. Bacterial cellulose as a potential biopolymer in biomedical applications: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10, 3199–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, S.; Janfaza, S.; Tasnim, N.; Gibson, D.L.; Hoorfar, M. Nanomaterial-based encapsulation for controlled gastrointestinal delivery of viable probiotic bacteria. Nanoscale Advances 2021, 3, 2699–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Lalsangi, S.; Santra, S.; Banerjee, R. Nanocellulose as a carrier for improved drug delivery: Progresses and innovation. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 97, 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, A.; Tabuchi, M.; Uo, M.; Tatsumi, H.; Hideshima, K.; Kondo, S.; Sekine, J. Applicability of bacterial cellulose as an alternative to paper points in endodontic treatment. Acta Biomaterialia 2013, 9, 6116–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiros, C.; Christakopoulos, P. Biotechnological potential of brewers spent grain and its recent applications. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabbathi, N.P.P.; Velidandi, A.; Pogula, S.; Gandam, P.K.; Baadhe, R.R.; Sharma, M.; Sirohi, R.; Thakur, V.K.; Gupta, V.K. Brewer's spent grains-based biorefineries: A critical review. Fuel 2022, 317, 123435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S.Z. Microcrystalline cellulose: the inexhaustible treasure for pharmaceutical industry. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res 2017, 4, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Du, J.; Chen, W.; Pan, M.; Chen, D. Preparation and thermostability of cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils from two sources of biomass: rice straw and poplar wood. Cellulose 2019, 26, 8625–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, S.-O.; Panaitescu, D.-M.; Orban, C.; Ghiurea, M.; Doncea, S.-M.; Fierascu, R.C.; Nistor, C.L.; Alexandrescu, E.; Nicolae, C.-A.; Trică, B.; et al. Bacterial Nanocellulose from Side-Streams of Kombucha Beverages Production: Preparation and Physical-Chemical Properties. Polymers 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi Heidari, N.; Fathi, M.; Hamdami, N.; Taheri, H.; Siqueira, G.; Nyström, G. Thermally Insulating Cellulose Nanofiber Aerogels from Brewery Residues. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, 10698–10708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritean, N.; Dimitriu, L.; Dima, Ș.-O.; Ghiurea, M.; Trică, B.; Nicolae, C.-A.; Moraru, I.; Nicolescu, A.; Cimpean, A.; Oancea, F.; et al. Bioactive Hydrogel Formulation Based on Ferulic Acid-Grafted Nano-Chitosan and Bacterial Nanocellulose Enriched with Selenium Nanoparticles from Kombucha Fermentation. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Shatkin, J.A.; Kong, F. Evaluating mucoadhesion properties of three types of nanocellulose in the gastrointestinal tract in vitro and ex vivo. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 210, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrinan, H.J.; Mann, J. Infrared spectra of the crystalline modifications of cellulose. Journal of Polymer Science 1956, 21, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhart, D.L.; Atalla, R.H. Studies of microstructure in native celluloses using solid-state C-13 NMR. Macromolecules 1984, 17, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Persson, J.; Chanzy, H. Combined infrared and electron-diffraction study of the polymorphism of native celluloses. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 2461–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, A.; Dima, Ș.-O.; Tritean, N.; Oprița, E.-I.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Trică, B.; Oancea, A.; Moraru, I.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Oancea, F. Bioactive-Loaded Hydrogels Based on Bacterial Nanocellulose, Chitosan, and Poloxamer for Rebalancing Vaginal Microbiota. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritean, N.; Dima, Ș.-O.; Trică, B.; Stoica, R.; Ghiurea, M.; Moraru, I.; Cimpean, A.; Oancea, F.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D. Selenium-Fortified Kombucha–Pollen Beverage by In Situ Biosynthesized Selenium Nanoparticles with High Biocompatibility and Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgidou, M.; Dimopoulou, M.; Mackie, A.; Rigby, N.; Ritzoulis, C.; Panayiotou, C. Physicochemical aspects of mucosa surface. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 102634–102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Yong, G.; Chia, C.; Man, S.; Subramanian, G.; Oh, G.; Cheong, E.; Kiryukhin, M. Mucin coated protein-polyphenol microcarriers for daidzein delivery. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 2645–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Vikulina, A.; Bowker, L.; Hunt, J.; Loughlin, M.; Puddu, V.; Volodkin, D. Nanoarchitectonics of Bactericidal Coatings Based on CaCO<sub>3</sub>-Nanosilver Hybrids. ACS Applied Biomaterials 2024, 7, 2872–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritean, N.; Dimitriu, L.; Dima, Ș.-O.; Stoica, R.; Trică, B.; Ghiurea, M.; Moraru, I.; Cimpean, A.; Oancea, F.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D. Cytocompatibility, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of a Mucoadhesive Biopolymeric Hydrogel Embedding Selenium Nanoparticles Phytosynthesized by Sea Buckthorn Leaf Extract. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.F.; Donald, A.M. Surface and Interfacial Tension of Cellulose Suspensions. Langmuir 2002, 18, 10155–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, J.D.P.; de Souza, K.C.; Duarte, C.R.; da Silva Duarte, I.; de Assis Sales Ribeiro, F.; Silva, G.S.; de Farias, P.M.A.; Stingl, A.; Costa, A.F.S.; Vinhas, G.M.; et al. Plant and bacterial nanocellulose: production, properties and applications in medicine, food, cosmetics, electronics and engineering. A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020, 18, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazilati, M.; Ingelsten, S.; Wojno, S.; Nypelo, T.; Kadar, R. Thixotropy of cellulose nanocrystal suspensions. J. Rheol. 2021, 65, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, T.; Sahlin, K.; Yao, K.; Geng, S.Y.; Westman, G.; Zhou, Q.; Oksman, K.; Rigdahl, M. Rheological properties of nanocellulose suspensions: effects of fibril/particle dimensions and surface characteristics. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2499–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Rein, D.M.; Ueda, K.; Yamane, C.; Cohen, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation of cellulose-coated oil-in-water emulsions. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2699–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, O.; Hädicke, E.; Koltzenburg, S.; Müller-Plathe, F. Hydrophilicity and Lipophilicity of Cellulose Crystal Surfaces. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2001, 40, 3822–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KocevarNared, J.; Kristl, J.; SmidKorbar, J. Comparative rheological investigation of crude gastric mucin and natural gastric mucus. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, J.P.; Turner, B.S.; Afdhal, N.H.; Ewoldt, R.H.; McKinley, G.H.; Bansil, R.; Erramilli, S. Rheology of gastric mucin exhibits a pH-dependent sol-gel transition. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Chang, C.H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Liao, Y.-P.; Ma, T.; Meng, H.; Xia, T. Nanocellulose Length Determines the Differential Cytotoxic Effects and Inflammatory Responses in Macrophages and Hepatocytes. Small 2021, 17, 2102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhola, G.; Park, S.; Lim, J.-W.; Chivers, C.; Song, Y.H.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-W. Nanomaterial-Based Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review on Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes and Nanocellulose. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2023, 20, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekara, A.S.; Wang, D.; Grady, T.L. A comparison of kombucha SCOBY bacterial cellulose purification methods. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, M.; Allen, A. A Colorimetric Assay for Glycoproteins Based on the Periodic Acid/Schiff Stain. Biochemical Society Transactions 1978, 6, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejjaji, E.; Smith, A.; Morris, G. Evaluation of the mucoadhesive properties of chitosan nanoparticles prepared using different chitosan to tripolyphosphate (CS:TPP) ratios. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Surface tension (mN/m) |

Contact angle/ hydrophilic surface (°) | Contact angle/ hydrophobic surface (°) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNC* | 50.44±0.66, d** |  |

52.70±0.56, d |  |

56.90±0.40, a |  |

| VNCMu | 46.22±0.39, b (8.37±0.78% decrease) |

|

50.90±0.03, c (3.42±0.68% decrease) |

|

58.14±0.41, b (2.18±0.73% increase, a) |

|

| BNC | 55.29±0.29, e |  |

48.27±0.57, b |  |

65.13±0.35, c |  |

| BNCMu | 48.50±0.54, c (12.28±0.97% decrease) |

|

46.53±0.55, a (3.59±1.14% decrease) |

|

68.00±0.26, d (4.40±0.41% increase) |

|

| Mu | 39.33±0.47, a |  |

45.67±0.71, a |  |

78.27±0.45, e |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).