1. Background

Diseases caused by infections pose a serious risk to human health, and prolonged use of antibiotics has contributed to the development of multidrug-resistant bacteria (Srivastava & Kim, 2022; Blair et al., 2015). Current wound dressings may contain glia, which can cause skin irritation or allergic reactions. Additionally, their limited ability to absorb large amounts of exudate can lead to infections or detachment from the wound. As a result, there is an urgent need to develop antibacterial materials to address these issues (Li et al., 2018).

Native to the tropical coastlines and estuaries of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Nypa fruticans Wurmb—widely known as Nipa palm—is prevalent in Southeast Asian regions such as the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Historically, it has played a key role in the Philippine economy, providing essential materials for constructing traditional homes before cement became widespread. Its fronds were used for roof thatching and wall partitioning, whereas its leaflets and midribs were crafted into brooms, baskets, mats, and sunhats. Additionally, the dried parts of the plant served as fuel. Nipa palm sap, which is extracted from its inflorescence stalks, has long been used in Southeast Asia to produce tree sap, sugars, alcohol, and vinegar. Fermented sap, known as “toddy” or “tuba” in the Philippines, is a popular local beverage (Hamilton and Murphy, 1988). The white endosperm of the palm is also consumed as a snack, and various parts are used in traditional medicine, including treatments for ulcers, herpes, headaches, and toothaches.

Furthermore, Nipa palm is also known to have antimicrobial properties that could fight infections when used as a medical treatment. Nipa is a rich source of various biochemical compounds, such as polyphenols, which indicates excellent antibacterial activity. Studies have shown that aqueous and ethanolic extracts from various parts of Nipa palm exhibit good antimicrobial resistance against common pathogens (Ebana et al., 2015).

Interestingly, a study conducted by Radi (2013) on the physicochemical and microbiological changes that occur during fermentation and storage of Nipa sap revealed that various microbial species, including Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, which is a probiotic bacterium known for its health benefits and is commonly used in the food, agriculture, and pharmaceutical industries, are present. Studies from Hill et al. (2018) and Jones (2017) reported various benefits associated with L. paracasei strains, including antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity.

In addition to these uses and benefits, nipa palm has attracted renewed commercial interest because of its high cellulose content, which is a common byproduct after the extraction of nipa palm flesh. Previous studies have reported that different parts of the nipa palm contain 28.9–48.2% α-cellulose, making them suitable raw materials for producing fuels and chemicals (Tamunaidu & Saka, 2011). Therefore, Nipa palm fronds were used for cellulose extraction for the formulation of the hydrogel.

This study aimed to assess the potential of a cellulose-based hydrogel synthesized from Nipa palm fronds loaded with probiotics (ProbioGel) as an antimicrobial agent to prevent infections.

2. Methods

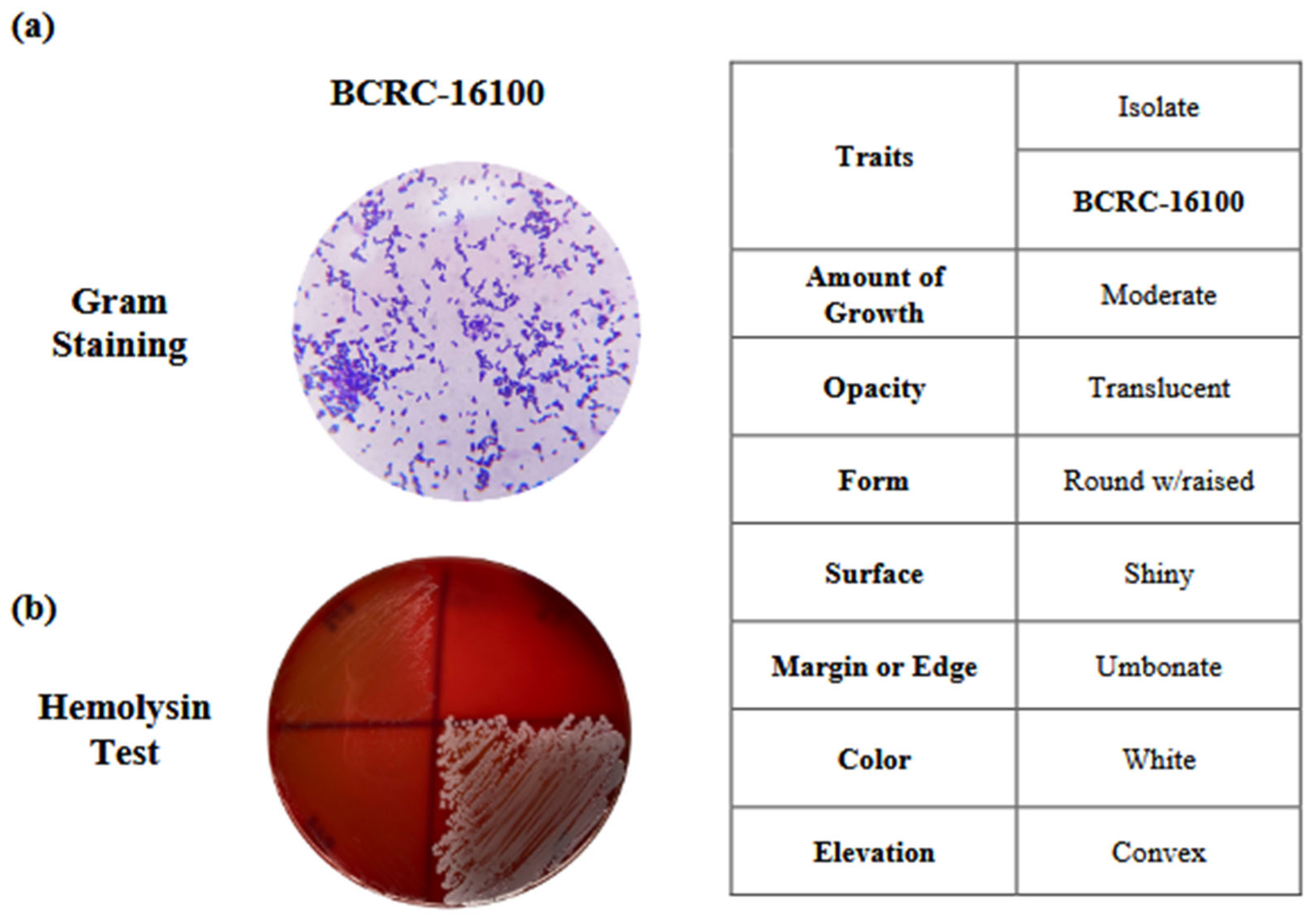

2.1. Phenotypic Characterization of BCRC-16100

Purified Lacticaseibacillus paracasei BCRC-16100 from fermented Nipa sap was subjected to morphological tests by observing its growth on de Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) agar plates and biochemical tests, particularly Gram staining, via Gram’s stain solutions. Furthermore, the potential pathogenicity of the isolate was assessed by examining its hemolytic activity through a hemolysin test via blood agar. The results are categorized into alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ) hemolysis. Alpha hemolysis (α) presents as partial hemolysis with green discoloration around colonies, whereas beta hemolysis (β) manifests as complete lysis, creating a clear zone around colonies that is often associated with pathogenic bacteria (McCaughey, E. J., et al., 2016;). Gamma hemolysis (γ) shows no lysis, indicating nonpathogenicity.

2.2. Genome Sequencing, Promoter Analysis and Production of ProbioGel

The procedures for whole genome sequencing and promoter region analysis were carried out following the methodologies described by Gann, P., et al. (2024), which include the preparation of sequencing libraries, quality assessment of reads, assembly, annotation, and the identification of regulatory elements such as promoter motifs.

Identification of the Isolate by Capillary Sequencing. Genomic DNA from L. paracasei BCRC-16100 was extracted using the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA). PCR amplicons were purified with AMPure XP beads (Cat. No. 163881) and checked on a 1% agarose gel at 120 V for 45 minutes using an Invitrogen 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder.Capillary sequencing was performed using the ABI BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Kit (Cat. No. 4337455), with cycling conditions of 25 cycles at 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 62°C for 4 min. Products were cleaned by ethanol precipitation and analyzed using an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer with POP7 Polymer (Cat. No. 4393714). Base calling was done using Sequencing Analysis Software v5.4.

Whole Genome Sequencing. Genomic libraries were prepared using the TruSeq DNA Nano Kit (Illumina, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina MiSeq platform using a paired-end read format (2 × 150 bp) over 300 cycles at the Philippine Genome Center in Quezon City, Philippines.

Genome Assembly and Annotation. Raw reads were assessed using FastQC v1.0.0 and trimmed with FastQ Toolkit by removing 15 bp from both ends and filtering out bases with a quality score below 28. Assembly was performed via SPAdes Genome Assembler on BaseSpace Sequence Hub, generating contigs, scaffolds, and total assembly length. Genome annotation was carried out using Prokka v1.1.1, identifying tRNA, rRNA, coding sequences (CDS), and CRISPR elements.

Prediction of Promoter Elements. BPROM and BLAST were utilized to identify promoter regions associated with the expression of antimicrobial-related genes in BCRC-16100. Upstream gene regions obtained from WGS were input into BPROM, which identified candidate promoter elements, including –10 and –35 boxes, their sequence positions, and potential transcription factor associations.

2.3. Cellulose Hydrogel Synthesis from Nipa Frond

The extraction and purification of α-cellulose from Nipa fronds followed the method described by Cariaga et al. (2019), while hydrogel synthesis was carried out using the protocol of Domingo et al. (2022). Additionally, methods for derivatization and probiotic incorporation were based on Castro et al. (2025).

Derivatization of Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) from Cellulose. Nine grams of α-cellulose extracted from nipa fronds were mixed with 30 mL of 40% NaOH and 270 mL of isopropanol. The mixture was stirred and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 minutes. Subsequently, 10.8 g of sodium monochloroacetate was added, and the reaction proceeded at 55°C for 3 hours with constant stirring at 1200 rpm using a magnetic hot plate stirrer. The beaker was covered with aluminum foil during this process. Afterward, the mixture was left to settle, and the upper layer was discarded. The remaining sediment was suspended in 70% methanol, neutralized with glacial acetic acid, then filtered. The product was washed five times with 70% ethanol using vacuum filtration, followed by a final rinse with absolute methanol. The resulting CMC was collected and air-dried.

Infusion of Probiotics into the Cellulose Hydrogel. A pure strain of L. paracasei was grown in 250 mL of MRS broth under incubation at 35–37°C for 48 hours. Once turbidity was observed, the hydrogel formulation followed the method of Domingo et al. (2022). A solution of 7% NaOH, 12% urea, and 81% distilled water was prepared and precooled at –12.6°C. One gram of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) was added and stirred at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes, then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a beaker and neutralized with 10% sulfuric acid. CMC solutions were autoclaved, and all materials (glassware and carbomer powder) were sterilized at 160°C for 2 hours and UV-treated for 30 minutes. In sterile conditions, 50 mL of the CMC solution was placed on a magnetic stirrer, and carbomer powder was gradually added until a smooth, homogeneous gel formed. Triethanolamine was added to initiate gelation, followed by the inoculation of 50 mL of L. paracasei-containing MRS broth. The resulting hydrogel was transferred into sterile petri dishes and stored at 4°C.

2.4. Microbiological Assay Using the Kirby-Bauer Method

The antimicrobial potency of the nipa hydrogel loaded with probiotics and their components was tested against the three most common pathogenic bacteria that proliferate in wounds and are the primary causes of delayed healing and infection: Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus. epidermidis. Moreover, these compounds have also been tested against Candida albicans, a fungus that is frequently found in wounds and can lead to complications in healing. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei was subjected to antibacterial and antifungal assays via Mueller‒Hinton agar and potato dextrose agar, respectively. Both agar types were autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes. After cooling, the agar was poured into sterile Petri dishes at depths ranging from 4–5 mm and allowed to solidify before use.

Preparation of Inocula. The S. aureus, E. coli, S. epidermidis, and C. albicans inocula were prepared inside a level 2 biosafety cabinet. A sterile wire loop was flamed to achieve sterilization. Using the sterilized wire loop, four or five colonies were taken from a pure bacterial culture of S. aureus. The colonies of S. aureus were then immersed in a test tube with 10 ml of 0.85% saline solution, which was tightly covered. The same procedure was followed for the other microorganisms to be utilized. All test tubes were incubated at 35°C until a turbidity of 0.5 and 1.0 MacFarland standard for bacteria and yeast cultures was achieved. These microorganisms served as the bacterial and fungal inocula throughout the experiment.

Inoculation of Plates and Placement of Antimicrobial Discs. A sterile cotton swab was first dipped into the standardized bacterial suspension, which was subsequently inoculated into the agar by streaking. The plates were rotated by 60°, and the rubbing procedure was repeated three times to ensure an even distribution of the inoculum. The same procedure was used for the antifungal study. A total of 10 plates were used for the antimicrobial study. The filter paper discs were sterilized by placing them inside a beaker, covered with foil, and subjected to autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes. The sterilized paper discs (6 mm long) were soaked in the formulated nipa hydrogel for approximately 24–48 hours. After impregnation, the discs were carefully placed onto the surface of the inoculated and dried agar plates using sterile forceps, ensuring full contact with the medium by gently pressing them down. Each disc was spaced at least 24 mm center-to-center and positioned no closer than 10–15 mm from the edge of the Petri dish. Plates were then incubated in an inverted position at 30°C for 24, 48, or 72 hours to monitor microbial growth.

Measurement of Zones of Inhibition and Interpretation. Following incubation, the diameter of the inhibition zones was measured across the center of each disc using a ruler or digital Vernier caliper. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated based on the criteria by Manurung et al. (2018): zones ≥ 20 mm were classified as strong, 10–20 mm as active, 5–10 mm as moderately active, and ≤ 5 mm or no visible zone as inactive.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Characterization of L. paracasei BCRC-16100

The BCRC-16100 strain isolated from fermented Nipa was subjected to phenotypic and genotypic characterization. The bacterial isolate was gram-positive and bacilli-shaped. Furthermore, its colony morphology has translucent opacity with a shiny surface. It also appeared round with a raised form, umbonate margin, white color, and convex elevation (see

Figure 1).

According to the results of the hemolysin test,

L. paracasei BCRC-16100 exhibited gamma hemolysis (γ), suggesting its nonpathogenic nature in red blood cells (see

Figure 1b). These results align with previous studies reporting gamma-hemolytic behavior in nonpathogenic bacteria, reinforcing the safety of these microorganisms in the context of hemolytic activity (Smith, J. K., & Jones, R. S., 2018; Chen, Y., & Wang, Y., 2020).

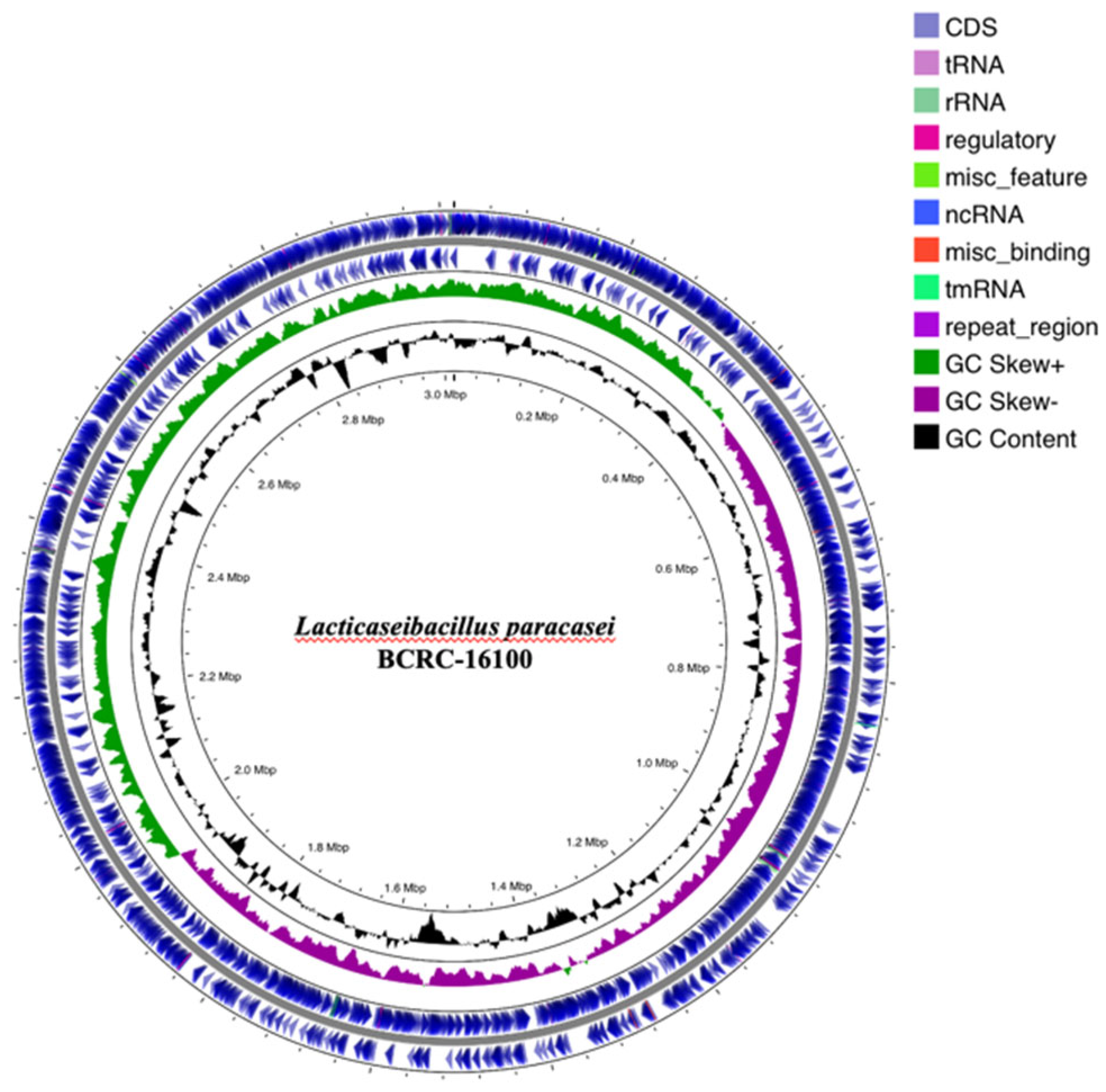

3.2. Genomic Characterization and Analysis of L. paracasei BCRC-16100

The circular genome map of

Lactobacillus paracasei BCRC-16100 provides an overview of its genomic structure (see

Figure 2), highlighting coding sequences (CDS), tRNA, rRNA, regulatory regions, and other miscellaneous features. The CDS regions, shown in blue, encode proteins crucial for the organism’s functionality, while tRNA and rRNA regions (purple and green) are essential for protein synthesis.

Regulatory regions and miscellaneous features play roles in gene expression control. The GC content (black spikes) and GC skew (green and magenta) indicate nucleotide composition bias, providing insights into replication origins, genome stability, and evolutionary adaptation. This genomic organization aids in identifying genes related to stress tolerance, antimicrobial resistance, and metabolic pathways, supporting the organism’s applications in probiotics, functional foods, and biotechnology. By understanding its genome, researchers can explore its potential in areas like fermentation, metabolite production, and genetic engineering.

To validate the integration of the probiotics into the hydrogel system, promoter analysis was carried out to examine the regulatory elements governing the expression of genes related to its antimicrobial function.

The WGS of the probiotic strain L. paracasei BCRC-16100 reveals its potential as an antimicrobial agent, as the genome contains genes for two distinct antimicrobial substances: a Class II Bacteriocin and a Lysozyme M1 precursor.

The acm gene was identified as encoding the lysozyme M1 precursor, which exhibits dual enzymatic activities, including acetylmuramidase (lysozyme) and diacetylmuramidase activities (accession P25310). In addition, lysozyme M1 has a broad-spectrum bacteriolytic activity. It has been known to be particularly effective in lysing bacteria that are typically resistant to other forms of lysozyme, such as certain Streptococcus and Lactobacillus species. The presence of the acm gene likely enhanced the strain’s antagonistic capability by disrupting the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls, which leads to osmotic lysis and cell death (Kiousi et al., 2022). Additionally, the Bacteriocin Class II, with a double-glycine leader peptide encoded by several genes in the strain’s whole-genome sequence (WGS), is a family of bacteriocins known to be secreted by lactic acid bacteria to kill closely related Gram-positive competitors (PFam accession PF10439). Altogether, these compounds help directly inhibit the growth of harmful microbes, contributing to the competitive exclusion of pathogens (Plessas et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Annotated Genes and Proteins of BCRC16100 Involved in Antimicrobial Activity.

Table 1.

Annotated Genes and Proteins of BCRC16100 Involved in Antimicrobial Activity.

| Locus tag |

Protein |

Gene |

Protein ID |

| PROKKA_01359 |

Lysozyme M1 precursor |

acm |

P25310 |

PROKKA_00463

PROKKA_01989

PROKKA_01990 |

Bacteriocin class II with double-glycine leader peptide |

Orf030 |

PF10439.3 |

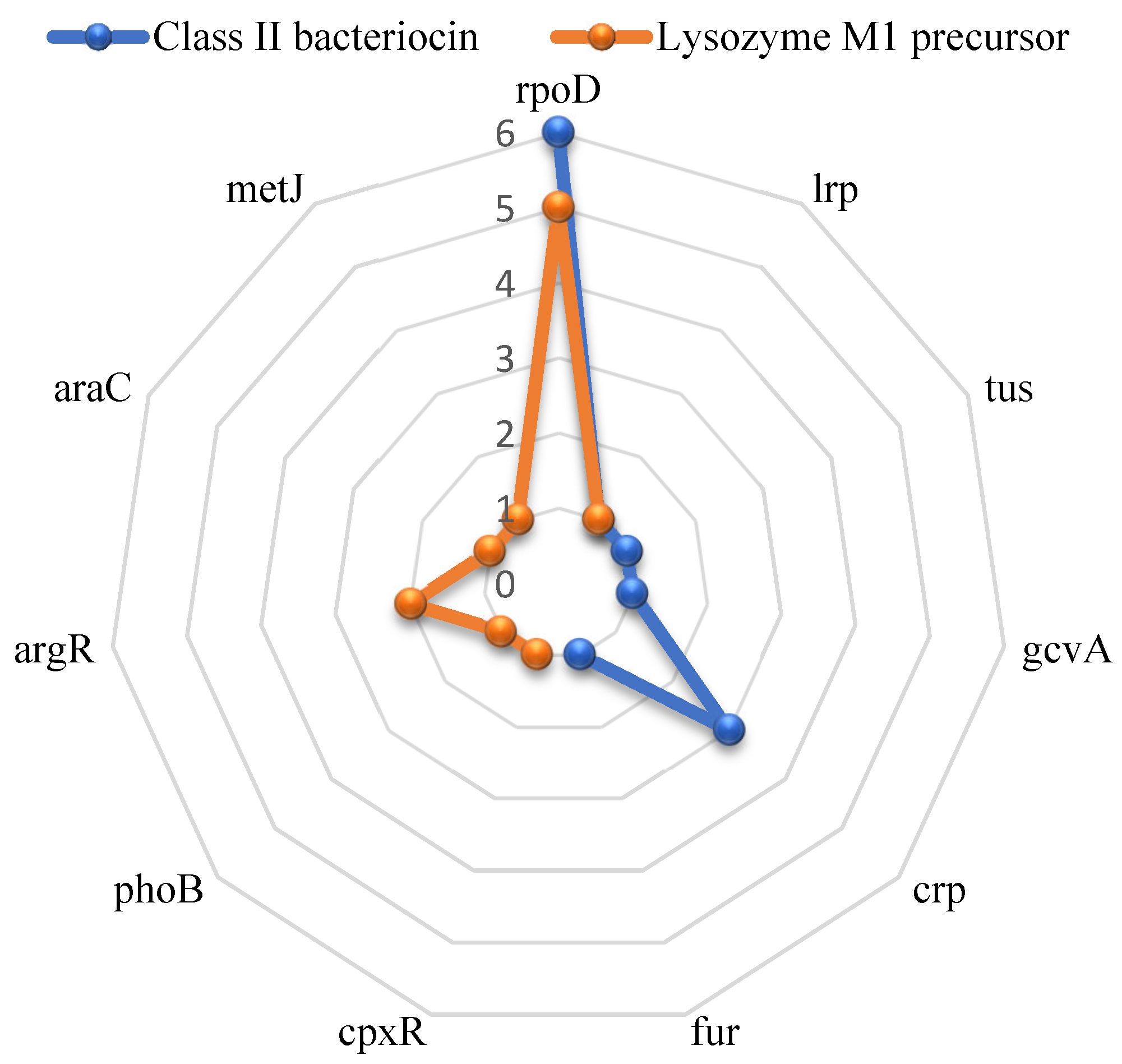

Analysis of the transcription frequencies for these antimicrobial genes identified several regulating transcription factors (see

Figure 3). The

acm gene is associated with six transcription factors (rpoD, lrp, tus, gcvA, crp, and fur), while the bacteriocin gene is linked to seven (rpoD, lrp, cpxR, phoB, argR, araC, and metJ). Common transcription factors for both genes were rpoD and lrp, suggesting their central role in regulating the expression of these antimicrobial compounds in BCRC-16100. Overall, the genetic makeup of

L. paracasei BCRC-16100 indicates its strong therapeutic potential for antimicrobial applications. The identified antimicrobial peptides and enzymes were proven to be crucial in the microbiological assays conducted on the ProbioGel product.

3.3. Microbiological Assay Using the Kirby-Bauer Method

The ProbioGel was subjected to antimicrobial assays against common microorganisms present in mammalian skin, such as

E. coli, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and

C. albicans. After incubation, the resulting inhibition zones (ZOIs) of the ProbioGel were measured (see

Table 2).

The largest inhibition zone of the ProbioGel after 24 hours of observation was against C. albicans, while the smallest ZOI was observed for S. aureus. After 48 hours, all inhibition zones increased significantly, with E. coli having the highest ZOI, followed by S. epidermidis, C. albicans, and S. aureus. The observed increase in the inhibition zones of the ProbioGel against all the bacteria tested after 48 hours also suggests a possible bactericidal effect.

4. Discussion

Phenotypic characterization and genomic analysis combined with antimicrobial assays provide an approach for studying the antimicrobial potency of ProbioGel. Throughout the years, various treatment methods and modalities have been used for treating infections, including antibiotics. However, antibiotics are not 100% effective; therefore, their use is still considered an unmet clinical need.

In the present study, the efficacy of cellulose-based hydrogels from Nipa fronds loaded with probiotics as antimicrobial agents in wound treatment was evaluated. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei BCRC-16100, which was isolated from fermented Nipa sap, was phenotypically characterized via morphological observations and hemolysin tests before identification. L. paracasei displayed gamma hemolysis, suggesting its nonpathogenic activity and increasing its safety. Whole-genome sequencing and analysis of L. paracasei were performed to elucidate its potential beneficial effects.

The antimicrobial properties of the ProbioGel were evaluated via the Kirby–Bauer method against common skin pathogens. The observed increase in inhibition zones against these common pathogens indicates that the ProbioGel exhibited strong antagonistic activity. This is a particularly important trait for antimicrobial agents used in therapeutic applications, as it suggests a lasting impact on microbial populations, reducing the risk of infections.

Furthermore, the inclusion of L. paracasei enhanced its antagonistic activity, as this probiotic naturally stimulates the immune system. Macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells play key roles by exerting direct antifungal effects through phagocytosis and the secretion of antimicrobial peptides. (VazquezMunoz & Dongari-Bagtzoglou, 2021). This is supported by the studies of Rossoni et al. (2017) and Pimentel et al. (2018), where L. paracasei 28.4 upregulated genes that encode the antifungal peptides galiomicin and gallerymicin and negatively regulated the TEC1 and UME6 genes, which are essential to produce hyphae. The results of these two studies revealed a significant decrease in the number of fungal cells. In terms of antibacterial activity, studies have demonstrated L. paracasei’s ability to inhibit pathogens and the formation of biofilms, resulting in greater inhibitory activity against gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus (Shahverdi et al., 2023; Tsai et al., 2021; Brandi et al., 2020). The Lysozyme M1 precursor, encoded by the acm gene, exhibits both lysozyme (acetylmuramidase) and diacetylmuramidase activities. The Class II bacteriocin, associated with Orf030, is a bactericidal peptide secreted by Streptococcal species to target related Gram-positive bacteria. It has a double-glycine leader peptide, lacks the YGNGVXC motif found in pediocin-like bacteriocins, and is co-transcribed with an immunity protein to protect the host. These bacteriocins are typically encoded in operons with regulatory and transport components, and their expression is often plasmid-borne and regulated by a quorum-sensing mechanism.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of ProbioGel as a promising antimicrobial agent. This is reinforced by the identification of genes in probiotic bacteria that encode antimicrobial peptides, including bacteriocin, and enzymes linked to antimicrobial activity, like lysozyme. These findings suggest that ProbioGel could serve as an effective alternative for preventing infections in wounds.

Author Contributions

Abigail S. Castro: Performed the antimicrobial activity and drafted the original manuscript. Alvin G. Domingo: Responsible for conceptualization, methodology, and genome analysis. Jayson F. Cariaga: Handled cellulose extraction and hydrogel production. Francis A. Gamboa: Conducted the isolation and characterization of the bacteria. Aira Nadine Q. Pascua: Involved in data curation and software analysis. Jimmbeth Zenila P. Fabia: Conducted the safety evaluation and microorganism identification. Peter James Icalia Gann: Contributed to investigation, resources, and genome analysis. Shirley C. Agrupis: Provided supervision and acquired funding. The final manuscript has been read and approved for publication by all the authors.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the National Bioenergy Research and Innovation Center and the Commission on Higher Education-Leading the Advancement of Knowledge in Agriculture and Sciences (CHED-LAKAS).

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author will make the datasets generated and/or analyzed in this study available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Philippine Genome Center and the Genomics and Genetic Engineering Laboratory for their support and contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicting interests are stated by the authors.

References

- Brandi, J., Cheri, S., Manfredi, M., Claudia Di Carlo, Virginia Vita Vanella, Federici, F., Cecconi, D. (2020). Exploring the wound healing, anti-inflammatory, antipathogenic and proteomic effects of lactic acid bacteria on keratinocytes. Scientific Reports, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Blair, J. M. A., Webber, M. A., Baylay, A. J., Ogbolu, D. O., & Piddock, L. J. V. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13(1), 42–51. [CrossRef]

- Cariaga, J. F., Domingo, A. G., Santos, B. S., & Agrupis, S. C. (2023). Isolation of a—Cellulose from Nipa (Nypa fruticans Wurmb) Frond using Physico-Chemical Treatment. 16(23), 1754–1759. [CrossRef]

- Castro, A. S., Domingo, A. G., Cariaga, J. F., Gamboa, F. A., Castro, A. C. S., Pascua, A. N. Q., Fabia, J. Z. P., Gann, P. J. I., Santos, B. S., & Agrupis, S. C. (2025). Wound healing efficacy of cellulose hydrogel in ICR mice: A morphoanatomical, histological, and genomic study. The Open Biotechnology Journal, 19, Article e18740707370638. [CrossRef]

- Domingo AG, Cariaga JF, Santos BS, Agrupis SC (2023) Production of Cellulose Hydrogel from Nipa (Nypa fruticans Wurmb) Frond. Indian Journal of Scienceand Technology 16(21): 1-8.

- Ebana, R. U. B., Etok, C. A., & Edet, U. O. (2015). Phytochemical Screening and Antimicrobial Activity of Nypa fruticans Harvested from Oporo River in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 10(4), 1120–1124. http://www.ijias.issrjournals.org/abstract.php?article=IJIAS-14-345-02.

- Gann, P. J., Fabia, J. Z., Pagurayan, A., Agcaoili, M. J. T., Pascual, R., Baranda, S., Racho, A., Olivar, M., Cariaga, J., Domingo, A., Bucao, D., & Agrupis, S. (2024, November). Carbohydrate hydrolytic activity, antimicrobial resistance, and stress tolerance of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei BCRC-16100 and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei ZFM54 for probiotics using genomic and biochemical approaches. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 18(4), Article 53. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L. S., & Murphy, D. H. (1988). Use and management of Nipa palm (Nypa fruticans, arecaceae): a review. Economic Botany, 42(2), 206–213. [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Sugrue, I.; Tobin, C.; Hill, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. The Lactobacillus casei.

-

Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2107.

- Jones, R.M. The Use of Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus paracasei in Clinical Trials for the Improvement of Human Health. In The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology: Implications for Human Health, Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Dysbiosis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 99–108. ISBN 9780128040249.

- Kiousi D., Efstathiou, C., Tegopoulos K., Mantzourani I., Alexopoulos, A., Plessas S., Galanis, A. (2022). Genomic Insight into Lacticaseibacillus paracasei SP5, Reveals Genes and Gene Clusters of Probiotic Interest and Biotechnological Potential. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Dong, S., Xu, W., Tu, S., Yan, L., Zhao, C., Ding, J., & Chen, X. (2018). Antibacterial hydrogels. Advanced Science, 5(5). [CrossRef]

- Manurung, H., Nugroho, R., & Marina, E. (2018). Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Leaves Extract Balangla (Litsea cubeba (Lour) Pers.) from Malinau, East Borneo. Retrieved August 3, 2023, from http://eprints.undip.ac.id/62385/1/04._Hetty_Manurung_et_al.pdf.

- Pimentel, P., Scorzoni, L., Felipe, Ruano, L., Beth Burgwyn Fuchs, Eleftherios Mylonakis, Rodnei Dennis Rossoni. (2018). Lactobacillus paracasei 28.4 reduces in vitro hyphae formation of Candida albicans and prevents the filamentation in an experimental model of Caenorhabditis elegans. Microbial Pathogenesis, 117, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S., Kiousi, D. E., Rathosi, M., Alexopoulos, A., Kourkoutas, Y., Mantzourani, I., et al. (2020). Isolation of a Lactobacillus paracasei strain with probiotic attributes from kefir grains. Biomedicines 8, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES8120594.

- Radi, N. A. (2013, June 1). Physico-chemical and microbiological changes during fermentation and storage of nipa sap (Nypa fruticans wurmb). Psasir.upm.edu.my. http://psasir.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/42828/.

- Rossoni R., Fuchs B., Pimentel, P., Velloso, M., Jorge, A., Junqueira, J., & Mylonakis E. (2017). Lactobacillus paracasei modulates the immune system of Galleria mellonella and protects against Candida albicans infection. PloS One, 12(3), e0173332–e0173332. [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi S., Barzegari A., Bakhshayesh R., & Nami, Y. (2023). In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity of potential probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Heliyon, 9(4), e14641–e14641. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P., & Kim, K. (2022). Membrane Vesicles Derived from Gut Microbiota and Probiotics: Cutting-Edge Therapeutic Approaches for Multidrug-Resistant Superbugs Linked to Neurological Anomalies. Pharmaceutics, 14(11), 2370. [CrossRef]

- Tamunaidu P, Matsui N, Okimori Y, Saka S. (2013). Nipa (Nypa fruticans) sap as a potential feedstock for ethanol production. Biomass Bioenergy 52: 96-102. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H., Chou, C.-H., Huang, T.-Y., Wang, H.-L., Chien, P.-J., Chang, W.-W., & Lee, H.-T. (2021). Heat-Killed Lactobacilli Preparations Promote Healing in the Experimental Cutaneous Wounds. Cells, 10(11), 3264–3264. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Munoz, R., & Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A. (2021). Anticandidal Activities by Lactobacillus Species: An Update on Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Oral Health, 2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).