Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Animals

Cell Cultures

Injection of Tumor Cells and Treatment Protocol

Tumor Growth and Mortality

Cellular Phenotype Determination by Flow Cytometry

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Statistical Analysis

Results

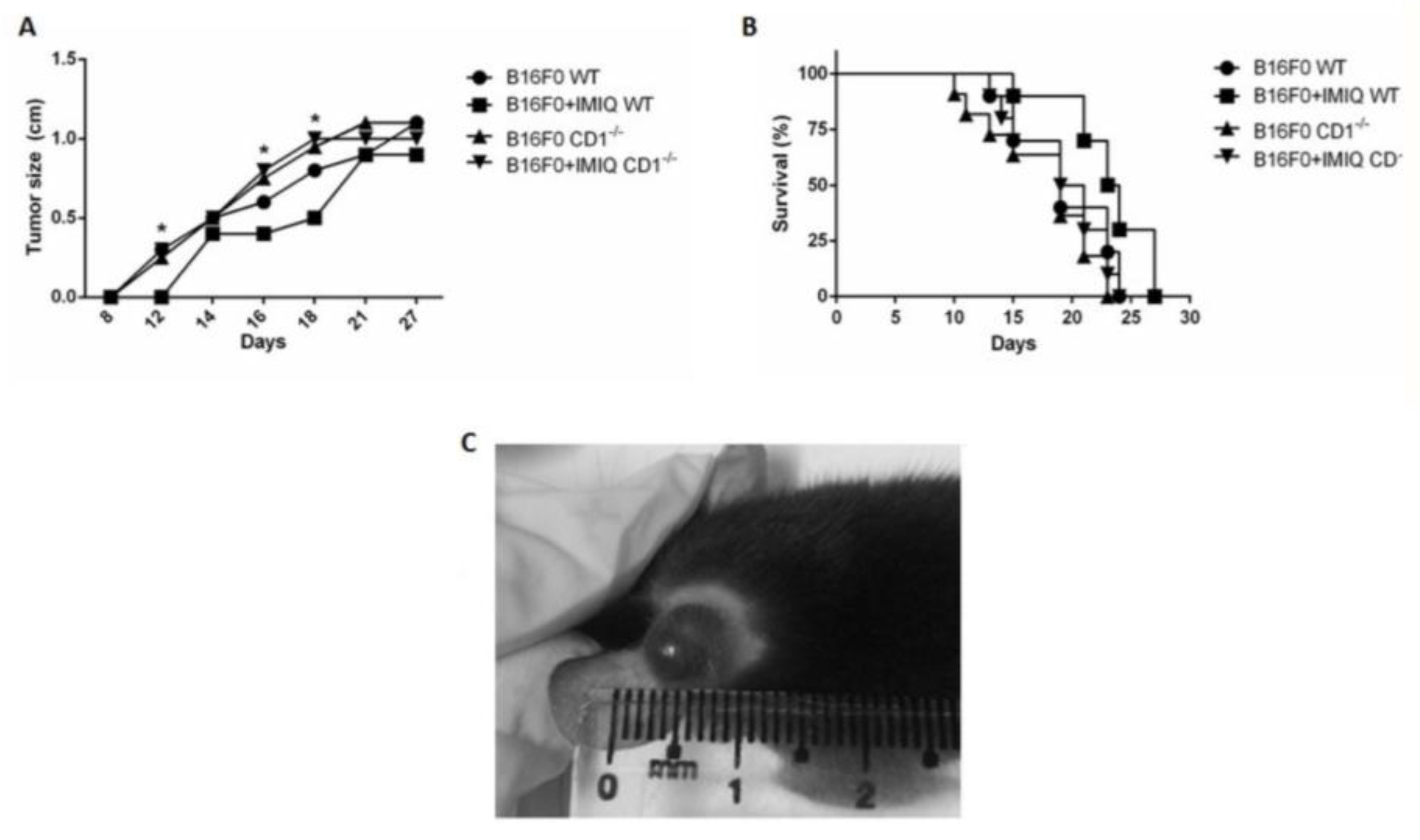

Tumor containment promoted by imiquimod is CD1-dependent.

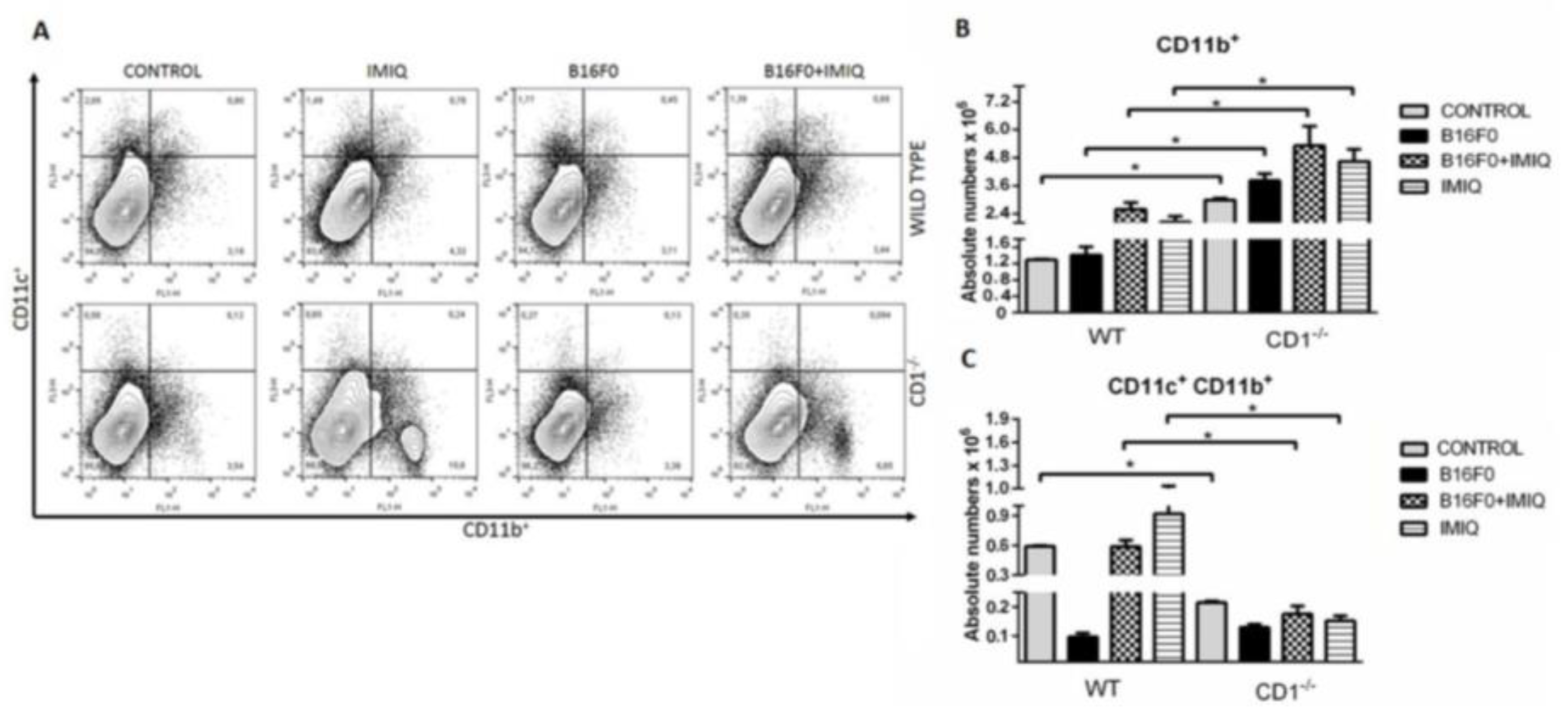

Splenic CD11b+ cells are higher in CD1-/- IMIQ-treated mice, while APCs decrease in almost all CD1-/- mice groups compared to WT mice.

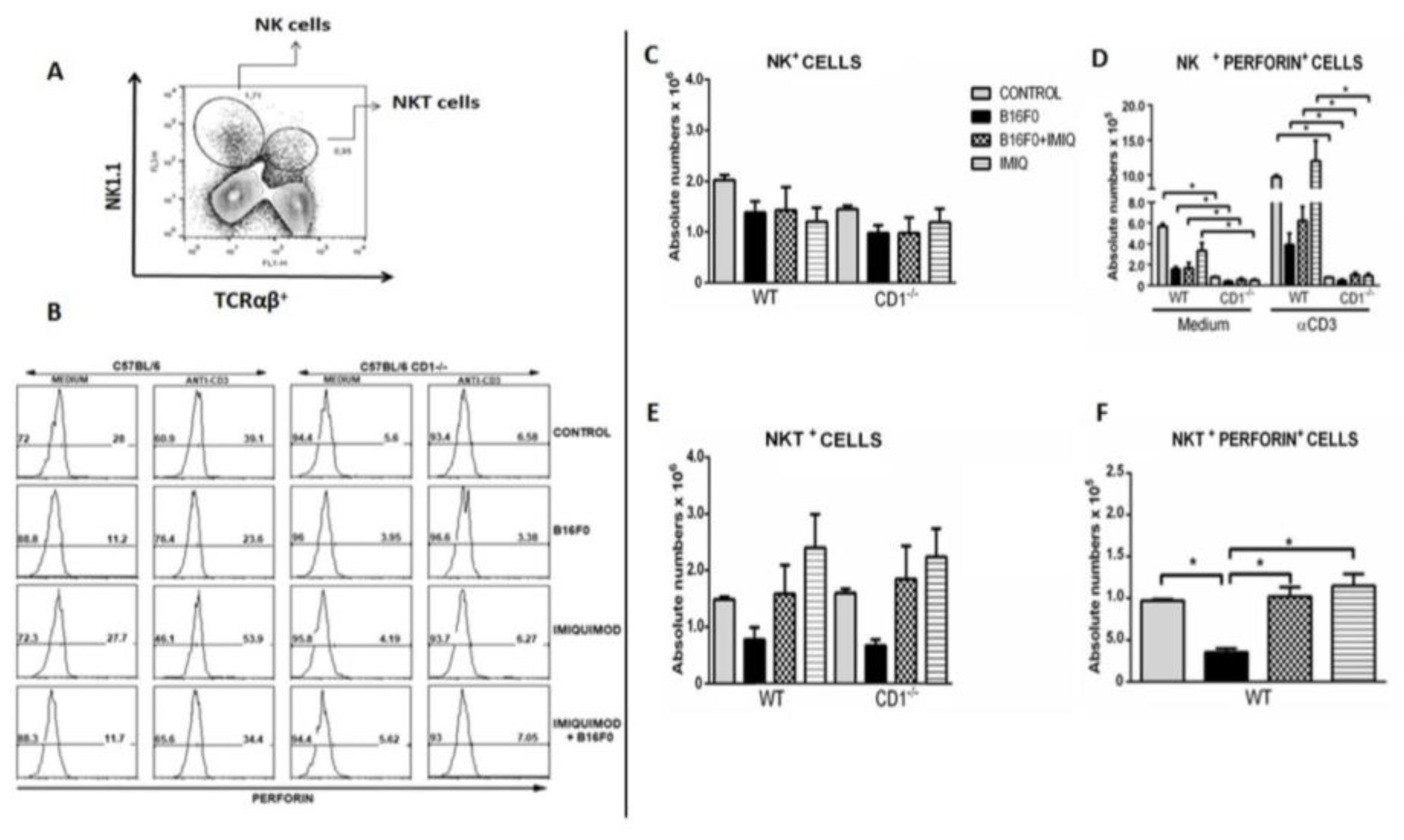

IMIQ induces higher numbers of perforin-producing NK and NKT cells in WT mice but not CD1 knockout mice.

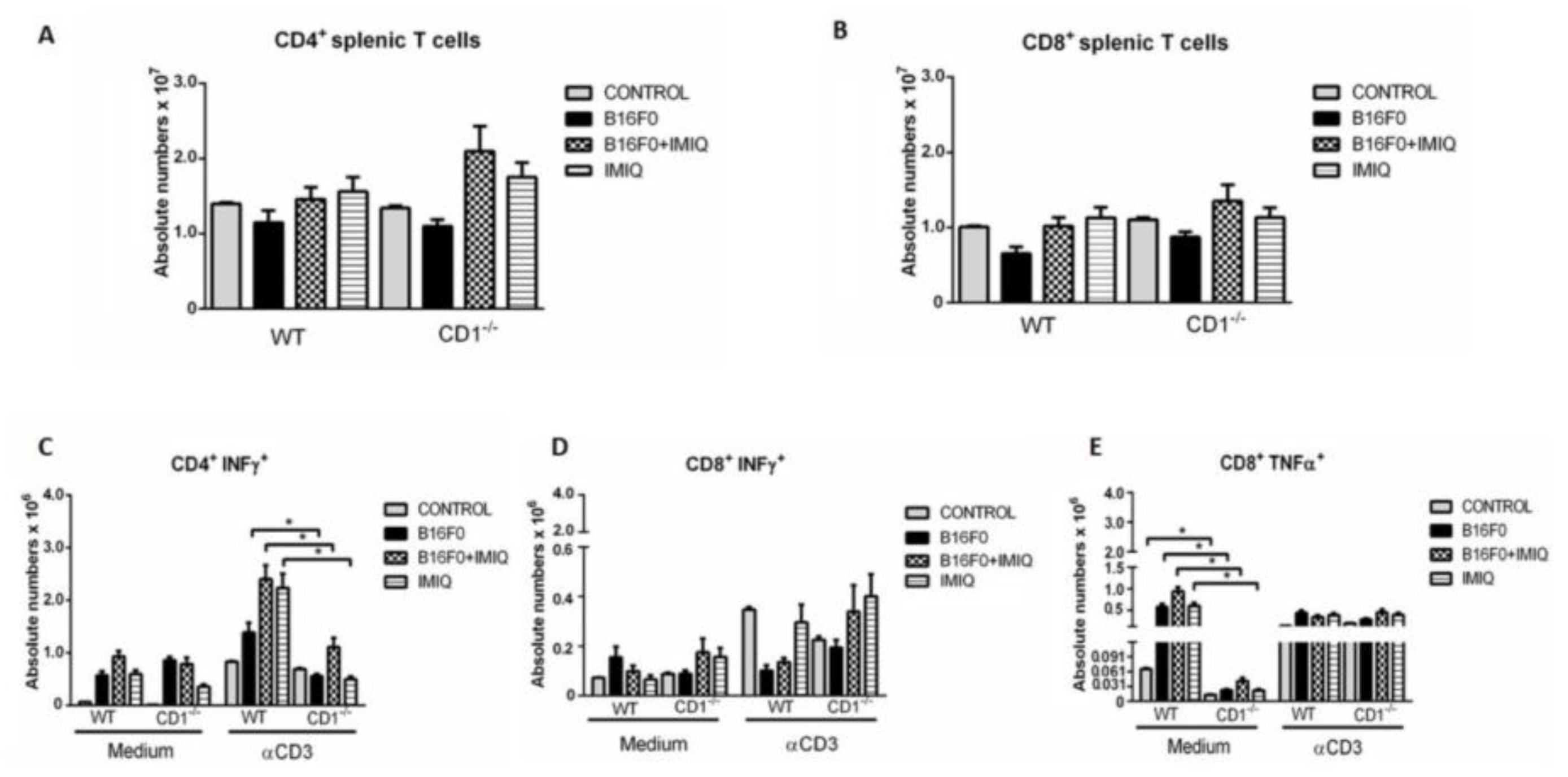

IMIQ treatment increases the production of IFN-γ in CD4 and TNF-α in CD8 in splenic T cells upon anti-CD3 stimulation in vitro.

Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Ambach A, Bonnekoh B, Nguyen M, Schön MP, Gollnick H. Imiquimod, a Toll-like receptor-7 agonist, induces perforin in cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vitro. Mol Immunol. 2004, 40, 1307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, Peng J, Takaku S, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Kumar V, Berzofsky JA. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007, 179, 5126–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antohe M, Nedelcu RI, Nichita L, Popp CG, Cioplea M, Brinzea A, Hodorogea A, Calinescu A, Balaban M, Ion DA, Diaconu C, Bleotu C, Pirici D, Zurac SA, Turcu G. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: The regulator of melanoma evolution. Oncol Lett. 2019, 17, 4155–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry KC, Hsu J, Broz ML, Cueto FJ, Binnewies M, Combes AJ, Nelson AE, Loo K, Kumar R, Rosenblum MD, Alvarado MD, Wolf DM, Bogunovic D, Bhardwaj N, Daud AI, Ha PK, Ryan WR, Pollack JL, Samad B, Asthana S, Chan V, Krummel MF. A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med. 2018, 8, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayatipoor H, Mehdizadeh S, Jafarpour R, Shojae Z, Pashangzadeh S, Motallebnezhad M. Role of NKT cells in cancer immunotherapy- from bench to bed Medical Oncology. 2023, 40, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson RA, Garcon F, Recino A, Ferdinand JR, Clatworthy MR, Waldmann H, Brewer JM, Okkenhaug K, Cooke A, Garside P, Wållberg M. Non-Invasive Multiphoton Imaging of Islets Transplanted Into the Pinna of the NOD Mouse Ear Reveals the Immediate Effect of Anti-CD3 Treatment in Autoimmune Diabetes. Front Immunol. 2018, 18, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, Blees H, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Sammicheli S, Rogers NC, Sahai E, Zelenay S, Reis-Sousa C. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell. 2018, 172, 1022–1037e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo F, Falcão RP, Rossi MA, Mengel J. An age-related gamma delta T cell suppressor activity correlates with the outcome of autoimmunity in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Eur J Immunol. 1993, 23, 2597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo F, Mengel J, Garcia SB, Cunha FQ. Mouse ear spleen grafts: a model for intrasplenic immunization with minute amounts of antigen. J Immunol Methods. 1995, 188, 43–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, Park SH, Beavis A, Koezuka Y, Bendelac A. , Cutting edge: Cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. J Immunol. 1999, 163, 4647–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufait I, Pardo J, Escors D, De Vlaeminck Y, Jiang H, Keyaerts M, De Ridder M, Breckpot K. Perforin and Granzyme B Expressed by Murine Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: A Study on Their Role in Outgrowth of Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobits B, Holcmann M, Amberg N, Swiecki M, Grundtner R, Hammer M, Colonna M, Sibilia M. , 2012. Imiquimod clears tumors in mice independent of adaptive immunity by converting pDCs into tumor-killing effector cells. J Clin Invest. 2012, 122, 575–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med. 2003, 198, 267–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med. 2002, 1‘2a95, 625–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang SJ, Hijnen D, Murphy GF, Kupper TS, Calarese AW, Mollet IG, Schanbacher CF, Miller DM, Schmults CD, Clark RA. Imiquimod enhances IFN-gamma production and effector function of T cells infiltrating human squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2676–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenaka Y, Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Noguchi R, Tsujinoue H, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Imazu H, Masaki T, Fukui H. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in the TIMP-1 transgenic mouse model. Int J Cancer. 2003, 105, 340–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo GC, Peppard JR. Establishment of monoclonal anti-NK-1.1 antibody. Hybridoma. 1984, 3, 301–3. [CrossRef]

- Lindner S, Dahlke K, Sontheimer K, Hagn M, Kaltenmeier C, Barth TFE, Thamara Beyer, Reister F, Fabricius D, Lotfi R, Lunov O, Nienhaus GU, Simmet T, Kreienberg R, Moller P, Schrezenmeier H, Jahrsdorfer B. Induced Granzyme B–Expressing B Cells Infiltrate Tumors and Regulate T Cells. Microenvironment and Immunology. Cancer Res. 2013, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz OC, Gianini RJ, Gonçalves FT, Francisco G, Festa-Neto C, Sanches JA, Gattas GJ, Chammas R, Eluf-Neto J. Ethnicity and cutaneous melanoma in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e36348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson D, Tschopp J. Isolation of a lytic, pore-forming protein (perforin) from cytolytic T-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1985, 260, 9069–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller RL, Gerster JF, Owens ML, Slade HB, Tomai MA. Imiquimod applied topically: a novel immune response modifier and new class of drug. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1999, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins SR, Vasilakos JP, Deschler K, Grigsby I, Gillis P, John J, Elder MJ, Swales J, Timosenko E, Cooper Z, Dovedi SJ, Leishman AJ, Luheshi N, Elvecrog J, Tilahun A, Goodwin R, Herbst R, Tomai MA, Wilkinson RW. Intratumoral immunotherapy with TLR7/8 agonist MEDI9197 modulates the tumor microenvironment leading to enhanced activity when combined with other immunotherapies. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolai CJ, Wolf N, Chang IC, Kirn G, Marcus A, Ndubaku CO, McWhirter SM, Raulet DH. NK cells mediate clearance of CD8+T cell-resistant tumors in response to STING agonists. Sci Immunol. 2009, 5, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien TF, Bao K, Dell’Aringa M, Ang WXG, Abraham S, Reinhardt RL. Cytokine expression by invariant natural killer T cells is tightly regulated throughout development and settings of type-2 inflammation. Mucosal Immunology 2016, 9, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo J, Wallich R, Martin P, Urban C, Rongvaux A, Flavell RA, Müllbacher A, Borner C, Simon MM. Granzyme B-induced cell death exerted by ex vivo CTL: discriminating requirements for cell death and some of its signs. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 567–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker BS, Rautela J, Hertzog PJ. Antitumor actions of interferons: implications for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016, 16, 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potez M, Trappetti V, Bouchet A, Fernandez-Palomo C, Güç E, Kilarski WW, Hlushchuk R, Laissue J, Djonov V. Characterization of a B16-F10 melanoma model locally implanted into the ear pinnae of C57BL/6 mice. Plos One. 2018, 13, e0206693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulet, DH. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003, 3, 781–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandru A, Voinea S, Panaitescu E, Blidaru A. Survival rates of patients with metastatic malignant melanoma. J Med Life. 2014, 7, 572–6. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth MJ, Trapani JA. Granzymes: exogenous proteinases that induce target cell apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1995, 16, 202–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura K, Inaba M, Ogata H, Yasumuzu R, Sardiña EE, Inaba K, Kuma S, Good RA, Ikehara S. Inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by natural suppressor cells present in murine bone marrow. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 2582–6. [Google Scholar]

- Thiem A, Hesbacher S, Kneitz H, di Primio T, Heppt MV, Hermanns HM, Goebeler M, Meierjohann S, Houben R, Schrama D. IFN-gamma-induced PD-L1 expression in melanoma depends on p53 expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga G, Balkow S, Wild MK, Stadtbaeumer A, Krummen M, Rothoeft T, Higuchi T, Beissert S, Wethmar K, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Vestweber D, Grabbe S. Active MAC-1 (CD11b/CD18) on DCs inhibits full T-cell activation. Blood. 2007, 109, 661–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Liu X, Li Z, Chai Y, Jiang Y, Wang Q, Ji Y, Zhu Z, Wan Y, Yuan Z, Chang Z, Zhang M. CD8(+)NKT-like cells regulate the immune response by killing antigen-bearing DCs. Sci Rep. 2015, 15, 14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo EY, Yeh H, Chu CS, Schlienger K, Carroll RG, Riley JL, Kaiser LR, June CH. Cutting edge: Regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2002, 168, 4272–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu D, Gu P, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Chen SH. 2004. NK and CD8+ T cell-mediated eradication of poorly immunogenic B16-F10 melanoma by the combined action of IL-12 gene therapy and 4-1BB costimulation. Int J Cancer. 2004, 109, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5þ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity 2008, 28, 639–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanaba K, Kamata M, Ishiura N, Shibata S, Asano Y, Tada Y, Sugaya M, Kadono T, Tedder TF, Shinichi SJ. Regulatory B cells suppress imiquimod-induced, psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Leukoc Biol. 2013, 94, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao B. G.,Vasilakos J.P., Tross D., Smirnov D., Klinman D.M. Combination therapy targeting toll-like receptors 7, 8 and 9 eliminates large established tumors. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2014, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).