1. Introduction

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), remarkable carbon allotropes, are celebrated for their unique cylindrical structure formed by rolling a single graphene sheet into a seamless tubular configuration. Among these, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) have garnered significant attention since their discovery by Iijima in 1991 [

1]. The nanoscale diameter and structural precision of SWNTs endow them with extraordinary properties, including high electrical conductivity, tensile strength, and mechanical flexibility. These properties are intricately linked to their chirality, defined by the chiral indices (

n,

m), which determine their electronic nature. Depending on the chiral angle, SWNTs can exhibit either metallic or semiconducting behavior. Specifically, SWNTs with (

n −

m) mod 3 = 0 are metallic, while other configurations display semiconducting characteristics [

2,

3]. This dichotomy in electronic properties underscores the need for precise separation of SWNTs, as their mixed synthesis often hinders their direct application in advanced electronic devices, such as transistors, sensors, and energy storage systems [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The bandgap in semiconducting SWNTs varies with chirality, underscoring the importance of precise separation methods that enable targeted use in electronic devices. However, achieving separation by chirality remains a significant technical hurdle, as the controlled growth of SWNTs with predefined electronic properties is not yet viable. Consequently, a range of separation methods—including gel chromatography, density gradient centrifugation, and electrophoresis—have been developed to address this issue, with gel chromatography emerging as a particularly promising method for large-scale, chirality-specific separation.

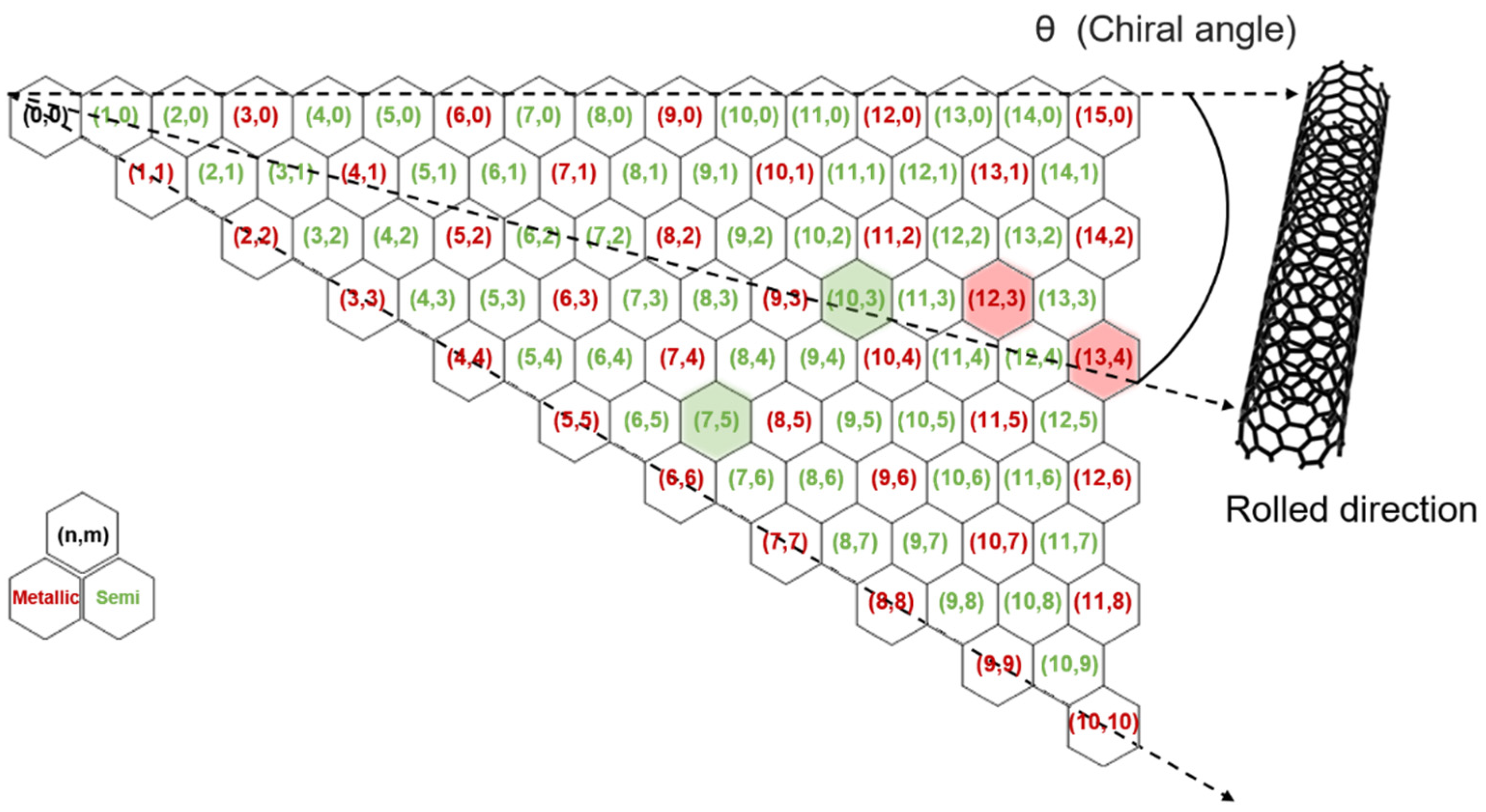

Figure 1.

Map illustrating the structural and electronic characteristics of SWNTs based on their chirality. The hexagonal lattice defines the relationship between chiral indices (

n,

m), chiral angle (

θ), and rolled direction, which collectively determine whether a given SWNT is metallic (red) or semiconducting (green). Four specific chiralities—(13,4), (12,3), (10,3), and (7,5)—are highlighted and correspond to distinct peaks in the Raman spectra shown in

Figure 5. These chiralities are used to analyze the relative intensity ratios and provide insight into the selective separation of metallic- and semiconducting-enriched SWNTs.

Figure 1.

Map illustrating the structural and electronic characteristics of SWNTs based on their chirality. The hexagonal lattice defines the relationship between chiral indices (

n,

m), chiral angle (

θ), and rolled direction, which collectively determine whether a given SWNT is metallic (red) or semiconducting (green). Four specific chiralities—(13,4), (12,3), (10,3), and (7,5)—are highlighted and correspond to distinct peaks in the Raman spectra shown in

Figure 5. These chiralities are used to analyze the relative intensity ratios and provide insight into the selective separation of metallic- and semiconducting-enriched SWNTs.

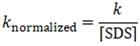

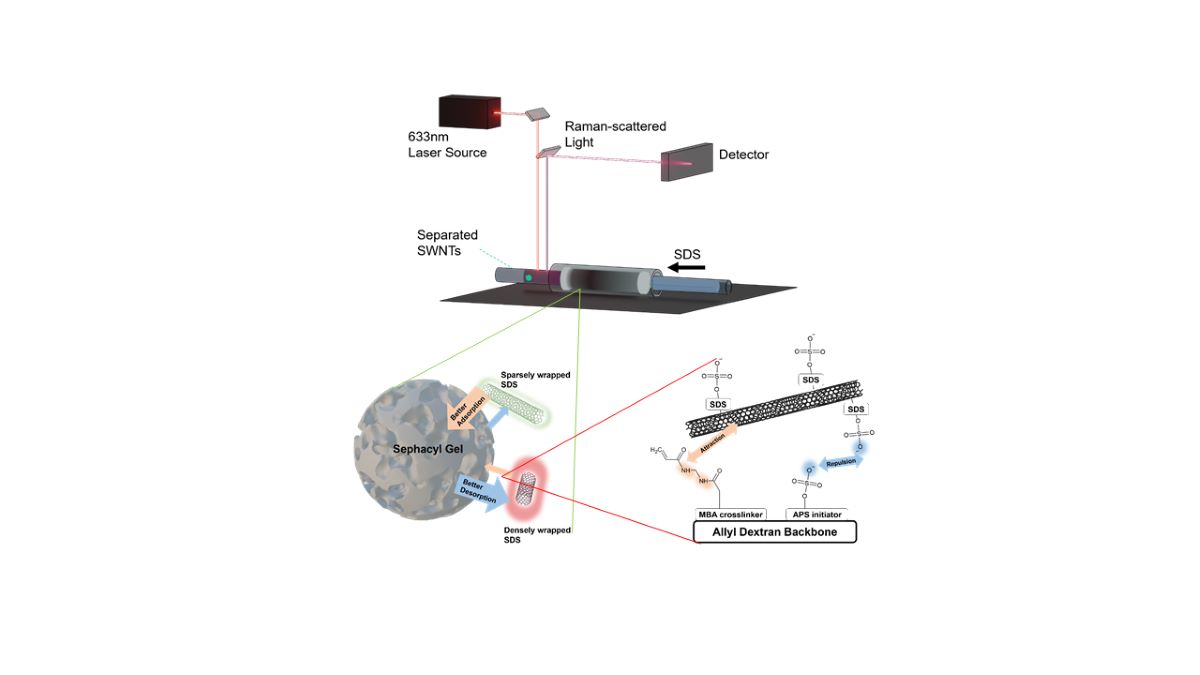

Gel chromatography is based on the adsorption and desorption of SWNTs with different affinities to the gel matrix, depending on their electrical properties. Agarose or dextran-based hydrogels used in gel chromatography exhibit varying affinities for SWNTs depending on their electrical characteristics, enabling selective adsorption of SWNTs with distinct properties [

10,

11]. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), a common dispersant for SWNTs, facilitates the desorption of nanotubes from the gel depending on its concentration and the degree of dispersion. This chemical adsorption and desorption mechanism, involving both the gel and dispersant, enables the selective separation of SWNTs with specific structures and electrical properties [

12]. In particular, gel chromatography is a suitable method for separating metallic and semiconducting SWNTs, as these two types can be effectively segregated by adjusting the amount of SDS [

13]. The ability to achieve separation through controlling concentrations of chemical agents makes gel chromatography advantageous for large-scale separation processes. However, despite its proven efficacy for large-scale applications, the detailed interaction mechanisms within the gel matrix remain poorly understood, posing challenges for optimization and extending its utility to microscale precision.

While much research has focused on large-scale separation techniques suitable for commercial production, small-scale methods are equally vital. Microscale separation provides an opportunity to observe SWNTs dynamics with greater precision, uncovering intricate molecular interactions and enabling real-time monitoring of separation processes. Additionally, micro-sized columns allow for both qualitative and quantitative analyses of SWNTs behavior via spectroscopic methods, which is invaluable for refining separation techniques and advancing toward scalable industrial applications. In the present study, we introduce a novel micro-sized polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) column-based gel chromatography system designed to investigate the separation dynamics of SWNTs at a microscopic scale. PDMS, known for its transparency and ease of patterning, is an ideal material for constructing microfluidic channels that simulate the chromatographic environment [

14,

15]. This study pioneers the integration of gel chromatography within PDMS-based microfluidic channels, combining the precision of microscale separation with real-time, in-situ Raman spectroscopic analysis. This approach not only facilitates the isolation of metallic and semiconducting SWNTs but also reveals their elution kinetics and purity with unprecedented clarity. By systematically isolating and analyzing SWNT fractions, this work provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between SDS concentration, flow dynamics, and electronic-type separation. Furthermore, the integration of in-situ Raman spectroscopy allows for dynamic tracking of G-band characteristics and G

-/G

+ intensity ratios, offering quantitative insights into the separation process. This study demonstrates that metallic SWNTs exhibit accelerated separation dynamics compared to semiconducting SWNTs, a distinction further emphasized when normalized for SDS concentration. The results establish this PDMS-based platform as a versatile tool for both fundamental research and scalable industrial applications, bridging the gap between the demands of large-scale separations and the precision required for nanoscale studies.

3. Results and Discussion

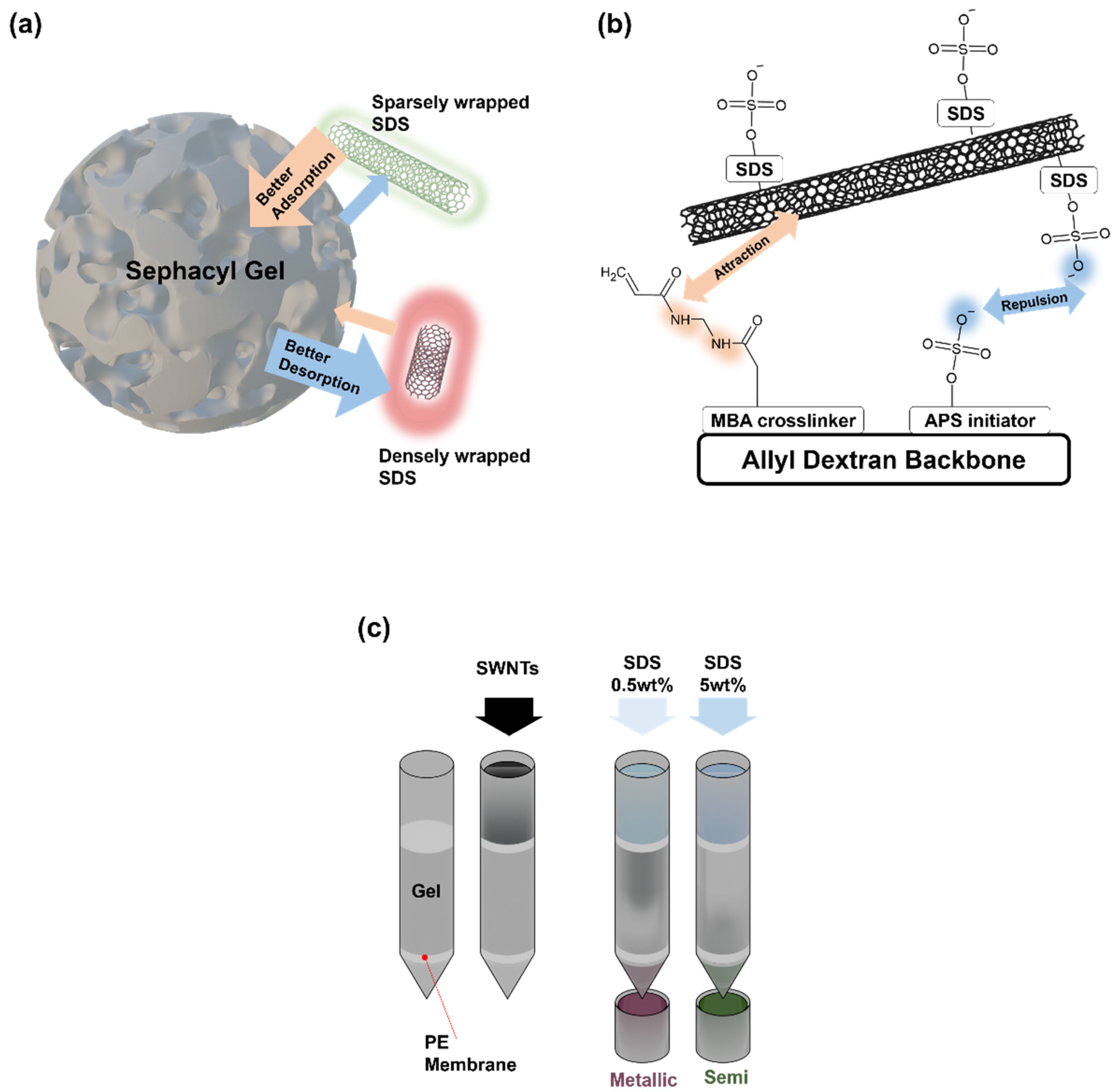

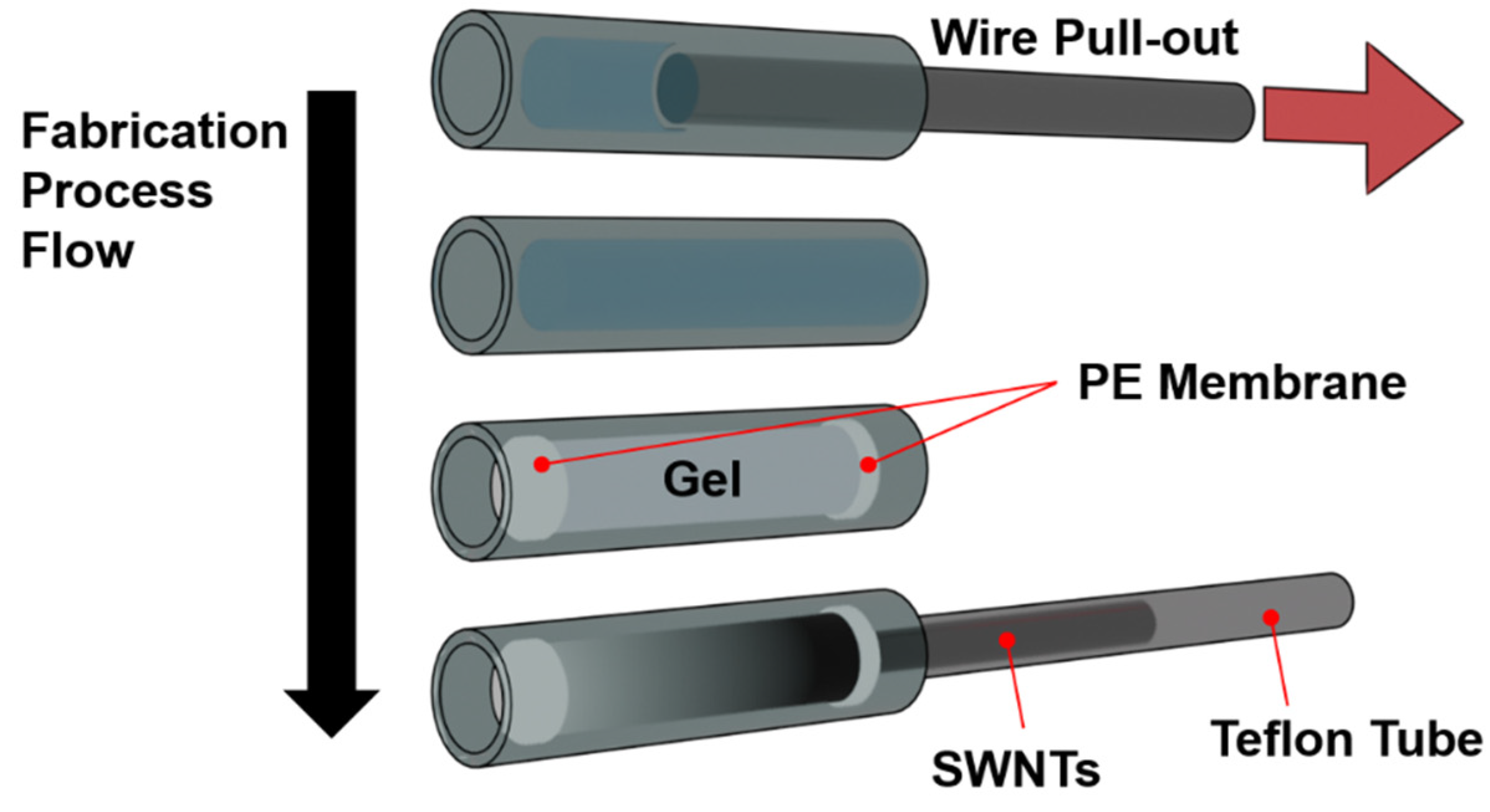

The efficient separation of metallic and semiconducting SWNTs was achieved using a PDMS-based microfluidic gel chromatography column, as depicted in

Figure 4a. The process involved injecting sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at two distinct concentrations: 0.5 wt% SDS for metallic SWNTs and 5 wt% SDS for semiconducting SWNTs. This approach capitalized on the differential interactions between SWNTs and the gel matrix, driven by the variation in repulsion forces mediated by SDS concentration. The stepwise elution enabled clear differentiation between metallic and semiconducting SWNT fractions. The visual contrast between the separated fractions was striking, as shown in

Figure 4b. Metallic SWNTs, characterized by their weaker interactions with SDS, exhibited a reddish appearance, whereas semiconducting SWNTs, with stronger gel affinities, displayed a greenish color. This color distinction underscores the precision of the separation method and aligns with the inherent optical properties of HiPco SWNTs. The reddish tint of metallic SWNTs and the greenish tint of semiconducting SWNTs were consistent with prior observations, reaffirming the effectiveness of SDS-mediated chromatographic separation [

19].

Post-separation analysis of the SWNT fractions was conducted using in-situ Raman spectroscopy, as shown in

Figure 4c, to precisely determine their electronic structure. The method leveraged the radial breathing mode (RBM) vibrations in the range of 100–300 cm⁻¹, which are highly sensitive to the diameter and electronic properties of SWNTs. RBM peaks below 250 cm⁻¹ were attributed to metallic SWNTs, while those above this threshold corresponded to semiconducting SWNTs, providing a clear distinction between the two types. To avoid laser-induced disruptions such as heating or photon-induced energy effects, the Raman measurements were performed on SWNT fractions flowing through a Teflon tube connected to the microfluidic column. This approach reinforced the reliability of the microfluidic gel chromatography system in achieving efficient separation and accurate electronic characterization, offering significant insights into SWNT properties for advanced nanomaterial analysis.

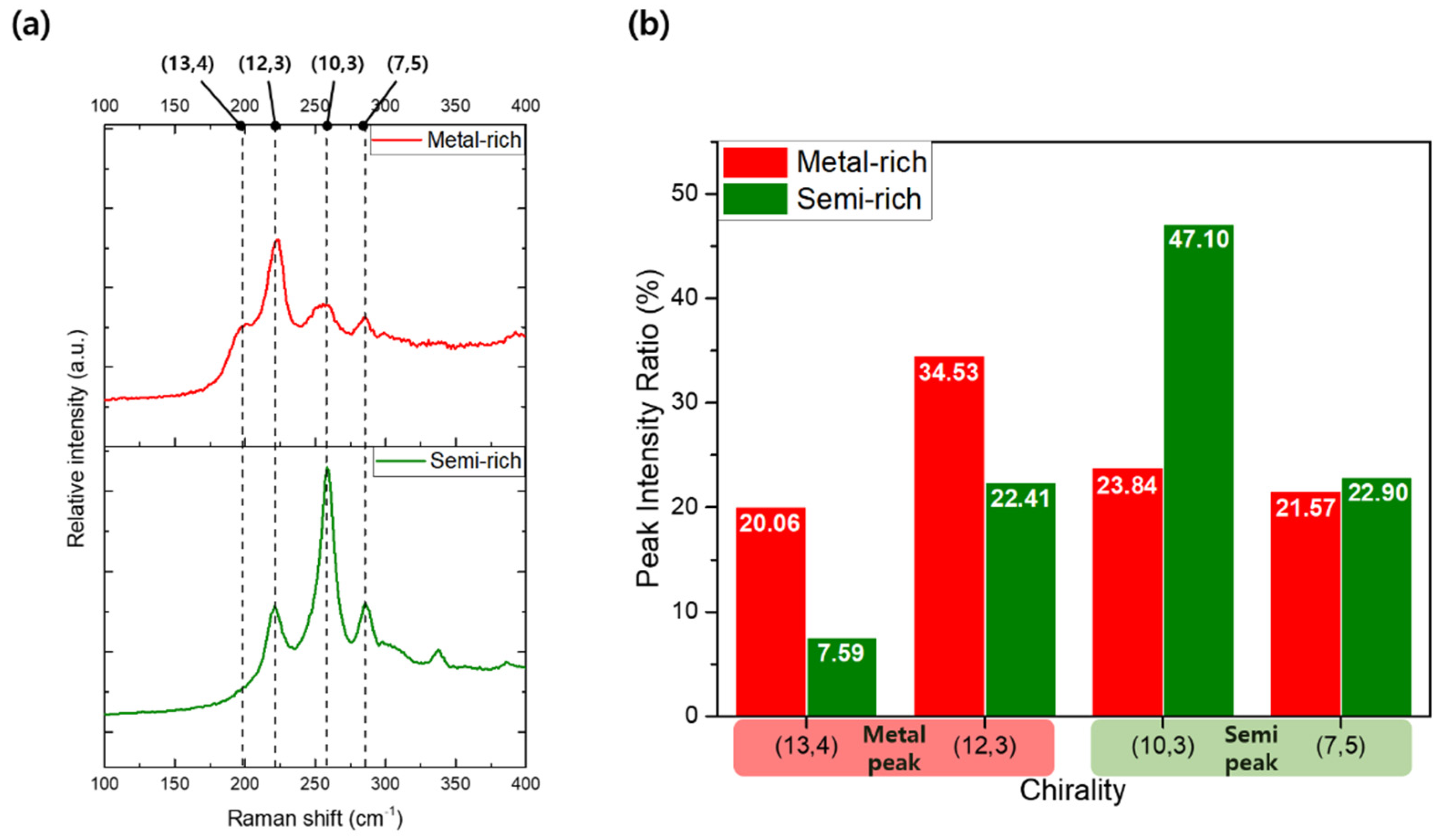

Figure 5a presents the Raman spectra of the metallic-enriched (reddish) and semiconducting-enriched (greenish) samples, highlighting significant differences in the four primary peaks: 197 cm⁻¹ for metallic (13,4), 217 cm⁻¹ for metallic (12,3), 255 cm⁻¹ for semiconducting (10,3), and 284 cm⁻¹ for semiconducting (7,5). The distinct RBM peaks observed for these chiralities confirm the successful separation, as the metallic and semiconducting SWNTs exhibit characteristic vibrational modes corresponding to their respective structural configurations. The intensity and position of these peaks provide insight into the composition and purity of the separated samples, with metallic SWNTs showing more prominent low-frequency RBM peaks compared to their semiconducting counterparts. In the metal-rich sample, the (12,3) metallic peak was particularly prominent, indicating a higher concentration of metallic SWNTs with this specific chirality. In contrast, the semi-rich sample exhibited distinct peaks for (10,3) and (7,5) semiconducting SWNTs, with only minor contributions from the (12,3) metallic SWNTs. This suggests that the separation process was effective in enriching the sample with semiconducting SWNTs while significantly reducing the presence of metallic SWNTs, thereby demonstrating the efficacy of the PDMS microchannel-based gel chromatography in achieving selective separation based on electronic properties.

Figure 5.

(a) Raman spectra in the radial breathing mode (RBM) region for metallic-rich (top) and semiconducting-rich (bottom) SWNT samples, highlighting four distinct chirality peaks: (13,4), (12,3), (10,3), and (7,5). The vertical dashed lines indicate the Raman shifts corresponding to these chiralities. (b) Relative peak intensity ratios (%) for the four chiralities, comparing metallic-rich and semiconducting-rich fractions. The differences in intensity ratios demonstrate the effectiveness of the separation process in enriching SWNTs based on their electronic type.

Figure 5.

(a) Raman spectra in the radial breathing mode (RBM) region for metallic-rich (top) and semiconducting-rich (bottom) SWNT samples, highlighting four distinct chirality peaks: (13,4), (12,3), (10,3), and (7,5). The vertical dashed lines indicate the Raman shifts corresponding to these chiralities. (b) Relative peak intensity ratios (%) for the four chiralities, comparing metallic-rich and semiconducting-rich fractions. The differences in intensity ratios demonstrate the effectiveness of the separation process in enriching SWNTs based on their electronic type.

Figure 5b provides a comprehensive comparison of the relative ratios of the four major Raman peaks between the metallic-enriched and semiconducting-enriched SWNT samples. Peaks associated with metallic chiralities, specifically (13,4) and (12,3) SWNTs, were more prominent in the metallic-rich samples. Conversely, peaks linked to semiconducting chiralities, such as (10,3) and (7,5) SWNTs, exhibited higher relative intensities in the semiconducting-enriched samples. Notably, while the (7,5) peak in semiconducting-enriched samples was only marginally more intense than in metallic-enriched samples, the (10,3) peak showed a substantial increase in intensity, underscoring the selective enrichment of semiconducting SWNTs. Through analysis of the RBM region, these measurements confirm that the separation process effectively altered the relative proportions of metallic and semiconducting SWNTs across the different sample fractions. The observed shift in peak ratios across separated samples highlights the capacity of this micro-sized PDMS column-based gel chromatography system to achieve selective isolation based on SWNT chirality and electronic properties.

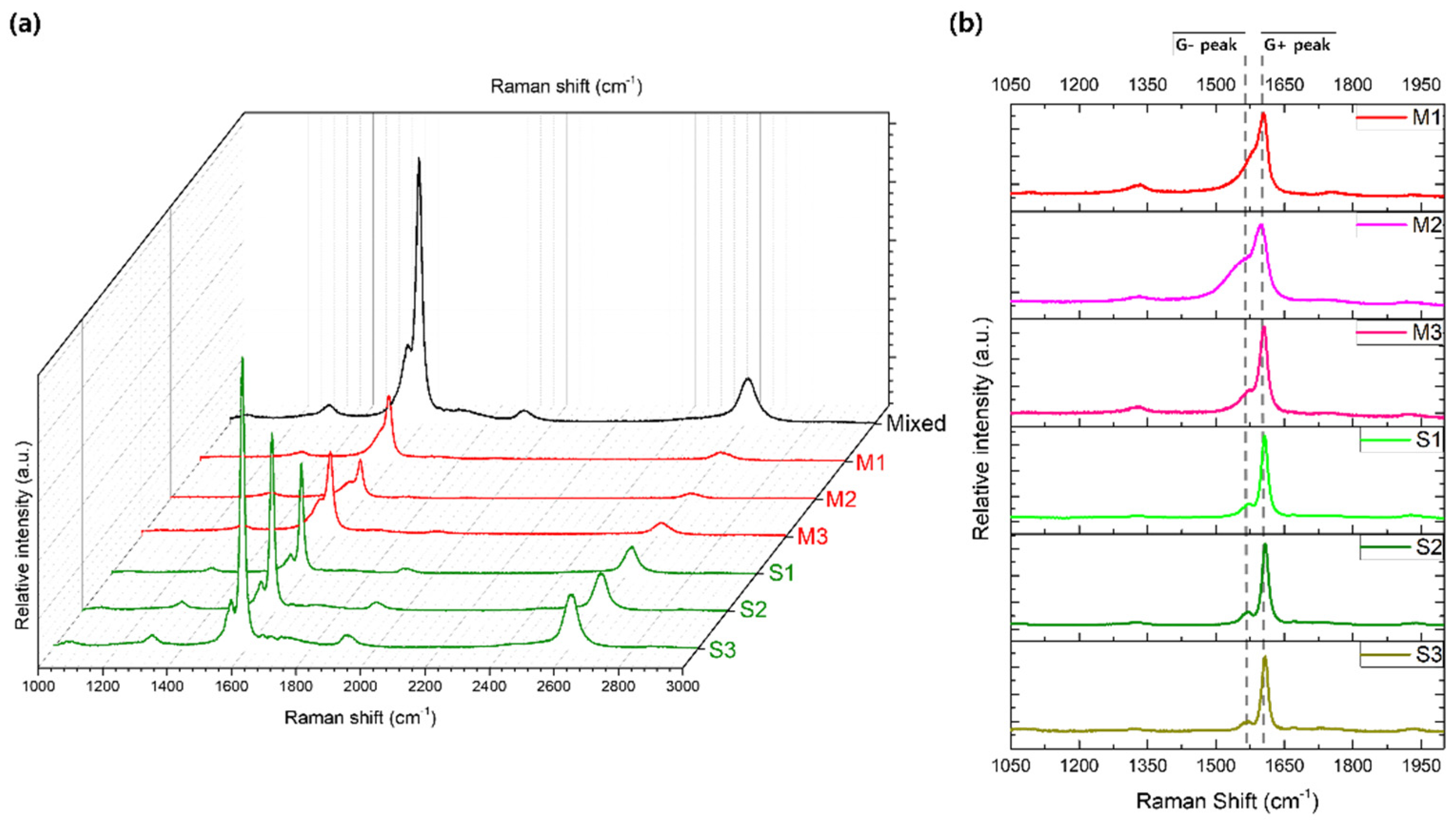

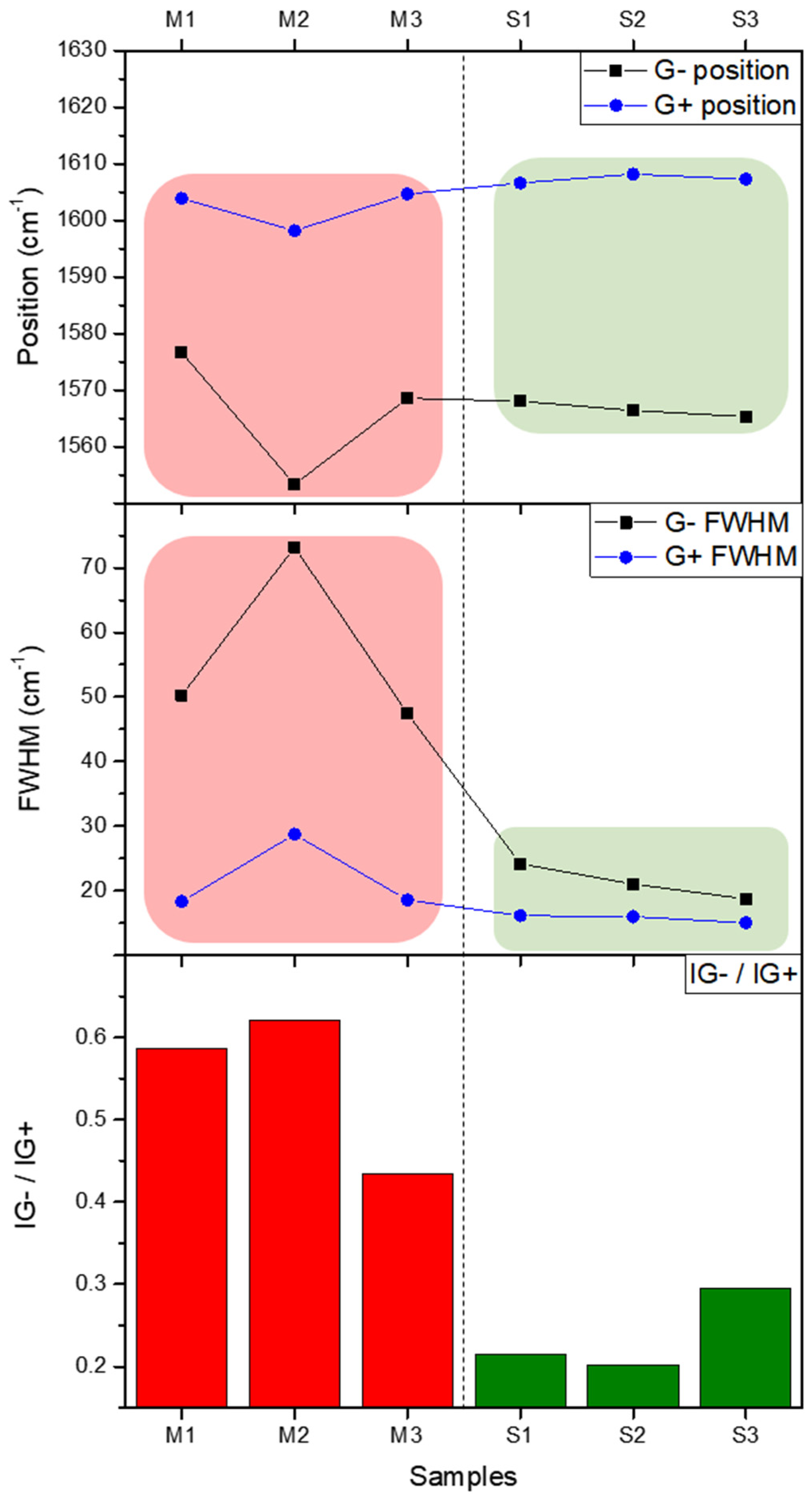

Furthermore, the separated SWNT samples were examined for variations in their G peak profiles, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The G peak, a hallmark of sp²-hybridized carbon structures, provides valuable information on the electronic characteristics of SWNTs. It is typically split into two components: the G⁻ peak, observed around 1560 cm⁻¹, and the G⁺ peak, located near 1590 cm⁻¹ [

20]. The G⁻ peak is associated with atomic vibrations along the nanotube axis, whereas the G⁺ peak corresponds to vibrations in the circumferential direction. In metallic SWNTs, the G⁻ peak is typically broader due to the influence of free electrons, while in semiconducting SWNTs, it appears sharper and more defined, reflecting the absence of free carriers [

21].

Figure 6a provides an overview of the Raman spectra, showing the D, G, and G’ peaks across all separated samples. This spectral profile displays the progressive evolution from mixed SWNTs to metal-enriched (M1–M3) and semi-enriched (S1–S3) fractions, facilitating a comparative analysis of the relative intensities at various Raman shifts. This visual comparison highlights the distinct separation of metallic and semiconducting SWNT components achieved through the process. Specifically,

Figure 6b offers a close-up of the G peaks, where the G⁻ and G⁺ components show noticeable shifts and shape changes across the samples, further evidencing the separation. The elution fractions collected at different stages were labeled as M1, M2, M3 (for metallic SWNTs) and S1, S2, S3 (for semiconducting SWNTs). In

Figure 6b, a clear trend is visible in the G⁻ peak profiles, evolving from a broad shape in M1 to a sharp form in S3, which indicates a continuous enrichment of semiconducting SWNTs through the separation process. The broader G⁻ peaks observed in the M1, M2, and M3 samples underscore their metallic nature, while the progressively narrow G⁻ peaks in S1, S2, and S3 confirm the increasing purity of semiconducting SWNTs in these later fractions.

To quantify the separation efficiency, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the G⁻ peaks was measured, as summarized in

Table 1. Metallic-enriched fractions (M1, M2, M3) exhibited broader G⁻ peaks, with full width at half maximum (FWHM) values between 47.45 and 73.17 cm⁻¹, reflecting a heterogeneous electronic composition. The broadening and asymmetry observed in the G⁻ peaks for metallic SWNTs are characteristic of the Breit-Wigner-Fano (BWF) band, which arises from electron-phonon coupling and the interaction between discrete phonon states and electronic continuum [

22,

23,

24]. This behavior is unique to metallic SWNTs and further highlights their distinct electronic properties compared to semiconducting SWNTs. In contrast, the semiconducting-enriched fractions (S1, S2, S3) displayed narrower G⁻ peaks, with FWHM values ranging from 18.75 to 24.21 cm⁻¹, which is consistent with a well-defined electronic structure. Fractions eluted with 5 wt% SDS (S1, S2, S3) showed FWHM values that were approximately half those of fractions eluted with 0.5 wt% SDS (M1, M2, M3). The reduction in FWHM across sequential samples highlights the progressive isolation of semiconducting SWNTs. The difference in peak positions between metallic and semiconducting SWNTs further corroborates the successful separation. Generally, metallic SWNTs with identical diameters exhibit G⁻ peaks at lower positions than semiconducting SWNTs [

20]. However, as shown in

Table 1, metallic samples M1 and M3 had higher G⁻ peak positions than some semiconducting samples, likely due to the presence of SWNTs with varying diameters, as suggested by the RBM peaks in

Figure 4. Previous studies indicate that smaller-diameter SWNTs, which correspond to RBM peaks at higher wavenumbers, tend to display G⁻ peaks at lower wavenumbers [

20,

21]. The samples separated with 5 wt% SDS in

Figure 4 exhibited RBM peaks at larger wavenumbers than those separated with 0.5 wt% SDS, suggesting that the G⁻ peaks in S1, S2, and S3 are influenced by SWNT diameter. Additionally, the intensity of G

− for each sample was divided by the intensity of G

+ to represent the relative ratio of the two peak intensities. M1, M2, and M3 showed values ranging between 0.43 and 0.62, while S1, S2, and S3 exhibited relatively lower values, ranging between 0.20 and 0.30.

Figure 7.

Position, FWHM, and relative intensity ratio of G⁻ and G⁺ peaks are compared across separated SWNT samples (M1–M3 for metallic-rich, S1–S3 for semiconducting-rich fractions). The upper panel illustrates the G⁻ and G⁺ peak positions, highlighting systematic shifts due to electronic differences. The middle panel presents the FWHM for G⁻ and G⁺ peaks, showing broader G⁻ peaks for metallic-rich fractions. The lower panel depicts the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio, which decreases progressively from metallic-rich to semiconducting-rich fractions, offering a clear metric for distinguishing electronic types in SWNTs.

Figure 7.

Position, FWHM, and relative intensity ratio of G⁻ and G⁺ peaks are compared across separated SWNT samples (M1–M3 for metallic-rich, S1–S3 for semiconducting-rich fractions). The upper panel illustrates the G⁻ and G⁺ peak positions, highlighting systematic shifts due to electronic differences. The middle panel presents the FWHM for G⁻ and G⁺ peaks, showing broader G⁻ peaks for metallic-rich fractions. The lower panel depicts the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio, which decreases progressively from metallic-rich to semiconducting-rich fractions, offering a clear metric for distinguishing electronic types in SWNTs.

The trends of G⁻ and G⁺ in the metallic and semiconducting samples are summarized in

Figure 6, offering a comprehensive overview of the separation efficiency achieved via microfluidic gel chromatography combined with in-situ Raman spectroscopy, as described in this study. The degree of separation is evident in the distinct differences in peak position, FWHM, and the relative intensity ratio (I

G⁻/I

G⁺), all of which clearly distinguish the electronic and structural characteristics of the two SWNT types. In particular, the pronounced broadening in the FWHM of G⁻ and the marked variations in I

G⁻/I

G⁺ ratios confirm the effectiveness of the microchannel-enabled separation technique. In the upper panel, the G⁻ peak positions for metallic-enriched fractions (M1, M2, M3) are systematically lower than those for semiconducting-enriched fractions (S1, S2, S3). This trend arises from the unique electronic density of states near the Fermi level in metallic SWNTs, underscoring the fundamental impact of electronic type on Raman spectral features. In contrast, the G⁺ peak remains relatively stable across all fractions, demonstrating its independence from electronic properties. The middle panel emphasizes the striking contrast in the FWHM of G⁻ peaks between the two types of SWNTs. The broader and more asymmetric G⁻ peaks in the metallic fractions, with FWHM values ranging from 47.45 to 73.17 cm⁻¹, reflect the influence of the BWF line shape caused by electron-phonon coupling. By comparison, the semiconducting fractions exhibit narrower G⁻ peaks (18.75–24.21 cm⁻¹), indicative of their uniform electronic structure and the progressive isolation achieved during separation. In the lower panel, the relative intensity ratio (I

G⁻/I

G⁺) serves as a robust metric for differentiating metallic and semiconducting fractions. Metallic-enriched samples display significantly higher ratios (0.43–0.62), consistent with the dominance of the broadened G⁻ peak, whereas semiconducting-enriched fractions show much lower ratios (0.20–0.30), reflecting their distinct Raman characteristics. These observations collectively validate the microfluidic gel chromatography-enabled in-situ Raman spectroscopy approach for selective electronic-type separation and analysis of SWNTs. Not only does this methodology effectively isolate metallic and semiconducting SWNTs, but it also reveals subtle vibrational and electronic interactions inherent to each type. The pronounced differences in G peak characteristics—spanning position, width, and intensity ratio—underscore the critical role of electron-phonon interactions and diameter variation in defining the Raman spectral behavior of SWNTs.

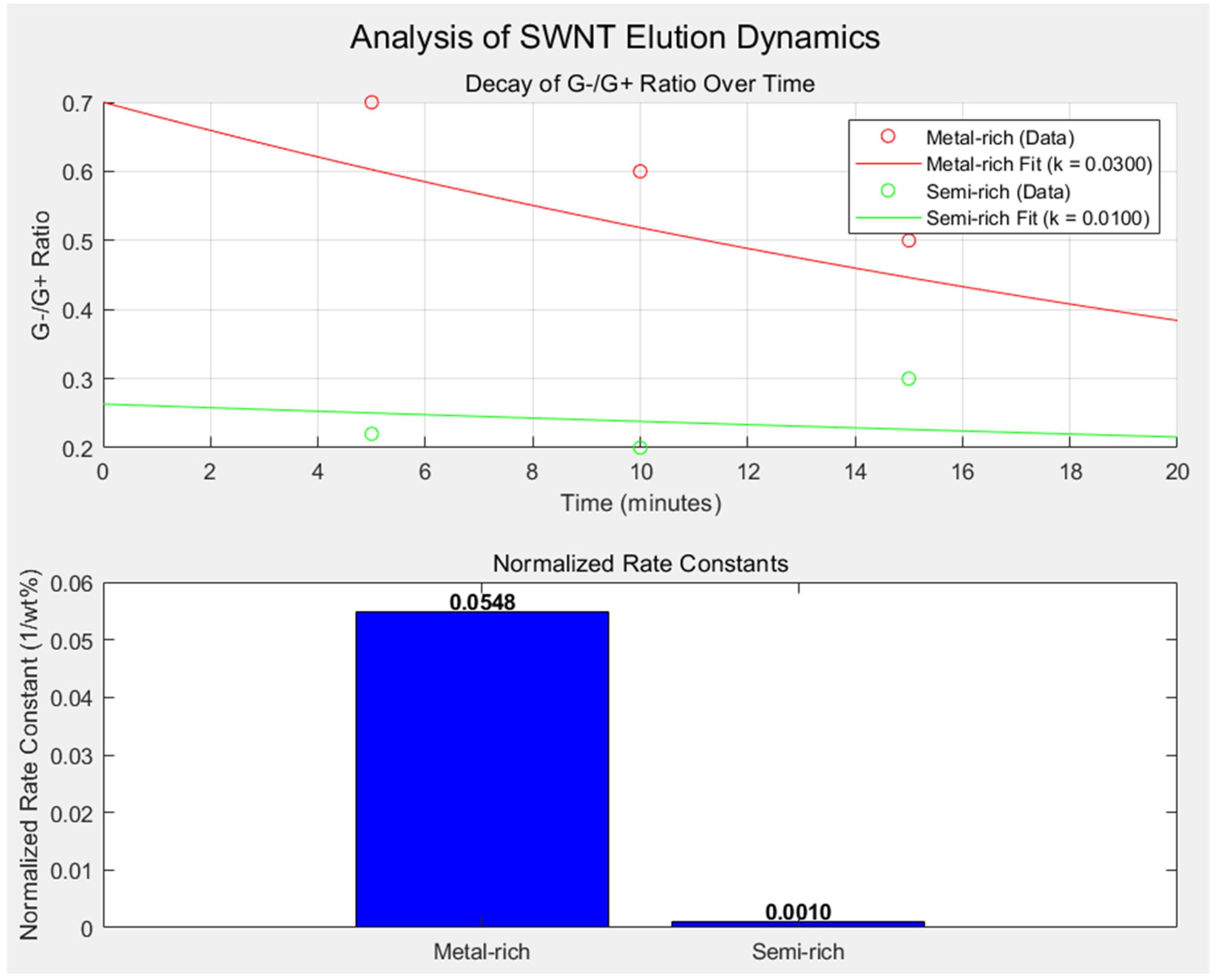

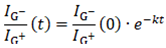

Figure 8 provides an integrated view of the elution dynamics and separation characteristics of metallic- and semiconducting-enriched SWNT fractions. The analysis is based on the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio measured from Raman spectroscopy for M1–M3 (metal-rich, SDS 0.5 wt%) and S1–S3 (semi-rich, SDS 5 wt%) samples. These values were analyzed over time to calculate rate constants for elution and assess SWNT purity, while accounting for the differing SDS concentrations used during separation.

Methodology for Rate Constant Calculation

To derive the rate constants, the decay in the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio over time was modeled using a single exponential decay function, assuming that the elution dynamics follow a first-order process. The measured data were fit to the Equation (1):

where,

is the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio at time

t,

is the initial ratio, and

k is the rate constant of elution. For metallic-rich fractions (M1–M3), the decay dynamics yielded,

kmetal = 0.0300 min

−1, reflecting their rapid elution due to weaker interactions with the gel matrix. In contrast, the semiconducting-rich fractions (S1–S3) exhibited

ksemi = 0.0100 min

−1, which aligns with their stronger retention influenced by increased SDS-mediated gel interactions. The larger rate constant for the metallic fractions reflects their faster elution, consistent with weaker interaction with the gel matrix compared to semiconducting SWNTs.

Normalization of Rate Constants

To account for the 10-fold difference in SDS concentration between metallic- and semiconducting-enriched fractions (0.5 wt% vs. 5 wt%), the rate constants were normalized using the Equation (2):

where, [SDS] is the SDS concentration in wt%. The normalization yielded

knormalized,metal = 0.0548 min

−1·wt

−1% and

knormalized,semi = 0.0010 min

−1·wt

−1%, highlighting the distinct separation dynamics for each SWNT type.

The upper panel of

Figure 8 illustrates the decay of the G⁻/G⁺ ratio over time for both metallic- and semiconducting-enriched fractions. The metallic-rich fractions exhibit a steeper decay curve, indicative of faster elution rates. In contrast, the semiconducting-rich fractions show a more gradual decay, consistent with their stronger interaction with the gel matrix due to electronic differences. The lower panel of

Figure 8 presents the normalized rate constants, emphasizing the intrinsic elution dynamics independent of SDS concentration. The higher normalized rate constant for metallic-rich SWNTs reflects their weaker van der Waals interaction with the gel matrix, while the lower value for semiconducting-rich SWNTs underscores their stronger retention due to greater gel affinity. The clear separation of rate constants between metallic- and semiconducting-enriched fractions correlates with their respective purities. The purity of each fraction is closely tied to the elution dynamics, as faster elution typically corresponds to lower gel-matrix interaction and higher metallicity. Conversely, the slower elution of semiconducting SWNTs aligns with their greater affinity for the gel and higher electronic uniformity. These findings validate the use of G⁻/G⁺ ratio decay as a reliable metric for quantifying SWNT separation efficiency and purity. This analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of the microfluidic gel chromatography approach for achieving precise electronic-type separation of SWNTs. It further underscores the importance of considering both experimental parameters (e.g., SDS concentration) and intrinsic SWNT properties when interpreting rate constants and purity metrics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.H., B.B, S.J. and W.J.; methodology, J.-H.H., B.B., S.J. and W.J.; validation, B.B., S.J., W.J., J.W., J.J., Y.-J.C. and M.-K.M.; formal analysis, B.B., S.J. and W.J.; investigation, B.B., S.J., W.J., J.W., J.J., Y. -J.C. and M.-K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.H., B.B., S.J. and W.J.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.H., B.B., S.J. and W.J.; visualization, B.B., S.J. and W.J.; supervision, J.-H.H.; project administration, J.-H.H.; funding acquisition, J.-H.H.

is the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio at time t,

is the G⁻/G⁺ intensity ratio at time t,  is the initial ratio, and k is the rate constant of elution. For metallic-rich fractions (M1–M3), the decay dynamics yielded, kmetal = 0.0300 min−1, reflecting their rapid elution due to weaker interactions with the gel matrix. In contrast, the semiconducting-rich fractions (S1–S3) exhibited ksemi = 0.0100 min−1, which aligns with their stronger retention influenced by increased SDS-mediated gel interactions. The larger rate constant for the metallic fractions reflects their faster elution, consistent with weaker interaction with the gel matrix compared to semiconducting SWNTs.

is the initial ratio, and k is the rate constant of elution. For metallic-rich fractions (M1–M3), the decay dynamics yielded, kmetal = 0.0300 min−1, reflecting their rapid elution due to weaker interactions with the gel matrix. In contrast, the semiconducting-rich fractions (S1–S3) exhibited ksemi = 0.0100 min−1, which aligns with their stronger retention influenced by increased SDS-mediated gel interactions. The larger rate constant for the metallic fractions reflects their faster elution, consistent with weaker interaction with the gel matrix compared to semiconducting SWNTs.