Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

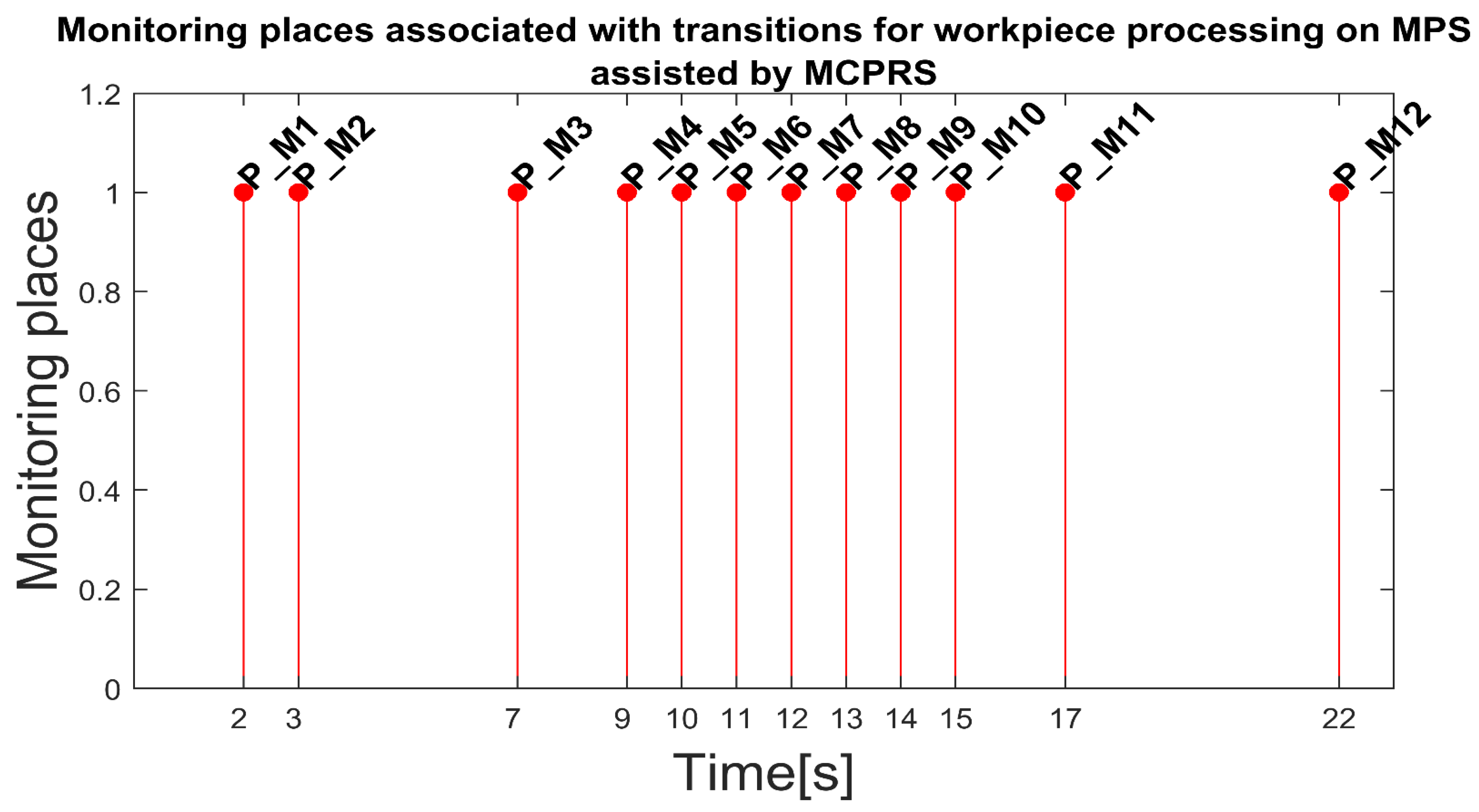

- Processing: WP is processed sequentially at stations such as buffering, handling, processing, and sorting/storage.

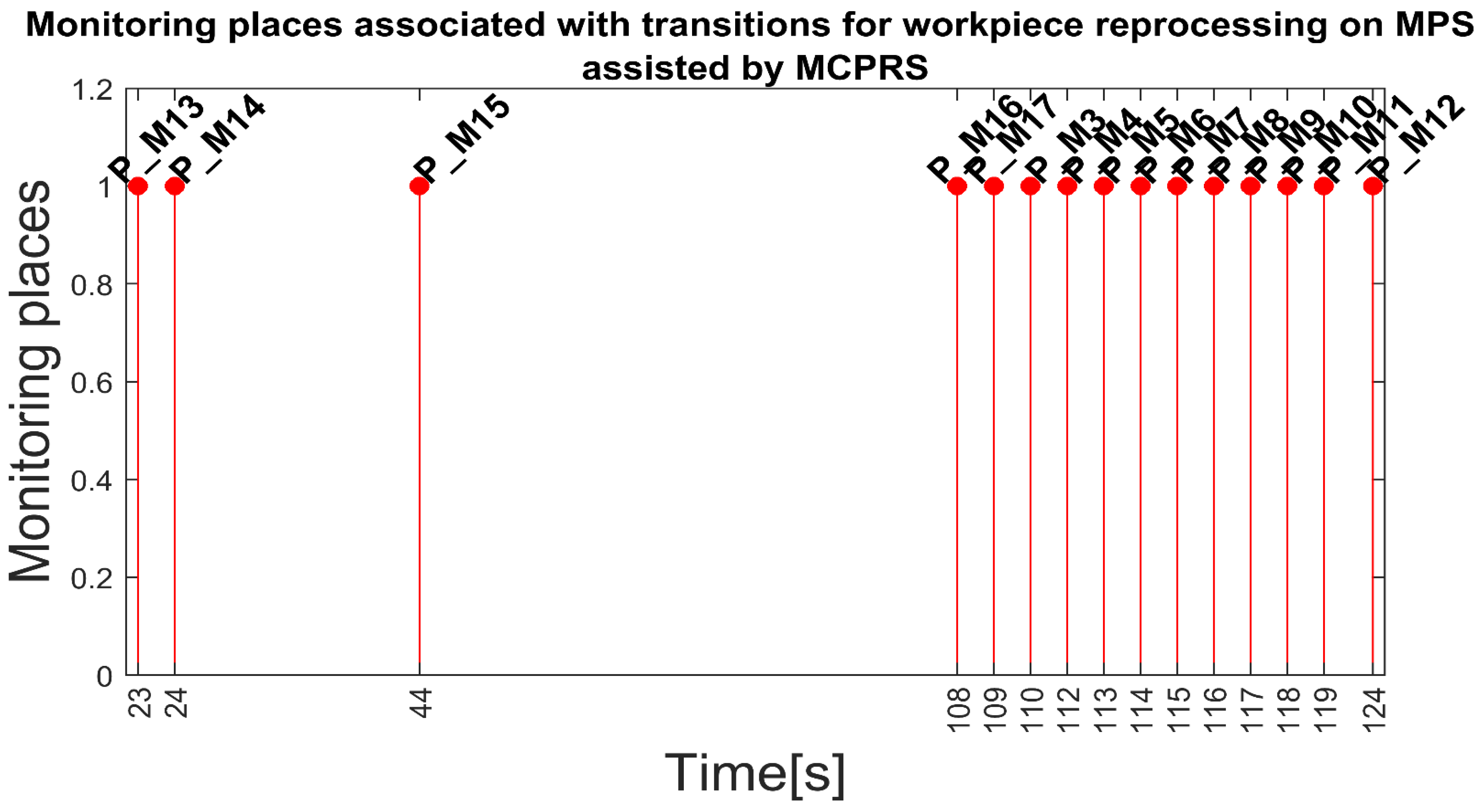

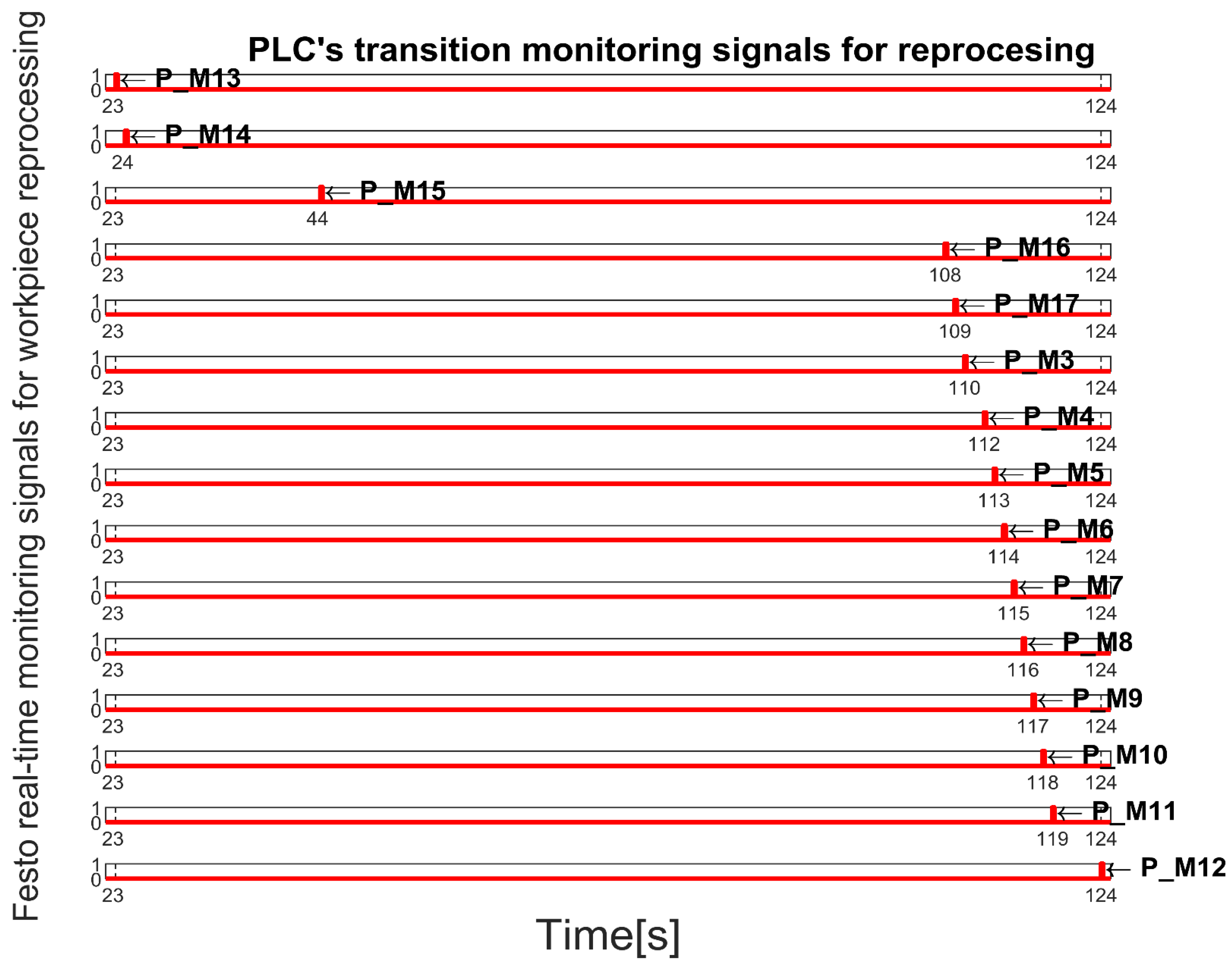

- Reprocessing: WP failing the Primary Quality Test (PQT) at the sorting and storage WS are transported back by the MCPRS to the buffer WS. This WP undergoes a second cycle of processing to meet quality standards.

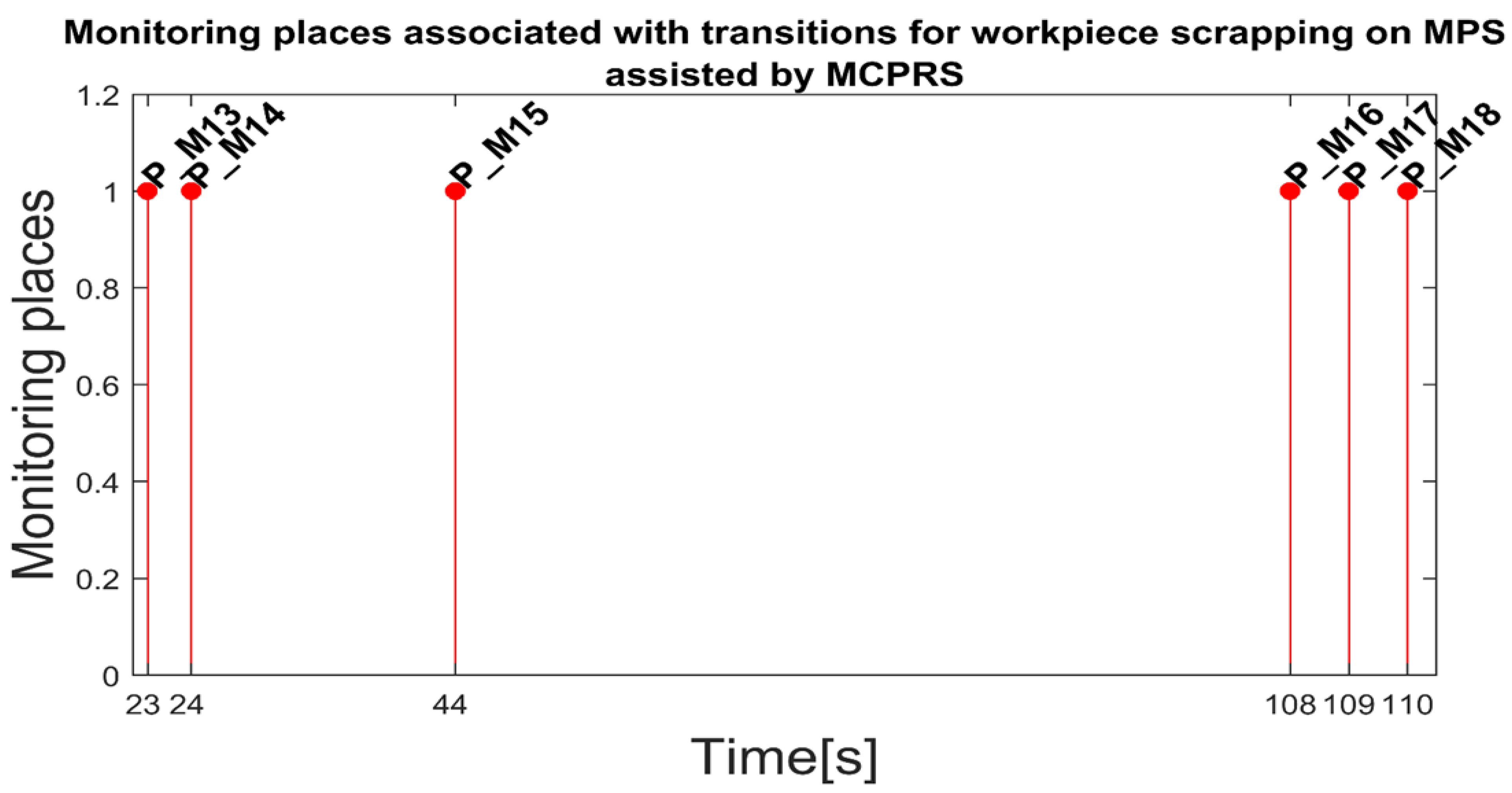

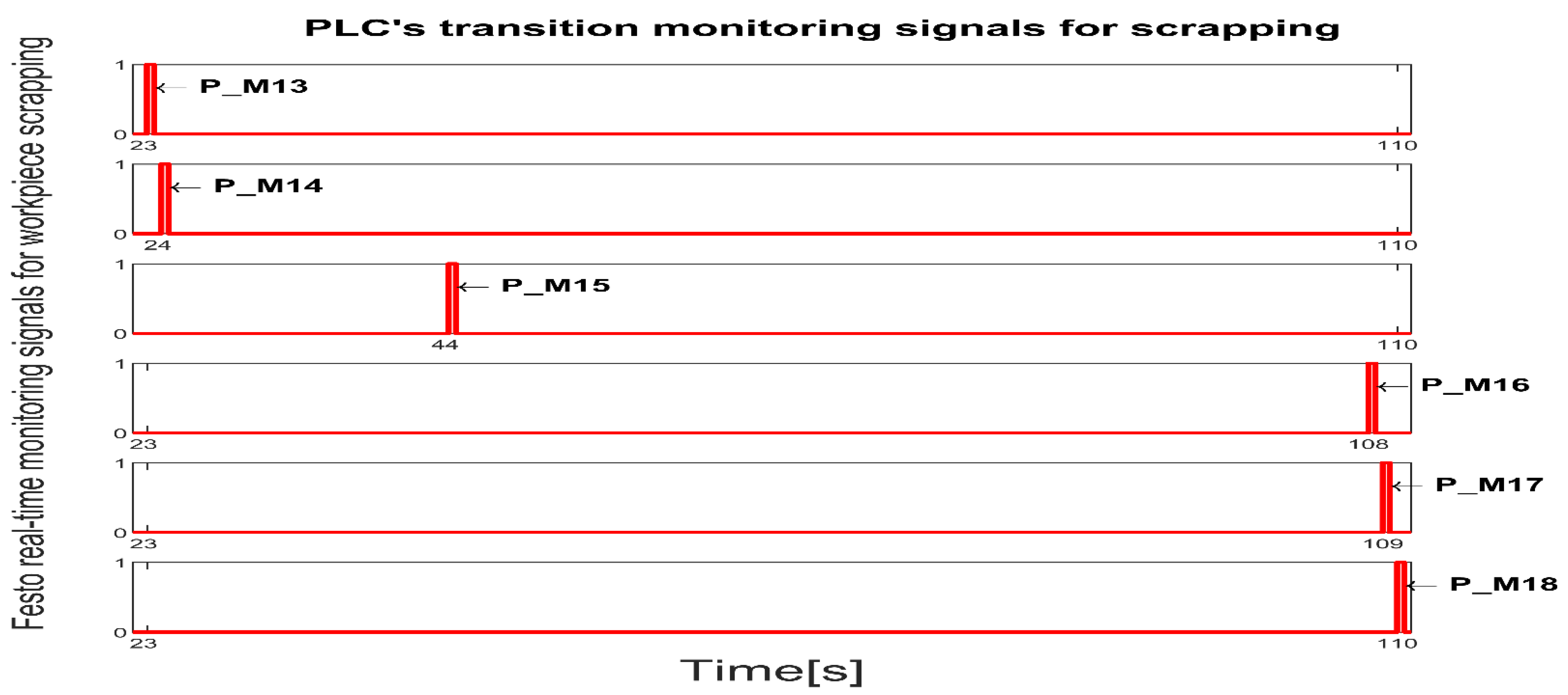

- Scrapping: WP failing the Secondary Quality Test (SQT) at the handling WS are classified as scrap. MCPRS ensures these defective WPs are segregated for disposal, maintaining production flow efficiency.

- Remote Accessibility: Cloud/VPN-based interfaces provide real-time monitoring and control. User can observe, plan, and adjust tasks remotely, ensuring flexible and scalable production User interacts visually with production systems via AR-enhanced HMIs. AR facilitates real-time visualization of robotic and WS operations, enabling task.

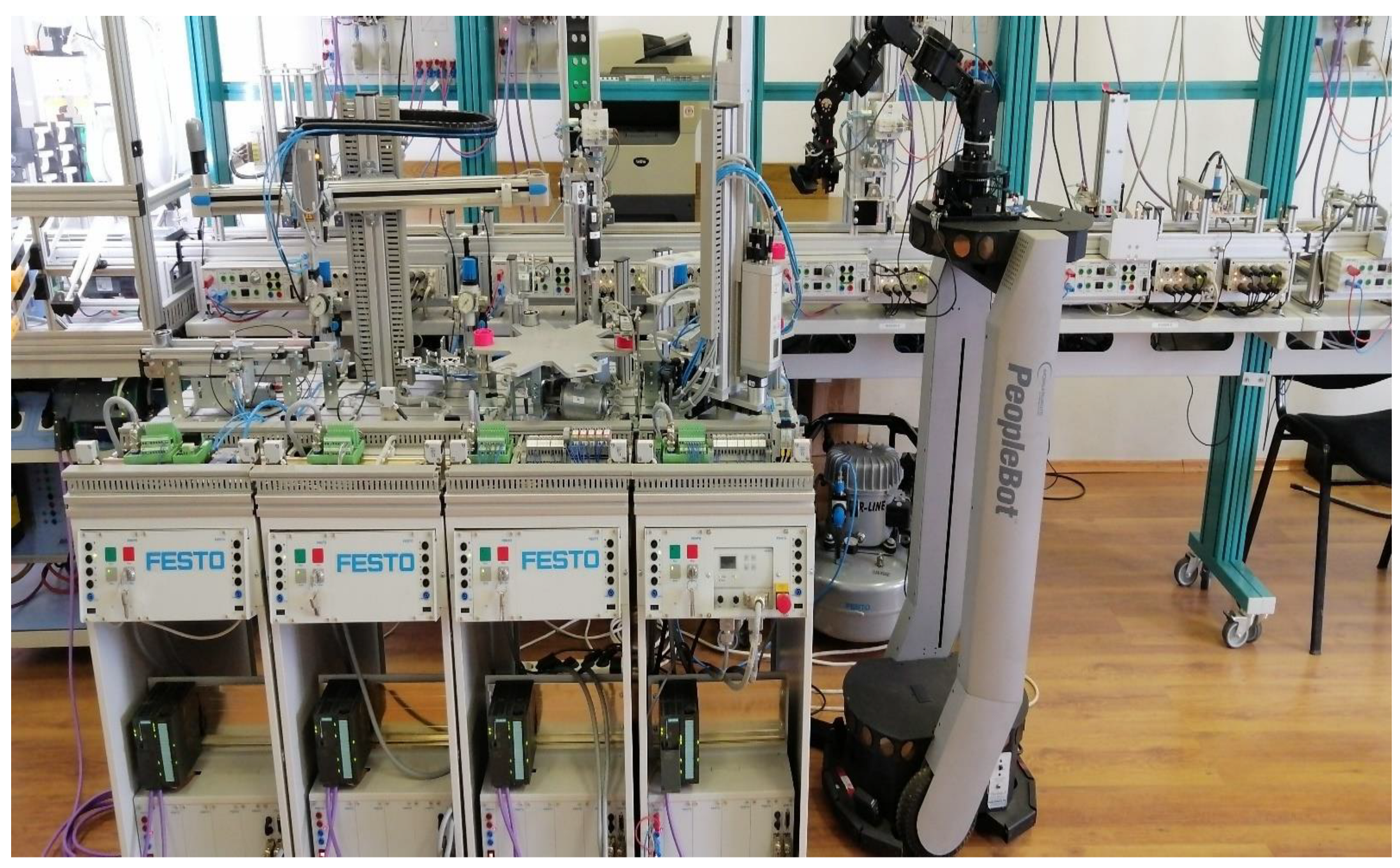

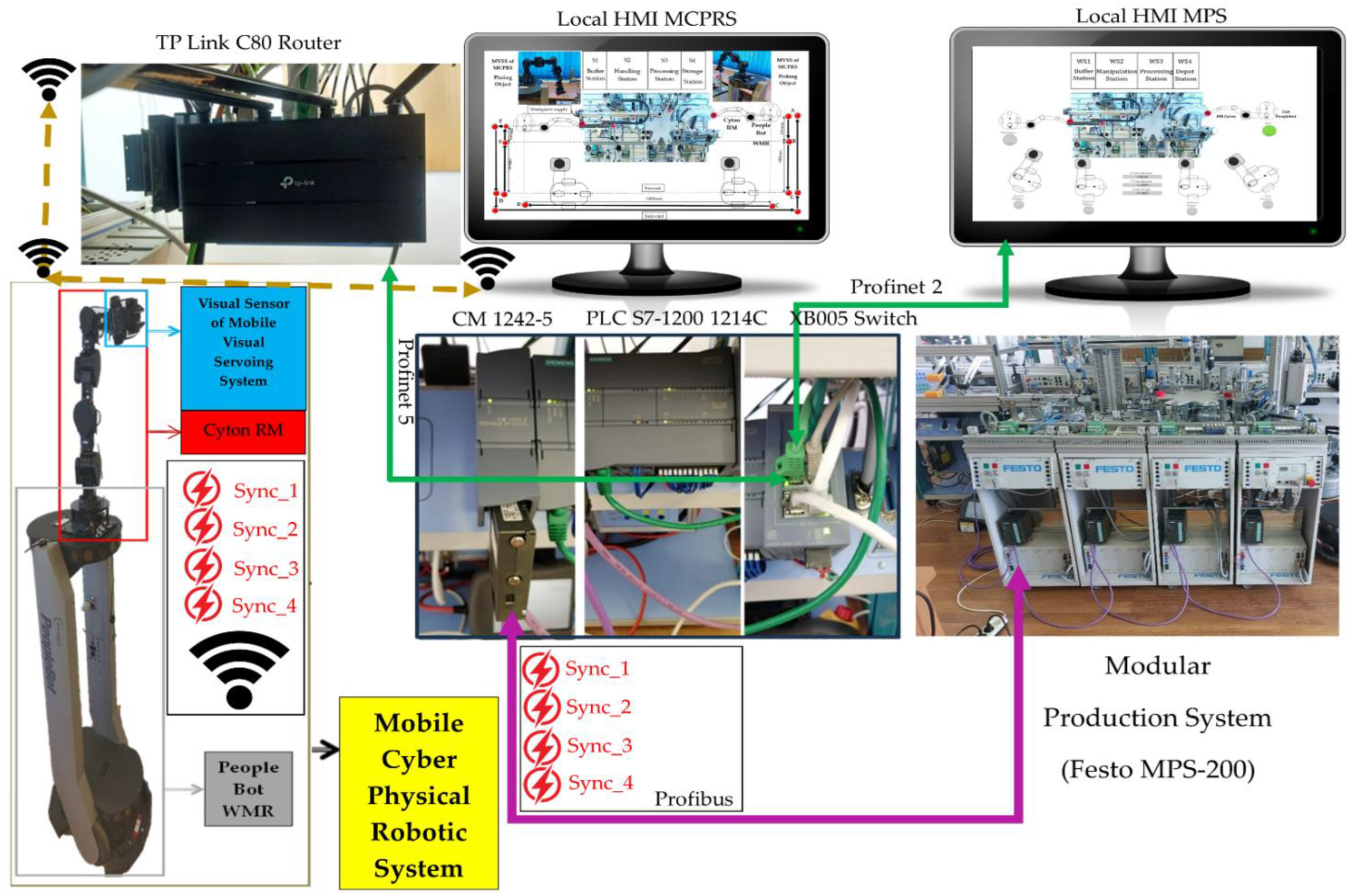

2. Hardware Architecture of MPS with MCPRS Assistance

2.1. Main Devices and Functinalites

- coordinate and controls the overall production flow across the four WSs,

- control communication between the MPS’s WSs (buffer, handling, processing, sorting/storage) and MCPRS,

- control task synchronization between MPS operation and MCPRS.

- interfaces with remote systems over OPC-UA, WAN-Ethernet, and other networks for cloud-based SCADA and HMI control.

- be responsible for the operations within its respective WS,

- communicate with the master S7-1200 PLC via Profibus, which facilitates synchronized, real-time control of individual WS’s tasks,

- send status, update and task completion to the master PLC, allowing centralized decision-making.

2.2. IoT Edge Devices, Profibus, Profinet, LAN Ethernet, WAN Ethernet and Networking

2.3. Profibus, LAN-Profinet, LAN-Ethernet and WAN-Ethernet Communication Networks

2.4. Multilevel Architecture of MPS Assisted by MCPRS

2.5. Assumptions Regarding P/R/S Operations on MPS

2.6. Assumptions Regarding the Assistance of P/R/S Technology by MCPRS

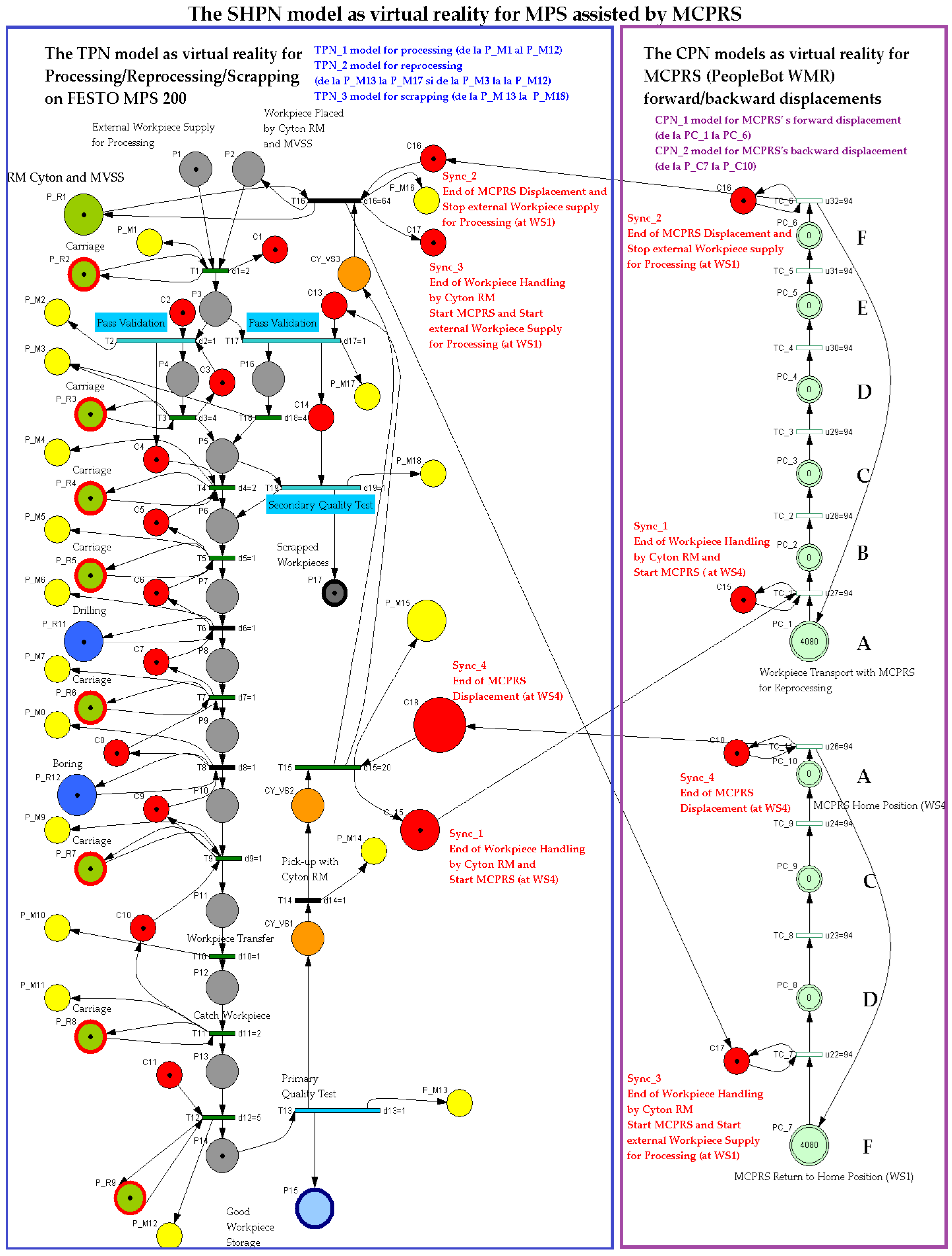

3. The Virtual World as a Digital Counterpart of P/R/S Technology on MPS Assisted by MCPRS

3.1. AR and VR as Components of the Virtual World

- VR with SHPN to model P/R/S workflow by using SHPN simulation and Sirphyco package, [29].

3.2. Workflow, Task Planning, Synchronization, SHPN Structure

3.3. SHPN T Gether with TPN and CPN Models, Formalism, and Simulation

3.4. Virtual Digital Counterpart of the MCPRS

4. Real World of P/R/S on MPS Assisted by MCPRS

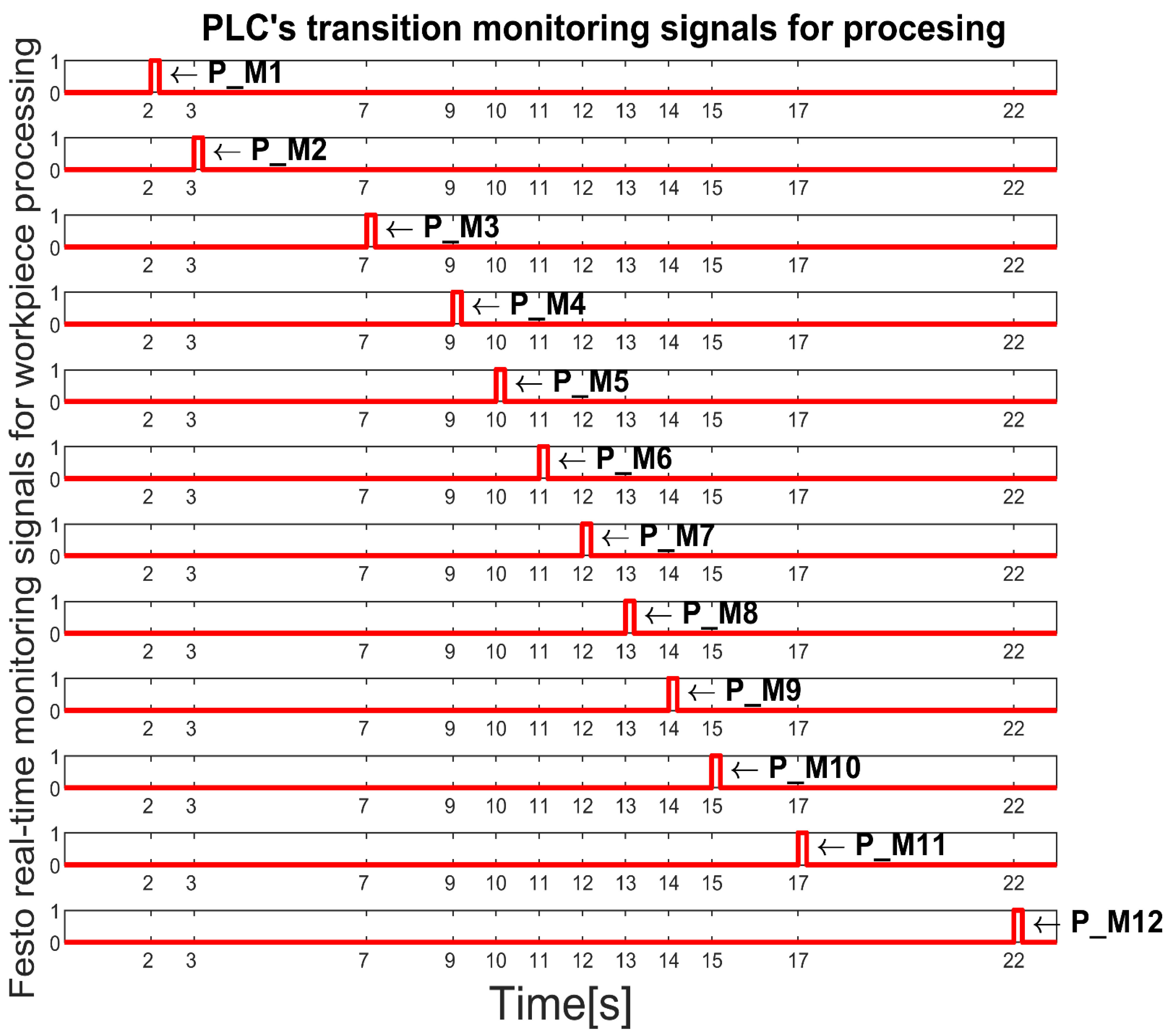

4.1. SCADA Monitoring Signals and Syncronization

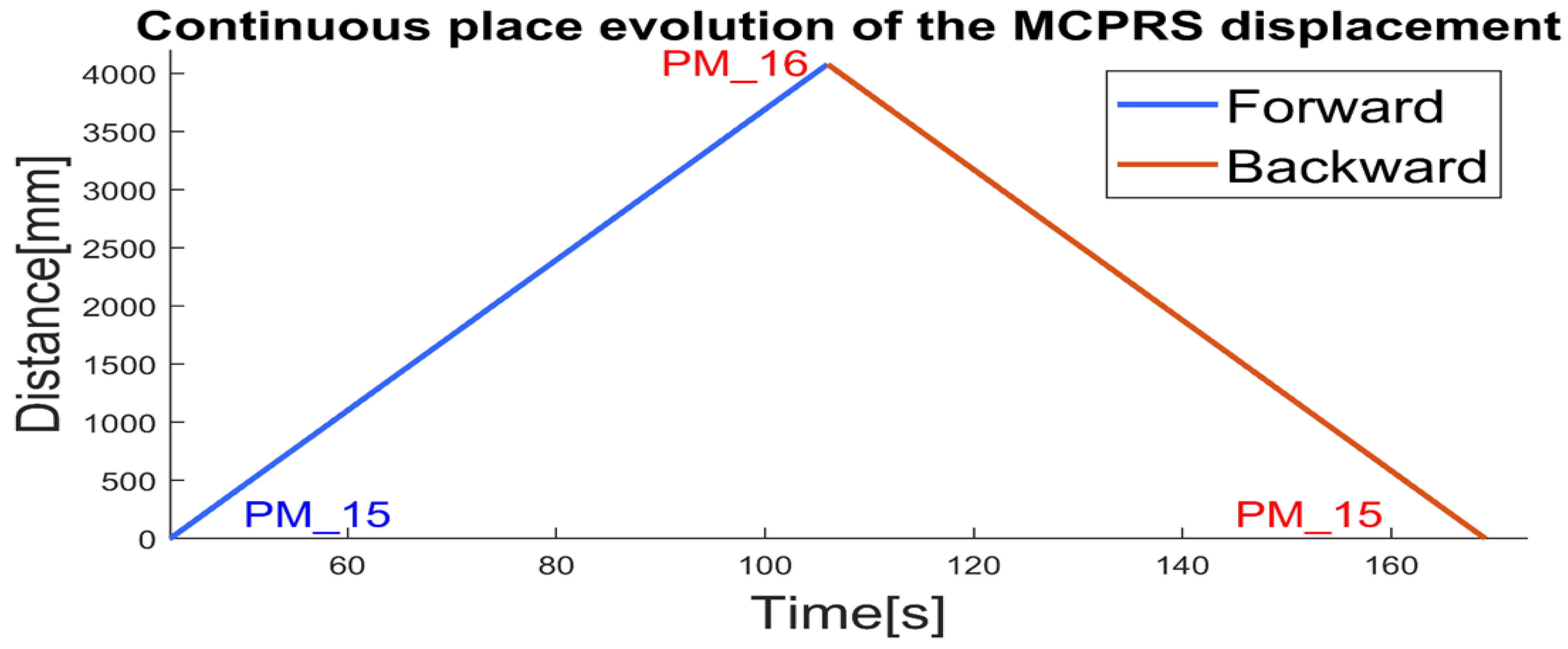

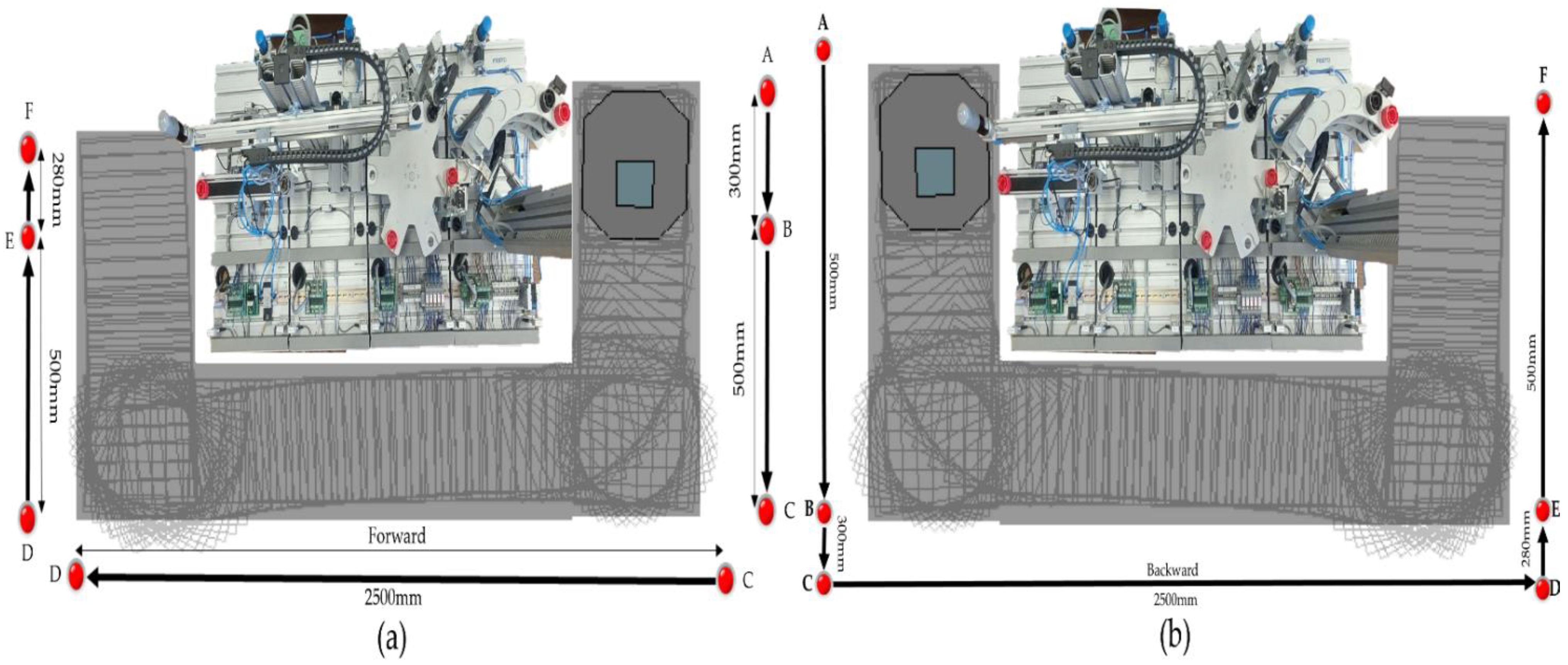

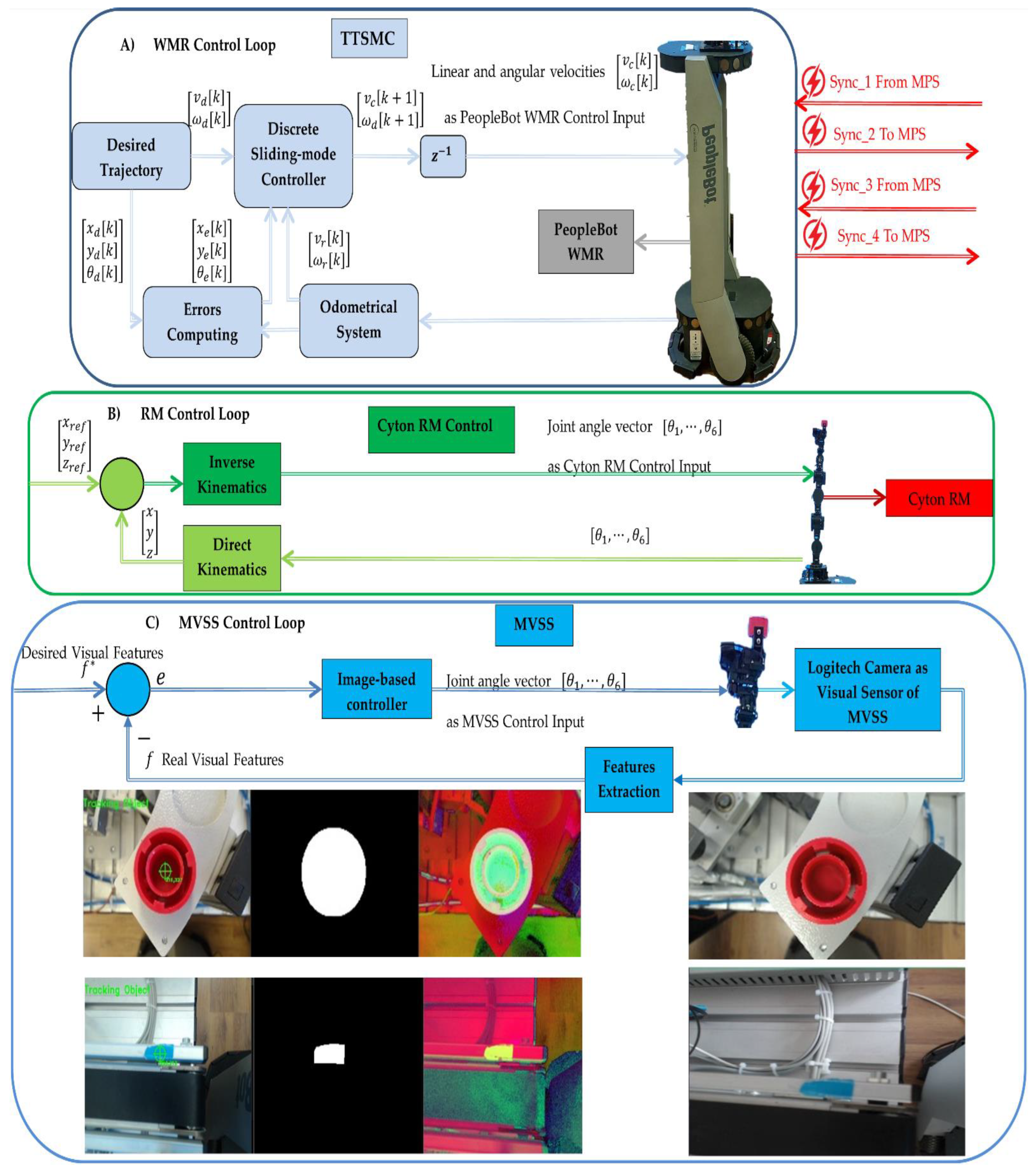

4.2. Real-Time Control of MCPRS

4.3. Real-Time Control of MPS Assisted by MCPRS

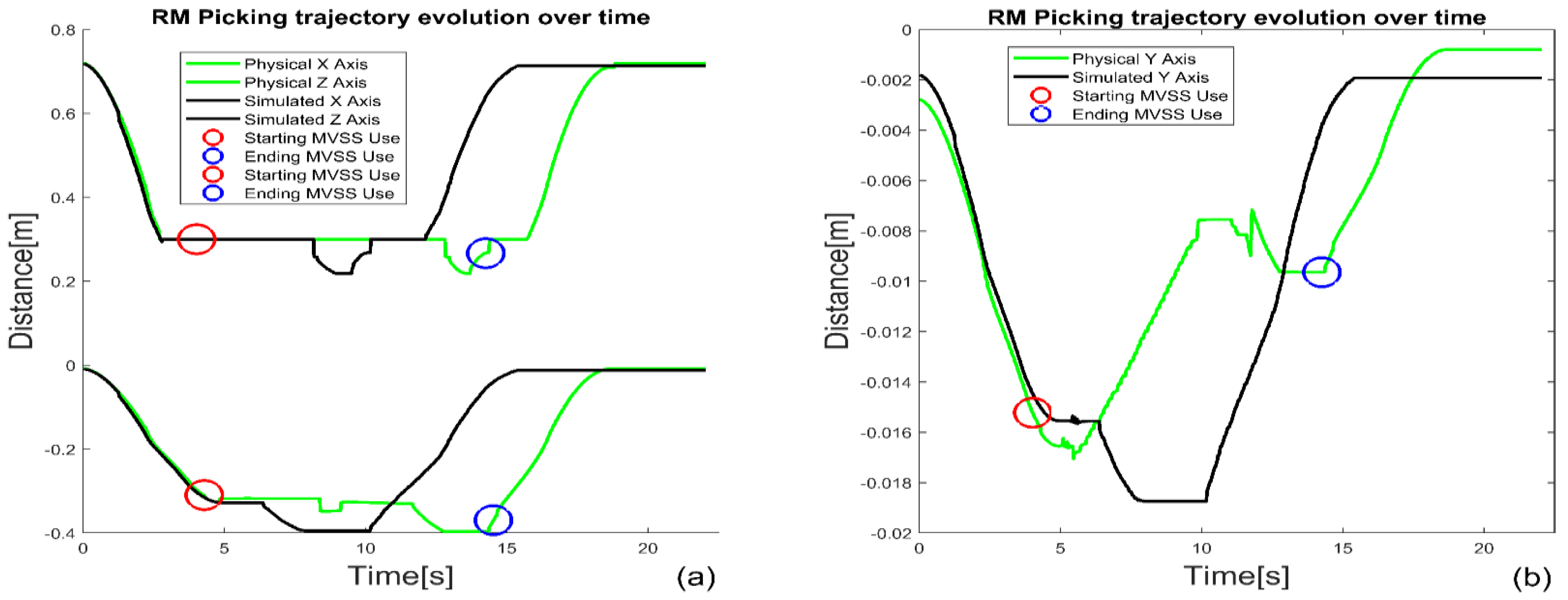

- Picking operations, detection and precision control: The remote or local PC-HMI-MCPRS calculates positioning commands for the Cyton 1500 robotic manipulator (RM). These commands guide the RM for initial positioning for pickup operations at WS4. In Figure 18, the MVSS steps for WP detection are shown when taking over from WS4. On the upper left side in Figure 18 is vision-based detection by MVSS. Detection utilizes RGB-to-HSV color model conversion for robustness under varying lighting conditions. HSV better handles light changes compared to RGB, crucial during transitions between natural and artificial lighting. Object shape and position are determined using Ramer-Douglas-Peucker algorithm that simplifies the object contour for shape analysis. Canny Edge Detection identifies the edges of the object for precise contouring. Centroid tracking employs the method of image moments, ensuring efficient 2D tracking. The process is robust for circular objects, consistently identifying their centroid within acceptable error limits. All of this was implemented using the OpenCV libraries, [37]. Finally, in the image on the top right of the medallion in Figure 18, the object is tracked, meaning the target has been identified, if both the color and shape conditions were simultaneously met, [13].

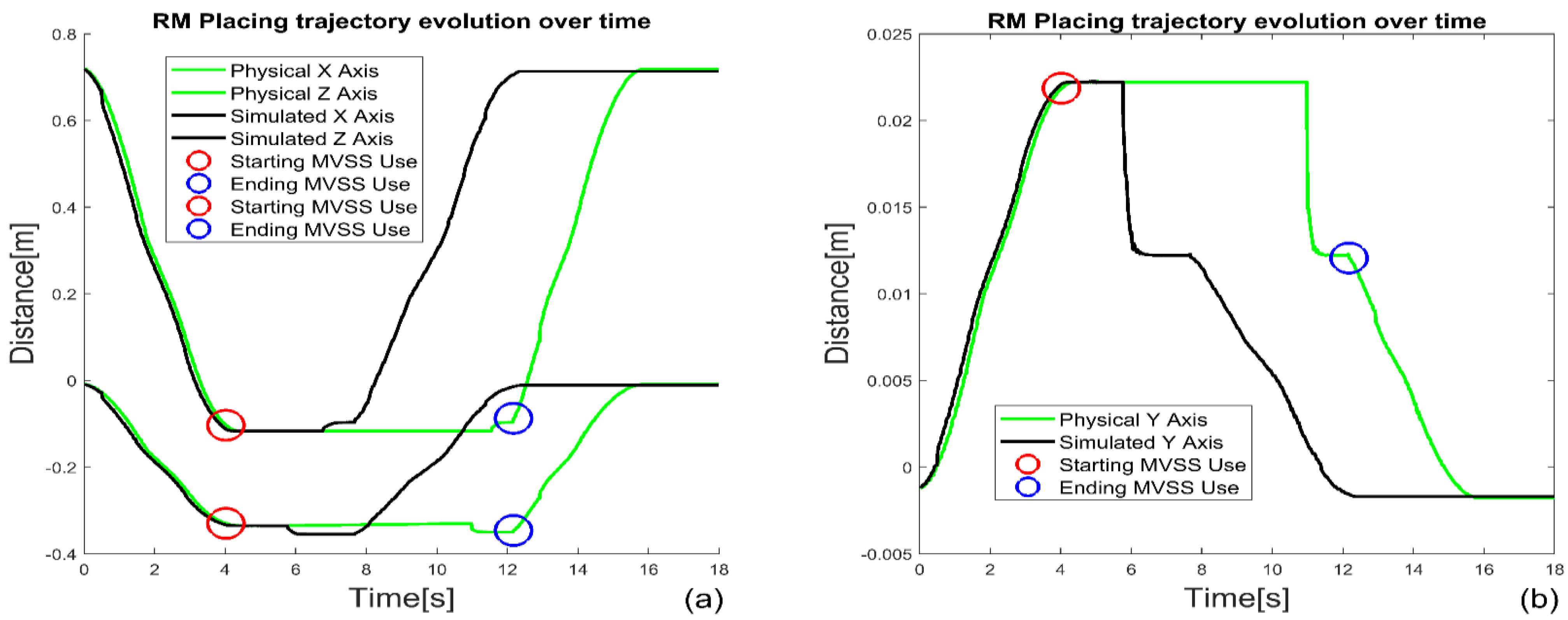

- Vision-based detection, alignment reference point and placing operations: On the upper left side in Figure 19 is: WS1 detection and alignment reference point detection. The WS1 placement relies on detecting a rectangular reference point, contrasting the circular object detection at WS4. This step ensures accurate alignment for reprocessing or scrapping. Fine Positioning with MVSS: like positional refinement is based on real-time feedback from MVSS. Adjustments in end-effector positioning minimize error before placement.

5. Discussion

- Remote control and flexibility through the Cloud/VPN system. Users can control MPS and MCPRS by AR interfaces for task management. The VPN ensures secure access, while OPC-UA facilitates data sharing with cloud platform.

- Enhanced workflow optimization by using SHPN simulation allows for systematic modelling of both continuous and discrete processes, helping to optimize task execution and prevent bottlenecks in the system.

- Advanced communication infrastructure by using Profibus DP, Profinet, Ethernet, and OPC-UA ensures real-time, reliable communication across the system, with seamless integration between the production line, robotic systems, and cloud.

- Interoperability and future scalability with OPC-UA, LAN-Profinet, and LAN Ethernet, the system is future-proof, allowing for easy integration of additional devices, sensors, or workstations as needed.

- Real-time task planning and visualization by planning tasks, simulating workflows, and visualizing the system in real-time through AR and VR interfaces, enabling quick decisions and optimizations.

- Enhanced flexibility by using SHPN, TPN and CPN, models allowing for flexible task execution, supporting both discrete (stationary WSs) and continuous (MCPRS) operations.

- Fault detection and reprocessing with MCPRS assisting in reprocessing defective WPs, reducing downtime and improving overall production efficiency. Visual feedback through MVSS allows the MCPRS to autonomously handle quality control tasks.

- Cloud-based control through OPC-UA and WAN-Ethernet, the system can be monitored and controlled remotely, offering cloud-based SCADA/HMI interfaces for enhanced accessibility and control from any location.

- Measure the percentage of tasks successfully completed without interruptions or errors, such as processing, reprocessing, and scrapping workflows. Evaluate the synchronization between the MPS and MCPRS. Use metrics like delay in command execution or deviations between DT simulations and real-world actions.

- Test the latency of the Cloud/VPN connection, particularly for critical operations requiring real-time feedback (task planning with AR or reprocessing tasks). Monitor the availability of the system components, (PLCs, embedded computer, MCPRS, WSs and DT) under varying operational loads. Measure the number of WPs processed, reprocessed, or scrapped per unit of time.

- Simulate scenarios with varying task complexities and multiple users remotely access the system to test scalability. Evaluate how well the system adapts to changes in production requirements, including the addition of new tasks or equipment.

- Conduct surveys or interviews with remote and local users to understand their experience with AR-based task planning and VR visualizations. Evaluate HMIs in terms of intuitiveness, error rates, and ease of navigation. Measure the time required for new users to learn and operate the system efficiently.

- Count system failures, communication errors, or downtime incidents over a defined period. Conduct penetration testing to evaluate the resilience of the Cloud/VPN infrastructure against cyber threats.

- Compare the DT simulation outcomes with real-world results. Metrics include deviation in task execution times or movements of the MCPRS. Assess the accuracy and usefulness of AI (machine learning)-based maintenance alerts or process optimizations

- Monitor the energy efficiency of the MPS and MCPRS during operations. Calculate the costs associated with remote operations and compare them to traditional on-site methods.

- Use SHPNs to simulate different production scenarios and validate system responses. Leverage SCADA systems to display and analyze key performance indicators in real time. Compare the system's performance against industry standards or similar setups.

- Ensure HMIs provide intuitive, real-time visual feedback about the status of the MPS and MCPRS (WP location, task progress, errors). Include 3D models and AR/VR representations linked to the DT to visualize task planning and execution interactively. Implement customizable dashboards, allowing users to tailor views based on their roles. Use touch-based or voice-controlled interfaces for ease of operation, especially for mobile or wearable devices. Maintain consistency in layout, color schemes, and symbols across various control panels for different systems (MCPRS control vs. MPS task planning). Follow established user interface design guidelines, such as those from ISO standards for industrial interfaces. Include built-in mechanisms for guiding users to avoid common errors (confirmations for critical actions, visual warnings for system constraints). Provide contextual troubleshooting suggestions based on detected issues. Provide contextual troubleshooting suggestions based on detected issues.

- Design hierarchical menus logically, ensuring quick access to critical functions such as emergency stops or manual overrides. Enable multi-layer zoom for detailed and high-level views of the entire MPS and MCPRS workflows. Use automated task suggestions and assistive AI tools to streamline repetitive or complex operations. Offer drag-and-drop task scheduling in AR/VR environments for task planning. Provide auditory, haptic, or visual feedback to confirm actions, such as successful execution of reprocessing and scrapping command or MCPRS movement. Ensure HMIs are accessible to diverse users, including features like multilingual support, adjustable text sizes, and high-contrast modes.

- Include in-app feedback forms or direct links to reporting issues or requesting new features. Implement a feedback loop where operators receive responses to their suggestions or concerns. Track user interaction metrics, average task time, and error rates to identify usability bottlenecks. Regularly test HMIs with end-users during design and after deployment.

- Enable users to manipulate 3D models in AR to visualize and modify workflows dynamically. Allow operators to walk through virtual environments to practice controlling MPS and MCPRS workflows or diagnose issues remotely.

- Log errors to identify areas where HMIs complexity may lead to mistakes. Adjust workflows to be more user-friendly based on error patterns. Provide interactive tutorials or simulation-based training directly within HMIs, utilizing DT visualizations. Regularly assess how new operators adapt to the system and refine features to reduce the learning curve.

- Unauthorized access to sensitive production data stored in the cloud. VPN vulnerabilities, such as default configurations or weak encryption, leading to eavesdropping or unauthorized access. Overwhelming the cloud service with traffic to disrupt operations. Attackers gain higher access levels in the cloud environment. Conduct regular vulnerability scans and penetration tests on the VPN and cloud systems.

- Intercepting data between physical and virtual digital twins. Introducing false data to the DT for incorrect task planning or decision-making. Modifying task planning or simulations in AR/VR. Monitor the consistency between physical and virtual digital twins with hash-based verification. Use real-time validation for AR/VR interactions to prevent discrepancies.

- Intercepting traffic on OPC UA or Profinet and Ethernet networks. Re-sending valid commands to disrupt synchronized operations. Encrypting MPS control data to halt operations. Deploy intrusion detection systems for LAN/WAN traffic. Conduct protocol fuzzing for OPC UA and Profinet to identify weaknesses.

- Exploiting interfaces to control MCPRS movements or manipulations. Tampering with MVSS inputs to misdirect MCPRS operations. Targeting vulnerabilities in WMR or RM software. Validate commands with digital signatures. Use redundant sensor fusion to detect anomalies in localization.

- Enforce end-to-end encryption data transmission. Implement multi-factor authentication for cloud and VPN access. Use zero-trust architecture for access control, ensuring only verified users/devices can connect. Regularly apply security patches to cloud platforms and VPN clients.

- Use encrypted data streams between physical and digital twins. Deploy blockchain for immutable record-keeping of DT transactions. Implement role-based access control for AR/VR task planning. Use AI anomaly detection to identify malicious activity in DT simulations.

- Secure RM and WMR firmware with secure boot mechanisms. Introduce runtime integrity checks for MCPRS operations. Use geofencing policies to limit MCPRS operation to specific areas.

- Develop and enforce cybersecurity policies for employees and contractors. Deploy endpoint detection and response tools across WSs and PLCs. Establish an incident response plan and perform regular cybersecurity drills.

- To ensure the implemented cybersecurity measures are effective. Conduct periodic audits and risk assessments. Use penetration testing and red teaming to simulate attacks. Track key performance indicators, such as the number of blocked intrusion attempts or time to detect/respond to threats. Regularly review and update the system against emerging threats.Bottom of Form

6. Conclusions

- The system uniquely combines a modular production line with a mobile robot capable of handling dynamic task reallocation, including transporting defective products back to the first station for reprocessing or scrapping. This improves efficiency and adaptability compared to static production lines.

- Each of the four workstations is managed by a dedicated PLC, all connected via Profibus DP to a central PLC. This hierarchical architecture ensures robust control of the MPS while supporting interoperability between multiple subsystems. Integration of LAN-Profinet, LAN-Ethernet, and WAN-Ethernet with OPC-UA connectivity allows for seamless communication between local and cloud-based systems, enabling remote control and monitoring.

- The system allows users to visualize and interact with production workflows in real-time using AR. This enhances operational insight and decision-making, offering an intuitive interface for task scheduling and error handling. Through SHPN, TPN and CPN, the system provides real-time visualization of both the MPS and MCPRS operations. This ensures precise synchronization and improved transparency. Using SHPN to integrate TPN for MPS processes and CPN for MCPRS movement is a novel approach. This enables seamless synchronization between stationary and mobile elements, improving the system’s response to changes in production demands. This hybrid modeling ensures real-time adaptability and flexibility in production line workflows, crucial for scenarios like reprocessing or scrapping defective items.

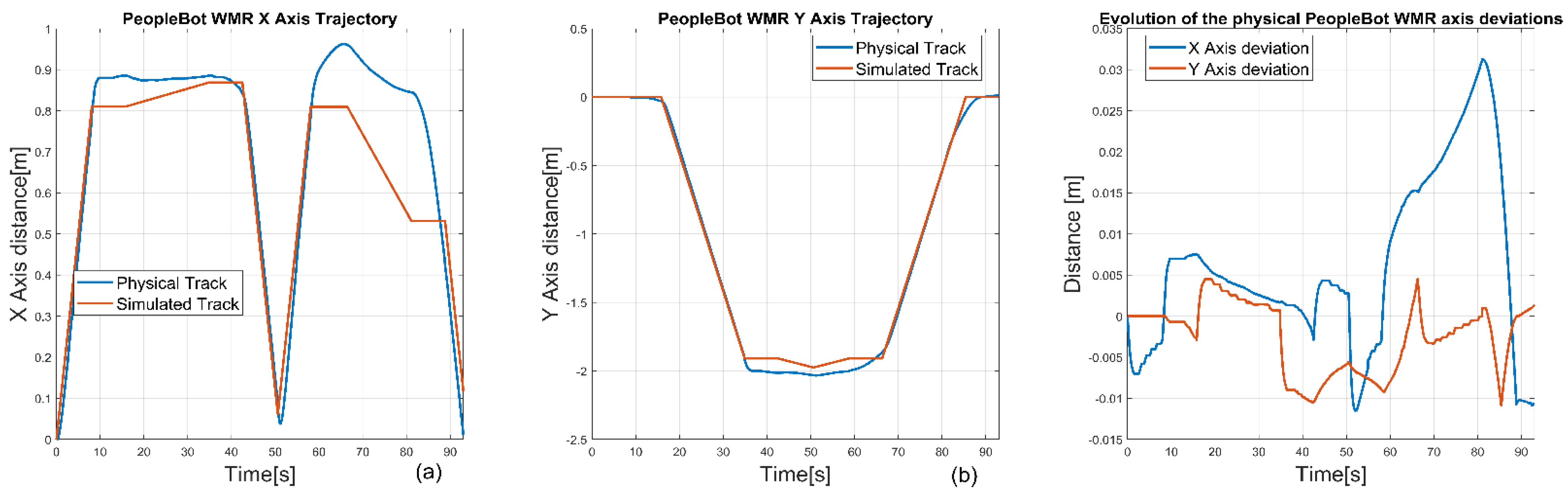

- The MCPRS includes a wheeled mobile robot (2DW/1FW) with a 7-DOF RM and an MVSS. This provides high precision in handling and transporting workpieces. Its ability to interact with the production line dynamically and respond to feedback from quality tests is a distinct innovation in Industry 4.0 applications. The MCPRS enables defective workpieces to be reintroduced into the production line or scrapped based on quality control feedback. This level of adaptability is rare in traditional production systems.

- Through WAN-Ethernet and OPC-UA, the system supports cloud-based monitoring and VPN-enabled secure remote access. This is vital for real-time diagnostics, performance monitoring, and remote control. Enables decentralized control, supporting the scalability and resilience of the production process.

- The integration of AR, VR, and DT enhances automation, operational flexibility, and predictive capabilities. The system serves as a comprehensive teaching and research platform for advanced manufacturing systems, emphasizing real-time control, DT applications, and IoT-enabled connectivity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bradley, J.M.; Atkins, E.M. Optimization and Control of Cyber-Physical Vehicle Systems. Sensors 2015, 15, 23020–23049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincă, E.; Filipescu, A.; Cernega, D.; Șolea, R.; Filipescu, A.; Ionescu, D.; Simion, G. Digital Twin for a Multifunctional Technology of Flexible Assembly on a Mechatronics Line with Integrated Robotic Systems and Mobile Visual Sensor—Challenges towards Industry 5.0. Sensors 2022, 22, 8153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, G.; Filipescu, A.; Ionescu, D.; Șolea, R.; Cernega, D.; Mincă, E.; Filipescu, A. Mobile Visual Servoing Based Control of a Complex Autonomous System Assisting a Manufacturing Technology on a Mechatronics Line. Inventions 2022, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, M.; Garcia-Alfaro, J. Design, Modeling and Implementation of Digital Twins. Sensors 2022, 22, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiceanu, G.; Paraschiv, G. Digital Twin and Smart Manufacturing in Industries: A Bibliometric Analysis with a Focus on Industry 4.0. Sensors 2022, 22, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos-Mancilla, M.A.; Luque-Vega, L.F.; Guerrero-Osuna, H.A.; Ornelas-Vargas, G.; Aguilar-Molina, Y.; González-Jiménez, L.E. Educational Mechatronics and Internet of Things: A Case Study on Dynamic Systems Using MEIoT Weather Station. Sensors 2021, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berriche, A.; Mhenni, F.; Mlika, A.; Choley, J.-Y. Towards Model Synchronization for Consistency Management of Mechatronic Systems. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian Filipescu, Eugenia Minca, Daniela Cernega, Razvan Solea, Adriana Filipescu, Simion Georgian, Dan Ionescu, Digital Twin Based a Processing Technology Assisted by a MCPRS, Ready for Industry 5.0, 97 - 3022023 27th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing, ICSTCC 2023Timisoara, 11-13 October 2023, ISSN: 2473-5698. [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, A.; Mincă, E.; Filipescu, A.; Coandă, H.-G. Manufacturing Technology on a Mechatronics Line Assisted by Autonomous Robotic Systems, Robotic Manipulators and Visual Servoing Systems. Actuators 2020, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, Adrian; Minca, E. Filipescu, Adriana Mechatronics Manufacturing Line with Integrated Autonomous Robots and Visual Servoing Systems. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, and Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics (CIS-RAM 2019), Bangkok, Thailand, 18–20 November 2019; pp. 620–625. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.M.; Ponce, P.; Macias, I.; Molina, A. Automation Pyramid as Constructor for a Complete Digital Twin, Case Study: A Didactic Manufacturing System. Sensors 2021, 21, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamunuarachchi, D.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Banerjee, A.; Jayaraman, P.P. Digital Twins Supporting Efficient Digital Industrial Transformation. Sensors 2021, 21, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachálek, J.; Šišmišová, D.; Vašek, P.; Fiťka, I.; Slovák, J.; Šimovec, M. Design and Implementation of Universal Cyber-Physical Model for Testing Logistic Control Algorithms of Production Line’s Digital Twin by Using Color Sensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallala, A.; Kumar, A.A.; Hichri, B.; Plapper, P. Digital Twin for Human–Robot Interactions by Means of Industry 4.0 Enabling Technologies. Sensors 2022, 22, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stączek, P.; Pizoń, J.; Danilczuk, W.; Gola, A. A Digital Twin Approach for the Improvement of an Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMR’s) Operating Environment—A Case Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Hadi, M.; Kraus, D.; Kajmakovic, A.; Suschnigg, J.; Guiza, O.; Gashi, M.; Sopidis, G.; Vukovic, M.; Milenkovic, K.; Haslgruebler, M.; et al. Towards Flexible and Cognitive Production—Addressing the Production Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, J.; Mourtzis, D. An Intelligent Product Service System for Adaptive Maintenance of Engineered-to-Order Manufacturing Equipment Assisted by Augmented Reality. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, A.; Dembińska, I.; Marzantowicz, Ł. Analysis of the Risk Impact of Implementing Digital Innovations for Logistics Management. Processes 2019, 7, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Lv, X.; Lin, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L. Autonomous Operation Method of Multi-DOF Robotic Arm Based on Binocular Vision. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravankar, A.; Ravankar, A.A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Peng, C.-C. Path Smoothing Techniques in Robot Navigation: State-of-the-Art, Current and Future Challenges. Sensors 2018, 18, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corke, P.I.; Spindler, F.; Chaumette, F. Combining Cartesian and polar coordinates in IBVS. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, St. Louis, MO, USA, 11 December 2009; pp. 5962–5967. [Google Scholar]

- Copot, C. Control Techniques for Visual Servoing Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Iasi, Iasi, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Petrea, G.; Filipescu, A.; Solea, R.; Filipescu, A., Jr/. Visual Servoing Systems Based Control of Complex Autonomous Systems Serving a P/RML. In Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE, International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing, (ICSTCC), Sinaia, Romania, 10–12 October 2018; pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.; Li, F.; Fu, T.; Zhao, J. A Robotic Automatic Assembly System Based on Vision. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C.-W.; Chang, C.-Y. Development of a Low Cost and Path-free Autonomous Patrol System Based on Stereo Vision System and Checking Flags. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wilson, W.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. Dynamic performance of the position-based visual servoing method in the Cartesian and image spaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–31 October 2003; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, N.; Hutchinson, S.; Corke, P. Performance tests for visual servo control systems, with application to partitioned approaches to visual servo control. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2003, 22, 955–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Node-RED web-based flow editor for remote control, Node-RED 4.0 released - News - Node-RED Forum (nodered.org), (accessed on 11October 2024).

- Sirphyco Simulateur de Réseaux de Petri, Sirphyco-Simulateur-de-Reseaux-de-Petri. Available online: https://www.toucharger.com (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- MathWorks. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Totally Integrated Automation Portal, TIA Portal V17. Available online: https://www.siemens.com/tia-portal (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- OpenCV. Available online: https://opencv.org (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Microsoft Visual Studio. Available online: https://www.visualstudio.com/vs/cplusplus (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- SCADA System SIMATIC, WinCC SIMATIC WinCC V7 / V8 - Siemens Xcelerator Global(accessed on 11 October 2024).

- VNC (Virtual Network Computing), RealVNC® Remote Access Software for Desktop and Mobile | RealVNC. Available online: https://www.realvnc.com (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Advanced Robotics Interface for Applications (ARIA). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180205212122/http://robots.mobilerobots.com/wiki/Aria (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- MobileSim, Simulator for Mobile Robots- http://robots.mobilerobots.com/MobileSim.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).